Comparative analysis of tensiomyographic and isokinetic assessments of the rectus abdominis and erector spinae in bodybuilding trainees with nonspecific low back pain

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Yumeng Li

- Subject Areas

- Rehabilitation, Sports Medicine

- Keywords

- Nonspecific low back pain, Trunk flexor, Trunk extensor, Contraction time, Maximum displacement

- Copyright

- © 2025 Kim et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits using, remixing, and building upon the work non-commercially, as long as it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2025. Comparative analysis of tensiomyographic and isokinetic assessments of the rectus abdominis and erector spinae in bodybuilding trainees with nonspecific low back pain. PeerJ 13:e20309 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.20309

Abstract

Background

Bodybuilding training places a significant load on the lumbar region, making it prone to nonspecific low back pain (NSLBP). This study aimed to examine the associations between tensiomyography (TMG) parameters—contraction time (Tc), relaxation time (Tr), delay time (Td), maximum displacement (Dm), and sustain time (Ts)—and isokinetic dynamometric measures, including peak torque (PT) and work per repetition (WR), in trunk muscles of bodybuilding trainees with NSLBP.

Methods

A total of 150 participants were allocated to a control group (n = 60) and the NSLBP group (n = 90). Pain severity from NSLBP was evaluated using the Numerical Pain Rating Scale and the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire. Daily calorie intake, assessed using an artificial intelligence (AI) camera, and physical activity levels, calculated through a standardized equation website, were averaged weekly and analyzed monthly. The muscle function of the rectus femoris and erector spinae was first assessed using TMG, followed by a 30-minute rest period before performing trunk flexion and extension tests with an isokinetic dynamometer.

Results

This study revealed that the parameters assessed using TMG and isokinetic equipment were lower or indicated greater weakness in the NSLBP group compared to the control group. Tc, Tr, and Td showed negative correlations with PT and WR, whereas Dm and Ts were positively associated. The NSLBP group demonstrated significantly longer Tc, Tr, and Td, along with lower Dm, Ts, PT, and WR values. These findings suggest that TMG variables, which assess muscle function at rest, are associated with the torque parameters measured by isokinetic dynamometry during movement. Bodybuilding trainees with a history of NSLBP exhibit impairments in both static and dynamic muscle function, indicating the need for stability-focused interventions during training.

Introduction

Nonspecific low back pain (NSLBP) is the most prevalent form of low back pain (LBP), accounting for approximately 90–95% of all cases (Howarth et al., 2024; Imamura et al., 2016; Jiang et al., 2024). Unlike specific LBP, NSLBP lacks a clear pathological cause and is often linked to risk factors such as obesity, sedentary lifestyles, repetitive trunk flexion and rotation, and improper heavy lifting (Alshehri et al., 2024). These multifactorial influences—encompassing biomechanical, psychosocial, and lifestyle-related factors—play a critical role in both the onset and the persistence of NSCLBP. Biomechanical contributors include improper posture, repetitive strain, and reduced core stability, which can increase spinal load and tissue stress. Psychosocial factors, such as stress, depression, and fear-avoidance beliefs, may exacerbate pain perception and hinder recovery. Additionally, lifestyle-related elements, including physical inactivity, obesity, and poor sleep quality, can further compromise musculoskeletal resilience and impair healing processes. The complex interplay among these factors creates a self-perpetuating cycle, making NSCLBP a challenging condition to treat and prevent (Maher, Underwood & Buchbinder, 2017; Shmagel, Foley & Ibrahim, 2016; Sidiq et al., 2024).

Bodybuilding has gained popularity across diverse age groups, driven by an emphasis on physical aesthetics (Huebner et al., 2022) and the pursuit of improved quality of life through intensive resistance training. The concept of body image–related quality of life describes the degree to which an individual’s cognitive perception of their body impacts overall life satisfaction and well-being (Tod & Edwards, 2015). In essence, bodybuilding involves stimulating the body through various weight training methods to achieve an ideal level of development, thereby promoting physical and mental self-fulfillment (Huebner et al., 2022). Despite its benefits, bodybuilding exercises are often associated with a higher risk of musculoskeletal injuries—including muscle strains, tendinitis, and NSLBP—due to the combination of high training loads, repetitive movements, and sometimes inadequate technique. Most bodybuilding routines emphasize progressive overload and maximal resistance training (Chaput et al., 2011), which, while effective for muscle hypertrophy, can place substantial mechanical stress on muscles, tendons, ligaments, and joints. Repetitive, high intensity loading without adequate rest periods may also lead to microtrauma accumulation, increasing the risk of overuse injuries such as tendinitis. Furthermore, improper lifting technique, insufficient core stabilization, and muscular imbalances between agonist and antagonist muscle groups can compromise spinal alignment and load distribution, contributing to the onset or exacerbation of NSLBP. Finally, bodybuilding culture may sometimes encourage training through discomfort or fatigue, which can impair neuromuscular control and further elevate injury risk (Bonilla et al., 2022; Jiang et al., 2024). The hypertrophic effects of resistance training are primarily attributed to the enlargement of fast-twitch muscle fibers (Huebner et al., 2022; Gehrig et al., 2010). While initial studies employed invasive muscle biopsies (Loell et al., 2011), recent advancements favor non-invasive assessment techniques (Kandwal et al., 2024). Among these, tensiomyography (TMG) and isokinetic dynamometry are widely recognized for their reliability in evaluating muscle function. Unlike magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and surface electromyography (EMG), which are costly or susceptible to noise (Campanini et al., 2020), TMG and isokinetic tests offer selective, non-invasive, and repeatable measures of muscle contractility (Toskić et al., 2019). These methods offer the advantage of selectively evaluating specific muscles, high versatility, and the capability for continuous measurements. Furthermore, the scientific assessment of variables derived from these tools has facilitated their widespread application in various practical settings (Tous-Fajardo et al., 2010).

TMG assesses muscle contractile properties via external stimulation without requiring voluntary contraction, enabling the analysis of muscle hypertrophy and atrophy through five key parameters, offering a thorough assessment of static muscle function (Lohr et al., 2018). Its reliability and precision have made it widely utilized in both research and clinical practice (Martín-Rodríguez et al., 2017; Tous-Fajardo et al., 2010). Conversely, isokinetic dynamometry evaluates muscle strength across controlled velocities and contraction modes, allowing the analysis of torque and power output. By measuring the muscle moments’ ratio, it is possible to identify potential issues within the targeted muscle groups (Yahia et al., 2011). Isokinetic measurements are well-regarded for their reliability and precision (Mueller et al., 2011; Paul & Nassis, 2015) and are frequently utilized for assessing dynamic strength to understand the mechanical profiles of skeletal muscles, including those of the trunk regions (Van Damme et al., 2013). While both TMG and isokinetic dynamometry have proven individually valuable, the relationship between their respective measures remains underexplored. Moreover, few studies have investigated trunk muscle characteristics, particularly in relation to NSLBP, within bodybuilding populations—despite the increasing popularity of body building across age groups. Prior research has primarily focused on clinical or athletic populations without addressing the unique muscular adaptations and potential injury risks associated with resistance training. Should the results of this study contradict our hypotheses, it would suggest that the relationship between muscle contractile properties and NSLBP in bodybuilders may be more complex than previously understood, warranting further investigation into alternative mechanisms or contributing factors. Therefore, this study aimed to fill these gaps by examining the prevalence of NSLBP in individuals engaged in regular bodybuilding and comparing TMG and isokinetic muscle contractile properties between those with and without NSLBP. By integrating these assessment modalities, our research tried to seek to provide novel insights into the neuromuscular factors associated with NSLBP in a bodybuilding cohort, thereby advancing understanding beyond existing literature.

Materials & Methods

Participants

To identify cases of NSLBP, a standardized clinical assessment protocol was implemented. This process included a structured interview, physical examination, and red flag screening, based on established guidelines for diagnosing NSLBP (Delitto et al., 2012; Maher, Underwood & Buchbinder, 2017). All 150 participants were young adults (aged 19–25 years) who had engaged in bodybuilding training for at least one year, with a minimum training frequency of four sessions per week. Each participant underwent an individual assessment conducted by a licensed physical therapist specializing in musculoskeletal disorders. The clinical interview collected information on the presence, onset, duration, and characteristics of LBP. Participants were specifically asked about pain location, intensity, aggravating and relieving factors, and possible training-related causes. Any reports of radiating pain, numbness, tingling, or muscle weakness in the lower extremities were documented for differential diagnosis. A standardized physical examination assessed lumbar range of motion, local tenderness, and pain provocation during movement. Neurological screening included muscle strength, sensory function, and deep tendon reflexes. Special tests such as the straight leg raise and Slump test were performed to evaluate possible neural involvement. Participants were also screened for red flag symptoms indicative of serious pathology, including a history of malignancy, unexplained weight loss, prolonged corticosteroid use, recent trauma, persistent night pain, or fever. Individuals presenting with any red flag indicators were excluded from the NSLBP group and referred for further medical evaluation such as herniated disc, spondylolysis, spondylolisthesis, spinal stenosis, or facet joint syndrome. Additionally, exclusion criteria included smoking, alcohol consumption, current pharmacological or physical therapy treatment, or any surgical procedures within one year before enrollment.

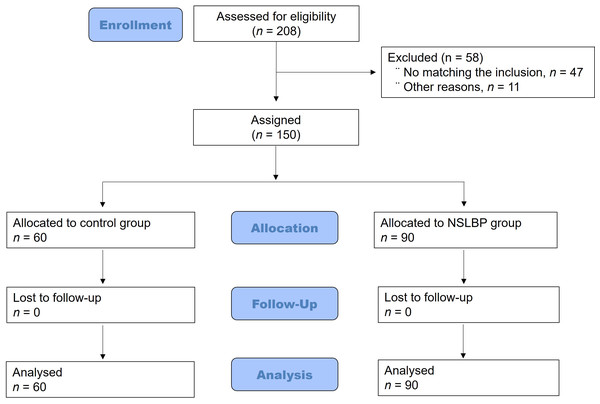

Sample size estimation was performed using G*Power software (version 3.1.9.7, Heinrich-Heine-University Software, Germany with the following parameters: effect size = 0.5, α = 0.05, power = 0.95, and allocation ratio = 1 (Kang, 2021). A minimum of 174 participants was determined to be necessary; 208 were recruited to accommodate a 20% attrition rate (Sedgwick, 2013). Of the 208 participants initially recruited for the study, 58 were excluded due to not meeting the inclusion criteria or for personal reasons. After applying exclusion criteria, 150 participants were enrolled and assigned to either the control (n = 60) or NSLBP (n = 90) group. Throughout the one-month experiment, there were no dropouts from either the CON group or the NSLBP group, leading to the final analysis based on data from 60 participants in the CON group and 90 in the NSLBP group as shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Flowchart for classifying research subjects.

Out of 208 participants initially screened, 58 were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria. The remaining 150 were enrolled and allocated to either the control group (n = 60) or the NSLBP group (n = 90), forming the cohort for the final analysis.Experimental design

This case-control study was conducted from March to December 2024. The study followed the Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Nonrandomized Designs statement (Des Jarlais et al., 2004) and complied with the Sex and Gender Equity in Research guidelines (Heidari et al., 2016). The investigation adhered to the ethical standards outlined in the declaration of Helsinki (Williams, 2008). Ethical approval was granted by the Institutional Review Board of Hanseo University (HS22-05-03). Prior to participation, all subjects received detailed explanations of the study’s purpose and procedures and provided written informed consent. Double blinding was maintained throughout data collection. Daily logs were used to monitor dietary intake and physical activity to control for external variables.

Measurement methods

Body composition and demographics

Age and sex were self-reported. Height was measured using a digital stadiometer (BMS 330; BioSpace, Seoul, Korea), and body composition was assessed using Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DEXA), whole-body scan (TSX-303A, Toshiba Medical Systems Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) with participants in a supine position after a 10-hour fasting period. The DEXA scan was performed quickly to minimize radiation exposure (Jee, 2019; Smith-Bindman, 2010). Body mass index was also calculated using the weight-to-height ratio formula. Waist and hip circumferences were measured using standardized protocols to calculate the waist-to-hip ratio (Park, Kim & Jee, 2024).

Pain intensity related to NSLBP

NSLBP was operationally defined as non-specific, localized low back pain in the absence of neurological deficits, serious structural pathology, or red flag symptoms. The participants’ pain intensity levels were evaluated using the Numerical Pain Rating Scale (NPRS; 0–10 cm). On this scale, 0 indicates “no pain,” while 10 represents “the worst imaginable pain.” Participants were instructed to select the number that best described their current pain. The NPRS has been demonstrated to be a reliable, valid, and responsive tool for measuring pain intensity in individuals with chronic LBP (Ibrahim et al., 2020; Sarafadeen, Ganiyu & Ibrahim, 2020). In this study, the level of pain-related disability associated with NSLBP was also evaluated using the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ), a self-reported assessment tool (Roland & Morris, 1983). The RMDQ is concise and easy for patients to complete, demonstrating strong validity, internal consistency, and responsiveness (Roland & Fairbank, 2000; Stratford et al., 1996). The RMDQ consists of 24 items, each qualified with the phrase “because of my back pain,” specifically attributing the disability to back pain experienced in the past 24 h (Ren & Kazis, 1998). Scores are calculated by summing up the number of items checked. The total score ranges from 0 (no disability) to 24 (maximum disability) (Roland & Fairbank, 2000). In this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficient between the duration of NSLBP and the NPRS was found to be 0.866, while the coefficient between the duration of NSLBP and the RMDQ was analyzed as 0.703.

Measurement for calorie input and output

All participants were instructed on how to use a dietary camera AI system (DoingLab Inc., Seoul, Korea) to photograph the meals they prepared for consumption each day (Park, Kim & Jee, 2024). The system automatically calculated the calorie intake from the images, and these data were transmitted daily to a designated researcher for evaluation. The data were then analyzed weekly, with the average of the data from the final 4 weeks used for analysis. Additionally, participants’ daily physical activity levels were recorded and quantified using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire—Short Form (Chun, 2012). Participants completed the questionnaire each week during the experimental period, based on their physical activity records. Daily calorie expenditure was calculated using metabolic equivalent-minutes, and the data were used to compute the average weekly physical activity levels, which were subsequently analyzed based on the accumulated data.

Tensiomyographic trunk muscle tone measures

A digital TMG displacement sensor (TMG-BMC Ltd., Ljubljana, Slovenia), featuring a spring constant of 0.17 N/mm, was used as one of the static muscle function measurement devices. It was positioned perpendicular to the rectus abdominis (RA) muscle belly at approximately five cm intervals on both the left and right sides of the navel, as illustrated in Fig. 2A (Park, Kim & Jee, 2024). Additionally, it was placed on the lumbar erector spinae (ES) at the interspace between the L3 and L4 vertebrae (Lohr & Medina-Porqueres, 2021) as shown in Fig. 2B. The inter-electrode distance in TMG was set to three cm in accordance with standard methodological recommendations to ensure reliable and reproducible measurements (Lohr & Medina-Porqueres, 2021). Previous validation studies have demonstrated that a three cm separation between the stimulating electrodes provides an optimal balance between effective muscle fiber recruitment and minimization of current spread to adjacent muscles, thereby reducing cross-talk artifacts. This distance also helps maintain a consistent stimulation field, which is critical for accurately assessing contractile properties such as contraction time and maximal displacement. Moreover, adopting a standardized electrode spacing facilitates comparability of results across studies and aligns with established TMG protocols in the literature (De Paula Simola et al., 2015).

Figure 2: Tensiomyographic rectus abdominis and erector spinae measurement scene.

A digital TMG device was placed perpendicular to the rectus abdominis muscle belly at ∼5 cm intervals on both the left and right sides of the navel (A) and on the lumbar erector spinae at the intervertebral space between L3 and L4 (B).The optimal measurement point, located at the thickest part of the muscle bulk approximately two cm lateral to the dorsal midline, was identified through visual orientation and palpation during both voluntary and elicited contractions (Lohr et al., 2020). Once the optimal measurement point was located, the sensor and electrode positions were marked with a dermatological pen to ensure precise relocation (Lohr & Medina-Porqueres, 2021). A single square-wave monophasic 1 ms stimulation pulse was delivered using an electrical stimulator (TMG–S1, TMG-BMC Ltd., Ljubljana, Slovenia) with an initial stimulation current of 30 mA. To determine the individual maximal twitch response amplitude, the stimulation current was progressively increased by 10 mA increments (Piqueras-Sanchiz et al., 2020). Inter-stimulus interval of ≥10 s was maintained between successive measurements to prevent fatigue and potentiation. The two highest twitch responses observed on the displacement graph for each participant were recorded and averaged for subsequent analysis (Tous-Fajardo et al., 2010). The primary variables under consideration are the maximum displacement (Dm), which measures the maximum distance (in mm) the muscle moves during contraction, and the contraction time (Tc), which represents the time (ms) it takes for the muscle to contract from 10% to 90% of Dm. Stimulation commenced at an initial intensity of 20 mA and was incrementally raised by 10 mA steps until the maximum Dm value was achieved as shown in Fig. 2C. Before conducting the measurements, participants were instructed to rest in bed for 5 min to ensure muscle relaxation. Subsequently, the recorded values were documented and subjected to analysis. In addition, this study examined sustain time (Ts), relaxation time (Tr), and delay time (Td). Td refers to the time taken to reach 10% of the maximum Dm. Ts represents the duration the muscle stays in the contraction phase at 50% of Dm before entering the relaxation phase. Tr indicates the time it takes for the muscle to transition from 90% of Dm to 50% during relaxation (Dahmane et al., 2001). Lastly, Vc, the contraction velocity for the muscle, was calculated as Dm/(Tc + Td). The right and left values of all variables were presented, and then all were averaged and analyzed.

Isokinetic trunk muscle concentric contraction measures

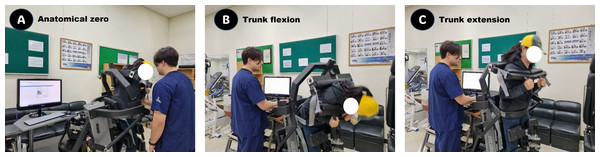

Isokinetic trunk extension and flexion (TEF) tests were utilized to evaluate the moments of the trunk muscles, as outlined by García-Vaquero and colleague (2020). The test using the isokinetic dynamometer (Fig. 3A) is a representative method for assessing dynamic muscle function. This dynamometer maintains a constant speed throughout muscle contraction, allowing for accurate and reliable measurement of force and performance. From a practical perspective, isokinetic dynamometer-based muscle assessment methods are considered valid and highly reliable (Warneke et al., 2025), with correlation coefficients of 0.93–0.99 for peak force values and 0.91–0.96 for total workload values (BenMoussa Zouita et al., 2018; Guilhem et al., 2014). Trunk flexion typically exhibits a range of motion between 40° and 60° (Fig. 3B), with an average of 45°, whereas trunk extension generally ranges from 20° to 35° (Fig. 3C), with an average of around 25° (Morini et al., 2008).

Figure 3: Isokinetic trunk flexor/extensor measurement scene.

During the isokinetic dynamometer test, after setting the anatomical zero (A), muscle contractions were performed at a constant velocity, with trunk flexion averaging 45° (B) and trunk extension approximately 25° (C).In this study, participants completed a comprehensive stretching and warm-up routine prior to testing. The TEF assessments were conducted using the HUMAC®/NORM™ Testing and Rehabilitation System (CSMi, Stoughton, MA, USA). During the isokinetic TEF concentric contraction tests, participants stood with their iliac crests aligned to the dynamometer axis and stabilized using knee, lumbar, and chest pads to ensure proper alignment and minimize extraneous movements. The testing protocol began with an isokinetic resistance set at 90°/sec, during which participants performed four practice repetitions followed by eight test repetitions. After a 1-min rest interval, the resistance was adjusted to 30°/sec, and participants performed an additional 4 practice repetitions followed by four test repetitions. For analysis, the study focused on key metrics, including peak torque (PT) and peak torque normalized to body weight (PTBW), as well as work per repetition (WR) and work per repetition normalized to body weight (WRBW).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism 10.4.2 software (GraphPad Software, Boston, MA, USA). Descriptive statistics, including the mean and standard deviation, were used to summarize the data. The normality of variable distribution was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test before analysis. For variables that did not meet normality assumptions, homogeneity was evaluated using the Mann–Whitney U test. The analysis was carried out in three key steps. First, Cronbach’s α was calculated to assess the internal validity of the questionnaire used in this study. Second, Pearson correlation analysis was performed to examine the relationship between TMG and isokinetic muscle function, with a correlation matrix created for clarity. Correlation coefficients were classified as excellent (≥0.90), good (0.75–0.90), average (0.50–0.75), or poor (<0.50) (Koo & Li, 2016). Third, to compare TMG and isokinetic muscle function between CON and NSLBP groups, an independent t-test was used for normally distributed data, while the Mann–Whitney U test was applied to non-normally distributed data. Effect sizes for parametric measures were categorized as small (0.2), moderate (0.5), or large (0.8), while for non-parametric measures, thresholds of 0.1, 0.3, and 0.5 were used, following Fritz, Morris & Richler (2012). Statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

Results

Demographic and physical characteristics

As shown in Table 1, there was no statistically significant difference in age between the CON and NSLBP groups.

| Groups | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Items | CON (n= 60) | NSLBP (n= 90) | Z | p | η2 |

| Age (years) | 21.9 ± 1.0 | 22.0 ± 1.6 | −0.476 | 0.634 | 0.003 |

| Sex† | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 1.3 ± 0.4 | −1.117 | 0.264 | 0.008 |

| Stature (cm) | 170.8 ± 8.6 | 172.1 ± 8.5 | −0.722 | 0.470 | 0.006 |

| Weight (kg) | 68.7 ± 12.1 | 70.9 ± 12.8 | −1.040 | 0.298 | 0.008 |

| Muscle mass (kg) | 29.9 ± 6.9 | 31.0 ± 6.6 | −0.946 | 0.344 | 0.007 |

| Fat mass (kg) | 15.7 ± 3.5 | 15.1 ± 5.1 | −1.249 | 0.212 | 0.004 |

| Percent fat (%) | 23.4 ± 6.4 | 21.9 ± 7.5 | −1.638 | 0.101 | 0.010 |

| Lean mass (kg) | 52.2 ± 10.7 | 51.7 ± 8.6 | −0.146 | 0.884 | 0.001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.6 ± 2.6 | 23.9 ± 2.7 | −0.616 | 0.538 | 0.002 |

| Waist-to-hip ratio | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | −0.649 | 0.516 | 0.002 |

| Basal metabolic rate (kcal) | 1,544.3 ± 244.6 | 1,586.7 ± 243.8 | −1.109 | 0.267 | 0.007 |

| Diet level (kcal) | 2,390.7 ± 311.0 | 2,440.1 ± 266.5 | −0.794 | 0.427 | 0.007 |

| PA level (MET min/week) | 2,110.1 ± 742.0 | 2,201.5 ± 726.4 | −0.599 | 0.549 | 0.004 |

| Training duration (years) | 3.1 ± 0.7 | 2.9 ± 1.1 | −1.649 | 0.099 | 0.011 |

| LBP duration (month) | 0.1 ± 0.2 | 4.8 ± 2.2 | −10.542 | 0.001 | 0.624 |

| NPRS (scores) | 0.6 ± 0.3 | 4.7 ± 1.0 | −10.447 | 0.001 | 0.843 |

| RMDQ (scores) | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 7.7 ± 3.2 | −10.372 | 0.001 | 0.648 |

Notes:

- CON

-

control group

- NSLBP

-

nonspecific low back pain group

- PA

-

physical activity

- LBP

-

low back pain

- NPRS

-

Numerical pain rating scale

- RMDQ

-

Roland-Morris disability questionnaire

Regarding sex distribution, the CON group consisted of 36 males and 24 females, while the NSLBP group included 62 males and 28 females. When sex was quantified (male = 1, female = 2) for statistical comparison, no significant difference was observed between the groups. None of the participants reported smoking or alcohol consumption. In addition, there was no significant difference in training duration between the groups. As also shown in Table 1, the basal metabolic rate, daily dietary intake, and physical activity level were not significantly different between the two groups. The groups were classified based on the presence or absence of NSLBP, and a quantitative analysis of its duration including NPRS and RMDQ scores revealed a significant difference between the groups.

Relationships between TMG and isokinetic TEF measures

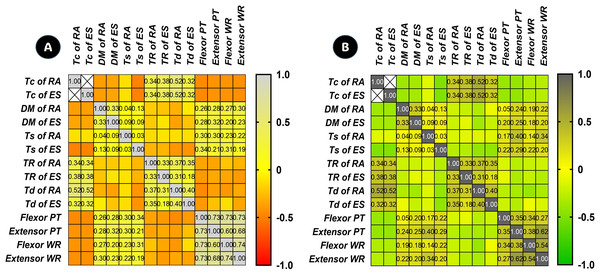

As illustrated in Fig. 4A, the Tc of the RA exhibited significant negative correlations with flexor PT (r = −0.459), extensor PT (r = −0.425), flexor WR (r = −0.420), and extensor WR (r = −0.438). Similarly, the Tc of the ES showed significant negative correlations with flexor PT (r = −0.421), extensor PT (r = −0.331), flexor WR (r = −0.259), and extensor WR (r = −0.340) at 90°/sec. The Tr of the RA displayed significant negative correlations with flexor PT (r = −0.361), extensor PT (r = −0.356), flexor WR (r = −0.225), and extensor WR (r = −0.293), while the Tr of the ES showed significant negative correlations with flexor PT (r = −0.401), extensor PT (r = −0.339), flexor WR (r = −0.349), and extensor WR (r = −0.394). The Td of the RA was significantly negatively correlated with flexor PT (r = −0.461), extensor PT (r = −0.380), flexor WR (r = −0.408), and extensor WR (r = −0.342). In addition, the Td of the ES exhibited significant negative correlations with flexor PT (r = −0.397), extensor PT (r = −0.248), and extensor WR (r = −0.353), except for flexor WR (r = −0.126, p = 0.124). In contrast, the Dm of the RA demonstrated significant positive correlations with flexor PT (r = 0.256), extensor PT (r = 0.277), flexor WR (r = 0.266), and extensor WR (r = 0.305). Likewise, the Dm of the ES showed significant positive correlations with flexor PT (r = 0.281), extensor PT (r = 0.316), flexor WR (r = 0.200), and extensor WR (r = 0.228). Additionally, the Ts of the RA exhibited significant positive correlations with flexor PT (r = 0.296), extensor PT (r = 0.301), flexor WR (r = 0.232), and extensor WR (r = 0.223), like the Dm. The Ts of the ES exhibited significant positive correlations with flexor PT (r = 0.336), extensor PT (r = 0.209), flexor WR (r = 0.308), and extensor WR (r = 0.195). Examining the characteristics among these variables, it was observed that the PT and WR of the TEF muscles at 90°/sec were higher when the Tc, Tr, and Td were shorter or lower, whereas they were lower when Tc, Tr, and Td of the RA and ES were longer or higher. Meanwhile, the PT and WR of the TEF muscles were lower when the Dm and Ts of the RA and ES were lower, but higher when Dm and Ts were higher.

Figure 4: Correlation matrix of multiple variables across each row and column between TMG and isokinetic measures.

In (A), a deeper shade of grey indicates a higher positive correlation (+1), while a shift towards red hues suggests a negative correlation (−1) between TMG and isokinetic factors at 90°/sec. In (B), a deeper shade of grey signifies a higher positive correlation (+1), whereas a shift towards green hues indicates a negative correlation (−1) between TMG and isokinetic measures at 30° /sec. Tc, contraction time; Dm, maximum displacement; Ts, sustain time; Tr, relaxation time; Td, delay time; RA, rectus abdominis; ES, erector spinae; PT, peak torque; PTBW, peak torque % body weight; WR, work per repetition; WRBW, work per repetition % body weight.As shown in Fig. 4B, the Tc of the RA exhibited significant negative correlations with flexor PT (r = −0.403), extensor PT (r = −0.414), flexor WR (r = −0.315), and extensor WR (r = −0.287). The Tc of the ES showed significant negative correlations with flexor PT (r = −0.170), extensor PT (r = −0.326), flexor WR (r = −0.269), and extensor WR (r = −0.348) at 30°/sec. The Tr of the RA displayed significant negative correlations with extensor PT (r = −0.281), flexor WR (r = −0.220), and extensor WR (r = −0.195), except for flexor PT (r = −0.154, p = 0.060). The Tr of the ES showed significant negative correlations with extensor PT (r = −0.323), flexor WR (r = −0.235), and extensor WR (r = −0.294), except for flexor PT (r = −0.096, p = 0.244). The Td of the RA exhibited significant negative correlations with flexor PT (r = −0.271), extensor PT (r = −0.341), flexor WR (r = −0.401), and extensor WR (r = −0.332). In contrast, the Td of the ES showed significant negative correlations with flexor PT (r = −0.204) and extensor PT (r = −0.293), except for flexor WR (r = −0.155, p = 0.058) and extensor WR (r = −0.064, p = 0.437). Meanwhile, The Dm of the RA demonstrated significant positive correlations with extensor PT (r = 0.277), flexor WR (r = 0.266), and extensor WR (r = 0.305), except for flexor PT (r = 0.045, p = 0.582). The Dm of the ES also showed significant positive correlations with flexor PT (r = 0.204), extensor PT (r = 0.254), flexor WR (r = 0.177), and extensor WR (r = 0.202) at 30°/sec. The Ts of the RA was significantly positively correlated with flexor PT (r = 0.167), extensor PT (r = 0.402), and extensor WR (r = 0.341), except for flexor WR (r = 0.144, p = 0.078). The Ts of the ES exhibited significant positive correlations with flexor PT (r = 0.222), extensor PT (r = 0.288), flexor WR (r = 0.220), and extensor WR (r = 0.198). Analyzing the relationships among these variables, it was observed that the PT and WR of the TEF muscles at 30°/sec were higher when the Tc, Tr, and Td of the RA and ES were shorter or lower, whereas they were lower when Tc, Tr, and Td were longer or higher. Conversely, the PT and WR of the TEF muscles were lower when the Dm and Ts were lower but higher when Dm and Ts were higher. The validity of these findings was further confirmed through a correlation matrix, examining multiple variables across each row and column between TMG measures and isokinetic measures at 90°/sec and at 30°/sec.

Differences of TMG values

As depicted in Table 2, the Tc of the RA was greater on both the left and right sides in the NSLBP group than in the CON group, with a comparable pattern observed in the mean Tc. The Tc of the ES was higher on both sides in the NSLBP group compared to the CON group, exhibiting a similar trend in the mean Tc. The Dm of the RA was lower on both sides in the NSLBP group compared to the CON group, with a similar pattern observed in the mean Dm. The Dm of the ES was lower on both sides in the NSLBP group than in the CON group, showing a comparable trend in the mean Dm. The Ts of the RA was significantly lower on both sides in the NSLBP group compared to the CON group, with a similar pattern observed in the mean Ts. The Ts of the ES was also significantly lower on both sides in the NSLBP group than in the CON group, exhibiting a comparable trend in the mean Ts.

| Groups | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Items | CON (n= 60) | NSLBP (n= 90) | Z | p | η2 |

| Tc at left rectus abdominis | 20.8 ± 7.9 | 30.3 ± 10.3 | −5.247 | 0.001 | 0.196 |

| Tc at right rectus abdominis | 20.4 ± 8.1 | 29.8 ± 11.1 | −5.141 | 0.001 | 0.175 |

| mean Tc of rectus abdominis | 20.6 ± 7.7 | 30.0 ± 10.4 | −5.308 | 0.001 | 0.194 |

| Tc at left erector spinae | 21.2 ± 8.3 | 27.1 ± 7.0 | −4.426 | 0.001 | 0.132 |

| Tc at right erector spinae | 20.9 ± 7.3 | 27.0 ± 8.3 | −4.239 | 0.001 | 0.124 |

| mean Tc of erector spinae | 21.0 ± 7.1 | 27.1 ± 6.9 | −4.685 | 0.001 | 0.154 |

| Dm at left rectus abdominis | 4.3 ± 1.7 | 3.2 ± 1.3 | −3.699 | 0.001 | 0.112 |

| Dm at right rectus abdominis | 4.1 ± 1.8 | 3.1 ± 1.4 | −3.022 | 0.003 | 0.081 |

| mean Dm of rectus abdominis | 4.2 ± 1.7 | 3.2 ± 1.3 | −3.458 | 0.001 | 0.098 |

| Dm at left erector spinae | 5.8 ± 3.1 | 4.0 ± 1.9 | −2.945 | 0.003 | 0.117 |

| Dm at right erector spinae | 5.9 ± 3.1 | 3.9 ± 1.9 | −3.693 | 0.001 | 0.134 |

| mean Dm of erector spinae | 5.8 ± 3.1 | 3.9 ± 1.8 | −3.395 | 0.001 | 0.128 |

| Ts at left rectus abdominis | 106.6 ± 28.1 | 88.9 ± 22.2 | −3.729 | 0.001 | 0.111 |

| Ts at right rectus abdominis | 107.1 ± 34.2 | 89.7 ± 25.6 | −3.046 | 0.002 | 0.079 |

| mean Ts of rectus abdominis | 106.9 ± 27.8 | 89.3 ± 21.1 | −3.342 | 0.001 | 0.115 |

| Ts at left erector spinae | 103.5 ± 17.0 | 94.6 ± 22.9 | −3.131 | 0.002 | 0.042 |

| Ts at right erector spinae | 104.3 ± 17.3 | 95.1 ± 29.5 | −2.369 | 0.018 | 0.031 |

| mean Ts of erector spinae | 103.9 ± 16.5 | 94.9 ± 23.0 | −3.054 | 0.002 | 0.044 |

| Tr at left rectus abdominis | 88.6 ± 17.9 | 106.2 ± 22.3 | −5.147 | 0.001 | 0.149 |

| Tr at right rectus abdominis | 88.2 ± 17.2 | 105.6 ± 20.6 | −5.381 | 0.001 | 0.166 |

| mean Tr of rectus abdominis | 88.4 ± 17.1 | 105.9 ± 21.1 | −5.335 | 0.001 | 0.162 |

| Tr at left erector spinae | 102.5 ± 17.6 | 110.8 ± 13.6 | −3.354 | 0.001 | 0.066 |

| Tr at right erector spinae | 100.3 ± 27.4 | 108.6 ± 17.4 | −2.482 | 0.013 | 0.034 |

| mean Tr of erector spinae | 101.4 ± 18.1 | 109.7 ± 12.8 | −3.158 | 0.002 | 0.068 |

| Td at left rectus abdominis | 7.7 ± 3.3 | 9.5 ± 2.8 | −3.378 | 0.001 | 0.080 |

| Td at right rectus abdominis | 7.7 ± 3.1 | 9.3 ± 2.5 | −3.115 | 0.002 | 0.067 |

| mean Td of rectus abdominis | 7.7 ± 3.0 | 9.4 ± 2.5 | −3.666 | 0.001 | 0.083 |

| Td at left erector spinae | 7.3 ± 3.1 | 9.5 ± 3.4 | −4.301 | 0.001 | 0.104 |

| Td at right erector spinae | 7.1 ± 3.6 | 9.6 ± 4.1 | −3.514 | 0.001 | 0.083 |

| mean Td of erector spinae | 7.2 ± 3.2 | 9.6 ± 3.5 | −4.063 | 0.001 | 0.104 |

| Vc of rectus abdominis | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | −5.212 | 0.001 | 0.158 |

| Vc of erector spinae | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | −4.630 | 0.001 | 0.165 |

Notes:

All values represent mean ± standard deviation.

- CON

-

control group

- NSLBP

-

nonspecific low back pain group

- Tc

-

contraction time

- Dm

-

maximum displacement

- Ts

-

sustain time

- Tr

-

relaxation time

- Td

-

delay time

- Vc

-

contraction velocity

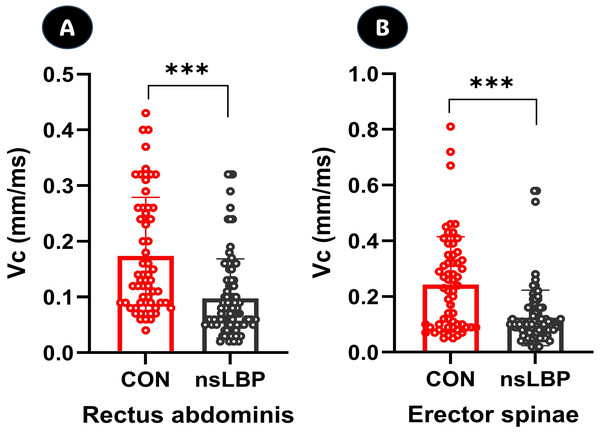

The Tr and Td of the RA were significantly higher on both sides in the NSLBP group compared to the CON group, with a similar pattern observed in the mean Tr and Td. The Tr and Td of the ES were also significantly higher on both sides in the NSLBP group than in the CON group, exhibiting a comparable trend in the mean Tr and Td. However, these differences were associated with a small effect size (≤0.1). Meanwhile, as shown in Fig. 5A, the Vc of the RA was significantly lower in the NSLBP group compared to the CON group. Similarly, the Vc of the ES was also significantly lower in the NSLBP group than in the CON group (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5: Differences of Vc (contraction velocity) in rectus abdominis and erector spinae factors.

CON, control group; NSLBP, nonspecific low back pain; ***, p < 0.001 between groups.Differences of isokinetic TEF torques

As demonstrated in Table 3, the PT of the trunk flexor measured at 90°/sec was lower in the NSLBP group compared to the CON group, with a similar pattern observed in PTBW. Likewise, the PT of the trunk extensor was significantly lower in the NSLBP group than in the CON group, showing a comparable trend in the PTBW. Meanwhile, the WR and WRBW of the trunk flexor were lower in the NSLBP group compared to the CON group, but the differences were not statistically significant. In contrast, the WR and WRBW of the trunk extensor were significantly lower in the NSLBP group than in the CON group.

| Groups | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Items | CON (n= 60) | NSLBP (n= 90) | Z | p | η2 |

| Values at 90°/sec (Nm) | |||||

| Flexor PT | 216.5 ± 83.5 | 182.7 ± 51.5 | −2.406 | 0.016 | 0.060 |

| Flexor PTBW | 319.7 ± 118.2 | 271.9 ± 99.8 | −2.858 | 0.004 | 0.046 |

| Extensor PT | 224.5 ± 65.5 | 159.8 ± 48.0 | −6.399 | 0.001 | 0.248 |

| Extensor PTBW | 332.1 ± 94.6 | 247.1 ± 82.4 | −5.772 | 0.001 | 0.187 |

| Flexor WR | 190.8 ± 83.0 | 179.6 ± 57.8 | −0.098 | 0.922 | 0.006 |

| Flexor WRBW | 278.8 ± 110.4 | 259.1 ± 91.4 | −0.568 | 0.570 | 0.009 |

| Extensor WR | 199.9 ± 98.0 | 162.8 ± 59.8 | −2.129 | 0.033 | 0.053 |

| Extensor WRBW | 290.3 ± 130.7 | 232.9 ± 86.6 | −2.826 | 0.005 | 0.066 |

| Values at 30°/sec (Nm) | |||||

| Flexor PT | 190.5 ± 39.1 | 177.6 ± 53.3 | −1.470 | 0.141 | 0.017 |

| Flexor PTBW | 281.3 ± 55.4 | 252.1 ± 66.7 | −2.561 | 0.010 | 0.050 |

| Extensor PT | 195.3 ± 58.3 | 140.9 ± 35.3 | −6.177 | 0.001 | 0.254 |

| Extensor PTBW | 287.4 ± 79.7 | 203.5 ± 56.7 | −6.302 | 0.001 | 0.277 |

| Flexor WR | 183.0 ± 62.2 | 169.0 ± 48.6 | −0.923 | 0.356 | 0.016 |

| Flexor WRBW | 268.7 ± 80.0 | 244.9 ± 77.6 | −1.682 | 0.092 | 0.022 |

| Extensor WR | 191.0 ± 91.0 | 144.6 ± 28.0 | −2.509 | 0.012 | 0.122 |

| Extensor WRBW | 278.7 ± 119.5 | 210.0 ± 53.5 | −3.419 | 0.001 | 0.134 |

Notes:

All values represent mean ± standard deviation.

- CON

-

control group

- NSLBP

-

nonspecific low back pain group

- PT

-

peak torque

- PTBW

-

peak torque % body weight

- WR

-

work per repetition

- WRBW

-

work per repetition % body weight

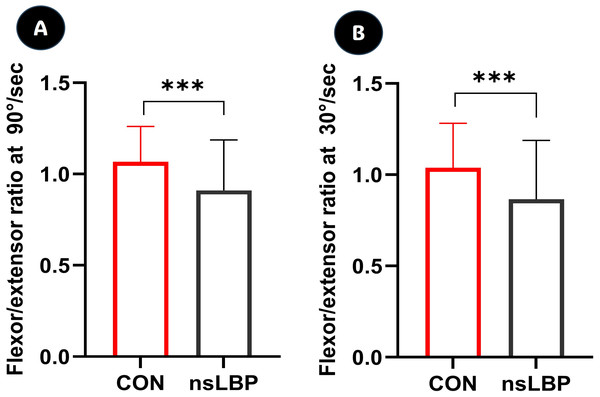

As shown in Fig. 6A, the ratio of the PT of the trunk extensor to that of the trunk flexor was significantly lower in the NSLBP group compared to the CON group, indicating that the trunk extensor in the NSLBP group exhibited lower moments during force production. At 30°/sec, the PT and PTBW of the trunk flexor, as shown in Table 3, were lower in the NSLBP group compared to the CON group. However, a statistically significant difference was observed only in PTBW. In contrast, both the PT and PTBW of the trunk extensor were significantly lower in the NSLBP group than in the CON group. Similarly, the WR and WRBW of the trunk flexor were lower in the NSLBP group than in the CON group, though the difference was not statistically significant. However, the WR and WRBW of the trunk extensor were significantly lower in the NSLBP group. Additionally, as illustrated in Fig. 6B, the ratio of PT of the trunk extensor to that of the trunk flexor was significantly lower in the NSLBP group, indicating reduced trunk extensor moment in this group compared to the CON group.

Figure 6: Differences of trunk extensor/flexor peak torques’ ratio at isokinetic 90°/sec and 30°/sec.

CON, control group; NSLBP, nonspecific low back pain; ***, p < 0.001 between groups.Discussion

Relationships between TMG factors and isokinetic TEF measures

The primary aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between TMG and isokinetic measures in the trunk muscles of bodybuilding trainees with and without NSLBP. Among the 150 participants, a preliminary questionnaire indicated that 90 participants (60%) had NSLBP. However, a more detailed assessment using the NPRS and RMDQ revealed that some degree of NSLBP was also present in the CON group. This study has focused on TMG, an advanced method for assessing muscle function by measuring radial displacement in response to electrical stimulation. Although TMG has operated on a similar fundamental principle as mechanomyography, it is specifically designed for stimulated muscle contractions and utilizes a unique mechanical sensor to detect radial displacement (Macgregor et al., 2018). However, since TMG evaluated muscle properties in a static state, its role in assessing dynamic muscle function has not been clearly established. Therefore, this study aimed to examine the relationship between TMG parameters and variables obtained from isokinetic dynamometry, a widely used tool in sports medicine area, to determine the functional significance of the five key components of TMG. The findings of this study revealed significant negative correlations between the Tc, Tr, and Td of the RA and ES with PT and WR of the trunk flexor and extensor.

When analyzing the general patterns of variables derived from TMG, the Tc of the RA and ES muscles typically appears shorter in healthy muscles, whereas weaker muscles exhibit a relatively prolonged response time (Bibrowicz et al., 2024). As shown in the results of this study, a shorter Tc, as observed in datasets, reflects well-maintained neuromuscular control and responsiveness in the CON group, whereas a prolonged Tc may indicate muscle fatigue, weakness, or impaired neuromuscular function in the NSLBP group. Tc primarily represents the velocity of muscle fiber contraction and is strongly associated with the ratio of slow-twitch to fast-twitch fibers (Šimunič et al., 2018). Muscles containing a greater proportion of slow-twitch fibers tend to display longer Tc values, whereas those dominated by fast-twitch fibers typically demonstrate shorter Tc (Pus, Paravlic & Šimunič, 2023). This parameter is frequently employed to evaluate muscle fatigue, recovery status, and training adaptations. Temporal variations in Tc can reflect neuromuscular changes, muscle damage, or performance-related adaptations. In the context of injury assessment, an extended Tc may indicate compromised contractile capacity resulting from neuromuscular inhibition, disuse, or injury (Dahmane et al., 2001; Šimunič et al., 2011), which aligns with the findings of the present study. Tr, defined as the time between 90% and 50% of muscle relaxation, reflects the speed of muscle relaxation. A shorter Tr indicates faster muscle relaxation, which is generally associated with a normal physiological state. In contrast, a prolonged Tr may suggest increased muscle fatigue, potential muscle damage, or excessive muscle tension as similar results of this study. Td, defined as the time between the electrical impulse and 10% of the contraction, represents neuromuscular response time. A shorter Td indicates an appropriate neuromuscular response, whereas a prolonged Td suggests delayed neural conduction or impaired muscle responsiveness (Šimunič et al., 2011). As observed in the results of this study, the shorter Td in the CON group indicates better neuromuscular control and responsiveness, whereas the relatively prolonged Td in the NSLBP group may suggest muscle fatigue, weakness, or impaired neuromuscular function. These findings suggest that when Tc, Tr, and Td of the RA and ES, as measured by TMG in a static state, are slower or lower, the trunk flexor and extensor muscles can exhibit normal muscle function during dynamic trunk contractions. Conversely, Dm and Ts of the RA and ES of TMG parameters exhibited significant positive correlations with PT and WR of trunk flexor and extensor performance. For Dm, a higher Dm reflects reduced muscle tension or increased flexibility, while a lower Dm suggests heightened muscle stiffness or an increased risk of potential injury (Reeves et al., 2005; García-García et al., 2013). It is not uncommon for Tc and Dm to change at uneven rates. In such cases, we propose that the change in Tc, independent of Dm, is primarily influenced by variations in the contraction rate, as indicated by Vc (Valencic & Knez, 1997). Ts, defined as the duration for which a twitch is sustained, is measured as the time between 50% of Dm on either side of the twitch curve. A prolonged Ts reflects an improved capacity to sustain muscle contraction, while a shorter Ts suggests increased muscle fatigue or reduced endurance (Tous-Fajardo et al., 2010). In the present study, the CON group exhibited a longer Ts, indicating superior neuromuscular control and responsiveness, whereas the shorter Ts observed in the NSLBP group may suggest muscle fatigue, weakness, or neuromuscular dysfunction. Eventually, higher or longer values of Dm and Ts, as measured by TMG, may indicate that the trunk flexor and extensor muscles exhibit normal muscle function during dynamic contractions.

The relationship between contractile properties and geometric changes during muscle contraction has been analyzed using real-time brightness mode ultrasound to track instantaneous variations in gastrocnemius muscle fascicle length (Šimunič et al., 2011). Dick & Wakeling (2017) simultaneously measured torque and geometric changes, revealing that tension is generated in synchronization with fascicle length alterations. Furthermore, surface mechanomyography has been shown to effectively capture muscle fiber expansion during contraction, demonstrating a strong correlation between mechanomyography amplitude, torque oscillations, and fascicle length variations. These findings reinforce the concept that muscle functions as a near-constant volume system, where fiber shortening is accompanied by thickening, as reflected in muscle surface displacement and tendon tension (Macgregor et al., 2018). Moreover, while TMG enables accurate and efficient muscle assessment, studies investigating the factors contributing to muscle strength variations within TMG and their relationship with variables obtained through isokinetic dynamometry remain limited. In other words, investigating the relationship between muscle surface displacement tracking and isokinetic muscle contraction characteristics, and applying this approach to NSLBP patients, could have potential applications in both sports’ performance and rehabilitation. Based on the previous studies, this study an analysis of the relationships among these variables revealed that at an isokinetic angular velocity of 90°/sec, PT and WR of the TEF muscles were higher when Tc, Tr, and Td were shorter or lower, whereas PT and WR were lower when Tc, Tr, and Td of the RA and ES were longer or higher. Conversely, PT and WR of the TEF muscles were lower when Dm and Ts of the RA and ES were lower but increased when Dm and Ts were higher. Similarly, at an isokinetic angular velocity of 30°/sec, PT and WR of the TEF muscles were higher when Tc, Tr, and Td of the RA and ES were shorter or lower and decreased when these parameters were longer or higher. Ultimately, it was observed that the correlation patterns varied slightly depending on changes in isokinetic angular velocity.

Distinctive features of TMG factors and isokinetic TEF torques

When individuals experience LBP, they naturally attempt to minimize discomfort by reducing their range of motion and exerting less force. Non-specific LBP most commonly occurs when lifting heavy objects such as bodybuilding training, and if left unaddressed, it may progress to chronic pain or structural deformities (Price, 2021). As discussed earlier, TMG and isokinetic dynamometry are closely associated and can be effectively utilized during the early stages of NSLBP. The findings of this study demonstrated their utility in identifying the characteristics of individuals with and without NSLBP, thereby facilitating appropriate interventions. In this study, the NSLBP group demonstrated significantly prolonged Tc, Tr, and Td values for the RA and ES, whereas Dm, Ts, and Vc for both muscles were significantly reduced than those of the CON group. Moreover, the NSLBP group exhibited significantly lower PT and WR in trunk flexor and extensor, with a more pronounced deficit observed in the trunk extensor compared to the trunk flexor. These findings suggest potential neuromuscular impairments in individuals with NSLBP (De Oliveira Meirelles, De Oliveira Muniz Cunha & Da Silva, 2020), highlighting the importance of targeted interventions to improve trunk muscle function in the bodybuilding trainees.

Since LBP is inherently subjective and variable, accurately assessing its influencing factors—such as physical, psychological, emotional, and environmental conditions—is crucial (Bláfoss, Aagaard & Andersen, 2019). In this study, although participants in the CON group reported no LBP prior to group classification, responses from the back pain-related questionnaires revealed the presence of underlying, subclinical symptoms indicative of potential LBP. According to previous studies, the primary causes of sports injuries include excessive training, improper training methods, anatomical limitations, lack of flexibility, and muscle imbalances, with lower back injury related to weight training consistently ranking among the top two injury sites for weightlifters—accounting for 23% to 59% of all injuries—and most often associated with the squat or deadlift (Ross, Han & Slover, 2023). In the context of bodybuilding, injuries are often attributed to inadequate exercise techniques, insufficient knowledge, poor instruction from trainers, and excessive tension (Bonilla et al., 2022). In addition, among the various causes of back pain, weightlifters are commonly diagnosed with muscle strains, ligament sprains, degenerative disc disease, disc herniation, spondylolysis, spondylolisthesis, or lumbar facet syndrome. Standard treatments often fail to fully alleviate pain or prevent recurrence. Since most athletes aim to continue weightlifting, effective management should emphasize lifting-specific modifications, including improved technique and addressing mobility and muscular imbalances (Ross, Han & Slover, 2023). Bodybuilding is a form of physical training that systematically stimulates the body through various methods to achieve optimal development, ultimately fostering both physical and mental self-fulfillment. Given these characteristics, bodybuilding plays a significant role in the occurrence and prevention of exercise-related injuries (Mangano et al., 2015). Considering the results of previous studies alongside the findings of the present study, it is evident that training for bodybuilding places a significant load on the muscles surrounding the trunk.

TMG and isokinetic dynamometry, both historically and currently utilized, provide valuable insights for developing effective treatment strategies for the LBP patients (Park, 2020). Given that the trunk flexor and extensor play a fundamental role in spinal support, integrating these two assessment tools to measure both static and dynamic trunk muscle function may yield more clinically relevant findings, ultimately benefiting patient outcomes. Even based on the results of this study alone, distinct characteristics were identified in the static muscle function parameters measured by TMG when comparing the trunk muscles of patients with lower back pain to those of healthy young participants without back pain. The primary variable in TMG, Dm, measures the maximum muscle displacement during contraction, where a lower Dm may indicate increased stiffness, muscle rigidity, or injury risk, while a higher Dm suggests lower muscle tension or greater flexibility (Reeves et al., 2005; García-García et al., 2013). In this study, the Dm values derived from the abdomen and back muscles were lower in the NSLBP group, while higher values were observed in the CON group, aligning with the findings of previous studies (Yeom et al., 2023). Typically, Tc is shorter in the absence of muscular impairments; however, it tends to be prolonged in the presence of muscle fatigue, weakness, or neuromuscular control deficits (Bibrowicz et al., 2024). Consistent with the findings of this study, Tc of the RA and ES was shorter on both the left and right sides in the CON group compared to the NSLBP group, with a similar trend observed in the mean Tc. According to various studies, Ts represents the duration for which Tc is maintained. A shorter Ts may indicate muscle fatigue or reduced contraction endurance, whereas a longer Ts is considered indicative of better contractile capacity (Tous-Fajardo et al., 2010). In the results of this study, the Ts values derived from the RA and ES were significantly lower in the NSLBP group compared to the CON group, suggesting diminished muscle function associated with lower back pain. Specifically, this finding suggests that the shorter Ts observed in the NSLBP group may reflect altered neuromuscular function, possibly associated with muscle fatigue, weakness, or impaired motor unit recruitment. In our view, these changes could be indicative of adaptive or maladaptive responses to chronic low back pain, warranting further investigation. Tr represents the time it takes for the muscle to transition from 90% to 50% of its maximal displacement during relaxation (Poggesi, Tesi & Stehle, 2005). A prolonged Tr may indicate increased fatigue, muscle damage, or excessive tension, whereas a shorter Tr suggests quick relaxation, typically reflecting a normal state. In this study, the Tr values derived from the abdomen and back muscles were longer in the NSLBP group, while shorter values were observed in the CON group, consistent with the findings of previous studies. In addition, Td represents the time required to reach 10% of the Dm (Dahmane et al., 2001). A prolonged Td may indicate delayed nerve conduction or impaired muscle response, whereas a shorter Td reflects an appropriate neuromuscular response time (Šimunič et al., 2011). In this study, the Td values derived from the RA and ES were longer in the NSLBP group, while shorter values were observed in the CON group, aligning with the findings of previous studies. Meanwhile, the Vc of a muscle, calculated as Dm/(Tc + Td), is considered an indicator of muscle health, with lower values suggesting potential issues within the muscle group and higher values indicating healthier muscles (Valencic & Knez, 1997). In this study, the Vc values derived from the RA and ES were lower in the NSLBP group compared to the CON group, confirming impairments in the RA and ES muscles that constitute the trunk.

The isokinetic dynamometer revealed the degree of development of trunk extensors relative to trunk flexors in the healthy control group without back pain (Yahia et al., 2011; Merati et al., 2004). In this study, the PT and PTBW of the trunk flexor measured at 90°/sec were lower in the NSLBP group compared to the CON group. Similarly, the PT and PTBW of the trunk extensor were significantly lower in the NSLBP group than in the CON group. However, while WR and WRBW were lower in the NSLBP group compared to the CON group, no significant differences were found in the flexors, whereas significant differences were observed only in the extensors. These trends were similar at an isokinetic angular velocity of 30°/sec, suggesting that NSLBP has a more pronounced detrimental effect on the trunk extensors than on the flexors. These findings reflect the high activation of the ES muscles during multi-joint strength training exercises, such as squats and deadlifts, commonly incorporated into exercise training programs (Cormie, McGuigan & Newton, 2011). The flexion-to-extension ratio in all muscle groups serves as a valuable indicator for assessing muscle damage or the potential risk of injury. (BenMoussa Zouita et al., 2018) reported that the maximum torque ratio between the flexor and extensor muscles serves as an indicator of muscular joint balance. In this regard, Merati et al. (2004) reported that at 90°/sec, the trunk flexion-to-extension ratio in a pain-free control group of children was 0.89, whereas it was 1.00 in a group with low back pain. Similarly, Lee et al. (2012) found that at 60°/sec, the trunk flexion-to-extension ratio in middle-aged adults with LBP was 0.57. Conversely, Yahia et al. (2011) reported that at 90°/sec, the ratio was 0.85 in a group without chronic lumbar pain, while it was 1.34 in those with chronic lumbar pain. Cohen et al. (2002) observed that at 60°/sec, the ratio was 0.82 in a healthy control group but increased to 1.31 in individuals with LBP. The findings of our study contrast with those of Merati et al. (2004) and Lee et al. (2012) but align more closely with the results reported by Yahia et al. (2011) and Cohen et al. (2002). Specifically, at 90°/sec, the CON group exhibited a trunk flexion-to-extension ratio of 0.96 ± 0.18, whereas in the NSLBP group, it was 1.20 ± 0.36, showing a statistically significant difference between groups (Z = −4.421, p = 0.001, η2 = 0.133). This finding suggests that individuals with NSLBP have weaker extensor muscles relative to flexor muscles. Similarly, at 30°/sec, the CON group demonstrated a flexion-to-extension ratio of 1.02 ± 0.28, while the NSLBP group showed a ratio of 1.32 ± 0.49 (Z = −3.843, p = 0.001, η2 = 0.112), further confirming that in the presence of low back pain, the extensor muscles are weaker compared to the flexor muscles.

Ultimately, this study confirmed that trunk flexor and extensor muscle characteristics assessed using TMG and isokinetic dynamometry effectively reflect the differences between bodybuilding trainees with and without NSLBP. Specifically, the findings revealed an inverse relationship between the PT and WR of the TEF muscles and the parameters Tc, Tr, and Td. Higher PT and WR values were associated with lower Tc, Tr, and Td, whereas lower PT and WR values corresponded to higher Tc, Tr, and Td. Additionally, a direct relationship was observed between PT, WR, and Dm and Ts, with higher PT and WR values linked to increased Dm and Ts, and lower PT and WR values associated with decreased Dm and Ts. Furthermore, individuals with NSLBP exhibited distinct muscle characteristics compared to healthy controls. They demonstrated higher Tc, Tr, and Td values and lower Dm and Ts values in the RA and ES muscles. Isokinetic strength assessments further indicated that the NSLBP group had reduced trunk flexor and extensor strength compared to the control group, with extensor muscle weakness being more pronounced than flexor muscle weakness.

However, our study has several limitations. The study was conducted on young adults in their twenties who attended a single training center, and the relatively small sample size further limits the generalizability of the results to a broader population. Considering these limitations, future research should aim to examine the characteristics of non-invasive assessment tools across a more diverse and larger population from multiple locations to enhance the validity and applicability of the findings.

Conclusions

Nonetheless, while it is essential to recognize that this study has certain limitations, this study found a consistent relationship between muscle tone using a TMG and the assessment of trunk flexor and extensor using an isokinetic dynamometer. Additionally, it demonstrated a specific alteration in distinguishing between impaired and unimpaired trunks’ muscles due to NSLBP.

Supplemental Information

Comparative analysis and relationship of tensiomyographic and isokinetic muscle contractile assessments of rectus abdominis and erector spinae in bodybuilding trainees with nonspecific low back pain

Each data point represents the demographic and physical characteristics of bodybuilding trainees, as well as their TMG and isokinetic moment measurements. The 60 individuals highlighted in blue on the sheet belong to the control group (CON), whereas the 90 individuals in the unshaded section represent the nonspecific low back pain (NSLBP) group.