Evaluating large language models’ Arabic grammar error corrections and explanations

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Nicole Nogoy

- Subject Areas

- Artificial Intelligence, Computational Linguistics, Data Mining and Machine Learning, Natural Language and Speech, Text Mining

- Keywords

- Grammar error correction and explanations, Natural language processing, Large language models, GPT-4o, Arabic language, Gemini, Llama, Zero-shot, Few-shot

- Copyright

- © 2026 Mohi et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2026. Evaluating large language models’ Arabic grammar error corrections and explanations. PeerJ Computer Science 12:e3486 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3486

Abstract

Grammar Error Correction and Explanations (GECE) is considered a challenging task for under-resourced languages. Arabic is one such language as it lacks linguistic materials such as annotated corpuses, language supporting models, and even Natural Language Processing (NLP) tools. The study reported in the article was designed to evaluate the performance of Large Language Models (LLMs) in GEC and in generating adequate and relevant explanations for these corrections. The study explored the potential of the LLMs, GPT, Gemini, and Llama by using fine-tuning and two prompting techniques. The study also evaluated Arabic-specific LLM, ALLaM, using two prompting techniques. Additionally, the study compares the performance of LLMs with existing system called LanguageTool. The research examined whether prompting and fine-tuning techniques affected the quality of the explanations generated for the development of LLMs as useful tools in language learning. Human evaluation was applied to evaluate the quality and usefulness of the generated explanations. Our findings revealed that GPT-4o outperformed the other models based on the evaluation metrics used. The fine-tuned version of GPT-4o achieved the highest score of 78% in the Bilingual Evaluation Understudy (BLEU) metric, followed by the fine-tuned version of Llama and ALLaM’s version uses few-shot prompting, which both scored 74%. The F0.5 metric of the Chunk-LEvel Multi-reference Evaluation (CLEME) indicated that the fine-tuning technique significantly increased the metrics for GPT-4o, Gemini, and Llama, which had precision scores of 45%, 25%, and 29%, respectively. Furthermore, the fine-tuned version of Llama, ALLaM using few-shot prompting, and the fine-tuned version of GPT-4o achieved the highest average Character Error Rate (CER) of 10%, 10%, and 11%, respectively. Overall, our study shows that targeted training, starting with examples and progressing to fine-tuning, leads to significant gains in grammar error correction accuracy and explanation quality. Accordingly, LLMs can serve as a reliable resource to teach the Arabic Language and automate the editing process.

Introduction

As described in Miller (1951) and Dasopang (2025), language is the ability to speak. Developed from early childhood, it is an essential part of human expression and communication. In contrast, machines lack the intrinsic ability to understand or generate human language without the assistance of complex artificial intelligence (AI) techniques as stated by Raiaan et al. (2024). However, as mentioned in Turing (2009), for decades, researchers have focused on empowering computers with human-level reading, writing, and conversational skills. Deep learning, computational advances, and the availability of large text corpora have all contributed to the development of LLMs. These models can recognize complicated language patterns and create text that closely mimics human conversation because they employ neural architectures with billions of parameters and self-supervised training on vast unlabeled datasets (Shen et al., 2023). Recently, Large Language Models (LLMs) have shown remarkable progress in the field of Natural Language Processing (NLP). Models such as Generative Pretrained Transformer (GPT), Gemini, and Llama, have been applied in various NLP tasks like text generation, translation, question answering, and classifications as stated by Raheja et al. (2024) and Kobayashi, Mita & Komachi (2024a). A recent, comprehensive review by Fan et al. (2024) discussed the research trends in the period from 2017 to 2023, which included enhancements in essential algorithms, NLP tasks, and applications in fields such as medicine, engineering, social sciences and humanities.

OpenAI announced the first version of its GPT in 2018, called GPT-1, which is a transformer decoder-based model as stated by Ghojogh & Ghodsi (2020). Older versions of GPT have influenced subsequent models, including GPT-4 and GPT-4o, which resulted in significant advances in language processing and creation (Fan et al., 2024). As mentioned by Hurst et al. (2024), the GPT 4o version includes audio and video inputs in addition to the other inputs and was trained up to October 2023 on enormous datasets from various sources and materials. Meta introduced Llama3 in 2024, which is a herd of models that supports multiple languages, coding, reasoning and other features (Grattafiori et al., 2024). Meta improved the quantity and quality of data used for pre- and post-training Llama3 models. Llama3 was trained on 15T multilingual tokens. It has 8 billion, 70 billion, and 405 billion learnable parameters. Meta also developed extensions that support image and face recognition, in addition to speech understanding capabilities. Another multilingual LLM is Gemini, a family of transformer-decoder models, developed by Google. It has various versions: Ultra, Pro, Nano, and Flash, as mentioned by Anil et al. (2023). New enhancements to Gemini models include audio and video support (Georgiev et al., 2024). Finally, the Arabic Large Language Model (ALLaM) is a well-known LLM developed by the Saudi Data & AI Authority (SDAIA) to support fluency with understanding of Arabic and English languages (Bari et al., 2024). It was trained on a model from scratch with seven billion parameters and three models initialized by Llama2 on scales of seven billion, 13 billion, and 70 billion parameters.

Owing to the critical role of deep learning techniques and the processing of enormous volumes of data, such models have displayed exceptional capabilities in handling a variety of languages. However, since there are more than 7,000 spoken languages, current research is concentrating on scaling LLMs’ multilingual capabilities to handle more languages in various tasks as mentioned by Lai, Mesgar & Fraser (2024), Dang et al. (2024) and Mothe (2024). Arabic is one of the most challenging languages due to the complexity and the richness of Arabic morphology, as stated by Kwon et al. (2023). Moreover, Arabic is a collection of diverse languages and dialects in addition to Modern Standard Arabic (MSA).

As LLMs develop, investigation is now turning to linguistically complicated languages such as Arabic, whose complex morphology and distinct orthographic rules provide significant barriers to NLP. For around 300 million people, Arabic is their native language, and it is officially recognized in 27 states, as stated by Saiegh-Haddad & Henkin-Roitfarb (2014). Also, being the language of the Qur’an, it serves as the global holy and liturgical medium for Muslims. As highlighted in Ghazzawi (1992), there are different varieties of Arabic including classical Arabic, colloquial Arabic, and MSA. Classical Arabic is the language of the Qur’an and early Islam literature. MSA is the modernized form of classical Arabic and is the form used in media sources, speeches, academic writing, and so forth. Colloquial Arabic is the local dialect spoken in various countries. Arabic is highly organized and derivational, with a strong emphasis on morphology and syntax (AlOyaynaa & Kotb, 2023). Generally, while other language grammars are considered complex, Arabic grammar is unusually so, which makes grammar-checking a hard task. According to Selim (2018), learning grammar is critical for two reasons: first, to prevent the Quranic language from corruption, and second, to provide non-native speakers with a baseline from which to build a correct grasp of the language.

This study investigated LLMs in order to enhance their performance in two distinguished NLP tasks involving MSA grammar. The first task was grammar error correction (GEC), which basically entails identifying textual grammatical errors and correcting them (Zhang et al., 2023b; Wang & Yuan, 2024). Applying GEC to Arabic reveals challenges due to the complexity of Arabic grammar and features (Kwon et al., 2023). Grammatical mistakes are ordinary for anyone writing in any language. These mistakes can disturb readers and lead to miscommunication (Ingólfsdóttir et al., 2023). Therefore, GEC is considered essential for anyone, especially non-native speakers, to guide and provide them with instant feedback to facilitate their individual learning journey (Davis et al., 2024). The second task was Grammar Error Correction Explanation (GECE) which is associated with the GEC task. In it, the system explains the reasons for the grammatical corrections applied (Song et al., 2023). Generating explanations for grammatical error corrections is helpful for readers to get a deeper understanding of grammar rules of MSA (Song et al., 2023). Also, it clarifies concepts and reduces confusion by identifying and understanding mistakes. Exploring GECE in LLMs and enhancing it in several languages can result in LLMs fostering more effective learning experiences (Ye et al., 2024).

The purpose of the study was to investigate and evaluate the performance of four language models, GPT, Gemini, Llama, and ALLaM, in handling Arabic grammar correction and generating reliable explanations. Furthermore, the grammatical error correction performance of LLMs was compared against the existing tool, LanguageTool (https://github.com/languagetool-org/languagetool). We used two datasets, anual Arabic Spelling-Error Correction Corpus (Saty, Aouragh & Bouzoubaa, 2023) and the Arabic Grammar Corrections Dataset (https://huggingface.co/datasets/s3h/arabic-grammar-corrections), to train LLMs and evaluate their efficiency for Arabic GEC and explanation generation. This is achieved by fine-tuning the language models and adapting different prompting techniques (i.e., zero-shot and few-shot). The metrics used to evaluate these LLMs include Cosine Similarity, Bilingual Evaluation Understudy (BLEU), Levenshtein Distance, Word Error Rate (WER), CER (Charachter Error Rate), Chunk-LEvel Multi-reference Evaluation (CLEME), Generalized Language Evaluation Understanding (GLEU), and Recall-Oriented Understudy for Gisting Evaluation (ROUGE) as well as conducting human evaluation.

This research study was designed to answer the following questions:

-

How efficient can LLMs be in correcting Arabic grammar and explaining the corrections?

-

Do different prompting techniques affect the quality and clarity of explanations?

-

Which technique has the best performance: prompts or fine-tuning?

The main contributions of this article can be summarized as follows:

It investigates the performance of GPT-4, Gemini, Llama, and ALLaM language models in dealing with Arabic GEC and generating helpful explanations for the produced corrections.

It sheds light on strategies to enhance language model performance, such as prompt-based techniques and fine-tuning.

The remainder of the article will review the relevant literature on LLM, GEC and explanation, and different prompt engineering and fine-tuning techniques in the ‘Related Work’. ‘Methods’ details the methodology and research pipelines, including descriptions of the models, datasets, and evaluation metrics. ‘Discussion’ presents the data analysis and discusses the results for each model using different techniques. Finally, ‘Conclusions’ offers the study’s findings and conclusions.

Related work

LLMs are transformer-based AI algorithms trained on numerous datasets. They use deep learning to be capable of handling various tasks as mentioned in Marvin et al. (2023). Recent studies, such as La Cava & Tagarelli (2025), Yu et al. (2023), von Schwerin & Reichert (2024) and Liu et al. (2024), have discussed the difference between open-source and closed-source LLMs. According to La Cava & Tagarelli (2025), open-source LLMs, such as Llama, can be used freely for any purpose, whereas closed-source models, such as GPT and Gemini, limit interactions to API access and do not allow access to the pretraining data (von Schwerin & Reichert, 2024). LLMs have generally demonstrated superior capabilities to understand and generate languages, outperforming previous systems in various NLP tasks as stated by Kobayashi, Mita & Komachi (2024a).

Besides contributing significantly to recent NLP research, LLMs can also produce high-quality corrections in GEC like the GPT models (Creutz, 2024; Loem et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023a; Park et al., 2024). Additionally, recent studies have shown noticeable improvements in LLMs in producing relevant and meaningful explanations for GEC including GPT models, Qwen, DeepSeek and Llama as referred to by Kaneko & Okazaki (2023), Song et al. (2023), Li et al. (2024) and Ye et al. (2024). However, no research has explored GECE for Arabic yet. This is because Arabic GEC is quite challenging owing to the ambiguity of Arabic at the orthographic, morphological, syntactic, and semantic levels (Kwon et al., 2023; Alhafni et al., 2023; Ingólfsdóttir et al., 2023).

Grammar error correction

According to Bryant et al. (2023), writing is a learned skill and an essential form of communication that can be challenging for non-native language speakers. Fei et al. (2023) mentioned that the evolution of NLP applications can assist non-native speakers in improving their writing skills. Within any given sentence, a GEC task can automatically identify and rectify grammatical, orthographic, and semantic errors as highlighted by Kobayashi, Mita & Komachi (2024b). Previously, various approaches were implemented for GEC, such as classifiers, machine translation, edit-based approaches, and LLMs as detailed by Bryant et al. (2023). Current research focuses on applying GEC in LLMs, which is challenging according to Tang, Qu & Wu (2024). In Creutz (2024), three LLMs were evaluated, namel GPT-3.5, GPT-4, and Claude v1, using a prompt-based approach in correcting grammatical errors in beginner-level Finnish learner texts on different temperature settings due to the non-deterministic nature of LLMs. GPT-4 outperformed GPT-3.5 and Claude v1 on GEC task.

Similarly, several research articles such as Loem et al. (2023), Zhang et al. (2023a) and Park et al. (2024), have evaluated the performance of GPT-3 in GEC task by using prompt-based methods such as zero-shot and few-shot settings. As was detailed by Loem et al. (2023), they found that the performance of GPT-3 was effective when using appropriate instructions and clear examples. In addition to evaluating the performance of LLMs, Zhang et al. (2023a) evaluated their tolerance on texts containing different levels of noise/errors. The results showed that the level of noise can affect LLMs performance: the performance declines as the noise increases. Additionally, according to Park et al. (2024), LLMs performance increases when few-shot techniques are applied (increased number of examples).

Grammar error correction explanations

As discussed in the previous section, GEC can improve writing by detecting and correcting textual errors. However, understanding the reason for a particular correction and identifying the type of error in a GEC system will help language learners to continuously improve their skills by learning from their mistakes following effective feedback (i.e., explanations provided by GEC systems or LLMs) as described by Park et al. (2024). As noted by Song et al. (2023), GECE in LLMs is the task of explaining the reason for an applied correction. Kaneko & Okazaki (2023) proposed a method called controlled generation with prompt insertion (PI). In this method, corrected tokens are sequentially inserted in the LLM’s explanation output as prompts to guide the LLM to generate more useful and illustrative explanations. Their study showed that using the PI method, there was a notable increase in the LLM’s performance in explaining the reasons for corrections.

Another study by Song et al. (2023), developed a two-pipeline stage for LLMs to generate an explanation for each grammar correction as a pair of erroneous and corrected sentences. Human evaluation indicated that more than of the explanations produced by their pipeline method for German and Chinese were correct. Whereas in Li et al.’s (2024) article, the author used LLMs as explainers to train and provide explanations for their models to enhance their performance. Also, they used LLMs as evaluators to produce more reasonable Chinese GEC evaluations. One of their findings showed that their SEmantic-incorporated Evaluation framework displayed a significant performance, which made it a suitable evaluation tool for GEC in LLMs. Furthermore, Ye et al. (2024) introduced a benchmark featuring the design of hybrid edit-wise explanations. Each edit is structured as follows: error type, error severity level, and an error description that helps learners and guides them to clearly understand why and how the grammatical error was corrected.

Prompt engineering and fine-tuning

Prompt engineering is the process of crafting and optimizing prompts to acquire the desired responses from LLMs, as outlined by Marvin et al. (2023). According to White et al. (2023), a prompt is a series of instructions that unlocks the full potential of LLM by customizing and enhancing its capabilities. Prompts are crucial for leading LLMs to create meaningful and relevant content. Techniques such as fine-tuning, in-context learning (ICL), zero-shot and few-shot learning, tailor LLMs for specific tasks, as mentioned by Marvin et al. (2023).

As emphasized by Pajak & Pajak (2022), the fine-tuning technique uses a supervised learning process to train language models to perform effectively faster and with less power consumption in a specific task. ICL is a technique where the descriptions of tasks are provided in the prompt, as well as a few annotated task examples as described by Yao et al. (2024). Wei et al. (2021) created an instruction tuning method to improve both zero-shot and few-shot ICL. Moreover, Yao et al. (2024), through enhancing the construction of multiple ICL prompts, developed a new technique that produces confident predictions. By contrast, zero-shot prompting is a technique of plainly describing the information of a task without providing examples as outlined by Allingham et al. (2023). In addition to task information, the few-shot prompting technique includes multiple examples (Chen et al., 2023). Recent research has studied the application of prompt-based approaches in applying LLMs to GEC, concentrating on developing effective prompts that produces corrected sentences as detailed by Zeng et al. (2024). For example, in Kwon et al.’s (2023) study, they found that in-context few-shot learning effectively improved the performance of GPT-4. Conversely, Davis et al. (2024) observed that in some settings, zero-shot prompting is as competitive as the few-shot technique. Other studies, like that of Kaneko & Okazaki (2023), looked into different prompting strategies that improve LLMs’ explanation of corrections. Kaneko & Okazaki (2023) created a prompt insertion method to enhance the explanation generation of GPT-3 and ChatGPT models. Finally, Ye et al. (2024) used a fine-tuning strategy for edit extraction and a few-shot prompting technique to prompt GPT-4 to generate edit-wise explanations.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to discuss and evaluate Arabic grammar correction explanations using LLMs. We developed and compared different prompting techniques (zero-shot, few-shot) and targeted fine-tuning to encourage LLMs to deliver concise, well-structured explanations in Arabic. By systematically comparing various techniques and measuring both corrective performance and explanatory clarity, our study fills a fundamental gap and sets a framework for understandable, educationally relevant GEC systems for Arabic.

Materials and Methods

Experiment setting

In this article, to run and analyze the data, we used a Lenovo YOGA 9i with 16 GB RAM and 1T storage using a Windows operating system. Additionally, we utilized Python3 on Google Colab, running data on both CPU and T4 GPU environments.

Model selection

Selection of the language models in this study was based on the performance evaluations of recent studies (Lai, Mesgar & Fraser, 2024; Kwon et al., 2023; Raheja et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2023b). Our study involved prompting and fine-tuning several well-known models, including Open AI GPT-4o, Google Gemini, Meta Llama3, and SDAIA ALLaM. OpenAI newly developed GPT-4o (https://platform.openai.com/docs/models) family such as GPT 4o, GPT-4o mini, gpt-4-turbo, etc., that can be accessed via OpenAI API requests for prompting and fine-tuning purposes. Similarly, Google has developed new Gemini models (https://ai.google.dev/gemini-api/docs/models): Ultra, Pro, Flash, and Nano, which are designed for specific applications and can be accessed through Google AI Studio for both prompting and fine-tuning. Notably, Google documentation indicates that Gemini 1.5 Flash is the only model in the Gemini family currently available for fine-tuning; it imposes constraints on input size, limiting it to 40,000 characters, and output size, restricting it to 5,000 characters per training example. Meta (https://www.llama.com/docs/model-cards-and-prompt-formats/llama3_2/) has been iteratively enhancing its Llama models. This has culminated in the current version, Llama 3, which incorporates specific modifications in the prompt format. Furthermore, SDAIA and the National Center for AI (NCAI) have collaboratively developed a series of LLMs specifically tailored to support the Arabic language namely ALLaM (https://www.ibm.com/docs/en/SSYOK8/wsj/analyze-data/assets/ALLaM-1-13b-instruct-model-card.pdf). ALLaM is a pretrained model derived from Llama that has three variants: ALLaM-7B, ALLaM-13B, and ALLaM-70B. GPT has shown remarkable performance in GEC, as has Llama (Lai, Mesgar & Fraser, 2024; Kwon et al., 2023; Raheja et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2023b). However, there is no research using Gemini or ALLaM for GEC. Furthermore, the study compares the LLMs performance against the existing tool, LanguageTool, which is a multilingual AI-based grammar checker that supports Arabic language.

Datasets

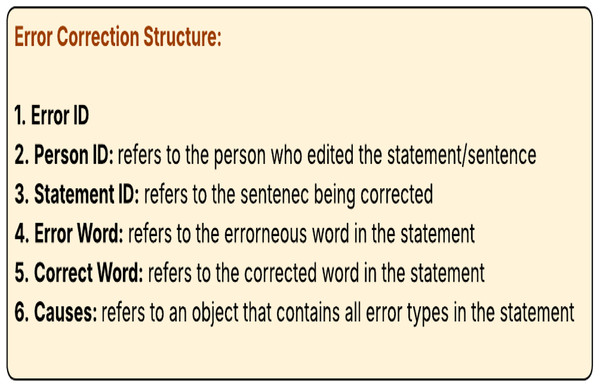

In this study, we used two datasets, a manual Arabic spelling-errors correction corpus (https://lindat.mff.cuni.cz/repository/xmlui/handle/11372/LRT-4763) and the Hugging Face Arabic GEC dataset (https://huggingface.co/datasets/s3h/arabic-grammar-corrections). Manual Arabic spelling-errors correction is a text corpus designed for Arabic spell-checking; it was compiled from various files edited by a group of individuals and published by Sudan University of Science and Technology (Saty, Aouragh & Bouzoubaa, 2023). The corpus serves Arabic NLP by providing a comprehensive and open Arabic spell check resource ready for further exploration and analysis. The corpus consists of 11,098 words containing 1,888 errors and 20 error types, structured into several sections starting with the person, the documents he/she edited, types of errors, and the specific errors made. Each section contains data that elaborate on its content, which assists researchers in extracting valuable insights. The corpus has an array of error objects, and each object has the keys shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Data structure available in manual Arabic spelling-errors correction corpus.

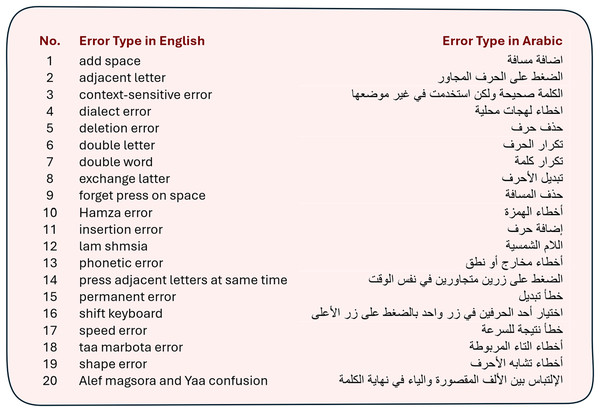

We chose this dataset to pre-train the base models—GPT-4o, Gemini Pro and Llama3—to create our fine-tuned models. According to the LLMs’ documentations, an average of 100 examples is generally sufficient to yield promising results. After data preprocessing, we compiled approximately 300 examples, meeting the recommended sample size outlined in each model’s documentation for pre-training the models. Figure 2 shows the 20 types of errors on which the LLMs were trained. These types of errors were used in the training corpus, the Manual Arabic Spelling-Errors Correction corpus.

Figure 2: Error types in the Manual Arabic Spelling-Errors Correction corpus.

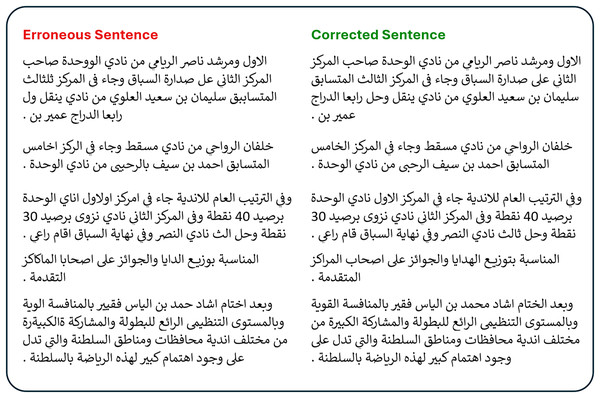

The second dataset was the Arabic GEC dataset shared on the Hugging Face platform. It has over 390,000 erroneous sentences and their corrections (reference sentences). We chose the first 2,000 records to evaluate the ability of both base and fine-tuned models in correcting erroneous sentences and explaining the purpose of corrections. Figure 3 presents a sample of the dataset.

Figure 3: Sample of Hugging Face Arabic GEC dataset.

Upon evaluating the fine-tuned models, we found that GPT-4o and Llama reproduced the training output format nearly identically. However, Gemini failed to generate the structured output on which it was trained, providing only error analysis without corrected sentences. This output prevented many rows from being evaluated by our similarity metrics. As a result, we filtered the Gemini outputs to include only those records containing corrected sentences, resulting in a cleaned dataset of 379 entries used in the analysis.

Approach

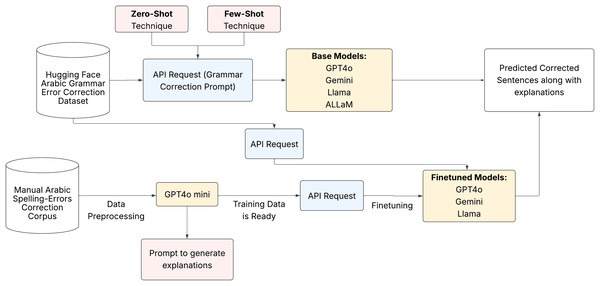

We aimed to prompt and fine-tune the chosen LLMs to evaluate their capabilities for Arabic GEC and GECE tasks. Figure 4 shows the pipeline of our full approach. We used particular prompts to produce precise corrections and meaningful explanations of the language models.

Figure 4: Experiment pipeline.

Data preprocessing

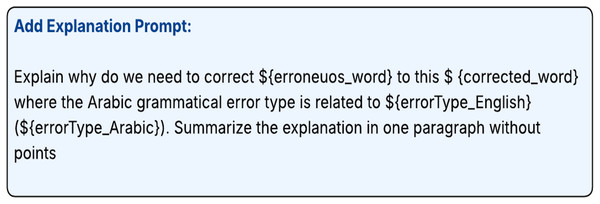

For fine-tuning, we first preprocessed the Manual Arabic Spelling Errors Correction corpus. Specifically, we adopted its output structure while excluding the first three keys: ‘documentID’, ‘statementID’, and ‘PersonID’. Each model requires a different training data format; however, they all follow the same principle of providing an input along with its corresponding output. To enhance the training data, we prompted GPT-4o-mini to include an additional key called “explanation” that provides the rationale behind each correction. This makes the output both informative, comprehensive and offers a complete understanding of the error correction process. Figure 5 shows the prompt used for generating explanations.

Figure 5: Add explanation prompt.

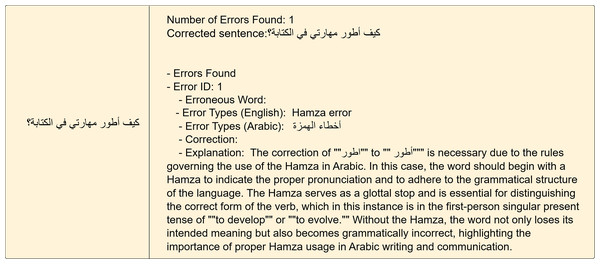

Figure 6 illustrates a sample of the training data. The first column represents the erroneous sentence, while the second column reflects the desired output structure as shown in Fig. 7.

Figure 6: Sample of the training data.

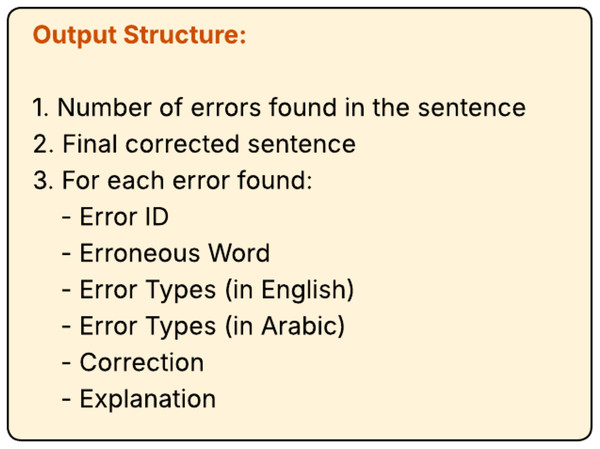

Figure 7: Output structure.

Model fine-tuning and prompting techniques

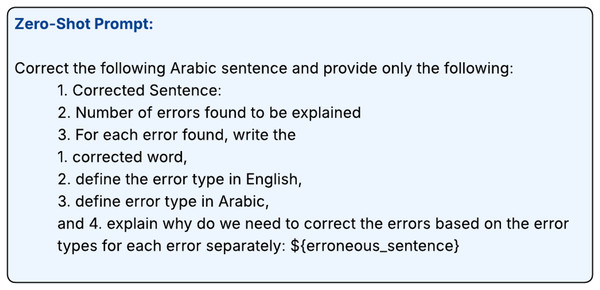

Fine-tuning is the process of training a pre-trained model on a more detailed dataset to enhance its performance on a certain task. As highlighted in Mathav Raj et al. (2024), researchers have shown that fine-tuning technique yields promising and more accurate results than creating a model from scratch. After preparing the training data for each model, we fine-tuned each model using its respective platform. For Llama, we used Laminiai, a third-party application to fine-tune the model, where a number of hyperparameters were adjusted using the default settings in order to improve stability and performance. The default learning rate used in Laminiai is 0.0009. Gemini was fine-tuned using Google AI Studio at a learning rate of 0.001 and the other default settings, while GPT-4o was fine-tuned using the recommended hyperparameters of OpenAI using API requests. For prompting, we employed two common techniques: zero-shot and few-shot prompting. The zero-shot approach prompts LLMs without providing examples to measure their natural capabilities. We asked each LLM to correct the erroneous sentence and provide the corrected sentence, the number of errors found in the sentence (and for each error, the corrected word and the type of error, identified in English and Arabic), and finally, a detailed explanation for the corrections applied. Figure 8 shows the zero-shot prompt.

Figure 8: Zero-shot prompt.

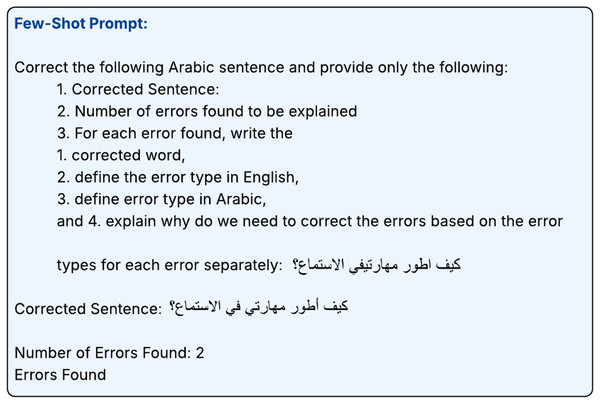

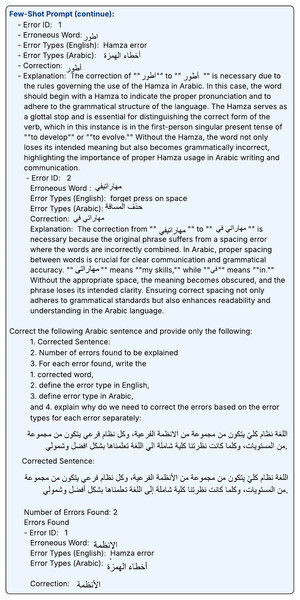

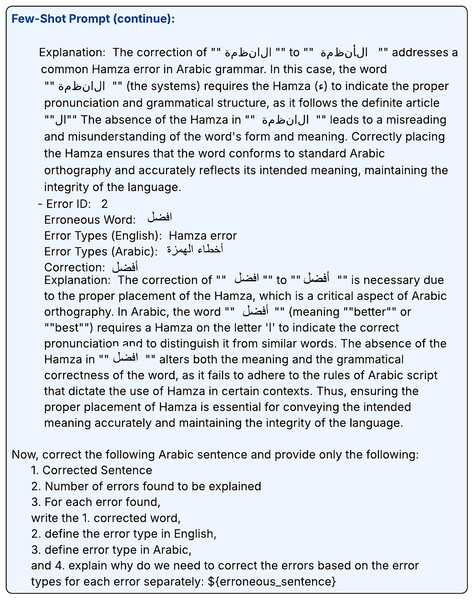

In contrast, the few-shot approach uses a few examples in the prompts to supervise the models to generate the desired output format and style. In this approach, we used the same prompt used in zero-shot in addition to two examples as shown in Figs. 9, 10, 11.

Figure 9: Few-shot prompt-1.

Figure 10: Few-shot prompt-2.

Figure 11: Few-shot prompt-3.

Evaluation method

Method

In this article, we used the cross-dataset evaluation method in which the dataset used to train the LLMs is different from the dataset used to evaluate the performance and accuracy of both base and fine-tuned models. As mentioned in the previous sections, we used the Manual Arabic spelling-errors correction corpus to train the fine-tuned models and the Hugging Face Arabic GEC dataset to evaluate them.

Performance metrics

Several performance metrics were used to measure the effectiveness of LLM in the generation of Arabic GEC and GECE. What distinguishes these metrics is their ability to capture various aspects of error correction while ensuring an inclusive evaluation of the language models’ performance.

CLEME is a reference-based metric used for evaluating GEC systems. It aims to provide unbiased F0.5 scores as referenced by Ye et al. (2023). CLEME works on avoiding bias in GEC multi-reference assessment by converting the source, hypothesis, and references into consistent chunk sequences categorized as unchanged, corrected, or dummy. To measure the alignment of edits with these chunk boundaries across multiple references, CLEME calculates three statistics—the In-Corrected-Chunk (ICC) ratio, In-Unchanged-Chunk (IUC) ratio, and Cross-Chunk (CC) ratio-using Eqs. (1), (2), and (3):

(1)

(2)

(3) where M is the number of edits in a remaining reference, and represents a single edit. returns 1 if an edit is included in a corrected or dummy chunk, whereas returns 1 if is included in an unchanged chunk.

Another metric was ROUGE, as outlined by Lin (2004), it is a collection of measurements for evaluating the quality of computer-generated summaries by comparing them to human-created reference summaries. It computes the overlap of n-grams, word sequences, and word pairs in the produced and reference summaries using Eq. (4):

(4) where represents the length of the n-gram, , and Count_match ( ) is the maximum number of n-grams overlapping in a candidate summary and a set of reference summaries. GLEU, designed for GEC, is a variant of BLEU considering both the source and reference results in a more accurate representation of human judgment, as discussed by Napoles et al. (2015). It evaluates the n-gram overlap between the corrected output and reference sentences, penalizing superfluous alterations that do not correspond to the reference. The GLEU score is calculated as a weighted precision of n-grams, with a shortness penalty comparable to the BLEU to account for recall. Equation (5) shows the formula for GLEU:

(5) where C are the sentences, R are the references, S is the source, BP represents the brevity penalty, represents the modified n-gram precision and is the weight of n-gram precision.

For Arabic sentences, Cosine Similarity is a well-known metric typically implemented using an Arabic tokenizer. Using Eq. (6), we computed the cosine of the angle between the sentence vectors A and B, which contain lexical and contextual information. Similarity scores approaching 1 indicate a high degree of similarity.

(6)

BLEU rates translation units-typically sentences-by comparing them with high-quality reference translations as described by Sallam & Mousa (2024). BLEU calculates an n-gram overlap score for each segment of the corpus, then averages these scores over all segments, as outlined by Papineni et al. (2002). It works by identifying contiguous sequences of n words in the candidate and reference texts; higher values indicate greater overlap and, thus, better fidelity to the reference, as outlined in Eq. (7).

(7) where BP is the brevity penalty, is the weights for each n-gram and is the precision of n-grams.

In analysis of variance (ANOVA), the means of three or more groups are compared to determine whether they differ significantly from one another as mentioned by Keselman et al. (1998). In Eq. (8), the total variability of the study is decomposed into variance between groups and variance within groups, which are then compared using an F-statistic calculated from the variance within and between groups. As in Keselman et al. (1998), it shows that the resulting p-value indicates whether the observed differences in group means are statistically significant. In this study, ANOVA was employed to assess the significance of our findings across the various analyses and tests conducted.

(8)

WER measures the percentage of word-level errors—substitutions S, deletions D, and insertions I-needed to convert a system’s output into the reference transcript, normalized by the reference length N as shown in Eq. (9). As stated in Hanamaki, Kirishima & Narumi (2024), it computes the number of errors in the sentence corrected by the model compared to the reference. Due to its ability to capture both insertions and deletions, this metric is widely recognized as effective for evaluating grammar correction systems (Salhab & Abu-Khzam, 2024; Li et al., 2025).

(9)

CER follows the same principle at the character level, counting character substitutions , deletions and insertions over the total reference characters M as shown in Eq. (10) from Hanamaki, Kirishima & Narumi (2024). This kind of evaluation makes it useful for morphologically rich languages or very short texts. It is beneficial for identifying errors at the character level, which can be critical for detecting fine spelling variations and minor correction inaccuracies. Smaller scores indicate closer fidelity to the reference.

(10)

The Levenshtein Distance (LD) between two sentences and is the smallest number of character-level insertions I, deletions D, or substitutions S needed to turn sentence into sentence as shown in Eq. (11). It measures how different two strings are from each other. This metric aids GEC systems in assessing the similarity of sentences, where minor word variations must be identified and fixed as outlined by Naziri & Zeinali (2024) and Mehta et al. (2021).

(11)

Finally, Fleiss’ Kappa is an inter-rater reliability metric that measures the degree of agreement between two or more raters. It judges subjects independently, through a scale consisting of categories as referenced by Moons & Vandervieren (2023) and Falotico & Quatto (2015). This metric indicates which LLM achieved the highest agreement among all raters and in which criteria (i.e., fluency, grammar correction, etc.). means the mean of the overall observed proportion of agreement and is the expected proportion of agreement by chance as shown in Eq. (12).

(12)

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated two main strategies for Arabic GEC with explanations: prompting techniques (i.e., zero-shot and few-shot prompting) and fine-tuning of pretrained models (GPT-4o, Gemini, and Llama).

Automatic evaluation

Automatic evaluation metrics are necessary to evaluate the performance of LLMs in the GEC task.

Similarity metrics

In order to measure the correction accuracy of our models’ corrected sentences, we used the following similarity metrics: BLEU, GLEU, ROUGE, Cosine Similarity, and CLEME.

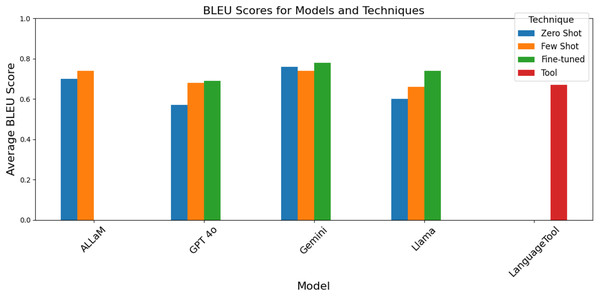

The BLEU evaluation, compared the corrected sentences produced by our models to the gold-standard (baseline) sentences by checking how closely the model’s correction fits to the human edits. As illustrated in Fig. 12, the fine-tuned version of GPT-4o outperformed the other four models in addition to LanguageTool, achieving a BLEU score of 78%. It was closely followed by the fine-tuned Llama and ALLaM (few-shot), both with BLEU scores of 74%. Also, we note that both the fine-tuning and the few-shot techniques improved the GEC of Gemini where the BLEU score have increased from 57% (zero-shot) to 69% and 68% respectively. Additionally, LanguageTool’s performance is on par with fine-tuned Gemini and Llama when prompting techniques are used.

Figure 12: BLEU scores grouped by the model and technique.

Notably, the few-shot prompting consistently improved over zero-shot baselines, though the magnitude varied by model. This can be noticed as well in the fine-tuned versions of the models which implies that with dedicated training, the models can be improved. However, GPT-4o using zero-shot prompting outperformed GPT-4o using few-shot prompting, unlike other models. We noticed that around 250 records resulted from GPT-4o using few-shot prompting that yielded generic rejection messages as shown in Fig. 13.

Figure 13: Generic rejection messages.

GPT-4o users have observed this behavior and reported it in OpenAI community chats. According to OpenAI’s documentation, when using structured outputs with user-generated input, the model may occasionally refuse to fulfill the request for unknown safety reasons. The zero-shot setting, without customized prompts, leads to more consistent corrections and higher GPT-4o scores when using prompting techniques. Table 1 shows the full BLEU scores for the models and techniques. Better quality is indicated by higher BLEU scores, which measure how similar the corrected sentence generated by the model is to the reference sentence. That is, a higher BLEU score indicates that the model’s output is closer to the reference output in GEC. This means that the model made fewer mistakes and produced more accurate and grammatically correct results.

| Model name | Technique | Average score |

|---|---|---|

| ALLaM | Zero shot | 0.70 |

| Few shot | 0.74 | |

| Gemini | Fine-tuned | 0.69 |

| Zero shot | 0.57 | |

| Few shot | 0.68 | |

| GPT-4o | Fine-tuned | 0.78 |

| Zero shot | 0.76 | |

| Few shot | 0.74 | |

| Llama | Fine-tuned | 0.74 |

| Zero shot | 0.60 | |

| Few shot | 0.66 | |

| LanguageTool | NA | 0.67 |

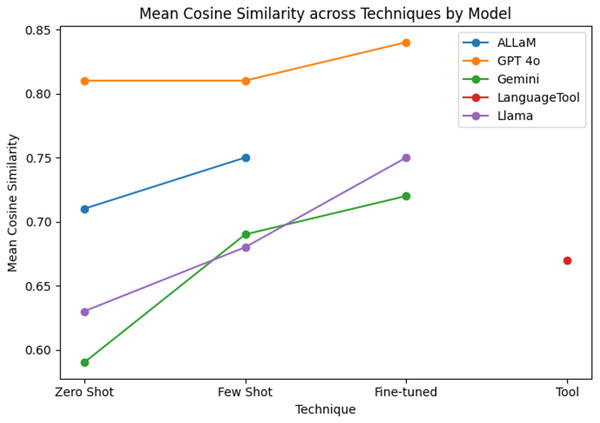

As shown in Table 2, the fine-tuning technique improved the average Cosine Similarity scores to 84% for GPT-4o, 75% for Llama, and 72% for Gemini. Also, it is notable that our fine-tuned models outperformed LanguageTool. Remarkably, ALLaM, which is a pretrained model derived from Llama, reached 75% when given a few prompt examples, whereas our own fine-tuned Llama hit 75% outright in a zero-shot setting. As a result, our model matches ALLaM’s best performance without relying on additional examples, indicating that parameter-level tuning is just as effective as prompt-based adaptation and possibly even more effective with additional training. In contrast to the BLEU evaluation, the original and cleaned Gemini fine-tuned outputs yielded the same cosine score because embedding models do not map empty inputs to zero vectors. Instead, they assign a learned neutral embedding (often near the centroid of the embedding space), so including those empty cases leaves the average Cosine Similarity essentially unchanged.

| Model name | Technique | Average score |

|---|---|---|

| ALLaM | Zero shot | 0.71 |

| Few shot | 0.75 | |

| Gemini | Fine-tuned | 0.72 |

| Zero shot | 0.59 | |

| Few shot | 0.69 | |

| GPT-4o | Fine-tuned | 0.84 |

| Zero shot | 0.81 | |

| Few shot | 0.81 | |

| Llama | Fine-tuned | 0.75 |

| Zero shot | 0.63 | |

| Few shot | 0.68 | |

| LanguageTool | NA | 0.67 |

Figure 14 reveals the clear, gradual improvement in model performance as we moved from generic to more task-focused training. Introducing just a few illustrative examples via few-shot prompting yielded a slight boost over the zero-shot baseline, and fine-tuning each model to correct the sentences and explain the corrections drove the highest scores. This pattern underscores the value of progressively more targeted training—first by example, then by direct adaptation—for specialized language processing tasks.

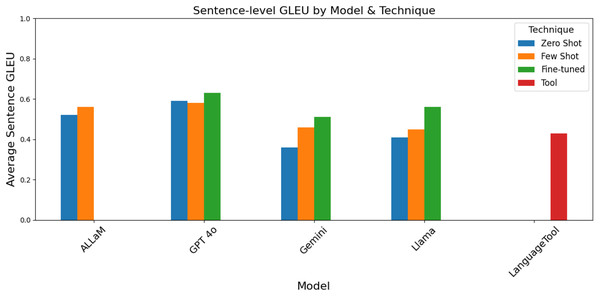

Figure 14: Cosine similarity scores grouped by the model and technique.

Figure 15 and Table 3 indicate that the fine-tuned GPT-4o delivered the highest sentence-level overlap of any model, technique, and even the existing tool. LanguageTool’s score is similar to both ALLaM and Gemini when prompting techniques are used. Few-shot prompting also resulted in consistent gains for both ALLam and Llama, reflecting the benefit of even a small number of examples. In contrast, Gemini’s original fine-tuned version produced an abnormally low average due to empty or mismatched outputs, but cleaning those records raised its GLEU from just 10% to 51%, bringing it back in line with the other methods.

Figure 15: GLEU scores grouped by the model and technique.

| Model name | Technique | Average score |

|---|---|---|

| ALLaM | Zero shot | 0.52 |

| Few shot | 0.56 | |

| Gemini | Fine-tuned | 0.51 |

| Zero shot | 0.36 | |

| Few shot | 0.46 | |

| GPT-4o | Fine-tuned | 0.63 |

| Zero shot | 0.59 | |

| Few shot | 0.58 | |

| Llama | Fine-tuned | 0.56 |

| Zero shot | 0.41 | |

| Few shot | 0.45 | |

| LanguageTool | NA | 0.43 |

The fine-tuned version of GPT-4o exhibited the strongest lexical overlap with a ROUGE score of 74%, with its zero-shot variant nearly matching it, while few shot prompting slightly boosted ALLaM and Llama scores to be 71% and 65%, respectively, as shown in Table 4. The score of Gemini’s cleaned fine-tuning version was 70%, bringing it on par with ALLaM and Llama few-shot prompting and greatly closing the gap from GPT-4o. Overall, the observations show that fine-tuning generally improved ROUGE scores across models.

| Model name | Technique | Average sScore |

|---|---|---|

| ALLaM | Zero shot | 0.68 |

| Few shot | 0.71 | |

| Gemini | Fine-tuned | 0.70 |

| Zero shot | 0.56 | |

| Few shot | 0.63 | |

| GPT-4o | Fine-tuned | 0.74 |

| Zero shot | 0.74 | |

| Few shot | 0.71 | |

| Llama | Fine-tuned | 0.71 |

| Zero shot | 0.60 | |

| Few shot | 0.65 | |

| LanguageTool | NA | 0.62 |

As shown in Table 5, in all the models, CLEME results revealed that the fine-tuning technique consistently produced the strongest error correction performance. Particularly, the fine-tuned GPT-4o achieved the highest F0.5 score of 45% and accuracy 72% by substantially increasing precision from 26% to 40% while maintaining higher recall 84%. Comparatively, zero-shot prompting achieved very high recall 95% for both GPT-4o and Gemini but struggled with precision 26% and 10%, respectively. This combined result indicates that the models identified most errors but introduced many false edits (false negatives).

| Model name | Technique | No. of sample | F0.5 | Accuracy | Precision | Recall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALLaM | Zero shot | 2,000 | 0.26 | 0.60 | 0.23 | 0.72 |

| Few shot | 2,000 | 0.28 | 0.61 | 0.25 | 0.61 | |

| Gemini | Fine-tuned | 379 | 0.25 | 0.62 | 0.22 | 0.68 |

| Zero shot | 1,919 | 0.14 | 0.53 | 0.11 | 0.95 | |

| Few shot | 1,998 | 0.18 | 0.55 | 0.15 | 0.93 | |

| GPT-4o | Fine-tuned | 1,999 | 0.45 | 0.72 | 0.40 | 0.84 |

| Zero shot | 1,999 | 0.31 | 0.63 | 0.26 | 0.95 | |

| Few shot | 1,995 | 0.29 | 0.61 | 0.25 | 0.94 | |

| Llama | Fine-tuned | 1,999 | 0.29 | 0.61 | 0.25 | 0.61 |

| Zero shot | 1,995 | 0.12 | 0.52 | 0.10 | 0.51 | |

| Few shot | 1,994 | 0.12 | 0.54 | 0.10 | 0.32 | |

| LanguageTool | NA | 2,000 | 0.07 | 0.51 | 0.06 | 0.28 |

After a few illustrative examples were provided in few-shot prompting, the models yielding modest precision gains where ALLam rising from 23% to 25% and Gemini’s from 11% to 15%, at the expense of slightly lower recall, resulting in small F0.5 improvements. Filtering out empty records for Gemini’s fine-tuned runs raised its F0.5 from 13% to 25%. Among the fine-tuned models, Llama’s precision jumped and its F0.5 score more than doubled 12% to 29%. ALLam also benefited, which indicated that training on a focused task delivers the greatest overall gains. Although LanguageTool achieved a similar accuracy range with Llama and Gemini, surprisingly, it has the lowest F0.5 and precision. Overall, we can conclude that fine-tuning matters since it raises the F0.5 for all models significantly above zero- and few-shot performance, up to 45% for GPT-4o, and provided the strongest and most consistent improvements in error correction quality. Higher F0.5 numbers means producing few false corrections while still capturing a good portion of real errors.

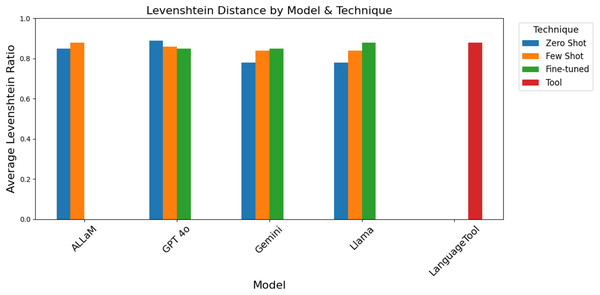

Error rate analysis

Levenshtein distance is the minimum number of character insertions, deletions, or substitutions needed to turn one string into another. Levenshtein distance is usually read as the number of edits, which is why we normalized it to a similarity ratio from 0 to 1 as shown in Table 6. The number of edits per sentence by itself can be misleading; what matters is the sentence’s length and what proportion of each sentence is changing. For example, in regard to GPT-4o’s fine-tuned model, on average, each sentence required around 19 character edits to match the reference; it is hard to decide if that is a good or bad number. However, its ratio shows that 85% of characters were correctly placed which indicates that the model outputs preserved most of the reference’s character sequence, which means high semantic similarity. Overall results showed ratios above 80% as shown in Fig. 16.

| Model name | Technique | Average distance | Average ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALLaM | Zero shot | 18.73 | 0.85 |

| Few shot | 13.48 | 0.88 | |

| Gemini | Fine-tuned | 19.28 | 0.85 |

| Zero shot | 27.47 | 0.78 | |

| Few shot | 18.98 | 0.84 | |

| GPT-4o | Fine-tuned | 18.89 | 0.85 |

| Zero shot | 11.43 | 0.89 | |

| Few shot | 14.65 | 0.86 | |

| Llama | Fine-tuned | 13.48 | 0.88 |

| Zero shot | 43.82 | 0.78 | |

| Few shot | 18.96 | 0.84 | |

| LanguageTool | NA | 13.31 | 0.88 |

Figure 16: Levenshtein distance results grouped by the model and technique.

Better corrections mean lower WER and CER which indicate that fewer errors remain. It’s notable that the WER and CER results lined up well with the other evaluation metrics used. GPT-4o’s fine-tuned model achieved an average WER of 23% and average CER of 11%. On average, then, only about 23% of the words, and 11% of the characters were erroneous, which is excellent for a grammar correction task. In second place come ALLaM zero-shot prompting and fine-tuned Llama, which both hit averages of 35% for WER and 10% for CER-in other words, 65% word accuracy and 85% character accuracy. Thus, overall, we can say that if a model has a WER of and a CER of , that means it produces strong corrections, which is the case with GPT-4o’s fine-tuned model, Llama’s fine-tuned model and ALLaM’s few-shot prompting technique, as shown in Table 7.

| Model name | Technique | Average WER | Average CER |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALLaM | Zero shot | 0.39 | 0.16 |

| Few shot | 0.35 | 0.10 | |

| Gemini | Fine-tuned | 0.33 | 0.15 |

| Zero shot | 0.52 | 0.25 | |

| Few shot | 0.44 | 0.15 | |

| GPT-4o | Fine-tuned | 0.23 | 0.11 |

| Zero shot | 0.35 | 0.11 | |

| Few shot | 0.37 | 0.14 | |

| Llama | Fine-tuned | 0.35 | 0.10 |

| Zero shot | 0.58 | 0.35 | |

| Few shot | 0.42 | 0.15 | |

| LanguageTool | NA | 0.45 | 0.12 |

Human evaluation

In order to evaluate whether explanations of grammatical errors are effective in helping Arabic learners understand corrections, we randomly selected a sample of the generated outputs from the best performing LLMs to be evaluated, which are fine-tuned GPT-4o, fine-tuned Gemini, fine-tuned Llama, and ALLaM using few-shot prompting. Four native speakers and experts were recruited as annotators to evaluate the predicted corrected sentences and explanations based on the criteria shown in Tables 8 and 9. The following elements show the structure of the sheet provided for the annotators for evaluation: sentence no., erroneous sentence, corrected sentence, erroneous words, errors explanations, and the following to be rated from one to three: grammatical correctness (GC), fluency (F), meaning preservation (MP), clarity of explanation (CE), usefulness for learning (UL), and accuracy (ACC).

| Corrected sentence evaluation | |

|---|---|

| Criterion | Description and Scale |

| Grammatical Correctness (GC) (Östling et al., 2023) | 1: Incorrect (major errors remain or new errors introduced) |

| 2: Partially correct (minor errors remain) | |

| 3: Fully correct (native-like) | |

| Fluency/Naturalness (F) (Östling et al., 2023) | 1: Awkward/unreadable |

| 2: Understandable but slightly unnatural | |

| 3: Smooth and natural Arabic | |

| Meaning Preservation (MP) (Östling et al., 2023) | 1: Meaning changed significantly |

| 2: Meaning mostly preserved with minor distortions | |

| 3: Meaning fully preserved | |

| Explanation evaluation | |

|---|---|

| Criterion | Description and scale |

| Clarity of Explanation (CE) (Kaneko & Okazaki, 2023) | 1: Hard to understand or ambiguous |

| 2: Understandable with some effort | |

| 3: Very clear and concise | |

| Usefulness for Learning (UL) (Kaneko & Okazaki, 2023) | 1: Not helpful (doesn’t guide correction) |

| 2: Moderately helpful | |

| 3: Very helpful and actionable | |

| Accuracy (ACC) (Kaneko & Okazaki, 2023) | 1: Incorrect explanation or misleading |

| 2: Partially correct explanation | |

| 3: Fully accurate explanation | |

As shown in Table 10, the fine-tuned GPT-4o model consistently outperforms the other models across all dimensions, achieving the highest scores in the six categories: GC, F, MP, CE, UL, and ACC. Furthermore, ALLaM using the few-shot prompting technique demonstrates competitive performance with GPT-4o in GC, F, and MP surpassing Gemini and Llama. However, it performs significantly worse in terms of CE, UL and ACC, demonstrating its limitations in explaining the corrections. Both fine-tuned Gemini and Llama achieve balanced results. Gemini shows relatively low performance in grammar correction, but produces more comprehensible explanations. In contrast, Llama achieves better grammar correction results than Gemini but slightly weaker explanation results. These human evaluation results demonstrate that the fine-tuned GPT-4o outperforms other models, confirming its potential as a reliable supportive learning tool for educational purposes.

| Model name | Technique | GC | F | MP | CE | UL | ACC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALLaM | Few-shot | 2.64 | 2.70 | 2.77 | 1.54 | 1.54 | 1.48 |

| Gemini | Fine-tuned | 1.76 | 1.66 | 1.82 | 2.36 | 2.25 | 2.26 |

| GPT-4o | Fine-tuned | 2.67 | 2.70 | 2.78 | 2.64 | 2.53 | 2.58 |

| Llama | Fine-tuned | 2.40 | 2.43 | 2.50 | 2.17 | 2.08 | 2.08 |

Furthermore, to ensure the objectivity of the human evaluation, we employed Fleiss’ Kappa which calculates the level of agreement among multiple raters. Table 11 shows Fleiss’ Kappa values which indicate fair agreement among the raters across the models.

| Categories | GC | F | MP | CE | UL | ACC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.26 | 0.22 | 0.26 |

ANOVA

ANOVA was performed to examine whether there were significant differences in performance between the four language models (ALLaM, Gemini, GPT-4o, and Llama) in various evaluation metrics (BLEU, GLEU, CS, ROUGE, LD, WER, and CER). when using the zero-shot technique, we obtained an F-value of 18.63 and a p-value of 7.99E−07, shown in Table 12, which is much lower than the critical F-value of 2.66. This indicated that there were statistically significant differences between the models scores. Likewise, the few-shot technique resulted in an F-value of 142.53 with a p-value of 3.56E−14, which is much smaller than the critical F-value of 2.66, meaning a significant difference. Similarly, the fine-tuning technique had an F-value of 101.26 with a p-value of 1.43E−09, which is significantly smaller than the critical F-value of 2.99, again indicating a strongly significant difference in performance between the models.

| Technique | F-statistic | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Zero shot | 18.63 | 7.98727616053634E−07 |

| Few shot | 142.53 | 3.5607348542138E−14 |

| Fine-tuning | 101.2583784 | 1.4297085278784E−09 |

In short, the ANOVA for the three techniques, zero-shot, few-shot, and fine-tuning, revealed varying levels of significance. As shown above, the results indicated that all the techniques exhibited significant changes in performance among the models.

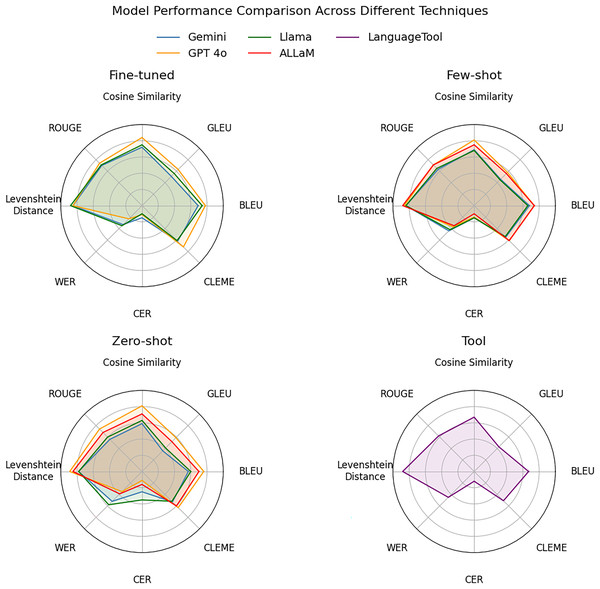

Figure 17 presents a better performance visualization of the evaluation metrics under the three adaptation techniques: fine-tuned, few-shot prompting, and zero-shot prompting in additional to LanguageTool. Radial placements closer to the center imply poorer performance, and those toward the outer edge show better outcomes. GPT-4o’s polygon consistently covers the biggest region in all three charts, indicating its supremacy in similarity measurements and low error rates. ALLaM, using few-shot prompting, slightly outperformed Llama in similarity and error metrics, while maintaining Llama’s exact results when fine-tuned. Gemini trailed behind but closed the gap on error rate, particularly when zero-shot prompting was used. Moreover, the visualization illustrates more clearly that LanguageTool achieves scores comparable to Gemini and Llama, but its performance remains lower than GPT-4o. Figure 17 clearly displays GPT-4o’s leading edge and the relative strengths and trade-offs of each model under varied techniques.

Figure 17: Radar chart for each technique.

Conclusions

Concluding remarks

This work demonstrated that cutting-edge LLMs can potentially be efficiently tailored to solve the two challenges of correcting Arabic grammatical errors and producing clear, educationally relevant explanations. We conducted methodical experiments employing four LLMs: GPT-4o, Gemini, Llama and ALLaM and adapted two techniques, prompting techniques such as zero-shot and few-shot, and fine-tuning to answer the research questions. We also compared the performance of the selected LLMs with an existing AI-based tool called LanguageTool. On top of that, we conducted human evaluation to examine the LLMs performance in correcting Arabic grammatical errors and explaining them.

When fine-tuned, GPT-4o obtained the highest average WER of 23% and CER of 11%, outperforming all other models in addition to LanguageTool. When zero-shot prompting was emploed, in terms of Levenshtein Distance, GPT-4o scored 11.43, which was the smallest amount of modification required to get the baseline sentence. Similarly, when fine-tuned, Llama achieved better scores across all assessment measures. ALLaM, which is an LLM developed on top of Llama, obtained scores identical to those of Llama’s fine-tuned version when few-shot prompting was applied. Gemini’s zero-shot prompting had the lowest score across all performance metrics. Also, LanguageTool performance was comparable to Llama and Gemini. Few-shot prompting outperformed fine-tuning on Cosine Similarity, GLEU, ROUGE, and WER but not on Levenshtein Distance or the CLEME measure.

All the techniques used, whether prompting or fine-tuning, led to significant performance changes, according to statistical analysis using one-way ANOVA, where all F-values exceeded critical levels at . According to these tests, the advantages we observed are notable and not the result of chance fluctuations. Taken together, our findings suggest that LLMs are strong tools that can explain Arabic grammatical correction and perform other NLP tasks. Prompting techniques and fine-tuning can unlock the full potential of models for Arabic, which is a difficult and under-resourced language.

Limitations

Despite the valuable findings, our study has several limitations. There are few publicly available Arabic corpora containing grammatically erroneous sentences with explicit mistake annotations and paired gold-standard corrections. Augmenting the sample size and training data may improve the robustness and reliability of the findings. Another limitation is the scarcity of Arabic-specific LLMs designed for answering inquiries or offering interpretations. Furthermore, we discovered that certain models, like Gemini, would occasionally fail to make any correction, resulting in empty records or “unable to respond” errors. Finally, the assessment of Arabic grammar correction and explanation employed several evaluation metrics that were not specifically designed for the Arabic language; a more accurate and more significant evaluation would be possible if metrics were developed or modified to account for Arabic’s distinct morphology and syntax.

Future work

Future research should utilize more expansive and varied Arabic corpora alongside annotation schemes that incorporate error types, facilitating multitask learning and the creation of error-specific prompts. Furthermore, additional human assessments covering other aspects, particularly those from teachers and language learners, will provide a more comprehensive understanding of the quality of the explanation. Our techniques can be validated in real-world teaching scenarios by integrating the LLMs into real-world educational tools, especially those targeted at non-native speakers. Additionally, we can explore how different prompt designs and languages can affect the LLMs performance. Finally, we can improve our understanding of the model performance by creating new evaluation metrics specifically designed to evaluate the precision and clarity of Arabic GECE.

Ethical considerations

Throughout this study, all datasets and models were sourced from publicly available academic resources. For closed-source LLMs, we use official APIs, so there are no ethical concerns about data ownership or access. The datasets contain no personally sensitive information. Some limitations remain, however: the data may not be representative of all types of grammatical errors, which may bias model performance towards certain patterns, and the generated explanations may sometimes be inaccurate or misleading. Therefore, we recommend using the system as a support along with human judgment rather than as a standalone replacement.

Reproducibility

This article evaluates the performance of LLMs in correcting and explaining Arabic grammatical errors. In addition, the article explores different techniques such as fine-tuning, zero-shot prompting, and few-shot prompting techniques. Also, we used two datasets, a Manual Arabic Spelling Error Correction corpus and the Hugging Face Arabic GEC dataset. Additional information can be found in the README file at GitHub (https://github.com/kousar-Mohi/Evaluating-LLMs-Arabic-Grammar-Error-Corrections-and-Explanations).