Deep learning-based automation framework for detecting multiple human disabilities in secure medical imaging systems

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Giovanni Angiulli

- Subject Areas

- Human-Computer Interaction, Computer Vision, Data Mining and Machine Learning, Security and Privacy, Neural Networks

- Keywords

- Deep learning, Transfer learning, Human disabilities, Image security, Object detection, Image classification, Computer vision

- Copyright

- © 2025 Hababeh et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2025. Deep learning-based automation framework for detecting multiple human disabilities in secure medical imaging systems. PeerJ Computer Science 11:e3381 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3381

Abstract

Deep learning has become an influential tool in the machine learning domain, enabling artificial intelligence systems to identify complex patterns in two-dimensional (2D) images and present precise predictions from massive datasets. One of the deep learning’s promising uses is human disabilities detection, a diagnostic field for enhancing the identification and classification of people with physical and sensory limitations. In this research, a deep learning framework is proposed for identifying and transferring six primary human disabilities, namely, blindness, Down syndrome, dwarfism, cerebral palsy, prosthetic arms, and prosthetic legs in a secure medical imaging system. The proposed framework is evaluated based on broadly accepted performance metrics to accurately measure human disability detection in images with complex interfering objects where various visual elements are partially blocking or overlapping the person of interest, which makes it challenging for the deep learning models to determine relevant human disability features. The performance of the proposed approach is evaluated by implementing the current state-of-the-art object detection models, RetinaNet, Single Shot MultiBox Detector (SSD), Faster Region Convolutional Neural Network (FR-CNN), YOLOv11, and EfficientNet. A robust security technique is developed to verify the privacy, security, and integrity of human disabilities in medical imaging systems. The experimental results demonstrated that the proposed framework enables human multi-disabilities detection accuracy exceeding 97% and proves potential image transmission in secure medical imaging systems.

Introduction

Recent progressions in image processing play a crucial role in identifying specific characteristics of human disabilities, allowing accurate recognition of individuals with disabilities in two-dimensional (2D) images. Precise image recognition can be achieved by several machine learning techniques, such as neural networks (Bharadiya, 2023; Hasan et al., 2024), which efficiently identify image features and address diverse challenges in computer vision. Various approaches are present for image classification using filtering techniques designed for object recognition according to a certain object key feature or activity (Menezes et al., 2023; Alexandrov et al., 2024; Yang et al., 2024). Object recognition is extensively employed in various systems, with cameras capturing object mobility in specific areas and computer control systems determining object identity (Chen et al., 2023). Object detection is essential for monitoring systems that help individuals with disabilities in their mobility and providing alerts in critical situations.

Face recognition methodologies have been developed based on feature extraction and recognition (Ochango, 2023; Subramanyam, Kumar & Singh, 2024) that improve the performance of object recognition. Addressing the ability to gather crucial details about the facial features (Santhosh & Rajashekararadhya, 2022). However, their application remains constrained by the composite nature of the human face, which is formed of small and variable components such as the eyes, nose, and mouth (Antonarakis et al., 2020). Traditional methods such as eigenfaces, hybrid descriptors, and principal component analysis are sensitive to variations in posture, illumination, and especially to non-standard or atypical facial structures, thereby limiting their applicability to individuals with disabilities.

Approaches employing graph-structured models, such as the weber and pentagonal-triangle pattern, attempt to reduce dimensionality, but this comes at the expense of losing critical fine-grained information (Wadhera & Agarwal, 2022).

Viola-Jones algorithm is used to detect human faces by computing facial feature vectors within a certain threshold. While this method is computationally efficient, but it is less capable of distinguishing abnormal or irregular faces, underscoring a need for more adaptable frameworks that preserve subtle facial cues (Rizqullah et al., 2021).

Self-organizing maps combined with convolutional neural networks have been proposed to improve feature extraction under limited data conditions (Almotiri, 2022; Qu et al., 2021). Nevertheless, the assignment of feature weights remains challenging, and the assumption of pixel neighborhood similarity is often invalid for faces with disabilities, leading to misclassification.

Research on visual impairment detection has leveraged deep learning architectures to classify images of individuals with and without mobility aids (Kumar & Jain, 2021); yet this framework fails to incorporate real-world variability such as occlusion by sunglasses or masks, differences in eye shapes, or the presence of guiding helpers, thereby restricting their robustness.

Some challenges are observed in Down syndrome recognition studies that are based on facial analogy (Martzoukou, Nousia & Marinis, 2020; Jin, Cruz & Gonçalves, 2020), geometric descriptors (Hendrix et al., 2021), and local binary patterns (Pooch, Alva & Becker, 2020; Bhosle & Kokare, 2020). These studies suffer from either computational complexity, dependence on frontal images, or narrow training datasets that exclude essential features such as ears, neck, or varied body postures.

Distance-based deep learning classifiers struggle the limitation of training exclusively on Down syndrome faces, considering datasets that include mixed body positions, thereby reducing their generalizability (Khan et al., 2022). This highlights the gap in developing holistic models capable of integrating multi-view and multimodal data for reliable syndrome detection.

Equally, cerebral palsy detection systems demonstrate promise through distance-robust mechanisms and hybrid detection models (Balgude et al., 2024; Paul et al., 2022), but their reliance on fixed neighborhood sizes reduces adaptability across scales, while the absence of standardized ground truth introduces bias and inconsistency. The reliance on disjoint datasets further requires normalization across detection categories, reflecting a need for comprehensive, scalable, and standardized datasets.

In the dwarfism detection domain, multimodal radiomics approaches that combine image and clinical features emulate medical diagnostic reasoning (Pritchard, 2020; Qiu et al., 2022) but are computationally intensive, rendering them impractical for real-time or resource-constrained settings.

Detection systems for prosthetic usage and activity recognition using depth cameras and support vector machine (SVM)-based classifiers demonstrate potential for intent recognition (Zhong et al., 2021), yet they often rely on simplified depth features and fail to extend their applicability to powered prosthetic limbs, limiting their real-world clinical relevance.

Securing medical images data by steganography and asymmetric encryption techniques contribute to privacy and security (Dutta & Saini, 2021; Chen & Ye, 2022) but constrained by trade-offs between data quality and quantity, high computational overhead, and the limited functionality of one-way hashing schemes that cannot support key recovery. This is an indication of existing research gap for establishing robust, real-time encryption and privacy-preserving frameworks tailored for large-scale medical imaging systems.

Specifically, there is still a vital need for creating trustworthy frameworks that can accommodate individuals with atypical features due to mental or physical restrictions. Current techniques mainly rely on regular spatial assumptions of features that conform to standard anatomical structures, but not mainly for individuals with disabilities, leading to less reliability. In addition, there is a critical lack of real-time, widely adopted, multi-class classification, and lightweight diagnostic support systems for immediate and scalable human disability detection, particularly under-resourced settings or non-specialist environments. Furthermore, current artificial intelligence approaches deployed on healthcare field are centralized processing and do not support privacy and security deployment, making these approaches untrusted for sensitive medical and legal applications.

Although traditional approaches have achieved significant progress through dimensionality reduction algorithms and feature extraction methods, however, these techniques often suffer from accurately addressing the disabilities of individuals with mental or physical disorders. In addition, these techniques expose lack of comprehensive datasets, multi-class image support, real-time latency, data privacy, and computationally efficient cost. Table 1 presents a comparative analysis of the current approaches that extract and secure human disability features.

| Study | Objective | Method(s) used | Dataset & characteristics | Strengths | Limitations | Opportunities/Relevance to this study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deep facial diagnosis via transfer learning | Detect facial distortions for diagnosis | Deep transfer learning from face recognition | Not clearly defined | Leverages pre-trained models | Misses key facial features for Down syndrome | Supports use of transfer learning adapted to specific medical conditions |

| Cerebral Palsy (CP) detection with voting technique | Classify CP patients by mobility aid (wheelchair, walking) | 2D image analysis + voting system | Image-based; each pixel’s coordinate examined | Spatial analysis with prediction support | Fixed-size testing areas affect accuracy | Supports dynamic, adaptable spatial models for variable disability presentations |

| Dwarfism CAD via multimodal pyradiomics | Identify dwarfism using imaging + clinical features | Radiomics + tensor enhancement + fusion model | Medical images multimodal, clinical data linked | Simulates physician workflow | High computational complexity | Motivates development of lightweight, clinically aware models for abnormal body proportions |

| Depth camera for prosthesis activity recognition | Predict activity intent for lower-limb prosthetics | Depth imaging + SVM | Depth photos in multiple modes | Activity-aware classification | Limited to prosthetics; facial data not analyzed | Encourages exploration of depth imagery in facial recognition under occlusion |

| Asymmetric image encryption with SHA-3 | Secure medical image transmission | Hashing + RSA cryptosystem + compressive sensing | Not dataset-based | Strong encryption protocols | Irreversible hash function limits decryption | Highlights need for privacy-preserving medical imaging in diagnostic systems |

This comparison underlines a critical breach in the field of human disabilities and arises the need for comprehensive, adaptive, and clinically sensitive object detection models that can adjust inconsistency beyond the typical detection models’ structure.

Therefore, the proposed approach bridges the gap between academic research and the real-world needs of human disabilities screening, offering a novel solution that addresses technical, clinical, ethical, and practical needs simultaneously. This study is driven by the increasing need to enhance human disabilities recognition systems, particularly for individuals with mental and physical disorders. In addition, the objectives of this research are aligned with clinical regulatory compliance, individuals’ data privacy, and real-time latency.

The dominance of this study appears in its quest for specialized detection techniques that identify, classify, and secure human disabilities in 2D images. While current deep learning models generate potential results in standard environments, they often show shortage in critical cases involving individuals with multi-disabilities where the risks for accurate critical medical diagnostics are particularly extreme. Hence, the proposed approach aims to bridge this gap by incorporating atypical biometric features into training datasets, developing robust, bias-aware image processing framework, and integrating security framework that ensuring data privacy, preserving data integrity and avoiding illegal access and breaches, and adopting in real-world applications.

In this research, the integration of security measures into the human disability detection model operates on sensitive visual data containing private health information, such as facial features and physical impairments, which must be protected from unauthorized access and tampering. Therefore, the proposed framework incorporates a security system with multiple layers that combines advanced encryption standard (AES)-256 encryption, Secure Hash Algorithm (SHA)-based hashing, and integrity verification, ensuring the image confidentiality and authenticity are maintained throughout the image’s detection and transmission. This integration places the proposed framework as a timely and relevant contribution to the fields of medical imaging and assistive technologies, aligning with both the technical and ethical imperatives of contemporary healthcare delivery.

The collected images in this study are labelled, and the human disabilities are identified by the current state-of-the-art deep learning object detection models (Chen et al., 2023) namely, Single Shot MultiBox Detector (SSD) (Kumar & Srivastava, 2020), Faster Region Convolutional Neural Network (FR-CNN) (Li, 2021), YOLOv11 (Zhang et al., 2025), EfficientNet (Koonce, 2021), and RetinaNet (Alhasanat et al., 2021). The human disabilities features are extracted based on the models’ architectural components, Backbone network (Elharrouss et al., 2022), Feature Pyramid Network (Deng et al., 2021), Anchor Boxes (Shen et al., 2021), Non-Maximum Suppression (Ridnik et al., 2023), Bounding Box Regression (Zhao & Song, 2024), Multi-Scale Features (Wang et al., 2024), Region Proposal Network (Du & Liang, 2024), and Cross Stage Partial with kernel size 2 (C3k2) block (Khanam & Hussain, 2024). This framework resolves the challenges associated with identifying disabled people during their daily activities and interactions in reasonable time to provide them the necessary support specially in emergency cases. The main contributions of this research are:

Efficiently detect and support features’ extraction of human disabilities in 2D images.

Effectively handling rare and imbalanced human disability classes and ability to distinguish them in interfering image compositions.

Adaptability to identify new disabilities with minimal retraining and scalability across healthcare environments.

Securely processing and transmitting sensitive medical images and reduced manual workload for healthcare professionals.

The remainder of this article is outlined as follows; ‘Materials and Methods’ introduces the proposed framework methods and materials. ‘Experimental Results’ provides details of the experimental analyses conducted to evaluate the capability of the object detection models in identifying human disabilities. ‘Discussion’ presents the discussion of the proposed results. The conclusions and future work are drawn in ‘Conclusions’.

Materials and Methods

In this study, a framework is proposed to build, validate and evaluate several deep learning object detection models and show its effectiveness in achieving high accuracy of detecting single and multiple human disabilities in secure medical imaging systems. In addition, a security technique is proposed to ensure the privacy and confidentiality of transferred images in large public systems.

Human disabilities dataset

This study consists of 3,877 human disability 2D images named HD-Set collected originally from publicly available and free loyalty sources that provide free-to-use images for public domain. Despite their benefits for research and prototyping, public datasets come with inherent biases and ethical restrictions that can limit detection models’ performance and ethical integrity. One main issue is dataset imbalance, where certain disabilities are rare, overlapping, or completely missing, leading models to favor more common disabilities and perform poorly on less frequent ones. Additionally, the lack of demographic diversity, particularly in gender, age, and ethnicity, results in biased performance and reduced accuracy for diminished groups, raising concerns about fairness and inclusivity. Ethical problems also arise when images are sourced from the internet or social media without clear consent, potentially violating privacy rights and research standards. Furthermore, many datasets are collected in specific settings and lack the involvement of real-world environments, such as differed lighting, background noise, or obstruction, which limit the model’s ability to recognize in real-life applications. Moreover, there is a risk of stereotyping due to visual labeling bias, where features are inferred from appearance only, boosting harmful relationships between physical characteristics and specific disorders without medical validation. Addressing these shortcomings requires careful dataset auditing, bias mitigation strategies, and diverse ethically sourced data to ensure fairness of individuals with disabilities.

Therefore, the Deanship of Scientific Research and the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at German Jordanian University (GJU) reviewed and approved the proposed study protocol (Approval Numbers 14/1/53/336–11/9/2022 and IRB/GIU#02/2022) and confirmed that the collected images in the Disabilities-Dataset (HD-Set) are from royalty-free datasets, specifically, All-free-download https://all-free-download.com/pages/licence.html, Unsplash https://unsplash.com/s/photos/person-images-free-download?license=free, Dreamstime https://www.dreamstime.com/free-photos, Shutterstock https://www.shutterstock.com/data-licensing, Pexels https://www.pexels.com/license/, Aylward http://www.aylward.org/notes/open-access-medical-image-repositories, Google Storage https://support.google.com/photos/thread/26633759/clarification-of-google-terms-for-google-photos-user-content?hl=en, Kaggle https://www.kaggle.com/terms, Istockphoto https://www.istockphoto.com/help/licenses, Pixabay https://pixabay.com/service/license-summary/, and Adobe https://stock.adobe.com/jo/search/free?k=disability+physical&search_type=recentsearch. In addition, the Scientific Research Deanship Council at GJU settles that the images in the Disabilities-Dataset (HD-Set) are copyright-free to ensure obedience with data sharing ethics and used only for research purposes. The code and images dataset used in this study are publicly available at our GitHub repository Disabilities-Dataset (DOI 10.5281/zenodo.17041230). The repository includes human disability images dataset HD-Set that consists of 3,877 images across seven classes namely, blind persons with different helping tools, down syndrome individuals of different ages, dwarf people of various ages, cerebral palsy persons, individuals with prosthetic arms, persons with prosthetic legs, and normal people doing different activities. In addition, the repository includes the following files: (train.py, test.py) for training/inference scripts, (data_prepare.py) for data preparation utilities, cross-validation splits and resizing, (crop_image.py) for helping tools, and (requirements.txt) for recreating the software environment. The HD-Set images are scanned by a professional medical specialist at the University of Jordan Hospital who checked the ground truth of the collected images.

The requirements.txt file is provided to recreate the software environment. The dataset is released under CC BY 4.0; scripts cover common detectors (RetinaNet via Detectron2, FR-CNN and SSD via TensorFlow, and YOLOv11 via Ultralytics), enabling researchers to replicate and extend our experiments by employing a structured plan that spans data, model design, integration, and compliance through the following actionable steps:

Reproduce splits & preprocessing: run data_prepare.py to generate 10-fold cross-validation (CV) splits and standardized image resizing.

Train baseline detectors: use train.py to train RetinaNet/FR-CNN/SSD/YOLOv11 with the provided folds; test.py performs single-image inference for quick validation.

Swap/extend architectures: plug in alternative backbones or add CenterNet/EfficientNet detection heads by following the existing model selection pattern in train.py.

Recreate conditions: install dependencies via pip install -r requirements.txt; fix random seeds for reproducibility as outlined in our implementation methods.

Cite & reuse: cite the repository’s HD-Set entry when reusing data; license terms (CC BY 4.0) permit modification and redistribution with proper attribution.

Preprocessing human disabilities datasets

Several image preprocessing techniques were applied on the collected HD-Set prior to initiating the training procedure, which entailed resizing while preserving the inherent aspect ratio. Despite its high accuracy rate (>90%) of clarity, the original images were not clear enough and not ready for processing by the deep learning object detection models, therefore, image augmentation (Xu et al., 2023) including shearing, zooming, scaling, and normalizing were employed and described as follows:

Shearing: there is a shear intensity to the image (Zhang, Sun & Gao, 2023) where the angle of shear is measured in degrees, and the shear direction is counterclockwise. Shearing distorts the image by slanting it along a specific axis.

Zooming and flipping: a zooming effect is applied, which includes flipping the image horizontally and vertically. Furthermore, random rotations within a specified range are applied using the transformations and random rotation functions (Sunil & Narsimha, 2024). This step introduces variations in the image’s orientation and scale.

Scaling: scaling is performed to adjust the size of the image (Avidan & Shamir, 2023). The scaling process involves multiplying the image by a scaling constant to generate images of different sizes.

Normalization: the original images have red, green, blue (RGB) coefficients ranging from 0 to 255. To simplify processing and analysis due to hardware limitations, these values are normalized to a range of 0 to 1 (Pei et al., 2023). This is achieved by dividing the RGB values by 255.

During the testing phase, the trained model was supplied with images that had undergone resizing while retaining their original aspect ratios. However, some augmentation techniques may provide indirect support for involving images in the dataset, such as image duplication, and don’t offer data privacy and security, especially when transferring sensitive image files. Therefore, a security technique is proposed to verify that no distortion has occurred before supplying images into deep learning object detection classifiers and described in the following section.

Securing human disability images

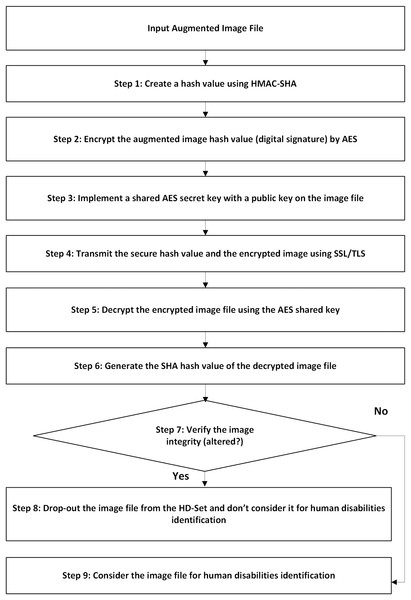

Individuals with disabilities are often part of protected populations and require enhanced ethical handling. Unauthorized exposure could lead to social stigma, discrimination, or loss of privacy. Therefore, a structured, multi-stage security framework is developed to preserve the privacy, confidentiality, and integrity of human disability images while transferring within public medical imaging environments. The proposed framework initially employs image augmentation (e.g., shearing, zooming, normalization) to remove irrelevant data and format images for processing, ensuring compatibility with subsequent security operations. Then, the framework employs a multi-layered security technique that integrates the advanced encryption standard algorithm (AES-256) for robust data encryption during transmission with the secure hash algorithm (SHA-3) that generates unique digital fingerprints to defend against unauthorized changes. Piping these algorithms together establishes a consistent security architecture that defends images’ data violations, prevents the risk of interfering, and maintains privacy aligned with medical data protection standards. The proposed security framework is presented in Fig. 1 and described as follows:

-

(1)

Image encryption: after image augmentation, the training and testing HD-Sets are encrypted using AES-256 to guarantee that even if image data is interrupted, it cannot be assessed without the decryption key and ensures the image data is transformed into a non-readable format, preventing unauthorized access during transmission.

-

(2)

Hash value generation: SHA-3 hashing algorithm is employed to produce a unique digital hash value for the encrypted image. The hash value serves as a fingerprint of the image, enabling discovery of any modification or interfering.

-

(3)

Image transmission: the encrypted image along with its generated hash value is transmitted over the public medical imaging network. The image encryption guarantees confidentiality, while the hash value provides a reference for subsequent verifications.

-

(4)

Image decryption and validation: the received image is decrypted by AES-256 technique, returning it to its original and readable form for authorized use while its hash value is recalculated and compared with the original transmitted hash value. Matching values prove that the image has not been altered during transfer, confirming data integrity.

-

(5)

Secure storage and access control: verified images are stored in the testing and training HD-Sets with controlled access privileges, ensuring ongoing protection of disability individuals’ data and aligned with medical data protection regulations.

Figure 1: The proposed framework security architecture.

The framework employs a multi-layered security technique that integrates the advanced encryption standard algorithm (AES-256) for robust data encryption during transmission with the secure hash algorithm (SHA-3) that generates unique digital fingerprints to defend against unauthorized changes.The proposed security framework is employed before identifying human disability images by deep learning models. Specifically, image encryption is done before training and testing phases. The overhead of this security framework on the model’s performance is measured as the sum of average encryption/decryption time (~0.04643 s/image), hashing time (~0.000085 s/image), and the best model’s inference time (RetinaNet, ~0.05326 s/image). Hence, the total processing time of the proposed approach is (~0.09977 s/image). Since the security encryption and hashing tasks are completely decoupled from the model’s training and inference computations, they do not interfere with model’s architecture, features extraction, and prediction, so they do not affect the model’s performance. In addition, the images are fully decrypted and validated before entering the training model, ensuring that the learning and detection accuracy remain unaffected.

In essence, the proposed security technique ensures that human disability images remain confidential, secured throughout transmission, and protected from intervention, altering, or unauthorized disclosure.

Selection of deep learning object detection models

The state-of-the-art object detection models namely, RetinaNet, SSD, FR-CNN, YOLOv11, and EfficientNet were selected, implemented and evaluated to determine the best model that generates the highest evidence results of identifying the human disabilities in 2D images. The selection criteria of object detection models are based on the application requirements such as hardware resources available, processing time, and application complexity level. Therefore, we select object detection models that depend on computational proficiency, speed, and accuracy. In addition, we include different object detection classification architectures, one-stage detector (RetinaNet, SSD, and YOLO11) that promptly expect the object classes and bounding boxes in a one-pass, two-stage detector (FR-CNN) that generate possible object locations in the first-stage and then refine the generated locations’ bound boxes in the second-stage, and a backbone architecture (EfficientNet) that is used as a feature extractor in both one-stage and two-stage detectors.

Specifically, RetinaNet model is used to detect small or uncommon objects in unbalanced datasets. The SSD model is exploited for real-time object detection that accurately settles speed and accuracy. FR-CNN model is utilized for complicated classifications where accuracy is the main requirement. The YOLO11 model is an exceptionally fast and accurate real-time object detector. The EfficientNet model is selected for its computation competency and as impressive backbone for one-phase and two-phase detectors.

Performance metrics

Several performance metrics are employed to assess the deep learning model’s detection performance. The performance metrics that represent different classification qualities including accuracy, F1-score, precision, specificity, sensitivity (recall), Matthew’s correlation coefficient (MCC) (Foody, 2023), error rate, and false positive rate (Long, 2021).

Each evaluation metric plays a critical and distinct role in assessing the performance of the human disability detection models, mainly because the models are employed in applications that involve real-world clinical decisions and potential missed diagnoses. The performance metrics are computed based on the following hallmark measures that are useful in quantifying the efficiency of the deep learning model, P: number of real positive occurrences, N: number of real negative occurrences, True Positive (TP): the actual result obtained positive but the detection model forecasted positive, True Negative (TN): the real outcome was negative but the detection model forecasted negative, False Positive (FP): the actual result found negative but the detection model forecasted positive, False Negative (FN): the real result was positive but the detection model forecasted negative. Each performance metric offers a distinct viewpoint on the effectiveness of the deep learning detection model. For instance, Accuracy offers a broad snapshot of how often the model is correct and most useful when classes are balanced. Precision is important for reducing false alarms to avoid unnecessary further testing or referrals. Specificity measures how well the model avoids recognizing healthy individuals as disabled. Sensitivity (recall) indicates the model trustworthiness for early object identification, which is vital for systems interference. F1-score balances how many positives are found with how many positive predictions were correct. MCC gives more reliable evaluation when the dataset is imbalanced. Error Rate measures the overall model error that helps in model refinement. False Positive Rate is useful for quantifying how often healthy individuals are incorrectly identified. For each of the following metrics, accuracy, precision, specificity, sensitivity (recall), F1-score, and MCC, the higher the performance value, the better detection. On the other hand, the lower the Error Rate and False Positive Rate values are, the better detection. The performance assessment metrics computations are presented in the following equations:

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4)

(5)

(6)

(7)

(8) These assessment metrics offer supplementary scales on the object detection models’ performance. Using a combination of the performance metrics gives more thoughtfulness, particularly when the costs of different types of application faults are varied.

Human disabilities object detection framework

To identify human disability class in each image, the following initial procedures are applied on each image of the HD-Set: resizing the input images and entering the ground truth labels of all human disability images for constructing the framework training and testing datasets, followed by splitting the resized images into training and testing datasets and applying image augmentation techniques on the training set to generate the augmented training set, then securing the augmented training and testing datasets using the proposed security technique to produce the secured and augmented training dataset and secured testing datasets.

The training phase of human disabilities object detection model includes training cycles, loss functions, and optimization strategies that are designed to optimize the model’s performance across various real-world applications. In this phase, the model was trained for hundred epochs as a baseline and early stopping was applied when ten successive epochs showed no improvement in validation loss. Training continued for up to ten epochs after the last improvement before stopping to prevent overfitting and minimizing wasted computation and to ensure model robustness across variations in disability type, camera angles, and lighting conditions. This learning strategy allows the model to maintain the balance between training accuracy and the prediction of the hidden images. Furthermore, the training phase utilizes multi-part loss functions, specifically Localization Loss function that used by RetinaNet and SSD models for bounding box regression to predict accurate coordinates of the disability object in varying spatial conditions, Cross-Entropy Loss function that is used by FR-CNN and EfficientNet to penalize incorrect multi-class predictions, and Confidence Loss function that is used by YOLOv11 to determine whether a predicted box contains a relevant disability feature. Additionally, Adam optimizer was used due to its robustness in smoothing out noisy gradient updates using an exponentially weighted moving average of past gradients, preventing unnecessary fluctuations.

Furthermore, the entire training dataset was split using 10-fold cross-validation, 90% for training and 10% for validation in each fold to ensure model robustness across demographic diversity and imaging variations, and the model’s performance was averaged over 10 folds to get stable and generalizable performance evaluations. The model performance was evaluated per fold using the validation loss, F1-score, and average precision at different Intersection over Union thresholds (0.5 and 0.75) to guide the early stopping and model check points.

The training phase reflects a well-structured and clinically aware design, with mechanisms such as early stopping and multi-fold validation to reduce overfitting and ensure generalizability. By combining multiple loss functions fitted to detection and classification, the model is well-optimized for identifying different mental and physical disabilities under real-world imaging environments.

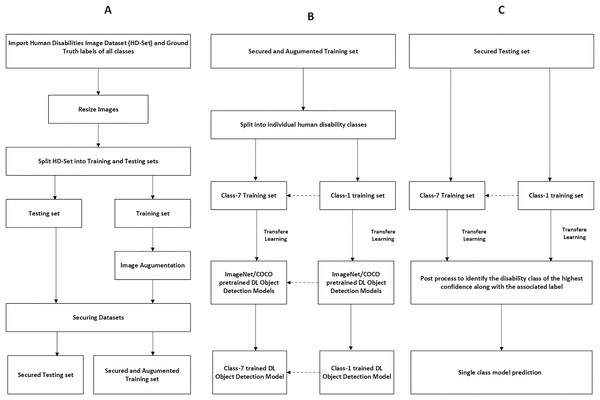

Single-class object detection model

The proposed single-class object detection model is illustrated by the following processes that are applied after the initial procedures to identify human disability in each image: the secured and augmented training set is split into individual training classes, each class dataset represents one human disability namely, blindness, down syndrome, dwarfism, cerebral palsy, prosthetic arms, and prosthetic legs. Then, the transfer-learning technique (Kim et al., 2022) and the pretrained deep learning object detection models, ImageNet (Shankar et al., 2020) and Microsoft Common Objects in Context (MS-COCO) (Bideaux et al., 2024), are applied on the secured and augmented single-class training datasets to build the trained single-class object detection model for each disability. Finally, the object detection single-class training model is applied on the secured single-class testing set, and the result of the disability identification is determined based on the highest confidence value along with associated label. Figures 2A–2C illustrates the processes of identifying human disabilities by using a single-class object detection model.

Figure 2: Preprocessing and securing input images for single-class object detection model.

Figure (A–C) illustrates the processes of identifying human disabilities by using a single-class object detection model.Multi-class object detection model

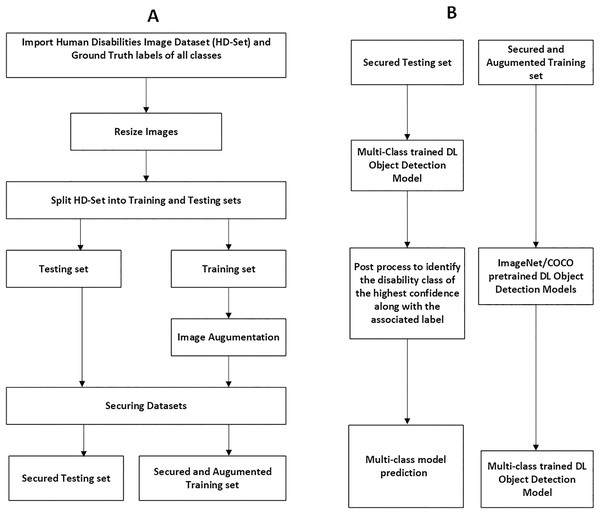

The proposed multi-class object detection model is explained by the following processes that identify human disability in each image: the pretrained deep learning object detection models, ImageNet and MS-COCO, are applied on the secured and augmented multi-class training set to build the trained multi-class object detection model. Then, the trained multi-class object detection model is applied on the secured multi-class testing dataset. Where the multi-class training dataset is the secured and augmented training dataset of all human disabilities and the multi-class testing dataset is the secured testing dataset of all human disabilities. The results of disability identification by the trained multi-class object detection model are determined based on the highest confidence value along with associated label. Figures 3A, 3B describes the processes of recognizing human disabilities by using multi-class object detection models. The steps of identifying human disabilities features by the proposed framework single-class and multi-class object detection models are summarized in Algorithm 1.

Figure 3: Preprocessing and securing input images for multi-class object detection model.

Figure (A–B) describes the processes of recognizing human disabilities by using multi-class object detection models.| Input: Human disability image file |

| Output: Human disability Class |

| Initialization: |

| Step 1: Resize the input image and enter the ground truth label of HD-Set images. |

| Step 2: Split the resized images into training and testing datasets. |

| Step 3: Apply shearing, zooming, scaling, and normalization augmentation techniques on the training set. |

| Step 4: Secure the augmented training and testing image sets using the proposed security technique. |

| Processing: |

| If single-class object detection model is selected, then perform steps 5–8, else if multi-class object detection model is selected, then perform steps 9–12. |

| Begin |

| Step 5: Split the secured and augmented training set into individual human disability training classes. |

| Step 6: Apply transfer learning technique and the ImageNet and MS-COCO pretrained deep learning models on each disability training dataset to build the trained disability single-class object detection model. |

| Step 7: Apply the object detection single-class training model on the secured testing set. |

| Step 8: The single-class training model determines if the human disability in the image belongs to a certain class, based on the highest confidence value along with associated label. |

| End. |

| Multi-class object detection model |

| Begin |

| Step 9: Use the secured and augmented training set of all human disabilities for multi-class training set. |

| Step 10: Apply transfer learning technique and the ImageNet and MS-COCO pretrained deep learning models on the secured and augmented multi-class training set to build the trained multi-class object detection model. |

| Step 11: Apply the trained multi-class object detection model on the secured multi-class testing set. |

| Step 12: The multi-class training model determines the human disability in the image belongs to which disability class, based on the highest confidence value along with associated label. |

| End. |

Evaluation method

Deep learning object detection models were explicitly evaluated by applying the trained single-class/multi-class deep learning object detection models that are generated by Algorithm 1 on the secured testing datasets. The evaluation results determined the human disability class based on the highest confidence value along with the associated ground truth label. The outcomes of the single-class and the multi-class object detection models were recorded in tables, compared and transformed into graphical representation to show clear performance evidence.

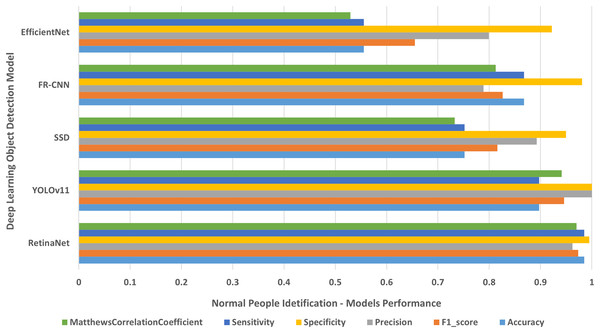

Single-class models evaluation

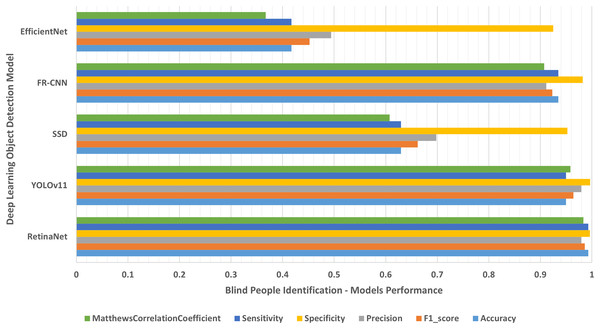

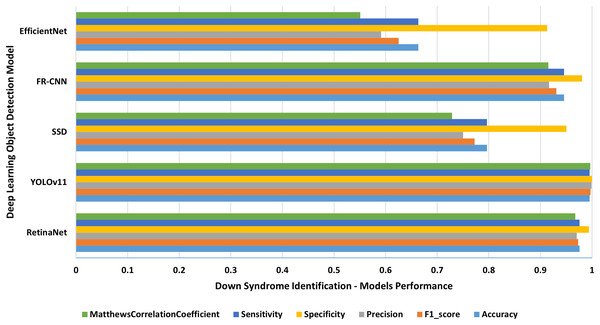

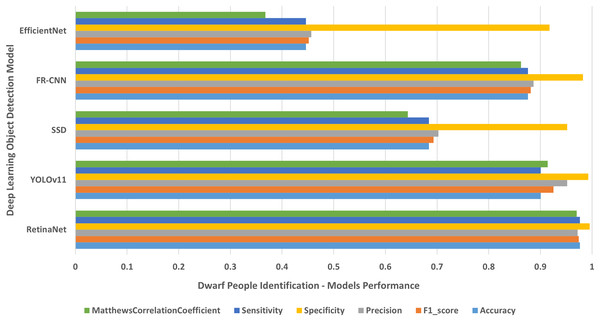

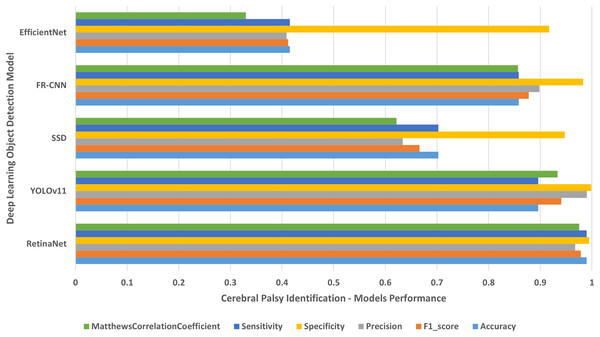

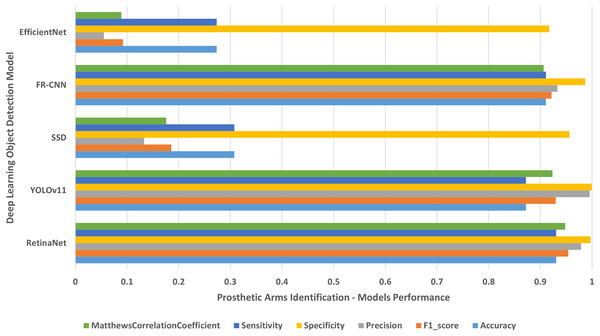

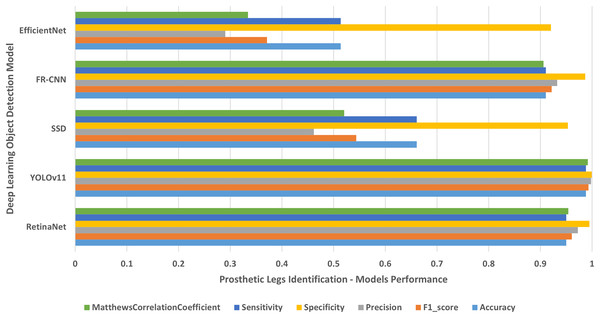

Each single-class object detection model was applied separately on each human disability testing dataset. The experiment results were detailed in Table 2 and presented in Figs. 4–10 as follows: Fig. 4: normal people doing different activities, Fig. 5: blind people with dissimilar guidance, Fig. 6: down syndrome people at different ages, Fig. 7: dwarf people at various ages, Fig. 8: cerebral palsy people on wheelchair, Fig. 9: people with left/right prosthetic arms, and Fig. 10: people with left/right prosthetic legs. The experimental results confirm that the RetinaNet object detection model achieved higher performance (in terms of accuracy, F1-score, sensitivity/Recall, and MCC) than the other four models YOLOv11, SSD, FR-CNN, and EfficientNet.

| Deep learning model | Accuracy | F1-score | Precision | Specificity | Sensitivity | MCC | Error rate | FPR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RetinaNet | 0.97156 ± 0.02293 | 0.97156 ± 0.01071 | 0.97185 ± 0.00600 | 0.99532 ± 0.00107 | 0.97156 ± 0.02293 | 0.96698 ± 0.01211 | 0.02843 ± 0.02293 | 0.00467 ± 0.00107 |

| YOLOv11 | 0.92855 ± 0.04905 | 0.9566 ± 0.02910 | 0.98769 ± 0.01742 | 0.99805 ± 0.002725 | 0.92855 ± 0.049051 | 0.95122 ± 0.03245 | 0.07147 ± 0.04905 | 0.001948 ± 0.00272 |

| SSD | 0.64754 ± 0.15986 | 0.61996 ± 0.21037 | 0.61029 ± 0.24700 | 0.95160 ± 0.00284 | 0.64754 ± 0.15986 | 0.57577 ± 0.19090 | 0.35245 ± 0.15986 | 0.04839 ± 0.00284 |

| FR-CNN | 0.90058 ± 0.03397 | 0.89753 ± 0.03794 | 0.89533 ± 0.04985 | 0.98323 ± 0.00260 | 0.90058 ± 0.03397 | 0.88113 ± 0.03817 | 0.09941 ± 0.03397 | 0.01676 ± 0.00260 |

| EfficientNet | 0.54316 ± 0.21113 | 0.50426 ± 0.26197 | 0.50185 ± 0.29408 | 0.92710 ± 0.02436 | 0.54316 ± 0.21113 | 0.44410 ± 0.25509 | 0.45683 ± 0.21113 | 0.07289 ± 0.02436 |

Figure 4: Normal people identification.

The results of identifying normal people doing different activities.Figure 5: Blind people with dissimilar guidance.

The results of identifying blind people with dissimilar guidance.Figure 6: Down syndrome people of different ages.

The results of identifying down syndrome people of different ages.Figure 7: Dwarf people of various ages.

The results of identifying dwarf people of different ages.Figure 8: Cerebral palsy people on wheelchair.

The results of identifying cerebral palsy people on wheelchair.Figure 9: People with left/right prosthetic arms.

The results of identifying people with left/right prosthetic arms.Figure 10: People with left/right prosthetic legs.

The results of identifying people with left/right prosthetic legs.Multi-class models evaluation

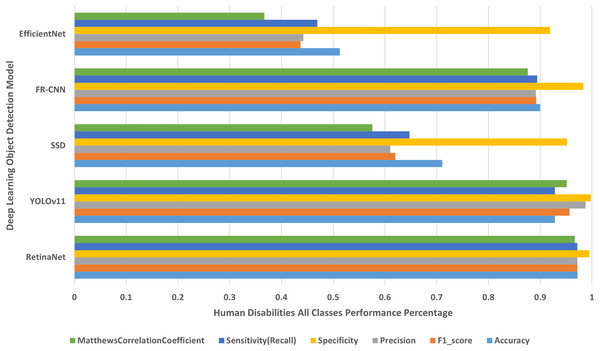

Each object detection model was applied on all human disabilities testing datasets together. The experimental results were displayed in Table 3 and presented in Fig. 11. The experimental results disclose that the RetinaNet multi-class object detection model achieved higher performance than the other four models in terms of accuracy, F1-score, sensitivity/recall, and MCC. The YOLOv11 model generates the next higher performance values, followed by the FR-CNN model, then SSD model, and finally the EfficientNet model that produces the lowest performance results because of the conflicts with overlapping objects. Furthermore, the results presented in Table 3 confirm that RetianNet model produced the lowest error rate followed by YOLOv11, FR-CNN, SSD, and EfficientNet respectively. However, YOLOv11 accomplishes the least false positive rate results followed by RetinaNet, FR-CNN, SSD, and EfficientNet consequently.

| Deep learning model | Accuracy | F1-score | Precision | Specificity | Sensitivity | MCC | Error rate | FPR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RetinaNet | 0.97198 | 0.97156 | 0.97185 | 0.99532 | 0.97156 | 0.96698 | 0.02801 | 0.00467 |

| YOLOv11 | 0.92855 | 0.95667 | 0.98769 | 0.998051 | 0.928552 | 0.951223 | 0.07144 | 0.00194 |

| SSD | 0.71062 | 0.61996 | 0.61029 | 0.95160 | 0.64754 | 0.57577 | 0.28937 | 0.04839 |

| FR-CNN | 0.89978 | 0.89229 | 0.89141 | 0.98330 | 0.89411 | 0.87588 | 0.10021 | 0.01669 |

| EfficientNet | 0.51279 | 0.43705 | 0.44224 | 0.91892 | 0.46923 | 0.36690 | 0.48720 | 0.08107 |

Figure 11: Human disabilities all classes performance percentage.

The deep learning models results for identifying human disabilities of all classes.Inference time and efficiency evaluation

The framework inference time, security time, and efficiency evaluation are detailed as follows:

The inference time (Inference_Time) of object detection is computed in Eq. (9): (9) where (P_time) is the image prediction time, and n represents the number of images in the HD-Set.

The average security time (Security_time) required for each image in HD-Set is computed in Eq. (10): (10)

The average time for encryption, decryption, and transmission (EDT_time) is computed in Eq. (11): (11) where the number of HD-Set images is 3,877 of a total size 1 GB. The AES_time required for applying the AES-256 algorithm on the dataset is equal to 3 min (180 s), and the average EDT_time (~0.046427 s/image).

The average hash time (Hash_time) of the HD-Set using high-end GPU with SHA hashing algorithm speed SHA_speed of 3 GB/s is computed in Eq. (12): (12) The average hash_time required is ~0.333333 s for the HD-Set of 1 GB, this is equivalent to (~0.000085 s/image). Hence, the average security time is (~ 0.046512 s/image).

The average Processing_time required for each image in HD-Set is computed in Eq. (13): (13)

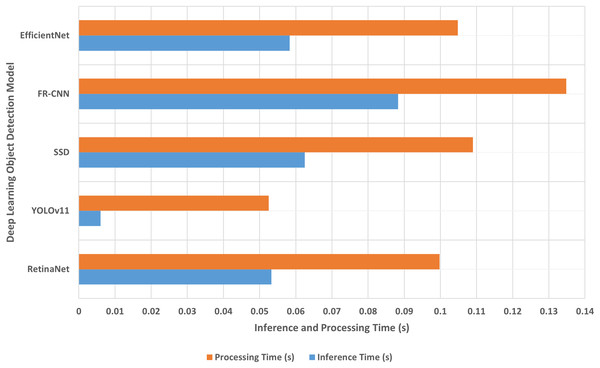

The average inference and processing times of the multi-class object detection models are recorded in Table 4 and presented in Fig. 12.

| Multi-class model | Inference time (s) | Security time (s) | Processing time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RetinaNet | 0.053261 | 0.046512 | 0.099773 |

| YOLOv11 | 0.006013 | 0.046512 | 0.052525 |

| SSD | 0.062480 | 0.046512 | 0.108992 |

| FR-CNN | 0.088304 | 0.046512 | 0.134816 |

| EfficientNet | 0.058325 | 0.046512 | 0.104837 |

Figure 12: The inference and processing times.

The proposed approach inference and processing times.Experimental results

Various experiments were conducted on the HD-Set to assess the performance of the selected object detection models in detecting human disabilities in 2D images. The experiments were executed on a workstation with 2x Intel Xeon 20-cores CPU, Nvidia Tesla V100 GPU, and 128 GB RAM. Each experiment was performed ten folds on each single-class model, and another ten folds on each multi-class model. The training to testing ratio was set to 90:10.

The proposed approach evaluates five state-of-the-art object recognition detection models, RetinaNet, YOLOv11, SSD, Faster R-CNN, and EfficientNet. Each model is implemented for both single-class and multi-class human disability detection. The key parameters that distinguish each deep learning model are summarized in Table 5 and described as follows: Input Size: resolution (height × width in pixels) of input images that the model accepts and defines for the neural network. This parameter influences both model’s performance and accuracy. Learning Rate (default start): initial learning rate used for training, some models start with a fixed rate (e.g., 5e−4), others gradually decrease from a higher initial value. Batch Size (default): number of training cases used in one forward/backward pass. For instance, a batch size of 64 means the model processes 64 images at once. However, batch size affects memory usage and training stability. Epochs: number of training steps. It indicates how long the model is trained as if it passes the entire dataset. Optimizer (default): the optimization algorithm used to minimize the loss during training such as Adam/AdamW are adaptive optimizers with/without weight decay, Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) which is often used with momentum and weight decay, and root mean square propagation (RMSProp) that is adaptive learning rate, often used for mobile or lightweight models. Loss functions are used to compute the error between predictions and ground truth that guides model’s learning, such as focal loss function that handles class disparity by concentrating on hard instances, smooth L1 regression loss for bounding box coordinates, Multibox function which is a combination of classification and bound box regression, Region Proposal Network (RPN) loss function used for region proposal network, distribution focal loss function that attains class imbalance in datasets, binary cross-entropy function that achieves class imbalance and used for multi-class problems, and the complementary classification (cls) and bounding box (bbox) loss functions that used to train model by quantifying the error in predicting the correct class label or a region of interest.

| Model | Image input size (pixels) | Learning rate (default start) | Batch size (default) | Epochs | Optimizer (default) | Loss function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RetinaNet | 640 × 640 | 1e−4 (cosine decay) | 64 | 25–50 epochs equiv. | SGD (momentum 0.9, wd 1e−4) | Focal loss (cls) + Smooth L1 (bbox) |

| YOLOv11 | 640 × 640 | 1e−3 → cosine decay | 16 | 100 | AdamW | Composite loss (CIoU/DFL + BCE cls/obj) |

| Faster R-CNN | 640 × 640 | 0.08 → cosine decay | 64 | ~25 epochs equiv. | SGD (momentum 0.9, wd 4e−5) | RPN loss + classification + Smooth L1 bbox |

| SSD | 640 × 640 | 0.04 (cosine decay) | 64 | ~25 epochs equiv. | SGD (momentum 0.9, wd 4e−5) | MultiBox (cls + Smooth L1 bbox) |

| EfficientDet | 512 × 512 | 0.08 → cosine decay | 64 | ~300 epochs equiv. | RMSProp (momentum 0.9, wd 4e−5) | Focal loss (cls) + Smooth L1 (bbox) |

The programming language employed in the experimental development is Python 3.10. In addition, the deep learning libraries, PyTorch 2.0 and torchvision 0.15 are employed for experimental development of RetinaNet, YOLOv11, Faster R-CNN, and SSD models, while TensorFlow 2.11 and Keras are employed for the EfficientNet model. Furthermore, PyTorch frameworks are employed for experimental development of RetinaNet, YOLOv11, Faster R-CNN, SSD, and EfficientNet models, while TensorFlow Object Detection API is employed for RetinaNet, Faster R-CNN, and SSD models.

The results shown in Table 2 and presented in Figs. 4–10 confirm that the RetinaNet deep learning model outperforms YOLOv11, SSD, FR-CNN, and EfficientNet models in single-class human disabilities detection. In addition, the experimental results depicted in Table 3 and presented in Fig. 11 disclose the superiority of the RetinaNet model over the other models in comparison in multi-class human disabilities detection. These results confirm the ability of the proposed framework training models to enhance human disability detection in 2D images.

The proposed approach offers a detailed, evidence-based analysis of the experimental results. The description of deep learning models’ architecture, frameworks, libraries, pretrained datasets, and their influences on human disability detection are illustrated in the following subsections.

Deep learning detectors selection

This study clearly demonstrates the criteria of selecting the deep learning models, aligning with the research objectives and highlighting their practical advantages and potential real-world benefits. RetinaNet was selected for its strong capabilities in detecting small or uncommon objects, which is essential in the context of identifying various human disabilities. RetinaNet outperformed all other models in multi-class classification tasks, achieving the highest performance metrics, accuracy (97.19%), F1-score (97.15%), recall (97.15%), and MCC (96.69%). This superior performance is principally due to its architectural components such as the feature pyramid network (FPN), dense anchor generation, and focal loss. This model employs transfer learning using pre-trained weights from ImageNet and MS-COCO datasets, which significantly improved performance on the HD-Set disability dataset.

YOLOv11, while not achieving the top scores in accuracy, stood out for its extremely fast inference time (0.006 s per image) and creditable performance metrics: accuracy (92.85%), F1-score (95.66%), recall (92.85%), and MCC (95.12%). Its architecture is optimized for speed through a single-pass detection mechanism and lightweight detection heads. Although YOLOv11 excels in detecting larger objects, it is less sensitive to smaller features that are common in the HD-Set. Hence, it results in misidentification of objects particularly in images that consist of multi-disabilities. Despite this limitation, YOLOv11 remains a strong option for real-time systems where speed processing is critical.

Faster R-CNN also delivered solid outcomes with accuracy (89.97%), F1-score (89.22%), Recall (89.41%), and MCC (87.58%), though it had the slowest inference time (~0.088 s/image). Its two-stage detection mechanism, region proposal stage followed by classification and regression, offers high accuracy but comes with the cost of complexity and slower speed. For datasets like HD-Set, which include many small and unusual patterns, the generic region proposal strategy may not always perform well unless it is carefully fine-tuned. This model also requires a longer training schedule and more resources to optimize performance. While talented, Faster R-CNN is not as efficient as RetinaNet in detecting human disabilities due to its sensitivity to region proposal quality and extended training requirements.

The SSD model was designed for real-time object detection, relying on multiple anchor boxes of varying sizes to detect different objects. Although it operates at a moderate inference speed, SSD struggled significantly on the HD-Set, recording poor performance scores, accuracy (71.06%), F1-score (61.99%), recall (64.75%), and MCC (57.57%). Its main limitation comes from difficulties in detecting small objects and managing overlapping features, which are common in images depicting individuals with disabilities. SSD’s efficiency is highly dependent on accurate tuning of anchor scales to match image resolutions. Inadequate tuning led to many missed detections, resulting in decreasing overall performance.

EfficientNet is known for its parameter-efficient backbone architecture. However, it achieved the lowest performance measures, accuracy (51.27%), F1-score (43.70%), recall (46.92%), and MCC (36.69%). Its architecture was not well-suited for object detection tasks involving small-scale features without integrating more advanced components like feature pyramid networks or carefully selected anchor configurations. EfficientNet also generates high false positive rates, hence, leading to poor reliability in the context of human disability detection.

The study impact and application

The primary objective of the proposed research was to construct a resilient deep learning model proficient in precise detection of multiple disabilities in 2D medical images and securely handling and transmission of sensitive medical data. These images often include complex backgrounds, small distinguishing features, and suffer from class imbalances. The outcomes of the experiments showed that the proposed approach effectively meets these challenges. Notably, the high recall values indicate a lower risk of missed diagnoses, even in visually cluttered images. This model shows strong performance across both common and rare disability cases in adequate real-time detection speed (0.053 s/image) that makes it well-suited for emergency healthcare applications, while the combination of accuracy and secure image processing builds trust in automated diagnostic tools.

In addition, this study supports healthcare professionals by validating preliminary assessments or monitoring disable individuals over time and issues timely alerts in emergency case particularly in regions with shortage of specialists. In telemedicine scenarios, the model enables secure and private remote diagnostics. It can also support public health initiatives by automatically collecting data on disability cases, which can improve their planning and services.

Practical benefits of the study

Several advantages emerge from the proposed deep learning model. It improves diagnostic accuracy by minimizing the errors in identifying human disabilities and handles imbalanced datasets effectively, ensuring rare disabilities are not neglected. The model is adaptable and can be extended to detect new human disability types, such as auditory impairments, with minimal retraining. Additionally, it enhances operational efficiency by reducing manual image analysis time, allowing healthcare staff to focus more on medication care. Furthermore, the secured images produced from this study ensure compliance with medical data privacy regulations and the model’s scalability make it applicable across various healthcare environments, from large healthcare centers to small clinics with limited resources.

Therefore, the proposed approach effectively tackles the key challenges of accurately, securely, and efficiently identifying multiple human disabilities in 2D images. With its strong detection performance, ability to handle multiple human disabilities, and the potential to enhance disable individuals’ safety, it stands out as a dependable real-time detection tool that supports both in-person and remote medical services.

Discussion

While one-stage object detection models such as RetinaNet, SSD, and EfficientNet accommodate for efficiency by generating direct predictions without region of interest (ROI) pooling, two-stage object detection models such as FR-CNN, select accuracy over speed. Although YOLOv11 is a one-stage object detection model, it compromises between accuracy and speed that make it suitable for real-time systems that do not need very high accuracy. The RetinaNet model results are promising, however, future performance can be enhanced by using higher filtering approaches that accurately identify the human disability region in the image, especially in cases when people have multiple and complex disabilities.

Despite the reasonably large amount of time required to train and secure our framework models, the training and securing processes are performed offline. The average inference time shown in Table 4 and depicted in Fig. 12 confirms the superiority of YOLOv11 in identifying the input image class as the fastest object detection model, followed by RetinaNet, EfficientNet, SSD, and finally the two-stage FR-CNN model. This proves the speed priority of the YOLOv11 model over the accuracy.

The proposed framework offers high computational performance, efficient scalability, and strong potential deployment in real-world clinical environments. Nevertheless, it comes with slight concerns on misclassification of human disability that may cause delayed diagnosis or influence healthcare decisions. In addition, disability-related images are highly sensitive and have ethical and social concerns, integrating them with non-secured public clinical-grade audit trails, consent protocols, and at-home monitoring environments could violate human autonomy and breach disability person’s privacy. Therefore, real-world deployment demands deep attention to ethical, legal, and practical risks.

Consequently, the ultimate challenge of our research is to balance innovation with responsibility to ensure that the proposed prediction model offers a faster, secure, accurate, more flexible, and better-targeted solution than traditional commercial medical imaging models. Its latency (<0.1 s/image) enables real-time clinical diagnostics and makes it closer to point-of-care and even at-home monitoring situations that conventional medical models have not effectively addressed. In addition, the proposed model embeds privacy-preserving mechanisms that allow safely operating under strict healthcare regulations without rerouting data through external servers which is an issue for many commercial approaches. Moreover, it is open to fine-tuning and extension to other medical scenarios, making it highly relevant to human-function assessment beyond clinical scans. Also, it can be optimized for visible-light cameras in uncontrolled environments, waiting rooms, schools, or sidewalks, making it deployable on user’s hardware with lower cost and far more resourceful than the current widely adopted medical imaging solutions.

Its computational costs and scalability vary depending on the chosen architecture and the intended clinical deployment. The model cost is assessed on the time-based components, specifically training phase, inference phase, security overhead, and hardware requirements. The training phase is computationally heavy, especially for high-accuracy models like RetinaNet and FR-CNN, which involve composite feature extraction and multi-stage processing. However, training is performed offline, so it does not directly impact the model’s performance. The model’s inference phase cost is reasonable for one-stage detectors (YOLOv11, SSD) and a bit higher for two-stage detectors (FR-CNN). For example, YOLOv11 inference time is ~0.006 s/image, while RetinaNet inference is ~0.053 s/image, and FR-CNN inference is ~0.088 s/image, which makes the proposed approach suitable for real-world clinical applications. The security processes add an overhead of ~0.046 s/image, which is relatively small time but ensures compliance with disabled persons’ privacy regulations. A powerful workstation with 2x Intel Xeon 20-cores CPU, Nvidia Tesla V100 GPU, and 128 GB RAM were used to generate the models’ experimental results in acceptable processing time.

Furthermore, the proposed approach is scalable in real-world clinical settings due to the model’s selection trade-offs, where RetinaNet offers the best accuracy but higher computational demands, making it more suited to clinics prioritizing diagnostic precision over speed, while YOLOv11, being the fastest is ideal for real-time applications such as persons monitoring but may slightly underperform on small or multipart disability cases. This approach presents potential throughput, with inference times well below 0.1 s/image, clinical systems can scale to handle large image volumes if run on capable GPUs or via cloud-based services. Furthermore, this approach shows security integration feasibility that emphasizes limiting data collection and prioritizing privacy, making it easier to integrate into digital technology that could be used in healthcare to manage, store, and share medical images. The proposed approach is scalable for medium-to-large clinical environments with proper hardware or cloud support and balancing accuracy vs. speed based on clinical needs.

Conclusions

Manipulating human disabilities images is a talented research field. Enhancing image classification in this field is a challenge. The proposed approach has a significant impact on identifying people with different disabilities, especially in emergency situations where they may need help. The human disabilities’ images collected in HD-Set were utilized to validate our approach for satisfying the demands of human disabilities classification activity. We evaluated our approach performance by employing five current state-of-the-art object detection models, namely RetinaNet, FR-CNN, SSD, EfficientNet, and YOLOv11. The performance evaluation metrics have been used to measure the efficiency of the deep learning object detection models in comparison. Furthermore, we have measured the top-performing object detection model at two levels, single-class and multi-class object detection models. We have tallied the quantity of testing images for which a certain model produced the best results of each performance parameter that we examined. We have produced a performance histogram for each object detection model in identifying each human disability. The experimental results confirm that the RetinaNet model enabled effective human disability detection and outperformed other approaches in terms of accuracy, F1-score, sensitivity/recall, and MCC. The results generated by this research highlighted that 97.3% of the estimated cases were within ±10° of the actual disabilities. On the other hand, the YOLOv11 model proves the superiority in the speed of identifying human disabilities.

However, this research has some limitations caused by the selected object detection models. Each of these detectors has its trade-offs, and the decision between them is based on the particular requirements of the application, such as how important the real-time performance, detection accuracy, inference speed, detection small object, and computational complexity are. The models’ limitations are described as follows:

Speed vs. accuracy: compared to two-stage models, YOLOv11 and SSD are typically faster but compromise some accuracy.

Small object detection: the RetinaNet model outperforms the YOLOv11 and SSD models, which have trouble detecting small objects.

Real-Time Application: YOLOv11 is best suited for real-time applications because of its speed; nevertheless, it might not be as precise on small or complicated objects.

Computational Complexity: FR-CNN and RetinaNet are less appropriate for real-time applications with limited resources because they are computationally more costly than YOLOv11 and SSD.

Future ambitions to extend the proposed approach and use it for effective human disabilities detection tasks are in line with the new developments in deep learning and medical imaging technology. Intensive ways to improve this research are by identifying human disabilities through face detection and adding additional human disabilities, such as deaf people, to evaluate the effectiveness of our proposed framework and examine the effects of these disabilities on the entire identification process, considering the performance measures employed in this research.

Expanding human disability detection to include face-based diagnosis and hearing-related impairments indicates a powerful evolution of the proposed approach. Integrating these models into real-world clinical workflows supported by robust technical pipelines, privacy-preserving mechanisms, and transparent regulatory strategies can deliver equitable, scalable, and early diagnostic support for larger human disabilities spectrum. Facial features and expressions offer a rich source of diagnostic signs for neurological or developmental disorders, such as autism spectrum disorder, and genetic disorders like Williams syndrome (Bellugi, Sabo & Vaid, 2022). The technical methods that can be used to extract facial features are the 68’s point face landmark combined with convolutional neural network model, trained on autism spectrum disorder datasets with labeled face images, and leverage temporal dynamics to assess involuntary movements, blinking patterns, or expression deficits.

In addition, hearing disabilities detection techniques are behavioral and interaction techniques that can offer alternative solutions to individuals who repeatedly fail to respond to auditory indicators or show excessive use of visual scanning or lip reading. These techniques can be integrated into actual clinical workflows by collecting in-clinic data, developing facial and behavioral models using the collected datasets, assessing the facial and behavioral models’ performance across different deaf persons, embedding the tested models into electronic health record platform, deploying on local GPUs or secure edge devices, and enhancing the models according to the outcomes. These models will empower health leaders, reduce diagnostic delays, and offer meaningful support to deaf individuals who are often underdiagnosed, underserved, or overlooked in traditional healthcare systems.