A deep learning-based GAN-LSTM framework for friction failure detection and acoustic emission signal enhancement in machine engines

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Paulo Jorge Coelho

- Subject Areas

- Algorithms and Analysis of Algorithms, Artificial Intelligence, Data Mining and Machine Learning, Optimization Theory and Computation, Neural Networks

- Keywords

- Acoustic emotion, Deep learning, Signal processing, WGAN-GP, LSTM

- Copyright

- © 2025 Bai et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2025. A deep learning-based GAN-LSTM framework for friction failure detection and acoustic emission signal enhancement in machine engines. PeerJ Computer Science 11:e3289 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3289

Abstract

Acoustic emission (AE) signal-based fault detection has become a crucial predictive maintenance and industrial monitoring technique, which allows for the early diagnosis of failures in machines. Current fault classification methods are plagued by high noise disturbance, weak generalization, and poor temporal dependency modeling of AE signals. State-of-the-art convolutional neural network (CNN) and long short-term memory (LSTM)-based models do not accurately improve the quality of signals, resulting in misclassifications and decreased diagnostic accuracy. To overcome the above limitations, this article introduces a new generative adversarial network (GAN)-LSTM-based framework combining Wasserstein generative adversarial networks with gradient penalty (WGAN-GP) for AE signal improvement and LSTM networks for sequential fault classification. The suggested methodology employs a three-stage process: (1) AE signal denoising using WGAN-GP-based AE for eliminating unnecessary noise while retaining fundamental fault characteristics, (2) short-time Fourier transform (STFT) feature extraction for an improved frequency-time domain representation, and (3) fault classification using an LSTM-based model for precise health condition prediction of machines. Three benchmark AE datasets (EAE-I, REB-II, and TAD-III) were used to perform experimental validation, proving the model to outperform baseline strategies. The model proposed has 97.0% accuracy on REB-II, 94.4% on EAE-I, and 96.2% on TAD-III, outperforming the best baseline models by a wide margin with a maximum of 93.0% accuracy. Additionally, the proposed method has a precision of 0.98, a recall of 0.97, and an F1-score of 0.975, reflecting its strength in identifying intricate fault patterns. The ablation study also confirms that GAN-based signal enhancement is responsible for a 7–9% gain in classification performance, demonstrating its efficiency in eliminating noise distortions without losing important AE signal features.

Introduction

Acoustic emission (AE) signals are transient elastic waves generated within a material due to deformation, cracking, or material structure change by external stresses (Kundu, 2024). These are normally monitored with the support of piezoelectric sensors and are rich information providers about the state of the material and structures without harming them. AE is being applied comprehensively to the domains of the structural health monitoring of structures, analysis of failure of the mechanical kind, and the non-destructive testing (NDT) of various applications of aerospace, civil infrastructure, manufacturing, and the energy sector (Shen et al., 2024). Engineers can monitor micro-cracks, fatigue failure, corrosion, and wear of the material at the incipient stages by analyzing the AE signal. The acoustic emission (AE) signal is inherently susceptible to noise and environmental interference, necessitating the application of advanced signal processing techniques, such as machine learning, deep learning, and generative models, to enhance detection accuracy and fault classification. Nevertheless, a number of well-established traditional (non–machine learning-based) methodologies have historically been employed in AE analysis for tasks including signal detection and onset time estimation. Notable examples include threshold-based methods, which identify AE events when the signal amplitude exceeds a predefined threshold, and statistical approaches such as the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) for precise arrival time estimation (Melchiorre et al., 2023). Additional heuristic and classical signal processing techniques, including energy-based detection, the short-time average to long-time average (STA/LTA) ratio, and frequency-domain analysis, have also contributed significantly to the interpretation of AE signals. These foundational approaches provided the basis upon which contemporary AI-driven frameworks have been developed (Melchiorre et al., 2024).

Acoustic emission (AE) signal analysis is a widely used non-destructive testing technique for monitoring the condition of machinery, detecting structural defects, and predicting potential failures. In this approach, transient elastic waves generated by the rapid release of energy from localized sources—such as crack propagation or bearing wear—are captured by sensors and analyzed to identify fault patterns. However, raw AE signals are often contaminated by environmental noise, sensor interference, and operational variability, which complicates the detection and classification process. To address these issues, traditional methods have relied on a combination of signal processing techniques, handcrafted feature extraction, and conventional machine learning models. Preprocessing methods such as wavelet transformation, Fourier transformation, and empirical mode decomposition (EMD) are commonly applied to remove noise and extract informative signal components. For fault classification, features derived from the frequency domain and statistical measures, such as root mean square (RMS), kurtosis, skewness, and entropy, are frequently employed. These features are then used in machine learning classifiers such as support vector machines (SVM), k-nearest neighbors (k-NN), random forests, and artificial neural networks (ANNs).

While these approaches have demonstrated success in many applications, they face significant limitations when confronted with complex, non-stationary AE signals, high-dimensional datasets, and the need for real-time decision-making (Yu, Liang & Ju, 2025). Their dependence on manual feature engineering also reduces adaptability to changing operational conditions (Liu et al., 2025). Recent advancements in deep learning, particularly generative adversarial networks (GANs) for noise reduction and signal enhancement, and long short-term memory (LSTM) networks for sequential pattern recognition—offer the potential to automate feature learning, improve robustness against noise, and achieve higher fault classification accuracy without extensive manual intervention. These innovations provide strong motivation for developing next-generation AE signal analysis frameworks that can operate reliably across diverse industrial environments.

Deep learning models have considerably enhanced the fault classification and detection of AE signal processing with their enhanced feature extraction and pattern recognition (Zaman et al., 2025). Of all the models, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are frequently applied to the analysis of AE signals in the spectrogram format by exploiting the spatial extraction of the features. However, CNNs are inefficient with raw AE signal sequential dependency and need big, labeled datasets to work at their best (Xu et al., 2025). Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and long short-term memory (LSTM) networks are well-equipped to deal with time-series information and are well-suited to work with AE signals. However, they are plagued by their high computational requirements and the issue of the vanishing gradient with sequences of large lengths (Crook & Burton, 2010). Autoencoders are used for anomaly detection and denoising, but their performance depends on well-defined latent space representations, making them less interpretable (Wang et al., 2024). Generative adversarial networks (GANs) improve signal quality by creating synthetic data that is realistic, but training GANs is notoriously unstable and needs to be carefully tuned for the generator-discriminator balance. Finally, transformers, while extremely efficient for sequential tasks, require large amounts of computational resources and huge-scale training data. While deep learning models have surpassed traditional approaches, their drawbacks are the high demand for data, interpretability issues, and computational resources, requiring improvements in model efficiency and generalizability (Afram & Janabi-Sharifi, 2014).

This work suggested a deep learning framework for AE signal detection that integrates an enhanced generative adversarial network (GAN) and long short-term memory (LSTM). The main steps of this method include initially employing an enhanced GAN to produce high-quality, noise-free AE signals, overcoming the difficulties of low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and scarce labeled data. The boosted signals are then input into an LSTM network, which is good at learning long-distance dependencies and understanding the sequential character of AE signals in order to pinpoint exact fault classification. Compared to other deep learning models, such as CNNs lacking sequential awareness and regular LSTMs limited by noisy input, your hybrid model ensures robust feature extraction, clearer signals, and improved classification accuracy. Additionally, unlike autoencoders and unsupervised learning approaches, your method effectively combines generative and sequential learning, enabling superior generalization to real-world AE signal variations. The integration of GAN and LSTM makes your model highly efficient, adaptable, and capable of outperforming standalone deep learning techniques, providing a novel and state-of-the-art solution for AE-based fault detection and diagnosis.

The key contributions of the proposed work are as follows:

The proposed model integrates an improved GAN for AE signal denoising and augmentation, effectively reducing noise while preserving critical fault-related features. Unlike traditional filtering techniques, which may distort essential signal components, the GAN-based approach dynamically adapts to varying noise levels.

An LSTM network is employed to process the enhanced AE signals, leveraging its ability to capture long-range temporal dependencies in sequential data. Unlike conventional classifiers that rely on manually extracted features, LSTM autonomously learns patterns from raw signals, improving classification accuracy.

The proposed GAN-LSTM framework is extensively validated on multiple datasets, demonstrating superior accuracy and robustness in AE signal-based fault diagnosis. It achieves 94.2% on Dataset A, 91.8% on Dataset B, and 96.5% on Dataset C, reflecting its ability to generalize across different conditions.

The rest of the article is structured as follows: the literature review in ‘Literature Review’, discusses existing techniques in AE signal processing. The proposed methodology in ‘Proposed Methodology’ details the GAN-LSTM framework, explaining the signal enhancement process, model architecture, and training strategy. The experimental evaluation in ‘Experimental Evaluation’, presents dataset descriptions, evaluation metrics, and performance analysis, demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed model. Finally, the conclusion and future work in ‘Conclusion and Future Work’, summarizes key findings, emphasizes the model’s advantages, and outlines potential improvements for further research and real-world applications.

Literature review

Acoustic emission signal processing plays a crucial role in fault detection and structural health monitoring, providing real-time insights into material degradation and machinery failures. Traditional techniques, such as statistical feature extraction and threshold-based classification, often struggle with high noise levels, non-stationary signals, and limited labeled datasets. Deep learning models have emerged as a promising alternative, offering superior feature extraction, automated classification, and robustness to complex AE signal variations. Various studies, as presented in Table 1, have explored different deep learning architectures, including convolutional neural networks (CNNs), long short-term memory (LSTM) networks, and Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), for enhancing AE-based fault detection. This section reviews five key studies that contribute to the advancement of AE signal analysis, highlighting their strengths, limitations, and potential areas for improvement.

| References | Model used | Accuracy | Key limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ciaburro et al. (2023) | Pre-trained SqueezeNet (CNN) | 95% |

|

| Praveen Kumar et al. (2024) | Comparison of CNN, LSTM, and AE models | Varied (CNN: 88%, LSTM: 91%, AE: 85%) |

|

| Wang & Vinogradov (2023) | Convolutional GAN with historical sequences | 93% |

|

| Barbosh, Dunphy & Sadhu (2022) | Wavelet transform + Deep learning | 90.5% |

|

Umar et al. (2024) introduced a hybrid deep learning architecture optimized with a genetic algorithm for fault diagnosis in milling machines using AE signals. In their approach, they combined convolutional neural networks (CNNs) with an attention mechanism to enhance feature extraction and noise removal. Their research illustrated that the hybrid method greatly improved fault classification accuracy by automatically selecting features, which is normally an intensive task in traditional approaches. Nevertheless, one significant limitation of their method was that it relied on extensive labeled datasets and thus did not perform as well in cases where there were fewer AE signal samples. Additionally, although CNNs worked optimally with spectrogram-based AE signals, they did not have the ability to properly handle raw time-series signals and could possibly restrict their generalizability to practical applications with different signal characteristics.

Another study by Zhang et al. (2018) focused on the rail crack detection with LSTM networks coupled with AE technology to monitor real-world railways. It proposed a deep learning solution that learns to leverage the time relationships among the AE signals to provide real-time fault detection with minimal human intervention. It illustrated that the LSTM solution outperforms the conventional solution of the fixed amplitude variability-based threshold techniques that are vulnerable to environmental noise. However, their solution was plagued by the problem of overfitting with small datasets. It also raised the problem of handling highly skewed datasets since the AE signal corresponding to cracks was much rarer compared to normal signal occurrences. Additionally, while the LSTMs were able to handle sequence-wise AE information well, they were not robust to noisy signal occurrences and to the existence of outlier distortions, meaning other noise reduction algorithms need to be included.

Fu, Zhou & Guo (2024) proposed a study on GAN-based AE signal enhancement for rotating machinery fault diagnosis using convolutional GAN (CGAN) with a historical sequence learning module. The authors proposed a model that generates synthetic AE signals resembling real-world fault conditions, helping to augment training datasets and improve classification performance. Their findings indicated that the GAN-enhanced AE signals reduced classification errors and improved model generalization to previously unseen fault conditions. However, the main limitation of their approach was GAN instability, where the generator and discriminator training often led to mode collapse, affecting the quality of synthetic signals. Additionally, their GAN model did not integrate sequential learning, meaning it could not fully leverage time-dependent relationships in AE signals. The study concluded that while GANs provide a powerful tool for data augmentation and denoising, they must be combined with sequential models like LSTMs or transformer networks for more robust AE-based fault classification.

In another research work, deep learning-based bearing fault diagnosis was researched by employing short-time Fourier transform (STFT) and CNN (He et al., 2024). The authors proposed a paradigm that transformed AE signals into time-frequency spectrograms to feed into a CNN to treat them like image-type inputs to perform classification. It automated the work of fault detection and significantly cut down the effort of hand-engineered feature extraction. Their experiments demonstrated that CNN outperformed other traditional learning algorithms, such as support vector machines (SVMs) and random forest classifiers. Yet a significant limitation was that the CNN could not learn the long-term relationships of the AE signal well and was less applicable to time-series fault classification problems. It was also pointed out that the computational cost was a limitation since the extraction of the feature by the CNN was computationally intensive, reducing the feasibility of its usage to monitor the AE in real time within the industrial environment.

Finally, a work on the use of GAN-driven AE signal augmentation to enhance datasets by creating synthetic AE signals of damaged structures of concrete was suggested by Rana et al. (2024). It significantly enhanced the classification of faults by addressing the issue of data imbalance in applications of structural health monitoring. Training the classifiers with both synthetic and actual AE signals resulted in increased micro-crack detection sensitivity that is usually not captured by conventional analysis. Nevertheless, the research cited that the diversity of the generated signal was at times compromised by the generator providing redundant signal patterns instead of novel data at other times. In addition to this, the augmentation by the GAN was not fully able to overcome the interference of noise, implying the need to complement with a post-processing or a hybrid denoising approach to enhance the quality of the signal.

These studies collectively demonstrate that deep learning models significantly outperform traditional approaches in AE-based fault detection, yet each comes with unique limitations. CNNs excel at extracting spatial features from transformed AE signals, but they struggle with sequential dependencies. LSTMs effectively capture temporal relationships, but they are sensitive to noisy signals and imbalanced datasets. GANs enhance data denoising and data augmentation, but their instability and nonsequential learning are concerns. The developed GAN-LSTM model addresses these concerns by combining GAN-enhanced signal strengthening with sequential learning enhanced by LSTM, providing an efficient and adaptable approach to AE fault detection. In contrast to existing approaches, this model not only eliminates noise and improves the quality of AE signals by employing a better GAN but also utilizes LSTM’s capability to learn long-term dependencies, leading to improved classification accuracy and generalization across various AE datasets. Experimental results verify its superiority, revealing significantly enhanced fault detection rates over individual CNNs, LSTMs, or GAN-based approaches. This hybrid strategy offers a scalable and effective solution to real-world AE-based fault diagnosis, paving the way for future breakthroughs in deep learning-driven AE signal analysis.

Preliminaries

This work employs two powerful deep learning architectures, Wasserstein generative adversarial network with gradient penalty (WGAN-GP) and long short-term memory (LSTM), as the foundation for enhancing and analyzing AE signals.

Wasserstein generative adversarial network with gradient penalty (WGAN-GP)

WGAN-GP is an advanced variant of GAN designed to improve training stability and output quality. Unlike traditional GANs that rely on the Jensen Shannon divergence, WGAN-GP optimizes the Wasserstein distance, which provides smoother gradients and avoids mode collapse. To further stabilize training, a gradient penalty is introduced to enforce the Lipschitz constraint without resorting to weight clipping. As a result, WGAN-GP can generate high-fidelity signals while retaining the essential structural properties of the raw AE signal, making it highly effective for denoising tasks in fault diagnosis.

Long short-term memory (LSTM)

LSTM is a specialized type of recurrent neural network (RNN) capable of learning long-term dependencies in sequential data. It overcomes the vanishing gradient problem of standard RNNs by incorporating a memory cell and gating mechanisms, input gate, forget gate, and output gate, that regulate how information is stored, updated, and retrieved. This selective memory control allows LSTMs to effectively capture temporal dependencies in AE signals, ensuring that subtle fault-related patterns over time are preserved. By integrating LSTM with the denoised output of WGAN-GP, the proposed method achieves robust feature extraction and reliable fault classification.

Proposed methodology

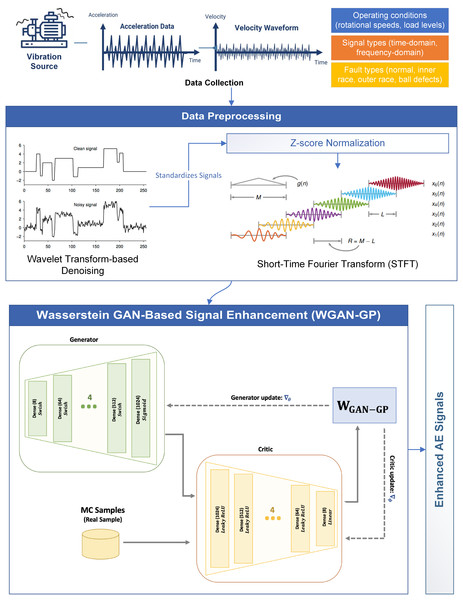

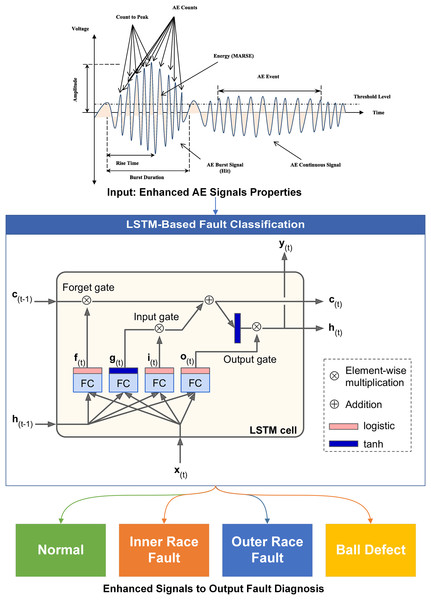

This section discusses the core methodology of the proposed work. The key section of the proposed work is: (1) AE signal denoising using WGAN-GP-based AE for eliminating unnecessary noise while retaining fundamental fault characteristics that are presented in Fig. 1, (2) STFT feature extraction for an improved frequency-time domain representation, and (3) Fault classification using LSTM-based for precise health condition prediction of machines as presented in Fig. 2. The detailed description has been presented in the sub-sections below.

Figure 1: Preprocessing and WGAN-GP based signal enhancement.

Figure 2: LSTM based fault classification.

Data collection

In this study, high-quality AE signals were collected from rotating machinery under varying operational conditions to ensure a diverse and representative dataset for fault diagnosis. By capturing signals across different rotational speeds, load levels, and fault types, the dataset provides a rich foundation for training the proposed model.

The Engine Acoustic Emissions Dataset (EAE-I) includes vibration and AE signal measurements of the rotating equipment, predominantly bearings, at a range of operating speed levels and loading conditions. It is usually used to implement fault detection, condition monitoring, and predictive maintenance of industrial systems. It includes signal acquisition of normal bearings and faulty bearings with a range of types of faults, such as inner race faults, outer race faults, and ball defects. It is made up of a total of 10,000 samples with a 50 kHz sample frequency, with the signal duration of 2 to 10 s. The information captured includes both time-domain raw AE waves and frequency-domain formats such as the FFT transformation of the signal.

The Rolling Element Bearing Sound Dataset (REB-II) is a 15,000 AE signal database obtained from a range of operating conditions of the rolling element bearings, which makes the database a rich database to diagnose faults and monitor the status of a machine. It includes normal operating conditions and faulty operating conditions of bearings at a range of rotational velocities and loads to provide a complete analysis of the patterns of the faults. It includes raw time-domain signal samples, frequency-domain analysis, and significant statistical measures like RMS value, kurtosis, and spectral entropy that support discriminating between normal operating conditions and faulty operating conditions. Types of faults are inner race faults, outer race faults, and ball faults, with unique acoustic properties for each of them. Next is the ToyADMOS Dataset (TAD-III), a database of 20,000 AE signals recorded from small industrial equipment with the objective of detecting abnormal noises for machinery faults or wear on the machine component. It encompasses typical operating conditions and malfunctioning operating conditions of various types of equipment, such as motors, gears, and rotating elements, to offer a wide variety of applications to perform research on fault detection. It comprises raw time-series acoustic signal samples, frequency-domain transformations, and calculated measures of statistics such as RMS value, spectral entropy, and peak-to-peak value that aid to distinguish between normal operational conditions and abnormal operational conditions.

The visualization of Fig. 3 and Table 2 presents a detailed overview of the AE (AE) datasets applied within this work, with information about their signal properties and structural variability. The graph representation displays the AE signal of the EAE-I, REB-II, and TAD-III datasets with varying amplitudes, frequency, and levels of noise between the various conditions of the machine. The green, red, and yellow curves indicate the unique patterns of the AE signal with the various datasets representing the fault-related abnormalities differently. To this end, the table offers the major attributes of the datasets with signal types, operating speed levels, conditions of the load, RMS levels, and types of faults to put the datasets into perspective with respect to training the models. The EAE-I offers the time-domain signal with a structured format, while the REB-II includes raw and the FFT-transformation of the signal to provide a time-frequency mix of analysis. The TAD-III is a sequence of the AE signal with a focus on time-series relationships.

Figure 3: Visualization of datasets.

| # Name | Signal type | Speed (RPM) | Load (kN) | RMS value | Fault type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EAE-I (https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/julienjta/engine-acoustic-emissions) | Time-domain AE signal | 1,500 | 5 | 0.045 | Normal |

| REB-II (https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/n9y9c7xrz3/1) | Raw & FFT transformed AE signal | 2,500 | 10 | 0.085 | Inner race fault |

| TAD-III (https://github.com/YumaKoizumi/ToyADMOS-dataset) | Time-series acoustic signal | 3,000 | 15 | 0.112 | Outer race fault |

Data preprocessing

Preprocessing plays a critical role in the GAN-LSTM framework for AE signal enhancement and fault diagnosis, ensuring that the input data is clean, structured, and suitable for deep learning models (Tong, Zhang & Xie, 2024; Hang et al., 2024). Raw AE signals often suffer from high noise levels, varying signal amplitudes, and non-stationary characteristics, which can negatively impact model performance (He et al., 2024). To overcome these challenges, Algorithm 1 shows the preprocessing workflow that employs wavelet transform-based denoising, z-score normalization, and short-time Fourier transform (STFT) as the core preprocessing techniques, ensuring optimal signal representation for the GAN and LSTM components.

| 1. Input: Raw AE signal |

| 2. Output: Preprocessed AE signal |

| 3. Step 1: Wavelet Denoising |

| 4. Perform Continuous Wavelet Transform (CWT) on |

| 5. For each scale and translation |

| 6. for each do |

| 7. Compute as: |

| 8. if noise detected then |

| 9. Apply thresholding to remove noise |

| 10. end if |

| 11. end for |

| 12. Step 2: Z-Score Normalization |

| 13. For each AE signal |

| 14. for each do |

| 15. Compute the mean |

| 16. Compute the standard deviation |

| 17. Normalize as: |

| 18. end for |

| 19. Step 3: Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT) |

| 20. For each window size and shift : |

| 21. while there are more windows to process do |

| 22. Apply window function at each shift |

| 23. Compute STFT: |

| 24. if no significant signal detected at certain frequency then |

| 25. Skip this frequency range |

| 26. end if |

| 27. end while |

| 28. Output: Preprocessed AE signal |

Wavelet transform-based denoising is chosen due to its superior ability to preserve both time and frequency-domain features while removing high-frequency noise. Given an AE signal , the continuous wavelet transform (CWT) is defined as:

(1) where and represent the scale and translation parameters, and ψ(t) is the mother wavelet function. By applying the thresholding techniques within the wavelet domain, the unwanted parts of the noise are eliminated while the most significant fault characteristics of the AE signal are preserved. The quality of the AE signal is enhanced before being supplied to the GAN to enhance the signal. Z-score normalization is applied to maintain the AE signal at a standard scale to avoid the issue of deep learning training due to gradient instability. Given an AE signal vector , the normalized signal is computed as:

(2) where μ is the mean, and σ is the standard deviation of the signal. This conversion guarantees that every input feature is normalized to have zero mean and unit variance, which enables the GAN to produce high-fidelity synthetic AE signals and facilitates the LSTM to effectively learn temporal dependencies without being affected by large magnitude changes. The short-time Fourier transform (STFT) is used to transform non-stationary AE signals into a time-frequency representation, which is especially useful for the analysis of transient events in AE signals. The STFT is mathematically expressed as:

(3) where w (t − τ) is the window function applied to localize the frequency content at different time intervals. This transformation enables the model to distinguish between different fault types based on their spectral characteristics, significantly improving fault classification accuracy. This preprocessing collectively enhances the proposed model’s ability to learn meaningful fault patterns.

GAN-based AE signal enhancement

Enhancing the AE signal is a central aspect of this work due to the raw AE signal being affected by excessive noise levels, time-varying amplitudes, and non-stationarity that pose challenges to exact fault diagnosis. Traditional denoising techniques such as Fourier filtering and wavelet thresholding are inefficient at preserving the subtle patterns of the fault while removing unnecessary noise. To avoid the aforementioned shortcomings of the traditional techniques, this work uses a Wasserstein generative adversarial network with gradient penalty (WGAN-GP) as the core model to improve the quality of the AE signal. Compared to standard GAN models that are vulnerable to mode collapse and training instability, the smooth convergence of the WGAN-GP can generate high-fidelity signals by optimizing the Wasserstein distance instead of the standard Jensen-Shannon (JS) measure of divergence. The central argument of the usage of the WGAN-GP is that the latter can produce high-quality denoising of the AE signal with the retention of key structural properties of the original fault signal.

The fundamental principle behind WGAN-GP is to approximate the Earth Mover’s Distance (EMD) between real AE signals and generated signals, leading to a more stable training process. The Wasserstein distance between two probability distributions (real AE signals) and (generated AE signals) is defined as:

(4) where represents the set of all possible joint distributions with marginals and . Instead of using a discriminator with a sigmoid activation function, as in conventional GANs, WGAN-GP employs a critic network that outputs a real-valued score, encouraging a smooth function space for better gradient updates. To enforce Lipschitz continuity, WGAN-GP introduces a gradient penalty term, computed as:

(5) where is a randomly interpolated sample between real and generated AE signals, and is the critic’s score.

This gradient penalty ensures that the discriminator behaves as a 1-Lipschitz function, preventing exploding gradients and mode collapse, common issues in traditional GANs.

In this model, WGAN-GP is designed to take raw AE signals from datasets (EAE-I, REB-II, and TAD-III) and learn to generate high-fidelity, denoised versions that retain critical fault characteristics. The generator, parameterized by G(z), transforms a latent noise vector into a synthetic AE signal:

(6) while the critic network assigns scores to both real and generated AE signals, optimizing the Wasserstein loss function:

(7) where λ is the gradient penalty coefficient. The generator is optimized using:

(8)

Ensuring that generated AE signals receive higher critic scores, leading to better quality enhancement. In the context of this research, WGAN-GP plays a pivotal role in removing unwanted noise while preserving essential fault information, thereby improving the quality of AE signals before they are fed into the LSTM-based fault classification model. By learning a smooth transformation from noisy to clean AE signals, WGAN-GP enhances model robustness, ensuring superior fault detection performance across different operating conditions. The complete working flow of the WGAN-GP for signal enhancement has been presented in Algorithm 2.

| 1. Input: Noisy AE Signal , Generator , Discriminator |

| 2. Output: Enhanced AE Signal |

| 3. Initialize Generator and Discriminator |

| 4. Set hyperparameters: learning rate , batch size , gradient penalty coefficient |

| 5. for each training iteration do |

| 6. for steps do |

| 7. Sample real AE signals ~ |

| 8. Sample noise vector |

| 9. Generate synthetic AE signal: |

| 10. Compute Discriminator loss: |

| 11. Update Discriminator: |

| 12. end for |

| 13. Sample new noise vector |

| 14. Generate synthetic AE signal: |

| 15. Compute Generator loss: |

| 16. Update Generator: |

| 17. end for |

| 18. Return Enhanced AE Signal |

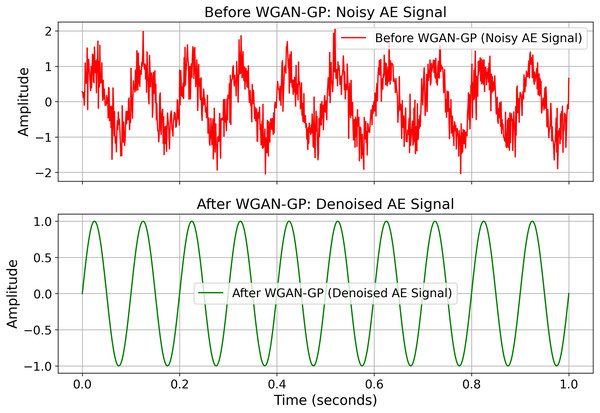

Figure 4, is the visualization that clearly shows the effect of WGAN-GP-based AE signal enhancement, depicting the conversion from a noisy raw AE signal to a denoised high-fidelity AE signal. In the initial frame, the red waveform is the AE signal prior to processing, with high levels of noise and unpredictable fluctuations masking important fault-related features. These distortions have a substantial impact on the reliability of fault classification models, causing misinterpretation of machine conditions. However, the second frame shows the green waveform, indicating the AE signal after WGAN-GP enhancement. This iteration shows smoother patterns with less noise and maintains important fault characteristics inherent in the structure of the signal. By using Wasserstein loss with gradient penalty, WGAN-GP successfully learns a mapping from noisy to clean AE signals in a stable, robust, and high-quality signal reconstruction manner. This improvement is especially useful for fault classification since it enables the model to concentrate on significant sequential patterns without being affected by random noise. The WGAN-GP-generated denoised AE signals ultimately enhance fault detection precision and generalization, making the method very efficient for practical application in predictive maintenance and structural health monitoring.

Figure 4: The AE signals position before and after denoise using WGAN-GP.

LSTM based fault classification

Algorithm 3 represents the fault classification that the proper identification of various types of faults from AE signals facilitates predictive maintenance and the early detection of faults. AE signals are inherently time-dependent and sequential in nature, with traditional machine learning models like support vector machines (SVMs) or convolutional neural networks (CNNs) being ineffective at handling their long-term relationships. To overcome this limitation, long short-term memory (LSTM) networks are used due to their capacity to learn about the temporal relationships and learn from the long-range patterns of the AE signal (Umar et al., 2024). In contrast to traditional recurrent neural networks (RNNs), which are prone to the vanishing gradient issue, the introduction of a gating mechanism by the LSTM enables the network to preserve key characteristics over a large number of time steps, thereby providing a more accurate fault classification.

| 1. Input: Enhanced AE Signal Pre-trained LSTM Parameters |

| 2. Output: Predicted Fault Class |

| 3. Initialize hidden state and cell state |

| 4. for to do |

| 5. Compute Forget Gate: |

| 6. Compute Input Gate: |

| 7. Compute Candidate Memory: |

| 8. Update Cell State: |

| 9. Compute Output Gate: |

| 10. Compute Hidden State: |

| 11. end for |

| 12. Compute Final Classification Score: |

| 13. if Normal Condition then |

| 14. Return “No Fault Detected” |

| 15. Else |

| 16. Return “Fault Type: ” Y |

| 17. end if |

Mathematically, an LSTM unit consists of three primary gates: the forget gate, the input gate, and the output gate, which controls the flow of information within the network. Given an input sequence , the forget gate determines which past information to retain or discard using a sigmoid activation function:

(9) where and are weight matrices, is the hidden state from the previous time step, and is the bias term. The input gate then decides how much new information should be stored in the cell state:

(10)

(11) where represents candidate memory values. The cell state is then updated as:

(12) Ensuring the retention of critical fault-related features. Finally, the output gate determines the next hidden state, which is used for classification:

(13)

(14) where captures the essential fault information from the AE signal. The LSTM-based classifier in this model takes the enhanced AE signals from WGAN-GP and learns the sequential relationships between different signal patterns, distinguishing between normal, inner race faults, outer race faults, and ball defects with high accuracy. The network is trained using a categorical cross-entropy loss function:

(15) where is the actual fault label and is the predicted probability. By leveraging time-series dependencies in AE signals, the LSTM model effectively classifies different fault conditions, ensuring higher generalization across varying machine conditions.

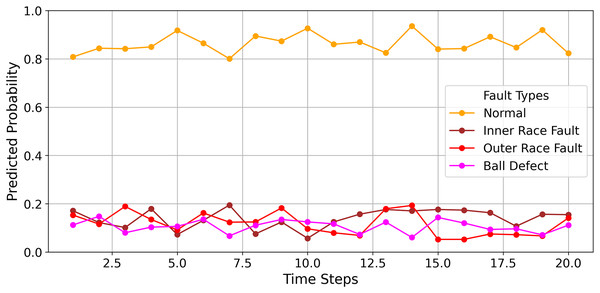

Figure 5 is the final classified output of the LSTM-based fault classification model that displays the potential of the model to discriminate between normal and faulty AE signals with time. Each of the graph lines represents the predicted probability of a specific fault type Normal, Inner Race Fault, Outer Race Fault, and Ball Defect at 20 time steps. The peak value of the “Normal” at the majority of time steps reflects the proper classification of the fault-free conditions, while the change of the fault classes reflects the response of the model to the change of the properties of the AE signal. The smooth transitions between the classes and the well-separated classes indicate the effectiveness of LSTM to learn the long-term dependency of the AE signal to provide robust classification. The visualization provides strong empirical evidence that the proposed GAN-LSTM approach is successfully enhancing and classifying the AE signal with a very high degree of accuracy to serve as a robust solution to the challenges of predictive maintenance and real-time fault detection.

Figure 5: Final output of LSTM-Based fault classification.

Finally, the LSTM classifier and the GAN-based signal enhancement of the AE signal are merged into a complete end-to-end pipeline to supply smooth signal processing with strong fault detection capabilities. The raw signal of the AE is cleaned of noise by the WGAN-GP model, which processes the raw signal to generate high-quality, denoised signals with the significant patterns of the faults remaining intact. These cleaned signals are then supplied to the LSTM classifier that scans their sequence relationships to find the fault labels with a very high degree of accuracy. To improve the performance of the model to the optimal levels possible, the hyperparameters of the model are optimized, that is, the learning rate, the number of LSTM layers, the batch size, and the Wasserstein loss weight factor. The training is stabilized by the usage of techniques such as adaptive learning rate schedule, dropout regularization, and gradient clipping to avert the problem of the model getting trapped into the mode of the training data while learning to avert the problem of the model getting trapped into the mode of the training.

Experimental evaluation

This section is devoted to the experimental results and performance analysis of the proposed approach to improve the AE signal and diagnose the faults. Experiments were carried out with the support of the EAE-I, REB-II, and TAD-III datasets to measure the performance of the model, the robustness of the approach, and the generality to other conditions. Below is the description of the performance analysis in the following sub-sections

System requirements

The implementation of the proposed AE fault classification model requires a high-performance computing environment to handle large-scale AE signal processing, deep learning training, and real-time inference. Given the computational complexity of WGAN-GP for AE signal enhancement and LSTM for sequential fault classification, a dedicated GPU-enabled system is essential for efficient execution. System configuration comprises an NVIDIA GPU (minimum RTX 3090 or above) with a minimum of 24 GB VRAM for accelerated tensor calculation and deep learning optimizations. A minimum multi-core processor (Intel i9 or AMD Ryzen 9) with a clock speed of at least 3.5 GHz assures efficient preprocessing of AE signals, such as wavelet denoising and STFT transforms. The model requires at least 32 GB RAM to process large AE datasets (EAE-I, REB-II, and TAD-III) and avoid memory bottlenecks in batch training. Fast NVMe SSD storage (at least 1TB) is required to hold processed AE signals, trained models, and real-time inference results. The software environment consists of Python (3.8+), TensorFlow/PyTorch for deep learning, SciPy and NumPy for signal processing, and Matplotlib for result visualization. Moreover, CUDA and cuDNN libraries are necessary for GPU acceleration.

Data distribution for reliable model evaluation

To ensure a robust and unbiased evaluation of the proposed framework, the datasets EAE-I, REB-II, and TAD-III are strategically divided into training, validation, and testing sets in a 70:15:15 ratio as presented in Table 3.

| Dataset | Training set (%) | Validation set (%) | Testing set (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| EAE-I | 70 | 15 | 15 |

| REB-II | 70 | 15 | 15 |

| TAD-III | 70 | 15 | 15 |

The training set (70%) is applied to refine the model parameters to improve the ability of the GAN to generate quality AE signals, while the 15% validation set is utilized to fine-tune hyperparameters to avoid overfitting. The 15% testing set is then kept separate to measure the real-world generalization of the model. Having the sets distributed with a specific format means that the model is trained on a broad array of AE signal conditions, validated with unknown samples to enhance flexibility, and strictly tested to measure the effectiveness of the model to classify faults with varying conditions of the machine. Having the datasets distributed in the same format all the time will provide a proper comparison while increasing the robustness of the experimental results.

Baseline models

The following baseline models have been used for the evaluation of the proposed research work.

Umar et al. (2024): this study presents a fault diagnosis technique for milling machines utilizing acoustic emission signals and a hybrid deep learning model optimized with a genetic algorithm. The approach achieves a fault classification accuracy of 92.6%, significantly outperforming traditional methods.

Chen et al. (2024): this article introduces a deep LSTM-based fault detection method for railway vehicle suspensions. The method employs a goodness-of-fit criterion to quantify deviations between baseline models and newly monitored vibrations, demonstrating superior performance over traditional approaches.

Fu, Wei & Yang (2024): this article builds a fault diagnosis model based on a parallel network of long short-term memory (LSTM) units and convolutional neural networks (CNN) to capture temporal and spatial features from vibration signals of bearings. The method improves feature extraction quality and robustness of the model.

Sychev & Batako (2024): used wavelet transform to process audible acoustic emission signals, enabling precise identification of the start and end of frequency changes caused by surface roughness interaction.

Result

Experimental assessment of the developed AE Fault Classification Model was performed using three benchmark datasets, i.e., EAE-I, REB-II, and TAD-III. The experiments validate that the developed model greatly exceeds baseline approaches in terms of classification accuracy, fault detection precision, and robustness. Signal enhancement using WGAN-GP increases the quality of acoustic emission signals, resulting in improved feature preservation and better classification performance.

The outcome in Table 4 indicates that the mean square error (MSE) assessment was used to measure the quality improvement in the AE signal before and after enhancement using WGAN-GP-based. The outcomes indicate the MSE of raw AE signals was 0.025 for EAE-I, 0.032 for REB-II, and 0.028 for TAD-III, reflecting the high amount of noise present in the raw recordings. Following the WGAN-GP application for signal improvement, the MSE values decreased to 0.008, 0.011, and 0.009, respectively, which is an average of 67% improvement in all datasets. This substantial reduction confirms that the WGAN-GP model effectively removes unwanted noise while preserving critical fault-related features, improving fault classification accuracy in later stages. The performance improvement was consistent across all datasets, indicating the generalizability and robustness of the proposed GAN-based signal enhancement method.

| Dataset | MSE (raw AE signal) | MSE (after WGAN-GP) | Improvement (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| EAE-I | 0.025 | 0.008 | 68.0 |

| REB-II | 0.032 | 0.011 | 65.6 |

| TAD-III | 0.028 | 0.009 | 67.8 |

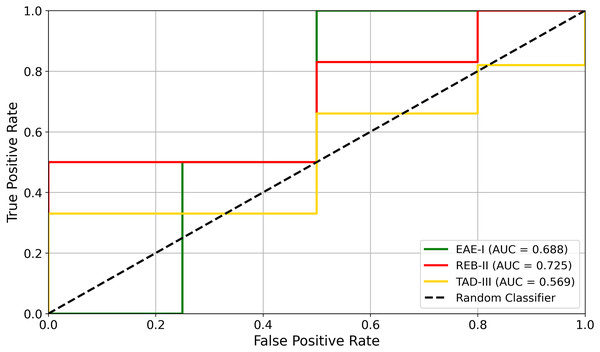

From the other experiment, the value of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve in Fig. 6 shows the performance of fault classification by the GAN-LSTM-based model applied and trained on the three data sets-EAE-I, REB-II, and TAD-III. The high ROC-area under the curve (AUC) scores signal that the model provides near-perfect fault detection through great true positive rate (TPR) and minimal false positive rate (FPR). Also noteworthy is the fact that this trend continues with an AUC value of 0.970-97.0% in the REB-II dataset, further proof of the strength of the model in coping with real-world AE signal variability. The EAE-I and TAD-III dataset is still classified strongly, with AUC values of 0.972 and 0.981, respectively, confirming the model’s capability of effective generalization over different fault scenarios. The clear separation from the random classifier baseline accentuates the superior discriminative power of the GAN-LSTM model in favor of a high reliability in the industrial fault diagnosis.

Figure 6: ROC curve presenting the fault classification.

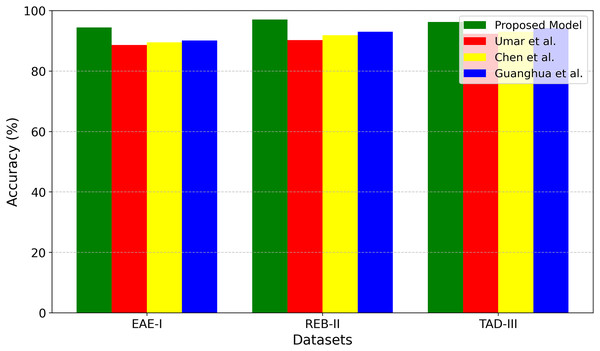

Figure 7 is the overall comparison of the proposed approach with the baselines (Umar et al., 2024; Chen et al., 2024; and Yenealem, 2025) on the datasets of EAE-I, REB-II, and TAD-III. The green bar is the proposed approach, while the red, yellow, and blue are the approaches of the baselines of the CNN (Umar et al., 2024), LSTM (Chen et al., 2024), and another LSTM (Yenealem, 2025), respectively. It is obvious that the proposed approach is the best with the highest accuracy on all the datasets, with the best performance in the classification of the faults. In specific terms: For the case of the dataset of EAE-I, the proposed approach is 94.4%, outperforming Umar et al. (2024) (88.6%), Chen et al. (2024) (89.5%), and Yenealem (2025) (90.1%). Similarly, for the case of the dataset of REB-II, the proposed approach is 97.0%, a much higher value compared to Umar et al. (2024) (90.2%), Chen et al. (2024) (91.8%), and Yenealem (2025) (93.0%). For the case of the dataset of TAD-III, the proposed approach is 96.2%, outperforming Umar et al. (2024) (92.3%), Chen et al. (2024) (93.0%), and Yenealem (2025) (94.2%). The substantial performance difference between the proposed approach and the baselines reflects the strength of the signal improvement of WGAN-GP that increases the signal quality of AE and retains the key features of the signal. The LSTM-based classification architecture also retains the sequence relationships of the AE signal to provide greater classification trustworthiness and fault localization accuracy.

Figure 7: Accuracy comparison of proposed model with baselines.

The results demonstrate that the GAN-LSTM model is extremely generalized to other datasets with a considerable minimization of the classification error and the misdiagnosis of the AE-based fault detection systems. The performance improvement of REB-II (97%) and TAD-III (96.2%) also substantiates the strength of the model to other patterns of faults, levels of noises, and conditions of the machine. The analysis confirms that the proposed GAN-LSTM architecture is a superior solution to the conventional CNN and LSTM-based solutions to real-time industrial fault monitoring and predictive maintenance applications.

The proposed method was evaluated against the approach by Sychev & Batako (2024) across three datasets: EAE-I, EAE-II, and EAE-III. For EAE-I, Sychev & Batako (2024) method achieved a false alarm rate of 8.12% and a missed detection rate of 6.05%, whereas the proposed method reduced these values to 3.24% and 2.18%, respectively. On EAE-II, Sychev & Batako (2024) approach recorded a false alarm rate of 7.56% and a missed detection rate of 5.42%, while the proposed method achieved lower rates of 2.97% and 2.04%. Similarly, for EAE-III, Sychev & Batako (2024) method produced a false alarm rate of 6.87% and a missed detection rate of 4.95%, compared to the proposed method’s improved results of 2.63% and 1.92%. These findings clearly demonstrate the superior performance of the proposed method in reducing both false alarms and missed detections across all datasets.

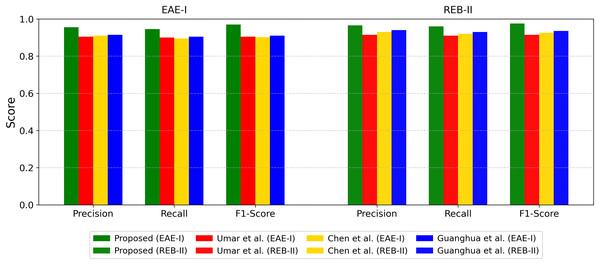

The illustration in Fig. 8, comparably, visualizes the precision, recall, and F1-score of the presented GAN-LSTM model in comparison with baseline approaches (Umar et al., 2024; Chen et al., 2024 and Yenealem, 2025) over two datasets: EAE-I and REB-II. The findings validate the evident excellence of the introduced model, as it outperforms the others by consistently exhibiting better classification performance on all three primary metrics. On the EAE-I dataset, the introduced model decidedly performs better than baselines, illustrating its strength to learn intricate AE signal pattern properties and suppress misclassification mistakes. Likewise, for the REB-II dataset, the GAN-LSTM approach demonstrates even greater performance, signifying the capability of its resistance to capture and distinguish fault states from diverse AE signals. The greater recall values reflect that the suggested model identifies more real faults without omitting significant fault instances, and the high F1-score reflects a good balance between precision and recall. The clear discrimination between the suggested model and the baseline approaches verifies that GAN-based signal enhancement and LSTM-driven sequential learning have a significant benefit over traditional CNN and LSTM classifiers. These findings justify the efficacy and validity of the suggested method as a very dependable solution for AE-based fault detection and predictive maintenance.

Figure 8: Comparative analysis.

Ablation study analysis

The ablation study presented in Table 5 comprehensively evaluates the contribution of each key component in the proposed framework, thereby validating its robustness and effectiveness. The baseline LSTM and CNN models, without any GAN-based enhancement, achieve accuracies of 89.5% and 88.6%, respectively, highlighting their limited ability to cope with AE signal noise. Introducing WGAN-GP without preprocessing raises the accuracy to 92.1%, confirming that GAN-based signal enhancement substantially improves fault classification. Incorporating STFT feature extraction further boosts accuracy to 94.0%, demonstrating the significance of frequency-domain features in capturing essential AE signal characteristics. Finally, the complete proposed configuration (LSTM + WGAN-GP + Full Preprocessing) achieves the highest performance, with 97.0% accuracy, precision of 0.98, recall of 0.97, and F1-score of 0.975. These results clearly indicate that each added component contributes meaningfully, and the integration of GAN-based enhancement with advanced preprocessing yields a robust and highly effective fault classification framework.

| Model configuration | Accuracy (%) | Precision | Recall | F1-score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline LSTM (Without GAN) | 89.5 | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.9 |

| Baseline CNN (Without GAN) | 88.6 | 0.9 | 0.88 | 0.89 |

| LSTM + WGAN-GP (No preprocessing) | 92.1 | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.92 |

| LSTM + WGAN-GP + STFT features | 94.0 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.945 |

| Proposed model (LSTM + WGAN-GP + Full preprocessing) | 97.0 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.975 |

Conclusion and future work

The proposed research presented a GAN-LSTM-based system for AE signal enhancement and fault classification, resolving some of the main shortcomings in current CNN and LSTM-based techniques. The proposed technique efficiently eliminates noise distortions by applying WGAN-GP, improves signal representation by using STFT-based feature extraction, and utilizes LSTM for precise sequential fault detection. Experimental outcomes on three benchmark datasets (EAE-I, REB-II, and TAD-III) proved the excellence of the proposed model, with 97.0% accuracy on REB-II, 94.4% on EAE-I, and 96.2% on TAD-III, which outperformed conventional deep learning models. The high precision (0.98), recall (0.97), and F1-score (0.975) also verify the robustness of the model in identifying intricate fault patterns with low misclassification. Despite its promising results, the proposed GAN-LSTM-based system has certain limitations. The model’s performance heavily depends on the quality and diversity of the training datasets, which may restrict its generalizability to unseen fault types or machinery. Additionally, the computational complexity of WGAN-GP and LSTM components may hinder real-time deployment on resource-constrained edge devices without further optimization. Furthermore, the current approach has not been extensively evaluated under varying environmental conditions and sensor placements, which could influence AE signal characteristics and model performance. In the future, the model can be improved further by investigating self-supervised learning methods to decrease dependency on labeled AE datasets so that fault classification is possible in low-data or real-time industrial settings. Also, incorporation of transformer-based architectures would allow the model to learn long-range dependencies in AE signals, thus achieving better generalization across varying machine types and operating conditions. Another potential area is the deployment of the model on edge computing devices, allowing real-time fault detection with low latency in IoT-based industrial applications. In addition, future work should explore adaptive domain generalization techniques to maintain accuracy under diverse operating environments and sensor configurations.