Multi-LLM information retrieval pipeline for extracting deep learning methodologies in biodiversity research

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Bilal Alatas

- Subject Areas

- Algorithms and Analysis of Algorithms, Artificial Intelligence, Data Mining and Machine Learning, Optimization Theory and Computation, Neural Networks

- Keywords

- Deep learning, Large language models, Retrieval augmented generation, Biodiversity, Reproducibility, Human annotators

- Copyright

- © 2025 Kommineni et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2025. Multi-LLM information retrieval pipeline for extracting deep learning methodologies in biodiversity research. PeerJ Computer Science 11:e3204 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3204

Abstract

Deep learning (DL) techniques are increasingly applied in scientific studies across various domains to address complex research questions. However, the methodological details of these DL models are often hidden in the unstructured text, making it difficult to extract and interpret critical information about their design, training, and evaluation. To address this issue, in this work, we present a pipeline that leverages five different open-source large language models (LLMs): Llama-3 70B, Llama-3.1 70B, Mixtral-8x22B-Instruct-v0.1, Mixtral 8x7B, and Gemma 2 9B in combination with retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) approach to extract and process DL methodological details from scientific publications automatically. To ensure accurate reporting of DL methodologies, we developed a voting classifier based on the outputs of these five LLMs. We demonstrate the utility of this approach in biodiversity research, testing it on two datasets of DL-related biodiversity publications: a curated set of 100 publications and an additional set of 364 publications from the Ecological Informatics journal. Our results demonstrate that the multi-LLM, RAG-assisted pipeline enhances the retrieval of DL methodological information, achieving an accuracy of 69.5%, with precision (61.8%), recall (89.3%), and F1-score (67.5%) based solely on textual content from publications which further demonstrates our pipeline robustness. This performance was assessed against human annotators who had access to code, figures, tables, and other supplementary information. Additionally, the cosine similarity between the responses of different LLM pairs, ranging from 0.39 to 0.68, highlights the variability in model outputs. The voting classifier leverages this variability to improve the final results. Although demonstrated in biodiversity, our methodology is not limited to this field; it can be applied across other scientific domains where detailed methodological reporting is essential for advancing knowledge and ensuring reproducibility. This study presents a scalable and reliable approach for automating information extraction, facilitating better reproducibility and knowledge transfer across studies.

Introduction

Deep learning (DL) has become a cornerstone in numerous fields, revolutionizing how complex data is analyzed and interpreted. From healthcare and finance to autonomous systems and natural language processing (NLP), DL techniques have delivered groundbreaking results. With this rapid adoption, there is growing emphasis on the need for transparent reporting of DL methodologies including model design, training, evaluation, and deployment processes to support reproducibility, interpretability, and scientific integrity (Waide, Brunt & Servilla, 2017; Stark, 2018; Samuel, Löffler & König-Ries, 2021; Pineau et al., 2021; Gundersen, Shamsaliei & Isdahl, 2022). However, in practice, such methodological details are often inconsistently documented or embedded within unstructured text in research articles, making them difficult to access, evaluate, or reuse (Feng et al., 2019; GPAI, 2022).

For a DL pipeline (El-Amir & Hamdy, 2020) to be reproducible, detailed documentation at each stage is essential (Pineau et al., 2021). This includes logging data collection methods, preprocessing steps, model architecture configurations, hyperparameters, and training details, as well as performance metrics and test datasets. Additionally, maintaining records of software libraries, hardware, frameworks, and versions used is critical for the accurate replication of the study. Without access to such crucial information, stakeholders including academics, industry professionals, and policymakers face significant challenges in validating study outcomes or advancing research in meaningful ways. In areas like healthcare, finance, and autonomous systems, where DL applications influence real-world decisions, the absence of methodological transparency can compromise trust in DL models and limit their broader application (Haddaway & Verhoeven, 2015). We contend that the same holds true for biodiversity research.

Given the growing scale and complexity of scientific literature, addressing this documentation gap necessitates scalable, automated solutions for extracting methodological information from unstructured textual data. Traditional manual review is time-consuming, error-prone, and difficult to scale, while earlier automated methods based on rule-based systems or classical NLP often lack generalizability across domains or tasks. At the same time, large language models (LLMs) especially when paired with retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) (Lewis et al., 2020) have shown promise in contextual information extraction and question answering, making them well-suited for such tasks. RAG integrates the power of pre-trained language models with external, domain-specific information sources, in this case, publications, allowing it to retrieve relevant data in real-time and generate more accurate, contextually enriched, and highly relevant responses to any given query.

In this study, we address the following research question: How effectively can open-source large language models, enhanced with retrieval-augmented generation, extract methodological details from unstructured scientific texts, and how do their outputs compare to those of human experts?

To explore this, we propose a scalable, automated pipeline that leverages multiple open-source LLMs within a RAG framework to extract DL methodological details from scientific publications. The pipeline is built around a set of competency questions (CQs) (Grüninger & Fox, 1995) that are general enough to apply to any DL study, yet specific enough to capture fine-grained methodological choices. To enhance consistency, we integrate a voting classifier that aggregates responses across five LLMs Llama-3 70B (Touvron et al., 2023) (https://ai.meta.com/blog/meta-llama-3/), Llama-3.1 70B (https://ai.meta.com/blog/meta-llama-3-1/), Mixtral-8x22B-Instruct-v0.1 (Jiang et al., 2024) (https://mistral.ai/news/mixtral-8x22b/), Mixtral 8x7B (https://mistral.ai/news/mixtral-of-experts/), and Gemma 2 9B (Team et al., 2024a) (https://blog.google/technology/developers/google-gemma-2/).

We evaluate our approach on two datasets: (1) a manually curated set of 100 DL-focused biodiversity articles from our previous work (Ahmed et al., 2024b), and (2) an extended dataset of 364 publications from the Ecological Informatics journal (https://www.sciencedirect.com/journal/ecological-informatics). We take biodiversity publications as a case study due to the growing popularity of DL methods in biodiversity research and the enormous number of publications using DL for various applications in this domain. Given the importance of biodiversity research and the critical need for transparent sharing of DL information in these studies (GPAI, 2022), we chose this field to demonstrate our approach. We assess the quality of extracted answers based on their agreement with human-annotated ground truth, considering not only accuracy but also diversity in responses across models.

This article makes the following key contributions: (1) Multi-LLM information extraction pipeline: We develop a novel pipeline that combines five state-of-the-art, open-source LLMs in a RAG setup, supported by a voting classifier to increase reliability and reduce hallucination in outputs. (2) Domain-specific application and evaluation: We apply this pipeline to biodiversity literature and evaluate its effectiveness using two expert-annotated datasets. Our results show that the pipeline achieves 69.5% agreement with human evaluations across 600 comparisons despite only using textual content, while annotators had access to all modalities. (3) Insights into LLM variability and answer diversity: We analyze how different LLMs interpret and respond to the same queries. Our findings highlight significant variations in responses and underline the importance of aggregating outputs to achieve higher accuracy and consistency. (4) Generalizable framework: While demonstrated on biodiversity publications, our approach is domain-agnostic. The core CQ-driven architecture and LLM-based information extraction pipeline can be extended to other scientific domains, such as health, engineering, or social sciences, where structured methodological understanding is essential.

Our approach can help identify gaps in reporting and ensure that critical information about DL methodologies is accessible, thereby enhancing the transparency and reproducibility of research. This article presents a comprehensive case study on applying multiple LLMs for information retrieval in the context of DL methodologies within biodiversity publications. Through our approach, we aim to contribute to the growing body of research focused on automating information extraction and improving the reproducibility of results in scientific literature. By demonstrating the effectiveness of our pipeline, we hope to pave the way for future research that harnesses advanced AI techniques to further enhance data retrieval and analysis in biodiversity and beyond. Ensuring reproducibility in LLM applications requires a clear, comprehensive methodology that specifies all critical steps, settings, and model configurations. By providing all methodological details transparently, we aim to ensure that our approach can be consistently replicated and applied in future studies, supporting the reliable and reproducible use of LLMs in scientific research.

In the following sections, we provide a detailed description of our study. We start with an overview of the state-of-the-art (“Related Work”). We provide the methodology of our study (“Methods”) We describe the results of our work (“Results”) and provide a detailed evaluation of our results (“Evaluation”). We discuss the implications of our study (“Discussion”). Finally, we summarize the key aspects of our study and provide future directions of our research (“Conclusion”).

Portions of the text throughout the manuscript were previously published as part of a preprint (Kommineni, König-Ries & Samuel, 2024a).

Related work

In this section, we review relevant literature corresponding to the key components of our study: Identifying relevant biodiversity research publications, and automated information retrieval techniques. We contextualize these studies within our research framework and highlight how our approach advances the current state of the art.

Identifying relevant biodiversity research publications: Accurately identifying biodiversity research publications that employ DL methodologies is a foundational step in our information extraction pipeline. Selecting the right set of publications is critical for conducting effective analysis, as it directly impacts the quality and reliability of the extracted methodological insights (Cornford et al., 2021). In the context of biodiversity research, this task is particularly nuanced due to variability in data accessibility, thematic scope, and interdisciplinary overlap. Much of the data pertinent to biodiversity research remains scattered across non-centralized sources such as grey literature, unpublished technical reports, or individual researchers’ datasets. In many cases, key findings are embedded within scientific publications that are not easily discoverable or openly accessible (Costello et al., 2013). Systematic methods are particularly useful in biodiversity informatics, where the heterogeneity of data types and terminologies can hinder automated identification of relevant publications. Several studies have employed machine learning or text classification models to identify relevant documents in scientific corpora (Peng & Lu, 2017). For example, topic modeling and supervised classifiers have been applied to biomedical and environmental literature to improve relevance detection beyond keyword matching. Recent advancements in large language models (LLMs) have opened new possibilities for semantic filtering and relevance classification (Brown et al., 2020). Leveraging LLMs for domain filtering is especially useful when full-text access is available, allowing richer representations of the research context than abstracts or metadata alone (Kommineni et al., 2024).

In our work, we rely on a combination of strategies to curate biodiversity-related literature that involves DL. These include (1) harvesting articles from biodiversity-focused journals and databases; (2) consulting domain experts to compile biodiversity-specific keywords; (3) applying keyword-based filters to large corpora; and (4) using large language models (LLMs) to assess the contextual relevance of publications beyond simple keyword matches. Prior work has shown that simple keyword filters may either be too inclusive (capturing irrelevant studies) or too exclusive (missing relevant ones), particularly when terms are used inconsistently across disciplines (Karimi et al., 2021).

Automated information retrieval techniques: Information retrieval (IR) plays a critical role in accessing relevant data from extensive textual corpora (Schütze, Manning & Raghavan, 2008). Traditional IR systems have evolved from simple keyword matching to more sophisticated models that consider contextual semantics. The advent of transformer-based models has significantly enhanced IR capabilities, enabling more nuanced understanding and retrieval of information (Vaswani et al., 2017). Inspired by these advancements, our study employs RAG techniques to enhance the extraction of DL methodologies from biodiversity publications, leveraging the strengths of both retrieval and generation paradigms.

The emergence of LLMs has introduced new possibilities for automatically extracting and synthesizing information from text (Zhu et al., 2023), which can be particularly useful for addressing the gaps in methodological reporting. LLMs, such as GPT-3 (Brown et al., 2020) and its successors (OpenAI et al., 2023; Touvron et al., 2023; Team et al., 2024b), have demonstrated remarkable abilities in natural language understanding and generation, enabling tasks like summarization, question-answering, and information retrieval from vast textual datasets. Recent studies, including those by Lewis et al. (2020) on RAG, have explored how combining LLMs with retrieval mechanisms can enhance the extraction of relevant information from large corpora, offering a promising solution for improving the accessibility of methodological details in scientific literature. In this study, we build on these developments by employing a multi-LLM and RAG-based pipeline to retrieve and categorize DL-related methodological details from scientific articles systematically.

While the application of LLMs for methodological extraction remains underexplored, several tools and approaches have been developed for automating information extraction (Beltagy, Lo & Cohan, 2019; Lozano et al., 2023; Dunn et al., 2022; Dagdelen et al., 2024). Tools like SciBERT (Beltagy, Lo & Cohan, 2019) and other domain-specific BERT models have been used to extract structured information from unstructured text, yet their application has primarily been focused on citation analysis, abstract summarization, or specific biomedical applications. Bhaskar & Stodden (2024) introduced “ReproScreener,” a tool for evaluating computational reproducibility in machine learning pipelines, which uses LLMs to assess methodological consistency. Similarly, Gougherty & Clipp (2024) tested an LLM-based approach for extracting ecological information, demonstrating the potential of LLMs to improve metadata reporting and transparency. These studies underscore the need for versatile, automated methodologies capable of handling DL pipeline documentation across various fields.

While existing studies have addressed individual components pertinent to our research such as information retrieval, LLM output processing, and ensemble methods but there remains a gap in integrating these elements into a cohesive framework tailored for extracting DL methodologies from biodiversity literature. Our approach distinguishes itself by systematically combining automated publication selection, competency question formulation, RAG-enhanced information retrieval, LLM output processing, and a voting classifier mechanism. This integrated pipeline not only streamlines the extraction process but also enhances the accuracy and reliability of the extracted methodological details, thereby advancing the current state of the art in this domain.

In summary, our work builds upon and extends existing research by integrating multiple advanced techniques into a unified framework aimed at improving the extraction of DL methodologies from biodiversity publications. This holistic approach addresses existing challenges and contributes to the broader goal of enhancing transparency and reproducibility in DL research within the biodiversity domain.

Materials and Methods

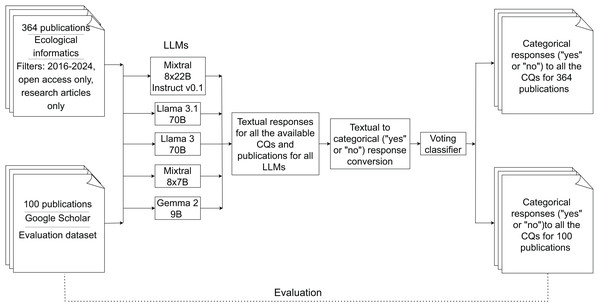

In this section, we provide detailed information about the pipeline employed (Fig. 1) to extract and analyse the information from the selected biodiversity-related publications.

Figure 1: Workflow of the pipeline.

The solid arrows represent the main process flow, while the dotted line indicates the evaluation phase for the categorical responses from 100 publications retrieved from our previous research (Ahmed et al., 2024a).Dataset

Our work is based on two datasets. The first one originates from our previous research (Ahmed et al., 2024a), while the second is sourced from the Ecological Informatics Journal. Each dataset was indexed using different methodologies, contributing to a diverse representation of information. This variation arises from the range of journals included in the first dataset and the specific selection criteria applied in the second.

Dataset from prior research

In our previous study (Ahmed et al., 2024b), we used a modified version of the keywords from previous research (Abdelmageed et al., 2022) to query Google Scholar and indexed over 8,000 results. From this, the authors narrowed down the selection to 100 publications, excluding conference abstracts, theses, books, summaries, and preprints. Later, the first and second authors of that work manually extracted deep-learning information on ten variables (Dataset, Source Code, Open source frameworks or environment, Model architecture, Software and Hardware Specification, Methods, Hyperparameters, Randomness, Averaging result and Evaluation metrics) from the biodiversity publications, recording each as a categorical value: “yes” if the information was present and “no” if it was absent. In the current study, these 100 publications (https://github.com/fusion-jena/Reproduce-DLmethods-Biodiv/blob/main/Final_data.csv) serve as an evaluation dataset, supporting the comparison and validation of our findings.

Dataset from ecological informatics journal

To index DL-related publications from the Ecological Informatics journal, we first identified relevant keywords and used them to guide the indexing of publications.

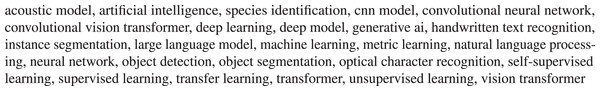

Keywords selection: Related keywords are crucial for automatically indexing DL-related publications from a journal. To identify these relevant deep-learning keywords, we downloaded AI-related session abstracts from the Biodiversity Information Standards (TDWG) conferences (https://www.tdwg.org/) held in 2018 (Pando et al., 2018), 2019 (Frandsen et al., 2019), and 2021–2023 (Groom & Ellwood, 2021; Kommineni, Groom & Panda, 2022; Johaadien, Lewers & Torma, 2023) (no AI session was available for 2020). We then used an open-source large language model (Mixtral 8x22b Instruct-v0.1) to extract all deep-learning-related keywords from each abstract. The query in the prompt template (Box 1) for extracting DL keywords from the given context is “your task is to extract the deep learning related keywords from the provided context for the literature survey”.

The LLM extracted a total of 248 keywords from 44 abstracts, averaging approximately 5.6 keywords per abstract (https://github.com/fusion-jena/information-retrieval-using-multiple-LLM-and-RAG/tree/main/Data/TDWG_abstracts). Since each abstract was treated individually during keyword extraction, the LLM indexed the same keywords multiple times, leading to redundancy and non-qualitative keywords. To improve keyword quality, we prompted the same LLM again with the full list, instructing it to eliminate redundancies and non-deep-learning-related terms. This refinement reduced the list from 248 to 123 keywords. Finally, a domain expert further curated this list down to 25 keywords (Fig. 2) by removing abbreviations and redundant terms, ensuring accurate indexing from the journal.

Figure 2: LLM-Human optimized 25 DL-related keywords from 44 AI-related session abstracts at the Biodiversity Information Standards (TDWG) conferences.

Publication citation data extraction: Using the 25 refined keywords identified from TDWG abstracts with the assistance of both the LLM and domain experts, we queried the Ecological Informatics journal. The query applied the following filters: publication years from 2016 to August 1, 2024, article type as research articles, and open-access availability. Due to the platform’s limit of eight boolean connectors per search, the keywords were divided into five sets, each connected with the boolean operator OR (e.g., “Keyword 1” OR “Keyword 2” OR “Keyword 3” OR “Keyword 4” OR “Keyword 5”). Citation data from each search was manually exported in BibTeX format. In total, 991 citation records were indexed, and after removing duplicates based on DOIs, 364 unique publications were identified (https://github.com/fusion-jena/information-retrieval-using-multiple-LLM-and-RAG/tree/main/Data/Metadata_open_access).

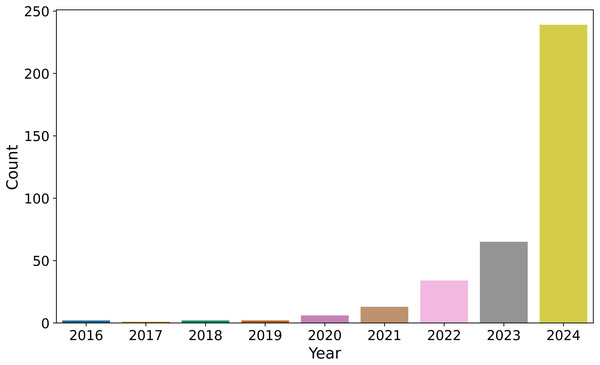

The bar plot (Fig. 3) illustrates the annual distribution of these 364 publications from Ecological Informatics. The trend shows a consistent increase in publication frequency up to 2023, with 65 data points recorded for that year. In 2024, there is a significant rise to 239 data points, representing a fourfold increase compared to 2023.

Figure 3: Number of publications selected from Ecological Informatics Journal (364 publications).

Full-text publication download: Using the DOIs of the 364 unique publications, we retrieved the full-text PDFs through the Elsevier Application Programming Interface (API). These PDFs were subsequently used as input for the selected LLMs.

Datasets diversity

The complete dataset comprises 464 publications, 100 of which were sourced from previous research (Ahmed et al., 2024a), and 364 from the Ecological Informatics journal. The first part of the dataset (comprising 100 publications) is highly diverse. These publications were identified using a set of 10 biodiversity-related keywords and one deep-learning keyword across 22 different publishers. The second part, which consists of publications from Ecological Informatics, was curated using 25 DL-related keywords. This broad keyword selection ensures the inclusion of a wide range of topics without focusing on a single subfield, such as image classification. As a result, the entire dataset is not only diverse in terms of its coverage of various biodiversity subtopics, but also in its methodological approaches, keywords, and journal sources.

Competency questions

We employed competency questions (CQs) to retrieve specific DL methodological information from selected biodiversity publications. Competency questions are natural language questions that users seek answers to and are essential for defining an ontology’s scope, purpose, and requirements (Grüninger & Fox, 1995). In our previous work (Kommineni, König-Ries & Samuel, 2024b), two domain experts formulated 28 CQs to cover every aspect of the DL pipeline for retrieving information from the provided context. For this study, we applied the same set of 28 CQs with multiple LLMs to extract relevant DL information from a total of 464 biodiversity-related publications (364 from Ecological Informatics journal and 100 from previous research).

Information retrieval

Recently, the RAG approach has rapidly been used for information retrieval from both structured and unstructured data. This method leverages LLM text generation to extract information from authoritative sources, such as biodiversity publications in our case. In this work, we employed five LLMs from two providers, namely hugging face Mixtral 8x22B Instruct v0.1 (https://huggingface.co/mistralai/Mixtral-8x22B-Instruct-v0.1) and Groq’s (https://console.groq.com/docs/models) Llama 3.1 70B, Llama 3 70B, Mixtral 8x7B and Gemma 2 9B with temperature set to 0 for all models. The Mixtral 8x22B Instruct v0.1 model was run on a custom Graphics Processing Unit (GPU), while the Groq models were accessed through their API, where a custom GPU is not required. These specific LLMs were selected because they are open-source and represent the state-of-the-art language models available when we began working on our pipeline.

Information retrieval using LLMs and RAG was also a component of our previous work pipeline (Kommineni, König-Ries & Samuel, 2024b), where we aimed to build a semi-automated construction of the Knowledge Graph (KG) pipeline (we refer to the definition of KG from Hogan et al. (2021). This approach allowed us to extract, organize, and link information from unstructured text into structured, queryable data within the KG framework. By semi-automating the construction of KGs, we streamlined the process of mapping complex domain knowledge, which is crucial for advancing research in areas that require high levels of detail, such as biodiversity and DL methodologies. In this work, we build on our previous information retrieval component (then CQ Answering) by limiting the retrieval tokens to 1,200, chunk size to 1,000 and overlap to 50 chunks. Additionally, we specified that the responses should be concise and limited to fewer than 400 words to enhance the clarity and focus of the responses. For each selected LLM, the CQs and biodiversity-related publications were provided as input, and the RAG-assisted LLM pipeline generated answers to all CQ-publication combinations in textual sentence format as output.

Preprocessing LLM outputs

After the information retrieval process, we obtained answers to the CQ for each combination of LLM, CQ, and publication. Some of these responses contained unnecessary structured information. To streamline the outputs, we preprocessed the responses using a Python script, removing strings like “Helpful Answer::” and “Answer::” to eliminate unnecessary content. We indexed only the information following these strings for the Mixtral 8x22B Instruct v0.1 model, as that portion contained details relevant to the queries and selected context.

Next, we converted all preprocessed LLM textual responses into categorical “yes” or “no” answers. To achieve this, we prompted the same LLMs that generated the CQ answers to provide categorical responses for each question-answer pair. To guide this process, a couple of in-context examples are provided in the prompt (Box 2) as references for the LLM. The conversion to categorical responses is determined by whether the generated responses include the essential information required, rather than simply assessing if the query was answered in general. This approach prioritizes the presence of specific, relevant details in the response, ensuring that the information provided meets the core needs of the query. This conversion from textual to categorical responses will later facilitate the evaluation of our pipeline.

Assessment metrics

All key outputs generated by the LLMs, including the CQ answers and the conversion of textual responses to categorical values (“yes” or “no”), were manually evaluated. For assessing the CQ answers, we relied on our previous work (Kommineni, König-Ries & Samuel, 2024b), in which we manually evaluated 30 publications from the evaluation dataset (https://github.com/fusion-jena/automatic-KG-creation-with-LLM/tree/master/Evaluation/CQ_answers).

Inter-Annotator Agreement (IAA) score: To evaluate the categorical responses (“yes” or “no”) produced by the LLMs, we randomly selected 30 publications, used those for each LLM, and manually annotated the ground truth data by assessing the question-answer pairs generated by the RAG-assisted LLM pipeline. We then compared the inter-annotator agreement between the LLM-generated and manually annotated answers using Cohen’s kappa score (https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/generated/sklearn.metrics.cohen_kappa_score.html). This annotation process was conducted by the first and last authors of this article.

Voting classifier: Since we leveraged multiple LLMs to retrieve the DL-related information and processed that information to categorical values, it became feasible to build a voting classifier. We employed a hard voting methodology, where each of the five instances (derived from five LLMs) produced possible outcomes of “yes” or “no” for each combination of CQ and publication. The voting classifier made decisions based on the majority of votes, which enhances the overall quality of the results.

Semantic similarity between five LLM outputs: As mentioned before, we have five answers for each combination of CQ and publication, one from each LLM formatted in both textual and categorical forms. We used these five textual answers to compute the cosine similarity matrix (https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/generated/sklearn.metrics.pairwise.cosine_similarity.html). With this matrix, average cosine similarities for all the responses between all the LLM combinations were calculated. Additionally, we assessed the inter-annotator agreement among the categorical responses using Cohen’s kappa score for all possible combinations.

Computing infrastructure

We have used 1xNVIDIA H100 (94 GB), 2xNVIDIA A100 (80 GB) and Intel Xeon Platinum 9242 to execute different parts of the pipeline (Table 1).

| LLM name | Hardware | RAG textual responses | Conversion of textual to categorical responses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mixtral 8x22B Instruct v0.1 | NVIDIA H100 (94 GB) | 71 h 3 min | 6 h 34 min |

| NVIDIA A100 (2x80 GB) | 69 h 10 min | – | |

| Mixtral 8x7B | Intel Xeon Platinum 9242 | 63 h 32 min | 40 h 39 min |

| Llama 3.1 70B | Intel Xeon Platinum 9242 | 5 h 52 min | 9 h 31 min |

| Llama 3 70B | Intel Xeon Platinum 9242 | 38 h 36 min | 22 h 28 min |

| Gemma 2 9B | Intel Xeon Platinum 9242 | 16 h 2 min | 8 h 49 min |

Additional analysis

Publication filtering: Our pipeline was driven by the DL-related keywords, which means that our dataset may include publications that mention these keywords without actually detailing a DL pipeline. To investigate this assumption as an addition to our current pipeline, we filtered the publications by using a RAG-assisted LLM pipeline (https://github.com/fusion-jena/information-retrieval-using-multiple-LLM-and-RAG/blob/main/Prompts/DL_pipeline.txt) (Llama 3.1 70B) to identify if any publications that contained only DL-related keywords, rather than discussing a DL pipeline. This filtering pipeline will output a response of “yes” or “no”. A response of “yes” indicates that the publication includes a DL methodology, while “no” indicates the absence of such a methodology. These categorical responses then be used to filter publications accordingly. To evaluate the LLM’s judgement, we compared its findings with 100 articles from our previous work (Ahmed et al., 2024a), where all the publications were focused on DL methods. Furthermore, we also compared the outputs of all the publications with those of filtered publications.

Time logs: Computational tasks inherently rely on physical resources, and there is a growing awareness of the substantial environmental footprint associated with both the production and use of these resources (Samuel & Mietchen, 2024). In the context of our work, which leverages information retrieval workflows involving DL methodologies in biodiversity research, one of our aims is to evaluate and quantify the environmental impact of these computational processes. In this pipeline, we recorded the time taken to process all the requests for each document. We preprocessed the time logs by considering the last instance while removing the duplicates based on the unique identifiers of the log file. These time records are essential for calculating the environmental footprint (Lannelongue et al., 2021; Lannelongue, Grealey & Inouye, 2021) of the pipeline. By assessing the energy and resource consumption of our DL-driven information retrieval pipeline, we hope to contribute to more sustainable practices in biodiversity informatics and computational research more broadly.

Environmental footprint: Although our pipeline recorded processing times for each publication and each combination of CQ and publication, we only utilized the logged times for each publication for two key components of the pipeline (Table 1): 1. RAG answers and 2. Conversion of RAG textual responses to categorical responses. To estimate the environmental footprint, we used the website (http://calculator.green-algorithms.org/) (Lannelongue, Grealey & Inouye, 2021), which requires input on hardware configuration, total runtime, and location to estimate the environmental footprint of our computations. Our calculation only accounts for the pipeline components mentioned above and the hardware components from our side, excluding the hardware components from Groq. Our pipeline consumed 177.55 kWh of energy to generate the RAG textual responses, resulting in a carbon footprint of 60.14 kg Carbon Dioxide Equivalent (CO2e), which is equivalent to the carbon offset of 64.65 tree months. For converting textual to categorical responses, the pipeline consumed 50.63 kWh of energy, corresponding to a carbon footprint of 17.15 kg CO2e and 18.7 tree months. For the environmental footprint estimates, we selected Germany as the location and assumed that we used the total number of cores in the Intel Xeon Platinum 9242 processor (which is 48 cores).

Replication details

To ensure the reproducibility of our approach, we provide details on the hyperparameters, computational resources, and training configurations used in our experiments.

Hyperparameters: Since our study primarily focuses on retrieving and extracting information using LLMs, we did not fine-tune any models. Instead, we utilized the models in their pre-trained state with prompt-based querying. However, the following inference parameters were set for all LLMs used: Temperature: 0, Retrieval tokens: 1,200, Chunk size: 1,000, Chunk overlap: 50.

Computational resources: Our experiments were conducted on a high-performance computing (HPC) cluster with the following specifications: GPU: 1xNVIDIA H100 (94 GB), 2xNVIDIA A100 (80 GB) and Intel Xeon Platinum 9242 (Table 1).

Training configurations: We used the default setting for groq models and four-bit precision to reduce memory consumption and speed up computations for hugging face models.

Results

This section presents the results from each part of the pipeline. We queried 28 CQs (Kommineni, König-Ries & Samuel, 2024b) across 464 publications for each LLM, resulting in a total of 12,992 textual answers. Overall, we obtained 64,960 textual responses from the five selected LLMs. These textual responses were then converted into categorical “yes” or “no” responses using the respective LLMs.

To evaluate the LLM’s judgements in these conversions, we compared the categorical responses against human-annotated ground truth data from 30 randomly selected publications. We used those randomly selected 30 publications for each LLM, leading to 840 comparisons per LLM (30 publications 28 CQs). This resulted in 4,200 comparisons for five LLMs, with 3,566 agreements between the LLM responses and the human-annotated ground truth responses, achieving a maximum agreement of 752 out of 840 for the Llama 3 70B model (Table 2).

| LLM name | Agreements between LLM and human response | Cohen’s kappa score (IAA) |

|---|---|---|

| Mixtral 8x22B Instruct v0.1 | 667/840 | 0.5711 |

| Mixtral 8x7B | 666/840 | 0.5583 |

| Llama 3.1 70B | 735/840 | 0.7221 |

| Llama 3 70B | 752/840 | 0.7708 |

| Gemma 2 9B | 746/840 | 0.7128 |

The highest inter-annotator agreement between the LLM responses and human annotations was 0.7708, achieved with the Llama 3 70B model. This score reflects a strong level of agreement, as Scikit-learn’s Cohen’s Kappa score ranges from −1 (indicating no agreement) to +1 (indicating complete agreement) (Table 2). As mentioned in the dataset subsection, we used a dataset from our previous work (Ahmed et al., 2024a), consisting of 100 publications, to evaluate our pipeline. We compared the manually annotated responses from that study (Ahmed et al., 2024a) with the results generated by the voting classifier. Six DL reproducibility variables are both common to this work and the prior study, allowing us to analyze six CQs across 100 publications, which resulted in a total of 600 comparisons.

There are 417 agreements between the human annotators from the previous work (Ahmed et al., 2024a) and the voting classifier results. Table 3 shows the number of agreements and other metrics (accuracy, precision, recall and F1-score) between the human annotators and the voting classifier for each reproducibility variable. The DL variable Model architecture has the highest agreement, with 89 agreements, while Open source framework has the lowest, with 53 agreements. The Precision and F1-score is highest for the variable Model architecture and lowest for the Source code. The Recall is highest for the variables Source code and Open source framework. For statistical significance, we calculated the Chi-Square Test of Independence (https://docs.scipy.org/doc/scipy/reference/generated/scipy.stats.chi2_contingency.html). P-value for dataset, source code, open source framework and hyperparameters are less than 0.05, which means, we need to reject the null hypothesis and conclude that there is a statistically significant difference between the human annotators and the voting classifier. The accuracy, precision, recall and F1-score were calculated using Scikit learn (https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/model_evaluation.html). Table 3 also shows the mapping of CQs from this pipeline to the reproducibility variables of the previous work (Ahmed et al., 2024b).

| CQ number | Deep learning variable from Ahmed et al. (2024b) | Agreements between human response and voting classifier | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-score | Chi-square statistic | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | Dataset | 63/100 | 0.63 | 0.78 | 0.60 | 0.68 | 6.3297 | 0.0119 |

| 10 | Source code | 74/100 | 0.74 | 0.13 | 1.00 | 0.24 | 6.5600 | 0.0104 |

| 12 | Model architecture | 89/100 | 0.89 | 0.92 | 0.97 | 0.94 | 0.0623 | 0.8029 |

| 13 | Hyperparameters | 63/100 | 0.63 | 0.56 | 0.93 | 0.70 | 11.3945 | 0.0007 |

| 19 | Open source framework | 53/100 | 0.53 | 0.47 | 1.00 | 0.64 | 7.6479 | 0.0057 |

| 22 | Metrics availability | 75/100 | 0.75 | 0.85 | 0.86 | 0.85 | 0.0058 | 0.9391 |

Note:

The boldfaced values correspond to the maximum results in each comparison group (column).

| CQ Nr. | CQ | Number of publications that provide CQ info | Number of publications that provide CQ info after filtering the publications that do not contain DL in the study |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | What methods are utilized for collecting raw data in the deep learning pipeline (e.g., surveys, sensors, public datasets)? | 215/464 | 109/257 |

| 2 | What data formats are used in the deep learning pipeline (e.g., image, audio, video, CSV)? | 333/464 | 232/257 |

| 3 | What are the data annotation techniques used in the deep learning pipeline (e.g., bounding box annotation, instance segmentation)? | 61/464 | 55/257 |

| 4 | What are the data augmentation techniques applied in the deep learning pipeline (e.g., Flipping, Rotating, Scaling)? | 76/464 | 69/257 |

| 5 | What are the datasets used in the deep learning pipeline (e.g., MNIST, CIFAR, ImageNet)? | 152/464 | 134/257 |

| 6 | What preprocessing steps are involved before training a deep learning model (e.g., normalization, scaling, cleaning)? | 145/464 | 92/257 |

| 7 | What are the criteria used to split the data for deep learning model training (e.g., train, test, validation)? | 141/464 | 102/257 |

| 8 | Where is the code repository of the deep learning pipeline available (e.g., GitHub, GitLab, BitBucket)? | 23/464 | 18/257 |

| 9 | Where is the data repository of the deep learning pipeline available (e.g., Zenodo, Figshare, Dryad, GBIF)? | 27/464 | 16/257 |

| 10 | What is the code repository link of the deep learning pipeline (e.g., Link to GitHub, GitLab, BitBucket)? | 20/464 | 17/257 |

| 11 | What is the data repository link of the deep learning pipeline (e.g., Link to Zenodo, Figshare, Dryad, GBIF)? | 18/464 | 12/257 |

| 12 | What type of deep learning model is used in the pipeline (e.g., CNN, RNN, Transformer)? | 275/464 | 235/257 |

| 13 | What are the hyperparameters used in the deep learning model (e.g., learning rate, optimizer)? | 124/464 | 104/257 |

| 14 | How are the hyperparameters of the model optimized (e.g., grid search, random search)? | 76/464 | 37/257 |

| 15 | What optimization techniques are applied in the deep learning pipeline (e.g., SGD, Adam)? | 122/464 | 111/257 |

| 16 | What criteria are used to determine when training is complete (e.g., validation loss plateau)? | 75/464 | 64/257 |

| 17 | What are the regularization methods used to prevent overfitting in the deep learning pipeline (e.g., dropout, L2 regularization)? | 101/464 | 85/257 |

| 18 | What is the strategy implemented to monitor the model performance during training? | 205/464 | 129/257 |

| 19 | Which frameworks are used to build the deep learning model (e.g., TensorFlow, PyTorch)? | 101/464 | 94/257 |

| 20 | Which hardware resources are used for training the deep learning model (e.g., GPUs, TPUs)? | 101/464 | 95/257 |

| 21 | What are the postprocessing steps involved after the model training (e.g., Saliency maps, Metrics calculation, Confusion matrix)? | 131/464 | 80/257 |

| 22 | What metrics are used to evaluate the performance of the deep learning model (e.g., accuracy, precision, recall)? | 340/464 | 225/257 |

| 23 | What measures were taken to ensure the generalizability of the deep learning model (e.g., Diverse dataset, cross-validation, Stratified splitting)? | 174/464 | 115/257 |

| 24 | What strategies are employed to handle randomness in the deep learning pipeline (e.g., random seed value)? | 60/464 | 42/257 |

| 25 | What is the purpose of the deep learning model (e.g., classification, segmentation, detection)? | 345/464 | 247/257 |

| 26 | What techniques are used to address data bias during preprocessing of the deep learning pipeline (e.g., Stratified splitting, oversampling, undersampling, Diverse data collection)? | 59/464 | 41/257 |

| 27 | What process was followed to deploy the trained deep learning model (e.g., Model serialization, Platform selection)? | 7/464 | 6/257 |

| 28 | Which platform was used to deploy the deep learning model (e.g., AWS, Azure, Google Cloud platform)? | 17/464 | 8/257 |

| – | Total for all queries | 3,524/12,992 | 2,574/7,196 |

Note:

The boldfaced values correspond to the maximum results in each comparison group (column).

This serves as a proof of concept for validating the voting classifier for the remaining 364 publications (Table 3). In this context, we calculated the voting classifier decisions for all 464 publications. After filtering out those publications that do not include a DL pipeline in their research, only 257 publications remained from the initial analysis (Table 4).

Table 4 shows that CQ 25 (purpose of the deep learning model) is the most frequently mentioned, appearing in 345 publications. In contrast, CQ 27 (process to deploy the trained deep learning model) is the least frequently mentioned. Following the filtering process, CQ 25 with 247 mentions, and CQ 27 with six mentions retain their positions as the most and least mentioned variables, respectively, among the 257 publications. With the current pipeline, 3,524 queries were answered out of a total of 12,992 total queries. After filtering the publications, 2,574 queries were answered out of 7,196 total queries.

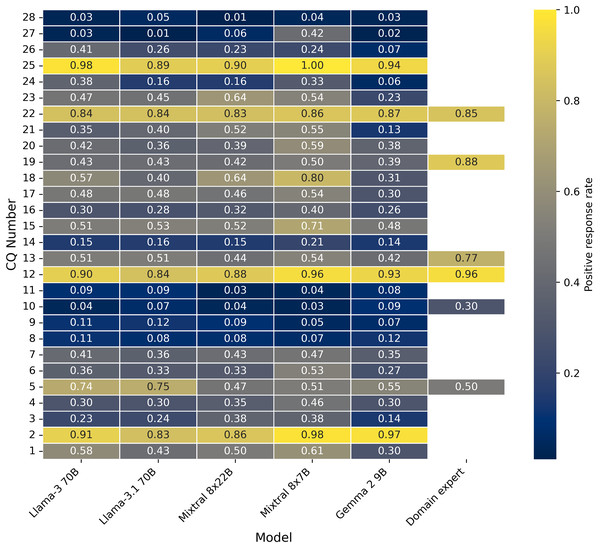

Figure 4 and Table A1 provide the average positive response rate for 100 publications, which is an evaluation dataset from our previous work (Ahmed et al., 2024b) for all the five LLMs and then compared the positive response rates with human responses where ever the data is available. The human annotator positive response rate is highest for CQ 12 (type of deep learning model is used in the pipeline), which is also in line with all LLM responses. Consistently, CQ 27 and 28 show very low positive responses across all LLM responses. This positive rate information will showcase the quantitative variability of all LLM responses and also with human responses wherever the data is available. Table A2 provides more insights into the total number of 464 publications about the positive response before and after publications.

Figure 4: Positive response rate between all the CQs and LLMs, human experts (Evaluation data set).

Table A3 shows agreements between human responses and each LLM response, including the voting classifier. Across all the LLMs, including the voting classifier, the variable Model architecture has the highest agreements and Open source framework has the lowest agreements.

Additionally, we also computed the average cosine similarity scores for the RAG-assisted pipeline textual responses between different combinations of LLMs. This allows us to identify which LLM pairs provide similar outputs and assess whether different LLMs are generating comparable results. Table 5 shows that the Llama 3.1 70B–Llama 3 70B pair have the most similar answers, while Gemma 2 9B–Mixtral 8x22B Instruct v0.1 have the least similar answers before filtering. After filtering, the same LLM pairs perform in the same direction.

| LLM pair | Cosine similarity score for all publications | Cosine similarity score after the removal of non-deep learning publications |

|---|---|---|

| Gemma 2 9B–Llama 3.1 70B | 0.4619 | 0.4857 |

| Gemma 2 9B–Llama 3 70B | 0.4773 | 0.5022 |

| Gemma 2 9B–Mixtral 8x7B | 0.4201 | 0.4327 |

| Gemma 2 9B–Mixtral 8x22B Instruct v0.1 | 0.3989 | 0.4128 |

| Llama 3.1 70B–Llama 3 70B | 0.6854 | 0.6958 |

| Llama 3.1 70B–Mixtral 8x7B | 0.5232 | 0.5385 |

| Llama 3.1 70B–Mixtral 8x22B Instruct v0.1 | 0.4759 | 0.4959 |

| Llama 3 70B–Mixtral 8x7B | 0.5374 | 0.5505 |

| Llama 3 70B–Mixtral 8x22B Instruct v0.1 | 0.4901 | 0.5064 |

| Mixtral 8x7B–Mixtral 8x22B Instruct v0.1 | 0.4995 | 0.5035 |

Furthermore, the IAA scores were calculated for the categorical responses, which were generated from textual responses using LLMs for all the model combinations. The IAA score calculated using Scikit-learn Cohen’s Kappa score ranges from −1 (no agreement) to +1 (complete agreement). All calculated IAA scores range between 0.5321 and 0.7928, both inclusive, indicating moderate to strong agreement among all LLM pairs. Before the publication filtering, the Llama 3.1 70B–Llama 3 70B combination exhibits the maximum IAA score of 0.7924, while the Gemma 2 9B–Mixtral 8x7B combination has the minimum IAA score of 0.5321. After the filtering process, these same LLM pairs showed maximum and minimum IAA scores of 0.7928 and 0.5644 respectively (Table 6).

| LLM pair | Inter-annotator agreement score for all publications | Inter-annotator agreement score after the removal of non-deep learning publications |

|---|---|---|

| Gemma 2 9B–Llama 3.1 70B | 0.6945 | 0.7445 |

| Gemma 2 9B–Llama 3 70B | 0.6853 | 0.7312 |

| Gemma 2 9B–Mixtral 8x7B | 0.5321 | 0.5644 |

| Gemma 2 9B–Mixtral 8x22B Instruct v0.1 | 0.6354 | 0.6937 |

| Llama 3.1 70B–Llama 3 70B | 0.7924 | 0.7928 |

| Llama 3.1 70B–Mixtral 8x7B | 0.5533 | 0.5784 |

| Llama 3.1 70B–Mixtral 8x22B Instruct v0.1 | 0.6770 | 0.7184 |

| Llama 3 70B–Mixtral 8x7B | 0.5705 | 0.5958 |

| Llama 3 70B–Mixtral 8x22B Instruct v0.1 | 0.6901 | 0.7306 |

| Mixtral 8x7B–Mixtral 8x22B Instruct v0.1 | 0.5581 | 0.5992 |

Discussion

Manually extracting DL-related information from scientific articles is both labour-intensive and time-consuming. Current approaches that rely on manual retrieval often vary significantly based on the annotator’s perspective, which can differ from one annotator to another due to task interpretation and the annotators’ domain knowledge (Ahmed et al., 2024b). This variability can lead to inconsistencies and raises significant concerns regarding the reproducibility of manually annotated data.

To address these challenges, this work proposes an automated approach for retrieving information from scientific articles by employing five different LLMs. This strategy aims to improve both the accuracy and diversity of information extraction. By utilizing multiple LLMs, our pipeline is positioned to capture a broader range of variable-level information related to DL methodologies in scientific publications.

In this current pipeline, there are three critical components: 1. Identifying relevant research publications 2. Automatically extracting relevant information from publications for the desired queries, and 3. Converting the extracted textual responses into categorical responses. For the first component, we choose a method that extracts publications based on selected keywords. These keywords were derived from AI-related abstracts presented at the Biodiversity Information Standards (TDWG) conference, resulting in a total of 25 keywords. It is important to note that even if a publication mentions any of the keywords only once, without providing the actual DL methodology, it will still be included in the extraction process. As a result, our pipeline queries these publications, which may yield a higher number of negative responses, indicating that the context does not contain relevant information to answer the queries.

To mitigate this issue, we filtered the extracted publications again using the RAG-assisted pipeline. As a result, of this filtering, the number of publications decreased by 44.6%, leaving us with 257 publications. This process was also evaluated using 100 publications from previous work (Ahmed et al., 2024a), all of which included DL methodologies in the study, and it achieved an accuracy of 93%. Before filtering, our pipeline only provided positive responses to 27.12% of the total queries (3,524 out of 12,992). After implementing the filtering step, the percentage of positive responses increased to 35.77% (2,574 out of 7,196). This represents an improvement of 8.65% in the positive response rate, which is a significant gain. However, after filtering, 64.23% of the queries still did not yield available information in the publications. This gap can be attributed to the complexity of the queries (CQs), which cover all aspects of the DL pipeline, from data acquisition to model deployment.

In practice, not all studies utilize techniques like data augmentation; some prefer to use readily available datasets, thus bypassing the formal requirement for data annotation steps. Moreover, certain studies may not address model deployment at all. As a result, it is uncommon for publications to provide details on aspects such as deployment status, model randomness, generalizability, and other related factors. Consequently, the positive response rate for the queries tends to be relatively low.

The publication filtering process can be applied either during the data processing stage of the pipeline or after the pipeline execution. We chose the latter approach, as it offers more insightful comparisons between the results before and after filtering. As demonstrated in the previous text, the filtering step significantly improved the positive response rate: before filtering, only 27.12% of queries returned positive results, while after filtering, this rate increased to 35.77%, representing an 8.65% improvement.

To address the second component, we employed an RAG-assisted LLM pipeline to extract relevant information from the publications for all our queries (CQs). This component generated a total of 12,992 textual responses for each combination of queries (CQs) and publications across the different LLMs. The textual responses were initially preprocessed, and we calculated the average cosine similarity between the generated responses by different LLMs. The average cosine similarity score was high for the Llama 3.1 70B–Llama 3 70B model pair, indicating that these models generated similar outputs. On the other hand, the Gemma 2 9B–Mixtral 8x22B Instruct v0.1 model pair exhibited a lower average cosine similarity score, suggesting more significant variability in their response generation. Even after filtering the publications, the trend in the similarity scores remained consistent for these two model pairs, indicating that the response generation was not significantly affected by the exclusion of publications that did not utilize DL methods in their studies.

The third crucial component of our pipeline involves converting the extracted textual responses into categorical responses. This transformation simplifies the evaluation process, making it easier to compare the outputs generated by the LLM with human-extracted outputs from previous work (Ahmed et al., 2024a). Additionally, it facilitates the creation of an ensemble voting classifier. Two annotators reviewed the different question-answer pairs generated by the LLM and provided their assessments to ensure effective conversion from textual to categorical responses. The IAA scores between the human-annotated and LLM responses indicated that the highest levels of agreement were observed for the Llama 3 70B, Llama 3.1 70B, and Gemma 2 9B models in descending order, which generated straight forward answers that were easy for human annotators to evaluate. In contrast, the Mixtral 8x22B Instruct v0.1 and Mixtral 8x7B models exhibited the lowest IAA scores, reflecting only moderate agreement. The generated responses from these models were often ambiguous, combining actual answers with generalized or hallucinated content, which made it challenging for annotators to make precise judgments.

We also calculated the IAA scores for the categorical responses generated by different LLM pairs to evaluate the level of agreement among them. Overall, we observed a moderate to strong agreement between the various LLMs. However, following the publication filtering process, the IAA scores improved for all LLM pairs, indicating that the quality of the generated responses enhanced after the filtering.

The categorical responses have powered the ensemble approach of the voting classifier. We compared and calculated the metrics between the categorical values from the voting classifier and the manually annotated values from our previous work for six deep-learning variables. This comparison revealed that the agreement between the LLM and human annotations is particularly low for the datasets, open-source frameworks, and hyperparameters. The accuracy, precision and F1-score are high for the variable Model architecture, which suggests that the information is clearly mentioned in most of the publications and extracting this information is easier using automated methods. The precision is particularly low for the variables Source code and Open source framework while the recall is cent for the same variables (Table 3). This means that our pipeline is predicting all the positive cases correctly and also predicting many negative labels as positive cases. Particularly with the variable Source code, the pipeline is hallucinating the new GitHub links or combining multiple GitHub links from the same article. In the manual annotations, the authors from the previous work (Ahmed et al., 2024a) also considered the accompanying code, which could explain the low agreement regarding open-source frameworks and hyperparameters. For datasets, the authors from the previous work (Ahmed et al., 2024a) considered dataset availability only when persistent identifiers were provided in the respective studies. In contrast, the LLM also considers the dataset name itself, even when persistent identifiers are not mentioned.

Our approach incorporates a variety of LLMs, each with distinct parameters, ensuring that the voting classifier considers diverse perspectives generated by different models for the same query. By ensembling the outputs of these varied models, the voting classifier enhances its robustness in making final decisions. This method not only enriches the decision-making process but also improves the classifier’s overall reliability.

There is a lot of variability in generating positive responses for each model (Table A1 and Fig. 4) and also a significant difference between the accuracies of each LLM and the human responses (Table A3). All these variability suggests that each model predicts the outputs differently, and our voting classifier aggregates the strengths of these multiple models to achieve better accuracy. The Chi-square p-value less than 0.05 confirms that our voting classifier has a meaningful relationship with the human responses, and their performance is statistically significant.

Our pipeline is applicable to any unstructured data corpus where reporting and analysis of methodological details are required. While we have tested the pipeline on biodiversity publications, the pipeline’s core is based on CQs to extract and analyze information from unstructured data. The CQs used in our pipeline are designed to be highly generalized for DL methodologies, making it adaptable to any domain for obtaining precise information on DL techniques. Moreover, since CQs drive the pipeline, it is possible to customize these queries to focus on specific methodologies or domains of interest.

A key limitation of the current pipeline is that it utilizes only textual content from publications as input to the RAG-assisted LLM, excluding other important modalities such as code, data, tables, figures, and supplementary materials. These additional modalities are essential for answering certain queries, and addressing this limitation would require the development of parallel multimodal models. However, this is beyond the scope of the current work and can be explored in future research. Another significant limitation of our work is the time-intensive manual evaluation of LLM-generated content, which requires domain expertise for thorough assessment. Another limitation lies in the designed CQs, as many studies bypass data annotation or omit model deployment details, resulting in low positive response rates for such queries.

A further limitation of this study lies in the publication selection process, which uses a keyword-based approach. Publications that mention relevant keywords even once are included, regardless of whether they actually employ DL methods. To address this, we used an LLM to filter out publications without DL methods, achieving 93% accuracy in the process. However, this means some publications may still have been incorrectly included or excluded. Moreover, the generated textual responses from the LLMs were often ambiguous, blending actual answers with generalized or hallucinated content. This made it challenging for annotators to make precise judgments while annotating evaluation datasets.

The technical limitation of the pipeline is the use of the Groq API. We utilized the free tier, which could become a scalability bottleneck if someone attempted to run the entire pipeline in a single day. Another limitation is the availability of high-end GPUs, which were accessible in our case but may not always be readily available for others.

Conclusions

There is widespread concern about the lack of accessible methodological information in DL studies. We systematically evaluate whether that is the case for biodiversity research. Our approach could be used to alleviate the problem in two ways: (1) by generating machine-accessible descriptions for a corpus of publications (2) by enabling authors and/or reviewers to verify methodological clarity in research articles. In this study, we used an automatic information retrieval method through an RAG-assisted LLM pipeline. Specifically, we employed five LLMs: Llama-3 70B, Llama-3.1 70B, Mixtral-8x22B-Instruct-v0.1, Mixtral 8x7B, and Gemma-2 9B to create an ensemble result, and then comparing the outputs with human responses from previous work (Ahmed et al., 2024b). Our findings revealed that different LLMs generated varying outputs for the same query, indicating that information retrieval is not uniform across models. This underscores the necessity of considering multiple models to achieve more robust and accurate results. Additionally, precisely indexing publications that utilize DL methodologies significantly enhanced our results, and filtering out studies that did not employ these methods improved our findings. Furthermore, our results demonstrated that incorporating multiple modalities enriched the retrieval process, as evidenced by comparisons between the outputs of previous work (Ahmed et al., 2024b) and our study’s outputs. Although our methodology has been demonstrated in the context of biodiversity studies, its applicability extends far beyond this field. It is a versatile approach that can be utilized across various scientific domains, particularly those where detailed, transparent, and reproducible methodological reporting is essential.

In future research, we plan to develop a hybrid system that combines human expertise with LLM capabilities, where the LLMs will evaluate results using a metric to ensure the accuracy of generated outputs. In instances where the metric score is low, humans will manually assess those cases. We also aim to include different modalities (such as code and figures) in the pipeline to ensure more accurate information retrieval.

Appendices

| CQ Nr. | Llama-3 70B | Llama-3.1 70B | Mixtral 8x22B Instruct v0.1 | Mixtral 8x7B | Gemma 2 9B | Domain expert |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 58 | 43 | 50 | 61 | 30 | NA |

| 2 | 91 | 83 | 86 | 98 | 97 | NA |

| 3 | 23 | 24 | 38 | 38 | 14 | NA |

| 4 | 30 | 30 | 35 | 46 | 30 | NA |

| 5 | 74 | 75 | 47 | 51 | 55 | 50 |

| 6 | 36 | 33 | 33 | 53 | 27 | NA |

| 7 | 41 | 38 | 43 | 47 | 35 | NA |

| 8 | 11 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 12 | NA |

| 9 | 11 | 12 | 9 | 5 | 7 | NA |

| 10 | 4 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 9 | 30 |

| 11 | 9 | 9 | 3 | 4 | 8 | NA |

| 12 | 90 | 84 | 88 | 96 | 93 | 96 |

| 13 | 51 | 51 | 44 | 54 | 42 | 77 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 15 | 21 | 14 | NA |

| 15 | 51 | 53 | 52 | 71 | 48 | NA |

| 16 | 30 | 28 | 32 | 40 | 26 | NA |

| 17 | 48 | 48 | 46 | 54 | 30 | NA |

| 18 | 57 | 40 | 64 | 80 | 31 | NA |

| 19 | 43 | 43 | 42 | 50 | 39 | 88 |

| 20 | 42 | 36 | 39 | 59 | 38 | NA |

| 21 | 35 | 40 | 52 | 55 | 13 | NA |

| 22 | 84 | 84 | 83 | 86 | 87 | 85 |

| 23 | 47 | 45 | 64 | 54 | 23 | NA |

| 24 | 38 | 16 | 16 | 33 | 6 | NA |

| 25 | 98 | 89 | 90 | 100 | 94 | NA |

| 26 | 41 | 26 | 23 | 24 | 7 | NA |

| 27 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 42 | 2 | NA |

| 28 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 3 | NA |

| CQ Nr. | Llama-3 70B | Llama-3.1 70B | Mixtral 8x22B Instruct v0.1 | Mixtral 8x7B | Gemma 2 9B | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without filtering | With filtering | Without filtering | With filtering | Without filtering | With filtering | Without filtering | With filtering | Without filtering | With filtering | |

| 1 | 265 | 131 | 199 | 96 | 228 | 110 | 280 | 154 | 101 | 67 |

| 2 | 322 | 226 | 301 | 210 | 281 | 205 | 390 | 246 | 319 | 230 |

| 3 | 71 | 64 | 63 | 56 | 106 | 87 | 106 | 88 | 42 | 36 |

| 4 | 77 | 69 | 77 | 69 | 85 | 73 | 112 | 99 | 73 | 65 |

| 5 | 205 | 157 | 177 | 148 | 138 | 108 | 156 | 121 | 123 | 113 |

| 6 | 133 | 97 | 106 | 85 | 215 | 102 | 212 | 133 | 224 | 125 |

| 7 | 155 | 108 | 140 | 98 | 161 | 110 | 165 | 128 | 121 | 89 |

| 8 | 25 | 19 | 23 | 16 | 20 | 15 | 14 | 12 | 26 | 21 |

| 9 | 29 | 18 | 31 | 22 | 28 | 17 | 21 | 13 | 21 | 13 |

| 10 | 19 | 16 | 23 | 20 | 16 | 13 | 14 | 10 | 26 | 23 |

| 11 | 22 | 16 | 29 | 20 | 11 | 7 | 9 | 8 | 20 | 14 |

| 12 | 281 | 233 | 267 | 222 | 259 | 228 | 294 | 241 | 262 | 229 |

| 13 | 141 | 114 | 143 | 114 | 124 | 107 | 150 | 118 | 112 | 98 |

| 14 | 90 | 46 | 82 | 40 | 80 | 37 | 106 | 58 | 71 | 36 |

| 15 | 128 | 116 | 130 | 114 | 134 | 114 | 199 | 157 | 119 | 109 |

| 16 | 99 | 77 | 83 | 70 | 95 | 75 | 139 | 100 | 75 | 62 |

| 17 | 132 | 106 | 109 | 90 | 158 | 95 | 167 | 132 | 82 | 72 |

| 18 | 211 | 135 | 177 | 102 | 240 | 158 | 324 | 205 | 113 | 79 |

| 19 | 107 | 97 | 106 | 95 | 98 | 91 | 164 | 136 | 98 | 91 |

| 20 | 107 | 98 | 95 | 89 | 98 | 92 | 156 | 124 | 98 | 92 |

| 21 | 142 | 83 | 126 | 82 | 237 | 127 | 230 | 141 | 50 | 34 |

| 22 | 352 | 223 | 348 | 225 | 321 | 210 | 321 | 223 | 302 | 222 |

| 23 | 191 | 120 | 186 | 120 | 227 | 154 | 209 | 148 | 89 | 65 |

| 24 | 117 | 89 | 47 | 38 | 73 | 36 | 186 | 118 | 87 | 58 |

| 25 | 357 | 243 | 340 | 242 | 301 | 226 | 357 | 246 | 320 | 239 |

| 26 | 118 | 89 | 78 | 58 | 113 | 59 | 112 | 63 | 31 | 23 |

| 27 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 11 | 10 | 115 | 97 | 6 | 5 |

| 28 | 18 | 8 | 26 | 16 | 11 | 6 | 17 | 7 | 15 | 7 |

| CQ number | Deep learning variable from Ahmed et al. (2024b) | Agreements between human response and Mixtral 8x22B Instruct v0.1 | Agreements between human response and Mixtral 8x7B | Agreements between human response and Llama 3.1 70B | Agreements between human response and Llama 3 70B | Agreements between human response and Gemma 2 9B | Agreements between human response and voting classifier |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | Dataset | 59 | 61 | 55 | 58 | 63 | 63 |

| 10 | Source code | 74 | 73 | 73 | 74 | 73 | 74 |

| 12 | Model architecture | 88 | 94 | 84 | 90 | 93 | 89 |

| 13 | Hyperparameters | 59 | 63 | 64 | 66 | 61 | 63 |

| 19 | Open source framework | 54 | 60 | 55 | 55 | 51 | 53 |

| 22 | Metrics availability | 78 | 77 | 75 | 73 | 76 | 75 |