Prolonged growth and extended subadult development in the Tyrannosaurus rex species complex revealed by expanded histological sampling and statistical modeling

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Fabien Knoll

- Subject Areas

- Paleontology, Statistics, Histology

- Keywords

- Osteohistology, Dinosaur, Tyrannosaur, Growth, Life history, Statistics, Species complex

- Copyright

- © 2026 Woodward et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2026. Prolonged growth and extended subadult development in the Tyrannosaurus rex species complex revealed by expanded histological sampling and statistical modeling. PeerJ 14:e20469 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.20469

Abstract

Background

Tyrannosaurus rex, one of the most iconic non-avialan dinosaurs, remains a central focus of paleobiological research. Growth modeling suggests T. rex exceeded 8,000 kg within two decades and had a lifespan approaching 30 years. However, this understanding of T. rex growth dynamics is dependent on single-point histological sampling of multiple skeletal elements and lacks specimens encompassing the earliest growth states.

Methods

We present the most comprehensive histological analysis of Tyrannosaurus ontogeny to date, based on transverse diaphyseal sections of femora and tibiae from 17 individuals ranging from small juveniles to large adults. Four alternative statistical models were tested, differing in the treatment of cortical growth marks, including annulus-like birefringent bands visible only in cross-polarized light. Due to high intraspecies morphological variability, the taxonomic status of many Tyrannosaurus specimens is debated, prompting use of the term “Tyrannosaurus rex species complex” to describe our dataset.

Results

The best-supported model incorporated all visible growth marks, produced the narrowest confidence bands, and indicated lower maximum growth rates and a delayed attainment of asymptotic size (~35–40 years) compared with earlier estimates. We also find that two immature specimens within the Tyrannosaurus rex species complex are not statistically compatible with the other growth series. Our approach is the first in dinosaur skeletochronology to simultaneously estimate the position of the earliest preserved growth mark across specimens, while fitting sigmoidal curves with simultaneous confidence bands. We find the inclusion of double growth marks and those visible only with cross polarized light provide better statistical model fits and this may have implications for modeling other taxa. Additionally, we find no strong link from extant vertebrates to support the idea that the growth inflection point is biologically significant and corresponds to sexual maturity. Our results suggest that the Tyrannosaurus rex species complex grew more gradually and over a longer lifespan than indicated by prior models, with a protracted period of subadult development.

Introduction

Tyrannosaurus rex (Osborn, 1905) is among the most iconic and scientifically impactful non-avialan dinosaurs known to paleontology. Ongoing research affords an increasingly nuanced understanding of its paleobiology, functional morphology, and ontogeny: cranial adaptations, including enlarged olfactory bulbs, a highly developed inner ear, and intricate trigeminal nerve branching suggest acute sensory capabilities (Witmer & Ridgely, 2010; Bouabdellah, Lessner & Benoit, 2022; Kawabe & Hattori, 2022) while biomechanical analyses of cranial function, bite force, and postcrania support interpretations of adult Tyrannosaurus rex as an agile, bone-crushing carnivore (Gignac & Erickson, 2017; Snively et al., 2019; Rowe & Snively, 2022). Additionally, intensive collection efforts since its initial discovery have enabled detailed morphological study, producing a “Tyrannosaurus rex species complex”; some researchers advocate a different taxonomic assignment for small-bodied specimens (Bakker, Williams & Currie, 1988; Larson, 2008, 2013; Witmer & Ridgely, 2010; Tsuihiji et al., 2011; Schmerge & Rothschild, 2016; Longrich & Saitta, 2024) and new species based on stratigraphic (Paul, Persons & Raalte, 2022; Paul, 2025) or geographic (Dalman et al., 2024) separation, while others argue that these differences reflect ontogenetic change (Carr & Williamson, 2004; Brusatte et al., 2016; Carr, 2020; Woodward et al., 2020; Voris et al., 2025) and that weak stratigraphic resolution hinders additional species assignment (Carr et al., 2022).

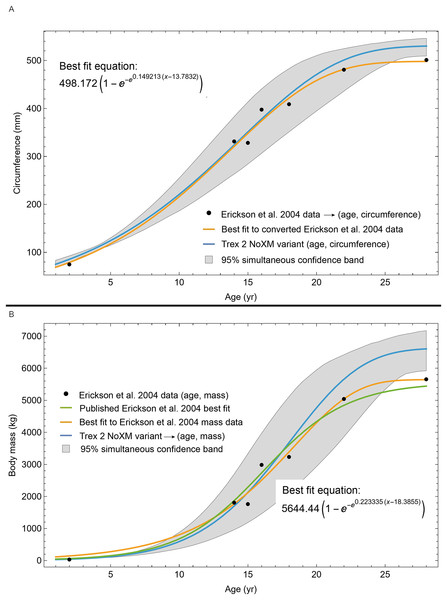

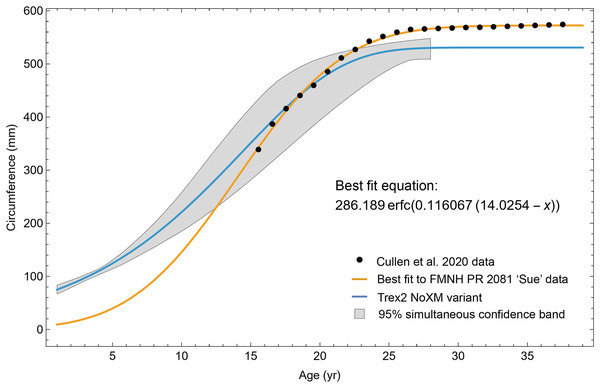

With respect to ontogeny, skeletal microstructure reveals rapid growth rates in Tyrannosaurus, with individuals reaching adult body masses of over 8,000 kg within approximately two decades and with an estimated lifespan of nearly 30 years (Erickson et al., 2004; Horner & Padian, 2004; Cullen et al., 2020; Persons, Currie & Erickson, 2020; Woodward et al., 2020). Here, we present a revised growth model for the Tyrannosaurus rex species complex, constructed from the most comprehensive ontogenetic sample analyzed to date and enabling a more complete reconstruction of life history.

The first quantitative models of Tyrannosaurus growth were based on skeletochronology (Erickson et al., 2004; Horner & Padian, 2004). In particular, the body mass model developed by Erickson et al. (2004) has served as a foundational framework for estimating the age and body mass of more recently discovered specimens (e.g., Cullen et al., 2020; Persons, Currie & Erickson, 2020), as well as for studies addressing ontogenetic morphological change (Carr et al., 2022), species abundance (Marshall et al., 2021), growth constraints (Persons, Currie & Erickson, 2020; Mallon & Hone, 2024), and phylogenetic relationships (Paul, Persons & Raalte, 2022; Longrich & Saitta, 2024; Paul, 2025). The (Erickson et al., 2004) model was based on seven individuals of varying ontogenetic stages and the authors derived age estimates from a range of skeletal elements (e.g., ribs, gastralia, limb bones), each with differing remodeling rates. Subsequent validation of bone histology shows that intraskeletal variability in growth mark preservation can compromise age estimates based on mixed-element sampling (e.g., Cullen et al., 2014; Woodward, Horner & Farlow, 2014; Heck & Woodward, 2021; Chapelle et al., 2022). Moreover, the (Erickson et al., 2004) growth curve included only a single specimen in the exponential (juvenile) phase of the sigmoidal model, with the remaining individuals situated in either the linear or asymptotic phases (Myhrvold, 2013). Consequently, growth dynamics during early and late juvenile stages remain poorly resolved. Additionally, Erickson et al. (2004) utilized the “whole bone” approach where each individual was represented by a single data point. In this method cortical growth marks are only counted to estimate age at death, ignoring size-at-age data that can be gleaned from interior growth marks, thus greatly restricting specimen utility for ontogenetic inferences.

In response to these limitations and owing to additional Tyrannosaurus fossil discoveries since (Erickson et al., 2004), we have assembled and histologically sampled the broadest ontogenetic series of Tyrannosaurus rex species complex tibiae and femora to date, yielding the largest dataset of transverse diaphyseal sections for this taxon. Our sample spans seventeen individuals, ranging from early juveniles to mature adults, and includes 12 transverse sections suitable for longitudinal growth modeling. By focusing exclusively on weight-bearing elements (femur and tibia) and using transverse sections rather than core samples or fragments, this study provides enhanced resolution and comparability in growth rate estimation across individuals. Importantly, our sample encompasses key transitional stages—early to late juvenile and early subadult—thus allowing for a more continuous and robust reconstruction of the life history and growth trajectory of Tyrannosaurus.

We show that during the annual period of active growth, Tyrannosaurus bone apposition rates were between 25 and 100 microns per day from early juvenile through late subadult stages, with slower rates (<10 microns per day) occurring only in the outer cortex of the largest individuals. Each specimen exhibited annual growth rate plasticity throughout ontogeny, and we modeled four variants of the dataset that differed in how cortical growth marks were identified and quantified. The model with the highest statistical support considered each growth mark as representing a single year hiatus and included annulus-like birefringent bands observed in cross-polarized light. The corresponding best-fit sigmoid growth curve contrasts with earlier models, showing subadult Tyrannosaurus growth was protracted, resulting in a growth asymptote at ~35–40 years of age, 15 years later than previously reported.

Materials and Methods

Specimen selection

Femur and tibia thin sections for this study are from seventeen individuals (Table 1), referred to Tyrannosaurus rex in museum collections. Slides include those from new specimens added to this study as well as those from specimens previously examined in Horner & Padian (2004). The Tyrannosaurus rex specimens in our study are from a geographically narrow area, with all but one having been collected from eastern Montana (BDM 050 was collected from North Dakota). However, because the taxonomic assignment of some Tyrannosaurus rex specimens is debated, going forward we refer to our sample as a Tyrannosaurus rex “species complex”, loosely adopting this biological term describing a genus in which the high intraspecific variability makes species designations ambiguous or controversial (see Liebers, Knijff & Helbig, 2004; Muñoz et al., 2013; Meik et al., 2015; Finkbeiner et al., 2025 for applications of the term “species complex”). Consistent with this usage, species complex is not intended to be synonymous with the group being monophyletic, but rather indicate that the systematics are not fully resolved.

| Specimen number | Museum-assigned taxonomic designation | Element sampled | Digital restoration? | Average slide thickness (microns) if prepared for this study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDM 050 | Tyrannosaurus rex | Femur, Tibia, Fibula | Yes, tibia | Femur, 180; Tibia, 250; Fibula, 90 |

| BMRP 2002.4.1 | Tyrannosaurus rex | Femur, Tibia | Yes, tibia | Tibia, 100 |

| BMRP 2006.4.4 | Tyrannosaurus rex | Femur, Tibia | No | Femur, 160 |

| CCM V33.1.15 | Tyrannosaurus rex | Tibia | No | 125 |

| DDM 35 | Tyrannosaurus rex | Tibia | No | – |

| DDM 35.68 | Tyrannosaurus rex | Tibia | No | – |

| MOR 009 | Tyrannosaurus rex | Tibia | Yes | – |

| MOR 1125 | Tyrannosaurus rex | Femur | Yes | – |

| MOR 1128 | Tyrannosaurus rex | Tibia | Yes | – |

| MOR 1156 | Tyrannosaurus rex | Tibia | No | – |

| MOR 1189 | Tyrannosaurus rex | Tibia | Yes | 250 |

| MOR 1198 | Tyrannosaurus rex | Femur | No | – |

| MOR 2949 | Tyrannosaurus rex | Tibia | Yes | 275 |

| MOR 2970 | Tyrannosaurus rex | Tibia | No | – |

| MOR 9756 | Tyrannosaurus rex | Tibia | No | 200 |

| MOR 9757 | Tyrannosaurus rex | Femur, Tibia | Yes, tibia | Femur, 240; Tibia, 250 |

| USNM 555000 | Tyrannosaurus rex | Tibia | Yes | – |

| TMP 1986.144.0001 | Gorgosaurus libratus | Femur | No | 245 |

| TMP 1994.012.0602 | Gorgosaurus libratus | Femur, Tibia | Yes, tibia | 240 |

We were unable to enhance our sample size further with other previously published specimens, as thin section slides from the T. rex life history analysis of Erickson et al. (2004) have remained under study since that publication. We were also unable to include FMNH PR2081 in our sample, one of the largest specimens of Tyrannosaurus, because the core sampling methodology used to obtain cortical growth mark (CGM) circumferences (Cullen et al., 2020) greatly differs from ours (transverse sections) reducing confidence in growth curve comparisons (see Woodward et al., 2020 for discussion). For each individual, the choice of sampling femur or tibia was dependent on the material available for consumptive analyses. We limited our study to the femur and tibia for growth curve modeling because their circumferences can be translated to body mass using published methods such as Campione et al. (2014), and because femur and tibia circumferences of non-avialan theropods scale tightly with one another (D’Emic et al., 2023). While the latter relationship allowed us to combine femur and tibia datasets to increase ontogenetic sample size, for modeling Tyrannosaurus rex species complex growth our sample still consisted of 11 tibiae and only one femur. We also examined the femur and tibia bone microstructure of two Gorgosaurus libratus to permit qualitative growth comparisons between the Tyrannosaurus rex species complex and smaller tyrannosaurid taxa (see Table 1 for full specimen list and Table S1 for individual specimen raw data). Histology sampling permission for this study was granted by Greg Liggett (BLM), Josh Mathews (BMRP), John Scannella and Eric Metz (MOR), Denver Fowler (BDM), Nathan Carroll and Sabre Moore (CCM), Donald Brinkman and Brandon Strilisky (TMP). Daniel Barta and Roger Benson granted access to Coelophysis thin sections. Carrie Levitt-Bussian granted access to Allosaurus thin sections.

Thin section processing

Specimens of Tyrannosaurus and Gorgosaurus were sampled transversely within the diaphysis (de Buffrénil, Quilhac & Castanet, 2021) inferior to the fourth trochanter (femur) and fibular crest (tibia). Specimen documentation included photographs, line drawings, 3D laser surface scans, and photogrammetry. Molds and casts of the sampled diaphyseal pieces were also produced upon institutional request. Sample and thin section processing followed the protocol of Lamm (2013), briefly described here. Depending on specimen size, initial cuts to remove diaphyseal samples were done with a Buehler Isomet 1000 wafering saw, Husqvarna Tilematic tile saw, or a Jet bandsaw, each fitted with a continuous diamond blade. The samples were embedded in Silmar 95BA-41 polyester resin for stabilization. From the cured resin blocks ~3 mm-thick wafers of embedded bone were removed, using the appropriate saw, and glued to frosted plastic slides with Starbond medium viscosity cyanoacrylate glue. In some cases, diaphyseal transverse section wafers were too large for a single 2″ × 3″ or 2.5″ × 3.5″ plastic slide. Those wafers were cut into smaller pieces using the tile saw, and each wafer segment was then glued to a plastic slide. Kerf loss associated with each cut was approximately 2 mm. Slides were hand polished using progressively finer grit silicon carbide papers on a Buehler Ecomet 4 grinder-polisher to a final thickness between 80 and 200 microns (Table 1) dependent upon the thickness at which optical clarity was achieved.

Thin section imaging

Digital slide images were obtained at the Museum of the Rockies (MOR) or Oklahoma State University Center for Health Sciences (OSU-CHS). At MOR, slides were imaged using a Nikon Optiphot2-POL polarizing microscope, Nikon DS-Fi-2 digital camera, and Prior motorized stage. Photomontages of each slide were assembled using Nikon NIS Elements: Basic Research. Imaging at OSU-CHS was done using a Nikon Eclipse polarizing microscope, Nikon Fi2 digital camera, and ASI motorized stage. Photomontages were assembled in the software package Nikon NIS Elements: Documentation. To aid in growth mark identification, slides were imaged in plane polarized light (PPL) and in circularly polarized light (CPL). For transverse sections comprised of more than one slide, each thin section was imaged as described above and digitally reassembled using Photoshop CC. The measure tool was used to adjust the spacing between individual slides to accommodate kerf loss. Requests for documentation, photogrammetry files of specimens, full resolution digital thin section images, and Photoshop files can be made to the respective institutions where sampled specimens are reposited (Table S1). Digital thin section images are also accessible on Figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29944892.v1).

In many cases, the diaphysis of a specimen was diagenetically crushed. Transverse sections of such diaphyses were reassembled from fragments in Photoshop CC using layers to incrementally restore the circular shape of the cortex using only rigid motion of the fragments without deformation (Table 1). For MOR 1128 and USNM 555000 (formerly MOR 555) only a partial tibial transverse section had been removed for earlier histology studies and a cast replica of the portion removed had been restored to the respective tibia. The skeleton of USNM 555000 was later digitized and made publicly available (https://3d.si.edu/object/nmnhpaleobiology_10250729, last accessed August 2025). The sampling location is visible on the skinned model, making it possible to obtain an associated digital transverse section using Meshlab (Cignoni et al., 2008) software. The image of the cross-section outline produced in Meshlab was imported as a layer in Photoshop CC and fitted to the partial tibia photomicrograph of USNM 555000 using the scale transformation command, completing the shape of the periosteal surface (Fig. 1). Again, using the scale transformation command, this outline layer was subsequently used to complete the periosteal surface of the partial transverse section of MOR 1128. In both cases, the diaphyseal circumferences (or more properly, perimeters) measured from the digital periosteal surface restorations approached measurement values taken with a flexible tape measure prior to sample removal.

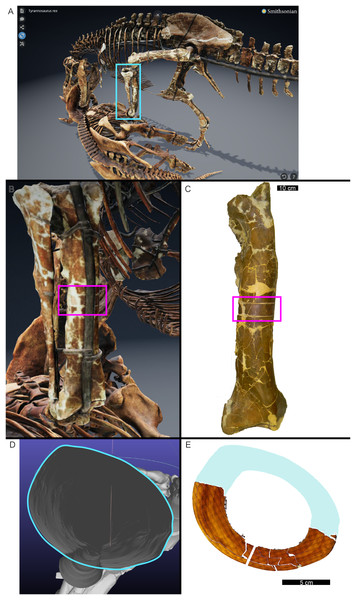

Figure 1: The cortical perimeter of the left tibia from USNM 555000 was reconstructed using the digital skeleton publicly available from Smithsonian 3D Digitization (https://3d.si.edu/).

(A) Screen-capture of the Tyrannosaurus digital model. Blue box indicates the region of interest in panel B, which includes the left tibia. (B) The digitized left tibia. The purple box indicates the region of sample removal and replica cast restoration. (C) Photograph of left tibia after replica cast restoration. Purple box indicates the same region visible in panel B. (D) A transverse slice through the digital model was obtained at the region of interest indicated in panels B and C using Meshlab software. A screen capture of the slice was imported into Photoshop CC and the perimeter digitally traced using the pencil tool (blue outline). (E) The layer of digital tracing was fitted to the digitized thin section of tibia USNM 555000 to restore the missing cortex, indicated in blue.CGM identification

Since the results of our study are dependent on the identification of cortical growth marks, their morphology is described here. Skeletal growth marks (sensu de Buffrénil & Quilhac, 2021) include the cyclical and non-cyclical marks in tooth enamel, tooth dentine, tooth cementum, and bone. In turn, cortical growth marks (CGM) are specific to endochondral and intramembranous bone and include lines of arrested growth (LAG) and annuli. LAG and annuli result from (typically annual) decreases in cortical bone apposition rate (see de Buffrénil & Quilhac, 2021 for a review). Thus, CGM record the diaphyseal cross-sectional shape of the periosteal surface during the annual hiatus (de Buffrénil, Quilhac & Castanet, 2021)). The periodicity of LAG and annuli is well-documented in extant vertebrate taxa (Klevezal, 1996; Köhler et al., 2012; de Buffrénil & Quilhac, 2021, and references therein) and CGM are utilized extensively in extant and extinct vertebrate skeletochronology, while the zones of primary bone tissue between CGM are used to estimate the apposition rates between hiatus events.

In more detail, a LAG forms at the periosteal surface during appositional growth arrest (de Buffrénil & Quilhac, 2021). It is a ~10 micron-thick, hyper-mineralized line within the bone cortex, visible once periosteal apposition resumes. In contrast, an annulus represents a period of decreased apposition relative to the surrounding primary matrix, resulting in a diffuse ring rather than a distinct line (de Buffrénil & Quilhac, 2021; de Buffrénil, Quilhac & Castanet, 2021). The presence of annuli and LAG are not mutually exclusive (de Buffrénil, Quilhac & Castanet, 2021), and one CGM type can also transition into the other at different locations about the cortex (Pereyra et al., 2024).

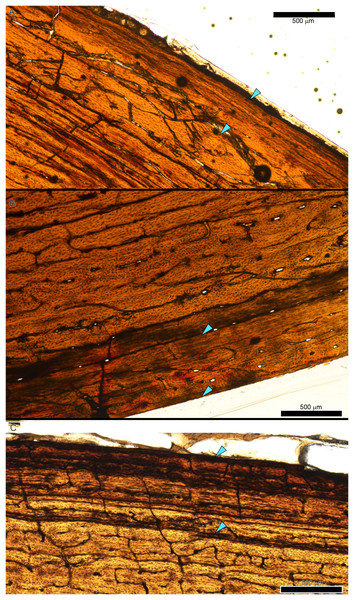

While LAG may be readily observed in bright field or plane polarized light (PPL) as solid thin lines, annuli are more difficult to discern due to their diffuse appearance. In PPL annuli may be recognized as localized bands of differing vascular canal organization, reduced vascular canal and osteocyte lacuna density, and/or flattened osteocyte lacunae. An annulus is commonly formed of parallel-fibered tissue within a woven matrix, or of lamellar tissue if within a parallel-fibered matrix (de Buffrénil & Quilhac, 2021). As a result, in cross-polarized light (XPL) annuli are more readily identified than in PPL because the parallel or lamellar fiber arrangement results in higher birefringence compared to the less organized fiber matrix to either side (Bromage et al., 2003; de Buffrénil & Quilhac, 2021). Indeed, within our sample, some annuli were only visible when viewed in cross-polarized light (XPL). Because these anisotropic fibers remain parallel to the plane of section while forming the circular annulus, at regular 90-degree intervals the fibers do not interfere with the transmission of polarized light and remain dark, or extinct. We therefore used circularly polarized light (CPL) which allowed us to more easily differentiate annuli from surrounding regional variations in tissue matrix birefringence (Fig. 2). Circularly polarized light (CPL) is cross-polarized light with the addition of two quarter-wave plates which eliminate the periodic light extinction, resulting in birefringence of the annulus over its entire 360-degree arc (Bromage et al., 2003).

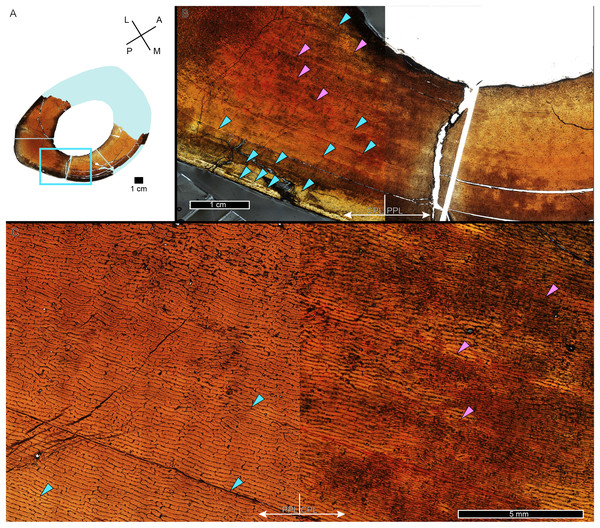

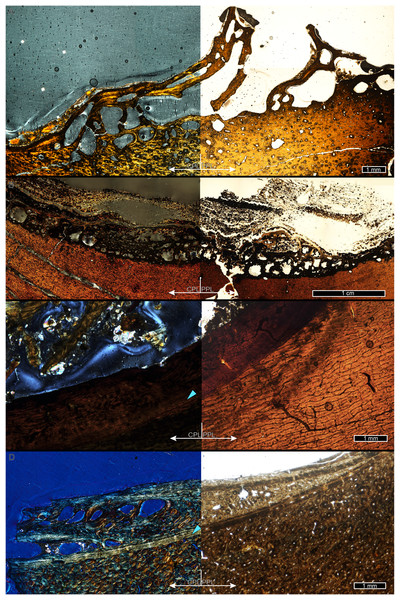

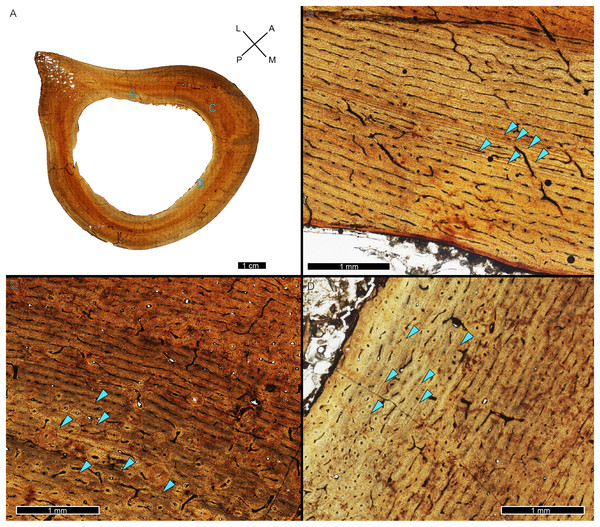

Figure 2: Some CGM within the tibia of MOR 1128 are only visible as birefringent annuli in CPL.

(A) Tibia transverse section, imaged in PPL. The light blue shading represents missing cortex. Box indicates region of interest in panel B. (B) Posteromedial cortex, with left half of image in CPL and right half of image in PPL. Purple arrows point to CGM only visible in CPL and blue arrows point to CGM visible in PPL. (C) Enlarged region of panel B. The left half of the image is in PPL, while the right half is imaged in CPL. Purple arrows point to CGM only visible in CPL, while blue arrows point to CGM visible in PPL. CGM, cortical growth mark; PPL, plane polarized light; CPL, circularly polarized light. Cross section orientations: A, anterior; M, medial; P, posterior; L, lateral.Multiplets

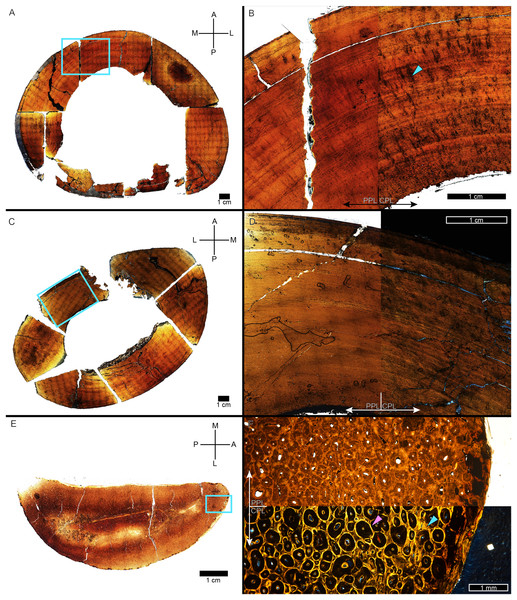

A zone of bone matrix may be thinner (i.e., CGM are more closely spaced) than the preceding or following zone. The CGM bounding the zone are either parallel to one another over their circumferences or the zone may result from a single CGM splitting into one or more lines about the cortex (e.g., Snover & Hohn, 2004). The literature uses the term ‘double LAG’ to refer to merging CGM as well as closely-spaced parallel CGM, with the latter configuration renamed a ‘doublet’ in recent paleohistology studies (e.g., Lee & O’Connor, 2013; Zanno et al., 2019; Funston & Currie, 2021; Qin et al., 2021; Jurašeková et al., 2022; Krumenacker, Zanno & Sues, 2022) or ‘couplet’ (Jevnikar, 2022) and as ‘double/multi-cortical growth marks’ (D’Emic et al., 2023). The terms doublet and couplet imply two lines, but we frequently observe three or even four parallel CGM (i.e., more than one zone). For this reason, here we refer to two or more CGM with thinner zones relative to adjacent zones as a multiplet (see Discussion), and use ‘double LAG’ to refer to CGM that split and merge over their circumference (Fig. 3).

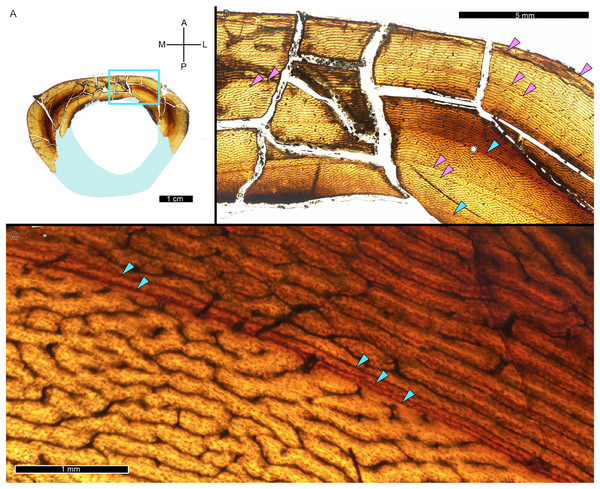

Figure 3: Visual comparison between multiplet CGM and a double-triple CGM in the tibia of MOR 1189.

(A) Tibia transverse section. Light blue shading represents missing cortex. Box indicates the region of interest in panel B. (B) Anterolateral region of tibia cortex. Blue arrows point to single CGM and purple arrows point to multiplet CGM, the latter identified by a grouping of two or more CGM in closer proximity to one another than to adjacent CGM. The asterisk indicates the region of interest in panel C. (C) A double-triple CGM, defined by splitting and merging of one CGM. On the right, three lines are visible (three arrows), and towards the left, they merge into two lines (two arrows). All panels in plane polarized light. CGM, cortical growth mark. Cross section orientations: A, anterior; M, medial; P, posterior; L, lateral.CGM quantification

To model growth of each Tyrannosaurus specimen, CGM as well as cortical endosteal and periosteal surfaces were traced from the digitized transverse thin section PPL and CPL images using layers in Photoshop CC and the pencil tool. CGM within multiplets were traced individually, and annuli only visible in XPL were also included in the CGM dataset. In some cases, CGM were incomplete owing to medullary expansion, secondary remodeling, or taphonomic preservation (e.g., cracks or missing fragments). If enough of a CGM remained to reasonably estimate the shape, we used the nearest complete CGM as a template and scaled to fit the visible remainder of the partial CGM (de Buffrénil, Quilhac & Castanet, 2021). On the other hand, if a CGM was only visible a short distance such that its general shape was unclear, its presence was counted but restoration was not attempted.

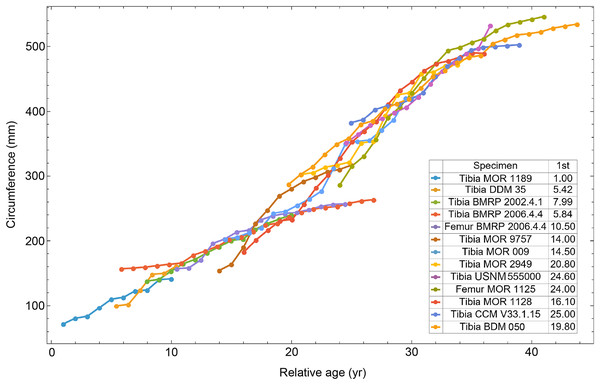

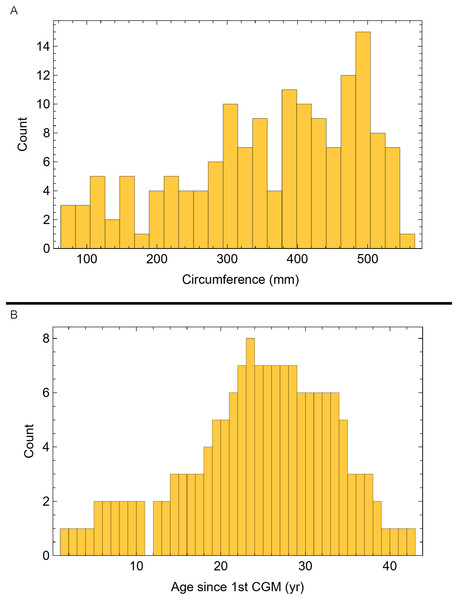

Once CGM were identified and traced, Fiji (Schindelin et al., 2012) and the BoneJ plugin (Doube et al., 2010) was used to quantify the geometric centroid of the transverse section, CGM circumferences and inclusive areas of each CGM, and circumferences of the periosteal and endosteal surfaces (after Woodward et al., 2015). Distances from the geometric centroid to the periosteal surface, endosteal surface, and to each CGM along major and minor axes were quantified in Photoshop CC using the measure tool. From these measurements, an ontogenetic dataset was produced for each Tyrannosaurus specimen in the study included in growth modeling (Table S1). The same data were collected for Gorgosaurus (Table S1) but since there were only two specimens available for analysis, growth modeling was not performed. The growth series for variant A of Tyrannosaurus are plotted in Fig. 4, other variants in Figs. S1–S6, Gorgosaurus in Figs. S7, S8.

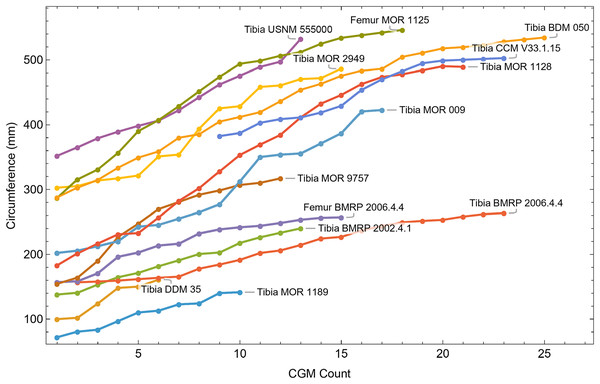

Figure 4: Plot of the growth series for Tyrannosaurus, dataset Trex1, variant A.

The lines plot raw growth series obtained from measuring CGM on thin sections of femora and tibiae of Tyrannosaurus. The CGM growth series for each specimen consist of a set of CGM counts (x-axis) and CGM circumference (y-axis): see Eqs. (1), (2). These data include all CGM found in the specimens (Table S1). Plots for other variants in Figs. S3, S4.Growth modeling

The femur and/or tibia histology of seventeen individuals in the Tyrannosaurus rex species complex contributed to qualitative assessments of life history. Unfortunately, the diaphyses of five specimens were too fragmentary (MOR 1156, MOR 1198, DDM 35.68) or taphonomically damaged post-burial (MOR 2970, MOR 9756) to accurately quantify CGM or circumferences from thin sections and were therefore omitted for modeling. However, the qualitative nature of these specimens is consistent with the others. The Wolfram Mathematica software package (Wolfram Research, Inc., 2024) was used to perform growth modeling using the twelve remaining individuals in the dataset which were represented by either a femur or tibia, and by both femur and tibia in the case of BMRP 2006.4.4.

Due to medullary cavity expansion during ontogeny, observed CGM constitute an incomplete record of life history, and the absolute age of a specimen must be estimated. For each dataset, the age of the earliest preserved CGM in each growth series was set relative to that of MOR 1189, the growth series with the smallest circumference CGM. A least squares clustering (Myhrvold, 2013) was applied to determine the optimal overlap between the specimen datasets and to estimate the youngest (starting) age preserved in each growth series. Once age at the first observed CGM was estimated for each specimen, the growth series for that specimen was shifted so that the first CGM lined up with its estimated age. Nonlinear ordinary least squares (OLS) equations are typically used to fit a sigmoid curve to the growth series data. Here, we instead applied a novel approach. Rather than estimating the starting ages as the initial step followed by nonlinear OLS as is conventional for modeling dinosaur growth, we treated starting ages as independent variables and estimated them at the same time as the sigmoid function parameters using least squares optimization.

The best fit curve from the Tyrannosaurus rex species complex dataset was dependent upon how CGM within multiplets and CGM identified as XPL-only annuli were treated within each specimen growth series. Therefore, we developed four variants of the dataset, each using a different interpretation and mapped observed histology to CGM data for modeling. The variant “A” considered all of the marks: XPL annuli, conventional CGM (i.e., LAG and annuli visible in PPL), and each CGM within a multiplet to represent a unique annual hiatus. Variant “NoM” (for no multiplets) counted XPL-only annuli and conventional CGM as annual but considered a multiplet grouping to represent a single hiatus event. For the “NoX” variant, each CGM in a multiplet and each conventional CGM were counted individually but XPL annuli were excluded. Finally, the “NoXM” variant matches the previous practice in dinosaur growth literature which omits CGM deemed to be multiplets, and which have not reported the existence of XPL-only annuli. Thus, each growth series had a different CGM count depending upon the dataset variant considered. The counts of multiplet and XPL-only annuli for each specimen appear in Table S2 and the series are plotted in Figs. S1, S2. Separate analyses for each variant were maintained to test the characteristics of the underlying histological interpretations, which is particularly important because some interpretations are newly proposed here. Nine different sigmoidal growth curves were produced to increase the likelihood of finding the fit that most closely matched the datasets. For diagnostic purposes, linear and quadratic non-sigmoidal curves were also fitted, and full lists appear in Tables S3, S4. Finally, the corrected Akaike information criterion (AICc) was used for model selection (Burnham & Anderson, 2002). Statistical uncertainty was then determined by estimating the 95% simultaneous confidence band (CB) for each of the best fits using parametric bootstrap methods (Montiel Olea & Plagborg-Møller, 2019). For performing the bootstrap resampling, fractional random weighting (FRW) bootstrap was used (Xu et al., 2020). In addition to arithmetic fitting, logarithmic fitting was performed to account for heteroskedasticity in the data and to more equally balance the distribution of errors. Lastly, earlier studies sometimes converted from CGM circumference to body mass using a correlation (Campione & Evans, 2012) before curve fitting. However, we preferred to perform the growth analyses on circumference data then later convert to mass if needed (Myhrvold, 2013).

Results

Bone microstructure

The primary cortical matrix of femora and tibiae from all Tyrannosaurus and Gorgosaurus specimens studied here was a woven-parallel complex separated into zones by cortical growth marks (see de Buffrénil & Quilhac, 2021 for bone tissue terminology). Multiplets were observed in all but one specimen, and XPL-only annuli were present in most specimens (Figs. S1, S2 and Tables S1, S2). Vascularity was plexiform to laminar, with reticular canals somewhat more common in the smaller individuals. A well-developed external fundamental system (EFS), indicating skeletal maturity (de Buffrénil & Quilhac, 2021), was observed in Gorgosaurus TMP 1994.012.0602. Tyrannosaurus tibiae CCM V33.1.15 and BDM 050 exhibit possible incipient EFS: in each case the outermost cortex is somewhat less vascularized than the rest of the cortex and contains several closely spaced CGMs within lamellar tissue.

Despite avoiding sampling on bony processes when possible, narrow columns of secondary osteons were present in both femur and tibia cortices and were likely associated with ligament or muscle attachment. Outside of these localized regions, there was virtually no Haversian remodeling in the two Gorgosaurus specimens and dense Haversian systems were only present in ontogenetically older Tyrannosaurus. In such cases typically only CGM within the innermost cortex were obscured by secondary osteons to such a level that reconstructing CGM shape was difficult or impossible.

For one specimen, Tyrannosaurus BDM 050, the ipsilateral femur, tibia, and fibula were made available for histological analyses. This afforded a unique opportunity for intraskeletal osteohistological comparisons of hindlimb elements. As with other specimens in our sample, BDM 050 femur and tibia bone microstructure were of a zonal plexiform to laminar woven-parallel complex from inner to outer cortex. Secondary osteon frequency within the inner cortex of the femur was 10–15% higher than that of the tibia. In contrast, the entire cortex of the fibula was remodeled by numerous secondary osteon generations. Slow-forming lamellar tissue was infrequently visible interstitially at the periosteal surface of the fibula. No EFS was observed in the femur. While a possible EFS was visible in the tibia, not enough primary tissue was visible in the fibula to determine whether the lamellar tissue at the periosteal surface was an EFS or was simply a product of slow diaphyseal apposition in late ontogeny.

Dataset curve fitting

Biological growth studies are based on a framework that assumes growth of the organism follows a smooth mathematical curve, typically a sigmoid, on which random variations are superimposed. These variations include any factor that could affect growth such as individual genetic differences, environmental or resource factors, illness, injury or pathology, or sexual size dimorphism. A growth curve for an individual specimen will express properties unique to it, while a growth curve for a population will average out individual differences to yield typical population growth behavior. Statistical methods are then used to produce the curve and associated uncertainty, which removes the random variations to the best extent possible. This paradigm has been widely successful across many biological domains, including plant, animal, bacterial colony, and even tumors (Benzekry et al., 2014; Kawano, Wallbridge & Plummer, 2020), providing strong motivation for its application to modeling dinosaur growth.

For each dataset variant, a Tyrannosaurus CGM growth series gs is a list of N pairs where is the CGM count for the ith CGM, which has a size parameter .

(1) Here, the size parameter for primary data is the CGM circumference, so will be referred to as .

Typically, the CGM count increases by 1 between each pair in series, i.e., , consistent with the assumption that a CGM records an appositional decrease or pause after one year of growth (see section on CGM identification above). However, in some specimens we found that a CGM circumference could not be accurately estimated individually but the existence of these CGM could be counted. This occurred, for example, in the innermost cortex where CGM were almost wholly destroyed due to medullary expansion, in outermost cortex of larger specimens where CGM spacing was compressed, or when CGM were only partially visible due to taphonomic periosteal surface erosion. In such situations the growth series records only the CGM with measurable circumferences, skipping those that could not be measured but including them in the CGM count. In that case, , will occur for some values of i.

Conversely, there were cases where remodeling of the medullary cavity left countable evidence of earlier CGM but not enough remained intact to estimate a circumference. In such a case . When there are M specimens of the same taxon, Eq. (1) is generalized as follows.

(2)

For each growth series a starting age must be estimated. Since absolute age of a specimen cannot be determined due to medullary cavity remodeling, we adopt the convention of setting , so the starts are the starting ages relative to a first growth series, MOR 1189, as it has the smallest circumference CGM. The starting age is applied to a growth series by adding the start to each of the , forming a growth series with starts . The union of these sets is the age and size data that is used to fit a growth curve.

Earlier dinosaur growth studies estimated starting ages using several ad hoc methods including examining the curves by eye, or by various ‘retrocalculation’ methods involving nesting the thin section slides by size to see where CGM between specimens might overlap (e.g., Chinsamy, 1993; Horner & Padian, 2004; Bybee, Lee & Lamm, 2006). Using growth records from multiple specimens in this way resulted in a composite growth series that better modeled the population as a whole and contained a longer span of data than that provided by any individual specimen. Unfortunately, these methods were subjective and prone to error. For example, matching thin section contours visually requires making comparisons between curves that are not the same shape. Here we similarly seek to produce a composite growth series but do so by applying improved and objective algorithms.

Myhrvold (2013) introduced the first algorithmic method, which uses a least squares clustering to determine the optimal overlap between the specimens (Fig. S9). An application of this method to the growth series in Fig. 1 is shown in Fig. 5 (see also Figs. S10, S11). This least squares minimization method has several weaknesses. First, it only works if each growth series is overlapped by one or more other growth series, and these mutually overlapping series must include the entire dataset. There is no guarantee that these requirements are met, although it happens that the Tyrannosaurus series have sufficient CGM count and overlap to have this property. A second and more detailed objection is that the least squares minimization prioritizes overlaps between individual growth series proportional to the amount of overlap present. Despite the potential disadvantages, an objective algorithm is preferred to a subjective placement by eye.

Figure 5: Starting ages of the growth series in the Trex1 A dataset are assigned to minimize series-to-series overlap distance.

For each specimen, the starting CGM age is estimated using least squares minimization, and the numerical values are found in the inset table in the column labeled “1st”. All ages are in years relative to the starting age of the smallest circumference specimen, Tibia MOR 1189.After starting ages are applied, the next step is nonlinear ordinary least squares (OLS) curve fitting. Sigmoidal growth curves are used to fit the age, circumference data points ( from Eq. (2)). The variables are parameters, and t is the age. In this example we show three parameters , but the curves used here have number of parameters with .

The OLS equations for the conventional approach to modeling dinosaur growth used in previous studies (e.g., Cooper et al., 2008; Lee & Werning, 2008; Woodward et al., 2015) are shown in Eq. (3). The ages are assumed to be resolved into numerical values from the estimation of start ages as an initial step. The OLS function is then minimized numerically using an algorithm such as Levenberg-Marquardt or Newton’s method (Press, 2007; Aster, Borchers & Thurber, 2018). These and similar local optimization algorithms function best when given a reasonable starting set of parameters , which are usually determined through approximate curve fitting approaches (Bates & Watts, 1988; Seber & Wild, 2003; Nocedal & Wright, 2006). With as the number of age, circumference pairs in growth series , the fitting procedure is:

(3)

In this study we use a novel modification of this approach, shown in Eq. (4), in which are treated as independent variables and estimated simultaneously with curve parameters.

(4)

The total number of variables in the OLS function in Eq. (4) is thus , where is the number of parameters in the sigmoid. In the case of the Tyrannosaurus rex species complex growth series shown in Figs. 4 and 5, we have series, and thus the sigmoid models fitted with Eq. (4) will have between 15 and 17 variables. However, the 13 series have with between 6 and 25 CGM, for a total of 198 data points. Since the number of data points greatly exceeds the number of variables, this is well within the capabilities of optimization software to find a solution. This condition remains true so long as the lowest value of is 2 CGM. The growth modeling approach presented here minimizes the sum of least squares between the modeled circumference, and the actual circumference as in Eqs. (3), (4).

In the terminology of statistics, parameters which must be estimated but do not appear in the primary result are known as “nuisance parameters” (Linnik, 2008; Casella & Berger, 2024). In constructing the Tyrannosaurus rex species complex population growth curve, the relative ages of the specimens are considered nuisance parameters, and our treatment of them here matches normal methods used in statistics. For a study focused primarily on relative ages, the curve parameters would instead be nuisance, and the relative ages would be central.

Fitting the curve using the extra parameters has slightly more uncertainty than without. The impact can be roughly gauged using the corrected Akaike information criterion, AICc.

where is the number of data points, is the number of parameters and is the likelihood. If this is evaluated for vs. , the difference in due to adding the nine relative age parameters is 20.1. For comparison, the term in the Trex2 cases here is typically ~1,300, so it is a small effect, about 1.5% of the AICc. Regardless of the cost in uncertainty, we have no alternative—all methods of estimating the relative ages (for example, through a separate “retrocalculation” estimate) would add to the parameter count in the same manner. The increase in AICc due to the extra relative age parameters thus plays no role in model selection as it applies equally to each model.

The argmin function in Eq. (3) is performed by an ordinary least squares nonlinear numerical optimization algorithm which begins with initial values for each parameter and then iteratively improves them. To begin the iteration, initial values (which are often called “guesses”) (Bates & Watts, 1988; Seber & Wild, 2003; Nocedal & Wright, 2006; Press, 2007) or each of the curve parameters and for the variables are obtained by using the least squares clustering algorithm, and a curve fit to the clustered result (Figs. 5, S10–S13). This gives an objective initial guess, and subsequent iterations of the optimization algorithm overcome any possible shortcomings in the initial least squares clustering.

Both theoretical and empirical studies show that some biological growth curves better model the growth of some organisms. There are multiple sigmoidal curves which can be used, each of which have different shapes, corresponding to differences in biologically interesting, derived parameters such as maximum growth rate, when during growth the point of maximum inflection and other factors occur (Tjørve & Tjørve, 2010; Goshu & Koya, 2013; Vrána et al., 2019). Some, like logistic, Gompertz, Richards and von Bertalanffy have long been used in growth rate studies for extant animals (Zullinger et al., 1984; Hernandez-Llamas & Ratkowsky, 2004; Tjørve & Tjørve, 2017a, 2017b), and for dinosaurs, starting with (Chinsamy, 1993).

Different curve families, such as logistic and Gompertz, have various parameterizations with differing numbers of parameters. Our study uses nine different sigmoidal growth curves (Table S3) for each variant to make it more likely that we use a fit which has a shape matching the growth. For example, the shape of the curve at the inflection point, where maximum growth is achieved, can be made symmetric (as with logistic) or not (Myhrvold, 2013). Another important factor is that some curves interact poorly with numerical fitting algorithms, because they can have mathematical singularities or become complex valued for certain parameter values. This is true, for example, for the Richards growth model, which contains many of the other models (logistic, Gompertz and von Bertalanffy) so it would seem ideal, and some authors make that argument (Tjørve & Tjørve, 2017b). But in actual practice numerical regression routines have great trouble with the Richards model so it seldom is chosen as the best fit.

Quadratic and linear non-sigmoidal curves were also applied because they can be useful diagnostics of the fitting process. Functions to be fit take the place of in Eq. (4), and the fitting procedure is repeated for each function as shown in Eq. (5). Each function, along with parameters from Eq. (4) and residuals of the fitting process, are termed the output.

For each variant, we then use the corrected Akaike information criterion AICc for model selection (Burnham & Anderson, 2002), by finding which of the has the minimum value of AICc.

(5)

The minimum value of the corrected AICc provides the best fitting model for use in analysis. However, it is also important to determine the statistical uncertainty for each of the best fit curves by estimating 95% simultaneous confidence bands (CB). In other words, the best fit growth curve should not be used for inference or drawing biological conclusions unless the uncertainty in the growth curve (expressed in the confidence band) is considered. While confidence intervals are about point estimates (i.e., scalar parameter value estimates) a simultaneous confidence band is the region in which (under the assumptions inherent in the regression) there is a stated confidence level (in our case, 95%) of finding the true curve which lies entirely within the band. Note that while confidence intervals are derived from the data, they are only interpreted with respect to the model fit. There is no importance attached to data points falling inside or outside the CB.

In addition to arithmetic fitting, logarithmic fitting was also performed by first transforming the circumference data, taking its natural logarithm, i.e., for two reasons. The first was in case the datasets, like many growth data, are heteroskedastic, so that statistical errors in the model vary as a percentage of the circumference rather than as an absolute error. The second reason was to produce a more balanced distribution of errors; since least squares fitting minimizes the square of the difference between the model and the data, the large size (older) end of the growth curve typically dominates the fitting accuracy. After the logarithmic transformation the data can be fit as normally with similarly log-transformed sigmoidal models (Table S4).

Evaluating compatibility of datasets

All 13 growth series for the Tyrannosaurus rex species complex (represented by either a tibia or femur for each individual and both femur and tibia for BMRP 2006.4.4) are included in dataset Trex1 A, plotted in Fig. 4. Visually, it is apparent that three of the CGM circumference growth series (Tibia BMRP 2002.4.1, Femur BMRP 2006.4.4 and Tibia BMRP 2006.4.4) are much longer than the adjacent series below or above them. The growth series in the Trex1 A dataset were next clustered as shown in Fig. 5 (other variants Figs. S12, S13), to provide a starting point for the growth model. The same anomalous specimens protrude from the bundle of series to the right, and one of them (Tibia BMRP 2006.4.4) also protrudes to the left.

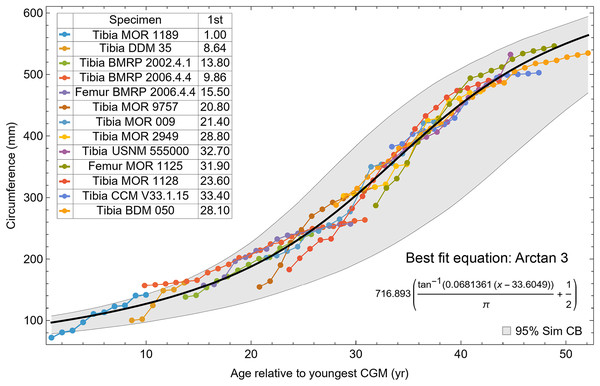

The resulting growth model from the clustered growth series Trex1 A is shown in Fig. 6 with the other variations shown in Figs. S14, S15. 95% confidence bands (CB) were then assigned to each model variant. Since different fits have different lengths for their CB (because of variation in the starting ages for the CGM growth series), the best metric for evaluating the CB size is CB area divided by the age extent of the growth series. Each of the growth variants on the Trex1 dataset had wide 95% simultaneous confidence bands, possibly due to the anomalous three BMRP growth series.

Figure 6: Growth series of dataset Trex1 (includes BMRP specimens), variant A, which incorporates all CGM.

The best fit equation is shown, in this case the arctan 3 function. The age of 1 st CGM for each growth series is estimated with the method of Eq. (4). Problems with the fit are discussed in the text. The plots for variants NoX, NoM, and NoXM are qualitatively similar (see Figs. S14, S15).To investigate, we proceeded with leave-one-out resampling (Arlot & Celisse, 2010; Qin et al., 2021). With 13 growth series, we systematically eliminated one series at a time from each Trex1 variant and then performed the model fit and confidence band calculation on the growth series for the remaining specimens. The result was that removing the femur and tibia of BMRP 2006.4.4 greatly reduced the CB area per length (Table 2).

| Growth series removed | Variant A | Variant NoM | Variant NoX | Variant NoXM | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trex1–MOR 1189 | 120.1 | 124.8 | 125.8 | 125.7 | 496.4 |

| Trex1–DDM 35 | 131.2 | 97.3 | 121.0 | 153.6 | 503.1 |

| Trex1–BMRP 2002.4.1 | 135.8 | 95.9 | 88.9 | 157.6 | 478.2 |

| Trex1–BMRP 2006.4.4 | 45.8 | 72.0 | 98.7 | 149.7 | 366.2 |

| Trex1–MOR 9757 | 132.9 | 96.0 | 87.8 | 164.5 | 481.2 |

| Trex1–MOR 009 | 140.9 | 103.2 | 95.5 | 117.6 | 457.2 |

| Trex1–MOR 2949 | 135.6 | 98.1 | 134.7 | 110.0 | 478.2 |

| Trex1–UNNM 555000 | 136.4 | 93.5 | 89.1 | 111.7 | 430.7 |

| Trex1–MOR 1125 | 127.9 | 95.2 | 88.8 | 113.5 | 425.4 |

| Trex1–MOR 1128 | 87.5 | 103.8 | 87.3 | 112.1 | 390.8 |

| Trex1–CCM V33.1.15 | 142.9 | 97.8 | 86.4 | 103.8 | 430.9 |

| Trex1–BDM 050 | 147.7 | 95.6 | 96.2 | 114.0 | 453.5 |

A second round of leave-one-out resampling showed that removing tibia BMRP 2002.4.1 further improved the model fits (Table 3). These results objectively validate the heuristic observation that these specimens seem out of place in Figs. 4, 5 and S10, S11. Four Trex2 dataset variants result from removal of the BMRP specimens, each comprised of 10 Tyrannosaurus growth series. The growth model for the Trex2 A dataset appears in Fig. 7 and other Trex2 dataset variants in Figs. S16, S17. With the removal of the BMRP specimens, the decrease in the CB area per length is substantial; 127.8 for Trex1, variant A, vs. 45.1 for Trex2, variant A. The total length of the CB is also shorter, 53 years for Trex1 A vs. 43 years for Trex2 A. While each curve represents a best fit to their respective datasets, the utility of the growth model for inference is greatly limited by the larger CB for Trex1.

| Growth series removed | Variant A | Variant NoM | Variant NoX | Variant NoXM | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trex1–BMRP 2006.4.4, MOR 1189 | 55.3 | 115.5 | 98.0 | 114.2 | 383.1 |

| Trex1–BMRP 2006.4.4, DDM 35 | 44.6 | 65.3 | 95.7 | 153.4 | 359.0 |

| Trex1–BMRP 2006.4.4, BMRP 2002.4.1 | 45.6 | 67.7 | 64.5 | 76.3 | 254.1 |

| Trex1–BMRP 2006.4.4, MOR 9757 | 47.5 | 145.0 | 99.8 | 142.8 | 435.0 |

| Trex1–BMRP 2006.4.4, MOR 009 | 53.2 | 66.4 | 118.2 | 156.4 | 394.2 |

| Trex1–BMRP 2006.4.4, MOR 2949 | 46.0 | 71.0 | 92.2 | 145.1 | 354.4 |

| Trex1–BMRP 2006.4.4, UNNM 555000 | 46.9 | 64.5 | 95.5 | 145.9 | 352.9 |

| Trex1–BMRP 2006.4.4, MOR 1125 | 40.8 | 60.0 | 104.1 | 160.6 | 365.5 |

| Trex1–BMRP 2006.4.4, MOR 1128 | 52.7 | 84.6 | 106.3 | 167.1 | 410.7 |

| Trex1–BMRP 2006.4.4, CCM V33.1.15 | 42.6 | 69.0 | 105.1 | 160.5 | 377.2 |

| Trex1–BMRP 2006.4.4, BDM 050 | 68.8 | 91.3 | 106.2 | 142.9 | 409.2 |

Figure 7: Best fit curve to the Trex2 dataset (BMRP specimens removed), A variant.

The methods of Eqs. (4), (5) were used to find the best fitting curve (plotted in black). Each series is plotted in color with the starting ages determined at the same time as the sigmoid function parameters. The extreme value 3 sigmoid function is responsible for the best fit, and the equation for the curve is shown below the graph title. The shaded gray area is the 95% simultaneous CB for the fit determined via nonparametric bootstrap with 2,048 samples.The model fits in the Trex2 dataset are very good. The 95% quantiles of the fit residuals lie within −12.6% to +8.6% for variant A, and similar ranges for other variants (Fig. S18). In addition, when arithmetic and logarithmic plots are compared, the best fits lie within the 95% confidence band of each other (Figs. S19, S20). To further demonstrate the utility of confidence bands, Table 4 compares the difference in CB values for the two datasets and between each of their A and NoXM variants. For Trex1 variant A (see Fig. 6), the CB reaches its maximum high to low extent at the relative age 30.6 and with a high/low ratio of 2.02, at which point the best fit circumference is 312.5 mm. This circumference corresponds to a 6.97 CB ratio in mass. The Trex1 NoXM variant (Fig. S15) has a wider CB extent and thus larger high/low ratios; 2.37 for circumference and 10.72 for mass. This shows the problems inherent in using the Trex1 dataset: its variant A is only good to within a factor of 2 in circumference and 7 in mass in the worst case, while the NoXM variant is even more uncertain.

| Quantity | Attribute | Trex1 | Trex2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | NoXM | A | NoXM | ||

| CB maximum (yr) | Relative age | 30.6 | 18 | 22.3 | 13.9 |

| Circumference (mm) | Best model fit | 312.5 | 291.7 | 332 | 321.5 |

| CB low | 197.3 | 166.1 | 292.5 | 261.8 | |

| CB high | 399.4 | 393.1 | 369.7 | 395.4 | |

| High/low circ ratio | 2.02 | 2.37 | 1.26 | 1.51 | |

| Mass (kg) | Best model fit | 1,541.4 | 1,274.9 | 1,821.1 | 1,666.7 |

| CB low | 434.5 | 270.4 | 1,284.5 | 946.7 | |

| CB high | 3,029.5 | 2,898.4 | 2,447.6 | 2,945.5 | |

| High/low mass ratio | 6.97 | 10.72 | 1.91 | 3.11 | |

The Trex2 dataset has much smaller CB extents and thus smaller ratios. The A variant has a ratio in circumference of 1.26, which converts to a ratio of 1.91 in mass. There is still considerable uncertainty, but that is not surprising for a population. The NoXM variant again is much more uncertain, with a ratio of 1.51 in circumference and 3.11 in mass. These examples show why the uncertainty analysis is important, and why the Trex2 dataset and A variant provide a better basis for inference. The effects of specimen compatibility and of differences between variants are not small for these data.

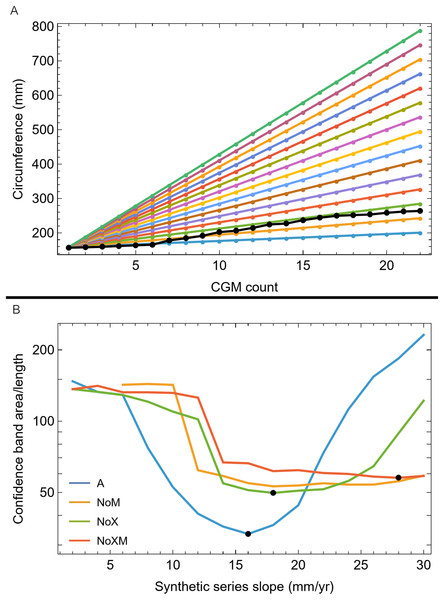

We then investigated which attributes of the removed growth series led to the greatly increased CB using a set of synthetic growth series that modeled growth as a straight line, as approximated by the BMRP 2006.4.4 tibia series. We kept the length the same as the BMRP 2006.4.4 tibia series for each variant and altered the slope from 2 mm/year increase in circumference to 30 mm/year circumference increase. Figure 8A shows these series for variant A, others in Fig. S18. The lower end of the growth rate series is a lower slope (on average) than the BMRP 2006.4.4 tibia series, while the higher end of the slope range is growing much faster than the tibia series.

Figure 8: Synthetic growth series and test results for tibia BMRP 2006.4.4.

(A) The actual, non-synthetic A variant (all CGM) growth series for tibia BMRP 2006.4.4 has 22 CGM in total (black series), and starts with a circumference of 158.5 mm. The colored series plot idealized linear test growth series that begin at the same circumference as the actual, non-synthetic BMRP 2006.4.4 tibia but then increase linearly with slopes between 2 mm/year for the slowest growth case, to 30 mm/year for the fastest growth case. Each synthetic series also has 22 CGM. Similar synthetic series were created for other variants—see Fig. S21. (B) The results of confidence band CB area/length (y-axis) for growth analysis on the synthetic series for each variant (colored curves) as a function the synthetic series growth rate (x-axis) using the Trex2 dataset. In each case the CB area/length reaches a minimum value denoted by a black dot. The minima occur at different values of the growth rate for each variant.Each of these synthetic growth series were added, one at a time, to the Trex2 dataset, and then the growth model was fitted and the 95% simultaneous CB estimated. The results in terms of CB area/length are plotted in Fig. 8B, and in terms of area in Fig. S19. The results of the synthetic growth series analysis show that the CB area and area/length reach a minimum (black points) for each variant. Those are the synthetic growth series and associated slopes that are most compatible with the Trex2 dataset in the sense that adding them would not dramatically increase the CB area or area/length.

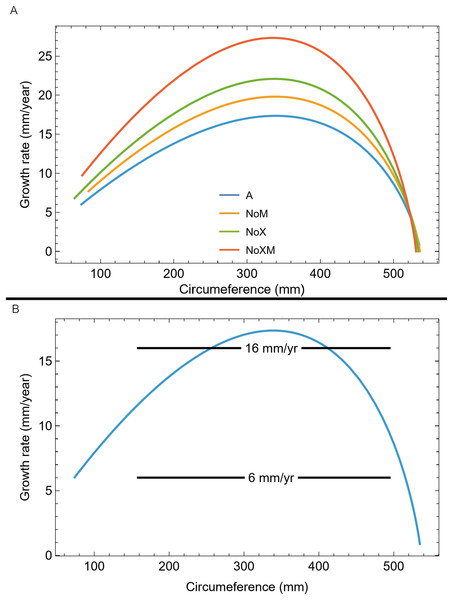

We also plotted the growth rate (derivative of standard sigmoidal growth curve) vs. size (circumference) for all variants of Trex2 (Fig. 9A). In this format the synthetic growth series, having constant slopes, plot as horizontal lines (Fig. 9B). The synthetic series for 14 mm/year (minimum CB area/length) and 16 mm/year (minimum CB area) roughly approximate the curve. The synthetic series for 6 mm/year—which is approximately the average slope of tibia BMRP 2006.4.4—is far from the curve. It is also clear that synthetic series with growth rates in excess of 16 mm/year will also not lie near the curve.

Figure 9: Growth rate as function of cortical growth mark (CGM) circumference for the Trex2 dataset best fit growth model variants.

(A) Growth curves plot size (CGM circumference) vs time, but here size is plotted vs the growth rate (first derivative of size) for all four variants (colored lines). (B) The A variant of the best fit line to Trex2 (blue) and three synthetic growth series (black) are plotted for CGM circumference growth rates of 6, 14 and 16 mm/yr. The synthetic growth series have constant growth rates (slopes) which is the y-coordinate, over a range of circumference values (i.e., a range in the x-coordinate).Myhrvold (2013) introduced the concept of an anaptorythmic taxon, distinguished by having a different growth rate. We demonstrate that in the context of the growth series assigned to the Tyrannosaurus rex species complex, the omitted specimens BMRP 2006.4.4 and BMRP 2002.4.1 qualify as differing in growth rate from the other specimens in the Trex2 dataset but cannot be uniquely identified as comprising a separate taxon. This will be discussed further below.

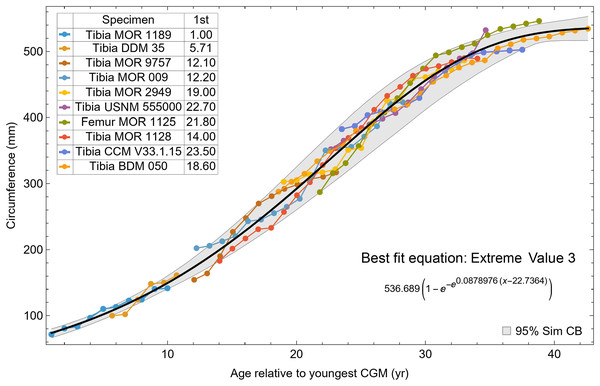

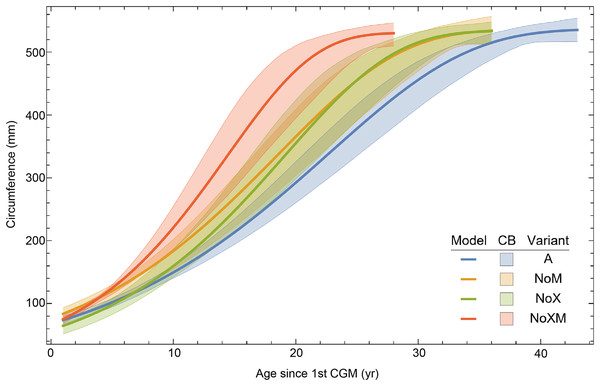

Evaluating model fit across variants

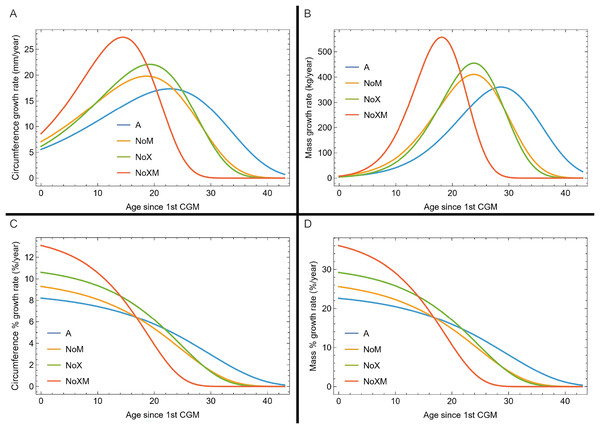

Thus far in our study all four variations on Tyrannosaurus rex species complex growth (A, NoM, NoX, NoXM) have been modeled in parallel; we now turn to comparing them to see what advantages or disadvantages might accrue to each. The best fitting model for each Trex2 variant and their 95% simultaneous CB are plotted in Fig. 10. There is a hierarchy of growth rates because the variants cover approximately the same range in circumference but over different numbers of CGM. The NoXM variant (red) has the fewest points and thus the steepest curve (highest peak growth rate), and the most uncertainty (largest 95% simultaneous CB). The two middle variants, NoX and NoM are similar, and the CB almost completely overlap. This demonstrates the utility of the CB—since the NoX and NoM curves each lie within the CB of the other model, we can infer that the curves are not statistically distinguishable at the 95% level. However, the A and NoXM variants are distinct from each other, and from the NoX/NoM curves. Finally, the A variant has the least steep growth rate and smallest CB.

Figure 10: Growth models for each variant of the Trex2 dataset (excludes BMRP specimens) plotted together with their 95% simultaneous confidence bands CB.

The best fitting models for each variant are shown as solid lines, while the 95% CB is shown as a shaded area.Assessing which variant best models the growth of the Trex2 dataset is complicated. Goodness of fit metrics, such as AICc (Burnham & Anderson, 2002) are generally only recommended for different models (e.g., logistic, Gompertz, von Bertalanffy) applied to the same dataset. In contrast, here the same model is applied to four different variations of the Trex2 dataset. For example, the Trex2 A variant has 152 data points in total while the NoXM variant has only 105. More generally, let the set represent the A variant data points for a given dataset, and , , represent the respective sets for their variants. In that case the sets obey the following equations.

(6) Thus, the growth series in the set also appears in all the other variants. The A set is the superset, the union of all the other variant sets. As stated above, in the case of Trex2 dataset, has 152 CGM points and NoXM has 105 CGM points. Excluded from NoXM are the set of XPL CGM with 22 CGM data points and the set M, due to multiplet CGM, with 27 data points.

Comparing AICc values for growth model fits to each of these sets, using arithmetic (i.e., not log-transformed) data, we find the values shown in line 1 of Table 5. Each value represents the best fitting (lowest AICc) model across all the models attempted. The resulting ΔAICc values cannot find the best model, however, because each has a different number of data points, giving the variant with the lowest data point count an unfair advantage with respect to sum-of-squared residuals.

| Line number | Metric | Data | Point count | Fit | Variant A | Variant NoM | Variant NoX | Variant NoXM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Overall AICc | Trex2 | 152-105 | Arith | 1,258.40 | 1,086.53 | 1,173.61 | 966.48 |

| 2 | Overall ΔAICc | Trex2 | 152-105 | Arith | 291.92 | 120.05 | 207.13 | 0.00 |

| 3 | Overall AICc | Trex2 | 152-105 | Log | −482.38 | −378.47 | −314.34 | −242.49 |

| 4 | Overall ΔAICc | Trex2 | 152-105 | Log | 0.00 | 103.91 | 168.04 | 239.89 |

| 5 | Same pts AICc | NoXM | 105 | Arith | 889.19 | 907.18 | 954.93 | 966.48 |

| 6 | Same pts ΔAICc | NoXM | 105 | Arith | 0.00 | 18.00 | 65.75 | 77.29 |

| 7 | Same pts AICc | NoXM | 105 | Log | −319.95 | −307.71 | −248.08 | −242.49 |

| 8 | Same pts ΔAICc | NoXM | 105 | Log | 0.00 | 12.24 | 71.87 | 77.46 |

| 9 | Same pts AICc | NoM | 127 | Arith | 1,060.12 | 1,086.53 | ||

| 10 | Same pts ΔAICc | NoM | 127 | Arith | 0.00 | 26.40 | ||

| 11 | Same pts AICc | NoM | 127 | Log | −401.04 | −378.47 | ||

| 12 | Same pts ΔAICc | NoM | 127 | Log | 0.00 | 22.57 | ||

| 13 | Same pts AICc | NoX | 130 | Arith | 1,087.43 | 1,173.61 | ||

| 14 | Same pts ΔAICc | NoX | 130 | Arith | 0.00 | 86.18 | ||

| 15 | Same pts AICc | NoX | 130 | Log | −401.72 | −314.34 | ||

| 16 | Same pts ΔAICc | NoX | 130 | Log | 0.00 | 87.38 | ||

| 17 | CB area | Trex2 | 152-105 | Arith | 1,913.64 | 2,329.80 | 2,325.08 | 1,992.75 |

| 18 | CB area | Trex2 | 152-105 | Log | 5.75 | 5.70 | 7.78 | 6.51 |

| 19 | CB area/length | Trex2 | 152-105 | Arith | 45.56 | 66.57 | 66.43 | 73.81 |

| 20 | CB area/length | Trex2 | 152-105 | Log | 0.14 | 0.17 | 0.22 | 0.24 |

To illustrate this, line 2 of Table 5 computes ΔAICc, with the expected result that the lowest AICc occurs for the variant with the smallest number of datapoints, which is NoXM. However, when using growth models fit to log-transformed data (line 3, 4 of Table 5), the smallest AICc now belongs to the A variant despite the disadvantage of more datapoints.

Since AICc is not normally applied to datasets with different numbers of points, we now compute only AICc values for the data points shared across all variants (“same-points AICc”). In Table 5, line 5 computes AICc for the NoXM subset of 105 CGM data points which appear in each of the variants and line 6 finds the ΔAICc values, which show that the A variant is the best model. This is a remarkable finding—even though the growth model fit to the A variant has roughly 50% more data points, it fits the NoXM points better than a model fit to those points alone. Lines 7, 8 in Table 5 show that the A variant is also the best model fit to log-transformed points.

In Table 5 lines 9–12 repeat the same-points AICc procedure but now consider the 127 points from the NoM variant with the 152 points in the A variant. Again, variant A has the lowest same-points AICc score. Lines 13–16 in Table 5 do same-points AICc based on the 130 points in NoX which are shared with variant A, with the same result. Thus, from an AICc model selection standpoint, variant A is always to be preferred for the Trex2 dataset, because it obeys the following conditions.

(7)

In Eq. (7), the notation is the same-points AICc, i.e., the delta AICc value for the best fit model for CGM series variant computed using only the points common to and . Line 17 and 18 in Table 5 show a different metric, the total area of the 95% simultaneous confidence band, and lines 19, 20 the area divided by the length of the CB which shows that variant A has the smallest confidence band.

If XPL or multiplet CGM were truly extraneous or “supernumerary”, then one would not expect variant A to be the best fit to the dataset and to have the smallest confidence band; extra, fallacious, data points should hinder, not improve, the model fits when scoped to the same points. The NoXM variant has errors minimized only on the basis of its points. Meanwhile, the A variant has ~50% additional points, each of which contributes to the sum of squared residuals, which is the basis for OLS regression and also the basis for estimating the log-likelihood which is the main component of AICc. The extra data points apparently influence both the starting ages and parameter values to achieve a fit which has lower AICc despite having more contributions to the sum of squared residuals.

We further tested the null hypothesis, that the XPL or multiplet CGM are extraneous or illusory points. This was done with Monte Carlo simulations creating genuinely extraneous points which randomly fall within the range of the growth series. Random sets and of fictitious CGM representing XPL or multiplet CGM respectively were generated under the assumption that they occur with uniform random placement within the range of the NoXM points. Then a full dataset was constructed with them, plus the NoXM CGM following Eq. (6). These were then fit with a growth model as with Eq. (5), and the same-points AICc calculated for the cases covered in Table 5. Out of 10,000 Monte Carlo trials, only 68 matched the conditions of Eq. (7). The null hypothesis that the XPL or multiplet CGM are random “extra” lines not relevant to the growth series is thus rejected with .

These results, and those in Table 5 provide strong statistical evidence that both XPL and multiplet CGM contribute to growth modeling the Trex2 dataset. Even if one argues that the only valid CGM are those in the NoXM set, the best fit to that set (in terms of least squares or AICc) occurs when models based on the A variant (which includes XPL and multiplet CGM) are used for the regression.

Discussion

Qualitative osteohistology

Primary and secondary tissue organization

In extant vertebrates, relative annual growth rate is generally highest when young and decreases approaching asymptotic size (de Buffrénil, Quilhac & Castanet, 2021). This growth pattern is reflected qualitatively by successively thinner zones of increasingly organized collagen fibers and vascularity from inner to outer cortex (Amprino, 1947; Castanet et al., 1996, 2000; de Margerie, Cubo & Castanet, 2002; de Margerie et al., 2004). In contrast, our datasets show that from early juvenile to late sub adult, the femur and tibia cortex of Tyrannosaurus and Gorgosaurus was generally a plexiform to laminar woven-parallel complex, corresponding to active appositional growth between 25 and 100 microns/day (de Margerie, Cubo & Castanet, 2002; de Buffrénil, Quilhac & Cubo, 2021). More slowly formed parallel-fibered and avascular tissue was only consistently observed in the outermost cortex prior to the lamellar EFS in two of the largest Tyrannosaurus specimens, CCM V33.1.15 and BDM 050, and the larger of the two Gorgosaurus, TMP 1994.012.0602 (Fig. 11).

Figure 11: The external fundamental system (EFS), signaling skeletal maturity, was found in three tyrannosaur specimens from this study.

For each panel, the region of the EFS is bounded by arrows. (A) Tyrannosaurus tibia CCM V33.1.15. (B) Tyrannosaurus tibia BDM 050. (C) Gorgosaurus libratus tibia TMP 1994.012.0602.Most specimens in this study were represented by a tibia and one of them by a femur (MOR 1125). We were able to qualitatively examine the bone tissue of both femur and tibia in the cases of BMRP 2002.4.1, BMRP 2006.4.4, and MOR 9757, and that of the ipsilateral femur, tibia, and fibula for Tyrannosaurus BDM 050. As tyrannosaur fibulae have been used to make life history inferences in previous studies (e.g., Erickson et al., 2004, 2006, 2010; Cullen et al., 2020; Persons, Currie & Erickson, 2020), the intraskeletal sample from BDM 050 provided an opportunity to assess the utility of fibula histology, albeit in a skeletally mature individual (Fig. 12). The fibula of BDM 050 does not display the primary woven-parallel complex observed in its weight-bearing femur and tibia (Figs. 12A–12D). Instead, the fibula cortex (Figs. 12E, 12F) was almost entirely formed of numerous secondary osteon generations, and the avascular lamellar periosteal surface was rarely visible interstitially. Thus, compared to its femur and tibia, the fibula of BDM 050 was uninformative for skeletochronology or assessments of annual growth rate due to its much higher rate of remodeling.

Figure 12: BDM 050 left femur, tibia, and fibula osteohistology.

(A) Femur, imaged in PPL. Box indicates the region of interest in panel B. (B) Anteromedial region of femur cortex. The left half of the image is in PPL and the right half in CPL. Cortex is a plexiform to laminar woven parallel complex throughout, with frequent radial anastomoses (arrow). Dense Haversian remodeling is only present within the innermost cortex near the medullary cavity. (C) Tibia, imaged in PPL. Box indicates the region of interest in panel D. (D) Anterolateral region of tibia cortex, with the left half of the image in PPL and the right half in CPL. Cortex is a plexiform to laminar woven parallel complex throughout but lacks the frequent radial anastomoses observed in the femur. Dense Haversian remodeling is only present within the innermost cortex near the medullary cavity. (E) Fibula, imaged in PPL. The fibula is formed of compact bone from medullary region to outermost cortex. Box indicates the region of interest in panel F. (F) Anterior region of fibula, with the top half of the image in PPL and the bottom half in CPL. Cortex is almost completely comprised of dense Haversian tissue, made particularly evident by birefringent cement lines and isotropic lamellae in CPL (example, purple arrow). Interstitial primary cortex, when present, is avascular and lamellar (example, arrow). CGM, cortical growth mark; PPL, plane polarized light; CPL, circularly polarized light. Cross section orientations: A, anterior; M, medial; P, posterior; L, lateral.Lastly, six individuals (BMRP 2006.4.4, MOR 1125, MOR 2949, MOR 1198, CCM V33.1.15, and BDM 050) possessed unusual compact to cancellous remodeling adjacent to the medullary cavity or endosteally derived bone growing into the medullary cavity. The endosteal tissue of BMRP 2006.4.4 and MOR 1125 are currently under study, but images of the endosteal tissues in the remainder of the specimens are shown in Fig. 13. Exploration of the mechanisms behind the formation of these endosteal tissues is beyond the scope of this project, but we note their presence should there be scientific interest in exploring its occurrence in future studies.

Figure 13: Localized, atypical cortical bone morphology bounds the medullary cavity in some Tyrannosaurus tibiae.

Panels are imaged in CPL on the left and PPL on the right. (A) A region of the innermost cortex and lamellar endosteal layer of CCM V33.1.15 and (B) BDM 050 was remodeled to coarse cancellous bone prior to death. (C) A region of well-vascularized woven-parallel primary tissue formed on the surface of the lamellar endosteal layer (arrow) in MOR 2949 and (D) MOR 1198. Atypical cortical tissues were also observed in MOR 1125 and BMRP 2006.4.4 but are not figured as they are currently under study. PPL, plane polarized light; CPL, circularly polarized light.Double LAG and multiplets

Our ontogenetic dataset confirms previous observations that zonal spacing in Tyrannosaurus femora and tibiae varies from inner to outer cortex (e.g., Cullen et al., 2020; Woodward et al., 2020), rather than predictively decreasing in thickness approaching the growth asymptote. Here we extend this observation to include Gorgosaurus. We identified zones of irregular thickness in early to late-ontogeny as groupings of one or more consecutive zones of woven-parallel complex bounded by relatively thicker zones to either side of the group. In extreme cases, the relatively narrower zones were as thin as one lamina. This variable zonal spacing can result from double LAG or multiplets.

Double LAG are described in the literature as two or more consecutive CGM that merge into fewer lines one or more times over their circumferences and are often considered together as representing a single hiatus event (e.g., Castanet & Baez, 1988; García-Martínez et al., 2011; Nacarino-Meneses, Jordana & Köhler, 2016; Pereyra, 2023). While we did identify instances of double LAG in several individuals (e.g., Fig. 3, Table S1), inconsistency in zonal spacing within our dataset was primarily due to multiplets. Note that in this study double LAG are not considered multiplets but are treated as a single CGM. Although Cullen et al. (2020, 2021) explicitly link double LAG and multiplets, the latter do in fact differ from double LAG in that the CGM remain parallel to one another over their entire circumferences. In extant lissamphibians such as salamanders and toads, annually repeated multiplets, or ‘supernumerary lines’, consist of a relatively thick zone of apposition followed by two closely spaced CGM (Caetano & Castanet, 1993; Castanet et al., 1993, and references therein). Specifically, in the case of alpine salamanders, supernumerary CGM result from two annually occurring stressful events- estivation followed later the same year by hibernation (Caetano & Castanet, 1993). Multiplets are also known to occur at irregular intervals and represent individual annual events. A study validating the annual periodicity of LAG in known-age juvenile loggerhead and Kemp’s ridley sea turtles found that counting each CGM within a multiplet as a single year was the “correct interpretation” of their data, and the variable LAG spacing resulted from a year of “extreme decreased growth” (Snover & Hohn, 2004). Similarly, a study on the water frog Pelophylax interpreted close LAG spacing as resulting from poor growth due to environmental stresses (Socha & Ogielska, 2010).

Multiplets have been noted in earlier studies of Tyrannosaurus and in other non-avialan theropods (e.g., Lee & O’Connor, 2013; Cullen et al., 2014; Zanno et al., 2019; Woodward et al., 2020; Funston & Currie, 2021; Jevnikar, 2022; Jurašeková et al., 2022; Krumenacker, Zanno & Sues, 2022; D’Emic et al., 2023) as well as in some ornithischians (Cullen et al., 2014). Extant studies are often used to support a supernumerary interpretation for multiplets so that they may be considered as annual groupings for the purposes of dinosaur skeletochronology and growth curve modeling. This interpretation (either explicitly or implicitly depending on the study) holds that the multiplets occur over the course of a single “bad year” in which growth stops and starts multiple times, which is the justification for ignoring all but one of the parallel CGM in the sequence.

However, this common treatment of multiplets in dinosaur skeletochronology is problematic for several reasons. First, multiplet assignment is implicitly based on the subjective assessment that the zone width is abnormally thin for its position in the cortical growth series. For example, closely spaced LAG or annuli at the periosteal surface are generally not considered a multiplet and instead categorized as an EFS, while closely spaced LAG or annuli that are bordered by zones which are noticeably wider are likely to be classified as a multiplet.

In effect this is a subjective way of judging which zones appear to be out of keeping with sigmoidal growth. On the other hand, Cullen et al. (2020), p. 11 Supplemental Information) do provide clear criteria for multiplet identification:

“a ‘multiple growth mark’ can frequently be distinguished from multiple distinct growth marks by tracing the marks around their circumference on a full transverse thin-section (17). In most cases, double/multiple growth marks will merge and diverge multiple times over the circumference, whereas a LAG will remain distinct over that circumference.”

However, these criteria are previously used in the literature to define the terms ‘split’ or ‘double LAG’. What is more, most of the LAG and annuli observed in our study do not split or merge but instead are distinct CGM—it is only the adjacent zonal spacing that causes them to be classified as multiplets. Cullen et al. (2020, p. 12 Supplemental Information) apply their criteria to one specimen (BMRP 2006.4.4) which is featured in the present study:

“we have reinterpreted multiple individual LAGs (as described in (20)) to instead be double or multiple growth marks, largely based on examinations of the full sections of the femur and tibia, and tracing the occurrence and splitting/merging of some of these marks across their distribution (Fig. 2C).”