Binge drinking among adolescents: the role of stress, problematic internet use, and emotional regulation

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Ulysses Albuquerque

- Subject Areas

- Epidemiology, Nutrition, Psychiatry and Psychology, Public Health

- Keywords

- Adolescence, Binge drinking, Stress, Problematic internet use, Emotional regulation, Alcohol consumption

- Copyright

- © 2024 Diaz-Moreno et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2024. Binge drinking among adolescents: the role of stress, problematic internet use, and emotional regulation. PeerJ 12:e18479 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.18479

Abstract

Background

Adolescence is a period marked by significant physical, psychological, and emotional changes as youngsters transition into adulthood. During this time, many adolescents consume alcohol, and in some cases, this leads to binge drinking, a behavior associated with various health risks and other problematic behaviors. However, knowledge about binge drinking in this population remains limited. Additionally, many adolescents engage in intensive technology use, which has been linked to mental health issues and substance abuse. Stress is often considered a precursor to both alcohol consumption and problematic internet use. In this context, emotional regulation could serve as a protective factor. Therefore, the present study aimed to examine the relationship between stress, problematic internet use, emotional regulation, and binge drinking among adolescents using structural equation modeling.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was completed by a sample of 876 high school adolescents (63.57% female, mean age 16.86 years). Data were collected using an online survey, which included sociodemographic information and measures of perceived stress, emotional regulation, excessive alcohol consumption, and problematic internet use. Problematic alcohol use was assessed using several questions adapted from the ‘Survey on Drug Use in Secondary Education in Spain’.

Results

Problematic internet use emerged as a mediator between stress and binge drinking, suggesting that stress contributes to the development of problematic internet use, which in turn increases the likelihood of binge drinking. Furthermore, stress was negatively correlated with emotional regulation, indicating that inadequate emotional management may predispose adolescents to problematic internet use and binge drinking. The complex interplay between stress, emotional regulation, problematic internet use, and binge drinking underscores the need for comprehensive interventions targeting these factors among adolescents.

Conclusions

The results provide insights into potential pathways linking stress and binge drinking via problematic internet use and highlight the importance of emotional regulation as a protective mechanism against maladaptive behaviors.

Introduction

In Spain (where the current study was conducted), the purchase and consumption of alcohol are prohibited for individuals under 18 years of age. Nevertheless, 56.6% of students aged 14–18 have consumed alcohol in the last 30 days, with 28.2% of these reporting binge drinking, according to the Survey on Drug Use in Secondary Education in Spain (Ministry of Health of Spain, 2023a). Although interpretations vary in the literature (Hasselgård-Rowe et al., 2022), binge drinking is commonly defined as the consumption of five or more alcoholic standard beverages for men (or four or more for women) during a single occasion in a short period (Patrick & Schulenberg, 2011). Even moderate alcohol consumption during adolescence can lead to a range of health issues (Global Burden of Disease Pediatrics Collaboration et al., 2016) that may persist into adulthood (Patton et al., 2007; Yuen et al., 2020), including metabolic disorders, chronic pain, ischemic heart disease, respiratory conditions, and cancers of the lip and oral cavity (Griswold et al., 2018; Subramaniam et al., 2012). Moreover, excessive alcohol consumption can cause significant neurological and behavioral impairments both in the short-term (Hermens et al., 2013; Lannoy et al., 2019) and long-term (Zilverstand et al., 2018).

Adolescence is a critical period of neural development, characterized by the refinement of neural circuits in brain regions involved in decision-making, problem-solving, and emotional regulation (Petanjek et al., 2011). Consequently, consuming psychoactive substances during this stage can disrupt complex neurological development, increasing adolescents’ propensity for risky decision-making, impulsivity, and emotional reactivity, all of which can adversely impact their overall well-being (Khurana & Romer, 2022; Spear, 2000). Hence, it is imperative to carefully examine binge drinking and its underlying causes, as this behavior poses serious health risks among young individuals.

Adolescence is a critical and dynamic period of vital development. In recent years, societal changes have expanded the onset and endpoint of adolescence (Sawyer et al., 2018). Specifically, the delayed timing of certain social role transitions (e.g., marriage and parenthood) has led to a broader and more inclusive definition of adolescence, spanning 10 to 24 years (Sawyer et al., 2018). This delay in reaching social milestones is significant, as it can seriously impact young people’s development and self-determination (Zimmer-Gembeck & Collins, 2003). Biologically and psychologically, adolescence marks the transition from childhood, characterized by social dependence and immaturity, to adulthood, defined by attaining an independent life (Spear, 2000). During this time, individuals become less reliant on their parents and more autonomous, responding to the challenges of their environment (Wehmeyer & Shogren, 2017). A key feature of this stage is the shift in social support: adolescents increasingly turn to their peers rather than their parents for guidance, with peers becoming their primary source of social influence (Bokhorst, Sumter & Westenberg, 2010; Parent, 2023). This change amplifies the impact of peer influence on adolescents’ behaviors and decisions.

In the context of adolescent binge drinking, peer influences and societal pressures play a critical role. Adolescents are highly susceptible to social comparison driven by the desire and perceived necessity to be liked and accepted among peers (Brown, 2004; Yang & Bradford Brown, 2016). This social dynamic particularly affects alcohol consumption patterns (Leung, Toumbourou & Hemphill, 2014). For instance, Teunissen et al. (2016) found that susceptibility to peer influence moderated the relationship between established drinking patterns among friends and an individual’s subsequent consumption. Longitudinal studies further support the impact of peer influence on future adolescent drinking behaviors. Research has shown that higher levels of social cohesion are linked to an increased likelihood of binge drinking behaviors among adolescents aged 12 to 13 (Martins et al., 2017). A recent meta-analysis also confirms that peer influence significantly contributes to adolescent binge drinking and other substance use behaviors (Ivaniushina & Titkova, 2021).

The influence of peer pressure and social comparison appears to have intensified with the widespread integration of digital technology into daily life (Geusens & Beullens, 2023). Social networking and online gaming, in particular, have radically transformed lifestyles. In Spain, for example, individuals spend an average of 5.45 h per day on the internet, with approximately half of this time spent on smartphones, primarily accessing social media platforms (Kemp, 2023). This technological shift has been particularly pronounced among youth, who tend to use digital devices more extensively than older generations (Instituto Nacional de Estadística, 2023; Kemp, 2023).

These new digital habits have also been linked to various issues arising from inappropriate or excessive smartphone use, including academic underachievement, strained family relationships or friendships, and health complications (Beranuy et al., 2009; Busch & McCarthy, 2021). Some authors have drawn parallels between the mental health challenges experienced by young people due to intensive technology use—such as anxiety, depression, loneliness, and social isolation—and those observed among psychoactive substance users (e.g., Beranuy et al., 2009; Busch & McCarthy, 2021). Indeed, several studies conducted with adolescents have demonstrated an association between problematic mobile device use and the consumption of psychoactive substances, such as tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana, in both Asia and Europe (Ko et al., 2006; Sánchez-Martínez & Otero Puime, 2010; Secades-Villa et al., 2014; Yen et al., 2008), with evidence also linking problematic smartphone use to instances of binge drinking (Muñoz-Miralles et al., 2016).

Moreover, episodes of binge drinking appear to be strongly correlated with time spent on social media platforms (Brunborg, Andreas & Kvaavik, 2017; Brunborg, Skogen & Burdzovic Andreas, 2022; Purba et al., 2023) and the Internet (Mu, Moore & LeWinn, 2015). Binge drinking has also been associated with problematic internet use (PIU) (Andrade et al., 2022; Gámez-Guadix et al., 2015; Müller & Montag, 2017), including internet gaming disorder (IGD) (Moreno et al., 2022). In Spain, the Report on Behavioral Addictions and Other Addictive Disorders (Ministry of Health of Spain, 2023b) found that the prevalence of drunkenness and binge drinking among students with potential PIU was 26.9% and 32.2%, respectively. However, many of these studies have focused on variables such as time spent online (Brunborg, Skogen & Burdzovic Andreas, 2022) or specific activities such as texting (Savolainen et al., 2020). While time spent online is frequently discussed in the literature, it is considered a necessary—but not sufficient—factor for explaining PIU. Thus, problematic use is unlikely if the internet is not used intensively (Chamarro et al., 2020). Other factors, such as underlying psychopathology (Restrepo et al., 2020) and stress (Brand et al., 2016; Kardefelt-Winther, 2014; Liang et al., 2022), are more widely accepted explanations for PIU. Additionally, mobile phone uses examined in studies from the 2000s to the early 2010s (e.g., SMS) differ from more recent practices, which include instant messaging, online social networking, and content browsing (Panova et al., 2020). Despite these findings, the precise mechanisms underlying the relationship between PIU and binge drinking remain poorly understood.

One plausible mechanism to explain binge drinking is stress, given its potential negative impact during adolescence (Charmandari, Tsigos & Chrousos, 2005) and its documented association with PIU. For instance, a meta-analysis by Shannon et al. (2022) demonstrated that problematic social media use (PSMU), a subtype of PIU, was associated with stress. Similarly, Wartberg, Thomasius & Paschke (2021) reported that PSMU was linked to higher levels of perceived stress, and Lissak (2018) reported that excessive screen time was associated with elevated stress levels, both perceived and physiological. Moreover, a longitudinal study conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, based on the transactional stress model, revealed that PIU was commonly used as a coping strategy among university students (Pan, Fu & Zhang, 2024). In contrast, evidence regarding the effect of stress on binge drinking among adolescents remains limited, although indications suggest that generalized consumption (Ballabrera et al., 2023), drunkenness (Liu, Keyes & Li, 2014), and problematic alcohol behaviors (Andretta & McKay, 2019) may be associated with perceived stress.

Another factor related to binge drinking is low levels of emotional regulation. Emotional regulation—an essential psychological skill—undergoes significant changes in adolescence due to the development of associated neural mechanisms (Petanjek et al., 2011; Somerville, Jones & Casey, 2010). Moreover, evidence from a variety of sources suggests that these changes are often dysfunctional or maladaptive until the brain reaches full maturity (Iannattone et al., 2024; Zimmermann & Iwanski, 2014). This developmental imbalance is reflected in the increase in alcohol consumption (Coleman, Crews & Vetreno, 2021) and other health risk behaviors commonly observed during this stage of development (Colmenero-Navarrete, García-Sancho & Salguero, 2022). Similarly, studies have consistently found associations between difficulties in emotional regulation and both alcohol consumption (Estévez et al., 2017; Gámez-Guadix et al., 2015) and the onset of PIU (Hormes, Kearns & Timko, 2014; Van Malderen et al., 2024). Additionally, challenges in emotional regulation are associated with poor stress management (Flores-Kanter, Moretti & Medrano, 2021) and heightened suicidal risk (Gómez-Romero et al., 2020). Maladaptive emotional regulation strategies have also been implicated in emotional disorders such as anxiety and depression, with transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral interventions demonstrating efficacy in alleviating symptoms by enhancing emotional skills (Muñoz-Navarro et al., 2022).

Based on the above arguments, the present study investigated the relationships between stress, PIU, emotional regulation, and binge drinking. More specifically, the study assessed whether stress has a direct relationship with binge drinking and an indirect relationship mediated by PIU. Additionally, this research examined whether emotional regulation mediates the relationship between stress and alcohol consumption in an inverse manner, potentially decreasing alcohol consumption by mitigating the effects of stress.

Method

Participants

A convenience sample of 876 adolescents completed an online survey using non-probabilistic snowball sampling. Of the participants, 63.57% were female, 33.9% were male, and 2.53% identified as non-binary. The gender imbalance in the sample can be attributed to the higher proportion of females studying beyond compulsory education (Ministry of Education, Vocational Training and Sports of Spain, 2021). The mean age of the participants was 16.86 years (SD = 1.22), with ages ranging between 16 and 19 years. In terms of alcohol consumption, 17.9% of participants reported never having consumed or misused alcohol. In contrast, 48.40% engaged in binge drinking between one and four times a month, and 33.70% reported binge drinking four or more times within the preceding month. Among those in the 25th percentile, binge drinking exceeded six occurrences per month. On average, participants reported binge drinking on 3.2 occasions in the past month, with a standard deviation of 3.40. Sample size was estimated using G*Power (version 3.1) software (Faul et al., 2007, 2009), which determined that a minimum of 220 participants was needed for the path analysis.

Instruments

An online survey was designed, incorporating several validated psychometric instruments. The survey included a Sociodemographic and Internet Use Questionnaire to gather information such as gender (female, male, and non-binary), age, and hours spent (daily) on the Internet and playing video games.

Perceived stress was assessed using the abbreviated version of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10; Cohen, Kamarck & Mermelstein, 1983; Spanish version: Remor, 2006). The PSS-10 comprises ten items assessing perceived stress levels over the preceding month. Each item (e.g., “In the last month, how often have you felt nervous or stressed?”) is rated on a scale from 0 (never) to 4 (very often), with total scores ranging from 0 to 40. Higher scores indicate elevated levels of perceived stress. Items 6, 7, 8, and 9 are reverse-scored. The Cronbach’s alpha obtained in the present study demonstrated acceptable internal consistency for the PSS-10 (α = 0.86). This scale is freely available for use by researchers and can be downloaded from the following link without the need for express permission (https://bi.cibersam.es/busqueda-de-instrumentos/ficha?Id=466).

Given that smartphones are the primary method of internet access among youth (Carbonell et al., 2018), problematic internet use was assessed using the Mobile Related Experiences Questionnaire (CERM in its Spanish acronym; see Beranuy et al., 2009). This scale comprises 10 items that assess mobile phone abuse and the problems arising from emotional and communicative dependence on mobile devices. Each item (e.g., “Do you think that life without a mobile phone is boring, empty, and sad?”) is rated on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Almost never) to 4 (Almost always). Total scores range from 10 to 40, with higher scores indicating more pronounced levels of problematic mobile phone use. The Cronbach’s alpha obtained in the present study demonstrated acceptable internal consistency for the CERM (α = 0.80). The authors have permission from the original developers to use this scale.

Emotional regulation was assessed using the repair sub-scale of the Trait Meta-Mood Scale (TMMS-24; Salovey et al., 1995; Spanish version: Fernández-Berrocal, Extremera & Ramos, 2004). The TMMS-24 contains 24 items divided into three dimensions, each comprising eight items: emotional attention, emotional understanding, and emotional regulation (repair). Each item in the emotional regulation subscale (e.g., “I try to have positive thoughts, even if I feel bad”) is rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all agree) to 5 (strongly agree). Total scores range from 8 to 40. Scores below 23 indicate the need to improve regulation, scores between 24 and 35 indicate adequate regulation, and scores above 36 indicate excellent regulation. The Cronbach’s alpha obtained in the present study demonstrated acceptable internal consistency for the emotional regulation subscale (α = 0.84). The authors received permission from the original developers to use this scale.

Problematic alcohol use was evaluated using several questions adapted from the ‘Survey on Drug Use in Secondary Education in Spain -ESTUDES 2023-’ (Ministry of Health of Spain, 2023c). This survey included seven questions assessing the frequency of alcohol consumption and episodes of inebriation over the past week and month. Responses were coded as ordinal variables. Participants indicated their frequency of consumption by selecting from predefined ranges of days (0-day, 1 day, and every weekend) within the past month. An example item is: “In the last 30 days, how many days have you had five or more glasses, pints, or drinks of alcohol on one occasion? For ‘occasion,’ we mean consuming the drinks consecutively or within an interval of approximately 2 h”. This scale, obtained from ESTUDES, is freely available for use by researchers (without permission) (Ministry of Health of Spain, 2023d).

Procedure

The study used an online survey administered through the Google Forms platform, recruiting participants from December 2021 to March 2022. The survey was conducted during tutoring hours with groups of Spanish baccalaureate students, allowing them to respond via smartphone, tablet, or computer. Before beginning the survey, participants were informed about the voluntary nature of their involvement, along with information regarding confidentiality and anonymity. Participants were required to give their prior consent to participate in the study by selecting a ‘Yes/No’ button before proceeding. Upon completing data collection, all responses were securely stored on the principal investigator’s (PI) university server, with stringent measures in place to maintain confidentiality. The data were deidentified to protect participant privacy, and only the PI had access to the stored information. Requests for access to the data were carefully controlled and granted only when necessary for subsequent analysis, with explicit permission required from the PI. The study protocol was approved by the Commission of Ethics in Animal and Human Experimentation (CEEAH) of the Autonomous University of Barcelona (ref. number CEEAH 3850).

Data analysis

The data were analyzed using Stata version 17 for Windows. Descriptive statistics and parametric correlations between variables were calculated. To investigate the factors contributing to binge drinking, a binary logistic regression was conducted using the stepwise method, with odds ratios calculated for the relevant variables. The sample was divided into the top and bottom 25% to convert binge drinking from a nominal variable into a binary variable, allowing for further analysis. Additionally, a path analysis was conducted using maximum likelihood estimation to test the hypothesized model. The paths were determined based on the research questions outlined earlier. To assess the fit of the hypothesized model to the observed data, conventional model fit criteria were applied: Adequate fit was inferred when TLI and CFI > 0.95, RMSEA < 0.06, SRMR < 0.08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999; McDonald & Ho, 2002).

Results

Descriptive and bivariate analyses

Table 1 displays the descriptive statistics and bivariate analyses for the key variables. The following are the mean scores and standard deviations (SD) for each variable: (i) perceived stress on the PSS-10 was 21.33 (out of 40; SD = 5.19), (ii) emotional regulation on the TMMS was 24.04 (out of 40; SD = 6.31), and (iii) PIU on the CERM was 19.04 (out of 40; SD = 4.51). The participants’ mean number of binge drinking episodes was 3.22 per month (SD = 3.40).

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 16.86 | 1.22 | – | ||||

| 2. Stress | 21.33 | 5.19 | 0.008 | – | |||

| 3. Emotional regulation | 24.04 | 6.31 | −0.007 | −0.069 | – | ||

| 4. Problematic internet use | 19.04 | 4.51 | −0.008 | 0.210** | −0.082 | – | |

| 5. Binge drinking | 3.22 | 3.40 | 0.062 | 0.007 | 0.044 | 0.392*** | – |

Bivariate analyses (see Table 1) revealed that perceived stress was positively and moderately correlated with PIU (r = 0.210; p < 0.01). PIU showed a moderate and positive correlation with binge drinking (r = 0.392; p < 0.001).

Logistic regression

Following the correlation analysis, a logistic regression analysis was conducted to predict the likelihood of binge drinking episodes (see Table 2). The model was statistically significant (χ2 = 17.102; p < 0.005), suggesting that emotional regulation acts as a protective factor against binge drinking episodes, with an odds ratio (OR) of 0.89. Conversely, higher levels of PIU emerged as a risk factor, increasing the likelihood of binge drinking. Specifically, the OR of 1.1 indicates that for every unit increase in PIU, participants are 1.1 times more likely to engage in binge drinking episodes. However, while these relationships are statistically significant, the strength of the effects is relatively weak. Therefore, caution is advised when interpreting these results. The model exhibited an accuracy, sensitivity, and precision of 0.782, 0.989, and 0.786, respectively.

| Wald test | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Standard error | Odds ratio | z | Wald statistic | df | p | |

| (Intercept) | 1.631 | 1.377 | 5.111 | 1.185 | 1.404 | 1 | 0.236 |

| Stress | −0.018 | 0.040 | 0.982 | −0.453 | 0.205 | 1 | 0.651 |

| Emotional regulation | −0.115 | 0.044 | 0.891 | −2.637 | 6.954 | 1 | 0.008 |

| Problematic internet use | 0.107 | 0.040 | 1.113 | 2.683 | 7.199 | 1 | 0.007 |

Mediation model

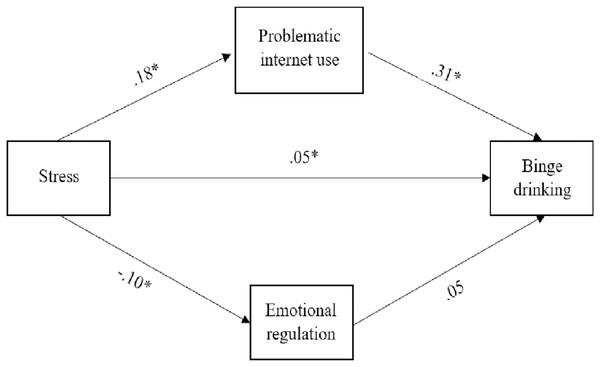

The results of the mediation analysis (see Fig. 1) showed a positive association between stress and binge drinking (β = 0.05; p < 0.05), as well as between stress and PIU (β = 0.18; p < 0.05). Additionally, a negative association was observed between stress and emotional regulation (β = −0.10; p < 0.05). The model demonstrated a good fit to the data (CFI = 0.970; TLI = 0.961; RMSEA = 0.068, 95% CI [0.061–0.075], p < 0.001; SRMR = 0.087).

Figure 1: SEM variables studied.

*p < 0.05.Discussion

The present study explored the relationships between stress, PIU, emotional regulation, and binge drinking. The central aim was to determine whether stress has a direct relationship with binge drinking, as well as an indirect relationship mediated by problematic internet use (PIU). Additionally, the study examined whether emotional regulation mediates the relationship between stress and alcohol consumption in the opposite direction, potentially reducing alcohol intake.

The results revealed a direct but weak association between stress and binge drinking episodes. This finding is consistent with previous studies conducted among college students (Goldstein et al., 2016) and the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic (Verma & Mishra, 2020), both of which identified binge drinking as a coping mechanism for relieving stress. However, evidence regarding this relationship in the adolescent population is scarce. Only a few studies, such as those by Rafanelli, Bonomo & Gostoli (2016) and the narrative review by Dir et al. (2017), have suggested that higher stress levels are linked to binge drinking episodes. In the latter case, this association was only observed among girls, with most reviewed studies focusing on young adults and college students rather than adolescents. These inconclusive data may suggest that stress per se does not directly lead to alcohol consumption or abuse but instead points to the involvement of additional mediating factors in this relationship.

In this regard, the present study’s findings indicate that PIU serves as a mediating factor in the relationship between stress and binge drinking. Specifically, it was found that higher levels of perceived stress are associated with increased PIU, which in turn may contribute to a rise in binge drinking episodes. These results are consistent with those reported in the previous literature, suggesting that stress plays a significant role in the onset and progression of PIU (Wegmann & Brand, 2020; Zhang & Li, 2022). This relationship could be attributed to the fact that adolescents may resort to internet use as a way of coping with perceived stress (Kardefelt-Winther, 2014). Consequently, higher levels of perceived stress could encourage greater internet use, potentially leading to the development of PIU (Liang et al., 2022; Pan, Fu & Zhang, 2024).

Higher PIU levels were linked to an increase in binge drinking episodes, a trend consistent with previous literature. Behavioral addictions, such as PIU, share neurological reward pathways and risk factors with those of psychoactive substance addictions, which could explain their similar behavioral manifestations (e.g., tolerance and withdrawal) (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2015). As a result, the likelihood of both conditions occurring concurrently is increased. Moreover, research has demonstrated that digital environments often share substantial content related to alcohol consumption, including events such as parties, celebrations, and other social gatherings (Cheng et al., 2024). Prolonged or unregulated exposure to these environments may render adolescents more susceptible to alcohol consumption and binge drinking, as they might view these behaviors as typical among their peers. This perception increases the likelihood of mimicking these behaviors in the future, driven by a desire to avoid social exclusion (Caluzzi et al., 2023; Leung, Toumbourou & Hemphill, 2014).

Stress was negatively correlated with emotional regulation, consistent with previous research emphasizing the link between psychological stress and poor emotional regulation (Flores-Kanter, Moretti & Medrano, 2021). Emotional regulation is widely recognized as a key adaptive coping strategy (Skinner et al., 2003). Therefore, when adolescents lack effective emotional regulation mechanisms to cope with stressful situations, they could be more vulnerable to engaging in maladaptive behaviors such as binge drinking and PIU. Over time, reliance on these ineffective coping strategies could increase the risk of developing future psychopathologies if left unchecked (Flores-Kanter, Moretti & Medrano, 2021).

The logistic regression analysis further suggested that emotional regulation could act as a protective factor against binge drinking. Nevertheless, this relationship was not supported by the mediation model, leading to mixed interpretations. Most previous studies have emphasized the importance of emotional regulation as a protective factor against binge drinking (Nolen-Hoeksema, Gilbert & Hilt, 2015; Pedrini et al., 2022) and other psychoactive substance use behaviors (Van Malderen et al., 2024). However, several factors could shed light on the discrepancy found in the present study. One plausible explanation is that deficits in emotional regulation skills may be more pronounced in adolescents, as the brain regions responsible for emotional regulation are still developing during this period (Petanjek et al., 2011) and could be impaired by excessive alcohol consumption. Therefore, adolescents might turn to maladaptive coping mechanisms, such as PIU, to manage stress. In turn, this could lead to excessive alcohol consumption, which might not be effectively controlled due to deficient emotional regulation skills. An alternative interpretation could involve limitations in the tools designed to evaluate emotional regulation. Some instruments may not fully capture the complex facets of emotional regulation, or adolescents may struggle to understand certain items on these scales because they are still developing this ability. In this regard, Ng et al. (2022) pointed out in their systematic review that there are varying conceptualizations of emotional regulation across assessments, which can focus on general emotional regulation ability, specific emotional regulation strategies, or emotional regulation experiences. Moreover, there is insufficient psychometric validation of these instruments for children and adolescent samples, which could contribute to discrepancies such as the one identified in the current study.

Limitations and future directions

While this study provides valuable insights into the relationship between stress, PIU, emotional regulation, and binge drinking among adolescents, several limitations warrant consideration when interpreting our results. First, despite using a relatively large sample of adolescents, the cross-sectional study design precludes the ability to draw causal inferences concerning the relationships among the study variables. Second, our study relied on convenience sampling, with a gender imbalance in our sample (almost two-thirds of participants were female), which limits the generalizability of the findings. Another concern is the use of self-report data, which might have introduced bias. For instance, participants might have underreported information about their alcohol consumption due to the need to give socially desirable responses. Future research should prioritize longitudinal studies with more representative samples to confirm these findings. This approach would provide stronger evidence to better inform the development of preventive strategies for adolescent health.

Conclusions

The present study provides valuable insights into the complex interaction between stress, problematic internet use (PIU), emotional regulation, and binge drinking among adolescents, which could potentially inform the design of effective preventive interventions. The key findings highlight that PIU was a mediator between stress and binge drinking, emphasizing the role of online coping mechanisms in shaping alcohol consumption behavior. Additionally, the negative correlation between stress and emotional regulation highlights the importance of addressing emotional regulation deficits in adolescent health promotion initiatives. Although a direct association between emotional regulation and binge drinking was not observed in the present study, the nuanced nature of this relationship underscores the need for multifaceted interventions targeting stress management, healthy internet habits, and emotional regulation skills. Moreover, the study emphasizes the potential impact of digital environments on adolescent behaviors, indicating the importance of addressing online influences in preventive strategies. Overall, the study significantly advances our understanding of the complex factors influencing adolescent binge drinking and highlights the critical need for comprehensive, tailored interventions aimed at promoting healthier behaviors and well-being among this population.