Today, PeerJ is pleased to publish the work of Dr. Andrew Farke, and his group, in their article “Ontogeny in the tube-crested dinosaur Parasaurolophus (Hadrosauridae) and heterochrony in hadrosaurids”.

This article describes the most complete skeleton yet known from an iconic dinosaur (the hadrosaur, or “duckbilled dinosaur”, Parasaurolophus), with preserved rare skin and beak impressions. The fossil is a rare baby dinosaur, under a year old when it died 75 million years ago. Study of the skeleton revealed that the hadrosaur formed its unusual headgear by expanding its skull bones earlier and for a longer period of time than did its close relatives.

Because of the broad importance of the finding, researchers have made 3D digital scans of the entire skeleton accessible. It is the first time that virtually an entire skeleton has been made available via open access for anyone to use and reuse.

Dr. Farke, lead researcher on the study and corresponding author on the manuscript, received a B.Sc. in Geology from the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology in 2003, and completed his Ph.D. in Anatomical Sciences at Stony Brook University in 2008. He joined the staff at the Alf Museum in June 2008, as Augustyn Family Curator of Paleontology.

He wrote the following guest post, giving us some details concerning the study of the fossil and the reasons why he decided to submit the findings to PeerJ.

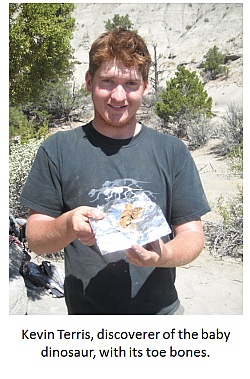

AF: “It’s a long road to travel when a spectacular fossil noses its way out of bedrock and into your museum. In this case, it was the nearly complete skeleton of a baby dinosaur, found by Kevin Terris, a high school student back in 2009. My museum– the Raymond M. Alf Museum of Paleontology–is on the campus of a high school (The Webb Schools), and we take students out in the field with us every year. The first question is, how do we get it back home? Following a flurry of excavation permits (from Bureau of Land Management, Utah, and Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, who manage the land the fossil was found on), two weeks of excavation, and a helicopter flight, the specimen was in a truck on its way to our museum. A year and a half of preparation painstakingly peeled the rock away from the fossil bones, and then it was time to begin the research.

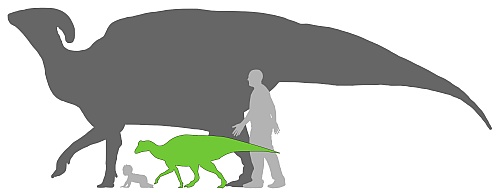

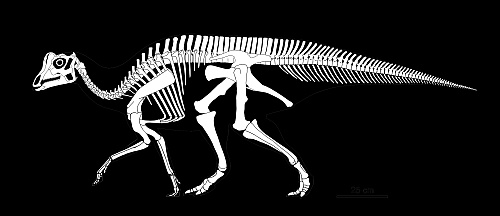

A fantastic crew of researchers joined the project—Derek Chok, Annisa Herrero, and Brandon Scolieri (three high school students from The Webb Schools) as well as Sarah Werning, a paleontologist and bone biologist. We swiftly went to work, trying to extract as much data from the fossil as possible. Detailed study of its anatomy revealed that the six-foot long skeleton belonged to a baby Parasaurolophus—the iconic tube-crested plant-eater that lived throughout western North America around 75 million years ago. Even though the animal was less than a third of its full adult size, it had already sprouted the rudiments of the crest that makes the dinosaur famous. Medical CT scans revealed well-developed nasal passages, which may have been used to trumpet calls to other members of its species at a pitch far higher than the low, booming calls of adults. Perhaps most intriguingly, study of the bone microstructure revealed the animal was probably under a year old when it died. Together, all of these data showed that Parasaurolophus sprouted its crest at a smaller body size (and presumably younger age) than any of its known relatives, and grew its crest for a comparatively longer time. This developmental shift—described as heterochrony—explains in part the bizarre skull anatomy of the animal.

Silhouettes of adult and baby Parasaurolophus, relative to adult and baby humans. Credit: Copyright Scott Hartman (baby dinosaur), Matt Martyniuk (adult dinosaur), Andrew Farke (humans).

Reconstruction of the skeleton of a baby Parasaurolophus.Credit: Copyright Scott Hartman. Usage restrictions: This image is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

.

The whole package added up to something of broad scientific appeal—a baby dinosaur, scarcely a year old when it died, that offers groundbreaking new information on how an iconic prehistoric herbivore grew up. We were faced with the choice that many scientists face. Should we write a short paper—essentially an extended abstract a few pages long—and aim for a “high impact” journal, followed by a longer paper a few months or years or decades later? Based on past experience, this could mean months of shopping the manuscript around, with potentially little payoff in the end. And even if it did get published in that form, the paper would contain only a fraction of the information that other paleontologists wanted to know. Our research hit a topic of hot interest—growth changes in dinosaurs—and I felt a more complete paper would better serve the scientific community, as soon as possible.

So, as lead researcher on the study, I made a big decision. We were going to write the research up once, and we were going to write the most comprehensive, authoritative work possible. The work was a monster tome—46 pages single-spaced, with 11 tables and 28 figures. It covered virtually every aspect of the specimen, from skin to skull to microanatomy of the bones, along with extensive comparisons and interpretation. With this degree of detail, I knew that “conventional” academic publications could take months or years of review, editing and production (along with added charges for color figures). I also knew that I wanted the paper to be open access—every paleontologist, casual dinosaur fan, and even the proud parents, teachers, and classmates of my student co-authors should be able to access the paper with minimal hassle.

PeerJ emerged as the obvious home for our research. I was greatly impressed by the scientific quality of the papers previously published there, as well as the high production standards evidenced in attractive PDFs and a highly functional website. Plus, being a proponent of open access and a volunteer editor for the journal, I wanted to submit my best work to the journal. I wasn’t disappointed. The manuscript submission process was pretty painless, and the editor and reviewers who handled the manuscript gave it a thorough and fair critique. Scarcely 48 hours after submission of the revised manuscript, it was accepted and on the way to publication. The journal staff handling the paper have been responsive and professional—an excellent experience from start to finish.

Farke (top) and co-authors Annisa Herrero, Derek Chok, and Brandon Scolieri press the button to submit their manuscript to PeerJ. Credit: Andrew A. Farke.

Publishing in an open access journal like PeerJ is only one part of getting a fossil specimen out there. Those who make the trek to Claremont, California, can see the fossil on exhibit at the Raymond M. Alf Museum of Paleontology. But, not everyone has the ability to make such a journey. So, we’ve made this fossil the most digitally accessible dinosaur skeleton to date. All of the 3D digital data for the specimen are freely available, through supplementary information published with the article at PeerJ, data archives posted at Figshare, and high-resolution images on MorphoBank. Anyone who has an internet connection and the appropriate software can view the fossil from all angles, exploring the skeleton, plumbing the depths of the animal’s brain, and even testing our interpretations of internal anatomy. We’ve also set up a digital exhibit on the specimen, at www.dinosaurjoe.com. This fossil is part of our world’s biological heritage—and now the world can see it!”