Newcastle-Upon-Tyne transformed into a hotspot for evolutionary science as Northumbria University hosted the EHBEA 2025 Conference. For those unfamiliar with this gathering, the European Human Behaviour and Evolution Association brought together researchers who explore why humans behave the way they do through an evolutionary framework.

Academics presented fascinating research on topics ranging from cultural transmission to risk perception. As an outsider looking in, what made this conference intriguing was how it bridged multiple disciplines – psychology, anthropology, biology, and more – under one theoretical umbrella.

The event featured talks from Petr Tureček on cultural transmission dynamics and established researcher Heidi Colleran challenging conventional notions of fertility. For anyone interested in understanding the evolutionary roots of human behavior, this conference represented a rare opportunity to witness how scientists are decoding the complex interplay between our evolutionary past and present behaviors.

PeerJ is proud to have sponsored an award for the best talk at the conference.

Winners of the PeerJ Awards for the Best Student Talk and Best Poster at the conference went to Emily Jeffries, and Arianna Quinn

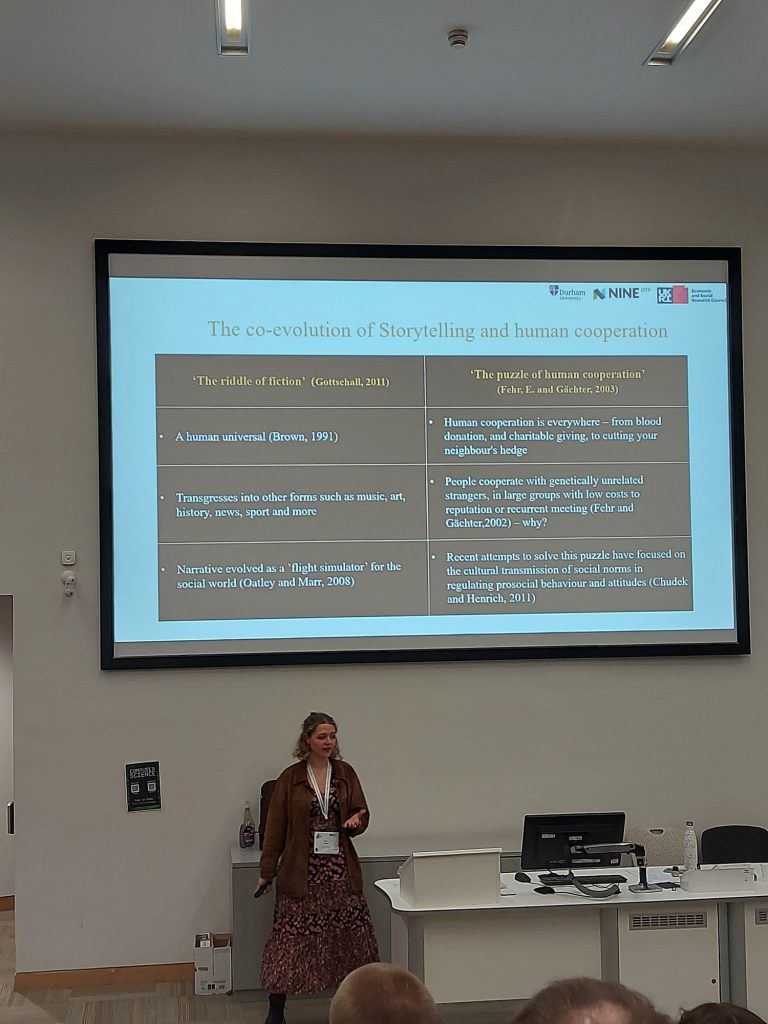

Emily Jeffries – PhD Candidate at Durham University.

Can you tell us a bit about yourself and your research interests?

I am a final year PhD student at Durham University studying the co-evolution of storytelling and cooperation. I am originally from a small town here in the U.K. on the Cheshire-Staffordshire border, not far from the Peak District. I embarked upon a Biology Degree at the University of East Anglia where I investigated cooperation in public goods games. I then shifted disciplines to study for a MA in Socio-Cultural anthropology at Durham University, where I explored the use of storytelling among Irish diaspora. I then combined my interest in these two mysteries, to study for a PhD supervised by Prof. Jamie Tehrani and Dr Sally street.

What first interested you in this field of research?

I have always loved books and stories. Often people ask how I, a self-professed bibliophile, ended up doing a biology degree of all things. I sometimes wonder if my decision to study biology can be correlated with the ridiculous amount of David Attenborough documentaries I watched as a child! This aside, I have always loved the natural world, with a childhood spent roaming around the Peak District. As a young girl, I had quotations by Jane Goodall pinned to my bedroom wall, next to my copious collection of novels. For me, my love of science and stories was always, irrevocably, in tandem.

During my undergrad, I became intrigued by the mystery of human cooperation. However, writing my undergrad thesis on sex differences and group size in cooperative behaviour in public goods games, made me aware of the gap of different cultural perspectives. This encouraged me to shift disciplines to anthropology. During my MA, I was able to pick up my love of stories, researching the role stories played across borders of the Isle of Ireland and England, and the tales Irish diaspora living in England carried within them, understanding the unique ability of stories to create unity. This led me to combine my biological and anthropological interests. My PhD research investigates how storytelling may enhance and stabilise cooperative behaviour, and thus cooperative behaviour increases our desire (or even need) to tell stories. Through this cyclical co-evolution, these two great mysteries of human behaviour, the riddle of fiction and the puzzle of cooperation may allow us to live happily ever after.

Can you briefly explain the research you presented at EHBEA 2025?

I presented the first half of my PhD project. This research examined how prosocial behaviours were viewed within folktales and if prosocial moral messages were more widespread. We hypothesised therefore, that a) cooperative content in stories would be viewed positively compared to anti-social content and b) that stories containing prosocial content would by more commonly found and well-preserved over cultural history.

To determine this, 452 people read 300 Indo-European folktales and commented on the moral messaging and cooperative behaviours found within them. Significantly more stories were categorised as having a prosocial main moral message than an individualistic one, supporting our hypothesis. Additionally, cooperative behaviours were categorised by participants as ‘good’, ‘bad’ or ‘neutral’. Altruism, reciprocity, and helping family were categorised as ‘good’ significantly more often than any other category while individualistic behaviours such as cheating, acting selfishly and harming others were categorised significantly more often as ‘bad’ compared to ‘good’ or ‘neutral’.

Phylogenetic comparative analysis determined if stories categorised as prosocial were gained more than they had been lost over cultural history, supporting the co-evolution of these two human universals. Though there was no overall effect on prosocial content and gain of stories over time, our results showed a directional effect that stories containing anti-social cooperative behaviour of “Harming others”, that were viewed as ‘bad’, were lost less than any other behaviour within the folktales. This suggests that prosocial messages may be transmitted in stories through cautionary tales of what not to do, rather than what to do.

What are your next steps? How will you continue to build on this research?

I plan next to investigate the transmission of prosociality in stories on the evolutionary micro-scale, through artificial transmission chains. By development of a novel corpus design, I hope to determine whether stories are selected over individual generations for their prosociality, and thus a story corpus becomes more cooperative over time. I hope to further assess the co-evolutionary hypothesis through an experimental ethnography using cooperative games following the telling of cooperative folktales in a naturalistic out-of-lab environment involving playing games and communal storytelling around a campfire. I hope by use of more creative methods of experimentation to engage in outreach within the local community to further advance understandings of cultural evolution, cooperation and the origins of storytelling outside of academic circles.

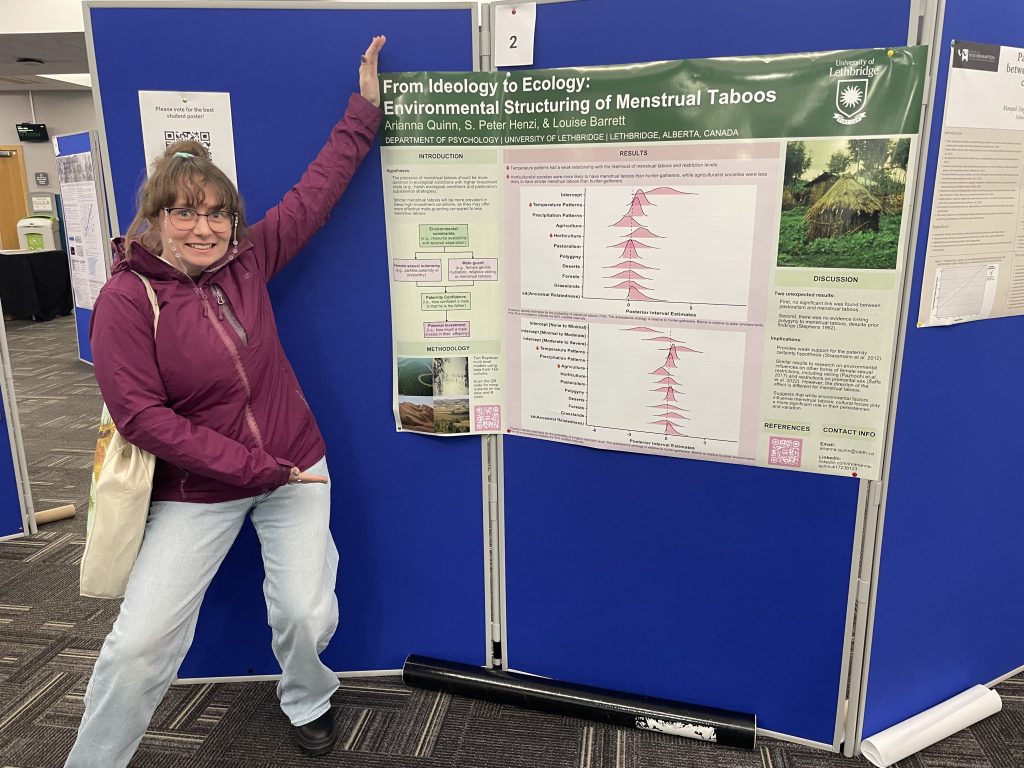

Arianna Quinn, University of Lethbridge

My name is Arianna Quinn, and I am a Master’s student at the University of Lethbridge. Broadly, I’m interested in how human cultural behavior helps people solve the kinds of challenges imposed by biology and ecology — from subsistence strategies to reproductive decision-making. More specifically, I’m fascinated by the ways cultural norms and taboos shape human behavior in ways that may have once been adaptive (or still are), even if they now seem puzzling or restrictive.

My interest in this area began during my undergraduate studies, when I took a course called Human Behavioural Ecology. It introduced me to the idea that cultural behaviors — even seemingly irrational ones — might be shaped by evolutionary pressures and ecological demands. That course was the catalyst: it helped me see human behavior not just as random or purely social, but as part of a larger puzzle influenced by our environment and evolutionary history.

At EHBEA 2025, I presented a portion of my Master’s thesis research, which investigates how menstrual taboos vary across cultures and how those patterns might be shaped by ecological factors. Specifically, I looked at whether variables like temperature and precipitation are associated with the presence and restrictiveness of menstrual taboos. My goal was to explore whether these taboos — often interpreted through purely social or religious lenses — might also be adaptive responses to environmental conditions, particularly those related to resource availability.

Next, I plan to begin a PhD program where I’ll continue to build on this research. I’m especially interested in examining how pathogen stress and the transmission of wealth across generations (inherited wealth) might influence the presence and severity of menstrual taboos. One thing I find particularly important is that while this research explores evolutionary explanations for cultural taboos, it doesn’t aim to justify or validate harmful practices. Instead, it helps us understand where such practices may have originated and why they persist — which is crucial for anyone working to reform or replace them. Understanding the “why” behind cultural behaviours is a powerful tool for both scholars and practitioners.