The 43rd International Sea Turtle Symposium made its historic debut in Ghana from March 22-27, 2025, uniting conservationists worldwide under the banner of “Unity and Collaboration.” Among its highlights: PeerJ awards, recognizing outstanding student researchers through the Archie Carr Student Awards program.

These awards celebrate exceptional biology and conservation presentations, propelling emerging scientists onto the global stage while advancing critical sea turtle protection efforts.

Representatives from 60 countries met at the Mensvic Grand Hotel in Accra, these awards exemplify the symposium’s commitment to nurturing tomorrow’s marine conservation leaders and bridging the gap between cutting-edge research and real-world impact.

Award Winners

Anna Ortega, PhD Candidate at the University of Western Australia & Upwell Turtles

Can you tell us a bit about yourself and your research interests?

My love for research started early—digging through lake mud as a curious kid, trying to make sense of the world around me. I’ve always been drawn to ecology, fascinated by the intricate relationships between living things and their environments. Over time, that fascination has grown into a passion for conservation: supporting and protecting those connections that sustain life.

I’ve been very fortunate to work with a variety of species across the world, gaining insight into diverse ecosystems. Today, my research focuses on using computer modelling to explore ecological questions and inform conservation efforts. By combining data and technology, I aim to better understand the natural world and help safeguard its biodiversity for the future.

What first interested you in this field of research?

I didn’t see the ocean until I was nine, but the moment I did, I was hooked. All it took was a mask and snorkel—suddenly, the sea became my own observation tank, full of wonder and mystery. I threw myself into learning everything I could about this magical underwater world, and was shocked to discover that it wasn’t as untouchable as it seemed. The more I learned, the more I realized how deeply human activity can impact marine ecosystems.

But alongside the bad news, I also discovered something powerful: a community of dedicated scientists and conservationists working to understand and protect the ocean. Their passion and commitment inspired me tremendously. I knew then that I wanted to be one of those people—someone who helps protect what they love through science.

Can you briefly explain the research you presented at ISTS Symposium 43?

This year, I presented research focused on how to give young, captive-reared leatherback turtles the best possible start when they’re released into the wild. Pacific leatherbacks travel vast distances through dynamic ocean conditions, and their ability to grow and reproduce depends on the food they encounter and the temperatures they experience along the way. Using a combination of models, we tracked the environmental conditions a turtle would face and simulated how those conditions would affect its growth and ability to reproduce. We found that the starting point of a turtle’s oceanic journey can significantly influence its experiences, which in turn affects how quickly it grows and reproduces. In fact, turtles leaving some nesting beaches were predicted to never encounter enough food to ever reach reproductive sizes. These insights could help refine conservation release strategies, giving these endangered turtles a better chance of survival and a stronger foundation for thriving in the wild.

What are your next steps? How will you continue to build on this research?

What are your next steps? How will you continue to build on this research?

I’m incredibly fortunate that my work with Upwell Turtles has always directly supported real-world conservation. In just a few weeks, I’ll be joining a group of experts and stakeholders in Panama to discuss additional strategies for protecting the East Pacific leatherback—a sea turtle population that has continued to decline for decades, despite incredible dedication and effort to reduce anthropogenic threats. One promising approach is short-term captive rearing and release, which aims to give young turtles a better chance at survival while more complex challenges, like bycatch, are also being tackled. Our research will play a key role in these conversations, offering science-based insights into when and where hatchlings should be released to maximize their chances of surviving, thriving, and eventually returning to nest as adults. My hope is that these discussions, and the research that follows, will play a pivotal role in restoring the East Pacific leatherback population, and turn the tide toward a more sustainable future for these incredible creatures.

Mildred Alpizar Quezada, masters student at the CIIDIR-Instituto Politecnico Nacional Sinaloa in Mexico

I have been working with sea turtles since 2019. My research interest lies in understanding how incubation temperatures influence embryo development and nest success, as well as identifying the external factors that affect incubation temperatures. Understanding the relationship between the external environment and the microenvironment within the nest can help us make informed decisions during extreme weather events, in order to reduce embryo mortality, increase hatching success, and mitigate other negative impacts on the eggs.

I have been working with sea turtles since 2019. My research interest lies in understanding how incubation temperatures influence embryo development and nest success, as well as identifying the external factors that affect incubation temperatures. Understanding the relationship between the external environment and the microenvironment within the nest can help us make informed decisions during extreme weather events, in order to reduce embryo mortality, increase hatching success, and mitigate other negative impacts on the eggs.

The poster that I presented at the 43rd ISTS in Ghana was entitled “Influence of climatic variables, position, and circadian rhythm on the incubation temperature of leatherback turtles (Dermochelys coriacea) in San Luis de la Loma, Guerrero”. In this study, we evaluated how climatic variables such as solar radiation, precipitation, air temperature, and relative humidity affect incubation temperature, and which variable has the greatest influence. The goal is to better inform nest management strategies such as irrigation, shading with mesh, the use of individual mesh per nest, and other combinations.

We also examined whether temperature readings differ depending on where inside the nest they are taken — at the top, middle, or bottom of the egg clutch — to help improve data collection practices in field camps and ensure more accurate temperature monitoring. Furthermore, we assessed whether the incubation temperature varied between day and night, and finally, we evaluated hatching success and hatchling sex ratios in relation to incubation temperature during the thermosensitive period, to determine whether a female-biased sex ratio — as seen in other species and locations — is occurring here as well.

Key findings of our study:

- Air temperature was the climatic variable with the greatest influence on incubation temperature, followed by relative humidity. Solar radiation did not have a significant effect, likely because leatherback turtles dig the deepest nests among sea turtle species. Precipitation also had no significant influence, which may be due to the dry season in which leatherbacks nest in the Mexican Pacific.

- Significant differences were found depending on where the incubation temperature was recorded inside the nest. The middle of the nest proved to be the most reliable location.

- The circadian rhythm did not significantly affect incubation temperatures — no notable differences were found between day and night temperatures inside the nests.

- The highest hatching success rates (>60%) were observed in nests incubated at 30 °C, and our overall hatching success was higher than what has been previously reported in the literature (50–60%).

- In terms of sex ratios: 66.66% of the nests produced predominantly females, 25% had a balanced 1:1 ratio, and 8.33% produced mostly males. This suggests that this population may also be experiencing increased female production, as has been documented in other sea turtle species.

- Understanding the influence of climatic variables on incubation temperature is essential for making informed decisions about hatchery design and nest management, in order to prevent prolonged exposure to thermal extremes and reduce temperature-related embryo mortality.

- Because data on feminizing, masculinizing, and pivotal temperatures for leatherbacks in Mexican coasts are limited, continued research in this area is critical. In addition to recording incubation temperatures, non-invasive methods should be implemented to determine hatchling sex and better understand sex ratios in the Mexican Pacific.

- Ongoing monitoring of leatherback incubation temperatures is needed. We found that the highest hatching success rates (>75%) occurred at both high (>31 °C) and low (<28 °C) temperatures, while temperatures near the pivotal point resulted in the lowest success (<69%).

Next steps:

I am currently investigating chemical factors that may affect embryo development and hatching success, specifically the concentration of trace elements in leatherback eggs. These elements have been reported to impact sea turtle development. This work forms the basis of my master’s thesis. The poster I presented at ISTS was part of my undergraduate thesis at UAEMex, and for my PhD I hope to evaluate multiple factors influencing embryo development to determine which ones have the greatest effect, and how hatchery management practices can be improved to support conservation success.

I am truly honored to receive the Archie Carr Student Award, which includes the opportunity to publish with PeerJ. This recognition supports my scientific career, and I am thrilled to publish my first paper with you. See you soon with new results — thank you!

Derek Aoki – PhD Candidate at Florida Atlantic University, Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute

Can you tell us a bit about yourself and your research interests?

I grew up in Southern California, USA and always had an affinity for the outdoors (skiing, hiking, sports). I got my bachelor’s degrees in Denver, Colorado, USA and my masters in Freiburg, Germany. I got my start in sea turtle work in 2013 as an intern in Cape Verde (Africa) and have worked in Greece, Costa Rica, and Florida ever since. This set me on my sea turtle trajectory to start a PhD.

What first interested you in this field of research?

I became interested in telemetry because I love making maps and just seeing where animals move and what influences these movements. I worked with loggerhead sea turtles in Cape Verde, but the first time I saw a leatherback was in Florida and they were just so different/unique. I knew that was the species I wanted to study, and the fact little is known about the movements for the aggregation in southeastern Florida made it that much more interesting.

Can you briefly explain the research you presented at ISTS Symposium 43?

The poster I presented outlined our attachment techniques to affix satellite and acoustic transmitters to nesting leatherbacks. We used a combination of stainless-steel and monofilament lines to secure the tags and found monofilament provided a longer tag retention rate for satellite tags. We also experimented with two different attachment sites for acoustic transmitters (pygal process vs medial ridge), which has only been performed once before on nesting leatherbacks.

What are your next steps? How will you continue to build on this research?

Next steps are to fully analyze the tracking data by using space state switch models, pair movements with environmental variables (sea surface temperature, chlorophyl a abundance, salinity), and pair stable isotope analysis with known foraging locations derived from our telemetry tags, which was the topic of my oral presentation at ISTS.

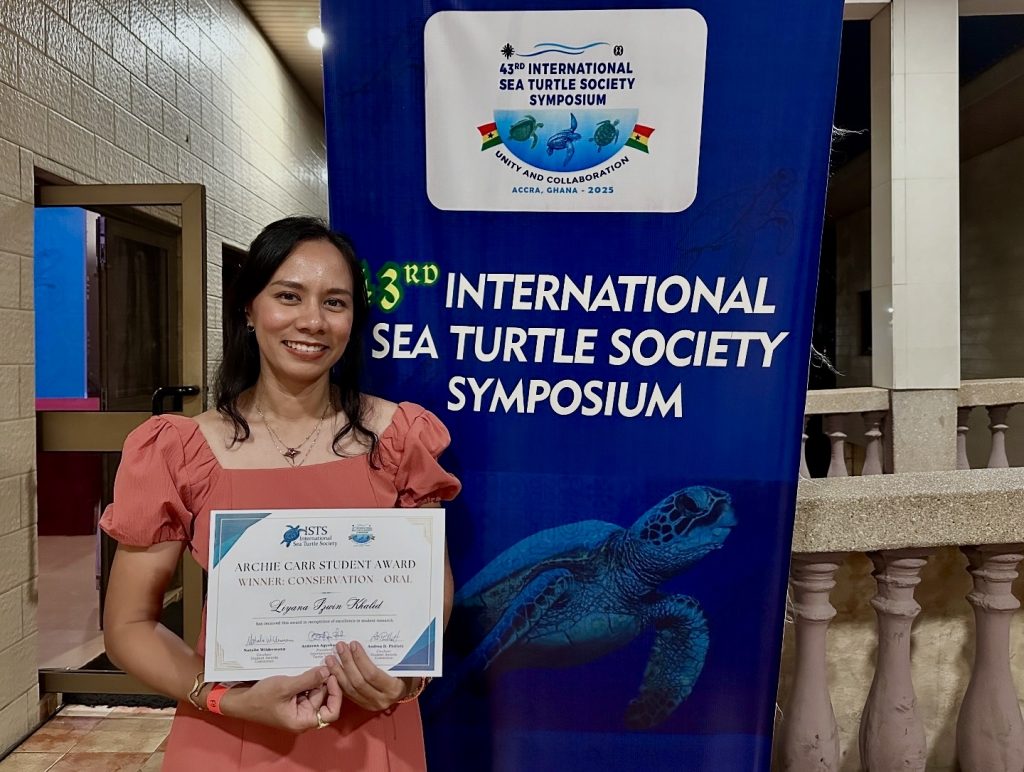

Liyana Izwin Khalid, PhD Candidate at Universiti Malaya, Malaysia and Senior Conservation Officer at the Marine Research Foundation.

Can you tell us a bit about yourself and your research interests?

I’m a Malaysian from the coastal state of Sabah, where the ocean has shaped both my lifestyle and career. I hold a BSc in Marine Science and an MSc in Oceanography, and began a career in environmental consultancy before transitioning into marine conservation.

I’m a Malaysian from the coastal state of Sabah, where the ocean has shaped both my lifestyle and career. I hold a BSc in Marine Science and an MSc in Oceanography, and began a career in environmental consultancy before transitioning into marine conservation.

For the past eight years, I’ve been with the Marine Research Foundation (MRF), a Sabah-based NGO, where I currently serve as Senior Conservation Officer. I oversee initiatives to protect marine ecosystems and species, particularly sea turtles, sharks and rays, with strong focus on addressing threats like bycatch and marine debris.

I lead MRF’s Bycatch Program, working to reduce the bycatch of marine megafauna in Malaysia’s fisheries through science-based, collaborative approaches. A marine conservationist by passion and profession – also a scientist, fisherwoman, and advocate, I’m now pursuing a PhD at Universiti Malaya focused on sustainable management of marine megafauna bycatch in Malaysia. My research aims to address the bycatch of marine megafauna including sea turtles, marine mammals, sharks and rays in Malaysia, using trawl fisheries in Sabah and Sarawak as case studies.

What first interested you in this field of research?

Growing up in a coastal city, I was always intrigued of the ocean around me. When I started scuba diving more than a decade ago, I was overwhelmed by the joy and wonder of exploring the underwater world and I still get overly excited every time I see marine megafauna! Watching sea turtles and sharks swim freely in their natural habitat felt truly magical, cliché as it may sound. But over the years, I also witnessed the growing destruction in our oceans, from turtles entangled in discarded nets to sharks caught in fishing gear. It was heartbreaking and it triggered something in me… I wanted to be part of the solution.

I’m truly fortunate to have found my calling at MRF, which has given me the opportunity to turn my passion into action through meaningful research and conservation focused on marine megafauna. The support and experiences I’ve gained there have deepened my commitment to tackling the critical issue of bycatch in fisheries. This growing passion and confidence, combined with the serendipity of meeting my future PhD supervisor at the right time and place, led me to pursue a PhD. Through it, I hope to contribute to practical, science-based solutions that reduce marine megafauna bycatch and promote sustainable fisheries, while empowering local communities to be part of that change.

Can you briefly explain the research you presented at ISTS Symposium 43?

At ISTS 43, I presented a research titled “Evaluating the effectiveness of Turtle Excluder Devices (TEDs) as a bycatch reduction measure for sea turtles in Sabah, Malaysia”. A TED is a metal frame with vertical bars installed in a trawl net, allowing sea turtles to escape through an opening covered by a flap net, while target catch passes through to the cod end.

The study conducted from 2015-2019, compared catches between TED-equipped and non-TED trawl vessels. Results showed that TEDs did not significantly reduce overall catches, in fact they improved shrimp catch and catch quality, while reducing debris and sorting time. We also tested modified TED designs, including a frameless TED aimed at improving usability. These findings highlight that TEDs offer a practical, low-cost solution for reducing sea turtle bycatch in trawlers without negatively impacting fishers income and livelihoods, supporting sustainable and responsible fisheries management in the country.

What are your next steps? How will you continue to build on this research?

My work with TEDs revealed a larger issue – sharks and rays are also frequently caught in trawl fisheries. However we don’t know where and when does this bycatch happen, or which species are most affected. To address this, we developed GPS-linked time-lapse cameras and deployed them on trawl vessels across Sabah to monitor bycatch patterns. After three years of data collection, we identified key bycatch hotspots and proposed potential management strategies such as time-are closures to the Department of Fisheries Malaysia.

The next step is to expand this research to Sarawak, Sabah’s neighbouring state, where trawl fishing pressure is also high. By extending our monitoring efforts and engaging local stakeholders, we hope to gain a more comprehensive picture of marine megafauna bycatch across a broader geographic area, ultimately strengthening our ability to inform national-level bycatch mitigation strategies and support effective fisheries management throughout Malaysia.