GINMCL: graph isomorphism network-driven modality enhancement and cross-modal consistency learning for multi-modal fake news detection

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Bilal Alatas

- Subject Areas

- Algorithms and Analysis of Algorithms, Artificial Intelligence, Natural Language and Speech, Optimization Theory and Computation, Neural Networks

- Keywords

- Fake news detection, Graph isomorphism network (GIN), Cross-modal consistency learning, Multi-modal fusion

- Copyright

- © 2026 Deng et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2026. GINMCL: graph isomorphism network-driven modality enhancement and cross-modal consistency learning for multi-modal fake news detection. PeerJ Computer Science 12:e3592 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3592

Abstract

Multi-modal fake news detection is a technique designed to identify and classify fake news by integrating information from multiple modalities. However, existing multi-modal fake news detection models have significant limitations in capturing structural information when processing social context. The core issue stems from the reliance on simple linear aggregation or static attention mechanisms in existing graph detection methods, which are inadequate for effectively capturing complex long-distance propagation relationships and multi-layered social network structures. Furthermore, existing multi-modal detection approaches are limited by the feature representations within the respective semantic spaces of each modality. The semantic gaps between modalities lead to misalignment during information fusion, making it difficult to fully achieve modality complementarity. To address these issues, we propose GINMCL, a graph isomorphism network-driven modality enhancement and cross-modal consistency learning method for multi-modal fake news detection. This method builds on the extraction of text and image features by incorporating graph isomorphism networks (GIN) based on the Weisfeiler-Lehman (WL) injective aggregation mechanism to effectively capture both local dependencies and global relationships within social graphs. Modality consistency learning aligns text, image, and social graph information into a shared latent semantic space, enhancing modality correlations. Additionally, to overcome the limitations of traditional methods in modality fusion strategies, we leverage a hard negative contrastive learning mechanism, which softens the penalty on negative samples and optimizes contrastive loss, further improving the accuracy and robustness of the model. We conducted systematic evaluations of GINMCL on the Pheme and Weibo datasets, and experimental results demonstrate that GINMCL outperforms existing methods across all metrics, achieving state-of-the-art performance.

Introduction

In recent years, with the rapid development of social media platforms such as Twitter and Weibo, online social networks have gradually replaced traditional newspapers and magazines as the primary sources of information dissemination. Users freely share their daily lives and express their opinions on social networks, but this also provides opportunities for the widespread dissemination of fake news (Allcott & Gentzkow, 2017). Fake news can easily mislead public opinion, trigger crises of confidence, and disrupt social order (Vosoughi, Roy & Aral, 2018). For example, in August 2023, a widely circulated fake claim stated that the U.S. government was about to ban the use of gas stoves, causing public panic despite no such federal plan. This misinformation misled the public and sparked widespread debate about government intervention. With millions of posts generated daily, the limitations of traditional methods, like manual review, in detecting fake news have become increasingly apparent. Consequently, fake news detection has emerged as an important focus in natural language processing research (Chen et al., 2022).

Early work on fake news detection focused on analyzing single-modal information, either text or images. Text analysis typically relies on traditional machine learning methods, such as decision tree (DT) (Liu et al., 2015; Castillo, Mendoza & Poblete, 2011), Random Forests (Zhou & Zafarani, 2019; Rubin, Chen & Conroy, 2015), or support vector machines (SVM) (Pérez-Rosas et al., 2018; Karimi & Tang, 2019), to learn linguistic style features. Additionally, techniques in traditional deep learning, such as recurrent neural networks (RNN) (Ma et al., 2016), convolutional neural networks (CNN) (Yu et al., 2017; Ma, Gao & Wong, 2018), and long short-term memory (LSTM) networks (Ma, Gao & Wong, 2019), have been used to extract text features for detecting fake news. Image analysis primarily focuses on the content (Qi et al., 2019; Khudeyer & Almoosawi, 2023; Huh et al., 2018) and style (Jin et al., 2016) of images, detecting fake news by identifying processing traces and forged information. However, since modern news often contains text and images, integrating multi-modal information is essential for effectively detecting fake news. More recently, some researchers have started focusing on simultaneously extracting and fusing text and image features to enhance the accuracy of fake news detection (Wang et al., 2018; Singhal et al., 2019, 2020).

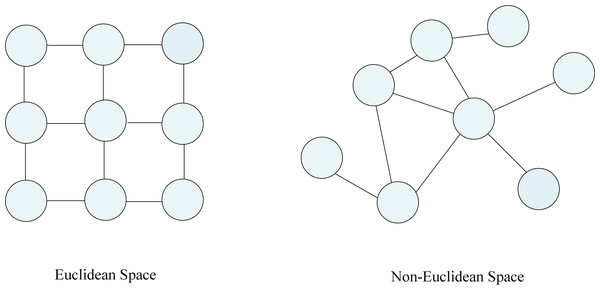

While these methods have been proven effective, they still have notable limitations. Even though these approaches integrate text and image features, they often overlook crucial social context information present in news posts. Social context includes user interactions and comments, which reveal the dissemination patterns of news and user reactions on social networks (Dou et al., 2021). Unlike text and image data, which are structured in Euclidean space, social context information is typically non-Euclidean. To better illustrate the distinction between Euclidean and non-Euclidean data, a comparative diagram is provided in Fig. 1. In contrast, non-Euclidean data is arranged irregularly, making it difficult to process using traditional methods. However, due to the recent advantages of graph neural networks (GNN) in handling non-Euclidean data (Peng et al., 2018), more research has begun focusing on utilizing GNN to model social context information, embedding it into a suitable Euclidean space for better fake news detection. Social context information typically includes user interactions and comment data, which can be modeled as a heterogeneous graph by leveraging GNN based on the relationships between social entities and social information. Existing research often exploits graph convolutional networks (GCN) (Bian et al., 2020; Ren et al., 2020; Kang et al., 2021) or graph attention networks (GAT) (Hu et al., 2021) to aggregate neighbor nodes for analysis, obtaining node representations more conducive to model detection.

Figure 1: Euclidean and non-Euclidean space representations.

However, existing traditional graph-based detection methods rely only on simple aggregation functions (such as mean or weighted aggregation) to gather information from immediate neighbors of the node. This approach makes capturing features from distant nodes challenging, resulting in the loss of extensive information within the graph. Moreover, current research often lacks effective fusion strategies when dealing with uni-modal features from different semantic spaces, such as text, images, and social graphs. This results in challenges when integrating information from these modalities into a unified feature space.

To address these issues, we propose GINMCL, a graph isomorphism network (GIN)-driven modality enhancement and cross-modal consistency learning for multi-modal fake news detection. Based on text and image input features, we leverage GIN to model the social context information of news. GIN utilizes the Weisfeiler-Lehman (WL) algorithm, employing the flexible aggregation mechanism that simulates the injective properties of the WL test. This means that each node and its neighbors are as-signed unique feature representations during aggregation. By recursively applying the aggregation function across multiple layers, GIN captures distant node features, enhancing its ability to distinguish different graph structures. This approach improves the capture of local structures while obtaining deep global features of the social graph structure, leading to a broader range of information representation. Additionally, we leverage cross-modal consistency learning to address the challenge of effectively fusing features from different semantic spaces, such as text, images, and social graphs. This approach aligns and integrates the features from text, images, and social graphs within a shared feature space, effectively reducing the semantic gap between different modalities and enhancing the synergy between them. Furthermore, we also utilize a hard negative sampling strategy to improve alignment accuracy. Selecting negative samples that are most similar to the positive ones and softening the penalty for negative samples makes the model more robust and accurate when handling complex multi-modal data.

In summary, our contributions are as follows:

-

1.

We propose GINMCL, a graph isomorphism network-driven modality enhancement and consistency learning for multi-modal fake news detection. Leveraging the synergy between GIN and cross-modal consistency learning, addressing core challenges in capturing complex social network structures and multi-modal information fusion, providing a novel solution for detection.

-

2.

We are the first to attempt utilizing GIN to social propagation graph modeling. By leveraging the WL injective mechanism, we effectively capture both local dependencies and global relationships in social graph nodes, making significant advancements in modeling long-distance propagation and multi-layered social network structures.

-

3.

We implement consistency learning to effectively align text, images, and social graph information in a latent semantic space, addressing the semantic gap in multi-modal data and significantly enhancing modality coherence and information complementarity. Additionally, we introduce a hard negative sampling contrastive learning mechanism to mitigate the issue of over-penalizing negative samples.

-

4.

We conducted experiments on two widely used datasets—Pheme and Weibo. The results show that GINMCL outperforms existing methods across all metrics, achieving the latest state of the art performance.

The structure of the article is organized as follows: “Related Work” reviews the related work; “Methodology” presents the overall architecture and key components of the GINMCL model in detail; “Experiments” illustrates the experimental design and analyzes the results; “Conclusions” concludes the article and discusses directions for future work. Our work can be found at the following link: https://github.com/lld333/GINMCL.

Related work

Fake news detection

Uni-modal methods

Uni-modal fake news detection models based on text and image information have received widespread attention. For text-based detection, traditional machine learning approaches (Zhou & Zafarani, 2019) focused on extracting semantic features at the lexical level, primarily by analyzing word frequency statistics, along with stylistic feature analysis, such as constructing sentiment lexicons to capture the emotional tone of articles (Pérez-Rosas et al., 2018) or using rhetorical structure theory to identify discourse style features (Karimi & Tang, 2019). With the development of deep learning technologies, models like RNN, LSTM, and GRU utilize hidden layer information to represent news vectors, which are then classified for detection (Ma et al., 2016). Recently, methods proposed like Vroc (Cheng, Nazarian & Bogdan, 2020) have leveraged variational autoencoders (VAE) to encode and generate text embeddings for fake news detection. Meanwhile, the Tsetlin machine (TM) (Bhattarai, Granmo & Jiao, 2022) focuses on the lexical and semantic attributes of the text. At the same time, the method proposed in Liu & Wu (2018) combines recurrent and convolutional neural networks to capture global and local variations in user characteristics along the news propagation path. Meanwhile, image information has also been explored for fake news detection.

Research has found that there are apparent distributional differences between images in real and fake news (Jin et al., 2016). Some methods detect potentially manipulated content by analyzing fraudulent patterns in images, encompassing both content and style (Khudeyer & Almoosawi, 2023). Other approaches explore detecting fake splicing information by learning image self-consistency (Huh et al., 2018). Multi-domain visual neural network (MVNN) (Qi et al., 2019) further combines image frequency and spatial domain information to identify fake images for fake news detection. Although these uni-modal approaches have progressed, they often fail to capture all the essential information from news content, neglecting the interaction between important modalities like images and social context information. This short-coming partially restricts the overall performance of the models.

Multi-modal methods

Based on the application of text and image information, extensive research has further demonstrated that integrating these two modalities significantly improves the effectiveness of fake news detection. Spotfake (Singhal et al., 2019) utilizes the pre-trained models Visual Geometry Group (VGG) and Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) to extract features separately and then concatenates their outputs for fake news detection. Spotfake+ (Singhal et al., 2020) further enhances performance by replacing BERT with XLNET. However, simple concatenation is insufficient to capture deep interactions between modalities fully. It is essential to explore more advanced multi-modal interactions to improve detection performance. To assist in detecting fake news, Event Adversarial Neural Network (EANN) (Wang et al., 2018) designed an event discriminator based on integrating text and image information. Additionally, some studies have begun focusing on the relationships between modalities. Similarity-Aware FakE news detection method (SAFE) (Zhou, Wu & Zafarani, 2020) detects the consistency between text and images and calculates their similarity to spot fake news. Another approach (Jin et al., 2017) applies an attention mechanism to enhance cross-modal understanding and classification. Multi-Modal Co-Attention Network (MCAN) (Wu et al., 2021) stacks multiple attention layers to combine text with image frequency and spatial information, imitating human news reading patterns.

Beyond the deep integration of text and images, exploring additional latent information in social news has filled many gaps in fake news detection and provided abundant inspiration for subsequent researchers. For example, Knowledge-Driven Multi-Modal Graph Convolutional Network (KMGCN) (Wang et al., 2020) constructs a heterogeneous network with text, images, and entity information, using GCN to fuse multi-modal information to generate news representations. Meanwhile, the approach in Hu et al. (2021) builds a heterogeneous graph to compare news entities with external knowledge entities for fake news detection. Research indicates that fully leveraging all available news information is essential for enhancing model performance. However, current multi-modal approaches still face challenges in fully integrating text, image, and social context information, resulting in incomplete information, which limits the overall performance of these models.

Graph neural network

Due to the more random connections between nodes in non-Euclidean space, GNN has recently outperformed other deep learning methods in handling non-Euclidean data, like user propagation patterns in social news.

GCN was first proposed to extend traditional CNN to graph-structured data (Kipf & Welling, 2017). Bi-GCN (Bian et al., 2020) applies GCN to model top-down and bottom-up propagation structures with homogeneous data in fake news detection. As the complexity and heterogeneity of social information in the news grows, research has concentrated on heterogeneous data modelling. For example, the study in Ren et al. (2020) builds a heterogeneous graph incorporating news authors, topics, and text, using pseudo-labels for detection. Similarly, the approach in Kang et al. (2021) develops a knowledge network linking news, domains, reposts, and publishers to generate node embeddings. Deep Neural Network Ensemble Architecture for Social and Textual Context-aware Fake News Detection (DANES) (Truĭcă, Apostol & Karras, 2024) effectively improves detection performance in low-resource scenarios by introducing domain-specific word embeddings and social context embeddings. However, it has limitations in modeling high-order propagation structures and does not explicitly capture cross-modal consistency. Graph Information Enhanced Deep Neural NeTwork Ensemble ArchitecturE for fake news detection (GETAE) (Truĭcă et al., 2025) integrates multiple types of embeddings within a multi-branch architecture, emphasizing the fusion of textual and propagation information. However, it does not adequately address the integration of information across different modalities. User Preference-aware Fake News Detection (UPFD) (Dou et al., 2021) employs GCN to model the exogenous information and incorporates the historical posts of users as input for detection. GCN has achieved initial success in processing graph-structured data, but its node aggregation method typically uses simple weighted averaging, making it challenging to capture complex node dependencies. Although (Hu et al., 2021) enhances the representation of news entities by adaptively weighting neighboring node information based on the GAT (Veličković et al., 2018), its information aggregation method is relatively inflexible, failing to fully capture the complexity of the graph structure. By contrast, GIN (Xu et al., 2019) offers significant advantages, which has been proven to possess extremely high expressive power, particularly when the aggregation and readout functions are injective. Its ability to distinguish different graph structures is as powerful as the WL test. This enables GIN to delve deeper into the underlying information and subtle representations within graph structures, thereby demonstrating superior performance in the task of fake news detection.

Cross-modal consistency learning

Cross-modal consistency learning is primarily achieved by contrastive learning. Contrastive learning, initially popularized in computer vision with methods like Simple framework for Contrastive Learning of visual Representations (SimCLR) (Chen et al., 2020) and Momentum Contrast for unsupervised visual representation learning (MoCo) (He et al., 2020), uses contrastive loss to learn feature representations without labels. This approach has since spread to natural language processing and excelled in multi-modal tasks (Radford et al., 2021). Specifically in fake news detection, contrastive learning aligns data representations across different modalities, enhancing the expressive power of features. In multi-modal fake news detection, the feature differences between text, image, and social context information challenge information fusion. To address this challenge, the study in Wang et al. (2023) proposed a cross-modal contrastive learning method that improves detection accuracy by aligning text and image features. This approach boosts complementarity and consistency across modalities, making it highly effective in multi-modal tasks. Although contrastive learning has been widely applied to text and image bimodal fusion, it has not yet been utilized in the multi-modal fusion of text, images, and social information. Furthermore, traditional methods like SimCLR (Chen et al., 2020) typically retain only positive samples, entirely ignoring negative samples, which may result in insufficient robustness when dealing with complex scenarios. To address this issue, inspired by Robinson et al. (2021), we introduce a hard negative contrastive learning strategy that preserves and reinforces the feature representation of negative samples, thereby further enhancing the discriminative ability of modal.

Methodology

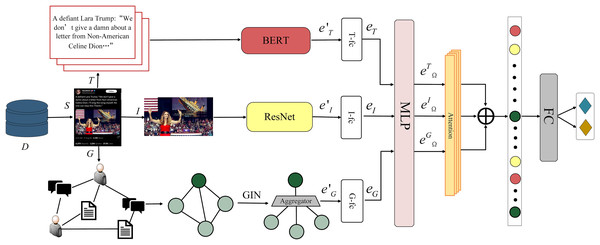

In this section, we propose GINMCL, a graph isomorphism network-driven modality enhancement and cross-modal consistency learning for multi-modal fake news detection. The overall architecture of the model is shown in Fig. 2, and it comprises four components: (1) text and image feature extraction: pre-trained models are used to extract features from text and images. (2) Social context information representation: GIN is leveraged to extract features from social context information, capturing both global and local structural information. (3) Cross-modal consistency learning: a cross-modal consistency learning aligns text, images, and social graph features with hard negative sampling to soften negative penalties. (4) Modality fusion and classification: a cross attention mechanism is incorporated to fuse multi-modal information for classification and detection.

Figure 2: GINMCL model architecture.

Problem definition

We define the fake news detection task as a binary classification problem. Given a news sample , where T represents the textual information, I represents the image information, G represents the social context information, and D is the multi-modal news dataset. The goal is to learn a function that outputs the predicted label , as shown in Eq. (1):

(1) where , indicates fake news, and indicates real news.

Text and image feature extraction

In this work, we represent the text and image associated with each piece of social news as vectors. Since feature extraction for text and images is not the focus of this work, we use pre-trained models to extract the textual and visual features of the news. For each news sample S, the textual feature T and the image feature I are extracted and represented as and , respectively.

Text feature extraction

Textual information is extracted using BERT. BERT (Devlin et al., 2019) is a pre-trained language model based on a bidirectional transformer architecture. It is trained on large-scale unlabeled corpora in an unsupervised manner, achieving a deep understanding of language and demonstrating excellent performance across numerous natural language processing (NLP) downstream tasks. Specifically, given a text T, it is first tokenized into a sequence of words or subwords , where each word or subword is mapped to a prepared token embedding vector . BERT processes these embedding vectors through multiple layers of transformer encoders, generating an aggregated sequence representation of textual features , where represents the hidden state vector of the th word or subword.

In the modality fusion part, since different modality features involve dimensional mapping, the extracted semantic feature embedding needs to be transformed through a fully connected layer to obtain a feature representation with a unified dimension.

Image feature extraction

For the image information I, we use the residual network (ResNet) model to extract visual features. ResNet (He et al., 2016) is a pre-trained model trained on the large-scale ImageNet dataset. It alleviates the vanishing gradient problem in deep networks by introducing residual connections. It also demonstrates outstanding performance in various computer vision tasks and possesses strong feature extraction capabilities. In detail, given an image I, it is first input into the ResNet model, which processes it through multiple layers of convolution and residual blocks to generate a set of regional feature representations , where represents the feature vector of the th region.

To prepare for multi-modal fusion, the initial image embedding is transformed through a fully connected layer to obtain the final visual feature embedding . The final visual feature embedding will be used for alignment and fusion with other modality information.

Social context information representation

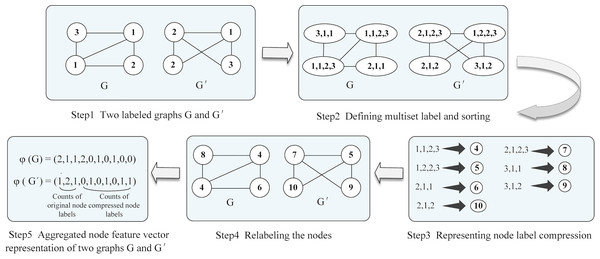

One of the critical challenges in extracting social context information from news is effectively distinguishing different graph structure types. To effectively differentiate between social graph structures and mine deep information from social context, we utilize GIN with the WL algorithm to determine whether the extracted social graphs are topologically equivalent. The WL graph isomorphism test (Shervashidze et al., 2011; Weisfeiler & Leman, 1968) is a powerful algorithm for distinguishing various types of graph structures. The WL algorithm operates iteratively by aggregating the labels of nodes and their neighbors, and then hashing the aggregated labels into unique new labels. Figure 3 illustrates the WL test, which computes the aggregated graph for G and G′. Furthermore, if the node labels differ between the two graphs at any iteration, the algorithm determines that the graphs are non-isomorphic.

Figure 3: Illustration of the WL algorithm aggregating two graphs for isomorphism testing.

GIN leverages this highly expressive aggregation scheme to capture diverse graph structures within social context information effectively. Its injective neighborhood aggregation function can model complex graph structures, making it particularly effective in handling social context information. Specifically, GIN represents post, comment, and user nodes in the social context as a social graph structure, initializes the features of each node, and then extracts global graph features by a message-passing and aggregation process, which are used as model inputs.

Specifically, social context information is represented as a graph , where V is the set of nodes and E is the set of edges. The three different types of nodes include post nodes , comment nodes , and user nodes . The post node feature is initialized using BERT to embed the text content of the post, the comment node feature is initialized using BERT to embed the text content of the comments, while the user node feature is initialized by averaging the embeddings of the post and comments. Each node receives feature information from its neighboring nodes and updates its features by using an aggregation function to sum the features of its neighbors, combined with its own features, as shown in Eq. (2):

(2) where represents the feature of node at the layer, and denotes the set of neighboring nodes of . For example, the neighbors of a user node may include the post node that the user has published and the comment node associated with the user. represents the summation of the features of neighboring nodes. Specifically, for each node, the model aggregates the feature vectors of all its neighboring nodes. For instance, the user node aggregates the features of the associated post node and the comment node . is a learnable scalar used to adjust the weight of the node’s own features during the aggregation process. The node’s own features are weighted by , meaning that the feature aggregation process also considers the node’s own features, adaptively assigning greater or lesser weight to them. The aggregated features are then passed through a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) for nonlinear transformation. MLP denotes a two-layer multi-layer perceptron, with each layer followed by a ReLU activation function.

Accordingly, the multi-level aggregation formula for GIN is given in Eq. (3):

(3) where represents the node feature at the th layer. To balance the trade-off between insufficient information aggregation with too few GIN layers and the difficulty distinguishing node features with too many layers, we set K to 3. Multi-level aggregation enables nodes to incorporate more information from their neighbors, capturing deeper feature representations. The final feature of a user node not only includes information about the posts it directly publishes but also captures information from other users’ comments on these posts, allowing the model to integrate a broader range of information.

After iterations, the final feature of each node already includes information from its -hop neighbors. To obtain the representation of the entire graph, the above node features are aggregated into a global graph feature representation , as shown in Eq. (4):

(4) where the READOUT function generates the entire graph’s embedding given the embeddings of individual nodes. READOUT denotes the graph-level representation extraction operation, which is implemented in this study as the average pooling over all node representations in the graph. A key aspect of graph-level readout is that as the number of iterations increases, the node representations corresponding to subgraph structures become more refined and global. Here, represents the final feature of node at the Kth layer, V is the set of all nodes in the social graph, and is the global feature representation of the social graph. During modality alignment and fusion, is transformed into the social graph embedding using a fully connected layer.

Through these steps, GIN effectively extracts deep-level information from the social graph, enhancing the performance of fake news detection.

Cross-modal consistency learning

Cross-modal consistency constraint

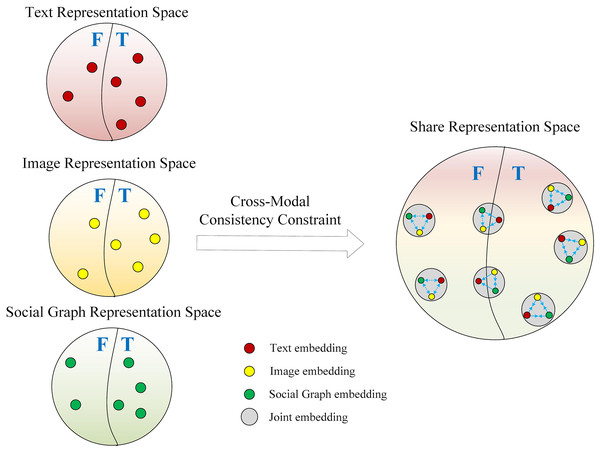

Features from different modalities may have significant semantic gaps. Therefore, we map the uni-modal feature embeddings extracted from text, images, and social graphs into a latent shared space, aligning features across modalities. To overcome the limitation in contrastive learning, where only positive samples are retained, and negative samples are ignored, we introduce a hard negative sampling mechanism that softens the penalty on negative samples.

First, we design a cross-modal consistency constraint to ensure close alignment of the same multi-modal features in the shared latent space. This consistency constraint is tailored for the binary classification task, aiming to predict whether modality features match based on their characteristics. Specifically, if the text embedding , image embedding , and social graph embedding are derived from the same news article S, this set is labeled as 1, indicating a positive sample; otherwise, it is labeled as 0, indicating a negative sample. Figure 4 illustrates this process in detail. The original modality embeddings are mapped to the latent shared space via an MLP, represented as the text embedding , image embedding , and social graph embedding . The specific mapping to the shared space is expressed in Eq. (5):

(5)

Figure 4: Illustration of cross-modal consistency constraint.

We train the model using a consistency loss, as shown in Eq. (6):

(6) where denotes the similarity measure. denotes the cosine similarity function, defined as . In the formula, the numerator terms and represent the similarity of positive samples from the same set of multi-modal news. The denominator represents the sum of the feature embeddings. Where N denotes the total number of samples used for computing the normalized similarity. The fraction compares the similarity of positive sample pairs to the sum of similarities of all samples. By normalizing the similarity of negative samples, the model maximizes the similarity of positive sample pairs while minimizing the similarity of negative sample pairs.

The overall loss is calculated using the negative logarithm, which amplifies the impact of positive sample pairs with lower similarity, encouraging the model to focus more on improving their alignment. By minimizing this loss function, the model gradually learns how to better align the multi-modal features from the same instance within the shared space.

Cross-modal contrastive learning

In the latent shared semantic space , positive sample pairs are defined as multi-modal feature embeddings from the same news instance, such as and , while negative sample pairs are defined as and , where and come from different news instances. The contrastive learning loss function in the shared space can be defined as shown in Eq. (7):

(7) where represents different modalities, specifically image I and social graph G. More precisely, the distance function D denotes the Euclidean distance, defined as . and denote the distances between the positive and negative sample pairs. is the label of the sample pair, with a label of 1 for positive sample pairs and 0 for negative sample pairs. is the margin parameter, which ensures that the distance between negative sample pairs is greater than that between positive sample pairs. N is the total number of samples.

However, this contrastive learning method overlooks negative samples and does not fully accommodate the multi-modal fake news detection task. To enhance the precision of modality alignment, we introduce hard negative sampling. This approach softens the penalty on negative samples, providing more accurate supervision.

Hard negative sample learning

To further enhance the model’s learning effectiveness, we introduce a hard negative sampling mechanism (Robinson et al., 2021). Hard negative samples are those that are similar to positive samples in the feature space but belong to a different category. The contrastive loss function incorporating hard negative samples can be expressed as Eq. (8):

(8) where represents the negative sample embedding from either the image I or social graph G that has the highest similarity to the text embedding . Here, follows the margin definition given in Eq. (7), enforcing that hard negative pairs remain at least farther from the anchor than positive pairs in the shared embedding space. In the shared space, joint training of contrastive learning and consistency loss is used to simultaneously optimize modality alignment and feature discrimination, as expressed in Eq. (9):

(9) where and are used to adjust the importance weights of the two loss functions. They take values in the range , satisfying . The coefficients are determined via a grid search over under the same constraint, selecting the pair yielding the highest validation F1 ( ).

Modality fusion and classification

When incorporating the representations of the three modalities, text, image, and social graph, into the model, we leverage a cross attention mechanism (Vaswani et al., 2017) to optimize the fusion process, as each modality contributes differently to the model. First, we refine the feature representation of each modality through a self-attention mechanism. For instance, for the text modality , we compute the query, key, and value matrices as detailed in Eq. (10):

(10) where are learnable matrices that project the input text feature into query, key, and value vectors for the self-attention mechanism. Specifically, these matrices are defined as trainable parameters during model construction and are optimized jointly with the overall multi-modal objective function. Their gradients are backpropagated from both the self-attention module and the cross-modal learning objectives, enabling the attention projections to adapt to the multi-modal fake news detection task following the standard Transformer attention learning paradigm. Here denotes the dimensionality of the input feature vectors for the text modality, and is the number of attention heads. The self-attention mechanism then computes the self-attention features of the text modality . Initially, the attention scores are derived as shown in Eq. (11):

(11)

Here, the softmax function is used to normalize the attention scores, defined as , where is the th element of the input vector . Then, the outputs from each attention head are concatenated and passed through a linear layer to produce the final self-attention feature representation, as illustrated in Eq. (12):

(12) where is the output linear transformation matrix, and denotes the concatenation of the outputs from all H attention heads. A similar process is followed for the image modality and the social graph modality to obtain their respective self-attention features and . Subsequently, a cross attention mechanism is employed to capture interactions between modalities. For instance, using the text modality as the query and the image modality as the key and value, the enhanced text feature is computed as shown in Eq. (13):

(13)

Similarly, we compute , , , , and . By concatenating these features, we derive the fused multi-modal representation, as shown in Eq. (14):

(14)

To classify the news sample S, we feed the final multi-modal representation into a fully connected layer, which outputs a prediction on whether S is fake news, as illustrated in Eq. (15):

(15) where denotes the predicted probability that the sample S is fake news, where and denote the learnable weight matrix and bias of the fully connected layer, and represents the sigmoid activation function that maps the output to the range . The model is trained using the cross-entropy loss function, as shown in Eq. (16):

(16)

The final loss is shown in Eq. (17):

(17) where is a scaling coefficient that modulates the influence of the classification loss relative to the representation learning loss. It is determined via a grid search over , selecting the value yielding the highest validation F1 ( ).

Experiments

Datasets

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed model, we evaluate it on two widely used real-world datasets: Weibo (Ma et al., 2016) and Pheme (Zubiaga, Liakata & Procter, 2017).

The Weibo dataset is sourced from one of China’s largest social media platforms and is commonly used for fake news detection. It includes numerous Weibo posts categorized as either real or fake news. Real news is verified by Xinhua News Agency, a Chinese authoritative news agency, while fake news is validated by Weibo’s official debunking system, which has a dedicated committee for reviewing suspicious posts.

The Pheme dataset is a multilingual, multi-platform collection of social media rumors, covering data from five major breaking news events. It includes both real and fake news. In our experiments, we exclude single-modal posts that contain only text or images. Each social news item includes text, images, and social context information. Detailed data is presented in Table 1.

| News | Pheme | |

|---|---|---|

| #Real News | 1,428 | 877 |

| #Fake News | 590 | 590 |

| #Images | 2,018 | 1,467 |

| #Users | 894 | 985 |

| #Comments | 7,388 | 4,534 |

Baselines

To thoroughly validate the effectiveness of the proposed model, we compare it with two types of baseline models: uni-modal and multi-modal.

Uni-modal models

The proposed model integrates text, image, and social context for fake news detection. To evaluate its performance, we compare it with the following uni-modal baseline models, which use each modality independently:

CNN-Text (Yu et al., 2017): CNN-Text utilizes news text information as input features. It is a convolutional neural network designed to learn news features for fake news detection. This model extracts features from news text using CNN and then inputs these features into a fully connected layer for classification.

MVNN (Qi et al., 2019): MVNN takes news image information as input features. It is a multi-view neural network that detects fake news by identifying fake images. The model captures high-level semantic information and content structure through spatial domain features and detects image tampering or misleading using frequency domain features. Attention mechanisms are used to fuse information for detecting fake images in social news.

UPFD (Dou et al., 2021): UPFD uses social context information as input features. It is a multi-layer graph neural network model that combines user preferences and external social context information. By encoding user history posts and news text, it captures user preferences and constructs a news propagation graph to extract social features. The generated news representation is then classified to detect fake news.

Multi-modal models

Multi-modal models integrate information from multiple modalities. The selected baseline models are as follows:

EANN (Wang et al., 2018): EANN is an Event Adversarial Neural Network that utilizes Text-CNN to extract textual features and VGG to extract visual features. The model concatenates textual and visual information to create a news representation, which is then fed into an event discriminator for fake news detection.

MCAN (Wu et al., 2021): MCAN is a multi-modal co-attention network that extracts semantic information and visual features from social news. It achieves cross-modal alignment and fusion by stacking multiple layers of co-attention, capturing and enhancing the interdependencies between different modal features for fake news identification.

KMGCN (Wang et al., 2020): KMGCN is a knowledge-driven multi-modal graph convolutional network that models text, visual information, and concept information from knowledge graphs within a unified semantic framework. After feature extraction using graph convolutional networks, a classifier is employed to distinguish between true and fake news.

ATT-RNN (Jin et al., 2017): Recurrent neural network with an attention mechanism (ATT-RNN) utilizes LSTM models to extract textual and social context information. An attention mechanism is used to integrate image information with text features for fake news detection.

MFAN (Zheng et al., 2022): Multi-modal Feature enhanced Attention Networks for rumor detection (MFAN) is a multi-modal feature attention network that uses attention mechanisms to integrate features from text, images, and social graphs for fake news detection.

CLFFRD (Xu et al., 2024): Curriculum Learning and Fine-grained Fusion-driven multimodal Rumor Detection framework (CLFFRD) is a multi-modal rumor detection framework that combines curriculum learning strategies with a fine-grained multi-modal fusion mechanism, and introduces a novel fine-grained fusion strategy.

Implementation details

We encode text into a 512-dimensional embedding using a pre-trained BERT model (Devlin et al., 2019). For the image encoder, images are resized to 224 × 224, and features are extracted using a pre-trained ResNet model (He et al., 2016). The dataset is split into training, validation, and test sets in a 7:1:2 ratio, with consistent splits used across all models. Ablation studies were conducted by removing specific components and retraining the model variants. The experiments used a batch size of 16, a margin parameter of 0.2, 8 attention heads, 20 training rounds, and early stopping to prevent overfitting. The rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation function was employed, and Adam (Kingma & Ba, 2014) was used as the optimizer to find the optimal model parameters.

Evaluation metrics

The evaluation metrics in this work include accuracy, which is used to measure the similarity between predicted fake news and actual fake news. Additionally, precision, recall, and the F1-score are utilized to assess the predictive performance for fake news detection. These evaluation metrics have been widely used in binary classification tasks.

Performance comparison

To evaluate the effectiveness of our multi-modal fake news detection model, we conducted a series of comparative experiments on the Weibo and Pheme datasets. We compared our model with several state-of-the-art methods, including text-based and image-based uni-modal models, multi-modal fusion models, and recent graph neural network models. The results are summarized in Table 2.

| Dataset | Methods | Acc | Prec | Rec | F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNN-Text | 0.716 | 0.702 | 0.724 | 0.717 | |

| MVNN | 0.698 | 0.678 | 0.705 | 0.704 | |

| UPFD | 0.765 | 0.756 | 0.752 | 0.763 | |

| EANN | 0.795 | 0.786 | 0.772 | 0.780 | |

| MCAN | 0.812 | 0.834 | 0.821 | 0.832 | |

| KMGCN | 0.854 | 0.843 | 0.834 | 0.855 | |

| ATT-RNN | 0.802 | 0.789 | 0.821 | 0.820 | |

| MFAN | 0.879 | 0.875 | 0.871 | 0.873 | |

| CLFFRD | 0.890 | 0.893 | 0.887 | 0.900 | |

| GINMCL | 0.918 | 0.912 | 0.901 | 0.904 | |

| Pheme | CNN-Text | 0.721 | 0.708 | 0.687 | 0.694 |

| MVNN | 0.706 | 0.710 | 0.721 | 0.694 | |

| UPFD | 0.753 | 0.746 | 0.741 | 0.750 | |

| EANN | 0.773 | 0.755 | 0.743 | 0.752 | |

| MCAN | 0.796 | 0.804 | 0.812 | 0.810 | |

| KMGCN | 0.844 | 0.832 | 0.820 | 0.812 | |

| ATT-RNN | 0.798 | 0.766 | 0.823 | 0.801 | |

| MFAN | 0.865 | 0.860 | 0.856 | 0.859 | |

| CLFFRD | 0.889 | 0.880 | 0.879 | 0.887 | |

| GINMCL | 0.900 | 0.904 | 0.892 | 0.890 |

Table 2 shows the performance comparison of GINMCL against several state-of-the-art methods on the Weibo and Pheme datasets. The results reveal that GINMCL outperforms all baseline models on both datasets, achieving top results in accuracy (Acc), precision (Prec), recall (Rec), and F1-score (F1). Notably, the model performs consistently well across different datasets, suggesting robust adaptability to various languages and platforms. However, the performance on the Weibo dataset is slightly better than on the Pheme dataset, probably due to the richer social context information available in the Weibo data, which enhances the model’s feature representation.

Specifically, on the Weibo dataset, the GINMCL model achieves a notable improvement of 3.9%, with an accuracy of 91.8%. On the Pheme dataset, it achieves 90.0% accuracy, an improvement of 3.5%. These results demonstrate the model’s strong generalization ability across both datasets. In terms of precision (Prec) and recall (Rec), the model also excels. On Weibo, it reaches 91.2% precision and 90.1% recall, indicating high accuracy and detection rates for fake news. Similarly, on Pheme, the model achieves 90.4% precision and 89.2% recall, surpassing other baseline models. This highlights the model’s effectiveness in balancing detection accuracy and rate.

In contrast, the uni-modal models (CNN-Text, MVNN, UPFD) show significant disadvantages in detecting fake news, with accuracy and other metrics lower compared to multi-modal models. This difference in performance is probably due to the reliance on a single type of information, whether text, image, or social data, which makes accurate fake news detection challenging, as inadequate content extraction limits the model’s detection capabilities. The limited extraction of news content impacts the effectiveness of these models. This highlights the importance of multi-modal information fusion. Multi-modal models (EANN, MCAN, KMGCN, ATT-RNN, MFAN, CLFFRD) outperform uni-modal models by integrating multiple information types, enhancing fake news detection accuracy.

Among these, EANN combines visual and textual data but underperforms compared to other multi-modal approaches. This may be because EANN uses CNN for text extraction, which is less effective than BERT for textual representation, and its fusion approach may not fully leverage multi-modal data, resulting in weaker performance. While MCAN shows improved performance over EANN, it may struggle to effectively differentiate between true and false news due to its lack of social context information and reliance solely on attention mechanisms for fusing text and image features, which may not align in the same semantic space. KMGCN leverages GCN to model graph structures, offering some advantages in capturing graph information. However, it may not match GIN in distinguishing complex graph structures due to GIN’s superior ability to differentiate intricate details within graphs. ATT-RNN, despite integrating text, image, and social context information, underperforms due to its reliance on outdated feature extraction models and a simple concatenation approach that fails to fully exploit modal complementarities. MFAN performs well, coming in second only to GINMCL, showing the benefit of combining text, image, and social information. However, it uses a standard GAT for social graph features, which is less effective than GIN at distinguishing complex graph structures and capturing broader information. CLFFRD may exhibit unstable performance on weakly correlated samples because its fusion strategy primarily relies on predefined entity-object alignment. Additionally, while MFAN employs cross-modal attention for fusing different modalities, it lacks the contrastive learning mechanism present in GINMCL, which reduces semantic discrepancies and enhances alignment across modalities.

Therefore, GINMCL achieves the best results compared to other methods, which can be attributed to the following factors: (1) comprehensive modal information extraction: It simultaneously fuses text, image, and social context multi-modal information as feature inputs and uses BERT and ResNet, providing superior textual and visual representations. (2) Advanced social context extraction: it uses GIN to delve deeply into social context, leveraging its flexible aggregation to capture a broad range of information. (3) Enhanced feature alignment with cross-modal consistency learning: Introducing the cross-modal consistency constraint enables the model to perform better in the alignment and fusion of different modal features, effectively bridging semantic gaps between modalities.

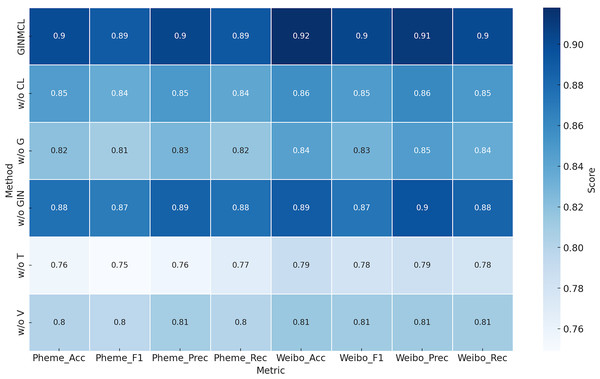

Ablation studies

To further investigate the effectiveness of each component in GINMCL, we conducted the following ablation experiments, as shown in Table 3:

| Dataset | Methods | Acc | Prec | Rec | F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| w/o T | 0.789 | 0.785 | 0.780 | 0.781 | |

| w/o V | 0.814 | 0.812 | 0.810 | 0.811 | |

| w/o G | 0.844 | 0.847 | 0.836 | 0.830 | |

| w/o CL | 0.856 | 0.860 | 0.850 | 0.848 | |

| w/o GIN | 0.889 | 0.895 | 0.884 | 0.873 | |

| Pheme | w/o T | 0.756 | 0.755 | 0.768 | 0.749 |

| w/o V | 0.801 | 0.809 | 0.800 | 0.796 | |

| w/o G | 0.820 | 0.827 | 0.816 | 0.810 | |

| w/o CL | 0.847 | 0.850 | 0.840 | 0.836 | |

| w/o GIN | 0.876 | 0.885 | 0.876 | 0.869 |

As shown in Table 3, we assessed the impact of key components on model performance by conducting experiments where we removed individual components and retrained the model. The variants of GINMCL tested are as follows:

-

1.

w/o T: Remove text features and keep only image and social graph features as input features.

-

2.

w/o V: Remove image features and keep only text and social graph features as input features.

-

3.

w/o G: Delete social graph features and keep only text and image features as input features.

-

4.

w/o GIN: Delete the part of the graph isomorphism network to extract social graph features and use simple graph convolutional modeling social context information as feature input.

-

5.

w/o CL: Remove the cross-modal consistency learning aligned modality part and perform a simple splicing fusion of text, image, and social graph features only.

Table 3 presents the results of the ablation study, showing that all variants perform worse than the original GINMCL model. The performance changes after removing different modules are illustrated in Fig. 5. This verifies the importance of each component. Additionally, the following observations can be made from Table 3:

Figure 5: Performance of the model after removing different modules.

Qualitative analysis

From the qualitative analysis, the following observations can be made:

-

1.

w/o T: Removing text features significantly drops the model’s performance on both the Weibo and Pheme datasets, especially in accuracy and F1-score. This highlights the important role of text features in the model’s decision-making process.

-

2.

w/o V: Excluding image features also leads to a performance decrease, though the impact is less pronounced, particularly on the Weibo dataset. This suggests that text and social graph features are more influential, with image features being slightly less important.

-

3.

w/o G: Omitting social graph features results in a noticeable performance decline, especially on Weibo, where the F1-score falls from 0.904 to 0.830. This indicates that social graph features are vital for contextual understanding and decision-making.

-

4.

w/o GIN: Removing the GIN module causes a performance drop, but less severe than excluding social graph features. This demonstrates GIN’s role in effectively extracting social graph features.

-

5.

w/o CL: Excluding the contrast learning module leads to a reduction in accuracy and F1-scores, though the model remains effective. This shows that contrast learning is important for aligning and integrating features from different modalities.

-

6.

GINMCL: The full model, which includes text, image, social graph features, GIN, and contrast learning, achieves the best performance. This confirms that the combination of these components significantly enhances the model’s effectiveness.

Quantitative analysis

From a quantitative perspective, the following conclusions can be drawn:

-

1.

Text features: Removing text features (w/o T) leads to the most significant performance drop, with a 12.9% decrease in accuracy and 12.3% decrease in F1-score on the Weibo dataset. The Pheme dataset shows a smaller but still notable decrease of over 10%.

-

2.

Image features: Excluding image features (w/o V) results in a relatively minor performance decline across both datasets, suggesting that text and social graph features are more critical for these tasks.

-

3.

Social graph features: Removing social graph features (w/o G) notably impacts performance, especially on the Weibo dataset, highlighting their importance in social media information dissemination and decision-making.

-

4.

Cross-modal consistency learning: Omitting the contrastive learning module (w/o CL) leads to a slight decrease in all metrics, indicating its role in enhancing feature representation and overall model performance.

-

5.

GIN module: Excluding the GIN module results in some performance degradation, suggesting that GIN is more effective than traditional graph convolution methods in modeling social context information.

Discussion

The proposed GINMCL model, which integrates graph isomorphism networks with a cross-modal consistency contrastive learning mechanism, achieves superior performance on two benchmark multimodal fake news datasets. From the experimental results and observations of model behavior, we derive the following insights:

First, the cross-modal consistency modeling mechanism significantly enhances the synergistic understanding among modalities, demonstrating improved robustness especially in cases of semantic mismatch between text and images. Second, the incorporation of social structure strengthens the modeling of information hierarchies by capturing user-level propagation, although its benefits are limited when the propagation graph is sparse or the event granularity is small. Analysis of misclassified samples further reveals limitations of the model in handling modality conflicts and information incompleteness. Additionally, the model’s performance noticeably degrades under incomplete modality inputs, indicating that the current architecture still relies on multimodal completeness. Future work could explore modality availability assessment mechanisms to improve generalization.

Limitations

Although the model performs well overall, it still has several limitations. First, GINMCL is sensitive to the completeness of multimodal inputs; if the image or social graph is missing or of low quality, the model’s performance may degrade significantly. Second, the incorporation of graph neural networks and contrastive learning mechanisms increases the model’s complexity and computational cost to some extent, limiting its suitability for real-time scenarios. Third, the current validation is conducted only on two medium-scale binary classification datasets; generalization tests on multi-label, large-scale, or cross-lingual datasets have not yet been performed, and the model’s universality requires further evaluation. Future work will focus on addressing these issues.

Conclusions

In this work, we propose GINMCL, a graph isomorphism network-driven modality enhancement and cross-modal consistency learning for multi-modal fake news detection. Building on the extraction of text and image features, GINMCL employs GIN to model social context information, using the WL algorithm to capture high-order structural information. This enables a more comprehensive representation of multi-modal features and a finer expression of news propagation patterns. Additionally, we introduce a cross-modal consistency learning mechanism to effectively align the features of text, images, and social graphs, ensuring precise alignment of the three modalities within a shared space. To further enhance alignment accuracy, we utilize a hard negative sampling strategy that softens penalties on negative samples, allowing the model to capture more reliable multi-modal representations. Experiments on the Pheme and Weibo datasets show that GINMCL surpasses existing methods across multiple metrics, achieving state-of-the-art performance on both datasets.

However, the generalization capability of current methods across datasets needs further validation, particularly in different cultural and linguistic contexts. Future research could focus on testing the model’s generalization through cross-cultural and cross-linguistic datasets, and fine-tuning it based on the specific characteristics of news dissemination in diverse cultural settings. Moreover, incorporating emerging technologies like large-scale pre-trained models and reinforcement learning could further boost the model’s effectiveness in real-world applications.

Although this study focuses on high-performance fake news detection, we acknowledge that detection is only the first step. In future work, we aim to explore how to effectively integrate detection results with social network intervention strategies, thereby enabling a closed-loop pipeline from detection to control. For instance, leveraging the credibility scores and propagation structure information output by GINMCL, we can infer and attenuate potential dissemination paths, develop community-based immunization strategies, and design real-time intervention mechanisms. In addition, we plan to build an end-to-end “detection–response” system framework to provide deployable and practical tools for news platforms.