Prompt-guided synthetic data generation to mitigate domain shift in periapical lesion detection

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Jyotismita Chaki

- Subject Areas

- Algorithms and Analysis of Algorithms, Artificial Intelligence, Computer Vision, Data Mining and Machine Learning, Neural Networks

- Keywords

- Synthetic data generation, Domain shift, Data drift, Periapical lesion detection, Deep learning

- Copyright

- © 2026 Özüdoğru et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2026. Prompt-guided synthetic data generation to mitigate domain shift in periapical lesion detection. PeerJ Computer Science 12:e3577 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3577

Abstract

Objectives

Domain shift—the mismatch between training and deployment distributions—degrades deep learning at inference. Vision–language foundation models (VLMs) like ChatGPT-4o generalize out-of-distribution and enable controllable image-to-image synthesis, but direct clinical use is costly and, when closed-source, raises privacy concerns. We instead use a VLM to guide synthetic data generation, strengthening smaller deployable detectors without task-specific retraining—a controllable substitute for generative adversarial network (GAN)/diffusion augmentation, which typically requires large domain-specific datasets and unstable training. We use panoramic radiographs to compare a prompt-guided approach with an expert-guided classical image-processing baseline under morphology/size shift.

Methods

A dataset of 196 panoramic radiographs (145 annotated, 51 healthy) was used. We implemented two transparent augmentation pipelines: (i) Expert-Guided Synthesis (EGS), where clinicians delineated lesion masks that were procedurally rendered (noise-based texture, intensity modulation, edge blending); and (ii) Prompt-Guided Lesion Synthesis (PGLS), where clinicians specified lesion attributes via text prompts (size, shape, margin sharpness, contrast, location) and ChatGPT-4o produced parameterized image-to-image edits. A You Only Look Once (YOLO)10 detector was trained under three regimes (Real-only, Real+EGS, Real+PGLS) and evaluated with five-fold cross-validation and size-stratified reporting (small/medium/large).

Results

Baseline (Real-only): mean Average Precision (mAP)@0.5 0.47, mAP@[0.5:0.95] 0.22, Recall 0.47. Size-stratified baselines: small—0.30/0.085/0.27; medium—0.58/0.26/0.50; large—0.46/0.20/0.49. Both synthetic strategies improved robustness; PGLS consistently exceeded EGS. Overall, EGS 0.50/0.25/0.52 (+6.4%/+13.6%/+10.6%), PGLS 0.51/0.26/0.53 (+8.5%/+18.2%/+12.8%). Largest gains were in small and large: small 0.36/0.120/0.33 (EGS) vs. 0.39/0.130/0.35 (PGLS) = +20.0%/+41.2%/+22.2% and +30.0%/+52.9%/+29.6%; large 0.51/0.235/0.56 vs. 0.52/0.240/0.57 = +10.9%/+17.5%/+14.3% and +13.0%/+20.0%/+16.3%.

Conclusions

Both prompt-guided and expert-guided synthesis improved resilience to morphology shift. PGLS yielded greater gains, reflecting flexible natural-language control while avoiding GAN/diffusion data and stability burdens. Clinically, higher small-lesion recall lowers missed early apical periodontitis, and higher mAP@[0.5:0.95] tightens localization, curbing false positives and unnecessary follow-ups. Because PGLS uses auditable prompts/edits, it extends to other shifts (e.g., device or artifact) and strengthens smaller, deployable detectors for more consistent accuracy across sites.

Introduction

Apical periodontitis (AP) is an inflammation of the periapical tissues caused by root canal infection and a major source of tooth morbidity worldwide (Siqueira et al., 2020; Tibúrcio-Machado et al., 2021). Panoramic radiographs (PR) are the first-line test because they are accessible and low-dose, but their 2-D projection misses many small or early lesions. Reported PR sensitivity for AP ranges from to (approximately in clinical cohorts) and is well below cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) (approximately – ), motivating methods that improve reliability without adding radiation or cost (Yapp, Brennan & Ekpo, 2021; Karamifar, Tondari & Saghiri, 2020; Estrela et al., 2008).

Deep learning (DL) refers to multi-layer neural networks that learn hierarchical representations directly from data via end-to-end optimization. In radiographic imaging, DL models most commonly convolutional networks and, increasingly, vision transformers ingest pixel data and produce task-specific outputs; for detection, they learn to localize findings as bounding boxes with class scores from annotated examples. In dental radiology, DL has shown promise for automated analysis of radiographs, including periapical lesion detection and related tasks (Çelik et al., 2023; Ekert et al., 2019; Cantu et al., 2020; Khan et al., 2021). However, gains achieved on development datasets may not carry over to deployment due to domain shift, i.e., systematic differences between training and inference data. In medical imaging, shift can arise from hardware and protocol heterogeneity, patient population differences, and—critically for periapical detection—variation in the target morphology (lesion size, margin sharpness, and contrast) (Pooch, Ballester & Barros, 2020; Szumel et al., 2024; Sahiner et al., 2023; Abbasi-Sureshjani et al., 2020). When the training distribution underrepresents certain morphologies, detectors tend to miss small/ill-defined lesions or overcall dense ones.

Prior work in medical and dental imaging has explored generative adversarial networks (GANs) and diffusion models to synthesize anatomy or pathology (Yang et al., 2023; Schoenhof et al., 2024; Jain et al., 2025), but such methods require sizeable task-specific datasets and careful tuning to train stably. Recently, foundation models, including multimodal vision–language models (VLMs), have demonstrated broad generalization across tasks owing to large-scale pre-training. Yet, running them directly in clinical workflows can be costly, and closed-source deployments raise privacy concerns. An attractive compromise is to use foundation models upstream of training—to guide controllable synthetic data generation that strengthens smaller, deployable detectors—thereby retaining transparency and auditability without requiring domain-specific generative model training.

This study adopts panoramic radiographs as a focused testbed for morphology/size shift and compares two controllable synthesis strategies: (i) an Expert-Guided Synthesis (EGS) pipeline in which clinicians delineate lesion masks that are rendered procedurally (noise-based texture, intensity modulation, edge blending); and (ii) a Prompt-Guided Lesion Synthesis (PGLS) pipeline in which clinicians specify lesion attributes via text prompts (size, shape, margin sharpness, contrast, location), and a foundation model translates these prompts into parameter schedules that drive the same renderer. Both approaches are fully auditable and permit explicit control of lesion characteristics; PGLS replaces manual mask creation with generic prompting, facilitating adaptation to additional forms of domain shift beyond morphology.

The present work investigates whether such controllable synthetic augmentation can mitigate morphology/size domain shift in periapical lesion detection. Specifically, the objectives are to (1) quantify robustness gains from Real+EGS and Real+PGLS training relative to a Real-only baseline under patient-wise cross-validation with size-stratified evaluation; and (2) assess whether PGLS provides broader and larger improvements than EGS while preserving transparency suitable for clinical translation. Detailed algorithmic parameters, dataset characteristics (including acquisition specifics and lesion size distribution), and training configurations are reported in the Methods to ensure reproducibility.

Materials and Methods

Image data set

A total of 196 digital panoramic radiographs were involved in the study, from the archive of Kafkas University, School of Dental Faculty. The dataset, consisting of adult panoramic X-rays, was obtained from the institutional archive without revealing gender or age information. All data were anonymized and stored to protect patient confidentiality. In order to diversify the dataset and improve model generalizability, each X-ray was selected from this dental library. The Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Kafkas University, approved the study (approval no. 80576354-050-99/224) and waived the requirement for informed consent, as only anonymized retrospective data were used. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Exclusion criteria included: retained deciduous teeth and deciduous dentition; images with motion artifacts or incomplete jaw coverage; artifacts from earrings, glasses, or removable dentures; and edentulous jaws. All radiographs were produced using a digital panoramic machine (KaVo OP 2D, KaVo Dental Systems Japan G.K., Tokyo, Japan) with standard parameters, operating at tube voltages between 60 and 90 kV and tube currents between 1 and 10 mA. For analysis, all images were exported in PNG format with a resolution of pixels.

While this dataset (196 radiographs, 145 with lesions) from a single center is modest, it reflects typical real-world constraints in medical imaging where data acquisition and expert annotation are resource-intensive. Our study specifically addresses this challenge by demonstrating how synthetic augmentation can develop robust detection models despite data scarcity. Although we employed five-fold cross-validation and size-stratified evaluation to ensure methodological rigor, validation with different imaging devices, acquisition protocols, and patient populations would be necessary to establish broader generalizability.

Splitting the data set

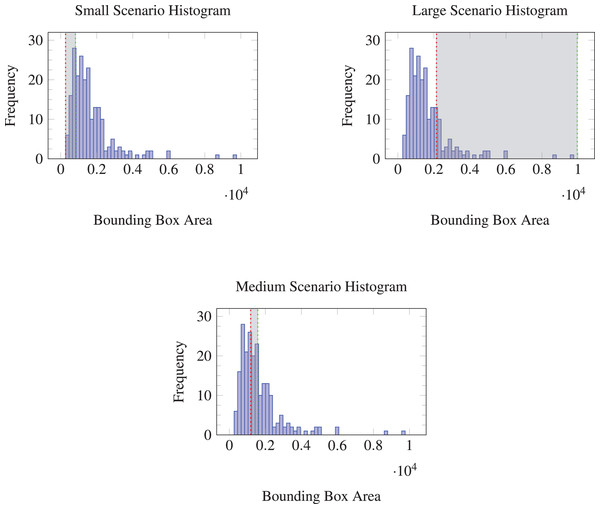

In this study, three validation scenarios were designed based on the bounding box sizes of periapical lesions in the dataset to evaluate model robustness to data drift. The bounding boxes were sorted by area and divided into three groups. The smallest 20 percent of the bounding boxes by area were assigned to the validation set in the first scenario, aimed at assessing the model’s ability to generalize to smaller lesions, which are often more challenging to detect.

In the second scenario, the validation set comprised the next 20 percent of bounding boxes, representing the middle range of the size distribution. This scenario reflects an average case and serves as a baseline for model performance.

The final scenario used the largest 20 percent of bounding boxes in the validation set, designed to test the model’s robustness to larger lesions. Although such lesions are generally easier to detect, they may be relatively underrepresented in practice, since it is reasonable to assume that patients often seek professional care before disease progression becomes severe.

By splitting the dataset in this manner, the performance of the models across different lesion sizes was evaluated, simulating the conditions of data drift. Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of bounding box areas for each of these validation splits.

Figure 1: Histograms of bounding box areas with different validation splits (Small, Medium, Large).

Synthetic data generation

Two complementary pipelines were used to synthesize periapical lesions on healthy radiographs: (i) EGS, in which clinicians delineate a free-form lesion mask and a procedural renderer applies texture (Perlin noise), intensity modulation, and edge blending; and (ii) PGLS, in which clinician-provided attributes are translated into renderer parameters. This subsection details EGS; PGLS is described separately.

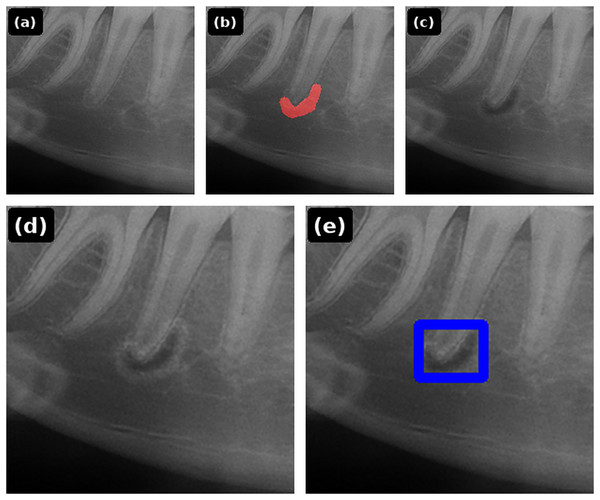

Expert-guided synthesis

Synthetic lesion data were generated from 51 healthy panoramic radiographs. A clinician interactively marked a lesion mask on each image; the renderer then applied (1) noise-based microtexture, (2) size-scaled darkening of the lesion interior, and (3) Gaussian edge blending to emulate the transition to surrounding tissues. Rendering parameters were systematically adjusted within predefined ranges until a natural appearance was achieved: Perlin octaves , spatial scale px, interior darkening factor , Gaussian blur kernel up to with , optional bright rim width px with factor , and a small-lesion rim trigger at area fraction . A second endodontist reviewed each synthetic image for face validity; unrealistic results were iteratively revised until consensus (inter-rater statistics were not computed). The step-by-step EGS pipeline is illustrated in Fig. 2, and the corresponding renderer is summarized in Algorithm 1.

Figure 2: EGS pipeline: (A) healthy periapical radiograph; (B) free-form lesion mask; (C) Perlin texture and size-scaled darkening; (D) Gaussian edge blending (optional bright rim for tiny lesions); (E) final image with detection box overlay.

| Input: Healthy radiograph ; binary mask M drawn by clinician | ||

| Output: Augmented image | ||

| /* 1) Create texture (Perlin noise) */ | ||

| 1 PerlinNoise ; | ||

| /* 2) Darken lesion interior */ | ||

| 2 ; // fractional darkness (0 = none, 1 = black) | ||

| 3 ; | ||

| 4 ; | ||

| /* 3) Blur mask edges for realism */ | ||

| 5 GaussianBlur ; | ||

| 6 ; | ||

| /* 4) (Optional) bright rim for tiny lesions */ | ||

| 7 ; // 0.1% of image area | ||

| 8 if then | ||

| 9 | DilateEdges ; | |

| 10 | ; // rim brightening factor | |

| 11 | ; | |

| 12 return ; | ||

Prompt-guided lesion synthesis

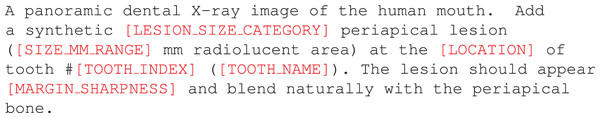

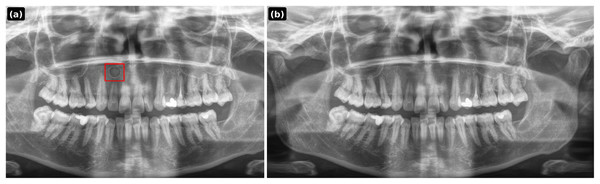

PGLS employs an instruction-tuned vision–language foundation model, specifically ChatGPT-4o in image-generation and editing mode, to produce controllable and auditable synthetic variants from healthy panoramic radiographs. The method operates in an image-to-image paradigm: a healthy radiograph is supplied together with a natural-language prompt that specifies the desired modification, such as the size, location, and margin sharpness of a lesion or the transfer of an acquisition artifact. For artifact transfer, an auxiliary source image can also be provided. Importantly, no task-specific fine-tuning is required, which offers advantages in terms of privacy, reproducibility, and rapid adaptability.

All target images are drawn exclusively from open-source healthy panoramics (Hamamci et al., 2023); no patient images from the study cohort were ever processed by the foundation model. Prior to editing, the images are normalized to 8-bit grayscale and resized to a resolution of . Prompts are structured to encode clinically meaningful attributes—for example, tooth index, approximate lesion diameter, or artifact geometry—while remaining human-readable Fig. 3. The model then generates an edited output conditioned on the provided radiograph (and, if applicable, the auxiliary source image). Edits are accepted only if the global anatomy is preserved and the change is confined to the designated region.

Figure 3: Prompt template used to generate the 50 synthetic examples with Prompt-Guided Lesion Synthesis (PGLS).

Variable parts are highlighted in red.All outputs are saved as PNG at and undergo expert visual screening by an endodontist to ensure face validity. For reproducibility, every prompt, random seed, model identifier, and file hash is logged. Representative examples of PGLS outputs are shown in Figs. 4–6.

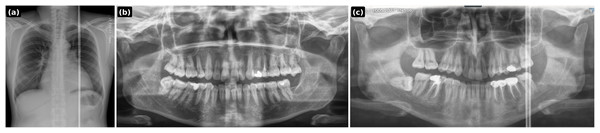

Figure 4: PGLS lesion synthesis conditioned on a healthy panoramic radiograph.

(A) Synthesized lesion with detection box; (B) original healthy PR.Figure 5: PGLS artifact transfer (vertical bright line) from an external source image to a dental panoramic radiograph.

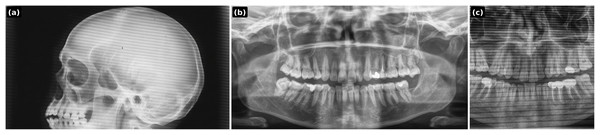

(A) Source artifact (chest X-ray); (B) target healthy panoramic radiograph; (C) output after PGLS transfer.Figure 6: PGLS artifact transfer (horizontal banding) to simulate acquisition-induced domain shift.

(A) Source artifact (skull X-ray); (B) target healthy panoramic radiograph; (C) output after PGLS transfer.Prompt 1: A panoramic dental X-ray image of the human mouth. Add a synthetic medium periapical lesion (4–6 mm radiolucent area) at the apex of tooth #11 (maxillary right central incisor). The lesion should appear well-defined and blend naturally with the periapical bone.

Prompt 2: Transfer the vertical bright radiographic artifact line from the chest X-ray input onto the dental panoramic X-ray input. Place the artifact on the right side of the dental X-ray image, extending continuously from the top to the bottom. Ensure the artifact blends naturally with the radiograph as if it originated during the scan. Ensure it is not a single wide straight white line but a combination of white lines, some running full-length and some stopping midway. Output only the modified dental panoramic X-ray image. Chest xray

Prompt 3: Transfer the horizontal aliasing artifact pattern seen in the skull X-ray onto the dental panoramic X-ray. The artifact should appear as repeating horizontal banding lines across the entire dental image, with the same frequency, thickness, and intensity as in the skull X-ray. Ensure the lines blend naturally with the dental radiograph, as if they originated during the scan, while keeping the jaw anatomy clearly visible. Output only the modified dental panoramic X-ray. Skull xray

Generative networks

Generative adversarial networks (GANs) learn a generator–discriminator game in which the generator maps latent noise to images while the discriminator distinguishes real from synthetic, driving the generator toward the data distribution (Goodfellow et al., 2014). Among modern variants, StyleGAN introduces a style-based architecture that modulates each convolutional layer with per-layer “styles” derived from a mapping network, plus stochastic noise to control fine detail (Karras, Laine & Aila, 2019). StyleGAN2 refines this design with weight demodulation and path-length regularization to suppress characteristic artifacts and improve fidelity (Karras et al., 2020b); adaptive discriminator augmentation (ADA) further stabilizes training on small datasets by adjusting augmentation strength in response to discriminator overfitting (Karras et al., 2020a).

In medical imaging, these models face two practical constraints. First, they typically require large, homogeneous datasets and careful hyperparameter tuning (e.g., resolution, effective batch size, network capacity/regularization, training duration, and augmentation schedule) to avoid mode collapse and overfitting. Second, controllability—for example, specifying lesion location, diameter, and margin sharpness or introducing particular acquisition artifacts—usually demands conditional architectures (e.g., class/segmentation–conditioned GANs) or post-hoc inversion/editing pipelines, each adding annotation burden and computational complexity.

A StyleGAN2 baseline was trained on the available healthy panoramic radiographs using a standard small-data configuration: sub-megapixel training resolution (on the order of ), a small physical batch with gradient accumulation to reach a modest effective batch size, moderate network capacity, 20,000 of optimization steps, and probabilistic differentiable augmentations roughly in the ADA range. Despite these measures, the model did not yield radiographically credible panoramics Fig. 7. Also achieving any control would have required additional labels and specialized conditioning, which was incompatible with the dataset size and study scope.

Figure 7: Representative sample from the StyleGAN2 baseline trained on healthy panoramic radiographs (low-resolution run).

Note the lack of radiographic fidelity and anatomical distortions, illustrating the difficulty of realistic, controllable synthesis under data scarcity. In contrast, the PGLS approach preserves anatomical integrity and achieves stable, controllable lesion synthesis without requiring task-specific training or large datasets.These limitations motivate the pivot to prompt-guided synthesis with a vision–language foundation model. Instead of training a new generator, the model is used in image-to-image generation mode to apply explicit, auditable instructions to healthy exemplars (e.g., lesion size/location/margins; transfer of vertical or banding artifacts). This approach operates without task-specific fine-tuning, scales to full-resolution images, preserves global anatomy, and readily supports diverse domain-shift scenarios. In short, while GANs provide powerful unconditional generative capability under abundant data and careful training, prompt-guided editing offers the required flexibility and controllability for targeted augmentation in data-limited clinical settings.

Experiment design

This study evaluates whether synthetic augmentation improves robustness to morphology- and size-related domain shifts in periapical lesion detection. YOLOv10 with 1,280 input resolution was used for all experiments. Default hyperparameters were adopted from the official YOLOv10 configuration: stochastic gradient descent with momentum ( ), initial learning rate ( with cosine decay), weight decay ( ), batch-normalized CSP-based backbone, multi-scale augmentation, label smoothing ( ), warmup iterations (three epochs), and training for epochs with early stopping. These parameters were held constant across all training regimes.

Three training regimes were compared:

-

1.

Real-only: Models trained exclusively on clinical images with expert annotations.

-

2.

Real+EGS: Real-only data augmented with EGS, generated from 51 healthy panoramic radiographs using clinician-drawn masks rendered with the procedural pipeline (Fig. 2, Algorithm 1).

-

3.

Real+PGLS: Real-only data augmented with 50 PGLS examples, produced by a vision–language foundation model, ChatGPT-4o (image generation mode). The model operated in image-to-image mode on open-source healthy panoramics (Figs. 4–6).Outputs were saved as PNG ( ) and visually screened by an endodontist for anatomical fidelity.

Each patient contributed a single radiograph, so patient-level leakage is structurally precluded. First, for each scenario we defined a fixed validation set by ranking all lesions by bounding-box area and selecting the target stratum (smallest 20%, middle 20%, or largest 20%). The remaining cases formed the training pool. Then, we performed five-fold cross-validation only within the training pool: in each run, four folds were used for training and the remaining fold was discarded (i.e., not reassigned to validation). We did not add the unused training fold to the validation set, because that would dilute the deliberately size-skewed validation distribution and undermine the intended morphology-shift evaluation. This preserves a constant, size-controlled validation set while still averaging over training variability across folds.

Primary endpoints were [email protected], mAP@[0.5:0.95], and Recall. Metrics were calculated using the five folds, and percentage change relative to Real-only (% ) was reported to convey effect size.

All experiments were conducted on a single NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPU with 24 GB memory. Inference time was approximately 35 ms per image at 1,280 1,280 resolution, enabling real-time clinical deployment on standard workstation hardware.

Results

Table 1 summarizes size–stratified performance for the three training regimes using YOLOv10. Across all endpoints, augmentation with synthetic data improved performance relative to Real-only, with PGLS generally exceeding EGS. For [email protected] (overall), Real+EGS and Real+PGLS improved upon Real-only by +6.4% and +8.5% (0.47 0.50/0.51). For mAP@[0.5:0.95] (overall), gains were larger (+13.6% and +18.2%; 0.22 0.25/0.26), consistent with tighter localization at higher IoU thresholds. Overall recall increased by +10.6% (EGS) and +12.8% (PGLS; 0.47 0.52/0.53). As expected, improvements were most pronounced in the small and large strata, where the size–stratified validation induces a greater distributional shift between training and evaluation (extreme tails of the lesion-size distribution); the medium stratum exhibited smaller but consistent gains.

| Metric | Stratum | Method | Value | Range (min–max) | SD | % vs. Real-only |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [email protected] | ||||||

| Overall | Real-only | 0.47 | [0.45–0.49] | 0.015 | — | |

| Overall | +EGS | 0.50 | [0.48–0.52] | 0.017 | +6.4% | |

| Overall | +PGLS | 0.51 | [0.49–0.53] | 0.016 | +8.5% | |

| Small | Real-only | 0.30 | [0.21–0.35] | 0.054 | — | |

| Small | +EGS | 0.36 | [0.28–0.42] | 0.056 | +20.0% | |

| Small | +PGLS | 0.39 | [0.31–0.46] | 0.061 | +30.0% | |

| Medium | Real-only | 0.58 | [0.56–0.61] | 0.019 | — | |

| Medium | +EGS | 0.60 | [0.58–0.63] | 0.021 | +3.4% | |

| Medium | +PGLS | 0.62 | [0.60–0.65] | 0.020 | +6.9% | |

| Large | Real-only | 0.46 | [0.41–0.51] | 0.039 | — | |

| Large | +EGS | 0.51 | [0.47–0.55] | 0.031 | +10.9% | |

| Large | +PGLS | 0.52 | [0.48–0.56] | 0.032 | +13.0% | |

| mAP@[0.5:0.95] | ||||||

| Overall | Real-only | 0.22 | [0.20–0.24] | 0.016 | — | |

| Overall | +EGS | 0.25 | [0.23–0.27] | 0.015 | +13.6% | |

| Overall | +PGLS | 0.26 | [0.24–0.28] | 0.017 | +18.2% | |

| Small | Real-only | 0.085 | [0.050–0.115] | 0.026 | — | |

| Small | +EGS | 0.120 | [0.090–0.150] | 0.024 | +41.2% | |

| Small | +PGLS | 0.130 | [0.100–0.160] | 0.025 | +52.9% | |

| Medium | Real-only | 0.26 | [0.24–0.29] | 0.019 | — | |

| Medium | +EGS | 0.28 | [0.26–0.31] | 0.021 | +7.7% | |

| Medium | +PGLS | 0.29 | [0.27–0.32] | 0.020 | +11.5% | |

| Large | Real-only | 0.20 | [0.17–0.22] | 0.019 | — | |

| Large | +EGS | 0.235 | [0.205–0.260] | 0.022 | +17.5% | |

| Large | +PGLS | 0.240 | [0.210–0.270] | 0.024 | +20.0% | |

| Recall (Sensitivity) | ||||||

| Overall | Real-only | 0.47 | [0.44–0.49] | 0.019 | — | |

| Overall | +EGS | 0.52 | [0.49–0.55] | 0.023 | +10.6% | |

| Overall | +PGLS | 0.53 | [0.50–0.56] | 0.024 | +12.8% | |

| Small | Real-only | 0.27 | [0.20–0.32] | 0.047 | — | |

| Small | +EGS | 0.33 | [0.27–0.38] | 0.043 | +22.2% | |

| Small | +PGLS | 0.35 | [0.29–0.41] | 0.046 | +29.6% | |

| Medium | Real-only | 0.50 | [0.47–0.53] | 0.023 | — | |

| Medium | +EGS | 0.53 | [0.50–0.56] | 0.024 | +6.0% | |

| Medium | +PGLS | 0.55 | [0.52–0.58] | 0.025 | +10.0% | |

| Large | Real-only | 0.49 | [0.45–0.53] | 0.031 | — | |

| Large | +EGS | 0.56 | [0.52–0.60] | 0.032 | +14.3% | |

| Large | +PGLS | 0.57 | [0.53–0.61] | 0.033 | +16.3% | |

Inspection of errors indicated that many failures occurred on cases with features outside the training distribution, such as nonstandard exposure, missing teeth, and implants Fig. 8. These out-of-distribution factors are good candidates for targeted augmentation in subsequent work; prompt-guided edits can be used to synthesize such conditions deliberately and reduce residual failure modes.

Figure 8: Representative failure cases shown side by side.

Discussion

Foundation-model–driven editing provided practical advantages over training bespoke generators. The vision–language model (ChatGPT-4o, image-generation mode) accepted natural-language specifications for lesion attributes (location, diameter, margin sharpness) and acquisition factors (banding, vertical streaks, exposure changes), producing edits that preserved global anatomy while introducing the intended, auditable change. The approach scales by expanding a prompt library rather than by collecting large, homogeneous datasets or tuning fragile generative training schedules, and it can operate at native radiograph resolution with modest compute.

The same prompting strategy generalizes beyond morphology/size shift to other clinically relevant domain shifts, including device differences and acquisition artifacts. A simple detector-in-the-loop workflow can mine failure cases, extract salient attributes (e.g., low-contrast small lesions adjacent to metallic restorations), instantiate targeted prompts, and iteratively enrich the next training round without accessing additional patient data.

For clinical deployment, an operating point should be selected that prioritizes sensitivity for early disease while maintaining an acceptable false-positive burden. Score thresholds can be tuned on a held-out set and periodically re-calibrated as acquisition protocols evolve. Bounding-box outputs are directly reviewable and can be exported as Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) overlays for Picture Archiving and Communication Systems (PACS), enabling second-reader or triage use without disrupting standard workflows. The synthetic pipelines are auditable by design (prompt/mask logs and file hashes), supporting version control, clinical governance, and traceability. Because PGLS edits are generated on open-source exemplars rather than patient data, privacy risk is minimized; if site-specific curation is desired, on-premises or privacy-preserving VLM endpoints would be preferred.

Post-deployment monitoring should track indicators of drift (e.g., score distributions, metadata shifts) and sample errors for periodic review. Newly observed shift factors (e.g., unfamiliar artifacts or exposure regimes) can then be translated into targeted prompts, generating additional training exemplars before the next model refresh—closing the loop with a detector-in-the-loop augmentation cycle.

This study has limitations. The dataset is modest and single-center. Each patient contributed a single radiograph, which prevents patient-level leakage but also limits the diversity of repeated acquisitions. Demographic and clinical covariates (e.g., age, sex) were not collected, so no subgroup analyses were performed and potential demographic effects could not be assessed.

Conclusions

In summary, synthetic augmentation increased robustness to morphology/size shift, with consistent gains across endpoints and the largest benefits for small lesions. PGLS outperformed EGS in most strata, reflecting the advantage of controllable, text-driven edits without the data and stability burdens typical of GAN/diffusion training. Prompt-guided synthesis therefore offers a scalable, auditable path to produce clinically targeted augmentations that improve detector reliability under domain shift in data-limited medical settings.

Future work includes prospective, multi-site external validation with reader studies against clinician baselines; calibration assessment at clinically meaningful operating points; and evaluation across devices and protocols. Methodologically, ablations over prompt attributes (size, margin sharpness, contrast, tooth index), synthetic sampling ratios, and seed diversity are planned, along with expansion of the prompt library to cover remaining out-of-distribution factors seen in failures (e.g., metallic restorations, edentulous segments, additional artifact classes). Comparisons with alternative foundation models and on-prem VLM deployments are envisioned, and open-source VLM alternatives are a priority for systematic investigation and benchmarking to provide an open-source option for deployment. Limited demographic and clinical covariates are to be collected to enable subgroup analyses and fairness checks, and standardized DICOM I/O plus model cards are targeted to support safe integration into decision-support systems.

Supplemental Information

Code related to the study.

Scripts to fully replicate the study, including preprocessing, the image-augmentation pipeline (implementation and configs), and training/inference routines.