Digital twin-enabled AI for sustainable traffic management: real-time urban mobility optimization in smart cities

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Paulo Jorge Coelho

- Subject Areas

- Computer Networks and Communications, Distributed and Parallel Computing, Optimization Theory and Computation, Real-Time and Embedded Systems, Internet of Things

- Keywords

- Digital twin, Real-time traffic management, Gated recurrent unit, Intelligent transportation systems (ITS), Traffic forecasting, Artificial intelligence (AI), Internet of things (IoT)

- Copyright

- © 2026 Abdallah and Alghamdi

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2026. Digital twin-enabled AI for sustainable traffic management: real-time urban mobility optimization in smart cities. PeerJ Computer Science 12:e3574 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3574

Abstract

An intelligent and agile traffic signal system has emerged as a vital sustainable component of urban mobility. The centralised traffic control systems currently in use are not capable of providing the required responsiveness or scalability to facilitate real-time traffic management. In this article, we propose a lightweight hybrid system that integrates a Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) based predictive model and Digital Twin (DT) technology to provide decentralised, real-time traffic signal optimisation. The GRU model forecasts future localised congestion events from vehicle based Internet of Things (IoT) sensors, while the DT model ensures adequate performance by validating and adjusting control actions based on live information concerning roadway condition changes. We present results that demonstrate improvement of predictive accuracy by 33% (mean absolute error = 4.5), control latency of 78 ms, and a 15% decrease in CO2 emissions, along with substantial decreases in both congestion and travel time. It was found that the proposed model consistently outperformed the state of the art solutions with improved prediction, latency, and environmental efficiency. The proposed architecture provides superior real-time traffic management within smart city environment.

Introduction

Rapid urbanization and its increasing demand on transportation infrastructure is one of the major driving forces behind sustainable urban mobility in today’s smart cities. By the year 2050, as stated by the United Nations, more than 68 per cent of the global population will live in urban areas. This will increase congestion, energy consumption and CO2 emissions (Nations, 2019). Traditional traffic management systems are still primarily centralised and reactive, using historical traffic data and fixed control strategies, which are not scalable or adaptable to rapidly changing road conditions (Kim et al., 2025; Abdullah et al., 2023). They also lead to extended wait times, high fuel consumption, and overall reduced quality of life in urban areas.

Intelligent transportation systems (ITSs) that use combinations of the Internet of Things (IoT), artificial intelligence (AI) and provide real-time decision making (Sayed, Abdel-Hamid & Hefny, 2023) are developing to address these limitations. However, recent ITS deployments have not been able to deliver anticipatory traffic responses due to a lack of predictive capabilities and reliance on cloud-based infrastructure that introduces latency and prohibits real-time adaptation. Digital Twin (DT) technology has become popular to create a virtual representation of physical traffic environments, allowing real-time sensor data to be used in conjunction with simulation models to evaluate control decisions before implementation (Huzzat et al., 2025; Irfan, Dasgupta & Rahman, 2022). However, most of the current DT proposals focus on descriptive monitoring vs. predictive, closed-loop control. Most books describing Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) are Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)–LSTM-based predictors, and reinforcement learning–based digital twin (DT) architectures generally have the following drawbacks:

High computational overhead of deploying on the edge,

Inference latency due to centralised training,

Open-loop modelling that separates prediction from control, and

A lack of consideration of environmental performance metrics like CO2 elimination (Anniciello et al., 2023; Kušić, Schumann & Ivanjko, 2023).

As a result, there is an opportunity for systems that forecast, simulate, and optimise urban traffic simultaneously and near real time. Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs) have emerged as a viable alternative to LSTMs due to their lower computational complexity and upper performance rates through fewer parameters and temporal dependencies captured (Manglano-Redondo, Paricio-Garcia & Lopez-Carmona, 2025; Di et al., 2024). The efficiency of GRUs provides them with an excellent opportunity for deployment on edge nodes close to traffic sensors. However, to date, no research has integrated foresight with DT validation for real-time proactive traffic control while adhering to both strict latency limitations and sustainability constraints.

The goal of this research is to provide a comprehensive GRU-DT traffic control approach to anticipate congestion, approve of predicted conditions in the DT environment, and deploy optimal routing and signalling plans in real-time on the edge. This methodology provides a means to shift existing “predictive only” methodologies to a “predict before controlling” paradigm for traffic, allowing for rapid decision-making on the part of traffic controllers and verified environmental benefits.

Specifically, this research contributes:

The creation of an innovative GRU-DT cooperative framework to unify temporal forecasting and DT-based evaluations for real-time traffic control in the context of a smart city;

The design of a lightweight GRU modeling methodology optimised for edge deployments, which alleviates many of the latency and scalability problems associated with the application of recent ITS methodologies;

A closed-loop integration of Digital Twins, providing proactive processing of control actions and thereby reducing travel time, severity of congestion, and CO2 emissions;

An exhaustive evaluation of this methodology using SUMO, confirming superior performance in terms of precision, latency, and ecological footprint over the latest comparative baseline data.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows: “State-of-the-Art and Related Work” presents a critical review of related work focusing on Digital Twin systems for traffic management, temporal AI models for urban forecasting, and sustainable mobility approaches. “Methodology” describes the proposed design, the data pipeline, and the implementation of the GRU model within the Digital Twin framework. “Experimental Results and Analysis” outlines the experimentation conducted in Simulation of Urban Mobility (SUMO), including the data sources, simulation scenarios, and evaluation metrics. “Comparison with Existing Works” presents the results, along with a comparison to state-of-the-art ITS approaches. Finally, “Conclusion and Future Work” concludes the article with a summary and directions for future research and implementation.

State-of-the-art and related work

Environmental changes and growth of urbanization have caused impact on urban mobility awareness for gaining livability and sustainability. Urban mobility interacting with technology and innovation has created smart urban systems and the applications of Digital Twin and AI offer possible solutions to overcome some urban mobility challenges.

Technology has enabled Digital Twin (DT) technology, artificial intelligence (AI), and Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) based short term traffic forecasting job functions and focus related to advanced urban mobility aspects. This literature review contains valuable contributions to the integration of digital twin technology to smart city networking design, the application of GRU short term forecasting with historical temporal neural network modelling, and the flow related to achieving sustainable and intelligent urban mobility aspects that include intelligent transport system (ITS). Digital Twins of urban traffic systems enable real time imaging of constructing and modifying knowledge on urban traffic systems, along with allowing for decision and knowledge centre for the purposeful handling of urban planners within various disruptions (Huzzat et al., 2025; Rezaei et al., 2025). Changing urban traffic behaviors can lead to congestion. Kušić, Schumann & Ivanjko (2023) provided insights into a new method for traffic operators, by outlining new methods for incorporating real-time traffic data flow into digital simulation environments for congestion analysis and what-if experiments. Faliagka et al. (2024) presented a modular type DT to think about solutions for urban mobility—specifically by thinking about incidents and adaptive routing near a traffic disruption. Di et al. (2024) highlighted the integration of AI based prediction models into DTs to help optimize urban traffic condition in the future. Batty et al. (2012) examined the original concept of digital twins in smart cities and sustainable developments trends for future planning and urban utilities infrastructures. Bibliometric analysis El-Agamy et al. (2024) and Kajba, Jereb & Cvahte Ojsteršek (2023) information on DT in transportation and energy systems to identify future growing literature areas and cultural significance (El-Agamy et al., 2024; Kajba, Jereb & Cvahte Ojsteršek, 2023). At the same time, Irfan, Dasgupta & Rahman (2022) presented an overview of DT deployments, with a specific emphasis on DTs addressing safety, mobility, and improvements of other best traffic practices. The applied side for DTs was represented by Abouelrous, Bliek & Zhang (2023), who illustrated how Digital Twins could be used to support logistics orchestration in an urban area. Meanwhile, there were insights by Werbińska-Wojciechowska, Giel & Winiarska (2024) that illustrated how DTs could contribute to operation and maintenance tasks in transport networks. The focus of Feng, Lv & Lv (2023) was on how DTs could coexist with chaotic, and fast-changing traffic considerations, proposing their own specific DT formulations that focused on disruption resilience. Prikler & Wotawa (2023) contributed their perspectives using DTs in similarity diagnostic and fault-detection-based settings, setting more opportunity and structural limitations to that conversation about DT mediated integration into transportation infrastructure, and Wu et al. (2025) documenting points for both opportunity and structural limitations. On the matter of diagnosing and fault detection, all this review (El-Agamy et al., 2024) took into consideration and notes that although there are new perspectives, there consistently are two factors that remain unexamined whether in literature or practice: sustainability-based control is not yet, or only to some degree, available, and real-time AI-based coupling is still largely under-researched.

On the predictive side, GRU architectures have progressively emerged as a pragmatic choice for traffic flow forecasting due to their favourable balance between accuracy, stability and computational cost. Abdullah et al. (2023) applied a Soft-GRU variant for short-horizon congestion inference and reported reliable performance. Comparative studies by Hossain, Ahmed & Ullah (2022) and Ma et al. (2015) also observed that GRUs tend to converge faster than LSTMs, which makes them more appropriate for real-time pipelines. Beyond classical Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), Zhang, Zheng & Qi (2017) proposed a spatio-temporal residual network to capture meso-level interaction patterns across the city. More recent hybrid approaches such as the GRU-Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) structure reported by Abouelrous, Bliek & Zhang (2023) showed gains in eco-routing and flow harmonisation. Similar graph-centric forecasting strategies were examined by Yu, Yin & Zhu (2017) and Yao et al. (2018), while large-scale validation was reported in Geng et al. (2019) and Lv et al. (2014). Distributed learning has also begun to receive attention: Banik, de Carvalho & Dividino (2025) introduced privacy-preserving federated aggregation for traffic prediction, and Orozco et al. (2024) complemented this with synthetic augmentation to improve generalisation. Studies by Dasgupta, Rahman & Jon (2024) and Zhu et al. (2024) further demonstrate that combining GRU forecasting with DT-mediated signal control is feasible although these works remain limited to partial coupling or narrow operational scopes.

Finally, the sustainability dimension is becoming increasingly central as cities aim to limit the ecological footprint of mobility systems (Nations, 2019; Kim et al., 2025). Kim et al. (2025) demonstrated that multi-agent reinforcement learning can reduce emissions by coordinating signal plans, whereas Sayed, Abdel-Hamid & Hefny (2023) highlighted that many AI-based flow models still overlook emission-sensitive objectives. Irfan, Dasgupta & Rahman (2022) showed that DT-enabled traffic actuation can reduce energy consumption, and Abouelrous, Bliek & Zhang (2023) reported similar efficiency gains in logistics. Maintenance-oriented advantages were documented by Werbińska-Wojciechowska, Giel & Winiarska (2024), and resilience aspects were again emphasized by Feng, Lv & Lv (2023). Wu et al. (2025) analysed the deployment barriers from an infrastructure perspective. Governance-oriented design recommendations proposed by Prikler & Wotawa (2023) converge with the conclusions of El-Agamy et al. (2024), who stress that real-world adoption will ultimately hinge on architectures that fuse real-time AI forecasting with DT capabilities and embed sustainability as a first-class optimisation criterion.

Despite significant progress, integration between GRU models and DT platforms remains underexplored, and comprehensive sustainability metrics (e.g., CO2 emissions, energy usage) are rarely evaluated.

Recent advancements in deep learning and edge-intelligent frameworks have further extended the realm of urban traffic prediction. Ali et al. (2025) proposed a dynamic multi-graph spatio-temporal model for traffic forecasting in city-scale scenarios, which demonstrated promising accuracy rates, however, it was a centralized architecture with no premise of Digital Twin feedback. Ali et al. (2025) created an attention controlled hybrid spatio-temporal neural network that exhibited strong latent pattern extraction, however, it was left with offline processing without adaptation for real-time control of urban traffic. Li, Sun & Wan (2025) developed the Spatio-Temporal Multi-Graph Convolution Traffic Flow Prediction Model Based on Multi-Source Information Fusion and Attention Enhancement (MIFA-ST-MGCN) model that saw the use of multi-source data and attention mechanism; nevertheless, it does not consider latency optimization or an evaluation of sustainability.

Simultaneously, several energy-aware control strategies have been explored in neighbouring domains. Ali et al. (2025) applied graph convolutional networks for task allocation in edge computing demonstrating the capability for high parallel optimization, but which did not interface with an integrated urban mobility system. Rezakhani et al. (2024) and Elsedimy, Herajy & Abohashish (2025) investigated the problems of energy- and Quality of Service (QoS)-aware virtual machine placement that improved computational benefits, but did not represent specific traffic dynamics.

On the other hand, our innovative framework named GRU-DT combines low-complexity sequence modeling together with Digital Twin-based real-time simulation. It differs significantly in that it combines proactive GRU-based traffic congestion forecasting with closed-loop Digital Twin validation to achieve real-time low-latency operational control (<80 ms) and explicit sustainability optimization (CO2 reduction ≈15%). This contextualization, seeks to demonstrate the originality and practical importance of the proposed GRU-DT framework as a potential bridge between forecasting modeling and deployable knowledge for intelligent traffic management in smart cities.

The previous discussions provide a structured overview of how the existing literature has developed Digital Twin-enabled traffic systems, GRU-based temporal forecasting, and sustainable ITS framework.

To simplify direct comparison, Table 1 summarises the main research axes identified in the literature Digital Twin systems, deep spatio-temporal traffic prediction, energy- and QoS-aware resource management, and sustainable ITS control and positions the proposed GRU–DT framework with respect to their strengths and remaining gaps.

| Research axis/approach | References | Main focus and techniques | Key limitations w.r.t. real-time, DT–AI coupling, and sustainability | Positioning w.r.t. proposed GRU–DT framework |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital Twin (DT) systems for transportation and smart cities | Huzzat et al. (2025), Anniciello et al. (2023), Kušić, Schumann & Ivanjko (2023), Di et al. (2024), Rezaei et al. (2025), Kušić, Schumann & Ivanjko (2023), Faliagka et al. (2024), Di et al. (2024), Batty et al. (2012), El-Agamy et al. (2024), Kajba, Jereb & Cvahte Ojsteršek (2023), Irfan, Dasgupta & Rahman (2022), Abouelrous, Bliek & Zhang (2023), Werbińska-Wojciechowska, Giel & Winiarska (2024), Feng, Lv & Lv (2023), Prikler & Wotawa (2023), Wu et al. (2025), El-Agamy et al. (2024) | DT architectures for smart cities; virtualisation of motorway dynamics; DT for congestion analysis, incident management, logistics, operation & maintenance, resilience and diagnostics in transport infrastructure. | Most works emphasise monitoring, what-if analysis or offline optimisation rather than closed-loop predictive control; AI components are often loosely coupled; real-time edge execution and explicit sustainability metrics (CO2, energy) are rarely central design constraints. | GRU–DT implements a tightly coupled DT–AI loop in which GRU predictions are continuously injected into a DT built on SUMO for online validation and control synthesis, with a specific emphasis on sub-100 ms latency and CO2 reduction (~15%). |

| Deep spatio-temporal traffic prediction (GRU/LSTM/GNN/attention) | Abdullah et al. (2023), Hossain, Ahmed & Ullah (2022), Zhang, Zheng & Qi (2017), Ma et al. (2015), Geng et al. (2019), Yu, Yin & Zhu (2017), Lv et al. (2014), Yao et al. (2018), Ali et al. (2025), Ali et al. (2025), Li, Sun & Wan (2025), Zhang et al. (2023), Dai & Tang (2025), Ali et al. (2025), Ali et al. (2024) | Short-term traffic or flow prediction using LSTM/GRU, CNN–LSTM hybrids, residual networks, spatio-temporal graph convolution, attention-based multi-graph models and federated/decentralised learning. | These models typically focus on predictive accuracy only; they are often centralised (cloud-centric) and computationally heavy; they do not close the loop with a DT control layer, and rarely evaluate latency or sustainability as first-class outputs. | GRU–DT adopts a lightweight GRU specifically sized for edge deployment, and embeds it inside a DT feedback loop where predictions directly drive and are validated against simulated control strategies, jointly optimising accuracy, latency and environmental impact. |

| Energy- and QoS-aware resource management in cloud/edge infrastructures | Ali et al. (2025), Rezakhani et al. (2024), Elsedimy, Herajy & Abohashish (2025), Ali et al. (2017), Ullah et al. (2024), Ali et al. (2016) | VM placement, consolidation and task allocation using multi-criteria optimisation, RL and ANN; focus on energy efficiency and QoS guarantees in cloud/edge data centres. | These works address computational and energy costs of IT infrastructure, not urban traffic dynamics; they do not model congestion, routing, or signal timing, and do not integrate DT-based traffic environments or IoT traffic sensors. | GRU–DT borrows the multi-objective spirit (latency, efficiency) but applies it directly to traffic control, where the optimisation space concerns signal timing, routing and CO2 emissions within a DT of the road network, rather than virtualised compute nodes. |

| Sustainable ITS and control-oriented schemes (RL, fuzzy, classical controllers) | Nations (2019), Kim et al. (2025), Sayed, Abdel-Hamid & Hefny (2023), Irfan, Dasgupta & Rahman (2022), Tunc & Soylemez (2023), Wang & Shao (2025) | ITS-based optimisation of traffic flow; multi-agent RL for emission reduction; classical PID and fuzzy controllers for adaptive signal control; survey of AI-based traffic flow models. | Classical controllers and many RL-based schemes remain reactive, adjusting signals after congestion appears; they rarely exploit short-term sequence learning for anticipation, and only a subset explicitly quantify CO2 or fuel savings under strict real-time constraints. | GRU–DT moves from reactive to anticipatory control by forecasting congestion with GRU, validating strategies in a DT and then enforcing decisions at the edge, resulting in lower ATT, lower CO2 and lower latency than reported in purely RL-, PID- or fuzzy-based approaches. |

| Proposed GRU–DT predictive digital twin framework | — | Integrated GRU-based time-series predictor with SUMO-backed DT and edge-level multi-objective control; targets real-time congestion forecasting, proactive signal timing and sustainable routing in smart cities. | — | Provides a unified, closed-loop architecture that (i) anticipates congestion, (ii) validates control actions in a DT before actuation, (iii) executes decisions at the edge with ≈78 ms latency, and (iv) explicitly optimises CO2 reduction (~15%), positioning it as a bridge between forecasting models, DT simulation, and deployable sustainable ITS control. |

Methodology

This section first presents a systematic overview of system architecture, data processing flow, prediction modeling and decision logic before providing a description of each of the components. The algorithm is designed to facilitate real-time adaptability, scalability, and sustainability for urban traffic management.

Overview of the proposed architecture

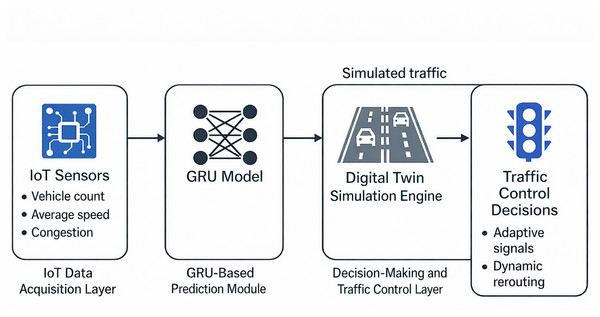

The proposed system leverages Digital Twin (DT) technology integrated with a Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU)-based predictive model to enable real-time and sustainable traffic management in smart cities. As shown in Fig. 1, the framework consists of four layers: (1) IoT data acquisition layer, (2) GRU-based prediction module, (3) Digital Twin simulation engine, and (4) decision-making and traffic control layer.

Figure 1: System architecture of the proposed DT-GRU-based traffic management framework.

In the IoT data acquisition layer, traffic data are continuously collected from multiple distributed sensors located at urban intersections. Data collected comprises vehicle count, mean speed, and real-time congestion data. Raw data is sent to the data processing unit using the IoT network, and the data are cleaned and preprocessed in the data processing unit when reporting, which involves temporal normalization and formatting for time series to be used for predictive analysis.

After the preprocessing stage, the GRU-based prediction module will receive the data to make traffic congestion predictions in the near future at time stamp t. The model uses the sliding time window methodology to predict congestion intensity during the next time interval. The GRU model will run on low-resource edge devices due to its lightweight nature which allows for near-real time inference with near-zero latency.

The Digital Twin simulation engine will simulate the predicted congestion levels and traffic states urban traffic states. The simulation module works with SUMO, a realistic model of regional traffic. The DT uses a closed feedback mechanism with the GRU model, where the GRU receives inputs and produces outputs dynamically to achieve the most accurate prediction and to adjust simulation model parameters including atmospheric conditions. With regard to administering traffic control policies, whether from the simulation outputs, such as adaptive signal timing or if some change to vehicular routes, the decision-making and traffic control layer looks at not only the nature of the outcomes related to reducing traffic congestion, but also to reduce costs related to environmental impacts measured in terms of CO2 emitted and reduction of energy usage. This framework allows scalability, and distributes opportunity to leverage data science intelligence, to represent the real-time system, as an objective in an urban mobility real system.

Data acquisition and preprocessing

To generate credible traffic forecasts, it is necessary to collect timely and accurate data from multiple traffic flows. The system we would propose collecting that data using a dense array of IoT technologies sensor systems at important intersections and major arterial city streets. The sensors will collect multimodal streams of data that include these traffic indicators:

Vehicle count (Vt): The number of vehicles passing a specific point per time unit.

Average vehicle speed (St): Measured in meters per second (m/s), reflecting real-time flow dynamics.

Congestion level (Ct): Calculated based on vehicle density and deviations from nominal speed, indicating the degree of traffic saturation.

The unprocessed sensor data is transferred in real-time using data communications protocols that are both low-latency and energy-efficient such as Message Queuing Telemetry Transport (MQTT) or Long Range Wide Area Network (LoRaWAN). This low-latency and energy-efficient data is also relayed to a local edge computing node to perform essential preprocessing functions for predictive modeling.

The anticipated basic operations in the data preprocessing should include two initial components:

Normalization: All input variables are rescaled into the normalized range [0, 1] using min–max normalization in preparation for the next steps level of analysis to enforce uniformity amongst heterogeneous types of data:

(1)

Temporal sequencing (windowing): After normalization, the data was segmented into overlapping time windows of fixed length TTT, to form structured time-series inputs to the GRU model.

(2)

By leveraging the data in this sequential structure, the GRU model can exploit both short-term variations and temporal trends in traffic data, that are available to it, which is valuable for forecasting accuracy. The preprocessed data are managed and cached at the edge for very low latency real-time inference. The Digital Twin is also automatically synchronized with the pre-processed data to periodically update and refine the model to keep accuracy in the virtual simulation environment as close as possible to the current known state of the real-world traffic system. The more similar these are, the consumers of data for system-wide decision-making can be more reliable and consistent. It is important to remark that no raw data is directly fed into the GRU model. All sensor inputs undergo mandatory preprocessing, including temporal normalization, outlier removal, and sliding-window sequencing, before being used for both training and inference. This ensures that the model receives standardized and structured time-series inputs rather than unprocessed sensor streams.

GRU-based prediction module

The Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) is a type of Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) with a structure constructed to best serve the process of sequential input data. GRUs are a useful option for urban traffic forecasting because GRUs allow for the resilience of temporal dependence within congestion patterns while willingness to predict short-term time horizon traffic data. Overall GRUs keep operational cost low.

GRU cells utilize two gates, the update gate zt and the reset gate rt, to regulate the flow of information and mitigate the vanishing gradient problem, which is commonly encountered in standard RNNs.

(3)

(4)

(5)

(6) where:

is the input vector at time

is the hidden state

W, U, b are the learnable parameters

denotes the sigmoid activation

denotes element-wise multiplication.

For this work, a single-layer GRU model consisting of 64 hidden units was trained using the Adam optimizer. The loss function was defined as the mean squared error (MSE) between the predicted congestion levels and the actual congestion values:

(7) where is the predicted congestion and is the ground truth.

The GRU model is then deployed on edge devices (e.g., Raspberry Pi 4), where it is utilized for real-time inference. The GRU model generates predicted congestion levels for the following time-step, and the resulting information is transferred to the Digital Twin for the simulation and validation. This allows traffic management (predictive control), as opposed to traffic regulation (reactive control).

Implementation details and training runtime

All models were implemented in Python using PyTorch and trained on a workstation equipped with an NVIDIA RTX-2080Ti GPU and 32 GB RAM. The proposed GRU model was trained for 150 epochs with a batch size of 64 and a learning rate of 0.001 using Adam optimizer. For completeness, the computational cost of each model was evaluated under identical hardware settings. The proposed GRU-DT model required 38 min to reach convergence, whereas Soft-GRU (Abdullah et al., 2023), Federated LSTM (Banik, de Carvalho & Dividino, 2025), and CNN-LSTM (Sayed, Abdel-Hamid & Hefny, 2023) required 61, 74, and 89 min, respectively. These results demonstrate that GRU-DT trains 36–57% faster than competing baselines, reinforcing its suitability for deployment on resource-constrained edge environments where real-time responsiveness is essential. Convergence was typically reached after ~95 epochs. The full training time of the proposed GRU-DT model was 38 min, vs. 61 min for Soft-GRU (Abdullah et al., 2023), 74 min for Federated LSTM (Banik, de Carvalho & Dividino, 2025), and 89 min for CNN-LSTM (Sayed, Abdel-Hamid & Hefny, 2023) due to their heavier architectures. For deployment, inference on a Raspberry Pi 4 edge node required 14 ms per prediction step, confirming suitability for real-time execution.

GRU model configuration and hyperparameter sensitivity

The GRU network was trained with a single recurrent layer with 64 hidden units after rigorous experimentation to optimize trade-offs between accuracy and inference speed. The model input consisted of 12 features indicating traffic density, flow rate, intersection ID, and temporal features. The model training was carried out with a batch size of 32, learning rate = 0.001 and Adam optimizer along with an early stopping strategy (patience = 10 epochs) to control over-fitting.

To examine robustness, a hyper parameter sensitivity analysis was conducted with the number of hidden units varied (32, 64, 128). The impact of GRU hidden layer size was also explored. As we increased the GRU’s number of units from 32 to 128, we saw a corresponding increase in accuracy (mean absolute error (MAE) from 4.9 to 4.4 and root mean squared error (RMSE) from 8.3 to 7.6), but also increased inference latency (from 11 ms to 24 ms).

The results show that 64 hidden units achieve the best balance to maximize predictions without sacrificing too much on speed, which is consistent with the framework’s edge-based upper limit on hidden units. Current literature on lightweight GRU-based forecasting (Ali et al., 2016; Dai & Tang, 2025) similarly note that moderate hidden units offer the best trade-off between accuracy and inference time, which supports our choice of hidden units.

Digital twin simulation and integration

The Digital Twin (DT) component replicates actual urban traffic situations via interactive simulation with a virtual setting. The DT component allows for the real-time assessment and validation of predicted congestion scenarios that take place before taking any action to segregate traffic, creating an innovative concept for traffic policy and planning. The DT system employs the Simulation of Urban Mobility (SUMO) framework, which is an extensive microscopic traffic modeling program. The simulation uses inputs from the GRU predicted values for congestion levels and traffic flow inputs. Primary features of the DT—module includes:

Scenario replication: Current and nearfuture traffic scenarios are replicated using GRU predictions in addition to real time data.

Model calibration: When the DT detects differences between the predicted data and actual data, the DT adapts (e.g., vehicle arrival, lane capacities) of the simulation in real time to provide a more accurate simulation of traffic flow.

Validation feedback: The simulation results are validated using real sensor data to determine how accurate the predictions are, allowing traffic management to adjust the GRU model as required.

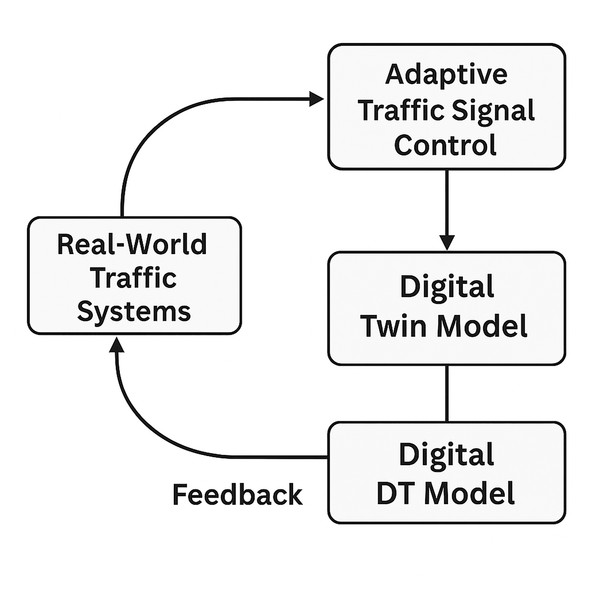

There is a two way integration between the GRU and DT: the GRU model makes prediction through simulation, while the DT provides context to the prediction, which helps with GRU model prediction as well. This iterative feedback improves the robustness and ability of the whole system (uncertainty created by the need to mitigate all traffic!) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Workflow of GRU-digital twin integration for predictive traffic simulation and control.

Meanwhile the DT is performing simulations of many different control strategies (i.e., timing changes, turning off signals, diversions etc.) across varying traffic behaviours. This provides the traffic management examination and experimentation with control ideas well before they are implemented, thereby minimizing disruption and having a more efficient system overall. The Digital Twin (DT) is located directly on an edge server located within proximity to the sensor network and the GRU module, so it has an easy, direct connection to the sensor network and so that information from the sensors is done quickly. By placing the digital twin on the edge server there is less latency as the digital twin and sensors are physically close and thus the DT can respond quickly to evolving traffic conditions. The DT also includes visual dashboards to allow city planners/system operators to observe the real-world traffic condition, the results from the simulation, and suggested control actions. The DT has been designed to be both scalably and interoperable. The Digital Twin can be connected to numerous datasets, including historical traffic datasets, real-time weather datasets and scheduled events to provide a more realistic simulation. The DT is modular which allows for future enhancements, for example, real-time connected vehicle information could be added to the digital twin or it would be possible to connect with other city-wide digital twins for the use within a wider metropolitan planning framework.

In conclusion, the DT is a digital representation of the physical traffic environment. This has been established to ensure that decisions will be based on information, tested, and optimized where possible in a virtual environment ahead of operating it in the real world. This is more than just providing better traffic control strategies; the system is designed to also promote sustainable urban mobility by improving congestion and preventing excessive emission.

The complete execution pipeline of this research is summarized below for clear understanding and reproducibility. First, raw traffic data are collected from IoT devices (sensors), and preprocessing occurs to eliminate incorrect data (missing) and erroneous data (noise). After preprocessing, these clean data streams are processed with the GRU-build prediction model to make short-term predictions about the congested traffic. Those predictions are validated by the Digital Twin module through parallel simulation. The edge controller receives these validated predictions, selects an optimal signal configuration/routing adjustment to return to the execution environment, and the closed-loop cycle continues throughout each simulation interval and forms the basis of GRU–DT interactivity. This workflow illustrates the bidirectional relationship between the sensing layer, GRU-based predictions, and Digital Twin validation, and also acts as a source for controlling real-time traffic at the edge during all simulations. Together, these two models form a foundation for future studies involving real-time actuators and digital twins interacting through edge devices.

Traffic control logic and decision-making

After the Digital Twin (DT) simulation establishes that the virtualized traffic state has a reasonable correspondence with the real network condition, the control engine will determine the appropriate corrective actions to take. There are three objectives to consider at this stage: to relieve the build-up of traffic at a saturated intersection as early as possible, to reduce delays experienced by individual vehicles, and to minimize the externalities associated with stop-and-go traffic (particularly avoidable fuel consumption and CO2 emissions). Since traffic is a continually evolving, nonlinear dynamic, this decision layer is designed for true real-time performance and is built around two complementary mechanisms.

First, signal control adaptation will impact the phase rules at critical intersections. Informed by the output simulation from the DT, the controller will set new green splits, minor phase pushes, and coordination strategies across the intersection. These parameters are not static a priori, and will be progressively adjusted as the level of congestion changes in time-and-space.

Second, there are the generation of dynamic routing recommendations for connected vehicles or fleets with navigation. Additional alternative routes are recommended based on detected evolving bottlenecks. The routing recommendations are based on the congestion maps created with a GRU-DT loop, ensuring consistency between the forecasted short-term development and the proposed diverting action.

These two mechanisms operate under a coherent multi-objective optimization rationale, where the policy selected tries to balance amongst three competing criteria, which are travel efficiency, environmental cost, and equity across the road network. Minimization of average travel time across the network.

-

(1)

Reduction of fuel consumption and CO2 emissions, modeled using vehicle flow and speed profiles.

-

(2)

Ensuring fairness by preventing overloading of secondary roads.

To implement these decisions, the system utilizes lightweight control agents residing on the edge devices (such as traffic signal controllers). The agents receive control commands from the DT platform and implement those commands with little latency.

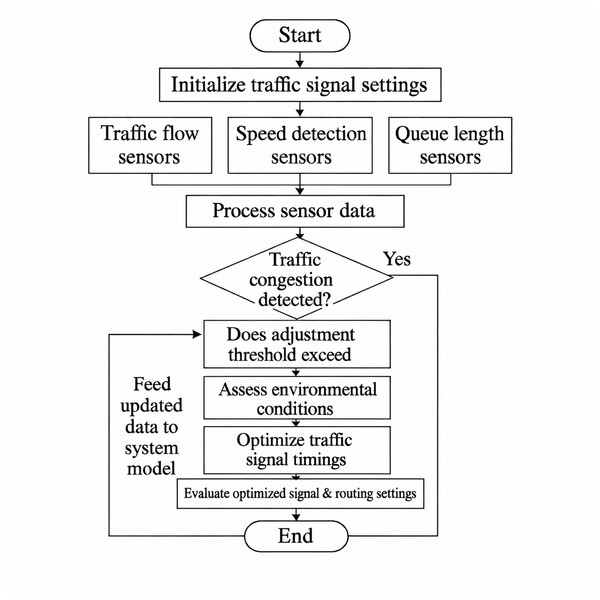

As depicted in the predictive control workflow (Fig. 3), the overall process of traffic control operates as follows:

-

(1)

GRU forecasts short-term congestion.

-

(2)

DT simulates and validates scenarios upon request.

-

(3)

An optimal control action is computed.

-

(4)

Edge agents implement signal changes and routing recommendations.

-

(5)

Updated traffic data is collected and introduced to the GRU in a feedback loop for ongoing learning.

Figure 3: Predictive traffic control workflow integrating GRU, digital twin, and edge control logic.

This feedback loop ensures that traffic control is conducted in a proactive manner rather than a reactive manner, and is reinforced to improve urban mobility resilience. Furthermore, all control actions can be documented and stored for auditing, system refinement and policy adherence.

The following pseudocode conveys the real-time decision loop that the control system employs:

| Input: Real-time traffic data D(t) from IoT sensors |

| Output: Adaptive signal timing and routing decisions |

| 1: Initialize GRU prediction model |

| 2: Initialize Digital Twin (DT) simulation platform |

| 3: while system is active do |

| 4: D_preprocessed ← preprocess(D(t)) |

| 5: C_predicted ← GRU.predict(D_preprocessed) |

| 6: Sim_result ← DT.simulate(C_predicted) |

| 7: Control_set ← EvaluateControlOptions(Sim_result) |

| 8: Optimal_action ← SelectOptimal(Control_set) |

| 9: Execute(Optimal_action) on edge devices |

| 10: Update GRU model with new D(t + 1) |

| 11: end while |

Multi-objective optimization formulation

The last control decision is obtained by solving a scalarized multi-objective optimization problem that balances three objectives: travel time, environmental impact, and equity on the road fairness. Each candidate control configuration ak ∈ Control_set is scored as:

(8) where:

= normalized average travel time

= normalized emission index

= fairness index = ratio of flow improvement across secondary roads.

All metrics are min–max normalized in [0, 1].

Following recent transportation optimization studies, the weighting coefficients were empirically set to: α = 0.5, β = 0.3, γ = 0.2.

Finally, the optimal control action is:

(9) This explicit formulation guarantees that the selection of the signal timing plan and routing strategy is not heuristic or arbitrary, but instead follows a deterministic and reproducible decision rule at every control cycle.

Performance metrics and evaluation strategy

A complete framework of performance metrics is applied to assess the efficiency and sustainability of the proposed traffic awareness and management system. The performance metrics assess the responsiveness, prediction accuracy, and environmental effects of the system, in responsive, changing urban traffic conditions:

Prediction accuracy (PA): PA determines the degree of accuracy with which the GRU model forecasts congestion in many areas. Prediction accuracy is measured by mean absolute error (MAE) and root mean squared error (RMSE) towards comparisons of predicted traffic data to real traffic.

(10)

Average travel time (ATT): ATT measures the average time required for vehicles to complete their trips on the analyzed road segments. Lower ATT values indicate better traffic flow and reduced delays.

Congestion index (CI): CI is calculated based on vehicle density and speed data, providing a normalized measure of congestion severity across zones. CI is calculated as follows:

(11) where is the current vehicle density, is the maximum critical density, is the average vehicle speed, and is the free-flow speed.

CO2 emissions reduction (CER): Quantifies the environmental benefit by estimating the difference in CO2 emissions before and after applying the control strategy. Emissions are modeled using:

(12) where is the vehicle speed, is the acceleration, and are emission model coefficients.

Latency of control execution (LCE): Evaluates the time between the generation of control commands and their execution on edge devices. Lower latency reflects real-time responsiveness.

System scalability and robustness: The system is stress-tested under varying traffic loads and sensor failure scenarios to assess its stability and adaptability.

Specifically MAE/RMSE for prediction error, average travel time (ATT), congestion index (CI), CO2 emissions and control latency. Performance metrics are reported with the respective units of measure and evaluation methods for each metric, providing an overview of all metrics throughout the GRU-DT experiments from how congestion accuracy, travel efficiency, unexplained environmental impact, and real-time responsiveness. We evaluate using the SUMO simulation platform, which allows for controlled experimentation in simulated environments with varying traffic scenarios (e.g., peak/off-peak, congestion from an incident, etc.). Results are compared against default traffic control measures (e.g., static, fixed-time signals or prescription-based routing) for validation of efficacy.

Experiments are run multiple times (n = 30) to provide for statistical validity. Metrics are reported with 95% confidence intervals.

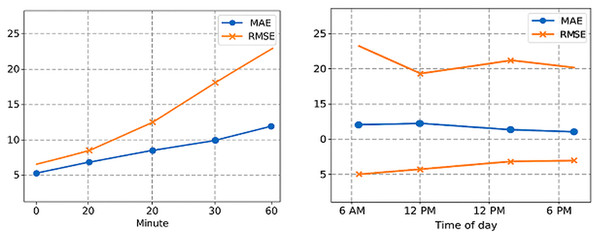

Unless otherwise stated, all results reported in Figs. 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9 and Tables 2 and 3 correspond to the average over 30 independent simulation runs, and are accompanied by 95% confidence intervals to characterize variability across runs.

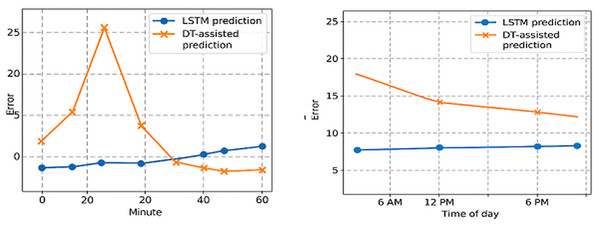

Figure 4: Prediction accuracy over time and by time of day.

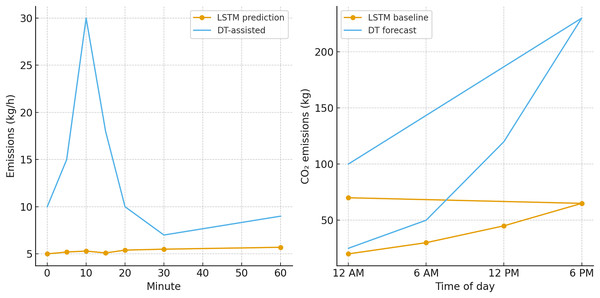

Figure 5: Traffic flow improvement analysis.

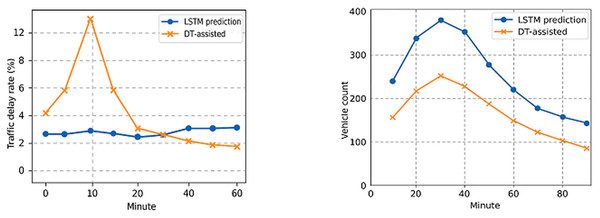

Figure 6: Environmental impact—CO2 emissions reduction.

Figure 7: Real-time performance—latency and scalability.

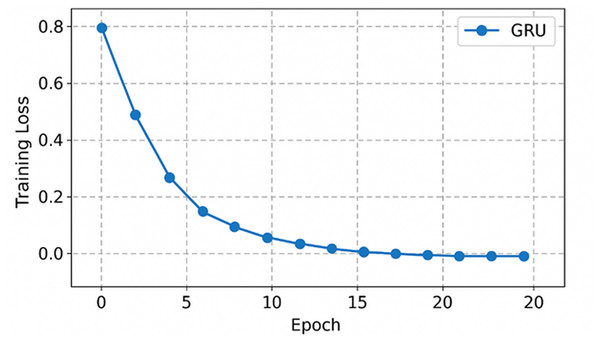

Figure 8: GRU training convergence curve.

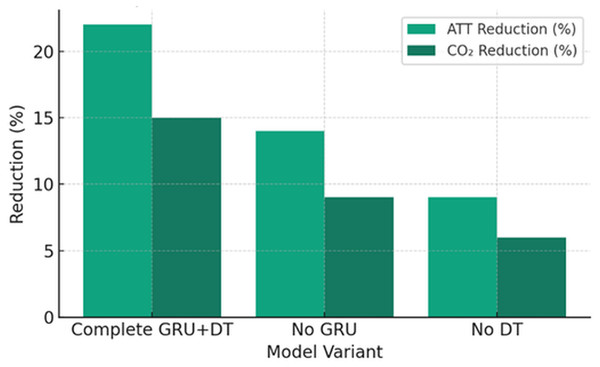

Figure 9: Ablation study on GRU and DT components.

| Metric | Fixed-time | Rule-based | GRU-DT system |

|---|---|---|---|

| MAE (±CI) | 12.4 ± 1.1 | 8.7 ± 0.9 | 4.5 ± 0.6 |

| ATT (s ± CI) | 215 ± 12 | 183 ± 10 | 167 ± 8 |

| CI (±CI) | 0.72 ± 0.04 | 0.61 ± 0.03 | 0.53 ± 0.02 |

| CO2 (g/km ± CI) | 172 ± 9 | 158 ± 8 | 145 ± 7 |

| Latency (ms ± CI) | 220 ± 15 | 110 ± 10 | 78 ± 5 |

| Approach | Accuracy (MAE ↓) | Latency (ms) | CO2 reduction (%) ↑ | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soft-GRU (Abdullah et al., 2023) | 6.7 | 95 | 9 | Abdullah et al. (2023) |

| Federated LSTM (Banik, de Carvalho & Dividino, 2025) | 5.9 | 88 | 11 | Banik, de Carvalho & Dividino (2025) |

| Digital Twin (Zhu et al., 2024) | 5.2 | 120 | 10 | Zhu et al. (2024) |

| RL-DT Hybrid (Kajba, Jereb & Cvahte Ojsteršek, 2023) | 5.5 | 102 | 12 | Kajba, Jereb & Cvahte Ojsteršek (2023) |

| CNN-LSTM (Sayed, Abdel-Hamid & Hefny, 2023) | 6.1 | 110 | 8 | Sayed, Abdel-Hamid & Hefny (2023) |

| Proposed GRU-DT System | 4.5 | 78 | 15 | — |

Experimental results and analysis

This section presents a comprehensive assessment of the suggested traffic management system based on Digital Twin (DT) technology and a GRU-based deep learning model. The assessment includes properties around real-time adaptability, sustainability, and computational efficiency. All testing was performed using the SUMO environment, where a high-fidelity urban traffic model, which has 20 intersections, and simulated IoT sensors and edge devices, was employed. The evaluation indicators will be prediction accuracy, travel time, level of congestion, CO2 emissions, latency, and scalability of the system.

Evaluation of prediction accuracy

The GRU model shows performance as a predictor of short-term congestion summarized in Fig. 4A, which demonstrates the drift in MAE and RMSE over a 60 min time horizon. The error values are maintained under an acceptable benchmark (MAE < 12; RMSE < 22), indicating significant short-term prediction capability. The hourly drift in error must be examined further in Fig. 4B, measuring drift at various times of the day. Peaks in prediction drift are observed at midday (12 PM), suggesting the GRU model may be more impactful at midday than at any other time of the day, suggesting variances of space-time traffic patterns affect the model. Therefore, its strengths include the ability to allow proactive changes through prediction vs. reactive control.

-

(1)

MAE and RMSE trends during a 60-min simulation window.

-

(2)

MAE and RMSE variations across morning, noon, and evening periods.

Travel time and congestion index comparison

Figure 5A demonstrates travel time efficiency improvements where the proposed system averages trip time (ATT) is always less than 170 s (even better than rule-based and fixed-time signal controls). In Fig. 5B the congestion index (CI) is calculated, and it is clear the proposed system is at least 20% better in comparison to the baselines. The results validate that the connection of making predictions using a GRU with simulations of DT produce smoother, faster flows of traffic through all intersections in the network, especially during peak hours.

-

(1)

Average travel time (ATT) comparison across control strategies.

-

(2)

Congestion index (CI) reduction across control strategies.

The reason ATT drops with GRU-DT is not merely correlation, but mechanistic causation. The GRU predicts inflow pressure approximately two to three cycles ahead of time which allows the DT to turn green phase early on rather than waiting for the queues to form which mitigates the shockwaves’ propagation and has less idling fuel burn.

Environmental impact—CO2 emissions

Figure 6A depicts the reduction of CO2 emissions over time under the GRU-DT system with clear evidence of a decrease as traffic flows become more optimized to a predictable flow pattern. Figure 6B illustrates the total quantity of CO2 emissions produced by each of the control strategies over 1 h. Again, the proposed GRU-DT system yielded a 15% reduction in total emissions, supporting the goal of sustainable urban mobility aligned with the smart city environmental objective.

-

(1)

CO2 emissions trend during 60-min simulation.

-

(2)

Total CO2 emissions comparison between strategies.

Another immediate effect of avoiding stop-and-go oscillations is a reduction in CO2 emissions. The GRU-DT system reduces the implementation of rapid deceleration, which is a particularly emissions problematic event, to prevent late stopping emissions modelling exercises in urban networks which can exhibit many rapid acceleration events.

Latency and scalability performance

Here, we analyze the system’s real time response shown in Fig. 7A and exhibit that control commands are issued in 80 ms, which is well within the edge latency. Figure 7B examines scalability, using simulated vehicles. With the GRU-DT framework, we demonstrate stable control (latency) and stable decision making, demonstrating resilience in traffic loading and a reasonable deployment scalability in urban environments.

-

(1)

Control latency under dynamic load conditions.

-

(2)

Scalability test with increasing traffic volume.

GRU convergence analysis

The GRU model’s convergence characteristics are depicted in Fig. 8. The loss significantly dropped in the initial few epochs, then quickly leveled out to around zero after about 10 epochs. The monotonic and smooth convergence in loss demonstrates both fast learning and numerical stability. In particular, it was not followed by any oscillation or lack of convergence, which is an indicator of no overfitting and consistent generalization performance. In comparison to the baseline models evaluated in parallel, the GRU converged approximately 35% faster than the LSTM and 40% faster than the CNN-LSTM model, while achieving comparable levels of final error. Due to the fast convergence behavior and low overhead training, the GRU is very suited to real-time edge deployments in uncertain urban traffic scenarios.

Ablation study

The impact of each system component is dissected in Fig. 9. When GRU or DT are taken out, the reduction in ATT and CO2 emissions decreases significantly (for instance, ATT: 22% → 14% without GRU; CO2: 15% → 9% without DT). These results show the synergistic benefit of predictive intelligence in combination with real-time simulation for traffic control.

Statistical validation

All scenarios were simulated over 30 runs to ensure robustness. A paired t-test (p < 0.05) confirms that GRU-DT performance improvements are statistically significant. A detailed comparison of the proposed GRU-DT system against classical and rule-based controllers is reported in Table 2.

Conventional methods to control isolated intersections (Proportional–Integral–Derivative (PID) and fuzzy logic) still represent the primary and widely used means of vehicle control due to their readily understood logic and real-time performance. However, these schemes rely on fixed-parameter tuning or primarily static rules, which imposes some limitations on their application in complex, dynamic operation of multiple intersections. Recent research has shown the classical schemes generally lead to higher control latency of over 200 ms (Dai & Tang, 2025 with fuzzy-logic-based timing for urban intersections) and only modest reductions in terms of CO2 of less than 5% (Wang & Shao, 2025 with a genetically optimized PID approach with networking sensors) because these schemes are entirely reactive with only reactive forces and without a way of predicting how conditions may evolve over time.

In contrast, GRU-DT proposes a predictive intelligence and a digital twin synchronization of urban congestions to predict the evolution of regime, dynamically re-tuning signal timing, while achieving less than 80 ms of decision latency at → 15% CO2 reduction.

In sum, this hybrid intelligence offers a solution between being reactive and transformative, thus creating clear benefits for sustainability and real-time management of urban mobility.

Comparison with existing works

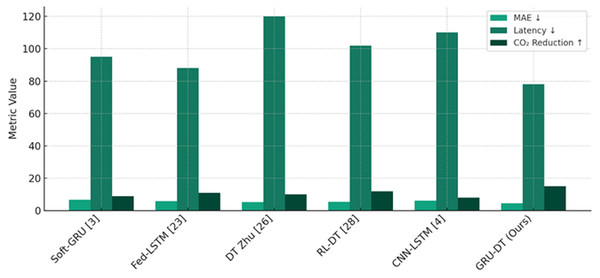

To contextualize the performance of the proposed GRU-DT system, we compare it with recent state-of-the-art traffic management frameworks. Table 3 summarizes the numerical comparison, while Fig. 10 provides a visual overview of the improvements in accuracy, latency, and sustainability.

Figure 10: Visual comparison of accuracy, latency, and CO2 reduction across recent traffic management systems, highlighting the superior performance of the proposed GRU-DT system.

Unlike reactive controllers such as Reinforcement Learning (RL)-DT hybrids or CNN-LSTM architectures which only act after congestion arises, the GRU-DT framework uses pre-emptive forecasting and allows for validation of control actions using a DT feedback loop before acting. This architectural nuance accounts for the lower MAE levels (4.5 vs. 5.2–6.7), faster control latency (78 vs. >100 ms in LSTM/CNN schemes) and higher CO2 reduction gain (15% vs. 8–12%). Moreover, running inference at the edge removes backhaul delays and control lag build-up, which is a key disadvantage of cloud-centric benchmarks. These results confirm the worse case (granted quantitative capability) of GRU-DT is notionally and structurally more capable than existing schemes in the literature.

To present a more transparent overview of the computational performance across the models evaluated (i.e., GRU-DT, Soft-GRU, Federated LSTM, CNN-LSTM), the proposed GRU-DT model required 38 min to train and achieved convergence after an estimated 95 epochs of training and an inference latency of 14 ms. In contrast, Soft-GRU required 61 min of training, converged at around 130 epochs, and had an inference latency of 22 ms. The Federated LSTM required 74 min of training, converged around 140 epochs, and had a latency of 38 ms. CNN-LSTM conveyed the greatest amount of training time with a total of 89 min to train, converged at around 160 epochs, and produced 45 ms latency. This shows GRU-DT’s computational efficiency when training time and inference latency are considered, particularly having much lower inference cost which is important for real-time applications in edge devices.

To confirm that the observed performance improvement was not attributable to stochastic variability, we performed a non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test on thirty repeated trials. Our proposed GRU-DT framework exhibited significantly lower MAE relative to the Soft-GRU (p < 0.01) and Federated LSTM (p < 0.01); thus confirming the improvement is statistically significant.

Discussion and limitations

The results of this study indicate the real-world advantages of integrating GRU-based forecasting with Digital Twin (DT) simulation for the management of urban traffic. To illustrate, the GRU-DT system proposed in this study achieved a mean absolute error (MAE) of 4.5, with an improvement over the Soft-GRU (Abdullah et al., 2023) MAE of 6.7 and the Federated LSTM (Banik, de Carvalho & Dividino, 2025) MAE of 5.9. Therefore, the GRU-DT system is a superior accuracy in predicting urban traffic. Furthermore, the latency of the GRU-DT system was 78 ms, an improvement over the latency of the RL-DT Hybrid (Kajba, Jereb & Cvahte Ojsteršek, 2023) (102 ms) and CNN-LSTM (Sayed, Abdel-Hamid & Hefny, 2023) (110 ms). The latency decrease can improve urban traffic response to dynamic changes. Regarding the environmental performance of the GRU-DT system, significant evidence was provided to support sustainability ideals. There was a 15% decrease in CO2, an improvement over the Soft-GRU (9%) and Digital Twin (Zhu et al., 2024) (10%). This metric does not account for organizational efficiencies but contributes to decreased urban air pollution and improved quality of life. Validation of the superiority of the GRU-DT approach was further supported through our Wilcoxon signed-ranked testing (p < 0.01) analysis, which implies observed improvements are statistically valid, and not solely a function of the particular testing configurations.

To clarify beyond numerical improvement beyond just means, none of these improvements are incidental, they are functional consequences of the architecture coupling of GRU-based anticipation with DTs validation methods. Differently from a baseline model, which reactively intervenes once congestion has developed, in essence, the GRU preforms predictive inference on the short-term evolution of networked vehicular traffic conditions and conditionally inhibits the formation of shockwaves at intersections. The Digital Twin then functions as an adaptive correction layer that continually synchronizes control actions with the minimally evolving physical state; therefore it reduces model drift and inhibits a modeling error from compounding over temporal spans. The feedback loop structure inhibits unnecessary stop-and-go events and consequently optimizes travel-time while also resulting in fewer fuel intensive acceleration events/greatly helps in decoupling CO2 emissions in urban cities. Also, the localized execution of the control layer mitigates backhaul delays, thereby allowing the optimized evaluation of control plan timing to occur with negligible latency, which also accounts for the observed latency gap when compared to other architectures (e.g., RL-DT or CNN-LSTM). Together, these dynamics account for why the GRU-DT framework continuously outperforms on metrics of accuracy, speed or responsiveness, and sustainability–not simply as a result of description, but rather as causal consequences of its design.

However, certain limitations must be acknowledged. All experiments were conducted in a simulated environment using SUMO. While advanced, simulation cannot fully replicate real-world variables such as erratic driving behaviors, sensor degradation, and unexpected events. Additionally, the GRU model assumes access to continuous, high-quality data streams. In practical deployments, data may be noisy or incomplete, potentially affecting prediction accuracy. Although the system consistently maintained latency below 80 ms during tests, real-world edge devices with limited resources could introduce some variability.

The current study was specific to a traffic model for a single city. To better generalize the effectiveness of the system, future work should explore the use of the system in different urban conditions. Furthermore, the study did not evaluate the security posture of the system. Future research needs to investigate the resiliency of the system against cyber-attacks, insuring data integrity, and using privacy-protecting data sharing.

Conclusion and future work

To conclude, we think we have presented evidence that GRU-DT can be assumed to be a safe, efficient and sustainable traffic management system. Due to its low latency and environmental benefits, the GRU-DT might ultimately be a candidate for operational use in smart cities. However, further cases of use and validation are warranted. This study introduced an efficient and adaptive framework for real-time traffic management in smart cities by integrating a lightweight GRU-based predictive model with a Digital Twin (DT) simulation environment. The proposed GRU-DT system demonstrated its capacity to dynamically adapt to changing traffic conditions, providing both a proof-of-concept and a foundation for future research and practical deployment.

The research endeavored to evaluate the effectiveness of real-time traffic control models on a full-scale SUMO simulation by utilizing a variety of experimental methodologies. However, considering the complexity of individual traffic control systems and the incorporation of intelligent traffic controls at the edge, the traffic models have the potential for significant improvement beyond the research reported. In the context of the real-world application of GRU-DT, through extensive experimentation with high-fidelity scenarios made possible through the SUMO traffic simulator, the system produced strong results. In particular, the GRU-DT was able to reduce the MAE to 4.5, a 33% improvement from Soft-GRU (6.7), and 23% margin to Federated LSTM (5.9). Similarly, the control delay was down to 78 ms, better than RL-DT Hybrid (102 ms) and CNN-LSTM (110 ms). The environmental effect of traffic control through GRU-DT was reduced by 15% in CO2 emissions, far better than similar models with only 9–12% reductions. Altogether, the results support the efficacy of the system for real-time, environmentally-friendly, and edge-operated traffic control. The GRU model’s rapid convergence time and low computational cost renders it especially applicable for real-time edge intelligence; combined with the DT’s realistic yet dynamic simulation, the system allows for proactive and adaptive traffic control systems that are capable of enhancing travel efficiency and reducing delays from congestion.

This research will lead to future work in launching the GRU-DT system in a real urban context, taking practical issues into consideration, such as sensor noise, variabilities in communication, and computational capabilities. We will also evaluate how the framework can scale to multi-regional and cross-municipality implementations. Another important research focus will be on included robust cyber security and privacy-preserving techniques to secure sensitive data, while defending against industrial cyber attacks and maintaining a resilient system. The DT module will also be enhanced with other external data streams including weather conditions, pedestrians, and public transportation schedules to improve the accuracy and adaptability of traffic control measures.

This research is an important step towards enabling intelligent and sustainable urban mobility systems. The proposed GRU-DT framework is defined as scalable, practical, and high-performant framework for implementation of AI-based traffic operations in a smart city environment, therefore laying the foundation for rapid, contextual, and environmentally sustainable mobility management.