Risk-aware diffusion model for generating extreme weather scenarios and safety evaluation in autonomous driving

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Giovanni Angiulli

- Subject Areas

- Algorithms and Analysis of Algorithms, Artificial Intelligence, Autonomous Systems, Data Mining and Machine Learning, Neural Networks

- Keywords

- Risk-aware diffusion model, Extreme weather scenario generation, Autonomous driving safety, Safety evaluation, Deep generative models, SafeBench

- Copyright

- © 2026 Tu et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2026. Risk-aware diffusion model for generating extreme weather scenarios and safety evaluation in autonomous driving. PeerJ Computer Science 12:e3573 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3573

Abstract

Extreme weather scenarios, are likely to cause safety hazards such as perception failures and decision-making anomalies. These scenarios are indispensable for the safety assessment and robustness testing of autonomous driving systems. Most existing scenario generation methods focus on manually defined rules or parameter perturbations, which makes it difficult to simultaneously ensure risk, physical plausibility, and diversity. In this study, a risk-guided diffusion model (RADM) is proposed to automatically generate high-risk and challenging weather test samples. Through multiple rounds of feedback, the generated distribution is optimized so that the samples increase collision risk while maintaining diversity and physical reasonableness. The SafeBench platform is used to validate the effectiveness of RADM in improving collision rates, expanding sample distribution coverage, and ensuring scenario usability. Experimental results show that RADM can efficiently and automatically generate extreme weather test samples for a wide range of autonomous driving testing systems, demonstrating strong potential for real-world applications.

Introduction

The safety verification of autonomous driving systems primarily relies on testing in diverse, complex, and extreme traffic scenarios (Wang et al., 2024). However, high-risk scenarios in real-world environments—such as extreme weather, rare obstacles, and complex traffic interactions—are inherently scarce and difficult to capture or reproduce. Traditional testing methods, which depend on manual data collection or passive playback, face significant limitations in terms of efficiency and scenario coverage (Saluja et al., 2020). Therefore, it is challenging to obtain sufficiently rich, extreme, and challenging test scenarios using capture-replay methods, leading to a shift in research focus toward data-driven automatic generation techniques (Park et al., 2019). Consequently, efficiently generating diverse and representative high-risk test samples has become a critical issue in the field of autonomous driving safety verification.

In recent years, with the widespread adoption of deep generative models, data-driven automated scenario generation has emerged as a crucial tool for enhancing the efficiency and expressiveness of autonomous driving simulation testing. Currently, methods such as Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) (Creswell et al., 2018), Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) (Wei et al., 2020), and Diffusion Models (Yang et al., 2023) have been widely applied in traffic flow simulation, anomaly event synthesis, and multi-agent interaction scenario generation. For example, Jin et al. (2022) proposed GAN-based traffic flow prediction, Chen et al. (2021) utilized TrajVAE to optimize trajectory diversity generation, and the Pronovost et al. (2023) applied VAE and diffusion models for automated generation of autonomous driving scenarios, effectively enhancing diversity and complexity. However, existing generation methods generally have two major limitations: first, the generated samples are concentrated in low-risk areas and cannot cover extreme rare scenarios; second, they lack proactivity and controllability in modeling high-risk events and cannot systematically expand safety boundaries (Sun et al., 2023). Specifically, current mainstream deep learning-based generation methods can only passively reconstruct or amplify historical observation distributions, resulting in extremely low proportions of “long-tail scenarios” such as high-risk weather conditions and rare accidents in generated samples, failing to meet the demands of extreme safety testing (Yang et al., 2022). Rule-driven synthesis methods, while capable of manually specifying scenario types, often suffer from issues such as insufficient sample diversity or distorted scenario structures, resulting in generated outcomes that fail to cover complex real-world conditions, thereby reducing the effectiveness and persuasiveness of testing (Aibar et al., 2017; Feng et al., 2022).

Virtual simulation platforms play a central role in autonomous driving testing.

Platforms such as CARLA (Pérez-Gil et al., 2022), MetaDrive (Li et al., 2022), and LGSVL (Rong et al., 2020) provide efficient, low-cost, and controllable testing environments for autonomous driving through high-fidelity environments and multi-agent interactions. SafeBench (Xu et al., 2022) introduces various long-tail scenarios, advancing the standardization of high-risk autonomous driving testing. However, these platforms are fundamentally built upon static scenario specifications, meaning that environmental conditions—such as weather, illumination, fog density, and traffic participant behaviors—are manually configured or selected from fixed templates before simulation begins and remain unchanged throughout the evaluation. In such static settings, the scenario does not evolve according to the agent’s performance, safety degradation, or emerging risk patterns, which limits the system’s exposure to rare or extreme natural conditions. In contrast, the method proposed in this work dynamically adjusts weather configurations through iterative risk feedback, enabling the simulator to explore previously unseen and realistic extreme-weather conditions instead of relying on fixed predefined settings.

Deep generative models have increasingly become a key direction for autonomous driving scenario synthesis. Models such as SceneGen (Tan et al., 2021) and TrafficGen (Feng et al., 2022) can learn real traffic distributions to enhance diversity and physical plausibility, but they struggle to increase the generation probability of samples in high-risk areas and have limited coverage of extreme environmental disturbances. Additionally, diffusion models demonstrate unique advantages in modeling extreme low-probability region distributions through progressive noise perturbation and backtracking sampling mechanisms (Yang et al., 2022). Meanwhile, techniques such as classifier-free guidance (Ho & Salimans, 2022) and cross-attention mechanisms (Li & Wu, 2024) effectively integrate information from maps, weather, and risk feedback to achieve directed guidance. Methods such as CLIP-guided diffusion (Kim, Kim & Lee, 2025), Talk2Traffic (Sheng et al., 2025) and AdvDiffuser (Xie et al., 2024) combine the advantages of the above models and achieve semantic consistency or risk-related enhancement through external evaluators or simulation feedback, effectively improving the sampling probability of extreme high-risk events (Zhang et al., 2022). Nevertheless, these models remain limited to static screening and single-round optimization, lacking dynamic adaptive focusing and multi-round risk feedback mechanisms (Wynn & Eckert, 2017), making it challenging to achieve continuous coverage and diversity optimization. In contrast to existing risk-guided diffusion frameworks that employ static, single-pass conditioning, the proposed risk guided diffusion model (RADM) leverages a closed-loop feedback structure between the diffusion generator and the external risk evaluator. Through multi-round iterative refinement, the model adaptively shifts its sampling distribution toward high-risk yet physically valid regions, enabling dynamic optimization beyond the capabilities of prior one-shot guided diffusion approaches.

Existing reinforcement learning autonomous driving algorithms (e.g., Twin Delayed Deep Deterministic policy gradient (TD3), Soft Actor-Critic (SAC), Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO)) typically rely on static predefined test scenarios during safety testing (Duan et al., 2021; Schulman et al., 2017; Xu et al., 2024). Recent advances such as VLM-RL (Huang et al., 2024) and VL-SAFE (Qu et al., 2025) extend reinforcement learning toward multimodal and safety-aware frameworks by integrating vision–language models for semantic reward generation and safe policy optimization. These methods, however, focus mainly on decision-level safety learning rather than environment-level scenario generation. Although various scene generation methods based on rule perturbation, parameter sampling, symbolic modeling, and reinforcement learning perturbation have emerged in recent years (Aibar et al., 2017; Feng, Sebastian & Ben-Tzvi, 2021), these methods artificially perturb parameters of traffic participant behavior, environmental attributes, or decision logic, thereby revealing some vulnerabilities and safety boundaries of certain strategies to a certain extent. However, overall, these methods primarily focus on changes at the control or semantic layers, with limited modeling capabilities for complex physical environments. They struggle to actively generate natural high-risk scenarios such as extreme weather, low visibility, or road anomalies, and cannot systematically capture potential failure modes of decision-making algorithms under extreme challenge conditions. Meanwhile, as the requirements for the safety and robustness of autonomous driving systems continue to increase, how to efficiently generate dynamic test scenarios that cover long-tail high-risk events has become a focus of attention in both industry and academia. Relying solely on static sampling or rule perturbations not only faces the problem of limited scenario coverage but also makes it difficult to conduct targeted and systematic exploration of model vulnerabilities. Therefore, there is an urgent need for an intelligent scenario generation mechanism that can both accommodate environmental complexity and dynamically focus on system risk boundaries. Against this backdrop, combining deep generative models with risk perception mechanisms has emerged as a new research trend. Related studies (Ho & Salimans, 2022; Li & Wu, 2024; Yang et al., 2022) indicate that deep generative techniques such as diffusion models and generative adversarial networks can achieve efficient sampling under extreme conditions and rare events through distributed modeling. By incorporating risk feedback information such as collision rates and performance degradation, the coverage and challenge of generated samples regarding system vulnerabilities can be further enhanced.

To address these challenges, this article proposes an innovative RADM that incorporates external risk metrics such as collision probability and potential loss as dynamic sampling weights directly into the diffusion generation process (Lew et al., 2022), enabling reinforced sampling and active exploration of high-risk extreme events (Shabestary & Abdulhai, 2022). The model uses the diffusion process to model the high-dimensional state space of the traffic environment, adjusting the sampling distribution through risk-guided and adaptive feedback to effectively expand the coverage of extreme low-probability, high-risk events. Compared to traditional methods, RADM not only improves the probability and physical plausibility of high-risk scenario generation but also significantly enhances the simulation platform’s ability to challenge extreme conditions, driving the automation and intelligence of safety testing.

The main contributions of this article are as follows:

(1) RADM is proposed, which incorporates an external risk metric mechanism to focus generated samples on high-risk regions near the system boundary, thereby effectively enhancing the efficiency and diversity coverage of extreme scenario generation. (2) The generation process is guided by multi-dimensional modeling, including collision safety, functional performance deviation, and consistency with physical constraints, which improves the challenge, plausibility, and test validity of the generated scenarios. (3) Systematic experiments are conducted on the SafeBench platform in conjunction with mainstream reinforcement learning-based autonomous driving algorithms. Experimental results demonstrate that RADM outperforms existing methods in autonomous driving safety assessment, enhances system robustness, and highlights its potential for real-world applications.

The rest of the article is organized as follows. The “Methods” section provides a detailed description of the dataset used in this study, the design principles of the RADM, the main algorithmic process, and the simulation and evaluation methodologies. The “Results” section presents the experimental setup, the evaluation index system, and the experimental results, and analyzes the performance of RADM in the safety assessment of autonomous driving under extreme weather conditions. The “Discussion” section elaborates on the main findings and their practical significance, identifies the limitations of this study, and offers an outlook on future research directions and autonomous driving simulation tests. Finally, the “Conclusion” section summarizes the innovative contributions of this work and suggests possible avenues for future research.

Methods

RADM framework

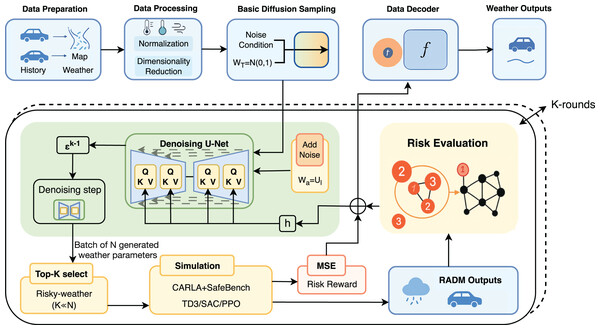

The RADM proposed in this article is capable of generating weather samples that comply with physical laws, exhibit diverse distributions, and present significant challenges. By introducing a multi-round risk feedback mechanism and a task-oriented optimization strategy, the model achieves adaptive migration of the generation distribution toward high-risk regions, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The experimental design adopts a phased validation approach. First, the model uses historical meteorological observation data and geographic information features to perform initial sampling in the high-dimensional meteorological parameter space, generating a candidate set of weather samples. Subsequently, this sample set is imported into the SafeBench simulation platform and tested in conjunction with the autonomous driving decision-making system, with quantitative recording of key performance indicators such as collision probability and path completion rate. The risk assessment module employs the analytic hierarchy process (AHP) to quantitatively evaluate the risk of candidate samples and implements a sample screening strategy based on risk scores, prioritizing the retention of high-risk weather scenarios for model optimization. During the iterative optimization process, the model dynamically adjusts the sampling distribution to gradually enhance the coverage of high-risk regions. After several rounds of optimization, the model can stably generate a representative and diverse set of high-risk weather samples. This sample set effectively supports the safety assessment and robustness verification of different autonomous driving strategies under complex weather conditions.

Figure 1: RADM framework with SafeBench feedback.

Overview of the RADM framework. After inputting vehicle, weather and map data, the system generates diversified weather scenarios through the diffusion model, and combines risk assessment and simulation feedback to filter high-risk weather and achieve K-rounds of iterative optimisation.Data preparation and processing

To support automatic generation and systematic evaluation of high-risk weather scenarios, a standardized meteorological dataset was constructed on the SafeBench platform. The raw data originate from the China National Meteorological Data Centre (CMA) and are collected from historical measurement records of several meteorological observation stations, ensuring strong physical consistency and realistic representativeness. We selected 13 key meteorological factors from the public interface, including barometric pressure, sea level pressure, maximum barometric pressure, minimum barometric pressure, maximum wind speed, wind direction of maximum wind speed, 2-min average wind speed, 2-min average wind direction, air temperature, maximum temperature, minimum temperature, relative humidity, and precipitation over the past 3 h.

To meet the input requirements for model generation, all variables were normalized and standardized after collection, and converted into structured training samples, which ultimately constitute the input distribution for the diffusion model. On the simulation platform, these data are organized into the yaml format, supporting automatic loading and scenario injection of diverse weather combinations across multiple experimental rounds. This effectively improves the flexibility and reproducibility of high-risk test scenarios.

Different weather conditions have direct and measurable effects on the perception, planning, and control modules of autonomous driving systems. In CARLA and SafeBench, these effects are expressed through physically based environmental parameters that influence the sensing quality and vehicle–road interaction. Heavy precipitation and high surface wetness reduce tire–road friction, increasing braking distance and causing instability during high-speed maneuvers. Fog and low visibility degrade LiDAR returns and camera contrast, leading to incomplete object detection and delayed hazard recognition. Extreme cloudiness and low sun altitude introduce illumination inconsistencies and glare, which further increase perception uncertainty. Strong winds result in lateral disturbances that affect vehicle stability and steering control. These environment-induced perturbations propagate through the perception and prediction modules and ultimately alter the vehicle’s downstream decisions, increasing the likelihood of unsafe behaviors such as late braking, lane deviation, or collision. This physical-decision coupling provides the foundation for risk evaluation in RADM and ensures that the generated weather samples meaningfully influence autonomous driving behavior.

Although CARLA does not implement fully physics-accurate camera or LiDAR sensor models, its environmental rendering and vehicle–road interaction models have been widely validated for autonomous-driving research. Prior works based on CARLA and SafeBench demonstrate that variations in weather parameters—such as precipitation, fog density, cloudiness, and surface wetness—produce consistent and measurable changes in perception quality, visibility range, and vehicle stability. These effects are sufficient to alter the downstream behaviour of autonomous agents, including object-detection reliability, braking timing, lane-keeping performance, and collision likelihood. Therefore, RADM does not rely on high-fidelity replication of real sensor physics. Instead, it leverages CARLA’s behaviour-level sensitivity to environmental changes, which provides a reliable and widely adopted proxy for evaluating how extreme weather conditions influence autonomous-driving decisions at the control and planning levels. This design is aligned with standard practice in existing scenario-generation benchmarks such as SafeBench.

Design of training objectives

Specifically, given the driving environment , the policy under test , and the initial state trajectory , the test scenario can be modelled as follows:

(1)

Here, and denote the joint state and action of all vehicles at time , respectively. The state is typically parameterized by vehicle position, speed, and heading, while the action is characterized by steering angle and acceleration.

In conventional autonomous driving systems, the control objective is typically to minimize an overall cost function , such as collision rate, path deviation, or ride comfort. In this study, our optimization objective is instead to maximize this function by generating high-risk weather parameters that increase the probability of failure for the system under test. This task can be formally defined as follows:

(2)

That is, it is to proactively search for weather configurations that significantly enhance the risk of the system under a specific map and autopilot strategy .

RADM diffusion generation and training

Our diffusion framework follows the denoising diffusion probabilistic model (DDPM) proposed by Ho, Jain & Abbeel (2020), which models data generation as a Markov chain that gradually perturbs samples with Gaussian noise and then learns to reverse this process to recover the clean data distribution. Building upon this foundation, the diffusion generative network in RADM is designed to learn the mapping from Gaussian noise to weather configuration vectors through iterative denoising. The model extends the standard DDPM by introducing risk-guided conditioning and multi-round feedback adaptation, allowing it to bias the reverse diffusion process toward safety-critical weather configurations rather than reconstructing neutral samples.

In the forward diffusion stage, the model gradually adds noise to the original weather vectors through a Markov process, and the perturbation at each step is described by the following equation:

(3)

Here, is the cumulative noise scheduling parameter and is 13-dimensional meteorological feature vectors. As increases, the weather features are smoothly mapped into Gaussian space, which enables the model to comprehensively explore the weather space.

The core generative capability of the model lies in its conditional U-Net structure. In the reverse (backpropagation) phase, the U-Net receives the noise-perturbed weather features , time steps t, and context conditions as inputs, and predicts the noise terms required for denoising. The network’s optimization objective is to minimize the denoising error:

(4)

In each round of reverse sampling, the model is recursively fed into the denoising network using the noise prediction from the previous step and the current intermediate state , achieving gradual correction and approximation of the target distribution. Each input determines the generation path of the current weather sample until it ultimately converges to a high-risk weather sample, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The recursive process can be described as follows:

(5)

Here, is the predicted noise from the previous iteration, and represents the condition information. The process iterates until , yielding the final weather sample.

The U-Net employs a typical symmetric “encoder-decoder” structure, which continuously downsamples features during encoding and retains local information through skip connections. To enhance higher-order representations in weather generation, the U-Net introduces a query-key-value (QKV) attention mechanism at multiple scales, whose core operations are as follows:

(6)

Here, QKV are obtained from network features through linear transformation, and the attention weights accurately capture dependencies between different weather features. In addition, to improve the model’s adaptability to historical information and scene conditions, the U-Net layers employ an Adaptive Normalization (AdaGN) mechanism, which transforms the condition information h into scaling and bias parameters injected into the network as follows:

(7)

In this way, each step of feature mapping is adaptively informed by environmental and historical context, thereby improving the modeling of extreme weather conditions.

All generated samples undergo physical feasibility checks and interval CLIP operations at the output stage to ensure that weather parameters do not exceed actual simulation boundaries. The introduction of a physical consistency regularization term allows the network to continuously suppress physically implausible outputs during generation. The regularization loss is formulated as follows:

(8)

Here, is the regularization weight for each meteorological variable, denotes the physical boundary, and represents the allowed tolerance range.

The training objective of RADM is to jointly optimize the denoising reconstruction error, the physical regularization term, and the subsequent risk reward term through an overall loss function:

(9)

In the early stage of training, the model initially focuses on denoising and physical regularization optimization, followed by the gradual introduction of a high-risk reward term that drives the sampling distribution to continuously and adaptively cluster toward extreme regions. All final generated samples are inverted and output as Risky-weather, entering the subsequent simulation and feedback closed loop. As shown in Fig. 1, the model structure and simulation evaluation process form a complete automated closed loop.

It is important to clarify that the CARLA simulator is not embedded in the gradient update process of the diffusion model. Instead, RADM is built on the SafeBench platform, which provides a modular and asynchronous simulation architecture with four nodes—Agent, Scenario, Evaluation, and Ego Vehicle. In this framework, CARLA runs only within the Evaluation Node, where it executes autonomous driving tests and records safety metrics such as collision rate, completion ratio, and red-light violations for each generated weather configuration. The simulator functions as an independent evaluation module, separated from the diffusion model’s training loop. The diffusion model and the risk assessment network are trained using the simulation results after each generation round, ensuring that CARLA is called only once per round rather than for every diffusion step. This design avoids real-time coupling between simulation and optimization, allowing RADM to maintain high physical fidelity while keeping the computational cost practical—about 3 h per feedback round on an NVIDIA RTX 4090.

Through the integrated use of a deep U-Net architecture, attention mechanisms, and conditional normalization, RADM demonstrates excellent capability in modeling and generating extreme scenarios, providing strong technical support for extreme testing and safety assessment of autonomous driving systems.

Risk feedback mechanism and high-risk sampling

In the closed loop of RADM generation, multiple rounds of risk feedback and high-risk sampling mechanisms jointly construct a dynamic and adaptive optimization process. Each round of diffusion-generated weather samples is rigorously tested on the simulation platform and receives corresponding safety feedback. For each set of weather parameters generated by the model, , we use the CARLA+SafeBench simulation environment to conduct comprehensive autonomous driving tests and record risk indicators such as collision rate and failure frequency, denoted as .

The overall risk score is computed as a weighted combination of two normalized indicators obtained from SafeBench–CARLA: the collision rate ( ) and the route completion ratio ( ):

(10) where balances safety violations and task completion. These statistics are stored offline and later used as supervised labels for training the risk assessment network. This ensures that CARLA simulation is executed only once per feedback round, rather than being embedded inside the gradient loop of diffusion training.

These feedback signals not only provide realistic safety information for subsequent risk modeling, but also serve as the foundation for reward guidance during training. As shown at the bottom of Fig. 1, simulation feedback and high-risk screening together drive multiple rounds of closed-loop optimization.

To efficiently estimate the safety risk of generated weather conditions during the refinement process, RADM employs a data-driven risk prediction model implemented using a random forest regressor rather than a neural network–based predictor. The model is trained offline on previously collected weather–risk pairs , where the risk values are obtained from SafeBench simulations. The random forest consists of 100 decision trees, allowing it to capture nonlinear interactions among meteorological variables such as precipitation, humidity, fog density, wind speed, and temperature-derived features represented in the weather vector. Owing to its ensemble structure, the model does not rely on gradient-based optimisation or epoch-driven training; instead, it is fitted directly using scikit-learn’s bootstrapped sampling and feature-subspace splitting strategy.

Once trained, the random forest serves as a fast surrogate risk evaluator that assigns an estimated risk score to any newly generated weather vector, eliminating the need to run CARLA simulations during the diffusion training loop. Let denote the random forest predictor. For each generated weather sample , the predicted risk is computed as

(11)

These predicted scores enable efficient prioritisation of high-risk candidates. During each refinement round, all generated samples are ranked according to , and the most hazardous subset is selected for full CARLA evaluation. Formally, the Top-K selection among the generated batch is written as

(12)

The average predicted risk of the batch defines the risk-aware reward signal used in training,

(13) which encourages the generator to explore weather configurations associated with higher estimated danger. By combining predicted risk scores for rapid screening and simulation-derived risk values for accurate supervision, RADM achieves efficient high-risk sampling without requiring real-time simulator calls at every generative step.

This reward is incorporated as a negative term in the RADM joint loss function, with its influence controlled by the weight parameter :

(14)

This combination of simulation feedback and neural network risk prediction greatly improves the efficiency and generalization of high-risk sampling, enabling RADM to directly batch-screen and reward-guide extreme weather scenarios without requiring real-time simulation at every step.

In successive feedback loops, RADM is continually reinforced by new high-risk samples, and its predictive capability is synergistically enhanced along with its sampling ability, enabling the system to adaptively evolve toward increasingly challenging weather distributions. This close integration of theoretical modeling and engineering implementation provides a solid technical foundation for the efficient mining and safety verification of extreme autonomous driving scenarios.

The implementation of RADM is based on PyTorch, and the diffusion generative model adopts a lightweight SimpleMLP architecture. At each diffusion step, the noisy sample and the normalised time step are concatenated and passed through a two-layer fully connected network with ReLU activations to predict the additive Gaussian noise. The model is trained for 100 epochs using the Adam optimiser with an initial learning rate of 1 × 10−3, a batch size of 64, and a linear beta schedule containing 1,000 diffusion steps, following the standard DDPM training procedure. This configuration provides stable optimisation across different timestamps and ensures that the noise predictor converges reliably. All experiments are conducted on a workstation equipped with an NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU. The training pipeline supports iterative refinement through repeated cycles of weather-sample generation, simulation evaluation, and distribution updating, enabling the model to gradually focus on weather patterns associated with higher levels of safety risk while maintaining computational efficiency.

Results

Risk assessment

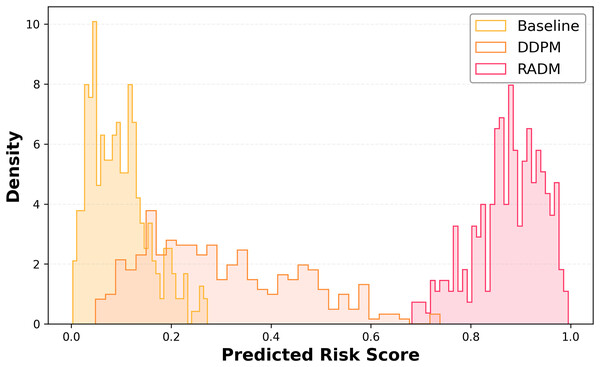

A trained risk prediction model is employed to assess the potential collision probability of each generated sample, and a probability distribution is plotted to evaluate the aggressiveness of the scenarios. Whether the generated samples exhibit “sufficient aggressiveness” is a core metric for evaluating adversarial weather scene generation. Therefore, based on the predicted collision probabilities, we first conduct a statistical analysis of the risk scores of samples generated by different models.

We constructed a dedicated risk assessment network with an output range of [0, 1], representing the intensity of collision risk induced by each weather configuration. Figure 2 illustrates the risk score distributions for the Baseline, DDPM, and RADM models under this metric.

Figure 2: Predicted risk score distributions.

Histograms of the risk distribution of weather samples generated by different models. The “Predicted Risk Score” is the risk score of each generated weather sample calculated by the trained risk assessment model, and the higher value represents the higher potential collision risk of the sample; the “Density” is the risk score of each generated weather sample within different risk score intervals. denotes the normalised probability density of the samples in different risk score intervals, the higher value indicates that the generated samples are more concentrated in this interval.The results in Fig. 2 show that the Baseline model’s risk distribution is concentrated in the [0.0, 0.3] range, with a very low proportion of high-risk samples. The DDPM model exhibits an expanded risk range due to the introduction of noise perturbations, but most samples remain in the medium-to-low risk range. In contrast, RADM demonstrates a dense concentration in the high-risk interval (0.6–1.0), with a pronounced right tail, indicating a significantly stronger capability to sample high-risk scenarios compared to the other models.

Furthermore, we group and compare the risk statistical characteristics of the samples generated by the three models from multiple perspectives. The detailed statistical comparisons are reported in Table 1.

| Indicator/Model | Baseline | DDPM | RADM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Risk mean | 0.12 | 0.26 | 0.79 |

| Risk variance | 0.045 | 0.087 | 0.065 |

| Median risk | 0.11 | 0.23 | 0.83 |

| Top10% high risk mean | 0.23 | 0.47 | 0.96 |

| P90 risk value (90% tertile) | 0.22 | 0.44 | 0.95 |

| Proportion of high-risk area (>0.6) | 2.5% | 13.6% | 85.2% |

| Proportion of ultra-high risk zone (>0.8) | 0.1% | 2.0% | 72.3% |

| Proportion of low risk zone (≤0.2) | 91.4% | 73.2% | 5.8% |

| Minimum risk value | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.08 |

| Maximum value at risk | 0.26 | 0.53 | 0.99 |

Note:

RADM significantly outperforms both Baseline and DDPM in terms of the percentage of samples in the high-risk area (>0.6), the mean of the top 10%, and the overall rightward shift of the distribution, which increases the density and upper limit of extreme risk samples.

When comparing the key metrics mentioned above, it is clear that the RADM model significantly outperforms both Baseline and DDPM across several risky statistical metrics. Firstly, the mean and median risks of the RADM-generated samples are notably higher, indicating that the overall sampling distribution is more concentrated in high-risk areas. Additionally, the proportion of samples from high-risk areas (>0.6) and ultra-high-risk areas (>0.8) reaches 85.2% and 72.3%, respectively, which is much higher than the comparative models, greatly enhancing the coverage of extreme events. Moreover, RADM’s top 10% high-risk mean and the P90 quartile points approach an upper limit close to 1.0, reflecting its elevated extremity in the right-tail distribution. In contrast, the majority of Baseline and DDPM samples are distributed in the low-risk range, making it difficult to generate effective high-risk, long-tail scenarios. Overall, the RADM model not only significantly increases the generation probability and density of high-risk weather samples but also demonstrates stronger targeted risk-sampling capabilities, providing a more challenging scenario base for the safety limit tests of autonomous driving systems.

Diversity and physical distribution coverage analysis

In the task of generating scenarios for autonomous driving tests, in addition to focusing on the ability to generate high-risk weather samples, the diversity and physical plausibility of the scenarios are also key criteria for assessing the generation model. Diverse weather distributions ensure that the autonomous driving system can expose potential weaknesses across the entire test space, preventing the model from falling into a narrow or overfitting region, thus enhancing the comprehensiveness and persuasiveness of the evaluation.

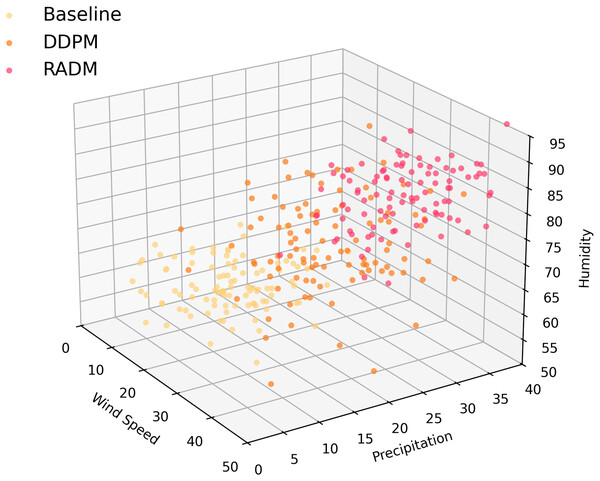

To this end, in this section, we select three key physical attributes—wind speed maximum , precipitation, and relative humidity (RHU)—and compare the coverage and distribution characteristics of the samples generated by Baseline, DDPM, and RADM using 3D point cloud distribution visualization. As shown in Fig. 3, the sample distribution of Baseline is clearly clustered in a narrow range of low wind speed, low precipitation, and high humidity, lacking the ability to sample extreme weather conditions. Although DDPM generates a broader range of diversified weather, there is still a significant gap in the region of high wind, strong precipitation, and extreme humidity. In contrast, RADM greatly enhances the spatial dispersion and coverage of physical parameters. The point clouds are widely distributed in high wind speed, high precipitation, and varied humidity regions, with a significant increase in boundary samples.

Figure 3: Weather feature space comparison.

3D point cloud distribution of weather samples generated by different models (wind speed, precipitation and humidity for example.) RADM significantly enlarges the effective coverage of the physical distribution space, and the sample diversity and extremity are better than that of the comparison model.In order to facilitate the visual comparison of the multi-dimensional indicators, Table 2 adopts the format of block grouping:

| Indicator/Model | Baseline | DDPM | RADM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average wind speed (m/s) | 13.6 | 21.4 | 35.1 |

| Median wind speed (m/s) | 12.8 | 19.7 | 32.5 |

| Maximum wind speed (m/s) | 26.7 | 39.9 | 51.8 |

| Top 10% wind speed (m/s) | 25.8 | 38.9 | 50.2 |

| Wind speed variance | 4.8 | 8.5 | 13.7 |

| Mean precipitation (mm/h) | 4.6 | 11.2 | 21.1 |

| Median precipitation (mm/h) | 4.1 | 9.7 | 18.2 |

| Maximum precipitation (mm/h) | 8.4 | 19.8 | 33.6 |

| Precipitation Top10% (mm/h) | 7.7 | 18.3 | 32.2 |

| Average humidity (%) | 85.9 | 78.8 | 71.1 |

| Median humidity (%) | 87.1 | 76.4 | 68.9 |

| Minimum humidity (%) | 55.3 | 44.1 | 33.5 |

| Humidity Variance | 5.5 | 8.7 | 12.8 |

Comparing the key physical attributes in Table 2, it is evident that the RADM model significantly outperforms both Baseline and DDPM in core metrics such as mean wind speed, maximum wind speed, maximum precipitation, and humidity coverage. The mean extreme wind speed (35.1 m/s), maximum wind speed (51.8 m/s), and extreme precipitation (33.6 mm/h) generated by RADM are at least 30% higher than those produced by the comparative models. Additionally, the high Top10% value further reflects RADM’s stronger coverage in the boundary region. Meanwhile, the humidity distribution shows a lower minimum value and the highest variance, indicating that RADM generates samples with the greatest physical diversity and extremity. These results suggest that RADM offers a broader distribution range and more challenging scenarios for testing of autonomous driving systems.

Visualization of generated weather scenarios

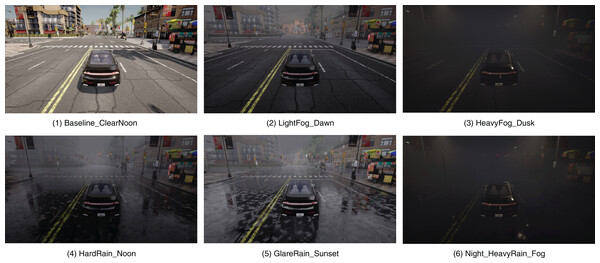

To visually analyze the realism and diversity of the weather scenarios generated by RADM, we present representative screenshots captured in SafeBench–CARLA, as shown in Fig. 4. The results illustrate a broad spectrum of environmental conditions—from clear noon and light fog at dawn to heavy fog at dusk, hard rain at noon, glare rain at sunset, and night scenes with heavy rain and fog—demonstrating the model’s ability to generate diverse yet physically consistent weather states. Each scenario is rendered directly from the weather parameters produced by RADM through the SafeBench interface. The visualization confirms that RADM produces smooth and realistic transitions across multiple meteorological dimensions such as rainfall intensity, fog density, illumination, and visibility, while maintaining coherent lighting and atmospheric effects. In particular, the heavy-rain and night-fog scenes exemplify safety-critical conditions that substantially increase collision likelihood in downstream autonomous-driving evaluations, validating the effectiveness of RADM for high-risk scenario generation.

Figure 4: CARLA weather scenario examples.

Representative screenshots of weather scenarios generated by RADM in CARLA. The scenes include clear noon, light fog at dawn, heavy fog at dusk, hard rain at noon, glare rain at sunset, and night with heavy rain and fog, demonstrating RADM’s ability to synthesize diverse and physically plausible weather conditions for safety-critical autonomous-driving evaluation.Assessment of policy migration and generalisation capability

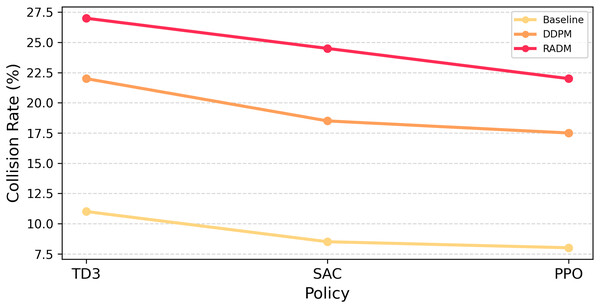

In order to systematically evaluate the generalisation ability of the proposed model under multiple autonomous driving strategies, this article examines the magnitude of collision risk enhancement of Baseline, DDPM and RADM under three mainstream reinforcement learning planners, namely TD3, SAC and PPO. The three strategies represent the typical decision characteristics of deterministic, entropy regularity and trust domain optimisation, respectively, and differ in their robustness and response mechanisms for high-risk scenarios, and thus have a direct impact on the ability of each type of generative model to induce collisions.

The experimental results are shown in Fig. 5. It can be observed that the samples generated by Baseline have limited collision enhancement for all kinds of strategies and weak generalisation ability; DDPM, as unguided diffusion generation, has some breakthroughs but it is difficult to obtain simultaneous enhancement among multiple strategies. In contrast, RADM significantly improves the level of collision rate under all three mainstream strategies, and the distribution of risk enhancement is balanced, indicating that its generation scenario is more universally offensive to different agent-policy. This advantage suggests that RADM can not only provide a worst-case test for a single autonomous driving algorithm, but also be used for multi-model cross-evaluation, which lays the foundation for diverse robustness tests of autonomous driving scenarios.

Figure 5: Collision rates under generated scenarios.

Comparison of collision rate enhancement of the three types of models under different strategies. RADM shows high level and balanced risk-inducing ability under TD3, SAC, and PPO.Comparing the key physical attributes in Table 3, it can be seen that the RADM model significantly outperforms Baseline and DDPM in core metrics such as mean wind speed, maximum wind speed, maximum precipitation, and humidity coverage, etc. The RADM-generated mean extreme wind speed (35.1 m/s), maximum wind speed (51.8 m/s), and extreme precipitation (33.6 mm/h) are at least 30% or more higher than the comparative models. 30% or more, and the high Top10% value also reflects its stronger coverage in the boundary region. Meanwhile, the humidity distribution has a lower minimum value and the largest variance, proving that RADM generates the most physically diverse and extreme samples. This result suggests that RADM is able to bring a greater distribution range and challenge for robustness testing of automated driving systems.

| Strategy | Model | Collision rate (%) |

Failure rate (%) |

Average speed (km/h) |

Average lane departure (m) |

Lane completion rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TD3 | Baseline | 11.8 | 4.7 | 23.6 | 0.22 | 95.1 |

| DDPM | 21.7 | 7.9 | 21.1 | 0.30 | 90.2 | |

| RADM | 29.5 | 13.2 | 19.3 | 0.27 | 91.0 | |

| SAC | Baseline | 8.5 | 4.3 | 23.8 | 0.23 | 95.4 |

| DDPM | 17.4 | 8.4 | 21.7 | 0.32 | 90.1 | |

| RADM | 26.3 | 13.0 | 19.2 | 0.29 | 91.2 | |

| PPO | Baseline | 8.2 | 4.1 | 24.0 | 0.25 | 95.8 |

| DDPM | 16.8 | 8.6 | 21.3 | 0.33 | 89.8 | |

| RADM | 24.7 | 13.4 | 19.0 | 0.30 | 91.1 |

Test effectiveness analysis

Test effectiveness is a critical criterion for evaluating the practical value of adversarial scenario generation. In the context of extreme weather sample generation, it is not sufficient to simply increase test difficulty or collision risk. It is equally essential to demonstrate that the generated scenarios can expose system weaknesses while maintaining stable and valid evaluation. To this end, this section systematically assesses the test effectiveness of RADM and baseline models, considering metrics such as path completion rate, incompletion rate, average speed, and lane departure. This approach ensures that improvements in risk exposure are accompanied by scenarios that remain physically feasible and operationally accessible, thereby supporting credible and meaningful testing outcomes.

The experimental results are presented in Table 4. RADM ensures the successful completion of most test tasks while significantly improving the collision rate and sample diversity. The small differences in path completion rates across the three models suggest that, even in high-risk weather scenarios, the autonomous driving system can still handle the generated scenarios effectively without frequently leading to simulation anomalies or “cheating” phenomena. Meanwhile, changes in lane departure and other indicators remain within a reasonable range, indicating that while the extreme samples increase the challenge for agent control, the overall driving behavior still maintains physical feasibility and system stability.

| Model | Route completion rate (%) |

Failure rate (%) |

Average speed (km/h) |

Mean lane deviation (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 95.3 | 4.7 | 23.4 | 0.24 |

| DDPM | 89.7 | 8.9 | 21.4 | 0.31 |

| RADM | 91.5 | 13.8 | 19.6 | 0.28 |

Further, Table 5 presents a comparison of the performance of the strategies from different models under both standard and extreme storm scenarios. It is evident that RADM generates higher collision rates and lower average speeds under extreme weather, indicating that it increases the test stress while maintaining the underlying rationality and usability of the scenario. The similar performance of the models under standard scenarios further supports the ability of the generated models to balance challenging conditions with realistic constraints.

| Scenario | Metrics/Models | Baseline | DDPM | RADM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard scenarios | Completion rate (%) | 96.2 | 91.4 | 93.1 |

| Crash rate (%) | 7.2 | 15.9 | 19.4 | |

| Average speed (km/h) | 23.8 | 22.0 | 21.2 | |

| Extreme storm field | Completion rate (%) | 91.8 | 82.3 | 84.2 |

| Collision rate (%) | 13.7 | 28.4 | 36.8 | |

| Average speed (km/h) | 19.2 | 16.3 | 13.8 |

RADM effectively ensures the test effectiveness of the generated scenarios while enhancing their high risk and diversity. Consequently, it can provide robust and reliable extreme weather samples for large-scale autonomous driving simulation tests.

Discussion

The experimental results validate the effectiveness of incorporating risk perception information into diffusion models, demonstrating a significant improvement in the generation of high-risk extreme weather test samples. By directly integrating risk metrics into the diffusion process (Benrabah et al., 2024), the method enhances the high-risk nature of the generated samples while maintaining their diversity and physical plausibility. When compared to existing baseline methods, RADM demonstrates its potential for application in the safety assessment of autonomous driving systems by expanding sample distribution coverage and improving collision risk.

However, the study also has some limitations. First, RADM’s reliance on large amounts of historical data, particularly in terms of meteorological data collection, limits its widespread applicability in low-resource environments (Agbeyangi & Suleman, 2024). For example, training based on historical weather data may not adapt to the generation requirements in extreme weather conditions. Future research can explore how to reduce dependence on large-scale datasets through transfer learning or few-shot learning (Song et al., 2023), while improving the flexibility of the model to adapt to testing requirements under different weather conditions. Additionally, the RADM training process relies on traditional simulation platforms such as SafeBench, which may fail to adequately capture the real-world impact of extreme climate changes on autonomous driving systems in certain scenarios (Ma et al., 2023). Therefore, future research could further integrate more complex physical simulations to enhance the realism and challenge of generated weather scenarios.

Second, although RADM employs an effective risk feedback mechanism to guide the generation process, the current model primarily relies on risk scores based on simulation results, which may introduce certain biases. In real-world deployment environments, the model may fail to fully reflect the complex factors present in actual traffic conditions, such as regional climate differences or sudden natural disasters (Martínez-Zarzoso, Nowak-Lehmann & Paschoaleto, 2023). Future research could further enhance the model’s generalization capabilities by integrating it with more external environmental data, enabling it to better adapt to complex and uncertain real-world testing scenarios. Additionally, as deep reinforcement learning and self-supervised learning methods continue to evolve (Rani et al., 2023), exploring how to integrate these technologies with RADM to improve the model’s performance in unknown or unseen high-risk scenarios is a direction worthy of further investigation.

Third, RADM may face computational overhead issues when handling large-scale experiments and generating diverse extreme weather scenarios, particularly during the sampling process in high-dimensional meteorological parameter spaces (Peterson et al., 2021). Although the model gradually approaches high-risk areas through multi-round feedback optimization (Ren et al., 2025), the computational cost remains high. Future research could explore more efficient generation strategies, such as using dimensionality reduction techniques or fast training strategies to accelerate model convergence, thereby reducing computational overhead while maintaining generation quality.

Conclusions

The RADM proposed in this study offers an efficient and practical approach for automatically generating extreme weather test samples for autonomous driving simulation tests. Experimental results show that RADM not only effectively increases the risk exposure level of the generated samples but also maintains diversity and physical controllability, outperforming the existing baseline and traditional dispersion models. Specifically, the risk feedback sampling mechanism enables the model to actively target high-risk areas, significantly improving the coverage of safety boundaries in autonomous driving testing. Compared with existing models that mainly rely on static scenarios and model control strategies, RADM better captures dynamic changes and extreme situations in real traffic environments, thus providing more challenging and representative test samples for safety and robustness validation. Additionally, the RADM framework is implemented using PyTorch, a mainstream deep learning platform, with a well-defined overall process. The related modules are flexible to integrate into existing simulation and testing platforms, offering better scalability and ease of use. This provides a pathway for the future deployment and safety testing of large-scale autonomous driving systems.

Supplemental Information

Code and data-processing scripts for RADM-based high-risk weather generation and SafeBench evaluation.

The full reproducibility code for this study. It includes scripts for baseline/DDPM weather generation, risk-weighted training data construction from SafeBench feedback, RADM training and high-risk weather sampling, multi-round RADM–SafeBench loops, multi-policy evaluation (TD3/SAC/PPO), and feedback summarization. Files are open, machine-readable formats (Python, YAML, CSV/NPZ/PKL) and were tested with Python 3.8 (NumPy, Pandas, PyTorch, scikit-learn, PyYAML). SafeBench/CARLA is required only for the evaluation stage.