Effects of parameters of particle swarm optimization algorithms on the path planning for flexible needles

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Paulo Jorge Coelho

- Subject Areas

- Algorithms and Analysis of Algorithms, Artificial Intelligence, Optimization Theory and Computation, Robotics

- Keywords

- Flexible needle, Particle swarm optimization, Path planning, Parameter optimization

- Copyright

- © 2026 Zhang et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2026. Effects of parameters of particle swarm optimization algorithms on the path planning for flexible needles. PeerJ Computer Science 12:e3569 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3569

Abstract

Background

Percutaneous puncture has wide applications in various clinical tasks. Path planning is crucial but challenging. Particle swarm optimization (PSO) algorithms are proper candidates to solve this problem and have been introduced. However, path planning errors exist and the effects of PSO parameters have not yet been studied.

Methods

A kinematic model was developed using the D-H method. The best combination of PSO parameters for flexible needle-path planning was obtained by the genetic algorithm with the Lord strategy. According to simulation results, an iterative PSO is proposed.

Results

Simulations demonstrate that the deviation was reduced to 0.017 mm on average (mostly close to zero) with optimized parameters. An accuracy of 0.001 mm can be guaranteed by proposed iterative PSO.

Conclusions

The optimized parameters can significantly reduce the path deviation, and provide an optimal path with a simple PSO. The proposed iterative PSO can attain superior performance while consuming less computation time.

Introduction

Minimally invasive surgery has advantages such as minimal trauma, low risk of infection, and improved postoperative recovery, making it inevitable in clinical diagnosis and treatment (Burgner-Kahrs, Rucker & Choset, 2015; Lu et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2020). As an important component of minimally invasive surgery, percutaneous needle insertion has been widely used to perform various clinical tasks including brachytherapy (Padasdao & Konh, 2021), radiofrequency ablation (Zhang et al., 2019), drug delivery (Khadem et al., 2018), and biopsy (Martsopoulos et al., 2023). The therapeutic effect of the above procedures is highly dependent on the precise placement of the needle tip in the target region, avoiding anatomical barriers. Incorrect needle placement can lead to serious complications such as invalid negatives in biopsy or severe damage to healthy tissue in radiofrequency ablation (Martsopoulos et al., 2023; Okamura, Simone & O’Leary, 2004). However, the commonly used needles are rigid and straight, have high stiffness, and lack controllability (Wu et al., 2022). They can only move and orient along a straight line, without the capacity to avoid obstacles such as vessels, bones, and major organs (Huang, Yu & Zhang, 2024). Moreover, it cannot correct the deviation between the needle tip and the target caused by factors such as needle-tissue interaction and organ deformation (Huang & Zhang, 2024). Once a deviation occurs, the general treatment method for surgeons is to manually readjust the needle tail or remove the needle and reinsert it into the tissue, which increases patient suffering and the risk of potential complications (Huang, Yu & Zhang, 2024).

Flexible needles are an alternative to rigid straight needles owing to their high maneuverability. A flexible needle is usually made of materials with low stiffness, such as nitinol alloys. Owing to the low stiffness and asymmetric bevel tip, the reaction force generated by needle-tissue interactions is perpendicular to the inclined tip surface, leading to the deflection of the needle tip and bending of the needle body (Huang & Zhang, 2024). Therefore, the trajectory of the flexible needle is curvilinear, unlike that of the rigid needle. Experiments have demonstrated that the single-segment path of a flexible needle is approximately equivalent to an arc (Webster et al., 2006). Moreover, the axial rotation of the needle can change the orientation of the bevel tip, thus, altering the bending direction. In other words, the trajectory of the flexible needle is a suture of multiple arcs. This improves the steerability of flexible needles and allows them to puncture designated targets deep within the human body while avoiding obstacles (Duindam et al., 2010).

To fully exploit the ability to reach targets behind impenetrable tissues or organs, path planning from the entry point to the target nidus is essential, but crucial for targeting the lesion without collision. However, as abovementioned, a flexible needle follows arc trajectory with constant curvature during puncture into a homogeneous material, limiting the puncture flexibility. To solve this problem, the duty-cycling strategy can be used to realize the curvature variability. With the duty-cycling strategy, the trajectory of flexible needle can be arc, spiral or line. Thus, the trajectory forms of flexible needle are limited. As path planning is the base of needle steering, path planning for flexible needles has been extensively studied, and several algorithms have been proposed. Most of them are based on kinematic models, such as the unicycle or bicycle model (Park et al., 2010; Zhao et al., 2019) because the kinematic model parameters can be obtained directly from experiments. Among path-planning algorithms, those based on rapidly exploring random trees (RRT) have attracted much attention. Xu et al. (2008) used the RRT to solve the path-planning problem for flexible needles in a three-dimensional environment with barriers and optimized the entry point using a backchaining strategy. Patil & Alterovitz (2010) improved the RRT sampling strategy with a goal bias and reachability-guided sampling heuristic, significantly improving the computational efficiency. Fauser, Sakas & Mukhopadhyay (2018) applied an RRT-Connect algorithm to plan access paths in temporal bone surgery and achieved higher efficiency than one-directional RRTs. However, the abovementioned studies did not solve the problem that the path planned by RRT-based algorithms is not optimal and sometimes even suboptimal (Huang, Yu & Zhang, 2024; Zhang et al., 2021). To obtain the optimal path, Zhang et al. (2021) improved the RRT* algorithm by considering an artificial potential field around obstacles. However, the RRT* algorithm is asymptotically optimal, making it impossible to obtain an optimal path within a reasonable time (Huang, Yu & Zhang, 2024). In our previous research, the improved Bi-RRT are used for two-dimension variable curvature path planning. However, it needs to expand to three-dimension environment (Huang & Zhang, 2024). Particle swarm optimization (PSO) is a suitable candidate for planning an optimal path within a reasonable time as it is simple and wide applicated, which has been introduced by previous research (Cai et al., 2020; Huo et al., 2018; Tan et al., 2022a, 2022b). Huo et al. (2018) transformed the path-planning problem for flexible needles into a multi-objective optimization problem and used PSO with dynamic weighting to determine the optimal path. Cai et al. (2020) used a simplified PSO algorithm for the path planning process. However, there were still discrepancies between the planned path and the target. According to literature, the planned path error is 1.38 mm (Cai et al., 2020). Considering the complex interactions between needle and tissue, the puncture error may be even larger. To improve path planning accuracy, Tan et al. (2022a) proposed a path planning algorithm based on PSO with a parameter adjustment mechanism and another based on PSO with bee-foraging learning and a needle retraction strategy (Tan et al., 2022b). Higher planning precision can be achieved at the cost of increased complexity and time consumption. However, there are still some further improvements in precision needed. Moreover, during puncture, path replanning is necessary because of path deviation caused by tissue deformation, which requires fast computation. In order to improve planning accuracy without increasing complexity and computation time, we investigate the effects of PSO parameters on flexible-needle path planning, which can significantly affect the results but have not yet been studied. Thus, higher path-planning accuracy can be achieved with the simplest PSO.

In this study, a kinematic model inspired by the D-H method is proposed. Subsequently, the effects of PSO parameters are studied by simulations under certain conditions, and a genetic algorithm (GA) is applied with the Lord strategy to determine the optimal combination of parameters. Based on these results, an iterative PSO (IPSO) method is proposed. Simulations and experiments are conducted to verify the planning accuracy of PSO with optimized parameters and IPSO. The main contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

(1) A kinematic model inspired by the D-H method is proposed, which is the base of path planning for flexible needle.

(2) The effects of PSO parameters on flexible-needle path planning are analyzed and the best combination of parameters are obtained by GA.

(3) We propose an iterative PSO method, which can ensure the path planning accuracy with fast computation.

The reminder of this article is organized as follows. ‘Materials and Methods’ introduces related methods such as the kinematic model and path planning based on PSO. The results and discussions are shown in ‘Results’. ‘Conclusions’ presents conclusions and possible future work.

Materials and Methods

Kinematic model

The kinematic model is the basis for path planning of flexible needles. Ideally, the trajectory of a flexible needle can be viewed as an arc with constant curvature, and the bending direction is determined by the orientation of the needle tip. An axial rotation of the needle can reorientate its tip. Thus, the movement of the flexible needle consists of a feed motion that performs the puncture and rotation motions changing the bending direction. That is, the control inputs for the flexible needle are insertion and rotation velocities (denoted by and , respectively). Assuming that the motion of the needle tip determines that of the needle body and that rotations of the needle base are fully transmitted to the needle tip, the kinematic model can be described as follows

(1) where Q represents the position and posture state of the needle tip in the world coordinate system and T(Q) is the transformation matrix between the control inputs and the needle tip states. These details can be found in Duindam et al. (2010), and Huo et al. (2018). As the radius of the needle trajectory is approximately independent of the insertion velocity (Webster, Memisevic & Okamura, 2005), and the motion of the needle base is perfectly transmitted to the needle tip (the above assumption), the insertion length of the needle (described as ) and rotation angle of the needle tip (represented as ) can be used as the control inputs. Thus, the model can be discretized and rewritten as

(2) where and are the rotation angle and insertion length from the state to , respectively. Based on the above analysis, a stop-and-rotate strategy (Wang et al., 2014) was chosen. For the ith arc, the operation involves axial rotation of the needle tip with angle at the starting point and subsequent penetration over length to reach the end point . Assuming that the initial puncture direction is perpendicular to the soft tissue, the intended path can be represented by the control sequence .

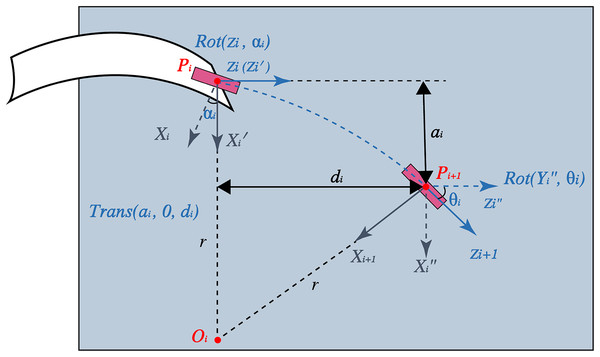

To transform the control sequence into a planned path, inspired by the D-H method, arbitrary points on the planned path can be obtained by transforming the matrices (Wei & Jiang, 2021; Zhang et al., 2020). Figure 1 shows a schematic representation of this transformation. For the arc, the coordinate is attached to the needle tip following the right-hand rule. The -axis points in the bending direction, and the -axis is along the insertion direction perpendicular to the -axis. The first operation to transform is to rotate the coordinate around the -axis with angle. and denotes this rotation operation and the obtained coordinate, respectively. Next, move along the -axis with length and along the -axis with length . The values of and can be easily calculated using geometry. After this translation operation denoted by , the coordinate becomes . Finally, rotate around the -axis by . Here, represents the center angle of the arc, which is obtained by dividing the radius r into arc length . This rotation operation is represented as . Thus, the transformation matrix from to can be expressed as

(3)

Figure 1: Schematic representation of the kinematic model inspired by the D-H method.

Assuming that the world coordinates coincide with those of the needle tip at the entry point, the position and pose of the needle tip after penetrating the arc, represented as , is described as follows:

(4)

The states of the arbitrary points in the arc can be calculated by replacing in Eq. (4) with the corresponding puncture length. Thus, a 3D kinematic model was created.

Path planning based on PSO

The basic idea of PSO is to obtain the optimal solution for a designed objective function by moving multiple particles (Cai et al., 2020). The key for path planning based on PSO is the design of particle. As the puncture length and rotation angle can be used for calculating the trajectory, the form of particle is . These particles are updated according to Eqs. (5) to (6).

(5)

(6) where and represent the velocity and position of ith particle in gth generation, respectively. , and are inertial weight coefficient and learning factors, respectively. They are the parameters needed to be optimized. and denote the best particles of ith particle and global, respectively. They are chosen according to the objective function. The objective function is determined considering the target deviation, path length, and obstacle avoidance. The path deviation is expressed as follows:

(7) where and represent the endpoints of the given path and target, respectively. The path length is expressed as follows:

(8)

During puncture, obstacle avoidance is pivotal because damage to sensitive tissues such as vessels and nerves can lead to severe complications. The path danger level is expressed as follows:

(9) where is the minimum distance between the path and barrier. DS is the safe distance between planned path and obstacles. The above factors are weighted differently ( ), which are set to be 0.8, 0.1 and 0.1, respectively because we think that puncture accuracy is more important. Thus, the objective function is expressed as follows:

(10)

Optimization by GA

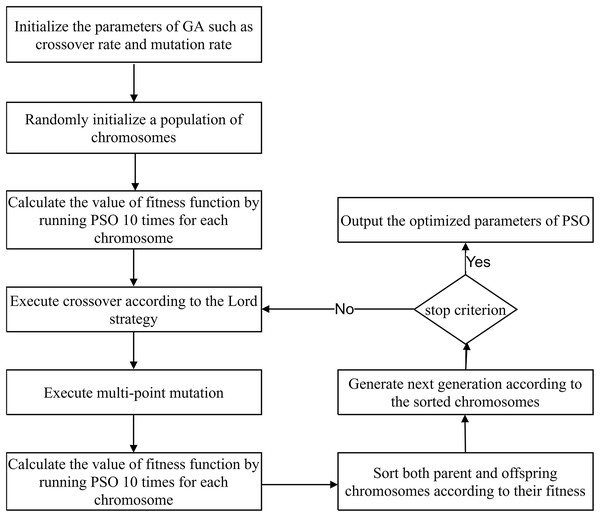

The PSO parameters significantly influence the effects of path planning for flexible needles. As the GA is one of the most popular optimization algorithms with simple structure, it has been widely used in various applications. Thus, it is applied to obtain the best combination of parameters. GA evolutionarily determines the best individual using operators inspired by natural selection and biological processes. These operators include selection, crossover, and mutation. The form of GA chromosomes is designed as . Because the effects of the PSO parameters on path planning for flexible needles were studied through simulations based on the variable control method, a primary candidate combination of parameters was obtained. Thus, the primary combination was used as the best chromosome for the first generation, and the Lord strategy (Zhang et al., 2020) was applied instead of the roulette wheel selection, facilitating the convergence speed. When the Lord strategy is adopted, chromosomes are sorted according to the values of the fitness function, and the best one is selected as the Lord to perform a crossover with the chromosomes in even order. In our opinion, generally, the primary candidate combination obtained above performs much better than randomly generated chromosomes. Thus, selecting this solution rather than randomly generated one as the Lord helps to rapidly generate better chromosomes and facilitate the convergence speed. The crossover rate (CR) is empirically set to be 0.8. Note that the fitness is the average path deviation acquired by running the PSO 10 times with each specified combination of parameters. Subsequently, a multi-point mutation with mutation rate (MR) 0.1 was performed for each offspring. After the mutation, the parents and offspring are sorted and the number of population (NP) chromosomes are selected as the population of the next generation. Here, NP is 30. Note that NP here is the population size of GA. According to our experience, NP can be set to be 40 (Zhang et al., 2020). However, the computation time increases with the increasing of NP. Especially for optimizing the parameters of PSO, the PSO will be conducted about times. T is the iteration times of GA. Thus, the computation time increases greatly with the increases of NP. To decrease the computation time, NP is set to be 30. This process was repeated 500 times (i.e., T is 500). These parameters are shown in Table 1. The optimization process is shown in Fig. 2.

| Algorithms | Parameters | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optimized PSO | |||||

| GA | / | ||||

| I-PSO | |||||

Figure 2: The workflow of PSO optimization by GA.

Iterative PSO

As shown in ‘Optimization by GA’, even with the optimized combination of parameters, large deviations may occur between the path planned by PSO and the target. This may be caused by PSO falling into local minimum. To guarantee path planning accuracy, we propose the iterative PSO (I-PSO). The main idea of I-PSO is to iteratively running PSO until the path deviation within a specific accuracy (e.g., 0.001 mm). To reduce the computation time, parameters such as the number of particle swarms and iteration times are set according to the effects of PSO parameters. More details are shown in ‘Iterative PSO’.

Puncture platform

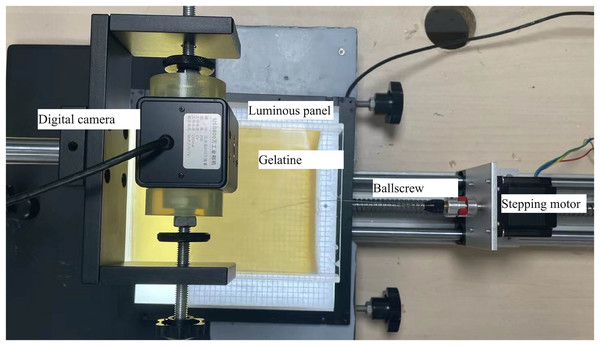

The established experimental puncture platform is shown in Fig. 3. A control system, two rotational stepping motors, and a digital camera are its primary components. The control system controls the stepping motors to perform the feeding and rotation movements. A digital camera with the resolution 2,592 × 1,944 was used to capture images during the puncture process to obtain the radius and trajectory of the needle insertion into the gelatin prostheses. The nitinol needle was customized using wire-electrode cutting. During the puncture verifying experiments, we first horizontally punctured the 18% gelatin using the flexible needle with 15° needle tip angle and 0.8 mm diameter at the speed of 15 mm/s for three times. Then, the puncture radius was calculated by image processing such as grey processing, denoising, sharpening and binarization. The puncture radius was used for path planning and the planned path would be punctured.

Figure 3: Puncture platform.

Data preprocessing is not involved in this experiment.

Results

Effects of PSO parameters

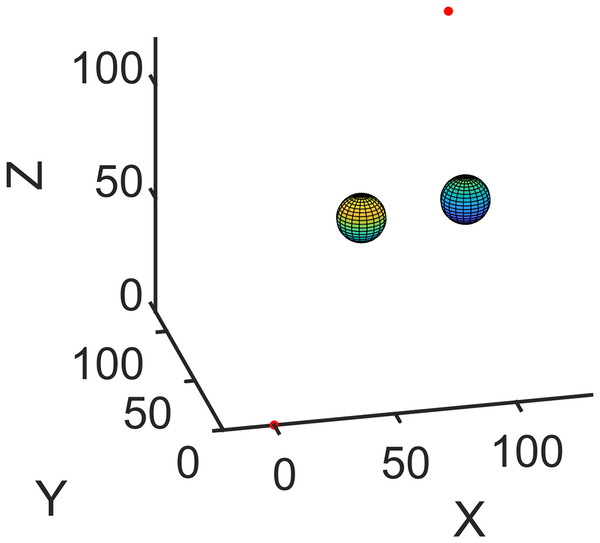

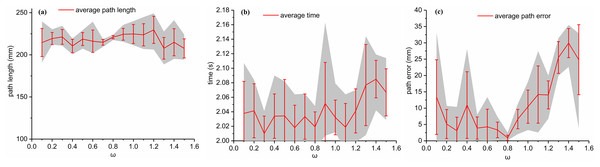

First, the simulation environment was created (Scenario I, Fig. 4). The coordinates of the entry and target points were (0, 0, 0) and (100, 120, 120), respectively. The initial insertion direction was perpendicular to the x-y plane, and the radius was assumed to be 40 mm. The centers of the obstacles were (50, 60, 60) and (100, 90, 50) with a radius of 10 mm. A variable control method was then applied. As the learning factors, denoted by , were set to 1 and 2 in Cai et al. (2020), Huo et al. (2018), Zhang et al. (2021), these values are adopted as the initial values of the PSO parameters to study the effects of inertial weight coefficient . The population size was 50, and the number of iterations was 1,000. For each parameter combination, PSO was run five times and the average value will be chosen as the running results (shown in Fig. 5). Then simulations were done in MATLAB R2020a (The MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA) with AMD Ryzen 7 6800H and 16 G memory. The results show that has tiny effects on the computation time and small effects on the path length. However, when the value of changes from 0.1 to 1.5, the average path error varies from 0.9145 to 29.9272 mm, which significantly affects the puncture accuracy. For this condition, the best value for is 0.8.

Figure 4: Simulation environment (Scenario I). The entry and target points are shown in red dots. The obstacles are spherical.

Figure 5: For Scenario I, the relationship between path length, average time and path error and ω with c1 = 1 ,c2 = 2 are shown in (A), (B) and (C), respectively.

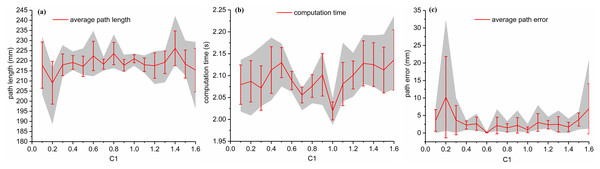

Then, set the value of and to 0.8 and 2, respectively, and varies from 0.1 to 1.6 with an interval of 0.1. The results are shown in Fig. 6. From this, it can be seen that when increases, the average computation time is in the range of [2.0194, 2.1358], indicating that has little influence on the computation time. So as to effects of on the path length. However, for , the average path error varied from 0.1585 to 10.2135 mm. The best value obtained under these conditions was 0.6.

Figure 6: For Scenario I, the relationship between path length, computation time and path error and c1 with ω = 0.8 , c2 = 2 are shown in (A), (B) and (C), respectively.

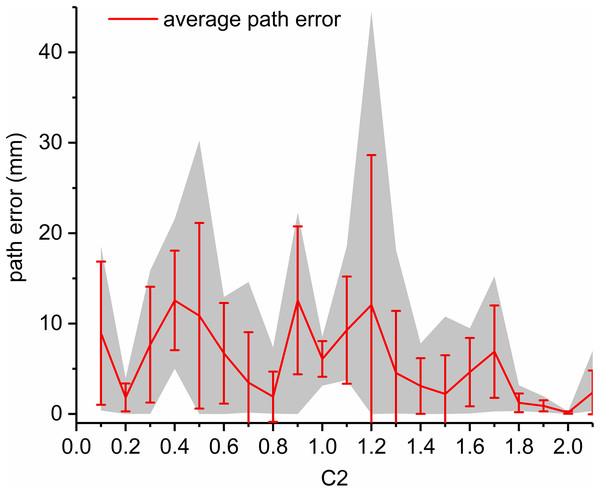

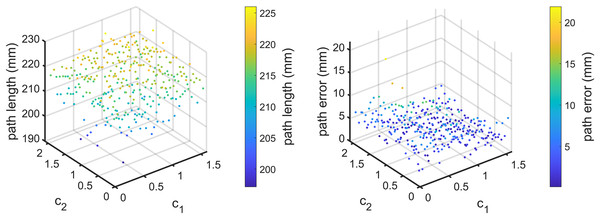

Finally, under the condition , the effects of is studied by simulations. The results are shown in Fig. 7. When changes in [0.1, 2.1], the average path error varies from 0.1585 to 12.5709 mm. The best value for in this scenario is 2. The above simulations demonstrate that , and have little effect on the computation time of path planning for the flexible needle based on PSO and the path length, but significantly affect the path error, which is critical for needle insertion. To better show the effects of parameters, we take the effects of and when as an example. The results are shown in Fig. 8.

Figure 7: For Scenario I, the relationship between path error and c2 with ω = 0.8 , c1 = 0.6.

Figure 8: For Scenario I with ω = 0.8 , the path length (left) and path error (right) vary with c1 and c2, respectively.

Optimization by GA

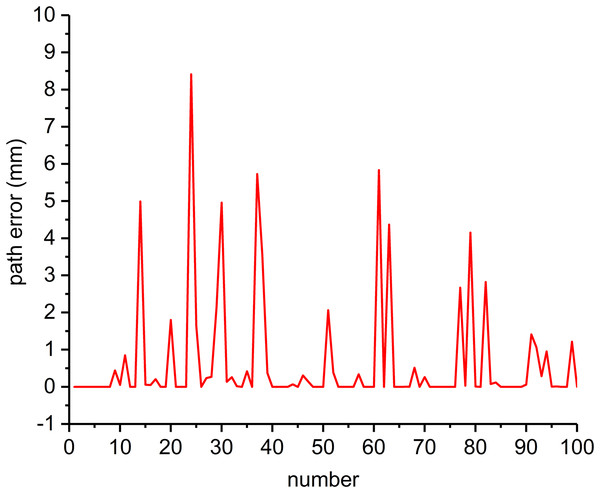

‘Effects of PSO parameters’ reveals a primary better combination of parameters of the form is [0.8, 0.6, 2]. This combination was used as the best-fit chromosome for the first-generation population of GA. After optimization, the best parameters were as . To illustrate the effectiveness of the optimized parameters, PSO was performed 100 times with these parameters. The results are shown in Fig. 9.

Figure 9: Path errors with optimized parameters (NP = 50, T = 1,000). The x-axis shows the counter number of repetitions.

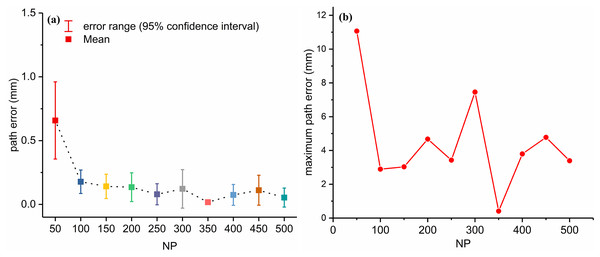

With the optimized , the path errors are in the range of [0, 11.0664]. More than half of the path errors are smaller than 0.1 mm (most are close to zero), but 35 path errors are still larger than 0.1 mm. This may be caused by the PSO falling into local minima. To overcome this problem, the effects of NP were studied by running PSO 100 times for each NP (Fig.10). Figure 10A show that with an increase of NP, the path error decreases rapidly at first and does not improve significantly when NP becomes larger than 100. Figure 10B shows the maximum path errors for different NP values. The NP value with the minimum average path error was 350. For NP = 350, the path error varied from 0 to 0.4886 mm, with an average of 0.0124 mm. This verifies the effectiveness of the parameter optimization. However, the computation time was approximately 12.6 s, which was unfavorable for intraoperative path replanning. Again, the simulation was based on MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA) with a Ryzen 7 6800H and 16G memory.

Figure 10: Path error (A) and maximum path error (B) with different NP with optimized combination of ω, c1, c2.

Iterative PSO

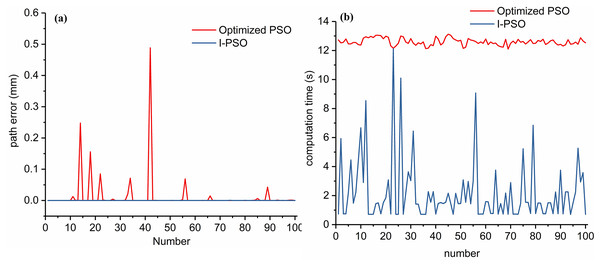

To achieve better performance with less computation time, I-PSO was proposed based on the above results. The main idea is to execute the PSO iteratively until the desired accuracy is achieved. As described above, even with optimized parameters, PSO can plan a path with errors near zero even for a small population size. Because the computation time increases linearly with NP, a small NP helps reduce computation time. Thus, for I-PSO, NP was 50, T was 400, and the termination accuracy was 0.001 mm. One hundred times of simulations show that the path errors of the I-PSO are within [0, 0.00073] mm and 0.000046 mm on average, which significantly increases the planning accuracy compared to the optimized PSO with an average of 0.0124 mm. Moreover, the average computation time was 2.19 s, which was much shorter than that of the optimized PSO (12.6 s). The details are shown in Fig. 11.

Figure 11: Path error (A) and computation time (B) of the optimized PSO and I-PSO for Scenario I. The x-axis shows the counter number of repetitions.

Verifying experiments

To verify the performance of the PSO with the optimized parameters and the I-PSO, 100 times of simulation for each algorithm are executed and simulation results with Scenario I are compared with the existing simplified PSO (Cai et al., 2020) and adaptive intelligent PSO (AIPSO) (Tan et al., 2022a). For PSO, , and are set to be 0.8, 1 and 2, respectively. For AIPSO, the parameters are the same with the reference, that is, , , , , (Tan et al., 2022a). The results are shown in Table 2. From Table 2, we can summarize that the paths planned by optimized PSO are with least path length and smaller path error at the cost of increasing computation time. Paths planned by proposed I-PSO are with highest accuracy and the average computation time is acceptable. However, the path length is slightly increased. These results suggest that the proposed optimized PSO and I-PSO can significantly increase the path planning accuracy and compared to optimized PSO, I-PSO can greatly reduce the computation time (the average computation time of I-PSO is about 17% of that of optimized PSO).

To further verify the effectiveness of proposed algorithms, puncture experiments are carried out. Limited by the length of flexible needle and the depth of phantom carriage, we use the other scenario (Scenario II) for puncture. First, we establish the simulation environment and plan the path. Then, we execute the puncture experiment with the established puncture platform. The simulation environment of Cai et al. (2020) was used (Zhao et al., 2022). The target is located in (−5, 0, 120) and obstacle is located in (0, 0, 70) with a radius of 2 mm. The puncture radius was 407.24 mm, which was determined by a puncture experiment and image processing. The number of arcs is three. Because each time the path planned by PSO may be different, each algorithm is running only once for puncture experiment. According to literature, the path error of PSO for this scenario is 1.38 mm (Cai et al., 2020). To make the results in consistent with literature, , and are set to be 1, 1 and 2, respectively. The simulation results show that, the optimized PSO can significantly improve the planning precision at the cost of computation time compared to PSO (Cai et al., 2020), and that I-PSO can achieve a sufficiently high precision with reduced time. The errors in the paths planned by both the optimized PSO and I-PSO are negligible. The path details are listed in Table 3.

| Arc length (mm) | Rotation angle (rad) | Error (mm) | Time (s) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSO1 | 44.0367 | 51.6781 | 23.8710 | 2.8251 | 2.8501 | 2.8399 | 0.7277 | 1.527 |

| AIPSO2 | 33.4830 | 74.4903 | 12.2368 | 4.4412 | 3.7301 | 4.2796 | 0.4111 | 2.696 |

| Optimized PSO | 47.0367 | 60.8764 | 12.3182 | 2.9178 | 2.9373 | 1.6147 | 9.867 | |

| I-PSO3 | 23.1567 | 27.2219 | 69.8496 | 3.1280 | 1.2522 | 2.9509 | 0.461 | |

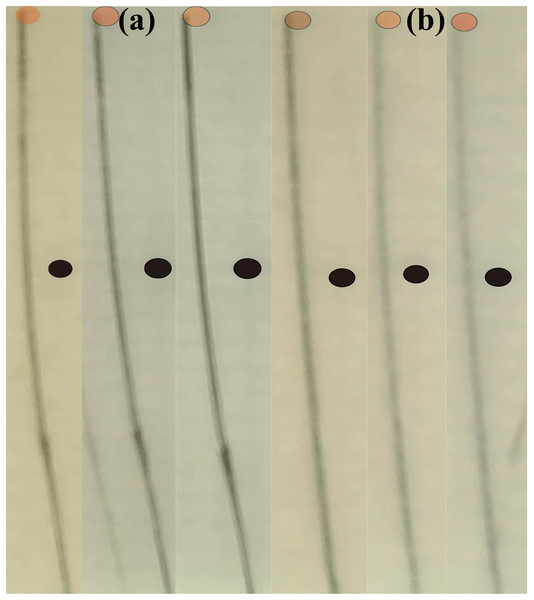

The puncture experiments are shown in Fig. 12. During experiments, nitinol flexible needle with 0.8 mm diameter and 15 degrees needle tip is used to puncture the phantom with 18% gelatin at the speed of 15 mm/s. Due to the low permeability of gelatin, the target point and obstacle point in the experimental result diagram are not clear. Therefore, we mark the obstacle point and the target point, but do not modify the position of the target point and the obstacle point. At the same time, in order to better judge the position of the tip, the transparency of the target point mark is set to 40%. For the path planned by the optimized PSO, the coordinates of the needle tip for three times puncture are (−5.24, 0, 121.69), (−6.94, 0, 121.71) and (−7.97, 0, 120.11), which is 1.7070, 2.5861 and 2.9720 mm away from the ideal coordinates, respectively. Note that the coordinates are measured in the x-z plane; therefore, the y coordinate is set to 0, so that the error in the y-direction is neglected. For the path planned by I-PSO, the coordinate is (−5.96, 0, 121.09), (−6.21, 0, 120.6) and (−5.96, 0, 120.48), which is 1.4525, 1.3506 and 1.0733 mm off the ideal path, respectively. From Table 3 and puncture experiments, we can summarize that with the decreasing of path planning error, the puncture accuracy will be improved. The actual coordinates of the needle tip deviated from those of the simulations due to factors such as the simplification of the needle trajectory to an arc, out of sync between rotation angles of the needle base and tip and the accuracy of our puncture platform. The results also demonstrate that even with slight path planning error, the actual puncture error is much larger. The error of optimized PSO and I-PSO were within the acceptable range (4 mm according to Cai et al. (2020)).

Figure 12: The puncture trajectories according to the path planned by PSO (A, left 3) and I-PSO (B, right 3).

Discussions

In order to increasing the path planning accuracy within a reasonable time, we investigate the effects of PSO parameters on path planning for flexible needles. According to simulation results, we find that , an have slightly effects on computation time of PSO. However, their combination can greatly affect the error of planned path. We use GA to obtain the best combination of these parameters. Note that the parameters of GA are empirically selected according to our previous work. As the optimization process takes long time, the selection of GA parameters and the acceleration of simulations will be our future work. Here, we focus on the effects of PSO parameters. Simulation results suggest that with the best parameters combination, the path error could be greatly reduced and the path planning accuracy can be improved. We guess that this is caused by PSO falling into local minimum. To further improve path planning accuracy, we investigate the effects of population size on path planning. Simulation results suggest that with the increasing of population size, the path planning accuracy can be improved. When the population size is bigger than 200, the improve of accuracy is slightly. However, the computation time will be linearly increased, which is not suitable for intraoperative path planning. In order to guarantee path planning accuracy within a reasonable time, we propose an iterative PSO algorithm based on the effects of PSO parameters. Simulations suggest that compared to PSO (Zhao et al., 2022) and AIPSO (Huo et al., 2018), the proposed I-PSO can not only significantly improve the planning accuracy, but also greatly reduce the computation time. With 0.01 mm termination accuracy, the planned path error can be greatly reduced from 0.0124 mm (Optimized PSO) to 0.000046 mm. That is, the path error can be reduced to 0.4%. Note that, this tiny error is obtained from simulations. In reality, factors such as motor resolution, friction and tissue heterogeneity make the submillimeter precision impossible in real systems. This accuracy is just used to illustrate the effectiveness of the optimized PSO and I-PSO. The average computation time of I-PSO is 17% of that of optimized PSO. From Fig. 11B, we can conclude that about 36% simulations are executed in about 0.7 s. Puncture experiments verify the effectiveness of proposed algorithms. The puncture error is slightly larger than the path planning error, due to the torsion caused by friction force and accuracy of puncture platform. The results also suggest that with the increasing of path planning accuracy, the puncture accuracy will also be improved. Note that the puncture experiments are 2D due to gelatin opacity. The simulations are under the assumptions such as constant curvature, perfect rotation transmission and tissue homogeneity. However, these are impossible in reality. For example, the rotation of needle base cannot be perfectly transmitted to the needle tip because of the friction along the needle shaft. The validating experiments just demonstrate the trends rather than absolute accuracy. In this study, we just studied and compared the influence of parameters of basic PSO on flexible needle path planning. As described in the introduction, RRT-based methods are also widely used. According to Cai et al. (2020), simulations illustrate that the path planned by RRT is more accurate than simple PSO. However, there are more turns than the path planned by PSO. Because of imperfect transmission of rotations from the needle base to needle tip, more turns introduce larger errors in real puncture experiments. In the near future, we will focus on the application of proposed algorithms on intraoperative path planning, closed-loop path planning and path planning with different layers. We will also study the solving of local minimum of PSO and path deviation correction. We will also study the mathematic model of PSO algorithms. The accuracy of puncture platform will also be improved in the near future. This study only focuses on the performances of PSO. We will also study other suitable optimization algorithms to improve the path planning accuracy.

Conclusions

In this study, the effects of PSO parameters on path planning for flexible needles were investigated. The optimal combination of parameters was determined by the GA with the Lord strategy. PSO with optimized parameters can significantly improve the accuracy of the planned path. Although some deviations are near zero, due to the local optima, it is still possible for the PSO to obtain paths with large deviations. Therefore, the population size is increased, and much better performance is obtained at the cost of linearly increasing consumption time. To achieve excellent performance in a reasonable time frame according to the results of the effects of the parameters, I-PSO has been proposed. Simulations demonstrate that the planning accuracy of I-PSO is within 0.001 mm with an average time of 0.461 s for Scenario II, which is beneficial for intraoperative fast-path replanning. Compared to PSO and AIPSO, proposed algorithm can significantly improve the path planning accuracy and greatly reduce the computation time. This study demonstrated that a straightforward PSO can obtain high-precision paths without increasing its complexity.

Although the results of I-PSO are better than those of other methods, there are some limitations, since the condition of the simulation experiment is that the texture of the puncture gelatin is uniform, which is difficult to achieve in the real experiment, whether the gelatin is uniform has a certain impact on the experiment. At the same time, three-dimensional path planning was used in the simulation experiment, but due to the low permeability of gelatin tissue, the path puncture under two-dimensional conditions was verified in the experiment, which also had certain limitations on the experiment.

The subsequent phase of this research will prioritize two synergistic technical trajectories: performance stabilization of particle swarm optimization algorithms and advancement of closed-loop path planning systems. For PSO enhancement, dynamic parameter adaptation mechanisms warrant in-depth exploration, particularly through the integration of online meta-learning frameworks to achieve real-time inertia weight adjustment.

Supplemental Information

Calculate the center of the circle after a certain rotation of the flexible needle through the D-H matrix through the code.

The influence of parameters on particle swarm.

The optimal parameter of PSO under the premise of obstacles.

I-PSO path planning.

The puncture method to obtain the optimal trajectory by bringing the obtained center position of the circle, the best parametric sum, the coordinates of obstacles and the radius of flexible needle puncture into it. The ideal puncture trajectory and the puncture method to obtain the trajectory can be obtained through the three files.