Optimizing course assignment in higher education using natural language processing and semantic similarity

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Davide Chicco

- Subject Areas

- Computer Education, Data Mining and Machine Learning, Natural Language and Speech

- Keywords

- Course assignment optimization, Natural language processing, Semantic similarity, Faculty preference modeling, Hungarian algorithm

- Copyright

- © 2026 Cotera-Ramírez et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2026. Optimizing course assignment in higher education using natural language processing and semantic similarity. PeerJ Computer Science 12:e3557 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3557

Abstract

Background

Most studies on course assignment in higher education rely primarily on administrative criteria or heuristic optimization, focusing on workload balance or availability constraints. However, they rarely account for the semantic alignment between course content and professors’ academic profiles. Existing models typically frame course assignment as integer or mixed linear programming problems, overlooking the rich textual information embedded in course plans, faculty training, experience, and publications. Although some authors acknowledge the relevance of professors’ preferences, few have systematically incorporated them into their models in combination with semantic similarity. This gap limits the assignment process in terms of both fairness and transparency, particularly in universities where courses and faculty profiles are highly specialized and heterogeneous.

Methods

To address this gap, we propose a model that integrates natural language processing (NLP) techniques with faculty preferences for course assignment. First, three topic modeling methods—Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA), Top2Vec, and BERTopic—were compared using UMASS, coefficient of variation (Cv), and normalized pointwise mutual information (NPMI) coherence metrics; BERTopic achieved the best performance. Next, three sentence transformers (multi-qa-mpnet-base-dot-v1, all-MiniLM-L6-v2, and all-mpnet-base-v2) were evaluated with cosine similarity, with multi-qa-mpnet-base-dot-v1 selected for its superior embeddings. Standard preprocessing steps (case normalization, stopword removal, lemmatization) were applied before generating semantic representations. A weighted similarity score combined semantic similarity (70%) with professor preferences (30%). Five assignment strategies were then tested under identical conditions: manual, greedy, Hungarian algorithm, similarity-threshold (0.65), and a hybrid Hungarian + threshold approach. The hybrid method was selected for its balance of accuracy and feasibility. Finally, two versions of the model—with and without preferences—were compared to assess the impact of incorporating professor preferences.

Results

All strategies were evaluated under identical conditions using precision, recall, and F1-score on a dataset of 42 courses and 35 professors. The hybrid strategy combining the Hungarian algorithm with a similarity threshold (0.65) performed best, achieving precision = 1.00 (100%), recall = 0.2736 (27.36%), and F1-score = 0.4296 (42.96%). The threshold-based method also reached perfect precision (1.00), with recall = 0.2925 and F1-score = 0.4525. The Hungarian algorithm alone obtained 0.8286, 0.2736, and 0.4113, respectively. The Greedy method performed less well (0.7143, 0.2358, 0.3546). Human-made assignments showed the lowest performance, with precision = 0.0227, recall = 0.0094, and F1-score = 0.0133.

Introduction

Assigning courses to professors is a fundamental administrative task in higher education institutions. It has a direct impact on teaching quality, the balance of academic workload, faculty satisfaction, and institutional efficiency. However, the assignment process is often carried out manually, based mainly on administrative criteria such as faculty availability, seniority, or contractual conditions, with pedagogical and academic alignment between faculty experience and course content taking a back seat. This misalignment can negatively affect the quality of course teaching, student motivation, and outcomes (Chen et al., 2023; Schaerf, 1999; Griffith & Altinay, 2020).

Generally, research related to this topic has modeled the allocation problem as an optimization/resource allocation challenge using approaches such as mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) (Algethami & Laesanklang, 2021; Domenech & Lusa, 2016; Shohaimay, Dasman & Suparlan, 2016; Rappos et al., 2022), various heuristics/metaheuristic (Ghaffar et al., 2025) such as genetic algorithms or ant colony optimization/tabu search techniques (Bashab et al., 2020; Siddiqui & Arshad Raza, 2021; Alhawiti, 2014), and constrained programming approaches (Khurana et al., 2023; Khensous, Labed & Labed, 2023; Montejo-Ráez & Jiménez-Zafra, 2022). Although these methods have proven efficient at managing operational constraints, they largely overlook the valuable unstructured textual information contained in course descriptions, curricula, teacher training, experience narratives, and research publications. As a result, these models fail to capture the semantic relationships that indicate whether a professor’s academic profile aligns with a course’s conceptual and technical content.

In the other hand, research in natural language processing (NLP) has advanced rapidly, especially in semantic representation through topic modeling, contextual embeddings, and transformer-based architectures (Faudzi, Abdul-Rahman & Rahman, 2018; Arratia-Martinez, Maya-Padron & Avila-Torres, 2021; Qu et al., 2014). NLP applications in educational settings have mainly focused on analyzing student activity, such as comment analysis, sentiment detection, content classification (Supriyono et al., 2024), and providing personalized support, leaving aside teacher-centered decision-making processes (Mat, Awangali & Nurul, 2020; Fieldsend, 2017; Chen et al., 2021). Although there are reports of the use of ontologies or keyword-based methods to support academic planning (Chen, Werner & Shokouhifar, 2023; Stojanov & Daniel, 2024; Hamdan, Ibrahim & Hawash, 2024), they do not incorporate current semantic embedding techniques capable of capturing deeper conceptual relationships between the course content and the professor’s profile.

Despite the abundance of research on course assignments (Shohaimay, Dasman & Suparlan, 2016; Bashab et al., 2020; Siddiqui & Arshad Raza, 2021; Khurana et al., 2023; Khensous, Labed & Labed, 2023; Grootendorst, 2022; Reimers & Gurevych, 2019; Naghshzan & Ratte, 2023) and the increasing maturity of NLP methods (Faudzi, Abdul-Rahman & Rahman, 2018; Arratia-Martinez, Maya-Padron & Avila-Torres, 2021; Qu et al., 2014; Blei, Ng & Jordan, 2003), there are a lack of studies that integrate contextual semantic representations of course content and professor profiles into the course assignment process, nor does it evaluate whether these representations, combined with professor’ stated preferences, can outperform human-made or heuristic manual assignments. Current models either do not consider textual data at all or treat it superficially, missing out on the advantages of transformer-based embeddings that have been shown to contain high semantic representation across a wide range of domains.

This study aims is developing a course-professor assignment model that combines semantic similarities from sentence transformer (multi-qa-mpnet-base-dot-v1 used by BERTopic), and matching the course content to the professors’ preferences as explicitly stated. The assignment model will allow the educative management to assess how closely the professor’s profile is aligned with the course content, based on various aspects (education, professional experience, and personal/publications). Using these multiple dimensions of textual data will provide additional validity to the assignment process, and provide a means of determining if the assignment process (i.e., course-professor matching) was completed in a more systematic and transparent manner. Additionally, an evaluation study was completed comparing the effectiveness of the course-professor assignment model with five (5) differing assignment strategies (Greedy algorithm; Hungarian algorithm; threshold-based (target groups based on preferences); hybrid Hungarian algorithm based on both target groups and thresholds; and human-made assignments). Empirical evidence was provided indicating that statistical analyses completed using Shapiro-Wilk; Kruskal-Wallis; and Dunn tests, support the statistical validity of these findings.

The findings indicate that semantic similarity and faculty preference significantly improve the effectiveness of assignment(s) by eliminating random assignments and using an algorithm to compute the most appropriate match, rather than conventional manual assignment methods (similar to traditional practices). This research presents a framework for developing a reproducible process for implementing and assessing the best practice for pairing courses with faculty.

Related work

Assignment problems have been extensively studied in diverse domains, including entertainment, housing, partnerships, accommodation, and education. This section reviews relevant research addressing these models within educational management contexts, emphasizing higher education. Table 1 summarizes the related works, highlighting the elements that served to address the present study.

| Year | Strategy/Approach | Author(s) | Summary of contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | Integer Linear Programming (ILP) | Rakgomo, Mhalapitsa & Seboni (2023) | Models the lecturer–course assignment as an extended transportation problem incorporating workload, credits, groups, and capacity constraints. Validated using real institutional data. |

| 2017 | Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) | Ongy (2017) | Formulates the problem as MILP considering faculty competence, preferences, and institutional workload requirements. Aims to balance multiple objectives in assignment decisions. |

| 2020 | Kotwal-Dhope Method (LP + Hungarian + MOA) | Wulan et al. (2020) | Addresses unbalanced assignment in MOOC development using a hybrid optimization method combining classical linear programming with Hungarian and MOA adjustments. |

| 2022 | MILP with advanced scheduling constraints | Cutillas & Díaz (2022) | Proposes a comprehensive MILP model that integrates diverse teaching loads, credit types, faculty ranks, and preferences. Validated with datasets from two departments at UPV. |

| 2020 | Competency-based MILP | Szwarc et al. (2020) | Develops a competency framework linking course requirements to instructor skills, integrated into an MILP model to maximize instructor satisfaction while respecting workload constraints. |

| 2022 | ILP for tutor allocation | Caselli, Delorme & Iori (2022) | Builds an ILP model to maximize tutor preferences under skill constraints, contract-based working hours, and workshop simultaneity restrictions. Achieved a 29% improvement in preference satisfaction. |

| 2021 | Genetic algorithm | Ngo et al. (2021) | Applies a GA to balance student needs with instructor workload, incorporating competency alignment. Tested with real data from FPT University. |

| 2022 | Tabu Search | Laguardia & Flores (2022) | Implements a Tabu Search metaheuristic for large-scale course scheduling and instructor assignment, handling complexity while generating high-quality solutions for >200 courses. |

| 2024 | NLP for student feedback analysis | Sunar & Khalid (2024) | Systematic review on NLP techniques (LSTM, BERT) for analyzing student feedback, highlighting improvements in sentiment classification and instructor evaluation. |

| 2022 | NLP + semantic analysis of open-ended responses | Yamano et al. (2022) | Applies NLP and co-occurrence analysis to extract latent themes from student free-text responses on sustainability education. |

| 2014 | NLP in educational processes | Alhawiti (2014) | Provides an overview of NLP applications in education, including automated assessment, writing support, and content analysis. |

| 2023 | Topic modeling for teaching effectiveness | Chandrapati & Koteswara Rao (2023) | Uses topic modeling and clustering to evaluate teaching efficacy, reducing subjectivity and revealing latent instructional themes. |

| 2020 | Automated text classification | Giannopoulou & Mitrou (2020) | Proposes an AI-based methodology for classifying large ebook collections, improving access and organization of textual resources. |

| 2020 | Aspect-based sentiment analysis | Nikolić, Grljević & Kovačević (2020) | Conducts sentiment and aspect extraction on higher education reviews to uncover patterns in student perceptions. |

| 2024 | Intelligent virtual university design (NLP + digital systems) | Strousopoulos et al. (2024) | Explores the architecture of an intelligent online university environment using NLP and digital learning technologies. |

| 2018 | Semantic similarity for distractor generation | Susanti et al. (2018) | Uses semantic similarity measures to generate distractors for multiple-choice vocabulary questions. |

| 2023 | BERT for short-text classification | Wulff et al. (2023) | Demonstrates that BERT-based embeddings outperform traditional models in classifying short educational texts. |

| 2025 | Large Language Models (LLMs) for academic feedback analysis | Parker et al. (2025) | Applies GPT-4 and GPT-3.5 to analyze course-level student survey feedback using semantic representations. |

Mathematical approaches to professor assignment

Rakgomo, Mhalapitsa & Seboni (2023) describe the assignment of professors to courses as an extension of the transportation problem, where the goal is to allocate resources efficiently—in this case, professors—while meeting constraints such as classroom capacity, contact hours, course credits, and the number of courses per professor. The authors address the problem in a structured manner using integer linear programming techniques and empirical validation. According to Ongy (2017), course-to-professor assignment is recognized as an essential administrative task that must be carried out each semester in academic departments. This approach models the problem as a mixed-integer programming task, where decisions must be based on multiple objectives, including professor competence and scheduling preferences, and meeting institutional workload requirements. In Wulan et al. (2020), the authors tackle the problem of unbalanced assignment using a linear programming approach based on the Kotwal-Dhope method, a combination of the Hungarian method and the matrix one’s assignment (MOA) technique, balancing the cost matrix and making systematic adjustments to achieve an optimal solution that minimizes costs in the development of a massive open online course (MOOC). In their work, Cutillas & Díaz (2022) propose a solution to the course assignment problem using a MILP model, which accounts for specific organizational characteristics, irregular time schedules, different types of credits and groups, faculty ranks and teaching loads, and preferences. The model is validated using real cases with two datasets from the Universitat Politècnica de València (UPV): the first for faculty assignment in the linguistics department, evaluating solution quality and computational efficiency, and the second for faculty assignment in industrial management engineering, assessing the scalability and speed of the methodology. In Szwarc et al. (2020), the main problem addressed by the authors is the assignment of professors to courses so that professor satisfaction is maximized while meeting various operational constraints, such as the competencies required for each course, professors’ minimum and maximum workloads, and the balanced distribution of tasks among available faculty. To achieve this, they create a competency framework linking course requirements with professor competencies. Optimization is carried out through a mixed-integer linear programming model. In the study by Caselli, Delorme & Iori (2022), the authors develop an integer linear programming (ILP) model to maximize tutor preferences when assigning workshops, subject to constraints such as tutor skills and competencies, maximum tutoring hours based on employment contracts, simultaneous workshops, and tutors’ preferences for teaching specific workshops. The model was tested in the 2019–2020 academic year, resulting in a 29% increase in tutor preferences compared to manual assignments.

Artificial intelligence approaches

In Ngo et al. (2021), the problem of assigning professors to courses is addressed using a genetic algorithm that balances student needs with professor workload, ensuring a degree of robustness in teaching schedules. This approach involves identifying links between professor competencies and those required by the curriculum courses. The algorithm was implemented and tested using data from the Spring 2020 semester of the Department of Computer Fundamentals at FPT University. In Laguardia & Flores (2022), the authors propose a solution based on a Tabu Search algorithm, a metaheuristic that iteratively improves solutions through minor changes and avoids local optima using an adaptive memory called the Tabu list. They define an objective function that considers the essential qualities of an assignment while controlling computational complexity, allowing for multiple iterations within a reasonable timeframe. Several tests were conducted using data from the Department of Exact Sciences at the Technological University of Panama, covering 205 courses and 71 professors.

Natural language processing approaches

The use of NLP techniques in academic activities is fundamentally student-centric, potentially significantly enhancing efficiency and personalization in higher education. A systematic review by Sunar & Khalid (2024) delves into how NLP techniques are applied to analyze student feedback to professors, highlighting deep learning algorithms such as long short-term memory (LSTM) and bidirectional encoder representations from transformers (BERT) to improve the accuracy of sentiment analysis and feedback categorization. The development of chatbots like Infobot, capable of instantly responding to student queries across various social platforms, has significantly reduced professors’ workload, fostering interaction and personalized assistance in university courses (Lee et al., 2020). Moreover, applying advanced NLP techniques and co-occurrence network analysis in the analysis of open-ended responses has deepened our understanding of students’ perceptions of sustainable development, as Yamano et al. (2022) demonstrated in their study on education for sustainability. NLP has also made significant advances in the field of educational management, with the most commonly reported use being the automation of tasks involving the processing of large amounts of text, such as creating assessments, topic analysis, course recommendations, and student support. Alhawiti (2014) presents an overview of how NLP improves educational processes, including writing assistance, assessment feedback, and subject analysis. Focusing on management, Chandrapati & Koteswara Rao (2023) employed topic modeling and text clustering to empirically evaluate professor effectiveness empirically, thereby eliminating subjectivity and exploring latent topics that are difficult to perceive individually.

For her part, Giannopoulou & Mitrou (2020) proposes a methodology for the automatic classification of a collection of e-books of various types, using index information. Her work demonstrates how NLP can be used to improve access to and organization of large amounts of text. Nikolić, Grljević & Kovačević (2020) report on sentiment analysis in higher education reviews, highlighting the advantage of NLP in capturing latent perspectives in the opinions expressed in the texts. Strousopoulos et al. (2024) used NLP strategies to explore the design of a smart online virtual university.

One strength of NLP is the tools for calculating semantic similarities in texts. In this regard, NLP, utilizing similarity measures, is employed to enhance and adapt teaching dynamics to new educational technologies. Susanti et al. (2018) used semantic similarity to generate distractors for multiple-choice questions. Wulff et al. (2023) found that BERT-generated embeddings outperform other traditional architectures in classifying short educational texts. This research reinforces our decision to use semantic similarity measures in conjunction with advanced transformer-based models, such as multi-qa-mpnet-base-dot-v1.

In the development of large language models (LLMs), the approach of using NLP in management tasks that often require manual processing is validated. It can facilitate the implementation of solutions through application programming interfaces (APIs). Parker et al. (2025) used the GPT-4 and GPT-3.5 models to analyze feedback data from student surveys. They used semantic representations to extract information at the course level. The work demonstrates the application of language models in the semantic analysis of academic content written by students.

Topic modeling

Internet technology and Big Data provide abundant information that has significantly transformed society and the economy, and their application in education has attracted considerable attention. Shaik et al. (2022) studied artificial intelligence in personnel management, exploring opportunities and challenges for the higher education sector.

Top2Vec

This method does not require traditional preprocessing steps and automatically determines the number of topics, generating vectors representing documents and words in a shared semantic space. The process follows four phases: creation of a semantic embedding, identification of the number of topics through density-based clustering, calculation of topic vectors as centroids of dense document regions, and hierarchical topic reduction to facilitate interpretation (Angelov, 2020).

BERTopic

BERTopic is an unsupervised machine learning model that leverages pre-trained language models such as BERT or robustly optimized BERT pretraining approach (RoBERTa) to generate document embeddings, clusters these embeddings, and creates topic representations using class-based term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF-IDF). It effectively uncovers the underlying thematic structure in large textual datasets and facilitates topic exploration (Grootendorst, 2022; Reimers & Gurevych, 2019; Naghshzan & Ratte, 2023). The process begins by creating embeddings from a document set, producing a 384-dimensional document matrix (D) using BERT. A specific embedding represents each document (Dn). Dimensionality reduction is then performed using uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP), followed by clustering with hierarchical density-based spatial clustering of applications with noise (HDBSCAN). After completing these steps, the model can extract topics from the clusters and generate visualizations.

Latent Dirichlet allocation

Latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA) is a generative probabilistic model that assumes documents are composed of a mixture of topics, where a distribution over words characterizes each topic. It helps discover latent thematic structures in extensive collections of text in an unsupervised manner (Wang et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2011; Harrison & Sidey-Gibbons, 2021; Udupa et al., 2022).

Coherence metrics

UMASS. Based on the conditional co-occurrence of words within the corpus, this metric helps evaluate the internal cohesion of topics. However, its performance heavily depends on the corpus size (Mimno et al., 2011).

Cv measures topics’ semantic coherence by combining cosine similarity with text segmentation strategies, providing a more robust measure than other traditional metrics (Röder, Both & Hinneburg, 2015).

NPMI. This metric assesses the statistical relationship between words within the same topic, normalizing co-occurrence probability and reducing the bias introduced by frequent words (Bouma, 2009).

Materials and Methods

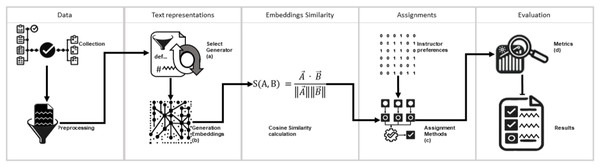

This study proposes a model for assigning courses to professors based on NLP techniques. This model optimizes the assignment by considering the semantic similarity between course contents and professor profiles and their explicit preferences. Five assignment approaches were compared: the greedy method, the Hungarian algorithm, a similarity-threshold-based method, a hybrid method Hungarian algorithm with filter threshold, and Human-made assignments evaluating accuracy with respect to professor preferences. Figure 1 illustrates the methodological diagram of this study.

Figure 1: Graphic description of the present study.

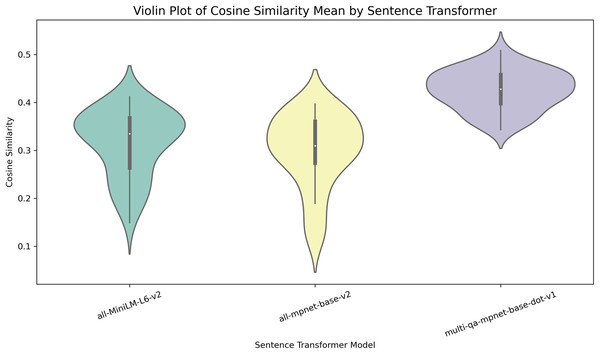

The research was conducted in five stages. The graph shows the process followed in each stage. Letters (a), (b), (c), and (d) detail the evaluation and element selection processes used to create the model. (A) The topic modeling algorithms BERTopic, LDA, and Top2Vec underwent a comprehensive evaluation. The UMASS, Cv, and NPMI coherence metrics were meticulously applied to ensure the quality of the generated topics was thoroughly assessed. (B) Embeddings were generated using the sentence encoder multi-qa-mpnet-base-dot-v1. In this stage, the sentence encoders all-MiniLM-L6-v2 and all-mpnet-base-v2 were explored but not used as they yielded suboptimal performance. (C) Three approaches were explored to select an assignment method. (1) Greedy method, (2) a method based on the Hungarian algorithm, and (3) a threshold-based method. The method based on the Hungarian algorithm was selected. (D) The results were evaluated using widely accepted and trusted metrics: precision, recall, and F1-score.To select the topic generator and sentence transformer, an experiment was conducted using three topic generators: LDA, Top2Vec, and BERTopic, to determine which one created a better representation of the documents in the dataset. The generators were evaluated using the UMASS, Cv, and NPMI metrics. BERTopic was selected because it achieved higher scores on the consistency metrics. We then created BERTopic models to evaluate three sentence transformers: multi-qa-mpnet-base-dot-v1, all-MiniLM-L6-v2, and all-mpnet-base-v2.-using the cosine similarity metric. Multi-qa-mpnet-base-dot-v1 was selected because it performed better. The results are shown in the Table 2. The sentence transformer was selected using descriptive statistics of cosine similarity. Figure 2 shows the median values of the similarities.

| Metric | LDA | BERTopic | Top2Vec |

|---|---|---|---|

| UMASS | 0.00022 | 0.00176 | 0.00001 |

| Cv | 0.00080 | 0.00072 | 0.00303 |

| NPMI | 0.00040 | 0.01238 | 0.00013 |

Figure 2: Distribution of cosine similarity metric values for each sentence transformer.

Each figure indicates how the values are distributed for each sentence transformer using the cosine similarity metric.Description of components (a), (b), (c), and (d) of Fig. 1.

-

(a)

The topic modeling algorithms BERTopic, LDA, and Top2Vec underwent a comprehensive evaluation. The UMASS, Cv, and NPMI coherence metrics were meticulously applied to ensure the quality of the generated topics was thoroughly assessed.

-

(b)

Embeddings were generated using the sentence encoder multi-qa-mpnet-base-dot-v1. In this stage, the sentence encoders all-MiniLM-L6-v2 and all-mpnet-base-v2 were explored but not used as they yielded suboptimal performance.

-

(c)

Three approaches were explored to select an assignment method. (1) Greedy method, (2) a method based on the Hungarian algorithm, and (3) a threshold-based method. The method based on the Hungarian algorithm was selected.

-

(d)

The results were evaluated using widely accepted and trusted metrics: precision, recall, and F1-score.

The model was evaluated by comparing its precision and F1-score against human-made assignments and recorded professor preferences.

For each assignment strategy—Greedy, Hungarian, threshold, Hungarian+threshold, and human assignments—we computed precision, recall, and F1-score at two levels of granularity:

Course-level metrics: Each course was treated as a separate binary classification problem, where a positive case indicates that the assigned professor matches the explicit preferences.

Professor-level metrics: Each professor was analyzed individually, calculating how many of their preferred courses were successfully assigned by each strategy.

We used non-parametric statistical tests (Kruskal–Wallis H-test followed by Dunn’s post-hoc test with Bonferroni correction) to verify whether the differences observed at this fine-grained level remained statistically significant across strategies.

This study is guided by the central research question: How can natural language processing and semantic similarity improve the assignment of academic courses to university faculty? While no formal hypotheses are stated, the experimental design addresses this overarching question through a comparative inquiry set. Specifically, the analyses focus on determining whether assignments based on semantic similarity outperform historical human-made assignments using precision and F1-score metrics, whether integrating professor preferences improves assignment quality, and whether optimization methods such as the Hungarian algorithm with a similarity threshold offer advantages over baseline strategies. These guiding questions structure the selection of evaluation metrics, the comparative framework among strategies, and the statistical analyses used to support the study’s conclusions.

Controls against circularity.

We evaluate (i) a similarity-only model (β = 0) and (ii) a similarity+preferences model (with β < α) under identical data and algorithms. We further run a sensitivity analysis over β ∈ [0, 0.5] and report precision/recall/F1 as a function of β. Finally, we decouple scoring and acceptance via a similarity threshold applied after optimization (Hungarian + threshold) to demonstrate that perfect precision results from conservative filtering, not from preferences acting as ground truth in training.

Dataset

The dataset used in this study was extracted from administrative systems and databases at the Faculty of Computer Science, Universidad Técnica de Manabí. Three primary datasets were utilized.

-

(1)

Course contents and professor profiles: documents for 35 professors and 42 courses. Each professor has three documents detailing training, experience, and publications.

-

(a)

Professor profile attributes.

-

(i)

Training: description of subject matter or content.

-

(ii)

Experience: Name of the subject, minimum contents of the subject.

-

(ii)

Publications: title

-

-

-

(2)

Administrative records of historical assignments from six academic periods between 2020 and 2023, comprising 288 records.

-

(a)

Historical assignments: course, Professor

-

-

(3)

There are 1,470 professor preference records, indicating binary values (0 or 1) for each course per professor, reflecting whether it is preferred

-

(a)

Attributes of preference records: Course, Professor, Selection (0|1)

-

These datasets were selected for their practicality in course management and the availability of historical data.

Preprocessing

Text preprocessing followed standard practices in NLP To ensure practical analysis and performance of the topic-generation models.

Conversion of texts to lowercase.

Removal of special characters, punctuation, and irrelevant numbers.

Normalization of whitespace.

Remove Spanish-language stopwords using standard stopword lists from NLTK and spaCy.

Removal of recurrent administrative terms lacking semantic value for topic detection.

Tokenization of texts using spaCy.

Lemmatization to reduce words to their base form (e.g., “procesando”→ “procesar”).

Generation of semantic representations

A comparative study was conducted between three topic-generating models–LDA, BERTopic, and Top2Vec–which are widely used in NLP tasks. The evaluation focused on analyzing the semantic coherence of the generated topics concerning the training dataset. For this comparison, three coherence metrics recognized in the literature were used–UMASS, Cv, and NPMI–each with different statistical and linguistic foundations that allow for assessing the interpretive quality of the extracted topics.

Since BERTopic internally uses contextual embeddings, its superior performance on NPMI and Cv when creating representations of the dataset suggests a more accurate semantic structuring for our task. It justifies its selection as the model for creating our semantic representations.

Inlays generated with BERTopic were used to represent course and Professor profiles. To obtain the embeddings, three BERTopic models were created, each model using an all-MiniLM-L6-v2, all-mpnet-base-v2 and multi-qa-mpnet-base-dot-v1 sentence transformer respectively. Documents were fed into the created model and the embeddings were obtained. Subsequently, semantic similarities were evaluated. The multi-qa-mpnet-base-dot-v1 sentence transformer was selected as it obtained the highest semantic similarities in the evaluations.

Similarity calculation

The similarity matrix was constructed to determine the optimal course assignment to professors based on the semantic analysis of course descriptions and professor profiles. Text embeddings generated with the multi-qa-mpnet-base-dot-v1 model were used, and cosine similarity between the representative vectors of each course and the professor was calculated.

Cosine similarity is defined as follows:

(1) where:

A is the embedding representation vector of the course.

B is the professor’s embedding representation vector.

The cosine similarity results range between −1 and 1. Values closer to 1 indicate higher semantic similarity between the course and the professor. Since the embeddings used are generated from representations in high-dimensional vector spaces, cosine similarity is an appropriate metric because it measures the orientation between vectors without being influenced by their magnitude.

The cosine similarity was calculated for each course-professor pair, resulting in a similarity matrix of dimensions A × B, where A = 42 courses and B = 35 professors. This matrix served as the basis for course assignments, optimizing allocations through the Hungarian algorithm and applying a similarity threshold to enhance the model’s accuracy.

Previous explorations determined the factors and weights for each factor. The final similarity between courses and professors was calculated by combining training, experience, and publication factors with an professor preference factor using the Equation:

(2) where:

FS: Final Similarity

SS: Semantic Similarity

PP: Professor Preference

Assignment methods

Three assignment methods were tested. (1) The greedy method assigns each course to the professor with the highest similarity in each iteration. (2) the Hungarian algorithm identifies the optimal assignment by minimizing the cost matrix derived from similarities. (3) The similarity-threshold-based method assigns courses to professors only if their similarity exceeds a predefined threshold. The operation of each method is detailed below.

Greedy method

The Greedy method is a heuristic strategy that selects the best local assignment at each iteration without considering the impact on future assignments. Its goal is to assign each course to the professor with the highest similarity available at that moment (Brassard & Bratley, 1996).

The algorithm follows these steps:

All possible course-professor assignments are sorted in descending order according to Final Similarity.

The course is assigned to the professor with the highest available similarity, avoiding repeated assignments.

The process is repeated until all courses are assigned or no viable assignments remain.

The assignment criterion is formally defined as:

(3) where:

A is the set of courses.

B is the set of professors.

P represents all possible course-professor assignments.

Hungarian algorithm

The Hungarian algorithm (Kuhn, 1955; Munkres, 1957) is a combinatorial optimization method designed to solve assignment problems optimally. It finds the minimal-cost matching in a cost matrix or, in this context, determines the optimal assignment of courses to professors based on similarity.

Algorithm steps

Represent the problem as a cost matrix C of size N × M, where Cij denotes the cost of assigning course i to professor j.

Subtract the minimum value from each row and each column of the matrix.

Identify optimal assignments through iterative matrix reduction steps.

Assign courses to professors by minimizing the cost or, in this scenario, maximizing similarity.

Given a set of courses A and a set of professors B, the assignment problem is formally defined as:

(4)

Subject to:

(5)

(6)

(7) where Xij = 1 if course i is assigned to professor j, and Xij = 0 otherwise.

Similarity-threshold-based method

The similarity-threshold-based method assigns courses to professors only if their similarity exceeds a predefined threshold. This approach avoids assignments with low similarities, thereby enhancing the quality of the allocation (Ricci, Rokach & Shapira, 2011).

Algorithm operation:

Define a similarity threshold α; in this study, α = 0.65.

Select the highest similarity available for the course i.

If the selected similarity is greater than or equal to the threshold α, assign course i to professor j (Xij).

Repeat this process for all courses.

Mathematically, the assignment is constrained as follows:

(8)

Evaluation metrics

The precision, recall, and F1-score metrics were used to evaluate the quality of the assignments, taking the professor preference matrix as the absolute truth. In this study, the calculation of recall and F1-score is used not as measures of interactive response (as is done in recommender systems) but as metrics of comparison between the models’ assignments (Dalianis, 2018; Yacouby & Axman, 2020) and the professors’ explicit preferences, considered as the reference truth. These metrics allow us to quantify how many of the assignments made by the model coincide with the professors’ preferences, as well as the balance between hits and misses.

Metrics relevance

Precision indicates the percentage of courses correctly assigned out of all assignments calculated by the model. In academic management, a high accuracy value indicates that the model avoids suboptimal assignments. It minimises conflicts with institutional policies or between the alignment of course-professor profiles.

Precision (P) refers to the percentage of assignments generated by the model that correctly aligns with the professors’ preferences.

(9)

Formally defined as:

(10) where:

True Positives (TP): Correct assignments according to professor preferences.

False Positives (FP): Incorrect assignments according to professor preferences.

Recall assesses the portion of courses that the model has assigned correctly and that are preferred or suitable for a professor. A high value in this metric indicates the model’s ability to comprehensively calculate professor suitability, ensuring that all profile dimensions and their corresponding weights have been considered and accounted for.

Recall (R) was calculated, measuring the percentage of professor-preferred assignments correctly identified by the model:

(11)

Mathematically defined as:

(12) where:

TP are assignments made by the model matching professor preferences.

False Negatives (FN) are professor-preferred assignments not made by the model.

F1-score, the harmonic mean of precision and recall. It balances the assignments that were matched and the preferences that were covered by the assignment strategy. It is essential for institutional efficiency and professor satisfaction, as it is crucial to achieve an assignment that avoids incorrect matches (precision) of unwanted or misaligned courses with the professor, while maximizing the correct ones (recall) of the most significant number of aligned courses within the correct assignments made by the model.

The F1-score (F1) was also calculated to evaluate the overall quality of the model, as it balances precision and recall:

(13) where P identifies precision, and R represents recall.

The F1-score is particularly useful in course assignments since a high precision with low recall implies very accurate assignments but leaves many courses and professors unassigned, whereas a high recall with low precision results in numerous assignments that do not align with professor preferences.

To define the metrics in practical terms, evaluation with these metrics directly reflects the balancing act faced by the academic decision-maker in each period. For example, an assignment with high precision but low recall can result in very accurate but incomplete assignments, while a balanced F1-score ensures that assignments are reliable and reasonably complete.

Statical analysis

In this study, several statistics methods were used to verify that the model inference, based on the evaluation parameters and the composition of the experimental data. The usual standard evaluation metrics for classification and information retrieval models such: accuracy, recall, and F1-score are limited, non-negative, and commonly biased. These metrics also tend to violate the assumptions of normality and homoscedasticity required for parametric tests; in this sense, the Shapiro-Wilk test was applied, which is highly sensitive with small samples, as in this case.

Taking into account the results of the Shapiro-Wilk test (Table 2) and, the Kruskal-Wallis H test was selected as a nonparametric alternative to one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare independent groups without assuming Gaussian distributions. In order to make pairwise comparisons and identify which pairs differed Dunn’s post hoc test with Bonferroni correction was used.

Computational resources

The following computational resources were employed for the implementation and execution of the course-to-professor assignment model:

Hardware:

Processor: Intel Core i7-12700K (12 cores, 20 threads)/AMD Ryzen 9 5900X

RAM: 32 GB DDR4 3200MHz

Graphics Card (for embedding acceleration): NVIDIA RTX 3060 (12 GB VRAM)/NVIDIA A100 on Google Colab

Storage: 1TB NVMe SSD

Software and libraries:

-

Programming Language: Python 3.9

-

Execution Environment: Google Colab/Local Jupyter Notebook

-

Libraries:

-

○

Transformers and SentenceTransformers (multi-qa-mpnet-base-dot-v1)

-

○

Gensim (for topic generation using LDA)

-

○

BERTopic (for embedding-based topic generation)

-

○

scikit-learn (for similarity computations and evaluation metrics)

-

○

SciPy and NumPy (for optimization using the Hungarian algorithm)

-

Execution time:

Embedding generation: Approximately 5–10 min on graphics processing unit (GPU), ~40 min on central processing unit (CPU).

Cosine similarity calculation and assignment matrix: Approximately 2–5 min.

Hungarian algorithm execution: Less than 1 s for standard-sized matrices (~50 courses, ~30 professors).

These resources ensured efficient processing times, allowing for the creation and testing of the proposed model. Distributed execution in cloud computing environments is recommended in environments with lower computational capacity.

The following section describes the Proposed Model in detail, complementing the previously described methodology. This section is justified by the need to provide a clear and structured explanation of how specific components of the model interact, including semantic embedding generation, integration of professor preferences, and algorithms utilized for optimal course assignments. This division facilitates understanding and reproducibility, highlighting the general methodological approach and the specific structure of the developed model.

Proposed model

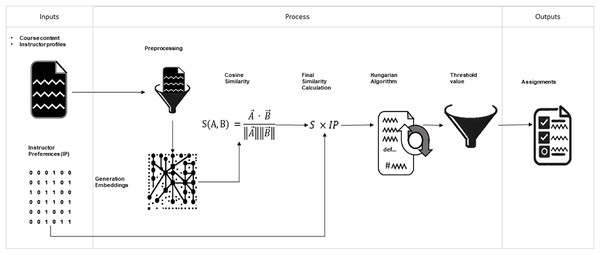

The model developed in this study uses NLP to address the course-to-professor assignment problem. It integrates semantic similarity between course contents and professor profiles, as well as explicit preferences provided by professors.

As input, the model receives records of course content, professor profiles, and assignment preferences previously selected by the professors. In the following stage, this data undergoes standard preprocessing procedures in NLP:

Conversion of text to lowercase.

Removal of special characters, punctuation, and irrelevant numbers.

Normalization of whitespace.

Remove Spanish stopwords using stopword lists from NLTK and spaCy.

Elimination of recurrent administrative terms with no semantic value for topic detection.

Tokenization of text into words using spaCy.

Lemmatization.

Once the data is preprocessed, a pivotal phase for the model’s effectiveness, we move on to semantic representation. Here, we employ the state-of-the-art BERTopic and the high-performing multi-qa-mpnet-base-dot-v1 embedding model from SentenceTransformers. This tool choice underscores our model’s cutting-edge nature, ensuring it is equipped with the best resources for semantic representation tasks.

Cosine similarity between the generated embeddings is used to evaluate compatibility between courses and professors. Cosine similarity is defined by Eq. (1), as indicated in the methodology section. A similarity matrix of size N × M is obtained, where N represents the number of courses and M is the number of available professors. This matrix is referred to as semantic similarity.

Subsequently, to explicitly incorporate professor preferences, semantic similarity is weighted with the explicit assignment preferences using Eq. (2) to compute the Final Similarity matrix. In this study, semantic similarity is weighted at 70%, while professor assignment preferences are weighted at 30%.

Finally, the assignment is performed using the Hungarian algorithm and a similarity threshold filter set at 0.65. The output obtained is a list of courses assigned to professors. Figure 3 graphically illustrates the complete architecture of the model.

Figure 3: General structure of the proposed model. Input files, sequence of processes performed, and output files.

The arrows allow us to track the model’s operation visually. Required inputs, processing phases, embedding creation, similarity calculations, integration of teacher preferences, assignment using the Hungarian algorithm, filtering of low-similarity assignments, and the output, course-teacher assignments.Scoring function and rol of preferences

For each course-professor pair (i, j), we define a composite scrore.

where Simsem is the cosine similarity between embeddings derived from multi-qa-mpnet-base-dot-v1 and Pij indicates explicit professor preference. The assignment is obtained by optimizing ∑i,j Sij Aij under one-to-one matching and institutional constraints. Preferences are not treated as labels to predict but as a secondary criterion that modulates semantically suitable matches.

Ethical considerations

No human subjects were used in this research, nor was there any direct interaction with individuals. All data used in the analysis were obtained, with prior authorisation, from administrative records of the Faculty of Computer Science at the Technical University of Manabí. The dataset did not contain any personal, sensitive, or identifiable information, as all teacher identifiers were anonymised prior to analysis. The research procedures complied with institutional guidelines for the handling of administrative data, and therefore, no formal ethical approval was required. The study poses no risk to individuals, preserves privacy, and complies with standard ethical practices in educational and computational research.

Research contributions and findings

-

1.

This study makes several key contributions to the intersection between NLP, optimisation, and academic course assignment:

-

2.

Assignment framework with semantic understanding. A novel model was proposed that leverages semantic embeddings generated by BERTopic, combined with multi-qa-mpnet-base-dot-v1, to represent both course descriptions and professor profiles.

-

3.

Evaluation of topic-generating models. Three topic modelling techniques (BERTopic, LDA, and Top2Vec) were compared using UMASS, Cv, and NPMI coherence metrics. The model created in BERTopic using the “multi-qa-mpnet-base-dot-v1” sentence encoder demonstrated superior semantic representation and statistical significance in all tests (p < 0.01).

-

4.

Optimisation-based assignment comparison. Systematically, the performance of various assignment strategies (Hungarian, Greedy, threshold, and human assignments) was evaluated using precision, recall, and F1-score. The Hungarian method with a similarity threshold achieved the best overall performance, reaching 100% accuracy.

-

5.

Integration of professor preferences. Including professor preferences as an additional dimension of the dataset significantly improved the assignment results. The model with weighted preferences achieved an F1-score of 0.4113, compared to 0.0993 without preferences, validating the impact of personalization.

-

6.

Although the model does not currently consider student-related factors, students will benefit from receiving classes with the professor best suited to the course. Decision-makers will have access to a data-based support tool to prepare assignments. Professors will be assigned to courses that match their profile, which is expected to improve job satisfaction and academic management.

Results

The results section is divided into three sections that support the work done in the research. The topic modeling evaluation section focuses on the research question that explores the relationship between natural language processing and semantic similarity. “How can natural language processing and semantic similarity …”. In the section “Assignment method comparison”, the authors explore how semantic similarity is applied in different assignment methods and show how they outperform human approaches. The section “The proposed course assignment model” gives a direct answer to “ …improve the assignment …” by showing, with objective metrics, that the proposed model significantly improves on traditional assignments.

Topic modeling evaluation

Among the three topic models tested—BERTopic, LDA, and Top2Vec—BERTopic achieved the highest semantic coherence according to the UMASS, Cv, and NPMI metrics. The comparison was conducted using a representative corpus of course and professor documents, evaluated across different numbers of keywords and multiple random repetitions to ensure stability.

For embedding generation, the multi-qa-mpnet-base-dot-v1 model from the SentenceTransformers library was selected, as it consistently outperformed other tested embedding models, including all-MiniLM-L6-v2 and all-mpnet-base-v2. This transformer model was integrated into the BERTopic pipeline to enhance the semantic granularity of topic representations. Its superior performance in intrinsic and extrinsic similarity tests confirmed its suitability for capturing domain-specific content. The selected model also computed the cosine similarity between course and professor embeddings in downstream assignment evaluations, ensuring consistency throughout the NLP pipeline.

Shapiro-Wilk tests were performed to assess whether the values for each metric in the different models followed a normal distribution. These tests indicated that LDA, BERTopic, and Top2Vec did not follow a normal distribution (p < 0.05) for any metric. Since at least one model did not comply with normality, parametric tests such as ANOVA were ruled out. Table 2 shows Shapiro-Wilk test values.

The Kruskal-Wallis tests, a significant part of our analysis, yielded an H-statistic for each metric: UMASS = 44.2798, Cv = 38.6335, NPMI = 47.6393, with p-values of UMASS = 2.43e−10, Cv = 4.08e−09, NPMI = 4.52e−11. These results indicate that not all models generate topics similarly. We then used Dunn’s test with Bonferroni correction to identify which models were significantly different, further underlining the importance of our findings.

The results of the Dunn test indicate that in the UMASS metric, the three models differ significantly from each other (p < 0.01), with LDA standing out as the model with the most significant difference compared to BERTopic and Top2Vec.

In the Cv metric, BERTopic showed highly significant differences compared to LDA (p < 0.000001) and also compared to Top2Vec (p = 0.00025), while LDA and Top2Vec did not present statistically significant differences between them.

Regarding the NPMI metric, BERTopic had an advantage, with significant differences compared to LDA (p = 0.001675) and Top2Vec (p = 1.536895e−11). Reinforcing its superiority in terms of semantic coherence, which has clear real-world implications for the practical application of these models.

Comparison assignment method

The historical human-made assignments were restricted to a single academic term to ensure fairness in the comparative evaluation of assignment strategies. This approach aligns the evaluation horizon with the automated strategies, each generating assignments for one period. By doing so, we prevent the inflation of recall that may arise when aggregating assignments over multiple historical cycles.

Five assignment strategies were compared:

-

1.

Greedy method

-

2.

Hungarian algorithm

-

3.

Similarity-threshold-based method (threshold = 0.65)

-

4.

Hungarian algorithm + similarity threshold (0.65)

-

5.

Human-made assignments

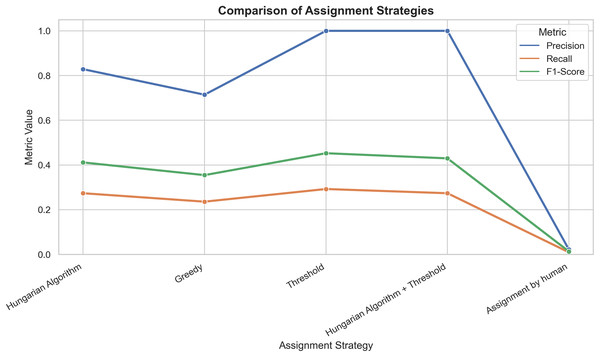

Table 3 compares the precision, recall, and F1-score assignment methods, taking professor preferences as ground truth. The Hungarian algorithm, followed by applying a 0.65 similarity threshold and the threshold-based method, achieved the best precision score of 1.0000 (100%), indicating that all assignments were correct. Figure 4 illustrates the performance metrics among the tested assignment methods.

| Strategy | Precision | Recall | F1-score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human-made assignment | 0.0217 | 0.0094 | 0.0131 |

| Greedy method | 0.7143 | 0.2358 | 0.3546 |

| Hungarian algorithm | 0.8286 | 0.2736 | 0.4113 |

| Similarity threshold-based method (0.65) | 1.0000 | 0.2925 | 0.4525 |

| Hungarian algorithm with similarity threshold (0.65) | 1.0000 | 0.2736 | 0.4296 |

Figure 4: Graphical representation of precision, recall, and F1-score performance for each metric.

Presents a line plot comparing all strategies across the three metrics, visually representing performance distribution. Strategies with higher values represent better course-teacher assignments.It is worth noting that recall and F1-score display similar trends across strategies in Fig. 4. This effect is expected because several NLP-based strategies (threshold and Hungarian+threshold) achieve near-perfect precision values (≈1.0). Under these conditions, the F1-score, defined in Eq. (13), becomes dependent mainly on recall, resulting in comparable value differences between the two metrics. This behavior reflects the mathematical relationship between the two measures under high-precision scenarios rather than a calculation artifact.

The Hungarian algorithm achieved a precision of 0.8286 (82.86%) and an F1-score of 0.4113 (41.13%), surpassing both the Greedy method 0.7143 (71.43%) with an F1-score of 0.3546 (35.46%) and historical human-made assignments 0.0227 (2.27%) with an F1-score of 0.0133 (1.33%). The similarity-threshold-based method achieved a precision of 1.0000 (100%) and an F1-score 0.4525 (45.25%).

The Hungarian algorithm, combined with applying a 0.65 similarity threshold to select only assignments with a high degree of semantic and preferential compatibility, achieved a precision of 100%, significantly improving assignments compared to traditional methods and matching the performance of the similarity-threshold-based method. This strategy achieves a recall value of 0.2736 (27.36%) and an F1-score of 0.4296 (42.96%).

These findings highlight the advantage of integrating semantic similarity and professor preferences into the assignment. The hybrid approach combines optimization and filtering, offering accuracy while meeting institutional constraints.

To investigate whether significant differences existed among the assignment strategies across key evaluation metrics, a Kruskal–Wallis H-test was conducted separately for each metric. The test revealed significant differences among precision, recall, and F1-score strategies when analyzed by course and professor (p < 0.001 for all comparisons).

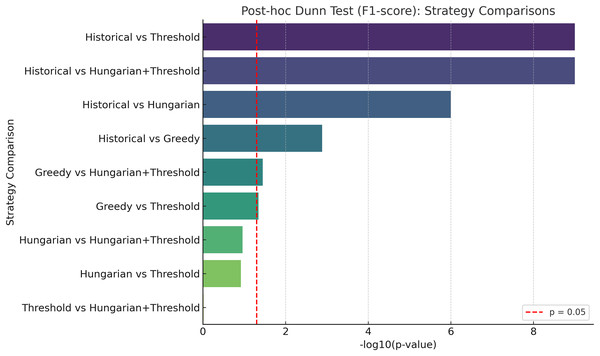

Post-hoc pairwise comparisons using Dunn’s test with Bonferroni correction confirmed that the threshold-based and Hungarian+threshold strategies significantly outperformed the Historical and Greedy methods in both precision and F1-score (p < 0.001). Comparisons such as Greedy vs. threshold and Greedy vs. Hungarian+threshold also reached statistical significance (p < 0.05), though with smaller effect sizes.

The graphical summary in Fig. 5 shows the strength of these differences based on the negative logarithm of p-values, highlighting the superiority of the threshold-integrated strategies. These results provide strong statistical evidence that integrating semantic similarity and faculty preferences yields measurable improvement in assignment quality.

Figure 5: In the graph, each bar represents the difference in the F1-score metrics between the indicated strategies.

A larger bar indicates a more significant difference, regardless of which of the two compared is better. The log10 p-values are represented, with higher values indicating more significant differences. The red line marks the traditional threshold for statistical significance (p = 0.05).Comparison granular assignment method

Results per course

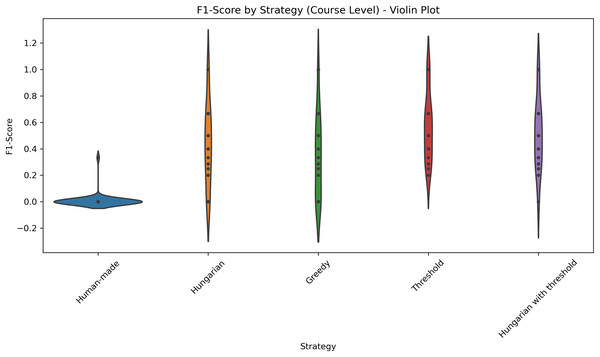

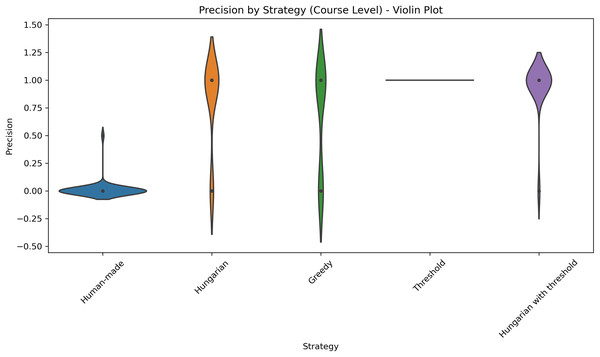

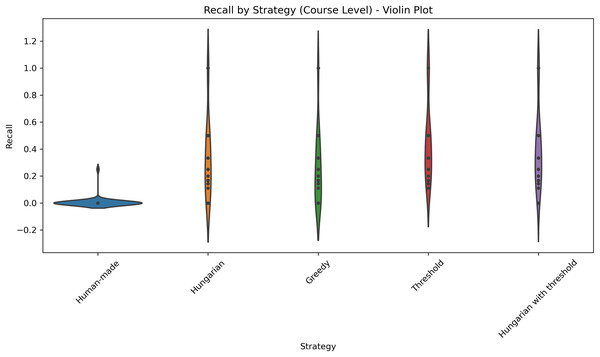

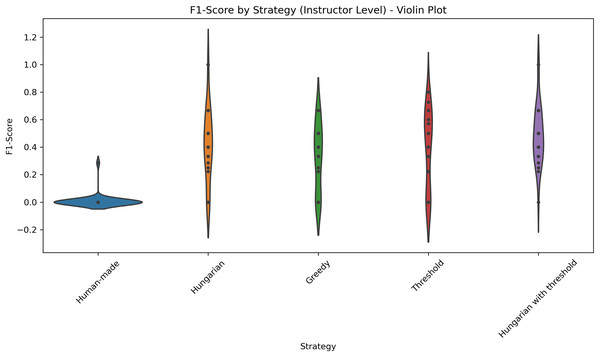

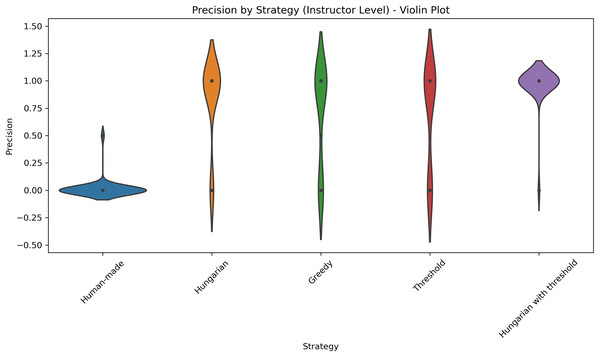

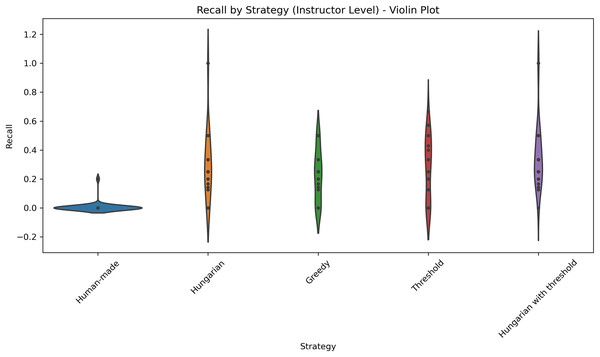

Table 4 summarizes the mean and standard deviation for each metric per course. The results show that the threshold-based method and the Hungarian method and subsequent filtering with a threshold consistently achieve high accuracy for most courses and Professors, while Greedy and human-made assignments have lower accuracy and higher variability. Figure 6 shows the distributions of the F1-scores. Figure 7 shows the distribution of accuracy and Fig. 8 is the graphical representation of the recall measures. We can observe that the NLP-based methods stand out, generating tighter and higher distributions compared to the other methods, while in the human-made assignments we observe a lower median and a larger variability.

| Precision | Recall | F1-score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strategy | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| Human-made | 0.0125 | 0.0791 | 0.0063 | 0.0395 | 0.0083 | 0.0527 |

| Hungarian | 0.8056 | 0.4014 | 0.3321 | 0.2958 | 0.4342 | 0.3067 |

| Greedy | 0.6757 | 0.4746 | 0.2645 | 0.2845 | 0.3517 | 0.3132 |

| Threshold | 1 | 0 | 0.434 | 0.2853 | 0.558 | 0.2498 |

| Hungarian+threshold | 0.9355 | 0.2497 | 0.3856 | 0.2841 | 0.5042 | 0.2706 |

Figure 6: Distribution of F1-scores across five different strategies applied at the course level.

The violin plot illustrates the distribution of F1-scores across five different strategies applied at the course level: Human-made, Hungarian, Greedy, Threshold, and Hungarian with threshold. Each violin displays the density of the scores, highlighting both central tendency and variability. The plot allows for visual comparison of performance consistency and effectiveness among strategies.Figure 7: Distribution of precision across five different strategies applied at the course level.

This violin plot displays the distribution of precision scores across five different strategies used at the course level: Human-made, Hungarian, Greedy, Threshold, Hungarian with threshold. Each violin illustrates the density of precision values, with wider sections indicating higher concentrations of data points. Central markers represent the median or mean precision for each strategy. The visualization enables comparison of both performance and consistency, highlighting which strategies yield more reliable precision outcomes.Figure 8: Distribution of recall values across five different strategies applied at the course level.

This violin plot presents the distribution of recall scores for five different strategies applied at the course level: Human-made, Hungarian, Greedy, Threshold, and Hungarian with threshold. Each violin illustrates the density of recall values, with wider sections indicating higher concentrations of data points. Central markers represent the median or mean recall for each strategy.Results per professor

Table 5 summarizes the mean and standard deviation for each metric per professor. The results show that the threshold-based method and the Hungarian method and subsequent filtering with a threshold consistently achieve high accuracy for most courses and professors, while Greedy and human-made assignments have lower accuracy and higher variability. Figure 9 shows the distributions of the F1-scores. Figure 10 shows the distribution of accuracy and Fig. 11 is the graphical representation of the recall measures.

| Precision | Recall | F1-score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strategy | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| Human-made | 0.0152 | 0.0870 | 0.0061 | 0.0348 | 0.0087 | 0.0497 |

| Hungarian | 0.8286 | 0.3824 | 0.2989 | 0.2400 | 0.4145 | 0.2628 |

| Greedy | 0.7000 | 0.4570 | 0.2217 | 0.1777 | 0.3278 | 0.2441 |

| Threshold | 0.7000 | 0.4661 | 0.2797 | 0.2169 | 0.3907 | 0.2857 |

| Hungarian+threshold | 0.9667 | 0.1826 | 0.3487 | 0.2226 | 0.4836 | 0.2154 |

Figure 9: Distribution of F1-scores across five different strategies applied at the professor level.

The violin plot illustrates the distribution of F1-scores across five different strategies applied at the professor level: Human-made, Hungarian, Greedy, Threshold, and Hungarian with threshold. Each violin displays the density of the scores, highlighting both central tendency and variability. The plot allows for visual comparison of performance consistency and effectiveness among strategies.Figure 10: Distribution of precision scores across five different strategies applied at the professor level.

This violin plot displays the distribution of precision scores across five different strategies used at the course level: Human-made, Hungarian, Greedy, Threshold, and Hungarian with threshold. Each violin illustrates the density of precision values, with wider sections indicating higher concentrations of data points. Central markers represent the median or mean precision for each strategy. The visualization enables comparison of both performance and consistency, highlighting which strategies yield more reliable precision outcomes.Figure 11: Distribution of recall score across five different strategies applied at the course level.

The violin plot illustrates the distribution of recall scores across five different strategies applied at the course level: Human-made, Hungarian, Greedy, Threshold, and Hungarian with threshold. Each violin displays the density of the scores, highlighting both central tendency and variability. The plot allows for visual comparison of performance consistency and effectiveness among strategies.Kruskal-Wallis tests confirmed statistically significant differences between strategies for all metrics, both at the course and level (p < 0.001). Dunn’s post hoc tests also show that the threshold-based strategies and the hybrid Hungarian+threshold strategy achieve significantly higher scores than the greedy and human-made assignments (p < 0.001). Suggesting that the observed improvements are maintained across the entire data set and are not limited to aggregate averages.

The proposed course assignment model

Based on NLP techniques, the proposed course assignment model integrates semantic similarity based on embeddings with faculty preferences and significantly improves human-made assignments. Specifically, the strategy combining the Hungarian algorithm with a similarity threshold (0.65) and preference weighting achieved a precision of 1.0000 and an F1-score of 0.4296, compared to the 0.0227 precision and 0.0133 F1-score obtained from human-made assignments. These results confirm the effectiveness of the proposed model and underscore its potential to enhance teaching load distribution in higher education institutions.

It is worth noting that the historical assignment strategy was evaluated based on data from a single academic term rather than aggregating multiple periods. This decision was made to ensure temporal fairness in the comparison with the model-generated strategies, which produce course assignments for one term at a time. Including historical assignments from multiple periods would have artificially inflated the recall and F1-score metrics due to the increased probability that at least one historical assignment aligns with a professor’s stated preferences. Consequently, the relatively low precision (0.0227) and F1-score (0.0133) observed for the historical strategy reflect a more equitable and rigorous evaluation scenario.

Assignment comparison with weighted and unweighted preference

A comparative analysis was conducted using two model versions to evaluate whether incorporating faculty preferences into the similarity-based assignment model improves the quality of course assignments. One version was based solely on semantic similarity, and another combined semantic similarity with weighted faculty preferences. Both models were run under identical conditions, without applying a similarity threshold, to isolate the effect of preference integration. Table 6 compares the assignment regarding precision, recall, and F1-score.

| Metric | Unweighted | Weighted | Absolute improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precision | 0.2000 | 0.8286 | +0.6286 |

| Recall | 0.0660 | 0.2736 | +0.2076 |

| F1-score | 0.0993 | 0.4113 | +0.3120 |

The results provide clear empirical support for the claim that integrating faculty preferences into the course assignment model would improve performance. Compared to the baseline model based solely on semantic similarity, the preference-weighted model achieved significantly higher scores in all evaluation metrics: precision increased from 0.20 to 0.83, recall increased from 0.066 to 0.27, and F1-score increased from 0.099 to 0.41.

Discussion

The comparison of topic modeling methods showed that BERTopic generated the most semantically coherent topics, as evidenced by its higher NPMI and Cv scores. This finding reinforces the value of embedding-based approaches over classical probabilistic models such as LDA or hybrid models like Top2Vec, particularly in educational contexts where textual data is often short and heterogeneous.

The non-parametric statistical analysis provides strong evidence for the effectiveness of semantic and preference-aware assignment strategies. The Kruskal–Wallis H-tests revealed statistically significant differences among the evaluated methods across all three metrics: precision, recall, and F1-score. Pairwise comparisons using Dunn’s test with Bonferroni correction further showed that both the threshold-based and the Hungarian+threshold strategies consistently outperformed the historical and greedy approaches, particularly in terms of precision and F1-score. These differences were statistically significant, with p-values well below the 0.05 threshold, suggesting that the observed improvements are unlikely to be due to chance. The superior performance of threshold-integrated strategies indicates that incorporating a similarity threshold into assignment algorithms enhances accuracy and enables more targeted and institutionally viable decisions.

Among the assignment strategies, the Hungarian algorithm combined with a 0.65 similarity threshold achieved the best performance, yielding perfect precision (1.0000) and an F1-score of 0.4296. This approach aligns with professor preferences while ensuring one-to-one course–professor assignments, thereby meeting common institutional requirements for workload balance and teaching distribution.

Although the threshold-only method (a simple approach that assigns courses to professors using a fixed similarity threshold) also achieved perfect precision, it presented practical limitations by allowing multiple courses to be assigned to the same professor. This could result in workload imbalances, particularly in contexts where teaching capacity is strictly regulated. In contrast, the Hungarian-based strategy preserves balance while simultaneously optimizing for both semantic and preferential alignment.

While computationally efficient, the greedy method exhibited lower precision and F1-score. The algorithm prioritizes local optimization, focusing on immediate, short-term matches rather than long-term outcomes, and it fails to account for global assignment constraints that govern the entire process. Therefore, although it may be suitable for real-time or large-scale scenarios with limited resources, its use can compromise the overall quality of course allocation.

Furthermore, cosine similarity as the core semantic metric effectively quantified the compatibility between courses and professors. When combined with a preference weighting scheme (70% semantic similarity, 30% professor preference), the model demonstrated greater adaptability and personalization compared with purely administrative approaches.

The results of this study highlight the potential of incorporating NLP techniques into the course-to-professor assignment process. The proposed model—an innovative integration of semantic similarity and explicit professor preferences—significantly outperformed traditional human-made assignments and heuristic algorithms.

The comparison between unweighted and weighted assignment results indicates that incorporating explicit professor preferences substantially improves all three evaluation metrics, producing more accurate and targeted matches between faculty and courses.

Regarding the integration of faculty preferences into the evaluation framework, this study does not treat professors’ preferences as the sole criterion for course assignment or as the main weighting factor. Instead, they are combined with academic profile attributes such as training, teaching experience, and research publications. The model evaluates these characteristics across multiple dimensions, balancing faculty preferences with other criteria to determine the alignment between each course and professor.

Professors’ preferences were incorporated in the validation phase as a binary reference against the model’s results. This approach aligns with evaluation practices in knowledge-based and hybrid recommendation systems, where user preferences serve as a valuable benchmark when no universal objective metric is available (Adomavicius & Tuzhilin, 2005; Bobadilla et al., 2013; Burke, 2002).

Allowing professors to freely choose the courses they wish to teach is theoretically feasible; however, conflicts arise when multiple professors select the same course. In such cases, administrative solutions based on seniority (Algethami & Laesanklang, 2021) or academic rank (Domenech & Lusa, 2016), are often applied, though these criteria do not always reflect a professor’s training or relevance to the course. The proposed model offers a data-driven alternative that incorporates NLP techniques and professors’ preferences to resolve these conflicts, promoting greater consistency and fairness.

The model’s design reflects the constraints of academic management, where decision-makers must balance professors’ preferences with institutional needs—a task that is particularly challenging to accomplish manually when managing large numbers of courses and professors.

Strengths and weaknesses of assignment strategies

To guide future research and practical adoption, it is important to highlight the strengths and limitations of each evaluated assignment method.

The Hungarian algorithm generates an optimal overall assignment based on an inverted similarity score matrix, ensuring that each professor is assigned a course and that the distribution is equitable. However, it can generate assignments with low similarity.

Greedy algorithm: a high-speed and straightforward method, computationally convenient when working with large volumes of data. However, it can generate low-similarity, suboptimal assignments because it calculates local solutions per course rather than considering the overall context, where all courses must be taken into account.

Threshold-based assignments: This method is the simplest to implement and therefore also the fastest. Once the course-professor similarity has been calculated, it filters out assignments greater than the threshold value, resulting in perfect accuracy. On the other hand, it can create an overload for professors who teach several courses with high similarity.

Hungarian algorithm + threshold: combines the advantages of the Hungarian algorithm and the threshold method. This results in a balanced distribution with high accuracy. However, courses that are not assigned due to low similarity must be assigned manually or through an alternative strategy. Even so, it is an excellent option for implementation in real-world systems under institutional constraints.

Human assignments reflect one of the real-world assignment practices, guided by institutional policies and the knowledge of the person executing the process. It is very flexible and adapts quickly to institutional changes. Its disadvantage is that the decision-maker’s experience conditions it and may not be objective, resulting in suboptimal assignments. It also requires a significant amount of time to perform.

Conclusions

Based on NLP techniques, the proposed course assignment model integrates semantic similarity based on embeddings with faculty preferences and significantly improves human-made assignments.

This study addressed optimizing course-to-professor assignments by integrating NLP techniques with semantic similarity based on embeddings with faculty preferences. Unlike traditional assignment processes based solely on administrative criteria and availability, the proposed model incorporates semantic similarity and explicit professor preferences, operationalized through BERTopic, multi-qa-mpnet-base-dot-v1 embeddings, and cosine similarity. Course assignments were optimized using the Hungarian algorithm, further enhanced by a similarity threshold filter 0.65.

This research shows that the NLP-based method significantly outperformed human-made assignments. Among the three assignment strategies evaluated—Greedy, similarity-threshold-only, and Hungarian—the hybrid approach (Hungarian algorithm + threshold) yielded the best performance, achieving 100% precision, compared to 0.0217% for human-made assignments and 71.43% for the Greedy method. These findings support the hypothesis that incorporating semantic analysis into assignment processes can outperform human-made assignments regarding precision and F1-score.

Limitations

-

1.

The benchmarking data used was from a single academic period, to ensure temporal equity between historical and model-generated assignments and to avoid recall inflation. This decision may limit the generalizability of the results across different academic periods with variable subjects or where content has been updated.

-

2.

The accuracy of the model depends on high values of semantic similarity to recommend valid assignments. In cases where no Professor reaches a score above the threshold, the model may not assign the course, leaving gaps that require manual intervention or alternative strategies.

-

3.

The model does not explicitly consider operational constraints such as academic load limits. Similarity and preferences guide the allocation, yet the model needs to be integrated into a broader system to make institutional policies feasible.

-

4.

Although the model uses NPMI to assess the semantic relationship between the course and the professor, no qualitative assessments by human experts were incorporated to assess the relevance of the assignments. Assignments may be technically correct, but not aligned with the professor’s academic growth interests.

-

5.

It is assumed that the texts used are in the same language. Texts with errors and multilingual data may impact lemmatization and, consequently, embeddings. Future implementations should incorporate processes to detect and normalize the language automatically.