DC-TSCM: an interpretable dual-channel traditional Chinese medicine syndrome classification model via semantic-structural fusion

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Nicole Nogoy

- Subject Areas

- Artificial Intelligence, Data Mining and Machine Learning, Data Science, Natural Language and Speech, Neural Networks

- Keywords

- Traditional Chinese medicine, Syndrome classification, Dual-channel model, Hybrid graph neural networks, Deep learning, Natural language processing

- Copyright

- © 2026 Tang and Song

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2026. DC-TSCM: an interpretable dual-channel traditional Chinese medicine syndrome classification model via semantic-structural fusion. PeerJ Computer Science 12:e3555 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3555

Abstract

Background

With the widespread adoption of electronic medical records, massive prescription data can be digitized and systematically stored. This provides a solid foundation for intelligent traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) diagnosis systems. TCM syndrome classification is the core of syndrome differentiation and treatment. Developing an effective classification framework remains a major challenge for intelligent diagnosis systems. Recent progress in natural language processing has introduced new approaches and tools for semantic understanding and knowledge extraction from prescription texts. However, traditional machine learning methods rely on hand-crafted features and struggle to process high-dimensional, sparse, and intricate TCM prescription texts. The single text-based model can capture semantic features but ignore the structural connections in prescription data. The single graph-based model emphasizes structural associations but fails to incorporate rich contextual semantics.

Methods

To address the challenges, we propose a new dual-channel TCM syndrome classification model (DC-TSCM) in healthcare applications. The text channel extracts deep representations from clinical description and physique detection texts. We developed a TCM differentiation-guided attention fusion module to dynamically learn the optimal weighting between prescription texts. The graph channel constructs a unique TCM differentiation heterogeneous graph and uses hybrid graph neural networks to model the complex semantic associations among clinical entities. Additionally, we extracted 8,280 prescriptions from real electronic medical records, covering 24 different syndrome types. The prescription data were standardized according to clinical diagnostic terminology and divided into training, validation, and test sets in an 8:1:1 ratio.

Results

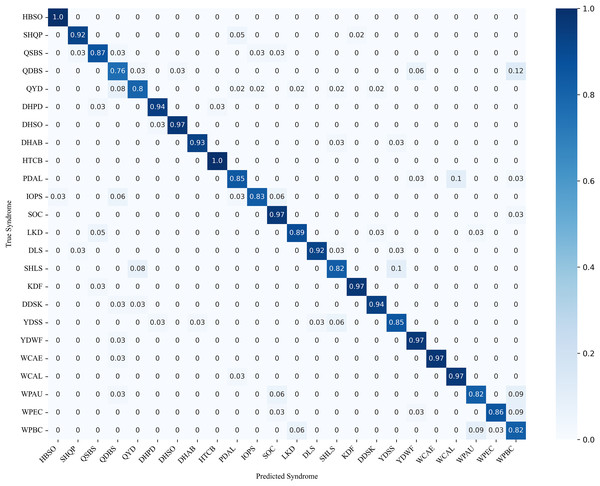

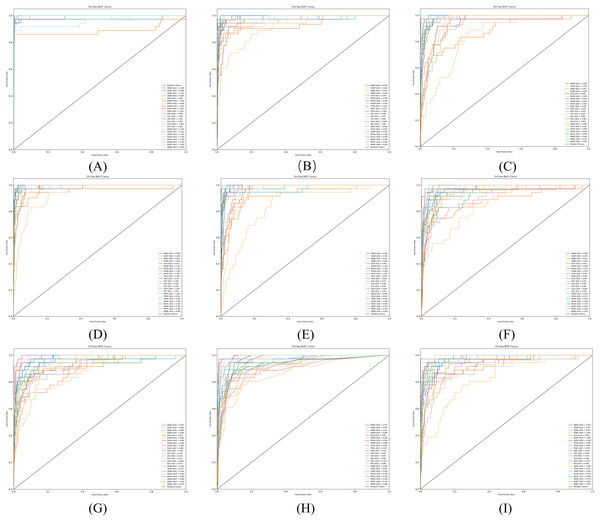

Experiments were conducted on a structured multi-label syndrome differentiation dataset. The results indicate that the model achieves superior performance and strong generalization ability in multi-class syndrome classification. Its interpretability is further validated through visualization analysis, including the co-occurrence relationship heat map, confusion matrix, and receiver operating characteristic curve. The dual-channel model achieved an accuracy of 0.8919, precision of 0.9012, recall of 0.8947, and F1-score of 0.8930.

Conclusion

Overall, DC-TSCM bridges semantic understanding with structural reasoning and incorporates the principles of TCM differentiation. It significantly improves the accuracy of syndrome differentiation and suggests potential applicability beyond TCM, which could be explored in future work. It also provides a robust and interpretable framework for intelligent auxiliary diagnosis systems and lays a foundation for the integration of clinical knowledge with advanced deep learning methodologies.

Introduction

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) has been practiced for thousands of years and is rooted in syndrome differentiation, which is the cornerstone of its diagnostic and therapeutic framework. Syndrome differentiation is different from the conventional diagnostic methods used in orthodox medical practice (Jiang et al., 2012). It is a process of comprehensive analysis of clinical information obtained from the four main diagnostic methods of TCM: observation, auscultation, inquiry, and pulse feeling. TCM syndrome is a clinical phenotype that reflects the nature of pathological changes in a disease at a specific stage. It can identify the overall state of the human body and provide guidance for subsequent TCM treatment (Chen & Wang, 2012; Ji et al., 2016). In addition, TCM views the human body as an integrated system embodying profound traditional Chinese philosophical wisdom. Its primary goal is to regulate the ecological balance of the human body, rather than simply treating a single organ (Ma et al., 2022). Consequently, identifying the patient’s syndrome based on symptoms, physical examinations and other factors is the biggest challenge for TCM clinicians and TCM-assisted diagnosis artificial intelligence (AI). With the rapid development of AI, research on applying natural language processing (NLP) to TCM has grown rapidly. Hui et al. (2020) employed a model combining Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT), a bidirectional long short-term memory (BiLSTM) network, and an attention mechanism to extract and categorize valuable clinical information from TCM medical records, addressing a core challenge in case-based TCM research. However, the large data volume and subjectivity introduced inaccuracies in the categorization process. Liu et al. (2022) proposed a two-stage transfer learning model TCMBERT, which generates Chinese medicine prescriptions from a small number of cases and literature, but the approach relies on complex external knowledge mining techniques, increasing data processing complexity. In order to further explore the intrinsic rules of herb compatibility, Cheng et al. (2021) developed a deep learning model, S-TextBLCNN, which consists of a BiLSTM network and a convolutional neural network (CNN) for prescription efficacy classification, thereby promoting the compatibility and efficacy exploration of TCM formulas. Nevertheless, the model ignores the influence of formula dosage on efficacy prediction. AI-driven auxiliary diagnostic systems for TCM have also made significant progress. Wu, Liu & Chang (2011) designed a TCM diagnosis expert system using latent class models and disease pattern coding system (B-code), which performed well in identifying systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Since the four diagnostic methods of TCM rely on the practitioner’s practical experience and are subjective, Wu et al. (2021) introduced an adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (ANFIS) to diagnose TCM-related sleep disorders. Both models are limited to assisting diagnosis for specific diseases rather than providing a general framework for syndrome differentiation.

In contemporary research on TCM syndrome classification, graph-based methods are increasingly being used to model the complex relationships between TCM elements. Teng et al. (2023) proposed the Symptom–State Graph Convolutional Network (SSGCN). By constructing a prescription graph with symptoms as nodes and pathogenesis elements as edges, the model captures potential relationships and effectively improves syndrome classification accuracy. Building on their earlier work on SSGCN, Teng et al. (2024) further proposed the SEHGCN, which introduces a state element induction mechanism and uses a hypergraph convolutional network to capture high-order semantic relationships between TCM entities. Yet both models do not incorporate graph attention mechanisms, limiting their capacity to learn the relative importance of different nodes and relationships. To address the complex one-to-many relationships between symptoms and syndrome elements, Zhang, Yang & Hu (2024) proposed Multi-Label Syndrome Classification model based on Graph Attention Networks (ML-SCGAN), a multi-label syndrome classification model. The model integrates BERT for feature extraction and a graph attention network (GAT) to capture relational dependencies, achieving significant improvements over baseline methods. Despite this progress, the model still faces challenges such as TCM label redundancy and data sparsity. Zhang et al. (2025) developed Knowledge Graph Syndrome Differentiation Network (KGSD-Net), a knowledge graph–driven framework designed to address the challenges of incomplete data and inconsistent analytical frameworks in TCM syndrome differentiation. KGSD-Net integrates large-scale language models (LLMs), the DeepWalk algorithm, and BERT to construct a dynamic TCM knowledge graph. This framework reveals latent diagnostic patterns and enables more accurate, knowledge-informed clinical decision-making in complex diagnostic contexts. Although graph-based methods can effectively represent the structural relationships among TCM entities, they often overlook the rich semantic and contextual information embedded in textual prescriptions. Therefore, text-based models play an essential role in capturing the linguistic and contextual nuances contained in clinical records.

In recent years, many scholars have explored various text-based models for syndrome classification. To reflect TCM’s holistic diagnostic philosophy, Chen et al. (2024) introduced TCM-BERT-CNN. It incorporates an overall-syndrome perspective to advance TCM syndrome classification. Within syndrome content, disease cause and location are essential premises for syndrome differentiation. Accordingly, Li et al. (2024) combined the first-order logic TCM diagnostic knowledge based on the cause and location of the disease with a deep neural network. It achieved better performance than the traditional syndrome differentiation model. TCM syndrome information is changeable, ambiguous, and complex. “Syndrome” denotes a holistic diagnostic model consisting of a group of interrelated symptoms. It reflects the pathological state of the body and serves as the basis for TCM clinical treatment (Wang et al., 2020). Conventional syndrome-classification models typically rely on a single textual input or on simple feature concatenation, and their simple architectures often fail to capture the latent interactions between clinical description and physique detection. Other models rely on modeling of prior knowledge and are difficult to cope with the diversity of TCM syndrome data. To enable models to process complex Chinese medical data, Li et al. (2023) proposed a dual-channel medical text classification that combines complex convolution and Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Unit (BiGRU). One channel applies convolutions of different sizes to obtain local text representations, while the other channel uses BiGRU and attention mechanism to extract global information. Although this model is structurally innovative, it does not incorporate the latent patterns and rules within medical texts. Building on the concept of dual-channel architecture, Liu et al. (2025) proposed a CNN-BiLSTM Dual-Channel Knowledge Attention model (DCKA). This model incorporates a novel attention mechanism that facilitates the learning of syndrome pattern knowledge. Its dual-channel structure processes long text (medical history and four-diagnostic information) and short text (chief complaint) in prescription data respectively, capturing key information and global context for more accurate syndrome classification. Although, DCKA can capture multi-perspective features from text data, TCM prescription data is a typical unstructured text. Using text-text dual-channel to extract long and short text features cannot fully process the multi-granularity information between different levels (e.g., symptom elements, medical history, and syndromes) in prescription data. In addition, the text-text model cannot explicitly capture the non-Euclidean relationship between TCM entities. The co-occurrence pattern between symptoms and the dependency relationship between syndromes are difficult to model in the text channel.

Existing TCM syndrome classification methods typically rely on either text-based or graph-based models, each facing inherent limitations when handling complex prescription data. Single text-based models capture rich linguistic semantics but overlook the relational structures among symptoms, syndromes, and cases. Conversely, single graph-based models effectively encode structural dependencies yet struggle to represent the deep contextual meanings embedded in clinical narratives. This semantic–structural gap highlights the necessity of a dual-channel model that jointly captures semantic and structural information. To overcome the limitations of the single text-based and the single graph-based models in processing complex prescription texts, we propose a novel text-heterogeneous graph dual-channel TCM syndrome classification model (DC-TSCM). In the text channel, we employ BERT to derive the contextual semantic embeddings from clinical description and physique detection, respectively. It integrates a TextCNN-BiLSTM layer to capture the local N-gram semantic features and reinforce feature dependencies, thereby mitigating BERT’s limitations in extracting fine-grained local representations. For the two-way TCM text, we proposed a TCM differentiation-guided attention fusion module (TDAF) to facilitate bidirectional information exchange. TDAF can dynamically learn the relative importance weights between clinical description and physique detection, addressing the variability in weight allocation across different prescription records. Recognizing the abundant latent associations among entities in prescriptions, the graph channel first converts TCM prescription entities into Case, Syndrome, and Symptom nodes. It then defines multiple edge types based on co-occurrence statistics to construct a unique TCM differentiation heterogeneous graph. Guided by the TCM principle of holism and locality, we employ GAT for fine-grained modeling of local heterogeneous structures and key symptom nodes. Graph sample and aggregated (GraphSAGE) captures structural commonalities among distant nodes to enhance global representation learning. This dual-graph strategy compensates for the limitations of a single graph neural network (GNN) structure and improves the model’s generalizability in modeling TCM structural relationships.

Our main contributions are as follows:

In the field of TCM-assisted differentiation, a text-heterogeneous graph dual-channel model that integrates TCM holistic and local theories is innovatively proposed. It solves the limitations of using single text-based models and single graph-based models in capturing the characteristics of prescription texts.

Different prescription data have different information focuses, making it necessary to consider weight allocation when extracting features. We propose a fusion module TDAF that combines the TCM “observation, auscultation, inquiry, and pulse feeling” syndrome differentiation principle. It simulates the information weight allocation process of different diagnostic methods in TCM diagnosis and realizes the modeling of the importance of information from different sources.

We construct a unique TCM differentiation heterogeneous graph, composed of case, symptom, and syndrome nodes. According to the principles of local and holistic differentiation, a hybrid GNN is used to capture the complex and multi-dimensional structural semantic relationships between symptom elements, syndromes, and medical history. It effectively integrates TCM diagnostic principles into the model.

Based on the clinical syndrome classification datasets we collected, we conduct comprehensive comparative experiments and ablation experiments. DC-TSCM outperforms state-of-the-art syndrome classification models across all evaluation metrics.

Methods

Data collection and preprocessing

The dataset employed in this study is derived from the TCM-Syndrome Differentiation (SD) corpus (Ren et al., 2022), the first publicly available high-quality resource for TCM syndrome differentiation. It comprises 54,152 authentic TCM clinical records. To ensure the quality of the dataset, we cleaned the data, removed duplicate entries, and retained only prescriptions with both complete clinical description and physique detection data. In addition, we standardized syndrome names and four diagnostic information according to the WHO international standard terminologies on traditional Chinese medicine and Clinic terminology of traditional Chinese medical diagnosis and treatment (State Administration for Market Regulation & Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China, 2021). For example, semantically similar expressions such as “mental fatigue,” “lassitude,” and “low spirit” were unified into “mental fatigue”, achieving semantic alignment and improving feature interpretability and reproducibility. On this basis, we identified 24 high-frequency and representative syndrome types, covering patterns according to the eight principles (yang, yin, heat, cold, excess, deficiency, exterior, interior pattern) and patterns of the zang–fu organs and meridians (heart system, lung system, spleen system, liver system, kidney system, multiple zang-fu organs patterns, meridian and collateral patterns).

To address the large variation in sample sizes across syndrome categories, we employed a random up-sampling and down-sampling strategy to balance the dataset. It controlled the number of samples in each class to approximately 320 ± 50. This adjustment not only mitigated bias caused by class imbalance but also ensured the clinical representativeness and diversity of the dataset. Detailed dataset statistics are presented in Table 1. Each prescription record contains a set of clinical description, a set of physique detection, a set of chief complaint, and an associated TCM syndrome. The chief complaint content is only used to construct nodes in the heterogeneous graph. Physique detection data usually consists of multiple independent symptom elements. We divided the physique detection content into multiple TCM symptom elements to enable the graph structure to capture the potential associations among different elements. An example physique detection entry reads: “clear mind, fair spirit, moderate form, clear speech, red lips; normal skin, no blotchy rash …… no swelling of both lower limbs, red tongue, white moss, slippery pulse”. Using regular-expression filtering and TCM symptom dictionary matching, we identified 988 distinct symptom elements (e.g., “tongue red”, “deep pulse”, “poor appetite”). These elements form the basis for the subsequent heterogeneous graph construction. However, this rule-based approach enabled efficient symptom extraction, it had limited adaptability to diverse clinical expressions.

| Syndrome | Abbreviation | Num of prescriptions | Num of symptom elements | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart blood stasis obstruction | HBSO | 356 | 64 | |

| Stagnated healthy qi and pathogenic factors | SHQP | 358 | 48 | |

| Qi stagnation and blood stasis | QSBS | 349 | 56 | |

| Qi deficiency with blood stasis | QDBS | 352 | 81 | |

| Qi and yin deficiency | QYD | 341 | 79 | |

| Dampness and heat pouring downwards | DHPD | 347 | 31 | |

| Dampness and heat stagnation and obstruction | DHSO | 341 | 41 | |

| Dampness and heat accumulation and binding | DHAB | 352 | 55 | |

| Heat toxin congestion and binding | HTCB | 350 | 26 | |

| Phlegm and dampness accumulating in the lung | PDAL | 345 | 50 | |

| Impediment and obstruction of phlegm and stasis | IOPS | 360 | 65 | |

| Stasis obstructing collaterals | SOC | 280 | 61 | |

| Liver and kidney depletion | LKD | 343 | 50 | |

| Disharmony of liver and stomach | DLS | 348 | 40 | |

| Stagnant heat in the liver and stomach | SHLS | 342 | 44 | |

| Kidney deficiency | KDF | 349 | 46 | |

| Dual deficiency of spleen and kidney | DDSK | 342 | 71 | |

| Yang deficiency in spleen and stomach | YDSS | 358 | 41 | |

| Yang deficiency with water flooding | YDWF | 358 | 69 | |

| Wind and cold attacking the external | WCAE | 352 | 54 | |

| Wind and cold attacking the lung | WCAL | 348 | 53 | |

| Wind and phlegm attacking the upper | WPAU | 349 | 64 | |

| Wind and phlegm entering collaterals | WPEC | 305 | 49 | |

| Wind and phlegm blocking collaterals | WPBC | 355 | 64 | |

Problem definition

TCM syndrome classification is typically defined as a long-text classification task. Its goal is to identify the TCM syndrome category corresponding to the patient given a set of clinical description and physique detection. TCM syndrome differentiation dataset , where each prescription sample contains a clinical description text and a set of physique detection elements . The label is a specific TCM syndrome category, which is taken from the syndrome category set . The objective of this study is to design a classifier that maps an input prescription to its corresponding syndrome label . Its output is expressed as , where is the predicted syndrome category for prescription .

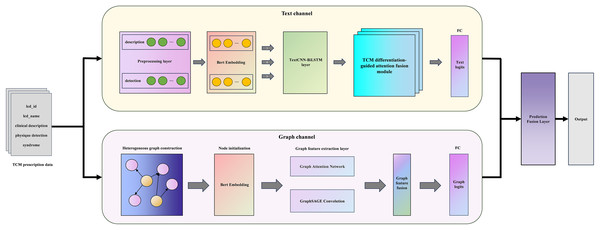

Dual-channel TCM syndrome classification model

The whole model is mainly composed of a sequence-based text channel and a structural graph channel, as illustrated in Fig. 1. Specifically, in the text channel, we use BERT-TextCNN-BiLSTM to obtain the deep semantics of prescription texts. TDAF is introduced to integrate the idea of TCM syndrome differentiation guidance into the model, which improves the interpretability of the model. In parallel, the graph channel constructs a unique TCM differentiation heterogeneous graph with initialized node features and leverages GAT-GraphSAGE to capture local neighbor attention and global distribution information. The following sections will describe the architecture of DC-TSCM and its module operation process in detail.

Figure 1: The overall frame of DC-TSCM.

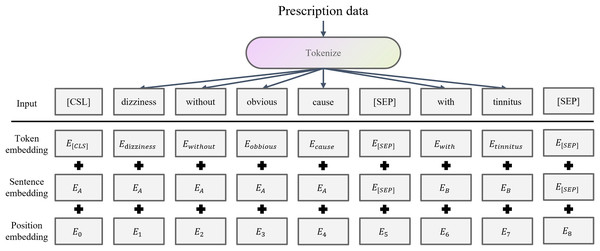

Word embedding module

The preprocessed prescription text sequences are fed into BERT (Devlin et al., 2019), which converts each word in the clinical description and physique detection texts into its corresponding word embedding vectors. It maps discrete symbols to continuous representations. BERT has been widely used in medical clinical applications by taking advantage of its bidirectional Transformer architecture and context-aware word embedding (Chaudhari et al., 2022; Mulyar, Uzuner & McInnes, 2021; Nishigaki et al., 2023; Rasmy et al., 2021). BERT word embedding is shown in the Fig. 2.

Figure 2: BERT word embedding structure.

For a TCM prescription, the clinical description sequence is and physique detection sequence is . Each sequence is encoded by BERT as follows:

(1) where is the hidden dimension, and are the actual lengths of the clinical description and physique detection inputs, respectively.

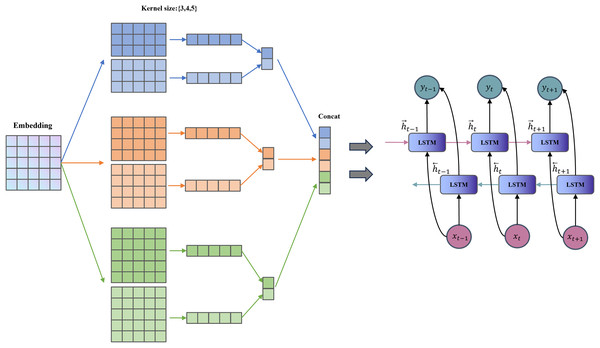

Semantic encoding module

TextCNN has a simple structure and few parameters (Chen, 2015). It uses convolution kernels to extract n-gram features within a fixed window, which is suitable for capturing keywords at the “symptom element” level in TCM texts (e.g., “red tongue with yellow fur” and “slippery pulse”). BiLSTM (Graves, Fernández & Schmidhuber, 2005) further captures the long-range dependencies and contextual features between words. It enhances the understanding of contextual semantics in symptoms, such as the implicit temporal and state-related associations between “dry mouth” and “restless sleep”. The combination of TextCNN and BiLSTM is complementary, allowing the model to not only recognize the local symptom vocabulary combinations but also pay attention to the overall semantic logic. It aligns with the comprehensive differentiation concept of TCM. The TextCNN-BiLSTM layer framework is shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Structure of the TextCNN-BiLSTM layer.

For each branch, we first apply a TextCNN to extract local features. To accommodate 1-D convolution, the two BERT output matrices are transposed:

(2)

For each channel and each convolution-kernel size , we perform the following operation:

(3) where is a symmetric or asymmetric padding operation calculated based on the size of the convolution kernel, ensuring that the output length is the same as the original sequence. is the number of output channels of each group of convolution kernels. Concatenate the convolution outputs of different sizes in the channel dimension:

(4)

Transpose the TextCNN output into sequence format for input to BiLSTM respectively:

(5)

The BiLSTM models long-range and contextual dependencies, producing:

(6) where is the number of hidden units in each unidirectional LSTM; the output dimension reflects the concatenation of forward and backward representations.

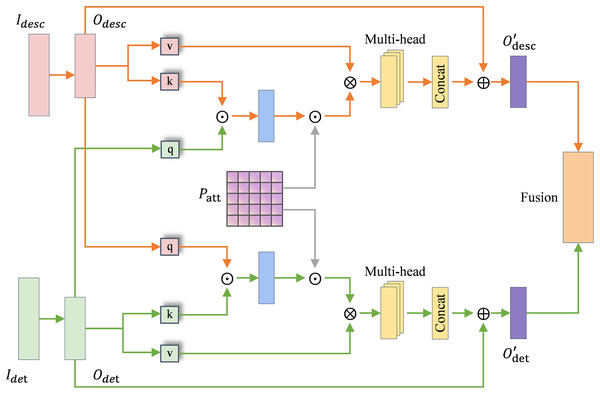

TDAF module

In TDAF, we first take the symptom set and the corresponding label syndrome for each case in the TCM differentiation heterogeneous graph. For each , the count is accumulated to the matrix , and the row is normalized to obtain the differentiation weight matrix . Therefore, the model can dynamically modulate the attention allocation between clinical description and physique detection features under the guidance of the differentiation weight matrix. It reflects the differentiated attention to diverse diagnostic information in the TCM diagnosis process. The differentiation weight matrix was constructed exclusively from the training set, and remained fixed during validation and testing to ensure consistent data partitioning.

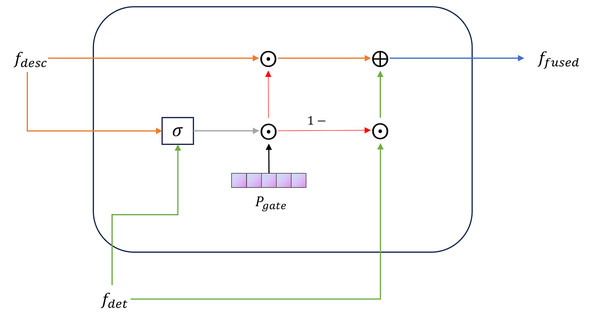

The attention module in TDAF is shown in Fig. 4, where the orange stream and green stream represent the clinical description and physique detection channels, respectively. and denote the raw input matrices of each channel. and represent the encoded feature embeddings obtained after semantic encoding module processing, which serve as the inputs to the TDAF attention module. The attention mechanism modulated by is formulated as:

(7) where and are linearly projected to obtain and , and denotes element-wise multiplication.

Figure 4: TCM differentiation-guided attention module.

The module performs two-way cross-attention between the clinical description and physique detection features. Specifically, the description features are refined under the guidance of detection information, and vice versa:

(8)

In each branch, multi-head attention is employed to capture diverse inter-feature dependencies, and the outputs of different heads are concatenated before residual fusion.

After the bidirectional refinement, global average pooling is applied to obtain the joint feature representation:

(9)

The basis gating vector is obtained through a linear transformation and sigmoid activation:

(10)

To incorporate prior differentiation knowledge from the co-occurrence matrix , we first aggregate the evidence of each syndrome category across all observed symptoms in the current case:

(11) and derive the “differentiation confidence” over the syndrome dimension via a softmax:

(12) where is the one-hot vector corresponding to the -th syndrome category and is the number of syndrome classes. Since resides in the label space , while the feature gate lies in the feature space , we introduce a learnable semantic projection to align the two spaces:

(13) where and are trainable parameters. Using the gated differentiation weight , we compute the final gating vector as:

(14) TDAF simulates the dynamic weight distribution of “observation, auscultation, inquiry, and pulse feeling” in TCM diagnosis, which improves the model’s fit and interpretability for TCM syndrome classification tasks. The final fused representation is as follows:

(15) The gated fusion module in TDAF is shown in Fig. 5. Finally, the fused vector is linearly projected and mapped to the syndrome-category space:

(16)

Figure 5: TCM differentiation-guided gate fusion module.

Heterogeneous graph construction

We transform TCM prescription data into a heterogeneous graph to represent the structured relationships between different clinical entities in TCM syndrome differentiation. Formally, the heterogeneous graph is denoted , where is the set of all nodes, and comprises all edge types. Each node has a -dimensional initial vector . The specific steps for constructing the heterogeneous graph are as follows:

Nodes: The TCM syndrome differentiation heterogeneous graph contains three types of entity nodes. Each node is initialized with BERT-based feature embeddings to encode its semantic representations:

Case nodes: Each clinical record is modeled as a case node, combining clinical description and chief complaint features. Their feature vectors are fused with a 0.2:0.8 weight ratio, emphasizing the main diagnostic cues in the chief complaint, and enriching them with supplementary symptom information from the clinical description.

Syndrome nodes: Each standardized syndrome label corresponds to a syndrome node, represented by a feature vector derived from its standardized text.

Symptom nodes: Each independent symptom extracted from the preprocessed physique detection text is represented as a symptom node.

Edges: Based on domain knowledge and statistical co-occurrence analysis, we define four types of directed edge relationships to connect these nodes:

Case-to-Syndrome edges: Connect each case node with its actual corresponding syndrome node, reflecting the direct diagnostic relationship between clinical cases and their identified syndromes.

Case-to-Symptom edges: Link each case node to all symptom elements extracted from its physique detection text, following the TCM principle that syndromes are inferred from observed symptoms.

Symptom-to-Syndrome edges: Established when a symptom element and a syndrome co-occur in at least five cases (threshold = 5). It effectively filters out random co-occurrences while retaining weak but clinically significant associations.

Case-to-Case edges: Self-loop connections are added to enhance the stability of message propagation during graph learning.

Graph feature extraction module

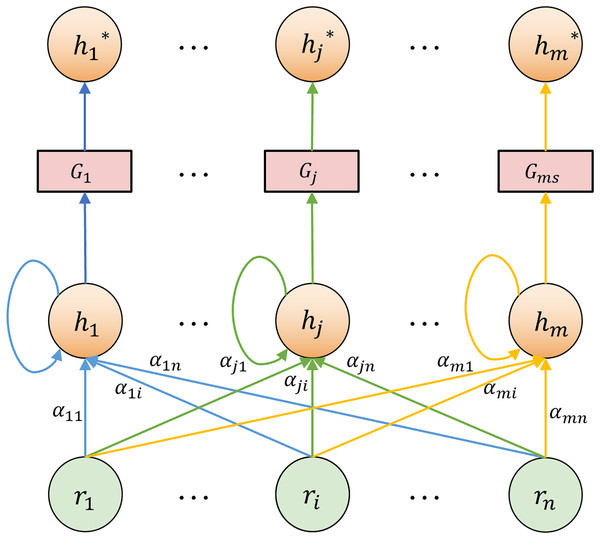

In the TCM differentiation heterogeneous graph, the nodes are diverse and the structure is characterized by hierarchical complexity and non-uniformity. It exhibits irregular connection patterns among nodes. The semantic significance of different nodes is also uneven. For instance, “white tongue coating” frequently appears across syndromes but contributes unequally to classification. Accordingly, within the graph feature extraction layer, we employ a hybrid GAT-GraphSAGE approach to extract both local and global structural features. GAT assigns different weights to neighboring nodes through the attention mechanism (Veličković et al., 2017). It is suitable for processing the local non-uniform contribution relationship between “cases-symptoms-syndromes” and improving the model’s sensitivity to typical symptoms. The node update process in GAT is shown in Fig. 6. The feature update of a node under edge type can be expressed as:

(17) where is the normalized attention coefficient, is a learnable weight matrix, and is typically a rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation. For each neighbor , the unnormalized attention score is computed by:

(18) where is the learnable attention vector, and || denotes vector concatenation. The normalized attention coefficient is then obtained using a softmax function:

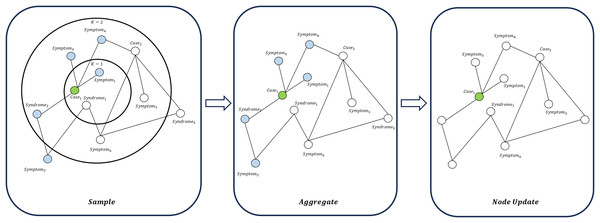

(19) GraphSAGE aggregates information using a neighbor sampling-based approach and is applicable to large-scale graph data (Hamilton, Ying & Leskovec, 2017), as illustrated in Fig. 7. GraphSAGE can better capture the macro-topological structure and potential global patterns between “cases-symptoms-syndromes”. The update of a node is expressed as:

(20) where represents the aggregation function, and are trainable parameters. The combined use of GAT and GraphSAGE allows the model to learn the strong representation ability of local key symptoms for syndromes. It also learns the overall connection and distribution rules between symptom elements, syndromes, and cases in the graph. This design is particularly suitable for dealing with the structure of “multiple symptoms corresponding to one medical history” and “multiple symptoms pointing to one syndrome” in TCM.

Figure 6: GAT node feature update diagram.

Figure 7: Node update flow in GraphSAGE.

Graph feature fusion module

In the graph feature fusion layer, we combine the outputs of GAT and GraphSAGE through a weighted sum:

(21) where controls the relative contribution of each branch. With , the attention mechanism of GAT and the robust aggregation ability of GraphSAGE can be simultaneously utilized. It allows the final fused node representation to not only reflect the importance of local key neighbors but also maintain the robustness of the global features.

A larger value causes the model to prioritize the GAT branch, improving its ability to capture sparse but critical clinical associations. This is common in cases with rare syndromes or those with few typical symptoms. In contrast, a smaller value enhances the influence of the GraphSAGE branch, making the model more stable and generalizable in scenarios with dense neighborhoods or overlapping symptoms. Since our dataset contains mostly high-frequency and symptom-overlapping syndromes, the graph fusion coefficient was set to 0.4 after multiple experiments.

The final node representation is fed into a fully connected layer, and the final output can be expressed as:

(22) where represents the graph channel’s standalone predictions for the case’s syndrome category.

Dual-channel fusion strategy

The outputs of the text and graph channels are integrated through a weighted summation:

(23) where controls the relative contribution of the two channels.

When channel integration factor approaches 1, the model relies primarily on the text channel. It is preferable for datasets where clinical descriptions are semantically rich but symptom relations are sparse or noisy. When approaches 0, the model emphasizes the graph channel. It is suitable for datasets with dense and reliable relational structures. In this case, graph-based aggregation helps the model capture implicit diagnostic patterns and suppress noise propagation. This flexible integration mechanism ensures that the advantages of both types of TCM prescription information are effectively utilized, thus enhancing the overall classification performance. Through extensive experiments, was set to 0.5, achieving a balanced trade-off between attention sensitivity and aggregation stability.

Finally, the fused logits are transformed into the probability distribution of each category:

(24) where denotes the total number of syndrome categories.

Results

Experimental settings

We screened 8,280 complete TCM prescription records from the TCM-SD database, covering 24 representative types of TCM syndromes. Each record contained two input modalities: clinical description and physique detection, and a syndrome label as the prediction target. The dataset was split into training, validation, and test sets in the ratio of 80%, 10% and 10%, respectively, with the proportion of each syndrome class kept nearly identical across the three subsets (variance <0.5%).

All experiments were carried out in a PyTorch 2.2 environment. The device was equipped with an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4060 Ti 8GB graphics card and 16 GB of system memory, and the model training was performed in the GPU environment. The model was implemented using the AdamW optimizer with an initial learning rate of 1e−5, optimized with the cross-entropy loss function. The batch size was set to 20. The network was trained for 50 epochs with early stopping (patience = 10) to prevent overfitting. The dropout rate was set to 0.4. Regarding the core network configuration, BERT served as the base encoder with a hidden size of 768. The TextCNN module adopted kernel sizes 3, 4, and 5. The BiLSTM layer contained 64 hidden units. The TDAF module was composed of 2 attention layers and four attention heads. The model’s hyperparameter and network parameter settings are detailed in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

| Component | Settings |

|---|---|

| Loss function | Cross-entropy loss |

| Optimizer | AdamW |

| Initial LR | 1e−5 |

| Batch size | 20 |

| Epochs | 50 |

| Early stopping | 10 |

| Dropout rate | 0.4 |

| Graph fusion coefficient | 0.4 |

| Channel integration factor | 0.5 |

| Module | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|

| BERT | Hidden size | 768 |

| TextCNN | Kernel sizes | {3, 4, 5} |

| Channels | 128 | |

| BiLSTM | Hidden units | 64 |

| TDAF | Attention layers | 2 |

| Attention heads | 4 | |

| GAT branch | Hidden size | 768 |

| Layers | 2 | |

| Attention heads | 4 | |

| GraphSAGE branch | Hidden size | 768 |

| Layers | 2 |

Evaluation metrics

In order to comprehensively measure the DC-TSCM in the multi-classification task of TCM syndrome, this study used precision, recall, F1-score and accuracy. All metrics were calculated on the test set and Macro-average was used. The metrics are defined as follows:

(25) where is the number of syndrome categories, is the total number of test set samples, denote the true-positive, true-negative, false-positive, and false-negative counts for class , respectively.

Additionally, this study used the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve to intuitively evaluate the classification ability of the model. The ROC curve plots the false positive rate (FPR) on the horizontal axis and the true positive rate (TPR) on the vertical axis. A ROC curve approaching the top-left corner (TPR = 1, FPR = 0) indicates superior classification performance, whereas a curve nearing the diagonal line (TPR = FPR) implies poorer performance. The area under curve (AUC) is widely used as a quantitative measure to evaluate the overall classification effectiveness of the model.

Comparative experiments

To evaluate the effectiveness of our model, we compared it with several relevant baselines and state-of-the-art approaches.

Support Vector Machine (SVM) (Cortes & Vapnik, 1995), Random Forest (RF) (Breiman, 2001), eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) (Chen & Guestrin, 2016) and K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) (Guo et al., 2003): These algorithms serve as classical baselines capable of handling structured and text-based features, offering interpretable yet limited nonlinear modeling capacity.

TextCNN and TextRCNN (Lai et al., 2015): TextCNN uses convolutional structures to effectively extract local semantic features from TCM prescription texts. TextRCNN combines recurrent and convolutional structures to capture long-term dependencies within clinical description.

BERT, MLM as correction BERT (MacBERT) (Cui et al., 2020), Zhong Yi BERT (ZY-BERT) (Ren et al., 2022) and Chief Complaint Syndrome Differentiation (CCSD) (Zhao et al., 2024): BERT serves as a foundational pre-trained language model for capturing contextual semantics from prescription texts. MacBERT is an enhanced Chinese BERT model that improves semantic representation through a masked correction pre-training objective. ZY-BERT is a BERT model pre-trained on the TCM-SD corpus for TCM-specific language understanding. CCSD enhances token-level and label-level attention on ZY-BERT to capture syndrome–symptom relationships and introduces focal loss.

TextGCN (Yao, Mao & Luo, 2019), GAT, GraphSAGE and Pre-trained Semantic Interaction-based Inductive Graph Neural Network (PaSIG) (Wang et al., 2025): TextGCN learns global word co-occurrence structures, making it suitable for capturing latent associations between symptoms and syndromes. GAT applies an attention mechanism to assign adaptive weights to nodes, effectively highlighting key symptom features in complex clinical relationships. GraphSAGE aggregates neighborhood information for inductive learning, capturing the macro-topological structure among TCM entities. PaSIG is an inductive GNN framework that constructs a text–word heterogeneous graph. It leverages an asymmetric structure, gated fusion, and subgraph propagation for efficient text classification.

The experimental results are summarised in Table 4.

| Category | Model | Accuracy | F1-score | Recall | Precision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional machine-learning models | SVM | 0.6498 | 0.6504 | 0.6476 | 0.6837 |

| RF | 0.6403 | 0.6378 | 0.6376 | 0.6485 | |

| XGBoost | 0.6368 | 0.6333 | 0.6353 | 0.6395 | |

| KNN | 0.6156 | 0.6079 | 0.6150 | 0.6122 | |

| Text classification models | TextCNN | 0.6958 | 0.6942 | 0.6946 | 0.7027 |

| TextRCNN | 0.7394 | 0.7365 | 0.7376 | 0.7466 | |

| CCSD | 0.8242 | 0.8238 | 0.8246 | 0.8324 | |

| BERT | 0.8019 | 0.8015 | 0.8026 | 0.8044 | |

| MacBERT | 0.8125 | 0.8096 | 0.8119 | 0.8211 | |

| ZY-BERT | 0.8201 | 0.8223 | 0.8216 | 0.8298 | |

| GNN-based models | TextGCN | 0.6969 | 0.6810 | 0.6940 | 0.7034 |

| GAT | 0.6899 | 0.6779 | 0.6851 | 0.6909 | |

| PaSIG | 0.8325 | 0.8323 | 0.8320 | 0.8348 | |

| GraphSAGE | 0.8202 | 0.8205 | 0.8198 | 0.8235 | |

| Ours | DC-TSCM | 0.8919** | 0.8930** | 0.8947** | 0.9012** |

Note:

Boldface values denote the best result for each metric. “*” indicates statistical significance compared with the best baseline model based on a two-tailed paired t-test at the 0.05 significance level, while “**” represents a higher level of significance at the 0.01 level.

Traditional machine learning models performed poorly overall, with precision generally below 70%. Because these methods rely on fixed, hand-crafted features, they struggle to fully capture the complex TCM symptom expressions in prescriptions.

In contrast, text classification models have significantly improved performance and effectively modeling the complex symptom interactions in clinical description and physique detection. Notably, ZY-BERT outperformed both BERT and MacBERT across all evaluation metrics, indicating that domain-specific pre-training on TCM corpora enhances the model’s semantic understanding of specialized terminology and syndrome expressions. Furthermore, CCSD model achieved the highest performance among text classification models (accuracy = 0.8242, F1 = 0.8238, recall = 0.8246, precision = 0.8324).

GNN-based models further enhance TCM knowledge representation by explicitly encoding the structural relationships among cases, symptom elements, and syndromes. PaSIG achieved the best performance within this category (83.25% accuracy, 83.23% F1-score, 83.20% recall, 83.48% precision), illustrating that incorporating pre-trained semantic interaction effectively strengthens representation learning in text-graph structures.

Our proposed DC-TSCM achieved the best overall performance across all evaluation metrics: accuracy (89.19%), F1-score (89.30%), recall (89.47%), and precision (90.13%). Compared with the current mainstream TCM syndrome classification model CCSD, DC-TSCM improved accuracy by approximately 6.77%. It also outperformed the best baseline model PaSIG by 5.94%. The double asterisks (**) following DC-TSCM metrics indicate statistically significant improvements over the best baseline model, as verified by a two-tailed paired t-test at the 0.01 significance level. These substantial gains can be attributed to the model’s dual-channel architecture, which integrates the differentiation principles of TCM diagnosis into its design. By jointly leveraging semantic representations from textual and graph modalities, DC-TSCM effectively captures contextual prescription semantics and structural relationships among TCM entities. It achieves more comprehensive and robust syndrome classification.

Ablation experiments

In this section, in order to clarify the role of each submodule and specific framework combination in DC-TSCM, we referenced prevalent TCM syndrome classification frameworks (Chen et al., 2024; Hu et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2025, 2020; Teng et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2022). We conducted ablation studies under identical data splits and hyperparameter settings, and designed nine variants:

Text-only: Completely remove the graph channel and keep only the text channel.

Graph-only: Completely remove the text channel and keep only the graph channel.

R-GAT: Keep the GraphSAGE branch but remove the GAT branch.

R-SAGE: Keep the GAT branch but remove the GraphSAGE branch.

R-GFL: Replace TDAF with feature concatenation followed by a fully connected layer.

TC-G: TextCNN-BiLSTM layer is changed to use only TextCNN.

LR-G: TextCNN-BiLSTM layer is changed to use LSTM-RCNN.

CBL-G: TextCNN-BiLSTM layer is changed to use CNN-BiLSTM.

T-MGCN: Graph feature extraction layer is changed to use only multi-graph neural network.

As shown in Table 5, text-only and graph-only achieved precision around 0.83, a modest gain over traditional baselines. The R-GAT and R-SAGE variants improved accuracy by approximately 4–5% relative to single-channel models but remain 1.6–1.7% below full DC-TSCM. This result confirms the complementary advantages of GAT in capturing local neighbor information and GraphSAGE in modeling global graph structure in graph channels. When TDAF is replaced by naive concatenation and a fully connected layer, accuracy declines to 0.8202. It underscores TDAF’s effectiveness in dynamically weighting clinical description and physique detection features in line with the TCM “observation, auscultation, inquiry, and pulse feeling” syndrome differentiation principle. Among text-channel variants, TCNN-G, LR-G, and CBL-G underperformed relative to DC-TSCM, further validating the superiority of the TextCNN-BiLSTM combination for capturing TCM textual logic. The T-MGCN variant, in which the graph feature extraction layer is replaced by a multi-graph convolutional network, also performed worse than DC-TSCM. It demonstrates that the combination of GAT and GraphSAGE better captures the complex and multidimensional semantics involved in TCM structural relationship modeling. Collectively, each submodule of DC-TSCM improves the ability to discriminate and generalize complex symptoms in TCM.

| Model | Accuracy | F1 | Recall | Precision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Text only | 0.8231 | 0.8203 | 0.8228 | 0.8291 |

| Graph only | 0.8340 | 0.8335 | 0.8315 | 0.8396 |

| R-GFL | 0.8202 | 0.8186 | 0.8196 | 0.8243 |

| R-GAT | 0.8724 | 0.8726 | 0.8742 | 0.8770 |

| R-SAGE | 0.8651 | 0.8662 | 0.8672 | 0.8710 |

| TC-G | 0.8663 | 0.8659 | 0.8677 | 0.8705 |

| LR-G | 0.8113 | 0.8117 | 0.8112 | 0.8236 |

| CBL-G | 0.8172 | 0.8134 | 0.8175 | 0.8187 |

| T-MGCN | 0.8196 | 0.8182 | 0.8190 | 0.8250 |

| DC-TSCM | 0.8919 | 0.8930 | 0.8947 | 0.9012 |

Note:

Boldface values denote the best result for each metric.

Visualization analysis

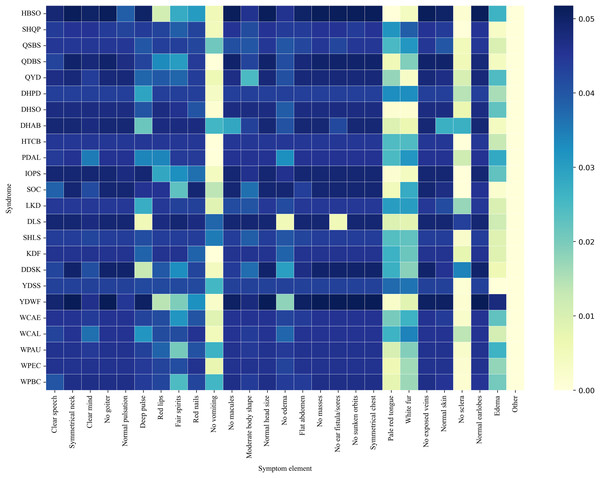

To further evaluate the classification ability of the DC-TSCM, we conducted a visual analysis of syndrome–symptom co-occurrence patterns, the syndrome multi-classification confusion matrix, and the ROC curves in different syndromes.

Figure 8 presents a co-occurrence heatmap illustrating the associations between syndromes and representative symptom elements. The color intensity reflects the degree of co-occurrence, with darker colors indicating higher frequencies. Notably, Yang deficiency with water flooding (YDWF) highly co-occurred with symptoms such as Edema and Deep pulse. Wind-cold attacking the external (WCAE) and wind-cold attacking the lung (WCAL) displayed strong associational patterns with white fur and pale red tongue. Another noticeable pattern was that the “No sclera” element exhibited a relatively high co-occurrence frequency with disharmony of liver and stomach (DLS), while showing very low or nearly zero co-occurrence with most other syndromes.

Figure 8: Syndrome-symptom co-occurrence heat-map.

Figure 9 illustrates the confusion matrix of syndrome classification, showing the predictive performance of DC-TSCM across different syndromes. Overall, the model achieved high predictive accuracy, with heart blood stasis obstruction (HBSO) and heat toxin congestion and binding (HTCB) exhibiting the highest correct-classification rates. However, it was also found that some syndromes such as qi deficiency with blood stasis (QDBS) were easily misclassified as wind and phlegm blocking collaterals (WPBC), with a probability of 12%. Phlegm and dampness accumulating in the lung (PDAL) also had a certain probability of being misclassified as wind and phlegm attacking the upper (WPAU). These results demonstrate that the proposed model effectively differentiates between most syndromes in the multi-class classification task.

Figure 9: TCM 24-class syndrome confusion matrix.

Figure 10 shows that the proposed DC-TSCM demonstrates outstanding discriminative performance on a 24-class TCM syndrome multi-classification task. The AUC ranges from 0.5 to 1.0, with higher values indicating superior classification performance of the model. In the Fig. 10A, QDBS had an AUC of 0.89, the lowest among all syndromes. WPBC achieved an AUC of 0.96, slightly lower than most categories. The ROC curves of the remaining 22 syndromes closely approached the top-left corner, with the highest AUC reached 1.00. Collectively, DC-TSCM exhibits robust discriminative capability, underscoring its robustness in multi-class syndrome classification tasks.

Figure 10: ROC curves of some commonly used syndrome differentiation models.

(A) The ROC curve of DC-TSCM; (B) the ROC curve of BERT; (C) the ROC curve of GAT; (D) the ROC curve of GraphSAGE; (E) the ROC curve of TextCNN; (F) the ROC curve of SVM; (G) the ROC curve of XGBoost; (H) the ROC curve of RF; (I) the ROC curve of TextRCNN.Discussion

This study proposes a text-heterogeneous graph model DC-TSCM that combines TCM theory. DC-TSCM addresses the limitations of single text-based models that are unable to model the structural relationship among TCM entities and single graph-based models that are unable to extract deep semantic features from prescription data. It effectively improves the accuracy of complex TCM syndrome classification. In comparative evaluations against diverse baselines, DC-TSCM has achieved significant advantages in accuracy, precision, recall and F1-score. Traditional machine learning methods (e.g., SVM, KNN) struggle with the high-dimensional, sparse nature of TCM prescription data, yielding relatively low performance. Although deep-learning–based text classifiers (e.g., TextCNN, ZY-BERT) capture rich semantic features, they lack explicit structural correlation among TCM entities, limiting their classification efficacy. In contrast, DC-TSCM uses graph neural networks in the graph channel to mine the structural association of symptom elements, syndromes, and cases. TDAF is used in the text channel, and by introducing the differentiation weight matrix and the gated differentiation weight, the model focuses on the important semantic interactions between clinical description and physique detection. It reflects the diagnostic logic of TCM “observation, auscultation, inquiry, and pulse feeling”. DC-TSCM overcomes the limitation that a single-path model cannot take into account both semantic details and global knowledge at the same time. Further ablation experiments verified the effectiveness of the model design from three levels: channel level, module level, and alternative structure. It is proved that the fusion of text semantics and structural information is the key to improving the performance of TCM syndrome classification. It is also shown that the combination of modules in the text channel and graph channels can play a better role in TCM syndrome classification.

Although our study offers several strengths, we also recognize certain limitations. Firstly, we used regular expressions and a TCM symptom dictionary for symptom extraction, which lack the flexibility and semantic depth of advanced NLP methods. Future work could incorporate specialized medical named entity recognition techniques. Secondly, our model was trained and evaluated solely on TCM syndrome differentiation data, and the dataset size is relatively small. Its applicability to other clinical domains remains to be verified. Future studies should test its generalization on broader medical datasets and expand the syndrome categories to enhance data diversity and representativeness.

In addition, future research should integrate broader theoretical frameworks of TCM, such as pattern differentiation by the eight principles, meridian attribution, and prescription knowledge (e.g., classical formula patterns and their modifications). These elements would enrich the semantic of clinical cases, enhancing the model’s interpretability and alignment with TCM clinical reasoning. Incorporating a knowledge graph could also provide a stronger foundation for intelligent diagnostic and recommendation systems.

Conclusions

This study introduces new perspectives into the research and application of TCM syndrome classification, and validates the effectiveness of the dual-channel strategy of text-heterogeneous graph. In future studies, more TCM knowledge bases and prescription data can be incorporated to continuously train and fine-tune the language model, further improving its predictive accuracy and applicability in clinical TCM practice. Simultaneously, this work contributes to the development of intelligent-assisted diagnosis and treatment, providing a viable path for intelligent diagnosis.