Enhancing scene graph generation via hybrid co-attention and predicate reweighting for long-tail robustness

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Ankit Vishnoi

- Subject Areas

- Artificial Intelligence, Computer Vision, Data Mining and Machine Learning, Multimedia, Neural Networks

- Keywords

- Scene graph generation, Hybrid co-attention, Predicate reweighting, Long-tail imbalance

- Copyright

- © 2026 Ling et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2026. Enhancing scene graph generation via hybrid co-attention and predicate reweighting for long-tail robustness. PeerJ Computer Science 12:e3548 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3548

Abstract

Scene Graph Generation (SGG) aims to extract visual entities and their semantic relationships from images, providing a structured layout for scene understanding. Current models often suffer from insufficient multi-modal feature fusion and imbalanced predicate distributions, leading to biased predictions. To address these issues, we propose ReBalance-HCA, a unified framework that combines Hybrid Co-Attention Networks (HCA) with Predicate Reweighting (PR). HCA enhances intra-modal features and aligns cross-modal semantics, while PR dynamically adjusts the predicate distribution by modeling inter-predicate correlations. Extensive experiments on the Visual Genome and OpenImages datasets demonstrate that ReBalance-HCA achieves competitive mR@K scores compared to recent state-of-the-art methods in SGG sub-tasks. Our code and datasets are available at: https://github.com/LinusLing/ReBalance-HCA.

Introduction

Image and text are two prominent modalities of information, omnipresent in our daily lives and business activities. To enhance people’s comprehension and utilization of information, aligning visual and textual modalities through structured representation learning has become a significant research focus in the field of artificial intelligence. Among these efforts, Scene Graph Generation (SGG) (Li et al., 2024; Hu, Yang & Zhao, 2025) emerges as a critical research direction. SGG aims to extract visual entities, such as objects and their attributes, from a given image and represent these two parts of information as a graphical structure. Its significance extends to various domains. For example, in image understanding (Wang et al., 2023), SGG elevates the semantic comprehension of complex scenes by analyzing objects and their relationships within images. In image description (Xu et al., 2017; Li et al., 2017; Phueaksri et al., 2023), SGG provides structured relational information to facilitate the generation of more detailed and accurate descriptions. In visual question answering (Tang et al., 2019; Shao et al., 2023; Ravi et al., 2023), SGG aids models in answering image-related questions more accurately by modeling the semantic relationships between entities.

In SGG, the goal extends beyond merely locating objects in an image to comprehending their connections. Most existing methods (Chen et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2024) involve two primary steps: entity detection and relationship prediction. During entity detection, object detection techniques identify and locate different object entities in the image and annotate their attributes and spatial information. Subsequently, relationship prediction analyzes the semantic relationships between entities, such as “a person holds a cell phone” or “a cat is on a chair”. However, Li et al. (2024) indicates that relationship prediction relying solely on visual features may overlook crucial semantic information present in text and context. For instance, it may misclassify “a person standing near a horse” as “a person riding a horse” due to the ambiguity of visual-only features. To address this issue, some studies (Ma et al., 2023) have adopted multi-modal feature fusion. For example, Duan et al. (2021) utilize directed graphs and heterogeneous message passing to model intra-modal relationships, implicitly achieving cross-modal semantic matching through graph structure similarity. Others employ explicit fusion strategies, such as aligning textual and visual features via attention mechanisms (Kundu & Aakur, 2023), directly modeling high-order cross-modal interactions through circulant matrix transformations (Wan et al., 2025), or storing and retrieving cross-modal alignment information using memory mechanisms (Huang & Wang, 2019). However, some methods that simply fuse different modalities through basic operations like addition or concatenation (Li et al., 2021) struggle to maintain coherent cross-modal representations, which ultimately limits the effectiveness of scene graph generation systems. Therefore, finding appropriate multi-modal fusion methods to effectively leverage the interactive information between textual and visual modalities remains a significant challenge.

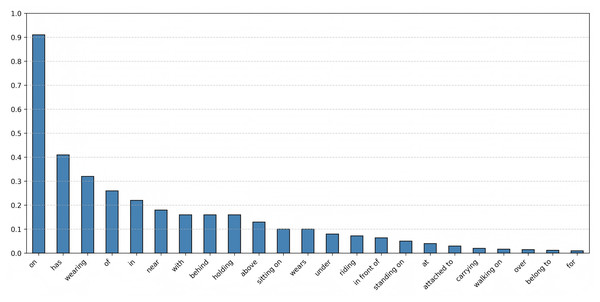

Another notable challenge for SGG is the imbalance of predicate distribution in the training data, particularly the long-tailed distribution of predicate categories. As shown in Fig. 1, a small number of head predicates (e.g., “on”, “has”) account for a large proportion of instances in the Visual Genome dataset. Consequently, this imbalance results in a lack of diversity and accuracy in the final predicate prediction results. Recent studies have attempted to address this problem. Previous research (Tang et al., 2020; Nag et al., 2023) introduces a causal inference-based debiasing method to extract counterfactual causal relationships from trained graphs. Although this approach can mitigate the impact of bad bias inference to some extent, it falls short in modeling contextual information (Sun et al., 2024). Other methods (Guo et al., 2021) address predicate imbalance by categorizing predicates into informative and common types based on information content and applying balancing adjustments rather than conventional distribution fitting. These methods focus on reducing bias in the predicate reasoning process by tackling the long-tail distribution of predicate categories. However, they overlook that the varying relevance between different predicates, resulting in a lack of adjustment for the imbalance in the distribution of predicate attributes.

Figure 1: Distribution of predicates in the visual genome dataset.

To address these limitations, we propose the ReBalance-HCA, a unified framework that combines Hybrid Co-Attention Networks (HCA) with Predicate Reweighting (PR). To obtain more comprehensive and accurate multi-modal representations, we introduce a HCA that hierarchically enhances intra-modal features through Intrinsic Feature Refinement (IFR) mechanisms and orchestrates cross-modal semantic alignment via Context-Guided Attention propagation (CGA). To alleviate the training bias of SGG model caused by long-tail distributions and rebalance the distribution in the unbalanced predicate space, we design a reweighting method that adjusts both the predicate category distribution and their inter-predicate relevance. In summary, the main contributions of this article are as follows:

We propose ReBalance-HCA, a unified two-stage framework for SGG. Our HCA, a key component of the framework, effectively enhances multi-modal representation learning.

To address the long-tail distribution issue, we introduce PR, an adaptive technique that systematically rebalances the predicate space. PR adaptively adjusts the distribution of predicate categories and their inter-predicate relevance, thereby reducing model bias and enhancing the semantic coherence of generated scene graphs.

We provide a comprehensive empirical evaluation on the Visual Genome and OpenImages datasets. The results validate that ReBalance-HCA effectively leverages intra-modal and cross-modal semantic attention to mitigate predicate distribution imbalance, achieving competitive performance against recent state-of-the-art methods in SGG tasks.

The rest of this article is organized as follows. ‘Related Work’ is related work, ‘Methods’ details the proposed framework, ‘Experiments’ presents numerical simulations and result analysis, and ‘Conclusion’ provides conclusions.

Related work

Scene graph generation

SGG has evolved along two primary architectural paradigms to bridge visual perception and semantic understanding, yet persistent challenges remain in cross-modal alignment and long-tail distribution handling. Single-stage methods, such as RelDN (Zhang et al., 2019), employ contrastive losses to mitigate entity confusion, while JMSGG (Xu et al., 2021) jointly models objects and relations by capturing their inter-dependencies. However, these methods may not effectively capture complex relationships between objects and relations, and their ability to handle cross-modal alignment is limited. Conversely, two-stage methods excel at hierarchical reasoning. For example, MotifNet (Zellers et al., 2018; Lu et al., 2021) and VCTree (Tang et al., 2019) establish classical sequence/tree-based context modeling, and RU-Net (Lin et al., 2022b) with unrolled optimization and HL-Net (Lin et al., 2022a) handle graph heterophily. But even these advanced methods have limitations. GPS-Net (Lin et al., 2020) utilizes message-passing mechanisms to facilitate information exchange between visual regions and textual predicates. However, this method suffers from a semantic granularity mismatch. The message-passing process may not effectively align the fine-grained semantic details of visual features with the more abstract textual predicates, resulting in suboptimal cross-modal alignment and limiting the accuracy of the generated scene graphs. BGNN (Li et al., 2021) adopts simple addition or concatenation operations for multi-modal feature fusion. This straightforward approach often results in incoherent representations as it fails to adequately capture the complex relationships and semantic interactions between different modalities. To address the issue of semantic ambiguity, Hiker-SGG (Zhang et al., 2024) employs a hierarchical attention mechanism to incorporate multi-scale knowledge. To further explore efficient architectures, Hydra-SGG (Chen et al., 2025) proposes a hybrid relation assignment mechanism within a one-stage framework. Furthermore, with the advent of large language models, recent work (Chen, Li & Wang, 2024) has begun to leverage role-playing large language models (LLMs) to refine scene graphs by utilizing the powerful commonsense knowledge embedded in pre-trained models. Despite these advances in architecture, the treatment of bias remains crucial. Recent efforts like Lyu et al. (2022) and Dong et al. (2022) address bias mitigation through fine-grained predicates learning and stacked hybrid-attention, respectively, while Zheng et al. (2023) achieves competitive performance via prototype-based embeddings, but they overlook the dynamic inter-predicate correlations crucial for long-tail robustness. These limitations highlight the need for a more sophisticated approach that can effectively address both cross-modal alignment and long-tail distribution issues. To tackle these challenges, we propose a unified framework to offer a more comprehensive solution.

Cross-modal attention mechanism

Recent advances in multimodal fusion (Bayoudh, 2024) and cross-attention modeling (Ren et al., 2024; Han et al., 2025) have garnered increasing interest across various vision-language tasks. As noted in Li et al. (2022b), the naive addition fusion used in current SGG methods (e.g., Motifs; Zellers et al., 2018) disproportionately amplifies high-frequency predicates, biasing predictions toward common relations. Notably, attention-based mechanisms like the Stacked Hybrid-Attention (SHA) network (Dong et al., 2022) have been applied to SGG, which combines Self-Attention (SA) and Cross-Attention (CA) units in parallel layers to enhance intra-modal refinement and inter-modal interaction. However, SHA’s parallel design processes SA and CA concurrently within each layer, which improves efficiency but lacks progressive alignment between modalities. This issue is further complicated by the inherent semantic gap between visual region of interest (ROI) features (typically extracted from Faster R-CNN; Zhao, Wei & Xu, 2024) and learned linguistic predicate embeddings. Additionally, few methods have adequately addressed the weak fusion between object proposals and their corresponding class names in SGG. To bridge this gap and overcome the limitations of existing cross-modal attention mechanisms, we propose the HCA to improve multi-modal representation learning and addressing the semantic granularity mismatches and weak fusion issues present in previous methods.

Long tail recognition

In real-world scenarios, the distributions of object and relation categories are inherently imbalanced, with natural data exhibiting a long-tail pattern (Zhang et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2021a; Zhao et al., 2024). Various methods have been proposed to address long-tail bias. TDE (Tang et al., 2020) employs counterfactual causality to address bias in scene graph generation. Although this method can mitigate the impact of spurious correlations to some extent, it has weak contextual modeling capabilities. It does not effectively account for the rich contextual information present in images and text, which is essential for accurately capturing the relationships between objects and their attributes. BA-SGG (Guo et al., 2021) categorizes predicates based on information content using Shannon entropy and splits them into common and informative groups for resampling. However, such resampling strategies have significant drawbacks. They are computationally inefficient when handling images with multiple object instances and lack the flexibility of re-weighting approaches. More importantly, these methods operate under the questionable assumption of a linear frequency-information correlation, thereby neglecting the context-dependent nature of predicate relationships, especially for tail categories where semantic meaning is often scene-specific. To address this, we propose the PR module. Unlike previous methods that treat all tail predicates uniformly, PR adaptively adjusts the weights of predicate categories and their inter-predicate relevance. This allows our model to better handle the long-tail distribution problem and improve the performance of scene graph generation by preserving the semantic coherence of the generated graphs.

Methods

Problem formulation

The scene graph generation task is essentially a multi-classification problem. To capture the relationships between objects and relations, we adopt a two-stage process (Li et al., 2017): first, detecting all objects within an image using an object detector like Faster region-based convolutional neural network (Faster R-CNN), and then identifying the relationship predicates between pairs of objects. Based on these relationships, we construct a scene graph composed of triplets (subject, predicate, object). Specifically, given an image X, Faster R-CNN is employed as the object detector to detect all objects . Next, for each subject-object pair , predict their visual relationship . So we can obtain the triplet for this pair of entities . For the image X, we use all triplets to construct the scene graph , where R represents the set of all possible predicate relationships for the subject-object pairs . For subject-object pairs with no identifiable relationship, the relation is designated as NA.

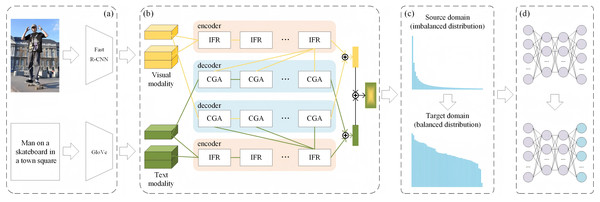

Framework overview

As illustrated in Fig. 2, the ReBalance-HCA framework comprises two key components: the HCA and the PR module. The framework’s pipeline is as follows:

-

1.

Feature extraction: Visual and textual features are extracted by Faster R-CNN (Zhao, Wei & Xu, 2024) and GloVe (Pennington, Socher & Manning, 2014), respectively.

-

2.

HCA: The HCA is the backbone of our framework for multi-modal feature fusion. It consists of two key components: Intrinsic Feature Refinement (IFR) and Context-Guided Attention propagation (CGA). The IFR is designed to refine features within each modality, capturing the intrinsic characteristics of visual and textual features respectively. The CGA, on the other hand, focuses on aligning cross-modal semantics, using information from one modality to influence the attention distribution of another. This dual-component structure enables the HCA to effectively capture both intra-modal and inter-modal relationships, producing more comprehensive and discriminative multi-modal representations.

-

3.

Predicate reweighting (PR) Module: After obtaining the fused multi-modal features from the HCA, the PR module dynamically adjusts the predicate category distribution. It takes into account both the empirical training data distribution and the inter-predicate semantic relevance, thereby generating a more balanced predicate space.

-

4.

Balanced fine-tuning: Finally, the initial SGG model, trained on the source domain with imbalanced predicate distribution, is fine-tuned on the balanced target domain produced by the PR module. This fine-tuning process, followed by Guo et al. (2021), focuses on the last layer of the network to maintain efficiency and prevent overfitting to head predicates.

Figure 2: The structure of the ReBalance-HCA framework.

(A) Feature extraction for image and text. (B) Hybrid co-attention network. (C) Predicate Reweighting for balanced distribution. (D) Fine tuning the last layer of the model.Hybrid co-attention network

The HCA is a critical component of our framework, responsible for multi-modal feature fusion. It is built upon an encoder-decoder architecture and consists of multiple stacked IFR and CGA layers.

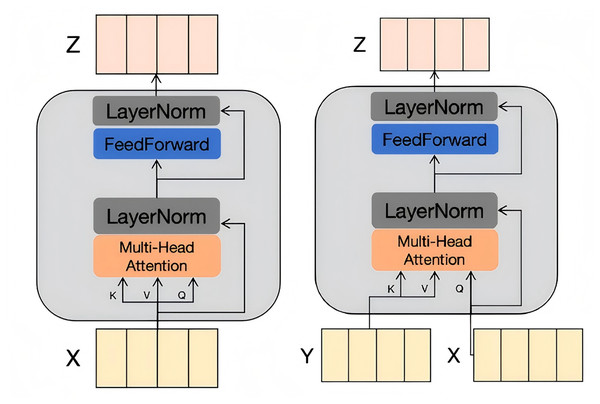

Intrinsic feature refinement

As shown in Fig. 3A, the IFR is designed to refine features within each individual modality. It encodes input vectors into query, key, and value vectors, which are then processed through a multi-head attention layer. Each attention head independently computes the attention scores, allowing the model to learn different correlation information in different representation spaces. It computed as

(1) where Q, K, and V represent the query vector, key vector, and value vector, respectively, and denotes the dimensionality of the vectors. The computation equation for each attention head can be expressed as

(2) where represents the learnable weight for the -th attention head. The last multi-head attention layer is composed of such attention heads, and its feature input denoted as:

(3)

Figure 3: The illustration of the IFR and CGA.

Next, the output of the multi-head attention layer is further refined through a feed-forward layer, followed by residual connections and layer normalization. This process results in a weighted feature representation Z, which better captures the intrinsic characteristics of the input features. The IFR enhances the model’s ability to understand and represent individual modalities, providing a solid foundation for subsequent cross-modal fusion.

Context-guided attention propagation

As shown in Fig. 3B, the CGA is specifically designed to enhance cross-modal semantic alignment. Unlike the IFR, which processes features from a single modality, the CGA takes features from different modalities as input. Specifically, assuming the task has two sets of input features, X and Y, from different modalities: for an attention layer’s input Q, K, and V, unlike the IFR setting where all three come from the same modality, the CGA replaces the K and V from modality X with those from modality Y. This design enables the attention weights of one modality to be influenced by the other modality, guiding the attention to focus on relevant elements. By doing so, the CGA effectively captures the interactions between different modalities, improving the model’s understanding of the relationships between visual and textual information. This is crucial for generating accurate and meaningful scene graphs.

The fusion in hybrid co-attention network

As shown in Fig. 2B, the HCA combines the IFR and CGA to achieve effective multi-modal feature fusion. For each modality, multiple IFR layers are stacked as the encoder to learn the intra-modality representations. The decoder then uses CGA layers, conditioned on the features from the other modality, to generate cross-modal representations. Specifically, given an individual modality X, we employ -stacked IFRs as the encoder to learn the intra-modality representations :

(4) where denotes the initial features and represents the final refined intra-modality features. The decoder utilizes CGAs conditioned on the other modality Y’s features to generate cross-modal representations :

(5)

The features obtained from the IFR and CGA are concatenated and processed through a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) for weighted fusion. Specifically, the weighted fusion of the modality-specific features is denoted as:

(6) where denotes the concatenation operation and is the feature dimension.

Finally, by concatenating and sending to MLP for cross-modal fusion, we obtain co-attention features F after text and vision are fused. F is denoted as:

(7)

This fusion mechanism allows the model to capture complex interactions between modalities, resulting in a unified representation that effectively leverages both intra-modal and cross-modal information. The fused features are then used as input to the PR module for further processing.

Predicate reweighting module

To mitigate the challenge posed by the long-tail distribution of predicate categories, we propose a Predicate Reweighting module that dynamically adapts the context-aware penalty adjustments in the loss function by leveraging semantic correlations among predicates. This module consists of two core components: (1) predicate semantic correlation, and (2) a correlation-based reweighted cross-entropy loss.

Predicate semantic correlation

To quantify the semantic relationships between predicates, we construct a predicate semantic correlation matrix based on valid relationship triplets in the training set. Specifically, for each predicate category , we collect all its valid triplets to form a set , where represents the number of valid instances for predicate .

Inspired by the subject-object affinity calculation in RelDN (Zhang et al., 2019), we define the semantic correlation coefficient between predicate categories and as:

(8) where denotes the set of valid triplets for predicate , and indicates that this triplet is invalid for predicate . Equation (8) essentially calculates the conditional probability that a given subject-object pair from also forms a valid triplet under predicate . The value of ranges between [0,1], with higher values indicating stronger semantic correlation between the two predicate categories.

Reweighted cross-entropy loss

The standard cross-entropy loss function tends to impose excessive penalties on tail categories when handling long-tail distributed data, leading to model bias. Given a prediction score vector , the corresponding probability distribution is computed through the softmax function: . The standard cross-entropy loss is:

(9) where is the ground-truth label (one-hot encoded) for category .

Equation (9) shows that for the true category , all negative categories are penalized. Under long-tail distribution, the instance count of head categories far exceeds that of tail categories, causing the prediction probabilities of tail categories to be consistently suppressed.

To address this issue, we introduce a correlation-based adjustment factor to dynamically modulate the penalty strength on negative category . The definition of incorporates both predicate category distribution and semantic correlation:

(10) where and represent the instance counts of categories and respectively, is a hyperparameter controlling adjustment strength, and is the semantic correlation threshold. When , the predicate pair is considered strongly correlated; otherwise, weakly correlated.

With the introduction of the adjustment factor, the reweighted cross-entropy loss function is defined as:

(11)

This reweighting mechanism dynamically adjusts the penalty strength based on the semantic correlation and frequency relationship between predicate pairs. Specifically, when predicates and are weakly correlated ( ) and is a tail category ( ), maintains the original penalty; if is a head category, enhances the penalty. Conversely, if they are strongly correlated ( ), the penalty on head negative categories is reduced ( ), while the penalty on tail negative categories remains unchanged. Through this mechanism, the model can maintain competitive relationships between strongly correlated predicates while alleviating bias caused by long-tail distribution.

Experiments

To verify the effectiveness of ReBalance-HCA, we conducted experiments on the widely used VG150 split of the Visual Genome dataset (Krishna et al., 2017) and OpenImages v6 datasets (Zhang et al., 2019). This section introduces the datasets, baselines, evaluation metrics, and implementation details. It then compares ReBalance-HCA’s performance with competitive methods and validates ReBalance-HCA’s effectiveness through ablation studies.

Datasets

Visual Genome. We conducted our experiments on the Visual Genome dataset, which comprises over 108,000 images and 2.3 million pairs of relationship instances. Similar to Lin et al. (2020), Tang et al. (2020), we experimented with the VG150 split, which is widely used in SGG and includes the 150 most frequently occurring object categories and 50 predicate relationship categories. Following the VG150 protocol, we split the dataset into 70% for training and 30% for testing. Additionally, we sampled a 5,000-image validation set from the training set, consistent with Zellers et al. (2018).

OpenImages v6. This large-scale dataset is designed for tasks like object detection and visual relationship detection, containing 126,368 images for training, 1,813 for validation, and 5,322 for testing. It includes 301 object classes and 31 predicate classes, with high-quality annotations.

Evaluation metrics

Visual Genome. Based on the prior works, we employed three tasks to comprehensively evaluate performance: (1) Predicate Classification (PredCls): Predicts relationships between all paired objects by utilizing given real bounding boxes and categories. (2) Scene Graph Classification (SGCls): Predicts the categories of objects and the paired relationships between them, utilizing given real object bounding boxes. (3) Scene Graph Detection (SGDet): Detects all objects in the image, predicting their bounding boxes, categories, and paired relationships.

Following recent works, we adopted the Mean Recall@K (mR@K) metric as the evaluation metric. This metric calculates the average recall for each predicate category, providing a fair evaluation method for SGG. Due to R@K’s bias toward head categories in imbalanced datasets (Wang et al., 2021b), we adopt mR@K. This metric computes recall per predicate category before averaging, ensuring fair evaluation of head and tail predicates. Higher mR@K indicates better performance. For each task, we bold the highest mR@K and underline the second.

OpenImages v6. Following the previous works (Zhang et al., 2019; Lin et al., 2022b; Zheng et al., 2023), we utilized the Recall@50 (R@50), weighted mean AP of relations ( ), weighted mean AP of phrase ( ) as the evaluation metrics. The final composite score, , is calculated as:

.

Implementation details

All experiments were conducted on Linux-based systems using one RTX 3090 with CUDA support. For the first-stage object detector, we maintain the same configuration as the baseline model, employing Faster R-CNN (Zhao, Wei & Xu, 2024) with ResNeXt-101-FPN backbone pre-trained on Tang et al. (2020).

Data Preprocessing. Training images undergo: (1) Color jittering (brightness/contrast/saturation/hue), (2) random horizontal flipping (50% probability), (3) configurable vertical flipping, (4) aspect ratio-preserving resizing. Evaluation uses resizing only. Semantic embeddings are extracted using GloVe (Pennington, Socher & Manning, 2014).

Training protocol. Initial SGG training uses SGD (lr = 0.001, batch size = 16) for all tasks (PredCls, SGCls, SGDet) with mixed precision, warmup scheduling, gradient clipping, and validation-based early stopping. Specifically, the model is trained for a total of 16,000 iterations. We employ a warmup scheduler: the learning rate starts from during the warmup phase and increases linearly to the base rate ( ). Subsequently, the learning rate is dynamically reduced by a factor of when the validation metric fails to improve for two consecutive validation checks (patience = 2), with a maximum of three reductions. Validation is performed every 2,000 iterations. Our HCA uses a four-layer encoder (four IFRs) and decoder (four CGAs). During target domain adaptation, only the last layer undergoes fine-tuning (Guo et al., 2021).

Reparameterization. Correlation threshold distinguishes strong/weak predicate-pairs, with reweighting intensity .

Results and analysis

As shown in Table 1, ReBalance-HCA outperforms competitive methods in mR@K across all tasks (PredCls, SGCls, SGDet) on the Visual Genome dataset. We attribute this to: (1) HCA achieves effective fusion of visual and textual features, and (2) PR can handle the issue of predicate distribution imbalance and accurately infer appropriate predicates. The results demonstrate that the proposed method consistently learns multimodal feature representations.

| PredCls | SGCls | SGDet | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | mR@20 | mR@50 | mR@100 | mR@20 | mR@50 | mR@100 | mR@20 | mR@50 | mR@100 |

| IMP+ (Xu et al., 2017) | 8.9 | 11.0 | 11.8 | 5.2 | 6.2 | 6.5 | 2.8 | 4.2 | 5.3 |

| MSDN (Li et al., 2017) | – | 15.9 | 17.5 | – | 9.3 | 9.7 | 6.1 | 7.2 | – |

| Motifs (Zellers et al., 2018) | 11.5 | 14.6 | 15.8 | 6.5 | 8.0 | 8.5 | 4.1 | 5.5 | 6.8 |

| RelDN (Zhang et al., 2019) | – | 15.8 | 17.2 | – | 9.3 | 9.6 | – | 6.0 | 7.3 |

| VCTree (Tang et al., 2019) | 12.4 | 15.4 | 16.6 | 6.3 | 7.5 | 8.0 | 4.9 | 6.6 | 7.7 |

| GPS-Net (Lin et al., 2020) | – | 15.2 | 16.6 | – | 8.5 | 9.1 | – | 6.7 | 8.6 |

| TDE (Tang et al., 2020) | 18.4 | 25.4 | 28.7 | 8.9 | 12.2 | 14.0 | 6.9 | 9.3 | 11.1 |

| Seq2Seq (Lu et al., 2021) | 21.3 | 26.1 | 30.5 | 11.9 | 14.7 | 16.2 | 7.5 | 9.6 | 12.1 |

| JMSGG (Xu et al., 2021) | – | 24.9 | 28.0 | – | 13.1 | 14.7 | – | 9.8 | 11.8 |

| BGNN (Li et al., 2021) | – | 30.4 | 32.9 | – | 14.3 | 16.5 | – | 10.7 | 12.6 |

| HL-Net (Lin et al., 2022a) | – | – | 22.8 | – | – | 13.5 | – | – | 9.2 |

| RU-Net (Lin et al., 2022b) | – | – | 24.2 | – | – | 14.6 | – | – | 10.8 |

| PPDL (Li et al., 2022b) | – | 33.0 | 36.2 | – | 20.2 | 22.0 | – | 12.2 | 14.4 |

| IS-GGT (Kundu & Aakur, 2023) | – | 26.4 | 31.9 | – | 15.8 | 18.9 | – | 9.1 | 11.3 |

| TEMPURA (Nag et al., 2023) | 19.7 | 31.2 | 32.8 | 13.3 | 20.3 | 21.5 | 8.7 | 13.7 | 15.6 |

| ERBNet (Ma et al., 2023) | 25.5 | 33.1 | 37.7 | 14.1 | 16.6 | 19.3 | 10.7 | 13.5 | 16.7 |

| SQUAT (Jung et al., 2023) | 25.6 | 30.9 | 33.4 | 14.4 | 17.5 | 18.8 | 10.6 | 14.1 | 16.5 |

| PE-Net (Zheng et al., 2023) | – | 31.5 | 33.8 | – | 17.8 | 18.9 | – | 12.4 | 14.5 |

| SKD (Sun et al., 2024) | 22.3 | 29.9 | 32.9 | 14.3 | 18.9 | 20.8 | 7.4 | 10.5 | 13.1 |

| ReBalance-HCA (Ours) | 29.1 | 37.1 | 41.3 | 16.1 | 20.7 | 22.7 | 11.6 | 16.2 | 18.7 |

To further validate the generalization capability of ReBalance-HCA, we extended our evaluation to the OpenImages v6 dataset. As shown in Table 2, ReBalance-HCA achieves a competitive weighted score ( ) of 44.9, matching the PE-Net, while excelling in key metrics such as (36.7) and R@50 (76.8). This performance highlights the method’s robustness in handling complex scenes and varied predicate distributions, which are characteristic of OpenImages v6. The consistency in results across datasets can be attributed to the HCA module’s ability to align cross-modal semantics effectively and the PR module’s dynamic adjustment of predicate correlations, which mitigate domain-specific biases.

| Model | R@50 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motifs (Zellers et al., 2018) | 71.6 | 29.9 | 31.6 | 38.9 |

| RelDN (Zhang et al., 2019) | 73.1 | 32.2 | 33.4 | 40.9 |

| VCTree (Tang et al., 2019) | 74.1 | 34.2 | 33.1 | 40.2 |

| GPS-Net (Lin et al., 2020) | 74.8 | 32.9 | 34.0 | 41.7 |

| BGNN (Li et al., 2021) | 75.0 | 33.5 | 34.2 | 42.1 |

| HL-Net (Lin et al., 2022a) | 76.5 | 35.1 | 34.7 | 43.2 |

| RU-Net (Lin et al., 2022b) | 76.9 | 35.4 | 34.9 | 43.5 |

| SQUAT (Jung et al., 2023) | 75.8 | 34.9 | 35.9 | 43.5 |

| PE-Net (Zheng et al., 2023) | 76.5 | 36.6 | 37.4 | 44.9 |

| ReBalance-HCA (Ours) | 76.8 | 36.7 | 37.1 | 44.9 |

Ablation study

In this section, ablation experiments were performed on the VG dataset for the ReBalance-HCA’s model to evaluate the effectiveness of HCA as well as PR in the model, and the results are shown in Table 3. We further evaluated RP by integrating it into several benchmark SGG models for comparison.

| Config | PredCls | SGCls | SGDet | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mR@20 | mR@50 | mR@100 | mR@20 | mR@50 | mR@100 | mR@20 | mR@50 | mR@100 | ||

| Baseline | Motifs | 11.5 | 14.6 | 15.8 | 6.5 | 8.0 | 8.5 | 4.1 | 5.5 | 6.8 |

| HCA Variants | IFR-only | 11.1 | 15.9 | 17.2 | 6.6 | 8.4 | 9.0 | 4.2 | 6.3 | 7.8 |

| CGA-only | 11.2 | 15.1 | 17.6 | 7.2 | 8.2 | 9.9 | 4.8 | 7.1 | 8.7 | |

| Full | 12.7 | 16.4 | 17.8 | 7.3 | 9.1 | 9.7 | 4.9 | 6.9 | 8.4 | |

| PR variants | 11.5 | 14.6 | 15.8 | 6.5 | 8.0 | 8.5 | 4.1 | 5.5 | 6.8 | |

| Full | 27.3 | 36.2 | 40.3 | 16.0 | 19.8 | 22.0 | 9.8 | 13.7 | 16.8 | |

| HCA+PR | Full | 29.1 | 37.1 | 41.3 | 16.1 | 20.7 | 22.7 | 11.6 | 16.2 | 18.7 |

Component ablation

As presented in Table 3, we highlight three key observations: First, in variants of HCA, the complete framework (IFR + CGA) achieves competitive performance, attaining a PredCls mR@100 score of 17.8, outperforming individual components (IFR-only: 17.2; CGA-only: 17.6). This underscores the necessity of cross-modal synergy. Second, activating the PR module ( ) yields a substantial performance gain of 24.5 points in PredCls mR@100 (increasing from 15.8 to 40.3), whereas its deactivated state ( ) matches the baseline exactly. This confirms that the reweighting mechanism is primarily responsible for performance gains in long-tail scenarios. Finally, the proposed framework (HCA + PR) achieves peak performance (41.3 PredCls mR@100), demonstrating strong complementary benefits between feature fusion and distribution alignment strategies.

Effectiveness of hybrid co-attention network

As shown in Table 3, integrating HCA leads to significant performance improvements. The IFR-only variant increases the baseline PredCls mR@100 by +1.4 points (17.2 vs 15.8), validating its effectiveness in intra-modal refinement. Meanwhile, the CGA-only variant demonstrates stronger cross-modal conditioning, achieving PredCls mR@100 = 17.6 (+1.8 over baseline). The full HCA model achieves optimal synergy with PredCls mR@100 = 17.8, highlighting HCA’s efficacy in multimodal feature fusion.

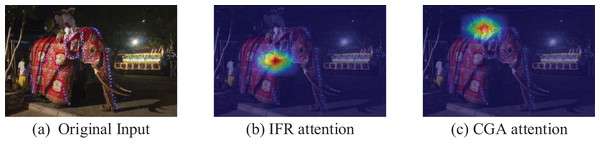

To qualitatively demonstrate how HCA improves cross-modal alignment, we visualize the attention evolution in Fig. 4. The heatmap focused on the decorated elephant (Fig. 4B) reflects the IFR mechanism, which distills features by enhancing salient regions (e.g., decorative patterns). Conversely, the attention shift to the rider–elephant interaction (Fig. 4C) illustrates the CGA mechanism, where semantics are grounded by linking phrases like “person riding elephant” to visual predicates (e.g., riding).

Figure 4: (A–C) Visualization of attention evolution in HCA modules.

Effectiveness of predicate reweighting module

As demonstrated in Table 3, the proposed PR module yields significant performance gains across three evaluation tasks. The PR Variants analysis reveals that disabling the reweighting mechanism ( ) produces identical results to the baseline, while activating full PR yields substantial gains. This improvement can be attributed to two key mechanisms: First, the module dynamically adjusts the loss weights for different predicate categories based on their information content and contextual importance, effectively rebalancing the distribution. Second, it preserves crucial semantic relationships for tail predicates while suppressing dominant head categories, enabling more robust feature learning.

Furthermore, to verify the effect of the PR module on model performance, we integrate it into several SGG benchmark models, Motifs and VCTree, for comparison. As shown in Table 4, our PR consistently improves performance across various SGG benchmark models, outperforming most competitive methods such as BPL (Guo et al., 2021), Inf (Biswas & Ji, 2023), and SKD (Sun et al., 2024). VCTree+Ours achieved the same optimal performance (9.9) as VCTree+BPL on the SGDet task’s mR@20 metric, while Motifs+Ours (9.8) achieved suboptimal performance at a slight disadvantage compared to Motifs+NICE (9.9). This confirms the effectiveness and superiority of our PR and also demonstrates the versatility of PR as a plug-in debiasing module.

| PredCls | SGCls | SGDet | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method | mR@20 | mR@50 | mR@100 | mR@20 | mR@50 | mR@100 | mR@20 | mR@50 | mR@100 |

| Motifs (Zellers et al., 2018) | 11.5 | 14.6 | 15.8 | 6.5 | 8.0 | 8.5 | 4.1 | 5.5 | 6.8 |

| + Debiasing (Cui et al., 2019) | 18.8 | 28.1 | 33.7 | 10.6 | 15.6 | 18.3 | 7.2 | 10.5 | 13.2 |

| + TDE (Tang et al., 2020) | 18.5 | 25.5 | 29.1 | 9.8 | 13.1 | 14.9 | 5.8 | 8.2 | 9.8 |

| + GCA (Knyazev et al., 2021) | 16.4 | 17.8 | 18.3 | 9.6 | 11.2 | 12.6 | 8.0 | 9.0 | 10.2 |

| + STL (Chiou et al., 2021) | 13.3 | 20.1 | 22.3 | 8.5 | 12.8 | 14.1 | 5.4 | 7.6 | 9.1 |

| + PCPL (Chiou et al., 2021) | 19.3 | 24.3 | 26.1 | 9.9 | 12.0 | 12.7 | 8.0 | 10.7 | 12.6 |

| + DLFE (Chiou et al., 2021) | 22.1 | 26.9 | 28.8 | 12.8 | 15.2 | 15.9 | 8.6 | 11.7 | 13.8 |

| + BPL (Guo et al., 2021) | 22.6 | 27.1 | 29.1 | 13.0 | 15.3 | 16.2 | 9.7 | 12.4 | 14.4 |

| + NICE (Li et al., 2022a) | 23.7 | 29.9 | 32.3 | 13.6 | 16.6 | 17.9 | 9.9 | 12.2 | 14.4 |

| + Inf (Biswas & Ji, 2023) | 15.7 | 24.7 | 30.7 | 10.2 | 14.5 | 17.4 | 6.6 | 9.4 | 11.7 |

| + SKD (Sun et al., 2024) | 22.3 | 29.4 | 32.5 | 12.2 | 15.8 | 17.2 | 7.4 | 10.5 | 13.1 |

| + PR (Ours) | 27.3 | 36.2 | 40.3 | 16.0 | 19.8 | 22.0 | 9.8 | 13.7 | 16.8 |

| VCTree (Tang et al., 2019) | 11.7 | 14.9 | 16.1 | 6.2 | 7.5 | 7.9 | 4.2 | 5.7 | 6.9 |

| + TDE (Tang et al., 2020) | 18.4 | 25.4 | 28.7 | 8.9 | 12.2 | 14.0 | 6.9 | 9.3 | 11.1 |

| + STL (Chiou et al., 2021) | 14.3 | 21.4 | 23.5 | 10.5 | 14.6 | 16.6 | 5.1 | 7.1 | 8.4 |

| + PCPL (Chiou et al., 2021) | 18.7 | 22.8 | 24.5 | 12.7 | 15.2 | 16.1 | 8.1 | 10.8 | 12.6 |

| + DLFE (Chiou et al., 2021) | 20.8 | 25.3 | 27.1 | 15.8 | 18.9 | 20.0 | 8.6 | 11.8 | 13.8 |

| + BPL (Guo et al., 2021) | 23.8 | 28.4 | 30.4 | 15.6 | 18.4 | 19.5 | 9.9 | 12.5 | 14.4 |

| + SKD (Sun et al., 2024) | 22.3 | 29.9 | 32.9 | 14.3 | 18.9 | 20.8 | 6.9 | 9.6 | 11.7 |

| + PR (Ours) | 27.6 | 36.3 | 40.3 | 15.7 | 20.1 | 22.3 | 9.9 | 13.6 | 16.3 |

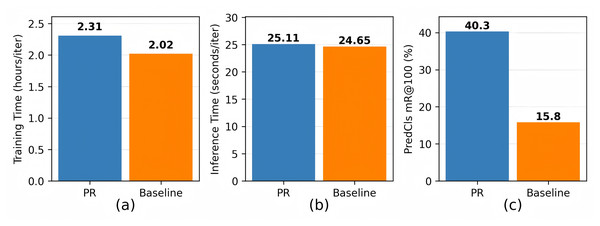

Moreover, we quantify the computational tradeoffs introduced by the PR module. As shown in Fig. 5A, the pairwise correlation computation between all predicate categories increases training time by 14.36% compared to the baseline. This overhead primarily stems from the operation of conditional power adjustments. Crucially, Fig. 5B demonstrates that during inference, where cached weights replace dynamic calculations, the cost remains negligible. Given the significant performance gains (Fig. 5C), the additional training overhead is considered acceptable.

Figure 5: (A–C) Time cost and performance between PR and baseline methods.

Visual analysis on long tail robustness

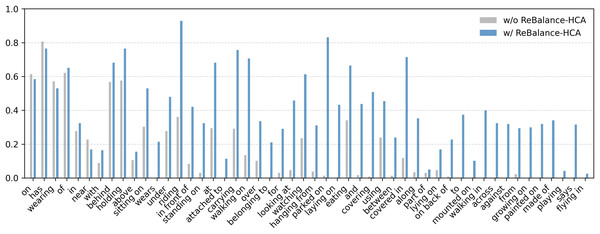

To illustrate intuitively the robustness of ReBalance-HCA on long tail predicates, we compare R@100 results on each predicate for Motifs with/without ReBalance-HCA. As shown in Fig. 6, he ReBalance-HCA gives a significant performance boost to almost all predicates (e.g.,“riding in,” “working on,” and “parked on”), especially those with long tails. The slight loss of head predicates, such as “on”, “has”, may be due to weight adjustments during reweighting; while the large number of long-tail predicates, such as “growing on”, “painted on” and “made of”, may be due to PR’s dynamic punishment of head-class and tail-class sample pairs according to strong and weak correlations during reweighting.

Figure 6: Visual comparison of predicate reweighting performance: Motifs with/without PR under PredCls task on VG-SGG (Sorted by Predicate Frequency).

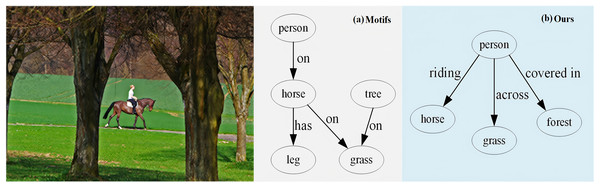

To better visually demonstrate the performance in robust rebalancing on long tail predicates, we present an example from the VG dataset. As shown in Fig. 7, compared to Motifs, our method is more accurate in predicates prediction, particularly for both: (1) common relations (e.g., ‘person-riding-horse’, ‘person-on-horse’), and (2) semantical long-tail predicates (e.g., ‘person-covered-in-forest’, ‘person-across-grass’). This performance improvement stems from the HCA, which refines cross-modal semantic alignment through its stacked fusion process. Furthermore, the PR enhances the model’s discriminative capacity for rare but semantically vital predicates (e.g., spatial relations like ‘across’ and ‘covered in’) while maintaining head category performance. This demonstrates the effectiveness of joint HCA and PR in addressing long-tail challenges for scene understanding.

Figure 7: Visualization results of (A) motifs and (B) our ReBalance-HCA on the visual genome dataset.

Hyperparameter sensitivity analysis

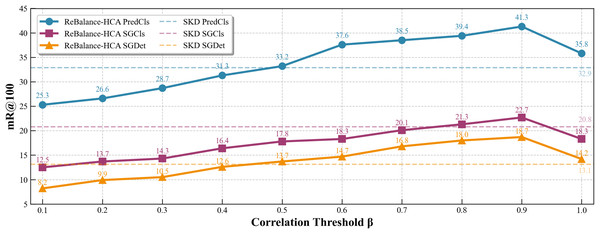

As illustrated in Fig. 8, we performed sensitivity experiments on the correlation threshold to evaluate its role in balancing head-tail predicate distributions. For fair and comprehensive comparison, SKD (Sun et al., 2024) was selected as the benchmark model. Defined in Eq. (10), determines the boundary between strong and weak inter-predicate correlations, directly influencing the adaptive reweighting mechanism. We varied from 0.1 to 1.0 in 0.1 increments and evaluated mR@100 performance across three SGG subtasks on the VG dataset. The performance reached its peak at , with the highest mR@100 scores (PredCls: 41.3, SGCls: 22.7, SGDet: 18.7). These results confirm ’s critical importance in robust long-tail reasoning and empirically validate our selection for balanced reweighting.

Figure 8: Impact of on model performance.

Conclusion

We introduce ReBalance-HCA, a framework that addresses two challenges in SGG: insufficient multi-modal feature fusion and imbalanced predicate distributions. Our framework combines a HCA with a PR mechanism. The HCA consists of IFR and CGA components, which work together to enhance intra-modal representations and achieve precise cross-modal semantic alignment. The PR mechanism dynamically adjusts the predicate distribution by modeling inter-predicate correlations, effectively reducing the long-tail bias in the predicate space. Extensive experiments on benchmark datasets such as Visual Genome and OpenImages demonstrate that ReBalance-HCA achieves competitive performance in three SGG subtasks. Despite its effectiveness, limitations remain. First, iterative refinement in HCA brings additional computational costs during training. Second, the current framework relies on established predicate distributions, which may struggle with entirely novel predicates or significant domain shifts. Therefore, future work will focus on optimizing computational efficiency and extending the framework to few-shot and cross-domain learning scenarios.