An Amharic sexually explicit content detection model using fine-tuned bidirectional encoder representation from transformers and explainable artificial intelligence

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Xiangjie Kong

- Subject Areas

- Artificial Intelligence, Data Mining and Machine Learning, Text Mining

- Keywords

- BERT, Fine-tuning, Sexually explicit content, Text classification, Transfer learning, XAI

- Copyright

- © 2026 Endalie

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2026. An Amharic sexually explicit content detection model using fine-tuned bidirectional encoder representation from transformers and explainable artificial intelligence. PeerJ Computer Science 12:e3529 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3529

Abstract

Nowadays, people are posting a significant amount of sexually explicit content on digital platforms and social media, particularly in under-resourced languages like Amharic. This rise in explicit content presents a significant challenge to the cultural and religious values of Ethiopia, which have traditionally emphasized humbleness and respect. To mitigate this growing issue, we present an Amharic sexually explicit content detection model. Our approach utilizes a fine-tuned Bidirectional Encoder Representation from Transformers (BERT) model that was initially trained to detect hate speech in Amharic. This is due to the lack of a large-scale Amharic dataset for training BERT from scratch and the shared linguistic characteristics between hate speech and sexually explicit content. We integrate this model with Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) techniques to enhance the transparency and interpretability of its predictions. The model was trained on a diverse, manually annotated dataset of 34,710 comments and posts (comprising 17,199 explicit and 17,511 non-explicit examples) collected from social media platforms such as TikTok, YouTube, Facebook, and X (formerly known as Twitter). Data instances were annotated based on the presence of explicit terms, sexually offensive words, sexual slang, and content highly susceptible to sexual interpretation. To understand the model’s decision-making process, we incorporated Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME) as our XAI framework. The experimental results demonstrate strong performance, yielding accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score values of 94%, 95%, 94%, and 94%, respectively. The XAI techniques employed reveal how the model classifies comments by computing probabilities for each category and highlighting significant words associated with them. Furthermore, we compare the performance of our proposed model with several state-of-the-art text classification techniques, including base BERT, support vector machines (SVM), multilayer perceptrons (MLP), and convolutional neural networks (CNN). The results indicate that our model consistently outperforms these existing methods.

Introduction

Nowadays, sexually explicit comments are widespread on digital platforms, including social media, forums, and messaging applications. The ease of access to online spaces has spread this content quickly, turning it into a global issue that crosses borders and cultures. Such behavior has sparked important conversations about regulation, responsibility, and the need for better digital literacy (Radanliev et al., 2024).

Sexually explicit comments are often characterized by improper, unrefined, or sexually suggestive language (Betts et al., 2018). Reducing the spread of sexually explicit content on social media is necessary to guarantee the safety and dignity of all users. However, the lack of effective models for detecting sexually explicit content in various languages impacts individuals, communities, and digital platforms (Mukred et al., 2024). If not properly filtered, this content has the potential to disrupt the traditional values and norms of a community, which are vital for peaceful coexistence.

While detection using Natural Language Processing (NLP) and machine learning has significantly advanced for well-resourced languages like English, Chinese, and Arabic, challenges persist for under-resourced languages (Supriyono & Suyono, 2024). Advanced deep learning models such as BERT, Generative Pre-trained Transformer (GPT), mbrets, and Cross-lingual Language Model (XLM-R) are readily available for this task in well-resourced languages (Zhang & Shafiq, 2024). However, building these models from scratch is challenging for under-resourced languages, which lack sufficient data and preprocessing tools. Therefore, for tasks such as explicit content detection, question answering, sentiment analysis, and hate speech detection in under-resourced languages like Amharic, transfer learning and fine-tuning emerge as the most viable strategies (Zhao et al., 2024). These methods leverage knowledge from models pre-trained on well-resourced languages, allowing for efficient adaptation to new tasks with significantly less data.

Amharic, a Semitic language mainly spoken in Ethiopia, serves as the country’s official working language (Asker et al., 2009). The Amharic language is spoken by more than 32 million people as their mother tongue and by over 25 million as a second language in the country (Belay et al., 2020). Most Amharic speakers reside in Ethiopia, and significant Amharic-speaking communities also exist in Eritrea, the USA, Israel, Sweden, Somalia, and Djibouti due to diaspora populations (Meshesha & Jawahar, 2007). Amharic is written using a script adapted from the ancient Ethiopian language known as Ge’ez, which is still used in the Ethiopian Orthodox Church (Girma, 2019). This script uses 34 consonant characters with the seven vowel variants of each (called basic characters). For example, the character for ‘h’ (ሀ) is systematically changed to represent hu (ሁ), hi (ሂ), ha (ሃ), he (ሄ), hə (ህ), and ho (ሆ).

Beyond its unique script, Amharic also exhibits complex morphological processes involving derivation and inflection, which are particularly evident in word classes like verbs, nouns, and adjectives (Yohannes et al., 2025; Abate & Assabie, 2014). Amharic verbs are normally formed in two stages from verbal roots: first, formation of the verbal stem, and second, addition of inflectional markers (Gewe & Gasser, 2012; Yeshambel, Mothe & Assabie, 2022). To illustrate, the Amharic verb “መጠነ” (met’ene), meaning “he measures/adjusts,” beautifully demonstrates its origin in the verbal stem “መጠን” (met’en), which denotes “amount/size.” This stem originates from the verbal root “ምጥን” (mtn), which means “measured/adjusted.” Through a combination of derivation and inflection, a verbal stem can be marked for various grammatical categories, including person, case, gender, number, tense, and negation. This process results in a highly complex morphological structure (Booij, 2006).

In addition to its morphological complexity, Amharic exhibits significant dialectal variation throughout Ethiopia, reflecting the country’s diverse ethnic and cultural landscape (Mengistu & Melesew, 2017). The most common dialects include Addis Ababa, Gojjam, Gonder, Wollo, and Shewa (Gebre, Firisa & Dash, 2024). The Addis Ababa dialect is the standard for education and media because it combines features of many Ethiopian dialects (Salawu & Aseres, 2015). Each of the other dialects, such as Gojjam, Gonder, Wollo, and Shewa, shows unique phonetic, lexical, meaning, and grammatical variations. For instance, the Amharic word “ክፈተኝ” (kifetenyi) has different meanings across dialects. In the Gondar dialect, it means “open to me,” whereas in the Gojjam dialect, it means “open me.” This illustrates how dialectal variations in Amharic create significant semantic and grammatical differences, accordingly increasing the complexity of text processing in the language.

Amharic’s complex morphology and dialects, along with the lack of essential NLP resources like processing tools, language models, and training datasets, pose challenges for NLP development (Endalie, 2025). As a result, no NLP models have been developed or integrated with social media platforms to filter out Amharic sexually explicit content from posts and comments. This increases the risk of sexual harassment for Amharic speakers on social media (Ababu, Woldeyohannis & Getaneh, 2025). However, cultural and religious norms in Ethiopia often restrict open discussions about sexually explicit contents (Baraki & Thupayagale-Tshweneagae, 2023). The presence of such content online in Amharic creates conflict between traditional Ethiopian values and global digital culture. Therefore, developing a sexually explicit content detection system is essential to address this problem.

However, creating such a detection model is also challenging due to the cultural variation found in Ethiopia (Endalie, Haile & Taye, 2023). Cultural variation means that a comment considered sexually explicit by one group may not hold the same connotation for another. For example, the phrase “እናትህን ልብዳ” (inatihini libida), which translates to “fuck your mother,” is a culturally sensitive expression with varying interpretations across regions. In Eastern Ethiopia, such as Dire Dawa, the phrase may be considered a normal part of casual discourse. However, in Northern Ethiopia, including Gojjam and Gonder, the same phrase can incite significant conflict or physical harm. Such cultural variations complicate the development of universal detection systems, necessitating a specialized and robust approach.

Despite these challenges, this research aims to develop a fine-tuned BERT + XAI model for detecting sexually explicit content in Amharic, building on a BERT model initially trained for hate speech detection. The absence of a comprehensive Amharic dataset for BERT training presented clear limitations, and hate speech and sexually explicit content often exhibit shared linguistic patterns, prompting us to adopt this approach. We assembled a diverse dataset of both sexually explicit and non-sexual comments from various social media platforms, creating a valuable resource for future research. To enhance transparency and build confidence, we integrate XAI into our detection model, which helps to illustrate the decision-making process’s reliability and trustworthiness. Finally, this research will play an important role in future studies and provide a deeper understanding of Amharic language processing.

The key contributions of this study are as follows: (1) We created a freely available dataset of Amharic sexually explicit and non-explicit comments gathered from social media. (2) We built a deep learning model for Amharic sexually explicit content detection by adapting a BERT model originally trained on hate speech and using XAI to understand its classification decisions.

In the remainder of this article, we will describe the following: First, the second section will review current models used to detect sexually explicit comments. Next, the third section will explain the methodology we employed in our study. Following that, the fourth section will present our experimental results and discuss their implications. Finally, the fifth section will conclude with some suggestions for future research.

Related works

The detection of sexually explicit content on social media platforms has become a major area of interest, with many studies focusing on natural language processing and machine learning techniques (Jahan & Oussalah, 2023). However, research on underrepresented languages, such as Amharic, remains limited. The following articles outline the methodologies used to detect inappropriate content across various languages. Each study explores different approaches, including machine learning algorithms and NLP techniques.

As discussed in Ababu, Woldeyohannis & Getaneh (2025), the authors proposed four deep-learning classifiers combined with three feature extraction techniques to detect hate speech in Amharic and Afaan Oromo. Their Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (Bi-LSTM) model, using FastText embeddings, achieved 78.05% accuracy in bilingual hate speech detection and handled out-of-vocabulary words effectively. Additionally, the study incorporated supplementary linguistic features to improve detection performance and support future research on under-resourced Ethiopian languages.

The study conducted by Hamzah & Dhannoon (2021) utilized deep learning techniques, specifically Bi-LSTM, to detect sexual harassment and cyber predators in English. In their approach, word representations were carefully analyzed and mapped to real-number vectors. Their proposed model for detecting online sexual predators achieved an F0.5 score of 0.927 and an accuracy of 97.27%. Additionally, the model demonstrated strong performance in identifying sexual harassment-related comments, attaining an F0.5 score of 0.925 and a remarkable accuracy of 99.12%.

The research in Akhter et al. (2021) focused on automatically detecting abusive language in Urdu and Roman Urdu comments, tackling the challenges of their complex morphology and the mixed-script format of Roman Urdu. The study employed a range of machine learning and deep learning models. The traditional algorithms include Naive Bayes, Support Vector Machine (SVM), and logistic regression. The deep neural networks are like Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), long short-term memories (LSTMs), and Bi-LSTMs. The datasets employed varied in size from two thousand to ten thousand comments. Notably, the CNN model achieved the highest accuracy, outperforming other methodologies and underscoring the effectiveness of deep learning techniques in this domain. Additionally, their findings indicated that single-layer deep learning architectures provided superior results compared to their multi-layered counterparts.

The authors of Saha et al. (2024) proposed a BERT-CNN model to detect hate speech and harassment in the Bengali language. This model integrates BERT with CNN to enhance performance. It was trained and evaluated using data collected from Bengali social media profiles. The BERT-CNN model outperformed baseline models, achieving notable results in detecting hate speech and fostering a more respectful online environment for Bengali language speakers.

The study by Islam et al. (2023) proposed machine learning and deep learning algorithms to detect and classify sexual harassment in Bangla text. The study achieved accuracy rates ranging from 65.2% to 76.5% using TF-IDF with various algorithms, including Naive Bayes, Decision Tree, Random Forest, AdaBoost, Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD), Logistic Regression, K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), and SVM. Deep learning algorithms like CNN, LSTM, and hybrid CNN-LSTM achieved an accuracy of 89%, making them comparatively better than machine learning techniques.

The work of Yenala et al. (2018) proposed a deep learning-based technique to detect and filter inappropriate language in online discussion forums and user conversations in English. The authors used a convolutional bidirectional LSTM architecture to find query suggestions and filter conversations that were not suitable. They did this by using LSTM and Bi-LSTM sequential models. The model outperforms hand-crafted feature-based baselines, enhancing user experiences and preventing abusive language in online discussions.

The study conducted by El-Alami, El Alaoui & En Nahnahi (2022) utilized a Multilingual Offensive Language Detection (MOLD) model that leverages transfer learning and fine-tuning techniques. This model employs BERT to effectively capture semantic and contextual information in offensive texts. It comprises three main components: preprocessing, text representation, and classification, enabling the detection of both offensive and non-offensive content. Experiments conducted on a bilingual dataset demonstrated that the translation-based method achieved an accuracy of over 93%, while the Arabic BERT model reached an accuracy of 91%.

Although various researchers have attempted to detect inappropriate content on social media platforms using machine learning and deep learning across different languages, it has been established that deep learning models are generally more effective in identifying such content. Integrating deep learning with XAI enhances model interpretability by revealing the features influencing each prediction. Moreover, research on inappropriate content detection in the Amharic language is limited, and sexually explicit content represents a significant concern in Ethiopia. Therefore, we propose a model for detecting sexually explicit content in Amharic using a transfer learning strategy, integrated with XAI to ensure that the model’s decisions are easily understandable and interpretable.

Materials and Methods

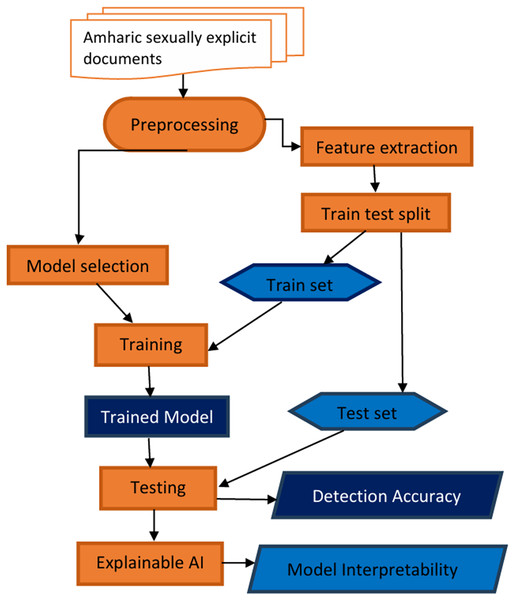

This section describes the materials and methods employed to create a model for detecting sexually explicit content in Amharic. The detection model utilized Explainable AI to illustrate its decision-making process for users. Figure 1 presents a flowchart that visually illustrates the systematic process of developing and evaluating the proposed model. The process begins with the collection of raw data, followed by several preprocessing steps. These steps encompass data cleaning, normalization, feature extraction, model training, and evaluation. This methodology progresses from initial data input to the final assessment of detection accuracy. Lastly, we incorporate the explainable AI component to improve our understanding of the model’s decision-making process.

Figure 1: Amharic sexually explicit document classification model workflow.

The following section provides a concise overview of the modules included in the proposed Amharic sexually explicit content detection model. Each module plays an important role in how the model works, helping it to accurately identify sexually inappropriate content in Amharic text.

Ethical statement

For this study, we collected data from publicly available social media posts, following each platform’s Terms of Service (ToS) to ensure compliance. To protect user privacy, all usernames and identifiable information were removed during data preprocessing. This technique is in line with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and Ethiopia’s data protection regulations, which protect people’s rights (Yilma, 2015). Additionally, the research received ethical approval from Jimma University’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) (based on protocol 4.1.4), ensuring adherence to both ethical and legal standards at every stage.

Amharic explicit comments dataset

The Amharic Explicit Comments Dataset was created to aid in the automatic identification of explicit content in the Amharic language. This dataset serves as a valuable resource for developing algorithms that can effectively filter inappropriate material. To build an effective detection model, we collected data from social media platforms like TikTok, YouTube, Facebook, and X (formerly Twitter). Most of the data was scraped automatically, while a smaller portion was collected manually. Each sample was annotated as explicit or non-explicit based on criteria including the use of explicit terms or sexual slang, sexually offensive language, and content open to sexual interpretation.

The collected dataset consists of a total of 34,710 textual comments divided into two categories: sexually explicit comments and non-sexual comments. The data is saved in Excel format. Of these, 17,199 comments are labeled as sexually explicit, while 17,511 comments are categorized as non-sexual. There are 18.84 words on average in each comment, with a minimum of 1 word and a maximum of 618 words. The wide range illustrates the variability in comment length, spanning from single-word responses to significantly longer, more detailed comments. The dataset is labeled in binary format, where 0 represents non-sexual comments and 1 represents sexually explicit comments. Finally, the data is passed to the preprocessing module of the proposed model.

Preprocessing

Data cleaning: Preprocessing Amharic sexually explicit comments for NLP tasks involves several steps to clean, normalize, and prepare the text for analysis. The first step typically involves text cleaning, where irrelevant characters such as punctuation, symbols, and non-Amharic scripts are removed. Emojis, numbers, and special characters that appear in comments are also filtered out and removed from the comment or post.

Normalization: Normalization is crucial for handling variations in spelling and encoding issues specific to the Amharic script. This importance arises from the fact that certain Amharic characters share the same sound and meaning, yet there are no clear rules governing their usage (Hirpassa & Lehal, 2023). For instance, the word for “power” can be written as ሀይል, ሃይል, ሐይል, ሓይል, ኅይል, ኃይል, or ኻይል, all pronounced as “hāyil” and carrying the same meaning. To address this issue, we compiled a list of Amharic characters that share the same sound and meaning and selected one representative character to replace the others. The selection of the base character was based on its frequency of occurrence in our dataset. In the above example, we first check the frequency of the characters ሀ, ሃ, ሐ, ሓ, ኅ, ኃ, and ኻ, pronounced (hā). The most frequent character is ሀ, so we replace ሃ, ሐ, ሓ, ኅ, ኃ, and ኻ with ሀ. So, the word “power” is represented only as ሀይል, and normalization maintains consistency in the representation of concepts or objects. We adapt the normalization technique introduced by Endalie (2025).

Tokenization: Tokenization is performed to split the text into individual words or tokens. This step can be particularly challenging in Amharic due to the language’s agglutinative nature, where words are often formed by combining multiple morphemes. For example, the Amharic sentence “ስለቤት መጨነቅ አቁም” translates to “Stop worrying about the house.” When we tokenize this sentence using methods commonly applied in English, which primarily rely on whitespace as a delimiter, it treats “ስለቤት” as a single word since there is no internal space. This tokenizer produces the tokens [“ስለቤት”, “መጨነቅ”, “አቁም”]. However, this is not the final result, as it requires breaking down this agglutinative form into its constituent morphemes: the prefix “ስለ” (about) and the noun “ቤት” (house). The final result is [“ስለ”, “ቤት”, “መጨነቅ”, “አቁም”], which is essential for proper grammatical analysis and meaning extraction in Amharic. To overcome this challenge, we used a rule-based word segmentation method that works well for tokenizing Amharic texts. This approach involves defining explicit “if-then” segmentation rules for various linguistic phenomena, including prefixes, suffixes, compound words (often lexicon-based), punctuation, and digits.

Stop word removal: Stop word removal is applied to the dataset to eliminate common words like “እና” (and), “ወደ” (to), and “ነው” (it is) that contribute insignificant meaning to the text analysis. Although there is no well-prepared stop word list for the Amharic language, we utilized the stop word list developed by Endalie, Haile & Taye (2023) and Woldeyohannis & Meshesha (2022). We eliminate these words using a nested iteration statement that checks each token found in the comment against the pre-prepared stop word list. If a token is found in the list, it is automatically removed.

Feature extraction

The feature extraction module is crucial for detecting sexually explicit Amharic comments, often using Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF). TF-IDF converts text into numerical features, emphasizing words that are frequent in a document but rare across the dataset. The IDF, a core part of TF-IDF, helps measure word relevance and is widely used in text mining (Zhou et al., 2024). The IDF measures how important a term is in the corpus. The mathematical equation for computing IDF is as follows (Nguyen, 2014):

(1) where t: The term (word) for which IDF is calculated. D: the corpus. N: denotes the total number of documents in the corpus. df(t): The document frequency of the term t. The TF is computed as follows:

(2)

Then the TF-IDF is computed as

(3)

In the Amharic sexually explicit comment detection, TF-IDF highlights significant words by downplaying common terms and emphasizing unique ones that are indicative of explicit content. This refined representation helps the model differentiate between neutral and explicit comments more effectively, improving detection accuracy. The document matrix is constructed with documents as rows and terms (features) as columns. Each cell contains the TF-IDF score of a term within its respective document. A value of zero is assigned if the term is absent. This matrix then serves as input for the machine learning models used in the comparative analysis with the fine-tuned BERT model.

Train test split

When crafting a machine learning or deep learning model to identify sexually explicit comments in Amharic, one of the most important steps is dividing the data into training and testing sets (Abebaw, Rauber & Atnafu, 2024). Before we start training the model, we split the collected dataset of comments into two groups: one for training and one for testing. The model uses the training set to learn the patterns and features that distinguish sexually explicit content from non-sexual content in Amharic comments and posts. The testing set then acts as an independent measure to evaluate how well the model performs on data it has not seen before.

In our study, we employed an 80/20 train-test split. This allocated 80% of the data for model training and reserved the remaining 20% for evaluation. This ratio is widely considered a suitable balance for document classification tasks (Bichri, Chergui & Hain, 2024), as it allows effective learning from a sufficiently large training set while providing a robust testbed for measuring performance on unseen examples. This approach promotes the best for generalization and mitigates the risk of overfitting, where the model becomes overly specialized to the training data and performs poorly on novel inputs.

Model selection

Model selection is essential for creating effective systems that can identify sexually explicit remarks in Amharic, which is an essential component of content moderation (Demilie & Salau, 2022). As more user-generated content surfaces on online platforms, especially in languages with distinctive linguistic and cultural characteristics like Amharic, the demand for automatic methods to recognize and filter negative statements is growing. This section evaluates various state-of-the-art deep learning, machine learning, and natural language processing models developed specifically for Amharic.

Fine-tuned BERT for Amharic language

BERT is a pre-trained language model used in NLP. Fine-tuning adapts it for specific tasks in the Amharic language, like hate speech detection, question answering, and sentiment analysis (Yeshambel, Mothe & Assabie, 2023). The process involves obtaining the fine-tuned model, preparing input data, feeding it to the model, and getting a probability score. The document is then classified based on this score. Fine-tuned BERT offers high accuracy, reduced training time, and contextual understanding, simplifying the classification of Amharic documents (Alemneh, Atnafu & Rauber, 2020).

In this study, we utilized a pre-trained BERT model formerly fine-tuned for hate speech detection in the Amharic language. The fine-tuned model is available on Hugging Face at the following link: https://huggingface.co/devaprobs/hate-speech-detection-using-amharic-language. The model was fine-tuned using a dataset obtained from Mendeley Data, which consists of 30,000 labeled instances. This makes it one of the most comprehensive datasets available for detecting hate speech in Amharic. The fine-tuning process was conducted using Hugging Face’s Trainer API and involved a carefully curated dataset of labeled Amharic text. However, due to the lack of a dataset containing explicit content to train the BERT model from scratch, we utilized this pre-trained model to improve explicit content detection and conserve computational resources.

In conclusion, our research aims to utilize the learned parameters of a pre-trained model and adapt them for detecting sexually explicit content in Amharic. This allows us to achieve high accuracy in distinguishing explicit content from non-explicit content while significantly minimizing training time and resources. Additionally, this strategy considers the unique linguistic characteristics of the Amharic language, resulting in more accurate detection.

Learning methods

This section explores some state-of-the-art learning algorithms that are effective in document classification and content filtering (Mirończuk & Protasiewicz, 2018). They can also be used as a frame of reference to evaluate how well the proposed model performs in detecting sexually explicit content in Amharic by comparing its results with those of these algorithms. The algorithms discussed include Convolutional Neural Networks, Support Vector Machines, and Multi-Layer Perceptron.

Convolutional neural network

CNNs are deep learning models designed for processing structured data like images and text (Yamashita et al., 2018). CNNs, which are made up of convolutional, pooling, and fully connected layers, are excellent at classifying documents because they can recognize patterns and spatial hierarchies. Their benefits include efficiency with big datasets, robustness to noise, and automatic feature learning. The fundamental mathematical operations that characterize a CNN and how they are modified for text are as follows: The convolution operation for input text X (represented as word embeddings or one-hot vectors) is defined as (Verma & Khandelwal, 2019):

(4)

Here, the filter F slides across X to compute the dot product, generating a feature map that highlights essential text patterns. An activation function, often ReLU, is then applied:

(5)

ReLU introduces non-linearity, emphasizing relevant features while ignoring noise. Finally, connected layers use a softmax function for classification:

(6)

This converts logits (z) into probabilities, indicating the likelihood of each class.

Support vector

Support Vector Machines are supervised learning algorithms employed for classification and regression tasks (Brereton & Lloyd, 2010). They aim to determine the optimal hyperplane that separates a dataset into two categories in high-dimensional space. A hyperplane is a flat surface that separates different classes of data. The support vectors are the data points that are closest to this hyperplane, and the margin refers to the distance between the hyperplane and these support vectors. This margin is crucial as it helps define how well the hyperplane can separate the classes. SVMs perform exceptionally well in high-dimensional spaces and maintain strong generalization by effectively resisting overfitting. Given a dataset with features xi and labels yi (where yi ∈ {−1,1}), the SVM optimization problem can be formulated as (Wang, He & Sun, 2023):

(7) where w is the weight vector defining the hyperplane. Subject to the constraint:

(8) where b is the bias term, and ⋅ denotes the dot product. SVMs are powerful for complex classification and regression tasks due to their ability to find an optimal separating hyperplane while maintaining robustness through support vectors.

Multilayer perceptron

A Multi-Layer Perceptron is an artificial neural network with multiple layers of interconnected nodes, known for capturing complex data relationships (Worden, Staszewski & Hensman, 2011). MLPs are effective in supervised learning tasks like classification and regression, consisting of input, hidden, and output layers. For a neuron j in the hidden layer, the weighted sum of inputs x and weights w is calculated as (Endalie & Haile, 2021):

(9) Here zj is the weighted sum for neuron j, wji is the weight from input iii to neuron j, xi is the input feature, bj is the bias term for neuron j. This sum is passed through a non-linear activation :

(10) where aj is the neuron’s activation. The output layer processes activations similarly:

(11) where is the predicted output, woj are the weights from the last hidden layer, and bo is the output bias. Training involves forward and backward propagation, with optimization algorithms like Stochastic Gradient Descent or Adam adjusting weights and biases.

Explainable artificial intelligence

Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) has emerged as a game-changer in text mining, offering not only the ability to process vast amounts of text data but also the capability to reveal how and why specific results are generated (Saeed & Omlin, 2023). For instance, analyzing a vast collection of documents or social media posts to identify trends, sentiments, or key insights is made possible by XAI, which breaks down complex algorithms into understandable and interpretable steps (Rane & Paramesha, 2024). In the context of Amharic, XAI unlocks valuable insights by analyzing language patterns, including word usage, grammar, and context, to provide clear explanations for its conclusions. This enhances trust in the technology and enables users to take informed action based on the findings.

Consequently, we incorporated XAI as a key component of our proposed model for detecting sexually explicit content in Amharic. XAI enables us to assess how well the model interprets understated linguistic variations present in a given text. To achieve this, we used LIME, which identifies the most influential features, such as words or phrases, in the model’s decision-making process.

We selected LIME for its exceptional capacity to deliver clear and actionable explanations for individual predictions (Hassan et al., 2025). This capability is crucial for sensitive tasks, such as detecting sexually explicit content, where understanding the rationale behind a specific post being highlighted is essential for developing trust and accountability. In contrast to more complex methods like Shapley additive explanations (SHAP), it visualizes the results in a form that is easily accessible to non-technical audiences (Hakkoum, Idri & Abnane, 2024). Additionally, its local approach is resilient to the noisy data common in this domain, including evolving slang and ambiguous cultural references. While SHAP uses game theory for consistent and fair feature attribution across all predictions, LIME provides clearer, more accessible explanations for a broader audience (Santos, Guedes & Sanchez-Gendriz, 2024). This makes LIME the preferred tool for this application.

Evaluation metrics

When developing automated systems to detect sexually explicit content in Amharic, rigorous evaluation methodologies are essential. Subjective assessments are insufficient. Instead, quantitative evaluation metrics must be used to objectively measure system performance, including accuracy, error rates, and reliability (Ayalew & Asfaw, 2021). Choosing appropriate metrics is crucial to ensure the tool effectively moderates online spaces while minimizing risks like false positives (misclassifying benign content as explicit). In this study, we outline the specific evaluation metrics applied, along with their corresponding formulas, as detailed in Table 1.

| Evaluation metric | Formula |

|---|---|

| Accuracy | (TP + TN)/(TP + TN + FP + FN) |

| Precision | TP/(TP + FP) |

| Recall (Sensitivity, True positive rate) | TP/(TP + FN) |

| F1-score | 2 * (Precision * Recall)/(Precision + Recall) |

Note:

TP, True Positives; TN, True Negatives; FP, False Positives; FN, False Negative.

Results and discussion

Experiment

We conducted all experiments in this article using Python Notebook and the GPU provided by Kaggle. We then utilized the Transformers library to retrain a fine-tuned BERT model, which we had originally designed for detecting hate speech in Amharic. This library offers pre-trained deep learning models well-suited for numerous natural language processing tasks, such as sentiment analysis, fake news detection, question answering, and text classification. To adapt the pre-trained BERT model from the Hugging Face library, we used AutoTokenizer for tokenization and AutoModelForSequenceClassification for classifying sexually explicit content. The input for the BERT model is token IDs, attention masks, token type IDs, and decoded texts of the custom dataset, which are generated by the AutoTokenizer from Hugging Face.

After setting up the model, we optimized its hyperparameter values using a grid search strategy. Grid search is a systematic and exhaustive method for identifying the optimal combination of hyperparameters in machine learning and deep learning models (Zhao, Zhang & Liu, 2024). This technique involves defining a range of potential values for each hyperparameter and evaluating the model’s performance across all possible combinations of these values. We manually defined the array values for the most influential hyperparameters based on GPU and dataset size (Raiaan et al., 2024). Then, the model is trained with combinations of these values in the array. The combination of hyperparameter values that yields the best accuracy is selected automatically. The values that produced the optimal result, along with the candidate hyperparameter values at the time of selection, are presented in Table 2.

| Hyperparameters | Final selected value | Range of values considered during selection |

|---|---|---|

| eval_strategy | Epoch | [“no”, “epoch”, “steps”] |

| save_strategy | Epoch | [“no”, “epoch”, “steps”] |

| logging_strategy | Epoch | [“no”, “epoch”, “steps”] |

| num_train_epochs | 4 | [1, 2, 3, 4, 5] |

| per_device_train_batch_size | 4 | [2, 4, 8] |

| per_device_eval_batch_size | 4 | [2, 4, 8] |

| weight_decay | 0.01 | [0.0, 0.01, 0.1] |

We employed a single train-test split for all experiments in this article, rather than k-fold validation, which is typically more effective with smaller datasets (Endalie, 2025). As a result, we found our dataset’s size more suitable for a single train-test split. We initially divided the entire dataset into training and testing sets using an 80/20 splitting ratio. Furthermore, the training data is further divided into training and validation sets, employing a 90/10 splitting ratio to train the fine-tuned BERT model. This meant 90% of the training data was used to train the model, and 10% was used for validation to assess its learning progress.

Results

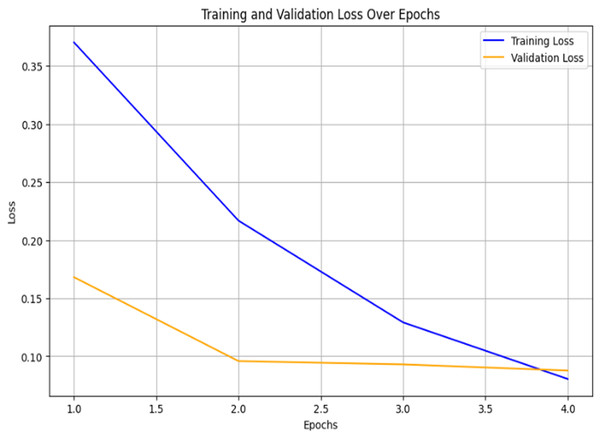

Utilizing this data, we trained the fine-tuned model using the hyperparameter values detailed in Table 2. To determine the optimal number of training epochs, we conducted a comparative analysis of the model’s performance across different epoch settings. This analysis revealed that the model achieved optimal performance with four epochs. We present the training results over these four epochs in Table 3. The table presents the training and validation losses, as well as the precision, recall, F1-score, and accuracy. Throughout the training process, the model’s performance improved significantly.

| Epoch | Training loss | Validation loss | Precision | Recall | F1 | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.354900 | 0.176970 | 0.949090 | 0.948866 | 0.948867 | 0.948866 |

| 2 | 0.208500 | 0.121760 | 0.975326 | 0.975153 | 0.975147 | 0.975153 |

| 3 | 0.130800 | 0.089003 | 0.983443 | 0.983435 | 0.983435 | 0.983435 |

| 4 | 0.074100 | 0.091809 | 0.985604 | 0.985596 | 0.985595 | 0.985596 |

Furthermore, we evaluated the performance of the fine-tuned BERT model using the 20% testing set. The testing set is completely unseen during training. This evaluation assessed the model’s ability to generalize to new data and accurately classify Amharic explicit and non-explicit text. Table 4 shows the model’s performance in classifying Amharic sexually explicit content, including precision, recall, F1-score, and accuracy for each category. These metrics offer a detailed view of the model’s ability to correctly identify sexually explicit content while minimizing false positives and false negatives.

| Category | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (non-explicit) | 94% | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.94 |

| 1 (explicit) | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.94 |

Our fine-tuned BERT model demonstrated balanced performance in classifying Amharic sexually explicit comments, achieving an overall accuracy of 94%. The model’s precision for category 0 is 0.95, indicating a very low rate of false positives, which means it is highly reliable when predicting non-explicit comments. For category 1, the precision is 0.94, showing strong reliability in identifying explicit content. The recall for category 0 is 0.94, reflecting its strong ability to correctly identify non-explicit content and minimize false negatives. In contrast, the recall for category 1 is 0.95, demonstrating an equally strong capacity to identify explicit content accurately.

The F1-scores of 0.94% for both classes highlight the model’s balanced performance, indicating that it does not favor one type of error over the other. The closely aligned macro-average and weighted average scores, both at 0.94%, confirm that this robust performance is consistent across the entire dataset. These results establish that our model is a highly effective and reliable tool for this binary classification task.

This high performance is a direct result of a robust training process designed to prevent overfitting. We used the training and validation loss curves to demonstrate how the model learns from the training dataset and generalizes to unseen validation data. A training accuracy of 0.98 and a testing accuracy of 0.94 initially suggested overfitting. Figure 2 illustrates the validation loss curve, which was generated to diagnose this issue and show the effect of the weight decay regularization we employed. The loss curve illustrates a healthy training pattern: as the training loss decreases, the validation loss also declines and, importantly, converges closely with the training loss after 3.0 epochs. The final minimal gap between the two loss curves, nearly 0.05, is a strong indication that weight decay was successful in preventing severe overfitting.

Figure 2: Training and validation loss over epochs.

The small but persistent accuracy gap is a reflection of the slight divergence in the loss curve between 1.5 and 3.0 epochs. This divergence is a generalization gap that regularization aims to minimize. Although weight decay did not eliminate this gap, which would be impossible without compromising the model’s capacity, it successfully reduced it to a minimal level, as confirmed by the loss curves.

We further analyzed the model’s performance using a confusion matrix. This matrix offers a detailed view of the model’s classification accuracy, including the number of instances in each category and the model’s prediction accuracy for each class (Vujovic, 2021). Table 5 presents the confusion matrix for our explicit comment classification model, comparing actual classifications with the model’s predictions and categorizing them into four quadrants (True Positive, True Negative, False Positive, and False Negative).

| Predicted | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-explicit (0) | Explicit (1) | ||

| Actual | Non-explicit (0) | 3,308 | 210 |

| Explicit (1) | 179 | 3,320 | |

The above table presents the confusion matrix summarizing the model’s performance in distinguishing between explicit and non-explicit Amharic comments. Out of a total of 3,518 non-sexually explicit comments, 3,308 were correctly identified. However, 210 non-sexually explicit comments were incorrectly classified as explicit, and 179 explicit comments were misclassified as non-explicit. Additionally, 3,320 explicit comments were accurately identified.

To strengthen the validity of our findings, we analyzed misclassifications from our model. We examined using the comment, “አብረን ብናድርና ተሞካክረን አሸናፊው ቢለይ ምን ትያለሽ?” (“What do you think if we spend the night together and compete to see who wins?”), was an explicit comment that our model misclassified as non-explicit. The model likely failed to detect the sexual nature of this comment because it depends on keyword detection. In Amharic, this kind of proposition uses culturally nuanced metaphors and euphemisms such as አሸናፊው (“compete”) and ቢለይ ምን ትያለሽ (“decide who wins”) rather than direct sexual terminology.

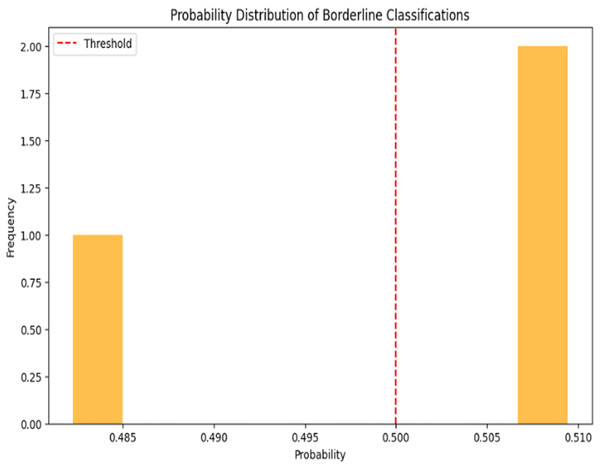

To determine whether such errors were isolated or part of a broader pattern, we analyzed the probability distribution of borderline classifications. As shown in Fig. 3, the red dashed line at 0.500 is our decision threshold, separating explicit from non-explicit comments. The histogram highlights comments that the model struggles to classify with high confidence. For instance, one comment was classified as non-explicit with a probability score of about 0.485, and two were classified as explicit with a score of about 0.508. The proximity of these scores to 0.5 underscores the model’s hesitation. It found these comments ambiguous and lacking the strong indicators needed for a confident prediction.

Figure 3: Distribution of classification probabilities highlighting model uncertainty around the 0.5 threshold.

For example, the comment “ለንስሀ እራቁትን መቅርብ ጥሩ ነው” (“It is important to bring yourself naked for repentance”) is a borderline case. Although its meaning is non-explicit, a metaphor for confessing one’s sins without hiding anything, the model likely assigned it a probability score near the threshold (e.g., 0.485), classifying it as non-explicit but with low confidence. The model identified the literal keyword “naked” as a potential indicator of explicit content, which conflicted with the non-explicit context and produced an uncertain prediction. In contrast, the absolute classifier labeled it as explicit (category 1).

Explainable artificial intelligence

We utilized XAI in addition to the model developed for identifying sexually explicit content. This approach helps clarify how the model differentiates between sexually explicit and non-sexual text, making the process more transparent for users. By clarifying how decisions are reached, users can better understand the factors that influence these classifications, which in turn fosters greater trust in the model’s outcomes.

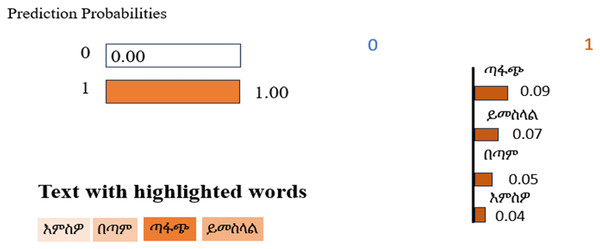

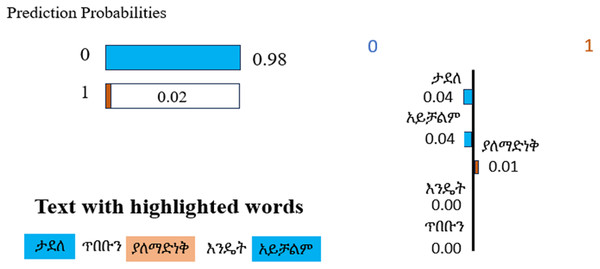

As an illustration of the explainability framework, two examples were selected: one comment classified as sexually explicit by the model and one classified as non-sexual. The comment “እምስዎ በጣም ጣፋጭ ይመስላል” (Your pussy looks very delicious) received a classification of sexually explicit. Conversely, the comment “ታደለ ጥበቡን ያለማድነቅ እንዴት አይቻልም” (How can one not admire Tadele’s wisdom?) was classified as non-sexual. The factors underpinning these classifications are detailed in Figs. 4 and 5, which provide insight into the model’s feature weighting and contextual understanding.

Figure 4: Prediction probabilities for an example of a sexually explicit comment.

Figure 5: Prediction probabilities for an example of a non-sexually explicit comment.

Figure 4 illustrates the trained model’s classification of the example “እምስዎ በጣም ጣፋጭ ይመስላል” (Your pussy looks very delicious). The model analyzes the sentence for features indicative of sexually explicit content. The presence of “እምስዎ” (your pussy) suggests the message is directed at a specific individual and refers to a private body part. “ይመስላል” (looks) implies an assessment of the body part’s appearance. The intensifier “በጣም” (very) emphasizes the description. Finally, “ጣፋጭ” (delicious) carries a connotation of desirability, contributing to the sexually suggestive nature of the sentence. Based on these linguistic features, the model predicts a label of 1, which aligns with the actual label.

Figure 5 illustrates the trained model’s interpretation of the sentence “ታደለ ጥበቡን ያለማድነቅ እንዴት አይቻልም” (“How can one not admire Tadele’s wisdom?”). The model correctly identifies “ታደለ” (Tadele) as a proper noun. ‘ጥበቡን’ (wisdom) functions as a noun referring to Tadele’s intellect. ‘ያለማድነቅ’ (admire) serves as a verb expressing positive sentiment. ‘እንዴት አይቻልም’ (how can one not) operates as a rhetorical question to enhance the preceding sentiment. As a result of this linguistic analysis, the model predicts a non-sexual classification, assigning a label of 0, which aligns with the actual label.

Comparison with other models

Before comparing the proposed model with the selected model, we need to determine the hyperparameter values that produced the optimal results for these classifiers. We employ the same strategy used for the proposed model, which is grid search. First, we manually create an array of values for each influential parameter based on the dataset size and the GPU used (Raiaan et al., 2024). The algorithm then tests the combined effects of these hyperparameters from the array. The hyperparameter values for each classifier that yielded optimal classification results are presented in Table 6.

| Models | Hyperparameters | Value |

|---|---|---|

| CNN | Activation | ‘relu’ |

| Dropout | 0.5 | |

| Optimizer | ‘adam’ | |

| Batch_size | 2 | |

| Epochs | 10 | |

| SVM | Kernel | ‘rbf’ |

| Probability | ‘True’ | |

| Max_iter | 200 | |

| MLP | No. of Hidden Layers | 1 |

| No. of Neurons | 50 | |

| Max_iter | 50 |

Using these optimal configurations, we conducted a comparative analysis to assess the efficacy of our proposed model against the established base BERT model, CNN, SVM, and MLP classifiers. Table 7 summarizes the results of this analysis, presenting the accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score for each model on a class-by-class basis. We trained the base BERT model using the same hyperparameter values as our proposed model. This comparison provides a quantitative evaluation of our model’s performance relative to these benchmark algorithms.

| Model | Class | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base BERT | 0 | 65% | 0.71 | 0.52 | 0.60 |

| 1 | 0.62 | 0.78 | 0.69 | ||

| CNN | 0 | 89% | 0.87 | 0.92 | 0.9 |

| 1 | 0.91 | 0.86 | 0.88 | ||

| SVM | 0 | 94% | 0.91 | 0.97 | 0.94 |

| 1 | 0.97 | 0.91 | 0.94 | ||

| MLP | 0 | 93% | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.93 |

| 1 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.93 | ||

| Proposed model | 0 | 94% | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.94 |

| 1 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.94 |

The table above presents a detailed performance comparison of the proposed model against the base BERT model, as well as SVM, CNN, and MLP classifiers, on a class-wise basis. The base BERT model demonstrated the weakest performance, with a significantly lower overall accuracy of 65%. Its results were highly imbalanced: for Class 0, high precision (0.71) was paired with low recall (0.52), indicating a tendency to miss non-explicit content (false negatives). For Class 1, high recall (0.78) was offset by lower precision (0.62), leading to a higher rate of false alarms. This imbalance is reflected in its modest F1-scores of 0.60 for Class 0 and 0.69 for Class 1.

The CNN model achieved an overall accuracy of 89%. However, its performance varied across classes. For Class 0, the model demonstrated higher recall (0.92) than precision (0.87), meaning it correctly identified most instances of Class 0 but also included more false positives. In contrast, for Class 1, precision (0.91) exceeded recall (0.86), indicating it was more selective but missed some true cases. This imbalance led to F1-scores of 0.90 for Class 0 and 0.88 for Class 1, suggesting that the model’s performance was inconsistent between classes.

In contrast, the SVM model achieved a high accuracy (94%) and demonstrated strong performance. It achieved high precision (0.97) and recall (0.91) for Class 1 and solid scores for Class 0 (precision: 0.91, recall: 0.97), leading to excellent and consistent F1 scores of 0.94 for both classes. The MLP model also performed very well, achieving an accuracy of 93%. Its most notable characteristic is its perfect balance across both classes, with identical precision, recall, and F1 scores of 0.93 for Class 0 and Class 1, demonstrating remarkable consistency.

Our proposed model achieved the best overall results with an accuracy of 94%. It slightly outperforms the SVM by achieving a superior balance between precision and recall for both classes. Most significantly, it matches the perfect balance of the MLP but at a higher performance level, with all metrics for both classes reaching 0.94. This indicates that our model not only achieves high accuracy but also minimizes both false positives and false negatives more effectively than the other models, establishing it as the most robust classifier for this task.

In conclusion, this comparison demonstrates that our proposed model outperforms the others in terms of accuracy, precision, and recall, establishing it as a strong candidate for Amharic text classification. Specifically, its enhanced ability to detect sexually explicit content in Amharic can be attributed to two key factors, as supported by Zhong & Goodfellow (2024): (1) the extensive linguistic knowledge acquired through pre-training on large text corpora, enabling effective adaptation to specific tasks even with limited labeled data, and (2) BERT’s architectural capacity to capture nuanced semantic relationships and contextual dependencies within sentences, which is particularly advantageous for complex classification tasks.

Beyond standard metrics like accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, we were required to understand the practical impact of small gains in model performance, particularly in explicit content detection. We focused on two key measures: the reduction in misclassifications and the increase in accuracy. Recognizing the sensitive nature of this model, we hypothesized that even modest improvements could provide meaningful benefits. Misclassification analysis confirmed this hypothesis. The accuracies of 93% and 93.5% were randomly selected to examine how small increases in classification accuracy influence the number of misclassified instances. The 94% accuracy represents the actual performance of the model proposed in this study. For example, with an 80–20 data split, increasing the model’s accuracy from 93% to 93.5% reduced the number of misclassifications by about 27.77, lowering the error count from approximately 388.75 to 360.98. Further increasing the accuracy to 94% yielded a significant reduction of 55.54 misclassifications, bringing the total down to 333.22.

On unseen data, the model achieved 60% accuracy, with two misclassifications out of five examples, which is considered relatively low for this dataset. In comparison, a baseline accuracy of 93% would predict approximately 0.35 misclassifications per 100 samples. The improved accuracies of 93.5% and 94% would predict 0.32 and 0.30 misclassifications, respectively, further emphasizing that higher accuracy translates to reduced errors. Since the model still struggles with unseen data and understanding the complex nature of the Amharic language, future research will concentrate on expanding our dataset to include code-switching examples. We will also work on further refining the model’s architecture to improve its detection of sexually explicit Amharic comments.

Conclusion

In this study, we introduced a BERT + XAI model designed to detect sexually explicit comments in the Amharic language. The proposed model comprises several modules, including document collection, preprocessing, feature extraction, data splitting, model training, and the application of XAI. We employed a fine-tuned BERT model specifically designed to identify hate speech in the Amharic language. Our findings demonstrate that this BERT-based model is highly effective at distinguishing between sexually explicit and non-sexually explicit content, showcasing its ability to handle the unique linguistic features of Amharic. Additionally, we incorporated explainability techniques that enhance our model’s decision-making process, making it easier for users to understand how comments are categorized by clearly highlighting the clues used. This model achieved significant improvements in performance metrics compared to traditional models like base BERT, SVM, CNN, and MLP. This study contributes to the field of natural language processing, with a particular focus on advancing research for the Amharic language. It also highlights the pressing need for advanced AI methods to effectively manage and mitigate sensitive issues such as online sexually explicit or inappropriate content. Looking ahead, we plan to expand our dataset to include code-switching and further refine our model to enhance its detection capabilities, ultimately aiming to create a safer online environment for Amharic speakers. Overall, our findings highlight the promise of XAI in tackling classification challenges across various linguistic contexts.