Evaluating video-based synthetic data for training lightweight models in strawberry leaf disease classification

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Nicole Nogoy

- Subject Areas

- Algorithms and Analysis of Algorithms, Artificial Intelligence, Computer Vision, Data Mining and Machine Learning, Neural Networks

- Keywords

- Video synthetic data, Lightweight models, Precision agriculture, Sora, Strawberry leaves, Deep learning

- Copyright

- © 2026 Miski

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2026. Evaluating video-based synthetic data for training lightweight models in strawberry leaf disease classification. PeerJ Computer Science 12:e3521 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3521

Abstract

Collecting large, diverse, and well-labeled datasets remains a persistent bottleneck in agricultural computer vision. This study explores the efficacy of video-based synthetic data, generated via the diffusion-transformer model Sora, to address this scarcity for strawberry leaf disease classification. A synthetic dataset of 1,467 images was curated by extracting frames from generated videos, using structured text prompts and reference images to capture temporal variations in lighting and leaf morphology. This data was utilized to train six lightweight deep learning architectures (DenseNet-121, EfficientNet-B0, MobileNetV3-Small, ResNet-18, ShuffleNetV2, and Vision Transformer (ViT)-Tiny) using a feature extraction strategy. The models were evaluated on a held-out test set of 618 real-world images to assess synthetic-to-real generalization. ResNet-18 achieved the highest nominal performance, with accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score all reaching 98.71%. A 5-fold stratified cross-validation further confirmed the approach’s stability with an average accuracy of 98.9%. Notably, statistical analysis using McNemar’s test revealed no significant performance difference (p > 0.05) between ResNet-18 and the significantly lighter MobileNetV3-Small. These findings demonstrate that video-derived synthetic data can effectively bridge the domain gap, enabling the training of robust, resource-efficient models suitable for deployment on edge devices in precision agriculture.

Introduction

Crop disease, pest, and weed attacks constitute major threats to the agricultural industry, resulting in annual losses of up to 40% of global crop production and costing the global economy over USD 220 billion (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2023). Early plant disease identification is therefore crucial for timely intervention, minimizing crop loss, and promoting sustainable farming (Jafar et al., 2024; George et al., 2025). Strawberry cultivation is particularly susceptible to diverse fungal pathogens, including Mycosphaerella fragariae (common leaf spot), Diplocarpon earlianum (leaf scorch), Podosphaera aphanis (powdery mildew), and emerging Neopestalotiopsis species (Ávila-Hernández et al., 2025; Aldrighetti & Pertot, 2023; Carisse & Fall, 2021; Cline & Moparthi, 2024). Because these pathogens persist in plant debris and spread rapidly under warm, humid conditions, early detection is vital to prevent defoliation and fruit rot.

Precision agriculture (PA) driven by artificial intelligence (AI) offers data-driven solutions to these detection challenges (Kamilaris & Prenafeta-Boldú, 2018; Jha et al., 2019; Kok et al., 2021). Deep learning (DL), specifically convolutional neural networks (CNNs), has transformed agricultural computer vision, enabling effective applications in disease identification and yield prediction (El-Sakka, Alotaibi & Okasha, 2024; Saini & Nagesh, 2025; Abbas et al., 2021b; Singh, Sharma & Gupta, 2023; He et al., 2024). However, the performance of these models relies heavily on the availability of large, diverse, and well-labeled datasets (Rahman et al., 2024; Mishra et al., 2023). Obtaining such data from the real world is labor-intensive and costly due to biological variability and unpredictable field conditions (Nazki et al., 2020; Antwi et al., 2024; Saini et al., 2025). Consequently, limited data availability often results in class imbalance and reduced model generalizability (Miftahushudur et al., 2025; Adegbenjo & Ngadi, 2024).

Synthetic data generation has emerged as a promising solution to data scarcity. While traditional geometric transformations and 3D simulations offer some relief, they are often limited by semantic diversity or high computational costs (Nazki et al., 2020; Cieslak et al., 2024; Hu et al., 2022; Barth et al., 2018). Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) provided an early breakthrough in synthesizing agricultural images (Goodfellow et al., 2014; Akkem, Biswas & Varanasi, 2024; Li et al., 2024). Despite their success in crops like tomato and citrus (Abbas et al., 2021a; Zeng et al., 2020), GANs frequently suffer from training instability, mode collapse, and domain gaps that hinder generalization (Arjovsky, Chintala & Bottou, 2017; Wang & Deng, 2018; Man & Chahl, 2022). More recently, diffusion models have surpassed GANs in generating high-quality, diverse samples (Ho, Jain & Abbeel, 2020; Chen et al., 2024). These models have shown promise in agricultural applications, such as weed recognition and unseen disease class generation (Chen et al., 2024; Mori, Naito & Hosoi, 2024; Das et al., 2025).

Current synthetic approaches, however, typically operate at the single-image level, overlooking the temporal dimensions critical in dynamic agricultural environments. Video synthesis offers the capability to capture temporally dynamic leaf motion, progressive symptom development, and varying lighting conditions within a single generation process (Klein et al., 2024). This temporal context contains valuable information that may improve model robustness. This study addresses this gap by exploring the use of OpenAI’s Sora, a diffusion-transformer model, to generate synthetic video frames for training deep learning models (OpenAI, 2025). Focusing on strawberry leaves (Hariri & Avşar, 2022), this research evaluates the potential of video-derived synthetic data to overcome the limitations of static image datasets.

Given the visual complexity and overlapping symptoms of these pathologies, this study adopts a binary classification strategy, distinguishing between “healthy” and “damaged” leaves. The “damaged” class serves as a broad operational category encompassing visible stress indicators such as necrotic spots, discoloration, curling, and fungal coating regardless of the specific biological etiology. This binary approach enables rapid, automated triage suitable for robotic intervention or large-scale infestation monitoring, prioritizing the identification of unhealthy plant tissue over granular diagnosis.

The primary objective of this study is to evaluate the efficacy of Sora-produced synthetic video frames for training DL models in strawberry leaf disease classification. By leveraging video generation, this approach introduces temporal information such as leaf movement and lighting shifts, generated through structured text prompts and reference images. This method aims to facilitate the rapid creation of diverse, labeled datasets without extensive fieldwork, thereby supporting edge AI systems for early disease management. The specific aims are as follows:

Create a synthetic dataset by leveraging Sora with structured prompts and text–image inputs that yield video sequences containing temporal variations, and use this data to train and refine lightweight deep learning models.

Conduct a thorough comparison of multiple model architectures trained solely on synthetic data and evaluated on real images, using metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and inference time, to identify resource-efficient designs suitable for field deployment.

Evaluate the capability of Sora-generated data to reduce the domain gap and boost the generalizability of DL models for strawberry leaf disease classification.

The article is organized as follows. ‘Related Work’ reviews the relevant literature on data augmentation and synthetic data generation in agriculture. ‘Material and Methods’ presents the materials and methods, which includes research framework, synthetic data generation, model architectures, and training and evaluation process. ‘Results’ reports the final experimental results with the training dynamics and test results of the models. In ‘Discussion’ the article discusses the implications of the findings, as well as the limitations, and ideas for future work. Finally, the work is concluded in ‘Conclusion’.

Related work

Traditional data augmentation has been the cornerstone for upscaling small-size agricultural datasets and reducing overfitting in deep learning models. These approaches apply different transformations to existing images to enhance the number and diversity of training data (Antwi et al., 2024; Sharma et al., 2024). Geometric transformations (rotation, translation, flipping, scaling) and photometric transformations are typical classical methods used to augment agricultural datasets (Hariri & Avşar, 2022; Yu et al., 2022). For instance, Shin et al. (2021) used rotation with different angles to enhance data for powdery mildew detection in strawberry leaves. Similarly, Dyrmann et al. (2016) presented a technique where HSV channels were modified and random shadows added to simulated data for agricultural purposes. However, traditional data augmentation adds minimal diversity as it does not introduce new semantic information (Nazki et al., 2020; Sharma et al., 2024). To address these limitations, researchers have increasingly turned to synthetic data generation algorithms, notably using advanced DL architectures such as GANs (Goodfellow et al., 2014; Rahman et al., 2024) and, more recently, diffusion models (Ho, Jain & Abbeel, 2020; Mori, Naito & Hosoi, 2024; Das et al., 2025). These models generate new realistic images, enriching datasets with greater variety and semantic content.

Generative adversarial networks

Generative adversarial networks (GANs), originally developed for general image synthesis tasks (Goodfellow et al., 2014), have become a popular method for image augmentation and synthesis in agriculture. Their ability to produce realistic and diversified images is promising for training robust DL models, particularly given the scarcity of large, diverse, and labeled agricultural datasets (Akkem, Biswas & Varanasi, 2024; Li et al., 2024). Early non-agricultural applications preceded their use in farming, but GANs were soon adapted for plant phenotyping, where Giuffrida, Scharr & Tsaftaris (2017) utilized DCGANs for realistic Arabidopsis plant image generation based on specified leaf counts. Similarly, Zhu et al. (2018) used the conditional GAN variant Pix2Pix to generate plant images for leaf counting, achieving a 16.67% reduction in counting error. Rahnemoonfar & Sheppard (2017) estimated tomato counts with simulated data, demonstrating synthesis for quantitative applications. GANs have played a crucial role in synthesizing diseased plant images. Nazki et al. (2020) presented an unsupervised image-to-image translation model based on GANs (AR-GAN) to expand plant disease datasets, reporting a 5.2% increase in tomato disease classification accuracy. Abbas et al. (2021a) applied a conditional GAN (CGAN) to enhance tomato leaf images from the PlantVillage dataset, achieving classification accuracies exceeding 97% with a DenseNet121 model, a 1–4% improvement over models trained on raw data alone. Zeng et al. (2020) employed DCGAN to generate and double citrus leaf training data, reporting a 20% increase in accuracy for disease identification. Although successful, GANs suffer from several technical limitations that hinder widespread adoption in agriculture, including:

Mode collapse: GANs often encounter unstable training dynamics and “mode collapse,” where the generator produces limited samples instead of covering the full data distribution (Sharma et al., 2024; Akkem, Biswas & Varanasi, 2024).

Resolution restrictions and fidelity: Early GAN models struggled with high-resolution images essential for subtle disease features, sometimes producing artifacts or unrealistic details (Akkem, Biswas & Varanasi, 2024; Zhang et al., 2022).

Domain gap: Synthetic images from GANs may lack real-world agricultural variations like shadows, occlusions, and reflections, creating discrepancies that affect generalization (Aghamohammadesmaeilketabforoosh et al., 2025; Tremblay et al., 2018).

Diffusion models

Diffusion models have emerged as powerful generative AI tools, surpassing GANs in synthesizing realistic and diverse images (Ho, Jain & Abbeel, 2020; Chen et al., 2024). In agriculture, diffusion models address data scarcity by generating high-quality samples with stable training and controllable processes. For instance, Chen et al. (2024) used diffusion models to enrich weed images, improving classification and segmentation across deep learning models. Zhang et al. (2025) proposed a Dual Attention Diffusion Model (DADM) for synthetic grain image generation. Their approach leverages attention mechanisms to improve the quality and diversity of generated images and yields better segmentation performance than baseline GANs, thereby offering enhanced support for downstream detection tasks. Zhou et al. (2025) presented an end-to-end framework combining diffusion-based feature synthesis with few-shot learning for sunflower diseases, achieving 95% precision, 92% recall, and 93% accuracy. Recent advancements include diffusion for agricultural image enhancement in quality monitoring (Zhang et al., 2025) and long-tailed pest classification (Du et al., 2025), demonstrating superior handling of imbalanced datasets. While static synthetic image generation via GANs or diffusion models has advanced data abundance, most methods operate at the single-image level, overlooking temporal dimensions critical in dynamic agricultural processes like disease progression. This study bridges this gap by pioneering Sora’s use for video-based synthetic data in agriculture, capturing cohesive temporal consistency and scene dynamics absent in prior approaches (OpenAI, 2024; Klein et al., 2024).

Materials and Methods

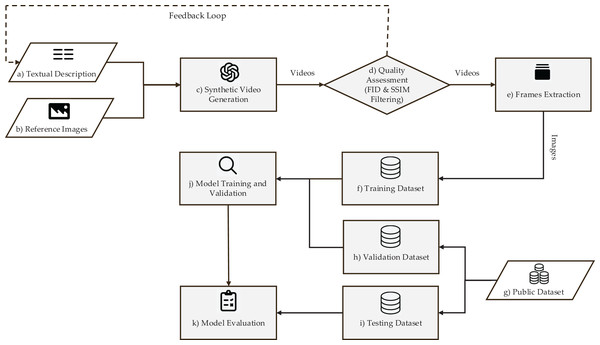

The proposed synthetic data-based training framework for plant disease classification has 11 components as shown in Fig. 1. The framework starts with (a) a text prompt of strawberry leaf condition, and (b) a real image of strawberry leaf. The text-image-prompt are provided as input to (c) the video generation model Sora that predicts synthetic videos showing the health or damage progression in different scenarios. These synthetic outputs are followed by (d) quality assessment, for which Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) measures the realism of the synthetic contents with respect to real-world images. Videos that passed quality criteria are processed through (e) frame extraction and preprocessing. At this stage, filtering using Structural Similarity Index Measure (SSIM) is also included to exclude close duplicates, and thus avoid dataset, and computational redundancies. The processed frames are consolidated to create (f) a synthetic training set. This artificial dataset is utilized for training a DL classifier for strawberry leaves. To estimate and tune the model performance on real-world data, (g) a publicly available validation dataset with real field images is used. The process of validation allows iterative refinement of the model. After training, final performance evaluation is carried out on (i) test set of real-world images from public datasets as an unbiased measure of generalization of the model in real agricultural conditions. The proposed framework systematically tackles the key challenges involved in synthetic-to-real adaptation, from controlled data generation to strict validation against real samples, thus providing a strong workflow for building practical plant disease classification solutions.

Figure 1: Synthetic dataset generation and training framework overview.

Dataset creation

The OpenAI Sora diffusion-transformer model was employed to generate synthetic training videos of strawberry leaves (OpenAI, 2025). Sora was chosen for its ability to generate high-fidelity videos with fine-grained control and option to include reference image with the prompt. The structured prompt template shown in Table 1 helped improve the output consistency. The prompts were manually iteratively refined to ensure the generated videos accurately reflected the biological descriptions of the diseases, rather than using automated prompt variation. This modular approach, aligned with synthetic data best practices (Tremblay et al., 2018), ensured comprehensive coverage of real-world variations. Also, it helped capture natural temporal variations that enhance dataset diversity through subtle frame-to-frame differences.

| Class | Prompt | Reference real image | Generated synthetic samples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy | Object: Realistic healthy strawberry leaf, matching the texture of the provided sample image. |  |

|

| Condition: No spots, discoloration, or wilting; include slight natural imperfections (e.g., minor vein prominence). | |||

| Environment: Plain, neutral gray background (resembling concrete or stone texture). | |||

| Lighting: Vary across frames: soft natural light, bright sunlight with shadows, dim overcast settings. | |||

| Camera: Incorporate movement with slight tilts, pans, and zooms; capture from multiple angles (top-down, side profile, slight rotation). | |||

| Variation: Adjust leaf size and minor imperfections across frames to represent natural variability. | |||

| Damaged | Object: Realistic damaged strawberry leaf, matching the texture of the provided sample image. |  |

|

| Condition: Include brown and black spots (2–5 small to medium spots), yellowing or browning discoloration; small holes (1–2 from pest bites), slight wilting or curling at edges; some leaves with powdery white coating on spots. | |||

| Environment: Plain, neutral gray background (resembling concrete or stone texture). | |||

| Lighting: Vary across frames: soft natural light, bright sunlight with shadows, dim overcast settings. | |||

| Camera: Incorporate movement with slight tilts, pans, and zooms; capture from multiple angles (top-down, side profile, slight rotation). | |||

| Variation: Adjust damage severity (light spotting to moderate rot), hole sizes, edge curling, and powdery coating across frames to represent natural variability. |

Note:

Reference real images were sourced from the PlantVillage dataset (Mohanty, Hughes & Salathé, 2016). To strictly prevent data leakage, all reference images used for generation were excluded from both the validation and test datasets.

Sixteen reference images, one for each video, from the PlantVillage dataset (Mohanty, Hughes & Salathé, 2016) guided the generation process, ensuring realistic leaf textures while maintaining 720p resolution for optimal computational efficiency. For the purposes of this binary classification framework, the classes were defined as “healthy” (showing no visible stress) and “damaged” (encompassing a broad range of symptoms including fungal spots, discoloration, and insect bites, regardless of specific etiology). For each class, eight five-second videos at 30 frames per second were created, producing 150 frames per video which yields 1,200 frames per class.

The quality of the frames was evaluated using FID between synthetic and real images (healthy: 129.1; damaged: 120.68), with lower scores indicating better realism (See Table 2). During frame extraction, an SSIM threshold of 0.95 was empirically selected to filter out redundant frames. Since the generated videos contain smooth camera pans, adjacent frames often possess high similarity; removing frames with an SSIM index effectively reduced near-duplicates, ensuring the final dataset retained only images with distinct viewing angles or lighting shifts. This process yielded 874 healthy and 797 damaged frames.

| Class | FID | Diversity score | SSIM mean | SSIM Std. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy | 129.1 | 0.847 | 0.15 | 0.12 |

| Damaged | 120.68 | 0.800 | 0.19 | 0.09 |

| Overall | – | 0.845 | – | – |

After manual curation to remove blurry or low-quality images, a final training dataset of 739 healthy leaves and 728 damaged leaves was obtained, amounting to 1,467 synthetic images. The final dataset summary is shown in Table 3.

| Subset | Image type | Healthy | Damaged | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training (60%) | Synthetic | 739 | 728 | 1467 |

| Validation (15%) | Real | 194 | 194 | 388 |

| Test (25%) | Real | 309 | 309 | 618 |

Importantly, the sixteen reference images used for Sora prompts were excluded from both validation and test sets to prevent potential evaluation bias and data leakage. The validation and test images are sourced from two public datasets, the PlantVillage dataset and Strawberry Leaves dataset (Mohanty, Hughes & Salathé, 2016; Hariri & Avşar, 2022), a widely used resources for plant disease detection, containing images of strawberry leaves with diseases like powdery mildew and leaf scorch, captured under controlled conditions. The validation set consists of 388 images, while the test set includes 618 real images to assess synthetic-to-real generalization. The combined dataset of 2,473 images (synthetic and real) adheres to an approximate split ratio of 60:15:25 for training, validation, and testing, respectively (See Table 3).

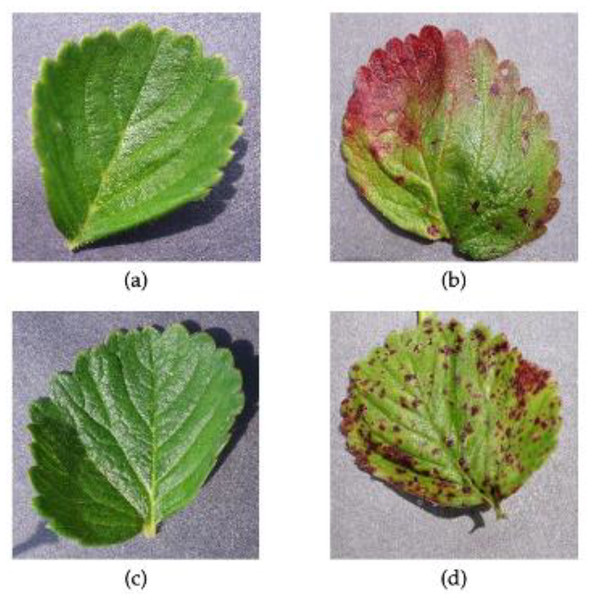

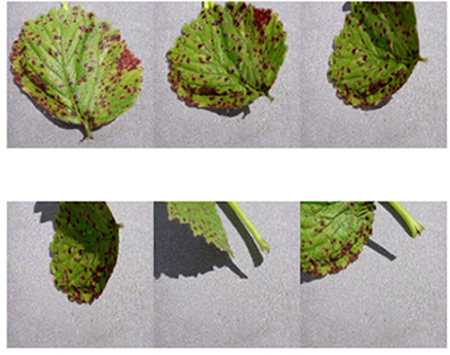

Figure 2 illustrates sample comparisons between real images from the PlantVillage dataset and the Sora-generated synthetic images, visually demonstrating the achieved realism and supporting the evaluation of domain gap metrics in Table 2. Representative samples are shown in Table 1 with diversity score values of 0.85 and 0.8 for healthy and damaged classes, respectively (See Table 2).

Figure 2: Sample images from the PlantVillage dataset for comparison with synthetic outputs to visually assess realism: (A) real healthy strawberry leaf; (B) real damaged strawberry leaf; (C) synthetic healthy strawberry leaf; (D) synthetic damaged strawberry leaf.

In terms of computational efficiency, the generation of each 5-s video sequence required approximately 10 min of processing time. A specific cost analysis is omitted, as this study utilized the older pricing structure of Sora 1 by OpenAI.

Model architectures

While deep neural networks have transformed computer vision, their computational requirements often hinder deployment on edge devices. Lightweight architectures address this challenge through innovative design choices that balance accuracy with efficiency which is beneficial in agricultural applications. Small farmer operations in particular could benefit from them as they can be deployed to edge devices (Thakur et al., 2022). Six leading lightweight models were examined, comparing their performance using synthetic training dataset. The models evaluated were DenseNet-121 (Huang et al., 2017), EfficientNet-B0 (Tan & Le, 2019), MobileNetV3-Small (Howard et al., 2019), ResNet-18 (He et al., 2016), ShuffleNetV2 (Ma et al., 2018), and Vision Transformer-Tiny (Dosovitskiy et al., 2021). They were chosen for their efficiency in resource-limited PA, enabling edge deployment for real-time diagnostics. The models offer a diverse set of architectures, including five CNNs with unique efficiency-focused designs and one ViT, allowing for a robust comparison of architectural strategies for synthetic-to-real generalization.

ResNet-18 uses residual blocks, skip connections, to enable the training of very deep networks without vanishing gradients. DenseNet-121 encourages feature reuse and reduces parameters by connecting each layer to all subsequent layers within dense blocks. For mobile devices, MobileNetV3-Small is highly optimized using efficient inverted residual blocks and Squeeze-and-Excite modules, while ShuffleNetV2 minimizes computational cost with pointwise group convolutions and a channel shuffle mechanism. EfficientNet-B0 introduces a compound method to systematically scale network width, depth, and resolution for a superior balance of accuracy and efficiency. Finally, ViT-Tiny diverges from CNNs by processing an image as a sequence of patches, using a self-attention mechanism to capture global relationships between them.

A summary of the model architectures is shown in Table 4, the layer count for CNNs is defined as the total number of trainable Conv2d and Linear modules, while for ViT, it is the number of transformer encoder blocks. While DenseNet-121 has the most layers, its parameter count is lower than ResNet-18’s due to its feature reuse design. ShuffleNetV2 and MobileNetV3-Small are the most parameter-efficient, making them ideal for mobile use, while ViT-Tiny offers a fundamentally different, attention-based approach to feature extraction.

| Model | Main component | Layers | Parameters (M) | Size (MB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ResNet-18 (He et al., 2016) | Residual blocks | 21 | 11.7 | 44.6 |

| DenseNet-121 (Huang et al., 2017) | Dense blocks | 121 | 8.0 | 30.8 |

| MobileNetV3-Small (Howard et al., 2019) | Inverted residuals | 54 | 2.5 | 9.8 |

| ShuffleNetV2 (1.0x) (Ma et al., 2018) | Channel shuffling | 57 | 2.3 | 8.8 |

| EfficientNet-B0 (Tan & Le, 2019) | MBConv blocks | 82 | 5.3 | 20.3 |

| ViT-Tiny (Dosovitskiy et al., 2021) | Self-attention | 12 | 5.7 | 21.8 |

Training procedure and experimental setup

The models were initialized with weights pre-trained on ImageNet to leverage learned low-level features. The study employed a feature extraction strategy for all architectures (ResNet-18, MobileNetV3-Small, EfficientNet-B0, DenseNet-121, ViT-Tiny, and ShuffleNetV2). In this approach, the backbone weights were frozen to preserve the pre-trained features, and only the final classification head was updated during training. This strategy was selected to evaluate the transferability of generic features to the synthetic strawberry domain without the computational cost of full network retraining.

Hyperparameter decisions were grounded in standard transfer learning practices for plant disease classification (Kingma & Ba, 2015; Aghamohammadesmaeilketabforoosh et al., 2025). An image size of pixels was selected to match the input dimensions of the pre-trained ImageNet weights, facilitating effective feature transfer (Tan & Le, 2019; El-Sakka, Alotaibi & Okasha, 2024). Training was conducted using the CrossEntropyLoss function and the Adam optimizer (Kingma & Ba, 2015) with an initial learning rate of 0.001, chosen for its adaptive properties which promote faster convergence (Sharma et al., 2024). A batch size of 32 was selected to balance computational efficiency on the GPU with gradient stability, consistent with similar studies in leaf disease detection (Shin et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2024; Abbas et al., 2021a).

Training ran for a maximum of 50 epochs with an early stopping mechanism (patience = 7 epochs) monitoring validation loss to prevent overfitting. Preliminary experiments indicated that convergence for the feature extraction task typically stabilized between 30 and 40 epochs, making 50 epochs a sufficient upper bound. On-the-fly data augmentation was applied to the synthetic training set to enhance generalization, including random resize crop, random horizontal flip, random rotation of , and color jitter (brightness, contrast, saturation: 0.2; hue: 0.1). A summary of the hyperparameters is provided in Table 5. The experiments were conducted on Google Colab Pro Plus, utilizing a single NVIDIA A100-SXM4 GPU (40 GB VRAM). The software environment included PyTorch 2.6.0+cu124 and CUDA 12.4.

| Hyperparameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Image input size | 224 × 224 pixels |

| Batch size | 32 |

| Epoch | 50 |

| Patience | 7 |

| Optimizer | Adam |

| Initial learning rate | 0.001 |

| Loss function | CrossEntropyLoss |

Evaluation strategy and performance metrics

The evaluation employed a two-stage approach to assess model generalization from synthetic to real-world images. First, a single-split comparison was conducted of the six lightweight models trained on 1,467 synthetic images and validated on 388 real-world images, with final evaluation on a test set of 618 real strawberry leaf images using consistent hyperparameters. For the top-performing model, 5-fold stratified cross-validation was then performed by combining the training and validation sets, where each fold’s best checkpoint was evaluated on the same 618 image test set, with final metrics averaged across folds to robustly assess generalization capability while balancing computational costs (Anguita et al., 2012). Models performance was evaluated using standard classification metrics derived from the confusion matrix, which organizes predictions into four fundamental categories: true positives (TP), false positives (FP), true negatives (TN), and false negatives (FN) (Sokolova, Japkowicz & Szpakowicz, 2006). This framework enabled comprehensive assessment of predictive performance with Eqs. (1)-(4).

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4)

Results

The baseline comparison was made with six lightweight models using the single-split strategy for training as illustrated in Table 6, with 1,467 train images, 388 validation images, and a test set of 618 images. The same hyperparameters settings for all models ensured an equitable comparison of the generalization ability from synthetic to real data.

| Model | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1-score (%) | Inference speed (ms/img) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EfficientNet-B0 | 95.47% | 95.95% | 95.47% | 95.46% | 0.66 |

| DenseNet-121 | 92.88% | 93.57% | 92.88% | 92.85% | 1.3 |

| MobileNetV3-Small | 97.73% | 97.83% | 97.73% | 97.74% | 0.54 |

| ResNet-18 | 98.71% | 98.74% | 98.71% | 98.71% | 0.26 |

| ShuffleNetV2 | 94.98% | 95.5% | 95.00% | 94.98% | 0.39 |

| ViT-Tiny | 96.28% | 96.29% | 96.28% | 96.28% | 0.37 |

Training dynamics and validation performance

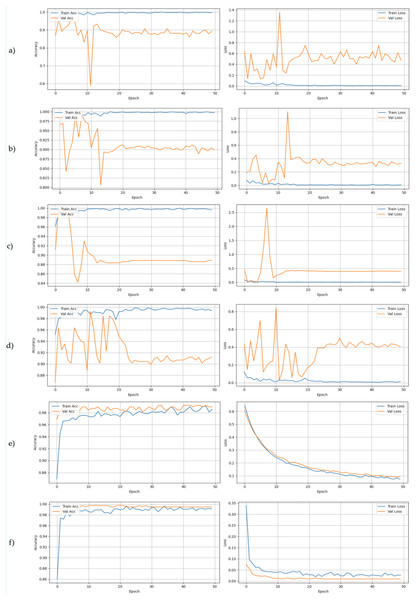

Training histories were analyzed and the differences in learning patterns were observed across architectures, which are shown in Fig. 3. All CNN-based models ResNet-18, MobileNetV3-Small, EfficientNet-B0, DenseNet-121 and ShuffleNetV2 repeatedly converged quickly during training, resulting in earlier peaks and post-overfitting indications. The Vision Transformer (ViT-Tiny) showed quite different movements, as it reached best accuracy on validation of 99.74% in epoch 4 and kept steady from there. This implies evidence of better resistance to overfitting, more stable optimization plateau or better alignment with the synthetic-to-real transfer task. The difference between CNN and transformer dynamics offer a useful perspective for model choice in synthetic-trained systems, in particular on a training time and checkpoint selection.

Figure 3: Training dynamics for the six lightweight architectures over 50 epochs.

The plots display training accuracy (blue) vs validation accuracy (orange) on the left, and training loss (blue) vs validation loss (orange) on the right for each model: (A) DenseNet-121, (B) EfficientNet-B0, (C) MobileNetV3-Small, (D) ResNet-18, (E) ShuffleNetV2, and (F) ViT-Tiny. Notable patterns include the early convergence of MobileNetV3 and the stability of ViT-Tiny compared to the volatility observed in the CNN validation losses.Test set performance and top model analysis

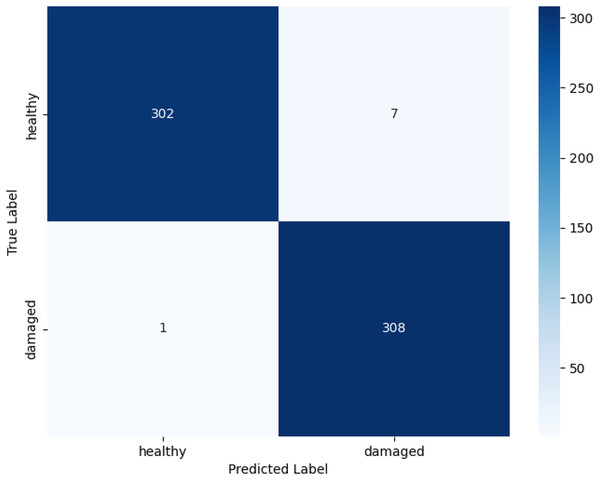

Among the tested architectures, ResNet-18 shows the highest performance, with accuracy of 98.71%, precision of 98.74%, recall of 98.71%, and F1-score of 98.71% (see Table 6 for detailed metrics). It can classify the healthy and damaged classes well as seen in the confusion matrix in Fig. 4. The confusion matrix for ResNet-18 further confirms this, showing only eight misclassifications out of 618 test images, seven healthy leaves incorrectly labeled as damaged and 1 damaged as healthy, demonstrating balanced performance across classes with minimal false positives or negatives. Also, the 0.26 ms/img inference speed indicates that it is deployable to edge devices, which is important for resource constrained farms. MobileNetV3-Small, a lighter architecture, was a close second with an accuracy of 97.73%, and the performances of the other models were 96.28% for ViT-Tiny, 95.47% for EfficientNet-B0, 94.98% for ShuffleNetV2, and DenseNet-121 with 92.88%.

Figure 4: Confusion matrix for ResNet-18.

Statistical significance analysis

Statistical validation using McNemar’s test was performed to assess the significance of the performance difference between the top-performing ResNet-18 and the runner-up MobileNetV3-Small. The analysis focused on discordant pairs where the predictions of the two models disagreed. ResNet-18 correctly classified 10 images that MobileNetV3-Small misclassified, while MobileNetV3-Small correctly classified four images that ResNet-18 missed. The test yielded a p-value of 0.1796, indicating that the difference in predictive performance is not statistically significant ( ) at the 95% confidence level.

K-fold cross-validation assessment

In order to confirm the validity of ResNet-18 performance, which is the best model in the first single-split evaluation, 5-fold stratified cross-validation was performed. For each fold, the optimal model checkpoint was tested on the same 618 real-world images. Remarkably, the cross-validation results showed solid consistency, with ResNet-18 having an average test accuracy of 98.90% ( 0.0070) and average matching F1-score of 98.9% ( 0.0071) with a precision of 98.93% ( 0.0067) and recall of 98.90% ( 0.0070), a summary of the k-fold results is shown in Table 7. Three major insights can be drawn from the cross-validation results. First, the fact that the model performs slightly better than the single-split result (98.71%) demonstrates that the model learned more features after being exposed to real images during the cross-validation. Second, the low standard deviations for all metrics indicate that the model is highly stable and there is no clear difference in the performance regardless of whether it uses particular training subsets in the folds. Third, these strong results greatly boosts confidence in the reliability of ResNet-18 in strawberry leaf classification in a scenario where it is predominantly trained using synthetic data, largely mitigating concerns about data partitioning bias. This extensive validation establishes the superiority not only of ResNet-18, among the tested architectures, but also on its extraordinary generalization capabilities from the synthetic training data to real agricultural imagery.

| Metric | Average score (%) | Standard deviation (+/−) |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 98.9% | 0.007 |

| Precision | 98.93% | 0.0067 |

| Recall | 98.9% | 0.007 |

| F1-score | 98.9% | 0.0071 |

Discussion

The results demonstrate that lightweight DL models, trained exclusively on synthetic video frames of strawberry leaves, can achieve high performance when evaluated on real-world images. In the initial single-split experiment, ResNet-18 achieved 98.71% accuracy on the held-out real test set. This performance was further validated through a 5-fold stratified cross-validation, yielding an average accuracy of 98.9% ( ) and an F1-score of 98.9%. These findings align with and extend a growing body of literature that advocates for synthetic data as a means to augment or replace labor-intensive field data collection.

Statistical analysis and efficiency trade-offs

Although ResNet-18 achieved the highest nominal accuracy, statistical analysis via McNemar’s test revealed no significant difference ( ) between it and MobileNetV3-Small. Considering that MobileNetV3-Small requires approximately fewer parameters (2.5 M vs 11.18 M) and fewer Floating Point Operations per Second (FLOPs) (0.06 G vs 1.82 G), it serves as the most efficient candidate for deployment on resource-constrained edge devices, offering comparable reliability to the heavier ResNet-18 architecture. This finding is particularly relevant for precision agriculture applications where hardware constraints often dictate model selection (Thakur et al., 2022). While ResNet-18 offers the fastest inference speed on the high-end A100 GPU due to parallelization, MobileNetV3’s architectural efficiency makes it better suited for CPU-based or low-power edge hardware.

Efficacy of video-based synthetic data

The high fidelity and consistency of the model performance indicate a substantial narrowing of the domain gap. Unlike static image generation, Sora inherently introduces subtle, frame-to-frame variations in lighting, angle, and leaf position, which simulate the dynamic conditions of a real-world environment. This temporal diversity, curated through the SSIM-based filtering process, likely endows the training dataset with a richer feature distribution than that typically achieved with static GAN-generated images. Notably, this performance was achieved using a feature extraction strategy where the model backbones were frozen. This suggests that the synthetic data possesses sufficiently realistic low-level features to activate pre-trained ImageNet filters effectively, requiring only the retuning of the classification head to adapt to the specific strawberry disease domain.

Comparatively, recent studies using static synthetic data have shown variable success. Nazki et al. (2020) reported accuracy gains using CycleGAN to translate laboratory images to field-like domains, while Mori, Naito & Hosoi (2024) achieved 81.9% accuracy using latent diffusion for unseen classes. By contrast, our approach leveraging temporally coherent video frames achieved results rivaling models trained on conventional real datasets. The superior performance is attributed to the richer spatial-temporal diversity captured in the video frames, which aids the model in learning robust morphological features such as necrotic spots and fungal textures that persist across the domain gap despite FID scores in the 120–130 range.

It is worth noting that the FID scores observed in this study (120–130) are generally higher than those reported for GANs trained directly on specific agricultural datasets, which can achieve scores below 50 (Rahman et al., 2024). This discrepancy is expected, as Sora operates here in a zero-shot capacity without fine-tuning on the target distribution. However, the high classification performance (F1-score of 98.71%) suggests that while pixel-level distribution statistics may deviate from real data, the diffusion model successfully captures the critical semantic features such as lesion morphology and leaf texture necessary for accurate disease identification.

Architectural comparisons

Beyond the top performers, the analysis of other lightweight architectures offers additional insights. ViT-Tiny demonstrated remarkable stability during training, maintaining high validation accuracy with minimal fluctuation compared to the CNN-based models. This suggests that the self-attention mechanisms in Vision Transformers may offer robust generalization from synthetic data, though they did not surpass the peak accuracy of the best CNNs in this specific binary task. Conversely, DenseNet-121 and EfficientNet-B0, while effective, showed higher computational overhead without yielding statistically significant performance gains over the optimized MobileNetV3-Small. The selection of a diverse set of architectures confirms that modern lightweight CNNs are currently the most practical choice for this specific synthetic-to-real transfer task, balancing high accuracy with the efficiency required for field deployment.

Limitations and future work

While this study establishes the potential of video-based synthetic data, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the Sora pipeline currently relies on high-quality real reference images to anchor the diffusion process; without a robust reference, the semantic consistency of the generated strawberry leaves diminishes. This dependency restricts the method’s fully automated scalability compared to purely noise-based generation. Second, although SSIM filtering reduced redundancy, the dataset generation still required manual curation to remove low-fidelity or hallucinatory frames, which introduces a bottleneck for massive-scale data production.

Furthermore, while the videos introduce temporal lighting and angle variations, the synthetic dataset does not yet fully capture the chaotic variability of open-field agriculture, such as complex soil backgrounds, variable weed occlusion, or multi-stage disease progression. Finally, this study focused on a binary classification to establish a baseline; future work will expand this to multi-class identification of specific pathogens and validate the models on crops with different morphological structures to test broader generalization.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that high-fidelity, video-generated synthetic imagery can serve as an effective complement or substitute for large, manually curated datasets in strawberry disease classification. By producing a varied set of synthetic strawberry leaf images with Sora and fine-tuning six lightweight neural networks, performance on real test data was achieved that rivals models trained on conventional datasets. ResNet-18, in particular, delivered accuracy, precision, recall and F1-score all near 98.7%, with 5-fold cross-validation confirming the stability of these results. These outcomes suggest that diffusion-based video synthesis can narrow the domain gap enough to support robust and generalizable models in data-scarce agricultural contexts. The approach might be adaptable to other crops and disease categories, offering a promising pathway to democratize AI tools for precision farming. While further validation in uncontrolled open-field environments is required, these results suggest that synthetic video generation can significantly reduce the reliance on costly field data collection. As generative models continue to advance and edge hardware becomes more capable, the prospect of producing realistic agricultural data on demand could fundamentally change how we build and deploy disease-monitoring systems, opening the door to more resilient and sustainable farming practices.

Supplemental Information

Models used for training on the synthetic dataset.

Each model is used to train, validate the synthetic dataset. Test dataset is used real images to evaluate model performance.