A cross-cultural examination of ethical issues in AI development

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Xiangjie Kong

- Subject Areas

- Human-Computer Interaction, Artificial Intelligence, Emerging Technologies, Security and Privacy, Social Computing

- Keywords

- Human rights, Ethical standards, Ethical perception, Artificial intelligence, Ethics

- Copyright

- © 2026 Eryilmaz

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2026. A cross-cultural examination of ethical issues in AI development. PeerJ Computer Science 12:e3504 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3504

Abstract

This study examines the ethical dimensions of artificial intelligence (AI) and explores the awareness and understanding of how users interact with AI and the potential consequences of these interactions. In recent years, growing awareness of the risks of AI has driven the development of ethical guidelines by various organizations. These guidelines aim to ensure that AI is developed and deployed in a responsible manner, with a focus on human well-being, societal benefits and minimizing risks. However, despite this global movement, there is a lack of consensus on key ethical issues such as bias, discrimination, privacy and human rights issues. The study focuses on the perceptions of 127 participants from 11 countries with diverse professional backgrounds in technology, education and finance. A survey with a 5-point Likert scale was used to assess participants’ attitudes towards AI ethics in relation to various topics such as transparency. The study examines differences in responses across professions and countries using Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) test. The results reveal variations in ethical priorities, suggesting that while global ethical frameworks are emerging, further efforts are needed to achieve uniformity in AI ethical standards. The findings emphasize the importance of increasing awareness and understanding of AI ethics to mitigate potential harms.

Introduction

In recent years, growing awareness of the potential risks posed by artificial intelligence (AI) technologies has led organizations to recognize the need to develop these technologies in an ethical manner. Numerous organizations and initiatives have been established to create ethical guidelines for AI, and many companies have begun to integrate these guidelines into their own AI strategies. This shows that various rules have been developed to prevent AI from producing negative results. Research shows that the AI community has begun to converge on certain ethical principles and practices (European Parliament, 2020; Light & Panai, 2022; Dotan, 2021). This convergence is part of a broader process of systematic and meaningful synchronization of international AI ethics guidelines. Various groups from around the world, including international associations, international standardization bodies such as International Organization for Standardization (ISO)/International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) and Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), and ethical institutions, are involved in this process. This entire structure can be viewed as a complex social system that influences the creation, design, and management of AI systems (Luhmann, 1995).

At the same time, it is important to recognize that artificial intelligence is not a single, uniform technology but a diverse set of systems with distinct functions, applications, and ethical implications. Different forms of AI present unique challenges and moral questions depending on their social roles and interaction contexts. As scholars such as Helfand (2016) and O’Connor & Weatherall (2019) anticipated, the twenty-first century has shifted from an information age to a misinformation age. The dominance of algorithmic media and its growing monopoly on knowledge have made individuals more vulnerable to manipulation, as the Cambridge Analytica case vividly illustrated. The emergence of powerful generative models—accelerated by the release of ChatGPT in late 2022—has heightened these concerns: if anyone can now fabricate anything online using AI tools, how can societies maintain trust, authenticity, and epistemic integrity in digital spaces? (Hyde, 2025). For example, generative AI (such as text-to-image or text-to-video models) raises issues related to authorship, misinformation, and the livelihoods of creative workers. Emotional AI and AI-driven social media systems have been shown to affect users’ emotional well-being, self-perception, and value systems by reinforcing mimetic desires and echo chambers that reshape psychological and ethical frameworks (Valčo, 2024). Recommender algorithms and search engines influence information diversity and public discourse, while agentic AI systems and robots challenge traditional understandings of autonomy and human interaction, extending even to spiritual or religious functions (Puzio, 2025). Distinctions between thinking AI and feeling AI show that emotional and cognitive forms of artificial intelligence can elicit different behavioral and ethical outcomes in human–machine interaction, such as consumer decision-making and trust formation in health-related contexts (Bi et al., 2025). Each of these AI forms interacts with society and culture in distinct ways, generating new ethical dilemmas that range from psychological and social effects to governance and accountability concerns. Recognizing these typologies and their corresponding ethical implications provides a clearer foundation for contextualizing AI ethics. This enables researchers and policymakers to analyze how different AI technologies influence human values, well-being, and societal norms, and to design governance models that balance innovation with human-centered ethical reflection.

Additionally, the lack of understanding and awareness of how users interact with AI and the potential consequences of these interactions leads to further ethical dilemmas. Despite the limited formal regulation, numerous independent initiatives have been launched worldwide to address these ethical challenges. Ethical harms and concerns addressed by these initiatives which agree that the research, development, design, implementation, monitoring and use of AI must be ethical. However, each initiative sets different priorities. Overall, these initiatives aim to define ethical frameworks and systems for AI that prioritize human well-being, promote both societal and environmental benefits (without these goals conflicting), and minimize the risks and adverse impacts associated with AI. The initiatives emphasize the importance of ensuring that AI remains accountable and transparent (Shahriari & Shahriari, 2017; Atalla et al., 2024). The European Parliamentary Research Service’s report, entitled “The Ethics of Artificial Intelligence: Issues and Initiatives” categorizes and outlines the main issues addressed by such initiatives (European Parliament, 2020). According to these ethical initiatives in the field of artificial intelligence, the development, deployment and impact of AI present a wide range of ethical challenges. These challenges include the potential impact on fundamental human rights, data security and privacy concerns, and issues such as bias and discrimination inadvertently built in by a homogeneous group of developers. Limited user awareness and understanding of the use and implications of AI exacerbates these concerns (European Parliament, 2020; Veruggio & Operto, 2006). This study focuses on exploring whether there is a gap in understanding how users from different countries and professional backgrounds interact with artificial intelligence, the potential consequences of these interactions, and their level of awareness regarding AI ethics. The aim of the study is to explore whether the awareness of AI ethics among users interacting with artificial intelligence varies across countries and professions.

Theoretical framework

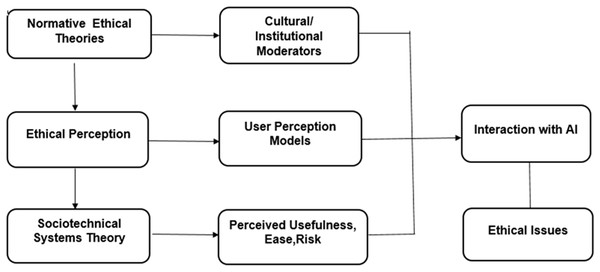

This study utilises an integrated theoretical framework that brings together normative ethical theories, sociotechnical systems thinking and user perception models to examine how individuals perceive and interact with AI in relation to key ethical issues (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Conceptual framework integrating AI ethics perspectives.

The foundation of this framework is normative ethical theories, such as deontology, utilitarianism and virtue ethics (Floridi et al., 2018; Binns, 2018). These theories provide guiding principles for understanding moral expectations related to the use of AI. Deontology emphasises moral duties and rights, particularly in relation to privacy, transparency and human dignity. Utilitarianism focuses on maximising collective welfare while minimising harm and aligns with many global ethical AI guidelines (European Commission, 2019; Shahriari & Shahriari, 2017). The framework also draws on socio-technical systems theory (Trist & Emery, 1973), which views technology and society as co-constitutive systems. It recognises that ethical awareness is shaped not only by individual cognition, but also by institutional structures, professional environments and global discourses. This theory supports the study of cross-cultural and cross-professional variability in the perception of ethical AI.

To better understand users’ interactions with AI, the framework incorporates the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) (Davis, 1989) and the Diffusion of Innovations Theory (Rogers, 2003), which explain how technology acceptance and perception are mediated by factors such as perceived usefulness, ease of use, trust, and social influence. These models help interpret how ethical considerations influence engagement with AI systems.

Finally, Beck’s theory of the risk society (Beck, 1992) contextualises users’ ethical concerns within a broader societal shift towards managing uncertainty and systemic technological risk. This perspective is particularly useful in analysing participants’ concerns about algorithmic bias, surveillance, and rights violations areas that are often at the centre of AI ethics discourse (Eubanks, 2018; Crawford, 2021).

Overall, this multilevel theoretical framework supports a holistic understanding of AI ethics awareness and perception and provides a structured lens through which to analyse participants’ responses in different professional and national contexts.

Method

Sample

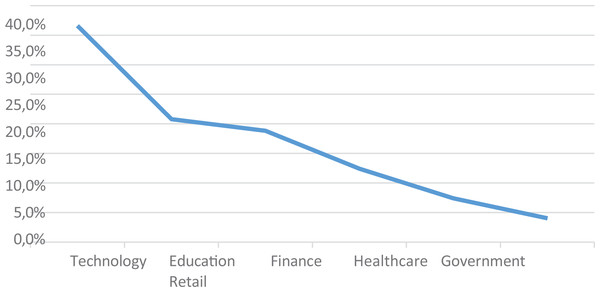

Portions of this text were previously published as part of a preliminary evaluation (CEPIS, 2024). A total of 127 participants 66.1% male, and 33.9% female from 11 countries including Austria, Belgium, England, Germany, Holland, Italy, Ireland, Norway, Poland, Spain, Turkiye participated in this study. According to this, 55.9% are in the 18–24, 14.2% are in the 45–54 year-old range. In terms of sectoral distribution, 36.6% of the survey participants come from the Technology/IT sector, followed by Education (20.8%) and Finance (18.8%) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of survey participants across sectors.

The participants’ professions have been classified as Software Developer/Engineer, Executive/Manager, Researcher/Academician, Data Scientist/Analyst and AI Ethics Specialist.

Data collection tool

The study developed a survey called “Ethical Dimensions of AI” using a 5-point Likert scale to identify priority areas regarding the ethical dimensions of AI. The prepared survey draws on the findings of the European Parliamentary Research Service report entitled “The Ethics of Artificial Intelligence: Issues and Initiatives” and focuses on the perception of the use of AI in different sectors and the main issues associated with ethical concerns. The questions were evaluated on the following topics: Human rights and well-being, Emotional harm, Accountability and responsibility, Security, privacy, accessibility and transparency, Safety and trust, Social harm and social justice, Financial harm, Lawfulness and justice, Control and ethical use, Environmental harm and sustainability, Informed use, Existential risk.

To ensure content validity, the initial version of the survey was evaluated through expert review, involving three academics with expertise in AI ethics and survey methodology, and two professionals from the technology sector. The panel assessed the relevance, clarity, and domain coverage of each item. Based on their suggestions, several items were refined to improve conceptual balance and clarity.

Following expert review, a pilot study was conducted with 75 participants from diverse professional sectors (technology, education, and finance). The feedback collected in the pilot phase helped further refine the wording of some items and assess the instrument’s reliability. The finalized survey showed high internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.98.

The main survey was conducted through Google Forms and shared with participants from Council of European Professional Societies (CEPIS) members. The forms link was distributed to the participants of the member countries in November 2024.

Data analysis

The study focuses on the perceptions of 127 participants from 11 countries with diverse professional backgrounds in technology, education, and finance. The aim of this study is to explore whether the awareness of AI ethics among users interacting with AI varies across countries and professions. Descriptive statistics were used in the analysis of demographic data and Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) test was employed to assess variations in responses among professional groups.

The research questions of the study:

RQ1. Does the awareness of AI ethics among users interacting with artificial intelligence differ across countries?

RQ2. Does the awareness of AI ethics among users interacting with artificial intelligence differ across professions?

Findings

Under the “Human rights and well-being” heading, the majority of participants expressed agreement with the statement Q1: “AI serves the interests of humanity and human welfare” (52% agree, 15% strongly agree, 26% Neutral). Nevertheless, under the “Emotional harm” heading, regarding the statement Q2: “AI degrades the integrity of the human emotional experience,” the majority of participants expressed a neutral (45.7%)response.

Under the “Accountability and Responsibility” heading, the question is: Who is held accountable for AI and under what circumstances do individuals or organizations bear responsibility for the actions of AI systems? 35.4% of participants disagreed with the statement Q3: “Those responsible for AI’s actions are always reachable,” while 32.3% expressed a neutral response.

Under the “Security, privacy, accessibility, and transparency” heading, the question is: How can accessibility and transparency be reconciled with privacy and security when it comes to data and personalization? It appears that the number of participants who agree and disagree with the statement Q4: “Artificial intelligence balances accessibility and transparency with privacy and security, especially when it comes to data and personalization” is roughly equal (28.3% Agree, 28.3% Disagree). The fact that the number of neutral participants (30.7%) is also similar indicates a lack of clear consensus on this issue.

Under the “Safety and trust” heading, the question is: What happens if AI is perceived as untrustworthy by the public or behaves in a way that jeopardizes security? The majority of participants expressed a neutral response (32.3%) with the statement Q5: “If AI is deemed untrustworthy by the public, or acts in ways that threaten the safety of either itself or others, preventive measures are always implemented”. 26% of participants agree with the statement.

Under the “Social harm and social justice” heading, the question is: How can we ensure that AI is inclusive, free from bias and discrimination, and in line with public morals and ethical values? The number of participants who agree, disagree, is roughly equal (27.6%) with the statement Q6: “AI is inclusive, unbiased, and free from discrimination, in line with social morals and ethics.” The result indicates a lack of clear consensus on this issue.

Under the “Financial harm” heading, the question is: How can we prevent AI from negatively impacting economic opportunities and employment by displacing workers or reducing the quality of jobs? it can be seen that the majority of participants disagreed with the statement (32.4%) Q7: “AI negatively impacts economic opportunities and employment,” with many expressing uncertainty on the issue.

Under the “Lawfulness and justice” heading, the question is: How can we ensure that AI and the data it collects is used, processed and managed fairly, equitably and in accordance with legal standards? The majority of participants remained neutral with the statement Q8: “Should AI systems be granted a “personality”? The data collected by AI is used, processed, and managed in a fair, equitable, and legal manner,” and many participants neutral (36.1%), 26.9% of them disagree on the issue.

Under the “Control and ethical use” heading, the question is: How can we protect ourselves from the unethical use of AI? How can AI remain fully under human control, even as it evolves and “learns’? It was observed that the majority of participants remained neutral (35.2), with many also expressing disagreement (26.9%) with the statement Q9:” AI remains under complete human control, even as it develops and ‘learns’. That is why AI can be used ethically.

Under the “Environmental harm and sustainability” heading, the question is: How can we protect ourselves from the potential environmental damage associated with the development and use of AI? How can AI be produced sustainably? The majority of participants expressed agreement (36.1%) with the statement Q10: “We can be protected against the potential environmental harm associated with the development and use of AI.”

Under the “Informed use” heading, the question is: What measures can be taken to ensure that the public is informed and educated about the handling and use of AI? The majority of participants disagreed (33.3%) and 24.1% strongly disagreed with the statement Q11: “The public is aware, educated, and informed about their use of and interaction with AI,” indicating a need for further education on the topic.

Under the “Existential risk” heading, the question is: How can we prevent an AI arms race, mitigate potential damage early and ensure that advanced machine learning progresses in a way that is both innovative and controllable? The majority of participants remained neutral (44.1%) while a high percentage expressed a positive view on the statement Q12: “AI pre-emptively mitigates and regulates potential harm. Advanced machine learning is both progressive and manageable.”

After finding the averages of the general responses to the 12 questions, MANOVA was used to analyze the research questions.

Assumption check–normality

Multivariate normality is a key assumption for conducting MANOVA. To assess this, Shapiro-Wilk tests were applied to each of the twelve dependent variables (Q1–Q12). The results indicated that the normality assumption was met for all items (p > 0.05), suggesting that the data are suitable for multivariate analysis (Table 1).

| Question | W statistic | p-value | Normality assumption met |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | 0.968 | 0.092 | Yes |

| Q2 | 0.973 | 0.135 | Yes |

| Q3 | 0.981 | 0.222 | Yes |

| Q4 | 0.962 | 0.071 | Yes |

| Q5 | 0.975 | 0.144 | Yes |

| Q6 | 0.984 | 0.259 | Yes |

| Q7 | 0.971 | 0.112 | Yes |

| Q8 | 0.977 | 0.162 | Yes |

| Q9 | 0.970 | 0.102 | Yes |

| Q10 | 0.979 | 0.208 | Yes |

| Q11 | 0.968 | 0.089 | Yes |

| Q12 | 0.982 | 0.230 | Yes |

Effect size calculation

Meeting the assumption of normality supports the reliability of the MANOVA results and ensures the validity of group comparisons. Therefore, the MANOVA results addressing the research questions were considered valid and interpreted accordingly, including the reporting of associated effect sizes (η2) to evaluate the practical significance of group differences.

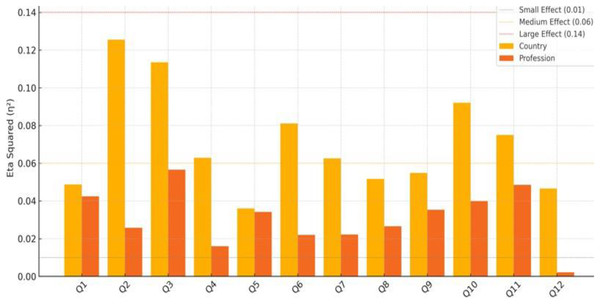

To assess the practical significance of group differences, eta squared (η2) values were calculated for each item in relation to both country and profession. The results indicated that country-level differences exhibited moderate effect sizes particularly on emotional harm (Q2; η2 = 0.125) and accountability (Q3; η2 = 0.113). Similarly, profession-related differences showed small to moderate effect sizes, with accountability (Q3; η2 = 0.056) being the most notable. These findings suggest that certain ethical dimensions of AI, such as emotional impact and responsibility, are perceived differently across national and professional contexts, reinforcing the importance of considering sociocultural and occupational factors in AI ethics research (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Eta-squared (η2) effect sizes by country and profession.

Following these methodological enhancements, the research questions (RQ1 and RQ2) were addressed using MANOVA to examine whether participants’ awareness of AI ethics significantly differed across countries and professional groups. The results are presented in the revised Findings section, along with interpretations based on effect sizes and the theoretical framework.

RQ1. Does the awareness of AI ethics among users interacting with artificial intelligence differ across countries?

According to the MANOVA results in the Table 2, four different multivariate statistical results for the group variable were found to be statistically significant at the 0.05 level. Based on this, it can be concluded that there is a significant difference between the groups (countries) (p < 0.05) based on the following questions: Q6, Q7, Q8, Q9, Q11. Additionally participants from Norway expressed the strongest agreement with the statement Q2: “AI degrades the integrity of the human emotional experience”, indicating heightened concerns about emotional harm. In contrast, participants from the Italy and Austria reported the lowest, suggesting minimal concern. Respondents from Turkiye and Italy showed the highest agreement with Q4: “AI balances accessibility and transparency with privacy and security.” Conversely, participants from the England and Germany exhibited the lowest agreement highlighting concerns about data security and transparency in these regions.

| Effect | Value | F | Hypothesis df | Error df | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | Pillai’s Trace | ,839 | 296,485b | 2,000 | 114,000 | ,000 |

| Wilks’ Lambda | ,161 | 296,485b | 2,000 | 114,000 | ,000 | |

| Hotelling’s Trace | 5,201 | 296,485b | 2,000 | 114,000 | ,000 | |

| Roy’s Largest Root | 5,201 | 296,485b | 2,000 | 114,000 | ,000 | |

| YourCountry | Pillai’s Trace | ,319 | 1,984 | 22,000 | 230,000 | ,007 |

| Wilks’ Lambda | ,699 | 2,035b | 22,000 | 228,000 | ,005 | |

| Hotelling’s Trace | ,406 | 2,086 | 22,000 | 226,000 | ,004 | |

| Roy’s Largest Root | ,330 | 3,448c | 11,000 | 115,000 | ,000 | |

RQ2. Does the awareness of AI ethics among users interacting with artificial intelligence differ across professions?

According to the MANOVA results in the Table 3, four different multivariate statistical results for the group variable were found to be statistically significant at the 0.05 level. Based on this, it can be concluded that there is a significant difference between the groups (job titles) (p < 0.05) based on the following questions: Q6, Q7, Q8, Q11, Q12.

| Effect | Value | F | Hypothesis df | Error df | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | Pillai’s Trace | ,846 | 163,522b | 4,000 | 119,000 | ,000 |

| Wilks’ Lambda | ,154 | 163,522b | 4,000 | 119,000 | ,000 | |

| Hotelling’s Trace | 5,497 | 163,522b | 4,000 | 119,000 | ,000 | |

| Roy’s Largest Root | 5,497 | 163,522b | 4,000 | 119,000 | ,000 | |

| JobTitleRole | Pillai’s Trace | ,306 | 2,524 | 16,000 | 488,000 | ,001 |

| Wilks’ Lambda | ,719 | 2,590 | 16,000 | 364,189 | ,001 | |

| Hotelling’s Trace | ,355 | 2,610 | 16,000 | 470,000 | ,001 | |

| Roy’s Largest Root | ,189 | 5,779c | 4,000 | 122,000 | ,000 | |

According to the profession (job titles) perceive various ethical aspects of artificial intelligence (AI) the key findings derived from the data:

Software Developers/Engineers reported the highest agreement with the statement “The data collected by AI is used, processed, and managed in a fair, equitable, and legal manner”. AI Ethics Specialists and Data Scientists displayed the most skepticism, reflecting concerns about transparency and fairness in data use. Researchers and academics tend to hold moderate views on ethical aspects, while engineers exhibit a more optimistic outlook. AI Ethics Specialists consistently showed critical views across multiple statements, emphasizing the need for more robust ethical frameworks.

Gender and age insights

The analysis revealed no statistically significant differences between genders for most questions. This suggests that gender does not play a major role in shaping perceptions of AI ethics in this dataset.

Age differences

Some questions, such as “AI serves the interests of humanity and human welfare,” showed moderate variation across age groups, but no definitive trend was observed.

Agreement on AI’s benefits

Participants generally agreed that AI has the potential to serve humanity and promote transparency in decision-making. However, concerns about emotional harm, transparency, and inclusivity were noted in several regions and professions.

Skepticism in specific domains

There was widespread neutrality or disagreement on whether AI ensures accountability or operates without bias, suggesting the need for stronger governance mechanisms and public trust-building.

Limitations

While this study provides valuable insights into cross-cultural perceptions of AI ethics, several limitations should be acknowledged to contextualize the findings and inform future research.

Sample size and statistical power

Although the study includes participants from 11 countries, the total sample size (N = 127) limits the statistical power of the analysis. In particular, some countries and professional groups are represented by smaller subsamples, which may affect the robustness of the MANOVA results. While normality assumptions were met and effect sizes were reported to enhance interpretive validity, caution is warranted when generalizing the findings. Future studies would benefit from larger and more balanced samples to strengthen statistical inference and subgroup comparisons.

Sampling and representation

The participant pool was recruited primarily through the Council of European Professional Informatics Societies (CEPIS) and may not represent the full diversity of cultural or professional perspectives on AI ethics. Furthermore, because the survey was distributed online, participants were limited to those with internet access and professional affiliations, potentially excluding broader populations. This introduces a degree of selection bias that should be considered when interpreting the results.

Methodological scope and statistical approach

The study uses a frequentist MANOVA framework. Although appropriate for the research questions, alternative approaches—such as Bayesian multivariate analysis—may offer advantages in terms of flexibility and robustness, particularly with small or imbalanced samples. This is noted as a potential direction for future work.

The study did not explicitly incorporate culturally grounded theories in the survey design or analytical modeling. Given the observed cross-cultural differences, future research would benefit from culturally sensitive instruments and analytical frameworks that account for normative, contextual, and linguistic diversity.

Discussion

The results show a complex and multi-layered picture of artificial intelligence, reflecting varying degrees of confidence, concern and neutrality on key issues. While the majority of participants recognize the potential of AI to serve the interests and wellbeing of humanity, as evidenced by their agreement in the “Human rights and wellbeing” section, significant neutrality can be observed in areas such as “Emotional harm,” “Safety and trust” and “Legality and justice”. This neutrality indicates uncertainty or ambivalence about the broader societal and ethical implications of AI. In areas such as “accountability and responsibility” and “control and ethical use” many participants expressed disagreement or neutrality, indicating concerns about the accessibility of those responsible for AI actions and doubts about the compliance of AI with human control and ethical standards. There is also no consensus on the topics of “security, privacy, accessibility and transparency” and “Social harm and social justice”, which underlines the need for a clearer framework for balancing these priorities. Interestingly, opinions on “environmental harm and sustainability” are positive, with the majority of respondents recognizing the potential of AI to mitigate environmental harm. However, the high level of disagreement on “informed use” indicates an urgent need for public education on the use and interaction of AI. Furthermore, views on “existential risk” reflect optimism about AI’s ability to manage and regulate potential harms, although neutrality still prevails.

Intercultural differences in ethical issues

The results reveal clear cultural contrasts in perceptions of AI’s ethical implications. Norwegian respondents expressed heightened concerns about AI’s potential to compromise emotional integrity, reflecting cultural sensitivities toward psychological privacy and emotional autonomy. This finding aligns with prior studies emphasizing the role of cultural context in shaping ethical perceptions (Liu et al., 2024). Their heightened concern about AI’s potential to compromise emotional integrity may reflect the country’s strong cultural emphasis on privacy, emotional autonomy, and human dignity. Norway’s social values—characterized by individualism, egalitarianism, and high trust in transparent governance—foster sensitivity toward technologies perceived as intrusive in psychological or affective domains. This cultural orientation, along with ongoing national debates on digital ethics and emotional privacy, likely explains the greater ethical caution observed among Norwegian participants.

In contrast, participants from Italy and Austria displayed lower levels of concern, suggesting a more pragmatic or optimistic outlook on AI integration. The comparatively pragmatic or optimistic outlook observed among participants from Italy and Austria is thought to be influenced by cultural and institutional factors. Both countries show relatively high levels of institutional trust and strong traditions of social dialogue among government, academia, and industry—conditions that often reduce public anxiety about emerging technologies (Eurobarometer, 2023; Hofstede, 2011). Additionally, Austria’s well-established Industrie 4.0 framework and Italy’s proactive national AI strategy foster the perception that AI integration is manageable and beneficial when supported by transparent governance and human oversight. These factors may explain why participants from Italy and Austria expressed lower ethical concern, reflecting confidence in institutional mechanisms for regulating AI rather than skepticism toward the technology itself.

These patterns highlight that cultural frameworks strongly mediate how societies perceive both the risks and opportunities of AI, underscoring the need for culturally informed approaches to AI governance (Robinson, 2020).

Professional perspectives and ethical skepticism

Professional roles also shape ethical perspectives in distinct ways. AI ethicists and data scientists were more skeptical about the fairness and transparency of AI systems, consistent with their professional focus on identifying risks and unintended consequences (Shneiderman, 2020). Conversely, software developers and engineers expressed greater optimism, likely reflecting their hands-on engagement with building and deploying AI technologies. This divergence illustrates how occupational perspectives can lead to different ethical priorities, reinforcing the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration, where critical scrutiny and technical expertise are combined to address AI’s complex ethical challenges (Weidener & Fischer, 2024).

While AI systems can greatly enhance human cognition and efficiency, they also raise concerns about the gradual erosion of collective wisdom and moral reflection. The pursuit of technological optimization may lead to an “automation of virtue,” in which ethical judgment is replaced by algorithmic reasoning (Vallor, 2016). This trend risks diminishing human imagination, empathy, and the shared moral dialogue that sustain democratic societies. It is essential that AI integration be guided not only by intelligence-oriented metrics but also by human wisdom, ensuring that technology remains a tool for moral growth rather than a substitute for it (Danaher, 2019).

Trust and accountability in different contexts

Participants’ neutral or skeptical views on whether AI can balance transparency and privacy reflect global debates on data governance and accountability. These findings echo concerns raised by the European Parliamentary Research Service, which has emphasized the ethical and moral dilemmas arising from AI development and the urgency of establishing robust governance frameworks (European Parliament, 2020). At the same time, trust should be understood as more than a technical or utilitarian concept. From the perspective of the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), trust may stem from perceived usefulness and ease of use; however, this instrumental view is insufficient to explain broader societal dynamics. Drawing on Beck’s Risk Society (Beck, 1992), trust in AI can be seen as a collective negotiation of uncertainty and systemic risk.

The observed cross-country variation further suggests that trust in AI is not universal but highly context-dependent: different societies prioritize ethical concerns according to their cultural values, institutional traditions, and prior experiences with digital technologies (Karami, Shemshaki & Ghazanfar, 2024). In societies with strong and transparent governance, citizens tend to view AI as an extension of reliable institutions rather than as an external, potentially threatening force (Floridi et al., 2018). Conversely, in contexts where institutional trust is lower or past experiences with digitalization have led to social inequalities, AI is more likely to be met with skepticism or ethical concern. Cultural dimensions such as uncertainty avoidance and long-term orientation (Hofstede, 2011) also influence whether AI is seen as an opportunity for progress or as a source of risk. Thus, differences in trust reflect deeper socio-cultural mechanisms that mediate how ethical principles are interpreted and applied across societies.

In this sense, a lack of transparent and inclusive governance risks producing a “tragedy of the commons,” where short-term gains from AI adoption undermine long-term public confidence in digital systems. This underscores the urgent need for AI policies that are globally aligned yet locally sensitive, combining international standards with culturally embedded governance frameworks to sustain trust, safeguard human dignity, and ensure the responsible integration of AI into society.

Beyond the classic “tragedy of the commons,” AI-driven technologies have created new forms of collective dilemmas. Scholars describe a “tragedy of the AI commons,” where large-scale use of shared data and models leads to overexploitation of public resources and ethical externalities without adequate governance. Similarly, research on the attention economy shows how AI-enabled digital platforms turn human attention into a scarce collective resource, resulting in cognitive overload, polarization, and democratic erosion. These discussions indicate that ethical frameworks must go beyond individual responsibility to address the systemic risks AI poses to shared social and cognitive environments (LaCroix & Mohseni, 2022; Michel & Gandon, 2025).

Implications for governance and policy

These findings suggest several implications for AI governance and policy:

Localized policy frameworks: Countries should develop AI regulations that address specific cultural and ethical concerns and ensure that policies are in line with local values and fears (Osasona et al., 2024). Professional training and ethical awareness: There is an urgent need for comprehensive ethical training for AI practitioners to bridge the gap between technical development and ethical considerations (Pant et al., 2024). Global Collaboration for Standardization: Establishing international standards for AI ethics can help harmonize practices across borders, facilitating the responsible development and deployment of AI technologies worldwide (Erdélyi & Goldsmith, 2022).

Recent advances in emotional artificial intelligence (Emotional AI) highlight how AI systems interact with deeply personal human experiences such as emotions, identity, and well-being. Emotional AI not only promises increased attention and productivity but also raises ethical questions regarding manipulation, emotional surveillance, and behavior modification. Studies propose that the acceptance of such emotionally aware AI systems is shaped by both utilitarian perceptions (ease of use, usefulness as formalized in the TAM) and moral intuitions (as reflected in Moral Foundation Theory, MFT). Drawing on a Three-Pronged Approach—Contexts, Variables, and Statistical Models—this framework helps explain why individuals from different cultural backgrounds perceive ethical risks differently (Ho, Mantello & Ho, 2023).

Specifically, the degree of AI acceptance may increase when users perceive tangible benefits, but may decrease sharply when the technology is perceived as threatening local moral norms (e.g., sanctity of the emotional self or communal privacy values). This framework could be especially valuable in interpreting our cross-cultural findings. For example, the heightened concern about emotional harm in Norway may reflect culturally reinforced sensitivities to emotional autonomy and psychological privacy dimensions aligned with the “harm/care” and “sanctity/degradation” foundations in MFT. In contrast, countries like Austria and Italy, showing lower concern, may prioritize pragmatic utility or institutional control over emotional sovereignty.

Integrating such frameworks into future studies could enrich our understanding of how cultural worldviews shape AI ethics perceptions. Furthermore, this suggests that survey instruments and analytical models must be designed with cultural sensitivity, accounting not only for demographic variables but also for culturally embedded moral reasoning. This study, while integrating normative ethical theories and sociotechnical perspectives, would benefit from future expansions that incorporate culturally grounded models like the one proposed in the Emotional AI literature.

Conclusion

This study highlights the intricate interplay of cultural, professional, and contextual factors in shaping ethical perceptions of AI. Acknowledging these diverse perspectives can support the development of AI systems that are not only technologically robust but also ethically aligned and culturally appropriate. The findings reinforce the urgent need for transparency, ethical literacy, and public trust to address the ongoing concerns and ambiguities associated with AI. Moving forward, enhancing accountability structures, investing in public awareness, and fostering inclusive policy dialogues will be essential to maximizing the societal benefits of AI while minimizing its potential harms. In summary, despite the limitations discussed above, the study provides a set of valuable contributions to the growing literature on AI ethics. The originality and strengths of this study can be summarized as follows:

By collecting data from participants across 11 different countries, the study provides a rare cross-cultural lens on ethical perceptions of AI. This broad scope enables the identification of cultural nuances and national-level differences in ethical concerns. The research distinguishes itself by comparing the views of participants from diverse professional backgrounds including software developers, ethicists, academics, and data scientists thus revealing how ethical perspectives vary depending on occupational engagement with AI. It explores a wide range of ethical dimensions (e.g., emotional harm, privacy, accountability, environmental sustainability), offering a holistic view rather than focusing on a single issue. This comprehensive scope enhances the relevance of the findings for policy, practice, and academia. It incorporates an integrated theoretical approach combining normative ethics, sociotechnical systems theory, and user perception models, providing a conceptual grounding for interpreting results and aligning them with broader ethical discourses. The findings offer practical insights for AI governance and regulation, such as the importance of culturally localized policy frameworks, the need for ethical training in technical fields, and the value of global standards for responsible AI development.