LGCFPEL: local-global correlation fusion for probabilistic collective entity linking

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Ankit Vishnoi

- Subject Areas

- Artificial Intelligence, Data Mining and Machine Learning, Natural Language and Speech, Social Computing, Sentiment Analysis

- Keywords

- Heterogeneous information network, Collective entity linking, Local-global correlation fusion, Probabilistic modeling

- Copyright

- © 2026 Liu et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2026. LGCFPEL: local-global correlation fusion for probabilistic collective entity linking. PeerJ Computer Science 12:e3501 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3501

Abstract

Entity linking, as a key technology for heterogeneous information networks modeling and semantic knowledge retrieval, has attracted significant attention. However, current entity linking methods suffer from three main limitations: (1) They generally rely on a single type of information from the network (e.g., short-path relationships or knowledge representations), leading to insufficient utilization of information and incomplete extraction of both similarity and difference features among entities. (2) They frequently employ deep learning approaches, which lack interpretability. (3) They often depend on additional information from third-party bases, which limits their applicability in some domains’ scenarios. To solve these problems, this article innovatively proposes a probabilistic entity linking method that does not rely on external knowledge bases—Local-Global Correlation Fusion for Probabilistic Collective Entity Linking (LGCFPEL). Specifically, LGCFPEL first constructs a probabilistic model to solve for the optimal linked entities. Second, it treats all entity mentions in a text as a whole for collective linking. Third, it skillfully avoids the direct computation of entity mentions’ correlation by transforming the problem into calculating correlation among their candidate entities. Finally, LGCFPEL builds a local-global fusion correlation metric model based on short-path relationships and knowledge representation learning, simultaneously capturing both local and global features of entities to highlight the tight contextual relationships among different entities. Experimental results indicate that LGCFPEL demonstrates competitive performance with both classical and state-of-the-art models in entity linking performance.

Introduction

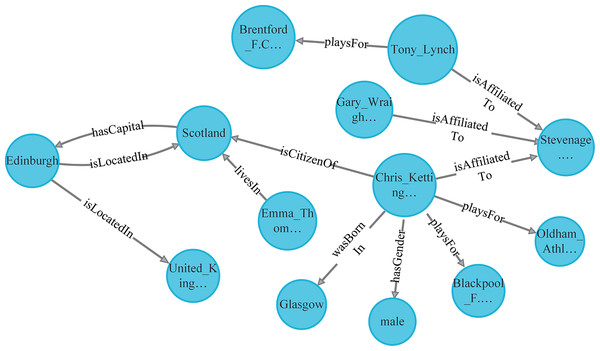

In the era of information explosion, the effective organization and efficient retrieval of knowledge have become key driving forces for technological advancement and industrial upgrading. Heterogeneous Information Networks (HINs) (Forouzandeh et al., 2023), as a structured knowledge representation method based on entity-relation-entity triples, have emerged as an important tool for knowledge representation and reasoning due to their ability to model multi-typed entities and relations. Knowledge graphs (Liu, Lin & Sun, 2023; Zhong et al., 2023), as the primary manifestation of HINs, have achieved remarkable success in various fields, including healthcare and the internet (Gong et al., 2021; Yahya, Breslin & Ali, 2021; Shao, Li & Bian, 2021). For instance, YAGO2 (Huang et al., 2016), a typical HIN, contains over 200,000 entity types and more than 100 relation types, forming a complex knowledge network that provides an intuitive and clear description of the architecture of knowledge systems, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Partial framework of YAGO.

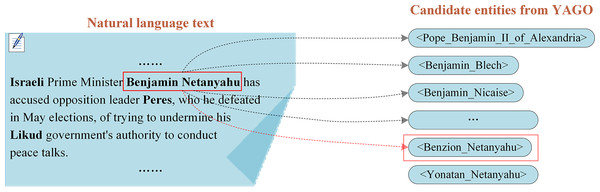

Some entities and their relations in YAGO.Entity linking technology, as a core component of HIN modeling and knowledge retrieval (Rao, McNamee & Dredze, 2013), achieves knowledge query localization by matching named entities in user queries with entities in knowledge bases. It is important to note that: (1) Entity Linking focuses on linking mentions in unstructured text to corresponding entities in the knowledge base, thereby establishing semantic associations between text and the knowledge base; (2) Entity Alignment (Xiao et al., 2025; Li et al., 2024; Zhou et al., 2025; Cheng et al., 2025; Wang et al., 2025), in contrast, deals with entity mapping between different knowledge bases, aiming to expand and integrate knowledge through cross-knowledge-base alignment. With the rapid development of natural language processing and HIN, the role of entity linking in knowledge query (Banerjee et al., 2020; Shen et al., 2021), knowledge reasoning (Zhou et al., 2023; Tian et al., 2022), and knowledge recommendation (Palumbo et al., 2020; Sevgili et al., 2022) is becoming increasingly significant. Typically, entity linking consists of two main steps: candidate entity generation and candidate entity ranking (Chatterjee & Dietz, 2022; Zhang et al., 2023; Hou et al., 2023). Candidate entity generation aims to produce possible candidates for the target mentioned in the query, while candidate entity ranking seeks to identify the candidate most likely to represent the same entity as the query target. For example, for the entity mention “Benjamin Netanyahu” in Fig. 2, a search in YAGO2 yields 101 related candidate entities. The goal of entity linking is to identify, among these 101 candidates, the one that represents the same object as the mention “Benjamin Netanyahu”. The definition of entity linking highlights its critical role in fields such as knowledge retrieval, reasoning, and recommendation.

Figure 2: An example of entity mention linking to YAGO.

The entity mention “Benjamin Netanyahu” link to the entity “<Benjamin_Netanyahu>” in YAGO.Based on the characteristics of feature extraction, entity linking techniques can be categorized into independent entity linking and collective entity linking (Al-Moslmi et al., 2020). Following the human cognitive process from local to global, early research primarily focused on independent entity linking. For instance, Onoe & Durrett (2020) proposed a fine-grained entity type approach for domain-independent entity linking, which formulates entity linking as a pure entity typing problem, addressing the overfitting issue to specific domain entity distributions. De Cao et al. (2010) introduced GENRE, the first system that retrieves entities by generating their unique names token-by-token in an autoregressive manner, conditioned on the context. Procopio et al. (2022) proposed enhancing Wikipedia titles with their descriptions in Wikidata to achieve entity linking. Independent entity linking methods, which do not compute correlation between mentions, exhibit low computational complexity and are more suitable for large-scale knowledge bases. However, their accuracy is often limited due to the neglect of inter-entity relationships.

In contrast, collective entity linking places greater emphasis on global relational information among entity mentions (e.g., co-occurrence relationships, logical dependencies). By simultaneously considering the correlation among multiple entity mentions, it improves the accuracy and consistency of entity linking. For example, Chang et al. (2010) performed entity linking by constructing a dictionary. Han, Sun & Zhao (2011) proposed a graph-based method that models global interdependencies among different entity linking decisions. To capture global contextual information for entity disambiguation (ED), Yamada et al. (2022) proposed a bidirectional encoder representation from transformers (BERT)-based global entity disambiguation model. Bienvenu, Cima & Gutiérrez-Basulto (2022) presented a new logical framework for entity resolution which employs declarative specifications to handle complex collective entity resolution settings, while ensuring that all merges can be justified. Belalta, Belazzoug & Meziane (2024) presented a novel algorithm based on a graph approach and semantic relatedness for collective entity disambiguation. It is worth noting that while current collective entity linking methods significantly improve linking accuracy by considering inter-entity relationships, they also introduce higher computational complexity. Furthermore, the development of collective entity linking methods is also constrained by insufficient extraction of local features of entities and the need for more knowledge.

Entity linking in certain specific domains (e.g., ultra-precision equipment disassembly, military applications) demands higher accuracy, necessitating the study of collective entity linking. In summary, existing methods exhibit three main issues in some domains’ applications:

(1) Regarding the balance between global and local features: Most current neural network-based entity linking methods over-rely on global positional features of entities in heterogeneous information networks while neglecting the strong correlations embodied in short-path connections (i.e., local features). It is noteworthy that heterogeneous information networks are modeled through relationships, shorter paths between entities indicate stronger correlations.

(2) Concerning model interpretability: The decision-making process of neural network models is difficult for humans to intuitively understand or trace, resulting in neural network-based entity linking methods being perceived as black-box operations with poor interpretability. Consequently, many domain experts remain skeptical about neural network approaches and instead focus on developing mathematically or physically interpretable models.

(3) Most existing methods rely on external knowledge bases (such as Wikipedia) to supplement entity information, incorporating these additional data as entity features during the linking process (Shen et al., 2013; Guo, Chang & Kiciman, 2013; Blanco, Ottaviano & Meij, 2015). While this approach can improve linking accuracy to some extent, its performance tends to be limited when handling specialized entities that are not adequately covered in general knowledge bases. The method proposed in this article effectively reduces the dependency on comprehensive external knowledge by extracting as much information as possible about entities from existing knowledge bases, thereby enhancing the capability to handle specialized entities while maintaining general applicability.

To address the aforementioned issues, this article proposes a novel Local-Global Correlation Fusion for Probabilistic Collective Entity Linking (LGCFPEL) method. First, LGCFPEL ensures interpretability by constructing a probabilistic model to solve for the optimal linking results. Second, it treats all entity mentions in a text as a whole during entity linking, simplifying the model-solving process by transforming the problem into calculating correlation among candidate entities of different mentions rather than directly computing correlation between the mentions themselves. Third, it is the first method to combine path-based information around entities with deep semantic information to highlight both local and global features of entities. Finally, LGCFPEL builds a local-global fusion correlation metric model to complete the probabilistic model-solving process and evaluates the effectiveness of entity linking using precision, recall, and F1-score. The contributions of this article are as follows:

Proposes a probabilistic collective entity linking method with strong interpretability and no reliance on external knowledge bases. To align the modeling process more closely with human cognitive processes, the method treats all entity mentions in a text as a whole to construct a probabilistic model for the entity linking objective function, and solves the objective function based on entity correlation. As a result, the model better reflects the actual entity linking process and improves linking accuracy.

Skillfully avoids the direct computation of correlation between entity mentions by transforming the problem into capturing correlation among candidate entities through the HIN. This optimization simplifies the solving of the collective entity linking objective function and addresses the challenge of quantifying correlation among multiple entity mentions in collective entity linking methods.

Constructs a local-global fusion entity correlation metric model that simultaneously extracts both local and global features of entities. The model integrates short-path information around entities with global information from knowledge representation learning, improving the utilization of limited information. Specifically, the model uses the network structure surrounding entities as their local features. The model employs knowledge representation learning models to extract potential deep semantic relationships between entities as their global features.

To validate the effectiveness of the model, experiments are conducted on a real-world heterogeneous information network (YAGO) and three manually annotated web documents. Compared to baseline models, the proposed model achieves the highest entity linking accuracy, recall, and F1-score.

The organization of this article is as follows. ‘Related Work’ summarizes the related work of this article. ‘Preliminaries and Notation’ provides a detailed explanation of the LGCFPEL modeling process. ‘Local-Global Correlation Fusion for Probabilistic Collective Entity Linking Method’ presents experimental results and analysis. ‘Collective Entity Linking Experiment’ concludes this article.

Related work

Collective entity linking methods can be categorized into rule-based (Huang et al., 2014; Jha, Röder & Ngonga Ngomo, 2017), machine learning-based (including deep learning-based) (Fang et al., 2019; Oliveira et al., 2021), graph-based (Guo et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2020), and probability-based methods (Wang et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2019), depending on the models they employ. Rule-based methods rely on manually crafted rules for entity recognition and linking, which often lack flexibility and generalizability. Machine learning-based methods typically require large amounts of annotated data for model training and can adapt to various types of entities and contexts, including the increasingly popular deep learning algorithms in recent years. Graph-based methods transform the entity linking problem into a graph matching task and solve it by identifying the optimal match within the graph. Probability-based methods, on the other hand, establish probabilistic models for entity linking by considering factors such as entity prior probabilities, contextual information, and inter-entity correlation. Notably, compared to other approaches, probability-based methods not only possess a solid mathematical foundation but also can uncover dependency relationships between entities, addressing the issue of poor interpretability in linking models. Moreover, since the modeling process aligns with human cognitive processes, these methods demonstrate higher reliability and effectiveness. Given these advantages, the authors have conducted a comprehensive survey of recent probability-based entity linking methods.

In certain specific domains, the resources available for entity linking are limited, yet there is a higher demand for reliability. Consequently, probability-based entity linking methods have become a current research focus due to the comprehensive theoretical solution process and high accuracy in entity linking. To extract information from HIN, Shen, Han & Wang (2014) were the first to link named entities in Web texts with knowledge graph to the first probabilistic model to link the named entity Sin Web text with a HIN. To further accurately solve the entity linking objective function, Shen et al. (2017) established a general framework for linking named entities in Web free text with a HIN (SHINE+) by utilizing the linked model mapping’s mentioned context information with high confidence. To address the insufficient utilization of entity type, entity and relation intrinsic information in SHINE+, Li et al. (2021) were the first to combine the “global-first” cognitive mechanism of the human brain with entity linking, proposing acoarse-to-fine collective entitylinking algorithm (CFEL). Abdurxit, Tohti & Hamdulla (2022) proposed a probabilistic model to obtain the similarity score between a candidate entity and an entity reference item by multiplying the probability of occurrence of the candidate entity by the probability of the particular entity being represented as an entity reference item. To accurately capture the overall relatedness of multiple entity mentions to their respective candidate entities, Zu et al. (2024b) proposed a collective entity linking method based on strong correlation sequences (SRSCL), achieving more precise entity linking. To accurately extract local information of entities, Zu et al. (2024a) proposed proposes a novel collective entity linking method based on complex relationship path.

Currently, research on probability-based entity linking methods for HINs remains limited, particularly in the domain of collective entity linking. Although innovative models such as CFEL and SRSCL have demonstrated strong performance in entity linking, they exhibit certain limitations. For instance, CFEL considers only a single 2-hop path when calculating entity correlation, while SRSCL fails to incorporate the holistic representation of entities within the entire HIN. These shortcomings hinder the accurate measurement of entity correlation, ultimately constraining the precision of entity linking.

In fact, entities in HINs are interconnected through complex network structures, forming a rich semantic relationship network. Through in-depth analysis and summarization, entities in HINs exhibit two distinct characteristics: local features and global features. Local features are primarily reflected in the short-path information between entities. For example, entities connected via 1-hop or 2-hop paths often exhibit stronger correlations, as such path information effectively captures the direct contextual relationships surrounding entities. Global features, on the other hand, are manifested in the positioning or role of entities within the entire HIN, i.e., the potential semantic information between entities connected through deep network structures. This information reflects the global influence and semantic distribution of entities across the network. Therefore, in scenarios with limited information, accurate entity linking requires a comprehensive consideration of both local and global features of entities. By thoroughly computing the correlation between entities, precise entity matching and linking can be achieved. Such multi-level feature fusion not only enhances the accuracy of entity linking but also improves the model’s adaptability to complex network structures, providing more reliable support for tasks such as knowledge retrieval, reasoning, and recommendation.

Preliminaries and notation

This section primarily introduces the fundamental concepts employed in this article, as well as the definition of the collective entity linking.

Definition of heterogeneous information network

A HIN is an information network that comprises various types of relations and entities.

Definition 1 (heterogeneous information network): A heterogeneous information network is defined as a graph , where denotes entities contained in the set of entities , and represents relations contained in the set of relations . is a set of triples composed of entities and relations, i.e., . The elements in can be represented in the form of triplets. For example, is an element in . Another notable characteristic of HIN is that each entity belongs to a specific entity type, and each relation belongs to a specific relation type. Furthermore, the number of entity types and the number of relation types are both greater than 1, reflecting the diversity and richness of HIN.

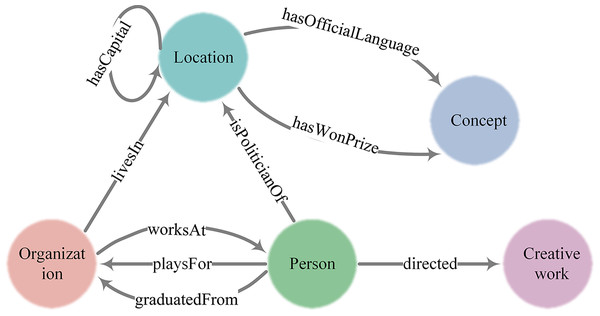

YAGO encompasses a variety of entity types and relation types, with these diverse entities interconnected through an array of relations, together forming a vast HIN. Figure 3 vividly illustrates five categories of entities, nine categories of relations, and their complex interconnections. Within YAGO, different kinds of entities may be connected through multiple relations or just a single one; likewise, entities of the same category might also be associated through certain specific relation. For instance, ‘Organization’ and ‘Person’ can be linked through various relations such as ‘worksAt’, ‘playsFor’, and ‘graduatedFrom’, and different relations point in different directions, whereas ‘Person’ and ‘Creative work’ might be connected via the ‘directed’ relation. Additionally, ‘Location’ could be related to another ‘Location’ through relations like ‘hasCapital’. These intricate connections not only demonstrate the heterogeneity of YAGO but also highlight its powerful capability for information representation.

Figure 3: An example of entity mention linking to YAGO.

Some entity classes and their relations in YAGO.Collective entity linking for heterogeneous information network

Definition 2 (entity mention group, candidate entity group (Zu et al., 2024b)). Given an entity mention set , and a set of candidate entities for entity mention , where denotes the th candidate entity for and denotes the number of candidate entities for . In the entity linking process, a tuple of all the entity mentions in is referred to as an entity mention group, and a tuple composed of one candidate entity for each entity mention as a candidate entity group, i.e., is an candidate entity group of the entity mention group .

Definition 3 (collective entity linking for HIN). Given the entity mentions extracted from a given text, a HIN , and a set of candidate entities for each entity mention , collective entity linking treats the extracted entity mentions as a whole (i.e., the entity mention group ) and aims to find a candidate entity group in the HIN that corresponds to the same referent as the group of entity mentions.

By comprehensively considering the associations and contextual information among entity mentions, collective entity linking can more accurately identify the corresponding entities in the information network for the entity mentions, thereby improving the accuracy and reliability of entity linking. Therefore, collective entity linking should not only consider the similarity between candidate entities and entity mentions but also pay close attention to the correlation among the candidate entities.

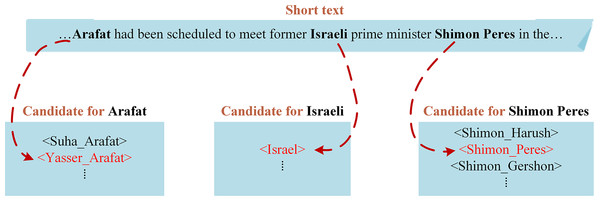

Here is a real-world case of collective entity linking. “Arafat”, “Israeli” and “Shimon Peres” are entity mentions of the sentence “…Arafat had been scheduled to meet former Israeli prime minister Shimon Peres in the…”, as shown in Fig. 4. Judging from the surface form, the entity most likely to be linked with “Arafat” is <Suha_Arafat > rather than <Yasser_Arafat>. However, the entity mention group Arafat, Israeli, Shimon Peres) actually refers to the corresponding candidate entity group (<Yasser_Arafat>, <Israel>, <Shimon_Peres>) in YAGO. Intriguingly, compared to other candidate entity groups, the connections between the entity group (<Yasser_Arafat>, <Israel>, <Shimon_Peres >) are closer. Therefore, in the process of collective entity linking, these entities are more likely to be identified as a whole, accurately reflecting their actual referents in the given text.

Figure 4: An example of collective entity linking demonstrates.

Example of linking all the three entities in a text to YAGO simultaneously.Local-Global Correlation Fusion for Probabilistic Collective Entity Linking method

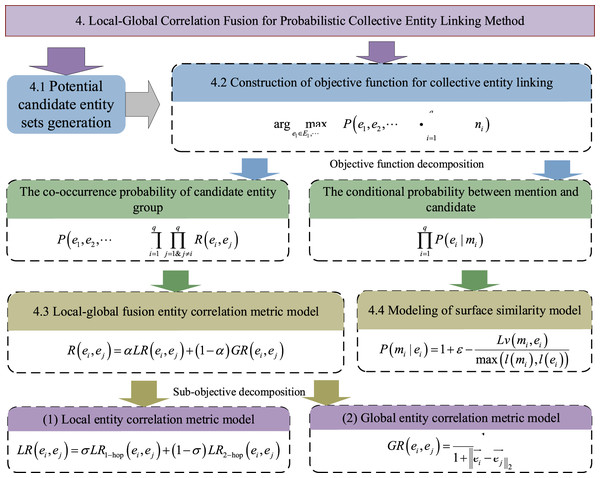

In this section, we propose a Local-Global Correlation Fusion for Probabilistic Collective Entity Linking (LGCFPEL) method. LGCFPEL accomplishes collective linking through three crucial steps. Firstly, potential candidate entity sets are generated for each entity mention, providing alternative options for subsequent linking processes. Secondly, a probabilistic linking model is constructed to quantify the linking possibilities between entity mentions and candidate entities, which helps us better understand their relations. Finally, a local-global fusion entity correlation metric model and a surface similarity model are proposed to optimize the objective function and find the optimal entity linking solution. The technology roadmap of LGCFPEL is shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: The technology roadmap of LGCFPEL.

The overall calculation process of LGCFPEL, including candidate entity generation and candidate entity ranking, is introduced in ‘Potential Candidate Entity sets Generation’ and ‘Construction of Objective Function for Collective Entity Linking’–‘Modeling of Surface Similarity Model’, respectively.Potential candidate entity sets generation

The generation of candidate entities is a crucial step in the entity linking, and its accuracy directly impacts the precision of the final entity linking. If the candidate set for an entity mention omits its corresponding real entity, the entity linking process will inevitably fail. Therefore, it is essential to ensure that all possible entities are included in the candidate set during the generation of candidate entities.

In practical applications, users often possess prior knowledge related to the retrieval target when conducting knowledge retrieval in a specific domain. The prior knowledge is reflected in the user’s input, making the entity mentions entered by users often contain parts related to or similar in appearance to the actual retrieval target. For example, if the retrieval target is “aircraft engine,” users may input keywords such as “aircraft”, “engine”, or “engines in the aircraft field”.

Based on the above analysis, this article adopts the following strategy to generate a candidate entity set for each entity mention. By adopting this method, we can ensure that the generated candidate entity set is both comprehensive and accurate, providing a solid foundation for the subsequent entity linking process.

Firstly, an entity is considered a candidate if its keywords and key phrases align with those extracted from the entity mention.

Secondly, after removing unimportant words such as “of” and “I,” the entities in HIN share common words with the entity mention.

Finally, an entity may be an abbreviated form of an entity mention, or an entity mention may be a shortened representation of an entity.

Collective entity linking typically involves complex computations and matching processes, resulting in high computational costs. Therefore, it is crucial to manage computational resources effectively at each stage of entity linking to optimize performance. When the number of candidate entities generated for certain entity mention is excessively large, this not only consumes a significant amount of computational resources but also substantially increases the algorithmic complexity of entity linking. To reduce computational costs, it is necessary to effectively decrease the size of the candidate entity set without missing out on genuine candidates. Through data observation and literature research, we can easily acquire category information for candidate entities through mature named entity recognition methods (Keraghel, Morbieu & Nadif, 2024; Goyal & Singh, 2025). Additionally, by integrating language and classification models, the category information of entity mention can be observed. Based on this analysis, two pruning steps on the candidate entity set are implemented to obtain a refined collection of candidates.

Firstly, we eliminate those entities from the candidate set that do not match the type of the corresponding entity mention, ensuring the correlation of the remaining candidates.

Secondly, if the size of the candidate set still exceeds a predefined threshold k after the initial step, abbreviations are prioritized for retention due to their high information density and strong semantic consistency. On this basis, we further filter and select the top-k most similar candidates to the entity mention, ensuring the quality and representativeness of the candidates.

Through the two pruning steps, the computational complexity of entity linking can be effectively reduced without compromising the integrity of the true candidate entities, thus enhancing efficiency and accuracy.

Construction of objective function for collective entity linking

Given an entity mention group within a sliding window, the goal of collective entity linking is to identify a set of candidate entities in the HIN that collectively refer to the same real-world with . Therefore, the objective function of collective entity linking can be described as finding such a set of candidate entities that highly semantically match the group of entity mentions within the sliding window and jointly refer to the same real-world entity, which is illustrated in Eq. (1)

(1) where is a candidate entity set generated by the candidate entity generation method for a specific entity mention .

Assuming that the linking probabilities for each entity mention are computed independently, the objective function of collective entity linking can be expressed as Eq. (2)

(2)

Objective truths reveal the ubiquitous interconnectedness among various entities, particularly evident in linguistic texts. When strong correlation exist among multiple entities, their joint appearance probability increases significantly when mentioned again within the text. Simultaneously, the occurrence of entity mentions always exhibits a certain degree of correlation, which closely relies on the strong interconnections inherent in linguistic logic. Specifically, the stronger the correlation between entities, the higher the probability of their concurrent appearance within the same text.

Therefore, during the entity linking process for a given text, the selection of candidate entities linked to each entity mention is not an independent process but rather an interactive validation seeking the globally optimal solution. Based on the aforementioned analysis, the adjustment factor is introduced into the Eq. (2) to more accurately describe the interdependencies in entity linking. As shown in Eq. (3), the revised formula better reflects the actual situation of entity linking, enhancing its accuracy and efficiency.

(3)

According to Eq. (3), the solution to the collective entity linking objective function can be decomposed into two main components:

(1) The co-occurrence probability of candidate entity group, which captures the likelihood of multiple candidate entities appearing simultaneously in a given text. The probability reflects the degree of association between entities within the text and is crucial for determining the correlation among entities.

(2) The conditional probability , which represents the likelihood of linking a specific entity mention to a particular candidate entity when the mention occurs. This probability reflects the degree of match between the entity mention and the candidate entity and serves as a key factor in determining the optimal entity linking.

Subsequently, a local-global fusion entity correlation metric model and a surface similarity model are proposed to calculate the co-occurrence probability and conditional probability, respectively, thereby completing the solution process for the collective entity linking objective function.

Local-global fusion entity correlation metric model

Generally, the probability of an event occurring is calculated based on its frequency. However, it is noteworthy that accurately computing the co-occurrence probability of entities (i.e., ) based solely on frequency can be challenging. Firstly, it is difficult to obtain all documents in a specific domain accurately. Secondly, information about entities is constantly changing. Fortunately, linguistic logic exhibits strong associations, and the co-occurrence probability of entities is directly proportional to their correlation. Entities with stronger correlation are more likely to appear simultaneously in a given text. Therefore, the correlation of entities can be leveraged to estimate their co-occurrence probability, as demonstrated in Eq. (4).

(4) where is a correlation metric model designed to measure the correlation between two entities.

HIN is a complex network constructed through natural language texts, where entities are interconnected via diversified relations. Generally, the stronger the correlation between entities is, the shorter their paths is in the network. Therefore, path information between entities can serve as an effective means to measure their correlation. CFEL suggests that 2-hop paths between entities can effectively reveal their associational information, indicating that path information can represent the primary feature information of entities. However, it is noteworthy that CFEL primarily focuses on directed paths between entity pairs when calculating correlation, overlooking the potential impact of various 2-hop paths on measuring entity correlation. Moreover, relying solely on local information surrounding the entities often fails to comprehensively capture their semantic meaning within the entire HIN, which could lead to the loss of potential semantic features of entities. Consequently, the accuracy of correlation measurement is affected.

Efficiently mining the potential semantic information of entities is a challenging issue. At the same time, relying solely on the potential semantic information might neglect the contribution of surrounding information to entity correlation. Therefore, to accurately measure the correlation between entities, it is necessary to consider two sets of characteristics: one is the local features of the entities, mainly determined by the surrounding information; the other is the global features of the entities, namely their potential semantic representations within the entire HIN. Based on these considerations, a local-global fusion entity correlation metric model (LGFEC) is proposed to achieve more accurately measuring entity correlation. The LGFEC integrates both local and global entity features, allowing for a more holistic representation of their positioning within the HIN. The specific LGFEC is shown in Eq. (5).

(5) where is the local entity correlation metric model based on local information, while is the global entity correlation metric model that leverages global information. is a hyperparameter that measures the importance of local information and global information, with its value typically ranging from 0 to 1.

(1) Local entity correlation metric model

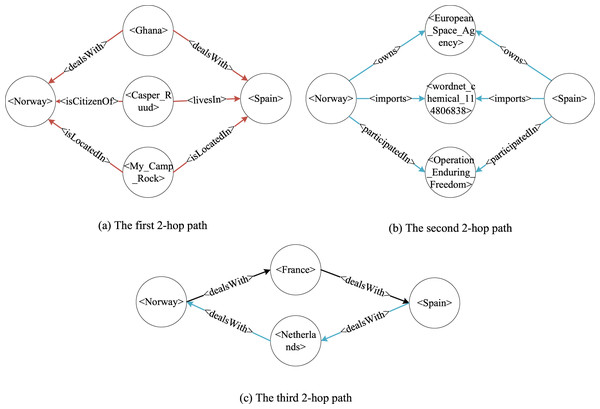

Previous studies have demonstrated that the 1-hop and 2-hop paths of entities are effective in capturing the correlation information between entities (Li et al., 2021). Therefore, in the constructed local correlation metric model, only the 1-hop and 2-hop paths of entities are used to measure the local correlation between entities. Notably, unlike previous studies, our analysis reveals that there are three types of 2-hop paths between two entities: (1) paths formed by a common entity that points to both entities, (2) paths formed by two entities that point to a common entity, and (3) a direct 2-hop directed path between the two entities. As shown in Fig. 6, there exist multiple such 2-hop paths between the entities <Norway> and <Spain>. Among them, <Norway>→<Ghana>←<Spain> belongs to the first type, <Norway>←<European_Space_Agency>→<Spain> belongs to the second type, and <Norway>→<France>→<Spain> and <Norway>←<Netherlands>←<Spain> belong to the third type. Relying solely on one type of 2-hop paths of entities cannot fully reflect the surrounding information of entities, leading to inaccurate measurements of entity correlation. To fully utilize the information surrounding entities and accurately measure their relevance, this article develops a local correlation metric model based on three types of 2-hop paths and their respective contribution weights to relevance.

Figure 6: Three types of 2-hop paths between entities.

Three types of 2-hop paths between two entities exists in YAGO: (1) paths formed by a common entity that points to both entities, (2) paths formed by two entities that point to a common entity, and (3) a direct 2-hop directed path between the two entities.The shorter the path between entities is, the greater the direct correlation between them is, typically. However, the relationship between path length and correlation is not absolute and may be influenced by other factors. Furthermore, the existence of multiple high-quality paths between two entities may enhance their correlation. Taking these considerations into account, the local entity correlation metric model can be modeled as Eq. (6).

(6) where is a correlation metric function based on the 1-hop paths of entities. When there exists a direct 1-hop path between two entities, the value of is 1, indicating a direct correlation; otherwise, is 0, indicating the absence of direct correlation. , on the other hand, is a correlation metric function based on the 2-hop paths of entities, as defined by Eq. (7). Additionally, serves as a weight hyperparameter that adjusts the relative importance of 1-hop and 2-hop paths in the overall correlation metric.

(7) where, represents the path length from to , specifically with a value of . denotes the number of entities pointed to by , while indicates the number of entities pointed to by . Furthermore, and represent the counts of two distinct types of 2-hop paths, with corresponding to the count of the first type of 2-hop paths and , and corresponding to the count of the second type of 2-hop paths and . is the count of the third type of 2-hop paths from to ; whereas represents the count of the third type of 2-hop paths from to . Finally, is a hyperparameter that measures the relative importance of directed 2-hop paths compared to other types of 2-hop paths.

(2) Global entity correlation metric model

In HINs, the 1-hop and 2-hop path information of entities often fails to directly reveal their global features. To improve the accuracy of entity correlation metrics, it is essential to delve deeper into the underlying network structures of entities, effectively capturing their potential semantic information within the HIN. However, directly extracting such potential semantic information from deep network structures is not a straightforward task. This challenge primarily arises from two major issues: first, the vast scale of HINs makes it difficult to estimate the computational resources required to obtain deep network structures of entities; second, accurately quantifying the potential semantic information embedded in these deep network structures remains a critical.

Currently, knowledge representation learning models have demonstrated significant advantages in converting textual information from heterogeneous information networks into low-dimensional dense semantic vectors. By learning the semantic associations of triplets, the models can deeply explore the characteristics of entities’ deep network structures, thereby accurately capturing their potential semantic features throughout the HIN. Additionally, through vector representations, the potential semantic correlation between entities can be effectively quantified.

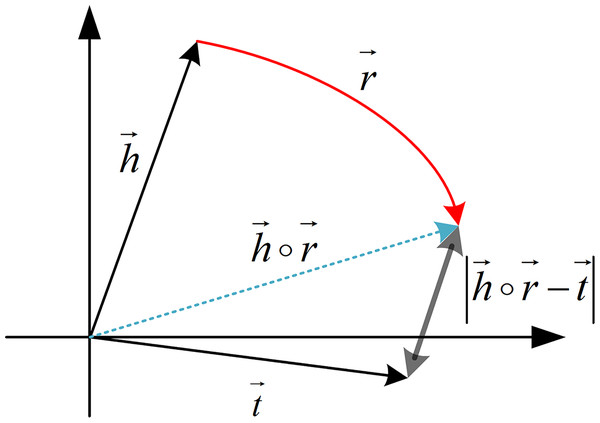

Therefore, to effectively calculate the potential semantic correlation between entities, this article adopts the advanced RotatE model to learn the semantic representations of entities (Sun et al., 1902). Regarding the selection of the RotatE model, the decision is primarily based on its four core advantages: (1) Complex relationship modeling capability: Through complex space rotation operations, it can simultaneously handle symmetric/asymmetric/inverse relationships; (2) semantic representation superiority: Maintains high discriminability in low-dimensional spaces while accurately characterizing analogical relationships; (3) noise robustness: The phase difference mechanism demonstrates higher tolerance to knowledge base incompleteness; (4) computational efficiency: Reduces complexity while maintaining performance. Thus the RotatE model can more accurately capture the semantic information between entities and relations, exhibiting excellent performance in HIN analysis. As shown in Fig. 7, RotatE can obtain low-dimensional semantic vector representations of entities, further enabling precise metric of their potential semantic correlation.

Figure 7: Schematic diagram of RotatE model.

In a triple, h, r, and t are the complex vector representations of the head entity, relation, and tail entity, respectively. The relation is regarded as a rotation vector from the head entity to the tail entity, meaning that for a correct triplet, the tail entity vector should be equal to the head entity vector rotated by the relation vector.Utilizing the semantic vector representations of entities, we are able to accurately quantify the potential semantic correlation between any two entities using Euclidean distance. Based on this, a global entity correlation metric model is modeled as Eq. (8).

(8) where and represent the semantic vector representations of entities and , respectively. Meanwhile, denotes the 2-norm of vector c, which quantifies the Euclidean distance between entities and in the semantic vector space.

Modeling of surface similarity model

Similarly, word frequency-based methods cannot be directly employed to calculate the similarity between entity mentions and candidate entities. During knowledge retrieval, due to the existence of prior knowledge in the brain, the input entity mentions often possess a certain degree of surface similarity with the actual retrieval targets. Therefore, the conditional probability between entity mention and candidate entity is estimated by calculating their surface similarity. Specifically, the Levenshtein distance is adopted to measure the similarity between entity mentions and candidate entities, as shown in Eq. (9).

(9) where is the Levenshtein distance between the entity mention and the candidate entity . represents the string length of the entity .

Assuming that , and in the case where two candidate entity groups both contain the candidate entity , according to Eq. (3), the probabilities of linking the two candidate entity groups are both equal to 0. This outcome demonstrates that , the linking possibilities of multiple candidate entity groups might become ambiguous. To prevent such a scenario, a hyperparameter greater than 0 is introduced in Eq. (9), resulting in the improvement of Eqs. (9) to (10).

(10)

Hence, the objective function for collective entity linking can be solved through Eq. (11).

(11)

Collective entity linking experiment

Experimental data

(1) Heterogeneous Information Network for Entity Linking

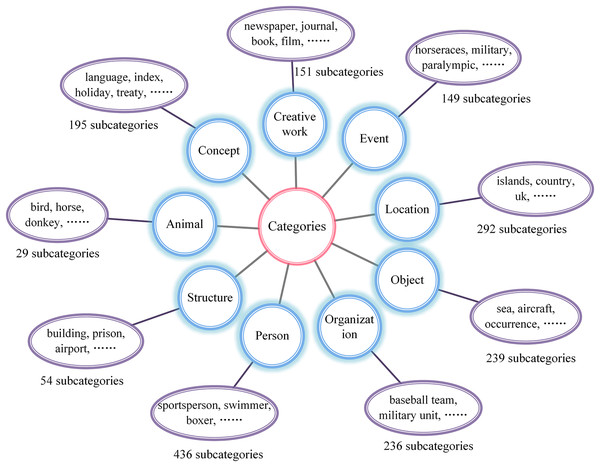

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed LGCFPEL model, a subset of YAGO is utilized as the knowledge base for entity linking. The knowledge base comprises a total of 10 K entities and 770 K triplets. Additionally, when generating candidate entities using our proposed approach, it is necessary to prune the candidate entity set based on entity category information. Consequently, categorical annotations are assigned to the entities in the YAGO dataset. Drawing upon prior research and leveraging the entity classification scheme (Kalender & Korkmaz, 2017), entities are categorized into nine broad classes, encompassing persons, concepts, creative works, events, locations, objects, organizations, people, and structures. Through meticulous examination of the data, it was discovered that YAGO contains 1798 distinct entity category labels, examples include “officeholder,” “ethnic group,” “person,” and “mountain.” Furthermore, these fine-grained categories are mapped to their corresponding broader class labels. For instance, entities classified as “officeholder” are assigned to the broader category of “persons,” while entities labeled as “ethnic group” are grouped under the category of “organizations.” Finally, the detailed mapping of fine-grained labels to their respective broader categories is illustrated in Fig. 8.

Figure 8: Categorical annotations for YAGO entities.

All entities in YAGO are annotated with fine-grained labels and categorized into nine major classes, including persons, concepts, creative works, events, locations, objects, organizations, animals, and structures.(2) Text datasets for entity linking

To validate the efficacy of the proposed model, we conducted entity linking experiments on YAGO utilizing three public datasets (AIDA CoNLL-YAGO, AQUAINT, and ACE 2004). Table 1 provides detailed information regarding the number of entity mentions in each dataset, the count of entity mentions linked to entities within the HIN, and the number of entity mentions with candidate entities. To ensure the representativeness of the experimental results, the experiments are focused on the entity mentions of linked entities present in the knowledge base. This decision is made as the HIN employed in the experiments is derived from a subset of YAGO. Notably, some entity mentions may be linked to entities that do not exist within the HIN used. Such occurrences would render the experimental results uninformative and lacking in interpretability.

| Dataset | The number of entity mentions | The count of entity mentions linked to entities within the HIN | The number of entity mentions with candidate entities |

|---|---|---|---|

| AIDA CoNLL-YAGO | 34,929 | 20,228 | 19,716 |

| AQUAINT | 727 | 186 | 180 |

| ACE 2004 | 257 | 125 | 124 |

(3) Sample generation

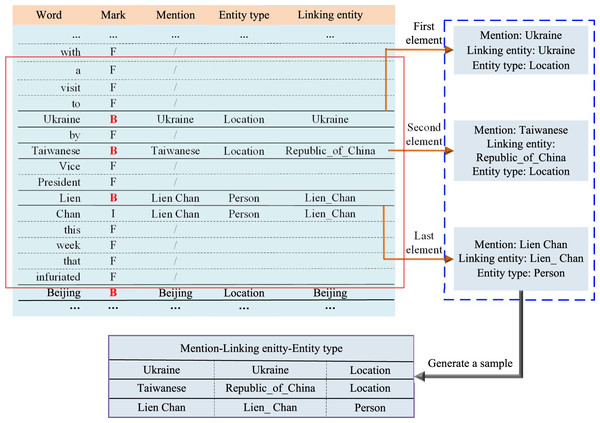

Typically, collective entity linking requires the specification of a sliding window length, within which all entity mentions are treated as a unit or a sample for linking experiments. Subsequently, the overall correlation of the candidate entity group corresponding to the entity mention group is calculated to achieve collective entity linking. Figure 9 illustrates an example of an entity mention group extracted from the AIDA CoNLL-YAGO with a sliding window size of 14. In Fig. 9, “F” represents meaningless tokens, “B” denotes the first word of an entity mention, and “I” represents the remaining words of the entity mention. As shown in Fig. 9, the first sliding window encompasses three entity mentions: “Ukraine,” “Taiwanese,” and “Lien Chan,” which together form an entity mention group/sample.

Figure 9: Entity mention group extraction process.

Step 1: Determine the sliding window length. Step 2: Select entity mentions based on the ‘Mark’. Step 3: Extract the “entity mention-linking entity-entity type”. Step 4: Combine all mentions within a window into an entity mention group.Model evaluation

In the experiment, precision, recall, and F-score are employed to evaluate the effectiveness of entity linking, as indicated in Eqs. (12)–(14).

(12)

(13)

(14) where represents the number of correctly linked entities, denotes the number of entity mentions that have candidate entities, and signifies the total number of candidate entity mentions participating in the experiment.

Simultaneously, to evaluate the “collective” linking performance of the entity linking model, specifically its ability to mine associative information, the evaluation method from SRSCL is introduced in the experiment.

Experiments

The experiment can be divided into two parts. The first part is a comparison experiment, and the second part is the LGCFPEL parameter optimization experiment.

Comparison experiments

To validate the efficacy of the proposed LGCFPEL, a comparison analysis is conducted in this section by selecting seven domains’ entity linking models. The comparison models include the traditional entity popularity model (POP) (Shen, Han & Wang, 2014), the classic CFEL model (Li et al., 2021), as well as embeddings (EMDD) and three types of 2-hop path (TTHP) models (Zu et al., 2024b), M-TTHP, and the novel SRSCL model (Zu et al., 2024b). It should be noted that this study does not include comparisons with large-scale neural retrieval models like GENRE. The reason is that their designs rely on the availability and computational resources for dense indexing of the entire knowledge base-a premise incompatible with the resource-constrained setting central to this work. Moreover, for the comparative experiments, the YAGO is utilized for entity linking. The initial 1,000 entity mention groups from the AIDA CoNLL-YAGO, employing a sliding window of size 10, serve as the training data for optimizing the hyperparameters of the LGCFPEL. The subset used for hyperparameters analysis is strictly isolated from the final test set, with no overlap between the two. Subsequently, the entity linking models are applied to three public datasets: AIDA CoNLL-YAGO, AQUAINT, and ACE2004, to evaluate and compare the performance of each model’s entity linking capabilities.

The six comparison models employed each possess their unique characteristics. Specifically, the POP aggregates information surrounding entities through an adjacency matrix, assigning a popularity score to each entity and performing entity linking based on the scores. The CFEL method introduces a human brain priority cognitive mechanism for the first time, establishing and solving a collective entity linking objective function based on the correlation of entities. TTHP and EMDD represent two different extensions of the CFEL framework, where TTHP measures entity correlation using three types of 2-hop paths, while EMDD utilizes semantic vectors to quantify the correlation between entity pairs. M-TTHP, within the framework of this article, employs the locally entity correlation metric model to assess entity correlation. SRSCL is a novel entity linking method that captures the correlation of candidate entities using relatedness sequences.

To comprehensively evaluate the entity linking performance of each model across three datasets, precision, recall, and F-score are employed as metrics. Table 2 presents the detailed performance of each model on different datasets, with the optimal results highlighted in bold for easy comparison.

| Dataset | AIDA CoNLL-YAGO | ACE2004 | AQUAINT | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metric | P (%) | R (%) | F (%) | P (%) | R (%) | F (%) | P (%) | R (%) | F (%) |

| POP | 74.93 | 71.34 | 73.09 | 82.26 | 82.26 | 82.26 | 75.71 | 74.44 | 75.7 |

| CFEL | 80.37 | 76.51 | 78.39 | 89.52 | 89.52 | 89.52 | 86.44 | 85.00 | 85.71 |

| EMDD | 79.97 | 76.14 | 78.01 | 89.52 | 89.52 | 89.52 | 88.70 | 87.22 | 87.96 |

| TTHP | 81.71 | 77.79 | 79.7 | 88.71 | 88.71 | 88.71 | 84.18 | 82.78 | 84.37 |

| M-TTHP | 82.22 | 78.27 | 80.20 | 89.52 | 89.52 | 89.52 | 88.70 | 87.22 | 87.96 |

| SRSCL | 82.55 | 78.59 | 80.52 | 91.13 | 91.13 | 91.13 | 89.27 | 87.78 | 88.52 |

| LGCFPEL | 83.35 | 79.35 | 81.30 | 91.13 | 91.13 | 91.13 | 89.27 | 87.78 | 88.52 |

Note:

The best result has been highlighted in bold.

As shown in Table 2, LGCFPEL achieves either the best or equally best performance (in terms of precision, recall and F1-score) across all three mainstream entity linking datasets: AIDA CoNLL-YAGO, ACE2004 and AQUAINT. The results fully validate that the proposed LGCFPEL significantly improves disambiguation capability through collaborative modeling of knowledge representation (global features) and multi-path (local features). It should be noted that AIDA CoNLL-YAGO is a carefully curated news corpus with minimal noise, ACE2004 covers multiple domains and AQUAINT is primarily news-based but contains more noise.

Table 2 demonstrates that compared with the state-of-the-art SRSCL, LGCFPEL shows significant improvement on AIDA CoNLL-YAGO while achieving comparable performance on ACE2004 and AQUAINT. Two key findings can be revealed: (1) LGCFPEL effectively handles entity linking tasks across diverse domains and varying noise levels, while SRSCL struggles with low-noise data. (2) Entity linking prioritizes local features in low-noise scenarios but requires more global features in noisy environments.

The results confirm LGCFPEL’s capability to effectively extract both global and local features, leading to optimal performance and superior generalization. Notably, LGCFPEL achieves this without computing candidate entity correlation sequences, resulting in significantly lower computational complexity than SRSCL. Moreover, against M-TTHP: LGCFPEL achieves substantial improvements across all three datasets (precision, recall and F-score), validating the effectiveness of its global semantic feature capture. Against TTHP, M-TTHP shows significant gains (nearly 4% on AQUAINT), demonstrating our local model’s effectiveness in noisy conditions. Against EMDD, CFEL performs better on noisy AIDA CoNLL-YAGO but worse on ACE2004 and AQUAINT. Thus, a fundamental observation can be obtained: In high-quality linking data, entity linking primarily focuses on local information, while in noisy data, accurately capturing global entity information becomes crucial. The aforementioned analysis demonstrates that LGCFPEL’s integration of both local and global features enables comprehensive entity feature extraction, significantly enhancing the model’s adaptability across multimodal data. The results further validate LGCFPEL’s superior generalization capability and overall effectiveness.

Specifically, Table 2 demonstrates that the proposed LGCFPEL achieves the most optimal linking results across all datasets and evaluation metrics. Compared to the POP, the probability-based entity linking methods have significantly improved. For instance, on the large-scale dataset, AIDA CoNLL-YAGO, the probability-based methods achieved at least a 5% increase in precision, recall, and F-score. On the sparser AQUAINT dataset, the improvements are nearly 9%. The experimental results clearly demonstrate the substantial advantages of probability-based entity linking models. Surprisingly, the method proposed in this article significantly outperforms CFEL. The comparative analysis verifies the better generalization ability of the proposed LGCFPEL.

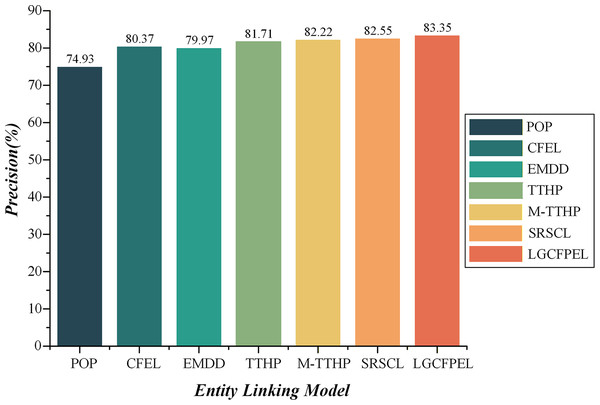

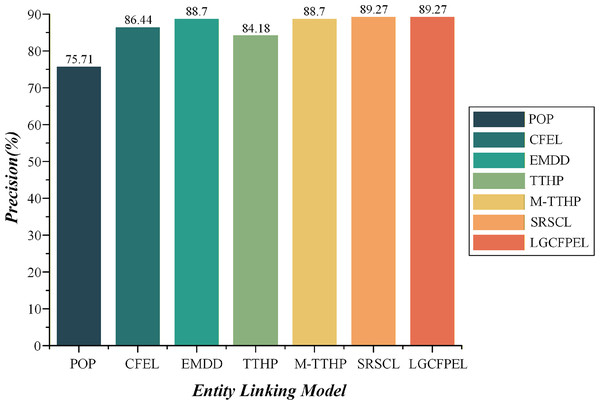

Table 2 reveals that both the recall and F-score are linearly correlated with precision. In other words, higher precision corresponds to higher recall and F-score. Surprisingly, the models exhibit a similar trend in the results on ACE2004 and AQUAINT. For example, CFEL’s performance is consistently lower than EMDD across both datasets, yet it consistently outperforms TTHP. In light of this, we further analyze the entity linking outcomes of each model using AIDA and AQUAINT precision as examples, as illustrated in Figs. 10 and 11.

Figure 10: The entity linking precision on A IDA CoNLL-YAGO.

LGCFPEL achieves the highest value (83.35%).Figure 11: The entity linking precision on AQUAINT.

LGCFPEL and SRSCL achieve the highest value (89.27%).Overall, the LGCFPEL achieves the most superior entity linking results, follows by SRSCL and M-TTHP, which respectively secure the second and third best performances. On the dense AIDA CoNLL-YAGO, the CFEL and TTHP significantly outperform EMDD. Conversely, on the sparse AQUAINT, the performance outcomes are reversed. Upon comparing M-TTHP with CFEL and TTHP, it becomes evident that the integration of 1-hop and 2-hop path-based entity correlation metric substantially enhances entity linking efficacy. Moreover, M-TTHP demonstrates significantly better precision than EMDD, corroborating our hypothesis that path information surrounding entities is a critical feature for entity linking. Notably, while the precision of M-TTHP and EMDD trail behind SRSCL, the fusion of M-TTHP and EMDD (i.e., LGCFPEL) demonstrates consistent and competitive performance with SRSCL across multiple datasets, with superior results on AIDA CoNLL-YAGO. The findings underscore the effectiveness of the proposed local-global fusion correlation metric model.

To further investigate the performance of LGCFPEL in collective linking, is employed to evaluate the results of various models across three public datasets. Given the positive correlation between recall, F-score, and precision, precision is chosen as the representative metric for assessing entity linking effectiveness. The precisions of seven entity linking models on are presented in Table 3. Furthermore, the optimal results are highlighted in bold and the second best results are highlighted in red for easy comparison.

| Dataset | AIDA CoNLL-YAGO | ACE2004 | AQUAINT | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metric | ||||||||||

| POP | 74.77 | 75.04 | 74.21 | 73.18 | 81.13 | 84.00 | 100.00 | 67.61 | 63.64 | 60.00 |

| CFEL | 81.19 | 81.58 | 81.33 | 80.22 | 90.57 | 88.00 | 100.00 | 78.87 | 81.82 | 80.00 |

| EMDD | 80.67 | 81.08 | 80.90 | 80.31 | 90.57 | 84.00 | 100.00 | 84.51 | 81.82 | 80.00 |

| TTHP | 82.93 | 85.15 | 85.85 | 87.35 | 88.68 | 88.00 | 100.00 | 73.24 | 81.82 | 80.00 |

| M-TTHP | 83.58 | 84.23 | 83.74 | 85.29 | 90.57 | 88.00 | 100.00 | 84.51 | 81.82 | 80.00 |

| SRSCL | 84.01 | 84.86 | 85.00 | 84.48 | 94.34 | 88.00 | 100.00 | 85.92 | 81.82 | 80.00 |

| LGCFPEL | 85.05 | 86.57 | 87.09 | 87.13 | 94.34 | 88.00 | 100.00 | 85.92 | 81.82 | 80.00 |

Note:

The best result has been highlighted in bold.

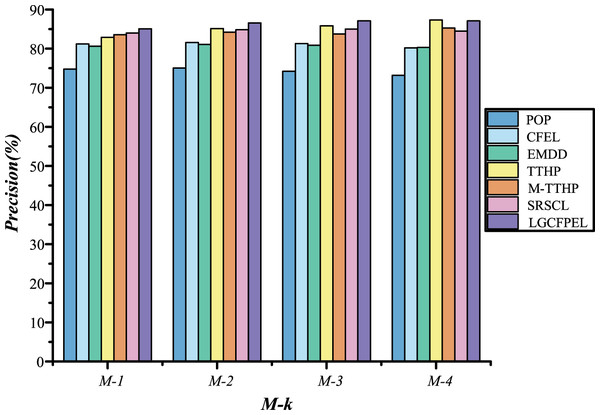

The results on AIDA CoNLL-YAGO reveals that in high-quality data environments, linking performance improves with increasing entity mentions for LGCFPEL, TTHP and M-TTHP, reaffirming the dominant role of local features in high-quality data linking scenarios. Notably, at M-4, TTHP outperforms LGCFPEL, which further validates that high-quality data linking prioritizes local feature information and excessive global information may weaken local feature representation. This result explains LGCFPEL’s relatively inferior performance at M-4.

Moreover, on the other two datasets, both LGCFPEL and SRSCL achieve optimal results, indicating their comparable capabilities in extracting dependency features across diverse domains and noisy data conditions. Collectively, LGCFPEL’s integration of global and local features significantly enhances the modeling of interdependencies among multiple candidate entities.

Specifically, Table 3 indicates that LGCFPEL achieves the best entity linking results in terms of – . However, on , TTHP achieves the highest precision, while LGCFPEL secured the second-best result. Notably, on – , LGCFPEL improves upon TTHP by 2.12%, 1.42%, and 1.24%, respectively. On , the precision of LGCFPEL is virtually identical to TTHP, with TTHP’s precision increasing by only 0.22%. On of ACE2004, LGCFPEL’s precision improves by 5.66%. On AQUAINT’s – , the precision of LGCFPEL is significantly higher than TTHP’s. Overall, LGCFPEL significantly enhances entity linking accuracy compared to baseline models.

Compared to the classic CFEL, LGCFPEL demonstrates significant precision improvements on AIDA’s , with a minimum increase of 3.86% and a maximum boost of 6.91%. Furthermore, as increases, the precision enhancement becomes more pronounced. On of ACE2004 and AQUAINT, LGCFPEL achieves precision improvements of 3.77% and 7.05%, respectively. However, on and , LGCFPEL’s precision remains on par with CFEL, likely due to the sparsity of the two datasets.

Simultaneously, a comparison between the proposed LGCFPEL and the latest SRSCL model is conducted. The results indicate that LGCFPEL achieves a significant improvement in entity linking precision. Specifically, on the of AIDA, the precision of LGCFPEL increased by a minimum of 1.01% and a maximum of 2.65%. However, on ACE2004 and AQUAINT, both models exhibited consistent precision, which is attributed to the sparsity of the datasets. Taking into account the linking results across all three datasets, the proposed LGCFPEL significantly LGCFPEL demonstrates consistent and competitive performance with SRSCL.

To further facilitate a more intuitive comparison of the linking results among various models, the results of seven models on the most representative AIDA dataset are presented in Fig. 12.

Figure 12: The M-k results of seven models on AIDA CoNLL-YAGO.

Overall, LGCFPE achieved the best results, TTHP achieved the second best results, and SRSCL achieved third best results.Figure 12 demonstrates that LGCFPEL significantly outperforms the comparison models in achieving the best collective linking results across all metrics, except for . On , TTHP attains the optimal result, with LGCFPEL achieving the second-best. Notably, the precision of TTHP and LGCFPEL on is approximately equivalent, whereas on to , the precision of LGCFPEL is significantly higher than that of TTHP. Surprisingly, both EMDD and M-TTHP exhibit lower precision than SRSCL. However, LGCFPEL, which combines the features of both, significantly surpasses SRSCL. The experimental results validate the effectiveness of the proposed local-global fusion entity correlation metric model.

To comprehensively analyze the advantages and disadvantages of the LGCFPEL, three of the most representative failure cases is selected, as shown in Table 4. Then a comprehensive qualitative error analysis of the predictions made by the LGCFPEL is conducted. The analysis is below.

| Sample | Mention | Truth entity | Candidate | Linking entity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | German | <Germany> | <Germany> | <Germany> |

| <Nazi_Germany> | ||||

| <West_Germany> | ||||

| <East_Germany> | ||||

| <German_Confederation> | ||||

| British | <United_Kingdom> | <Hanging_Lake_(Washington_-_British_Columbia)> | <British_Isles> | |

| <British_Indian_Ocean_Territory> | ||||

| <British_Columbia> | ||||

| <British_Isles> | ||||

| <Victoria,_British_Columbia> | ||||

| 28 | Ford | <Ford_Motor_Company> | <Watford_F.C.> | <John_Letford> |

| <John_Letford> | ||||

| <Brentford_F.C.> | ||||

| <Ford_Falcon_GT> | ||||

| <Bradford_Bulls> | ||||

| <Hartford_Whalers> | ||||

| <Oxford_United_F.C.> | ||||

| <Ford_Motor_Company> | ||||

| <Bradford_City_A.F.C.> | ||||

| <Hereford_United_F.C.> | ||||

| 55 | Netanyahu | <Benjamin_Netanyahu> | <Yonatan_Netanyahu> | <Sara_Netanyahu> |

| <Sara_Netanyahu> | ||||

| <Benzion_Netanyahu> | ||||

| <Benjamin_Netanyahu> | ||||

| Syria | <Syria> | <Syria> | <Syria> | |

| <Syrian_opposition> | ||||

| United States | <United_States> | <United_States> | <United_States> | |

| <United_Center> | ||||

| <Western_United_States> | ||||

| <Trucial_States> | ||||

| <United_Arab_Emirates> | ||||

| <United_Kingdom> | ||||

| <United_States_Virgin_Islands> | ||||

| <Mid-Atlantic_states> | ||||

| <West_North_Central_States> | ||||

| <East_North_Central_States> | ||||

| Moscow | <Russia> | <Moscow> | <Moscow> | |

| <Moscow_Kremlin> |

Case 1: Candidate entity generation failure

In Sample 1, the truth entity for the mention “British” is <United_Kingdom>, but the entity does not appear in the candidate set generated by the candidate entity generation method. Verification confirms that <United_Kingdom> exists in the linking knowledge base. The results indicate that improving the recall during the candidate entity generation stage is a key prerequisite for enhancing overall linking accuracy.

Case 2: Linking ambiguity in single entity mention

Sample 28 contains only a single entity mention. In the absence of contextual information provided by other mentions, the LGCFPEL has to rely excessively on the surface-level similarity between the mention and the entities, leading to linking failure. The results highlight the inherent challenge our model faces in handling single mention with sparse contextual information, and future work should focus on designing more robust disambiguation mechanisms specifically for such scenarios.

Case 3: Insufficient contextual semantics and knowledge associations

Sample 55 contains the mentions “Netanyahu” and “Moscow”. The linking results for this sample reveal two independent issues: (1) The failure to correctly link “Netanyahu” is likely due to the lack of strong associative paths between the entity of “Netanyahu” and other entities of co-occurring mentions, reflecting the impact of knowledge base completeness on model performance. (2) “Moscow” is incorrectly linked to <Moscow> or <Moscow_Kremlin>, while the truth entity is <Russia>. Note that <Moscow> is the capital of <Russia>. The results demonstrate the LGCFPEL’s remaining shortcomings in deep extraction of contextual semantics when understanding complex referential relationships (such as “capital representing the country”).

From the above analysis, the LGCFPEL proposed in this article significantly outperforms the other six entity linking models in terms of precision, recall, and F-score. The experimental results validate the effectiveness of the proposed local/global entity correlation metric model and local-global fusion entity correlation metric model. Furthermore, it verifies the effectiveness of LGCFPEL in domains’ entity linking without relying on external conditions. Finally, the LGCFPEL still needs improvement in candidate generation, sparse context processing, and complex semantic understanding.

Experiments on hyperparameter optimization of the proposed model

The embeddings of various entities in YAGO can be obtained from SRSCL (Zu et al., 2024b), therefore, this article does not retrain the embeddings of entities. To conduct the hyperparameter optimization experiments for LGCFPEL, this article adopts the hyperparameter settings listed in Table 5.

| Hyperparameter | The description of hyperparameter | Hyperparameter range |

|---|---|---|

| Measure the importance of local primary information and global secondary information | [0.1, 0.2, …, 0.9] | |

| Adjust the relative importance of 1-hop and 2-hop paths | [0.1, 0.2, …, 0.9] | |

| Measure the relative importance of directed 2-hop paths compared to other types of 2-hop paths | [0.1, 0.2, …, 0.9] | |

| Control the surface similarity between entity mention and candidate entity to be non-zero | [0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.01, 0.0001] | |

| Control the length pf the sliding window | [10, 15, 20, 25, 30] | |

| top-k | Control the size of candidate entity set | [5, 10, 15, 20] |

In the experiment, we employed the control variable method to optimize the various hyperparameters of the model. The core idea of this method is to fix the values of all other hyperparameters while adjusting the target hyperparameter and selecting the optimal hyperparameter combination by comparing the model performance under different hyperparameter settings. Through this approach, we can systematically evaluate the impact of each parameter on model performance, thereby finding the optimal parameter configuration.

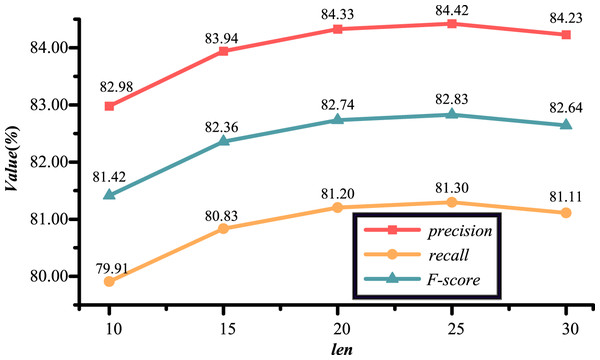

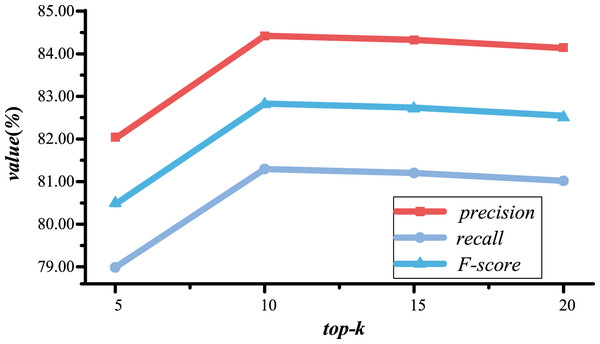

Taking the optimization of the sliding window length as an example, we kept all hyperparameters except the sliding window length unchanged and set the optimization range of the sliding window length as listed in Table 5. To illustrate more specifically, using a fixed parameter value of , , , as an example, the sliding window length and the number of candidate entity is optimized. Figure 13 demonstrates the entity linking results with different sliding window lengths when . Figure 13 illustrates that the entity linking performance of the model achieves the best state if the sliding window length is set to 25. Therefore, the optimal value of the sliding window length is determined to be 25. Subsequently, during the optimization of the number of candidate entity, the sliding window length is fixed at 25. Figure 14 illustrates the impact of different numbers of candidate entities on the entity linking results under the condition of . The experimental results indicate that when the number of candidate entity is set to 10, the entity linking performance of the LGCFPEL reaches an optimal level.

Figure 13: The entity linking results with different sliding window lengths when top-10.

The sliding window length increased from 10 to 25, and the accuracy, recall, and F-score of entity linking gradually improved. As the sliding window changes from 25 to 30, the accuracy, recall, and F-score of entity linking decrease. The results indicate that when the sliding window is set to 25, the entity linking effect is better.Figure 14: The entity linking results with different numbers of candidate entities.

Specifically, Fig. 13 shows that when the sliding window length increases from 10 to 25, the precision, recall, and F-score of entity linking gradually rise. The results strongly supports the effectiveness of the LGCFPEL in accurately computing the correlation information among candidate entities within a candidate entity group, effectively mining the connections between various entity mentions in a text segment, and further enhancing the performance of entity linking. However, when the sliding window length increases from 25 to 30, the precision, recall, and F-score of entity linking all decline. This phenomenon may be attributed to the characteristics of linguistic logic. Typically, when describing a certain object, keywords closer to it tend to have greater correlation, while those further away have less correlation. Therefore, as the number of entity mentions in the sliding window continues to increase, more irrelevant entity mentions are introduced, adding noise to the entity linking process and leading to a decrease in the effectiveness of entity linking. Based on the above analysis, the sliding window length is set to 25.

Figure 14 demonstrates that as the number of candidate entities increases from five to 10, the precision, recall, and F-score of entity linking using LGCFPEL all show an upward trend. The results suggest that when the number of candidate entities is 5, some of the true entities linked to entity mentions are not included in the candidate entity set, resulting in poor entity linking performance. However, when the number of candidate entities increases from 10 to 20, the precision, recall, and F-score of entity linking using LGCFPEL all decrease. The results lead to the following two conclusions: Firstly, when the number of candidate entities is 10, it is already possible to ensure that the true entities corresponding to entity mentions are included in the candidate entity set, validating the effectiveness of the candidate entity generation method established in this article, which demonstrates that a small number of candidate entities can achieve good entity linking results. Secondly, increasing the number of candidate entities may introduce more irrelevant candidate entities, adding more noise to the entity linking process. Therefore, as the number of candidate entities increases, the effectiveness of entity linking using LGCFPEL decreases. Additionally, it is worth noting that as the number of candidate entities increases, entity linking requires more computational resources and time. Taking all these factors into consideration, the number of candidate entities is set to 10.

Utilizing the control variable method, the conclusion have been arrived that the LGCFPEL achieves the best entity linking performance when the parameters are set to , , , , , and . Consequently, the set of hyperparameters has been established as the optimal choice for the LGCFPEL in the experiments. Notably, not only validates the rationality of leveraging local primary features and global secondary features of entities to solve the collective entity linking objective function, but also reveals that the local entity correlation model holds a slightly higher significance than the global entity correlation model in the LGCFPEL. The results further supports the validity of emphasizing local features as the primary and global features as the secondary. Furthermore, data demonstrates that in the local entity correlation metric, the importance of the 1-hop path is 0.2, verifying the rationality of considering both 1-hop and 2-hop paths. Additionally, the directed 2-hop path holds an importance of 0.7, while the other two 2-hop paths each have an importance of 0.3. The results further confirms the rationality of considering three distinct types of 2-hop paths. Collectively, the above results demonstrate the effectiveness and flexibility of the LGCFPEL in entity linking tasks.

Conclusions

Due to limitations such as reliance on third-party libraries, incomplete feature extraction, and poor interpretability, current collective entity linking methods for specific domains often exhibit limited accuracy, making it difficult to effectively support knowledge retrieval for some domains. To address these issues, this article proposes a Local-Global Correlation Fusion for Probabilistic Collective Entity Linking (LGCFPEL) method. LGCFPEL aligns more closely with human cognitive processes and constructs a probabilistic collective linking objective function based on this principle. By transforming the problem through probabilistic formulas, LGCFPEL skillfully avoids the direct computation of entity mention correlations and instead calculates correlations among their candidate entities. Furthermore, LGCFPEL establishes a local-global fusion entity correlation metric to extract both local and global features of entities within heterogeneous information networks. Finally, LGCFPEL is compared with state-of-the-art collective entity linking methods, such as CFEL and SRSCL, on three datasets. Experimental results demonstrate that LGCFPEL achieves superior collective entity linking performance, significantly outperforming CFEL and SRSCL in terms of linking accuracy.

While the LGCFPEL method demonstrates promising performance in our experiments, this study still has several noteworthy limitations that point to clear directions for future research. First, the final performance of the model is highly dependent on the quality of the upstream candidate entity generation stage. If the true target entity is not effectively retrieved during the initial candidate generation phase, subsequent disambiguation and linking steps cannot correct this fundamental error. Therefore, future work could focus on designing more robust candidate generation strategies with higher recall, or on constructing an end-to-end unified learning framework to jointly optimize candidate generation and entity disambiguation, enabling error correction across the entire pipeline. Second, the effectiveness of the current method is constrained by the structural completeness of the underlying HIN and the semantic modeling capacity of the employed knowledge representation learning model. Consequently, exploring how to integrate the deep contextual semantic understanding capabilities of pre-trained language models with existing knowledge representation learning approaches, in order to enhance the model’s ability to handle complex referential relationships and sparse-context scenarios, represents a highly promising research direction. Finally, there is an inherent trade-off between the model’s computational efficiency and interpretability. Future research could explore the development of more efficient approximate inference algorithms to improve the model’s scalability, and incorporate explainability techniques (such as attention visualization and decision path analysis) to reveal the key reasoning behind the model’s internal decisions. The model’s transparency and trustworthiness would be thereby enhanced, and the stringent requirements for explainable artificial intelligence (AI) in specific domains would be met.