Analyzing fish detection and classification in IoT-based aquatic ecosystems through deep learning

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Siddhartha Bhattacharyya

- Subject Areas

- Artificial Intelligence, Computer Vision, Neural Networks, Internet of Things

- Keywords

- Fish detection, Classification, IoT, Aquaculture, Deep learning

- Copyright

- © 2026 Mohd Rahman et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits using, remixing, and building upon the work non-commercially, as long as it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2026. Analyzing fish detection and classification in IoT-based aquatic ecosystems through deep learning. PeerJ Computer Science 12:e3496 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3496

Abstract

Fish, a crucial source of protein, contribute approximately 17% of the global animal protein intake. In Malaysia, the fisheries sector serves as a significant economic driver, contributing around 11.22 billion Malaysian ringgit to the nation’s GDP in 2021. However, overfishing poses a substantial threat, leading to the depletion of marine life, disruption of ecosystems, potential food shortages, and unemployment. The advent of the Internet of Things (IoT) offers transformative potential for aquaculture, enhancing productivity, reducing waste, and promoting sustainability. This research underscores the viability of IoT-based smart aquaculture, focusing on different species and colours, such as red tilapia, black tilapia, and sailfin catfish. For monitoring aquaculture activities, the ESP32 Devkit is employed to collect data on temperature, dissolved oxygen, and pH levels, as well as to operate fish pellet feeders. Fish detection is facilitated using the NVIDIA Jetson Nano, an underwater camera, and various Darknet architectures within the You Only Look Once (YOLO) version, including YOLOv3, YOLOv3-Tiny, YOLOv4, and YOLOv4-Tiny. Future enhancements aim to monitor fish growth sizes, behaviour, and diseases, as well as identify waterborne pathogens, control pH, dissolved oxygen, and chlorine levels. The ongoing evolution of machine learning, deep learning, and transfer learning can facilitate the production of safe, high-quality, and abundant protein sources in well-regulated environments. This integration of technology into aquaculture signifies a promising step towards sustainable fisheries management, potentially mitigating the adverse effects of overfishing while ensuring the continued provision of essential protein sources. The study’s findings highlight the transformative potential of IoT and machine learning technologies in enhancing aquaculture productivity and sustainability. Among the tested models, YOLOv4-Tiny demonstrated the highest Average Precision (AP) and F1-score (approximately 1.00), making it the most suitable for real-time implementation due to its balance of accuracy and computational efficiency.

Introduction

Aquaculture has become one of the most critical pillars of global food production and nutrition security. According to the Food and Agriculture Organisation (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2022), aquaculture now supplies more than 50% of the world’s fish for human consumption, surpassing capture fisheries for the first time in history. This growth reflects the increasing demand for high-quality protein and essential micronutrients as the global population approaches 10 billion by 2050. Fish provide not only dietary protein but also key fatty acids such as omega-3, along with vitamins A, D, and B-complex, which are indispensable for human health (Bennett et al., 2021). Consequently, fisheries and aquaculture underpin the livelihoods of over 600 million people worldwide, including many in rural and coastal communities in Southeast Asia, where aquatic resources form the economic backbone (Pham et al., 2023; Teh & Pauly, 2018).

Despite these contributions, the sustainability of global fisheries faces significant threats. Overexploitation, habitat degradation, and the effects of climate change have led to stagnating or declining wild-capture yields since the mid-1990s (Pernet & Browman, 2021; Zeller et al., 2018). Destructive practices such as bottom trawling and unregulated discards continue to damage marine biodiversity, while limited governance and excessive subsidies exacerbate ecological pressure. The Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) recent State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024 report emphasises that many fish stocks remain below biologically sustainable levels, posing serious implications for both ecosystems and global food security (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2024). These challenges are particularly pronounced in tropical regions, where small-scale fishers depend heavily on rapidly depleting near-shore resources.

In response, aquaculture has expanded rapidly as an alternative and complementary source of aquatic food. Global aquaculture output grew by more than 60% between 2010 and 2022 and is projected to triple by 2050 to meet rising protein demand (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2022; Pernet & Browman, 2021). However, intensification brings new challenges, including disease outbreaks, feed supply constraints, waste accumulation, and environmental degradation of water bodies (Mandal & Ghosh, 2024). Therefore, achieving sustainability requires not only scaling production but also transforming management practices through innovation and data-driven decision-making. The FAO’s “Blue Transformation” framework highlights the need for digital and intelligent technologies to improve traceability, resource efficiency, and environmental stewardship within aquaculture systems (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2022).

For developing nations like Malaysia, aquaculture represents both an opportunity and a necessity. The country’s fisheries sector contributed approximately MYR 11 billion to the national Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2021, yet local operations still rely heavily on manual monitoring and labour-intensive practices. Integrating automation, artificial intelligence, and the Internet of Things (IoT) into aquaculture infrastructure has the potential to revolutionise production efficiency, ensure environmental sustainability, and support national food-security goals aligned with Malaysia’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (Rahman et al., 2023).

Despite the sector’s rapid growth, aquaculture continues to face numerous operational and environmental challenges that limit productivity and sustainability. Manual monitoring of fish behaviour, feeding activity, and water quality remains the dominant practice on many farms, yet it is time-consuming and prone to human error. In small- and medium-scale operations, farmers typically depend on visual inspection to estimate fish size or detect disease symptoms, which leads to inconsistent assessments and delayed intervention (Zhang et al., 2023). Moreover, irregular feeding schedules and poor control of dissolved oxygen or pH levels contribute to nutrient waste and fish mortality, ultimately reducing yield efficiency (Olanubi, Akano & Asaolu, 2024). These issues highlight the urgent need for intelligent monitoring tools that can automate data collection, interpretation, and decision-making.

Recent advances in the IoT have enabled continuous, sensor-driven observation of aquaculture environments. IoT-based systems equipped with temperature, pH, and dissolved-oxygen sensors can transmit real-time data through cloud platforms, allowing farmers to respond promptly to environmental fluctuations (Tsai et al., 2022). When integrated with automation modules such as feeders and aerators, these systems enable closed-loop control that reduces manual labour and improves water quality stability. However, while IoT devices can capture essential environmental data, they cannot directly assess biological parameters such as fish species, size, or health status. Consequently, the integration of computer vision and Artificial Intelligence (AI) has emerged as a complementary solution for comprehensive ecosystem management (Saleh, Sheaves & Rahimi Azghadi, 2022).

In recent years, deep learning, particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), has revolutionised image-based object detection and classification across various domains. Within aquaculture, these models have been applied to fish detection, counting, and behaviour recognition with remarkable accuracy (Yang et al., 2021). Among the most prominent frameworks, the “You Only Look Once” (YOLO) framework has shown exceptional performance in real-time object detection due to its single-stage inference and efficient architecture (Jalal et al., 2020; Mandal et al., 2023). Nevertheless, deploying such models in real-world aquaculture environments presents practical constraints. Many commercial fish farms operate on resource-limited hardware such as the NVIDIA Jetson Nano or Raspberry Pi, where computational and energy efficiency are critical concerns. High-capacity models, although accurate, often exhibit latency and overheating issues that hinder continuous field operation.

Addressing this trade-off between accuracy and computational efficiency has become a central research focus in smart aquaculture. Lightweight YOLO variants, such as YOLOv3-Tiny and YOLOv4-Tiny, offer reduced model complexity while maintaining competitive detection accuracy, making them ideal candidates for embedded implementation (Lopez-Marcano et al., 2021). Yet, few studies have systematically evaluated these models in conjunction with IoT-based monitoring for specific species under real aquaculture conditions. Furthermore, the integration of real-time sensing and visual analytics into a unified edge-computing platform remains underexplored, particularly in developing nations where affordable automation is essential for scaling aquaculture production.

This study aims to address these research gaps by developing a miniature IoT-based aquaculture ecosystem that combines water-quality monitoring and fish detection using optimised YOLO architectures. The proposed system employs sensors to record temperature, pH, and dissolved oxygen, while underwater cameras capture live video for real-time detection of red tilapia, black tilapia, and sailfin catfish. By deploying and comparing multiple YOLO models on the Jetson Nano, the study evaluates the trade-offs between detection accuracy, inference speed, and computational efficiency. The key contributions are summarised as follows:

-

1.

Development of a compact IoT-enabled aquaculture testbed that integrates sensor networks and automated feeding mechanisms for continuous environmental monitoring.

-

2.

Implementation and comparative evaluation of YOLO architectures (YOLOv3, YOLOv3-Tiny, YOLOv4, and YOLOv4-Tiny) for multi-species fish detection and classification in underwater imagery.

-

3.

Identification of the optimal lightweight model (YOLOv4-Tiny) for real-time deployment on low-power edge devices, balancing detection performance with resource usage.

-

4.

Demonstration of the potential of AI-driven IoT systems to advance sustainable aquaculture through proactive management, reduced waste, and enhanced productivity.

Through these contributions, the study reinforces the transformative potential of integrating IoT and deep learning technologies in aquaculture management. It aligns with global “Blue Transformation” goals by promoting sustainable, data-driven practices that can enhance resilience, efficiency, and food security across aquatic production systems.

Research background

Fish are a vital source of high-quality protein, micronutrients, and essential fatty acids, making them indispensable to global nutrition, public health, and food security (Bennett et al., 2021). Beyond their nutritional importance, fisheries and aquaculture sustain the livelihoods of millions of people and contribute directly to poverty reduction and rural development. However, the sustainability of marine resources is increasingly under threat. Global marine fisheries production, which peaked in the mid-1990s, has declined due to industrial overfishing, wasteful discarding practices, and climate-related stressors (Pernet & Browman, 2021; Zeller et al., 2018). Destructive fishing methods such as trawling and dredging further degrade ecosystems and reduce biodiversity, while weak policy enforcement and excessive subsidies undermine long-term sustainability.

These pressures are particularly pronounced in Southeast Asia, where small-scale fisheries play a central role in local food supply and employment. The region’s dependence on coastal fisheries has made it highly vulnerable to environmental degradation, overfishing, and market fluctuations (Pham et al., 2023; Teh & Pauly, 2018). Declining catch volumes not only threaten the livelihoods of fishing communities but also jeopardise regional food security and nutritional diversity. Consequently, sustainable aquaculture has emerged as a critical pathway to address both ecological and socio-economic challenges within the fisheries sector.

As global demand for aquatic food continues to rise, aquaculture has surpassed wild capture fisheries and is projected to triple by 2050 to meet growing protein needs (Pernet & Browman, 2021). This transformation is driven by population growth, rising incomes, and shifting dietary preferences towards healthier protein sources. Yet, the rapid expansion of aquaculture brings its own sustainability challenges, including limited feed supply, water resource depletion, and vulnerability to climate variability (Pham et al., 2023; Zeller et al., 2018). To sustain this growth, there is a pressing need to adopt innovative technologies that can improve production efficiency while minimising ecological footprints.

Recent policy frameworks emphasise the importance of sustainable aquaculture in achieving global food security and environmental goals. The FAO’s “Blue Transformation” agenda (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2022) advocates for the integration of digitalisation, smart monitoring, and ecosystem-based management to optimise resource use and ensure traceability across aquaculture systems. In this context, aquaculture is not only a food production strategy but also a platform for technological innovation and inclusive economic development. Recognising fish as food rather than merely as a trade commodity can further strengthen nutrition-sensitive policies that align with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (Bennett et al., 2021).

Aquaculture’s expansion offers a viable solution to declining wild fish stocks and the rising global protein demand. However, its rapid intensification has also introduced new challenges that threaten long-term sustainability. Issues such as poor feed management, water pollution, and the spread of diseases can severely impact productivity and environmental quality. Moreover, the growing dependence on artificial feed has placed significant pressure on natural resources, increasing production costs and ecological risks. These factors highlight the importance of transitioning toward more sustainable and technology-driven aquaculture practices that emphasise monitoring, automation, and data analytics (Pernet & Browman, 2021; Zeller et al., 2018).

To support this transition, the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) underscores the role of innovation and digitalisation as part of its “Blue Transformation” strategy (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2024). This initiative promotes the integration of intelligent systems capable of optimising feeding schedules, monitoring water quality, and managing aquatic health parameters in real time. By adopting these approaches, aquaculture can significantly reduce resource waste, improve yield predictability, and maintain ecological balance (Pham et al., 2023; Teh & Pauly, 2018). The FAO’s 2022 report further reinforces this view by encouraging the use of smart sensing, data analytics, and automated decision-support systems to improve transparency and efficiency within the global aquaculture supply chain (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2022).

The recognition of aquaculture’s dual role, as both a food production and a technological advancement, has accelerated the adoption of smart aquaculture systems across Asia. These systems combine environmental sensors, IoT connectivity, and AI to enhance operational precision. In developing countries like Malaysia, small and medium-scale fish farms have begun to implement automation for water quality control, feeding regulation, and production monitoring. However, many of these farms still rely heavily on manual observation and fixed feeding schedules, which can result in inconsistent performance and inefficiencies. Such limitations highlight the urgent need for data-driven management strategies and automated monitoring tools to support consistent and sustainable operations (Bennett et al., 2021).

Ultimately, the global shift towards sustainable aquaculture represents both a necessity and an opportunity. With increasing environmental pressures and growing food demands, the adoption of innovative, AI-assisted aquaculture systems will be essential to achieving the balance between productivity, profitability, and ecological sustainability. This research aligns with these objectives by emphasising the role of intelligent technologies and integrated system design in advancing aquaculture’s contribution to global food security. Through sustainable intensification and smart monitoring, aquaculture can serve as a cornerstone for achieving the FAO’s Blue Transformation vision and the broader Sustainable Development Goals (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2022).

Related works

This research on smart aquaculture is driven by the need to address challenges such as overfishing, climate change, and fish scarcity, as well as farmer concerns regarding water quality, feeding, temperature regulation, and water recycling. To improve aquaculture productivity and sustainability, recent studies have applied machine learning and IoT technologies using sensors and cameras. The ultimate goal is to achieve real-time monitoring and intelligent control of aquaculture environments, leading to higher output and ecological balance (Rahman et al., 2023; Sen et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023). Several studies have focused on IoT-based water quality monitoring. For example, one study measured pH, temperature, and turbidity using dedicated sensors connected to a NodeMCU microcontroller, which transmitted processed data to a server for remote monitoring (Bachtiar, Hidayat & Anantama, 2022).

Similarly, another approach used DS18B20, SEN0161, and SEN0189 sensors connected to an ESP32 microcontroller, sending data to a Firebase cloud database with real-time visualisation and notifications via WhatsApp (Olanubi, Akano & Asaolu, 2024). The IoT-based Smart Aquaculture System (ISAS) integrated four sensors for temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen, and water hardness connected to Arduino and Raspberry Pi devices. Data were transmitted to a cloud database through Message Queue Telemetry Transport (MQTT), enabling users to monitor parameters and automatically operate aerators and feeders using fuzzy rules (Tsai et al., 2022). Beyond water monitoring, some studies combine IoT and data analytics for fish development and health monitoring. For example, real-time data on water quality, oxygen levels, and fish activity were analysed to detect anomalies, diseases, or stress, with results stored in centralised databases for future decision-making (Mandal & Ghosh, 2024). In terms of fish detection, Jalal et al. (2020) combined optical flow and Gaussian mixture models with the YOLO network, achieving high accuracy across two datasets, with F-scores of 95.47% and 91.2%. Similarly, Yang et al. (2021) emphasised CNNs for fish detection and behaviour analysis, noting their robustness to variations in light, translation, and rotation.

Other deep learning applications include the use of Mask R-CNN with ResNet50 for fish movement detection, yielding an F1-score of 91% and mAP50 of 81%, with Seq-NMS providing the best tracking accuracy (Lopez-Marcano et al., 2021). Saleh, Sheaves & Rahimi Azghadi (2022) also showed that CNN-based models improved underwater fish classification compared to traditional methods. Mandal et al. (2023) advanced this further by integrating YOLO with a squeeze-and-excitation CNN, achieving 96.22% accuracy and 93.89% mean average precision on the Fish4Knowledge dataset. Building on these prior works, the present study integrates IoT-based sensor monitoring with YOLO architecture for real-time fish detection. Importantly, the use of YOLO-Tiny variants ensures compatibility with resource-constrained edge devices such as the NVIDIA Jetson Nano, addressing a critical gap in deploying practical, low-power aquaculture systems.

Materials and Methods

Material acquisition

For this experiment, red tilapia, black tilapia, and Amazon sailfin catfish were used as detection subjects. The selection of tilapia species was based on their role as common protein sources in aquaculture, widely raised by fish farmers. The Amazon sailfin catfish was included due to its natural ability to consume moss and algae, contributing to the organic management of water quality within the tank. Both tilapias were obtained from licensed fish farmers in Peramu, Pekan, Pahang, endorsed by Universiti Malaysia Pahang Al-Sultan Abdullah (UIC230807) to conduct research involving animals. The Amazon sailfin catfish was purchased from a licensed aquarium fish shop. There are four black tilapia, one red tilapia, and one Amazon sailfin catfish.

The fish were secured and cared for in a certified fibreglass fish tank equipped with pumps and a water filtration system. The environmental and water conditions were established based on guidance and information obtained from fish growers and aquarium businesses. The fish were fed with recommended quantities at specific times each day. The dataset used in this study comprised 300 annotated images, including representative samples of Red Tilapia (23 instances), Black Tilapia (42 instances), and Sailfin Catfish (11 instances). To mitigate bias, data augmentation techniques such as rotation, flipping, and brightness adjustment were applied during training. Additionally, class weights were incorporated into the loss function to ensure equitable learning across under-represented species. Sample images are accessible via the Zenodo repository at 10.5281/zenodo.15963857.

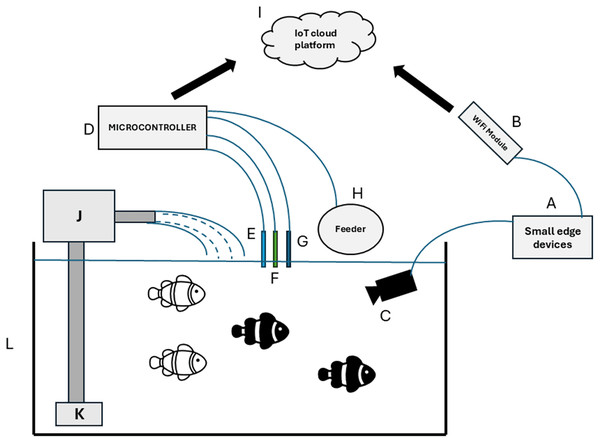

Experimental setup

To achieve the research objectives, a miniature IoT-based aquaculture environment was constructed to mimic real-world conditions. This setup included a tank, pump system, and filtration media to simulate a full-scale operation. The comprehensive system integrates water quality monitoring sensors and an automated fish pellet feeder, all connected to a microcontroller that functions as the system’s central processing unit. The microcontroller collected and processed sensor data while controlling the feeder to maintain optimal water quality and regular feeding, effectively replicating real-world aquaculture settings. In Fig. 1, the YOLO deep learning model is integrated within the NVIDIA Jetson Nano module, which processed live video from an underwater camera to detect and classify fish. This configuration formed the core of the computer vision system, operating in conjunction with the water quality sensors to enable smart aquaculture monitoring.

Figure 1: Conceptual design of miniature IoT-based aquaculture ecosystems.

(A) NVIDIA Jetson Nano 2GB Developer Kit. (B) WiFi USB dongle. (C) Underwater camera. (D) ESP32 Dev Kit. (E) Water quality sensor. (F) Fish feeder. (G) Fiberglass tank. (H) Filtration compartment. (I) Water pump. (J) Ubidots storage.To ensure the success of the research, all hardware and software components were thoroughly examined, including raw data collection and preparation, as well as neural network implementation. These components were categorised into main groups, including mechanical, electronics and microcontrollers, data acquisition, and neural networks. The mechanical category includes physical components such as tanks and pumps, whereas the electronics and microcontroller category encompasses components used for real-time monitoring and control. Data acquisition is the process of collecting and preparing raw data using a variety of sensors and equipment. The neural networks category includes the use of machine learning algorithms for data analysis that can recognise patterns and make predictions. This systematic approach ensures a thorough understanding of the components, which contributes to the project’s success and increases the chances of meeting the study objectives.

Sensors and microcontrollers

Electronics form the foundation of the Internet of Things (IoT), defining IoT systems through key components such as sensors, microcontrollers, and Single-Board Computers (SBCs). These components operate synergistically to establish a robust and efficient system capable of performing a variety of functions. To ensure the success of this research, particular emphasis was placed on a thorough examination of the most fundamental yet critical component, which is the sensors.

Sensors play a crucial role in monitoring water quality within small IoT-based aquaculture systems, as fish health is highly dependent on the quality of their aquatic environment. To maintain optimal conditions, three key parameters were monitored, including water temperature, pH, and dissolved oxygen levels. These metrics provide a comprehensive overview of water quality, enabling necessary adjustments to support fish health and well-being. For this study, DF Robot pH and dissolved oxygen sensors were selected due to their reliability and precision, along with additional water temperature measurements. Each sensor was paired with a breakout board module, acting as a converter between the sensors and the microcontroller. This configuration streamlined system integration and enhanced the efficiency of data collection and processing. In the miniature IoT-based aquaculture system, appropriate nourishment was provided using a fish pellet feeder that delivered food at regular intervals. A standard feeder was modified for seamless IoT integration, primarily by connecting it to the microcontroller. This integration improved feeder functionality, enabling more effective operation control tailored to the specific requirements of the aquaculture system.

The fish pellet feeder operates on a preset schedule, mimicking natural feeding patterns to promote healthy eating habits and prevent overfeeding or underfeeding. Automation ensures that the fish receive the correct amount of food at appropriate intervals. For added flexibility, remote control of the feeder is enabled via a microcontroller, allowing adjustments based on real-time observations. The ESP32 Dev Kit was selected as the microcontroller for sensor readings and feeder control due to its compatibility and ease of integration. Its expansion board simplifies connections with sensors and feeders, reducing setup time and effort. Compared to alternatives such as the Arduino Uno R3, the ESP32 Dev Kit offers faster processing capabilities, enabling efficient data collection and system operation. The built-in Bluetooth and Wi-Fi features eliminate the need for additional modules, minimising system complexity and potential failure points. This wireless connectivity also supports flexible system placement and remote access. The Arduino Integrated Development Environment (IDE) and the ESP32 library were used to program the ESP32 Dev Kit, providing a reliable and user-friendly environment for software development and debugging. Additionally, the ESP32 Dev Kit features a baseboard that supports 12V DC voltage input, offering more versatile power supply options, particularly beneficial in settings with limited conventional power sources. The underwater camera is a key component of the system, providing real-time visual data for monitoring fish health and behaviour, as well as detecting potential issues. The selected camera was required to withstand long-term immersion to ensure consistent and reliable data collection. Furthermore, the camera needed the ability to transmit video over extended distances, ideally up to 50 m, to facilitate flexible installation and effective monitoring. For this study, a fishing camera with a 10-m range was utilised, which was suitable for the compact IoT-based aquaculture setup. This camera, capable of recording at 720p resolution and 60 FPS, enables close monitoring of fish and their habitat with fine detail. It includes 15 LEDs for both white and infrared illumination to ensure clear footage under varying lighting conditions. The camera connects via an RCA connector, requiring the use of a USB-to-RCA converter for integration with the research SBCs. This configuration provides a stable, high-quality video feed, facilitating effective monitoring and management of the aquaculture system.

The NVIDIA Jetson Nano 2 GB Developer Kit was chosen as the SBC due to its capabilities and compatibility with the system. It features a quad-core ARM Cortex-A57 MP Core processor for CPU operations and 128 NVIDIA CUDA cores for GPU tasks, offering substantial computational power for complex processing and efficient data handling. With 2 GB of 64-bit LPDDR4 RAM, the device provides sufficient memory for application execution and temporary data storage. For permanent storage, it utilises a microSD card with a minimum recommended size of 32 GB, capable of accommodating large datasets, including video streams from the underwater camera. The Jetson Nano offers multiple interfaces, including display, LAN, and USB ports, enabling straightforward integration with diverse devices and systems, thereby enhancing adaptability and flexibility. Its ability to perform deep learning neural network inference makes it particularly suited for this research, enabling real-time analysis of video feeds from the underwater camera and supporting fish detection and identification within the miniature IoT-based aquaculture environment.

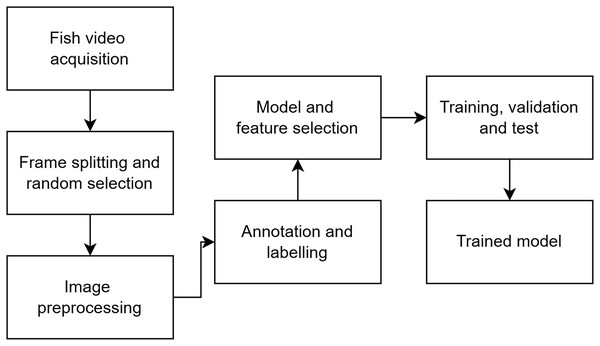

Data acquisition and neural networks

The fundamental goal of this study is to use computer vision to reliably detect and identify several fish species in a tiny IoT-based aquaculture ecosystem. Figure 2 depicts a detailed flowchart of the data collection and model training process.

Figure 2: Data acquisition and training flowchart.

The procedure begins with the real-time capturing and storing of video footage of diverse fish species using an underwater camera linked to a laptop via a USB-to-RCA converter. After capturing the video data, it is divided into individual frames. Each frame is then transformed into a static image, revealing a thorough snapshot of the fish’s behaviour and physical attributes at certain points in time. Following the conversion of video frames into images, the images undergo a preprocessing phase that includes noise reduction, contrast enhancement, and colour normalisation to improve their quality and prepare them for analysis. Following preprocessing, the photos are annotated and labelled using Open Labeling, which entails manually identifying and tagging aspects within the images, such as fish kind, size, and location. This labelled data is subsequently used as the ground truth in the model training phase. Following image annotation and labelling, model and feature selection are performed to maximise detection accuracy, which includes selecting the best machine learning model and relevant characteristics for accurate fish species identification. The image dataset is then divided into separate subsets for training, validation, and testing. This division, which is often done in a precise ratio, ensures that the model is exposed to different data during training while reserving unseen data for validation and testing.

The result of this procedure is a trained model capable of accurately recognising and classifying fish species within a tiny IoT-based aquaculture ecosystem. The model is ready for real-world deployment, providing vital information for optimal aquaculture management and sustainability. The model was trained, validated, and tested on a high-performance desktop computer powered by an Intel Xeon E3-1281 v3 CPU, an RTX3060 12GDDR6 GPU, and 32 GB of DDR3 RAM. This technology ensures that data is processed and analysed efficiently, allowing for more precise fish species detection and identification. In this study, machine learning techniques were employed, focusing on Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) based on the YOLO architecture family to accurately recognise and identify fish species. The YOLO family was selected due to its widespread adoption among automation developers and its strong performance in object detection tasks. Renowned for its real-time object recognition capabilities, the YOLO architecture represents an excellent candidate for implementation in this research.

Four Darknet YOLO architectures, including YOLOv3-Standard, YOLOv3-Tiny, YOLOv4-Standard, and YOLOv4-Tiny, were trained to evaluate the trade-offs between accuracy and computational efficiency, which are critical for IoT deployment. Although newer versions like YOLOv11 offer enhanced efficiency, these established architectures were chosen for their proven compatibility with edge devices like the Jetson Nano and to maintain continuity with previous aquaculture studies. The ‘Standard’ and ‘Tiny’ variants differ in the number of convolution layers, with the latter offering greater computational efficiency due to its reduced layer count. For all architectures, the dataset comprising 210 training images, 60 validation images, and 30 testing images was processed through 5,000 iterations. The selection of 5,000 iterations was empirically determined by observing loss trends during preliminary training runs, ensuring model convergence while balancing computational efficiency, as additional iterations yielded negligible improvements in validation loss.

Evaluation method

A machine learning model’s development process involves an integrated evaluation of detection performance, typically carried out during the training, validation, and testing phases, often supported by a confusion matrix. This statistical tool visualises and quantifies the algorithm’s performance by comparing the model’s predictions with the actual values. It includes four main metrics, including True Positives (TP), False Positives (FP), True Negatives (TN), and False Negatives (FN), which together provide a comprehensive picture of the model’s performance across various circumstances.

The model’s performance was assessed using TP, FP, TN, and FN, which represent correct and incorrect predictions of positive and negative classes, respectively. These values were used to calculate key metrics such as Precision (or Positive Predictive Value), which evaluates the proportion of correct positive predictions, and Recall (or Sensitivity, Hit Rate, True Positive Rate), which measures the proportion of actual positives correctly identified. The F1-score, defined as the harmonic mean of Precision and Recall, provides a balanced single metric that is particularly useful in scenarios where both false positives and false negatives carry significant consequences. The AP, Recall, and F1-scores provide critical information about the models’ performance. They are determined using Eqs. (1)–(3) accordingly. These metrics are solid indicators of the model’s capacity to reliably recognise and classify fish species, guiding future system enhancements and refinements.

(1)

(2)

(3)

The evaluation phase of the YOLO architecture consisted of three key stages, which are training, post-training performance evaluation, and real-world application testing. During the training phase, the models were trained on a labelled dataset containing bounding boxes for various fish species, including Red Tilapia, Black Tilapia, and Sailfin Catfish. Training parameters were optimised to ensure robust learning across all YOLO variants (YOLOv3, YOLOv3-Tiny, YOLOv4, and YOLOv4-Tiny). Post-training performance evaluation involved applying the trained models to unseen test data to measure their generalisation capabilities. At this stage, the models were assessed using critical metrics, including Average Precision (AP), Recall, F1-score, Average intersection over union (IoU), and [email protected]. The evaluation was designed to highlight the strengths and weaknesses of each architecture, with a focus on their detection and localisation capabilities. Each model’s ability to accurately detect and classify fish species was compared, with the results meticulously documented to identify patterns and performance trends. Finally, real-world evaluation was conducted on a randomly selected image containing one Red Tilapia, two Black Tilapia, and one Sailfin Catfish. This step simulated practical deployment by evaluating how well the models performed on previously unseen data under realistic conditions. By comparing the outcomes from this phase with the metrics derived during training and testing, the evaluation provided a comprehensive understanding of each architecture’s performance and suitability for implementation in IoT-based aquaculture systems.

Dashboard

This study examines a miniature IoT-based aquaculture ecosystem equipped with sensors that continuously monitor and record multiple parameters, providing real-time data critical for rapid adjustments to current conditions. To display these real-time values, a cloud-based data storage system is proposed as a secure and reliable repository for sensor data. This system ensures real-time accessibility for analysis and visualisation, while maintaining scalability to accommodate increasing data volumes as the ecosystem’s complexity and size expand. Sensor data from the aquaculture ecosystem is presented on a user-friendly dashboard, accessible from various devices, serving as the primary interface for users to interact with and comprehend the ecosystem’s status. The dashboard functions as a Human-Machine Interface (HMI), incorporating Graphical User Interfaces (GUIs) that enable intuitive interaction for effective system control and monitoring. The robust and versatile Ubidots platform was used to design the dashboard’s User Interface (UI) and User Experience (UX), offering a comprehensive suite of tools and features for creating a customised, interactive dashboard tailored to IoT-enabled aquaculture environments. The Ubidots dashboard displays critical metrics such as water temperature, pH, and dissolved oxygen levels and also manages the fish pellet feeder, all of which directly influence the health and growth of aquatic species. This integration of sensor technologies, cloud-based data storage, and intuitive GUIs demonstrates significant advancements in aquaculture technology, providing a powerful tool for ecosystem management with potential applications across various settings.

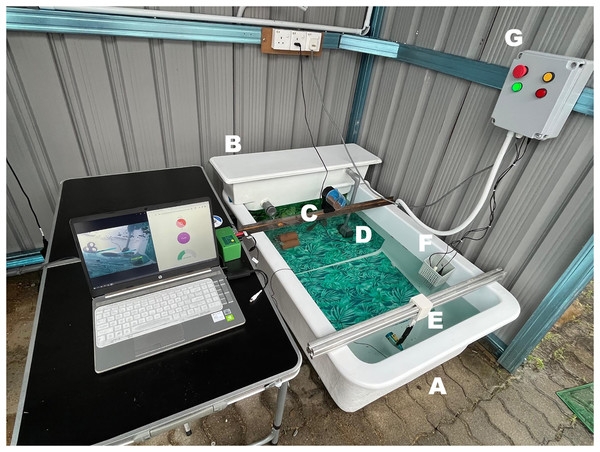

Results

Following an exhaustive study and the procurement of necessary components, the construction, installation, and setup of the miniature IoT-based aquaculture ecosystem were carried out. This process involved meticulous assembly of all components to ensure proper installation and functionality. The setup was designed to replicate a real-world aquaculture ecosystem on a smaller scale, enabling controlled experiments and observation of fish species’ behaviour and interactions within the environment. The system was equipped with essential elements to support fish life and growth, including a water filtration system, temperature regulation, and appropriate lighting. After the setup was completed, a series of experiments were conducted to assess the effectiveness of the computer vision and machine learning techniques in detecting and identifying fish species. These experiments evaluated the accuracy, speed, and reliability of the methods under varying conditions and scenarios. The fully assembled miniature IoT-based aquaculture ecosystem is illustrated in Fig. 3, which provides a detailed representation of the setup and component arrangement. The figure highlights the system’s key parts, including A (tank), B (filtration system), C (pellet feeder), D (pump), E (camera), F (sensors), and G (controller box), underscoring the rigorous planning and execution involved in the development of this research platform, which serves as the foundation for subsequent experiments and findings.

Figure 3: Complete build of miniature IoT-based aquaculture ecosystem.

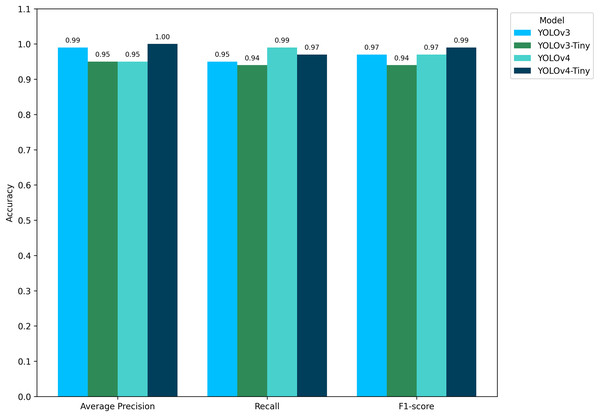

The performance results of the selected YOLO family architectures, post-training, were meticulously recorded. These results are presented in Tables 1 and 2. Upon analysing Table 1, it was observed that the highest Average Precision (AP) and F1-score were achieved by the YOLOv4-Tiny architecture, with an approximate value of 1.00. This indicates that the YOLOv4-Tiny model was highly precise in detecting and identifying fish species within the miniature IoT-based aquaculture ecosystem and maintained a high balance between precision and recall, as indicated by the F1-score. Conversely, the lowest AP and F1-score were a tie between the YOLOv3-Tiny and YOLOv4-Standard architectures, both yielding an approximate value of 0.95. Despite being the lowest, their scores remain high, demonstrating the effectiveness of these models. In terms of Recall, the highest value was obtained by the YOLOv4 architecture, with an approximate value of 0.99. This suggests that the YOLOv4 model was able to correctly identify a high proportion of actual positives (true positives) among all actual positive cases. Conversely, the lowest Recall was attributed to the YOLOv3-Tiny model. Figure 4 provides a visual representation of the results shown in Table 1. Among all models, YOLOv4-Tiny achieved the best balance between detection accuracy and real-time performance. Although YOLOv4-Standard provided slightly higher IoU and mAP values, its larger size and slower inference speed made it less suitable for resource-constrained devices such as the Jetson Nano.

| Model | Class | Average precision | TP | FP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv3 | Red | 99.82 | 22 | 1 |

| Black | 98.91 | 40 | 0 | |

| Cleaner | 91.67 | 11 | 0 | |

| YOLOv3-Tiny | Red | 99.82 | 22 | 1 |

| Black | 94.03 | 39 | 3 | |

| Cleaner | 91.67 | 11 | 0 | |

| YOLOv4 | Red | 100.00 | 23 | 0 |

| Black | 99.94 | 42 | 4 | |

| Cleaner | 91.67 | 11 | 0 | |

| YOLOv4-Tiny | Red | 100.00 | 23 | 0 |

| Black | 99.75 | 41 | 0 | |

| Cleaner | 91.67 | 11 | 0 |

| Model | Average IoU | [email protected] |

|---|---|---|

| YOLOv3 | 84.41 | 96.80 |

| YOLOv3-Tiny | 76.63 | 95.17 |

| YOLOv4 | 84.57 | 97.20 |

| YOLOv4-Tiny | 82.40 | 97.14 |

Figure 4: Performance chart for AP, Recall and F1-score.

A detailed examination of Table 1 reveals the detection accuracy of each fish species across the selected YOLO architectures. The table presents a comparative analysis of the performance of the different YOLO models in accurately detecting and identifying various fish species. In this context, the Red Tilapia (denoted as ‘Red’) exhibits the highest detection accuracy for both YOLOv4-Standard and YOLOv4-Tiny architectures, with an approximate value of 100%. This suggests that these models are highly effective in detecting and identifying Red Tilapia within the miniature IoT-based aquaculture ecosystem. On the other hand, the Sailfin Catfish (denoted as ‘Cleaner’) exhibits the lowest detection accuracy across all selected YOLO architectures, with a value of approximately 91.67%. Although this remains a high accuracy score, it is lower compared to the other fish species. This discrepancy in detection accuracy may be attributed to factors such as water clarity and lighting conditions. The Sailfin Catfish, characterised by its dark black and green colour, may be more challenging to detect under certain lighting conditions or in water with low clarity. This finding highlights the importance of considering environmental factors when developing and deploying computer vision systems in real-world scenarios. It is also confirmed that species with darker colouration or low visual contrast are more difficult to detect in underwater environments, reinforcing the importance of accounting for environmental factors, such as turbidity and illumination, when deploying vision-based systems in real aquaculture settings.

A detailed examination of Table 2 highlights the performance of the selected YOLO architectures in terms of Average Intersection over Union (IoU) and mean Average Precision at 50% overlap ([email protected]). The Average IoU is a metric that measures the overlap between the predicted bounding box and the ground truth bounding box. A higher Average IoU indicates a more accurate object localisation by the model. In this case, YOLOv4-Standard architecture achieved the highest Average IoU value of approximately 84.57, indicating a high degree of localisation accuracy.

On the other hand, the [email protected] is a metric that measures the model’s detection accuracy at a 50% overlap threshold, with higher values indicating higher detection accuracy. Here, the YOLOv4-Standard architecture also achieved the highest [email protected] value of approximately 97.2, demonstrating its superior detection accuracy. Conversely, the YOLOv3-Tiny architecture yielded the lowest Average IoU and [email protected] values, with approximately 76.63 and 95.17, respectively. While these are still high scores, they are lower compared to the other architectures, indicating slightly lower performance in terms of object localisation and detection accuracy.

The meticulous evaluation of various metrics, as presented in Table 2, ensures that the research is firmly grounded in empirical evidence. In addition to detection performance, the study evaluated model efficiency by analysing parameters such as model size (YOLOv4-Tiny: 23 MB, YOLOv4-Standard: 244 MB), FLOPs (YOLOv4-Tiny: 5.6 GFLOPs, YOLOv4-Standard: 59.5 GFLOPs), and inference speed (YOLOv4-Tiny: 8 FPS, YOLOv4-Standard: 3 FPS on Jetson Nano). These metrics highlight the trade-offs between accuracy and computational demand, which are crucial for IoT deployment. The insights gained from this comprehensive analysis offer a clear understanding of YOLO architectures’ performance in fish species detection, revealing each model’s strengths and weaknesses. These findings guide future system improvements by identifying optimal architecture choices to enhance aquaculture sustainability and management, contributing to environmental conservation goals. In general, while the standard YOLO models delivered slightly higher localisation accuracy, the YOLO-Tiny variants proved more practical for IoT deployment. Their smaller size, faster inference speed, and lower hardware demands make them well-suited for continuous real-time monitoring in aquaculture, where rapid decisions about feeding and aeration are essential.

Overall, this study demonstrates the transformative potential of integrating advanced machine learning techniques like YOLO architectures into aquaculture, showcasing how empirical research drives innovation in this critical field. Upon completion of the training phase for the selected YOLO architectures, the trained models were applied to a random image that had not been used during the training, validation, or testing phases. This image contained one red tilapia, two black tilapia, and one sailfin catfish. The purpose of this evaluation was to assess the post-processing performance of the models on previously unseen data.

The outcomes of this experiment were meticulously documented and are presented in Table 2. This table provides a quantitative analysis of the model’s detection accuracy for each fish species across different versions of YOLO architecture. Specifically, it compares YOLOv3, YOLOv3-Tiny (a smaller and faster version), YOLOv4, and YOLOv4-Tiny. The results indicate that both versions of YOLOv4 achieved perfect detection with a score of 1 for all fish categories. Meanwhile, YOLOv3 exhibited slightly lower performance with scores ranging from 0.95 to 0.97 for detecting red tilapia and cleaner fish, respectively, but maintained a perfect score in identifying black tilapia. The Tiny versions showed marginally reduced efficacy compared to their full-sized counterparts but still performed remarkably well, with scores above 0.9 across all categories. Real-time testing showed YOLOv4-Tiny achieved the best speed (8 FPS) on the Jetson Nano, followed by YOLOv3-Tiny (6 FPS), YOLOv4 (3 FPS), and YOLOv3 (2 FPS). While all models maintained perfect detection (1.00 score), YOLOv4-Tiny’s 2.6× faster performance than YOLOv4 made it ideal for IoT devices, despite slightly lower precision (0.95 vs. 1.00 AP). This speed-accuracy trade-off directly reflected each model’s complexity, with simpler ‘Tiny’ versions being significantly faster but less precise than their standard counterparts.

A critical examination of the hardware capabilities, particularly in the context of the Jetson Nano, a model recognised as one of the most basic and dated within NVIDIA’s range of SBCs, indicates a deficiency in alternative methodologies that could further enhance the efficiency of trained models within the hardware constraints of SBCs. According to the information available on NVIDIA’s official website, there is a noticeable absence of supplementary techniques that could be leveraged to optimise model performance for such limited hardware specifications.

The implications of this hardware limitation are profound, as they impede the model’s ability to process data at a rate comparable to more advanced computing systems. This bottleneck is particularly evident when deploying complex machine learning models like YOLOv4, which are inherently resource-intensive due to their sophisticated algorithms and the extensive amount of data they process. To address these challenges, it is imperative to explore innovative strategies that can reconcile the high computational demands of advanced detection models with the modest capabilities of SBCs. Such strategies may include the refinement of the model’s architecture to reduce computational overhead, the implementation of model quantisation techniques to decrease the precision of the calculations without significantly compromising accuracy, or the utilisation of network pruning methods to eliminate redundant parameters that contribute minimally to model performance.

During this research, an experiment was successfully conducted using a miniature IoT-based aquaculture ecosystem equipped with various sensors. These sensors continuously monitored and recorded critical parameters within the ecosystem, providing a steady stream of real-time data. The data, including the operation of the fish pellet feeder, were visualised for users through the Ubidots platform.

Discussion

The empirical evidence from recent research experiments substantiates the practicality of integrating Internet of Things (IoT) technologies within aquaculture ecosystems. This feasibility is supported by the utilisation of contemporary technologies, including microcontrollers, SBCs, cloud storage platforms, and architecture based on CNNs. The domain of detection and identification has demonstrated substantial accuracy in performance, particularly with post-processing techniques. Nonetheless, the scope of real-time monitoring necessitates additional developmental efforts to refine accuracy and enhance the FPS rate during the detection phase. This enhancement can be achieved by transitioning the trained model to advanced reinforcement learning frameworks such as PyTorch, ONNX, or TensorRT formats. Such a transition would leverage the iterative and adaptive nature of reinforcement learning to optimise the model’s performance in dynamic and unpredictable environments.

Furthermore, it is advocated that the IoT system should be expanded to include functionalities that are pivotal for comprehensive aquaculture management. These functionalities encompass the precise measurement of fish size, which is integral for assessing growth rates and managing stock levels. Additionally, the system should be capable of detecting fish diseases and identifying waterborne pathogens, which are critical for maintaining the health of the aquatic biota and ensuring the sustainability of aquaculture operations. The limitations of white and infrared LEDs in capturing clear underwater imagery are primarily due to disturbances in water clarity, such as debris and variable light intensities. These factors can significantly degrade the quality of visual data obtained, which is critical for accurate detection and identification of aquatic life.

To address these challenges and enhance the capabilities of underwater vision systems, it is proposed to integrate or combine existing camera vision features with advanced imaging technologies. The use of RGB-D cameras, which provide colour (RGB) and depth (D) information, or stereo cameras, which employ two lenses to simulate human binocular vision, could substantially improve the system’s ability to discern and classify objects in complex underwater environments. Additionally, the implementation of Time of Flight (ToF) cameras, which measure the time taken for light to travel from the camera to the subject and back, can offer precise distance measurements, contributing to better spatial understanding and object recognition. Another promising avenue is the incorporation of blue or green laser LEDs in conjunction with Light Detection and Ranging (LIDAR) technology. The specific wavelengths of blue and green lasers are known to penetrate water more effectively, thereby enhancing the system’s capacity to map and detect objects even in turbid water conditions.

Incorporating these technologies into underwater vision systems could revolutionise aquatic monitoring by providing researchers with more reliable and detailed data. This would enable better informed decisions in fish population management, habitat assessment, and environmental monitoring. While the system achieved high accuracy (97.2 [email protected]), its generalisability to diverse species and turbid water conditions requires further validation. This study demonstrates promising results, but several limitations should be noted. First, the experiments were conducted in a controlled tank environment. Perdormance in open water or turbid conditions remains untested. Second, the dataset, though annotated, is limited in size (300 images) and diversity (three species), which may affect broader applicability. Lastly, the hardware constraints of the Jetson Nano restrict real-time performance (3–8 FPS for YOLOv4-Tiny), necessitating further optimisation for commercial-scale deployment. Future work will expand the dataset to include varied aquatic environments and explore dynamic adaptation techniques, such as online learning, to enhance real-world robustness. While the experiments were conducted in a controlled tank environment, scalability to full-scale aquaculture farms will require further validation. Larger production systems introduce challenges such as turbid water, variable lighting, and wider monitoring areas, which may reduce detection accuracy. Additionally, deployment costs, connectivity, and long-term maintenance must be considered when implementing IoT–AI systems in commercial farms. Addressing these issues through dataset expansion, hardware optimisation, and field trials will be essential for real-world adoption.

Conclusions

This study outlines the conception and fabrication of compact IoT-based ecosystems tailored for aquaculture applications. Through meticulous research and empirical studies, ecosystems were engineered to closely emulate the natural habitats found in specific locales. These systems possess the capability to continuously monitor water quality parameters, detect the presence of fish species, and facilitate the remote operation of fish pellet dispensers. Despite these advancements, real-time detection and identification of aquatic fauna remain challenging. The system currently achieves a modest frame rate of 3–8 FPS (YOLOv4-Tiny) to 10 FPS (optimised configurations) in real-time, as documented in Fig. 4. In contrast, post-processing operations significantly enhance performance, achieving frame rates of up to 120 FPS. This disparity highlights a critical area for future investigation and optimisation. Regarding computational hardware, selected Single-Board Computers (SBCs) demonstrated efficacy in object detection tasks. Notably, the NVIDIA Jetson Nano exhibited consistent performance, detecting and identifying objects at an average rate of 60 to 90 FPS in benchmark tests. These results underscore the potential of SBCs to enhance the responsiveness and accuracy of real-time monitoring systems within aquaculture ecosystems. The trajectory of future research is clear, which is to augment real-time processing capabilities to match post-processing efficiency (120 FPS). Priority directions include: (1) model optimisation through quantisation and pruning, (2) hardware acceleration via TensorRT, and (3) adaptive learning techniques. This work lays the foundation for scalable, IoT-driven aquaculture systems, with potential applications in commercial farms and conservation efforts. Addressing hardware and algorithmic optimisation will be critical to advancing global food security and sustainable resource management.

In summary, this study makes three key contributions, including (1) the integration of IoT-based sensors with YOLO architectures for simultaneous water quality monitoring and fish detection, (2) demonstration that YOLOv4-Tiny offers the best trade-off between accuracy and real-time performance on resource-constrained devices such as the Jetson Nano, and (3) identification of practical limitations and scalability considerations, providing directions for future research toward commercial aquaculture applications.

Supplemental Information

Oreochromis niloticus (tilapia) and Anabas testudineus (puyu) inside a controlled aquaculture pond.

Water quality such as temperature, dissolved oxygen, and turbidity is regulated to maintain consistent conditions. The image was captured for dataset creation and annotation for the fish detection and counting study.

YOLO annotation file.

Each line represents a fish instance using normalized values in the format: class_id x_center y_center width height It contains two objects from class 0 and one from class 1. The annotations support model training for accurate fish localization and classification.

YOLO-formatted bounding-box annotations.

Each line follows: class_id x_center y_center width height All values are normalized. The file includes two objects of class 0 and one of class 1. These annotations are used to train the YOLO model for fish detection.