Development of hybrid approach for named entity recognition in Uzbek language text

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Nicole Nogoy

- Subject Areas

- Algorithms and Analysis of Algorithms, Artificial Intelligence, Computational Linguistics, Data Mining and Machine Learning, Neural Networks

- Keywords

- Uzbek language, Natural language processing, Named entity recognition, Turkic language, Artificial intelligence

- Copyright

- © 2026 Mengliev et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2026. Development of hybrid approach for named entity recognition in Uzbek language text. PeerJ Computer Science 12:e3489 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3489

Abstract

During the article a hybrid named-entity recognition (NER) algorithm for Uzbek is presented. It combines rule-based modules (transliteration, dialect normalization, morphological analysis) with modern neural network models. The study is motivated by Uzbek’s agglutinative morphology, dialect diversity and the lack of specialized resources, which hinder the direct application of named entity recognition methods developed for English or other high-resource languages. As part of the work, an annotated corpus of more than three thousand sentences in the Uzbek language was formed, including legal documents, scientific articles, news materials and informal texts from social networks. The corpus is marked up according to the BIOES scheme taking into account the specific morphological and lexical features of the Uzbek language. The developed rule-oriented algorithms (transliteration, dialect standardization, morphological analysis) are integrated into a single post-processing system that complements neural network models. As a result of experiments aimed at assessing the effectiveness of the proposed approach, it was found that the hybrid approach significantly improves the accuracy and completeness metrics of named entity recognition in different thematic domains. The practical value of the study is that the proposed system can serve as a basis for automatic processing of Uzbek texts in the tasks of searching and extracting information, dialect normalization, annotating large text data and digitalization of document flow. The theoretical significance is that the work expands approaches to named entity recognition for low-resource languages, offering methods that take into account morphological-syntactic and dialectal features.

Introduction

The Uzbek Internet sector is growing rapidly, generating large volumes of data that require reliable processing algorithms (Mengliev et al., 2024b, 2024c). In particular, e-commerce is expanding, with more platforms and users entering the market (KPMG, 2023). However, most services still rely on human assistants rather than artificial intelligence (AI) chatbots due to the lack of digital resources, tools for text classification, and systems for extracting key information from user comments (Kuriyozov et al., 2019; Matlatipov et al., 2024).

The urgency of this problem is reinforced by the presidential decree on digitalizing Uzbekistan’s healthcare system, which requires complete digitization of clinics, hospitals, and pharmacies, along with the introduction of more than ten information systems (Mengliev et al., 2024d; LexUz Online). This creates new challenges for automatically processing prescriptions, patient histories, and other medical data, while Uzbek-language solutions remain underdeveloped compared to other languages (MacLean & Cavallucci, 2024; Onishi et al., 2024; Ghimire & Amsaad, 2024).

We propose a hybrid approach to named entity recognition (NER) in Uzbek that combines rule-based methods (transliteration, dialect normalization, morphological analysis) with modern neural architectures (Attention-bidirectional long short-term memory conditional random field (BiLSTM-CRF), multilingual Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (mBERT, convolutional neural network-bidirectional long short term memory (CNN-BiLSTM), SpaCy)). Such integration is expected to yield higher accuracy and completeness than individual models, while addressing the agglutinative nature of Uzbek and its dialectal and orthographic variation—key issues for low-resource languages.

About Uzbek language

The Uzbek language is the official language of the Republic of Uzbekistan, and by its nature belongs to the Turkic language family, where most languages are agglutinative (Mengliev, Barakhnin & Abdurakhmonova, 2021). The property of agglutinativity itself implies the formation of word forms by concatenating affixes (endings) to the root of the word (Sharipov et al., 2022, 2023). Thus, we can get a word in another case or tense (past, present, etc.). For example, consider the word uy (house):

here, we added -lar (plural ending) and -imiz (possessive ending), after which we got the word uylarimiz (our houses) (Madatov, Bekchanov & Vici, 2023).

Moreover, compared to other related Turkic languages, such as Kazakh or Turkish, the agglutinative nature of Uzbek has become so prominent that the addition of affixes can even result in a word with a completely different meaning (Gilmullin et al., 2024). For instance, starting with the word oq (white):

adding the affix -lash (a verbalizing suffix) produces the verb oqlash (to whiten), while adding the affix -landi results in oqlandi (justified). If we instead add the affix -ladi, we get the word:

which can be translated as justified, in the sense of fulfilling. This is commonly used in phrases such as: umidimni oqladi (fulfilled my hope).

Furthermore, it is important to specifically highlight the dialectal forms of the Uzbek language (Raxmatova & Kuzibayeva, 2021). While dialects primarily exist in spoken language, their influence can also be observed in written texts (Turaeva, 2015). For example, imagine a dialogue between three users in a social messenger. Each of these users predominantly communicates in their “own” Uzbek dialect, specifically the Karluk (standard Uzbek), Kipchak, and Oghuz dialects (Mengliev et al., 2024a).

In practice, it is quite common to encounter situations where each of the aforementioned users employs their dialect during a conversation. For clarity, a table (Table 1) is provided below, showcasing words in different Uzbek dialects along with their translations. The Kipchak dialect predominantly dominates in the Autonomous Republic of Karakalpakstan, while the Oghuz dialect is actively used in the Khorezm region (a neigh-boring area to Karakalpakstan and Turkmenistan) (Mengliev et al., 2023a).

| No. | Karluk word | Oghuz | Kypchak | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sabzi | Gashir | Geshir | Carrot |

| 2 | Ona | Opa | Ana | Mother |

| 3 | Qanday | Nichik | Qanday | Which? |

| 4 | Yengil | Ongsot | Jenil | Easy |

| 5 | Unaqa | Bundin | Unday | Such |

Related works

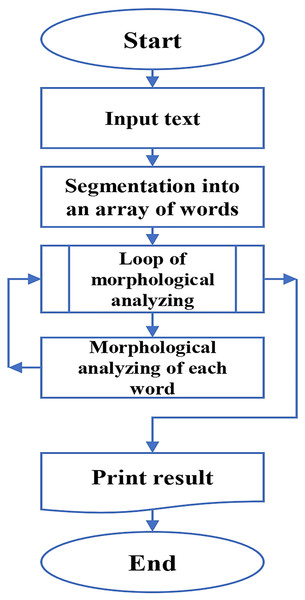

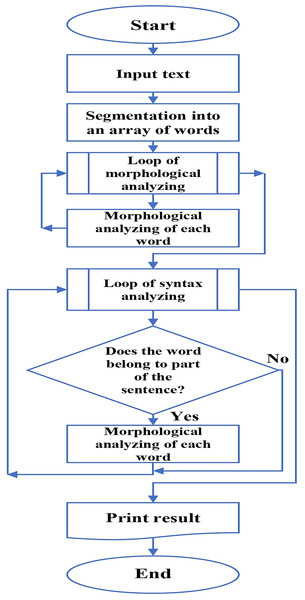

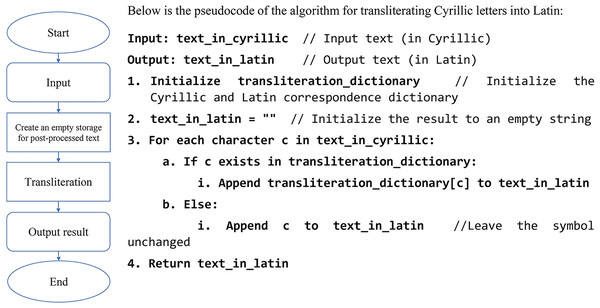

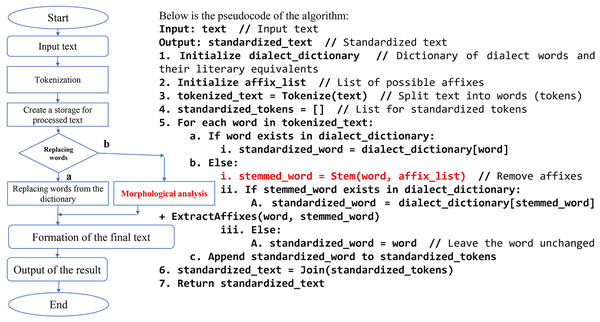

Research on named entity recognition (NER) in Uzbek remains limited. Early studies relied on rule-based methods and gazetteers (Mengliev et al., 2023b), using morphological and syntactic analysis. While this improved recognition of entities not present in dictionaries, accuracy remained modest (68%). The working schemas of the algorithms are illustrated in Figs. 1 and 2, respectively. Another work (Elov & Samatboyeva, 2023) introduced Uzbek NER Analyzer, a desktop tool that applies a dictionary-based algorithm, with plans for future integration of machine learning.

Figure 1: Scheme of the 1st algorithm’s work.

Figure 2: Scheme of the 2nd algorithm’s work.

In the broader Turkic context, Kazakh researchers have explored statistical and neural approaches. For example, one study built a corpus of 9,723 news records and trained a neural network to identify settlements, achieving about 85% accuracy (Mansurova et al., 2019). However, the scope was limited to geographical entities.

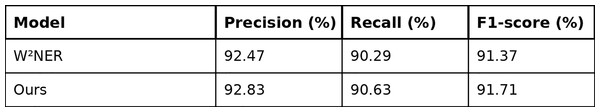

More recently, advanced neural architectures have been applied to Uzbek. In Yusufu et al. (2023), a BERT-based model with convolutional layers and a co-predictor module was trained on over 11,000 sentences (402 k tokens). Using Grid Tagging, the model achieved strong results (Precision 92.83%, Recall 90.63%, F1 = 91.71%). These approaches, however, remain purely neural without hybrid elements. The results of testing are shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Performance comparison between the proposed approach and a selected state-of-the-art NER model.

Values for W2NER are taken from Yusufu et al. (2023).Hybrid NER methods are rare in Uzbek but have shown promise elsewhere. A Chinese study (Ji, Liu & Li, 2019) combined BiLSTM-CRF with attention, rules, and dictionary-based modules for electronic medical records. This hybrid design improved F1-scores by 3–5% and reduced errors in complex cases, demonstrating the benefits of combining statistical and neural techniques.

Proposed approach

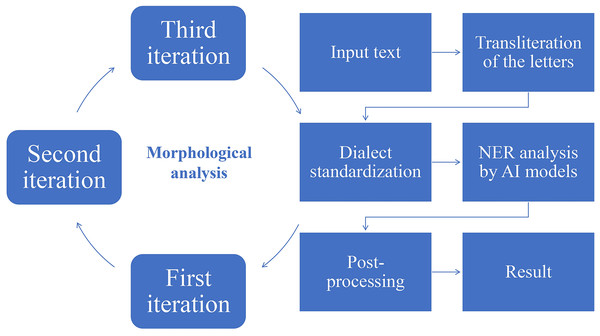

As part of the research, several rule-based algorithms were developed, including a letter transliteration algorithm, a dialect word replacement algorithm, a morphological analysis algorithm, and a post-processing algorithm. For named entity recognition in preprocessed text, three language models were selected: a model based on mBERT, a com-bination of convolutional neural networks with bidirectional LSTM, and the SpaCy library. A comprehensive overview of how these algorithms work is illustrated in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Full approach of the text analysis.

Rule-based algorithms

Letter translation algorithm

The preprocessing stage begins by checking each character in the text to determine whether it is Cyrillic. If so, the algorithm replaces the Cyrillic character with its Latin equivalent. The pseudocode and flowchart of this algorithm are shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: Algorithm for transliteration of Cyrillic letters into Latin.

Dialect word replacement algorithm

Once the text has been transliterated, it is processed by an algorithm that searches for and replaces dialect words with their Karluk (standard Uzbek) equivalents. Initially, the algorithm uses a dictionary-based approach, replacing successfully identified dialect words with their equivalents from the dictionary. If the algorithm cannot find an equivalent, it performs a morphological analysis to extract the root of the word and repeats the replacement steps. If a match is found, the word is replaced. Otherwise, the morphological analysis is repeated (up to three iterations in total). If the third iteration is unsuccessful, the algorithm skips the word. The pseudocode and flowchart for this algorithm are shown in Fig. 6.

Figure 6: Algorithm for dialect standardization.

Dialect normalization is applied strictly before tokenization and Begin, Inside, Outside, End, Single (BIOES) labeling. Replacements operate on whitespace-delimited tokens using a longest-match strategy with stem-aware look-ups; after substitution we re-tokenize and recompute character offsets, so BIOES boundaries are aligned to the post-normalized token sequence (no insertion/deletion of whitespace is allowed to avoid span drift). In addition, The source of dialectical words in the dataset was a book, which was written by F. Abdullaev in 1965, published by the A.S. Pushkin Institute of Language and Literature of the Academy of Sciences of the Uzbek SSR. The dataset was compiled with the participation of linguistic experts and native speakers of this dialect. The dataset contains 2,249 words and terms, as well as information on the geographical location of each word. For example, a dialect word can be used either in all regions of the Khorezm region, or in certain ones. It should be noted that the Oghuz dialect of the Uzbek language (the words and terms of which are contained in the dataset) dominates not only in the Khorezm region (with more than 2 million speakers) of Uzbekistan, but also in the Tashkhauz region of Turkmenistan, where the number of speakers is more than 0.5 million people. The dataset is available at Mengliev (2025a).

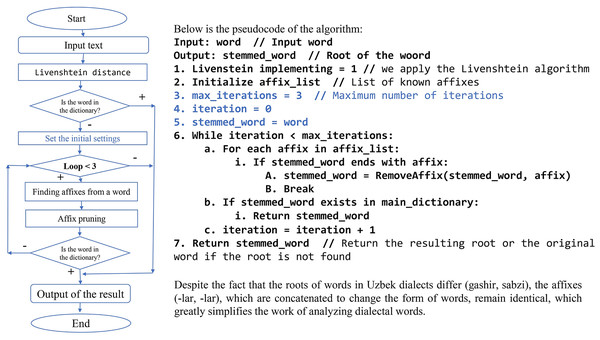

Morphology analysis

The morphological algorithm involves the use of the “Lievenshtein” algorithm, which allows you to identify the difference between letters in a word. The parameter for this algorithm is set to 1, that is, if one letter in a word is written incorrectly, it is automatically replaced with the correct equivalent. Words are checked using a dictionary approach, using a dialect word database, where if successfully detected, the word is replaced with a Karluk (standard Uzbek) version. Otherwise, the word is subject to stemmatization, where the root of the word is identified by cutting off affixes. The root of the word is looked up in the dictionary of stems and compared with the dictionaries of dialect words, where if successfully detected, the dialect word is replaced, otherwise the stemming process is repeated. In total, the stemming process works up to three iterations, if after the third attempt the word is not found in the dialect word dictionaries, it is simply skipped. The pseudocode and flowchart for this algorithm are shown in Fig. 7.

Figure 7: Algorithm for morphological analysis.

Postprocessing algorithm

To improve the model results, a rule-oriented algorithm was developed, which is activated in post-processing as soon as it receives the result from the neural network. For example, let’s consider one of the examples when the models predict not exactly what was expected, or rather, a confusing choice like “viloyati hokimiyati (B-ORG E-ORG)” and “viloyati (E-LOC) hokimiyati (S-ORG)” was eliminated. Although, both of these examples are existed in training dataset (so, they are correctly predicted), there is a particular case in each situation. Sometimes, we need to show the level of governor office, while in other case we should separate these entities. To solve such problems, rules were implemented where a branch of choice priorities was specified, allowing the algorithm to mark entities in the most correct way. For correct understanding of words above, there are translations: viloyati—region, hokimiyati—governor office.

After implementing rule-based modules for transliteration, dialect normalization and morphological analysis, we evaluated several neural architectures to capture contextual dependencies. The following subsections detail the CNN–BiLSTM, mBERT and SpaCy models.

Neural networks models

It should be noted that all models were trained with our custom dataset (Mengliev, 2025b). Speaking about the used dataset, it can be noted that it contains more than 3,000 marked sentences, and the total number of words is 34,911. In the process of studying the text annotation schemes for the task of recognizing named entities, various options were investigated, including BIO, BIOS, BILOU and others. However, the authors decided to choose the BIOES annotation scheme, where it is possible to clearly define the boundaries of the beginning and end of named entities (Sang & Veenstra, 1999). Meanwhile, speaking about the sources from which the texts were taken to form the dataset, it can be noted that the original source was legal documents that are grammatically correct and have almost no typos in words. Although, other sources were also used, for example, fragments of articles from news blogs and similar services. It should be noted that according to the Uzbek copyright law (Articles 37, 41, 42), individual words and short phrases are not protected by copyright. Moreover, it should be noted that data were collected as previously described in Mengliev et al. (2025).

During the work, the data for training and evaluating the models was divided into three parts, but different proportions were used for each architecture: for mBERT—70% training set, 15% validation and 15% test; for CNN+BiLSTM—80% training and 20% test; for SpaCy—70% training and 30% validation. This decision was due to several factors.

-

(1)

Our corpus as it was mentioned above, contains over 3,000 sentences and 34,911 tokens. When working with a low-resource language, it is important to keep a sufficient volume of the training set so that the model can learn the representation of words and contexts. Therefore, allocating too much to test and validation would be suboptimal.

-

(2)

For mBERT and SpaCy, a classic triad scheme (train/validation/test) was used. This allowed us to control overfitting using validation testing and select the optimal number of epochs. For CNN+BiLSTM, we used a two-part split (train/test), since the model was trained jointly with post-processing and subsequent validation on the test, and the internal regularization effect was provided by dropout and early stopping.

-

(3)

Many studies of NER in low-resource languages use an 80/20 or 70/30 scheme, which ensures comparability of results. Our goal was not to test different splitting schemes, but to compare approaches; therefore, we kept the standard proportions characteristic of specific architectures and justified them with practical considerations.

-

(4)

Early stopping was used for all models, which avoided overfitting even in the absence of separate validation for CNN+BiLSTM. Metric values were observed during training, and the retained models were selected at those epochs where the validation metrics reached the optimum.

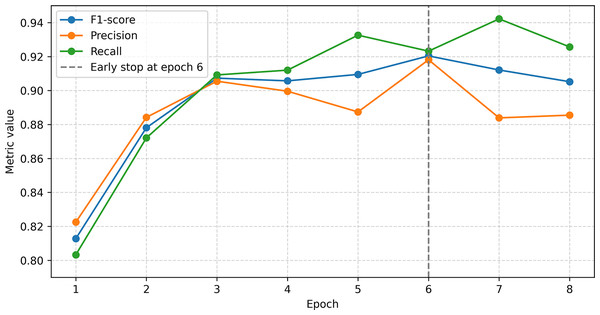

Given the above facts, the adopted data split proportions reflect a balance between the need for a sufficient training sample size and the practical limitations of each architecture. Figures 8–10 clearly show the eras to which the model weights were rolled back using dotted lines.

Figure 8: mBERT model training process.

Figure 9: CNN+BiLSTM model training process.

Figure 10: SpaCy-based model training log.

mBERT

To solve the NER problem based on mBERT, the BertForTokenClassification model was used with the number of output classes equal to the number of unique labels. The BIOES markup was transformed into numeric identifiers. For tokenization, BertTokenizerFast from the bert-base-multilingual-cased model was used. The data was split in a 70:15:15 ratio. Training was carried out with the AdamW optimizer (lr = 2e−5, L2 = 0.01), a total of eight epochs, with early stopping triggered on the 6th. The model showed high results: accuracy 96.3%, F1 = 0.9052, precision = 0.8855, recall = 0.9257, which indicates good quality of entity recognition (Fig. 8).

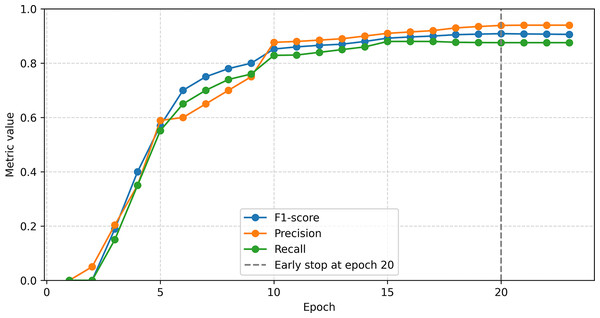

CNN+BiLSTM

The developed architecture included Embedding, Conv1D (64 filters, kernel = 3), Dropout, BiLSTM (64 neurons, recurrent dropout = 0.5) and TimeDistributed Softmax. The maximum sentence length was 50 tokens. The data was split 80:20. Training was carried out with the Adam optimizer (lr = 1e−3), 23 epochs with early stopping. The best results were achieved on the 20th epoch: F1 ≈ 0.907, precision ≈ 0.94, recall ≈ 0.876. The model effectively combined local (Conv1D) and global (BiLSTM) context, demonstrating stable results (Fig. 9).

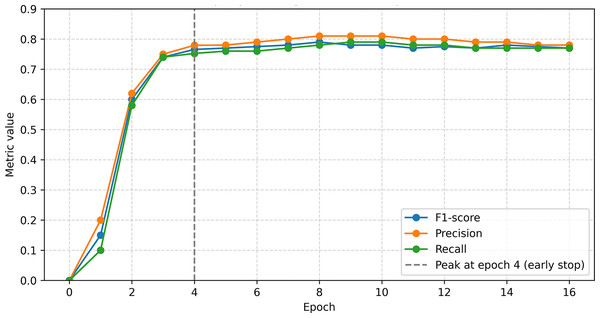

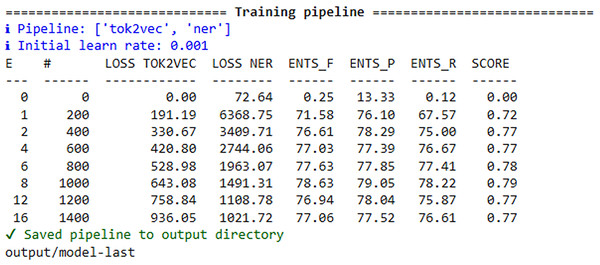

SpaCy

The SpaCy model used standard tok2vec and NER components. The data was converted to .spacy format and split 70:30. Training was conducted with the Adam optimizer (lr = 0.001) and early stopping. The best results were obtained in the 4th epoch: F1 = 76.56, precision = 77.93%, recall = 75.23. The final model (model-best) demonstrated stable quality of entity recognition on test data (Figs. 10, 11).

Figure 11: Graph of the change in spacy model metrics during training.

Results and discussion

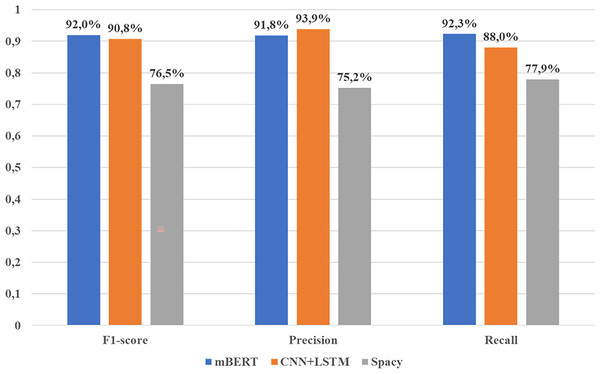

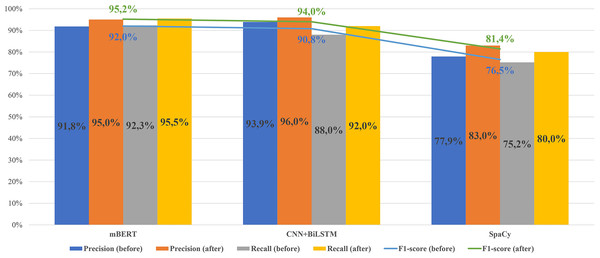

This section discusses test experiments aimed at assessing the performance of models in real world conditions. In particular, data was collected from approximately similar sources, from which the primary data was collected to form the training dataset. More detailed test results can be found in Table 2 or Fig. 12.

| Model | Precision | Recall | F1-score | Spent time for training | Inference time (per 1,000 sentences) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mBERT | 91.8% | 92.3% | 92.0% | ~25 min | ~2 min |

| CNN+BiLSTM | 93.9% | 88.0% | 90.8% | ~18 min | ~1 min |

| SpaCy | 77.9% | 75.2% | 76.5% | ~10 min | <30 s |

Figure 12: Comparison of the results of the performance of language models.

The table above shows that the BERT-based model performed best in key metrics such as recall (92.3%) and F1-score (92.0%), while the CNN+BiLSTM combination showed the highest precision, reaching 93.9%. Meanwhile, SpaCy leads in the least amount of time spent on training and inference (response time) when analyzing sentences.

Analysis of model errors

mBERT

Typical errors: Sometimes the model confused organizations (ORG) and locations (LOC), especially when the organization name contained geographical names.

Example of error:

Sentence: Xorazm viloyati hokimiyati sayyor qabulini elon qildi.

True Labels: Xorazm (S-LOC) viloyati hokimiyati (B-ORG E-ORG) sayyor (O) qabulini (O) elon (O) qildi (O).

Predicted Labels: Xorazm (B-LOC) viloyati (E-LOC) hokimiyati (S-ORG) sayyor (O) qabulini (O) elon (O) qildi (O).

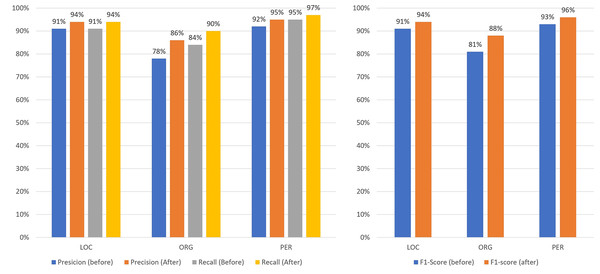

Analysis: The model identified “hokimiyati” as a one-word entity, although in fact there were two words—viloyati hokimiyati (B-ORG E-ORG), which translates as regional office of the governor. However, it should be noted that the corpus contains both variants: Xorazm (B-LOC) viloyati (E-LOC), which translates as Khorezm region, and viloyati hokimiyati (B-ORG E-ORG), which translates as regional office of the governor. The reason why this result of the analysis should be considered incorrect, or rather, not entirely correct, is that the “hokimiyat” can be regional, city or district level, and that is why the emphasis should be on the type of “hokimiyat”, and not on the location. Table 3 shows the results of testing the mBERT model in terms of entities.

| Type of entity | Precision | Recall | F1-score | Quantity of entities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOC | 91% | 91% | 91% | 955 |

| ORG | 78% | 84% | 81% | 530 |

| PER | 92% | 95% | 93% | 1,610 |

CNN+BiLSTM

Typical mistakes:

The CNN + LSTM model, like the BERT model, sometimes incorrectly classified organizations as locations and vice versa, especially when the organization name contained geographic references.

The model had difficulty detecting the boundaries of multi-word named entities, often not considering all components of the name.

Example mistake:

Sentence: “O’zbekiston Respublikasi Vazirlar Mahkamasi qaror qabul qildi.”

True labels: “O’zbekiston Respublikasi (B-LOC E-LOC) Vazirlar Mahkamasi (B-ORG E-ORG) qaror (O) qabul (O) qildi (O).”

Predicted labels: “O’zbekiston (B-LOC) Respublikasi (E-LOC) Vazirlar (S-PER) Mahkamasi (S-ORG) qaror (O) qabul (O) qildi (O).”

Analysis: The model incorrectly labeled “Vazirlar Mahkamasi” (“Cabinet of Ministers”) as two separate entities Vazirlar (S-PER) (Ministers) Mahkamasi (S-ORG) (Cabinet), rather than as a full-fledged entity-organization. Table 4 shows the results of testing the CNN(+LSTM) model across entities.

| Type of entity | Precision | Recall | F1-score | Quantity of entities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOC | 81% | 90% | 85% | 955 |

| ORG | 83% | 83% | 83% | 530 |

| PER | 91% | 88% | 90% | 1,610 |

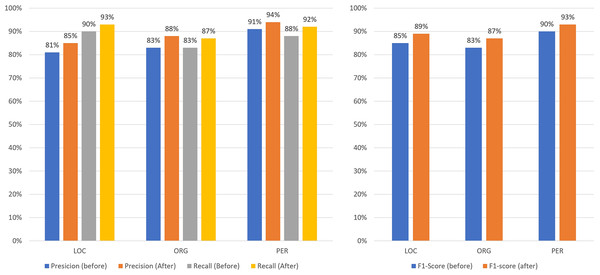

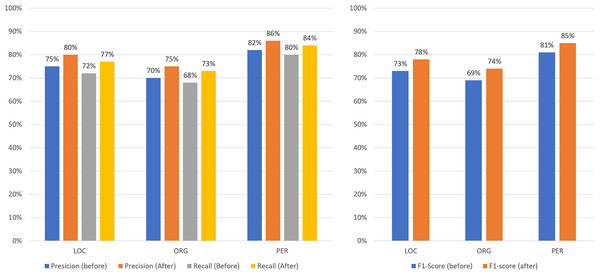

SpaCy

Typical mistakes: The SpaCy model had similar difficulties as previous models in correctly classifying ORG and LOC entities, often confusing them or not recognizing them at all.

Error example:

Sentence: “O’zbekiston Respublikasi Prezidenti yangi qaror imzoladi.”

True labels: “O’zbekiston Respublikasi (B-LOC E-LOC) Prezidenti (S-PER) yangi (O) qaror (O) imzoladi (O).”

Predicted labels: “O’zbekiston (S-LOC) Respublikasi (B-PER) Prezidenti (E-PER) yangi (O) qaror (O) imzoladi (O).”

Analysis: The model incorrectly labeled “O’zbekiston Respublikasi” (Republic of Uzbekistan) as two different entities O’zbekiston (S-LOC) (Uzbekistan) Respublikasi (B-PER)(Republic), rather than as a full location entity. In addition, the one-word entity Prezidenti (S-PER) was labeled as the second word of the person entity (E-PER). Table 5 shows the results of testing the SpaCy model across entities.

| Type of entity | Precision | Recall | F1-score | Quantity of entities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOC | 75% | 72% | 73% | 955 |

| ORG | 70% | 68% | 69% | 530 |

| PER | 82% | 80% | 81% | 1,610 |

Post-processing

To enhance text analysis results, a post-processing algorithm was implemented. After the initial output of a language model, the algorithm applies rule-based corrections to improve entity labeling accuracy. As described earlier, the rules determine the most appropriate variant of a named entity for each token.

Figures 13–16 present the updated metrics after post-processing for overall performance and by entity type across mBERT, CNN+BiLSTM, and SpaCy. For clarity and comparison, Table 6 summarizes accuracy, recall, and F1-scores. Among prior works on Uzbek (Mengliev et al., 2023a), only one applied AI-based NER, while others relied on traditional approaches, making direct comparison less meaningful.

Figure 13: Comparison of the results of the performance of models before/after post-processing.

Figure 14: Comparison of the results of the performance of mBERT before/after post-processing by entities.

Figure 15: Comparison of the results of the performance of CNN+BiLSTM before/after post-processing by entities.

Figure 16: Comparison of the results of the performance of SpaCy before/after post-processing by entities.

| Language model type | Precision | Recall | F1-score |

|---|---|---|---|

| BiLSTM+CRF | 86.8% | 79.2% | 82.8% |

| w/o Data translation | 84.6% | 80.0% | 82.2% |

| BartNER | 92.3% | 90.1% | 91.2% |

| w/o Data translation | 90.4% | 88.0% | 89.2% |

| W2NER | 92.4% | 90.2% | 91.3% |

| w/o Data translation | 92.3% | 90.0% | 91.1% |

| UIE | 91.2% | 87.1% | 89.1% |

| w/o Data translation | 87.2% | 83.4% | 85.2% |

| UZNER | 92.8% | 90.6% | 91.7% |

| w/o Data translation | 91.9% | 90.3% | 91.1% |

| Our solutions (without post-processing) | |||

| mBERT | 91.8% | 92.3% | 92.0% |

| CNN+BiLSTM | 93.9% | 88.0% | 90.8% |

| SpaCy | 77.9% | 75.2% | 76.5% |

| Our solutions (with post-processing) | |||

| mBERT | 95.0% | 95.5% | 95.2% |

| CNN+BiLSTM | 96.0% | 92.0% | 94.0% |

| SpaCy | 83.0% | 80.0% | 81.4% |

Our experiments show that without post-processing, results were comparable to existing tools. However, after applying the algorithm, performance improved markedly: F1 reached 94% for CNN+BiLSTM and 95% for mBERT.

Conclusions

In the course of the study, a comprehensive methodology for identifying named entities in Uzbek texts was developed, where a hybrid approach was actively used. The hybrid approach consisted of using neural models (mBERT, CNN+BiLSTM and SpaCy) in con-junction with rule-oriented algorithms (transliteration, normalization of dialect words, morphological analysis and post-processing).

One of the main positive aspects of the proposed hybrid approach is the efficiency of working with such practical difficulties as dialect diversity, as well as strong agglutinativity of the language. The use of transliteration and an algorithm for replacing dialect forms with formal equivalents made it possible to solve one of the existing problems, which is still quite common today. In addition, none of the scientific works on identifying named entities has yet considered such a problem, despite the number of speakers of these dialects (more than 3.5 million people). At the same time, using post-processing implemented using a set of rules, better results were achieved than if only neural networks were used.

The results of the experiments showed that the mBERT model demonstrated the best recall and F1-measure values (up to 92% without post-processing and 95.2% taking into account post-processing), while CNN+BiLSTM showed the highest accuracy (93.9% without post-processing and 96% with it). The SpaCy-based model, although it demonstrated more modest metrics (about 76.5% f1 without post-processing), stands out for the lowest time costs both for training and for real-time application.

The obtained results open up prospects for the implementation of this technique in various areas requiring the processing of Uzbek-language texts, including in the areas of e-commerce, healthcare and user comment analysis. In the future, it is planned to expand the volume of the marked corpus, refine the dictionary base for normalizing words, and test additional architectures of deep neural networks, which will make it possible to even more effectively solve problems of detecting and classifying named entities for Uzbek (and other Turkic) languages with low resource provision.