Cross-subject G-softmax deep domain generalization motor imagery classification in brain–computer interfaces

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Consolato Sergi

- Subject Areas

- Computational Biology, Artificial Intelligence, Brain-Computer Interface, Computer Vision, Data Mining and Machine Learning

- Keywords

- Deep domain generalization, G-softmax, Cross-subject, Motor imagery classification, BCI

- Copyright

- © 2026 Liu et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2026. Cross-subject G-softmax deep domain generalization motor imagery classification in brain–computer interfaces. PeerJ Computer Science 12:e3481 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3481

Abstract

Background

In cross-subject electroencephalography (EEG) motor imagery decoding tasks, significant physiological differences among individuals pose substantial challenges. Although Gaussian-based softmax Deep Domain Adaptation (DDA) methods have achieved considerable progress, they remain highly dependent on target domain data, which is inconsistent with real-world scenarios where target domain data may be inaccessible or extremely limited. Moreover, existing DDA methods primarily achieve feature alignment by minimizing distribution discrepancies between the source and target domains. However, given the pronounced physiological variability across individuals, simple distribution matching strategies often fail to effectively mitigate domain shift, thereby limiting generalization performance.

Methods

To address these challenges, this study proposes an improved Gaussian-based softmax Deep Domain Generalization (Exp-G-softmax DDG) framework, which aims to overcome the limitations of traditional DDG methods in handling inter-class differences and cross-domain distribution shifts. By introducing multi-source domain joint training and an enhanced G-softmax function, the proposed method effectively resolves the dynamic balance between intra-class distance and inter-class distance. The Exp-G-softmax DDG mechanism integrates class center information, thereby enhancing model robustness and improving its ability to learn discriminative feature representations, ultimately leading to superior classification performance.

Results

Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method achieves classification performance comparable to that of DDA on three publicly available real-world EEG datasets, providing a novel solution for cross-subject motor imagery decoding. The source code is available at: https://github.com/dawin2015/G-softmax-DDG.

Introduction

Motor imagery (MI) decoding, as a crucial research direction in non-invasive brain–computer interfaces (BCIs), has garnered significant attention in recent years with the rapid advancements in deep learning technologies. However, the field still faces the challenge of inter-subject variability, wherein electroencephalography (EEG) signals from different individuals exhibit substantial differences due to factors such as brain anatomical structures, neural electrical activity patterns, and cognitive states. This variability often limits the generalization ability of classification models in cross-subject settings. While subject-dependent decoding strategies for motor imagery tasks can achieve relatively high accuracy, often around 80% in binary-class settings (e.g., left vs. right hand), the performance tends to drop significantly in cross-subject scenarios, especially as the number of classes increases. For instance, the CSP-Net method proposed by Jiang et al. (2024) achieved 74.26% accuracy in a cross-subject setting, which was notably lower than its within-subject performance. These results highlight the persistent challenge of achieving robust generalization across individuals.

To address the issue of inter-subject variability, transfer learning (TL) techniques, particularly Deep Domain Adaptation (DDA) methods (Xu et al., 2020), have been introduced into MI decoding research. DDA improves cross-subject classification performance by minimizing feature distribution discrepancies between the source domain (SD) and the target domain (TD). Yuan et al. (2024) proposed an adversarial domain adaptation (ADA) approach, which enhanced classification accuracy to 80.67% in cross-subject MI tasks. Despite notable progress, most existing cross-subject MI decoding methods rely heavily on domain adaptation techniques that require at least partial access to target domain data. This dependency not only poses practical challenges in real-time or clinical scenarios—where target data may be unavailable—but also limits the deployment potential of such models. Furthermore, while adversarial domain adaptation (ADA) and other transfer learning approaches improve generalization, they often neglect the effect of intra-domain inconsistencies and struggle to preserve class-discriminative features when minimizing inter-domain discrepancies.

To overcome these limitations, Deep Domain Generalization (DDG) methods have emerged as a promising alternative. Unlike DDA, DDG does not require any access to target domain data during training. Instead, it leverages joint training across multiple source domains to learn feature representations with strong generalization capabilities (Zhou et al., 2023). This approach enables direct application to target domain data during the testing phase without the need for pre-sampling or data annotation, significantly simplifying practical implementation. Wang & Faruque (2024) introduced a DDG framework based on transformer-driven contrastive meta-learning, achieving a classification accuracy of 94.57% in cross-subject action recognition tasks—substantially outperforming traditional methods. The distinctive advantage of DDG makes it particularly well-suited for medical applications, as it eliminates the necessity for prior data collection from subjects, thereby reducing workload and enhancing the practicality of the algorithm in real-world healthcare settings.

Motivation of Gaussian-based softmax Deep Domain Generalization (Exp-G-softmax DDG). Traditional softmax classifiers compute probabilities based only on point estimates, often struggling to establish robust decision boundaries in the presence of inter-subject variability. Inspired by Luo et al. (2020), we propose incorporating Gaussian-distributional assumptions into the classification layer. Our approach integrates a modified G-softmax loss function with a domain-generalizable training architecture, thereby filling a critical methodological gap in current electroencephalography motor imagery (EEG MI) decoding: achieving high generalization performance without access to any target domain data. The proposed method not only matches the performance of DDA-based methods across three publicly available MI datasets but also significantly reduces reliance on pre-deployment calibration or annotation, making it better suited for real-world clinical applications.

The proposed G-softmax DDG framework combines two key components: a domain generalization training pipeline based on multi-source learning, and a customized G-softmax loss function that enhances class separation in the shared feature space. During training, the model leverages multiple labeled source domains and aligns feature representations through contrastive learning and regularization across domains, without any exposure to target domain data. Unlike traditional softmax, our G-softmax introduces a Gaussian-shaped margin function, which adaptively adjusts the decision boundary to ensure better separation between closely related motor imagery classes. This design improves robustness against both class overlap and subject variability. Empirical results demonstrate that this approach achieves cross-subject performance on par with or exceeding existing domain adaptation methods, while requiring no target-specific calibration. This framework is designed to tackle two key challenges: (1) eliminating the dependency on target data during training, and (2) improving class-wise discriminability in high-variability EEG data. To our knowledge, this is the first work to integrate a generalized margin-based softmax into a fully domain-generalizable EEG decoding framework.

Related study

This section presents a comprehensive review of recent developments in cross-subject EEG classification, with a focus on both DDA and DDG strategies. These two paradigms are essential for addressing the challenge of inter-subject variability in EEG-based brain–computer interfaces (BCIs), particularly in motor imagery (MI) tasks, but their implications also extend to a broader range of EEG applications.

DDA techniques have been widely adopted in MI classification due to their ability to align the feature distributions between the source and target domains, thereby improving generalization across subjects. A representative work by Li, Wang & Liu (2025) introduced an adversarial domain adaptation (ADA) framework that integrates a domain classifier and a gradient reversal layer (GRL) to facilitate feature alignment, yielding significant performance gains in cross-subject settings. However, despite their effectiveness, DDA approaches are still constrained by the requirement for at least a portion of target domain data during training. This dependency on annotated or unannotated target samples limits their practical applicability, particularly in real-world clinical or real-time BCI systems where such data may not be available in advance. Moreover, DDA methods are vulnerable to negative transfer when there is a substantial discrepancy between domains, and they typically entail increased computational cost due to the additional complexity of alignment mechanisms.

To overcome these limitations, DDG methods have emerged as a promising alternative, as they completely eliminate the need for target domain data during training. In fact, DDG frameworks leverage multi-source domain training to extract generalizable and robust feature representations that can be directly applied to unseen target subjects. This capability offers a considerable advantage in real-world settings, especially where data collection and individual calibration are impractical. In recent years, DDG has demonstrated its potential not only in motor imagery decoding but also across various EEG applications. For instance, Zhong et al. (2024) proposed a multi-source DDG framework that utilizes domains with different statistical distributions to learn transferable features, achieving cross-subject accuracies of 81.79% and 87.12% on MI datasets. Similarly, Ballas & Diou (2024) introduced a hierarchical DDG approach based on multi-level representations to further enhance generalization performance.

Beyond the motor imagery paradigm, DDG has also been successfully applied in affective computing, cognitive workload detection, and sleep stage classification. Zhi et al. (2025) demonstrated the effectiveness of contrastive learning-based DDG in cross-subject mental workload recognition, showing that the approach maintained stable performance even when subjects were exposed to varying task conditions. In another study, Mostafaei, Tanha & Sharafkhaneh (2024) implemented a transformer-based DDG framework for sleep stage classification, highlighting its robustness in cross-participant sleep EEG analysis. These examples collectively indicate that DDG methods have become a widely applicable solution for various EEG decoding tasks in which subject variability poses a major obstacle.

Motivated by these advancements and the need for a more discriminative feature representation within DDG frameworks, we propose a novel approach that integrates an improved G-softmax loss function into a multi-source DDG architecture. This method, referred to as the G-softmax DDG framework, builds upon the margin-based G-softmax design (Luo et al., 2020) by incorporating class center information to enhance inter-class separability during the training process. The combined effect of domain generalization and enhanced class discrimination allows our model to better capture subtle differences in EEG patterns across subjects, especially in multi-class MI tasks where class imbalance and overlap are common. Unlike conventional approaches, our framework achieves strong cross-subject classification performance without requiring any access to target domain data during training or testing, thereby offering high scalability and practicality for real-world BCI deployment.

Materials and methods

The experimental design of this study is presented in three parts: the description of datasets and data repositories, the formal definition of domain generalization problem in the classification of MI in EEG, and the proposed G-softmax Deep Domain Generalization (Exp-G-softmax DDG) framework.

Datasets and repositories

This study utilizes datasets accessed through the MOABB (Mother of All BCI Benchmarks) repository (Aristimunha et al., 2023), which provides a standardized benchmark of algorithms along with a collection of publicly available BCI datasets, and the Braindecode toolbox (Schirrmeister et al., 2017), a deep learning library for EEG decoding that facilitates data handling and model implementation. In this work, three representative motor imagery datasets are employed: Lee2019_MI, BNCI2014001, and BNCI2014004.

These datasets differ in key aspects such as the number of subjects, EEG channel configurations, number of MI classes, and sampling frequencies. Specifically, Lee2019_MI is a large-scale dataset containing 54 subjects with 62-channel EEG recordings sampled at 1,000 Hz, focusing on binary-class (left- vs. right-hand) MI tasks. BNCI2014001 contains 4-class imagery (left hand, right hand, feet, tongue) data from nine subjects with 22 EEG channels recorded at 250 Hz. BNCI2014004 represents a minimal-channel setup with only three electrodes, also focused on binary-class MI, collected over multiple sessions.

The datasets are designed with balanced class distributions: Lee2019_MI includes approximately equal numbers of left- and right-hand trials (about 5,500 per class), BNCI2014001 ensures uniform distribution across its four classes (approximately 15,552 trials per class), and BNCI2014004 provides an equal number of trials for its two classes (16,200 each) distributed across five sessions. These variations in electrode density, class complexity, and recording protocols allow for a comprehensive evaluation of model generalization. Table 1 summarizes the main characteristics of the datasets.

| Dataset | #Subj | #Chan | #Classes | #Trials | Trial length | Freq | #Session | #Runs | Total_trials |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lee2019_MI (Lee et al., 2019) | 54 | 62 | 2 | 100 | 4s | 1,000 Hz | 2 | 1 | 11,000 |

| BNCI2014001 (Tangermann et al., 2012) | 9 | 22 | 4 | 144 | 4s | 250 Hz | 2 | 6 | 62,208 |

| BNCI2014004 (Leeb et al., 2007) | 9 | 3 | 2 | 360 | 4.5s | 250 Hz | 5 | 1 | 32,400 |

Framework overview

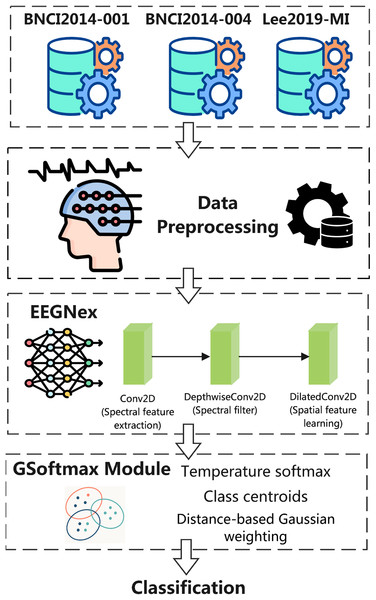

The overall architecture of the proposed Exp-G-softmax DDG framework for MI classification using EEG signals. The framework begins with three benchmark datasets, BNCI2014-001, BNCI2014-004, and Lee2019-MI, which provide multichannel EEG recordings of MI tasks. Following standard preprocessing, EEG signals are segmented into trials and normalized to ensure consistency between subjects and sessions.

The preprocessed trials are then processed by the EEGNeX backbone, a convolutional neural network adapted for EEG decoding. EEGNeX consists of a sequence of convolutional modules: a conventional Conv2D layer for spectral feature extraction, a DepthwiseConv2D layer that acts as a frequency-selective filter, and a DilatedConv2D layer designed to capture long-range spatial dependencies across electrodes. Together, these modules yield a rich spatio-temporal representation of EEG dynamics.

Subsequently, the learned features are fed into the Exp-G-softmax module, which extends the conventional softmax classifier by integrating temperature scaling with Gaussian-based class centroid modeling. This mechanism enhances intra-class compactness and enforces greater separation between classes, thereby mitigating the adverse effects of inter-subject variability.

Finally, the model produces the classification output, assigning each trial to its corresponding MI category (e.g., left hand, right hand, feet, or tongue). By combining EEGNeX’s efficient feature learning with the G-softmax classifier, the proposed framework achieves robust cross-subject generalization while eliminating the need for target domain calibration. The framework as shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Exp-G-softmax DDG framework.

Formal definition

Let the EEG data be noted as , and MI classes as . The goal is to train a classification model . There exist SDs, denoted as , where each SD corresponds to a different subject. Specifically, each source domain is defined as: where represents the EEG data samples from subject , denotes the corresponding MI class labels, and is the number of samples for subject . The TD consists of EEG data and labels, forming the dataset: . The key distinction between DDG and DDA lies in the fact that target domain data remains completely unseen during training, meaning the model cannot be directly optimized on .

To optimize the deep learning model , the empirical risk on the source domains (SDs) is minimized as follows:

where:

represents the classification loss function;

denotes the model parameters.

Since the TD remains unseen, the key objective for generalization is:

That is, ensuring a low classification error on the unseen TD.

Table 2 Algorithm 1 provides the detailed training pipeline for the proposed Exp-G-softmax DDG framework. The procedure starts with initializing the EEGNeX backbone and the Exp-G-softmax classifier, followed by the definition of the cross-entropy loss and the Adam optimizer. During each training epoch, the EEG batches are passed through the feature extractor to compute logits, which are then normalized via the G-softmax module.

| Input: A set of training samples from a MI database. |

|

|

Output: Target domain labels yi Procedures: Initialize the EEGNeX model with randomly initialized parameters . Define G-softmax module G(Temperature = , alpha = ). Set cross-entropy loss function . Initialize Adam optimizer with learning rate . For epoch = 1 to do: Set total_loss = 0 Set model to training mode For each batch in train_loader do: Compute model output logits: Compute traditional Softmax: Compute class-wise mean logits: Compute Euclidean distance from samples to class centers: Compute Gaussian regularization term: Compute GSoftmax probabilities: Compute loss function: |

The G-softmax function is defined as follows:

where:

represents the feature value of the i class.

denote the mean and standard deviation of the feature distribution for class , respectively.

represents the Gaussian cumulative distribution function (CDF).

is a hyperparameter that controls the influence of the CDF.

When , G-softmax reduces to the standard softmax function.

The Gaussian CDF is defined as:

During the training process, G-softmax requires updating the parameters and . Consequently, the computational cost per iteration is extremely high, leading to a significantly slow convergence speed, making it unsuitable for large-scale tasks. To reduce the computational burden of G-softmax and better adapt it to EEG MI classification tasks, this study replaces the Gaussian CDF weighting with an exponentially decaying function, where the Euclidean distance from the class center is used as a measure:

Thus, the improved G-softmax function is defined as:

where: represents the initial probability computed using standard softmax.

Intuitive explanation of the improvement. Conceptually, this modification improves both computational efficiency and classification stability. The original G-softmax relies on the Gaussian CDF to capture the cumulative probability distribution of features around each class mean. Although theoretically precise, this approach requires repeatedly estimating the full probability density function for every class, which is computationally expensive and sensitive to non-Gaussian feature distributions often observed in EEG data.

In contrast, the proposed exponentially decaying function acts as a local distance-sensitive weighting mechanism. Instead of integrating over the entire Gaussian distribution, it directly penalizes samples that lie farther from the class centroid, thereby enforcing tighter intra-class clustering in the latent space. This exponential decay dynamically adjusts the class boundary according to the spatial distance of features, allowing the model to emphasize central (prototypical) samples and downweight peripheral (ambiguous) ones.

From an intuitive standpoint, this mechanism can be viewed as introducing a smooth margin constraint that separates classes more clearly without complex normalization. It simplifies the optimization landscape by eliminating the need to compute higher-order statistical moments, resulting in faster convergence and more robust generalization across subjects. In essence, the improved G-softmax not only retains the probabilistic interpretability of the original formulation but also achieves better feature compactness and boundary adaptability, which are particularly advantageous for EEG signals characterized by high inter-subject variability and low signal-to-noise ratio.

EEGNeX overview

In this study, we adopt EEGNeX as the core feature extractor. EEGNeX (Chen et al., 2024) is a novel convolutional neural network architecture specifically designed for EEG signal classification tasks in Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) applications. Building upon the foundational principles of the classical EEGNet, EEGNeX incorporates several key innovations aimed at significantly enhancing the spatiotemporal feature representation capabilities of EEG data.

More specifically, EEGNeX leverages depthwise convolution and dilated convolution techniques to efficiently and effectively extract spatial and temporal features from multichannel EEG signals, which is crucial for accurate decoding of brain activity. The architecture is designed to reduce the number of trainable parameters without compromising performance, making it particularly suitable for EEG datasets, which are typically much smaller in size compared to image datasets. This efficiency contributes to improved computational performance.

By integrating inverted bottleneck structures and dilation mechanisms, EEGNeX further enhances its generalization ability across diverse EEG datasets and has outperformed state-of-the-art models such as EEGNet and EEG-TCNet on several benchmark evaluations. Within the framework of this study, EEGNeX is responsible for providing high-quality and discriminative EEG features, which are directly fed into our proposed G-softmax DDG classification module.

Results

Experimental design

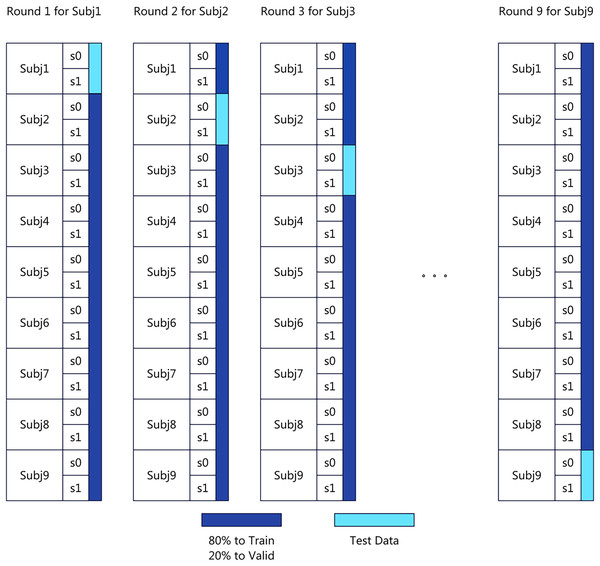

The experiments are performed on a computing system equipped with an 8-core Xeon (Skylake, IBRS) CPU with 32 GB RAM and an NVIDIA V100 GPU. We adopt the CrossSubjectEvaluation approach from MOABB for benchmarking. Specifically, we follow a subject-independent leave-one-subject-out (LOSO) validation strategy, which ensures that the model is always evaluated on entirely unseen subjects. Due to time and resource constraints, we select the greatest common subset across the three datasets, consisting of nine subjects for testing. Following the CrossSubjectEvaluation methodology, within the same dataset, one subject is designated as the test set, while the remaining eight subjects serve as the training set. This subject-independent LOSO protocol provides a rigorous assessment of generalization ability across individuals. The dataset distribution is illustrated in Fig. 2. To ensure a fair comparison of transfer learning performance, the model hyperparameters remain consistent between the baseline and transfer learning settings, as detailed in Table 3. All hyperparameters were determined through empirical tuning within a constrained search space informed by prior EEG decoding studies (e.g., Schirrmeister et al., 2017; Lawhern et al., 2018). Specifically, the learning rate, batch size, and weight decay were optimized using a small-scale grid search on a validation subset of the training data, while other parameters such as optimizer type and activation functions were fixed according to their established stability in EEGNeX-based architectures. The final configuration was selected to balance training stability, convergence speed, and generalization performance, rather than to maximize performance on any single dataset, ensuring methodological consistency across experiments.

Figure 2: Cross subject evaluation benchmark data distribution.

| Hyperparameters | Value |

|---|---|

| learning_rate | 0.0001 |

| n_epoch | 1,000 |

| early_stop | 300 |

| Temperature | 1.0 |

| Alpha | 2 |

To establish a comparative baseline, we conducted a series of benchmark evaluations using the MOABB (Mother of All BCI Benchmarks) framework (Aristimunha et al., 2023), specifically employing its built-in CrossSubjectEvaluation protocol. In all cases, the subject-independent LOSO validation was applied, such that one subject was held out for testing while the remaining subjects were used for training. This benchmark is designed to assess the generalization capability of classification models across different subjects within the same dataset, without relying on domain adaptation or generalization techniques.

In this evaluation, four well-known neural network architectures, Deep4Net (Schirrmeister et al., 2017), EEGInception (Santamaría-Vázquez et al., 2020), EEGNetv4 (Lawhern et al., 2018), and ShallowFBCSPNet (Schirrmeister et al., 2017), were tested on three public MI-EEG datasets (BNCI2014-001, BNCI2014-004, and Lee2019-MI), using the default MOABB pipelines. For comparison, we also included TIDNet (Kostas & Rudzicz, 2020), a temporal interaction-based model, under the same settings. Importantly, none of these models employed domain generalization (DDG) strategies during training, allowing us to assess their raw cross-subject performance.

The results, summarized in Table 4, serve as a non-DDG reference point for evaluating the effectiveness of our proposed G-softmax DDG method in subsequent sections. These baselines demonstrate the inherent limitations of direct cross-subject learning and underscore the necessity of incorporating domain generalization mechanisms. Although basic preprocessing methods such as standardization and normalization can improve data comparability, they are insufficient to address the inherent physiological variability and complex domain shifts present in cross-subject EEG signals. Therefore, this study proposes the Exp-G-softmax DDG framework, which addresses this deeper challenge by improving the discriminative capability of the classification layer.

| ID | Subject | n_chans | Dataset | Pipeline | Avg acc. score ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 9 | 22 | BNCI2014-001 | Deep4Net | 82.82 ± 1.36 |

| 1 | 9 | 3 | BNCI2014-004 | Deep4Net | 78.99 ± 1.40 |

| 2 | 9 | 62 | Lee2019-MI | Deep4Net | 78.15 ± 1.68 |

| 3 | 9 | 22 | BNCI2014-001 | EEGInception | 75.64 ± 1.32 |

| 4 | 9 | 3 | BNCI2014-004 | EEGInception | 81.72 ± 1.40 |

| 5 | 9 | 62 | Lee2019-MI | EEGInception | 77.64 ± 1.64 |

| 6 | 9 | 22 | BNCI2014-001 | EEGNetv4 | 81.74 ± 1.32 |

| 7 | 9 | 3 | BNCI2014-004 | EEGNetv4 | 81.98 ± 1.28 |

| 8 | 9 | 62 | Lee2019-MI | EEGNetv4 | 78.41 ± 1.21 |

| 9 | 9 | 22 | BNCI2014-001 | ShallowFBCSPNet | 79.84 ± 1.14 |

| 10 | 9 | 3 | BNCI2014-004 | ShallowFBCSPNet | 79.62 ± 1.94 |

| 11 | 9 | 62 | Lee2019-MI | ShallowFBCSPNet | 77.77 ± 1.90 |

| 12 | 9 | 22 | BNCI2014-001 | TIDNet | 62.04 ± 3.50 |

| 13 | 9 | 3 | BNCI2014-004 | TIDNet | 81.40 ± 1.36 |

| 14 | 9 | 62 | Lee2019-MI | TIDNet | 66.82 ± 2.48 |

As shown in Table 4, even the most advanced baseline networks (e.g., Deep4Net, EEGNetv4 and TIDNet) exhibit considerable performance degradation when evaluated in subject-independent settings, confirming that existing models struggle to maintain discriminative power between individuals. This empirical evidence directly motivates the development of our proposed Exp-G-softmax DDG framework, which aims to bridge this gap by strengthening the class-level discriminability of latent representations while preserving generalization across unseen subjects.

To this end, one subject is selected as the target data, and its labels are removed during the transfer process. The remaining eight subjects serve as multi-source training data. It is important to emphasize that, unlike DDA, where a portion of unlabeled target data is incorporated during training, in DDG, the target data is entirely excluded from the training process, as detailed in Algorithm 1.

Specifically, the training process utilizes the Exp-G-softmax DDG method, which extends the traditional softmax operation by integrating Gaussian regularization based on the Euclidean distance between sample logits and class-wise mean logits. During each training iteration, the EEGNeX model is optimized via cross-entropy loss computed on the Exp-G-softmax probabilities, which are obtained by modulating the softmax outputs with a Gaussian weighting term. This mechanism enhances intra-class compactness and inter-class separability without relying on any target domain information. The dataset distribution follows the same structure as illustrated in Fig. 2.

Experimental results

To evaluate the effectiveness of Exp-G-softmax DDG, we compare it with the following DDA methods: DRDA (Zhao et al., 2021): Proposes a DDA approach that integrates center loss and adversarial learning to extract source domain features and map them into a deep representation space. DJDAN (Hong et al., 2021): Introduces dynamic joint domain adaptation learning using adversarial learning to extract domain-invariant features. DAFS (Phunruangsakao, Achanccaray & Hayashibe, 2022): Employs few-shot learning in DDA to enhance classification performance for target subjects. DADW (She et al., 2023): Utilizes Wasserstein distance-based domain adaptation to extract features from the source domain and improve classification performance in the target domain. GAT (Song et al., 2023): Proposes a global adaptive Transformer based on domain adaptation to learn spatially and temporally invariant features from the source domain, improving classification performance in the target domain.

As shown in Tables 5, 6 and 7, the proposed Exp-G-softmax DDG framework achieves more stable and consistent cross-subject MI classification performance in the three datasets: BNCI2014-001, BNCI2014-004, and Lee2019-MI. Although some baseline models perform well for certain subjects, their results often display high variability, reflecting limited generalization between individuals. In contrast, Exp-G-softmax DDG demonstrates reduced performance fluctuation and maintains competitive or superior accuracy in most cases, indicating that it generalizes more effectively across diverse subjects. Specifically, G-softmax DDG achieves consistent improvements on BNCI2014-001, a dataset with high classification difficulty. On BNCI2014-004, which has moderate separability, it further enhances accuracy while maintaining low variance. Notably, on the Lee2019-MI dataset, Exp-G-softmax DDG achieves the highest average accuracy (66.42 ± 10.00%) among all compared methods, surpassing DDA-based approaches such as DJDAN, DAFS, DAWD, and GAT. This indicates that Exp-G-softmax DDG can attain cross-subject classification performance comparable to or exceeding state-of-the-art DDA models without incorporating any target-domain data. However, the relatively high standard deviation suggests subject-specific variability remains a key challenge, highlighting the need for future research on improving model stability and generalization.

| Method | Subject | MEAN ± STD | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A01 | A02 | A03 | A04 | A05 | A06 | A07 | A08 | A09 | ||

| DRDA (Zhao et al., 2021) | 83.19 | 55.14 | 87.43 | 75.28 | 62.29 | 57.15 | 86.18 | 83.61 | 82.00 | 74.75 ± 12.96 |

| DJDAN (Hong et al., 2021) | 85.77 | 63.25 | 93.41 | 76.75 | 62.68 | 69.77 | 87.37 | 86.72 | 85.61 | 79.03 ± 11.35 |

| DAFS (Phunruangsakao, Achanccaray & Hayashibe, 2022) | 81.94 | 64.58 | 88.89 | 73.61 | 70.49 | 56.6 | 85.42 | 79.51 | 81.60 | 75.85 ± 10.47 |

| DAWD (She et al., 2023) | 83.29 | 63.97 | 90.30 | 76.94 | 69.34 | 60.08 | 89.31 | 82.35 | 82.81 | 77.60 ± 10.85 |

| GAT (Song et al., 2023) | 88.89 | 61.11 | 93.40 | 71.86 | 50.35 | 60.07 | 89.58 | 87.50 | 86.46 | 76.58 ± 15.98 |

| G-softmax DDG (Ours) | 76.39 | 66.15 | 63.89 | 66.84 | 82.81 | 63.89 | 87.33 | 87.85 | 80.21 | 75.04 ± 9.99 |

| Method | Subject | MEAN ± STD | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B01 | B02 | B03 | B04 | B05 | B06 | B07 | B08 | B09 | ||

| DRDA (Zhao et al., 2021) | 81.37 | 62.86 | 63.63 | 95.94 | 93.56 | 88.19 | 85.00 | 95.25 | 90.00 | 83.98 ± 12.67 |

| DJDAN (Hong et al., 2021) | 75.88 | 58.57 | 73.04 | 96.70 | 98.90 | 87.65 | 85.78 | 84.35 | 85.31 | 84.66 ± 12.37 |

| DAFS (Phunruangsakao, Achanccaray & Hayashibe, 2022) | 70.31 | 73.57 | 80.31 | 94.69 | 95.00 | 83.75 | 93.73 | 95.00 | 75.31 | 84.63 ± 10.20 |

| DAWD (She et al., 2023) | 84.66 | 66.57 | 68.04 | 96.78 | 94.32 | 82.61 | 88.47 | 93.96 | 90.10 | 85.06 ± 11.05 |

| GAT (Song et al., 2023) | 84.58 | 61.67 | 60.83 | 99.58 | 87.50 | 93.33 | 85.42 | 95.00 | 92.08 | 84.44 ± 13.98 |

| G-softmax DDG (Ours) | 85.69 | 76.76 | 81.94 | 65.41 | 91.89 | 83.89 | 95.69 | 89.74 | 81.53 | 83.62 ± 8.96 |

| Method | Subject | MEAN ± STD | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C01 | C02 | C03 | C04 | C05 | C06 | C07 | C08 | C09 | ||

| DRDA (Zhao et al., 2021) | 53.70 | 55.40 | 51.52 | 51.58 | 55.30 | 54.90 | 57.51 | 51.55 | 52.56 | 53.78 ± 2.14 |

| DJDAN (Hong et al., 2021) | 54.51 | 56.63 | 56.50 | 59.80 | 52.90 | 62.10 | 57.70 | 54.20 | 59.54 | 57.10 ± 3.00 |

| DAFS (Phunruangsakao, Achanccaray & Hayashibe, 2022) | 54.35 | 53.47 | 60.70 | 57.19 | 58.11 | 54.23 | 53.46 | 56.98 | 56.00 | 56.05 ± 2.44 |

| DAWD (She et al., 2023) | 72.40 | 62.50 | 76.57 | 65.51 | 74.52 | 62.55 | 58.60 | 52.59 | 62.80 | 65.34 ± 7.83 |

| GAT (Song et al., 2023) | 66.20 | 52.54 | 72.58 | 54.56 | 63.70 | 62.50 | 58.90 | 64.10 | 74.30 | 63.26 ± 7.32 |

| G-softmax DDG (Ours) | 73.66 | 64.29 | 70.98 | 60.27 | 80.36 | 58.93 | 50.00 | 61.16 | 78.12 | 66.42 ± 10.00 |

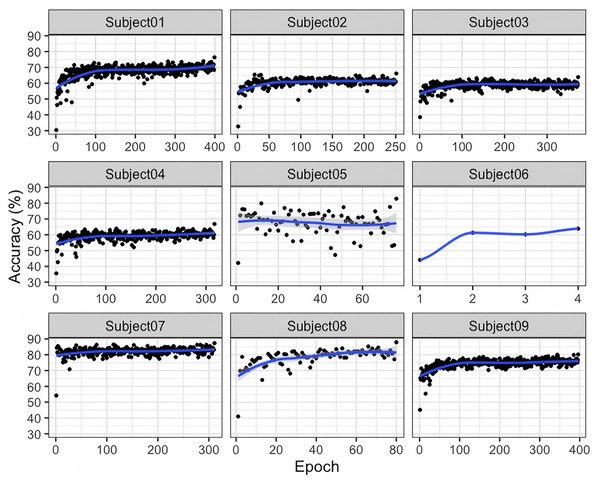

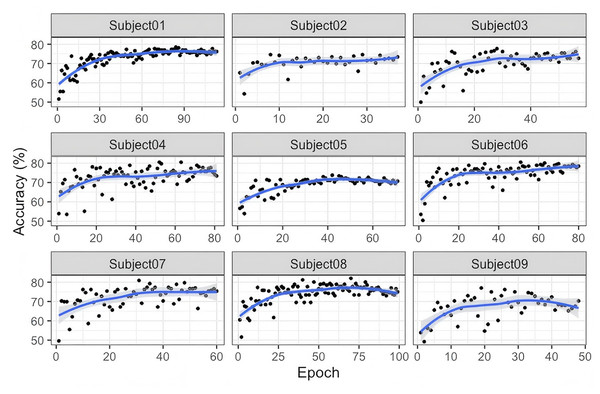

As illustrated in Fig. 3, significant inter-subject variability is observed during the training process on the BNCI2014-001 dataset. For most subjects, classification accuracy steadily increases with the number of training epochs, indicating that as the model progressively learns more stable and discriminative features, its classification performance improves accordingly. For some subjects, the accuracy curve exhibits relatively large fluctuations in the early stages of training but gradually stabilizes in the later stages. This suggests that the model initially struggles to effectively learn feature representations and classification boundaries; however, as training progresses, it gradually adapts to the EEG feature distributions of different subjects. Subjects 01, 03, 07, and 09: Their accuracy generally starts at around 60–70% and gradually but consistently increases, eventually stabilizing above 70–80%. The relatively smooth learning curves indicate that for these subjects, the model’s training process is more stable, without excessive oscillations. Overall, Fig. 3 demonstrates that the G-softmax DDG method, built upon multi-source domain joint training, achieves a dynamic balance between intra-class compactness and inter-class separability through its improved G-softmax strategy. The overall upward trend in the accuracy curves suggests that this approach effectively enables the model to learn more discriminative and robust features across different subjects.

Figure 3: Accuracy of the training and testing process for nine subjects in BNCI2014_001.

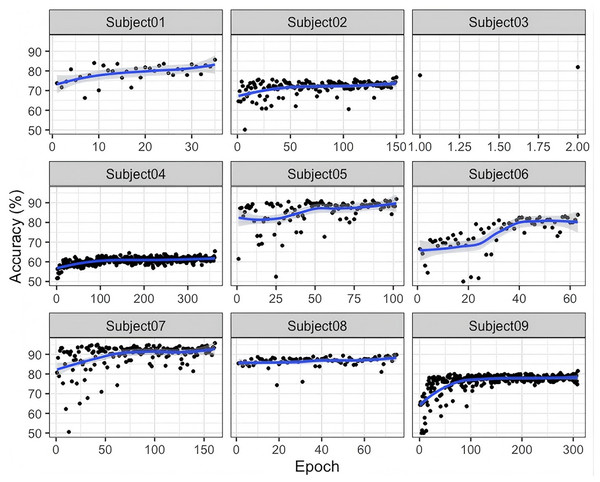

As shown in Fig. 4, compared to the BNCI2014-001 dataset, the accuracy curves for BNCI2014-004 are generally concentrated within a higher range (e.g., 70–90%). This suggests that EEG signals in BNCI2014-004 may be easier for the model to learn in cross-subject MI classification, possibly due to higher signal quality or an experimental paradigm that better differentiates MI classes. For most subjects, the accuracy curves steadily increase with the number of training epochs and gradually stabilize in the later stages. This indicates that the model exhibits a good convergence trend in extracting discriminative features. Furthermore, the results suggest that the proposed G-softmax DDG method effectively mitigates cross-subject distribution shifts to some extent.

Figure 4: Accuracy of the training and testing process for nine subjects in BNCI2014_00 4.

Finally, as illustrated in Fig. 5, the training and testing curves for the nine subjects in the Lee2019-MI dataset exhibit a gradual and stable improvement rather than an abrupt surge or early plateau. The accuracy increases steadily over epochs and converges between approximately 70% and 80%, with minor oscillations reflecting individual variability in EEG signal quality and feature separability. This behavior suggests that the G-softmax DDG model progressively refines its discriminative representations across epochs, showing no signs of overfitting or premature saturation. The smooth convergence patterns across subjects indicate that the proposed model achieves stable optimization while adapting to the heterogeneous nature of cross-subject EEG data.

Figure 5: Accuracy of the training and testing process for nine subjects in Lee2019-MI.

In summary, the observed cross-subject learning curves confirm the model’s ability to generalize effectively without relying on target-domain information, while also revealing the inherent variability among subjects as a persistent challenge for domain-generalization-based EEG classification.

Ablation experiments

To rigorously examine the contribution of each component in the proposed Exp-G-softmax module, a fine-grained ablation analysis was performed in three benchmark data sets. Two configurations were compared:

G-softmax (Gaussian-CDF): the original variant using Gaussian cumulative distribution weighting;

Exp-G-softmax (Proposed): the modified version replacing the Gaussian CDF with an exponentially decaying distance weighting to enhance computational efficiency while retaining distance awareness.

This design isolates the individual effect of the exponential substitution and allows for statistical verification of its significance.

As summarized in Tables 8, 9 and 10, the proposed Exp-G-softmax consistently outperformed or matched the original G-softmax in all datasets, with statistically significant improvements (p < 0.05) in each case.

| Conditions | A01 | A02 | A03 | A04 | A05 | A06 | A07 | A08 | A09 | Average | Std | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G-softmax (Gaussian-CDF) | 71.94 | 55.21 | 64.03 | 59.38 | 54.17 | 68.75 | 59.03 | 76.21 | 61.44 | 63.35 | 7.56 | p < 0.05 |

| Exp-G-softmax (Proposed) | 76.39 | 66.15 | 63.89 | 66.84 | 82.81 | 63.89 | 87.33 | 87.85 | 80.21 | 75.04 | 9.99 | – |

| Conditions | B01 | B02 | B03 | B04 | B05 | B06 | B07 | B08 | B09 | Average | Std | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G-softmax (Gaussian-CDF) | 67.26 | 56.25 | 54.62 | 80.62 | 73.31 | 81.25 | 70.11 | 78.12 | 79.62 | 71.24 | 10.17 | p < 0.05 |

| Exp-G-softmax (Proposed) | 85.69 | 76.76 | 81.94 | 65.41 | 91.89 | 83.89 | 95.69 | 89.74 | 81.53 | 83.62 | 8.96 | – |

| Conditions | C01 | C02 | C03 | C04 | C05 | C06 | C07 | C08 | C09 | Average | Std | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G-softmax (Gaussian-CDF) | 57.10 | 58.00 | 66.10 | 50.10 | 64.20 | 50.50 | 60.40 | 60.80 | 60.60 | 58.64 | 5.48 | p < 0.05 |

| Exp-G-softmax (Proposed) | 73.66 | 64.29 | 70.98 | 60.27 | 80.36 | 58.93 | 50.00 | 61.16 | 78.12 | 66.42 | 10.00 | – |

BNCI2014-001. Exp-G-softmax achieved an average accuracy of 75.04 ± 9.99%, surpassing the Gaussian-CDF variant (63.35 ± 7.56%, p < 0.05). This substantial margin (≈+11.7%) indicates that exponential weighting better preserves discriminative structure and alleviates cross-subject variability.

BNCI2014-004. The proposed method reached 83.62 ± 8.96%, higher than the Gaussian-CDF baseline (71.24 ± 10.17%, p < 0.05). The improvement (+12.38%) demonstrates stronger generalization under moderate inter-subject separability.

Lee2019-MI. Exp-G-softmax achieved 66.42 ± 10.00%, outperforming the Gaussian-CDF model (58.64 ± 5.48%, p < 0.05). Although variance remained high, this enhancement confirms that the proposed exponential formulation maintains robustness in a large-scale heterogeneous data set.

Overall, these results verify that exponential substitution not only reduces computational complexity, but also provides a statistically significant performance gain. The consistent superiority of Exp-G-softmax in three datasets highlights its ability to enhance domain generalization in EEG-based motor imagery classification.

Discussion

The proposed Exp-G-softmax DDG method demonstrates significant performance improvements in multi-source domain cross-subject motor imagery (MI) classification tasks, achieving competitive or even superior results compared to existing advanced domain generalization and adaptation (DDA) methods, without relying on target domain data. As shown in Tables 5, 6 and 7, Exp-G-softmax DDG consistently achieves strong performance across three EEG datasets with varying characteristics, particularly on more challenging datasets such as BNCI2014-001, where it delivers sustained performance gains.

This superior performance can be primarily attributed to the improved classification strategy introduced by Exp-G-softmax DDG, which effectively addresses the limitations of the traditional softmax function in cross-subject classification scenarios. By incorporating dynamic Gaussian modeling and explicitly optimizing intra-class compactness and inter-class separability, Exp-G-softmax DDG enables the learning of more refined and robust feature distribution representations for each class. Unlike the conventional softmax approach, which merely learns linear classification boundaries, Exp-G-softmax DDG constructs more complex and discriminative decision boundaries in the feature space. This capability is particularly crucial for handling the high dimensionality, nonlinearity, and pronounced individual variability inherent in EEG signals.

Limitation and future research

As shown in Fig. 3, the accuracy of Subject 05 exhibits significant fluctuations, which may indicate the presence of more complex interference or greater inter-class variability in this subject’s EEG signals. This suggests a need for further improvements incorporating signal quality assessment, noise suppression, or personalized feature extraction methods. Additionally, attention should be given to the instability caused by extreme cases or high-noise subjects. Future research could explore feature reweighting or domain adaptation strategies to better handle subjects with greater distribution variability.

From Fig. 4, the variation in accuracy and fluctuation patterns across different subjects highlights the individualized nature of EEG signals, which remains a key factor influencing classification performance in cross-subject tasks. This suggests that further optimization is needed in network architectures, loss functions, and training strategies to improve model adaptability.

As illustrated in Fig. 5, the training and testing curves in the nine subjects in the Lee2019-MI data set reveal a gradual and steady convergence rather than a rapid or saturated increase in accuracy. This pattern indicates that while the proposed Exp-G-softmax DDG model can effectively learn discriminative representations over time, the learning process is influenced by the heterogeneous nature of the EEG signals between subjects. These results highlight that inter-subject variability remains a major challenge for domain generalization approaches, since the model convergence rate and final accuracy differ considerably between subjects. Furthermore, although the model demonstrates stable optimization behavior, future work should validate its robustness, computational efficiency, and adaptability in larger-scale, multi-domain, and real-time scenarios.

Beyond subject variability, practical deployment issues also warrant consideration. Although the proposed Exp-G-softmax DDG framework achieves strong generalization without access to target domain data, its computational demand remains non-trivial. The use of multiple convolutional modules and Gaussian-based regularization increases training time and GPU memory consumption, which may limit real-time or embedded BCI applications. In addition, the current framework operates in an offline training–testing paradigm. In real-world BCI systems, online adaptability, that is, the ability to dynamically update model parameters or decision boundaries in response to streaming EEG data, remains essential but has not yet been implemented in this study.

Future research should therefore focus on lightweight model compression, incremental learning, and adaptive calibration mechanisms that can reduce latency and resource requirements while preserving accuracy. Furthermore, integrating online feedback loops and adaptive reweighting strategies could enable real-time decoding with a lower computational overhead, paving the way for practical deployment in clinical and neurorehabilitation contexts.

Conclusions

Through experiments on three publicly available BCI datasets: BNCI2014-001, BNCI2014-004, and Lee2019-MI, the proposed G-softmax DDG method has demonstrated significant performance improvements in cross-subject MI classification tasks. On three public MI datasets, the model’s accuracy curves gradually increase with training epochs and eventually stabilize at a high level. This not only highlights the separability of the dataset or experimental paradigm but also provides a typical case for exploring the performance limits and convergence mechanisms of DDG algorithms.

The multi-source domain joint training strategy combined with the Exp-G-softmax mechanism exhibits strong adaptability in handling EEG distribution shifts across different subjects. This method offers a novel solution for cross-subject MI decoding while also pointing to future research directions:

Incorporating adaptive regularization, dynamic learning rates, and feature reweighting strategies in multi-source domain conditions to further address challenges posed by high-noise or highly variable subjects.

Evaluating the model’s rapid adaptability to online data or new subjects in real-world application scenarios.