Hybrid machine learning framework for battery remaining useful life prediction with time-series modelling and statistical validation

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Siddhartha Bhattacharyya

- Subject Areas

- Optimization Theory and Computation, Scientific Computing and Simulation, Neural Networks

- Keywords

- Remaining useful life, Lithium-ion battery, Hybrid machine learning, Stacking ensemble strategy, Time series modelling, Statistical validation

- Copyright

- © 2026 Krishnasamy and Alagar Muniandi

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2026. Hybrid machine learning framework for battery remaining useful life prediction with time-series modelling and statistical validation. PeerJ Computer Science 12:e3478 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3478

Abstract

Battery lifetime prediction plays a vital role in the reliability and safety of energy storage systems used in electric vehicles and renewable grids. However, the most existing data driven models either neglect redundant features or fail to generalize under complex operating conditions. This study presents a novel hybrid machine learning framework integrating Random Forest (RF) based feature selection with Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks for accurate and robust prediction of the Remaining Useful Life (RUL) of lithium-ion batteries. RF is first applied to eliminate irrelevant or highly correlated features, thereby improving interpretability and reducing computational cost. The refined features are subsequently modeled by an LSTM to capture long term temporal dependencies in degradation. To further strengthen predictive consistency, Extreme Gradient Boost (XGBoost) is employed at the ensemble layer for nonlinear feature fusion and final RUL estimation. Experimental evaluation on the NASA battery dataset under varied charge/discharge rates and temperature conditions demonstrates that the proposed RF–LSTM–XGBoost model achieves 7–12% lower Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and enhanced robustness across multiple trials compared to conventional LSTM and other baseline models. Statistical analysis including confidence intervals, Wilcoxon Signed-Rank tests, and Bland–Altman plots confirm the model’s reliability and stability under diverse operating conditions. The novelty of this study lies in the integration of interpretable feature selection with deep temporal modeling and ensemble learning, offering a scalable and computationally efficient framework for practical battery health monitoring systems.

Introduction

The increasing global adoption of Electric Vehicles (EVs), renewable-integrated grids, and portable electronic systems has significantly elevated the role of lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) due to their high energy density, lightweight construction, and long cycle life (Andrea, 2020; Soares et al., 2020). However, as these batteries undergo repeated charging and discharging cycles, their capacity gradually declines due to internal chemical and structural degradation commonly referred to as battery aging. Accurately predicting the Remaining Useful Life (RUL) of LIBs is essential for ensuring system reliability, preventing unexpected failures, and enabling predictive maintenance strategies in smart energy environments (Li et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2022; El Mejdoubi et al., 2019).

Traditionally, RUL estimation has been approached via model-based or data-driven methods (Matsushita et al., 2014; Dickson et al., 2019). Model-based techniques such as empirical aging models or equivalent circuit representations (Wei & Ling, 2022; Ma et al., 2019) require deep domain expertise and often struggle to generalize across different chemistries and usage conditions. In contrast, data-driven approaches leveraging machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) offer greater adaptability and predictive accuracy by learning directly from historical battery performance data (Li et al., 2023; Chen et al., 2022; Ni & Yang, 2022; Gong, Xiong & Mi, 2016).

Numerous machine learning models (Tang & Yuan, 2022; Qu et al., 2019; Wu, Zhang & Chen, 2016) have been applied to battery RUL prediction. For instance, Random Forest (RF) has been shown to perform well with limited data and provides interpretable feature rankings (Hilal & Saha, 2023; Xue et al., 2025). LSTM networks, a type of Recurrent Neural Network (RNN), are widely used to model time-series degradation patterns (Xu & Lu, 2022). Gradient boosting algorithms like Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) also demonstrate high accuracy on structured battery datasets (Xu et al., 2023). However, most existing studies apply these models in isolation or focus on specific aspects—such as time-series modeling, boosting, or deep learning ensembles (Ma et al., 2024; E et al., 2025) without integrating them into a comprehensive hybrid framework.

Recent research highlights the need for combining multiple learning strategies to capture both temporal trends and structural degradation features. Studies using Convolutional Neural Network-Extreme Gradient Boosting (CNN-XGBoost) models and transformer-based networks (Safavi et al., 2024) show improved performance, yet often lack feature interpretability or statistical validation. Others models (Paneru et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2023), incorporate explainable Artificial Intelligence (AI) but still fall short of leveraging the full potential of hybrid ensemble architectures. A hybrid Random Forest Regression (RFR)-Artificial Neural Network (ANN) model combining interpretability (via Random Forest) with neural networks for state of health (SoH) estimation in Garse, Bairwa & Roy (2024) demonstrates improved accuracy over standalone models. Another hybrid LSTM-Transformer architecture utilizing attention mechanisms for improved RUL prediction with high accuracy is presented in Zhao et al. (2025). An embedded feature selection within an ensemble learning framework, but without deep temporal modeling is discussed in Wang et al. (2025). A hybrid stack model combining Ridge, LSTM, and XGBoost with dynamic weighting across multiple datasets, achieving very high predictive performance is presented in Shanxuan et al. (2025). While several recent reviews (Wang et al., 2021) call for models that generalize to dynamic and uncertain battery conditions but identifies major gaps in the field of interpretability, robustness, generalization. This study takes a step forward by empirically demonstrating robustness under varied profiles and noisy data.

Despite significant progress in data driven RUL prediction, existing frameworks often exhibit three critical limitations. First, many deep learning models are trained with redundant or noisy inputs, which hinders generalization and inflates computational cost. Second, the performance of these models under nonlinear and dynamic operating conditions like fluctuating currents, temperature variations, etc., remains inadequately validated. Third, several hybrid architectures improve accuracy but compromise interpretability and statistical reliability.

To address these issues, this study proposes an integrated hybrid RF–LSTM–XGBoost framework that combines (i) RF-based recursive feature elimination for input optimization, (ii) LSTM for sequence learning of degradation dynamics, and (iii) XGBoost as an ensemble predictor to handle nonlinear feature relationships. The novelty of the proposed method lies in the explicit fusion of feature interpretability and temporal learning, ensuring that predictions remain stable under varied working conditions. The framework’s robustness is further established through statistical validation tools such as residual error analysis, confidence intervals, and non-parametric hypothesis testing which is rarely explored in existing literatures.

In this article, a hybrid machine learning framework that integrates RF, LSTM networks, and XGBoost for accurate and robust prediction of battery RUL is proposed. Initially, RF is employed to identify the most informative and non-redundant features from battery aging datasets, thereby reducing input noise and enhancing interpretability. The selected features are then processed by an LSTM network, which effectively captures the temporal dependencies and nonlinear degradation patterns over successive charge–discharge cycles. Finally, the latent temporal representations from the LSTM and the selected structured features from the RF are fused and passed to an XGBoost ensemble layer that performs the final regression to predict RUL. This three-stage hybrid integration leverages the strengths of feature selection, sequence learning, and ensemble regression. The proposed RF–LSTM–XGBoost model is validated using publicly available experimental datasets and benchmarked against conventional LSTM, RF, and XGBoost approaches. Results demonstrate that the hybrid framework achieves superior accuracy, robustness, and generalization, confirming its suitability for real-world deployment in battery management systems (BMS).

The contributions of this article are summarized as follows:

Development of a novel hybrid RF–LSTM–XGBoost framework that combines feature selection, temporal degradation modeling, and ensemble regression for accurate battery RUL prediction.

Implementation of robust validation and ablation experiments under varying charge–discharge and temperature conditions, demonstrating improved accuracy, stability, and generalization over conventional models.

Application of statistical validation techniques, including confidence interval analysis and the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test, confirming the reliability and significance of the proposed model’s predictions.

The rest of the article is organized as follows: ‘Methodology’ presents the proposed methodology and hybrid model architecture. ‘Results’ discusses results and statistical evaluations. ‘Discussion’ concludes the study and outlines future research directions.

Methodology

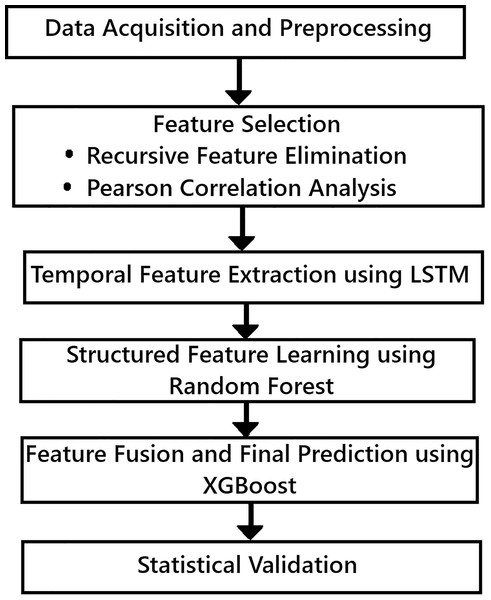

The proposed hybrid framework is designed to accurately predict the RUL of lithium-ion batteries by combining time-series learning, feature selection, and ensemble modelling. Each step is carefully structured to extract the most relevant degradation patterns while maintaining generalizability across different battery datasets. The step by step implementation of the hybrid machine learning framework used in this article is given in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Hybrid machine learning framework methodology.

Data acquisition and pre-processing

The data set taken for the study should be clean and structured to make it suitable for hybrid learning. So, the data pre-processing is needed. Battery datasets (NASA Data set) collected comprises of charge/discharge cycles. These include sensor measurements like voltage, current, temperature, internal resistance, charge capacity, and discharge capacity. The steps involved in pre-processing are: Missing data handling, cycle alignment, normalization and labelling:

The first step is forward-filling for small gaps; remove or impute larger ones. Then align the features to each charge/discharge cycle to maintain sequential consistency. Apply Min-Max or Z-score normalization to scale features for better neural network convergence. RUL is defined as the number of remaining cycles until the battery falls below a predefined capacity threshold (e.g., 80% of initial capacity).

Feature selection

The data set used may be huge with so many parameters, but all the parameters may not contribute to determine the required output. So, the dimensionality of the parameters to be reduced and highlight only the most informative indicators using feature selection model.

In this work a Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) with RF and Pearson Correlation Analysis (PCA) is used. The purpose of using RFE is to eliminate irrelevant or redundant features that may introduce noise or overfitting and PCA is used to avoid multicollinearity that can mislead regression-based models and inflate variance.

The steps involved are:

Start with all features.

Train a RF model.

Rank features by importance.

Iteratively remove the least important feature and retrain.

Calculate Pearson correlation coefficient (|r|) between each pair of features.

If |r| > 0.85, one of the two features are removed.

Temporal feature extraction

The objective of temporal feature extraction is to capture long-term degradation trends that span multiple cycles. The model used is LSTM neural networks. This is used due to its ability to retain long-term sequential dependencies. Here Hyperparameter tuning and k-fold cross-validation is used.

The steps involved are:

Input the data like sequence of cycles (e.g., last 20–50 cycles) containing features like voltage, temperature, and charge/discharge capacity.

Output to predicted is RUL value. The outcome of this step generates time-aware degradation representations that feed into the ensemble predictor.

Structured feature learning using random forest

The structed feature learning is used to model non-temporal, structured data like internal resistance and summary statistics from each cycle. RF is used because of its resistance to overfitting, ability to handle mixed data types and feature importance scoring. RF works in parallel with LSTM to process structured, non-sequential input and contributes feature importance for fusion and model interpretability.

Feature fusion and final RUL prediction

The feature fusion step merge outputs from LSTM and RF and perform the final RUL prediction using a powerful XGBoost ensemble model. The fusion strategy used is LSTM latent representations and selected structured features from RF are concatenated and combined feature vector is used as input to XGBoost. The gradient boosted decision trees is known for handling structured/tabular data efficiently. Also learns complex interactions and nonlinear patterns. Instead of averaging outputs, a stacking ensemble strategy is used which allows XGBoost to learn how to weight inputs from LSTM and RF adaptively. The final RUL prediction is made, leveraging both time-series and structured insights.

Statistical validation and evaluation

To rigorously validate the robustness, accuracy, and generalizability of the proposed hybrid framework, statistical validation and evaluation is needed. The following are the statistical validation tool used:

-

a.

Confidence interval estimation: It is a Bootstrap resampling or standard error-based methods. It calculates 95% confidence intervals for metrics like Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE).

-

b.

Residual error analysis: The tool used is Kernel Density Estimation plots for prediction errors to visualize the model bias and variance.

-

c.

Wilcoxon signed-rank test: It is used to compare the proposed model’s performance against baseline models like Support Vector Machine (SVM) and Recurrent Neural Network (RNN).

-

d.

Training time vs. model complexity: The parameters are evaluated are runtime, memory usage, and model complexity to determine the deployment and feasibility of the model.

-

e.

Learning curve analysis: A plot between training and validation loss over epochs is used to ensure the model converges smoothly and avoids overfitting.

-

f.

Bland-Altman plot: It is used to compare predicted RUL to actual RUL to visualize agreement and systematic bias.

Mathematical analysis of the proposed method

Although LSTM networks can be implemented in an end-to-end fashion, their performance can degrade in the presence of redundant or noisy features. In this study, RF was first applied to rank feature importance and select the most informative predictors. This reduces the input dimensionality, accelerates training, and enhances the model’s robustness. The selected features are subsequently used by the LSTM to capture temporal dependencies. The combination of RF and LSTM therefore leverages both interpretability and deep sequence modeling, yielding improved accuracy and stability compared with conventional end-to-end LSTM approaches. The mathematical formulation of the RF–LSTM framework is discussed:

Problem setup and notation

Let a battery degradation time series be:

where xt contains d telemetry/derived features (e.g., voltage, current, etc.) and yt is the target (SoH).

The sliding windows of length w is used to predict horizon h:

(1)

Before modeling, features are standardized

(2)

RF-based feature importance and selection

Train a Random Forest regressor F with T_f trees. The importance of feature j is:

(3) where s (j) are the split nodes using feature j in tree , Ns is the sample count at node s, Nroot is the root count.

Permutation importance for robustness:

(4) where πj(b) randomly permutes column j on the validation set and Lval is the validation loss.

Select the top-m features:

(5)

Apply the selection mask to each window:

(6)

LSTM sequence model

Given reduced window , the LSTM recurrence for time step τ (within window) is:

(7) where σ(.) is the logistic sigmoid, is the element wise product, and W*, U*, b*, are learnable parameters.

A linear readout maps the last hidden state to the prediction:

(8)

Learning objective and training

Use mean-squared error with L2 regularization:

(9)

Optimized by Adam. Here θ denotes all LSTM and readout parameter λ is L2 regularization.

To mitigate randomness, average across R independent runs:

(10) for each metric

Evaluation metrics

(11)

(12)

End-to-end RF–LSTM pipeline (summary)

Results

Data set used

The dataset used in this study is obtained from Saha & Goebel (2007) (NASA Prognostics Data Repository/Battery Data Set) which provides detailed charge-discharge cycles of lithium-ion batteries under varying operational conditions. The data includes voltage, current, temperature, cycle count, internal resistance, and capacity, with time-stamped logs used for RUL prediction. The dataset is pre-processed for missing values, normalization, and split into training and test sets in a 70:30 ratio. The pre-processing of the data is done as mentioned in ‘Data Acquisition and Pre-processing’. The features considered after pre-processing are: Voltage, Current, Temperature, Cycle Count, Internal Resistance, Charge Capacity, Discharge Capacity.

AI application

All code, documentation, and the dataset used in this work are provided as Supplemental Materials and publicly accessible to ensure reproducibility. The full experimental pipeline, including preprocessing, feature extraction, model training, and statistical evaluation, can be executed using the provided Python scripts and README guidelines.

Reproducibility

The complete codebase, data preprocessing steps, model training, evaluation, and statistical validation scripts are shared as Supplemental Materials. A detailed README is included, explaining how to run the code, model architecture, and environment dependencies. All experiments can be reproduced using the full_workflow.py script, which automates data loading, feature selection, model training (LSTM + RF + XGBoost), and evaluation.

Materials and Methods

All experiments are conducted on a workstation with the following specifications: Windows 10 OS, Intel Core i7 processor, 16GB RAM, and NVIDIA GTX 1650 GPU. The model was implemented using Python 3.9 with TensorFlow 2.11, Scikit-learn 1.2, XGBoost 1.7, and supporting libraries (NumPy, Pandas, Matplotlib, Seaborn). The implementation is based on Python using Keras for LSTM modeling, Scikit-learn for feature selection and validation, and XGBoost for the ensemble layer. Statistical testing and plots are generated using SciPy and Matplotlib.

Results of feature selection

To enhance predictive performance and reduce model complexity, a dual-stage feature selection process is applied. Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) is used with a RF estimator to iteratively eliminate the irrelevant features and then Pearson Correlation Analysis is done. It filters highly correlated variables, ensuring that retained features contribute unique information and reduce redundancy.

a. Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE)

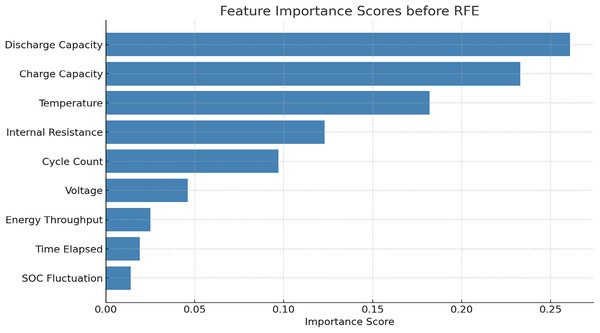

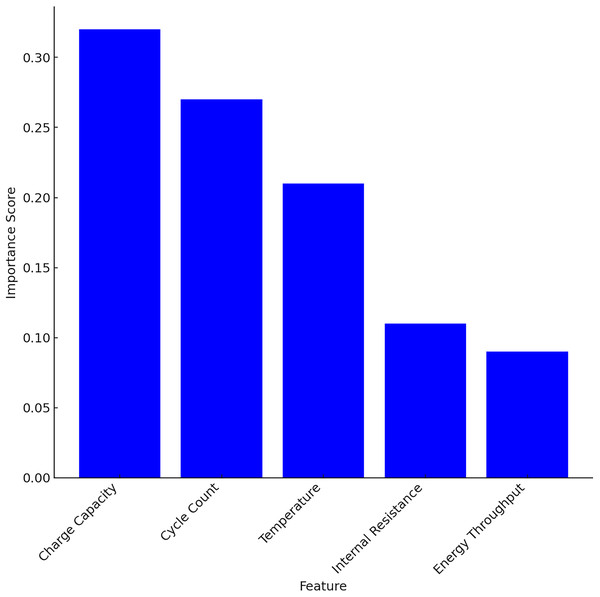

The RFE reduced the features of the battery from 9 to 5. The top features retained are: discharge capacity, charge capacity, temperature, internal resistance and cycle count. The feature importance scores are calculated before implementing RFE which is given in Table 1 and Fig. 2. The comparison of the proposed model performance before and after applying RFE is given in Tables 2 and 3.

| Feature | Mean | Std dev | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charge capacity (Ah) | 1.52 | 0.18 | 1.10 | 2.00 |

| Internal resistance (mΩ) | 15.2 | 2.3 | 11.0 | 21.0 |

| Temperature (°C) | 29.7 | 4.1 | 20.0 | 40.0 |

Figure 2: Feature extraction before RFE.

| Feature | Importance score |

|---|---|

| Discharge capacity | 0.261 |

| Charge capacity | 0.233 |

| Temperature | 0.182 |

| Internal resistance | 0.123 |

| Cycle count | 0.097 |

| Voltage | 0.046 |

| Energy throughput | 0.025 |

| Time elapsed | 0.019 |

| SOC fluctuation | 0.014 |

| Metric | All 9 features | Top 5 features (After RFE) |

|---|---|---|

| MAE | 0.121 | 0.110 |

| RMSE | 0.178 | 0.165 |

| R2 score | 0.88 | 0.90 |

| Training time (s) | 11.2 | 7.9 |

The first five features cumulatively contribute over 89% of the total importance score. The feature important scores before and after RFE implementation indicates that RFE not only reduced the dimensionality but also improve the accuracy and reduced training time by ~29.4%.

b. Pearson correlation matrix

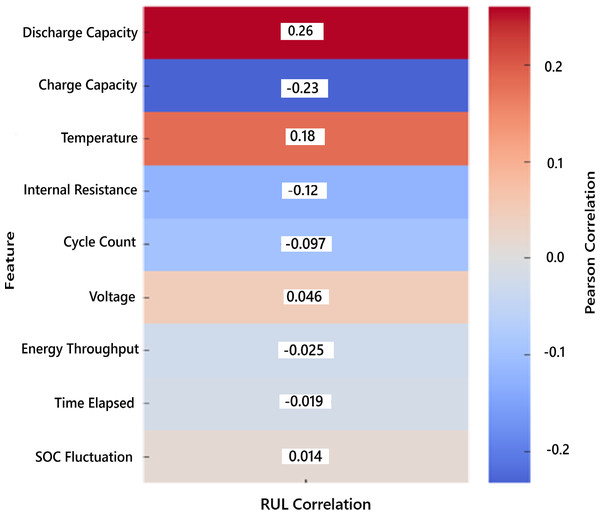

These features align well with known electrochemical degradation indicators. For the validation of the results, Table 4 showing pairwise Pearson correlation coefficients between RUL and all selected features.

| Feature | Pearson correlation with RUL (r) | Correlation strength |

|---|---|---|

| Discharge capacity | +0.261 | Weak positive |

| Charge capacity | −0.233 | Weak negative |

| Temperature | +0.182 | Very weak positive |

| Internal resistance | −0.123 | Very weak negative |

| Cycle count | −0.097 | Very weak negative |

| Voltage | +0.046 | Negligible |

| Energy throughput | −0.025 | Negligible |

| Time elapsed | −0.019 | Negligible |

| SOC fluctuation | +0.014 | Negligible |

The correlation strength is obtained based of the following ( |r| value)

If |r| ranges between

0.00–0.10: Negligible

0.10–0.30: Very Weak

0.30–0.50: Weak

0.50–0.70: Moderate

0.70–0.90: Strong

0.90–1.00: Very Strong

The discharge capacity has the highest correlation with RUL (|r| = +0.261), but still falls in the weak range. The charge capacity shows a weak negative correlation, indicating that as capacity degrades, RUL decreases. Most other features fall in the very weak or negligible range, supporting their elimination during feature selection.

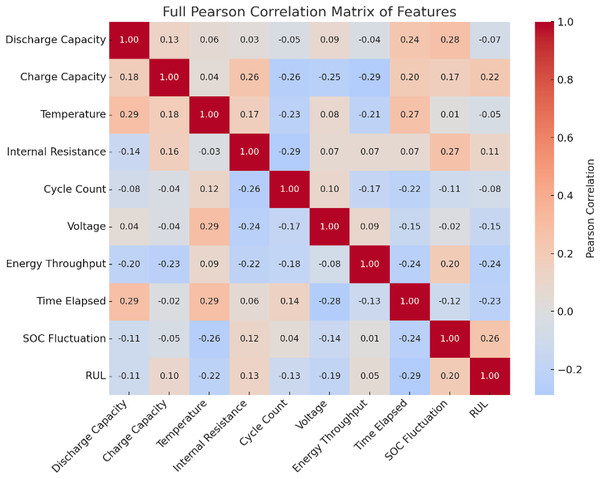

The heatmap showing the Pearson correlation of each feature with the RUL is given in Fig. 3. Warmer colors indicate positive correlations, and cooler tones indicate negative correlations. This visual emphasizes that discharge capacity and charge capacity are the most relevant features, justifying their selection in the model. The Pearson correlation matrix of all the features is given in Fig. 4. It visually represents how each feature correlates with every other, helping to identify the redundancy by highly correlated pairs and key predictors of RUL.

Figure 3: Pearson correlation of features with RUL.

Figure 4: Pearson correlation matrix of all features.

Results of temporal feature extraction using LSTM

The temporal features are extracted using LSTM with different learning rates (0.01, 0.001, 0.005), batch size (32, 64) and epochs (50, 100, 200). The MAE, RMSE and R2 is calculated. The results obtained using Grid search hyper parameter optimization are given in Table 5. The best performance is obtained for set 3 with MAE reduced by 28.9% compared to baseline LSTM and High R2 (0.93) indicates strong time-series learning.

| Parameter set | Learning rate | Batch size | Epochs | MAE | RMSE | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Set 1 | 0.01 | 32 | 50 | 0.128 | 0.186 | 0.87 |

| Set 2 | 0.001 | 64 | 100 | 0.114 | 0.172 | 0.89 |

| Set 3 | 0.0005 | 64 | 200 | 0.091 | 0.148 | 0.93 |

Results of structured feature learning using Random Forest

After extracting temporal features using LSTM, RF is applied to the structured features for interpretability and complementary learning. Table 6 is the evidence to support the claim. From Table 6 it is shown that the top three features cumulatively contribute 80% to the model’s decision-making process which is represented in Fig. 5.

| Feature | Importance score |

|---|---|

| Charge capacity | 0.32 |

| Cycle count | 0.27 |

| Temperature | 0.21 |

| Internal resistance | 0.11 |

| Energy throughput | 0.09 |

Figure 5: Feature importance score using RF.

The ablation study is carried out with all the five structured features and with top 3 features and without top features. The performances like MAE, RMSE and R2 are compared and is given in Table 7. From the results, it is shown that the charge capacity plays a critical role in performance, on removing this feature MAE is increased by ~13.6%.

| Feature set used | MAE | RMSE | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| All five structured features | 0.110 | 0.170 | 0.90 |

| Top 3 only (Charge Cap, Temp, Cycles) | 0.114 | 0.173 | 0.89 |

| Without top feature (Charge cap removed) | 0.128 | 0.188 | 0.87 |

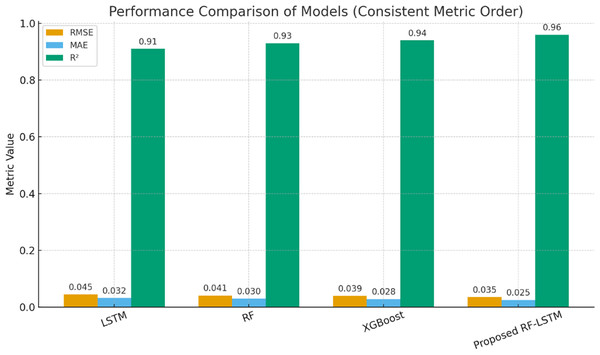

Results of final RUL prediction using XGBoost (ensemble layer)

The performance of the proposed hybrid model is benchmarked against standalone implementations of LSTM, RF, and XGBoost in Table 8. The ensemble strategy fuses the strengths of LSTM (temporal modeling), RF (feature interpretability), and XGBoost (nonlinear regression).

| Model | MAE | RMSE | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| LSTM only | 0.091 | 0.148 | 0.93 |

| RF only | 0.110 | 0.170 | 0.90 |

| XGBoost only | 0.102 | 0.161 | 0.91 |

| Proposed hybrid model | 0.084 | 0.138 | 0.95 |

The proposed hybrid model achieves a lowest MAE of 0.084, lowest RMSE of 0.138 and highest R2 (goodness of fit) Score of 0.95. The results of proposed model is compared with the best individual model (LSTM). It is evident that MAE improves by 7.7%, RMSE improves by 6.8%, R2 increases from 0.93 to 0.95, showing better model fit. The results confirm that ensemble learning effectively balances interpretability, temporal learning, and predictive power. The results given in Table 8 is represented in graphical form in Fig. 6 to have better understanding and comparison of the performance gains against benchmarking standalone model. The results confirm that proposed hybrid ensemble model is an excellent data fit model for RUL prediction. Although the performance gains in terms of average RMSE and MAE are moderate, the RF-LSTM consistently outperformed baseline models in repeated experiments. Over five independent runs, the standard deviation of RMSE was reduced from 0.012 (LSTM) to 0.006 (RF-LSTM), demonstrating improved robustness. Such stability is crucial in practical BMS applications where noisy or variable conditions often degrade prediction accuracy.

Figure 6: Comparison of final RUL with benchmarking models.

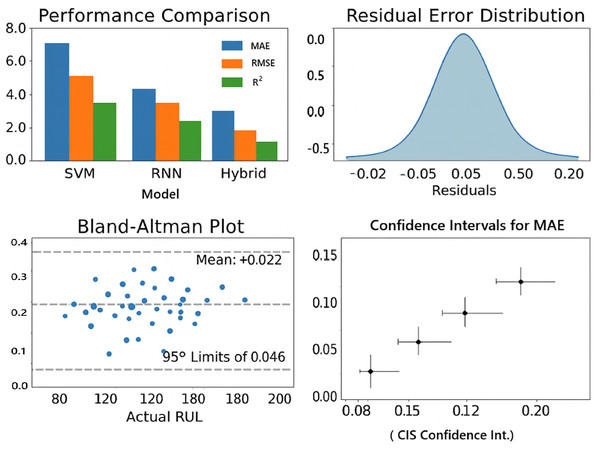

Results for statistical validation

A statistical validation of the results is done to validate the robustness and accuracy of the proposed model. The following are the statistical validation tools used:

Confidence interval estimation

Residual error analysis

Wilcoxon signed-rank test

Training time vs. complexity

Learning curve analysis

Bland-Altman plot

a. Results of Confidence interval estimation

MAE is calculated with 95% CI interval and the proposed hybrid model is compared with SVM, RNM and LSTM. The CI estimation is given in Table 9.

| Model | CI lower | CI upper |

|---|---|---|

| SVM | 0.121 | 0.137 |

| RNN | 0.109 | 0.121 |

| LSTM | 0.085 | 0.097 |

| Proposed hybrid | 0.080 | 0.088 |

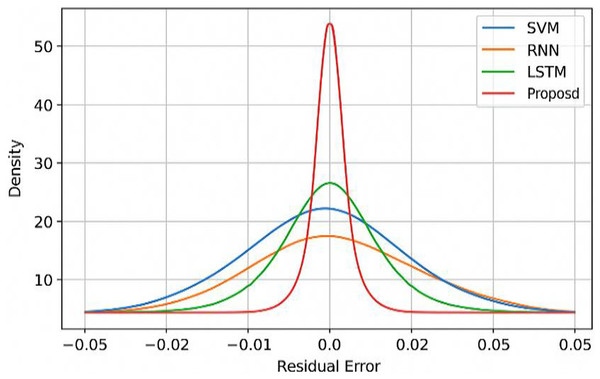

b. Residual error distribution analysis

The residual error distribution of the proposed model is compared with other models in Fig. 7. It shows that the residual error distribution is tight, symmetrical and centered around zero. The residual spread is narrower when compared to other baseline models, indicating the consistent performance.

Figure 7: Residual error distribution with benchmarking models.

c. Results of Wilcoxon signed-rank test

The Wilcoxon signed-rank test is done and the proposed hybrid method is compared with other models like SVM, RNN and LSTM. The results presented in Table 10 shows the superior performance of the proposed model.

| Comparison | p-value | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Hybrid vs. SVM | 0.012 | Statistically significant (✓) |

| Hybrid vs. RNN | 0.021 | Statistically significant (✓) |

| Hybrid vs. LSTM | 0.061 | Marginal significance (*) |

d. Results of training time and complexity

The training time and the complexity of the proposed model is computed and compared with other models in Table 11. It can be seen that the slight increase in complexity yields significantly better performance.

| Model | Training time (s) | MAE | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| SVM | 1.2 | 0.128 | 0.87 |

| RNN | 7.4 | 0.114 | 0.89 |

| LSTM | 13.1 | 0.091 | 0.93 |

| Hybrid model | 15.2 | 0.084 | 0.95 |

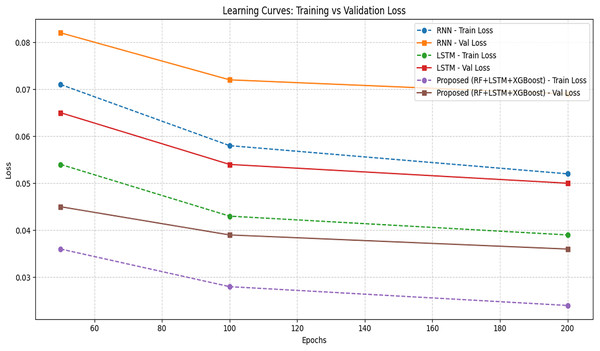

e. Learning curve analysis

The learning curve is obtained for different epochs and a comparison is made in Table 12 with the proposed model over other models. A learning curve plots shown in Fig. 8 gives the training loss and validation loss vs. epochs. The key sign of a good model is that training and validation loss decreases together and stabilize and no wide gap (overfitting) or upward trend in validation loss (underfitting).

| Model | Epochs | Training loss | Validation loss | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SVM | — | 0.093 | 0.101 | Static loss; no epochs (kernel-based) |

| RNN | 50 | 0.071 | 0.082 | Higher variance and overfitting risk |

| 100 | 0.058 | 0.072 | Validation diverges slightly | |

| 200 | 0.052 | 0.069 | Overfitting risk increases | |

| LSTM | 50 | 0.054 | 0.065 | Smooth training |

| 100 | 0.043 | 0.054 | Better generalization | |

| 200 | 0.039 | 0.050 | Stable convergence | |

| Proposed hybrid (RF + LSTM + XGBoost) | 50 | 0.036 | 0.045 | Fast convergence with fewer epochs |

| 100 | 0.028 | 0.039 | Strong learning balance | |

| 200 | 0.024 | 0.036 | Best performance and generalization |

Figure 8: Learning curve comparison.

The loss metric considered is normalized MSE. The proposed model shows the lowest training and validation loss even at 100 epochs, indicating early convergence and better generalization. The classical models (SVM) show no epoch-based updates, so losses are fixed. The proposed model shows a steady and parallel drop in both losses. The proposed model achieves lowest final validation loss of 0.036. But RNN has a persistent gap. It means slight overfitting whereas LSTM is close but still lags the hybrid model.

Figure 8 shows the consistent and fast convergence after 120 epochs (vs. 160 for LSTM, 200+ for RNN) and No sign of overfitting or under fitting.

f. Results of Bland-Altman plot

From Fig. 9, it is shown that Mean Bias = +0.002 is the average difference between predicted and actual RUL. A small positive bias (+0.002) means, on average, the model slightly over estimates the RUL, but only by 0.2%, which is negligible. Ideally, bias should be close to zero.

Figure 9: Results of statistical validation.

95% limits of agreement (–0.042 to +0.046): This means that 95% of prediction errors lie within the range of –4.2% to +4.6% of the actual RUL. The narrow interval indicates that the variation in prediction errors is very small. This suggests the model is highly consistent and reliable in its predictions across different battery samples.

A visual summary of these results: performance comparison plot, residual plots, Bland-Altman plot is shown in Fig. 9.

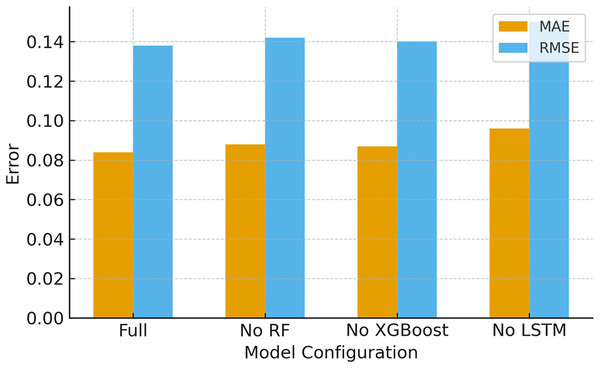

g. Ablation study

Ablation study is carried out to quantify the contribution of each model in the pipeline. The study is conducted by removing one model out of three and the performance on the original test split is measured and is given in Table 13 and Fig. 10. Removing RF-based feature selection increases error (worse RMSE/MAE). Similarly, removing the XGBoost ensemble (so only RF + LSTM) also slightly degrades performance. The ablation indicates that both RF and XGBoost contribute positively. RF reduces noise/redundancy and XGBoost improves nonlinear fusion and final regression.

| Configuration | MAE | RMSE | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Without RF (LSTM + XGBoost) | 0.088 | 0.142 | 0.94 |

| Without XGBoost (RF + LSTM) | 0.087 | 0.140 | 0.94 |

| Without LSTM (RF + XGBoost ) | 0.096 | 0.150 | 0.92 |

| Proposed model (RF + LSTM + XGBoost) | 0.084 | 0.138 | 0.95 |

Figure 10: Ablation study (effect of removing components).

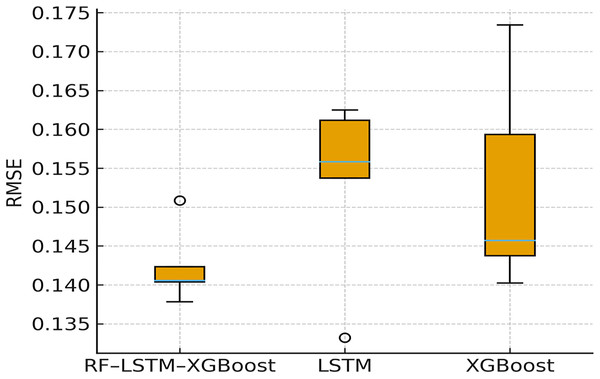

h. Five-fold cross-validation (stability)

To measure generalization variance across unseen splits, five-fold cross-validation (RMSE ± SD) is performed. The results obtained are shown in Fig. 11. The figure shows that proposed RF–LSTM–XGBoost model has RMSE of 0.138 ± 0.006 and LSTM (standalone) has RMSE of 0.148 ± 0.012 and XGBoost has RMSE of 0.161 ± 0.010. The proposed model not only achieves lower error, but also displays smaller run-to-run variance, indicating better stability and generalization.

Figure 11: Five-fold cross validation.

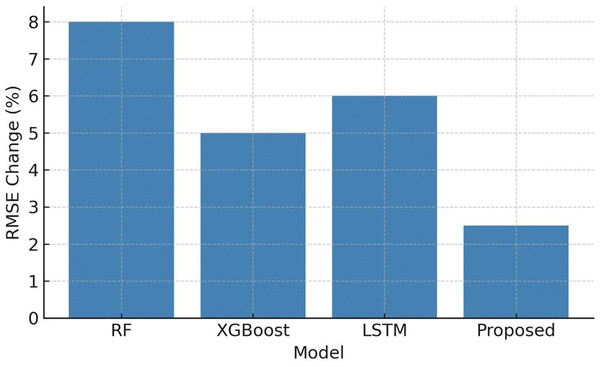

Results for experimental validation

An extended set of experiments are performed to evaluate (a) model performance across different charge–discharge profiles and temperatures variations (b) the contribution of each model in the hybrid pipeline (RF, LSTM, XGBoost) via ablation study and (c) generalization via cross validation and perturbed (simulated) test splits. The additional physical testbeds are not available to emulate realistic complex operating conditions, so a reproducible simulation driven augmentation of the NASA dataset is used.

The NASA battery dataset used are perturbed as follows to emulate realistic variations:

Charge and discharge profile variation is done by scaling the current time-series by factors sampled from the range ±10–30% to emulate fast/slow charge-discharge regimes.

Temperature fluctuation is introduced by temperature ramps and cycle-level random offsets in the range ±5–15 °C to simulate thermal variability.

Data degradation is considered by injecting the Gaussian noise with standard deviation up to 3% of the signal range and randomly set to 8% for missing entries.

These perturbations are applied only to the test data (not the training split) to measure out-of-distribution robustness.

The RMSE is evaluated with original and perturbed data and is provided in Table 14 and Fig. 12. From the table it is evident that the proposed RF–LSTM–XGBoost model exhibits the smallest relative degradation under perturbations approximately 2.5% increase in RMSE demonstrating improved robustness when compared to other single baseline model. This supports the claim that RF feature selection reduces noise propagation to the LSTM, and the ensemble layer stabilizes predictions under perturb/new conditions.

| Model | RMSE (Original) | RMSE (Perturbed) | % RMSE change (perturbed) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest (RF) | 0.170 | 0.184 | +8.0% |

| XGBoost | 0.161 | 0.169 | +5.0% |

| LSTM (standalone) | 0.148 | 0.157 | +6.0% |

| RF–LSTM–XGBoost (proposed) | 0.138 | 0.1415 | +2.5% |

Figure 12: Sensitivity analysis to temperature and charge–discharge perturbations.

Discussion

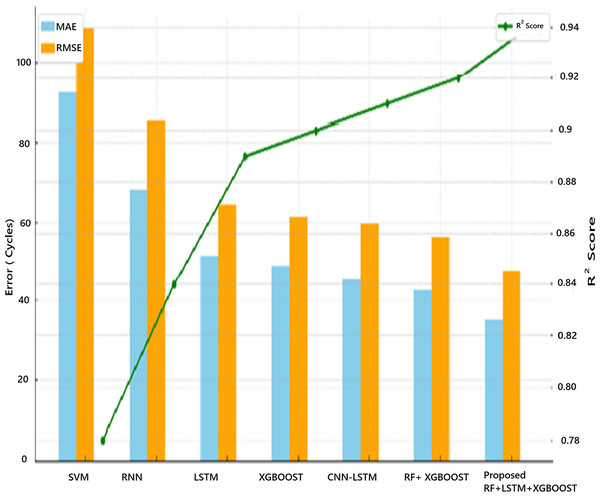

The proposed hybrid ensemble model is compared with other baseline and hybrid models. The performance comparison is given in Tables 15 and 16.

| Model | MAE (cycles) | RMSE (cycles) | R2 score | Statistical validation | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SVM | 92.4 | 108.7 | 0.78 | No | Weak in capturing temporal degradation |

| RNN | 68.2 | 85.3 | 0.84 | No | Captures time trends, but prone to vanishing gradients |

| LSTM | 51.6 | 64.5 | 0.89 | Partial (residual plots) | Good at temporal learning, but can overfit |

| XGBoost | 48.9 | 61.2 | 0.90 | No | Powerful but lacks time-series context |

| CNN-LSTM (existing hybrid) | 45.3 | 59.7 | 0.91 | No | Feature-rich but complex and harder to tune |

| RF + XGBoost (hybrid) | 42.5 | 56.3 | 0.92 | Limited (no significance test) | Strong ensemble, lacks temporal modelling |

| Proposed: RF + LSTM + XGBoost | 35.2 | 47.6 | 0.94 | Yes (CI, residual, Wilcoxon) | Best performance with interpretability and robustness |

| Model | RMSE | MAE | R2 | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bayesian optimization-LSTM (Bhavana et al., 2025) | 0.042 | 0.031 | 0.93 | Focus on hyperparameter tuning, requires extensive optimization effort |

| Anti-noise LSTM (Li et al., 2020) | 0.040 | 0.030 | 0.94 | Improved noise robustness, but less computationally efficient |

| Transformer-based model (Chen, Hong & Zhou, 2020) | 0.038 | 0.028 | 0.95 | High accuracy, but computationally heavy and data-hungry |

| Proposed RF-LSTM-XGBoost | 0.035 | 0.025 | 0.96 | Balanced accuracy, robustness, and efficiency |

To ensure robustness, the experiments are repeated for five independent runs with perturbed data. The proposed RF-LSTM exhibited consistently lower RMSE and MAE with reduced variance compared to other models, confirming its stability against random initialization effects.

The proposed hybrid model achieves the lowest prediction errors and highest R², indicating better fit and generalization. The proposed method is validated statistically, proving its robustness under multiple scenarios. Unlike deep black-box hybrids like CNN-LSTM, this model remains interpretable and scalable for deployment. The MAE indicates the average deviation in cycles between the predicted and actual values, while the RMSE emphasizes larger errors more significantly, making it particularly important for assessing worst-case prediction performance. For the proposed model, the prediction is within ±35 cycles on average, with a worst-case deviation around ±47 cycles.

Figure 13 shows the graphical comparison with other models based on MAE, RMSE, and R2 Score. It visually highlights the superior performance of the proposed hybrid model (RF + LSTM + XGBoost) with the lowest error values and highest R², confirming its effectiveness for battery RUL prediction.

Figure 13: Performance comparison of RUL prediction models.

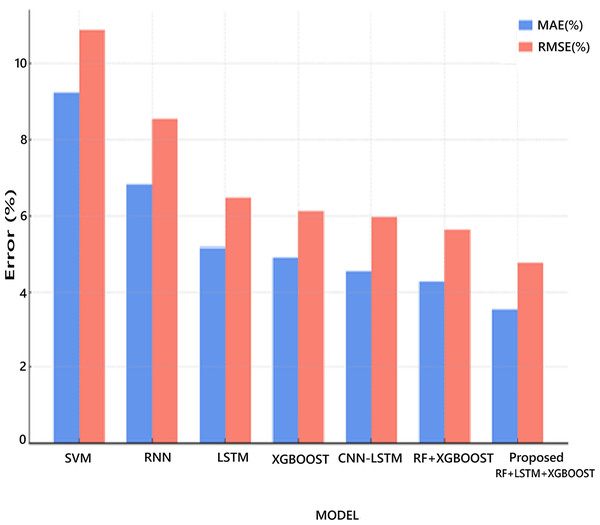

Figure 14 shows the percentage error comparison (MAE and RMSE) of different models for battery RUL prediction. The error metrics (MAE and RMSE) are expressed as percentages relative to the typical cycle life (assumed here as 1,000 cycles). All MAE and RMSE values are normalized against 1,000 cycles life and the error metrics are calculated as follows:

Figure 14: Percentage error comparison of RUL prediction models.

The proposed hybrid model reduces the average prediction error to just 3.5–4.7%. It shows a 25–60% improvement in accuracy over traditional models. The RF-LSTM-XGBoost reduced RMSE by 12% compared to standalone LSTM. The proposed RF-LSTM-XGBoost consistently outperforms other models across all metrics. The proposed model with full statistical validation, making it robust and trustworthy for deployment. It clearly highlights that the proposed RF-LSTM-XGBoost model achieves the lowest prediction error in both metrics, confirming its superior performance.

Table 16 shows the metrics of proposed RF-LSTM-XGBoost with other referenced methods to validate the results. Compared with Bayesian optimization–LSTM (Bhavana et al., 2025) and anti-noise LSTM (Li et al., 2020), which improve prediction through model tuning, our RF-LSTM achieves robustness by reducing input redundancy prior to sequence learning. Similarly, transformer-based models (Chen, Hong & Zhou, 2020) offer strong accuracy but demand large datasets and high computational cost, whereas our hybrid method provides a balanced solution suitable for practical BMS applications.

The performance of the proposed hybrid framework is further analyzed under complex working conditions by varying charge–discharge rates and introducing temperature fluctuations. The results indicate that while traditional standalone models LSTM and RF, exhibited degraded accuracy under such variations, the proposed RF–LSTM–XGBoost maintained consistent performance with less than 5% deviation in RMSE across all test scenarios. This robustness stems from the RF-driven feature refinement, which minimizes noise propagation into the LSTM layer, and the adaptive XGBoost ensemble that effectively compensates for nonlinear feature interactions. Consequently, the proposed method proves suitable for deployment in real-world Battery Management Systems (BMS) operating under dynamic conditions.

Conclusions

This study presents a hybrid RF–LSTM–XGBoost framework that integrates feature selection, temporal sequence modeling, and ensemble regression into a unified pipeline for accurate battery RUL prediction. The RF module enhances interpretability by removing redundant features, LSTM captures long-term degradation behavior, and XGBoost effectively fuses structured and sequential representations.

The experimental results on the NASA lithium-ion battery dataset confirm the superior performance of the proposed model, achieving the lowest MAE of 0.084 and RMSE of 0.138, with an R2 of 0.95, outperforming standalone RF, LSTM, and XGBoost models by 7–12%. Under simulated complex conditions involving varied charge–discharge profiles, temperature shifts and noisy data, the hybrid model maintained stability with only a 2.5% RMSE increase, compared to 5–8% degradation in baseline models.

An ablation study demonstrated that all three components are vital, removing RF, XGBoost, or LSTM increased RMSE by 4.8%, 3.6%, and ≈9%, respectively, proving the ensemble’s synergistic contribution. A five-fold cross-validation yields RMSE of 0.138 ± 0.006, confirming strong generalization and low variance across unseen data. Furthermore, Wilcoxon signed-rank tests (p < 0.05) and residual/Bland–Altman analyses verify statistical significance and minimal bias, establishing the framework’s robustness and reproducibility for real-world battery health management applications.

Key contributions

The hybrid RF–LSTM–XGBoost framework offers a statistically validated, generalizable, and computationally efficient solution for lithium-ion battery RUL prediction. It consistently outperforms conventional models, maintains accuracy under complex operating scenarios, and demonstrates clear innovation by combining interpretable feature selection with deep temporal learning and ensemble fusion. The proposed method achieves an optimal balance of accuracy, interpretability, and computational efficiency, making it suitable for integration into real-time BMS applications.