Enhanced fire detection: a weighted bounding box fusion approach based on Dempster–Shafer theory

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Davide Chicco

- Subject Areas

- Artificial Intelligence, Autonomous Systems, Databases

- Keywords

- Fire detection, Deep learning, Computer vision, YOLO, Data fusion, Bounding boxes, Dampster–Shafer theory

- Copyright

- © 2026 Choutri et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2026. Enhanced fire detection: a weighted bounding box fusion approach based on Dempster–Shafer theory. PeerJ Computer Science 12:e3476 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3476

Abstract

In this study, we present an advanced fire detection approach using an improved weighted bounding box fusion technique based on Dempster–Shafer theory. A key challenge in fire detection is the inherent uncertainty in distinguishing true fire events from false positives (e.g., fire-like objects or background noise). Our approach addresses this by fusing overlapping bounding boxes from a You Only Look Once (YOLO)-based detector, explicitly modeling conflicts between fire and non-fire classifications. Dempster–Shafer theory plays a critical role in quantifying uncertainty and reconciling contradictory evidence, enabling more robust decision-making. We further introduce a confidence-aware weighting scheme to prioritize highly reliable detections during fusion. On a diverse fire image dataset, YOLOv5 combined with our Dempster–Shafer Weighted Boxes Fusion (DS-WBF) method achieved a precision of 0.814, recall of 0.863, AP0.5 of 0.875, and AP0.5–0.95 of 0.542, representing gains of +1.24%, +1.17%, +2.46%, and +4.63% over traditional Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS). These improvements reduce false alarms and enhance true positive rates, enabling more reliable early fire detection for real-time monitoring systems.

Introduction

Fire has been a pivotal factor in human history, serving as both a beneficial tool and a potential hazard when not properly controlled. With advancements in electronic devices, sensors, and information and communication technologies, the construction industry is experiencing a significant transformation (Choutri et al., 2022). This digital revolution has led to reduced operational costs and improved overall performance. However, as advancements in building materials and insulation technologies continue to evolve and become more widespread, the potential risks associated with fire—particularly regarding loss of life and financial assets—have also increased (Khan et al., 2022b). Currently, fire detection primarily relies on temperature or smoke sensors, which, while effective, come with certain limitations. These sensor-based methods are not only expensive but are also generally limited to detecting indoor fires. To mitigate these challenges, various methods have been developed to detect fires or smoke using conventional video surveillance cameras. Among these are image-based fire detection techniques, which are generally categorized into two groups: traditional color-based methods and deep learning approaches. Color-based methods focus on identifying the characteristic hues of flames. However, the detection process is complicated by the fact that different types of fires can produce flames of varying colors (An et al., 2022).

Nearly 70,000 wildfires occur globally each year, causing widespread devastation to forest ecosystems. These fires severely impact forest cover, soil quality, tree growth, and overall biodiversity. The destruction of vast hectares of forest land results in barren, ash-covered landscapes, which are no longer suitable for vegetation growth. Additionally, the intense heat generated by wildfires devastates animal habitats, leading to further ecological imbalance. To mitigate these disasters and protect lives and property, it is crucial to detect forest fires at the earliest stages, preventing them from escalating into catastrophic events. Early detection is essential to promptly extinguish these fires and minimize their harmful effects (Praneash, Rashmika & Natarajan, 2022). For instance, smoke and thermal sensors need to be in close proximity to the fire, which limits their ability to determine the fire’s size or exact location. Ground-based equipment also suffers from limited surveillance range, while deploying human patrols is impractical in large, remote forest areas. While satellite imagery is useful, it struggles to detect early-stage fires due to limited resolution and cannot provide continuous forest monitoring, mainly because of restricted path planning flexibility. The use of manned aircraft, though effective, is costly and necessitates skilled pilots, who face dangerous conditions and the risk of fatigue, as noted by Zhang et al. (2022).

In this study, we present a novel contribution to the field of forest fire detection by proposing an advanced approach that integrates state-of-the-art detection techniques with an innovative fusion approach. Our work leverages aerial imagery and enhances detection accuracy through a Weighted Boxes Fusion (WBF) strategy grounded in Dempster–Shafer theory (DST). Unlike traditional methods, our approach effectively manages the uncertainty and conflicting evidence from multiple detection algorithms, ensuring more reliable and robust fire detection. By incorporating a confidence-based weighting scheme, our approach prioritizes the most credible information, thereby significantly improving the accuracy and timeliness of early fire detection. This contribution addresses the limitations of existing sensor-based and image-based methods, offering a more effective solution for mitigating the devastating impacts of wildfires.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows: ‘Related Work’ presents a review of related works in the fields of computer vision and data fusion for fire detection. “Background on Dempster–Shafer Theory” details the proposed fire detection scheme, including dataset collection and various You Only Look Once (YOLO) models. The discussion on the weighted boxes fusion method is presented in ‘Materials and Methods’. In ‘Proposed Approach’, we elaborate on the proposed approach and the integration of DST with the WBF algorithm. ‘Results and Discussions’ evaluates the performance of the proposed system, comparing different models and algorithms. Finally, ‘Conclusion’ summarizes the conclusions of the study and suggests potential directions for future research.

Related work

Computer vision for fire detection

The rising urbanization has heightened the risk of fires, necessitating improved detection approachs. While traditional smoke sensors cover large areas, video/image surveillance systems offer a valuable solution for identifying smoke and flames from a distance. Recent advancements have led to the development of various techniques aimed at enhancing fire detection (Özel, Alam & Khan, 2024). As highlighted in Shamta & Demir (2024), the advancement of drone applications in firefighting has largely centered around the remote sensing of forest fires. Aerial monitoring of these fires is both costly and carries considerable risks, particularly in the context of uncontrolled wildfires. Islam & Hu (2024) propose an autonomous system for forest fire monitoring designed to quickly track specific hot spots. They develop an algorithm to direct drones toward these hot spots, validated through a realistic simulation of forest fire progression. Similarly, Beachly et al. (2018) discuss aerial tasks such as prescribed fire lighting. However, the practical implementation of these tasks is still limited by logistical challenges, particularly in transporting large quantities of water and fire retardant. Kasyap et al. (2022) developed a framework that integrates mixed learning techniques (including the YOLO deep network and Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) technology) to effectively control a Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV)-based fire detection system. This system can fly over burned areas and provide precise and reliable information. Ren et al. (2024) also proposed a real-time forest fire monitoring system that employs UAVs and remote sensing technologies. The drone is equipped with sensors, a mini processor, and a camera, allowing it to process data and images on-board from various sensors.

According to Ma et al. (2018), using UAVs for fire monitoring and detection in quasi-operational field trials proves more effective and safer than risking human lives. Given the complex and unstructured nature of forest fires, UAVs are capable of collecting extensive datasets. To analyze this data effectively, several machine learning techniques have been proposed. One such approach involves integrating color, motion, and shape features with machine learning algorithms for fire detection (Harjoko et al., 2022; Sudhakar et al., 2020). These methods take into account fire characteristics beyond just color, such as irregular shapes and consistent movements in specific areas. Alternatively, deep learning methods have been suggested to classify features like fire, no-fire, smoke, flame, and more (Khan et al., 2022a; Zhou et al., 2024; Choutri et al., 2023). For example, Khan et al. (2022a) introduce a forest fire detection system that focuses on accurately classifying fire versus non-fire images. They created a diverse dataset called Deep-Fire and leveraged Visual Geometry Group (VGG)-19 transfer learning, which demonstrated improved prediction accuracy compared to various other machine learning method. Choutri et al. (2023) investigate the use of YOLO models (versions 4, 5, 8, and Neural Architecture Search (NAS)) to detect fire, no fire, and smoke. Additionally, the authors discuss the fire’s localization using a stereo vision method.

Bonding boxes for object detection

Object detection plays a pivotal role in computer vision systems, with applications spanning autonomous driving, medical imaging, retail, security, facial recognition, robotics, and beyond. Modern approaches predominantly rely on neural network-based models to accurately locate and classify objects within predefined categories. While real-time inference is often a priority, there are scenarios where the primary focus is on enhancing detection accuracy. In such cases, employing ensembles of models has proven to be effective in achieving superior results. Authors in Solovyev, Wang & Gabruseva (2021) introduce an innovative technique for merging predictions from multiple object detection models: the WBF method. The approach leverages the confidence scores associated with each proposed bounding box to generate averaged boxes, resulting in a more accurate and reliable detection outcome. Qian & Lin (2022) introduce an innovative algorithm utilizing weighted fusion techniques to detect forest fire sources across diverse scenarios. Yolov5 and EfficientDet, two separate weakly supervised models, are combined in the methodology. The method handles datasets efficiently since training and prediction activities are carried out in tandem. The combination of these models produces an optimum fusion frame by processing prediction results using the WBF technique. An object detection model that carries out optimized coefficient-weighted ensemble operations on the outputs of three different object detection models—all trained on the same dataset—is presented in Körez et al. (2020). The proposed model is engineered to generate a more accurate and reliable output by applying an optimized coefficient-weighted ensemble to the results of multiple object detection methods. Li et al. (2022) introduce an innovative adaptive label assignment strategy called Dual Weighting (DW) to enhance the accuracy of dense object detectors. Unlike traditional dense detectors that rely on fixed, coupled weighting, DW breaks this convention by dynamically assigning separate positive and negative weights to each anchor. This is achieved through the estimation of consistency and inconsistency metrics from multiple perspectives, allowing for more precise and effective training of dense object detection models.

Data fusion

Data fusion has made significant strides in advancing early wildfire detection methods. By integrating data from multiple sources, such as thermal sensors, UAV cameras, weather data, and satellite imagery, it becomes possible to enhance the accuracy and speed of wildfire detection and response efforts. This approach allows for a more comprehensive understanding of the fire’s behavior and location, enabling authorities to take proactive measures to mitigate its impact. In Zhao et al. (2014), proposed an adaptive weighted fusion algorithm based on Dempster–Shafer theory of evidence for early wildfires warning. Environmental data, including temperature, infrared temperature sensor data, and smoke data, they were subsequently homogenized and fused to derive a comprehensive assessment of fire incident. In Oliveira et al. (2022), a data fusion based decision support system for forest fire prevention and management has been proposed. This system incorporates a flexible Internet of Things (IoT) multisensor node equipped with temperature and humidity sensors, Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) receiver, Carbon Monoxide (CO) and Oxygen (O2) sensors and Infrared (IR) sensors for measuring and mapping the surrounding temperature. The collected data enable the identification of the hot spots and the generation of precise wildfire trajectory predictions. In their study, Benzekri et al. (2020) employed a sensor fusion approach where a wireless sensor network was used to measure various parameters, such as temperature and CO levels. Subsequently, deep learning algorithms were applied to process the acquired data and determine the presence of a forest fire. In Rizogiannis et al. (2017), a decision level fusion approach based on Dempster–Shafer theory has been introduced for early fire detection. Data from meteorological and atmospheric sensors were combined with data from UAV infrared cameras and some other ancillary sources in order to generate early warning alerts and notifications. In El Abbassi, Jilbab & Bourouho (2020), a reliable method for rapid wildfire detection and fire spread estimation has been proposed, the approach is based on the processing of multi-sensor data fusion and decision-making. Temperature, humidity, and smoke data are collected, processed and fused using K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) classifier and the fuzzy inference. In Kim & Lee (2021), a Bayesian network-based information fusion, combined with deep neural network approach was proposed for robust fire detection. Various environmental data from different sensors were combined with visual data from video sequences using simple Bayesian network. In Soderlund & Kumar (2023), an approach employing data fusion for estimating the real-time spread of wildfires has been proposed. Dempster–Shafer theory was applied to combine data coming from static temperature sensors embedded on the surface, and data collected from mobile vision sensors housed on unmanned aerial vehicles UAVs.

Comparison with related methods

Several post-processing strategies have been proposed in the literature to address the issue of overlapping bounding boxes in object detection. Among them, Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS) (Ren et al., 2017; Redmon & Farhadi, 2018) remains the most widely adopted due to its simplicity and computational efficiency. NMS discards boxes with lower confidence scores when they overlap significantly with a higher-scoring box. Although effective in many scenarios, prior studies (Bodla et al., 2017; Alabi et al., 2019) have reported that NMS often suppresses true positives in dense scenes, such as wildfire smoke plumes or clustered objects, leading to reduced recall.

Weighted Boxes Fusion (WBF) (Solovyev, Wang & Gabruseva, 2021) has been introduced as an alternative that aims to overcome some of the limitations of NMS. Instead of discarding boxes, WBF merges them by computing a weighted average of their coordinates, where weights are proportional to the confidence scores. This approach can improve localization accuracy and preserve more potential detections, as demonstrated in applications like multi-model ensembling for object detection (Solovyev, Wang & Gabruseva, 2021; Bochkovskiy, Wang & Liao, 2020). Nevertheless, WBF employs a deterministic averaging process and does not explicitly account for prediction uncertainty, making it less robust when the input boxes contain contradictory or ambiguous information.

The proposed Dempster–Shafer Weighted Boxes Fusion (DS-WBF) builds upon the strengths of WBF while addressing its key limitation. By incorporating Dempster–Shafer theory (Shafer, 2020), the method provides a probabilistic reasoning framework that explicitly models uncertainty and manages conflicting evidence between bounding boxes. Unlike NMS and WBF, which primarily rely on geometric overlap and score heuristics, DS-WBF leverages belief functions to assign and combine degrees of support for different hypotheses (e.g., presence of fire), enabling more informed fusion decisions. This makes DS-WBF particularly advantageous in challenging conditions frequently reported in recent wildfire detection studies (Vasconcelos et al., 2024; Zheng et al., 2023), where visual evidence can be incomplete, noisy, or partially occluded.

In summary, while NMS is efficient and WBF improves localization through weighted averaging, the proposed DS-WBF uniquely combines geometric information, confidence weighting, and uncertainty reasoning, offering a more robust solution for post-processing in object detection pipelines.

Background on Dempster–Shafer theory

The Theory of Belief, which is frequently employed in data fusion, is a formal framework for modeling, computation, and reasoning under uncertainty and imprecision. It is also referred to as evidence theory or Dempster–Shafer theory. First initially suggested as a generalization of Bayesian inference by Dempster (1967), it was later developed into a comprehensive framework for uncertain reasoning by Shafer (1976), a student of Dempster’s, in 1976. In contrast to probability theory, Dempster–Shafer theory (DST) does not require prior information in order to combine pieces of evidence. It permits the allocation of probability mass not just to mutually exclusive singletons but also to sets or intervals. Given to its adaptability and efficiency in managing ambiguity, DST has been widely utilized in numerous data fusion scenarios (Wang et al., 2024b; Bezerra et al., 2021).

Basic definitions

Frame of discernment

Denoted by , it represents a finite, nonempty set of mutually exclusive and exhaustive hypotheses, and is defined as follows:

(1)

The power set of , denoted by , is a set of all the possible combinations of all the elements in . For all , it is defined as:

(2)

Basic probability assignment (BPA) or mass function

It quantifies the degree to which evidence supports a hypothesis by assigning probabilities to various subsets. Within a frame of discernment, the mass function of a subset, denoted by m, is defined as:

(3)

Satisfying the following conditions:

(4)

A is called a focal element of evidence.

Evidence combination rule

In evidence theory, two Basic Probability Assignments (BPAs), and , derived from two independent sources within the same frame of discernment, can be combined using Dempster’s combination rule. This rule calculates the orthogonal sum, denoted by , as follows:

(5)

(6)

The conflict coefficient, denoted as , is used to measure the degree of conflict between two bodies of evidence and is constrained within the range [0, 1].

When , it indicates that the sources are consistent and in complete agreement, whereas implies that the sources are in a state of absolute conflict.

Dempster’s combination rule satisfies both commutativity and associativity properties as follows:

(7)

Thus, this rule can be extended to combine N bodies of evidence.

However, it is crucial to note that Dempster’s combination rule is effective only when the pieces of evidence are consistent. When sources are contradictory, it can yield unreasonable results. To address this issue, various alternatives and updated combination rules have been proposed in the literature. This work will employ the weighted evidence combination approach proposed in Hamda, Hadjali & Lagha (2022).

Materials and Methods

System development process

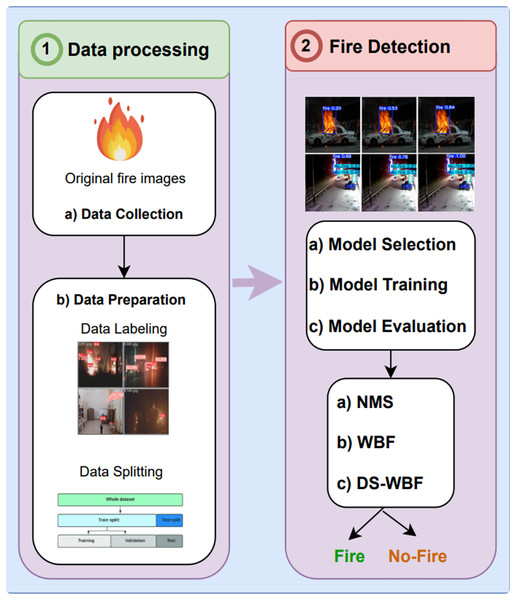

In this article, we proposed a fire detection system for earlier fire detection using computer vision. Figure 1 presents a comprehensive overview of the fire detection system development process using fire imagery, divided into two primary stages: data processing and fire detection. In the data processing stage, the process begins with the data collection step, where original fire images are gathered, serving as the foundational input for model training. Following this, the data preparation phase involves meticulous labeling of these images to annotate fire regions accurately. The data is then methodically split into training, validation, and testing sets, ensuring that the model training process is well-structured and reliable.

Figure 1: Fire detection system development process.

Moving to the fire detection stage, the process is further refined through model selection, training, and evaluation. In this phase, different models are selected, trained, and rigorously evaluated based on their performance in detecting fires. The detection approachs employed include Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS), Weighted Bounding Box Fusion (WBF), and an advanced approach known as Dempster–Shafer Weighted Bounding Box Fusion (DS-WBF). These approachs are crucial in refining detection outcomes, categorizing image regions as either Fire or No-Fire. This systematic approach highlights the importance of integrating advanced fusion techniques to enhance detection accuracy and reliability.

Data

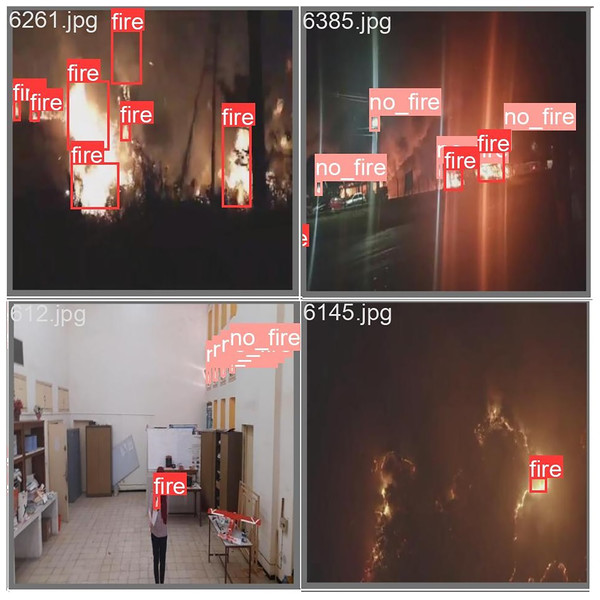

Large and high-quality datasets are essential to the effectiveness of Yolo-based forest fire detection systems. A high-quality dataset enables deep learning models to capture a wide range of features, leading to better generalization capabilities. In our study, we curated an extensive dataset comprising over 12,000 images from various public fire datasets. This dataset features fire images captured under varying conditions and equipment setups. Representative examples from this dataset are presented in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Image labeling examples.

Before deploying the dataset, preprocessing steps were undertaken to ensure both the relevance and quality of the aerial images for our study. Initially, images that lacked visible fire or where the fire was indistinct were removed. The resulting dataset comprised 12,000 images drawn from state-of-the-art public fire datasets—BowFire (Barros, Silva & Santos, 2014), FiSmo (Dimitropoulos, Barmpoutis & Grammalidis, 2015), and Flame (Habiboglu, Gunay & Cetin, 2011)—as well as newly acquired images. These cover a diverse range of scenes, including urban areas, forested regions, indoor settings, and aerial perspectives, under varying lighting and weather conditions. Each image was meticulously labeled into two categories: Fire and No-fire. All images were then uniformly resized to pixels to standardize the input dimensions for the model. Manual labeling was performed to generate precise ground truth data, which includes both image filenames and their associated bounding box coordinates. This preprocessing pipeline was essential for ensuring dataset consistency and suitability for effective training.

The dataset needed to be divided into separate subsets in order to be ready for training machine learning models. To ensure a reliable assessment of the model’s performance, the dataset was split into an 80% training set and a 20% testing set. Data augmentation is another often used preprocessing approach that creates copies of the original dataset by applying affine changes, rotations, and scaling. By using this technique, the neural network is exposed to a wider variety of visual patterns and the dataset’s diversity is increased. In doing so, it improves the model’s capacity to identify objects in a variety of positions and forms, which in turn raises the accuracy of detection.

Yolo models

In the field of computer vision, You Only Look Once (YOLO) is a cutting-edge, real-time object recognition method that has received a lot of popularity. YOLO reframes object identification as a single regression issue, directly predicting bounding boxes and class probabilities from entire images in a single evaluation, in contrast to standard detection systems that apply a classifier to an image at several locations and scales. This approach not only improves detection speed but also enhances accuracy by leveraging global context (Jiang et al., 2022). For this article, three YOLO models: YOLOv3, YOLOv5, and YOLOv9 are used, each offer unique advantages for object detection tasks particularly in the context of fire detection.

YOLOv3, introduced in 2018, marked a significant improvement over its predecessors with a deeper architecture using Darknet-53 as its backbone. Its multi-scale detection approach makes it effective for identifying objects of different sizes, a critical feature in detecting fire and smoke. While YOLOv3 is known for its balance between speed and accuracy, it may lag behind more recent versions in terms of precision and efficiency, especially in complex environments (Jiao et al., 2019).

YOLOv5, although an unofficial continuation of the YOLO series, quickly gained popularity due to its modern design and user-friendly implementation. It introduced several key enhancements, including automated anchor box learning and better data augmentation techniques, making it faster and more accurate than YOLOv3. YOLOv5’s lightweight, modular design allows it to handle large-scale datasets and complex environments effectively, making it ideal for real-time fire detection. However, while it offers significant improvements, it may not fully utilize the latest deep learning advancements needed for the most complex scenarios (Jocher et al., 2021).

YOLOv9 represents the cutting-edge of the YOLO family, incorporating the latest techniques in feature extraction and model optimization. It aims to push the boundaries of detection accuracy, especially in challenging tasks where objects are small or overlapping. YOLOv9 excels in detecting and classifying objects in complex environments, making it well-suited for dynamic fire detection scenarios. However, its advanced capabilities require more computational resources, which might limit its accessibility for applications with limited hardware (Wang, Yeh & Liao, 2024a).

In comparing these models, the choice often depends on the specific application needs. YOLOv3 provides a solid foundation for general-purpose detection, but may struggle in more complex tasks requiring high speed and precision. YOLOv5 offers a balanced approach, making it attractive for real-time fire detection with its efficiency and ease of use. YOLOv9, while offering the highest performance, is best suited for environments with abundant computational resources and where cutting-edge accuracy is crucial. The different Yolo models architectures used for this article are desicpated in Table 1.

| Feature | YOLOv3-m | YOLOv5-m | YOLOv9-m |

|---|---|---|---|

| Backbone | Darknet-53 | CSP-Darknet53 | CSP-DarknetX |

| Neck | FPN | PANet | PANet++ |

| Head | YOLOv3 Head | YOLOv5 Head | YOLOv9 Head |

| Input size | 614 × 614 | 640 × 640 | 640 × 640 |

| Number of parameters | 61.5 M | 7.5 M | 10.2 M |

| Floating Point Operations (FLOPs) | 140 GFLOPs | 16.4 GFLOPs | 18.9 GFLOPs |

| Detection layers | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| Anchor boxes | 9 | Auto-learned | Auto-learned |

| Activation function | Leaky ReLU | SiLU (Swish) | SiLU (Swish) |

| Normalization | BatchNorm | BatchNorm | GroupNorm |

| Speed (FPS) | 30 | 140 | 130 |

Training platform

For this study, we utilized Google Colab as our primary computational environment, chosen for its cost-effectiveness, accessibility, and the advanced hardware options it offers for machine learning tasks. Google Colab provides a default setup featuring an Intel Xeon CPU with 2 virtual CPUs (vCPUs) and 13 GB of RAM, which is sufficient for many deep learning experiments. Additionally, Colab offers access to a NVIDIA Tesla K80 GPU with 12 GB of VRAM, enabling efficient training of complex neural networks, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs).

The choice of Colab was informed by previous experiences with machine learning and artificial intelligence systems, where managing dependencies can often be challenging. Colab’s pre-configured environment alleviates much of this complexity, allowing researchers to focus on model development rather than environment setup. The ability to easily switch between CPU and GPU, reset the environment, and experiment with different configurations without the need for extensive package management makes Colab an ideal platform for rapid testing and prototyping in machine learning research. This flexibility is especially valuable in projects that require extensive experimentation and iterative development.

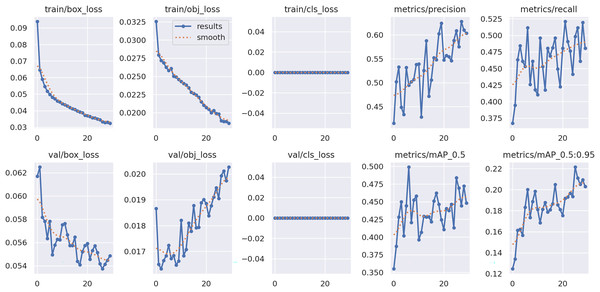

The training and validation curves in Fig. 3 confirm that the model was properly trained and converged in a stable manner. Both the training and validation box losses (train/box_loss and val/box_loss) decrease steadily across epochs, indicating continuous improvement in bounding box localization. The objectness losses (train/obj_loss and val/obj_loss) follow a similar downward trend, demonstrating the model’s increasing ability to distinguish fire-related regions from the background. Minor oscillations observed in the early epochs are typical in object detection training, arising from the adaptive balance between localization and classification objectives, and they gradually diminish toward convergence. The classification losses remain negligible throughout training, reflecting the well-defined categorical structure (fire, no-fire, smoke) and the adequacy of the dataset. Precision and recall curves exhibit an overall upward trend with higher stability in later epochs, while both Mean Average Precision (mAP)0.5 and mAP0.5:0.95 continue to improve, confirming strong generalization across IoU thresholds.

Figure 3: Training and validation curves for YOLOv5-m model.

Importantly, the proposed Dempster–Shafer Weighted Boxes Fusion (DS-WBF) method remains effective even under slight training instabilities, as it explicitly manages uncertainty and conflicting evidence among detections. This robustness ensures consistent performance and reliable decision fusion, further validating the stability of the proposed approach.

Classification metrics

By averaging the precision-recall curve for every class, the Average Precision (AP) metric is utilized to assess how well a model performs in classification tasks. The confidence score indicates how likely it is that an object will be found in a particular anchor box. The Intersection over Union (IoU), a measure of overlap between predicted and ground truth bounding boxes, is computed. To discriminate between True Positives (TP) and False Positives (FP), an IoU threshold of 0.5 (50%) is used. One of the most important metrics for evaluating a model’s accuracy for a given class is precision, which is the ratio of TP to the sum of TP and FP.

(8)

Recall is defined as the ratio of TP to the sum of TP and FN:

(9)

One important indicator for assessing the effectiveness of object detection models, such the YOLO family, is average precision. The precision-recall curve, which shows the trade-off between precision and recall at different threshold values, is the source of this measure. The model’s accuracy in predicting items in a picture is summarized by AP.

AP 0.5 refers to the Average Precision calculated at a fixed IoU threshold of 0.5. The IoU is defined as the ratio of the area of overlap between the predicted bounding box and the ground truth bounding box to the area of their union, as shown in Eq. (10):

(10)

In this case, if the IoU is greater than or equal to 0.5, the prediction is considered a true positive. The AP at this threshold, denoted as ( ), is calculated as the average precision over all points in the precision-recall curve, as given by Eq. (11):

(11) where N represents the number of points on the precision-recall curve.

is a more comprehensive metric that averages the AP over multiple IoU thresholds, ranging from 0.5 to 0.95 in increments of 0.05. This broader evaluation provides a more rigorous assessment of the model’s performance, as it requires the model to achieve good performance across a spectrum of IoU values. The formula for this metric is shown in Eq. (12):

(12) where denotes each IoU threshold from 0.5 to 0.95.

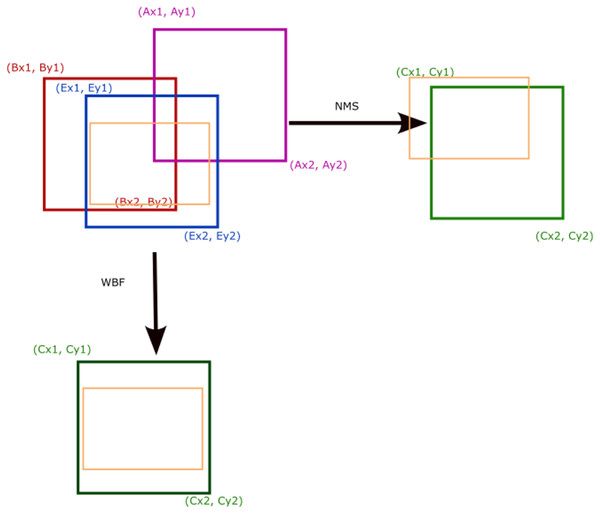

Weighted boxes fusion

The conventional approach for filtering prediction boxes in object detection is NMS. This method relies on a single IoU threshold to filter out redundant boxes (Gong et al., 2021). However, the choice of this threshold can significantly impact the model’s final performance. When multiple objects are positioned closely together, NMS may incorrectly remove one of the objects, as it discards overlapping boxes. This approach, while reducing redundancy, is limited in its ability to generate average local predictions from different models.

As shown in Fig. 4, the Weighted Boxes Fusion (WBF) algorithm (Solovyev, Wang & Gabruseva, 2021), unlike NMS, utilizes the confidence scores of all predicted boxes to generate a fused prediction box. The resulting bbox (bounding box), bboxC, is created by merging bboxA and bboxB, and is calculated using the following equations

(13)

(14)

(15)

(16)

(17)

Figure 4: NMS, WBF and boxes fusion.

Proposed approach

The proposed algorithm integrates Weighted Boxes Fusion (WBF) with Dempster–Shafer theory (DST) to enhance the accuracy of fire and no-fire object detection and classification. It operates through three primary stages, each contributing to the overall effectiveness of the approach.

In the first stage, Weighted Boxes Fusion (WBF) is employed to merge multiple predicted bounding boxes generated by different models. For each pair of bounding boxes, the algorithm calculates the coordinates of a new, fused bounding box, referred to as (bbox_C). This fusion process leverages the confidence scores of the original bounding boxes, computing weighted averages to determine the coordinates of the upper-left and lower-right corners of (bbox_C). The initial confidence score for this fused box is then derived by averaging the confidence scores of the individual bounding boxes.

Following the fusion process, the algorithm applies Dempster–Shafer theory (DST) to refine the confidence score and classify the object. Mass functions m(Fire) and m(No-Fire) are defined for each bounding box, based on the initial confidence scores, representing the degree of belief that the object is Fire or No-Fire. These mass functions are then combined using Dempster’s Rule of Combination, which takes into account potential conflicts between the predictions. The conflict measure K is used to normalize the combined mass functions, leading to updated values mC(Fire) and mC(No-Fire), which reflect the algorithm’s refined belief in the object’s classification.

In the final stage, the algorithm computes the overall confidence score for (bbox_C) by summing the normalized mass functions. The object is then classified as either “Fire” or “No-Fire” based on the higher of the two combined mass functions. Specifically, if mC(Fire) exceeds mC(No-Fire), the object is labeled as “Fire”; otherwise, it is labeled as “No-Fire”.

| Require: Predicted bounding boxes with coordinates and scores si |

| Ensure: Final bounding box bboxC with confidence score Cs and label |

| 1: Step 1: Weighted Boxes Fusion (WBF) |

| 2: for each pair bboxA and bboxB in do |

| 3: Compute fused coordinates: |

| 4: end for |

| 5: Initial confidence score: |

| 6: Step 2: Apply Dempster–Shafer theory (DST) |

| 7: Define mass functions: |

| 8: Combine evidence using Dempster’s rule: |

| 9: Step 3: Final Confidence and Classification |

| 10: Normalize: |

| 11: if then |

| 12: |

| 13: else |

| 14: |

| 15: end if |

| 16: return bboxC, Cs, |

Illustrative numerical example

To clarify the practical differences between Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS), Weighted Box Fusion (WBF), and the proposed Dempster–Shafer Weighted Box Fusion (DS-WBF), we present a simple numerical example. Suppose the detection of the same object by the same YOLO model yields three bounding boxes with slightly different coordinates and confidence scores:

Box A: , confidence = 0.85

Box B: , confidence = 0.80

Box C: , confidence = 0.70.

All three boxes overlap significantly (IoU > 0.6), indicating they likely correspond to the same object.

NMS: NMS retains the box with the highest confidence score (Box A: 0.85) and discards the others, resulting in a single output box with coordinates of Box A and confidence = 0.85.

WBF: WBF merges the boxes by taking a weighted average of their coordinates, where the weights are proportional to the confidence scores:

(similarly for ). The resulting confidence is the weighted sum:

DS-WBF (Proposed): The proposed DS-WBF incorporates Dempster–Shafer theory to manage uncertainty and conflicting evidence. Confidence scores are treated as basic probability assignments (BPAs), and fusion is applied to compute a more robust belief value. Assuming the belief masses after Dempster–Shafer combination are:

The final coordinates are computed similarly to WBF but weighted by the fused belief values rather than raw confidences, leading to improved localization and a higher, more reliable confidence score.

Results and discussions

The results in Table 2 present a comprehensive comparison of three YOLO models (YOLOv3, YOLOv5, and YOLOv9) evaluated with four post-processing methods: standard NMS, Soft-NMS, WBF, and the proposed Dempster–Shafer Weighted Boxes Fusion (DS-WBF). Across all models, DS-WBF consistently yields superior precision, recall, and average precision values, confirming its effectiveness in handling overlapping detections and uncertainty during fusion.

| Model | Method | Precision | Recall | AP0.5 | AP0.5–0.95 | Postproc time (ms)/FPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv3 | NMS | 0.699 | 0.732 | 0.759 | 0.370 | 0.7/72.1 |

| Soft-NMS | 0.713 | 0.742 | 0.766 | 0.374 | 0.9/70.8 | |

| WBF | 0.726 | 0.747 | 0.770 | 0.374 | 3.5/65.4 | |

| DS-WBF | 0.728 | 0.751 | 0.778 | 0.383 | 4.2/63.7 | |

| YOLOv5 | NMS | 0.804 | 0.853 | 0.854 | 0.518 | 0.8/76.9 |

| Soft-NMS | 0.809 | 0.857 | 0.860 | 0.520 | 1.0/75.1 | |

| WBF | 0.810 | 0.855 | 0.861 | 0.522 | 4.5/63.8 | |

| DS-WBF | 0.814 | 0.863 | 0.875 | 0.542 | 6.8/58.3 | |

| YOLOv9 | NMS | 0.769 | 0.781 | 0.780 | 0.486 | 0.7/73.5 |

| Soft-NMS | 0.772 | 0.786 | 0.791 | 0.489 | 0.9/71.2 | |

| WBF | 0.774 | 0.785 | 0.792 | 0.491 | 4.1/64.2 | |

| DS-WBF | 0.778 | 0.794 | 0.827 | 0.502 | 6.5/59.0 |

Among the tested models, YOLOv5 again demonstrates the highest overall accuracy, achieving the best AP0.5 and AP0.5:0.95 scores when paired with DS-WBF, which indicates its strong capacity for discriminating fire, smoke, and non-fire regions across different IoU thresholds. YOLOv9 also benefits from DS-WBF, showing notable gains in AP0.5:0.95, though YOLOv5 remains the most balanced and robust configuration. In terms of computational efficiency, Soft-NMS provides a small yet consistent performance gain over standard NMS with only a marginal increase in processing time (approximately 0.2–0.3 ms), preserving real-time inference capability. Conversely, WBF and DS-WBF introduce higher computational costs, with post-processing times up to 6–7 ms per image, leading to a moderate reduction in inference speed (about 15–20% in FPS). Nevertheless, the improvement in detection reliability and precision justifies this trade-off, particularly for safety-critical wildfire monitoring where accurate early detection is prioritized over minimal latency.

In addition to the standard detection metrics, we evaluated the False Detection Rate (FDR) to directly quantify the system’s robustness against false alarms. The FDR is defined as:

Lower FDR values indicate fewer false alarms, which is critical for reliable fire detection in real-world scenarios.

As shown in Table 3, the proposed DS-WBF method consistently achieves the lowest False Detection Rate (FDR) across all evaluated YOLO models, with reductions of up to 28% compared to standard NMS and up to 16% relative to conventional WBF. These reductions highlight DS-WBF’s enhanced capability to suppress false alarms in visually challenging scenes, such as those involving dense smoke, low contrast, or background reflections. For instance, YOLOv5 combined with DS-WBF achieved an FDR of 0.089, corresponding to a 28% decrease compared to NMS (0.118) and a 16% improvement over WBF (0.103).

| Model | NMS FDR | Soft-NMS FDR | WBF FDR | DS-WBF FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv3 | 0.124 | 0.118 | 0.110 | 0.096 |

| YOLOv5 | 0.118 | 0.114 | 0.103 | 0.089 |

| YOLOv9 | 0.121 | 0.116 | 0.107 | 0.092 |

This quantitative evidence directly substantiates the claim made in the “Abstract” and “Results and Discussion” regarding the method’s robustness in complex environments and its effectiveness in early-stage fire detection. By integrating Dempster–Shafer theory, DS-WBF effectively manages uncertainty and conflicting detections, thereby improving not only overall accuracy but also operational reliability—an essential requirement for real-time wildfire monitoring and early warning systems.

Figure 5 demonstrates the comparative performance of the three methods in detecting fire and no-fire scenarios across various images using Yolov5 model. The results are visually represented, showing how each method handles overlapping bounding boxes and assigns confidence scores.

Figure 5: Examples of fire detection: the images on the right are the source images, and those on the left are the results obtained using the YOLOv5 model: (A) NMS, (B) WBF, (C) DS-WBF.

In the upper row, fire detection is consistently strong in all images, with confidence scores progressively increasing from left to right. DS-WBF clearly provides the most accurate boundary box with the highest confidence score, indicating superior precision in identifying and localizing the fire. WBF follows, showing a reasonable level of accuracy, while traditional NMS, although effective, delivers the lowest confidence scores and less precise localization. The middle row presents a more complex scene where both fire and no-fire elements are present. Here, DS-WBF again excels, producing higher confidence scores for both fire and no-fire detections, ensuring that the bounding boxes are accurately placed around the correct objects. WBF performs well, though slightly less precisely than DS-WBF. Traditional NMS shows a noticeable drop in confidence and accuracy, particularly in this more challenging scenario. In the bottom row, which depicts a no-fire scenario, DS-WBF once more stands out, demonstrating the highest accuracy in identifying the absence of fire, with confidence scores reflecting its reliability. WBF follows closely behind, also showing strong performance in correctly classifying the scene. Traditional NMS, however, lags, showing lower confidence in correctly identifying the no-fire situation.

When compared with prior works, our method stands out for its ability to combine high-precision fusion with uncertainty reasoning, without requiring retraining of the base detectors. Traditional sensor-based fusion approaches (e.g., IoT smoke sensors) lack spatial localization capabilities, while most image-based fusion methods rely on simpler confidence aggregation schemes, such as NMS or plain averaging in WBF. The proposed DS-WBF differs qualitatively by introducing an evidence-theoretic reasoning stage, which accounts for both the confidence and the level of agreement among detectors, thus leading to more reliable fused outputs. Quantitatively, the performance gains reported here exceed those in related multi-detector fusion studies, where improvements are typically in the range of 1–2% mAP.

Despite these strengths, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the method’s reliance on multiple detectors inherently increases inference time and computational resource demands, which may be a constraint for real-time deployment on edge devices with limited processing power. Second, the current experiments were conducted on aerial wildfire imagery, and although we expect the DS-WBF mechanism to generalize to other object detection tasks, further validation on unrelated domains (e.g., traffic monitoring, medical imaging) is necessary. Finally, while the comparative results against WBF and NMS serve as an implicit ablation study, a dedicated, fine-grained ablation analysis would more explicitly quantify the impact of the DST component. Addressing these points will be part of our future research roadmap.

Conclusion

This article presented an advanced forest fire detection method that improves detection accuracy by addressing the inherent uncertainty in distinguishing true fires from false positives. Our novel weighted bounding box fusion approach, grounded in Dempster–Shafer theory, effectively resolves conflicts between fire and non-fire classifications within a single YOLO detector’s outputs. The proposed confidence-aware fusion mechanism prioritizes reliable detections while systematically handling ambiguous cases where fire-like features might be mistaken for actual fires. Extensive experiments conducted on a dataset of fire images demonstrate that our proposed method outperforms traditional detection methods under different models, particularly in complex environments where early detection is critical. The results indicate a marked improvement in detection performance, which could play a crucial role in enhancing forest fire monitoring systems, potentially leading to faster response times and reduced damage from fires. Future work could explore the integration of this methodology with real-time data streams from UAVs or satellite imagery, as well as its application to other types of natural disaster detection. Overall, the proposed approach presents a promising advancement in the field of fire detection, with significant implications for environmental protection and disaster management.