Refining small object detection in aerial images with PF-DETR: a progressive fusion approach

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Davide Chicco

- Subject Areas

- Artificial Intelligence, Computer Vision, Data Mining and Machine Learning

- Keywords

- Small object detection, Spatial-frequency modeling, Multi-scale feature fusion, RT-DETR, Aerial images

- Copyright

- © 2026 Liu et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2026. Refining small object detection in aerial images with PF-DETR: a progressive fusion approach. PeerJ Computer Science 12:e3470 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3470

Abstract

Small object detection remains a challenging task due to limited pixel resolution, complex backgrounds, and high sensitivity to bounding box variations in aerial images. Although Detection Transformer (DETR)-based methods have made progress, they still face significant limitations in small object detection, primarily due to their reliance on global features, which fail to capture fine-grained details and are sensitive to background noise and bounding box variations. This study proposes Progressive Fusion (PF)-DETR, a model specifically designed to refine small object detection through progressive feature fusion techniques. Central to our approach is the Cross-Scale Feature Fusion with S2 (S2-CCFF) module, which integrates multi-level features with an S2 layer to preserve small object details. Coupled with SPace-to-Depth convolution (SPDConv) downsampling, this module reduces computational cost while maintaining critical information. Additionally, Cross Stage Partial Omni-Kernel Fusion (CSPOK-Fusion) Module achieves progressive fusion by gradually integrating multi-scale features from local, large, and global branches through successive convolutional layers, effectively refining the feature representation at each stage, mitigating background interference and occlusion effects to enhance cross-scale spatial representation. We further introduce a Parallelized Patch-Aware (PPA) attention module in the Backbone network to prioritize small object features, significantly addressing information loss. Finally, Normalized Wasserstein Distance (NWD) loss function is incorporated to heighten robustness against minor localization errors by aligning bounding box positioning and shape, thus boosting detection accuracy. Experimental results on the VisDrone and NWPU VHR-10 datasets revealed that PF-DETR surpasses existing state-of-the-art methods, establishing its effectiveness and adaptability in complex aerial detection tasks.

Introduction

Aerial object detection plays a crucial role and is widely applied in surveillance, urban planning, and disaster monitoring, where accurate detection of small and distant objects can significantly impact decision-making and resource allocation (Gui et al., 2024). However, due to the wide field of view in aerial images, the size of the resulting images is often larger than typical images, leading to a significant imbalance between foreground and background information. Many objects appear as small targets, characterized by limited pixel information, small object area, indistinct texture features, and low contrast with the background. Traditional detection methods struggle with these challenges, often facing limitations such as insufficient detection accuracy and loss of fine details (Liu et al., 2024c).

As deep learning and convolutional neural networks (CNN) continue to evolve rapidly in recent years, object detection models utilizing the Transformer (Vaswani, 2017) architecture, such as Detection Transformer (DETR) (Carion et al., 2020), have made remarkable progress in detection tasks. By transforming object detection into an end-to-end sequence modeling problem, DETR eliminates the need for region proposals used in traditional detectors. Compared to Regions with Convolutional Neural Networks (R-CNN) (Girshick, 2015) and You Only Live Once (YOLO) (Redmon, 2016; Redmon & Farhadi, 2018; Bochkovskiy, Wang & Liao, 2020; Wang, Bochkovskiy & Liao, 2023; Wang, Yeh & Liao, 2024; Wang et al., 2024) methods, DETR avoids the complexity of post-processing and hyperparameter tuning by using query vectors as soft anchors instead of predefined anchor boxes for target localization. However, this design results in slow convergence and requires extended training time. To address this, researchers have proposed various improvements, such as Deformable DETR (Zhu et al., 2020), and the introduction of algorithms like Real-Time DEtection TRansformer (RT-DETR) (Zhao et al., 2024) marks a maturation of DETR-based methods. These approaches have improved small object detection by incorporating multi-scale feature extraction modules, contextual information fusion strategies, and advanced bounding box regression mechanisms. Nevertheless, challenges such as complex backgrounds with occlusions, loss of object information, and the low tolerance to bounding box perturbations in aerial images still need to be addressed for small object detection (Miri Rekavandi et al., 2025). As shown in Fig. 1.

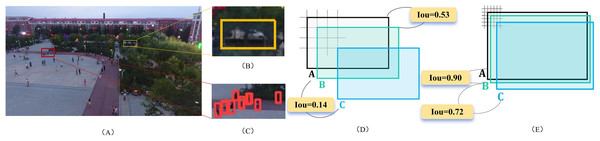

Figure 1: Challenges in small object detection.

(A) Image from the VisDrone dataset; (B) Small object affected by noise; (C) Feature loss during small object detection; (D) Low tolerance to small object bounding box perturbations; (E) Minimal impact of bounding box perturbations on normal objects. VisDrone2019 dataset images attributed to the AISKYEYE team at Lab of Machine Learning and Data Mining, Tianjin University, China.Complex backgrounds and occlusions: Aerial images have a wide perspective and a large number of small targets present. For example, Fig. 1A shows a square scene from the VisDrone UAV dataset, containing numerous tiny objects. Additionally, substantial background information, including vegetation and buildings, is present. Figure 1B illustrates small cars obscured by trees. The features of small objects are easily affected by background information or other disturbances, which introduces noise into the learned feature representations. This noise weakens the depiction of small object features and hinders the model’s learning and accurate prediction.

Loss of details regarding small objects: In deep learning algorithms, CNNs typically construct multi-scale feature pyramids, that progressively decrease the spatial resolution of feature maps. While this helps retain most of the critical information, some object information is inevitably lost. For medium and large objects, this loss generally does not significantly affect detection performance, as their features remain prominent. However, for small objects, this loss severely impacts detection (Xiao et al., 2023b). The features of small objects become weak on highly compressed feature maps, and their proximity to each other, as well as potential confusion with the background or other objects, increases detection complexity. As shown in Fig. 1C, it difficult to make accurate predictions from these sparse and incomplete representations.

Low tolerance to bounding box perturbations: Localization is a fundamental aspect of object detection, typically achieved through bounding box regression. Intersection over Union (IoU) is a common metric for evaluating regression performance. Compared to normal objects, small objects are highly sensitive to slight shifts in their bounding boxes. As illustrated in Figs. 1D and 1E, small objects (6 × 6) and normal objects (36 × 36) are shown. Box A indicates the ground truth (GT), whereas boxes B and C illustrate predicted boxes with slight diagonal shifts of 1 pixel and 2 pixels, respectively. The IoU assesses the overlap between the GT box and the predicted boxes. A 1-pixel shift for the small object reduces the IoU to 0.53, while a 2-pixel shift further decreases it to 0.14. In contrast, the IoU for the normal object remains relatively stable, changing from 0.90 to 0.72 under similar perturbations. This demonstrates that small objects exhibit significantly lower tolerance to bounding box regression errors compared to normal objects, complicating the model’s learning in the regression branch.

This article presents Progressive Fusion (PF)-DETR, a model specifically designed for small object detection to tackle these challenges. The model integrates a Cross-Scale Feature Fusion with S2 (S2-CCFF) module, which is composed of Space-to-Dept Convolution (SPDConv) and Cross Stage Partial Omni-Kernel Fusion (CSPOK-Fusion), a Parallelized Patch-Aware (PPA) attention module, and the Normalized Wasserstein Distance (NWD) loss function. Unlike traditional methods, PF-DETR effectively captures small object features, minimizes background noise, enhances cross-scale feature fusion, and lessens the impact of bounding box perturbations, ultimately leading to improved detection accuracy and efficiency. The S2-CCFF and the CSPOK-Fusion modules are innovatively proposed, while the SPDConv, PPA and NWD modules are introduced from existing approaches. The main contributions of this article are as follows:

The S2-CCFF module is proposed, where an S2 layer is added during cross-scale feature fusion to enrich small object information. To mitigate information loss caused by conventional downsampling, spatial downsampling is performed on the S2 layer using SPDConv, preserving key details while reducing computational complexity. Additionally, the CSPOK-Fusion module is designed as a progressive fusion mechanism that progressively integrates multi-scale features across global, local, and large branches. This gradual fusion process helps to effectively combine features at different scales, improving the overall representation by addressing both fine-grained details and larger contextual information.

The PPA module is incorporated into the Backbone network, employing multi-level feature fusion and attention mechanisms to preserve and enhance small object representations. This ensures key information is retained across multiple downsampling stages, effectively mitigating small object information loss and improving subsequent detection accuracy.

To address the low tolerance of bounding box perturbations, we introduce the NWD (Xu et al., 2022) loss function, which better captures differences in the relative position, shape, and size of bounding boxes. It focuses on the relative positional relationships between boxes rather than merely relying on overlap. This approach offers greater tolerance to minor bounding box perturbations.

Portions of this text were previously published as part of a preprint (Liu et al., 2024c). The article is structured as follows: ‘Related Work’ provides an in-depth overview of existing research on small object detection in aerial imagery. ‘Methodologies’ introduces the architecture of the proposed model. In ‘Experiment’, we present ablation studies to evaluate the contribution of each module, alongside comparative experiments and visual performance analyses. Lastly, ‘Conclusion’ concludes the work and discusses potential directions for future research.

Related work

The detection of small objects holds a pivotal position in the field of computer vision, particularly in high-resolution images with complex backgrounds. Small objects occupy fewer pixels, making them more susceptible to background noise and challenging to extract features from. To effectively address these challenges, researchers have proposed various approaches, including improved feature extraction mechanisms, multi-scale feature fusion, and the introduction of novel loss functions. This section reviews mainstream object detection algorithms and the latest advances in small object detection.

Convolutional neural network-based detection methods

Conventional CNN-based detection approaches are broadly categorized into two-stage and one-stage detectors. Two-stage detectors, such as Faster R-CNN (Ren et al., 2016), Mask R-CNN (He et al., 2017), and Cascade R-CNN (Cai & Vasconcelos, 2019), first generate region proposals and then refine them to improve classification accuracy and object localization. For instance, Libra R-CNN (Pang et al., 2019) addresses the imbalance issue in small object detection by refining raw features through non-local blocks, enhancing interaction features. Similarly, Cascade R-CNN (Cai & Vasconcelos, 2019) progressively refines predictions through multi-stage regression, optimizing boundary boxes and class information for small objects. Although these two-stage detectors excel in detection accuracy, they often encounter limitations in terms of speed, training complexity, and optimization overhead, making them less practical for real-time applications.

In contrast, one-stage detectors, including SSD (Liu et al., 2016), RetinaNet (Lin, 2017), and the YOLO series (Redmon, 2016; Redmon & Farhadi, 2018; Bochkovskiy, Wang & Liao, 2020; Wang, Bochkovskiy & Liao, 2023, Wang, Yeh & Liao, 2024; Wang et al., 2024), bypass the region proposal step, enabling simultaneous prediction of object classes and bounding box coordinates within a single network. While one-stage detectors are better suited for speed-critical applications, they often sacrifice accuracy, especially when detecting small objects, as detail loss caused by downsampling remains a persistent issue.

To address these challenges, multi-scale feature fusion techniques have been introduced to improve small object detection. Feature Pyramid Networks (FPN) (Lin et al., 2017), for example, construct a bottom-up feature pyramid that enables the model to fuse multi-scale features, enhancing detection performance across object scales. Path Aggregation Network (PANet) (Liu et al., 2018) builds on FPN by employing fewer convolutional layers in its path-enhancement module to retain more lower-layer information, while also introducing adaptive feature pooling to boost small object detection accuracy. Other methods, such as Neural Architecture Search-Feature Pyramid Network (NAS-FPN) (Ghiasi, Lin & Le, 2019) and Bidirectional Feature Pyramid Network (BiFPN) (Tan, Pang & Le, 2020), focus on optimizing feature fusion and balancing efficiency with accuracy through techniques like reinforcement learning and bidirectional pathways.

Despite these advancements, existing methods often fall short in fully leveraging low-level positional information and capturing fine-grained context interactions, which are crucial for accurately detecting small objects in complex scenarios. For instance, Cross-scale Feature Fusion Pyramid Network (CF2PN) (Huang et al., 2021) addressed inefficiencies in multi-scale object detection for aerial images through multi-level feature fusion, while Augmented Feature Pyramid Network (AugFPN) (Chen et al., 2020) tackled the inconsistency between detailed and semantic information in feature maps by introducing Adaptive Spatial Feature (ASF) for dynamic scale-based feature integration. Adaptive Feature Pyramid Network (AFPN) (Yang et al., 2023) further refined multi-scale feature fusion by progressively merging low- and high-level features to minimize semantic gaps. Similarly, Gong et al. (2021) optimized fusion weights through statistical analysis, significantly enhancing small object detection.

Recent works have explored novel ways to enhance small object detection by improving feature interaction and context representation. Gao et al. (2023) proposed a method to strengthen global semantic information by rotating high-level semantic features and enhancing multi-perspective interactions. Hu et al. (2022) employed adaptive hierarchical upsampling to compensate for low-level features, reducing noise in FPN fusion. DeNoising Feature Pyramid Network (DN-FPN) (Liu et al., 2024b) used contrastive learning to suppress feature noise across scales, while Cross-Layer Feature Pyramid Transformer (CFPT) (Du et al., 2024) introduced a cross-layer channel and spatial attention mechanism to prevent information loss during feature interaction.

Transformer-based detection methods

Recently, Transformer-based detection methods have emerged as a promising approach for object detection due to their ability to model long-range dependencies and enhance feature representation. Vision Transformer (ViT) (Dosovitskiy, 2020) demonstrated its potential across various visual tasks, but its high computational complexity at larger image resolutions limited its practical applicability. To address this, lightweight alternatives such as the Swin Transformer (Liu et al., 2021) introduced local-windowed self-attention with a shifted window strategy, enabling efficient multi-scale feature modeling. These advancements have made Transformer-based models increasingly practical for real-world applications, including autonomous driving and aerial image analysis, where computational efficiency and accuracy are critical.

DETR (Carion et al., 2020) revolutionized object detection by removing anchor boxes and adopting an end-to-end detection pipeline. However, its limited performance on small objects highlighted challenges in handling low-resolution features and insufficient positive sample generation. Building upon DETR, methods like Deformable DETR (Zhu et al., 2020) and RT-DETR (Zhao et al., 2024) introduced sparse attention mechanisms and refined feature extraction modules to improve detection efficiency and accuracy. For instance, RT-DETR showed potential in real-time applications like surveillance systems but still struggled with low contrast and complex backgrounds in aerial images. Oriented Object DEtection with TRansformer (O2DETR) (Ma et al., 2021) addressed multi-scale and rotational object detection challenges, while techniques like Sample Points Refinement (SPR) and Task-decoupled Sample Reweighting (SR) (Huang et al., 2024) further optimized the attention distribution for detecting small, hard-to-identify objects.

Despite these advancements, existing Transformer-based methods (Zhou et al., 2025), still face challenges in small-object detection, particularly in complex scenarios such as aerial imagery where the low contrast between small objects and backgrounds limits performance. Addressing these issues requires innovations in feature refinement and better contextual information extraction, which this study proposes to address. By focusing on improving feature representation and integrating multi-scale contextual features, this work offers a practical and scalable approach to advancing small-object detection, with implications for applications such as disaster monitoring, urban planning, and autonomous navigation. Furthermore, the proposed method provides a framework for future research to explore more efficient and accurate solutions in the field.

Detection methods for small objects in aerial images

Recent works on small object detection have introduced innovative architectures and strategies to address challenges such as low resolution, complex backgrounds, and uneven object distributions. ClusDet (Yang et al., 2019) employs a coarse-to-fine strategy using clustered region proposals and scale estimation, enhancing small object recognition by progressively refining predictions. Density-Map guided object detection Network (DMNet) (Li et al., 2020) simplifies this approach with a density map generation network, streamlining training and improving clustering efficiency.

To improve multi-scale feature representation and inference efficiency, Multi-Proxy Detection Network with Unified Foreground Packing (UFPMP-Det) (Huang, Chen & Huang, 2022) utilizes a feature pyramid with multi-path aggregation and anchor optimization, while Context-Enhanced Adaptive sparse convolutional network (CEASC) (Du et al., 2023) integrates global context features and adaptive multi-layer masking to optimize feature utilization across scales. Similarly, Dynamic Training Sample Selection Network (DTSSNet) (Chen et al., 2024) enhances multi-scale sensitivity by incorporating a tailored block between the backbone and neck, coupled with sample selection mechanisms for small objects.

Several methods have also focused on aerial and high-resolution imagery, where small object detection is particularly challenging. For instance, Drone-YOLO (Zhang, 2023) leverages a three-layer Path Aggregation Feature Pyramid Network (PAFPN) structure and a specialized detection head to significantly improve performance for small targets. Efficient Small Object Detection (ESOD) (Liu et al., 2024f) combines feature-level target searching with image block slicing, reducing computational waste in background regions, and enabling efficient detection in high-resolution images. Feature enhancement, Fusion and Context Aware (FFCA)-YOLO (Zhang et al., 2024) improves detection accuracy by enhancing local sensitivity, multi-scale feature fusion, and spatial context awareness, showing robustness under various simulated degradation conditions.

Other approaches have introduced novel supervision and loss strategies to improve detection precision. For example, Liu (Khalili & Smyth, 2024) introduced explicit supervision for micro-object regions during training, enabling attention maps to suppress background noise and enhance regions containing small objects. You Only Look Clusters (YOLC) (Liu et al., 2024a), addressing uneven object distributions in large-scale images, introduces a Local Scale Module (LSM) to adaptively zoom in on clustered regions for precise detection, while employing Gaussian Wasserstein distance for bounding box regression and deformable convolutions for feature refinement.

Compared to mainstream CNN or Transformer-based detectors, PF-DETR introduces three key components. First, during the fusion stage, it introduces S2 shallow features and controls computational complexity with SPDConv, compensating for the loss of small object information caused by the use of only S3–S5 features in typical FPN or RT-DETR architectures. Second, PPA and CSPOK-Fusion are inserted in parallel between the backbone and fusion nodes, simultaneously activating small object regions and suppressing noise from complex aerial backgrounds, thereby overcoming the limited receptive fields in traditional CNN methods and the global attention dilution in Transformer-based approaches. Third, NWD is used as a replacement for IoU loss, shifting box regression from overlap ratio to distribution distance, significantly mitigating the extreme sensitivity of small objects to pixel-level shifts. Through the combination of shallow feature retention-background suppression-box deviation robustness, PF-DETR systematically addresses the three major issues detail loss, high false positives, and fragile localization—commonly faced by mainstream methods in small object detection in aerial imagery, while maintaining the global modeling capability of Transformers.

Methodologies

This section presents a comprehensive overview of the proposed small object detection framework for aerial images, termed PF-DETR. First, we summarize the methodology and present the overall network architecture. Subsequently, we elaborate on the composition of each module.

Overall architecture

We select RT-DETR as the baseline framework, which is an optimized version of DETR, designed to deliver faster inference speeds and efficient real-time detection capabilities. The YOLO series of detectors, while known for their speed and efficiency, often face limitations in accurately detecting small objects because of their grid-based detection mechanism, which can lead to missed or imprecise localization of small targets. Other detectors widely used in remote sensing tasks, such as anchor-based or CNN-heavy architectures, may achieve good results on medium or large objects but struggle with small objects in cluttered or long-distance scenes due to limited receptive fields and insufficient attention to fine details. In contrast, RT-DETR, with its transformer-based design and stronger capability for global context modeling, is more effective at capturing the subtle features required for small object detection, making it a more suitable and representative baseline for this study. After extracting multi-scale feature maps using a backbone network, RT-DETR utilizes an Efficient Hybrid Encoder to convert multi-scale features into a sequence of image features through Attention-driven Intra-scale Feature Interactions (AIFI) and CNN-based Cross-scale Feature Fusion (CCFF). It then employs uncertainty-minimizing query selection to choose a fixed number of encoder features, which serve as initial object queries for the decoder. The decoder progressively refines these queries with the assistance of auxiliary prediction heads to produce object classifications and bounding boxes.

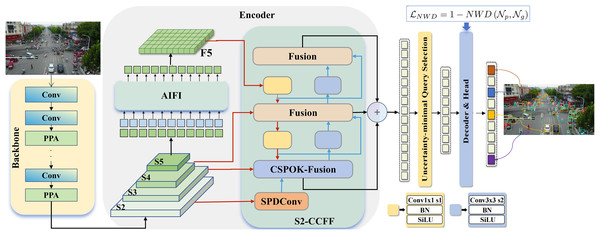

This study proposed the PF-DETR framework for small object detection in aerial imagery, as illustrated in Fig. 2. The framework is specifically designed to enhance the detection of small targets and consists of three core components: the Backbone, Encoder, and Decoder. The Backbone constructs a five-layer feature pyramid using a CNN to extract features at different scales and information levels, represented as S1, S2, S3, S4, S5. To improve the ability to capture information about small objects, we introduce a PPA module within the Backbone to retain fine detail information of small targets.

Figure 2: Overall architecture of PF-DETR: the backbone integrates the PPA module to retain essential information regarding small targets.

S2-CCFF module incorporates the S2 layer, Enriched small target information. During detection, the NWD loss is employed to address challenges associated with bounding box perturbations. VisDrone2019 dataset images attributed to the AISKYEYE team at Lab of Machine Learning and Data Mining, Tianjin University, China.During the feature fusion stage, we proposed the S2-CCFF module, which incorporates the S2 layer for cross-scale feature fusion. This module effectively merges features rich in small object information with the S3, S4, and S5 layers, facilitating the learning of feature representations from global to local, and significantly reducing the impact of noise. After processing through uncertainty-minimizing queries and the Decoder, we utilize the NWD metric in the detection head to assess the loss between the ground truth and the predicted bounding boxes, effectively addressing small object bounding box perturbations and enhancing detection performance for small targets.

S2-CCFF module

Module structure

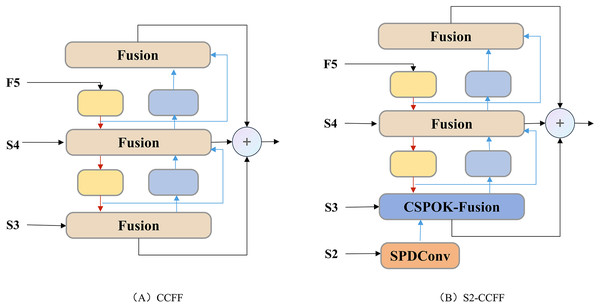

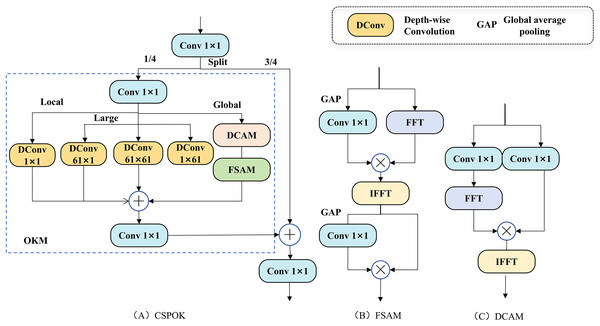

In small object detection tasks, challenges such as high background noise and information loss can significantly hinder the model’s ability to capture target features. In deep learning algorithms, after constructing a multi-scale feature space through the backbone, multi-scale feature fusion is typically performed to capture features at different scales, enhancing detection accuracy. In RT-DETR, the interaction and fusion of cross-scale features continue to rely on the FPN as the optimal choice from a real-time perspective. The CCFF performs PAFPN operations on the S3 to S5 layers, as illustrated in Fig. 3A. The Fusion module within this context is designed in the style of a Cross Stage Partial Block (CSPBlock). The multi-scale pyramid comprises the S1 to S5 layers, corresponding to high, medium, and low-resolution feature maps. Since the resolution of a feature map is inversely related to its receptive field, higher-resolution feature maps (e.g., S1) generally contain more fine-grained spatial information, whereas lower-resolution maps (e.g., S5) possess richer semantic information but less spatial detail. While higher-resolution feature maps like S1 retain more spatial information, their smaller receptive fields result in a lack of contextual information, making it challenging to distinguish small targets from the background or adjacent objects (Xiao et al., 2023a). Conversely, relying solely on the S3, S4, and S5 layers may fail to fully utilize the fine-grained information provided by higher-resolution feature maps (e.g., S2), which is crucial for accurately detecting small targets. The common approach is to incorporate higher resolution feature layers (S2) to better preserve the spatial details of small targets and improve detection accuracy. However, this can introduce several issues, including increased computational and longer post-processing times.

Figure 3: Comparison between CCFF and S2-CCFF.

(A) represents the CCFF structure utilized in RT-DETR, while (B) illustrates the proposed S2-CCFF in this work.To address these challenges in aerial imagery, we propose the S2-CCFF module based on the CCFF module, as shown in Fig. 3B. It is located in the Encoder. This module integrates the S2 layer into cross-scale feature fusion to improve the retention and enhancement of small target feature representations, with S2, S3, S4, and S5 corresponding to resolutions of 1/4, 1/8, 1/16, and 1/32 of the original image, respectively. To mitigate the increased computational burden and time consumption associated with adding the S2 layer, we first process the S2 feature layer using SPDConv (Sunkara & Luo, 2022), applying spatial downsampling to reduce the resolution of the S2 layer. This involves rearranging pixels to adjust the dimensions and structure of the feature map, allowing us to retain essential detail without directly handling high-resolution feature maps. This effectively resolves issues related to excessive computational demands and extended post-processing times after adding the S2 detection layer. Subsequently, the feature rich in small object information is fused with the S3 layer using the CSPOK-Fusion module. The CSPOK-Fusion module integrates concepts from CSP and Omni-Kernel (Cui, Ren & Knoll, 2024), consisting of global, large, and local branches to effectively learn feature representations from global to local scales. This approach significantly suppresses background noise, enhances the detection performance of small targets, and reduces computational complexity.

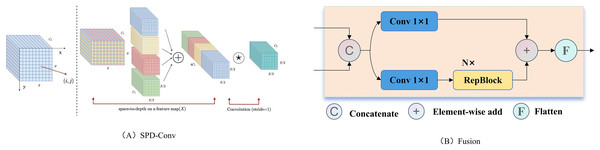

The S2-CCFF mainly comprises the SPDConv, Fusion, and CSPOK-Fusion modules. In Fig. 3B, red arrows indicate downsampling, and blue arrows indicate upsampling. The SPDConv structure is depicted in Fig. 4A. Its core concept is to introduce a novel CNN building block that replaces the conventional row-wise convolution and pooling layers found in CNN architectures. By combining spatial-to-depth (SPD) layers with non-row-wise convolution layers, SPDConv aims to enhance performance in detecting low-resolution images and small object targets. It effectively preserves fine-grained information, addressing the information loss problem associated with traditional row-wise convolution and pooling layers, thereby significantly improving performance in object detection and image classification tasks.

Figure 4: Submodule structures.

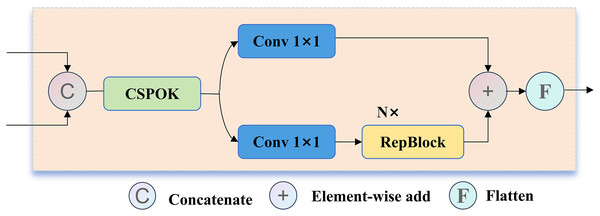

(A) SPD-Conv, (B) Fusion module.The Fusion block, illustrated in Fig. 4B, first receives features from different layers or scales and concatenates these features along the channel dimension using a concat operation. Subsequently, the features pass through two 1 × 1 convolutional layers. One branch enters the RepBlock module, where it undergoes stacking through N RepBlock units. The RepBlock is a block that incorporates various convolutional and activation operations, aimed at further enhancing the representational capability of the features. It provides more profound feature extraction across multiple levels of features. Next, the features processed by the RepBlock are added element-wise to another set of features that have not undergone RepBlock processing. This step functions as a skip connection, ensuring that features from different levels can be directly fused, thereby preserving the detailed information of shallow features while integrating the contextual information of deep features. Finally, the fused features are flattened in preparation for subsequent classification or regression tasks. This Fusion block effectively merges information across multiple feature levels through concatenation, convolution operations, and residual connections, thereby strengthening the network’s ability to represent target features in small object detection tasks while reducing the interference from redundant features.

The S2-CCFF module effectively addresses the challenges of significant noise interference and information loss in small object detection through its design, which incorporates adaptive convolution and multi-scale feature fusion. Compared to traditional feature fusion methods, the S2-CCFF module better retains and enhances the feature representation of small objects, enabling the detector to achieve higher accuracy and robustness in complex backgrounds and noisy environments.

CSPOK-fusion module

In the Fusion architecture, the cross-scale feature fusion is highly effective for integrating features from the S3 to S5 layers. However, when directly fusing S2 with S3 to S5, significant differences between shallow and deep features may lead to feature conflicts. Specifically, the low-level information from the S2 layer can obscure the high-level semantic features of the S3 to S5 layers, adversely affecting the overall performance of the network. Traditional fusion structures may not adequately address these disparities, which can diminish the effectiveness of the fusion process. Therefore, this study proposes the CSPOK-Fusion module, which incorporates the CSPOK module into the original Fusion architecture. Figure 5 illustrates the CSPOK-Fusion structure, which combines CSPOK with multi-branch convolution operations and RepBlock mechanisms through cross-channel fusion. The CSPOK-Fusion module enhances useful shallow detail information while suppressing redundant shallow information, thereby preventing shallow features from interfering with deep semantic features.

Figure 5: CSPOK-fusion structure.

This structure is primarily used for the fusion of features from the S2 and S3 layers. Compared to the Fusion module, the CSPOK module has been added to enhance the integration process.The CSPOK Block improves upon the Omni-Kernel Module (OKM) (Cui, Ren & Knoll, 2024) using the Cross Stage Partial (CSP) concept, as illustrated in Fig. 6A. Initially, the input feature map X undergoes preliminary feature extraction through a convolutional layer. The CSP structure subsequently divides the input feature map into two branches, with the feature map split into two parts of and . The left branch , corresponding to the feature map, performs OKM operations, which involves channel compression via a convolution, followed by feature extraction through three levels: local branch, large branch, and global branch. In the large branch, the convolution kernel size of 63 is replaced with 61. Meanwhile, the right branch , representing the portion, directly concatenates with the feature map processed by OKM and fuses the two through a convolutional layer. This structure enhances the network’s learning capacity without increasing computational overhead. It retains the robust contextual processing ability of the OKM module while ensuring that the other branch sufficiently preserves small target information, thereby improving the accuracy and speed of object detection.

Figure 6: CSPOK-fusion structure.

This structure is primarily used for the fusion of features from the S2 and S3 layers. Compared to the fusion module, the CSPOK module has been added to enhance the integration process.

-

(1)

Local branch: performs 1 1 depth convolution to extract local features. (1)

where represents the output of the local feature processing branch, denotes the 1 1 convolution, and represents the 1 1 depthwise convolution.

-

(2)

Large branch: performs large-scale feature extraction through three depthwise convolutions (DC). (2)

here, for the input , after undergoing three depthwise convolutions 1 61, 61 61, 61 1 with large kernels, the results are summed to obtain the outcome of the large-scale feature processing .

-

(3)

Global branch: acquires global features through the Dual-Channel Attention Mechanism (DCAM) and Feature Spatial Attention Module (FSAM) modules, represented as follows: (3)

The DCAM utilizes a dual-channel attention mechanism to enhance mutual information among feature channels, thereby improving their representation capability. Initially, input features undergo a 1 1 convolution, followed by transformation into the frequency domain via the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT). In this domain, dual-channel weighting is applied through two distinct convolution paths, processing feature information across different channels. The features are then transformed back to the spatial domain using the Inverse Fast Fourier Transform (IFFT) and subjected to another 1 1 convolution to reconstruct the feature map. This process is further refined by fusing the features to strengthen inter-channel correlation and enhance feature expressiveness.

The FSAM improves feature extraction efficacy by transforming the feature map into the frequency domain for processing. Initially, input features undergo a 1 1 convolution, followed by the application of the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT), which transforms the feature map from the spatial domain to the frequency domain. In this domain, different frequency components are emphasized using weighted attention to enhance critical frequency information. The feature map is then transformed back to the spatial domain through the Inverse Fast Fourier Transform (IFFT). Lastly, the attention-enhanced frequency domain features are fused with the original features, resulting in an enriched feature representation.

Ultimately, the local features, large-scale features, and global features are fused through element-wise addition. The feature map obtained from the initial convolution is added element-wise to the fused features and then processed through a convolution layer to generate the final feature mapout.

(4)

In summary, the CSPOK-Fusion structure is primarily designed for the fusion of feature maps from layers S2 and S3. Building upon the original fusion framework, the CSPOK module is incorporated to facilitate the gradual fusion of partial features and implement residual connections. This approach enhances the completeness and richness of feature representation while maintaining computational efficiency. For small object detection, the CSPOK module minimizes redundant feature transmission and ensures that critical information is not lost within the network hierarchy. This structure effectively integrates deep and shallow features while ensuring computational efficiency. Such a design is particularly well-suited for small object detection tasks, enabling the model to capture target details across different scales and enhancing its capability to detect small objects in complex backgrounds.

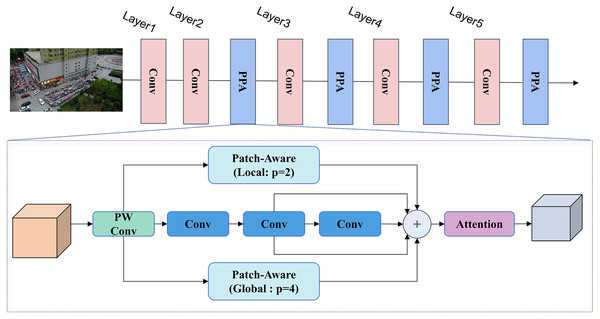

Backbone network structure

Feature extraction is critical for object detection in aerial images, commonly accomplished using a CNN-based architecture that constructs a five-layer feature pyramid to capture information at multiple scales and feature representations. However, many targets in aerial imagery appear as small objects, often occupying only a minor portion of the image. As the feature pyramid is constructed, these small objects are susceptible to gradual dilution or loss, while larger targets present increased complexity and diversity, which complicates the feature extraction process. To tackle these challenges, this study incorporates the PPA module (Xu et al., 2024) into the Backbone network, as illustrated in Fig. 7. Layer 1 uses convolutional operations to extract low-level features from the input image. Layers 2 to 4 integrate Conv modules with the PPA module to generate multi-scale feature maps. The PPA utilizes hierarchical feature fusion and attention mechanisms to maintain and enhance small object representations, ensuring that vital information is preserved throughout multiple downsampling steps, ultimately improving detection accuracy in later stages.

Figure 7: Backbone network structure.

Layer 1 extracts low-level feature information through convolutional modules, Layers 2 to 5 comprise Conv modules integrated with the PPA module, which includes two components: multi-branch fusion and attention mechanisms. The multi-branch block consists of local and global branches. VisDrone2019 dataset images attributed to the AISKYEYE team at Lab of Machine Learning and Data Mining, Tianjin University, China.The PPA employs a parallel multi-branch strategy, primarily comprising two components: multi-branch fusion and attention mechanisms. The fusion component integrates patch-aware and concatenated convolutions. By modifying the patch size parameter, local and global branches are distinguished, with the parameter ‘p’ set to 2 for local and 4 for global branches. Each branch is responsible for extracting features at varying scales and levels. This multi-branch approach enhances the capture of multi-scale features of targets, thereby improving the accuracy of small object detection.

Given the input feature tensor , it is initially processed through point-wise convolution to produce the desired output . Subsequently, calculations are performed for , , and through the three branches, respectively. Finally, the three results are aggregated to generate the final feature representation.

In the global branch, computationally efficient operations are used, including Unfold and Reshape, to divide F′ into a series of spatially continuous blocks ( ). Subsequently, each channel undergoes average processing to obtain the feature representation, which is then processed using a Feed Forward Network (FFN) (Chen et al., 2020) for linear computation. An activation function is applied to acquire the probability distribution of the linear computed features in the spatial dimension, allowing for corresponding weight adjustments. In the weighted results, feature selection (Yang et al., 2023) is utilized to choose task-relevant features from the tokens and channels.

The PPA module aligns and refines contextual information from multiple layers progressively through a hierarchical fusion approach. For small objects, this method helps retain fine details that are typically lost in traditional networks. This is crucial for detecting small objects in complex backgrounds, enabling effective execution of aerial image detection.

NWD loss function

Due to the low tolerance of bounding box perturbations, the detection of small targets is more susceptible to interference from noise and background debris, leading to an increase in false positives and false negatives. To address this issue, we employ a novel measure of NWD similarity in place of the IoU. The NWD distance presents an innovative solution by first modeling the bounding box as a two-dimensional Gaussian distribution and then assessing their similarity through the calculation of the Wasserstein distance between the two distributions. Due to its capacity to quantify the similarity between distributions, Wasserstein distance is particularly well-suited for evaluating the similarity of small objects, even in cases of negligible or non-existent overlap. Furthermore, NWD is less sensitive to variations in object scale, enhancing its applicability for small object detection.

Specifically, for horizontal bounding boxes , where represent the center coordinates, and denote the width and height, respectively. The two-stage Wasserstein distance between two bounding boxes is defined as follows:

(5) here, the distance measure cannot be directly utilized as a similarity measure (i.e., a value between 0 and 1 corresponds to IoU). Consequently, we applied an exponential normalization to derive a new metric known as NWD:

(6) here, C is a constant closely associated with the dataset. The loss function based on NWD is defined as follows:

(7) where is the Gaussian distribution model of the prediction box P, and is the Gaussian distribution model of the GT box G.

For small targets, the IoU metric is particularly sensitive to minor perturbations in the bounding box, even slight positional deviations can result in a substantial decline in IoU, adversely impacting detection accuracy. In contrast, the NWD distance assesses the similarity between Gaussian distributions of bounding boxes. It can evaluate the similarity between predicted and actual boxes more accurately, even when small perturbations are present, thereby enhancing detection accuracy.

Experiment

Dataset

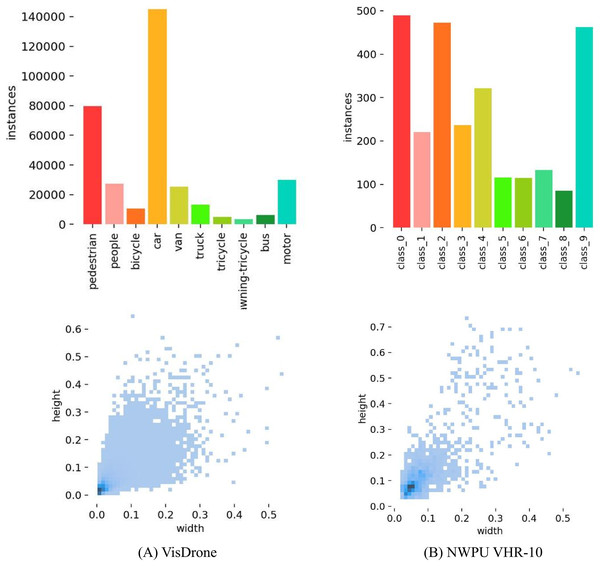

This study utilizes two widely used aerial image datasets for object detection: VisDrone 2019 (Zhu et al., 2021) and NWPU VHR-10 (Cheng et al., 2014). VisDrone 2019 is a large-scale dataset comprising 10,209 images captured by drones in urban and suburban areas across 14 Chinese cities. With a resolution of 2,000 1,500 pixels, it includes 542,000 instances spanning 10 common traffic scene categories such as pedestrians and vehicles. The dataset presents challenges like occlusion and varying viewpoints, with a high density of small objects, making it suitable for small object detection tasks. The VisDrone is available at https://github.com/VisDrone.

The NWPU VHR-10 dataset, released by Northwestern Polytechnical University, contains 650 annotated high-resolution remote sensing images covering 10 object categories, such as airplanes, ships, and bridges. These images are sourced from Google Earth and the Vaihingen dataset, encompassing diverse scene types with varying object densities, ranging from dense to sparse distributions. The dataset is partitioned into training, validation, and test sets with a 7:2:1 split. Both datasets contain numerous small, densely packed objects, providing a robust environment for evaluating object detection models in aerial imagery. The NWPU is available at https://labelbox.com/datasets/nwpu-vhr-10/.

Figure 8 shows the histogram of class instance distribution (first row) and the scatter plot of target box width and height distribution (second row) for two datasets. Figure 8A Listed as VisDrone 2019 dataset, Fig. 8B as NWPU VHR-10 dataset. The number of categories in VisDrone and NWPU VHR-10 is not equal, with significant differences. The width and height of the target in the second dataset are relatively small, which poses certain challenges for object detection.

Figure 8: Scatter plot of category distribution and width/height distribution for the VisDrone 2019 dataset and NWPU VHR-10 dataset, with the first row representing category distribution and the second-row representing width/height distribution.

Evaluation metrics and environment

Evaluation metrics

In this experiment, the complexity of the algorithm is quantified in terms of floating point operations (FLOPs). The performance metrics used for comparative evaluation of the network include precision (P), recall (R), average precision (AP), and mean average precision (mAP) for each class. All predicted results are classified as positive samples. The evaluation framework defines true positive (TP) as the count of correctly detected positive samples, false positive (FP) as the number of incorrectly identified positive samples, and false negative (FN) as the actual targets that were missed during detection.

Precision is defined as the probability of correct predictions among all predictions, thereby assessing the accuracy of the algorithm’s predictions. Recall represents the ratio of correctly predicted results to actual occurrences, measuring the algorithm’s ability to identify all target objects. These metrics correspond to the probabilities of false detection and missed detection, respectively.

(8)

The area under the precision-recall (P-R) curve obtained from different numbers of positive samples represents the average precision (AP) for each class, while the mean average precision (mAP) is calculated as the average of the average precision across all classes. The formulas are as follows:

(9)

Additionally, we employ other evaluation metrics. #P indicating the parameter size. This metric reflects the complexity of the model. Giga Floating Point Operations per Second (GFLOPs) refer to the number of floating-point operations performed by the model during execution, serving as a crucial indicator for assessing computational complexity.

Experimental environment

The experimental environment and setup are as follows: the model was implemented on an A800 GPU cluster equipped with three 256 GB GPUs, running on the Red Hat 4.8.5–28 operating system. Python version 3.11 and CUDA version 12.1 were used. Standard data augmentation techniques, such as random cropping, flipping, and scaling, were applied to enhance the model’s generalization capability. The baseline model employed was RT-DETR, using ResNet50 as the feature extraction CNN. Other parameters used in this study are listed in Table 1.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Optimizer | AdamW |

| base_learning_rate | 0.0001 |

| weight_decay | 0.0001 |

| global_gradient_clip_norm | 0.1 |

| linear_warmup_steps | 2,000 |

| Minimum learning rate | 0.00001 |

Ablation study

Ablation experiments were performed on the VisDrone and NWPU VHR-10 datasets to assess the effectiveness of the proposed improvements outlined in this section. Utilizing RT-DETR as the baseline and Resnet-r18 as the backbone network, the results obtained from the VisDrone validation dataset are displayed in Table 2.

| PPA | S2-CCFF | NWD | #P(M) | GFLOPS | mAP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | 38.61 | 56.8 | 44.8 |

| ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | 27.46 | 62.1 | 45.6 |

| ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | 39.8 | 66.9 | 46.8 |

| ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | 38.61 | 57.0 | 45.1 |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | 37.39 | 77.7 | 47.7 |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 37.39 | 76.0 | 47.9 |

The mAP of the baseline is 44.8%. Mainly because RT-DETR uses Transformer’s self-attention mechanism, although it can capture global information, when facing extremely small targets, the global features may be too sparse to fully focus on the target itself. This can cause the features of small targets to be ignored in larger contexts, thereby affecting detection accuracy.

After adding the PPA module, parameter reduced by 11.15 M approximately, GFLOPs increased, and mPA increased to 0.8%. Mainly because the PPA module adopts a multi branch fusion and attention mechanism. In multi-branch fusion, each branch uses different convolution operations (such as patch-aware and concatenated convolutions) to extract features, which are fused in subsequent stages. This fusion not only combines information from different scales but also enhances feature richness and representation ability through diverse convolution operations. The attention mechanism can further focus on key areas in the image, ensuring that key information is saved through multiple downsampling steps, thereby improving the detection accuracy of small targets. After only adding the S2-CCFF module, the number of parameters and calculations increased, and the accuracy also improved to 2%. This is because the S2-CCFF module adds an S2 layer that contains rich information about small targets during multi-scale feature fusion. At the same time, the CSPOK module adopts the CSP idea and global, large, and local branches to provide the model with a multi-granularity receptive field, effectively learning global to local feature representations. This improves the model’s ability to extract and fuse features for small targets and effectively suppresses background noise. However due to the addition of the S2 layer, the parameters of the model and the computer have increased. After introducing the NWD loss function, GFLOP remained almost unchanged, but mAP increased by 0.3%. This is due to the ability of NWD to evaluate the similarity between Gaussian distributions of bounding boxes. Even when small target bounding boxes encounter small deviations, NWD can more accurately measure the similarity between predicted boxes and real boxes than traditional methods, thereby optimizing detection accuracy. When using both PPA and S2-CCFF modules simultaneously, the parameter count is between the case of using only PPA or only S2-CCFF, and GFLOPs reach the highest of 77.7 G, but the accuracy is also improved by 2.9%. Indicating that these modules may have a synergistic effect. They can better adapt to small object detection tasks by cooperating and optimizing various aspects of the network, jointly improving the performance of small object detection tasks in aerial images. After adding three modules simultaneously, there was a 3.1% increase compared to the baseline. Indicating that these modules may have a synergistic effect. They can better adapt to small object detection in aerial images and jointly improve detection performance by cooperating and optimizing various aspects of the network.

In the NWPU VHR-10 dataset, we can obtain similar experimental results, as shown in Table 3 compared to having only one module, networks with overlapping blocks achieve better performance. The addition of three modules enables the model to gradually align and refine contextual information from multiple layers, ensuring that key information is saved through multiple downsampling steps, effectively fusing deep and shallow features, and effectively suppressing the interference of complex backgrounds to achieve better regression and classification results. Meanwhile, the experiment also showed that the proposed module had no conflicts, and when all proposed methods were adopted, the model exhibited the best performance of 89.5%.

| PPA | S2-CCFF | NWD | #P(M) | GFLOPS | mAP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | 38.61 | 57.0 | 86.4 |

| ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | 35.05 | 60.2 | 87.2 |

| ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | 39.80 | 65.2 | 88.2 |

| ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | 38.61 | 57.0 | 87.3 |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | 39.2 | 76.0 | 89.3 |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 39.2 | 76.0 | 89.5 |

The ablation experiments on the VisDrone and NWPU VHR-10 datasets show a modest performance improvement with the final model configuration (PPA, S2-CCFF, and NWD), increasing mAP by 3.1% on the VisDrone and NWPU VHR-10 dataset. However, this performance gain comes at the cost of increased computational complexity, with the number of parameters rising slightly and GFLOPS increasing significantly. This trade-off between improved detection performance and higher computational overhead raises concerns about scalability, particularly in real-time or resource-constrained settings. To enhance the method’s practical applicability, further optimization to reduce computational costs without sacrificing performance, such as pruning, quantization, or using more efficient architectures, should be explored. Additionally, evaluating the runtime or inference speed would help better understand the operational costs.

Comparative experiment

VisDrone

To further assess the effectiveness of our method, comparative experiments were performed on the VisDrone dataset alongside other established methods, as presented in Table 4. Faster R-CNN and Cascade R-CNN are classified as two-stage methods, while the remaining methods are one-stage approaches. The results indicate that Adaptive Training Sample Selection (ATSS) achieves the highest performance in mAP and mAP_l, while PF-DETR shows excellent performance in small target detection (mAP_s = 0.157) and is highly competitive at mAP_50 (0.393), making it suitable for applications that require high-sensitivity small target detection. You Only Look Once X (YOLOX) has the weakest overall performance, while RT-DETR shows a balance in small object detection and mAP_50, but both perform poorly under stricter conditions.

| Method | mAP | mAP_50 | mAP_75 | mAP_s | mAP_m | mAP_l |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Faster R-CNN (Ren et al., 2016) | 0.205 | 0.342 | 0.219 | 0.100 | 0.295 | 0.433 |

| Cascade R-CNN (Cai & Vasconcelos, 2019) | 0.208 | 0.337 | 0.224 | 0.101 | 0.299 | 0.452 |

| TOOD (Feng et al., 2021) | 0.214 | 0.346 | 0.230 | 0.104 | 0.303 | 0.416 |

| ATSS (Zhang et al., 2020) | 0.216 | 0.349 | 0.231 | 0.102 | 0.308 | 0.458 |

| RetinaNet (Lin, 2017) | 0.178 | 0.294 | 0.189 | 0.067 | 0.265 | 0.430 |

| RTMDet (Lyu et al., 2022) | 0.184 | 0.312 | 0.213 | 0.077 | 0.288 | 0.445 |

| YOLOX (Ge et al., 2021) | 0.156 | 0.283 | 0.155 | 0.078 | 0.213 | 0.288 |

| RT-DETR (Zhao et al., 2024) | 0.159 | 0.365 | 0.107 | 0.138 | 0.284 | 0.231 |

| PF-DETR | 0.176 | 0.393 | 0.123 | 0.157 | 0.330 | 0.227 |

This is because ATSS introduces the adaptive training sample selection (ATSS) mechanism, which adaptively selects positive and negative samples for each target and combines with the FPN to effectively integrate multi-scale features, especially with high robustness for detecting large targets. The adaptive positive sample selection mechanism helps to improve detection accuracy under strict IoU thresholds (such as mAP_l), and it can accurately select the most suitable anchor box. In addition, ATSS can effectively respond to targets of different scales through this mechanism, resulting in the best overall mAP performance.

Although YOLOX is a one-stage method, its performance in small object detection and high IoU threshold is poor. The anchor-free strategy adopted by YOLOX is more flexible in localization, but its ability to express features of small targets is insufficient. In addition, YOLOX’s FPN design cannot fully capture the detailed information of small targets when processing high-density small target scenes, resulting in a lower overall mAP. In addition, under stricter IoU thresholds such as mAP_75 and mAP_l, YOLOX’s robustness is not as good as ATSS and other methods because its positive and negative sample allocation mechanism has not been fully optimized for high IoU.

RT-DETR, as a DETR-based network, utilizes the Transformer architecture and its powerful self-attention mechanism helps capture global contextual information, resulting in a relatively balanced performance in small object detection and mAP_50. Transformer can effectively handle the relationships between objects and enhance feature learning, making it suitable for multi-scale object detection. The performance of RT-DETR is weak under strict conditions such as mAP_75 and mAP_l, mainly due to the Transformer model’s strong dependence on training data and slow convergence. At high IoU thresholds, the regression accuracy of RT-DETR is insufficient, making it difficult to match models with adaptive mechanisms such as ATSS. In addition, the optimization of RT-DETR may not fully adapt to small deviations of small targets under stricter IoU conditions.

PF-DETR is a network optimized for small object detection. It introduces modules such as S2-CCFF and PPA basis on RT-DETR, which significantly enhance the model’s perception of small targets by enhancing fine-grained feature extraction capabilities. Especially in the feature pyramid structure, the fine capture of small target information is more sensitive, avoiding the loss of small target features in the downsampling process of traditional detection networks. Therefore, PF-DETR performs well in small target detection (mAP_s = 0.157) and mAP_50 (0.393), making it suitable for small target scenarios that require high-sensitivity detection.

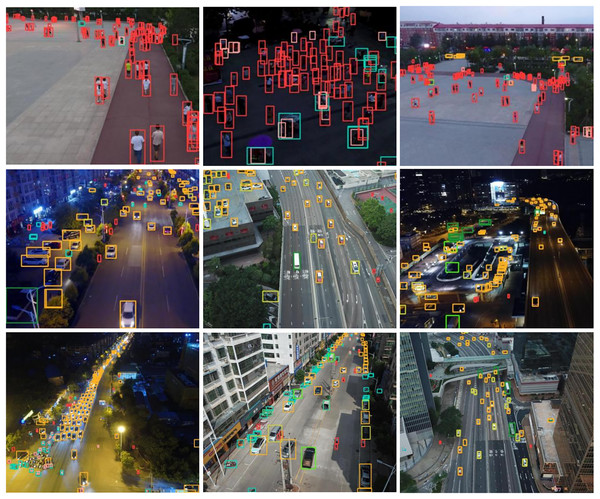

The VisDrone dataset in Fig. 9 displays city streets and roads at different times and locations. This includes various complex urban environments, including busy streets, intersecting roads, buildings, and bridges, which pose challenges to detection algorithms. From the detection effect diagram of the method in this article, it can be seen that the model has robustness for detecting small targets in different scenes, times, and types, especially for targets in complex scenes, as well as in varying lighting conditions, occlusions, and background interferences.

Figure 9: Detection results of PF-DETR on the VisDrone dataset.

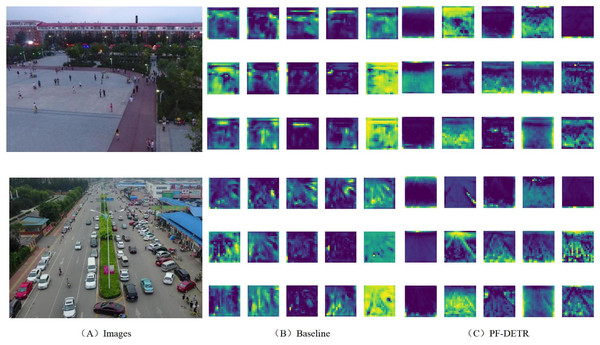

VisDrone2019 dataset images attributed to the AISKYEYE team at Lab of Machine Learning and Data Mining, Tianjin University, China.To further assess the effectiveness of the proposed method, feature maps were generated after the Encoder on two VisDrone images. In these maps, colors represent different activation intensities, with green and yellow regions indicating higher levels of activation. These areas signify features that substantially contribute to the model’s decision-making process (Liu et al., 2024d). As shown in Fig. 10A list as two original input images. The first image is a square, and the following image is a street with many vehicles and pedestrians. The second column shows the feature map generated by the baseline model, reflecting the spatial detail information extracted from the image. However, these feature maps appear noisy and scattered when focusing on specific areas of interest, such as pedestrians in squares or vehicles on streets. The activation areas are distributed throughout the feature maps, lacking concentrated attention to small targets. This scattered activation pattern reflects the baseline model’s less focused attention on smaller objects, which makes it harder to capture small and densely packed targets.

Figure 10: Feature maps created after encoder.

(A) shows two images from the VisDrone dataset, (B) illustrates the feature map produced by the Baseline method, while (C) depicts the feature map generated by the proposed method. The figure demonstrates that the feature maps derived from our method exhibit richer detailed information and a more pronounced hierarchical structure, effectively capturing a substantial number of small target features. VisDrone2019 dataset images attributed to the AISKYEYE team at Lab of Machine Learning and Data Mining, Tianjin University, China.The third column shows the feature maps generated by the PF-DETR model, demonstrating a more focused attention mechanism, especially in areas where there may be targets such as pedestrians and vehicles. In contrast, the activation area is clearer and exhibits stronger concentration in the relevant areas of small object detection. This indicates that the method proposed in this article can better capture feature information related to small objects. Compared with the baseline, the feature map of PF-DETR significantly reduces irrelevant noise and focuses more on key areas in the image, indicating higher efficiency in small object detection.

The visual representation of the feature map indicates that the proposed method concentrates more on specific regions within the image, resulting in the extraction of more pronounced features. In contrast, the feature map generated by the Baseline method displays a more dispersed color distribution, suggesting that the activated feature areas are broader. This lack of focus on target regions adversely impacts detection accuracy, potentially leading to false positives or missed detections.

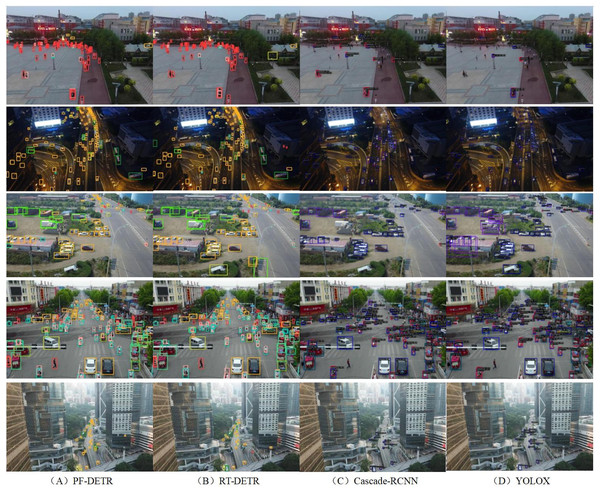

Figure 11 shows the comparison of object detection results between our method and RT-DETR, Cascade R-CNN, and YOLOX in different scenarios. By analyzing the detection performance of different methods in various scenarios, it can be seen from the figure that our method successfully detected a significantly higher number of small targets, especially pedestrians and small vehicles, in multiple scenarios (such as squares, nighttime roads, rural intersections, etc.), demonstrating its enhanced sensitivity to small targets and ability to perform well in crowded scenes. This is primarily due to the attention mechanism in our method, which focuses on small regions of interest, allowing it to extract more precise features related to small objects. This indicates that the method has good feature extraction and precise localization capabilities. In complex scenarios, the method proposed in this article can maintain a high detection rate, especially in high-density traffic areas, showing that it is highly effective at handling small objects in densely populated environments, demonstrating strong adaptability. The performance of RT-DETR is relatively balanced in various scenarios, especially in nighttime roads and high-density vehicle scenes, where it can detect most vehicles and pedestrians, demonstrating good ability in detecting medium-sized targets. However, RT-DETR has some shortcomings in detecting small targets such as distant pedestrians or small vehicles, especially in some long-distance or low-resolution scenes where there are relatively more missed detections. Cascade R-CNN has shown good detection performance for large vehicles and targets close to cameras in multiple scenarios, demonstrating its strong detection ability for large and medium-distance targets. However, in some target-dense scenarios (such as urban streets), Cascade R-CNN fails to detect pedestrians and small targets at long distances well, especially in scenes such as squares and rural intersections, where the phenomenon of missed detection is more obvious, indicating that it has certain limitations in detecting small or long-distance targets. YOLOX has low target detection accuracy in multiple scenarios, especially in urban roads and nighttime scenes, where many small targets have not been successfully detected. This indicates that YOLOX performs relatively poorly in handling complex scenes and small object detection. Although the overall performance is not as good as other methods, YOLOX still shows good localization ability when detecting large targets, such as large vehicles close to the camera.

Figure 11: Comparison of detection performance between the PF-DETR and popular methods.

VisDrone2019 dataset images attributed to the AISKYEYE team at Lab of Machine Learning and Data Mining, Tianjin University, China.PF-DETR achieved good detection results, mainly due to the difficulty of small object detection. A series of targeted optimization measures were proposed, such as the S2-CCFF module, PPA module, and NWD loss function. These modules help the model more effectively capture the detailed features of small targets, especially in distinguishing targets in complex backgrounds, enhancing the detection accuracy and recall rate of small targets. Detection accuracy.

NWPU VHR-10

The proposed method was assessed against leading techniques on the NWPU VHR-10 dataset, with findings summarized in Table 5. The results indicate that two-stage methods, such as Faster R-CNN and Cascade R-CNN, surpass various one-stage approaches, especially in the NWPU dataset, which features diverse land types and often ambiguous boundaries that complicate classification (Liu et al., 2024e). Additionally, the dataset contains numerous small features and densely populated areas with complex backgrounds, including buildings and trees, which can hinder classification accuracy due to occlusions and shadows. The two-stage approach first generates high-quality candidate regions (RoI) via a Region Proposal Network (RPN), followed by refined classification and localization of these regions. This two-step process improves target localization accuracy, particularly in cases with significant variations in target size, shape, and aspect ratio, allowing the two-stage method to capitalize on its strengths.

| Method | mAP | mAP_50 | mAP_0.75 | mAP_s | mAP_m | mAP_l |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Faster R-CNN (Ren et al., 2016) | 0.512 | 0.878 | 0.55 | 0.45 | 0.48 | 0.544 |

| Cascade R-CNN (Cai & Vasconcelos, 2019) | 0.543 | 0.881 | 0.583 | 0.35 | 0.486 | 0.576 |

| TOOD (Feng et al., 2021) | 0.482 | 0.876 | 0.498 | 0.45 | 0.446 | 0.549 |

| ATSS (Zhang et al., 2020) | 0.459 | 0.813 | 0.481 | 0.114 | 0.463 | 0.487 |

| RetinaNet (Lin, 2017) | 0.512 | 0.815 | 0.611 | 0.412 | 0.621 | 0.562 |

| RTMDet (Lyu et al., 2022) | 0.562 | 0.878 | 0.641 | 0.419 | 0.636 | 0.571 |

| YOLOX (Ge et al., 2021) | 0.522 | 0.841 | 0.615 | 0.345 | 0.505 | 0.588 |

| RT-DETR (Zhao et al., 2024) | 0.499 | 0.853 | 0.570 | 0.274 | 0.507 | 0.679 |

| PF-DETR | 0.570 | 0.882 | 0.629 | 0.403 | 0.546 | 0.678 |

Overall, Faster R-CNN and RetinaNet perform equally well and are suitable for scenarios with multiple target scales. YOLOX and Cascade R-CNN perform well under stricter IoU conditions, but there is room for improvement on small targets. Real-Time Multi-Scale Detection (RTMDet) performs well under medium to large targets and high IoU conditions, making it suitable for large target detection tasks in scenes. This is mainly due to multi-level feature fusion and efficient loss function optimization. PF-DETR enhances its sensitivity to small targets through innovative module design and loss function optimization, resulting in outstanding performance in small target detection tasks. Having high mAP and mAP_50 it is suitable for high-sensitivity small target detection tasks.

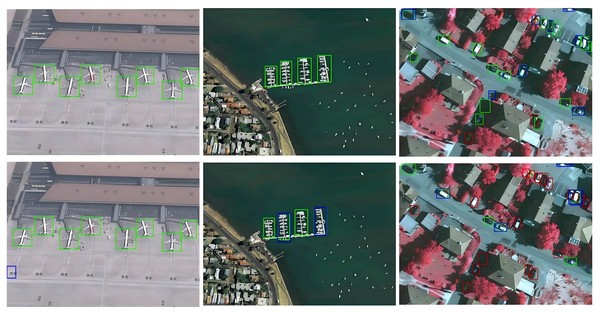

Figure 12 compares the detection performance of PF-DETR with the baseline approach on the NWPU VHR-10 dataset. The first row shows results from our method, while the second row presents the baseline results. Green boxes indicate true positives (TP), blue boxes represent false positives (FP), and red boxes denote false negatives (FN). The results highlight that the baseline method has a considerable number of false positives and missed detections. In contrast, our method effectively reduces both FP and FN, leading to more accurate object identification and improved detection accuracy.

Figure 12: Comparison of detection performance, The first row displays the results from PF-DETR, while the second row shows the baseline method.

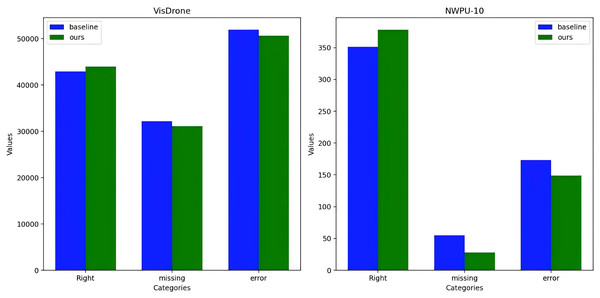

The proposed approach significantly reduces false positives (FP) and false negatives (FN), thereby enhancing detection accuracy. NWPU VHR-10 dataset images attributed to the Remote Sensing & GIS Group, School of Remote Sensing & Information Engineering, Northwestern Polytechnical University, Xi’an, China.Figure 13 presents a bar chart comparing the performance of two datasets in detection. The blue bars in the figure represent the baseline detection results, while the green bars represent the results of our method. The results depicted in the figure indicate that the PF-DETR enhances detection accuracy relative to the baseline, while also reducing the occurrence of false positives and missed detections. These findings demonstrate the effectiveness of the method in improving detection performance.

Figure 13: Detailed data comparison of detection results for VisDrone and NWPU VHR-10 datasets.

Conclusion

This article proposes an innovative small object detection model PF-DETR to address key issues in small object detection. This model combines the S2-CCFF module, PPA module, and NWD loss function, significantly improving the performance of small object detection. The main advantages of PF-DETR are reflected in the following aspects. Firstly, the S2-CCFF module enriches the information representation of small targets by adding S2 layers for cross-scale feature fusion, while using SPDConv to reduce computational complexity and preserve key details, successfully improving the accuracy and efficiency of detection. Secondly, the PPA module enhances the feature representation of small targets in the Backbone network through hierarchical feature fusion and attention mechanism, ensuring that key information is not lost during multiple downsampling processes, thereby improving detection performance. In addition, the introduced NWD loss function improves the tolerance of the model to boundary box disturbances by better measuring the relative position and shape differences of the boundary boxes, further enhancing the robustness of the model.

Although PF-DETR achieves significant improvements in small object detection, challenges remain, particularly in complex backgrounds and severe occlusions, where false positives or false negatives may still occur. Additionally, while SPDConv reduces computational complexity, the model still demands considerable computational resources, especially when processing high-resolution images. This slight increase in computational cost, although modest, could still pose challenges in real-time or resource-constrained settings. To address these concerns, future work should focus on optimizing feature fusion strategies and exploring more efficient multi-scale feature extraction methods. Additionally, lightweight network structures, such as pruning or quantization, could be employed to reduce the computational overhead while maintaining performance. Incorporating more contextual and semantic information through multi-modal fusion (Albanwan, Qin & Tang, 2024) could also help enhance detection capabilities in complex environments. These optimizations will make PF-DETR more efficient and applicable to a wider range of practical deployment scenarios.