A multi-round MRC framework incorporating prompt learning for aspect sentiment triple extraction

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Jyotismita Chaki

- Subject Areas

- Artificial Intelligence, Data Mining and Machine Learning, Natural Language and Speech, Sentiment Analysis, Neural Networks

- Keywords

- Aspect-based sentiment triplet extraction, Prompt learning, Machine reading comprehension

- Copyright

- © 2026 Yuyao et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2026. A multi-round MRC framework incorporating prompt learning for aspect sentiment triple extraction. PeerJ Computer Science 12:e3456 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3456

Abstract

Aspect-based sentiment triplet extraction (ASTE) task is a burgeoning subtask of aspect-based sentiment analysis (ABSA), which involves extracting aspect terms, opinion expressions, and related sentiment polarities from texts. However, previous pipeline methods for solving the ASTE task are susceptible to error propagation, while end-to-end sequence labeling methods have not fully utilized the given context. Additionally, existing machine reading comprehension (MRC)-based methods struggle to understand the complex grammatical structure and correspondence between aspect terms and opinion expressions, and fail to fully exploit the deep relationship between aspect-opinion pairs and sentiment polarity. To address these challenges, we propose the PromptReader, a multi-round MRC framework incorporating prompt learning. Specifically, we first design two rounds of MRC-based queries, where each round of queries consists of a pair of static and dynamic queries incorporating part-of-speech features and syntactic dependency information, aiming to jointly learn from two opposite perspectives to identify aspect-opinion pairs. Then, a round of queries based on prompt learning is designed, which contains a pair of dynamic queries, aiming to jointly learn under two different degrees of constraints to better predict sentiment polarity. Comprehensive experiments on four widely recognized benchmark datasets demonstrate that PromptReader surpasses the state-of-the-art methods by a significant margin.

Introduction

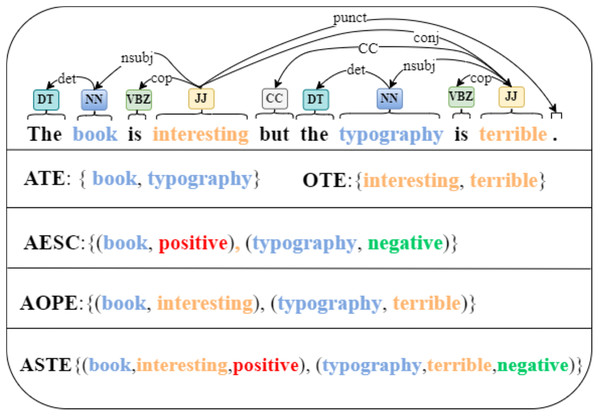

Sentiment analysis (SA) is the task of determining the sentiment (positive, negative, or neutral) expressed in text. Aspect-based sentiment analysis (ABSA) is a fine-grained variant of SA that focuses on detecting sentiment toward specific aspects and features mentioned in the text. For example, in the sentence “The camera quality is amazing, but the battery life is disappointing,” ABSA aims to identify that the sentiment toward “camera quality” is positive, while the sentiment toward “battery life” is negative. Traditional ABSA involves three essential subtasks: aspect term extraction (ATE) (Xu et al., 2018; Ma et al., 2019; Fadel, Saleh & Abulnaja, 2022; He et al., 2017), opinion term extraction (OTE) (Fan et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2020b; Yang & Cardie, 2013; Liu, Joty & Meng, 2015), and aspect sentiment classification (ASC) (Wang et al., 2016; Aydin & Güngör, 2020; Sweidan, El-Bendary & Al-Feel, 2021; Li et al., 2020; He et al., 2018; Yao et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2020), where ATE concentrates on extracting aspect terms that are relevant to specific entities, ASC is dedicated to predicting the sentiment polarity associated with those specific aspects, OTE focuses on extracting opinion expressions that describe the sentiment in a sentence. Previous studies have typically addressed these tasks individually or combined two of them to form new subtasks. For instance, the merging of ATE and OTE has given rise to the aspect-opinion pair extraction (AOPE) task (Wang et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2020b). Similarly, the combination of ATE and ASC has led to the formation of the aspect extraction and sentiment classification (AESC) task (He et al., 2019; Chen & Qian, 2022; Luo et al., 2019). While traditional ABSA tasks represent sentiment using discrete categories, recent advancements have introduced dimensional aspect-based sentiment analysis (dimABSA). This approach models sentiment as continuous numerical values across multiple dimensions, such as valence and arousal, allowing for more nuanced sentiment representation. For example, the recent shared task on Chinese dimensional ABSA organized by Zhu et al. (2024a) defines three subtasks: (1) sentiment intensity prediction, which aims to predict the valence and arousal scores for a given aspect term in a sentence; (2) triplet extraction, which involves extracting aspect-opinion-sentiment intensity triplets from text; and (3) quadruple extraction, which further includes aspect categories, resulting in aspect-category-opinion-intensity quadruples. Although the Chinese dimensional ABSA task also includes triplet extraction, its dimensional sentiment model differs from the categorical sentiment representation commonly used in mainstream ABSA research. Notably, Peng et al. (2020) proposed the Aspect-Based Sentiment Triplet Extraction (ASTE) task earlier, which unifies ATE, OTE, and ASC into a single framework. ASTE focuses on extracting structured (aspect, opinion, sentiment polarity) triplets, providing a categorical and interpretable approach that has been widely influential. As illustrated in Fig. 1, given the sentence “The book is interesting but the typography is terrible,” the ASTE task aims to accurately extract the two distinctive triplets (book, interesting, positive) and (typography, terrible, negative) present in the sentence.

Figure 1: Examples incorporating part-of-speech and syntactic dependency information are employed to illustrate various tasks, including ATE, OTE, AESC, AOPE, and ASTE.

Specifically, aspect terms are highlighted in blue, opinion terms in yellow, positive sentiment polarity in red, and negative sentiment polarity in green.Existing ASTE methods include pipeline approaches (Peng et al., 2020) that suffer from error propagation, sequence labeling methods (Xu et al., 2020) that struggle with long-range dependencies, and grid-based methods (Chen et al., 2022) that still fall short in capturing global semantics. Machine reading comprehension (MRC)-based methods (Mao et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2021) formulate structured prediction as question answering tasks, where models receive natural language queries to identify relevant text spans directly from input text. Despite progress, MRC-based approaches face three critical challenges: (1) they often overlook part-of-speech features and syntactic dependencies, which are crucial for understanding complex grammatical structures like contrastive relationships; (2) they lack flexible mechanisms to capture diverse aspect-opinion relationships including one-to-many, many-to-one, and overlapping patterns; (3) they fail to effectively leverage contextual information for accurate sentiment polarity prediction when multiple aspects share the same opinion or vice versa.

To overcome the limitations of existing MRC-based approaches, we propose PromptReader, a unified and structure-aware framework that reformulates the ASTE task as a multi-round MRC process augmented with prompt learning. Our work builds upon the foundations of two representative models: Dual-MRC (Mao et al., 2021), which employs dual modules for aspect and opinion extraction but relies on a static [CLS]-based classifier for sentiment prediction, and BMRC (Chen et al., 2021), which performs three-turn bidirectional querying yet lacks explicit integration of linguistic structures. In contrast, PromptReader introduces a three-round querying framework in which the first two rounds extract aspect-opinion pairs using static-dynamic query combinations from both directions to effectively capture one-to-many, many-to-one, and overlapping relations. The final round transforms sentiment classification into a prompt-based masked language modeling task, where dynamic natural language templates incorporating aspect-opinion pairs help guide the model in polarity prediction by fusing local contextual and global semantic information. Furthermore, we enrich the encoder with part-of-speech tags and syntactic dependency features, enabling the model to better understand grammatical structures such as modifier relations and long-range dependencies. These design choices collectively enhance the model’s ability to extract fine-grained triplets with improved accuracy and robustness. We perform comprehensive experiments on four widely recognized benchmark datasets and compare the performance of our framework with existing state-of-the-art methods. The experimental results unequivocally showcase that our proposed framework attains remarkable improvements compared to the existing state-of-the-art methods. Further analysis shows that each individual component we have proposed plays a vital role in enhancing the performance of the model.

In this work, we summarize our contributions as follows:

-

We propose PromptReader, a unified multi-round MRC framework that incorporates part-of-speech and syntactic dependency features into the encoder, enabling better modeling of complex grammatical structures.

-

We design a three-round querying mechanism with bidirectional static-dynamic queries to flexibly capture diverse aspect–opinion correspondences, including one-to-many, many-to-one, and overlapping relations.

-

We reformulate sentiment polarity prediction as a prompt-based masked language modeling task, where aspect–opinion pairs are embedded into natural language templates to fuse local and global semantic information.

-

Extensive experiments on benchmark datasets demonstrate that PromptReader achieves state-of-the-art performance, and ablation studies validate the effectiveness of each component.

Related works

Aspect-based sentiment analysis

Aspect-based sentiment analysis (ABSA) has evolved from traditional categorical sentiment models (positive/negative/neutral) to more nuanced approaches like dimensional aspect-based sentiment analysis (dimABSA), which represents sentiments with continuous scores across multiple dimensions such as valence and arousal. Recent works have addressed key challenges in ABSA, particularly the noisy interference problem when multiple aspects exist in a sentence. Shi et al. (2023) introduced syntax-enhanced models with multi-layer attention, while Yuan et al. (2024b) proposed syntactic graph attention networks to refine aspect representations. Chai et al. (2023) developed an aspect-to-scope oriented multi-view contrastive learning framework that mitigates noisy interference by better aligning aspects with their corresponding sentiment opinions through aspect-specific scope. In joint extraction paradigms, recent advances include Enhanced Machine Reading Comprehension for Aspect Sentiment Quadruplet Extraction (ACL 2022) and USSA: A Unified Table Filling Scheme (ACL 2023). The concept of “slots” in ABSA refers to semantic constituents—text spans conveying key aspect-related information—that must be correctly aligned with their respective aspects. Zhu et al. (2024b) addressed scope and prediction misalignment through Adjustive and Forced Cross-task Alignment in Aligner2, while Zhu et al. (2024b) proposed sequential prompting to exploit duality in aspect sentiment extraction.

Contrastive learning has emerged as a powerful framework across ABSA tasks. Chai et al. (2023) demonstrated how multi-view contrastive learning effectively mitigates noisy interference in multi-aspect scenarios. Wang, Yu & Zhang (2024) introduced SoftMCL, which uses valence ratings as soft-label supervision to measure sentiment similarities at finer granularity than traditional polarity labels, addressing latent space collapse while overcoming GPU memory limitations through a momentum queue that expands the contrastive sample pool. Large Language Models have also been increasingly integrated into ABSA, with approaches like PFInstruct (Cabello & Akujuobi, 2024) achieving state-of-the-art performance through instruction-based generation, and retrieval-augmented instruction tuning (Zheng et al., 2024) demonstrating strong few-shot capabilities.

Aspect-based sentiment triplet extraction

Aspect-Based Sentiment Triplet Extraction (ASTE) is a comprehensive task proposed by Peng et al. (2020) to jointly extract aspect terms, opinion terms, and sentiment polarities from text. In the early stage of this research, Peng et al. (2020) introduced a two-stage pipeline model that first identified potential aspect-sentiment pairs and opinion terms, and then paired these extracted elements into triplets. Although effective, this pipeline approach suffered from error propagation, which limited its overall performance. To address this issue, subsequent works shifted toward end-to-end frameworks. Xu et al. (2020) proposed the first end-to-end model employing a position-aware tagging scheme capable of jointly extracting triplets in one step. This was further refined by Wu et al. (2020a) through a unified grid tagging strategy (GTS), which explicitly models the interactions between aspect terms and opinion terms in a structured tagging grid. Meanwhile, generative methods emerged as an alternative paradigm for ASTE. Yan et al. (2021) reformulated the task as a sequence generation problem, utilizing pointer networks and sentiment class indices to represent extraction targets, thus converting all ABSA subtasks into a unified generation framework solved via a pretrained BART model. Similarly, Zhang et al. (2021b) proposed a unified generative framework that formalizes various ABSA subtasks as text generation problems by modeling annotation and extraction styles through style-specific templates, providing flexibility across subtasks. To better capture the structural and relational information within text, graph-based approaches gained traction. Su et al. (2024) introduced the multi-view language feature enhancement (MvLFE) method, which leverages relational graph attention networks to encode word-pair dependencies, improving the precision of triplet extraction. Zhai et al. (2023) designed a unified table-filling scheme (USSA) incorporating dual-axis attention and dependency graphs to effectively handle the challenges posed by overlapping and discontinuous spans in extraction. Additionally, Yuan et al. (2024a) incorporated syntactic dependency tree information into transformer architectures to enhance triplet extraction by explicitly encoding grammatical structures, leading to more robust performance.

Another important research direction transforms the ASTE task into a machine reading comprehension (MRC) problem. Works such as Chen et al. (2021), Mao et al. (2021), Zhai et al. (2022) and Zou et al. (2024) employed question-answering frameworks to predict sentiment triplets in an end-to-end manner. Building on this, Liu et al. (2024) proposed a dual-learning framework that leverages sequential prompting and regularization losses to improve the coherence and consistency of extracted triplets. Furthermore, Ye, Zhai & Li (2023) enhanced MRC methods by introducing hierarchical classification and multi-turn question-answering mechanisms, which enable the fine-grained capture of relationships among aspect terms, opinion terms, and sentiment polarities. However, as we pointed out above, existing MRC-based methods still have several unresolved challenges. They often overlook complex syntactic relations between aspect and opinion terms, struggle with diverse alignment patterns such as one-to-many or overlapping pairs, and fail to fully utilize local and global context when predicting sentiment polarity.

Prompt learning

The fundamental concept of prompt learning revolves around the utilization of prompt templates to guide model predictions. A prompt template serves as a versatile structure that encompasses inquiries, responses, and other pertinent information aimed at enhancing the model’s contextual comprehension and generating more precise outcomes. Prompt learning has gained significant traction in the realm of NLP, finding wide application. For instance, Radford et al. (2019) employed task descriptions as prompts to assess the performance of GPT-2 models in downstream tasks. Lester, Al-Rfou & Constant (2021) proposed a methodology to steer the fine-tuning process of pre-trained language models (PLM) by acquiring prompt templates that prove effective for a given downstream task. Shin et al. (2020) presented an approach for automatic prompt generation to extract task-specific knowledge from PLM. In the domain of sentiment analysis, Ben-David, Oved & Reichart (2022) introduced an example-based prompt learning technique known as PADA, which generates domain- or topic-specific prompts to facilitate adaptive learning of PLM. Furthermore, Yang & Zhao (2022) pioneered the treatment of sentiment classification as a prompt learning task, yielding favorable outcomes for the AESC task. In this article, we introduce for the first time the application of prompt learning to the ASTE task, leveraging the synergy of two prompt queries with varying levels of constraints to enhance sentiment classification outcomes. Moreover, Prompt Learning demonstrates strong capabilities in small sample and multi-task learning. Wang et al. (2022) introduced the ASCM+SL model, which optimizes the cue answer space by clustering and synonym initialization in the semantic embedding space. The stable knowledge distillation via ladder learning significantly enhances small-sample classification performance. Song et al. (2024) reviewed Prompt Learning methods supported by large language models (LLMs) and highlighted its technical advantages.

Preliminary

Task formulation

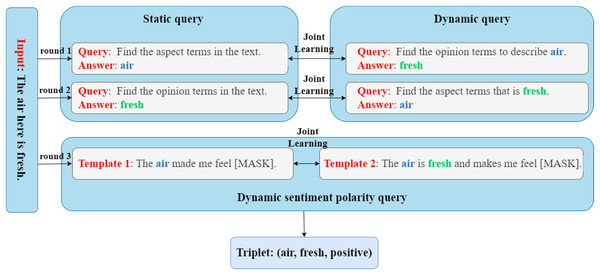

Given a sentence comprising tokens, the objective of the ASTE task is to extract a collection of triples , where denotes the aspect terms, denotes the opinion expression, denotes the related sentiment polarity, and |T| denotes the count of triplets. The sentiment polarity can assume one of three possibilities: positive, neutral, or negative. That is, . In order to model the above tasks as a multi-round MRC task incorporating prompt learning, as shown in Fig. 2, we set up three rounds of queries in total, where the first two rounds of queries consist of a static query and a dynamic query respectively, and the final round of queries includes two dynamic queries and based on prompt learning. Here, a “static” query is a fixed, pre-defined question designed to extract general information from the input sentence. In contrast, “dynamic” queries are generated based on intermediate extraction results from previous steps. Specifically, a dynamic query is conditioned on the aspect or opinion terms already identified, allowing the model to progressively narrow its focus and more effectively resolve contextual ambiguities.

Figure 2: The overall architecture of our PromptReader framework.

Specifically, in the first round of queries, we first construct a static aspect term query to extract all aspect terms contained in the sentence X, and then we design a dynamic opinion term query to identify the corresponding opinion term set based on the just-extracted aspect term set . In the second round of queries, we take the opposite approach compared to the first round. Firstly, we construct a static opinion term query to extract all the opinion terms present in the sentence X. Subsequently, we devise a dynamic aspect term query to identify the corresponding aspect term set based on the just-extracted opinion term set . Then, according to our designed inference strategy, we infer the final aspect term set A, opinion term set O, and aspect-opinion pairs through the results of , , and . Finally, in the final round of queries, based on prompt learning, we create two dynamic sentiment polarity queries and with different degrees of limiting conditions, using prompt templates and , respectively. The dynamic query aims to identify the corresponding sentiment polarity set of the aspect term set A based on the prompt template , while the dynamic query aims to identify the corresponding sentiment polarity set of the aspect-opinion pairs based on the prompt template .

Query design

In the three rounds of queries, the first two rounds are formulated as MRC tasks to extract aspect-opinion pairs, while the final round is formulated as a prompt learning task to predict sentiment polarity. All of these tasks employ template-based methods to construct queries. Specifically, in the first round of queries, we devise the following static aspect term query and dynamic opinion term query :

Static aspect terms query : The query “Find the aspect terms in the text.” is designed to extract all aspect terms.

Dynamic opinion terms query : The query “Find the opinion terms to describe {aspect}.” is designed to extract all opinion expressions that describe the given aspect word {aspect}.

Instead, in the second round of queries, we devise the following static opinion term query and dynamic aspect term query :

Static opinion terms query : The query “Find the opinion terms in the text.” is designed to extract all opinion expressions.

Dynamic aspect terms query : The query “Find the aspect term that is {opinion}.” is designed to extract all aspect terms for a given opinion word {opinion}.

Finally, in the final round of queries, we devise two dynamic queries and based on prompt learning, and their prompt templates are as follows:

Dynamic sentiment polarity query : This query uses the prompt template “The {aspect} made me feel [MASK].”, aims at classifying the sentiment polarity according to specific aspect word {aspect}.

Dynamic sentiment polarity query : This query uses the prompt template “The {aspect} is {opinion} and makes me feel [MASK].”, aims at classifying the sentiment polarity according to specific aspect word {aspect} and opinion word {opinion}.

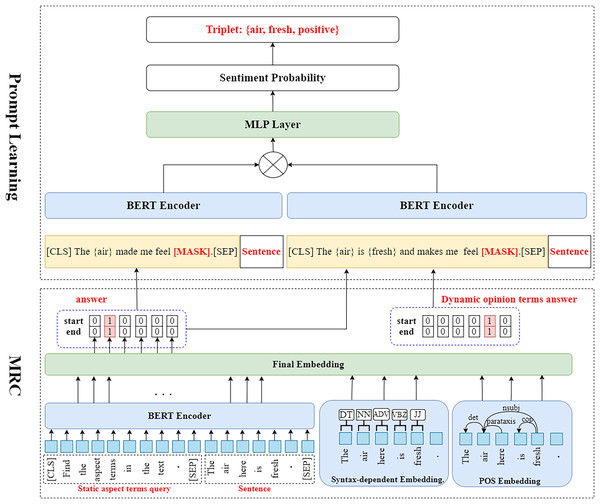

We have drawn the detailed internal structure of the PromptReader model. The figure below is the machine reading comprehension framework used in the first two rounds of queries, and the figure above is the prompt learning framework used in the last round of queries, as shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: The architecture of PromptReader consists of two main components.

The bottom part illustrates the machine reading comprehension (MRC) framework, only shows the process of extracting aspect terms in the first round of machine reading comprehension. The input and encoding layer concatenates predefined queries with the sentence and encodes them using BERT to obtain contextualized embeddings. In addition, part-of-speech features and syntax-dependent embeddings are incorporated, and the final embedding layer fuses BERT contextual representations, POS features, and dependency information into comprehensive contextual embeddings for span prediction. The top part illustrates the prompt-based learning module, which integrates the extracted aspect–opinion pairs into masked templates. These templates are encoded with BERT and processed by an MLP layer to predict sentiment polarity, thereby producing complete aspect–opinion–sentiment triplets.Proposed framework

Aspect-opinion pair extraction as machine reading comprehension

Input and encoding layer

Given a sentence consisting of tokens and a query comprising tokens, the encoding layer aims to acquire the contextual representation, part-of-speech features, and syntactic dependency information for each token.

Contextualized embedding. To encode all tokens in sentence X and enhance the context representation of sentence X with query information , we begin by concatenating the query and sentence X to form the input sequence , where [CLS] represents the start token and [SEP] denotes the segment token. Subsequently, we input this sequence into an efficient pre-trained Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) model (Devlin et al., 2018) to obtain contextual embeddings , as the model has demonstrated remarkable success in diverse NLP tasks (Madabushi, Kochkina & Castelle, 2020; Sun & Yang, 2019). Specifically, the BERT model employs a bidirectional Transformer (Vaswani et al., 2017) that combines masked language modeling (MLM) and next-sentence prediction, enabling it to learn contextual feature information from all layers. The BERT model, trained on the English Wikipedia, encompasses approximately 25 million words, and its final layer generates 768-dimensional contextual word embeddings for each word, thereby enabling us to extract rich semantic information.

Part-of-speech embedding. We acquire the part-of-speech (POS) tags for each token in the sentence X using the Universal POS tags (https://universaldependencies.org/u/pos/). Subsequently, we feed P into a pre-trained POS embedding layer to acquire the lexical embedding for the sentence X. The POS embedding layer processes the sparse vector representation P and extracts a dense vector , where and represents the size of the hidden states in the POS embeddings.

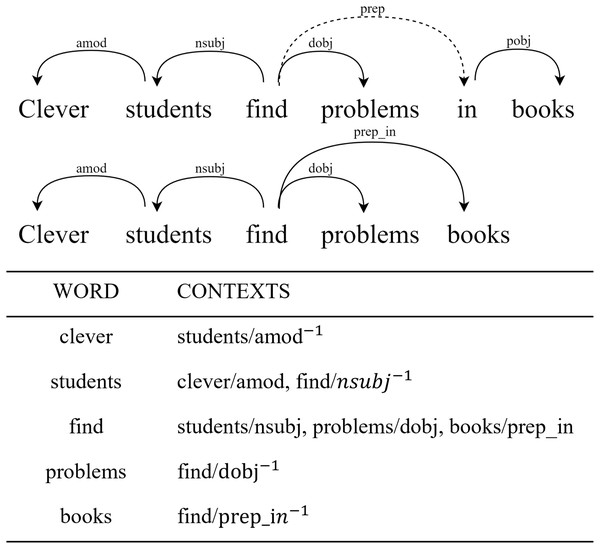

Syntax-dependent embedding. To obtain the syntactic dependency embedding for the sentence X, we employ context-based dependency analysis grounded in the syntactic roles that words play within a dependency tree. Specifically, for each target word and its associated modifiers , we construct a contextual set , where denotes the syntactic relation between and modifier . When the word functions as a dependent rather than a governor, we annotate the relation as to indicate the reversed direction. To better represent prepositional dependencies (e.g., prep_in), we collapse prepositions into a single composite relation before extracting the final context. As illustrated in Fig. 4, we parse the sentence into a dependency tree and collect such syntactic features for each token. For example, in the phrase “clever students,” the word “clever” is linked to “students” via an amod relation, yielding the context feature students/amod−1. Similarly, the verb “find” governs both dobj and nsubj relations, resulting in features like problems/dobj and students/nsubj. All context features are encoded in the form related-word/relation or related-word/relation−1, depending on the directionality of the arc. These features are then fed into a syntax-aware embedding module, enabling the model to capture fine-grained contextual semantics grounded in grammatical structure.

Figure 4: Syntactic dependency analysis example for sentence: “Clever students find problems in books”.

(A) Dependency Tree: Arrows indicate directed grammatical relations with Universal Dependencies v2 labels. (B) Context Feature Extraction: For each token, its syntactic contexts are encoded as (dependent/relationdirection) pairs, where direction markers (−1) indicate inverse relations.Final embedding. Finally, to enhance the context information of the sentence X, we concatenate the syntactic dependency information and part-of-speech features with the existing context. This results in an enriched context embedding that incorporates all the relevant linguistic features, where , , and .

Answer prediction layer

For both static and dynamic queries, multiple entities can be extracted as answers from sentence X. In the provided example sentence shown in Fig. 1, the answer for the static aspect term query would be “book” and “typography”, while the answer for the static opinion term query would be “interesting” and “terrible”. Therefore, to predict the answer span, we utilize two binary classifiers. One classifier assesses the probability of each token being the starting position, while the other classifier assesses the probability of each token being the ending position of the answer. These classifiers are based on the enriched contextual embedding of the sentence X.

(1)

(2) where and are learnable model parameters, and is the hidden dimension of the enriched context embedding . Then for a start position and an end position predicted as an aspect term or opinion expression, its predicted span probability is defined as follows:

(3)

To prevent the issue of unilateral decrease in the span probability , we adopt the approach inspired by Liu, Li & Li (2022), which involves taking the square root of the result. This ensures a more balanced weighting of the probability predictions for the start and end positions. For instance, if we have and , the without taking the square root would be 0.2376, which could lead to unreasonable results. However, by taking the square root, the resulting value would be 0.4874, providing a more reliable and balanced weighting of the probability predictions.

Inference strategy

During the inference process, we combine the answers obtained from the first two queries to generate the aspect terms set A, opinion terms set O, and aspect-opinion pairs . Specifically, in the first query, we extract aspect terms using the static aspect term query . For each aspect term obtained, we use the dynamic opinion term query to extract the opinion expressions and generate the predicted aspect-opinion pairs , where is the number of opinion terms obtained through query . Similarly, in the second query, we obtain the predicted aspect-opinion pairs , where is the number of aspect terms obtained through query . Finally, we match the aspect-opinion pairs in and according to the following matching strategy to obtain the final aspect-opinion pairs .

(4)

(5) where is the span probability predicted as an aspect term, is the span probability predicted as an opinion term, and are the intersection and difference sets of aspect-opinion pairs and respectively. That is, , , and is a probability threshold (We empirically set ). If and only when the predicted probability of the aspect-opinion pair in the is not less than the threshold , it can be considered into the final result .

Sentiment polarity prediction as prompt learning

Combining the aspect-opinion pairs obtained from the output of the MRC module in the first two rounds of querying, we can create two prompt templates and , to facilitate the modeling of the sentiment polarity query task as a prompt learning task. This conversion allows us to transform the classification problem into predicting the [MASK] token within the prompt template sentence T using a pre-defined word . In this case, given a sentence X, a constructed prompt template T, and the corresponding sentiment polarity for the aspect term, the input sequence for the prompt learning model is {[CLS]T[SEP]X}. The objective is to maximize the likelihood of predicting the correct sentiment polarity y in the masked position of the prompt template sentence T.

(6)

Specifically, we first construct the prompt templates and respectively according to the aspect term A and opinion term O in the aspect-opinion pair set .

= The {aspect} made me feel [MASK].

= The {aspect} is {opinion} and makes me feel [MASK].

where and . The sequences and are then fed into the pretrained BERT model (Devlin et al., 2018) to obtain their contextual representations and respectively. We only need [MASK] representation and that contains the sentiment polarity prediction information. In order to make the prediction result more robust, we sum them up and finally get the final prediction result of the [MASK] token:

(7)

In previous studies (Seoh et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021a), the sentiment polarity was extracted by directly predicting the probability of several representative words. However, we believe that this approach is relatively crude and less robust. To overcome this limitation, we introduce a novel approach. We utilize a two-layer multilayer perceptron (MLP) with the ReLU function (Glorot, Bordes & Bengio, 2011) to estimate the probabilities of [MASK] tokens representing different sentiment polarities. This approach enhances the precision and reliability of sentiment polarity prediction.

(8) where the output result has a dimension of 3, representing the probability distribution of tripolarity.

Join learning

To enable join learning within each of the three rounds of queries, we combine the loss functions from different queries. In the first round of queries, we minimize the Cross-Entropy loss, which is expressed as follows:

(9) where represents the number of times the first round of queries is used, and represent the static and dynamic query templates of the ith query respectively, and represents the predicted probability distribution.

Similarly, the losses for the second and third rounds of queries are calculated as follows:

(10)

(11)

Then, we add the above three losses together for backpropagation, and the total loss can be formalized as:

(12) where , and are all hyperparameters, we empirically set .

Experimental settings

Datasets

To evaluate the effectiveness of our proposed approach, we conduct experiments on four widely used benchmark datasets for ASTE: Laptop14, Rest14, Rest15, and Rest16. Table 1 presents detailed statistics of these datasets, including the number of sentences and annotated aspect-sentiment triples for training, development, and test splits. These datasets originate from the SemEval ABSA challenges (Pontiki et al., 2014, 2015, 2016). Following common practice and to ensure fair comparison, we adopt the same preprocessing steps and data splitting strategy as those used in Dual-MRC. Specifically, each dataset is initially divided into training and test sets according to the original SemEval task releases. We further randomly select 20% of the training set to serve as a development set for hyperparameter tuning and early stopping. A fixed random seed is used for the split to ensure reproducibility.

| Dataset | 14lap | 14res | 15res | 16res | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #S | #T | #S | #T | #S | #T | #S | #T | |

| Train | 920 | 1,265 | 1,300 | 2,145 | 593 | 923 | 842 | 1,289 |

| Dev | 228 | 337 | 323 | 524 | 148 | 238 | 210 | 316 |

| Test | 339 | 490 | 496 | 862 | 318 | 455 | 320 | 465 |

Note:

#S represents the number of sentences, and #T represents the number of triples.

The benchmark datasets are widely adopted in aspect-based sentiment analysis research. All datasets were annotated by multiple human experts, and the original works report high inter-annotator agreement, reflecting the reliability of the ground-truth labels. Each dataset provides fine-grained annotations for aspect terms, opinion expressions, and sentiment polarities. These detailed annotations make the datasets well-suited for evaluating nuanced sentiment understanding and the model’s ability to extract structured aspect-opinion-sentiment triplets.

Baseline methods

To demonstrate the effectiveness of PromptReader, we conduct a comprehensive comparison with 12 state-of-the-art methods across three categories:

RINANTE+, an improved version of RINANTE (Dai & Song, 2019), is proposed by Peng et al. (2020). It follows a two-stage framework: first extracting aspect and opinion terms using rule-based methods from auxiliary product reviews, then applying a BiLSTM-CRF model to further refine the extraction.

TSM is a two-stage pipeline model introduced by Peng et al. (2020). In the first stage, it extracts aspect entities, sentiment polarity, and opinion expressions. The second stage then pairs the extracted components into sentiment triplets using a relation classifier.

JET, proposed by Xu et al. (2020), is the first end-to-end model for ASTE. It introduces a position-aware tagging scheme that enables the model to jointly extract aspect-opinion-sentiment triplets in a unified manner.

GTS is a framework presented by Wu et al. (2020a). This framework is designed to search for aspect terms, opinion expressions, and related sentiment polarity in the rows and columns of a table.

EMC-GCN, introduced by Chen et al. (2022), encodes syntactic information using a bijective attention module and constructs multi-channel graphs. A refinement strategy is then applied to improve word representations and matching accuracy between word pairs.

STAGE, proposed by Liang et al. (2023), reformulates ASTE as a multi-class span classification task. It applies a span tagging scheme across three role dimensions and uses a greedy inference strategy to recover sentiment triplets from candidate spans.

Dual-Channel Span, developed by Li, Li & Zhang (2023), extracts aspect and opinion spans via two separate streams. It employs mutual guidance and interactive learning between the two channels to better capture their dependencies and improve triplet prediction.

SA-Transformer, introduced by Yuan et al. (2024a), is a syntax-aware transformer model that encodes dependency edge types. It incorporates adjacent edge attention and syntactic distance to refine graph propagation, enhancing multiword term extraction.

SE-ASTE, proposed by Shang et al. (2025), employs a syntax-enhanced multi-task learning approach for aspect sentiment triplet extraction. It incorporates syntactic dependency information via a graph convolutional network (GCN) with attention, enhances word representations with lexical features, and uses a biaffine scorer for sentiment extraction.

Dual-MRC, proposed by Mao et al. (2021), formulates ASTE as two machine reading comprehension tasks. It trains a shared BERT-based MRC model to jointly handle the extraction of all components in sentiment triplets.

BMRC, developed by Chen et al. (2021), introduces a bidirectional query structure with restricted/unrestricted extraction and sentiment classification queries. Each triplet component is identified from both directions to improve robustness.

COM-MRC, proposed by Zhai et al. (2022), presents a novel Context-Masked Machine Reading Comprehension framework for ASTE. It addresses the interference problem in multi-aspect sentences through a context augmentation strategy, a discriminative model with four collaborative modules, and a two-stage inference method.

Implementation details

Our model is implemented using the PyTorch framework. We use the BERT-base-uncased model (Devlin et al., 2018) as the backbone encoder, which consists of 12 Transformer layers, 12 attention heads per layer, and a hidden size of 768. The BERT parameters are fine-tuned with a learning rate of , while the classifier layers are optimized with a higher learning rate of to facilitate faster convergence. We adopt the AdamW optimizer (Loshchilov & Hutter, 2017) with a weight decay of 0.01 and a linear warm-up over the first 10% of the total training steps. To mitigate overfitting, a dropout rate of 0.5 is applied after the BERT encoding layer.

Training is performed for 50 epochs with a batch size of 2. We evaluate model performance on both development and test sets after each epoch. We fix the random seed to 42 across all experiments to ensure consistency within our experimental setup, while acknowledging that complete reproducibility across different environments may require additional considerations including exact library versions and hardware specifications. All training and evaluation procedures are conducted on two NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPUs, each with 24 GB of memory. Our full codebase, including data preprocessing, training scripts, and evaluation protocols, is publicly available at https://github.com/zyy238/PromptReader.

Evaluation metrics

We evaluate the performance of using three widely adopted metrics in the ASTE task: Precision, Recall, and F1-score, following the standard evaluation protocols in prior studies (Peng et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020a; Fei et al., 2021; Huan et al., 2022; Chen et al., 2022; Mao et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2021). These metrics are computed based on the prediction of complete aspect-opinion-sentiment triplets.

Precision measures the proportion of correctly predicted triplets to the total number of predicted triplets:

(13) where TP denotes the number of correctly predicted triplets, and FP denotes the number of predicted triplets that do not match any gold triplet.

Recall calculates the proportion of correctly predicted triplets to the total number of gold triplets:

(14) where FN denotes the number of gold triplets that are not predicted by the model.

F1-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall:

(15)

A predicted triplet is considered correct only if the aspect term, opinion term, and sentiment polarity all exactly match the ground-truth triplet. Among the three metrics, we report and compare the F1-score as the primary indicator of model effectiveness due to its balanced consideration of both precision and recall.

To further assess whether the performance differences between and baseline models are statistically significant, we conduct a paired t-test on the F1-score obtained from multiple independent runs. The paired t-test evaluates whether the mean difference in F1-score between two models is significantly different from zero, under the assumption that these differences are approximately normally distributed. A resulting -value less than 0.05 indicates that the performance difference is statistically significant at the 95% confidence level.

Results and analysis

Main results

We evaluate our model on the ASTE task, as well as its two coupled sub-tasks: AESC and AOPE. The experimental results are presented in Table 2.

| Task | Baseline | 14lap | 14res | 15res | 16res | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | R | F1 | P | R | F1 | P | R | F1 | P | R | F1 | ||

| AESC | RINANTE+ | 41.20 | 33.20 | 36.70 | 48.97 | 47.36 | 48.15 | 46.20 | 37.40 | 41.30 | 49.40 | 36.70 | 42.10 |

| TSM | 63.15 | 61.55 | 62.34 | 74.41 | 73.97 | 74.19 | 67.65 | 64.02 | 65.79 | 71.18 | 72.30 | 71.73 | |

| JET | 63.03 | 62.30 | 62.85 | 71.36 | 73.31 | 72.68 | 64.51 | 62.38 | 63.30 | 68.51 | 70.13 | 69.20 | |

| GTS | 65.35 | 61.08 | 63.72 | 74.12 | 75.50 | 74.63 | 66.18 | 64.72 | 65.65 | 70.68 | 71.45 | 71.05 | |

| EMC-GCN# | 69.82 | 66.95 | 68.36 | 77.8 | 79.29 | 78.54 | 69.25 | 66.2 | 67.69 | 73.63 | 80.49 | 76.91 | |

| STAGE# | 76.62 | 56.93 | 65.32 | 84.92 | 72.54 | 78.24 | 77.11 | 60.41 | 67.75 | 81.66 | 72.76 | 76.95 | |

| Dual-Channel Span# | 71.86 | 67.99 | 69.87 | 75.74 | 59.54 | 66.67 | 63.78 | 50.15 | 56.15 | 65.83 | 58.47 | 61.93 | |

| SA-Transformer | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| SE-ASTE | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| COM-MRC# | 72.25 | 65.22 | 68.56 | 80.98 | 73.82 | 77.24 | 78.75 | 66.9 | 72.34 | 75.85 | 73.67 | 74.75 | |

| BMRC | 63.41 | 61.84 | 62.27 | 74.73 | 74.41 | 73.52 | 65.31 | 61.52 | 63.15 | 70.84 | 70.11 | 70.46 | |

| DualMRC | 67.45 | 61.96 | 64.59 | 76.84 | 76.31 | 76.57 | 66.84 | 63.52 | 65.14 | 69.18 | 72.59 | 70.84 | |

| Ours | 73.78 | 68.66 | 71.13* | 78.64 | 79.61 | 79.12** | 72.11 | 71.22 | 71.66** | 75.23 | 82.47 | 78.68* | |

| AOPE | RINANTE+ | 34.40 | 26.20 | 29.70 | 42.32 | 51.08 | 46.29 | 37.10 | 33.90 | 35.40 | 35.70 | 27.00 | 30.70 |

| TSM | 50.00 | 58.47 | 53.85 | 47.76 | 68.10 | 56.10 | 49.22 | 65.70 | 56.23 | 52.35 | 70.50 | 60.04 | |

| JET | 65.02 | 56.45 | 58.68 | 72.30 | 73.75 | 72.60 | 64.88 | 62.30 | 63.35 | 68.64 | 70.48 | 69.31 | |

| GTS | 68.33 | 55.04 | 60.97 | 74.13 | 69.49 | 71.74 | 66.26 | 63.19 | 65.39 | 70.48 | 72.39 | 71.42 | |

| EMC-GCN# | 69.49 | 68.21 | 68.84 | 71,52 | 78.94 | 75.05 | 68.37 | 69.07 | 68.72 | 70.98 | 80.12 | 75.27 | |

| STAGE# | 80.35 | 59.7 | 68.5 | 83.98 | 71.73 | 77.37 | 77.37 | 60.62 | 67.98 | 81.88 | 72.96 | 77.16 | |

| Dual-Channel Span# | 74.74 | 70.47 | 72.54 | 72.16 | 57.6 | 64.07 | 63.48 | 50.56 | 56.29 | 72.55 | 65.49 | 68.84 | |

| SA-Transformer | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| SE-ASTE | 72.05 | 57.12 | 63.72 | 76.03 | 68.27 | 71.94 | 71.35 | 61.69 | 66.15 | 74.11 | 71.59 | 72.81 | |

| COM-MRC# | 71.51 | 69.13 | 70.3 | 76.2 | 73.74 | 74.95 | 73.00 | 70.31 | 71.64 | 74.86 | 77.63 | 76.22 | |

| BMRC | 67.12 | 56.32 | 61.22 | 74.50 | 72.48 | 73.55 | 67.12 | 60.19 | 63.51 | 69.12 | 72.14 | 70.91 | |

| DualMRC | 65.43 | 61.43 | 63.37 | 76.23 | 73.67 | 74.93 | 72.43 | 58.9 | 64.97 | 77.06 | 74.41 | 75.71 | |

| Ours | 75.51 | 67.96 | 71.54* | 79.68 | 80.97 | 80.32** | 73.60 | 69.80 | 71.66* | 77.85 | 83.76 | 80.69* | |

| ASTE | RINANTE+ | 23.10 | 17.60 | 20.00 | 31.07 | 37.63 | 34.03 | 29.40 | 26.90 | 28.00 | 27.10 | 20.50 | 23.30 |

| TSM | 40.40 | 47.24 | 43.50 | 44.18 | 62.99 | 51.89 | 40.97 | 54.68 | 46.79 | 46.76 | 62.97 | 53.62 | |

| JET | 52.00 | 35.91 | 42.48 | 66.76 | 49.09 | 56.58 | 59.77 | 42.27 | 49.51 | 63.59 | 50.97 | 56.59 | |

| GTS# | 55.93 | 47.52 | 51.38 | 70.79 | 61.71 | 65.94 | 60.09 | 53.57 | 56.64 | 62.63 | 66.98 | 64.71 | |

| EMC-GCN | 61.46 | 55.56 | 58.32 | 71.85 | 72.12 | 71.98 | 59.89 | 61.05 | 60.38 | 65.08 | 71.66 | 68.18 | |

| STAGE | 71.48 | 53.97 | 61.49 | 79.54 | 68.47 | 73.58 | 72.05 | 58.23 | 64.37 | 78.38 | 69.10 | 73.45 | |

| Dual-Channel Span# | 64.50 | 58.59 | 61.10 | 77.55 | 73.52 | 74.50 | 67.66 | 66.14 | 66.85 | 72.44 | 73.47 | 72.94 | |

| SA-Transformer | 61.28 | 48.98 | 54.44 | 70.76 | 65.85 | 68.22 | 62.82 | 58.31 | 60.48 | 72.01 | 62.87 | 67.13 | |

| SE-ASTE | 60.92 | 48.28 | 53.87 | 70.83 | 63.60 | 67.02 | 63.58 | 54.97 | 58.94 | 67.97 | 65.68 | 66.79 | |

| COM-MRC | 64.73 | 56.09 | 60.09 | 76.45 | 69.67 | 72.89 | 68.50 | 59.74 | 63.65 | 72.80 | 70.85 | 71.79 | |

| BMRC | 54.12 | 44.44 | 50.50 | 71.31 | 63.52 | 66.47 | 62.41 | 54.76 | 57.83 | 66.16 | 64.71 | 65.52 | |

| DualMRC | 57.39 | 53.88 | 55.58 | 71.55 | 69.14 | 70.32 | 63.78 | 51.87 | 57.21 | 68.60 | 66.24 | 67.40 | |

| Ours | 67.21 | 58.57 | 62.60* | 74.37 | 75.41 | 74.88* | 66.54 | 64.81 | 65.66* | 72.46 | 75.94 | 74.16* | |

Note:

Results marked with “ ” are reproduced by us, while others are taken directly from the original articles. Bold numbers indicate the best results among all methods. * and ** indicate statistically significant improvement over the best-performing baseline ( and , respectively) based on paired t-tests.

From the results, we obtain the following observations. Firstly, one notable observation is that both the end-to-end sequence labeling method and the MRC-based method outperform the pipeline method in the ASTE and AOPE tasks, which is in line with previous research (Chen, Chen & Liu, 2020a; Xu et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020a). This improvement can be attributed to the joint prediction of sub-tasks, which establishes connections between them and helps mitigate error propagation issues associated with the sequential processing of the pipeline approach. However, in the AESC task, the performance of these methods is similar to that of the pipeline method. This could be because they handle aspect entity extraction and sentiment classification as separate tasks, which may introduce mutual constraints and conflicts, resulting in performance degradation comparable to the pipeline method.

Our proposed model demonstrates competitive performance on both AESC and AOPE tasks across multiple datasets. For the AESC task, our model achieves F1-scores of 71.13%, 79.12%, 71.66%, and 78.68% on the 14lap, 14res, 15res, and 16res datasets respectively. While achieving the highest recall rates across all datasets, the model shows lower F1-scores on certain datasets, particularly underperforming against COM-MRC on the 15res dataset where our F1-score of 71.66% falls short of their 72.34%. This F1-score gap primarily results from precision-recall imbalance in scenarios with complex aspect boundaries and overlapping sentiment expressions. For the AOPE task, our model achieves F1-scores of 71.54%, 80.32%, 71.66%, and 80.69% on the respective datasets, surpassing most baseline methods. However, we observe a lower F1-score on the 14lap dataset where our model achieves 71.54% compared to Dual-Channel Span’s 72.54%, indicating challenges in the laptop domain’s technical terminology and complex aspect-opinion relationships. This F1-score deficit reflects the difficulty in balancing precision and recall when dealing with implicit sentiment expressions and domain-specific vocabulary that require deeper semantic understanding. Despite this limitation, the model demonstrates superior F1-scores on restaurant domain datasets, achieving 80.32% and 80.69% on 14res and 16res respectively.

In the ASTE task, our model surpasses the baseline on the 14lap, 14res, and 16res datasets, achieving F1-score of 62.60%, 74.88%, and 74.16%, respectively. However, on the 15res dataset, the model slightly underperforms compared to Dual-Channel Span, with an F1-score of 65.66% versus 66.85%. We attribute Dual-Channel Span’s strength to its innovative dual-channel architecture, which deeply integrates syntactic dependencies and part-of-speech features to enhance candidate span representation and selection. By explicitly incorporating structured prior knowledge, it effectively reduces redundant span interference and performs better in precision-constrained scenarios. In contrast, PromptReader’s advantage lies in its semantic-structural collaborative paradigm. It retains the guidance of syntactic features while leveraging prompt learning and interactive querying to uncover deep semantic associations. This design generally improves recall, and the dual-stage verification mechanism ensures precision stability, ultimately driving a systematic improvement in F1-score.

We also conducted quantitative statistical significance testing to verify the robustness of performance improvements. Specifically, we performed paired bootstrap resampling with 1,000 iterations on the test set F1-score between our model and each baseline. The results show that the improvements in F1-score by our model over JET and GTS are statistically significant with p-values less than 0.05. In addition, we conducted paired t-tests on per-sentence F1-score, which further confirm the superiority of our method under standard significance levels ( ). These tests increase confidence that the observed gains are not due to random variation but represent genuine performance advances.

To further understand the practicality of PromptReader, we compare its computational efficiency with several strong baseline methods. Compared to prior methods such as JET, BMRC, and Dual-MRC, PromptReader exhibits lower architectural complexity and computational cost. JET relies on autoregressive decoding, which introduces sequential dependencies during inference and increases latency. BMRC and Dual-MRC adopt multi-module or multi-stage designs, requiring separate encoders or task-specific heads, which increase the number of parameters and training overhead. In contrast, PromptReader adopts a unified encoder-based framework with a single encoder shared across all query rounds. This design avoids decoder-side computation and multi-branch structures, significantly reducing both model complexity and runtime cost. In practice, all experiments across four datasets were completed within 4 h using two RTX 3090 GPUs, demonstrating the method’s computational efficiency and scalability. Despite using multi-round prompting, our method maintains a compact parameter footprint and achieves fast convergence.

Analysis

Ablation study

To further evaluate the individual contribution of each component in our method, we perform ablation experiments and answer the following questions:

Do part-of-speech features and syntactic-dependency information improve the performance of the model?

Do two rounds of MRC queries improve the performance of aspect-opinion pair extraction?

Does prompt learning improve model performance in sentiment classification?

How much impact do different scales of BERT have on PromptReader?

How does the design complexity of prompt templates influence model performance and stability?

Effect of the part-of-speech features and syntactic-dependency information

We perform three additional experiments on the ASTE task to analyze the influence of different features on the performance of our model. The experiments include removing the Part-of-Speech feature (w/o Part-of-Speech), removing the Syntax-dependent feature (w/o Syntax-dependent), and removing both features simultaneously (w/o Pos and Sd). The results are presented in Table 3.

| Model | 14lap | 14res | 15res | 16res |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| w/o Part-of-Speech | 62.04 | 73.90 | 64.04 | 72.06 |

| w/o Syntax-dependent | 61.87 | 74.22 | 63.65 | 72.14 |

| w/o Pos and Sd | 61.42 | 73.85 | 62.97 | 71.43 |

| PromptReader | 62.60 | 74.88 | 65.66 | 74.16 |

From the table, we observe that when both the Part-of-Speech and Syntax-dependent features were removed, the model’s performance decreased by an average of 1.91% in the F1-score. When only the Part-of-Speech or Syntax-dependent feature is removed, the model’s performance decreased by an average of 1.32% and 1.35% in the F1-score, respectively. These results indicate that both the Part-of-Speech and Syntax-dependent features contribute to the overall effectiveness of our model, and their effects on performance are comparable.

The removal of the Part-of-Speech feature resulted in a slight decrease in performance, suggesting that it plays a role in enhancing the model’s understanding of word roles and meanings in sentences. Similarly, the removal of the Syntax-dependent feature also had a negative impact, indicating that it helps the model capture the relationships between words and the sentence structure, thereby improving contextual semantics.

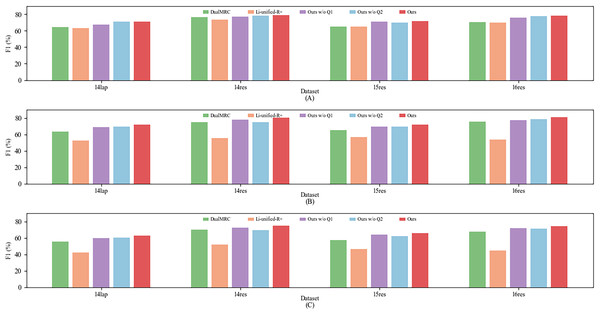

Effect of the two rounds of MRC query

We conduct two additional experiments on the AESC, AOPE, and ASTE tasks to evaluate the effectiveness of each round of MRC queries. The results are presented in Fig. 5, where “Ours w/o Q1” refers to the model without the first round of MRC queries, and “Ours w/o Q2” refers to the model without the second round of MRC queries. From the figure, it can be observed that removing the first round of MRC queries leads to a decrease in the average F1-score of the model by 2.11%, 2.72%, and 2.84% on the AESC, AOPE, and ASTE tasks, respectively. Similarly, removing the second round of MRC queries results in a decrease in the average F1-score of the model by 1.22%, 2.90%, and 3.57% on the same tasks. These findings demonstrate that both rounds of MRC queries complement each other from multiple perspectives, contributing to the accurate extraction of aspect-opinion pairs and enhancing the overall effectiveness of our model. Interestingly, even with only one round of MRC queries, our model still surpasses previous state-of-the-art methods significantly on all three tasks. This observation further highlights the performance of our framework when compared to existing approaches.

Figure 5: Experimental results of ablation study for the two rounds of MRC queries.

(A) F1-score of Aspect Extraction and Sentiment Classification (AESC) task. (B) F1-score of Aspect Opinion Pair Extraction (AOPE) task. (C) F1-score of Aspect Sentiment Triple Extraction (ASTE).Effect of prompt learning

To examine the impact of prompt learning, we conduct an additional experiment on the AESC and ASTE tasks by removing prompt learning from our model (Ours w/o prompt). The results are presented in Table 4. From the table, it can be observed that after removing prompt learning, the F1-score of the model on the AESC task decreased by an average of 1.92%, and the F1-score on the ASTE task decreased by an average of 2.46%. The obtained results demonstrate that prompt learning plays a vital role in the performance of the model.

| Datasets | AESC | ASTE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ours | Ours w/o prompt | Ours | Ours w/o prompt | |

| 14lap | 71.13 | 69.15 | 62.60 | 61.11 |

| 14res | 79.12 | 77.73 | 74.88 | 72.34 |

| 15res | 71.66 | 69.60 | 65.66 | 62.19 |

| 16res | 78.68 | 76.42 | 74.16 | 71.82 |

Prompt learning enables the establishment of connections between aspect-opinion pairs and sentiment polarity. It allows the model to integrate the local semantic information provided by aspect-opinion pairs with the global semantic information of sentences, thereby effectively predicting sentiment polarity. By stimulating the model’s potential to capture and utilize this information, prompt learning enhances the model’s predictive capabilities and leads to improved performance in sentiment prediction tasks.

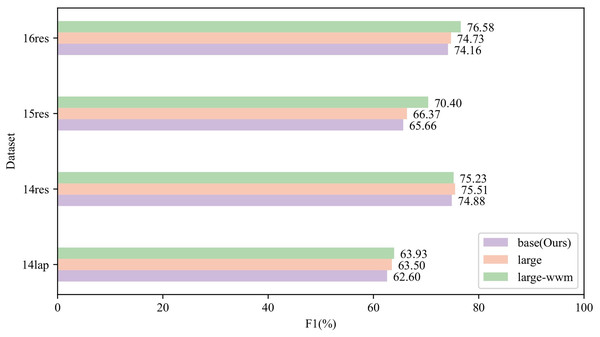

Effect of BERT encoding at different scales

To assess the influence of different sizes of pre-trained BERT models, we evaluate our framework with BERT-base, BERT-large, and BERT-large-wwm across four datasets. As illustrated in Fig. 6, larger BERT models generally lead to better performance, with the most notable gains observed on the relatively low-resource 15res dataset. Notably, even with the smaller BERT-base model, our framework achieves results that are very close to those obtained using larger variants. For example, on the 14res dataset, the BERT-base model achieves a score of 74.88%, comparable to BERT-large at 75.51% and BERT-large-wwm at 75.23%. This demonstrates that our model remains robust and competitive even when using a more lightweight backbone, offering a favorable trade-off between performance and model complexity.

Figure 6: F1-score of ablation study for the different scales BERT on ASTE task.

Effect of different prompt format combinations

To analyze the robustness of our prompt learning framework, we conduct an ablation study comparing three different combinations of prompt templates for sentiment classification. The three combinations are designed as follows:

(C1): Only a single minimal template is used, which contains no aspect or opinion information, formulated as “Sentiment: [MASK]”.

(C2): Two templates are used in this setting. The first includes only the aspect term, formulated as “The {aspect} is [MASK].” The second includes only the opinion term, formulated as “The {opinion} is [MASK]”.

(C3): Templates introduce contextual phrasing: “Considering the context, the {aspect} feels [MASK].” for aspect-only and “Considering the context, the {aspect} is {opinion}, which makes me feel [MASK].” for aspect-opinion prompts.

The results in Table 5 show that the (C1), which contains no aspect or opinion information, yields the lowest F1-score, indicating that minimal prompt guidance limits performance. Incorporating only the aspect term or the opinion term in templates (C2) significantly improves performance over the (C1), demonstrating the importance of aspect and opinion information. The contextual combination (C3), which introduces more complex phrasing, performs worse than ours on ASTE by 1.43 F1 points representing a 1.9% relative degradation. Our original achieves the best performance on both AESC and ASTE tasks, with statistically significant improvements ( ) over all other variants. These findings confirm the robustness and effectiveness of our dual-prompt design, which balances explicit opinion incorporation with linguistic simplicity.

| Prompt Template | AESC | ASTE |

|---|---|---|

| C1 | 71.21 | 69.80 |

| C2 | 73.56 | 72.10 |

| C3 | 73.61 | 73.45 |

| Ours | 79.12 | 74.88 |

Case study

To further illustrate the advantages of our proposed method, we conduct detailed case studies comparing our model with two strong and representative baselines, JET and GTS. These baselines embody two prevalent paradigms in the ASTE task with distinct technical characteristics: JET employs an autoregressive sequence generation strategy that processes triplets sequentially from left to right, making it susceptible to error propagation and difficulty in handling overlapping relationships; GTS utilizes a table-filling framework with fixed position embeddings that struggles with flexible aspect-opinion associations and complex syntactic dependencies. Table 6 presents examples of prediction results from all three models on representative test sentences, where incorrect predictions are consistently marked with red crosses to highlight performance differences.

| Sentence | JET | GTS | Ours |

|---|---|---|---|

| So about the prawns, they were fresh and had a slight crispiness about the batter. Soooo good, the walnuts were cut in smaller pieces and very crunchy and tasty. | (prawns, fresh, pos) (walnuts, tasty, pos) [Missing: (batter, crispiness, pos)] [Missing: (walnuts, crunchy, pos)] | (prawns, fresh, pos) (prawns, good, pos) × (prawns, tasty, pos) × [Missing: (batter, crispiness, pos)] [Missing: (walnuts, crunchy, pos)] | (prawns, fresh, pos) (batter, crispiness, pos) (walnuts, crunchy, pos) (walnuts, tasty, pos) |

| The music is great, no night better or worse, the bartenders are generous with the pouring, and the lighthearted atmosphere will lift your spirits. | (music, great, pos) (tenders, generous, pos) × [Missing: (atmosphere, lighthearted, pos)] | (music, great, pos) (atmosphere, lighthearted, pos) [Missing: (bartenders, generous, pos)] | (music, great, pos) (bartenders, generous, pos) (atmosphere, lighthearted, pos) |

| Nice ambience, but highly overrated place. | (ambience, nice, pos) (place, overrated, pos) × | (ambience, nice, pos) (place, overrated, pos) × | (ambience, nice, pos) (place, overrated, neg) |

| The chef clearly has a way with flavors, though I might find the music a bit much. | (chef, has way with flavors, pos) [Missing: (music, a bit much, neg)] | (chef, way with flavors, neu) × (music, much, pos) × | (chef, has way with flavors, pos) (music, a bit much, neg) |

| While I could have done without the youth who shared the evening with us, our wonderful server and food made the experience a very positive one. | (server, wonderful, pos) (food, positive, pos) × [Missing: (experience, positive, pos)] | (server, wonderful, pos) (food, positive, pos) × [Missing: (experience, positive, pos)] | (server, wonderful, pos) (food, made experience positive, pos) (experience, positive, pos) |

Note:

Incorrect predictions are marked with a red cross (×), and missing triplets are indicated by [Missing].

We selected five representative sentences from the 16res test set, each posing distinct linguistic challenges such as complex grammatical constructions linking aspect terms and opinion expressions, one-to-many and overlapping correspondences, multiple sentiment polarities within a sentence, and implicit sentiments.

The results demonstrate that our model consistently recovers more correct aspect-opinion-sentiment triplets and more accurately identifies sentiment polarity compared to the baseline methods.

In the first sentence, which contains four triplets, JET identifies only two correct triplets, namely (prawns, fresh, pos) and (walnuts, tasty, pos), failing to capture the aspect-opinion pairs associated with “batter” and “crunchy” due to limitations inherent in sequential generation. GTS exhibits more errors, producing incorrect aspect-opinion associations by linking “good” and “tasty” with “prawns,” where “good” refers to the overall experience and “tasty” specifically describes “walnuts.” This illustrates that the table-filling framework employed by GTS struggles with complex grammatical constructions involving multiple interleaved aspects and opinions. In contrast, our model successfully identifies all four triplets by leveraging syntactic dependency features to parse the sentence structure accurately and correctly associate each opinion with its corresponding aspect.

The second sentence highlights boundary detection challenges. JET truncates “bartenders” to “tenders” due to subword tokenization issues in autoregressive generation and fails to predict the (atmosphere, lighthearted, pos) triplet. GTS correctly identifies the atmosphere-related triplet but completely misses the bartenders-related triplet. Our model accurately captures the full aspect terms and predicts all relevant triplets through precise boundary detection enabled by the MRC-based querying strategy.

In the third sentence, both baseline models correctly extract the aspect-opinion pair (place, overrated) but misclassify its sentiment as positive. This error arises because the models fail to fully leverage the local context of the aspect-opinion pair when determining sentiment, as evidenced by the incorrect polarity assignment despite correctly identifying the pair. Our model, in contrast, correctly predicts the negative polarity, demonstrating that the prompt-based sentiment inference mechanism effectively integrates local semantic cues from the aspect-opinion pair for accurate sentiment classification.

The fourth sentence presents challenges associated with implicit sentiment expressions. JET identifies the positive sentiment in “has a way with flavors” but completely omits the negative triplet (music, a bit much, neg), failing to detect the implicit criticism. GTS produces more severe errors, misclassifying the clearly positive idiomatic phrase “has a way with flavors” as neutral and incorrectly interpreting “a bit much” as positive. By contrast, our model successfully captures the implicit positive sentiment conveyed by the idiomatic expression and correctly identifies the negative sentiment, indicating superior handling of non-literal and context-dependent expressions.

The fifth sentence involves complex syntactic relationships, where “food made the experience positive.” Both baseline models incorrectly extract (food, positive, pos), failing to recognize that the sentiment “positive” applies to the “experience” rather than directly to the “food.” Consequently, JET and GTS omit the crucial triplet (experience, positive, pos), highlighting their inability to handle long-distance dependency relations between aspects and opinions. Our model correctly identifies both (food, made experience positive, pos) and (experience, positive, pos), demonstrating enhanced syntactic comprehension through the dependency-aware MRC framework.

To complement this qualitative analysis, we further categorize and quantify error types made by baseline models and our method. Based on predictions over the entire 16res test set, we manually annotated a random sample of 100 incorrect predictions per model and classified them into four major error types:

(E1) Missing Triplet: Aspect-opinion-sentiment triplet is completely missing. (E2) Polarity Misclassification: Aspect-opinion pair is correctly predicted, but sentiment polarity is incorrect. (E3) Boundary Error: The predicted aspect or opinion span is partially incorrect (e.g., incomplete or overlapping). (E4) Implicit/Idiomatic Error: The triplet involves idioms or implicit sentiment, and is missed or misinterpreted.

The distribution of error types is shown in Table 7.

| Model | E1: Missing | E2: Polarity | E3: Boundary | E4: Implicit/Idiom |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JET | 47% | 28% | 17% | 8% |

| GTS | 43% | 25% | 21% | 11% |

| Ours | 22% | 15% | 14% | 7% |

The results indicate that our method significantly reduces the proportion of missing triplets and polarity misclassifications compared to the baselines. Notably, implicit and idiomatic errors remain challenging for all models, though our model achieves the lowest error rate of 7% in this category representing a 4% reduction compared to GTS. These findings suggest that our multi-round querying and prompt-based sentiment inference enhance both span-level extraction and sentiment understanding, especially in nuanced cases.

Conclusions and future work

In this article, we introduce a novel multi-turn MRC framework that incorporates prompt learning for the ASTE task. Our model consists of three rounds of queries, where the first two are designed as MRC tasks to identify aspect-opinion pairs, and the final round is formulated as a prompt learning task to predict sentiment polarity. To enhance contextual semantic understanding, we integrate linguistic features such as part-of-speech tags and syntactic dependency information. Additionally, to address the sparsity issue in traditional prompt learning, we utilize an MLP layer to process the output of the final [MASK] token. Extensive experiments conducted on four benchmark datasets demonstrate that our proposed framework outperforms existing state-of-the-art methods.

For future work, we plan to extend our multi-turn MRC framework with prompt learning to related tasks such as relation extraction and general sentiment analysis. We will also explore ensemble prompt learning and reinforcement learning strategies to further enhance triplet extraction performance. However, we acknowledge a key limitation of our current work—namely, that all experiments are conducted on English datasets. As such, the generalizability of our model to low-resource and non-English languages remains uncertain. To address this, future research will investigate the cross-lingual adaptability of our approach through multilingual pretraining, transfer learning, and the design of language-specific prompts.