GastroNet: a novel framework for detection and classification of stomach cancers

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Nicole Nogoy

- Subject Areas

- Computer Vision, Data Mining and Machine Learning, Neural Networks

- Keywords

- Gastrointestinal, Stomach cancer, Lightweight models, Computer vision

- Copyright

- © 2026 Raza et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2026. GastroNet: a novel framework for detection and classification of stomach cancers. PeerJ Computer Science 12:e3432 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3432

Abstract

The human gastrointestinal (GI) system is vulnerable to various diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease, peptic ulcers, and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Endoscopy is the conventional method used to assess the gastrointestinal tract. An ordinary endoscopy session necessitates the identification of several diseases, which is a monotonous and lengthy process to complete manually. Computer-aided diagnostic systems have been employed to help doctors analyze data. However, they may need a more refined technique due to the limitations of feature extraction procedures. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) reveal promise but have necessitated extensive resources, making them inappropriate for real-time diagnosis in resource-constrained conditions. This article has presented GastroNet, an efficient approach to classifying stomach cancer using endoscopic images. GastroNet utilizes ShuffleNet to extract features and a Feature Pyramid Network to handle images of varying sizes. GastroNet is then combined with NanoDet for detection and classification. The outcomes on the Hyper Kvasir dataset demonstrate that GastroNet achieves a mean accuracy of 97.3%. This high accuracy rate signifies excellent functionality in comparison to other deep-learning-based models. Additionally, GastroNet operates rapidly by processing videos at 97 frames per second, enabling real-time clinical diagnosis.

Introduction

The human gastrointestinal (GI) system is vulnerable to a diverse range of disorders, including inflammatory bowel disease (Baumgart & Carding, 2007), peptic ulcers (Lanas & Chan, 2017), gastroesophageal reflux disease (gerd) (Clarrett & Hachem, 2018), and polyps (Goddard et al., 2010), which affect a substantial proportion of the population in Asia. Reports indicate a significant rise in the occurrence of stomach cancers in South Korea and Japan, with over 41% of identified cancer cases originating from China (Goh, 2007). Annually, over 800,000 fatalities occur as a result of stomach cancer in Pakistan (Daniyal et al., 2015). In the US, the gastrointestinal system accounted for 36.8 million outpatient appointments and 43.4 million visits; a diagnosis of the gastrointestinal system was the primary reason for the visit (Beatty, Cherry & Hsiao, 2010).

With this increasing disease burden, the early detection and proper diagnosis of the disease are essential in enhancing patient survival. Manual interpretation of endoscopes, however, is time-consuming, expertise-dependent, and subject to inter-observer variability. Computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) systems can be beneficial in this regard, enabling clinicians to detect abnormalities more quickly and reliably.

Scientists have developed various computer-aided diagnostic (CAD) systems that impulsively diagnose and detect diseases to assist doctors. For instance, Bidokhet (Bidokh & Hassanpour, 2023) introduced a method that utilizes wireless capsule endoscopy (WCE) images to detect tumors in the digestive system automatically. Lv, Yan & Wang (2011) developed an automated process that uses novel descriptors to combine color and spatial information to detect bleeding patterns in WCE images. Although automated models have shown some success in identifying diseases automatically, a significant gap remains in achieving a high level of accuracy.

Several factors, including engineered features such as shape, texture, and color, may contribute to this gap (Aamir et al., 2021). These models rely on manually extracted features, which makes them highly sensitive to changes in illumination, size, and orientation of patterns. As a result, they are unable to detect complex patterns, which can lead to inaccurate classification. Moreover, the extraction of these manual features necessitates trained subject knowledge and a steep computer expense. Nevertheless, when applied in practice for endoscopic image diagnostics, these models have consistently failed to deliver high accuracy. Medical imaging applications, such as image recognition, object detection, and semantic segmentation, have demonstrated the suitability of utilizing convolutional neural networks (CNNs). CNNs are a feature extractor in their simplest form.

Furthermore, several other advanced deep models have been employed for endoscopic image classification (Ahmad et al., 2017; Thambawita et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2015; Gamage et al., 2019). However, these models are computationally intensive and require a significant amount of computational power, which limits their applicability for real-time diagnosis. Developing countries are often burdened by healthcare systems that are stretched to the limit due to a lack of high-performance computing resources, a significant problem in densely populated urban areas. Therefore, it is crucial to have a model that can function in real-time, consumes little memory, and provides efficient and accurate results.

This article presents a practical framework for classifying stomach cancer from endoscopic images, enabling rapid diagnosis. The proposed method employs an effective neural network (NN) model that can learn relevant features from endoscopic images with low complexity.

The significant contributions of this article are:

Enhance the diagnostic performance and decrease errors in detecting and diagnosing gastric lesions.

Real-time diagnostics using a lightweight model to identify, locate, and categorize stomach lesions in endoscopic images.

An effective system that requires little computing power to extract pertinent characteristics from endoscopic pictures.

Help physicians make wise choices and enhance patient outcomes.

The rest of this article is organized in the following sections. In “Literature Review”, related work is discussed thoroughly. “Methodology” describes the proposed methodology for this study. In “Experimental Setup”, the experimental setup and experimental results are presented. “Conclusion” concludes the article.

Literature review

In recent years, significant research work has been conducted in endoscopy image classification, with several approaches being presented to tackle this complex challenge. Deep learning methods have demonstrated encouraging outcomes in classifying stomach cancers. However, most of these methods depend on extensive and computationally demanding models.

Wang et al. (2015) introduced a computer-based method of detection of polyps by a rule-based classifier and edge-cross-section appearance features. This method can be used to follow the same polyp edge in a series of images. A major and groundbreaking change in the area was the replacement of rule-based systems with advanced deep learning models. Dense-Net-201 was used by Gamage et al. (2019) to accurately classify different gastrointestinal tract conditions, which resulted in a vast enhancement of the accuracy. A GoogLeNet-based method was applied by Takiyama (2018) to provide the robot classification of anatomical features in a huge dataset of esophagogastroduodenoscopy images. Their study proved that they targeted vital gastrointestinal regions with remarkable precision.

Further work was carried out by Shichijo (2017) and Byrne et al. (2019), who specifically trained CNN models for particular diagnostic purposes. They concentrated on the instant examination of colorectal polyps based on video acquisition from narrowband imaging (NBI) video frames. Zhang et al. (2017) presented a unique approach that used transfer learning to implement a CNN pre-trained on non-medical images. Thus, it generally allows for the inference of information from non-medical domains into endoscopy, significantly reducing the medical label data required. Their approach enables the effective transfer of knowledge from non-medical fields to medicine, making it unnecessary to collect large quantities of accurately annotated medical data. Furthermore, recent research has focused on significantly improving deep-learning models to meet and address the domain’s requirements. For example, Song et al. (2020) developed a computer-aided diagnosis system based on a 50-layer deep convolutional neural network. It reliably exceeded human experts in identifying histology within colorectal polyps. Guo et al. (2024) and Jung (2012) proposed innovative approaches to address the issues of class imbalance and complex sampling by introducing new loss methodologies. To prevent excessive emphasis on the junction of the digestive tract, Wang, Yang & Tang (2022) integrated a convolutional neural network (CNN) with a capsule network. This combination included lesion-aware feature extraction to enhance attention to the relevant areas.

Mohapatra et al. (2023) suggested utilizing an empirical wavelet transform to extract frequency components from endoscopic data before employing a CNN model for training and testing. Kim et al. (2023) introduced UC-DenseNet, which integrates CNN and recurrent neural network (RNN) with an enhanced attention mechanism to highlight feature information by facilitating communication across different channels. On the other hand, various contributions are employed to identify and classify anomalies in specific benchmark datasets. The Hyper Kvasir (Pogorelov, 2017a) dataset is used to apply several techniques. The dataset consists of ten classes, each with equal samples. The Speech Communication Laboratory-University of Maryland (SCL-UMD) technique, proposed by Agrawal et al. (2017), utilizes two distinct deep-learning models with manually designed features. The method resulted in a detection accuracy of 0.96 and an F1-score of 0.85, both considered outstanding. The Visual Geometry Group (VGG) (Szegedy, 2015) and Inception (Szegedy et al., 2016) deep learning algorithms significantly slow down and reducing its speed to 1.3 frames per second (FPS) (Jha, 2021). The SIMULA-17 (Pogorelov, 2017b) achieves a higher FPS rate for detection by utilizing a Logistic model tree classifier on the handmade features. The method led to a marginally reduced level of precision, accompanied by a detection rate of 46 frames per second. The F1-score of the technique is 0.78 when applied to the Kvasir dataset (Pogorelov et al., 2017). Ho Chi Minh City University of Science (HCMUS) (Pogorelov et al., 2018) utilized the faster R-CNN model to detect irregularities in the Kvasir V2 dataset, which contains varying sample sizes for each class. This approach was chosen due to the current advancements in deep learning, particularly in object detection. The strategy yielded an enhanced F1-score of 0.93 while maintaining a speed of 23 frames per second (FPS). Using only texture features exhibited an F1-score of 0.75, along with real-time detection (Khan & Tahir, 2018). Zhao et al. (2021) used a deep neural network and handcrafted features to diagnose GI diseases accurately.

In the literature, authors note that deep learning has the potential to aid in the diagnosis of gastrointestinal problems, with some models achieving high accuracy rates. However, most existing models use computationally intensive architectures, e.g., DenseNet, VGG, Inception, and faster R-CNN, which cannot be used in real-time and resource-constrained applications. Others trade precision for speed, using manually designed features that are less robust against complex variations in endoscopic images. Furthermore, the imbalance between classes and the need for large-scale, annotated medical data pose additional challenges. Thus, it is evident that a lightweight, efficient, and precise deep learning structure is needed that can address these issues and allow real-time implementation in a clinical setting.

Methodology

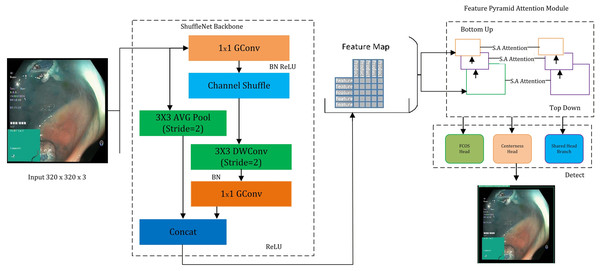

This study presents a novel “GastroNet” architecture for the detection and categorization of gastrointestinal diseases. GastroNet uses computer vision and deep learning techniques to identify and classify GI diseases using endoscopic images. Initially, a variety of GI endoscopic images from the Hyper Kvasir dataset were used to train GastroNet. ShuffleNet then uses input images to extract features. The Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) receives the extracted features to improve detection efficiency and handle objects of various sizes. The detection head of the Nanodet model uses FPN output to identify and predict classes. The suggested framework’s outline is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: An overview of the proposed GastroNet framework.

Image source credit: Borgli et al. (2020).Hyper Kvasir

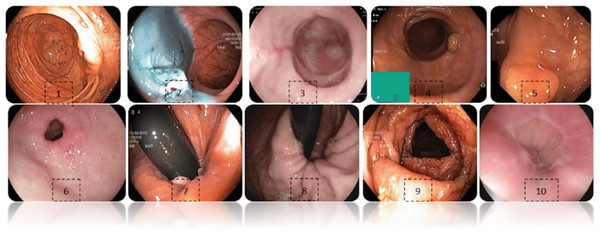

The Hyper Kvasir dataset (Pogorelov, 2017a) contains an extensive gastrointestinal endoscopy images. The data is composed of 10,662 images of different gastrointestinal diseases (932 z-line images, 193 ulcerative colitis images, 403 esophagitis images, 1,000 pylorus images, 1,020 polyps images, 764 retroflex-stomach images, 394 retroflex-rectum images, 131 impacted-stool images, 1,002 dyed-lifted-polyps images, and 10). In Fig. 2, sample images for each class are displayed. Images from several modalities, such as chromoendoscopy, narrow band, and white light, are included in the data. The annotations include bounding boxes and class labels on the images, enabling object detection and classification tasks. Despite the number of all annotated classes in the dataset being 23, several of them have tiny numbers of samples, so in this research, we chose the 10 most representative and with enough samples to provide equal training and valid evaluation. The data is divided into testing (10%), validation (10%), and training (80%) data. The images were resolved to 320 × 320 and forwarded to ShuffleNet to extract features. The dataset is available on: “https://datasets.simula.no/hyper-kvasir/”.

Figure 2: Exhibits images from each class of hyper kavsir dataset, labelled as Cecum (1), Dyed lifted polyps (2), Esophagitis (3), Impacted stool (4), Polyps (5), Pylorus (6), Retroflex rectum (7), Retro-lex-stomach (8), Ulcerative colitis (9), (10) Z- line. (Jung et al., 2022).

Image source credit: Borgli et al. (2020).Preprocessing

The dataset used in this study was preprocessed before the training to achieve consistency and enhance generalization. The size of each image was reduced to 320 × 320 pixels and normalized to [0,1] to normalize pixel intensity values. As well, data-augmentation methods were dynamically used during training to control overfitting and tolerance to adaptation to changes in acquisition conditions. In particular, the augmentation pipeline consisted of random horizontal and vertical flips, random rotations within a range of ±15°, brightness and contrast manipulation of up to ±20%, and random cropping with up to 10% variance. These extensions introduce real-world variability in orientation, illumination, and scale, enabling the model to generalise more effectively to a wide range of clinical settings.

Moreover, it was divided into training, validation, and testing subsets in a 8:1:1 proportion. To prevent the problem of class imbalance, care was taken to ensure the distribution of classes was comparable among all subsets. The training set was augmented, while the validation and testing sets remained unchanged, to gain a clear perspective on model performance.

ShuffleNet

To extract features, a lightweight convolutional neural network, ShuffleNet, was employed (Zhou et al., 2018; Raza et al., 2024). The ShuffleNet architecture reduces computational complexity while maintaining accuracy, making it ideal for real-time object detection. This design relies on Shuffle Unit, Group Convolution, and Channel Shuffle operations. The Shuffle Unit is a fundamental component of ShuffleNet that has three layers: (i) a convolutional layer, (ii) a channel shuffle operation, and (iii) a depth-wise separable convolution. Furthermore, group convolution may be characterized as a convolutional layer in which filters are grouped. This approach reduced the computational cost while preserving the capacity to learn features. The Channel Shuffle method replicates the three components of the Convolution Layer, Channel Shuffle, and Depthwise Separable Convolution, as described by Eqs. (1), (2), and (3), respectively.

(1)

(2)

(3) where X is the input, W is the weight, b is the bias, and σ is the activation function. Shuffle is the channel shuffle operation. Wd is the depthwise convolutional weight, and bd is the bias.

The choice of ShuffleNet as a feature extractor was led by several considerations. First, adopting a lightweight architecture and group convolutional layers effectively reduces the computational resources required. Furthermore, ShuffleNet has frequently achieved excellent accuracy (Tesfai et al., 2022; Al-Haija, 2022; Li & Lv, 2020), which makes it the best option for feature extraction tasks. ShuffleNet’s modular architecture facilitates seamless integration with different models. The NanoDet model effectively and accurately detects and classifies gastrointestinal diseases in endoscopic images using ShuffleNet as the feature extractor.

Feature pyramid network (FPN)

The Feature Pyramid Network, which handles objects of varying scales and significantly enhances object detection accuracy across a broad range, is employed. The FPN includes a lower-level path that extracts features at a broad range of scales and distinct evolutionary times and an upper-level extension path that contains standing connections to generate multi-scale features. Subsequently, the combined multi-scale characteristics are employed for object detection at multiple levels of detail.

The bottom-up path originates from the terminal point of the backbone network. Equation (4) represents the bottom-up pathway.

(4)

Here, Ci represents the feature map at Scalei. For each feature map, a series of convolutional layers Conv is applied. The top-down pathway begins with the highest-resolution feature map and gradually reduces resolution while fusing information from higher to lower scales. The top-down path is represented by Eqs. (5) and (6).

(5)

(6) where is the resolution feature map, and is the unsampled feature map. Combine the upsampled feature map with the feature map from the previous level through lateral connections. , represents a convolutional layer in a lateral connection. Both top-down and bottom-up information are then integrated to gain the multi-scale fused characteristics. Feature fusion is represented by Eq. (7).

(7)

Here, is a convolutional layer that is employed as a feature fuser. The multi-scale features are merged as in which holds information from lower and higher scale features.

NanoDet

NanoDet predicts bounding boxes, object classes, and confidence scores for detected objects. It often consists of several convolutional layers followed by anchor box regression and object classification layers. The object classification layers predict the probability scores for each anchor box belonging to different object classes. This step involves applying a Softmax activation function to obtain class probabilities represented in Eq. (8). The anchor boxes are predefined bounding boxes of varying aspect ratios and scales used for object localization during training and inference. The confidence scores represent the certainty or confidence level that a predicted bounding box contains an object of a specific class. They are calculated as the product of the predicted class probabilities and the abjectness scores. The confidence score is represented in Eq. (9).

(8)

(9) where Pclass represents the predicted class probabilities, and Convclass denotes the convolutional layers dedicated to object classification.

A modified NanoDet with Feature Pyramid Attention Module (FPAM) is proposed in this study. This module helps the model concentrate on key aspects and increase accuracy by limiting unnecessary input. The attention mechanism works like a spotlight, focusing only on the most essential features in the image. It enhances the model’s ability to detect objects accurately by highlighting essential features while suppressing irrelevant information. FPAM operates based on an attention mechanism similar to humans. Humans focus their attention on specific parts of an image when recognising objects. FPAM consists of three matrices: (i) query matrices extract the essential features that need attention, (ii) key features are used to compute the attention scores, and (iii) value matrices contain the actual features that received the highest attention scores, for the calculation of the attention score, presented in Eq. (10).

(10) where Qi is the Query matrix, Ki is the Key matrix, Vi is the Value matrix, and dk represents the dimension of the key vectors. The Softmax function normalizes the attention scores to ensure they sum up to 1, indicating the relative importance of each feature. The overall methodology is presented in Algorithm 1.

| 1. Input: |

| I: Endoscopic image dataset (Hyper Kvasir dataset) |

| N: Number of training iterations |

| B: Batch size |

| L: Initial learning rate |

| S: Step size for the warm-up training phase |

| T: Total time taken for FPS calculation |

| 2. Preprocessing: |

| Split I into training (Itrain), validation (Ival), and testing (Itest) sets with a ratio of 7:2:1: |

| I = {Itrain, Ival, Itest} |

| Resize images in I to W × H pixels: |

| I′ = {resize(I, W, H)} |

| Normalize image pixel values in I′: |

| I″ = {normalize(I′)} |

| 3. Training: |

| Initialize GastroNet model with ShuffleNet as feature extractor: |

| F = ShuffleNet (I″) |

| Use Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) to handle objects of varying sizes: |

| P = FPN (F) |

| Use NanoDet with Feature Pyramid Attention Module (FPAM) for object detection and classification: |

| D = NanoDet (P) |

| Train GastroNet with Itrain for N iterations with a batch size of B: |

| where L is the loss function, yi is the ground truth label, and θ is the model parameter. |

| Dynamically adapt learning rate using cubic spline interpolation and cosine annealing: |

| L′ = L· α(t) |

| where α(t) is the learning rate schedule. |

| 4. Evaluation: |

| Accuracy: |

| Recall: |

| Precision: |

| F1-score: |

| FPS: Frames Per Second |

| Calculate (mAP): |

| where AP is the average precision for each image. |

| 5. Output: |

| Output images with class labels (C) and bounding boxes. |

| Performance metrics (M ) = (A, R, P, F1 , FPS, mAP) |

Experimental setup

The experiments were conducted using the PyTorch deep learning framework in Python (Imambi, Prakash & Kanagachidambaresan, 2021). The training environment was based on a system running the Windows 10 operating system, equipped with an AMD Ryzen 7 5800X processor and an NVIDIA RTX 3080 Ti 12 GB graphics card. The dataset was partitioned into training, test, and validation sets with a ratio of 7:2:1. The training process commenced with an initial learning rate of 0.001. Before the main training, a warm-up phase with a step size of 7 was executed. The learning rate was adjusted using dynamic cubic spline interpolation (Huang et al., 2020) and cosine annealing (Johnson et al., 2023). Training was performed over 500 iterations with a batch size of 48, and the input images were resized to dimensions of 320 × 320. A summary of the training parameters is provided in Table 1.

| Framework parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Epochs | 500 |

| Batch size | 48 |

| Learning rate | 0.001 |

| Image size | 320 × 320 |

Evaluation parameters

In the evaluation, a complex framework of metrics should be used to provide an accurate reflection of the strengths and weaknesses of deep learning models. Equations (11), (12), (13), (14) demonstrate how the model is assessed using the performance metrics of accuracy, recall, precision, and F1-score, respectively.

(11)

(12)

(13)

(14)

Frames per second (FPS) is a metric that quantifies the model’s ability to react to real-time detection and classification. It is a metric of the frame rate of an animation or video. FPS is the rate of presentation of a sequence of still images (frames) during a single second that produces the illusion of motion or animation. The FPS is calculated by Eq. (15).

(15)

Experimental setup

The suggested model, GastroNet, is tested and justified through different approaches. The subsections below offer a detailed explanation of the experiment outcomes.

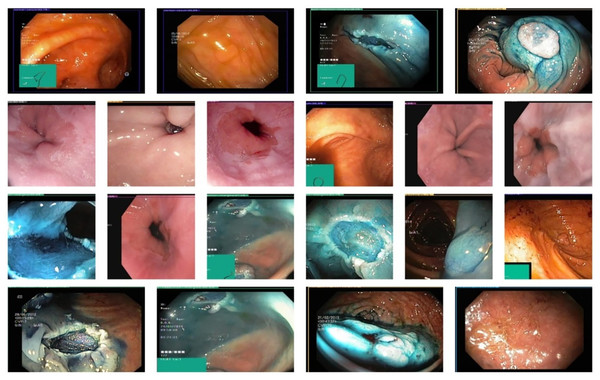

Stomach cancer localization results

A proper system of detecting stomach cancer should be able to localize lesions effectively. An experiment was conducted to evaluate the gastric localization performance of the proposed GastroNet framework using random test images from the Hyper-Kvasir database. The results obtained in the localization process were illustrated in Fig. 3. The results show that GastroNet is effective in detecting stomach lesions under complex background conditions (i.e., varying orientations and acquisition angles). Additionally, the system is effective in identifying lesions of varying sizes, shapes, and colors. To evaluate objectively the localization of gastric lesions, the Mean Average Precision (mAP) was calculated. GastroNet achieves a high mAP of 0.9634, indicating that the framework is effective in localizing gastrointestinal lesions in a complex dataset.

Figure 3: Proposed GastroNet localization results on Hyper Kvasir dataset.

Image source credit: Borgli et al. (2020).GastroNet classification results

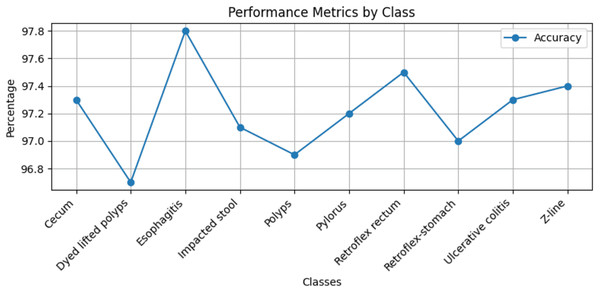

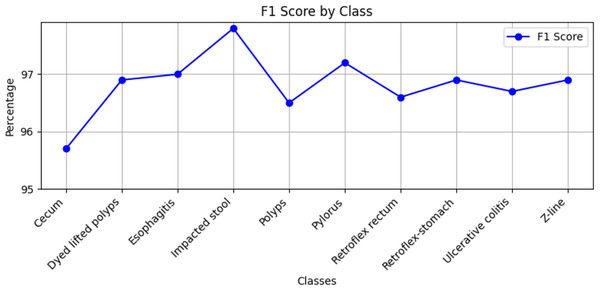

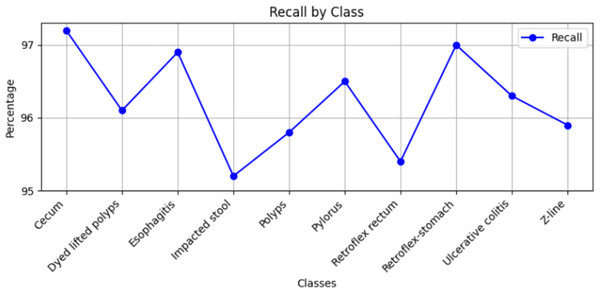

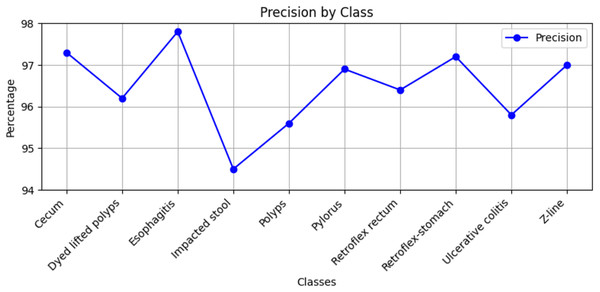

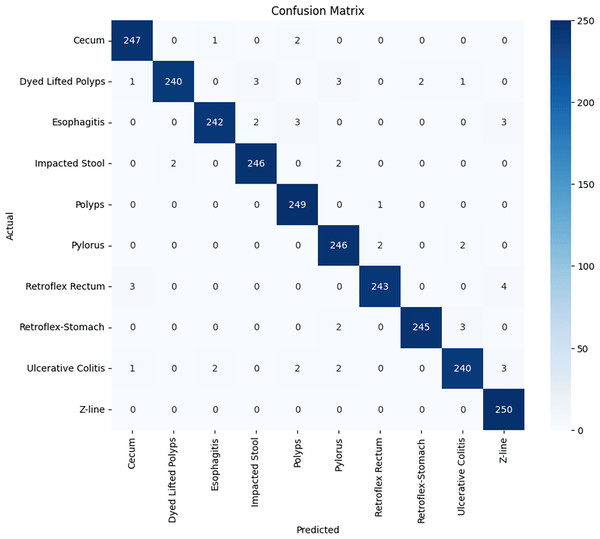

Stomach cancers should be classified accurately to help clinicians determine the most effective treatment. The GastroNet framework was tested on ten classes of lesions that exist in the HyperKvasir dataset. The model was evaluated using test data with standard measures of accuracy, F1-score, recall, and precision, and the results are presented in Figs. 4, 5, 6, and 7, respectively. GastroNet was proven to be very effective, with an average accuracy of 97.3%, a recall of 96.4%, a precision of 97.0%, and an F1-score of 96.8%. This good performance is also demonstrated in the confusion matrix in Fig. 8. Therefore, the findings confirm that GastroNet is highly effective in classifying gastric lesions.

Figure 4: Accuracy values of GastroNet.

Figure 5: F1-score values by GastroNet.

Figure 6: Recall values by GastroNet.

Figure 7: Precision values by GastroNet.

Figure 8: GastroNet confusion matrix on ten classes of hyperkavsir dataset.

Ablation study

We conducted an ablation study within the proposed GastroNet framework to assess the contribution of each architectural element. Precisely, we compared the performance: (i) ShuffleNet as a standalone feature extractor using a bare classification head, (ii) ShuffleNet using FPN but no FPAM, (iii) ShuffleNet using NanoDet but no FPN, and (iv) the full GastroNet with ShuffleNet, FPN, NanoDet, and FPAM. The models were evaluated using accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and mean average precision (mAP). Findings indicated that the absence of the FPN resulted in a significant decrease in localization accuracy, with a 6.8% reduction in mAP. Comparatively, the lack of FPAM resulted in a 3.5 percent decrease in total classification accuracy due to the absence of feature attention. The setup that lacked NanoDet exhibited poor performance in detecting multi-class lesions. Table 2 provides the entire outcome of the ablation study.

| Configuration | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1-score (%) | mAP (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ShuffleNet + Simple head | 90.1 | 89.0 | 88.6 | 88.8 | 84.0 |

| ShuffleNet + FPN (no FPAM) | 93.8 | 93.1 | 92.6 | 92.8 | 95.2 |

| ShuffleNet + NanoDet (no FPN) | 92.2 | 91.4 | 90.8 | 91.1 | 89.5 |

| Full GastroNet (ShuffleNet + FPN + FPAM + NanoDet) | 97.3 | 97.0 | 96.4 | 96.8 | 96.34 |

Performance comparison with other deep learning models

To identify targets efficiently, accurate and representative features are necessary. The effectiveness of the proposed GastroNet framework is compared with other deep feature extraction algorithms, such as ResNet-50, DenseNet-201 (Alhajlah, 2023), AlexNet (Cuevas-Rodríguez, 2023), ResNet-102 (Narasimha Raju et al., 2022), ResNet-101, Inception-v3, SCL-UMD (Agrawal et al., 2017), and EfficientNet (Tan, Pang & Le, 2020), to determine how it works in detecting and classifying stomach cancer. The results of accuracy, presented in Table 3, show that GastroNet outperforms all the deep learning frameworks, achieving the highest accuracy of 97.3%.

| Method | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|

| SCL-UMD | 96 |

| Inception-V3 | 95.9 |

| ResNet-101 | 96.4 |

| AlexNet | 94.9 |

| DenseNet-201 | 87.1 |

| ResNet-50 and ResNet-102 | 96.43 |

| EfficientNet | 66.78 |

| GastroNet | 97.3 |

As indicated in Table 3, GastroNet proves to be the most reliable model for stomach cancer diagnosis, with an accuracy of 97.3%, surpassing other models whose accuracies range from 66.78% to 96.4%. This high performance can be traced to some of its architecture and design. To start with, GastroNet has a specialised architecture that is capable of detecting cancer in the stomach, and in this case, accurately identifying the cancerous areas as a result of optimising the detection and interpretation process of complex endoscopic images. Additionally, the model employs the latest mechanisms, including the Feature Pyramid Attention Module (FPAM), which highlights the most significant features and eliminates noise, thereby enhancing the object detection accuracy and system efficiency.

Another essential feature of GastroNet is its high processing speed, which has been guaranteed without compromising accuracy. This accuracy is crucial in the clinical context, where a prompt and precise diagnosis is essential. Through the comparison of the model with other state-of-the-art models in terms of frames per second (FPS), as shown in Table 4, the model’s ability to identify objects in real-time is also confirmed.

| Model | Backbone | Speed (FPS) |

|---|---|---|

| EfficientNet (Ren et al., 2015) | EfficientNet | 35.00 |

| Faster R-CNN (Lin et al., 2017) | ResNet50 | 8.00 |

| RetinaNet (Redmon & Farhadi, 2018) | ResNet50 | 16.20 |

| RetinaNet (Redmon & Farhadi, 2018) | ResNet101 | 16.80 |

| YoloV3 (Bochkovskiy, Wang & Liao, 2020) | DarkNet53 | 45.01 |

| YoloV4 (Raza & Iqbal, 2025) | DarkNet53, CSP | 48.00 |

| GastroNet | ShuffleNetV2 | 97.00 |

Conclusion

In this study, a novel model, GastroNet, will be developed and tested as a lightweight model. It is aimed at identifying and classifying stomach cancer. The detection and classification accuracy of GastroNet was tested, and its performance was compared to that of other popular deep learning algorithms, indicating the best performance. The results showed that GastroNet performed better than the other models tested, based on both processing speed and the accuracy of localization and classification. The localization results indicate that GatroNet is capable of detecting stomach lesions successfully, even under adverse conditions such as various image orientations and acquisition angles. The mAP score of 0.9634 means the ability to accurately identify lesions of varying sizes, shapes, and colors in endoscopic images. GastroNet performed exceptionally well, achieving an average classification accuracy of 97.3, along with high recall, precision, and F1-scores. These findings demonstrate that the model is effective in classifying various types of stomach lesions, enabling physicians to make the most appropriate decisions. The quality of GastroNet is evidenced by the comparison of its results with those provided by other state-of-the-art models. This model has been shown to outperform DenseNet-201, the model used for stomach cancer detection, and performs significantly better than Inception-v3. GastroNet substantially contributes to the diagnosis of the condition with 97.3% accuracy, compared to its nearest competitor at 96.4%. All the necessary factors contributed to the high performance of GastroNet. The first step in diagnosing stomach cancer appropriately is to redesign the architecture. It enables the determination of required characteristics through accurate extraction and analysis. The FPAM addition has improved efficacy and accuracy by eliminating noise, while also giving the model the power to extract the required features more effectively compared to other features. Second, real-time clinical environment diagnosis necessitates a high speed. With a greater frame rate per second, the GastroNet model is more suited for practical use.

Despite its good performance, GastroNet has several limitations. The first limitation is that the model has been trained and tested only on a small dataset, which may not be a representative sample of the wide range of real-world clinical data and may therefore lack generalizability. The model’s performance has also not been tested in real-life clinical conditions, as other experiments in various real-time settings are pending before the model can be used sufficiently in the field of clinical diagnosis.

Future work

Future research can focus on integrating GastroNet with real-time clinical systems to assist endoscopists during live procedures, expanding its capabilities to detect other gastrointestinal diseases, and incorporating multimodal learning approaches by combining endoscopic images with clinical and histopathological data for improved accuracy. Additionally, exploring self-supervised and few-shot learning techniques can reduce dependency on large, labeled datasets, while enhancing model interpretability through explainable AI (XAI) methods can increase clinician trust. Further advancements can include federated learning for privacy-preserving training across multiple medical institutions, optimizing the model for deployment on low-power devices in resource-constrained settings, and refining real-time processing capabilities to enhance diagnostic speed and efficiency. These future directions will contribute to the broader adoption of AI-driven endoscopic diagnostics, improving early detection and treatment outcomes for gastrointestinal diseases.