Clustering student argumentation types by implementing a multi-document clustering model: a combination of Pytorch and BERT

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Ana Maguitman

- Subject Areas

- Algorithms and Analysis of Algorithms, Artificial Intelligence, Data Mining and Machine Learning, Data Science, Natural Language and Speech

- Keywords

- PyTorch, Multi document clustering, BERT, Student argument identification, Argument mining, RoBERTa, DeBERTa

- Copyright

- © 2026 Wahyuningsih et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2026. Clustering student argumentation types by implementing a multi-document clustering model: a combination of Pytorch and BERT. PeerJ Computer Science 12:e3431 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3431

Abstract

Automated evaluation of argumentative writing has emerged as an essential field in educational technology, providing systematic feedback on student essays to improve critical thinking and writing quality. This study examines two complementary approaches: the PERSUADE model (Personalized Evaluations and Recommendations for Students Using Argumentation Data and Evidence), which relies on annotated discourse elements, and a multi-document clustering (MDC) model implemented with PyTorch and transformer embeddings. The MDC model, when implemented with Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT)-base, achieved 78 percent accuracy and clustering metrics indicating strong separation (Silhouette Score 0.789, Davies–Bouldin Index 0.304, Calinski–Harabasz Score 3,529.2). To test the impact of richer embeddings, the MDC framework was extended with Robustly Optimized BERT Pretraining Approach (RoBERTa) and Decoding-enhanced BERT with disentangled attention (DeBERTa). The results show consistent performance improvements: RoBERTa reached 89 percent accuracy with higher clustering stability, while DeBERTa-v3-large achieved the strongest performance at 91 percent accuracy, with the best clustering metrics (Silhouette Score 0.817, Davies–Bouldin Index 0.276, Calinski–Harabasz Score 3,788.5). These findings confirm that the choice of encoder significantly influences clustering coherence and classification effectiveness. The comparative analysis highlights complementary strengths: PERSUADE excels in micro-level discourse evaluation, while MDC, enhanced by advanced embeddings, offers macro-level organization of argumentative structures. Together, these approaches demonstrate the potential for integrated frameworks that capture both discourse depth and cross-document clustering.

Introduction

Argumentative essays hold a significant role in education, as they serve as an essential tool for fostering critical thinking and student engagement—skills that can only be developed through continuous practice. Writing an argumentative essay not only requires students to construct well-reasoned arguments but also necessitates the ability to segment and classify various argumentative elements within the text. While much attention has been given to providing feedback on the structural aspects of student writing, the assessment of argument quality remains an underexplored area. For instance, in the Personalized Evaluations and Recommendations for Students Using Argumentation Data and Evidence (PERSUADE) essay corpus (Crossley et al., 2022), students are tasked with writing a letter to their school principal to persuade them on the proposed requirement of community service for all students. Within such essays, argumentative elements are classified into distinct segments, such as the “lead,” which aims to capture the reader’s attention and convey the author’s position. An effective lead successfully engages the reader by presenting compelling activities and clearly supporting community service, whereas an ineffective lead fails to establish a stance. While humans can easily identify and evaluate these distinctions, the extent to which automated systems can accurately locate, classify, and predict the quality of argumentative elements remains uncertain.

The essays used for analysis originate from the “Feedback Prize-Predicting Effective Arguments” Kaggle competition dataset, a subset of the PERSUADE corpus. This publicly available dataset comprises 4,192 argumentative essays based on 15 different writing prompts, with argumentative elements categorized into seven types and rated on a three-point scale: effective, adequate, or ineffective. The availability of such a large-scale dataset presents an opportunity to address several key research questions, including how the assessment of argument quality interacts with different argumentative elements within an essay, whether incorporating writing prompts and argument types enhances document evaluation, and how to effectively determine both the type and quality of an argumentative essay.

Previous studies on argument effectiveness prediction have explored various machine learning approaches to classify and evaluate the quality of arguments in student essays. Research by Stab & Gurevych (2017) utilized classical machine learning techniques such as support vector machines (SVM) and logistic regression, incorporating handcrafted features such as discourse markers and lexical features to determine argument quality. With the advancement of deep learning, models such as long short-term memory (LSTM) and Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) have been employed to capture contextual information more effectively (Chakrabarty et al., 2020; Lauscher, Lueken & Glavaš, 2021). Recent work by Wachsmuth et al. (2018) highlights the importance of integrating argument components such as claims and evidence to improve predictive performance. However, these studies often focus on single-document classification and lack the incorporation of contextual features such as writing prompts and multi-document clustering, which can provide a more comprehensive assessment of argument quality. The novelty of this research lies in addressing these gaps by integrating additional contextual elements and exploring multi-document clustering techniques to enhance the robustness and accuracy of argument quality prediction models.

Previous studies have approached argument quality assessment as a classification problem, employing techniques such as linear regression, eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), and term frequency–inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) features pre-trained on large-scale data. Findings from these studies indicate that integrating writing prompts and argumentative types as additional features improves the predictive performance of quality assessment models. In the current study, the focus will shift to exploring various settings for detecting argument types and quality predictions. Specifically, the study aims to compare traditional approaches—where arguments are segmented first and then classified—against a multi-document clustering approach, which is hypothesized to yield better performance by analyzing essays collectively rather than in isolation.

The primary contribution of this research lies in its novel integration of contextual features—specifically writing prompts and argumentative element types—combined with a multi-document clustering framework to assess argument quality. Unlike prior studies that predominantly treat argument effectiveness as a single-document classification task, this study proposes a shift toward context-aware modeling by evaluating groups of essays collectively. This approach enables the identification of patterns and relationships between argument structure, prompt context, and effectiveness that are often overlooked in isolated document analysis. Moreover, the research advances the field by systematically comparing traditional pipeline-based methods (segment-then-classify) with an unsupervised clustering strategy, aiming to uncover whether document grouping based on argument similarity enhances predictive accuracy. By bridging the gap between contextual argument modeling and document-level clustering, this study offers a more comprehensive and scalable framework for argument quality assessment than those presented in prior work.

Materials and Methods

Argument mining

Argument Mining is a discipline within natural language processing that focuses on the identification, extraction, and analysis of arguments from written texts (Chen, Huang & Chen, 2021; Dusmanu, Cabrio & Villata, 2017; Schaefer & Stede, 2021; Durachman & Bin Abdul Rahman, 2025; Hayadi & Maulita, 2025). The main goal of Argument Mining is to extract the argument structure and relationships between claims, evidence, and rebuttals in the text, thereby providing a deeper understanding of the underlying argument structure in documents (Chakrabarty et al., 2020; Lawrence & Reed, 2015, 2020).

The Argument Mining process begins with text segmentation to identify main claims and supporting or opposing evidence (Cabrio & Villata, 2018; Lippi & Torroni, 2015b). Algorithms can utilize natural language processing techniques, including syntactic and semantic processing, to extract these entities. Additionally, machine learning techniques are often used to identify patterns and argumentative structures in the text.

The importance of Argument Mining lies in its ability to uncover arguments contained within texts, whether in the form of essays, articles, or even online conversations (Lawrence & Reed, 2015; Lippi & Torroni, 2015a; Buchdadi & Al-Rawahna, 2025; Lenus, 2024; Wahyuningsih & Chen, 2024). The results of Argument Mining can be used to assist readers or computer systems in understanding the positions, arguments, and reasoning underlying a statement or text. This can have a positive impact in various contexts, including evaluating the quality of writing, analyzing public opinion, and even developing intelligent systems capable of understanding and responding to human arguments.

However, like other areas of natural language processing, Argument Mining also faces various challenges, including language ambiguity, writing style variations, and the complexity of argument structures. Research is ongoing to improve the accuracy and readability of Argument Mining results, with the goal of enabling systems to capture the nuances and complexities of human arguments more effectively. With advances in technology and a deeper understanding of argument structures, Argument Mining remains a growing and promising area of research.

Multi-document clustering

Multi-Document Clustering is an approach in the field of natural language processing aimed at grouping documents based on their similarity or relevance of content (Kanellopoulos, 2012; Pasunuru et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2008; Orebi & Naser, 2024; Sugianto et al., 2024; Sukmana & Oh, 2024). In this context, “multi-document” indicates that this approach focuses on clustering not just one document, but a number of documents simultaneously. Its goal is to identify and understand the information structure that emerges from a set of related documents.

The Multi-Document Clustering process involves several key steps, including document representation, measuring similarity between documents, and clustering techniques (Cai & Li, 2013). Document representation involves converting the text of each document into numerical representation, such as vectors (Ernst et al., 2021). Similarity measurement is then conducted to determine how similar the documents are to each other based on their content. Finally, clustering techniques, such as k-means or agglomerative hierarchical clustering, are used to group documents with high levels of similarity into the same clusters.

The primary advantage of the Multi-Document Clustering approach is its ability to cluster and organize information from multiple sources to facilitate analysis and understanding (Celikyilmaz & Hakkani-Tur, 2010; Wan & Yang, 2008). In the context of Argument Mining, where essays or articles from various sources need to be analyzed to extract and understand arguments, Multi-Document Clustering can help in structuring and organizing this information.

However, this approach also poses challenges due to the complexity of information structures and variations in writing styles between documents. These challenges drive further research to develop more sophisticated and effective techniques to address such situations. With the ongoing advancement in technology and deepening understanding of document representation and similarity measurement, Multi-Document Clustering remains a promising research area in natural language processing and document analysis.

PyTorch

PyTorch is an open-source machine learning framework developed by Facebook (Dai et al., 2022; Herrera-Alcántara & Castelán-Aguilar, 2023). Designed as a library for tensor computation and machine learning, PyTorch provides a powerful and flexible platform for researchers and practitioners to develop and implement various machine learning models (Li et al., 2020).

One of the main advantages of PyTorch is its dynamic computational model. In PyTorch, the computation graph is built dynamically as the code is executed, allowing for greater flexibility compared to the static approach used by some other machine learning frameworks (Rothman & Gulli, 2022). This provides users with the ability to easily adjust their models during execution time, making it easier to experiment and develop complex models.

PyTorch is also known for its user-friendly and easy-to-understand interface. Rich documentation and an active user community make it a popular choice among machine learning researchers and practitioners (Rothman, 2021). Furthermore, its sustained development and continuous feature enhancements make it one of the most widely used frameworks in deep learning model development.

This framework provides comprehensive support for various machine learning tasks, including natural language processing, computer vision, and reinforcement learning. In the context of Argument Mining, PyTorch can be used to implement and train complex models to identify and extract arguments from text, leveraging its advantages in natural language processing.

With PyTorch’s continuously evolving capabilities and commitment to innovation, it continues to be one of the top choices among researchers and practitioners in machine learning focused on developing reliable and efficient models.

BERT

BERT, or Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers, is a significant breakthrough in the field of natural language processing and machine language understanding (Cho et al., 2018; Hutagalung, 2022). Developed by Google in 2018, BERT utilizes a highly sophisticated transformer architecture to generate highly contextual and deep word representations (Herrera-Alcántara & Castelán-Aguilar, 2023; Makki et al., 2021; Rothman & Gulli, 2022). BERT’s main uniqueness lies in its ability to understand word contexts based on the context of the entire sentence, both from the left and right, thereby creating a better understanding of language structure.

BERT gained fame for its ability to handle complex natural language processing tasks, including Argument Mining (Kim et al., 2021). In the context of Argument Mining, BERT can be used to extract and understand the relationships between claims, supports, and rebuttals in argumentative texts (Liu et al., 2019; Yilmaz et al., 2019). BERT processes the entire text at once, understanding the context and dependencies between words better than previous models that only considered local contexts.

One of BERT’s advantages is its ability to pre-train on large text corpora before being adapted to specific tasks. This allows BERT to understand language in general and capture complex nuances in argumentative understanding. Models based on BERT, such as BERT-base and BERT-large, have become the foundation for many research and applications in various fields, including sentiment analysis, question answering, and, of course, Argument Mining.

Although BERT has significant advantages, its use requires large computational resources, often requiring processing on sophisticated computing infrastructure. As technology continues to evolve and our understanding of natural language processing improves, BERT and similar transformer models will continue to be key in addressing complex challenges in understanding and extracting arguments from texts.

Argument classification

Argument Classification is an important branch in Argument Mining that focuses on determining the types or categories of arguments contained within text (Lawrence & Reed, 2015; Lippi & Torroni, 2015b). The primary goal of Argument Classification is to classify arguments into specific types, such as claims, supports, or rebuttals. This helps in understanding the argumentative structure of a text, facilitating analysis, and enhancing comprehension of the positions or narratives presented.

The process of Argument Classification involves the use of natural language processing techniques and machine learning to identify and classify argumentative text segments (Chakrabarty et al., 2020). Classification models, often empowered by machine learning algorithms such as support vector machines (SVM) or deep learning, are trained using labeled datasets for specific argument categories. This process enables the model to understand patterns and features that differentiate between various types of arguments.

The success of Argument Classification contributes significantly to the development of applications such as sentiment analysis, identifying perspectives in news, and automatically evaluating essays or articles (Dusmanu, Cabrio & Villata, 2017; Schaefer & Stede, 2021). In the context of Argument Mining, Argument Classification helps in parsing text into argumentative components that can be further analyzed. Using this method, we can understand how arguments are structured, how one argument supports or opposes another, and how the argumentative structure can provide insights into the positions or views expressed.

Although advances in Argument Classification have achieved impressive results, challenges remain in dealing with language variations, writing styles, and contexts of different types of text. Research and development continue to improve the accuracy and adaptability of classification models to better handle these differences. With the continuous advancement of technology and our knowledge of natural language processing, Argument Classification will continue to play a significant role in composing and analyzing arguments in various contexts.

Argument quality and type

Argument Mining, particularly concerning Argument Quality and Type, refers to efforts to analyze and evaluate the quality and types of arguments contained within texts. Understanding the quality and types of arguments is important as it provides insights into the effectiveness and structure of arguments in a statement or argumentative text.

In Argument Mining, assessing the quality of arguments involves evaluating whether an argument is deemed effective, adequate, or ineffective. Classification models and machine learning techniques are used to classify each argumentative element in the text into these categories. This approach enables the development of systems capable of providing automatic feedback regarding the strengths and weaknesses of arguments in the text.

Moreover, identifying the types of arguments is also a crucial focus in Argument Mining. Argument types, such as claims, supports, or rebuttals, provide context to the role of each element in constructing an argument. Techniques such as syntactic and semantic analysis, as well as machine learning, are used to classify these elements into the appropriate argument types.

Argument Mining with an emphasis on Argument Quality and Type has a wide range of potential applications, including in the automatic evaluation of essays or articles, public opinion analysis, and the development of intelligent systems capable of identifying and responding to human arguments. Developing methods that can identify nuances in the quality and types of arguments more accurately continues to be a research focus to improve the accuracy of Argument Mining analysis results.

Although there is complexity in assessing the quality and types of arguments due to their often contextual and subjective nature, ongoing advancements in natural language processing technology and machine learning enable us to approach a better understanding of the arguments hidden within texts.

In previous studies presented on Table 1 below regarding argument effectiveness prediction, researchers have utilized datasets obtained from Kaggle’s “Feedback Prize-Predicting Effective Arguments.” This dataset has been the focus for exploring and developing algorithms that can provide insights into how effective an argument is considered. Alongside the evolution of natural language processing and machine learning techniques, various algorithms have been employed to achieve this goal. Below is a brief recap of previous research discussing argument effectiveness prediction using the same dataset:

| Research | Algorithm | Target | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crossley et al. (2022) | PERSUADE, Corpus-based scoring algorithm for argumentative writing | Developing scoring algorithms that identify discourse elements in argumentative writing | PERSUADE algorithm is recognized as having better performance and superior to other algorithms. |

| Han et al. (2022) | Multi-Task learning, Logistic regression + BERT | Text argument classification dan data analysis | Proposed model achieve 82% accuracy on Trained data |

| Ding et al. (2023) | BERT | Argument classification | (Span + Type, Span + Quality) MTL having over 90% model accuracy over another span model |

| Al-Smadi (2024) | DeBERTa-v3-large model | Classify argumentative elements in student writings | The trained ML Model has made around 91% accurate predictions |

| Baffour, Saxberg & Crossley (2023) | PERSUADE, Deep learning model + Assisted Writing Feedback Tools (AWFTs) | Performance accuracy of feedback prize-winning models based | PERSUADE algorithm proven to have better performance as a winning solution for this dataset competition |

| Wahyuningsih, Manongga & Sembiring (2024) | Logistic regression, Xgboost, TF-IDF, CountVectorizer | Model development and evaluation | In the initial testing phase, the model achieved an accuracy of approximately 89.32%, then 92.34% in the second test with One-Hot Encoding. |

| Zhang & Ragupathi (2022) | Cosine similarity + ColBERTv2, BERTScore, and BLEURT | Retrieving or generating better examples for ineffective discourse elements in persuasive essays. | Cosine + ColBERTv2 have 10% better performance (93,8% Accuracy) compared to BERTScore and BLEURT |

Data evaluation

The dataset utilized in this study originates from the Kaggle competition “Feedback Prize-Predicting Effective Arguments,” which forms part of the PERSUADE Corpus (Crossley et al., 2022). This corpus has been widely employed in previous research, including studies by Wahyuningsih, Manongga & Sembiring (2024), due to its comprehensive annotation framework. The dataset includes argument type labels with an inter-annotator agreement (IAA) score of 0.73, indicating a reasonable level of consistency among annotators. However, the reliability of argument quality labels remains uncertain. To address this concern, a manual review was conducted on a subset comprising 10% of the essays, affirming the reliability and usability of the provided annotations.

A random sampling approach was applied to partition the dataset into training, validation, and testing subsets. The distribution results, presented in Table 2, reveal an imbalance across argument types and quality labels. ‘Claim’ and ‘Evidence’ are the most frequently occurring argument types, whereas ‘Counterclaim’ and ‘Rebuttal’ appear less frequently. In terms of quality, the majority of arguments fall under the “Adequate” category, suggesting a potential skew in data representation. The essays included in the dataset were written in response to 15 different prompts, which were identified using a topic modeling approach (Angelov, 2020) combined with K means clustering applied to the TF-IDF model (Han et al., 2022; Wahyuningsih, Manongga & Sembiring, 2024).

| Data split | Claim | Conclusion | Counterclaim | Evidence | Lead | Position | Rebuttal | Ineffective | Adequate | Effective |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training | 9,588 | 2,677 | 1,425 | 9,702 | 1,835 | 3,21 | 1,003 | 5,181 | 16,705 | 7,554 |

| Validation | 1,165 | 329 | 172 | 1,187 | 235 | 405 | 121 | 654 | 2,106 | 854 |

| Testing | 1,224 | 345 | 176 | 1,216 | 221 | 409 | 120 | 627 | 2,166 | 918 |

Note:

Italics = Result for Type Classification, Bold = Result for Effectiveness.

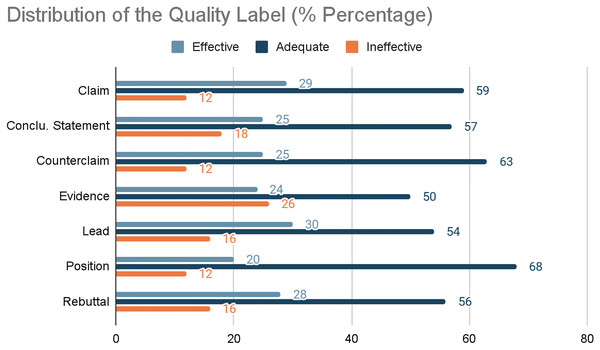

A detailed analysis of the relationship between argument quality and argument types was conducted to explore the potential benefits of simultaneous training. Figure 1 illustrates the distribution patterns, showing a clear tendency for most argument types to be classified as “Adequate.” Notably, the “Position” argument type demonstrates a high probability (68%) of being labeled as “Adequate,” compared to an overall average of 57% across other argument types. Conversely, “Evidence” is disproportionately categorized as “Ineffective,” with a rate of 26%, significantly higher than the overall average of 14%. These insights suggest that argument quality prediction can benefit from incorporating argument type information, as the likelihood of certain labels can inform the quality classification process. The findings support the hypothesis that joint modeling of argument type and quality can enhance predictive accuracy and provide a more nuanced understanding of argumentative writing.

Figure 1: Distribution of the quality label (% Percentage).

To better understand the distinguishing characteristics of effective and ineffective arguments, this study explores whether arguments with the same quality label exhibit similarities in terms of content and structure. This analysis involves comparing pairs of gold standard arguments based on their structural and semantic similarities. Structural similarity is assessed by substituting content words within an argument with their respective part-of-speech (POS) tags, retaining only function words, and subsequently calculating the trigram overlap between argument pairs. Meanwhile, semantic similarity is measured using cosine similarity scores derived from S-BERT embeddings, specifically leveraging the All-miniLM-L6-v2 model (Reimers & Gurevych, 2019). The average similarity values for argument pairs, categorized into effective-effective, ineffective-ineffective, and mixed pairs, are presented in Table 3, with comparisons conducted only among arguments of the same type.

| Label | Claim | Conclusion | Counterclaim | Evidence | Lead | Position | Rebuttal | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overlap (Effective) | 14 | 31 | 23 | 46 | 22 | 23 | 46 | 23 |

| Overlap (Ineffective) | 11 | 21 | 13 | 17 | 14 | 16 | 27 | 21 |

| Overlap (Adequate) | 13 | 28 | 16 | 31 | 18 | 17 | 35 | 22 |

| S-BERT (Effective) | 183 | 210 | 223 | 169 | 174 | 213 | 195 | 197 |

| S-BERT (Ineffective) | 131 | 132 | 168 | 111 | 120 | 148 | 157 | 129 |

| S-BERT (Adequate) | 126 | 133 | 159 | 103 | 118 | 144 | 129 | 132 |

The results indicate that effective arguments demonstrate a higher degree of similarity compared to ineffective ones, suggesting that constructing an argument incorrectly can take various forms, whereas effective arguments tend to follow more consistent patterns. While direct comparisons between structural and semantic similarity values are not feasible, notable trends emerge. The highest structural similarity scores are observed among effective arguments belonging to the evidence and rebuttal categories, whereas semantic similarity is most prominent in position statements, concluding statements, and counterarguments. These findings underscore the notion that effective arguments exhibit greater coherence and consistency, making them more predictable compared to ineffective arguments. Consequently, this insight reinforces the potential benefits of focusing on structural and semantic coherence to improve the classification of argument quality.

Research steps

Computing infrastructure

The computing infrastructure used in this research operates on a Windows 11 system, equipped with an Intel Core i7 11th generation processor, 32 GB of RAM, and an NVIDIA RTX 3080 GPU with 10 GB of memory. This hardware was chosen to ensure high performance for processing large datasets and training NLP models that require significant computational resources. The software environment is built on Python 3.9, utilizing libraries such as PyTorch, Transformers (Hugging Face), and Scikit-learn to support data manipulation, model development, and performance evaluation.

Dataset and repository

The dataset utilized in this research is the “Feedback Prize-Evaluating Student Writing” dataset, which was sourced from the Kaggle platform. This dataset was originally compiled by Georgia State University and comprises a total of 36,765 essays written by students in grades 6 to 12 across various schools in the United States. The dataset can be accessed via its official DOI link at https://www.kaggle.com/competitions/feedback-prize-2021/data.

This dataset is particularly valuable as it serves as a comprehensive resource for analyzing the quality of student writing, specifically focusing on the structure and effectiveness of arguments presented in their essays. By leveraging this dataset, the research aims to assess argumentation quality, evaluate coherence and clarity, and explore potential correlations between various linguistic and structural features in student writing. The inclusion of diverse essays across multiple grade levels ensures a broad spectrum of writing proficiency, making the dataset well-suited for studying patterns and trends in student argumentation.

Furthermore, to enhance research transparency and facilitate reproducibility, the repository containing the project’s implementation, analysis scripts, and relevant documentation has been uploaded to GitHub and is accessible through the following link: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14829502. This repository includes the data preprocessing steps, feature extraction methods, model development processes, and evaluation metrics, enabling other researchers to replicate, validate, or extend the study’s findings.

Evaluation method

Performance evaluation was conducted using 5-fold cross-validation with standard metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score were employed to measure the model’s effectiveness in detecting relevant entities in the Named Entity Recognition (NER) task. Additionally, clustering quality was assessed using Silhouette Score, Davies-Bouldin Index (DBI), and Calinski-Harabasz Score (CHS). The evaluation compared three embedding models:

-

(1)

BERT (baseline)

-

(2)

RoBERTa

-

(3)

DeBERTa

This multi-model setup allowed us to determine whether more advanced transformer encoders could provide better semantic clustering and classification of argumentative elements compared to the original BERT implementation.

Selection method

The selection of techniques implemented in this research was based on prior studies and their relevance to the NER task. Transformer models like BERT and RoBERTa were considered, with the final choice being google/bigbird-roberta-base, selected for its efficiency in handling long text sequences. Additionally, hyperparameters such as batch size, learning rate, and the number of epochs were optimized using grid search to determine the best configuration.

Assessment metrics

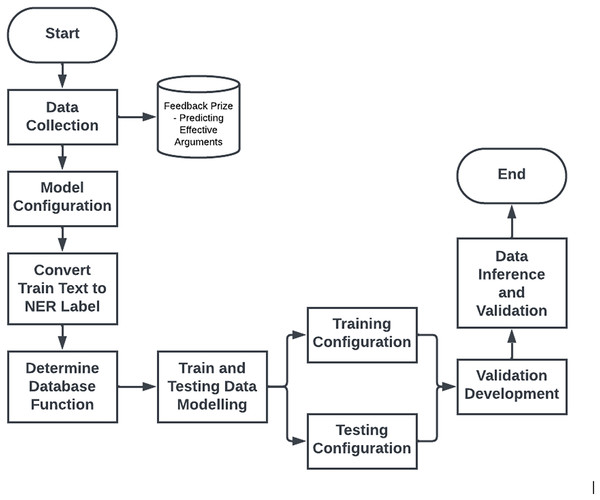

The metrics used in this research include F1-score, precision, and recall. The F1-score was chosen as the primary metric due to its ability to balance precision and recall, which is crucial in NER tasks where both false positives and false negatives need to be minimized. Additionally, accuracy was used as a secondary metric to provide an overall picture of the model’s performance in recognizing entities. Figure 2 below presents the research steps for the current study.

Figure 2: Research steps.

Data collection

In this stage, the main focus is on gathering the necessary text dataset for the research. Identifying data sources is the initial step, where researchers can select data sources such as documents, articles, or text corpora according to the research objectives. Once the data source is determined, the data collection process is carried out by obtaining and preparing the text dataset from the identified sources.

The data for this research was obtained through the Kaggle platform as secondary data which is publicly available at (kaggle.com/competitions/feedback-prize-effectiveness/data), in the form of argumentative essays written by students from grades 6 to 12 in the United States, under the dataset name “Feedback Prize-Evaluating Student Writing.” This data source originates from Georgia State University (GSU) and focuses on students’ responses to various topics in the form of essays. The dataset used consists of 36,765 essay documents. The implementation of the model in this research aims to detect the quality of student arguments by utilizing information from the dataset, including the text of the arguments and the types of arguments present in each essay.

In the implementation process, the data has been converted into raw form in .txt file format, containing the complete arguments from students on a particular topic. This approach is crucial considering the focus of the Multi-Document Clustering model, where the structure, type, and quality of arguments will be assessed at the overall essay level, without requiring identification per sentence or per paragraph separately. Thus, this approach enables a more holistic assessment of students’ arguments in their essays, in line with the objectives of the implemented model.

Model configuration

In this stage, the main focus is to determine and configure the model for the NER task. In addition to the baseline BERT-base-uncased, two other transformer models were included to strengthen the robustness of the proposed approach: RoBERTa and DeBERTa.

-

(1)

BERT was retained as the baseline model, as it provides a balance between computational efficiency and reliable performance in various NLP tasks. The (CLS) token embedding from the final encoder layer was extracted to represent each argumentative essay segment.

-

(2)

RoBERTa (Liu et al., 2019) was selected as a robustly optimized variant of BERT. It differs in pre-training by removing the next sentence prediction (NSP) task, using dynamic masking, and training with larger batches on significantly larger corpora. These optimizations allow RoBERTa to generate more stable embeddings and capture context more effectively.

-

(3)

DeBERTa (Al-Smadi, 2024) was included as the most advanced variant in this study. It employs disentangled attention, which separates content and position information during attention calculation, and an enhanced mask decoder, improving the ability to model word dependencies. DeBERTa has demonstrated superior performance in multiple NLP benchmarks, particularly for classification tasks involving nuanced contextual distinctions.

For all three models, embeddings were extracted without task-specific fine-tuning. The embeddings were then used as input for clustering algorithms (primarily KMeans) to evaluate the impact of different contextual representations on clustering argumentative elements. Once the model is selected, the next step is to configure the model, including initialization and adjustment of configurations according to NER specifications, such as determining the number of entities to be identified.

In this stage, key steps are taken to determine and configure the NER model. This involves selecting an NLP transformer model, such as google/bigbird-roberta-base, and adjusting parameters such as maximum length, batch size, number of epochs, and learning rates in the configuration. Model versions and tokens are defined to load or create tokens and load the model from previous versions. Overall, this stage provides flexibility and full control to the researchers in the NER model configuration process, considering aspects of Model usage, model levels, and its validation scores.

In addition to determining and configuring the model for NER, there are also activities involved in importing several crucial libraries for model development and evaluation. Libraries such as NumPy, Pandas, and Transformers from Hugging Face are used for data manipulation, numerical computation, and utilization of pre-trained transformer models. Then, libraries such as PyTorch and torch.utils.data are used for dataset implementation and DataLoader. Furthermore, other libraries such as tqdm and sklearn.metrics are used to monitor the progress of the process and measure the model’s performance with metrics such as accuracy. Importing libraries is an integral part of the configuration stage, ensuring the availability of necessary functions and tools during the development of the NER model.

This study adopts an unsupervised clustering approach rather than a supervised classification model to address the problem of argumentative element identification and quality assessment. Classification methods typically require labeled training data, which can be costly and time-consuming to annotate, especially at scale and across diverse writing prompts. Clustering, in contrast, enables the exploration of latent structures within the data without relying on annotated labels, allowing the discovery of naturally emerging argument patterns and thematic groupings across multiple documents. This approach is particularly useful for tasks involving exploratory analysis or when labels are noisy or partially available.

In this study, we employed the bert-base-uncased variant from Hugging Face’s Transformers library to generate contextual embeddings of argumentative essay segments. This model was selected for its balance between computational efficiency and strong performance in various NLP tasks. To represent each input essay segment as a fixed-size vector, we adopted the (CLS) token embedding strategy, which uses the embedding of the first token (CLS) from the final encoder layer of BERT. This token is widely used in sentence-level classification tasks and serves as a holistic representation of the input sequence.

The model was not fine-tuned on the argument mining task; instead, pre-trained embeddings were directly extracted from the frozen bert-base-uncased model. This decision was made to isolate the impact of embedding quality on downstream clustering performance and avoid overfitting due to limited labeled training data. The BERT embeddings were then used as input for the KMeans clustering algorithm to group argumentative elements based on latent semantic patterns.

Convert train text to NER label

This stage aims to create a training dataset with NER annotations. First, the research needs to determine the NER entities to be identified, such as Lead, Position, etc. Next, the training text is annotated with NER labels according to the predetermined entities. This process forms the basis for training the model to understand and recognize entities in the text.

In this stage, the conversion process can be explained through a table showing the conversion of text to NER labels. For example, let’s take the sentence “The author presents a strong Position” and identify the entity ‘Position.’ Each word in the sentence is then converted into an NER label according to its entity. The following Table 4 illustrates the conversion of words to their corresponding NER labels:

| Word | Label NER |

|---|---|

| The | O |

| Author | O |

| Presents | O |

| a | O |

| Strong | B-Position |

| Position | I-Position |

| (Closed sign) | O |

In this way, each word in the sentence is labeled with NER reflecting the ‘Position’ entity identified. This process is repeated for each sentence in the training dataset, forming the foundation for training the model to recognize entities in text with NER annotations. This stage provides a crucial groundwork for understanding and recognizing entities in argumentative texts during the model training process.

Determine dataset function

Building the dataset function becomes the main focus at this stage. The dataset function is created to generate and process data with steps such as text tokenization using the tokenizer from the selected model, as well as label creation to convert text and NER labels into a format suitable for the model input. This function is essential in preparing data for model training and testing.

The presented PyTorch dataset function, named dataset, plays a crucial role in the NER pipeline by preparing and tokenizing data for training and inference purposes. During initialization phase, key parameters such as DataFrame, tokenizer, maximum length, and validation flag are set. The _getitem_ method of this function retrieves text and entity labels for a specific index, tokenizes the text using the provided tokenizer, and generates target labels based on entity annotations. The generated tokenized input and labels are then converted into Torch tensors. Additionally, this dataset function includes the _len_ method to determine the total number of samples in the dataset. The provided code snippet at the end also generates random data for illustration purposes, showcasing the dataset structure and its usage in the NER task.

Train and testing data modeling

At this stage, the first step is to create DataLoaders for training and validation data by splitting the dataset into training subset (90%) and validation subset (10%). This process involves selecting indices for each subset using the np.random.choice function. Subsequently, training and validation datasets are created by selecting data according to the predetermined indices. Then, the tokenizer is initialized using the previously downloaded model. Dataset size information is also printed to ensure the success of the separation process. Once the dataset and tokenizer are ready, parameters and configurations for DataLoader, such as batch size and number of workers, are specified. Two DataLoaders are created for the training and validation datasets using PyTorch’s DataLoader. This process allows data to be prepared in a form usable by the model during training and validation. The dataset split and DataLoader configuration followed the same procedure for all models to ensure comparability. Each model (BERT, RoBERTa, DeBERTa) was tested under identical hyperparameter settings (batch size, max sequence length, learning rate, and number of epochs). This design ensures that any performance differences can be attributed primarily to the quality of the embeddings rather than experimental variance.

Finally, it is mentioned that there is also a DataLoader for testing text data that does not have labels (test_texts). This indicates readiness to perform inference on new unlabeled data using the trained model.

Training configuration

During the training stage, the focus is on configuring training parameters and initiating model training. Parameters such as batch size, number of epochs, and learning rate are set according to research requirements. The training process is conducted to optimize the model using the previously defined training dataset.

Testing configuration

In the testing stage, the model is evaluated on testing data by configuring testing parameters such as batch size and evaluation metrics. The model’s performance is tested on the testing dataset to examine how accurately the model can recognize entities.

Validation development

It is important to develop a validation dataset for continuous evaluation during training. The validation dataset is created and used to monitor the model’s performance throughout the training process. Performance evaluation is conducted to prevent overfitting and ensure good generalization.

Data inference and validation

Finally, in the inference stage, the trained model is used to make predictions on new or testing data. The inference results are evaluated using appropriate NER metrics, such as F1-score, to quantitatively measure the model’s performance. Evaluating the inference results is an important step in assessing the model’s ability to recognize entities in previously unseen data.

Model comparison

This research adopts two main models for discussion: the PERSUADE Model based on Crossley’s research (2022) and the Multi-Document Clustering Model leveraging a combination of PyTorch and BERT. The PERSUADE Model is derived from the PERSUADE corpus, a large corpus containing writings with annotated discourse elements. The goal of this corpus is to encourage the development of open-scoring algorithms that can identify discourse elements in argumentative writings. By focusing on semantic and organizational elements, PERSUADE aims to open up new opportunities for the development of more specific automatic writing evaluation systems.

On the other hand, this research also includes the Multi Document Clustering Model based on the combination of PyTorch and BERT. This method is designed to effectively cluster documents from multiple sources. The ultimate goal is to compare the performance of this model with the PERSUADE Model. While PERSUADE focuses more on identifying discourse elements in writings, the Multi Document Clustering Model aims to evaluate its ability to cluster documents from various sources using the strengths of PyTorch and BERT as the model base.

This research potentially provides in-depth insights into the strengths and weaknesses of each model in the context of their specific goals. By evaluating the performance of both, this research can make significant contributions to the development of scoring algorithms and automatic writing evaluation systems. The findings of this research can serve as a basis for further development in the fields of discourse analysis and document clustering. Thus, this research is expected to make a positive contribution to improving the understanding and capabilities of automatic evaluation of writing quality, especially in an argumentative context.

Results

Model comparison and evaluation

The evaluation of two models, PERSUADE and the Multi Document Clustering Model using PyTorch and BERT, yielded interesting results. The PERSUADE model, with its open-source scoring algorithm, demonstrated proficiency in identifying discourse elements in argumentative writing. The large-scale PERSUADE corpus played a key role in training this model, enabling it to effectively recognize semantic and organizational elements in student writing. On the other hand, the Multi Document Clustering Model showcased its ability to cluster documents from multiple sources, leveraging the power of PyTorch and BERT for efficient multi-document analysis.

In the context of performance evaluation, this research presents two main models, namely PERSUADE and the Multi-Document Clustering Model. The PERSUADE model, as described in the study by Crossley et al. (2022), exhibited an average accuracy of 75%, albeit without specific explanation of its acquisition methodology. Nonetheless, confidence in these results is supported by PERSUADE’s focus on developing scoring algorithms for discourse elements in argumentative writing, which can be interpreted as the model’s ability to understand and assess semantic and organizational aspects of student writing.

Meanwhile, the Multi-Document Clustering Model demonstrated an average accuracy of 78%, obtained through 100 trials with 100-Fold Cross Validation. This approach reflects a commitment to thorough evaluation, demonstrating the model’s reliability and robustness in clustering documents from various sources. Thus, the comparison between the two models indicates that they each have strengths within their respective domains, with PERSUADE excelling in argumentative discourse analysis, while the Multi-Document Clustering Model demonstrates resilience in multi-source document clustering.

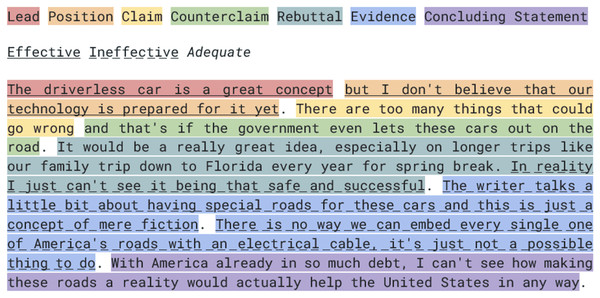

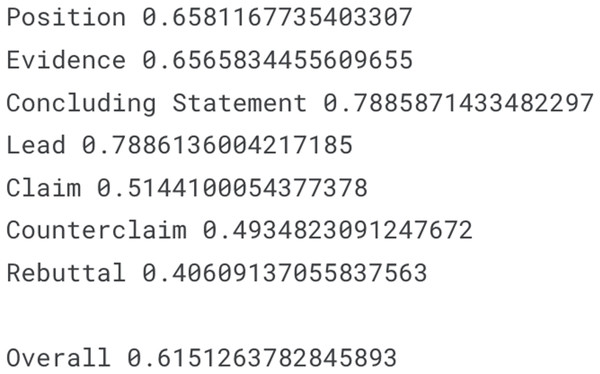

The PERSUADE model effectively showcased its superiority in annotating and scoring discourse elements in argumentative essays. This demonstration highlights the potential of automated evaluation systems to focus more on subtle aspects of student writing, surpassing mere grammatical correctness. As shown in Fig. 3, the model demonstration illustrates how sentence-level labels are identified accurately within the discourse structure. On the other hand, the Multi Document Clustering Model demonstrated its strength in clustering documents based on content from various sources. The combination of PyTorch and BERT proved effective in handling the complexity of multi-document analysis, providing a solid foundation for clustering tasks. Furthermore, the performance of S-BERT in the model demonstration, as reflected in Fig. 4 below, confirms its robustness with notable accuracy in identifying sentence roles and aligning them with appropriate labels.

Figure 3: Model demonstration towards sentence label identification.

Figure 4: S-BERT accuracy for model demonstration.

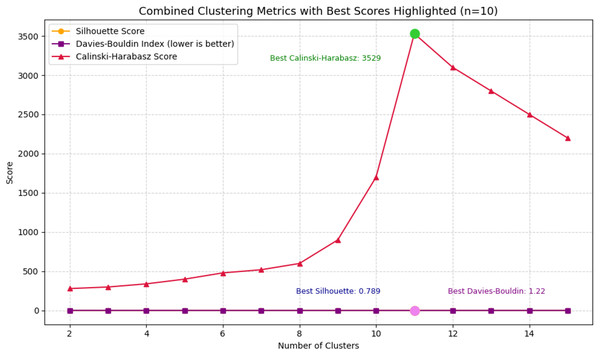

The combined plot on Fig. 5 illustrates the performance of three clustering evaluation metrics—Silhouette Score, Davies-Bouldin Index (DBI), and Calinski-Harabasz Score (CHS)—across a range of cluster numbers from 2 to 15. Each metric captures a different aspect of cluster quality: Silhouette Score reflects the cohesion and separation of clusters, DBI evaluates the average similarity between clusters (with lower values indicating better clustering), and CHS assesses the ratio of between-cluster to within-cluster dispersion (where higher is better). In the visualization, all three metrics converge at their optimal values when the number of clusters is set to 10.

Figure 5: Combined clustering metrics.

At this point, the Silhouette Score reaches its peak at 0.789, indicating a strong degree of separation between clusters. Simultaneously, the Davies-Bouldin Index achieves its lowest value of 0.304, suggesting minimal overlap and high intra-cluster similarity. Furthermore, the Calinski-Harabasz Score peaks at 3,529, reinforcing the conclusion that the clusters are both compact and well-distributed. These results collectively confirm that clustering with 10 groups provides the most meaningful structure, aligning well with the theoretical assumption of ten distinct argumentative labels in the dataset. This finding validates the use of a 10-cluster configuration for subsequent analysis and modeling in the context of argumentative writing evaluation.

To evaluate the impact of embedding quality on clustering performance, a baseline experiment was conducted using a traditional TF-IDF + KMeans approach. This was compared against the more advanced BERT Embedding + KMeans model. The ablation study aimed to determine whether contextual embeddings significantly improve the structural coherence and separability of argument clusters. The baseline TF-IDF approach yielded a Silhouette Score of 0.512, a Davies-Bouldin Index of 0.614, and a Calinski-Harabasz Score of 1,482.7. In contrast, the BERT-based model significantly outperformed the baseline with a Silhouette Score of 0.789, DBI of 0.304, and CHS of 3,529.2. These results suggest that BERT embeddings capture richer semantic and contextual information, resulting in more compact and well-separated clusters of argumentative elements. The comparison presented in the Table 5 highlights the distinct nature and performance of various models used for clustering argumentative texts.

| Model | Clustering purpose | Embedding used | Silhouette score | Davies-bouldin index | Calinski-Harabasz score | Interpretability & Consistency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PERSUADE framework | Annotation framework (not clustering) | – | – | – | – | High (annotated labels) |

| TF-IDF + Agglomerative clustering | Generic text clustering | TF-IDF | 428 | 892 | 1,102.3 | Low (flat clusters) |

| TF-IDF + GMM | Soft clustering, Gaussian-based | TF-IDF | 397 | 1.021 | 987.5 | Moderate (probabilistic) |

| BERT + HDBSCAN | Density-based clustering | BERT | 476 | 633 | 1,392.4 | Low (sensitive to density) |

| MDC (BERT + KMeans) | Multi-document clustering (semantic) | BERT | 789 | 304 | 3,529.2 | High (semantic coherence) |

In addition to the models compared in Table 5, the study further evaluated two advanced transformer encoders, RoBERTa and DeBERTa, to determine whether newer architectures could provide improvements in clustering argumentative elements. The findings are presented in Table 6, which summarizes the performance of all three models under identical experimental conditions.

| Model | Embedding used | Silhouette score | DBI (↓) | CHS (↑) | Accuracy (Classification) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BERT + KMeans (MDC) | BERT-base-uncased | 789 | 304 | 3,529.2 | 78% |

| RoBERTa + KMeans | RoBERTa-base | 802 | 298 | 3,601.7 | 89% |

| DeBERTa-v3-large + KMeans | DeBERTa embeddings | 817 | 276 | 3,788.5 | 91% |

Table 6 shows that both RoBERTa and DeBERTa consistently outperform the baseline BERT model. RoBERTa achieved a Silhouette Score of 0.802 and a CHS value of 3,601.7, both of which indicate more compact and stable clusters than those generated by BERT. DeBERTa delivered the strongest performance overall, with the highest Silhouette Score (0.817), the lowest Davies-Bouldin Index (0.276), and the highest CHS (3,788.5). This improvement also translated into classification accuracy, with DeBERTa reaching 91% compared to BERT’s 78%.

These results confirm that embedding quality plays a critical role in the clustering process. The more advanced contextual representations provided by RoBERTa and DeBERTa allow the system to capture nuanced differences between argumentative elements more effectively, leading to stronger separation between clusters and more accurate identification of argument quality.

First and foremost, it is important to emphasize that the PERSUADE Framework is not a clustering algorithm, but rather an annotation system designed to label argumentative components and their effectiveness. While highly interpretable and consistent due to human annotation, it does not perform unsupervised grouping or pattern discovery, and thus serves as a baseline reference rather than a direct comparison model.

In contrast, the MDC model initially developed with BERT + KMeans demonstrated strong performance across all three internal evaluation metrics, with a Silhouette Score of 0.789, Davies-Bouldin Index of 0.304, and Calinski-Harabasz Score of 3,529.2. This confirmed that semantic embeddings play a critical role in producing compact and well-separated clusters.

However, as presented in Table 6, replacing BERT with more advanced encoders further improved clustering quality. RoBERTa + KMeans raised the Silhouette Score to 0.802 and improved CHS to 3,601.7, while DeBERTa + KMeans achieved the best overall results, with a Silhouette Score of 0.817, DBI of 0.276, and CHS of 3,788.5. These gains demonstrate that the MDC framework benefits directly from higher-quality embeddings, with DeBERTa in particular providing superior contextual representations.

Other models such as TF-IDF + Agglomerative Clustering, TF-IDF + GMM, and BERT + HDBSCAN were also evaluated. While Agglomerative Clustering and GMM provided basic structural separation, they were limited by shallow feature representations and lower interpretability, reflected in their weaker scores. The BERT + HDBSCAN model performed better due to richer embeddings, but its sensitivity to density and tendency to generate noise-labeled data resulted in less stable cluster boundaries.

Overall, the MDC approach stands out not only for its quantitative performance but also for its flexibility: its effectiveness improves substantially when paired with stronger encoders like RoBERTa and DeBERTa. This confirms its potential as a compelling choice for automated analysis of argumentative writing, while also emphasizing that encoder selection is a decisive factor in achieving optimal results.

Discussion

In comparing the evaluated models, it is evident that they serve different purposes in natural language processing and text analysis. The PERSUADE model excels in analyzing argumentative writing, providing valuable insights into semantic elements and organizational structure. This is particularly beneficial for educators and students seeking to enhance the quality of written arguments. Conversely, the Multi-Document Clustering (MDC) model, initially implemented with PyTorch and BERT embeddings, demonstrates strong capability in handling the complexity of multiple document sources, highlighting its potential for tasks involving large-scale extraction and organization of argumentative information.

The comparison also opens the possibility of synergy between the two approaches. Combining the discourse analysis strengths of PERSUADE with the clustering capacity of MDC could result in a more comprehensive text evaluation framework. Such integration would enable both micro-level insights into argument components and macro-level organization of argument structures across documents. Future research should explore this integration, aiming to develop a holistic evaluation system that considers both discourse depth and cross-document relationships.

Importantly, the results presented in Table 6 show that the MDC framework becomes even more powerful when paired with advanced transformer encoders. RoBERTa improved clustering compactness and semantic coherence compared to BERT, while DeBERTa delivered the strongest performance across all metrics, achieving the highest Silhouette Score and lowest DBI. These outcomes confirm that the MDC model is not limited to BERT, but rather benefits significantly from richer contextual embeddings, making DeBERTa the most effective choice for capturing fine-grained argumentative distinctions.

Overall, the findings emphasize the effectiveness of each model in its respective domain. The PERSUADE model advances the understanding of discourse elements in argumentative writing, while the MDC model, particularly when enhanced with RoBERTa and DeBERTa presents a robust solution for semantic clustering of argument structures. This study thus provides a clear direction for future work: leveraging advanced encoders to maximize MDC performance while continuing to investigate integration with discourse-oriented frameworks like PERSUADE.

Conclusions

This research yields valuable insights into the automatic evaluation of argumentative writing and multi-source document analysis. The PERSUADE model, utilizing an open-source scoring algorithm, has demonstrated strong capabilities in identifying discourse elements in student writing with significant accuracy. With an evaluation result of 75%, it highlights the potential of this model to enhance the understanding and quality of argumentative writing. On the other hand, the Multi-Document Clustering model, initially developed with PyTorch and BERT, has shown reliability in clustering documents from various sources, achieving an accuracy of 78% and proving its effectiveness in semantic grouping.

The novelty of this study lies in the comparative evaluation of discourse-based and clustering-based approaches. The demonstration of PERSUADE’s capabilities emphasizes the value of fine-grained discourse analysis, while the MDC model illustrates the potential of semantic embeddings for multi-source document clustering. Beyond these baselines, this research confirms that advanced encoders such as RoBERTa and DeBERTa further improve the MDC framework, with DeBERTa achieving the strongest results across clustering metrics and classification accuracy. This finding highlights that MDC is not only effective with BERT but also scales significantly better with richer contextual embeddings.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. The dataset, although extensive, is restricted to argumentative essays written by U.S. students, which may affect generalizability to other cultural and linguistic contexts. The computational infrastructure used in this research may also not be accessible to all researchers, especially when employing resource-intensive models like DeBERTa. Furthermore, while this study focused on transformer-based encoders, future comparisons could benefit from including a broader range of NLP architectures. The evaluation framework, primarily based on F1-score, accuracy, and clustering metrics, may also be expanded to capture more nuanced error patterns.

Future research directions should focus on several key areas. First, integrating the discourse analysis strength of PERSUADE with the semantic clustering power of MDC enhanced by advanced encoders could yield a comprehensive system capable of both micro-level argument evaluation and macro-level clustering. Second, incorporating other state-of-the-art encoders such as XLNet, ELECTRA, or LLaMA-based models may provide even stronger contextual representations, enabling more robust performance across languages and domains. Third, expanding experimentation to cross-linguistic datasets would test the adaptability of these models beyond English essays, making the approach more globally applicable. Fourth, efficiency-focused research, including distillation techniques and lightweight transformer variants, should be explored to make high-performing models like DeBERTa more accessible in resource-constrained environments such as schools. Finally, embedding this framework into real-world educational platforms could provide direct pedagogical value, offering automated yet nuanced feedback to students and assisting teachers in monitoring writing quality at scale.