A vector database solution for rational design of CRISPR defense-avoidant phage therapy

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Paulo Jorge Coelho

- Subject Areas

- Bioinformatics, Computational Biology, Data Mining and Machine Learning, Databases, Emerging Technologies

- Keywords

- CRISPR, Phage therapy, Vector databases, C. difficile

- Copyright

- © 2025 Kirillov

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2025. A vector database solution for rational design of CRISPR defense-avoidant phage therapy. PeerJ Computer Science 11:e3427 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3427

Abstract

Recently the field of phage therapy has gained considerable interest due to its potential benefits as an alternative to traditional antibiotics. Unfortunately, the effectiveness of phage therapy can be hindered by Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats-CRISPR-associated proteins (CRISPR-Cas) systems present in many bacterial pathogens. In this study, we propose a method to select in silico effective phages capable of bypassing CRISPR defense mechanisms. Our approach is based on a vector database made from protospacers that were found in phage genomes equipped with a distance function that allows for accurate comparison of sequences and a retrieval algorithm that offers fast selection of the phages that are the hardest to suppress by a CRISPR system of interest. By leveraging these resources, our technology can rapidly generate candidate phage cocktails tailored to the specific needs of each individual patient, taking into account their unique infection profile and the presence of CRISPR-Cas systems within the offending bacterial strains. The approach has been tested on a simulated scenario of Clostridium difficile outbreak.

Introduction

The basic premise of phage therapy is that if one wants to eradicate bacterial infection, one should enlist the primordial enemies of bacteria—viruses that prey on them, bacteriophages. While in the eyes of modern healthcare providers, phage therapy is a new solution that promises to kill even the most antibiotically resistant infections, in fact, the first applications and even a long tradition of phage therapy’s clinical use predate the invention of antibiotics itself (Anyaegbunam et al., 2022). In the Soviet Union, similarly to Western countries, phage therapy was first introduced during the 1920s and gained significant support from the government through heavy investment in microbiological research and the establishment of dedicated bacteriophage institutes (e.g., George Eliava Institute of Bacteriophages, Microbiology and Virology; Myelnikov, 2018). During World War II, phage therapy was extensively used by the military for treating various diseases such as dysentery, wound infections, and cholera, further establishing its legitimacy as a medical treatment option (Summers, 2012); however, after the invention of penicillin and other antibiotics, they were preferred over phage therapy due to their broader applicability and easier scalability.

Unlike Western countries, phage therapy continued to be used and researched in the Soviet Union even after World War II and introduction of antibiotics due to factors like political isolation during the Cold War, which allowed researchers to pursue the technique independently of Western dismissal. Today, phage therapy remains a routine medical practice in countries such as Georgia, Poland, and Russia (Yang et al., 2023).

Currently due to the emergence of multiresistant bacterial strains (Huemer et al., 2020) and lack of effective treatments to combat multiresistance, interest towards phage therapy among scientists, medical professionals and regulators, undergoes a certain revival. The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has exhibited a growing receptiveness towards phage therapy, fostering the initiation of clinical trials (Swenson, Gonzalez & Steen, 2024). Substantial financial backing from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (National Institutes of Health (NIH), 2021), totalling $2.5 million allocated across 12 international research institutions, signifies a rising institutional commitment to advancing phage therapy research. The United Kingdom’s government reacted (GOV.UK, 2024) to the report by the Science, Innovation, and Technology Committee on the antimicrobial potential of bacteriophages (phages) underscoring the vital role these viruses could play in tackling antimicrobial resistance (AMR) by assessing the safety, effectiveness, and research translation of phages, with regulatory entities such as the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) expected to offer guidelines for phage licensing, manufacturing standards, and clinical trial procedures. The UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) contributes to this effort by expanding its bacteriophage collection to facilitate research and clinical applications (UK Health Security Agency, 2024).

Unfortunately, the problem of rational design for phage therapy remains difficult due to many reasons, namely, individuality of bacterial infection and complex co-evolutionary dynamics of phages and bacteria absent in case of antibiotics, but the major reason is very similar to the one that reduces the effectiveness of antibiotics—bacterial resistance. Bacteria exhibit a variety of complex and multifaceted immune strategies to combat bacteriophages, which may be divided into innate and adaptive defenses (Abedon, 2012). Innate immunity includes mechanisms such as restriction-modification systems, which protect the bacterial genome by marking foreign DNA for degradation and cleavage (Rodic et al., 2017), Bacteriophage Exclusion (BREX; Drobiazko et al., 2025) systems, phage growth limitation system (Hoskisson, Sumby & Smith, 2015) and other toxin-antitoxin systems (Jurėnas et al., 2022). Innate immunity systems can discriminate between host and non-host molecules, but they are automatic and cannot change with experience. Adaptive immunity forms a more sophisticated level of defense by adding a trainable “memory.” An example of adaptive immunity, Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) systems are prevalent in bacteria and serve as an effective immune response against infections like phages and plasmids (Wang & Leptihn, 2024). The Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats-CRISPR-associated proteins (CRISPR-Cas) systems can recognize and cut the DNA of invading phages, thereby preventing their replication.

Understanding and addressing CRISPR defense is an essential step for optimizing phage therapy approaches. CRISPR systems are adaptive (in contrast to restriction-modification systems which recognize specific DNA sequences but have no immunological memory (Arias et al., 2022)) immunity systems that consist of CRISPR arrays and a set of CRISPR-associated (Cas) proteins. CRISPR arrays are comprised of regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats that perform a structural function and non-repeating DNA sequences, spacers, that contain genetic information about previously defeated infections (Mojica et al., 2005). If a bacterial colony had encountered a phage and survived, its ancestors carry information that can be reused to survive another infection of this phage by producing a Cas-guide RNA (Cas-gRNA) complex from a spacer saved in a CRISPR array. CRISPR systems can be a part of the bacterial chromosome (e.g., CRISPR-Cas system of Escherichia coli (Brouns et al., 2008)) and also can be carried on a plasmid, just like genes of antibiotic resistance (for example, the Type IV CRISPR-Cas system of Klebsiella pneumoniae (Kamruzzaman & Iredell, 2020) which is indeed carried by a multidrug resistance plasmid). As a part of bacterial chromosomes, the CRISPR systems are inherited vertically from a parent bacterium to its successors, while as a part of a plasmid, the systems can be transferred horizontally across different bacterial strains, as exemplified by the global horizontal spread of CRISPR-carrying plasmids amongst the clinically relevant Klebsiella genus (Long et al., 2023). Any phage therapy design software should take into account both ways of inheritance.

CRISPR defense mechanisms pose a significant challenge to phage therapy and are crucial for bacterial survival and proliferation, yet currently the assessment of CRISPR immunity of the bacterial infection before attempting to design and use phage therapy is not a part of common practice due to a number of technical, economical and regulatory challenges, such as the diversity of CRISPR-Cas systems (Balcha & Neja, 2023), clinician’s preference of empirical methods over mechanistic investigations (Caflisch, Suh & Patel, 2019), possible intellectual property concerns and the necessity of regulatory body approval for use in the clinical setting (Pacia et al., 2024).

To counteract this bacterial defense, some phages have evolved anti-CRISPR (Acr) proteins (Duan et al., 2024). These Acr proteins can bind to CRISPR components and inhibit their function, allowing the phages to infect bacteria with active CRISPR defenses. Engineered phages carrying genes encoding Acr proteins have shown improved antibacterial effects against multidrug-resistant bacteria like Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Qin et al., 2022). Nevertheless, the usage of engineered phages may be out of reach for most clinical centers of the world due to technical complexity, financial and resource constraints as well as regulatory hurdles.

An alternative option to engineering or using naturally occurring Acr proteins would be to select the components of a phage cocktail with the specific goal of avoiding CRISPR defence. A number of computational studies that involve design of a therapeutic phage cocktail propose using information about phage-host interaction networks (e.g., PhageCocktail; Díaz-Galián, Vega-Rodríguez & Molina, 2022). CRISPR defense avoidance was proposed as a phage therapy design goal recently in a review (Bleriot et al., 2024) that suggested introducing single nucleotide substitutions into or a complete deletion of the Protospacer-Adjacent Motif (PAM) region in the phage genome (as well as adding Acr proteins or using phages with naturally occurring ones), but the current work is the first one that provides computational design of CRISPR-resistant phage cocktails.

To select CRISPR-avoiding phages, firstly, one would need to extract CRISPR arrays from the sequenced clinical sample of bacterial infection (using, for example, CRISPRCasFinder (Couvin et al., 2018), CRISPRCasTyper (Russel et al., 2020) or CRISPRloci (Alkhnbashi et al., 2021)). After that, one would need to choose among the phages that share this bacterium as a host a phage that does not possess any protospacers corresponding to the spacers in the CRISPR arrays. We propose a solution for the latter step—a method for rational selection of CRISPR-avoiding phages.

A naive solution for this problem involves building a local Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) base from phage genomes and querying it with the spacer sequences. While the naive solution may seem straightforward, it has several limitations that make it less effective. BLAST is a general alignment algorithm and there is room for improvement in particular applications of string alignment. For instance, BLAST time complexity (Altschul et al., 1990) is quadratic for the worst case and its space complexity also scales linearly with database size, while our method provides sublinear complexity of queries.

The naive method overlooks diversity of CRISPR-Cas systems—there are different types of CRISPR-Cas systems (e.g., type I, II, and III), each with unique spacer recognition mechanisms and thus may miss phages that can evade a specific CRISPR-Cas system but might be vulnerable to others. Additionally, the BLAST algorithm may fail to predict the presence of protospacers in phage genomes, especially for longer sequences or when there are multiple similar sequences in the database. This could lead to false positives (selecting a phage that is susceptible to the CRISPR-Cas systems) or false negatives (missing a phage that is resistant to the CRISPR-Cas systems). Overall, the BLAST-based solution is extremely sensitive to the parameters of database construction and search.

To improve upon the local BLAST-based naive method, we propose VDPhage—a method to select the phage cocktail based on vector databases (Ma et al., 2023) with Hierarchical Navigable Small World (Malkov & Yashunin, 2018) structure (HNSW). Vector databases are becoming increasingly popular in the realm of information retrieval and text analysis due to their efficiency and scalability. They are able to represent high-dimensional data, making it possible to capture complex relationships between words that are often overlooked in traditional keyword-based search methods. Ultimately, the primary motivation for using vector database technology stems from the need to optimize computational efficiency in handling vast amounts of bioinformatics data. Traditional databases often suffer from scalability issues, particularly when dealing with queries that require real-time responses. The hierarchical structure of the vector database provides a more organized and accessible layout, facilitating faster search algorithms and reducing the complexity of query processing. This high-dimensional space makes possible efficient vector operations, such as inner product computation and similarity calculation. For phage selection, we design special embeddings that allow for sublinear selection of the phages that have the most dissimilar CRISPR protospacer profile compared to the clinical sample of interest.

Methodology

A baseline approach to select CRISPR-resistant phages with local BLAST

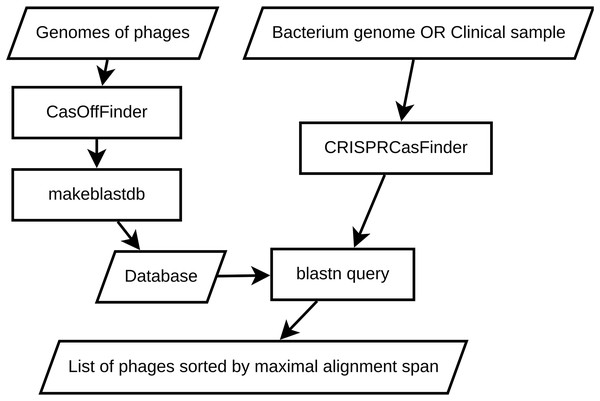

This section outlines a straightforward approach for selecting phages based on local alignment with CRISPR spacers using BLAST (Altschul et al., 1990). It provides a starting point for researchers aiming to reduce immune responses between phages and bacterial hosts with CRISPR systems. A schematic representation of the pipeline is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: An overview of local BLAST baseline.

To develop a baseline approach for selecting CRISPR-resistant phages, we employed a combination of bioinformatics tools and techniques. The pipeline involves constructing local BLAST databases from phage genomes and querying them with the CRISPR spacers extracted from a reference genome of the bacterium we are interested in (or CRISPR spacers extracted from a sequenced clinical or metagenomic sample). This enables us to perform targeted searches against the protospacers to identify potential CRISPR-resistant phages with high confidence. This method was chosen for its simplicity and efficiency in comparing DNA sequences, as well as its omnipresence in bioinformatics.

In this section, we describe the detailed methodology for each stage of our approach, including database construction, BLAST search execution, and result analysis. We also discuss the various parameters and considerations that need to be taken into account to ensure accurate and reliable results.

The foundation of our baseline approach is the creation of local BLAST databases containing reference genomes of phages. To achieve this, we first have to obtain genomic sequences from publicly available databases, such as NCBI’s GenBank, PhageDB or INPHARED (Cook et al., 2021). After obtaining the phage sequences, we have to use a string search tool (e.g., CasOffFinder; Bae, Park & Kim, 2014) to find all possible protospacers in the phages. This step is required to ensure that we are comparing spacers with potential protospacers instead of an arbitrary collection of substrings from the phage genomes. A protospacer here is defined as a substring that is located nearby Protospacer-Adjacent Motif—a special set of sequences that CRISPR-associated protein uses to recognize the target DNA sequence (Mojica et al., 2009). The exact length and location of the protospacer in relation to PAM varies highly between different CRISPR systems (Shah et al., 2013), so the exact description of the protospacer-PAM combination is left for the end user, e.g., YCNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNN for Clostridium difficile where YCN is the PAM (Maikova et al., 2021) and the rest is a mask for the protospacer string. In the latter sections, we provide a case study of designing a phage cocktail targeted to evade a well studied CRISPR-Cas system of C. difficile.

To look for protospacer+PAM combinations, we use CasOffFinder (Bae, Park & Kim, 2014) with an all-permissive string mask. CasOffFinder enables GPU-accelerated search for strings in large genomes. It was initially developed to search for off-target editing sites, but with an all-permissive string mask and allowed number of mismatches equal to the length of protospacer, it can be used to select all possible pairs of protospacer and PAM. After gathering all potential protospacers, we employ makeblastdb tool from BLAST+ suite (Camacho et al., 2009) to create local BLAST databases. We opt for the nucleotide-nucleotide search mode to compare the query spacer sequences against the protospacers from our database. These protospacers represent potential targets for CRISPR defense.

Once the local BLAST databases are constructed, we can proceed with the identification of CRISPR-resistant phage candidates. To achieve this, we first have to extract the spacer sequences from the bacteria of interest. This output provides critical information about the CRISPR-Cas elements within the input sequences, which are essential for understanding potential targets for phage therapy. We can do the extraction using CRISPR-Cas systems annotation tools like CRISPRCasTyper (Russel et al., 2020), CRISPRloci (Alkhnbashi et al., 2021) or CRISPRCasFinder (Couvin et al., 2018) (which we decided to use based on its widespread adoption in the field of CRISPR-Cas research). We choose to run CRISPRCasFinder via the provided Singularity container. While CRISPR-Cas annotation tools provide information beyond CRISPR array content (e.g., location of Cas proteins, type of CRISPR-Cas system and so on), we mainly use only the spacer sequences.

We then need to perform BLAST searches against the local phage databases using the blastn tool from the BLAST+ suite. The choice of parameters is critical to achieving accurate and reliable results. Our BLAST search is unusual—while in a typical search, we would like to look for the most similar sequences to the query (Altschul et al., 1994), here we are looking for the sequences that are not similar since we are interested in the phages that do not contain targetable protospacers. We want to get as many sequences as possiblie to reduce the probability of selecting the wrong phages. Therefore, our parameter choice is as follows—evalue is 105 (unlike typical BLAST search that would use evalues like ), max_target_seq is 106 (while BLAST default is 500). We also use a word size of 11 to balance sensitivity and efficiency.

From that, the selection of phage cocktail components is a simple rearrangement of the BLAST search result according to their similarity to the query. Let be the i-th protospacer (of I protospacers possible) from the n-th phage (of N total phages) that corresponds to the query spacer (of Q total queries). Such a protospacer-query pair is represented by the alignment which can be characterized by the length of the largest aligned portion, . In order to find the most dissimilar phage, we have to solve the following optimization problem:

(1)

We are interested in a phage (or phages) that has the smallest maximal alignment length among its protospacer-query pairs. By sorting and selecting the top phages with the smallest maximum alignment lengths, we can identify a promising composition for a CRISPR-resistant phage cocktail of size .

Vector database with hierarchical navigable small world structure

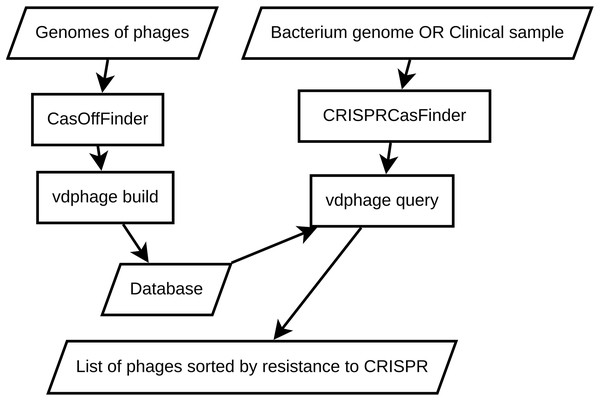

To address the shortcomings of the baseline BLAST approach, we introduce VDPhage—a novel vector-based database solution designed with a HNSW structure. The core concept behind this approach is to transform protospacer sequences into high-dimensional vectors while preserving their sequential similarity and then navigate this vector space efficiently following the small world structure. A schematic representation of the VDPhage pipeline is shown in Fig. 2. VDPhage pipeline follows closely the baseline described in previous section, only substitutes the local BLAST database for vector and ordering by maximal alignment length for ordering by minimal cosine distance.

Figure 2: An overview of the proposed VDPhage pipeline.

The incorporation of a layered navigable structure further enhances the database’s functionality by enabling efficient navigation through interconnected nodes. By leveraging these structural features, the vector database offers significant advantages over traditional database systems like BLAST.

The HNSW graph (Malkov & Yashunin, 2018) is an extension of k-nearest neighbors (k-NN) proximity graphs. A k-NN proximity graph is an undirected graph weighted by distance between its nodes (e.g., alignment score or other forms of distance between sequences) where the only links that exist are the connections between the closest nodes. Search in an exact k-nearest neighbor proximity graph involves greedy traversal over the links starting from a (generally) random node. Such a search scales linearly with the size of the graph, therefore for performance’s sake, various approximations to the exact k-NN algorithm had been developed.

HNSW introduces two main improvements to the exact k-NN search—navigability and hierarchy. Navigability follows from the Kleinberg’s small world model (Kleinberg, 2000), which itself is an extension of Watts-Strogatz graph (Watts & Strogatz, 1998). In Kleinberg’s model, there are two types of connections between nodes—short connections that link closest neighbors and long connections that link nodes at random with probability inversely proportional to their weight (distance between sequences). Addition of long connections allows for complexity of search (Kleinberg, 2000).

Hierarchy in HNSW involves separation of the navigable proximity graph into layers according to their distance. The greedy search commences starting from the top layer to bottom layer, and on each iteration only a small portion of connected nodes are thus traversed. This allows for reduction of search complexity from to (Malkov & Yashunin, 2018).

For our HNSW engine, we use Usearch library (Vardanian, 2023). Usearch is an advanced, open-source vector database solution designed for efficient searching and clustering within diverse applications involving vectors and strings. Utilizing high-performance algorithms such as HNSW, Usearch offers customizable metrics support and low-latency performance through native language bindings. Its compact codebase and minimal dependencies make it a lightweight alternative to other tools like FAISS (Douze et al., 2024). With built-in capabilities for clustering, dimensionality reduction, and multi-language support, Usearch excels in scalability and deployment ease. To work with Usearch, we use the vicinity (van Dongen et al., 2024) library that provides a simple and uniform interface for different vector database engines.

For the construction of the vector database, the sequences undergo feature extraction, which involves transforming the raw genetic information into high-dimensional vectors. This transformation could be in principle achieved using advanced machine learning techniques, such as word embeddings or sequence-to-vector models like dna2vec (Ng, 2017), kmer2vec (Ren, Yin & Yau, 2022) or kmer-node2vec (Yu et al., 2022); however, we strive for simplicity and use the following simple transformation (Algorithm 1).

| Data: Spacer or protospacer DNA sequence S, length of k-mers k |

| Result: Vector V of size 4k |

| vector of all possible k-mers of given k; |

| vector of zeroes of length 4k; |

| ; |

| while not at end of this sequence do |

| substring of S from i to ; |

| ; |

| while j do |

| if then |

| ; |

| end |

| ; |

| end |

| ; |

| end |

| ; |

This is a classical method (consult Moeckel et al., 2024) for a thorough modern review of k-mer methods, we use the Rust implementation of Weber (2024)) of alignment-free sequence comparison and it fits perfectly within the framework of vector databases. We compute k-mer frequencies and use them as our embeddings for the vector database. This allows us to introduce cosine distance between two embeddings as our distance between spacer and protospacer.

(2) where S and P are spacer and protospacer strings respectively, represents dot product and ||X|| represents the magnitude of the vector.

The next stage involves the creation of the hierarchical structure of the database. This hierarchy organizes the vectors into clusters based on their similarity, facilitating efficient data retrieval during query processing. The navigable small-world property allows for faster traversal through the network, enabling users to quickly access related sequences and associated labels. This results in a robust and efficient database system that ensures that each genetic sequence is accurately represented and organized in a manner that maximizes retrieval speed and usability. Construction of the HNSW is because it is constructed by a consecutive search of elements of the data (Malkov & Yashunin, 2018).

When a user submits a query to the vector database, the system utilizes its hierarchical structure to quickly narrow down potential matches. The small-world organization allows the database to efficiently partition the high-dimensional vector space into clusters, enabling the search algorithm to focus on relevant regions of the space rather than scanning the entire dataset. This drastically reduces the complexity of the search process and accelerates query execution times. With the small-world network, users can navigate directly to related sequences through interconnected nodes, significantly reducing query response times and improving overall usability, unlike the traditional relational database that requires navigating of a series of linear lists that result from specific queries.

A design for comparison study between the baseline and VDPhage

We test our approach for CRISPR-resistant phage cocktail design on a simulated scenario of C. difficile infection. We use reference genome of C. difficile strain S-0253 (NCBI, 2025a) as a source of CRISPR spacers and a selection of Clostridioides phages from NCBI virus database (NCBI, 2025b) as a source of protospacers (70 phages total). Protospacer-Adjacent Motif for CRISPR system of C. difficile is “YCN” (Maikova et al., 2021). In the worst-case scenario, one might expect that the majority of spacers from the native CRISPR-Cas system of the bacteria would exhibit high similarity to protospacers in the vector or BLAST database, leading to potential CRISPR interference and reduced therapeutic efficacy. To assess our approach against this scenario, we have to evaluate the distribution of sequence similarities for best protospacer-spacer alignments. To compute such alignments, we use local BLAST database built on the protospacer sequences found by CasOffFinder with rather standard parameters (e-value of and word size of 11). These alignments would also give us the worst possible selection of phages—a set of phages, all of which do indeed contain protospacers highly similar to ones in the CRISPR array.

This comparison should reveal that our proposed vector database solution effectively reduces the likelihood of selecting phages that have protospacers with high similarity to known spacers, thereby minimizing CRISPR interference. An evidence for that would be a significant difference in distributions of sequence similarities from the best alignments and from the protospacer-spacer pairs that motivate the phage’s ranking in VDPhage or baseline outputs.

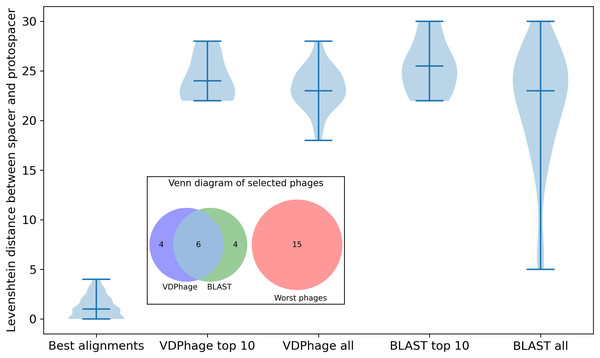

To measure sequence similarity, we use Levenshtein distance—a minimal number of insertions, deletions and substitutions required to turn one string into another (Levenshtein, 1966). To test whether two samples (e.g., best alignments and VDPhage) came from the same distribution, we use Kolmogorov–Smirnov statistics (Smirnov, 1944). We select p-value of as our threshold for rejecting the null hypothesis (two samples came out of the same distribution, N is the number of comparisons, as the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons suggests). In addition to that, we visualize the diverging distributions with violin plots.

The top phages that constitute the proposed phage cocktail of size should not overlap with the worst possible phages. We can check it by computing set intersections of phage lists and visualize it with a Venn diagram.

Results

Performance evaluation

This section describes the evaluation of two proposed algorithms to select CRISPR-resistant phage cocktails. The comparison between two algorithms is based on a simulated scenario of C. difficile infection described in ‘A design for comparison study between the baseline and VDPhage’ of the ‘Materials and Methods’ section. We compare the quality of resulting phage cocktails measured in deviation of sequence similarity distributions from the sequence similarity distribution of best available protospacer-spacer alignments.

In the case of phage therapy design, our objective is to identify a set of phage genomes that could evade the CRISPR-Cas system of a specific bacterial species, thereby offering an effective treatment strategy. To do so, we have to conduct a sequence similarity search using a query representing the CRISPR array of the bacterial species. The HNSW structure of the vector database enables rapid identification and retrieval of phage genomes that share high similarity with the query. The results of Levenshtein distance distribution comparison is shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Violin plot of comparison between VDPhage, BLAST and the worst possible phages that could be selected for the experiment with accompanying Venn diagram that shows the overlaps between VDPhage, BLAST and the worst phages.

All of the selected phages distributions differ highly from the distribution for best available alignments. Cocktails suggested by baseline and VDPhage overlap significantly (six out of 10 for top 10 cocktail), but neither of these methods select any of the worst possible phages. Distributions for BLAST have more variance in Levenshtein distance than the ones for VDPhage which suggests that VDPhage is more robust and consistent at locating the global minimum of sequence similarity. Considering the statistical significance of differences between the distributions (best alignments, VDPhage all and BLAST all), Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (corrected for three comparisons by Bonferroni correction) gives us the following p-values: for BLAST vs VDPhage, for VDPhage vs best alignments and for BLAST vs best alignments. Since our threshold for statictical significance is , we consider significant only differences between best alignments and the rest. In the case of BLAST and VDPhage, we do not have enough evidence to reject the null hypothesis of the distributions being the same.

Runtime evaluation

The runtime evaluation of our proposed vector database solution for CRISPR defense avoidant phage therapy was conducted to assess its efficiency, scalability, and accuracy compared to baseline methods (local BLAST). We have performed 100 of each operations (VDPhage build, VDPhage query, baseline build, baseline query) and computed mean computation time and its standard deviation. Building the baseline database runs much faster than vector database – s vs s respectively. However, the querying is much faster for VDPhage – for extracted records vs for extracted records, which means on average records per second vs records per second. VDPhage extracts a single record almost 26 times faster than local BLAST, which is expected because of logarithmic complexity of the search in HNSW. All experiments were performed on an Alienware 17 R4 laptop with 24Gb of RAM and 2.9 GHz Intel Core i7-7820HK Quad-Core CPU.

Overview of VDPhage CLI application

The VDPhage software is available as a command line interface tool. It supports both vector database and local BLAST methods, outputting a sorted list of phages and the accompanying information on its decisions. The script relies on several external libraries, including “os”, “sys”, “json”, “vicinity”, and “argparse”, which facilitate tasks such as parsing command-line arguments, reading configuration files, handling file input/output operations, executing bioinformatics analyses (e.g., BLAST queries), and managing phage data. VDPhage, as well as the local BLAST baseline, provides two modes of operation:

vdphage build—to construct the vector database (or BLAST database) from a FASTA file of protospacers. The build command constructs a searchable database containing information about protospacers, spacer sequences, and their respective alignments. Additionally, the user has to specify the k-mer length. In the code, build mode is enabled by build_baseline and build_vdphage functions that read the configuration file, create necessary output directories, copy the protospacers file to the output directory, build a BLAST or VDPhage database and save metadata about the build;

vdphage query—to query the database for spacers from bacterial genome (in FASTA file). The query command searches the database for potential protospacer-spacer interactions based on input spacer sequences. Additionally, the user has to specify the number of protospacer-spacer pairs to return (default is 10,000) The query mode is represented in the code with query_baseline and query_vdphage functions that read the configuration from a JSON file, create a temporary directory if it doesn’t exist, perform a BLASTN search or a vector database query with the new spacers against the respective database, parse the results, and save a summary as a TSV file.

The tool can be configured using a JSON configuration file config.json. The configuration file allows users to customize paths to temporary directories and external tools (e.g., k-mer counter), parameters like makeblastdb and blastn options, and other settings specific to the chosen method. The configuration file has the following structure:

-

TEMPDIR—a path to temporary directory (/tmp/vdphage/ by default);

-

PROTOSPACER KMER COUNTS—a name of file with k-mer counts (protospacers.kmer_counts.npy by default);

-

PROTOSPACER KMER COUNT IDS—a name of file with the corresponding identification information (protospacers.kmer_counts.ids.txt by default);

-

COUNT KMERS—a command that runs kmer-counter (the default one is ../kmer-counter/target/release/kmer-counter –collapse 0 –klength KKKK –file INPUTFILE –ids OUTIDS –out OUTFILE). COUNT KMERS takes INPUTFILE with the protospacers or spacers as input and outputs PROTOSPACER KMER COUNTS and PROTOSPACER KMER COUNT IDS;

-

MAKEBLASTDB—a command to run makeblastdb (the default one is makeblastdb -in INPUTFILE -title “Phages local BLAST” -dbtype nucl). MAKEBLASTDB takes the INPUTFILE with protospacers as the input and creates a local BLAST database within the same directory as the input file;

-

BLAST OUT—a filename of BLAST query result (BLAST_QUERY_RESULT.xml by default);

-

BLASTN—a command to run BLASTN (the default one is blastn -query INPUTFILE -db DATABASE -evalue 10000 -num_threads 1 -out OUTFILE -outfmt 5 -max_target_seqs 1000000 -word_size 11). BLASTN takes INPUTFILE with the spacers and the database name DATABASE as the input and outputs the query result into BLAST OUT.

The example commands are as follows:

| ## Build the database |

| python../src/vdphage.py build --protospacers \ |

| ../data/interim/protospacers.fasta -k 4 \ |

| –output ../databases/vdphage --method VDPhage \ |

| –config ../configs/config.json |

| ## Query the database |

| python ../src/vdphage.py query --config ../configs/config.json \ |

| -n 10000 –output../data/processed/vdphage_ranking.tsv \ |

| --spacers ../data/interim/spacers.fasta - \ |

| -database ../databases/vdphage |

The functionality of vicinity library for NHSW computations is encapsulated in a VicinityWrapper class that exposes __init__ and query methods. The initialization method __init__ creates the VicinityWrapper object with protospacers, spacers, and a database (V), loads the spacers from the provided list spacers, loads the protospacers from the provided list protospacers, which includes both protospacers and associated phages, stores the loaded database in self.db attribute, stores the loaded spacers in self.spacers attribute after loading them using a custom function load_spacers(), extracts unique phages from the protospacers with np.unique() and stores them in self.phages attribute after converting them to a numpy array.

The query method queries the database with a given vector qv and returns a summary dataframe. It performs a query on the loaded database using self.db.query() method with the provided query vector qv and keyword argument k. Then it concatenate dataframes for each spacer in the spacers dictionary. Each dataframe contains information about spacers, protospacers, distances, queries, and hits. After that a new column phage is added to the dataframe by splitting the protospacer column and extracting the phage ID. Then any phages that are not present in the queried results are identified and added to the dataframe with default values. The modified dataframe is then concatenated with the additional rows for absent phages. After that, a summary dataframe with minimum distances, spacers, protospacers, queries, hits, and phage IDs grouped by phage is created and sorted in descending order based on the distance column to prioritize longer minimal distances. Then the query method calculates the Levenshtein distance between query strings and their corresponding hit strings and adds it as a new column levenshtein to the summary dataframe. The resulting dataframe is then returned from the method and saved to the output file.

The example phage cocktail of size 5 (top five results) selected by VDPhage is shown in the Table 1. Here “phage” column denotes the accession number of a phage, “spacer” column denotes the spacer with the minimal cosine distance of a spacer-protospacer pair matched to that phage. Each spacer is represented as the accession number of the bacterial genome followed by chromosome, start and end position. The cosine distance itself is shown in “distance” column and “levenshtein” column shows the Levenshtein distance between spacer and protospacer in the pair with minimal cosine distance.

| Phage | Spacer | Distance | Levenshtein | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | AY522334.1 | CP076401.1:1494942:1494978 | 0.594919 | 24 |

| 4 | AY522341.1 | CP076401.1:2257027:2257062 | 0.439270 | 22 |

| 2 | AY522336.1 | CP076401.1:1780944:1780980 | 0.363345 | 28 |

| 41 | OK557798.1 | CP076401.1:1494550:1494585 | 0.347422 | 24 |

| 3 | AY522340.1 | CP076401.1:1494681:1494716 | 0.344655 | 22 |

Discussion

The study proposes two algorithms for selecting components of a phage cocktail capable of bypassing CRISPR defense mechanisms. The BLAST-based baseline established in the current study serves as a benchmark for CRISPR-avoidant phage therapy design by providing a simple solution to search for therapeutic candidates through precise sequence comparisons, high-confidence spacer extraction, and streamlined data analysis. It can be used as a starting point in further studies of CRISPR avoidance.

The improved, vector database method, VDPhage, is built upon this baseline and, together, they constitute the first generation of dedicated in silico CRISPR-avoidant phage therapy design tools. By utilizing vector databases to index sequences, VDPhage demonstrates sublinear complexity of query and excels in computational efficiency and speed, operating 26 times faster per record compared to the BLAST method. We deliberately selected a k-mer frequency approach to generate sequence embeddings due to its simplicity. While more complex, learned embeddings from deep learning models (e.g., DNA language models (Penzar et al., 2023; Avsec et al., 2025), capsule networks (Kirillov et al., 2022; Kirillov & Panov, 2022)) can capture higher-order features, their utility often depends on large volumes of labeled data and significant computational resources for training. For the task of initial, large-scale screening of CRISPR arrays from bacterial genomes and/or metagenomes against a vast space of possible CRISPR protospacers, the simplicity and speed of our chosen approach provide a distinct practical advantage.

We have tested our algorithm on a simulation of C. difficile infection. The choice of C. difficile for the proof-of-concept study was motivated by the following reasons: its clinical significance as the leading cause of hospital-acquired infections (Kwon, Olsen & Dubberke, 2015; Le Monnier, Zahar & Barbut, 2014), simultaneous resistance of many strains against commonly prescribed oral antibiotics (metronidazole, vancomycin, and fidaxomicin (Peng et al., 2017)), a functional CRISPR-Cas system present in nearly 100% of the strains (Mortensen, Lam & Ye, 2021), as well as demonstrated existence of working phage therapies for C. difficile infections (Selle et al., 2020; Nale et al., 2022; Venhorst, van der Vossen & Agamennone, 2022). These factors—its clinical importance, a strong CRISPR-Cas system, and the established response to phage therapy—position this simulation of C. difficile infection as a comprehensive case for testing the proposed algorithms.

VDPhage does require a set of assembled phage genomes for database construction, however, this is not an inherent limitation but rather a standard input requirement that any other algorithms would be subject to as well. Importantly, the algorithm’s querying phase only requires CRISPR arrays, which can be efficiently extracted even from unassembled metagenomic data using specialized tools like MCAAT (Talibli & Voß, 2025) or Crass (Skennerton, Imelfort & Tyson, 2013). Although specific testing on plasmids harboring CRISPR arrays was not conducted, the demonstrated functionality on CRISPR arrays extracted from a bacterial chromosome suggests broad applicability and adaptability across various input sources.

The development of CRISPR defense resistant phage therapy holds considerable promise as an innovative approach to combat bacterial infections. However, the translation of this promising concept into clinical practice necessitates rigorous validation through well-designed experimental frameworks. To validate and refine the algorithm’s predictions, several experimental approaches can be employed. Bacterial infection models using strains with known CRISPR-Cas systems can challenge the algorithm’s predicted evadees (Fabijan et al., 2019; Parmar et al., 2024), with phage fitness quantified via plaque assays (Daubie et al., 2022), qPCR (Refardt, 2012), or flow cytometry (Melo et al., 2022). Appropriate pathogenic bacterial models (e.g., C. difficile, E. coli) and animal models (e.g., murine or porcine; Mehmood Khan et al., 2023) should be selected to evaluate safety, efficacy, and bacterial burden reduction, with high-throughput methods like imaging or real-time PCR used to detect subtle differences in phage performance. Alternatively to animal studies, organoid modeling using three-dimensional cell cultures that replicate the structure and function of human organs could be a highly relevant platform for modeling of bacterial infection and its eradication with phage therapy in realistic conditions (Aguilar et al., 2021; Zivkovic & Opacak-Bernardi, 2025). Finally, the synergistic potential of designed phage cocktails should be evaluated by testing their combined ability to reduce bacterial load. The development of CRISPR defense avoidant phage therapy involves several layers of ethical considerations and regulatory challenges (Anomaly, 2020). Ethically, researchers must ensure animal welfare during preclinical testing and obtain informed consent for human trials while protecting patient privacy. Ensuring equitable access to this treatment is vital to mitigate health disparities. Additionally, transparent data sharing and intellectual property rights are essential for fostering innovation. Regulatory oversight plays a critical role in balancing safety, efficacy, and innovation. Comprehensive research adhering to ethical guidelines will help ensure that CRISPR defense avoidant phage therapy is both safe and accessible, paving the way for its responsible use in treating infectious diseases (Yang et al., 2023).

CRISPR avoidance as an approach to phage therapy design in general and VDPhage in particular are subject to several limiting factors. First of all, there are a large number of other bacterial immune systems, such as BrEx, restriction-modification etc. These systems are not covered by VDPhage and require dedicated tools for phage selection. If we consider a general pipeline for selection of phage therapy that is robust to every (or the majority of) known bacterial immunity systems, CRISPR avoidance should be included as one step amongst many, but adding avoidance of other bacterial immune systems or additional filtration (e.g., whether the phage has a naturally occurring Acr protein) is out of scope of the current study. We focus on CRISPR avoidance and, following the Unix way of software development, we develop a tool that does only one thing and does it well (Ritchie & Thompson, 1978). Flexibility and modularity of phage therapy design pipelines is essential for addressing the multifaceted challenges posed by bacterial immunity.

Secondly, many pathogenic bacteria lack functional CRISPR-Cas systems, for example, only 2.9% of S. aureus strains possess working CRISPR-Cas system (Mikkelsen et al., 2023) and among those only about 9% of spacers point to known bacteriophages and plasmids (Cruz-López et al., 2021). CRISPR avoidance matters for phage therapy against bacteria with functional and widespread (amongst the strains of the bacteria) CRISPR defence, such as C. difficile and K. pneumoniae, and, for other bacteria, this step can be omitted.

The ongoing evolutionary competition between bacteriophages and their bacterial hosts has spurred significant molecular innovation. Phages have evolved sophisticated counter-strategies against bacterial defence, such as mutating target sites and producing anti-CRISPR proteins. The dynamic interplay between hosts and phages has led to the frequent horizontal transfer, repurposing, and reshuffling of genetic elements—such as nucleases and defensive components. These recruited genetic modules, often of unknown or diverse origins, are deployed as molecular weapons in the conflict, blurring the boundaries between bacterial defensive and offensive mechanisms (so-called “guns for hire” exaptation; Koonin, 2019; Medvedeva et al., 2019; Faure et al., 2019; Koonin, Makarova & Wolf, 2017). Considering phage therapy, co-evolution leads to phages losing their potency against pathogenic bacteria, which negatively affects the clinical outcomes of phage therapy (Woolhouse et al., 2002; Blasco et al., 2023). Within the VDPhage framework, there is only one way to weather the co-evolution problem—continuously updating phage databases based on novel clinical data.

In comparing methodologies for obtaining bacteriophages resistant to bacterial CRISPR systems, there is a notable trade-off between performance and resource allocation. Directly engineering phages to evade CRISPR immunity (for example, by adding an Acr protein (Qin et al., 2022)) offers superior performance compared to selection of a natural one (including through VDPhage) but involves significant time and financial investment due to the complex biological modifications required. Conversely, the VDPhage algorithm presents an efficient alternative by leveraging precompiled databases of existing phages.

In summary, our primary contribution is the development of two novel algorithms designed to select phages in silico that can survive the CRISPR immunity of a specified bacterial infection, a naive BLAST-based solution and a vector database-powered tool, VDPhage. By leveraging vector database technology, our VDPhage algorithm significantly outperforms the BLAST-based one in terms of phage query runtime. Consequently, this method can be effectively integrated into a phage therapy selection pipeline to filter proposed phage cocktails, ensuring they are resilient to the host’s CRISPR-based immune defenses.