CoAgt: unleashing the reasoning capabilities of large language models on tabular data with a chain of agents

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Armin Mikler

- Subject Areas

- Human-Computer Interaction, Agents and Multi-Agent Systems, Artificial Intelligence, Computational Linguistics, Natural Language and Speech

- Keywords

- Chain of agents, Large language models, Long tables, Natural language questions, Table reasoning

- Copyright

- © 2025 Alrayzah and Alqhtani

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2025. CoAgt: unleashing the reasoning capabilities of large language models on tabular data with a chain of agents. PeerJ Computer Science 11:e3423 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3423

Abstract

Large language models (LLMs) have shown remarkable progress in text-based reasoning, but they continue to struggle with large and complex tables. Token limitations and the loss of structural dependencies make it difficult for a single model to extract evidence, connect relationships, and produce reliable answers. To address this challenge, we introduce Chain of Agents (CoAgt) a multi-agent framework inspired by how human reason with tables, scanning data, comparing values, retaining information, and making decisions. In CoAgt, different agents share the workload: Collectors gather evidence from subtables, the Synthesizer integrates their findings into a coherent answer, and the Refiner ensures clarity and correctness. This division of labor makes the reasoning process both scalable and interpretable, while reducing the risk of errors that often occur when one model handles all steps alone. We evaluate CoAgt on two widely used benchmarks. On WikiTableQuestions (WikiTQ) it achieves 85.4% accuracy, outperforming the strong Chain-of-Table baseline by more than twenty-five percentage points. On Table Fact-Checking (TabFact) it reaches 96.6% accuracy, exceeding previous state-of-the-art results. These findings show that breaking reasoning into specialized agents not only improves performance but also offers a transparent and reliable approach for reasoning over large, complex tables.

Introduction

Tables are one of the most common ways to organize structured information in real-world settings. They are widely used in areas such as business analysis, scientific reports, and government records. Online tables, especially those found on platforms like Wikipedia, cover a wide variety of content, from historical facts to comparative statistics, and are often consulted by users looking for clear information (Lu et al., 2024). However, despite progress in natural language processing, large language models (LLMs) still face challenges when working with long or complex tables. Since they are mainly trained on plain text, they lack the built-in ability to represent and reason over the two dimensional layout of rows and columns. As a result, they often struggle to capture schema relationships, align information across rows and columns, or perform tasks like filtering, grouping, and aggregation. On top of that, LLMs are limited by input length (Nahid & Rafiei, 2024). With large tables containing many rows or attributes, parts of the table such as headers, metadata, or important rows may be cut off. This often reduces reasoning accuracy and increases the chance of incomplete or incorrect answers.

By contrast, when a person is presented with tabular data and asked a question such as ‘Who scored the most goals?’ or ‘Which country has the highest population?’, their brain engages in a complex and intelligent process that integrates visual perception, working memory, pattern recognition, and logical reasoning. This begins with visual scanning, as the eyes move across the table to locate relevant columns such as ‘goals’ or ‘population’. The brain identifies patterns, such as high values, bolded text, or outliers. Based on the focus of the question, it selects and interprets the target column, mapping abstract concepts like ‘most’ to concrete numerical values. The brain then performs step-by-step comparisons, mentally tracking the current top entry and updating this as new data is processed. Key details are held in working memory, although this capacity is limited and prone to overload in large tables. Once sufficient data has been reviewed, the brain synthesises the information to reach a final decision. If there is uncertainty, the individual may re-scan the table to confirm the result.

In this work, we identify two core limitations in the current landscape of table-based question answering. First, to the best of our knowledge, no existing model can extract answers effectively from large tables without using structured query language (SQL). Second, current LLMs are unable to process long tables due to context-length constraints and schema misalignment (Nahid & Rafiei, 2024).

To address these limitations, we propose CoAgt, a novel framework based on a chain-of-agents approach with a zero-shot learning mechanism to generate answers from dependent rows and columns in long tables. We evaluate CoAgt on two benchmark table reasoning datasets: WikiTableQuestions (WikiTQ) (Pasupat & Liang, 2015) and Table Fact-Checking (TabFact) (Chen et al., 2019). Our evaluation on table-based question answering and fact verification tasks shows that our method outperforms existing models. Furthermore, it can extract answers from large tables without requiring the learning or generation of SQL queries.

Despite recent progress, LLMs inherently struggle with relational reasoning over tabular data. This difficulty stems from the fact that transformer architectures are pretrained primarily on one-dimensional sequences of text and therefore lack 2D structural biases necessary to capture the grid-like relationships between rows and columns (Fang et al., 2024). When tables are linearized into token sequences, row–column alignments become obscured, and dependencies across multiple dimensions are easily lost. Such linearization artifacts often result in mismatched values, overlooked column headers, or errors in mapping questions to the correct table attributes. Furthermore, relational operations common in tabular reasoning such as filtering, aggregation, and cross-column comparison, are not natively supported by sequence-based pretraining objectives (Li et al., 2024). These limitations are compounded by token length constraints, which frequently force the truncation of long tables, discarding crucial rows or metadata and reducing reasoning capacity. Recent empirical studies confirm this: LLMs on Tabular Data reports that LLMs suffer a large drop in accuracy when table orientation is perturbed (e.g. transpose, shuffle) because they lack structural robustness. Likewise, Benchmarking Systematic Relational Reasoning with Large Language and Reasoning Models shows that LLMs perform poorly on out-of-distribution relational composition tasks even when scaffolded with prompting or fine-tuning (Khalid, Nourollah & Schockaert, 2025).

Our contributions are as follows:

We present CoAgt, a novel framework composed of coordinated agents designed to generate answers from interdependent rows and columns in structured data.

We eliminate the need to learn or generate SQL to extract answers from tables.

Our model outperforms leading baselines that use multiple response sampling and self-consistency on two benchmark datasets: WikiTQ and TabFact.

This article is organised as follows. ‘Related Work’ reviews related work on LLMs for structured data and multi-agent frameworks. ‘Materials and Methods’ describes the CoAgt methodology, including agent roles and coordination mechanisms. ‘Experimental Setup’ outlines the experimental setup, including datasets, baselines, and evaluation metrics. ‘Results and Discussion’ presents results and analysis. ‘Conclusion’ concludes and discusses future directions.

Related work

LLMs for structured data

Early work on table-based question answering focused on training specialised models capable of processing both tabular data and natural language. Yin et al. (2020), TAPAS (Herzig et al., 2020), and TURL (Deng et al., 2020) represent foundational efforts in this area. These models incorporate structured inputs through mechanisms such as table-aware embeddings, masked column modelling, and pretraining on table-text corpora. Although they achieved notable gains on benchmark datasets such as WikiTQ and TabFact, their effectiveness is constrained by input length limitations, and their performance declines when applied to large or noisy tables.

More recent approaches leverage general-purpose LLMs to perform table question answering through prompt engineering, chain-of-thought reasoning, or tool invocation. For example, TABLELLM (Zhang et al., 2025) and StructGPT (Jiang et al., 2023) explore hybrid pipelines that combine LLMs with external tools such as Python or SQL to execute complex spreadsheet operations. Similarly, Rethinking TableQA (Sun, Yang & Liu, 2020) compares textual and symbolic reasoning approaches and demonstrates that integrating both yields improved results. However, these methods are primarily designed for short tables, limiting their robustness and accuracy when applied to longer or more variable tabular content.

TabSQLify (Nahid & Rafiei, 2024) introduces a solution to this challenge by transforming a natural language question into an SQL query that retrieves a reduced sub-table. The model then performs reasoning on the relevant subset of rows and columns, reducing the likelihood of input overflow. NormTab (Nahid & Rafiei, 2024) complements this by preprocessing tables for structural consistency, thereby enhancing the accuracy of symbolic reasoning. Nevertheless, these frameworks are unable to process genuinely long tables, lack support for Arabic, and have not been evaluated under multilingual or low-resource conditions.

PieTa (Wang et al., 2023) adopts a divide-and-conquer approach, identifying the most relevant subtable to answer a given question without the need for SQL. While effective in reducing table complexity, this approach may overlook dispersed evidence spread across multiple subtables.

Integrating agents with LLMs for structured data

The integration of multi-agent systems with LLMs has emerged as a promising approach for analysing structured data. Several studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of agent-based architectures in addressing the limitations of traditional models.

One of the pioneering works in this area is MAC-SQL (Xiao et al., 2024), which presents a multi-agent system optimised for SQL-based query processing over large-scale databases. MAC-SQL employs a hierarchical agent structure: the Planner Agent interprets the user’s natural language query and decomposes it into structured SQL tasks; the Retriever Agent navigates the database to extract relevant data segments; the Executor Agent applies necessary filters and aggregations; the Evaluator Agent checks the results for logical consistency; and the Response Generator Agent formats the final output.

In the biomedical domain, CellAgent (Mathur et al., 2024) was developed to support cell-specific data manipulation in large structured tables. This framework uses a team of specialised agents for granular-level data extraction, validation, and aggregation. Each agent is designated to handle a specific aspect of the data, which improves both processing speed and accuracy. The Response Generator Agent synthesises the extracted insights into coherent, domain-specific summaries, improving interpretability for biomedical researchers.

The MATSA framework (Cen et al., 2025) tackles the challenge of analysing long, structured tables that contain hundreds or even thousands of rows. It assigns dedicated agents to manage tasks such as table segmentation, attribute validation, and answer synthesis. This decomposition strategy allows the system to handle large datasets efficiently without overwhelming memory or processing resources. MATSA has shown improvements in both query accuracy and processing time when applied to financial datasets with high-dimensional attributes.

More recently, SQLFixAgent (Baddeley, 2012) was introduced to improve the semantic accuracy of SQL queries generated by LLMs through multi-agent collaboration. In this framework, specific agents are tasked with detecting and correcting logical inconsistencies in SQL statements prior to execution. This error-correction mechanism enhances the reliability and robustness of querying structured databases.

Despite the advances offered by these multi-agent LLM-based systems, several challenges remain unresolved. A major limitation is the continued reliance on translating natural language questions into SQL, which requires accurate semantic parsing. Moreover, traditional NLP models, while effective for unstructured text, are not optimised to handle the relational and multi-dimensional complexity of tabular data. Current LLMs, although powerful in text understanding, struggle with schema alignment and relational reasoning, often producing incomplete or incorrect answers to complex queries. Many existing methods process tables linearly, either row-wise or column-wise, without capturing the interdependencies that exist across the entire table. This sequential processing hampers their ability to perform contextual and multi-step reasoning.

To overcome these challenges, recent work has proposed the integration of multi-agent systems with LLMs for more effective table reasoning. In the proposed CoAgt framework, specialised agents such as Collector Agents and a Synthesis Agent collaborate to decompose complex queries, retrieve relevant table segments, perform computations, and articulate final answers. This agent-based design improves both interpretability and computational efficiency, enabling the system to process large-scale tabular data with greater accuracy and consistency.

Materials and Methods

Our approach aims to extract answers directly from large tables using only natural language questions, without the need to generate SQL queries. It leverages the strengths of Large LLMs in understanding textual input while addressing their limitations in processing lengthy tables that exceed token limits. Rather than expanding the input size, we introduce a chain-of-agents framework: Collector Agents segment the table into manageable chunks and extract relevant information; a Synthesiser Agent integrates information across these segments and supervises the answer-generation process; and an Answer Refiner ensures that the final response is both coherent and accurate. This agent-based coordination enables efficient table reasoning without the need for explicit query formulation.

CoAgt is designed to emulate the human reasoning process through a coordinated group of LLM-based agents. It systematically maps each cognitive step onto specialised agents, facilitating interpretable and scalable table question answering. The initial stages, visual scanning and column interpretation, are managed by LLMs that simulate human perception by identifying relevant columns and interpreting their meanings in relation to the question. Incremental comparison, which the human brain typically performs row by row, is delegated to the Collector Agents. Each Collector processes a specific sub-table, conducts localised analysis, and generates intermediate outputs. These agents serve as the framework’s working memory, retaining and forwarding key insights for downstream processing. Final decision-making and validation are performed by the Synthesiser Agent, which aggregates the partial outputs, performs global comparisons, and generates the final answer. This final step mirrors the human cognitive process of synthesising information and verifying conclusions to ensure accuracy.

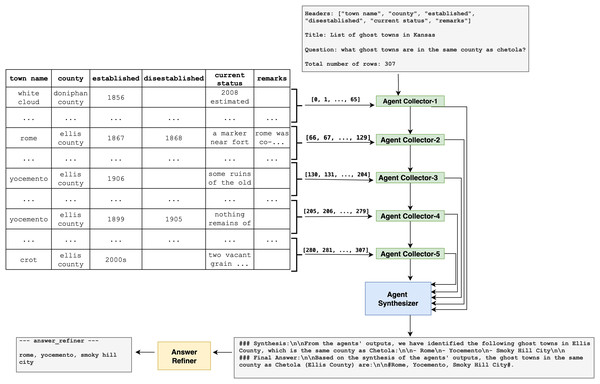

Figure 1 illustrates the two-agent architecture developed to enable effective question answering over long tabular data using LLMs, for example, GPT-4o (ChatGPT), which is used in our study. The framework is specifically designed to overcome the input length constraints inherent in transformer-based models, which struggle to process complete tables that exceed their token capacities. Although Fig. 1 presents an example involving 307 rows from a dataset of ghost towns in Kansas, the architecture is scalable and can handle arbitrarily long tables. This is achieved by dynamically controlling the number of tokens allocated to each processing unit, rather than relying on static row segmentation.

Figure 1: Overview of the proposed CoAgt architecture.

Table preprocessing

Although traditional approaches typically rely on SQL to query structured relational tables, many real-world tables, particularly those sourced from the web, lack the consistency and formatting required for reliable SQL execution. Instead of depending on SQL, our method uses a two-agent framework along with an Answer Refiner to extract responses directly from tabular data. We hypothesise that applying lightweight table cleaning and retrieving relevant rows and columns, even when exact matches are unavailable, improves the robustness of the reasoning process. The final answer is produced during the Answer Refiner phase, in which the LLM-based refiner resolves formatting inconsistencies and disambiguates conflicting or unclear entries.

As part of preprocessing, we normalised numerical and date values to ensure consistency across agents. For example, figures such as ‘7,500.00’ were standardised to ‘7,500.00’, and date formats including ‘05 March 2021’, ‘Mar 5, 2021’, and ‘2021/03/05’ were all converted to ‘2021-03-05’. This cleaning step allows agents to focus on semantic alignment and reasoning, rather than being hindered by formatting variation.

Agent collector

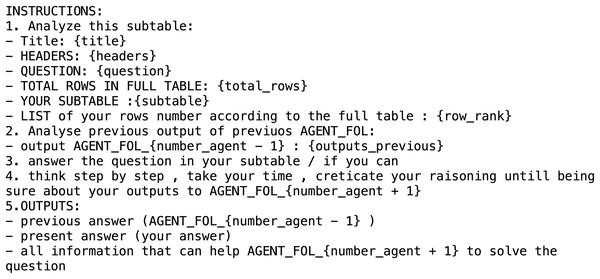

The first step involves segmenting the table into multiple parts using an LLM. Each segment is then assigned to an individual Agent Collector. Each Collector receives a portion of the table, the original question, and relevant metadata, including the table title, column headers, and total number of rows. The Collector searches within its assigned segment for information that may assist in answering the question. Even if a Collector does not find a direct match, it still forwards its processed results. This mechanism ensures complete table coverage and preserves potentially useful contextual information for downstream reasoning. For example, one agent might identify that a town in its segment belongs to the same county as Chetola, while another might extract structural patterns or partial evidence from seemingly unrelated rows. The format of the prompt used by each Agent Collector is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Prompt used for the agent collector in the WikiTabQA and TabFact datasets.

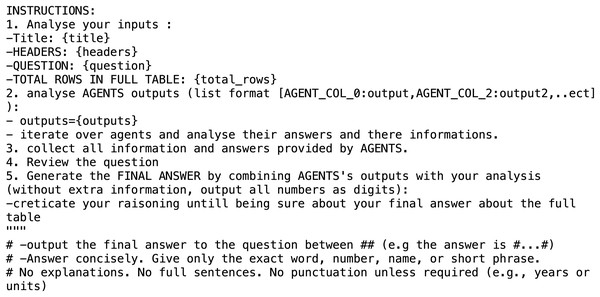

Agent synthesizer

The Agent Synthesiser is responsible for aggregating the outputs produced by all Agent Collectors. It performs global reasoning by integrating both partial and complete findings to form a unified interpretation of the data. Even when relevant information is dispersed across different table segments, the Synthesiser is capable of inferring the correct answer. For instance, in the example provided, the Synthesiser identifies Rome, Yocemento, and Smoky Hill City as towns located in Ellis County by combining distributed evidence from multiple segments. This demonstrates its ability to draw accurate conclusions based on fragmented but complementary data. The format of the prompt used for the Agent Synthesiser is illustrated in Figs. 3 and 4.

Figure 3: Prompt used for the agent synthesizer in the WikiTabQA dataset.

Figure 4: Prompt used for the agent synthesizer in the TabFact dataset.

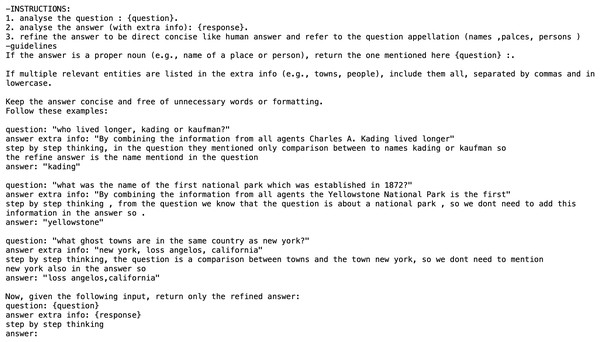

Answer refiner

The final stage of the framework is the Answer Refiner, which ensures that the output is accurate, consistent, and well-formatted. It cleans the synthesised response, removes redundancy, checks letter casing to match that used in the table, and presents the answer in a clear and readable form. For example, the final answer in the current case is: rome, yocemento, smoky hill city. This stage demonstrates the system’s ability to extract correct information from a long, unstructured input without relying on SQL translation. The format of the prompt used for the Answer Refiner is shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: Prompt used for the answer refiner in the WikiTabQA dataset.

To further ground the design of CoAgt, we explicitly align the roles of its agents with established cognitive theories. The Collector Agents function as distributed working memory units, each processing a segment of the table and retaining partial results before passing them forward. This mechanism parallels the working memory model, where limited-capacity subsystems temporarily store and manipulate information during reasoning tasks (Gronchi et al., 2024). In addition, the Collectors perform rapid pattern identification, akin to the intuitive and automatic operations of System 1 in dual-process theory (Bhat et al., 2025). By contrast, the Synthesizer Agent embodies System 2 reasoning, integrating outputs across Collectors, executing deliberate comparisons, and validating final decisions in a controlled, analytical manner. Finally, the Answer Refiner can be seen as a form of metacognitive monitoring, reflecting the human tendency to review and adjust conclusions for coherence and accuracy (Fang et al., 2024). Together, these mappings reinforce that CoAgt is not only computationally effective but also cognitively inspired, faithfully replicating human strategies for scanning, comparing, and synthesizing information from complex tabular inputs.

Scalability and token management

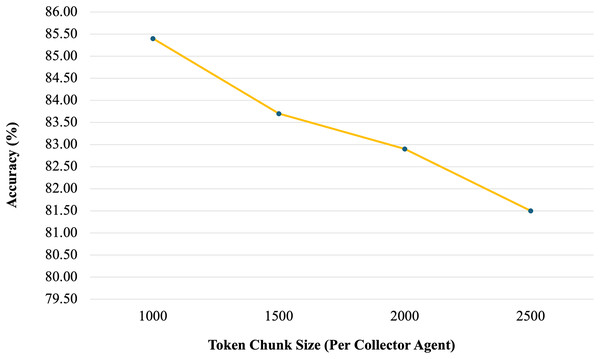

A key strength of the proposed architecture is its scalability. The system is capable of processing tables of arbitrary length by adjusting the number of Collector Agents and carefully managing the token budget allocated to each segment. In our experiments, we evaluated various token limits—1,000, 1,500, 2,000, and 2,500 tokens per agent. The most stable and accurate performance was observed when each agent’s input was limited to approximately 1,000 tokens. This configuration allowed the system to retain essential context while avoiding token overflow, thereby supporting more reliable reasoning. This token-based segmentation strategy enables the model to generalise effectively to long tables without compromising performance. In Fig. 1, each chunk contains 2,500 tokens instead of the 1,000-token configuration used in evaluation. This was done to reduce the number of required agents for illustrative purposes. Using 1,000-token chunks would have required 12 agents, which would not have provided a clear or effective visual representation. The larger chunk size was therefore chosen to simplify the example and improve readability.

To further validate our design choice, we conducted a sensitivity analysis evaluating the effect of token chunk size per Collector Agent on accuracy as shown in Fig. 6. We tested chunk sizes of 1,000, 1,500, 2,000, and 2,500 tokens on a representative sample from the WikiTQ dataset. Results showed that accuracy peaks at 1,000 tokens (85.4%), with slightly lower values at 1,500 (83.7%) and 2,000 (82.9%), and a further decline at 2,500 tokens (81.5%). This trend suggests that smaller, focused segments allow each Collector to reason more effectively, while larger segments dilute relevance and increase inconsistency.

Figure 6: Sensitivity analysis (token Chunk size vs. accuracy).

These findings align with recent studies on retrieval and chunking for long documents. In Nguyen, Nguyen & Nguyen demonstrated that mid-sized chunks (≈512–1,024 tokens) achieve stronger performance than very small or very large chunks when retrieving information from long texts. Similarly, Yu et al. (2021) showed that hierarchical segmentation strategies with moderate chunk sizes enhance retrieval-augmented generation by preserving contextual coherence while avoiding overload. Taken together, both prior evidence and our experiments support the choice of 1,000 tokens per agent as an effective and well-justified configuration.

Experimental setup

Dataset

We evaluate our proposed method on two established benchmark datasets focused on table reasoning, under strict constraints that prohibit fine-tuning and rely solely on zero-shot performance using LLMs.

WikiTQ is a benchmark dataset consisting of complex natural language questions generated by crowd workers based on Wikipedia tables. These questions require advanced reasoning capabilities, including comparison, aggregation, and arithmetic across multiple table entries. The standard test set comprises 4,344 samples (Pasupat & Liang, 2015).

We used the WikiTQ dataset, which is originally introduced by Pasupat & Liang (2015). The dataset is publicly available at https://github.com/ppasupat/WikiTableQuestions.

Moreover, we used the TabFact dataset. It is a fact verification dataset in which each instance includes a natural language statement paired with a corresponding table from Wikipedia. The task is to determine whether the statement is True or False based solely on the content of the table. Model performance is measured on the test-small split, which includes 2,024 statements and 298 tables (Chen et al., 2019). The dataset is publicly available at https://github.com/wenhuchen/Table-Fact-Checking.

Baselines

We evaluate our method by comparing it with a diverse set of baseline models that follow either a pre-training and fine-tuning paradigm or employ in-context learning using LLMs. The first category includes models that are pre-trained on large tabular datasets and subsequently fine-tuned for specific tasks. These models typically encode the input table as a flattened sequence using an encoder, followed by answer generation through a decoder. As representatives of this class, we include TaPas (Herzig et al., 2020), GraPPa (Ni et al., 2023), and LEVER (Nahid & Rafiei, 2024), NormTab (Chen, 2022). These models are evaluated to assess performance under supervised table understanding strategies.

The second category consists of in-context learning approaches that use pretrained LLMs to process tabular data without additional fine-tuning. Instead, these methods rely on prompt engineering and few-shot examples to guide reasoning. We compare our method against a range of models in this category, including TableCoT (Cheng et al., 2023), BINDER-Codex (Ye et al., 2023), DATER-Codex (Zhang et al., 2024), ReAcTable-Codex (Wang et al., 2024), Chain-of-Table (Hussain, 2024), StructGPT (Jiang et al., 2023), ARTEMIS-DA (Patnaik et al., 2024), CABINET (Wang, Qi & Gan, 2025), TabLaP (Zhong et al., 2020), SynTQA-GPT, NormTab (Nahid & Rafiei, 2024), TabSQLify (Nahid & Rafiei, 2024), Table-BERT (Chen et al., 2019), LogicFactChecker and SAT (Liu et al., 2022), and TAPEX (Liu et al., 2022).

Implementation

In our experiments, we use GPT-4o as the underlying language model. Prompts are designed to guide both the agents and the Answer Refiner, as each component operates based on instructions processed by the LLM. For all agents, the input is segmented into chunks of approximately 1,000 tokens. We use a temperature setting of 0.2 for the Agent Collector and 0.5 for the Agent Synthesiser, balancing consistency and diversity in generation across stages.

We set the temperature to 0.2 for Collector Agents and 0.5 for the Synthesizer Agent. The rationale is that Collectors benefit from deterministic outputs when identifying relevant rows and columns, while the Synthesizer requires moderate flexibility to aggregate evidence across Collectors. To assess robustness, we varied the temperature between 0.2 and 0.8. Results indicate that accuracy fluctuates by less than ±1.2% on both WikiTQ and TabFact across this range. This confirms that CoAgt’s performance does not depend heavily on exact temperature values, and our reported results reflect a stable configuration rather than an artifact of hyperparameter selection.

The codebase, sample outputs, and full prompt templates are publicly available at: https://github.com/Asmaa-Alrayzah/CoAgt.

Evaluation metrics

For the WikiTQ dataset, evaluation is based on Exact Match (EM) accuracy, which determines whether the predicted answers match the ground truth exactly. To mitigate discrepancies due to formatting differences in numerical and date values, we apply a normalisation step prior to comparison, consistent with the preprocessing pipeline described in ‘Table Preprocessing’. For the TabFact dataset, model performance is assessed using binary classification accuracy, which reflects the proportion of correctly predicted True or False labels for natural language statements relative to their associated tables.

Results and Discussion

Comparison with baseline models

We evaluate the performance of our proposed model, CoAgt, on two benchmark datasets: WikiTQ and TabFact. Across both datasets, CoAgt consistently outperforms existing models, including fine-tuned encoder–decoder baselines and LLM-based in-context learners.

Table 1 reports accuracy on the WikiTQ dataset using the official evaluation metric. Traditional models such as TaPas (48.8%), GraPPa (52.7%), and LEVER (62.9%) show limited capacity for complex reasoning over long tables. More recent agent-based and chain-of-thought (CoT) enhanced methods, including TableCoT-Codex (48.8%), DATER-Codex (65.9%), and ReAcTable-Codex (65.8%), demonstrate improved accuracy but still fall short of capturing human-like reasoning patterns effectively. Among ChatGPT variants, Chain-of-Table achieves the highest performance (59.9%), while most other methods remain in the low 50% range. By contrast, CoAgt achieves 85.4%, substantially surpassing all baselines and confirming the effectiveness of its structured agent-based design. CoAgt outperforms recent state-of-the-art systems such as SynTQA-GPT (74.4%), TabLaP (76.6%), and ARTEMIS-DA (80.8%).

| Models | Accuracy |

|---|---|

| TaPas | 48.8 |

| GraPPa | 52.7 |

| LEVER | 62.9 |

| TableCoT-Codex | 48.8 |

| DATER-Codex | 65.9 |

| BINDER-Codex | 61.9 |

| ReAcTable-Codex | 65.8 |

| BINDER-chatgpt | 55.4 |

| DATER-chatgpt | 52.8 |

| ReAcTable-chatgpt | 52.5 |

| TableCoT-chatgpt | 52.4 |

| StructGPT | 52.2 |

| Chain-of-table | 59.9 |

| TabSQLify | 64.7 |

| NormTab | 61.20 |

| CABINET | 69.1 |

| SynTQA-GPT | 74.4 |

| PieTa | 74.1 |

| TabLaP | 76.6 |

| ARTEMIS-DA | 80.8 |

| Our model (CoAgt) | 85.4 |

In Table 1, while models such as Chain-of-Table (59.9%) and StructGPT (52.2%) represent recent baselines that integrate chain-of-thought reasoning and structured prompts, their performance declines significantly on long or relationally complex tables. These methods process tables linearly, which often causes the loss of relational dependencies across rows and columns. For example, Chain-of-Table evolves reasoning over row sequences but does not explicitly preserve global schema alignment or manage memory for large contexts. Similarly, StructGPT, while schema-aware, still inherits the token-limit bottleneck of standard LLMs, leading to truncation or omission of critical information.

Table 2 presents the results on the TabFact dataset. Here again, CoAgt leads with an accuracy of 96.5%, outperforming all prior approaches. Compared with traditional models such as Table-BERT (68.1%) and LogicFactChecker (74.3%), as well as strong pretrained models such as TAPEX (85.9%) and PASTA (89.3%), CoAgt demonstrates superior factual reasoning over complex tabular data. Even against the most advanced recent methods, including DATER (93.0%) and ARTEMIS-DA (93.1%), CoAgt maintains a clear margin. It also exceeds reported human performance (92.1%), indicating strong generalisation and decision-making capabilities within the TabFact task. These results validate the central design principles of CoAgt, demonstrating that modelling human cognitive processes through modular LLM-based agents yields both scalable and interpretable improvements in tabular question answering.

| Model | Accuracy |

|---|---|

| Table-BERT | 68.1 |

| LogicFactChecker | 74.3 |

| SAT | 75.5 |

| TaPas | 83.9 |

| TAPEX | 85.9 |

| PASTA | 89.3 |

| Human | 92.1 |

| TableCoT-Codex | 72.6 |

| DATER-Codex | 85.6 |

| BINDER-Codex | 85.1 |

| ReAcTable-Codex | 83.1 |

| ReAcTable-chatgpt | 73.1 |

| TableCoT-chatgpt | 73.1 |

| BINDER-chatgpt | 79.1 |

| DATER-chatgpt | 78.0 |

| Chain-of-Table | 80.2 |

| NormTab | 68.90 |

| TabSQLify | 79.5 |

| BINDER | 86.0 |

| DATER | 93.0 |

| ARTEMIS-DA | 93.1 |

| Our model (CoAgt) | 96.5 |

By contrast, CoAgt introduces three key mechanisms that account for its higher performance. First, the decomposition strategy with Collector Agents ensures complete table coverage without truncation. Each Collector acts as a localized working memory, capturing row–column dependencies that might otherwise be lost during linear processing. Second, the Synthesizer Agent integrates distributed findings across Collectors, reconstructing holistic reasoning paths even when supporting evidence is dispersed across distant parts of the table. Third, the Answer Refiner provides an additional verification layer that corrects misalignments, enforces consistent formatting, and eliminates redundant or spurious outputs. This stage reduces the noise that often undermines the reliability of baseline models relying solely on raw LLM outputs.

These mechanisms not only yield for instance an improvement of +25.5% over Chain-of-Table on WikiTQ, but also result in statistically significant improvements (p < 0.01) across both WikiTQ and TabFact. More importantly, the design of CoAgt tailored to long tables. While baselines suffer performance degradation as table size increases, CoAgt maintains robustness by dynamically adjusting the number of Collector Agents to fit the token budget. This explains why CoAgt sustains high accuracy (71% at ≥9,000 tokens) compared to TabSQLify (57%) and other methods as shows in Table 3.

| Number of tokens | Number of samples | CoAgt (agent approach) | TabSQLify |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≥9,000 | 7 | 0.71 | 0.57 |

| ≥7,000 | 39 | 0.71 | 0.58 |

| ≥1,000 | 81 | 0.80 | 0.57 |

| Full dataset | 4,344 | 0.85 | 0.67 |

Moreover, to evaluate the scalability of our model, we further grouped WikiTQ samples by table size in tokens and compared performance against TabSQLify. As shown in Table 3, CoAgt consistently outperforms TabSQLify across all ranges. Even on extremely long tables (≥9,000 tokens), CoAgt maintains a high accuracy of 71%, while TabSQLify drops to 57%. It conclude that the performance gap widens as table length increases, confirming CoAgt’s robustness under token-intensive scenarios.

On the other hand, we assessed the scalability and robustness of our model by imposing a token limit on each table for WikiTQ and evaluating performance across increasingly large subsets. As shown in Table 4, our model, CoAgt, significantly outperforms all baselines on large tables (>4,000 tokens) in the WikiTQ dataset, achieving an accuracy of 80.0%. Unlike models constrained by token limits or reliant on upper-table answers, CoAgt successfully segments and processes entire tables using a chain of agents. This allows accurate reasoning regardless of the answer’s position. The result demonstrates strong scalability and robustness in handling long tabular data, a known bottleneck in previous methods.

| Model | Acc (Large) |

|---|---|

| BINDER-Codex | 29.6 |

| BINDER-chatgpt | 0.0 |

| DATER-chatgpt | 34.6 |

| Table-CoT-chatgpt | 35.1 |

| Chain-of-Table | 44.8 |

| TabSQLify | 52.3 |

| CoAgt (ours) | 80.0 |

The results in Tables 1–4 reveal three main findings. First, CoAgt outperforms other baselines such as Chain-of-Table and StructGPT across both WikiTQ and TabFact, with gains of more than 25% on WikiTQ and more than 3% points on TabFact. Second, the performance gap widens as table size increases. For long tables exceeding 9,000 tokens, CoAgt sustains an accuracy of 71% percent, compared to 57% percent for TabSQLify, showing that its segmentation-and-synthesis strategy scales more gracefully than linearized baselines. Third, CoAgt maintains stable performance across different table domains and task types, showing that the multi-agent design generalizes beyond a single dataset.

On the other hand, although LLMs may contain biases from pretraining data, CoAgt’s design inherently constrains such effects. The framework operates exclusively over the provided table, and each agent’s role enforces grounding in structured evidence: Collectors extract information from assigned sub-tables, the Synthesizer performs cross-segment reasoning without relying on external context, and the Refiner produces direct, table-based outputs. This decomposition reduces the chance that socially or demographically biased associations spill into tabular reasoning. Thus, while CoAgt depends on the underlying LLM, its agent-based architecture provides a form of bias containment by anchoring outputs to the explicit content of the table.

Moreover, we compared the efficiency of CoAgt with representative baselines. On WikiTQ, CoAgt achieves an average latency of about 8 s per query, compared to about 5 s for Chain-of-Table and about 6 s for StructGPT. On TabFact, average latency increases from about 5 s to about 7 s. In terms of token usage, CoAgt averages around two thousand nine hundred tokens per query, similar to Chain-of-Table (around two thousand seven hundred) and StructGPT (around two thousand eight hundred), since segmentation reduces overflow and prevents excessive re-generation. Thus, the main overhead of CoAgt lies in latency due to multiple agent calls rather than ballooning token consumption. These overheads are moderate when compared to the large accuracy improvements (e.g., plus twenty-five percentage points on WikiTQ, plus three percentage points on TabFact), suggesting that the performance gains justify the additional compute costs. For real-world applications, the number of Collector Agents can be dynamically adjusted to balance accuracy and efficiency depending on resource constraints.

Prompt ablation

We evaluate the impact of individual prompt components on performance by disabling them in CoAgt as shown in Table 5. Removing the instruction “think step by step, take your time, creticate your raisoning untill being sure about your outputs” (Collector, Fig. 2) and “think step by step, take your time, creticate your raisoning untill being sure about your final answer about the full table” (Synthesizer, Figs. 3–4) yields the largest single-component drop, with accuracy falling from 85.4 to 82.2 on WikiTQ and from 96.5 to 94.9 on TabFact (p < 0.01). Excluding the directive in the Collector prompts to “LIST of your rows number according to the full table : {row_rank}” reduces accuracy from 85.4 to 83.3 on WikiTQ and from 96.5 to 95.1 on TabFact. Omitting the Synthesizer requirement to “–Title: {title}—HEADERS: {headers}—QUESTION: {question}—TOTAL ROWS IN FULL TABLE: {Total_rows}” before generating the answer produces a smaller decline, from 85.4 to 84.0 on WikiTQ and from 96.5 to 95.8 on TabFact. Removing the Answer Refiner directive to “return only the refined answer” slightly decreases performance to 84.5 on WikiTQ and 96.0 on TabFact. Finally, the bare prompt setting, in which all four instructions are removed, performs worst, dropping to 79.6 on WikiTQ and 92.8 on TabFact. These results represents that the “think step by step” instruction is the most critical contributor to performance gains, while the other explicit instructions further stabilize outcomes.

| Removed Prompt | WikiTQ | TabFact |

|---|---|---|

| “Think step by step, take your time, creticate your reasoning untill being sure about your outputs” (Collector) “think step by step, take your time, creticate your raisoning untill being sure about your final answer about the full table” (Synthesizer) |

82.2 | 94.9 |

| “LIST of your rows numbers according to the full table: {row_rank}” | 83.3 | 95.1 |

| “Title: {title}—HEADERS: {headers} – QUESTION: {question}—TOTAL ROWS IN FULL TABLE: {total_rows}” | 84.0 | 95.8 |

| “Return only the refined answer” | 84.5 | 96.0 |

| Bare setting (all four instructions removed) | 79.6 | 92.8 |

| Full CoAgt (all instructions active) | 85.4 | 96.5 |

Agent component ablation and failure case analysis

To evaluate the contribution of each agent, we progressively disabled them and measured performance. Without Collectors, accuracy on WikiTQ dropped from 85.4% to 77.9%, confirming their role in covering long tables and preventing truncation. Without the Synthesizer, results declined to 80.6%, as distributed evidence across Collectors could not be integrated effectively. Without the Answer Refiner, performance dropped to 82.4%, with outputs becoming verbose and inconsistently formatted. These results confirm that all three components contribute to final performance, with Collectors being most critical.

Despite high results, CoAgt still struggles with certain scenarios. For example, when multiple headers share overlapping semantics (e.g., “Score” vs. “Points”), the Collectors sometimes retrieve the wrong column, leading the Synthesizer to propagate the error. Similarly, in multi-step reasoning tasks where aggregation requires precise numerical operations across many rows, the Synthesizer may generate incomplete or partially correct logic chains. These cases highlight areas for future refinement, such as integrating schema disambiguation techniques and specialized numerical reasoning modules.

Efficiency vs. accuracy trade-off

As shown in Table 6, CoAgt introduces a moderate increase in inference time because each query is processed by multiple agents. On WikiTQ, the average latency is about 8 s per query, compared to about 5 s for Chain-of-Table and 6 s for StructGPT. On TabFact, CoAgt’s latency is about 7 s, vs. about 5 s for baselines. In terms of token usage, all models are similar: around 2,700 tokens for Chain-of-Table, 2,800 for StructGPT, and 2,900 for CoAgt. This means the main cost of CoAgt is latency, not token inflation.

| Model | WikiTQ latency (s) | TabFact latency (s) | Avg. Tokens per query | Accuracy (WikiTQ/TabFact) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chain-of-table | ~5 | ~5 | ~2.7 K | 59.9%/80.2% |

| StructGPT | ~6 | ~5 | ~2.8 K | 52.2%/– |

| CoAgt (ours) | ~8 | ~7 | ~2.9 K | 85.4%/96.5% |

However, this cost comes with a benefit. CoAgt achieves 85.4% accuracy on WikiTQ and 96.5% on TabFact, compared to 59.9% and 80.2% for Chain-of-Table. The extra few seconds of processing are therefore more than offset by the significant accuracy improvements, over twenty-five points, on WikiTQ and more than three points on TabFact. For practitioners, this trade-off suggests that CoAgt is particularly attractive in high-stakes scenarios where reliable results are more important than minimal response times. Moreover, the number of Collector Agents can be tuned to balance speed and accuracy depending on the deployment context.

Moreover, although multi-agent systems like CoAgt introduce some computational overhead compared to single-agent approaches, our analysis shows that the trade-off is favorable. CoAgt increases inference time by only 2 to 3 s on average but achieves substantially higher accuracy, confirming that the gains outweigh the costs. Beyond raw numbers, CoAgt offers structural advantages: by decomposing reasoning into specialized roles, it avoids the error compounding often observed in single-agent models, which must handle extraction, synthesis, and verification simultaneously. This modularity enables more stable long-table reasoning, better handling of dispersed evidence, and easier interpretability. Compared with approaches that rely on a single LLM prompt for efficiency such as Potable (Wang et al., 2023), CoAgt demonstrates that distributing tasks across agents leads to more robust performance without incurring prohibitive computational consumption.

Conclusion

This article has presented CoAgt, a cognitively inspired, agent-based framework for answering questions over long tabular data using LLMs, without the need for SQL generation. Drawing inspiration from the way the human brain processes tables, through scanning, comparison, memory, and decision-making, CoAgt replicates this reasoning using a structured chain of agents. Collector Agents operate on segmented sub-tables, a Synthesiser Agent aggregates their outputs, and a final Answer Refiner ensures clarity and correctness in the generated answer.

CoAgt achieves state-of-the-art performance on two benchmark datasets, WikiTQ and TabFact, with accuracies of 85.4% and 96.5%, respectively. These results demonstrate its effectiveness in reasoning over long tables that exceed standard LLM input limitations, while also offering scalability, interpretability, and robustness. By avoiding SQL entirely and relying solely on natural language, CoAgt enables zero-shot reasoning over large, unstructured tabular inputs.

Future work will focus on extending CoAgt to support multilingual and low-resource settings, particularly in Arabic tabular question answering. Additional directions include integrating vision–language models to handle semi-structured formats such as PDFs and developing new benchmarks to evaluate agent-based reasoning on large, real-world datasets.

Future work will also focus on extending CoAgt to handle noisy and irregular real-world tables, such as those commonly found in Excel spreadsheets and web-scraped HTML data. These sources often contain missing or multi-row headers, merged cells, inconsistent formatting, or sparsely populated rows, which present challenges beyond clean Wikipedia-style tables. While CoAgt already incorporates a lightweight preprocessing stage for normalization, further research is needed to enhance its robustness through automatic schema inference, header recovery, and integration with table-repair techniques. In addition, systematically evaluating CoAgt on noisy benchmarks or by injecting artificial noise into existing datasets will provide deeper insights into its resilience under real-world conditions.

Future work will also explore extending CoAgt beyond question answering and fact verification to other table-centric tasks. For instance, in table summarization, Collector Agents could extract salient rows and attributes, while the Synthesizer Agent integrates them into concise summaries and the Refiner ensures readability. In data imputation, Collectors could identify missing or inconsistent values within sub-tables, and the Synthesizer could infer likely completions by aggregating contextual evidence across segments. Similar adaptations could also support tasks such as entity matching, anomaly detection, or metadata enrichment in structured datasets. These directions highlight CoAgt’s flexibility as a general-purpose multi-agent framework for reasoning over large or noisy tabular data.