Prioritizing benefits, costs, and contextual and individual factors in researchers’ adoption of generative artificial intelligence: a multi-criteria decision-making analysis

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Alexander Bolshoy

- Subject Areas

- Human-Computer Interaction, Artificial Intelligence, Data Science, Emerging Technologies, Social Computing

- Keywords

- GAI, Academic research, Thematic analysis, Researchers, Adoption, Topsis, Vikor

- Copyright

- © 2026 Salman et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2026. Prioritizing benefits, costs, and contextual and individual factors in researchers’ adoption of generative artificial intelligence: a multi-criteria decision-making analysis. PeerJ Computer Science 12:e3417 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3417

Abstract

Background

Generative artificial intelligence (GAI) tools are transforming how researchers access information, write academic papers, and collaborate. However, many scholars remain cautious, questioning whether the potential productivity gains outweigh concerns about increased effort, possible inaccuracies, and ethical implications. This study investigates the factors influencing researchers’ adoption of GAI and aims to offer actionable guidance for institutions seeking to promote its responsible and effective use.

Methods

We first conducted a literature review and used thematic analysis to identify 18 key factors affecting GAI adoption. Next, 81 researchers rated the importance of each factor on a five-point scale. We analyzed these ratings using both the Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) and the Multi-Criteria Optimization and Compromise Solution (VIKOR) methods in a multi-attribute group decision-making (MAGDM) setting.

Results

The analysis produced largely consistent results: Ethical concerns and performance risk were the most significant cost-related factors, while Task efficiency and knowledge acquisition were the top benefit-related drivers. Among personal and contextual variables, facilitating conditions and AI literacy emerged as the most influential.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that institutions should establish clear guidelines to address ethical and accuracy-related concerns surrounding GAI use. The identified factors also offer a foundation for future research and can inform the refinement of existing adoption frameworks.

Introduction

The rise of generative AI (GAI) tools leveraging large language models to produce text, code, and visualizations is transforming multiple domains (Hagos, Battle & Rawat, 2024). This technology is expected to reshape the main phases of academic research: discovery and exploration, data analysis, and writing/reporting. By automating routine tasks such as literature synthesis and reviews, language editing, and data visualization, allowing researchers to focus more on conceptual innovation (Dwivedi et al., 2023).

Despite the acknowledged potential of generative artificial intelligence (GAI) to enhance research productivity, its integration into scholarly work faces resistance. Experimental evidence shows that lay participants judge researchers who delegate research tasks to GAI tools as less trustworthy, less morally acceptable, and less likely to produce accurate results (Niszczota & Conway, 2023). Similarly, several studies reported a gap between GAI’s potential and its practical adoption by researchers. For example, Ruediger, McCracken & Skinner (2024) observed that although 60% of biomedical researchers experimented with GAI, frequent use was rare, and domain-specific adoption remained minimal (14%) due to concerns over accuracy and ethical risks. Consistent with these findings, several other studies collectively highlight persistent barriers such as ethical apprehensions, perceived threats to research quality, inadequate skills, and fear of compromised intellectual autonomy. Such resistance underscores critical institutional challenges to effective and ethically sound GAI integration in research and scholarly practices (Abdelhafiz et al., 2024; Iyengar & Upadhyay, 2024; Salman et al., 2024).

Given the growing interest in GAI within higher education institutions (HEIs), it is essential to thoroughly evaluate the potential risks and benefits associated with adopting these technologies by academic researchers. Employing multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) techniques provides a structured framework for systematically comparing various adoption scenarios by considering diverse criteria and researchers’ perspectives.

Current research examining the adoption of GAI by faculty for academic research within HEIs is limited. Most studies concentrated on classroom policies because HEIs were under immediate pressure to safeguard academic integrity. Consequently, the literature remains largely confined to teaching and learning (An, Yu & James, 2025; Ruediger, McCracken & Skinner, 2024; Sekli, Godo & Véliz, 2024). Garcia (2025), Sekli, Godo & Véliz (2024) explicitly identified the absence of work on GAI as a tool for scholarly support and recommend that future research examine its implications for research workflows, emphasizing the need to explore this context further. In addition, only a few studies have applied MCDM methods to GAI use in higher education, targeting classroom teaching/learning. MCDM methods highlight trade-offs between adoption drivers and barriers. However, no study has used these methods to explore GAI adoption in academic research processes. This gap needs investigation.

Addressing this combined methodological and contextual gap, the present study identifies and ranks key adoption factors using TOPSIS and VIKOR MCDM methods. We identify candidate factors through a systematic literature review using thematic analysis and classify each candidate factor as an anticipated benefit, cost, or contextual and individual. The findings of this study will serve as a foundational basis for future grounded research aimed at improving existing information system adoption frameworks. It will also guide HEIs in assessing the adoption of GAI among academic researchers, enabling them to systematically identify, evaluate, and manage the potential benefits and risks associated with integrating these tools into research workflows. Grounded in Social Exchange Theory’s reward-vs-cost logic (Blau, 1964) and Net-Valence Theory’s benefit-minus-risk view (Featherman & Pavlou, 2003), we formulated two core research questions:

-

1.

Which are the perceived benefits, risks and contextual factors that affect the adoption of GAI into academic research by academics in HEIs?

-

2.

Among the identified factors, which exert the greatest influence on the adoption of GAI by academic researchers in HEIs?

To address these questions in a comprehensive manner, we set and achieved the following objectives:

-

1.

Conduct a structured literature review to identify and describe all relevant adoption factors across costs, benefits, and contextual/individual using thematic analysis.

-

2.

Apply MCDM methods to rank and prioritize them for targeted recommendations.

The remainder of this study unfolds as follows: A comprehensive literature review introduces and evaluates existing studies pertinent to GAI adoption by academics for research tasks. The research methodology section details factor identification using thematic analysis, questionnaire development, and introduces the TOPSIS and VIKOR methodologies employed. The subsequent Results section presents comparative rankings of the adoption factors using both MCDM methods, supplemented by algorithmic implementations provided through Python. The discussion section discusses the main results and implications. The limitations and future research section discusses the limitation of this study and suggests further avenues for extending information systems frameworks in GAI adoption. Ultimately, the insights derived from this research offer foundational guidance for HEIs aiming to strategically manage the implementation of GAI in academic research settings.

Literature review

GAI in academic research

GAI is increasingly embedded across all main phases of academic research handled by researchers including discovery and exploration, writing and reporting, and data analysis. Tools like ChatGPT and Bard quickly identify research gaps, suggest hypotheses, and assist with methodological planning, significantly shortening the preliminary exploration phase (Dashti et al., 2023; Firat, 2023; Tsufim & Pomerleau, 2024). Literature review platforms, such as AI Scholar and Elicit, rapidly summarize and categorize extensive scholarly databases, enhancing researchers’ efficiency despite some limitations around accuracy (Alshami et al., 2023; Bond et al., 2024). GAI tools also automate data analysis tasks including data cleaning, statistical interpretation, visualization, and thematic coding, facilitating quicker insight generation, though they still require human oversight to ensure validity (Hassani & Silva, 2023; Semrl et al., 2023).

Further along the research workflow, GAI writing assistants support researchers by drafting, editing, and refining manuscript content, especially beneficial for non-native English speakers, but vigilance is needed to prevent subtle bias or inaccuracies (Ariyaratne et al., 2023; Kassem & Michahelles, 2023). Although traditional GAI referencing tools have limitations such as citation inaccuracies, recent plugins like Consensus and Scholar GPT, integrated with databases such as Google Scholar and JSTOR, offer improved reliability, though manual verification remains essential (Aiumtrakul et al., 2023; Khalifa & Ibrahim, 2024). Overall, while GAI greatly enhances efficiency and productivity, researchers retain a critical role in verifying outputs to maintain scholarly rigor and accuracy throughout the research process (Alasadi & Baiz, 2023; Korinek, 2023).

Benefits

Several studies highlight that integrating GAI into the research workflow enhances productivity and task efficiency by enabling researchers to achieve more work in less time, with reduced effort and fewer resources required (Bond et al., 2024; Bringula, 2023). These studies report quality and speed gains in academic writing and manuscript drafting, particularly for structured scientific prose and for non-native authors (Dergaa et al., 2023). Moreover, the knowledge acquired from GAI tools enhances researchers’ abilities in problem-solving and informed decision-making. GAI also increases the accessibility of advanced research techniques to researchers, regardless of their technical skills or institutional resources (Jarrah, Wardat & Fidalgo, 2023; Park, 2023). Additionally, the use of GAI fosters the development of researchers’ digital literacy and technical proficiency (Leong, 2023; Pigg, 2024). GAI tools also facilitate knowledge sharing and dissemination, supporting collaboration and effective communication within the academic community (Zohouri, Sabzali & Golmohammadi, 2024).

Barriers to adoption

Despite reported benefits, integrating GAI tools into research has generated societal and institutional concerns, often causing resistance from researchers and stakeholders. Key worries include ethical issues related to AI-driven decisions and transparency of use, accuracy risks from biases or errors in automated processes, cognitive risks arising from researchers’ overreliance on AI, and fears of job displacement due to automation. Public perceptions of AI-assisted research as morally questionable, less trustworthy, and inferior to human-led research reflect doubts about GAI’s capability to replicate human creativity and uphold ethical standards (Khogali & Mekid, 2022; Niszczota & Conway, 2023). At the institutional level, scholars emphasize potential declines in critical thinking and originality, risks of plagiarism, and threats to data privacy and security, stressing the importance of maintaining academic rigor (Rahman & Watanobe, 2023; Salvagno et al., 2023). Studies also reveal fragmented and cautious adoption among researchers despite awareness of tools like ChatGPT, with practical usage limited due to insufficient training and clear institutional guidelines (Abdelhafiz et al., 2024; Dorta-González et al., 2024; Iyengar et al., 2023). Addressing these barriers through institutional support is essential for promoting trust and effective integration of GAI into academic research workflows.

MCDM techniques in GAI adoption

MCDM covers canonical problem types including choice (selecting one or a few best alternatives), ranking/prioritization (ordering alternatives from best to worst), and sorting/classification (assigning alternatives to predefined categories) (Roy, 1996). Major methods include value/utility models such as the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), ideal-solution approaches such as the Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) and VIKOR (Multi-criteria Optimization and Compromise Solution), and outranking methods such as Elimination and Choice Translating Reality (ELECTRE) (Cinelli et al., 2020). Multi-attribute group decision-making (MAGDM) extends MCDM to multiple experts, who provide evaluations that are then combined (by aggregation or explicitly within the model) to yield a group ranking/choice. Ideal-solution methods such as TOPSIS and VIKOR are widely employed to produce group rankings in multi-attribute group settings, complementing weighting-oriented methods such as AHP/BWM (Opricovic & Tzeng, 2004; Shih, Shyur & Lee, 2007; Wan, Wang & Dong, 2013).

MCDM methods have been employed across various domains to systematically rank and prioritize factors influencing the adoption of GAI. In the supply chain sector, Sharma & Rathore (2024) utilized Delphi and Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) alongside sentiment analysis, highlighting ethical practices, societal trust, and transparency. Nguyen, Nguyen & Nguyen (2024) implemented a probabilistic fuzzy hybrid model combining AHP and Combined Compromise Solution (CoCoSo) in the telecommunications industry, emphasizing managerial competencies, technology readiness, and security. Wang et al. (2023) applied Delphi, Analytic Network Process (ANP), and fuzzy TOPSIS in the construction industry to focus on strategic implementation factors such as digitalization, innovation, and productivity.

Within the educational domain specifically, several studies have leveraged MCDM methods to prioritize factors influencing Artificial Intelligence adoption in the learning/teaching context. Gupta & Bhaskar (2020) for instance used the AHP for prioritizing factors influencing teachers’ adoption of AI-driven educational technologies for teaching and learning. Similarly, Wiangkham & Vongvit (2024) employed the Weighted Sum Method (WSM) and explainable AI framework to identify key drivers for ChatGPT adoption by students in higher education. Priya et al. (2022) employed ISM and DEMATEL, focusing primarily on organizational readiness for AI integration. Yet, as highlighted by Batista, Mesquita & Carnaz (2024) most studies so far have focused on student-facing applications of GAI (e.g., as learning aids or classroom tools) and on developing ethical guidelines for its use, rather than on faculty’s own research-oriented use of these tools. Empirical work examining how faculty adopt GAI in their scholarly research remains sparse, and no studies have employed structured decision models to prioritize the factors influencing faculty adoption of GAI for their academic research tasks. Addressing this gap is crucial to establishing best practices for adopting GAI in faculty research. Using structured decision-making methods to identify and rank the main factors influencing GAI adoption can help institutions clearly understand faculty needs. This approach enables universities to offer targeted support to researchers, promoting responsible and effective integration of GAI into their academic work.

Materials and Methods

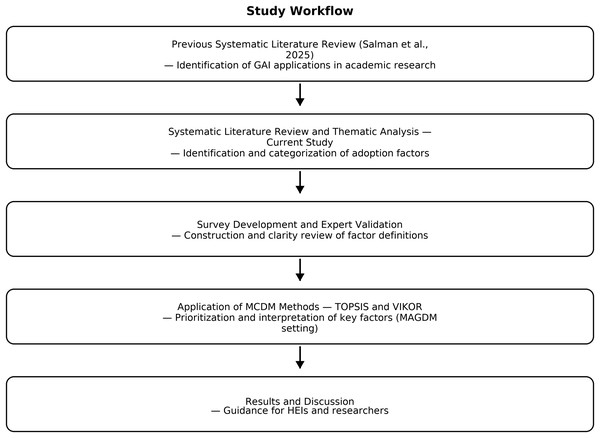

This study follows a structured, multi-step design integrating a Systematic Literature Review (SLR), thematic analysis, and MCDM (TOPSIS and VIKOR) to identify and rank factors influencing GAI adoption in academic research within HEIs. Figure 1 summarizes the study workflow, beginning with a systematic review and thematic analysis to identify adoption factors, followed by survey development and factor prioritization using TOPSIS and VIKOR in a MAGDM setting.

Figure 1: Workflow summarizing the systematic review, thematic coding, survey, and TOPSIS–VIKOR ranking steps (Salman et al., 2025).

Factor extraction

Systematic literature review (PRISMA)

Building upon our prior SLR that explored the applications and implications of GAI in academic research, this study aims to delve deeper into the factors influencing GAI adoption for academic research and scholarly applications within HEIs. To achieve this, we conducted a comprehensive SLR following the PRISMA (Takkouche & Norman, 2011) to examine current findings and uncover gaps that require further investigation. A systematic search was performed across two major academic databases: Web of Science and Scopus.

Research scope

The objective of this SLR was to identify and analyze peer-reviewed studies focusing on the adoption of GAI tools in academic research contexts within HEIs. The review specifically targeted studies that discussed enablers, barriers, and contextual and individual factors affecting GAI adoption into research workflows. Studies solely addressing GAI applications in teaching and learning were excluded to maintain a focused scope.

Eligibility criteria

Clear inclusion and exclusion parameters preserve the rigor and relevance of a literature review. These parameters direct investigators to studies that meet predefined standards and exclude inappropriate records, strengthening the accuracy and reliability of subsequent evidence. Table 1 lists the inclusion and exclusion criteria applied during literature screening. The review considered articles published from Dec. 2021 through Mar. 2025.

| Criterion | Decision |

|---|---|

| The article discusses GAI and includes relevant keywords in the title, abstract, or tags | Include |

| The study is published in a peer-reviewed academic journal or conference | Include |

| The publication is written in English | Include |

| Articles that could not be retrieved or accessed | Exclude |

| Papers that are editorials, commentary, or non-original reviews | Exclude |

Search procedure

The review began with a protocol designed to capture all pertinent publications. The authors compiled an initial keyword list and used it to retrieve a broad set of records. They screened a sample of these articles to identify additional, previously missed terms and interviewed domain experts to refine the list further. The authors performed a series of preliminary searches, revising the keyword set after each round to accommodate new terms that surfaced during screening. The finalized keywords with their synonyms and the complete Boolean search strings (using the operators OR, AND, and NOT) for Scopus and Web of Science queries are presented in Table 2.

| Database | Search string | No. of articles | Acquisition date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scopus | (Title, Abstract, Keywords) (((“generative ai” OR “generative artificial intelligence” OR ChatGPT OR gpt) AND (adoption OR acceptance OR perception* OR intention)) AND (researcher* OR faculty OR scholar* OR academic) AND NOT (student* OR learner* OR undergraduate* OR postgraduate* OR teach*)) |

458 | 2/3/2025 |

| Web of science | 274 | 6/3/2025 |

Screening and study selection

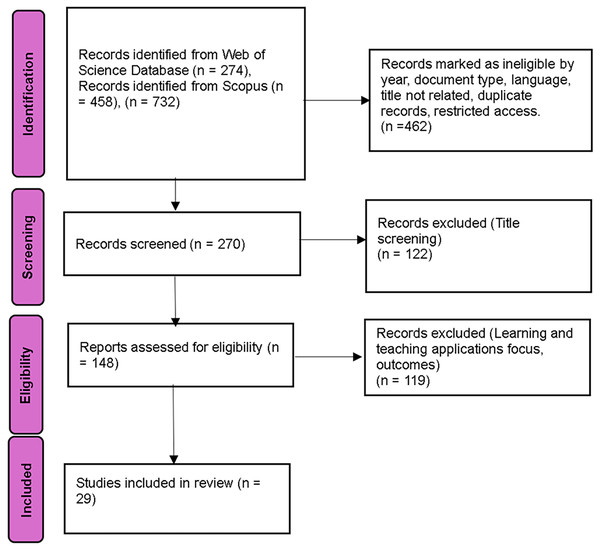

The database queries resulted in a total of 732 records, 274 from Web of Science and 458 from Scopus. Following the PRISMA guidelines, these records underwent initial filtering based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria, such as publication year, document type, language, relevance of titles, duplicate entries, and restricted access. This filtering step removed 462 ineligible records, leaving 270 studies for title screening. Subsequent title screening excluded an additional 122 studies, resulting in 148 reports advancing to the eligibility assessment stage. At the eligibility stage, another 119 reports were excluded due to their focus on learning and teaching applications solely. Ultimately, 29 studies satisfied all inclusion criteria and advanced to the full analysis stage, as depicted in the PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: PRISMA flow diagram showing identification, screening, eligibility and inclusion of 29 studies on generative AI.

Thematic analysis

To analyze qualitative data from the selected studies, thematic analysis was conducted using MAXQDA qualitative analysis software (Kuckartz & Rädiker, 2019). The primary objective was identifying key factors influencing researchers’ adoption of GAI. The analytical approach followed (Wolcott, 1994) qualitative framework, recognized for its clarity and effectiveness in synthesizing literature findings. The analysis involved four distinct steps: First, relevant segments related to GAI adoption were highlighted and extracted from each primary study, forming preliminary insights. Second, these insights were systematically coded in MAXQDA, initially generating clear, descriptive codes. Third, the primary coder refined the coding iteratively with the other authors. Similar or overlapping codes were merged or renamed. After refining the codes, the other three authors reviewed all tagged segments. Disagreements (about 8%) were discussed and settled through consensus. A random check of 10% of the final segments indicated 92% agreement, showing acceptable reliability (Guest, MacQueen & Namey, 2011). Finally, the resultant themes were organized into broader conceptual categories aligned with the study’s core constructs of benefits, costs, and contextual and individual themes. Age and gender were removed from the evaluation set because several frameworks such as UTAUT and TAM position them as moderating variables rather than decision criteria; they will therefore be modelled only as moderators in subsequent analyses. Following recommendations for pragmatic thematic analysis, we maintained a single-level codebook and documented sub-themes via code memos (Guest, MacQueen & Namey, 2011; Kuckartz & Rädiker, 2019).

Factor prioritization (ranking)

MCDM instrument and data collection

The unit of analysis is the relative importance of adoption factors across research stages. We examine benefits, costs, and contextual/individual influences. These factors are tool-neutral and were identified via thematic analysis. The first section of the survey collected demographic data, discipline, and researchers’ experience with using GAI in research practices. Following a thematic analysis, we identified 18 factors. For the MCDM evaluation, Age and Gender were excluded as moderators, leaving 17 factors to be rated on a Likert scale. Participants were faculty members affiliated with IEEE Bahrain Section, University of Bahrain, Kingdom University, the Artificial Intelligence Society, and the American University of Bahrain. Due to the specialized nature of the topic and practical constraints in accessing researchers actively involved in using GAI, we employed convenience sampling (Bhattacherjee, 2012). We received 92 responses. After excluding 11 who did not experience using GAI in research tasks, 81 valid responses remained, yielding approximately a 71% response rate which is acceptable for most MCDM studies. Bahrain’s higher-education workforce totals 2,137 faculty members (Bahrain Open-Data Portal, n.d.) In the margin-of-error formula (Krejcie & Morgan, 1970), the variables are defined as follows: z0.975 = 1.96 corresponds to the standard normal value at the 95% confidence level; p = 0.50 represents the maximum variance condition; n = 81 the sample size; and N = 2,137 is the total population of higher education faculty members in Bahrain. Using these values, the margin of error is approximately ±10.7 percentage points, indicating that estimates from the sample will fall within ±10.7 percentage points of the actual population parameters, at a 95% confidence level.

Table 3 summarizes the demographic characteristics of respondents. The expert panel covers a wide variety of disciplines, career stages, and practical experience. Respondents come from Business (27%), STEM (38%), Social Sciences & Humanities (22%), and Arts & Design (12%), reflecting disciplinary breadth. Their work experience is diverse, with 31% having 5–10 years, 23% having 11–16 years, and 37% over 16 years in academia. The majority hold advanced degrees (PhD = 53%, Master’s = 40%) and publish regularly (47% have ≥6 publications). On average, respondents have actively used GAI tools for approximately 1.5 years, with 62% reporting 1–2 years and 16% exceeding 2 years, indicating robust, practice-based familiarity with GAI adoption factors.

| Demographic characteristics | Categories | Respondents (n) | Respondents (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 42 | 51.85% |

| Female | 39 | 48.15% | |

| Age | 25–30 | 5 | 6.17% |

| 31–36 | 15 | 18.52% | |

| 37–42 | 21 | 25.93% | |

| 43–48 | 26 | 32.10% | |

| >49 | 14 | 17.28% | |

| Work experience | Less than 5 years | 7 | 8.64% |

| 5–10 years | 25 | 30.86% | |

| 11–16 years | 19 | 23.46% | |

| More than 16 years | 30 | 37.04% | |

| Discipline | Business | 22 | 27.16% |

| Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics | 31 | 38.27% | |

| Social sciences & Humanities | 18 | 22.22% | |

| Arts & Design | 10 | 12.35% | |

| Education level | Bachelor’s | 6 | 7.41% |

| Master’s | 32 | 39.51% | |

| PhD | 43 | 53.09% | |

| GAI usage experience in research tasks | 6 months–1 year | 18 | 22.22% |

| 1–2 years | 50 | 61.73% | |

| More than 2 years | 13 | 16.05% | |

| Subscription type | Free | 49 | 60.49% |

| Paid | 32 | 39.51% | |

| Number of publications | Less than 5 | 38 | 46.91% |

| 6–11 | 29 | 35.80% | |

| 12–17 | 11 | 13.58% | |

| More than 17 | 3 | 3.70% |

Following thematic analysis, we identified 18 factors influencing GAI adoption by researchers. Each factor was clearly defined in the second part of the survey to ensure respondents’ comprehension and accurate responses. Table 4 presents the operational definitions of the 17 evaluated adoption factors.

| SN | Factor | Statement | Factors definitions sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Self-efficacy | Researcher’s belief in his/her ability to successfully use GAI to accomplish academic research tasks. | Fu et al. (2024) |

| 2 | Innovativeness | Refers to an individual’s tendency to adopt and experiment with new technologies. | Strzelecki (2024), Foroughi et al. (2023) |

| 3 | AI literacy | Refers to researchers’ proficiency and digital skills in using GAI to achieve desired outcomes. | Hidayat-ur-Rehman & Ibrahim (2024) |

| 4 | Experience | Refers to the prior knowledge and familiarity researchers have with GAI tools. | Romero Rodríguez et al. (2023) |

| 5 | Social influence | Refers to the impact of peers or societal and cultural norms on the decision to adopt GAI. | Venkatesh et al. (2003) |

| 6 | Facilitating conditions | Refers to the availability of resources, infrastructure, and technical support that enable researchers to effectively use GAI such as training and institutional support. | Venkatesh et al. (2003) |

| 7 | Performance risk | Refers to concerns about the ability of GAI to perform academic research tasks reliably and accurately. | Tao, Yang & Qu (2024) |

| 8 | Ethical concerns | Refers to concerns regarding AI model transparency, data privacy, embedded biases, and potential misuse impacting academic integrity when using GAI tools in academic research. | Esmaeilzadeh (2020) |

| 9 | Effort expectancy | Refers to the perceived effort associated with using GAI for the tasks of academic research process. | Venkatesh et al. (2003) |

| 10 | Job security | Refers to the concerns researchers have about the impact of GAI tools on their employment stability. | Caporusso (2023) |

| 11 | Regulatory concerns | Refers to the concerns about the absence of or compliance with laws and regulations, such as copyright and intellectual property when using GAI for academic research. | Esmaeilzadeh (2020) |

| 12 | Cognitive risk | Refers to the concerns researchers have about overly reliance on GAI tools in academic research, weakening their independent reasoning, creativity, or critical-thinking capabilities. | Link & Beckmann (2025), Zhai, Wibowo & Li (2024) |

| 13 | Task efficiency | Refers to the ability of GAI tools to help researchers complete specific tasks more quickly and with fewer resources. | Fu et al. (2024) |

| 14 | Accessibility | Refers to the ease in which researchers can access and retrieve information using GAI. | Baabdullah (2024) |

| 15 | Hedonic motivation | Refers to the degree of pleasure or enjoyment a researcher derives from using GAI tools. | Venkatesh, Thong & Xu (2012) |

| 16 | Knowledge sharing | Refers to the process of using GAI to distribute, exchange, and communicate knowledge among researchers. | Duong, Vu & Ngo (2023) |

| 17 | Knowledge acquisition | Refers to the process by which researchers obtain new information and progressively enhance their understanding as they interact with GAI tools. | Jo (2024) |

Ethics

The study protocol adhered to institutional review board guidelines. Participants were informed through the Microsoft Forms survey about the confidentiality of their data, the voluntary nature of their participation, and assurance that no personally identifiable information would be collected. Findings are presented only in aggregate form to ensure participant anonymity and confidentiality.

MCDM procedures

In this study, both TOPSIS and VIKOR factor prioritization are utilized in a MAGDM setting. We selected ideal-distance and compromise methods (TOPSIS, VIKOR) instead of ratio-based pairwise approaches (AHP, BWM), as no defensible a priori hierarchy of factors was available and experts supplied direct importance ratings, aligning with method-selection taxonomies and the formal characterization of these techniques (Cinelli et al., 2020; Corrente & Tasiou, 2023; Ishizaka & Labib, 2011; Opricovic & Tzeng, 2004). The extracted factors serve as alternatives (i.e., the entities to be ranked), while the experts provide ratings that serve as criteria (i.e., the dimensions for evaluation). This approach is consistent with standard MCDM applications where multiple criteria are used to evaluate alternatives, and it allows us to aggregate expert opinions into a consensus ranking. Eighty-one experts provide benefit-type importance ratings on a five-point Likert scale, producing a decision matrix where (factors, rows) and (experts, columns). Each expert is treated as a criterion. Given a single homogeneous expert panel with no validated basis for differential credibility we assign equal weights . We treated 5-point Likert ratings as approximately interval to enable normalization and distance-based aggregation in TOPSIS/VIKOR; this choice is supported by evidence that parametric operations on Likert-type data are robust (Norman, 2010). To ensure the reliability of expert ratings, we assess inter-rater agreement using ICC(3, k) (two-way mixed effects, absolute agreement, average measures; 95% CI). The robustness of the equal-weight assumption is verified through leave-one-expert-out sensitivity analysis (LOEO).

We compute ranks with two ideal-solution methods to provide cross-method validation (Gul et al., 2016). TOPSIS ranks factors based on their geometric closeness to ideal solutions across all expert criteria. VIKOR provides a compromise ranking that balances group utility and individual regret with baseline . Varying from 0.3 to 0.7 in increments of 0.1 did not alter the composition of the Top-5 factors. Rank concordance between the two methods is assessed with Spearman’s rho .

Notation and symbols

Let be the set of factors (m = 17) and be the set of experts (n = 81).

Let. be the decision matrix of raw ratings, where is the rating assigned by expert to factor ( ; ).

Let be the vector of expert weights, we shall suppose in our approach that all weights are equal to . Therefore, .

All criteria are treated as benefit-type; therefore, higher ratings indicate greater importance.

TOPSIS procedure

1. Normalization: Each expert’s ratings are normalized to eliminate scale differences using vector normalization. This ensures that each criterion (expert) contributes equally to the distance calculations. (1)

2. Weighting: The normalized matrix is weighted using the expert weights to incorporate their equal importance into the model: (2)

3. Ideal solutions: Let the Positive Ideal Solution (PIS) and Negative Ideal Solution (NIS) for each criterion be defined as follows: (3)

4. Distances: The Euclidean distances of each factor from the PIS and NIS are calculated: (4)

5. Relative closeness: The closeness coefficient is computed: (5)

6. Ranking: Factors are ranked in descending order of . Thus, the best factor is most important where (6)

VIKOR procedure

-

1.

Best and worst values: For each criterion (expert), the best and worst raw ratings are identified. (7)

-

2.

The gap for each factor-expert pair is computed to measure the deviation from the best value, with a small constant to prevent division by zero. (8)

-

3.

Group utility and individual regret: The group utility (average gap) and individual regret (maximum gap) are calculated for each factor. (9)

-

4.

Reference values for : compute the across-factor reference values denoted (best) and (worst) from and (best) and (worst) from . These values define the scale used in Eq. (11). (10)

-

5.

-

6.

Ranking: Factors are ranked in ascending order of ; The factor with the lowest is considered the factor that has the best compromise, that is, the lowest compromise.

Reliability and convergence

Intraclass correlation coefficient

We assessed inter-rater reliability using the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC). Following (McGraw & Wong, 1996) we used the ICC(3,k) model—two-way mixed-effects (raters treated as fixed), consistency, average-measures—which estimates the reliability of the mean rating across k raters. In this study, k = 81 experts and the “items” are the 17 adoption factors rated by each expert. For our 81 experts on 17 factors, the analysis indicated excellent reliability (ICC = 0.975, 95% CI [0.956–0.989]) as presented in Table 5. This validation aligns with recent MCDM studies that have similarly applied ICC (3,k) for confirming the robustness of averaged expert ratings prior to multi-criteria analyses (Chountalas et al., 2025; Liu et al., 2024; Papagiannis et al., 2025).

| Type | Point estimate | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICC3,k | 0.975 | 0.956 | 0.989 |

Note:

18 subjects and 81 raters. ICC type as referenced by Shrout & Fleiss (1979).

Spearman’s rank-correlation coefficient

The pairwise rank concordance between the TOPSIS and VIKOR methodologies was assessed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (ρ). Let and denote the integer ranks of factor obtained from the TOPSIS and VIKOR methods, respectively. The coefficient ρ and its associated p-value are calculated and reported to quantify the agreement between the two ranking schemes. Spearman’s ρ (tie-aware) is computed as:

(12) where

Sensitivity testing

To assess the sensitivity of the rankings to the equal-weights assumption, a leave-one-expert-out jackknife analysis was performed. This test is a resampling method that removes one data column at a time and reruns the analysis (Quenouille, 1956; Tukey, 1958). Each expert was sequentially excluded by setting their weight to zero and renormalizing the remaining weights to sum to one. For each such perturbed weight set, TOPSIS and VIKOR rankings were recomputed, and the outcomes were summarized using the median Spearman’s ρ against the baseline and the degree of Top-5 factor preservation.

Results

Primary studies profile

Table 6 summarizes the methodological profile and focus of the 29 primary studies. The studies utilized diverse research methods, including qualitative, quantitative, mixed methods, and review-based methodologies. Qualitative methods included case studies, grounded theory, thematic analysis, and descriptive frameworks. Quantitative studies predominantly used survey methods analyzed through structural equation modeling (SEM), alongside experimental and observational designs to examine faculty and researcher adoption patterns, perceptions, and performance comparisons between GAI and human writing. Mixed-method approaches combined qualitative insights from interviews with quantitative survey data, offering a holistic exploration of GAI adoption.

| SN | Authors | Study type | Study focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | Watermeyer et al. (2023) | Mixed methods | Faculty adoption of GAI |

| A2 | Cambra-Fierro et al. (2024) | Quantitative (survey, SEM) | Faculty adoption of ChatGPT |

| A3 | Livberber (2023) | Qualitative study (case study) | Academic writing using GAI tools |

| A4 | Pigg (2024) | Qualitative (Descriptive framework) |

Embodied practice of research writing with ChatGPT |

| A5 | Bringula (2023) | Systematic review (text mining) | Academic perceptions of ChatGPT in research writing |

| A6 | Dergaa et al. (2023) | Systematic review | Prospects/threats of ChatGPT in academic writing |

| A7 | Soodan et al. (2024) | Mixed methods | Faculty adoption of ChatGPT |

| A8 | Carabantes, González-Geraldo & Jover (2023) | Scoping review | GAI models in review of articles |

| A9 | Fegade et al. (2023) | Mixed methods | Potential and challenges of generative artificial intelligence in academia |

| A10 | Ivanov et al. (2024) | Quantitative (survey, SEM) | Adoption of GAI in HEIs |

| A11 | Abdelhafiz et al. (2024) | Quantitative (survey) | Researchers’ perceptions of GAI in research |

| A12 | Biswas, Dobaria & Cohen (2023) | Qualitative (case study) |

ChatGPT in the review process of articles |

| A13 | Kassem & Michahelles (2023) | Quantitative (experimental) | ChatGPT in scientific writing |

| A14 | Zohouri, Sabzali & Golmohammadi (2024) | Qualitative (grounded theory) | Ethical considerations of ChatGPT in article writing |

| A15 | Fu et al. (2024) | Quantitative (survey, SEM) | Adoption of ChatGPT in academic settings including coping mechanisms |

| A16 | Izhar, Teh & Adnan (2025) | Quantitative (survey, SEM) | Researchers’ GAI adoption |

| A17 | Casal & Kessler (2023) | Quantitative (experimental) | Distinguishing academic writing of artificial intelligence vs. human |

| A18 | Nicholas et al. (2024) | Mixed methods | Impact of GAI on early career researchers’ scholarly |

| A19 | Yan et al. (2024) | Qualitative | Human-artificial intelligence collaboration in thematic analysis |

| A20 | Khalifa & Ibrahim (2024) | Scoping review | ChatGPT in scientific writing |

| A21 | Cheng et al. (2023) | Quantitative (observational) | ChatGPT generated vs. human-written abstracts |

| A22 | Bhat et al. (2024) | Quantitative (survey, SEM) | ChatGPT adoption by faculty members. |

| A23 | Ng et al. (2025) | Mixed methods | Researchers’ attitudes to GAI tools |

| A24 | Nazzal et al. (2024) | Quantitative (experimental) | Artificial intelligence vs. human writing in review articles |

| A25 | Saad et al. (2024) | Quantitative (observational) | ChatGPT in peer review process |

| A26 | Athaluri et al. (2023) | Quantitative (observational) | Hallucination in ChatGPT references |

| A27 | Garcia (2025) | Quantitative (survey, SEM) | Factors influencing ChatGPT adoption for academic writing |

| A28 | Al-Zahrani (2023) | Quantitative (survey) | GAI impact on research in higher education |

| A29 | Firat (2023) | Qualitative (thematic analysis) | Perceptions of ChatGPT in universities |

Regarding the research context, the reviewed studies collectively address various aspects of GAI integration in higher education and research. Contextual focuses include faculty adoption behaviors, perceptions toward ChatGPT, academic writing practices, and peer-review processes. Studies also explored ethical issues, collaboration dynamics between humans and AI, coping mechanisms, and accuracy-related concerns such as hallucinations.

Thematic analysis results

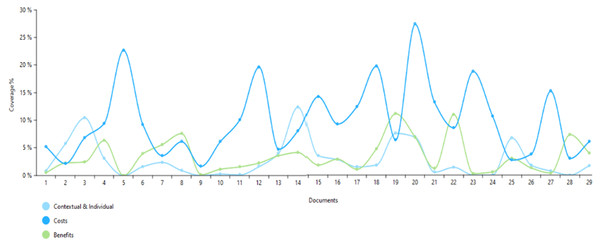

Addressing RQ1 the thematic analysis identified 18 factors across 29 studies grouped under three main themes: Costs, Benefits, and Contextual & Individual. As shown in Fig. 3, per-document coverage favors costs (dark blue) across most studies, while benefits (green) are lower and more variable, and contextual & individual factors (light blue) are least emphasized.

Figure 3: Coverage of cost, benefit, and contextual/individual themes across the 29 reviewed studies.

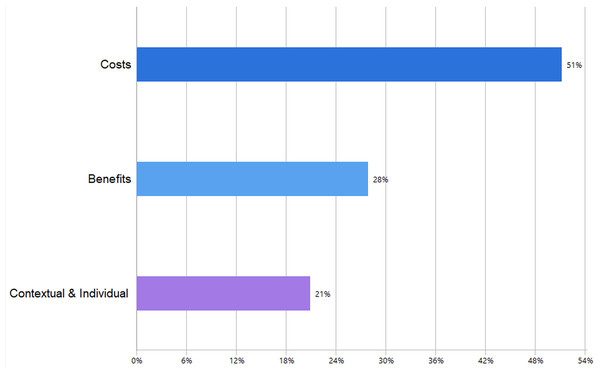

Figure 4 presents the frequency distribution of the coded factors. “Costs” account for the largest share (51%), representing perceived barriers, and risks that may hinder researchers’ adoption of GAI. “Benefits” make up 28% of the coded data and reflect enabling factors and positive outcomes, that encourage adoption. “Contextual and Individual” factors contribute the remaining 21%, encompassing external conditions and personal characteristics shaping researchers’ adoption decisions. The figure demonstrates that cost-related considerations dominated the coding, followed by benefits and contextual/individual influences.

Figure 4: Relative share of coded segments classified as costs, benefits, and contextual/individual factors.

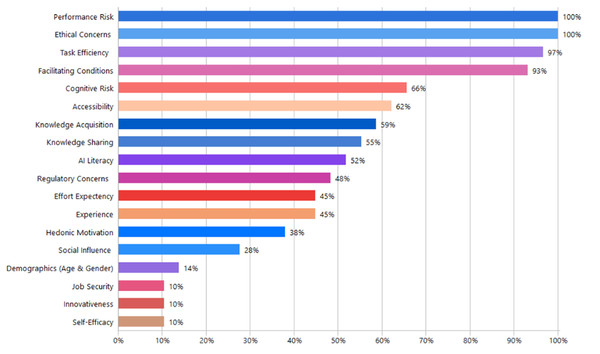

Figure 5 illustrates how often each thematic factor appears across the reviewed documents. Ethical Concerns and Performance Risk were mentioned most frequently, each appearing in all analyzed documents (100%). These were closely followed by Task Efficiency and Facilitating Conditions, representing 97% and 93% of the documents respectively. Cognitive Risk was also frequently mentioned, appearing in 66% of documents, followed by Accessibility (62%) and Knowledge Acquisition (59%). Knowledge Sharing was discussed in just over half of the sources (55%), while AI Literacy and Regulatory Concerns each appeared in nearly half (48%). Less frequently noted were Experience and Effort Expectancy, both at 45%. Hedonic Motivation (38%), Social Influence (28%), and Demographics (14%) appeared less often, with Innovativeness, Self-Efficacy, and Job Security being the least frequently mentioned, each at 10%. Although the frequency of thematic factors reflects their prominence in analyzed studies, a slightly lower frequency does not necessarily mean reduced importance. Differences in study objectives, research designs, or specific tasks can influence which factors are emphasized. For instance, Facilitating Conditions appeared in 93% of documents, slightly below the highest frequency, but this might reflect that certain studies were experimental, focusing specifically on testing GAI for tasks like abstract writing or citation generation, rather than directly examining enabling conditions or support systems.

Figure 5: Proportion of studies that mention each thematic factor influencing generative-AI adoption.

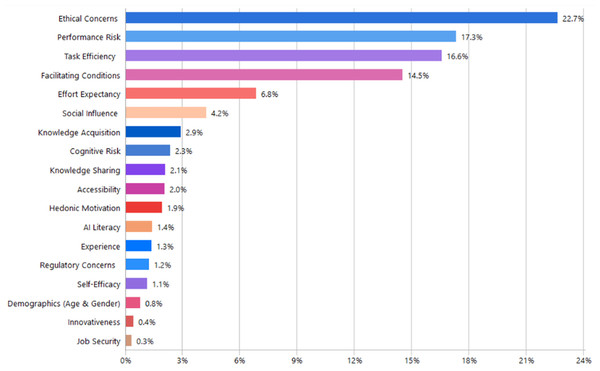

The distribution of factors based on coded segment frequency is shown in Fig. 6. Ethical Concerns dominated with the highest frequency, accounting for 22.3% of all coded segments. Performance Risk followed at 17.0%, with Efficiency and Facilitating Conditions close behind 16.3% and 15.9%, respectively. Effort Expectancy accounted for a moderate 6.7% of segments. Social Influence was cited less frequently at 4.2%, while Knowledge Acquisition (2.8%), Cognitive Risk (2.3%), Knowledge Sharing (2.0%), and Accessibility (2.0%) were referenced sparingly. Hedonic Motivation appeared in 1.9% of segments, and the least frequently represented factors were AI Literacy (1.4%), Experience (1.3%), Regulatory Concerns (1.2%), Self-Efficacy (1.1%), Demographics (0.8%), Innovativeness (0.4%), and Job Security (0.3%).

Figure 6: Share of total coded segments attributed to each thematic factor.

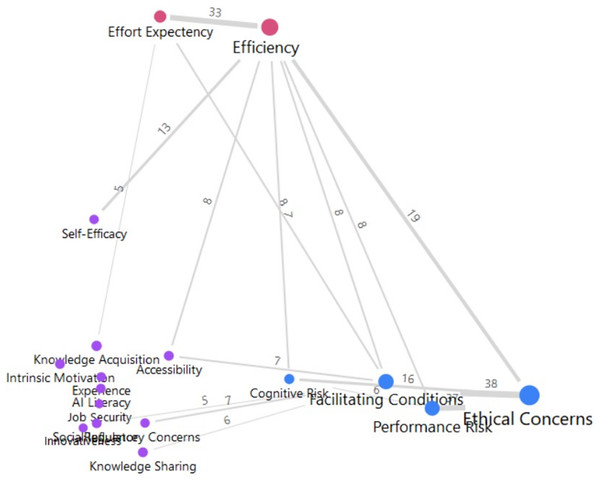

The direct co-occurrences of the identified factors within the analyzed segments are illustrated in Fig. 7. The map represents thematic relationships with a minimum frequency of five or more co-occurrences. Node size and font reflect how frequently each theme occurred, with larger nodes indicating higher overall occurrence. Line thickness represents the strength of specific relationships between pairs of themes, with thicker lines indicating more frequent co-occurrences. Ethical Concerns is the most prominent node, indicating substantial overlap with various themes, especially Performance Risk (38 segments). The strongest single co-occurrence observed is between Efficiency and Effort Expectancy (33 segments). This emphasizes the frequent association of GAI’s productivity benefits with users’ perceptions regarding learning curve and the degree of effort required to use effectively use these tools. Other notable connections include Efficiency with Facilitating Conditions (19 segments), underscoring institutional support’s role in enhancing users’ perceived efficiency. Contextual and individual factors such as AI Literacy, Knowledge Acquisition, and Experience show moderate to fewer connections, suggesting they primarily serve as moderating influences.

Figure 7: Network of theme co-occurrences highlighting links between benefits, costs, and contextual factors.

Contextual and individual themes

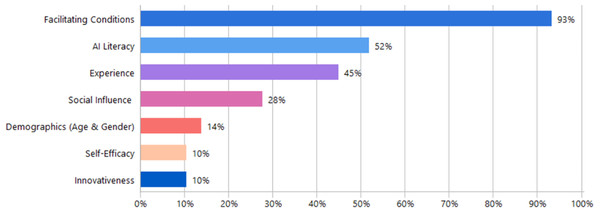

The thematic analysis identified several specific contextual and individual factors influencing the adoption of GAI tools by researchers in academic contexts. Seven sub-codes were identified (Demographics, innovativeness, self-efficacy, facilitating conditions, prior experience, AI literacy, and social influence) as illustrated in Table 7, along with the supporting studies. Several studies indicated that demographic factors of age and gender affect adoption level. These studies reported that age works as a moderator that strengths or weakens intentions to adopt GAI for instance, younger individuals generally have greater familiarity and more positive perceptions toward GAI tools. Another possible moderating factor is gender where male researchers showed higher intentions and usage rates, especially under conditions of high effort expectancy. Personal innovativeness was found to significantly influence adoption intentions and moderate related adoption factors. Additionally, researchers with higher self-efficacy were more inclined to adopt GAI tools. Facilitating conditions, including clear institutional policies, tailored training and support programs, and collaboration among institutions, policymakers, and developers, were highlighted as essential for effective adoption. Prior experience and familiarity (Experience), along with digital and (AI Literacy), were also noted as influential factors affecting researchers’ attitudes and usage. Figure 8 shows the distribution of contextual/individual factors based on document frequency. Facilitating Conditions appeared most frequently, mentioned in 93% of documents. AI Literacy was the second most common factor at 52%, followed by Experience at 45%. Social Influence was discussed in just over a quarter of the studies (28%), while Demographics, encompassing age and gender, appeared in only 14%. Self-Efficacy and Innovativeness were the least frequently mentioned individual-level factors, each present in only 10% of the documents.

| No. | Theme | Details | Supporting studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Demographics | ||

|

|

A11, A15, A18, A28 | |

|

|

A1, A15 | |

| 2. | Innovativeness |

|

A2, A15, A22 |

| 3. | Self-Efficacy |

|

A10, A15, A16 |

| 4. | Facilitating conditions |

|

A1, A2, A3, A4, A5, A6, A7, A8, A9, A10, A11, A12, A13, A14, A15, A16, A17, A18, A19, A20, A21, A22, A23, A24, A25, A26, A27, A28, A29 |

| 5. | Experience |

|

A1, A2, A7, A11, A15, A16, A17, A18, A19, A23, A27, A28 |

| 6. | AI literacy |

|

A4, A7, A9, A10, A12, A14, A15, A16, A17, A19, A27, A29 |

| 7. | Social influence |

|

A7, A10, A27 |

Figure 8: Frequency of contextual and individual factors across the reviewed documents.

Benefits

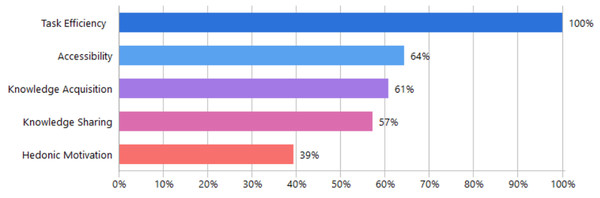

The thematic analysis identified five key benefits (knowledge acquisition, hedonic motivation, knowledge sharing, accessibility, task efficiency) influencing researchers’ adoption of GAI tools as shown in Table 8. Knowledge acquisition involves gaining new information through personalized and adaptive learning strategies. These features enhance researcher engagement and support decision-making. Hedonic motivation was another identified benefit, reflecting users’ enjoyment and entertainment from interacting with GAI tools, which subsequently enhances their intention to use it academically. Knowledge sharing and collaboration emerged prominently, including global academic collaboration facilitated by GAI, improved interdisciplinary partnerships, and peer-connectedness within academic communities. Additionally, accessibility benefits were identified, highlighting GAI’s ability to facilitate broader resource access 24/7 and promoting inclusivity and equity. Task efficiency presents GAI capability to streamline research by automating research stages of discovery, analysis, drafting and writing, thus reducing time and effort. Figure 9 presents the distribution of benefit-oriented factors based on document frequency. Task Efficiency emerged prominently, appearing in 97% of the analyzed documents. Accessibility was cited in 62% of documents, followed closely by Knowledge Acquisition (59%) and Knowledge Sharing (55%). Hedonic Motivation was the least frequently mentioned benefit, appearing in 38% of the documents.

| SN | Benefits | Details | Supporting studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Knowledge acquisition |

|

A2, A5, A6, A7, A9, A10, A14, A15, A16, A18, A22, A23, A27, A28, A29 |

| 2. | Hedonic motivation |

|

A2, A3, A4, A6, A15, A18, A20, A22, A25, A29 |

| 3. | Knowledge sharing |

|

A2, A3, A5, A6, A7, A10, A11, A12, A14, A15, A16, A18, A19, A27, A28 |

| 4. | Accessibility |

|

A1, A2, A4, A5, A7, A9, A10, A11, A12, A14, A15, A16, A17, A21, A22, A23, A25, A28 |

| 5. | Task efficiency |

|

All |

Figure 9: Frequency of benefit-oriented factors across the reviewed documents.

Costs

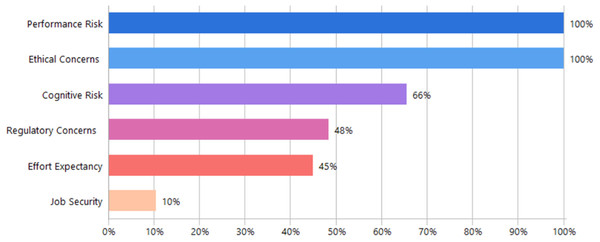

The thematic analysis identified six primary cost-related factors (job security concerns, effort expectancy, cognitive risk, regulatory concerns, performance risk, ethical concerns) that can hinder researchers’ adoption of GAI tools in academic contexts shown in Table 9. Job security emerged as a concern due to the perceived risk of job displacement and automation. Effort expectancy, referring to the effort required by users, impacts adoption intentions, indicating tools perceived as more intuitive and effortless are more likely to be adopted. For researchers using GAI, this refers to efforts required to learn, operate, and supervise GAI tools in academic research, including the time, cognitive load, and additional work needed to integrate and verify their outputs. Cognitive risk includes concerns about compromised critical thinking and analytical skills resulting from overreliance on AI-generated content. Regulatory concerns encompass worries about insufficient oversight, lack of institutional guidelines, and potential copyright issues related to AI-generated content. Performance risks address issues of content accuracy, AI-generated hallucinations, and AI’s limitations in evaluating complex tasks. Finally, ethical concerns emphasize risks related to unethical usage, plagiarism, over-reliance, and issues involving data privacy, security, transparency, algorithmic bias, and explainability of AI decisions.

| No. | Costs | Summery | Supporting studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Job security |

|

A7, A11, A18 |

| 2. | Effort expectancy |

|

A2, A4, A6, A7, A9, A10, A14, A15, A16, A17, A21, A22, A27 |

| 3. | Cognitive risk |

|

A1, A3, A6, A7, A9, A10, A11, A12, A14, A15, A16, A18, A19, A20, A23, A25, A26, A27, A28 |

| 4. | Regulatory concerns |

|

A10, A11, A12, A13, A15, A18, A20, A22, A23, A24 |

| 5. | Performance risk |

|

All |

| 6. | Ethical concerns |

|

All |

Figure 10 illustrates the distribution of cost or risk-related factors based on document frequency. Both Performance Risk and Ethical Concerns were universally mentioned, appearing in all analyzed documents (100%). Cognitive Risk followed with significant frequency at 66%, while Regulatory Concerns and Effort Expectancy were cited in approximately half of the documents, at 48% and 45%, respectively. Job Security appeared least frequently, being cited in only 10% of the analyzed sources.

Figure 10: Frequency of cost-related factors across the reviewed documents.

MCDM results

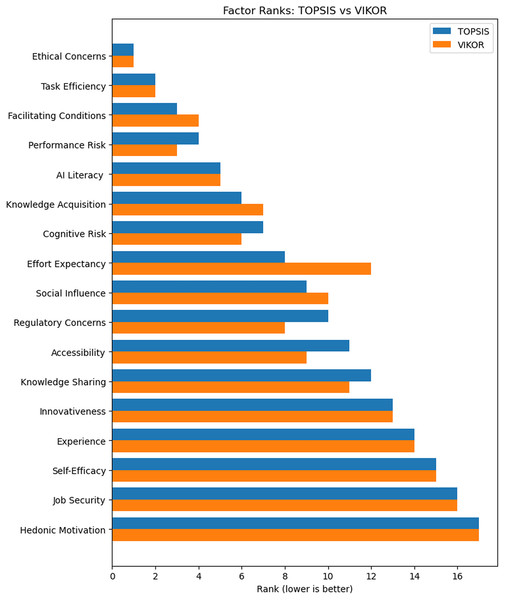

To answer RQ2 we used TOPSIS and VIKOR to assess and rank pool of factors identified in the thematic analysis stage (Table 10). Consolidated ranking of adoption factors based on TOPSIS (CCi) and VIKOR (Qi), showing scores, individual method ranks, combined ranks, and overall rank (with ties as ranges). Ethical Concerns ranks first in both methods, emphasizing its critical role. Both methods closely agree on the top factors: Task Efficiency is second, while Facilitating Conditions and Performance Risk alternate between third and fourth positions. However, some differences appear in middle rankings; for instance, Knowledge Acquisition ranks sixth in TOPSIS but seventh in VIKOR, swapping positions with Cognitive Risk. Regulatory Concerns moves from tenth in TOPSIS up to eighth in VIKOR, and Accessibility similarly advances from eleventh to ninth. Effort Expectancy shows the greatest disagreement, ranking eighth in TOPSIS (closeness = 0.637) but dropping notably to twelfth in VIKOR (Q = 0.163). The overall ranking was obtained by averaging the TOPSIS rank and the VIKOR rank for each factor. Factors were then sorted by the mean of ranks, with ties shown as ranges. This yielded Ethical Concerns 1st, Task Efficiency 2nd, Facilitating Conditions and Performance Risk joint 3–4, and AI Literacy 5th.

| Factor | TOPSIS score (CCi) | VIKOR_Q (Qi) | TOPSIS rank | VIKOR rank | Sum of ranks | Mean of ranks | Overall rank (range) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethical concerns | 0.784800 | 0.003058 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1.0 | 1 |

| Task efficiency | 0.768537 | 0.054362 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2.0 | 2 |

| Facilitating conditions | 0.728995 | 0.060870 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 3.5 | 3–4 |

| Performance risk | 0.711279 | 0.058501 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 3.5 | 3–4 |

| AI literacy | 0.709651 | 0.078501 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 5.0 | 5 |

| Knowledge acquisition | 0.687898 | 0.127196 | 6 | 7 | 13 | 6.5 | 6–7 |

| Cognitive risk | 0.677829 | 0.110674 | 7 | 6 | 13 | 6.5 | 6–7 |

| Regulatory concerns | 0.632626 | 0.139370 | 10 | 8 | 18 | 9.0 | 8 |

| Social influence | 0.634378 | 0.145457 | 9 | 10 | 19 | 9.5 | 9 |

| Effort expectancy | 0.637399 | 0.163058 | 8 | 12 | 20 | 10.0 | 10–11 |

| Accessibility | 0.615512 | 0.142848 | 11 | 9 | 20 | 10.0 | 10–11 |

| Knowledge sharing | 0.611506 | 0.155892 | 12 | 11 | 23 | 11.5 | 12 |

| Innovativeness | 0.461461 | 0.324587 | 13 | 13 | 26 | 13.0 | 13 |

| Experience | 0.372898 | 0.413283 | 14 | 14 | 28 | 14.0 | 14 |

| Self-Efficacy | 0.357851 | 0.419370 | 15 | 15 | 30 | 15.0 | 15 |

| Job security | 0.321170 | 0.481979 | 16 | 16 | 32 | 16.0 | 16 |

| Hedonic motivation | 0.306065 | 0.504587 | 17 | 17 | 34 | 17.0 | 17 |

Similarly, Fig. 11 shows that TOPSIS and VIKOR ranks largely coincide, with the largest rank divergence at Effort Expectancy. Despite these variations, the Spearman rank correlation coefficient remains high at ρ = 0.963 (about 96.3% agreement), reinforcing the reliability and consistency of the rankings as illustrated in Table 11.

Figure 11: Comparison of TOPSIS and VIKOR rankings for the 17 adoption factors.

| TOPSIS score | VIKOR_Q | Spearman’s rho p-value | |

| −0.963 | <0.001 | ||

A leave-one-expert-out test showed extreme stability. For TOPSIS and VIKOR alike, removing each of the 81 expert columns produced a median Spearman correlation of ρ = 0.998 with the baseline order; the Top-5 factors (Ethical Concerns, Task Efficiency, Facilitating Conditions, Performance Risk, and AI Literacy) remained unchanged in all reruns as illustrated in Table 12.

| Method comparison | Spearman’s rho | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| TOPSIS baseline ↔ Leave-one-out reruns | 0.998 | <0.001 |

| VIKOR baseline ↔ Leave-one-out reruns | 0.998 | <0.001 |

Discussion

The findings mirror broader patterns in academia, where several studies consistently highlight ongoing worries over integrity, bias, privacy, and transparency in GAI use, accompanied by concerns over performance risk (e.g., hallucinated and unreliable content) (Abdelhafiz et al., 2024; Goddard, 2023; Sana’a et al., 2025; Watermeyer et al., 2024). Cognitive risk of researchers’ analytical and problem-solving skills ranked as an important concern resulting from overreliance and heavy use, a pattern consistent with evidence that over-reliance on GAI can impair decision-making, critical and analytical thinking in research settings and may accelerate skill decay in expert problem-solving (Macnamara et al., 2024; Zhai, Wibowo & Li, 2024).

On the benefit side, Task Efficiency ranked second overall, confirming the appeal of automation and enhanced productivity benefits. Several studies reported these task efficiency benefits across different stages of academic research including writing and reporting through improving manuscript drafting and revision quality (Alahdab, 2023), exploration and discovery by literature synthesis and brainstorming (Glazkova, 2021), and data analysis (Zhang, Hu & Zhou, 2025). Knowledge Acquisition emerges as a contributor to adoption. Jo (2024) similarly shows that knowledge acquisition enhances perceived benefits, which in turn significantly strengthens behavioral intention to use GAI tools like ChatGPT.

Contextual and individual factors emerged as an important aspect for adoption. Facilitating Conditions appeared universally across 27 studies and ranked third in MCDM. This aligns with recent findings showing that institutional training, technical support, and clear policy frameworks significantly shape academics’ intention to adopt GAI in higher education (Al-Hattami, 2025). AI literacy was moderately frequent and ranked relatively high (5th) in our MCDM findings; this aligns with empirical work showing that higher AI literacy improves perceived value and lowers perceived risk, thereby increasing adoption intentions in higher-education settings (Al-Abdullatif & Alsubaie, 2024). However, beyond the highest-ranked results, several mid-ranked items show non-trivial importance that may vary indicating context-sensitive effects.

Recent studies view researchers as ambivalent: they see clear benefits in GAI tools yet hesitate to adopt them. In Garcia (2025) study, researchers rated ChatGPT as fitting their writing tasks (mean ≈ 3.65/5) but reported low social normality and discomfort using it (“not normal” for researchers; mean ≈ 1.94/5), and overall intention remained uncertain. Moreover, perceived usefulness and ease of use did not translate into intention in the structural model, whereas trust- and fit-related constructs mattered more, reinforcing a cautious stance. Zhang, Hu & Zhou (2025), reported that perceived utility and social influence do raise researchers’ adoption, but ethical concerns moderate these effects through perceived risk—especially in public universities— so that even valuable tools are kept at a distance when ethical risks become prominent.

This push–pull dynamic where recognition of utility is counterbalanced by ethical and risk concerns produces ambivalence rather than full adoption. However, users seldom remain passive in ambivalent states; instead, they engage in coping responses. Evidence from information systems research shows that flexible coping strategies, such as seeking control and adapting use, predict stronger post-adoptive outcomes (Qahri-Saremi & Turel, 2020). Adoption unfolds as a dynamic process rather than a linear path. In this process, users actively adapt by adjusting features and prompts to restore a sense of control and preserve value (Sun, 2012). GAI adaptability reinforces these coping efforts by strengthening control and trust, which helps resolve ambivalence (Jiang, Yang & Zheng, 2023). However, beyond a point, increased system autonomy can reverse these gains by reducing perceived control and triggering reactance, especially in high-stakes settings.

The perception of GAI shifts further when it is framed as a semi-autonomous collaborator rather than a passive tool (Fatima et al., 2024; Hyunsun, Kevin Kam Fung & Jochen, 2022; Pecher et al., 2024; Rather, 2024). This view of AI as an active social participant increases uncertainty and vulnerability, thereby intensifying risk evaluations. Empirical studies show that greater autonomy in GAI tools reduces adoption intentions because it amplifies complexity, uncertainty, and feelings of losing control (Frank & Otterbring, 2024). Higher autonomy also triggers psychological reactance, leading to cautious, defensive attitudes (Oh, Nah & Yang, 2025) especially in high-stakes fields (Issa, Jaber & Lakkis, 2024). These findings align with Actor-Network Theory and contemporary adaptations of Social Exchange and Net-Valence theories that support the assumption that individuals weigh potential gains against anticipated costs. Researchers prioritized ethical and performance risks over all other factors, confirming a loss-averse stance consistent with SET’s cost–benefit trade-off logic. This suggests that for voluntary GAI adoption by researchers, the perceived costs may carry more weight than marginal efficiency gains, shaping a cautious, calculative adoption process.

Researchers’ strong emphasis on risk evaluation, which mainstream acceptance models usually overlook by focusing mostly on positive adoption drivers, highlights a critical gap. Unlike models such as UTAUT and TAM, which center on performance expectancy and effort expectancy, our findings highlight that risk perceptions, especially ethical and performance risks, rank above functionality. This supports arguments that classic technology acceptance models may underweight deterrent factors, particularly in contexts involving semi-autonomous systems like GAI. The rankings offer grounded input for developing future structural models that explicitly balance enablers and inhibitors. By embedding high-priority costs such as ethical risk into the core of adoption models, researchers can test how these barriers moderate or mediate intention to use GAI tools.

The practical implication of this finding is that institutions should support ethical and effective adoption of GAI by researchers. Through establishing clear guidelines for responsible and ethical use. Researchers must be trained to understand how these tools function. The training should include awareness of potential biases, technical limitations, and appropriate prompt engineering. Institutions could provide specific third-party validation methods, such as independent fact-checking tools, to ensure the accuracy and reliability of AI-generated content. Clear data-security protocols must also be defined, advising researchers on best practices for handling sensitive information, removing identifiers, and securely storing prompts and responses. Additionally, institutions should designate technical support to advise researchers on ethical concerns, accuracy verification, and general troubleshooting related to the use of GAI tools. Institutions should regularly review and update their guidelines to keep pace with technological advances and evolving ethical standards. Continuous monitoring and feedback from researchers can further enhance the effectiveness and relevance of these measures.

Limitations and future research

The generalizability of this study is limited by its convenience sampling approach, potentially introducing sampling bias and restricting the representation of the broader academic researcher population. Although the rankings proved stable under the LOEO jackknife with the current panel size (n = 81), future research using larger, more diverse samples would improve confidence in these findings. Additionally, since the number of studies specifically addressing GAI adoption by researchers remains limited, few studies included here collectively measured adoption by faculty members across varied academic tasks (e.g., teaching, learning, research). This broader scope may dilute the clarity of factors specifically relevant to research-related adoption. Furthermore, other factors that may influence GAI adoption decisions remain underexplored. Given the rapid evolution of GAI tools, further longitudinal research could help clarify how evaluations of risks and benefits shift over time. Additionally, self-reported survey results might not fully reflect actual usage behaviors, indicating a need for research incorporating behavioral measures. In this study, we assumed equal expert weights and used direct ratings rather than pairwise judgments, alternative schemes (AHP/BWM or unequal expert weights) could be examined to test convergence. Despite these limitations, the identified ranked factors provide a solid basis for evaluating influential risks and enablers within established adoption frameworks and assessing their applicability in broader contexts.

Conclusions

This study ranks the key benefits, risks, and contextual and individual influences affecting GAI adoption among researchers. Ethical concerns and accuracy emerged as dominant factors, often outweighing perceived productivity gains. At the same time, GAI delivers concrete task efficiency benefits across research workflows, most notably in manuscript drafting and revision, literature discovery and synthesis, data analysis, and routine administrative tasks thus improving task throughput and freeing time for higher-order analysis. Nonetheless, the analysis highlights that institutional support through clear policies, targeted training, and effective verification mechanisms can significantly encourage responsible GAI adoption. In addition, institutions should not focus solely on the top-ranked factors; mid-ranked factors warrant attention where local context elevates their impact. The findings of this study offer a clear basis for further investigation and for guiding the integration of GAI into academic research workflows.