Semantic-aware framework for zero-shot malware classification via attention-based relation network

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Syed Hassan Shah

- Subject Areas

- Artificial Intelligence, Data Mining and Machine Learning, Data Science, Security and Privacy

- Keywords

- Malware, Zero shot learning, Attention, Relation network

- Copyright

- © 2025 Khan et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2025. Semantic-aware framework for zero-shot malware classification via attention-based relation network. PeerJ Computer Science 11:e3408 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3408

Abstract

Deep neural networks have proven effective in identifying known malware; however, they face challenges when it comes to detecting novel malware that they have not encountered before. This issue arises from their dependence on labeled data for training, which is often scarce for new or uncommon malware types. As a result, creating a model that can detect every possible form of malware becomes impractical. Identifying previously unseen malware is essential, which calls for innovative methods such as Zero-Shot Learning (ZSL). ZSL involves classifying categories that were not present during training. To address this, we propose a novel technique called the Semantic-aware Multi-level Attention-based Relation Network (SMART) for zero-shot malware detection. SMART incorporates Relation-wise Attention (RwA) and Pairwise Semantic Attention (PwA) mechanisms to improve detection accuracy. The PwA component is designed to capture relationships between pairs of input elements, while the RwA mechanism operates at a higher level, analyzing interactions among multiple elements. Our approach outperformed previous methods by significantly reducing false positives and achieving a notable accuracy rate of 95%.

Introduction

Deep learning models have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in various image identification tasks (Tayyab et al., 2022; Gopinath & Sethuraman, 2023). However, these models, which rely on supervised learning, require large amounts of labeled data and many training iterations due to their numerous parameters. This need for extensive data and training limits their scalability to new classes due to the high cost of data annotation (Khan et al., 2023d, 2024a). It also makes it challenging to apply these models to emerging categories, such as new consumer devices or rare animals, where obtaining sufficient annotated images is often impractical. In contrast, humans excel at recognizing objects with minimal or no direct supervision, as seen in few-shot or Zero-Shot Learning (ZSL) scenarios. For example, children can easily understand the concept of a “lion” from just one picture or description. Addressing the limitations of traditional deep learning approaches, which struggle with minimal examples per class, and inspired by human abilities in few-shot and ZSL contexts, there has been growing interest in developing machine learning methods for one-/few-shot and ZSL.

Cyberattacks have emerged as a significant concern in computer networks today. These attacks, ranging from simple viruses to sophisticated malware such as Stuxnet, pose a threat to individual privacy and safety while also endangering the sovereignty of entire nations (Khan et al., 2023b; Ali & Khan, 2013). The relevance of cybersecurity has become paramount, with governments prioritizing its importance. Detecting malicious software, commonly referred to as malware, is a crucial security challenge (Zain et al., 2022). The impact of a single instance of malware can result in millions of dollars in damages. Identifying malware is a complex task due to the spatial correlations & disruptions in branch instructions & function-calling statements found within software codes.

Antivirus solutions are widely used for malware detection. Traditionally, these products use signature-based strategies, in which suspect software undergoes analysis (Azeem et al., 2024; Khan et al., 2019). A distinct signature is produced and uploaded to the antivirus database if the software is determined to be malicious. Unfortunately, malware has devised techniques to evade antivirus and security measures, such as encryption, to disguise their signatures. One of the reasons for misclassification by antivirus systems is their focus on individual malware files rather than considering cross-file information. The constant emergence of new and diverse malware poses challenges in updating antivirus databases (Murali, Thangavel & Velayutham, 2023; Mirza et al., 2014). Malware writers constantly propose novel approaches, making it challenging, if not impossible, to update the database. Consequently, there is a need for novel methods to detect current malware and identify unseen malware. The amount and diversity of known and unidentified malware add to the difficulty of detecting malware (Akhtar & Feng, 2023). Labeling and identifying new malware becomes challenging, especially when numerous samples are available. This work addresses this challenge by proposing a novel method for the detection of malware codes without prior knowledge. Unlike the conventional method of using large amounts of data, few-shot learning uses a few instances from each class to train a model. Although this paradigm presents challenges due to limited training data, it is often encountered in real-world datasets. In few-shot learning, we have a small number of samples, known as k-shot learning, from each class in the training set. ZSL is a learning approach where the training instances do not include all the classes that need to be classified. Using this method, models can classify objects that are not present in the training set. We evaluate the performance of the proposed framework on malware datasets.

A crucial barrier to progress in zero-shot malware detection lies in the inability of past models to adapt to previously unseen threats. This stems from two key limitations: rigid model architectures and insufficient generalization mechanisms. Firstly, earlier methods often employed architectures that lacked the flexibility to handle malware’s diverse and ever-evolving nature. These fixed structures struggled to adapt to novel characteristics and relationships unseen during training, leading to poor performance on new malware variants. Secondly, even flexible architectures might have been hindered by inadequate mechanisms for capturing comprehensive and transferable features. Features too specific to the training data struggle to generalize to unseen examples, rendering the model ineffective against novel threats. This highlights the need for methods that learn features that are both informative and applicable to a broad range of malware, regardless of whether they were encountered during training or not. By addressing these limitations through more adaptable architectures and powerful feature learning techniques, we have paved the way for robust and generalized zero-shot malware detection, ultimately enhancing our ability to combat the ever-growing threat landscape.

Our contribution

-

This study presents an image-based ZSL architecture, addressing the challenge of classifying novel and rare malware instances without prior training samples, specifically targeting the Zero-Shot classification problem in malware datasets.

-

We illustrate the effectiveness of incorporating attention mechanisms alongside the Relation Network (RN) to classify malware families.

-

We propose an architecture that features a pairwise attention module to enhance the representation of local patterns and relation-wise attention to capture broader patterns for input into the relation module.

The structure of this article is outlined as follows: ‘Related Concepts’ describes the background that underpins our work. ‘Related Research Work’ provides an overview of the existing work done in this area. Our proposed work is presented in ‘Proposed Methodology’. ‘Implementation of the Proposed Architecture’ presents the implementation specifics of our proposed methodology, detailing each component. The results of our experiments are outlined in ‘Results and Analysis’, while ‘Conclusion’ outlines the main findings and provides a discussion of future work.

Related concepts

The definitions of the fundamental elements and methods utilized in the proposed architecture are presented in this section.

Portable executables

A Portable Executable (PE) file, as shown in Fig. S1, is commonly used for executables, dynamic link libraries (DLLs), and other executable components in the Windows operating system. PE files are the standard format for executable files and are necessary for running programs on Windows-based systems. They offer resources, data, and program code in an orderly and structured manner. Because they facilitate program execution and resource management, PE files are essential to the Windows operating system.

Zero-Shot Learning

Few-shot or N-shot learning is a technique that trains a model using a small number of samples from each class, rather than a large amount of data. In this case, ‘N’ represents the number of occurrences per class in the training set. Because FSL does not allow for the use of a huge amount of data for training in real datasets, data scientists may view this as an opportunity. N-shot learning is referred to as ZSL, One-Shot Learning (OSL), or few-shot learning, depending on the value of N. ZSL is a learning approach in which training examples do not occur for all classes, resulting in learning modeling without label availability. To make ZSL practical and ensure successful knowledge transfer from visible to unseen classes, a textual description of each class is required for both seen and unseen categories, which is sometimes referred to as side information. An embedding model, which acquires the embedding weights (linking feature space and semantic space) based on viewed class representations and accompanying attributes, is a common pipeline for ZSL.

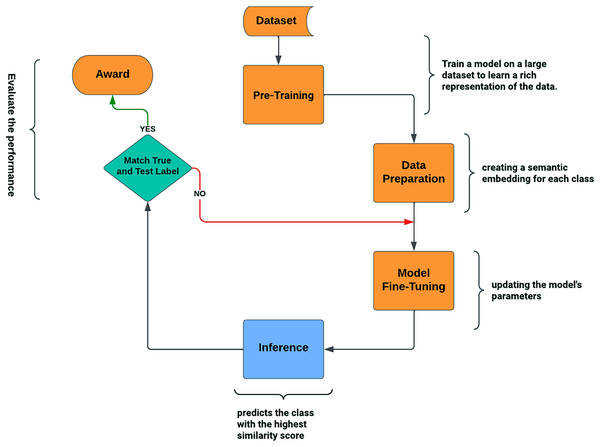

Relation network

By learning to compare query images against few-shot labeled example images, RN accomplishes the few-shot job (Sung et al., 2018). The RN is made up of the feature embedding (FE) and relation modules (RM) (Khan et al., 2023c). The training and query images are represented by the embedding module. Subsequently, the relation module joins and analyzes these embeddings to ascertain whether or not they belong to the same category. For a single query image and the training sample set shown in Fig. 1, the relation module generates relation scores , which range from 0 to 1. In the process of meta-learning, the RN acquires distance measurements that allow it to compare images within each episode and calculate a relation score or similarity score. This configuration mirrors the test environment conditions by simulating many few-shot tasks. An award or positive result is noted if the similarity score approaches 1. An overall score or prediction for the query instance is then produced by adding the awards obtained for each pair of query-support instances. Following episodic training, an RN may reliably recognize images of previously unknown classes by determining the relation scores between test images and the few available samples of each new class, all without requiring additional network updates.

Figure 1: Relation network architecture.

Motivation

Novel malware detection addresses the dynamic and intricate nature of malicious software, which is a critical component of cybersecurity (Khan et al., 2024a). The significance of novel malware detection, illustrated in Fig. S2, lies in its ability to address several critical cybersecurity challenges. As cybercriminals continuously develop new forms of malware to bypass conventional defenses, novel detection techniques are essential for identifying and mitigating these emerging threats (Li et al., 2023). They also play a crucial role in safeguarding against zero-day vulnerabilities—software flaws unknown to developers, leaving systems highly susceptible to exploitation (Thapa, Srivastava & Garg, 2023). Furthermore, advanced persistent threats (APTs), often orchestrated by nation-state actors or organized cybercriminal groups, pose long-term risks through stealthy and adaptive attacks aimed at data theft or disruption. Traditional signature-based defenses fall short against such threats, making artificial intelligence (AI)- and machine-learning-driven approaches vital for identifying behavioral patterns indicative of APT activity (Zhang et al., 2023). Ultimately, novel malware detection supports a proactive security posture by enabling early identification and mitigation of threats before they inflict damage (Gu, Xing & Hou, 2024).

Related research work

In this article, we present a network architecture designed to detect new malware using the Generalized Zero-Shot Learning (GZSL) technique, incorporating a RN. We build upon previous approaches that have utilized RNs to achieve high performance, and our motivation lies in addressing the limitations of those approaches. The following section provides a comprehensive overview of the previous work conducted in this area.

Zero-Shot Learning

ZSL has been applied to diverse challenges such as enhancing image quality, learning unfamiliar concepts, and uncovering unseen semantic relationships (Khan et al., 2024b). In the context of malware detection, ZSL enables the classification of previously unseen malware samples. Traditional detection techniques rely on known patterns or signatures, which struggle to keep pace with the rapidly evolving malware landscape (Torres, Álvarez & Cazorla, 2023). ZSL offers a promising alternative by leveraging semantic embeddings or auxiliary information to generalize detection capabilities beyond labeled training data, allowing recognition of unknown malware classes. For instance, Barros et al. (2022) introduced an S-Space representation to compute similarity between object pairs, while (Rahman, Khan & Porikli, 2019) highlighted a new ZSL challenge involving simultaneous recognition and localization of novel objects in complex scenes. Furthermore, Vyas, Venkateswara & Panchanathan (2020) proposed LsrGAN, a generative approach designed to enhance ZSL learning.

Attention based learning

Prior research has extensively examined attention-based mechanisms for malware analysis. A convolutional neural network (CNN)-based approach combined with attention to identify significant byte sequences in binary-derived images was proposed by Yakura et al. (2018). Similarly, the use of Residual Attention for malware detection was explored in Ganesan et al. (2021), with CNNs proving effective in capturing local spatial correlations and enhancing robustness against polymorphic malware (Khan et al., 2023a; Zain et al., 2022), achieving 99.25% accuracy though not addressing novel malware detection. A multi-headed attention mechanism integrated with a CNN achieved 98% accuracy on the Malimg dataset by highlighting infected image regions (Ravi & Alazab, 2023). Additionally, Zhu et al. (2019) proposed a semantic-guided attention localization model that used semantic representations to identify discriminative object parts.

Relation network

Previous efforts have utilized RNs, but before our work, there has been very little exploration into employing ZSL for malware detection. Khan et al. (2023d) have explored RN with one-shot learning. They applied both five-shot learning and one-shot learning, achieving 94% accuracy with one training instance. Sung et al. (2018) introduced the relation network, which is trained extensively to recognize new classes even with minimal examples per class. They conducted experiments using the Omniglot and miniImagenet datasets. Using One Shot scenario, they achieved an accuracy of 50.44%. Hui et al. (2019) expanded on the notion of RN by introducing a Self-Attention Relation Network (SARN) tailored for few-shot learning. They conducted experiments on various benchmark datasets, including Omniglot, miniImageNet, AwA, and CUB. Bishay, Zoumpourlis & Patras (2019), introduced the Temporal Attention-based Relation Network (TARN) tailored for analyzing video segments to establish relation scores between a query video and other sample videos.

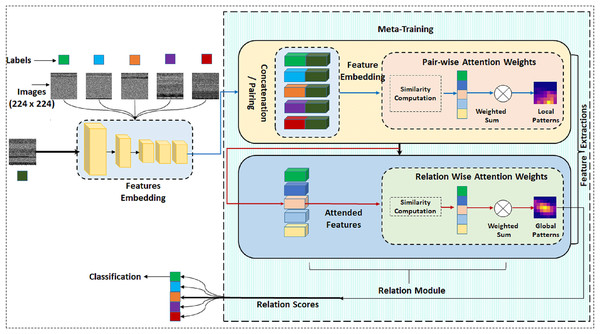

Proposed methodology

This study primarily focuses on the challenge of classifying novel and infrequent instances of malware with no training samples, specifically addressing the scenario known as Zero-shot classification within malware datasets. This research stands out for its exploration of binary classification techniques to differentiate between benign and malicious PE files, an aspect that has been under-explored in the existing literature. We are employing a few-shot learning paradigm based on a similarity metric. In our proposed methodology, attention-based mechanisms are utilized for similarity calculation. Figure 2 gives a full layout of the proposed approach. The attention mechanism is a popular technique that improves translation performance by dynamically selecting important features. We initiate our discussion by introducing specific notations and outlining the problem definition.

Figure 2: Complete architecture of proposed model Semantic-aware Multi-level Attention-based Relation Network (SMART).

Let’s consider a scenario where we have a dataset consisting of N labeled instances, originating from the known classes represented as for training purposes. Here, represents the image, is the corresponding class label, and signifies the semantic representation of the respective class. Now, moving to the core challenge of ZSL, we encounter an image belonging to an entirely new, unseen class. Alongside this image, we possess a set of semantic representations for these unseen classes, denoted as for to , where represents the count of unseen classes. In this context, the primary objective of ZSL is to predict the class label for the given image. It is important to note that and represent two distinct sets of classes with no overlap. Our model architecture is designed to address the challenging task of malware detection, specifically focusing on the detection of novel and previously unseen malware. The architecture combines elements of deep learning and relational reasoning to enable effective ZSL.

Malware visualization

The effective extraction of software features through neural networks necessitates careful consideration of data representation. This ensures the optimal extraction of crucial features and maintains the accuracy of test results. One viable solution involves the utilization of images. Research in the realm of image processing is experiencing a surge in momentum, driven by its promising outcomes across a wide array of applications (Khan et al., 2021). In this approach, the suspected file gets transformed into an image, subsequently processed by the neural network to extract relevant features. The resemblance of file structures is then depicted by the similarity in textures observed in corresponding images. For instance, Nataraj et al. (2011) proposed a malware picture representation scheme wherein the binary code of the malware is transformed into a 2-dimensional matrix. This matrix is represented as a grey-scale graph, given its numerical range [0, 255] as in Fig. S3. The distinctive textures in the data corresponding to different structures become evident through this representation.

Feature embedding module

The model begins with a powerful feature extractor based on ResNet-101, a widely recognized CNN architecture. Residual Networks (ResNets) are known for their exceptional performance in image classification and other computer vision tasks, particularly for very deep networks. ResNet-101, specifically, is a 101-layer deep neural network, making it significantly deeper than earlier models like Visual Geometry Group 16 (VGG-16) or GoogleNet. This feature extractor is pretrained on a large dataset and excels at learning high-level representations from raw data. The standard input size for ResNet-101 is typically 224 × 224 pixels so we provided images of the same dimension. The large number of parameters enables the network to capture complex hierarchical features. Different layers produce feature maps representing the presence of learned features in different spatial locations. These features can be visualized in Figs. S4, S5.

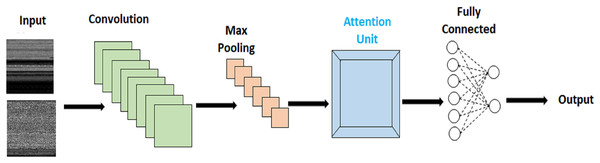

Pairwise attention module

With malware transformed into images, the challenge lies in detecting and pinpointing malware instances that are subtly embedded within the larger image context. Accurate identification and precise localization of these discreetly affected regions are crucial for achieving high malware classification accuracy. To address this, we propose an innovative approach that combines attention mechanisms with CNN. This integrated solution enables us to effectively locate and identify these minuscule infected regions within the broader image context. The implementation of the attention module in our work is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Attention based malware classification.

In our approach, we have incorporated two attention-based modules, each serving distinct functions. Within our proposed methodology, the integration of Pairwise Semantic Attention (PwA) into the extracted features plays a crucial role in refining the representation of local patterns and feature interactions within the dataset. This method involves a focused analysis of pairwise relationships between features, utilizing the PwA mechanism to compute attention scores based on measures of semantic similarity or other relevant metrics. By integrating PwA into the feature analysis, the model gains the ability to emphasize specific feature relationships, thereby improving the overall representation of intricate local patterns and interactions within the data.

The focus on pairwise relationships is essential, and the simplicity of Dot-Product Attention proves to be an efficient method for capturing the essence of these relationships between features in both query and support images. This simplicity not only facilitates a clear understanding of basic similarities and differences but also significantly reduces computational complexity, making it suitable for real-time applications and scenarios involving larger datasets.

Furthermore, the decision to utilize dot-product attention is supported by its sufficiency for initial feature comparison. If the primary goal is to identify fundamental similarities and distinctions between image features, the straightforward nature of dot-product attention is adequate without introducing the additional complexity associated with multiple heads. Figure S6 shows the visualization of attended features maps from first channel.

In the context of our model, we defined the matrix Q as having dimensions (batch_size, query_features) encapsulating the feature representation of the query image. Additionally, we introduce matrix S with dimensions (batch_size, num_support_images, support_features), which encompasses the feature representations of all support images in the dataset.

Then the dot product between the query and each support image feature is calculated

where: ⊤ denotes matrix transpose. We applied softmax to normalize the attention scores:

Use the attention scores to weigh the support features and sum them:

The output of PwA, Z, is a matrix of dimension (batch_size, support_features) representing the refined feature representation of the query image relative to each support image.

Relation wise attention module

Expanding on the pairwise insights obtained through PwA, Relation-wise Attention (RwA) enhances the analysis by modeling higher-level relationships among multiple features across support images. By considering these intricate connections and dependencies, the model captures broader patterns that go beyond individual pairwise comparisons. Therefore, RwA provides a more comprehensive understanding of the relationships between the query image and different malware classes, resulting in more insightful classification, even for new threats. Multi-head attention unlocks RwA’s full potential, with each head detecting distinct aspects of the relationships between the query image and various malware classes present in the support images. With this deeper understanding, the model achieves more accurate classifications, particularly for novel threats, as it can detect subtle patterns that simpler aggregation methods might overlook. Ultimately, multi-head attention enhances RwA’s ability to represent information, transforming it from a mere data compiler into a sophisticated interpreter of the intricate malware ecosystem.

We take H as the matrix of dimension (batch_size, num_support_images, hidden_size) containing the outputs of PwA for each support image. Each row represents the refined feature representation of the query image relative to a specific support image.

RwA individually prepares the query image and each support image by transforming their features into a format suitable for attention.

where:

are learnable weight matrices of dimension (hidden_size, head_dim)

head_dim is the hidden size of each attention head

Then the attention scores are calculated as follows:

(1) where:

softmax normalizes each row of the attention matrix to sum to 1

Then we applied attention weights

(2)

The outputs of all attention heads are concatenated

where:

N is the number of attention heads

; denotes concatenation along the hidden size dimension

In the end, a linear transformation is applied

(3) where:

is a learnable weight matrix of dimension (head_dim N, hidden_size)

By integrating these two components, we attain a comprehensive representation of the query image, encompassing both local pairwise connections and overarching interactions with various malware categories. This contributes to efficient classification, even for unfamiliar classes. Once RwA has captured global representations from the pairwise relationships between the query and support malware images, the ultimate result, , is the classification of the query image into the respective class.

Loss

In our model, we used categorical cross entropy loss. It is used because we are dealing with multi-class classification problems where the output can belong to more than one class. Given a true probability distribution y and a predicted probability distribution p, both representing the probability of each class, the categorical cross-entropy loss is calculated as follows:

(4) where:

y_i is the true probability of class

p_i is the predicted probability of class.

Implementation of the proposed architecture

The proposed framework and all experiments are implemented using PyTorch in Anaconda Spyder 5.3.3.

Dataset and experimental settings

The Malimg dataset comprises 9,339 samples from 25 different malware families, gathered through experiments involving mixtures of network and Windows operating system malware. Notably, the dataset does not include legitimate code samples. Our focus with this dataset is to evaluate the discriminative ability of our model in classifying malware, specifically in identifying the type of malware present. Table 1 provides further information about the Malimg dataset.

| Class | Family | No. of samples |

|---|---|---|

| Dialer | Adialer.C | 125 |

| Dialplatform.B | 177 | |

| Instantaccess | 431 | |

| PWS | Lolyda.AA 1 | 213 |

| Lolyda.AA 2 | 184 | |

| Lolyda.AA 3 | 123 | |

| Lolyda.AT | 159 | |

| Rogue | Fakerean | 381 |

| TDownloader | Dontovo.A | 162 |

| Obfuscator.AD | 142 | |

| Swizzot.gen!I | 132 | |

| Swizzot.gen!E | 128 | |

| Wintrim.BX | 97 | |

| Trojan | Alueron.gen!J | 198 |

| C2Lop.gen!g | 200 | |

| C2Lop.P | 146 | |

| Malex.gen!J | 136 | |

| Skintrim.N | 80 | |

| Worm | Allaple.L | 1,591 |

| Allaple.A | 2,949 | |

| VB.AT | 408 | |

| Yuner.A | 800 | |

| Worm:AutoIT | Autorun.K | 106 |

| Backdoor | Agent.FYI | 116 |

| Rbot!gen | 158 |

MaleVis is designed for vision-based malware recognition research (Jayasudha et al., 2023). It is a corpus involving byte images of 26 (25 + 1) classes. Here, one class represents the cleanware samples while the rest of the 25 classes correspond to different malware types. The MaleVis dataset involves a total of 14,226 images. With this dataset, we can train our model with legitimate code only and evaluate the ZSL classification performance. Table 2 provides detailed information about the MaleVis dataset.

| Class | Family | No. of samples |

|---|---|---|

| Adware | Adposhel | 494 |

| Adware | Amonetize | 497 |

| Adware | BrowseFox | 493 |

| Adware | InstallCore.C | 500 |

| Adware | MultiPlug | 499 |

| Adware | Neoreklami | 500 |

| Backdoor | Androm | 500 |

| Backdoor | Stantinko | 500 |

| Trojan | Agent-fy | 470 |

| Trojan | Dinwod!rfn | 499 |

| Trojan | Elex | 500 |

| Trojan | HackKMS.A | 499 |

| Trojan | Injecto | 495 |

| Trojan | Regrun.A | 485 |

| Trojan | Snarasite.D!tr | 500 |

| Trojan | VBKrypt | 496 |

| Trojan | Vilsel | 496 |

| Virus | Expiro-H | 500 |

| Virus | Hilium.A | 500 |

| Virus | Neshta | 497 |

| Virus | Sality | 499 |

| Worm | Allaple.A | 478 |

| Worm | AutoRun-PU | 496 |

| Worm | Hlux!IK | 500 |

| Worm | Fasong | 500 |

| – | Goodware | 1,832 |

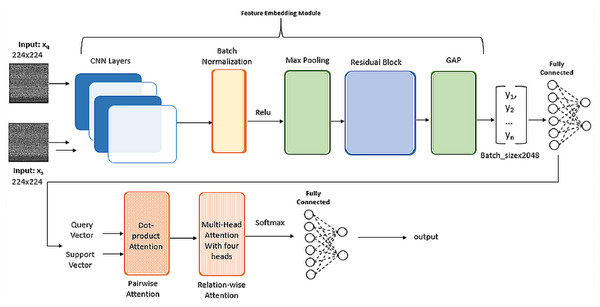

Parameters initialization and network architecture

In the Feature Embedding phase, we leveraged the pre-trained weights from ImageNet for the convolutional layers of ResNet-101 as shown in Fig. 4. Following experimentation, the learning rate was set at a constant value of 0.001. For the PwA component, we employed Kaiming He Initialization for weight initialization. Given that ResNet-101 extensively utilizes ReLU activation functions within its convolutional layers, Kaiming He Initialization was chosen to stabilize gradients through rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation. This choice helped mitigate the risk of vanishing gradients and promotes effective learning. The utilization of Kaiming He Initialization proved instrumental in maintaining a consistent gradient flow, thereby preventing potential training issues.

Figure 4: Implementation details of SMART architecture.

To mitigate computational expenses, we opted for the utilization of four heads in the RwA mechanism. In the final layers, when addressing multi-class classification, we applied the softmax activation function in the output layer to generate probability distributions across classes. The chosen loss function was categorical cross-entropy. It measures the dissimilarity between the predicted probability distribution and the actual distribution of class labels. Minimizing this loss during training helps the model improve its ability to correctly classify instances into their respective classes.

Performance evaluation metrics

In this work, we used performance metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score which play crucial roles in the evaluation of ZSL-based malware detection systems. Accuracy measures the proportion of correctly classified instances among all instances, providing an overall assessment of the model’s effectiveness.

(5) Precision measures the proportion of true positive predictions among all positive predictions, highlighting the model’s ability to avoid false positives.

(6)

Recall, on the other hand, measures the proportion of true positive predictions among all actual positive instances, emphasizing the model’s capability to capture all relevant instances.

(7)

The F1-score, which is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, balances between precision and recall, offering a comprehensive evaluation of the model’s performance.

(8) In ZSL-based malware detection, where unseen malware families need to be detected, these metrics are particularly important as they reflect the model’s ability to generalize to unseen classes while maintaining high accuracy and minimizing false positives. These metrics collectively provide insights into the robustness, generalization ability, and overall performance of ZSL-based malware detection models.

Results and analysis

To evaluate the runtime efficiency of Semantic-aware Multi-level Attention-based Relation Network (SMART), we measured both the image conversion and classification times on a machine equipped with an Intel Core i7 processor and 16 GB RAM. The malware-to-image conversion process took approximately 0.05 s per sample. Once converted, SMART was able to classify a single malware image in around 0.009 s. Regarding training and testing time, SMART was trained using a ResNet-101 backbone with attention mechanisms. The total training time was approximately 2.5 h, and testing took about 5 min on the same hardware. However, we would like to note that exact comparisons with existing models could not be made due to the unavailability of training/testing time details in related works. These results demonstrate that SMART offers efficient processing and is suitable for real-time or near-real-time malware detection on standard computing hardware.

We conducted experiments using the Malimg and MaleVis datasets to evaluate the effectiveness of our proposed model. We conducted two sets of experiments to demonstrate the effectiveness of our method in classifying malware under the zero-shot setting. Initially, we used the Malimg dataset as it does not contain legitimate codes. Our focus, when utilizing this dataset, is to evaluate how discriminating our model is in classifying malware. We partitioned the dataset into three subsets: training, validation, and testing. There are 25 malware families, which we grouped into eight malware classes. Our experimental setup involves conducting ZSL, where all the classes in the testing set are unseen during training. Specifically, we chose three classes (Dialer, PWS, and Rogue) for the training set, two classes (TDownloader and Trojan) for the validation set, and three classes (Worm:AutoIT, Worm, and Backdoor) for the testing set. In ZSL, the model must generalize its knowledge to recognize and classify malware classes it has not encountered during the training phase, simulating a real-world scenario where novel malware types emerge.

We extended our experimental evaluation to the MaleVis dataset, which consists of grayscale images representing 27 different families, including malware and benign samples. To simulate a real-world ZSL scenario, we divided the dataset into three mutually exclusive subsets. Specifically, nine classes were selected for training, nine for validation, and the remaining nine for testing. The training set includes classes such as Adposhel, Amonetize, Agent-fy, Expiro-H, Allaple.A, Androm, HackKMS.A, Snarasite.D!tr, and Neshta. The validation set contains BrowseFox, InstallCore.C, Elex, Regrun.A, Hilium.A, Hlux!IK, Stantinko, Injecto, and VBKrypt. The testing set—comprising unseen malware families as well as Goodware (benign samples)—includes MultiPlug, Neoreklami, Dinwod!rfn, Vilsel, Sality, AutoRun-PU, Fasong, and Goodware. Including benign samples in the test set enables an accurate estimation of the model’s false positive rate and its ability to distinguish malware from legitimate files.

Baselines

Several baseline articles have been considered for comparison: Hui et al. (2019), Bishay, Zoumpourlis & Patras (2019), Verma, Muttoo & Singh (2020), Bozkir et al. (2021), Barros et al. (2022), Xing et al. (2022), Zhu et al. (2019), Huynh & Elhamifar (2020). We categorized all the baseline methods into two primary groups, depending on the features utilized for training. Hui et al. (2019), Bishay, Zoumpourlis & Patras (2019), Zhu et al. (2019), and Huynh & Elhamifar (2020) employ attention based techniques for feature extraction. While Verma, Muttoo & Singh (2020), Bozkir et al. (2021), Barros et al. (2022), Xing et al. (2022) particularly focus on malware classification. Table 3 summarizes the details of all these articles. Each approach is associated with a specific technique and domain. The techniques range from attention-based feature extraction to deep learning methods, while the domains include both non-malware and malware datasets. While our proposed SMART model is evaluated strictly under a ZSL setting, some of the baseline methods (e.g., Hui et al., 2019) were originally evaluated in a non ZSL setting. We include them here to provide a broader performance context. These results are not directly comparable but help highlight that SMART achieves strong results even under the more constrained ZSL evaluation.

| Article | Approach | Technique | Domain |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hui et al. (2019) | SARN | Attention based feature extraction | Non-malware |

| Bishay, Zoumpourlis & Patras (2019) | TARN | Attention based feature extraction | Non-malware |

| Zhu et al. (2019) | Semantic-Guided | Attention + ZSL | Non-malware |

| Huynh & Elhamifar (2020) | DAZLE + self-calibration loss | Attention based GZSL | Non-malware |

| Verma, Muttoo & Singh (2020) | Statistical Methods | Statistical features extraction | Malware |

| Bozkir et al. (2021) | UMAP | Manifold learning + memory forensics | Malware |

| Barros et al. (2022) | Malware-SMELL | Deep metric learning + ZSL | Malware |

| Xing et al. (2022) | Deep learning | Autoencoders | Malware |

The results presented in Table 4 demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed SMART model in detecting previously unseen malware families from the Malimg dataset under the ZSL setting. As outlined in the experimental setup, the model was trained on three malware classes and tested on entirely disjoint classes to simulate real-world conditions where novel threats emerge. The model achieves an average accuracy of 94.83%, with consistently high precision, recall, and F1-scores across all three test classes—Worm:AutoIT, Worm, and Backdoor. Specifically, the model performs best on the Worm class with 96.50% accuracy and an F1-score of 0.96, indicating strong generalization ability. These findings suggest that SMART can effectively learn high-level semantic features from the seen classes and accurately apply this knowledge to classify unseen malware variants. This level of performance validates the model’s robustness and highlights its potential for deployment in security systems where timely detection of novel threats is critical.

| Class | Accuracy (%) | Precision | Recall | F1-score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Worm:AutoIT | 94.20 | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.94 |

| Worm | 96.50 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 0.96 |

| Backdoor | 93.80 | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.93 |

| Average | 94.83 | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.94 |

SMART achieves the highest average accuracy among all other techniques, reaching 95%. Table 5 presents a comparison of performance measures for the zero-shot problem using the MaleVis dataset across existing models and the proposed SMART approach. Overall, SMART demonstrates superior performance across all metrics (Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score). The proposed model exhibits a significant improvement in accuracy compared to existing models, which range from 60.3% to 84%. With an accuracy of 95%, SMART accurately classifies a substantial portion of the samples. Additionally, SMART outperforms all existing models in terms of precision, achieving a score of 0.94. This high precision indicates that a large proportion of samples predicted as positive by SMART are indeed positive. Some models (Verma, Muttoo & Singh, 2020; Huynh & Elhamifar, 2020) show a trade-off between precision and recall, with high precision but lower recall. Surpassing all existing models, SMART achieves a recall of 0.95, effectively identifying a large proportion of actual positive samples in the dataset. Moreover, SMART’s F1-score of 0.947 is the highest among all models, demonstrating an excellent balance between precision and recall. This indicates that SMART achieves both high precision and high recall simultaneously, making it an effective solution for the zero-shot problem in the malware dataset.

| Existing models | Measures | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-score | |

| Hui et al. (2019) | 0.66 | 0.60 | 0.63 | 0.68 |

| Bishay, Zoumpourlis & Patras (2019) | 0.67 | 0.71 | 0.68 | 0.69 |

| Zhu et al. (2019) | 0.70 | 0.69 | 0.66 | 0.68 |

| Huynh & Elhamifar (2020) | 0.60 | 0.79 | 0.71 | 0.69 |

| Verma, Muttoo & Singh (2020) | 0.72 | 0.71 | 0.69 | 0.73 |

| Bozkir et al. (2021) | 0.88 | 0.82 | 0.79 | 0.84 |

| Barros et al. (2022) | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.80 | 0.81 |

| Xing et al. (2022) | 0.76 | 0.72 | 0.73 | 0.69 |

| SMART | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.94 |

Note:

The statistics for the proposed model are shown in bold.

Performance across different datasets

We utilized the Malimg and MaleVis datasets to assess the performance of our model. For our testing scenario, we employed three classes from the Malimg dataset, encompassing seven families. The experiments were conducted using all instances per class. However, for visualization purposes, we presented a confusion matrix using a stratified subset of approximately 100 samples per class. This was done to maintain visual clarity and balance across classes, especially considering the significant class imbalance in the original dataset (e.g., Allaple.A with 2,949 samples vs. Autorun.K with only 106). This does not affect the reported performance metrics, which are computed over the full test set.

The findings, as illustrated in Fig. S7, revealed a notably low false positive rate across all families. Specifically, for Allaple.L, the accuracy reached its peak.

The evaluation of SMART for malware classification for the MaleVis dataset gave insightful results across various performance metrics as shown in Fig. S8. The average accuracy of the model was calculated to be 95%, showcasing its ability to classify instances across all classes correctly. Precision, which measures the accuracy of positive predictions, varied across different classes, with some classes exhibiting higher precision due to lower false positive rates, as shown in Table 6. For instance, Adposhel, Hilium.A and Goodware demonstrated a particularly high precision, indicating the model’s proficiency in accurately identifying instances of this class. Additionally, recall, highlighting the model’s ability to identify all positive instances, varied across classes, with certain classes displaying higher recall values than others. Notably, Neoreklami, Elex, Injecto, and Regrun exhibited exceptional recall, underscoring the model’s effectiveness in capturing all instances of this class. F1-scores, which provide a balanced assessment of precision and recall, ranged from 0.83 to 1.00, emphasizing the trade-off between precision and recall in classification performance. The confusion matrix heatmap visually depicts the distribution of true positives, false positives, true negatives, and false negatives, offering further insights into the model’s classification performance for each class. Overall, these results provide a comprehensive understanding of the model’s strengths and weaknesses, facilitating informed decisions for model refinement and optimization.

| Malware | SMART | UMAP | Statistical | DNN | Malware-SMELL | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family | ACC | PREC | REC | F1-score | ACC | PREC | REC | F1-score | ACC | PREC | REC | F1-score | ACC | PREC | REC | F1-score | ACC | PREC | REC | F1-score |

| Adposhel | 0.90 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 0.95 | 0.61 | 0.64 | 0.65 | 0.61 | 0.55 | 0.61 | 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.85 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.99 |

| Amonetize | 0.98 | 0.86 | 0.98 | 0.93 | 0.52 | 0.66 | 0.62 | 0.51 | 0.49 | 0.56 | 0.59 | 0.51 | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.94 |

| BrowseFox | 0.84 | 0.88 | 0.84 | 0.86 | 0.64 | 0.58 | 0.54 | 0.53 | 0.54 | 0.52 | 0.57 | 0.53 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.80 | 0.86 | 0.94 | 0.89 | 0.81 | 0.91 |

| InstallCore.C | 1.00 | 0.91 | 1.00 | 0.95 | 0.47 | 0.70 | 0.59 | 0.64 | 0.55 | 0.53 | 0.52 | 0.50 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.97 |

| MultiPlug | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.50 | 0.63 | 0.59 | 0.49 | 0.61 | 0.67 | 0.57 | 0.41 | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.90 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.93 |

| Neoreklami | 1.00 | 0.86 | 1.00 | 0.92 | 0.65 | 0.32 | 0.50 | 0.39 | 0.49 | 0.42 | 0.53 | 0.47 | 0.67 | 0.61 | 0.59 | 0.60 | 0.89 | 0.87 | 0.85 | 0.96 |

| Androm | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.46 | 0.34 | 0.38 | 0.35 | 0.53 | 0.39 | 0.43 | 0.41 | 0.85 | 0.83 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.83 | 0.81 | 0.78 | 0.85 |

| Stantinko | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.63 | 0.64 | 0.65 | 0.62 | 0.61 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.59 | 0.86 | 0.89 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.94 |

| Agent-fy | 0.88 | 0.89 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.45 | 0.61 | 0.56 | 0.43 | 0.51 | 0.57 | 0.52 | 0.55 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.83 | 0.80 | 0.81 | 0.87 |

| Dinwod!rfn | 0.94 | 0.91 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.48 | 0.53 | 0.53 | 0.48 | 0.51 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.87 | 0.91 | 0.97 | 0.94 | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.92 |

| Elex | 1.00 | 0.86 | 1.00 | 0.92 | 0.52 | 0.71 | 0.63 | 0.51 | 0.53 | 0.66 | 0.47 | 0.60 | 0.61 | 0.69 | 0.67 | 0.68 | 0.89 | 0.94 | 0.96 | 0.93 |

| HackKMS.A | 0.80 | 0.90 | 0.80 | 0.95 | 0.86 | 0.85 | 0.88 | 0.86 | 0.81 | 0.74 | 0.76 | 0.70 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.94 | 0.91 | 0.98 |

| Injecto | 1.00 | 0.95 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.80 | 0.78 | 0.76 | 0.77 | 0.76 | 0.71 | 0.72 | 0.63 | 0.96 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.83 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 0.85 |

| Regrun.A | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.75 | 0.79 | 0.81 | 0.75 | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.83 | 0.69 | 0.86 | 0.89 | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.98 |

| Snarasite.D!tr | 0.96 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.51 | 0.71 | 0.62 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.64 | 0.66 | 0.59 | 0.89 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 1.00 |

| VBKrypt | 1.00 | 0.95 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 0.66 | 0.60 | 0.58 | 0.58 | 0.68 | 0.53 | 0.51 | 0.51 | 0.84 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.93 |

| Vilsel | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 1.00 |

| Expiro-H | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.46 | 0.64 | 0.57 | 0.43 | 0.49 | 0.60 | 0.61 | 0.59 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.70 | 0.81 | 0.73 | 0.78 |

| Hilium.A | 0.92 | 1.00 | 0.92 | 0.95 | 0.78 | 0.81 | 0.83 | 0.78 | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.90 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 1.00 |

| Neshta | 1.00 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.63 | 0.56 | 0.54 | 0.53 | 0.63 | 0.61 | 0.51 | 0.47 | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.60 | 0.59 | 0.57 | 0.71 |

| Sality | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.53 | 0.55 | 0.56 | 0.52 | 0.59 | 0.53 | 0.59 | 0.54 | 0.78 | 0.87 | 0.73 | 0.80 | 0.83 | 0.84 | 0.75 | 0.80 |

| Allaple.A | 0.84 | 0.99 | 0.84 | 0.90 | 0.69 | 0.64 | 0.61 | 0.62 | 0.60 | 0.67 | 0.59 | 0.63 | 0.89 | 0.90 | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.90 |

| Autorun-PU | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.68 | 0.66 | 0.59 | 0.58 | 0.61 | 0.60 | 0.62 | 0.57 | 0.76 | 0.78 | 0.76 | 0.77 | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.78 | 0.86 |

| Hlux!IK | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.65 | 0.74 | 0.73 | 0.65 | 0.62 | 0.68 | 0.69 | 0.65 | 0.81 | 0.85 | 0.79 | 0.83 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.99 |

| Fasong | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.59 | 0.73 | 0.68 | 0.59 | 0.51 | 0.74 | 0.71 | 0.67 | 0.87 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Goodware | 0.95 | 1.00 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 0.59 | 0.73 | 0.68 | 0.59 | 0.51 | 0.74 | 0.71 | 0.67 | 0.87 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| All family | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.73 | 0.69 | 0.66 | 0.68 | 0.70 | 0.67 | 0.65 | 0.66 | 0.75 | 0.76 | 0.72 | 0.74 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.73 | 0.84 |

Table 6 presents a comprehensive overview of performance metrics for all classes within the MaleVis dataset across various malware detection models: Proposed SMART, UMAP, Statistical, DNN, and Malware-SMELL. SMART was evaluated under a ZSL setup, where testing classes were unseen during training. In contrast, the baseline models (UMAP, Statistical, DNN, and Malware-SMELL) were trained and tested using supervised learning setups. This comparison highlights SMART’s strong performance under the more challenging ZSL scenario. We included these baselines to demonstrate that even under the more challenging ZSL scenario, SMART outperforms traditional supervised models on unseen malware classes, underscoring its superior generalization capability. Analyzing the performance of the proposed SMART model, we observed notable variations in detection efficacy across different malware families. For instance, the Adposhel family achieves a commendable accuracy of 0.90 under SMART, indicating strong classification. Conversely, some families, such as Neoreklami, exhibit lower accuracy in baseline methods, underscoring SMART’s improved capability to accurately identify instances from these challenging classes.

A closer examination reveals that certain malware families consistently demonstrate strong performance across multiple metrics within the SMART model. For example, the Vilsel family consistently maintains high accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score values, suggesting that the SMART model effectively detects instances belonging to this family.

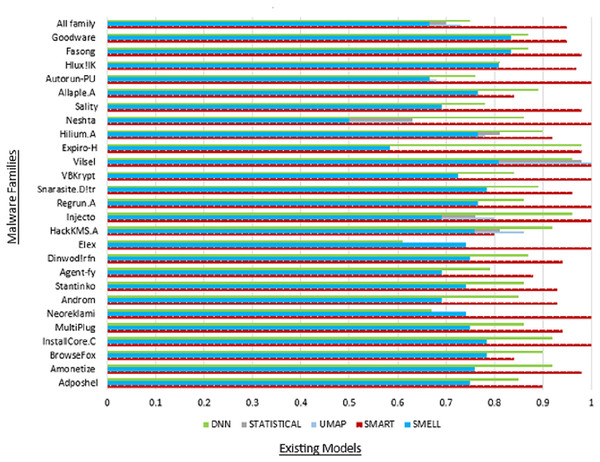

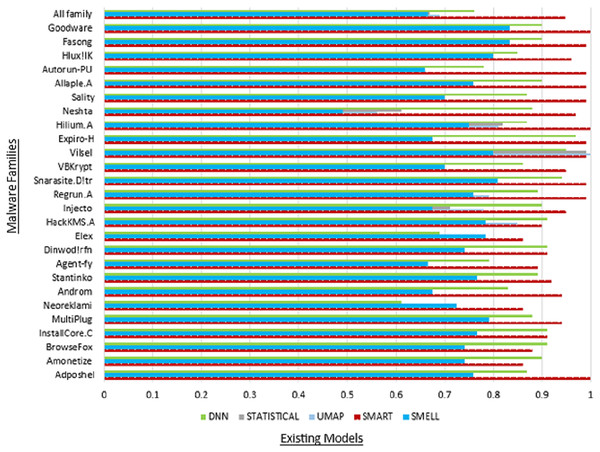

Moreover, the “All family” row provides an aggregate summary of the SMART model’s overall performance across all malware families, offering insights into its collective effectiveness in detecting malware within the MaleVis dataset. This summary facilitates a comprehensive evaluation of the SMART model’s robustness and reliability in real-world malware detection scenarios. Figure 5 illustrates the commendable accuracy achieved by our model, while Fig. 6 demonstrates the favorable precision of our model compared to other models.

Figure 5: Comparison of accuracy with existing models.

Figure 6: Comparison of precision with existing models.

Conclusion

In this work, we have proposed a novel method known as the Semantic-aware Multi-level Attention-based Relation Network (SMART) designed specifically for zero-shot detection of emerging malware. SMART incorporates two distinct attention mechanisms: relation-wise (RwA) and pairwise semantic attention (PwA), aiming to elevate detection efficacy. The PwA module is dedicated to capturing inter-object relationships within the input, whereas the RwA operates on a broader scale, analyzing the overarching relations or interactions among multiple objects or elements in the input. Our method has exceeded previous research by notably minimizing false positives and achieving elevated levels of accuracy. More precisely, we achieved an impressive accuracy rate of 95%. Currently, our proposed approach emerges as the preferred approach for ZSL methodologies. In our future research endeavors, we aim to conduct additional refinement and optimization of the SMART framework, to achieve even more substantial performance enhancements.