Deep learning model for Chinese watercolor painting creation

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Trang Do

- Subject Areas

- Artificial Intelligence, Computer Vision, Data Science, Multimedia, Visual Analytics

- Keywords

- Chinese watercolor painting, Generative adversarial networks, Hierarchical multi-scale generation, Art synthesis, Cultural heritage preservation

- Copyright

- © 2025 Qi

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2025. Deep learning model for Chinese watercolor painting creation. PeerJ Computer Science 11:e3404 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3404

Abstract

Chinese watercolor painting, celebrated for its delicate brushwork, smooth tonal gradients, and expressive ink diffusion, embodies a rich historical and cultural heritage. This article introduces a hierarchical multi-scale generative framework for producing high-quality traditional watercolor paintings. The model is trained on a curated collection of high-resolution artworks from public museum archives and employs a pyramid of patch-based generative adversarial networks (GANs), each dedicated to learning visual features at a specific spatial scale. Residual learning across scales enables progressive refinement from coarse composition to intricate brushstroke details. Quantitative evaluation using Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) and Diversity Score shows significant performance gains over other well-known GAN-based models. Qualitative results further demonstrate the framework’s ability to emulate the stylistic nuances of classical Chinese art, capturing brushwork precision, ink diffusion effects, and compositional harmony, while preserving both global structure and local texture.

Background

Chinese watercolor painting is a rich confluence of artistic expression, aesthetic value, and deep cultural significance, representing a unique blend of traditional Chinese aesthetics. Its aesthetic foundation is rooted in traditional philosophies such as Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism, which collectively emphasize the harmonious relationship between nature and humanity. According to Bao et al. (2016), Chinese aesthetic principles prioritize dialogue with nature, where natural landscapes are not merely representations but reflections of deeper existential truths, especially influenced by Taoist ideals of unity with the cosmos. This cultural context gives Chinese watercolor painting a distinct moral and philosophical character, often inspiring contemplation and virtue in the viewer (Peng, 2023).

The application of watercolor painting extends beyond aesthetic value, encompassing rich cultural narratives and significant regional characteristics. Wang (2022) demonstrates that different natural environments, including mountains, rivers, and vegetation across various regions, shape both the style and thematic content of watercolor paintings throughout China. This regional personalization not only enriches the artistic narrative but also reinforces the cultural and ecological value of the depicted landscapes, ultimately fostering a stronger connection between the artwork and the viewer’s contextual experience. In educating future artists, Chinese institutions increasingly emphasize the integration of both traditional techniques and modern approaches. This ensures that learners both respect tradition and innovate within this unique artistic framework (Wu, 2023). The importance of education in maintaining the contemporary relevance of Chinese watercolor painting is highlighted by the growing interest in linking artistic practice with current social and cultural issues, allowing the art form to evolve while remaining culturally grounded.

Automation in artistic creation can incorporate a variety of technologies, including machine learning algorithms that can analyze and replicate stylistic elements found in classical paintings. According to Bao et al. (2016), automated systems can be programmed to understand various artistic styles and techniques such as brushwork, color blending, and compositional balance, all of which are essential in Chinese watercolor painting. These systems use large datasets of traditional artworks to learn and generate new works that reflect traditional styles while allowing for new interpretations. Automated painting can foster unprecedented creativity by offering artists tools that enhance both conceptual and technical capabilities. For instance, generative software allows artists to input specific variables such as theme, color palette, or emotional tone to produce numerous watercolor variations (Peng, 2023). As noted by Wang (2017), artists using these tools engage in a collaborative process with technology. Their role becomes more curatorial, enhancing rather than replacing the creative process. Moreover, automated systems can assist in exploring compositions that would otherwise require significant effort or advanced technical skills. These capabilities support experimentation with hybrid styles, combining traditional Chinese aesthetics with contemporary or foreign influences and contributing to the evolving narrative of this art form.

Preserving cultural heritage in the context of automation involves multiple dimensions. Firstly, technology can be used to digitize and archive traditional techniques and artworks. High-resolution scanning technology can capture and preserve intricate details of brushstrokes and color blending that are fundamental to watercolor painting (Chen, 2023). Furthermore, automated systems can support the teaching and transmission of these techniques to emerging artists through interactive platforms that simulate traditional methods and allow for practice without the immediate need for physical materials. Additionally, using automation to adapt classical techniques into modern hybrid formats can attract new attention to traditional painting while maintaining its relevance in contemporary culture (Wang, 2022). By increasing access to traditional artistic methods, tools, and philosophies, automated systems can play an essential role in renewing interest in cultural practices and fostering appreciation among younger generations and international audiences.

Chinese watercolor painting, with its deep historical and cultural significance, is characterized by delicate brushstrokes, smooth transitions of color, and the unique visual effect of ink diffusion. These qualities make the automation of this art form particularly complex. This article outlines the challenges posed by the unique stylistic features of Chinese watercolor and identifies the necessary elements that must be addressed for automation to effectively replicate or expand this culturally rich medium. The expressive brushwork typical of Chinese watercolor requires a high level of skill and intuition from the artist. In contrast to Western watercolor techniques, which emphasize precision and defined shapes, the Chinese approach often values spontaneity and the dynamic interaction between the artist and the materials. This immersive quality produces a narrative depth that automated systems struggle to replicate due to their limited ability to understand artistic context and intention. Incorporating this spontaneity into automated painting requires not only advanced algorithmic techniques but also an understanding of the cultural and philosophical underpinnings of artistic choices, which are often highly subjective. The materials and visual effects involved in Chinese watercolor painting also present significant obstacles for automation. Traditional techniques rely on precise manipulation of water and ink to create visual effects that machines cannot easily reproduce. The subtle behavior of diluted pigments and the varying absorbency of different types of article introduce many unpredictable variables in achieving the desired outcome. Developing algorithms capable of simulating these materials and their interactions is a complex task. Automated tools must model the physical properties of ink on article accurately, including viscosity, drying time, and texture changes caused by blending and pigment dispersion. This demands both sophisticated programming and extensive datasets of brushstroke simulations and texture patterns derived from traditional artworks.

One of the defining features of Chinese watercolor painting is the phenomenon of ink diffusion and spreading, achieved through the artist’s careful control of water and pigment. This effect is dynamic and responsive to the artist’s movements and decisions, emphasizing the unpredictability of ink behavior on article (Wang, 2022). Automation struggles to replicate such natural processes, as the algorithms need to respond in real-time to nonlinear factors such as moisture, temperature, and the pressure exerted by the artist. Although artificial intelligence (AI) technology is progressing in this domain, it is still not capable of authentically reproducing the flexibility and complexity inherent in traditional methods (Wu, 2023). The current level of algorithmic understanding of these nuances is limited, suggesting that further innovation is needed in machine learning and fluid dynamics modeling for automated systems.

Related work

Generative adversarial networks (GANs) (Goodfellow et al., 2014) have revolutionized various artistic fields by establishing a framework wherein a generator and a discriminator are set in a competitive game to produce high-quality output. The generator aims to create images that are indistinguishable from real images, while the discriminator attempts to correctly classify these images as real or fake. This minimax game is structured around a specific loss function that encourages both parties to improve continuously (Sizyakin et al., 2020). Various artistic applications of GANs have emerged, ranging from image generation to artistic style transfer (Song & Xu, 2023). Notably, CycleGAN models have been applied extensively for image-to-image translation tasks, including sketches to paintings (Lu, Guo & Wang, 2024). These networks excel in synthesizing art styles, showcasing the versatility and effectiveness of GAN architectures in creative domains by capturing the distinct features of traditional art forms (Fu et al., 2020).

Neural Style Transfer plays a critical role in merging content and style from different images. The Pix2Pix architecture has been utilized for translating sketches into paintings, enabling high-fidelity results through learning from paired datasets (Chen, 2023). Additionally, advancements like Pix2PixHD have heightened the precision of image translations, achieving resolutions up to 1,024 × 1,024 pixels and enabling photorealistic representations in artistic contexts (Scalera et al., 2022). The methods for generating Chinese watercolor paintings particularly benefit from these advancements, integrating techniques that merge traditional art with computational approaches (Cheng, Wang & Wang, 2024). Research exploring sketch-to-paint translation leverages GANs and conditional inputs to produce detailed renditions, mimicking the unique elements of Chinese artistic heritage (Lu, Guo & Wang, 2024).

Beside GAN-based models and Neural Style Transfer techniques, recent research on the application of diffusion models in Chinese watercolor painting has demonstrated great potential for enhancing artistic expression through computational techniques. For example, Jia (2024) highlights the ability of these models to generate high-quality visual content, which is a crucial factor in the aesthetics characteristic of traditional Chinese art. These models not only support image synthesis from textual descriptions but also enable style transfer, imitating traditional painting techniques that are fundamental to watercolor art (Li, 2023). Researchers have further explored how the principles of traditional Chinese ink painting can be integrated into watercolor painting techniques using diffusion models. This approach not only enriches the aesthetic value but also preserves the cultural narratives embedded in the original forms (Chen, 2023). The potential to produce artworks that embody both historical significance and contemporary innovation exemplifies a bridge between traditional artistry and modern technological capabilities (Wang et al., 2024b).

Recent studies propose various methodologies to enhance the watercolor generation process using advanced machine learning techniques. The integration of AI technologies has made significant strides, as demonstrated by robotic painting systems that utilize contour-filling algorithms for watercolor techniques (Scalera et al., 2022). Furthermore, research by Fu et al. (2020) explored multi-style generation of Chinese artwork, emphasizing the importance of employing generative models to capture the diverse aesthetics prevalent in traditional Chinese watercolor paintings. These innovations signify the continual blending of technology and traditional artistry, paving the way for new creative avenues within watercolor art. The intersection of artificial intelligence and artistic expression within traditional art forms raises critical questions about cultural identity and aesthetic preferences. Studies have shown that different cultural backgrounds significantly influence aesthetic experiences when engaging with various art forms, impacting how art generated through AI is perceived (Bao et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2024b). This underscores the necessity for deeper cultural understanding when designing AI models for art generation, ensuring that the essence of traditional styles is maintained and respected in AI-generated artworks. The application of techniques such as deep learning has not only improved the visual quality of generated artworks but also resonates with cultural aesthetics, illustrating a balance between modern technology and cultural heritage in the creation of Chinese watercolor paintings (Wang et al., 2024b).

Although studies related to GANs and Neural Style Transfer have achieved remarkable success in generating artistic images and performing style transfer, most of these approaches remain heavily dependent on the availability of large-scale datasets. This poses particular challenges when applied to art forms such as Chinese watercolor painting, where data is often scarce. This artistic style requires subtlety in capturing complex hierarchical structures and unique aesthetic characteristics, such as the interplay of multiple compositional layers including background, mist, and fine brushstrokes. While GAN-based methods can be effective in reproducing artistic forms, capturing the intangible aesthetic elements of watercolor painting remains a major challenge. In this context, research on diffusion models has opened a promising direction, demonstrating potential in improving image quality and replicating artistic styles. However, current studies still fall short in addressing the preservation of cultural authenticity in Chinese watercolor painting. The capacity of these models has not yet been fully explored to balance technical requirements with the safeguarding of aesthetic identity and cultural depth inherent in this traditional art form. Therefore, there remains a significant research gap in developing methods that can simultaneously satisfy the quantitative demands of machine learning models while respecting all aspects of Chinese watercolor painting. Advancing such approaches is essential to create artworks that are not only visually compelling but also deeply rooted in cultural value.

Proposed framework

Model selection rationale

In the domain of traditional Chinese watercolor painting synthesis, one of the fundamental challenges lies in the scarcity of high-quality data. Existing collections are often scattered across multiple museums or private archives, difficult to access, and rarely digitized in their entirety. This makes it nearly impossible to construct a large-scale, stylistically diverse training dataset suitable for conventional image generation models, which typically require thousands of samples to achieve satisfactory performance. Consequently, there is a pressing need for an approach capable of learning effectively from a single or very limited number of input images, leveraging the intrinsic information contained within the image itself.

A suitable solution is to employ hierarchical multi-scale generative models organized in a pyramid-like resolution structure. In such architectures, image features are learned progressively from low to high resolutions, enabling the model to capture both the global composition and fine-grained details. Sequential training, combined with freezing the weights at each level after completion, provides precise control over the level of detail generated, reduces the risk of overfitting, and prevents the introduction of undesired artifacts.

This approach is particularly well-suited for watercolor painting, which inherently exhibits a clear hierarchical composition: broad background landscapes, intermediate layers of mist, and intricate brushwork in the foreground. Each of these layers contains critical visual characteristics that must be faithfully reconstructed at the corresponding resolution level. Furthermore, the use of compact convolutional blocks (Conv–BN–LeakyReLU) effectively models the natural diffusion patterns of watercolor pigments and the fluidity of brushstrokes—two essential aesthetic properties of the art form.

By combining the ability to learn from minimal data, a hierarchical feature-learning mechanism, and fine-grained control over detail generation, multi-scale generative architectures not only address the problem of data scarcity but also preserve the authenticity of both the structural composition and the distinctive artistic texture of traditional Chinese watercolor painting. This enables the creation of novel variations while maintaining the artistic integrity and stylistic essence of the original medium.

Method

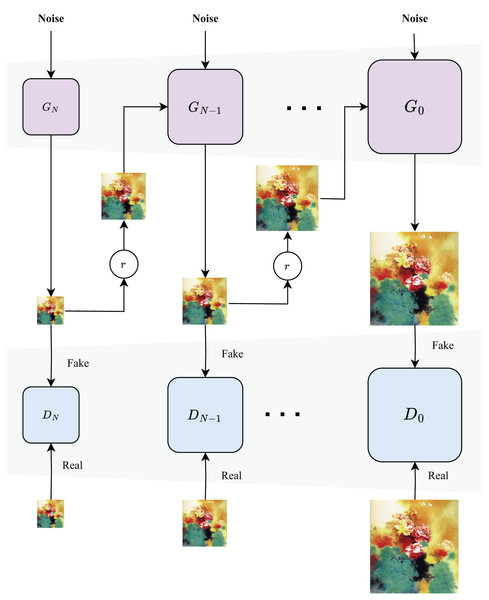

In this article, we develop an unconditional generative model capable of synthesizing high-quality Chinese watercolor paintings from a single input image, as illustrated in Fig. 1. Unlike conventional GANs (Goodfellow et al., 2014) trained on large-scale datasets, our model learns the internal patch-level statistics of a single image. This allows it to capture both the global compositional layout and the fine-grained brushstroke textures typical of traditional Chinese ink and watercolor paintings. Inspired by hierarchical generative architectures, we propose a multi-scale patch-based GAN framework, wherein a pyramid of GANs learns to model spatial structures at progressively finer resolutions.

Figure 1: Overview of the proposed hierarchical multi-scale generative model.

Let denote the input painting. We construct an image pyramid , where represents the input image downsampled by a factor of . At each scale , a generator and a discriminator are instantiated. While aims to replicate the patch statistics of , learns to distinguish real from synthesized patches at that scale.

Hierarchical generation process

The image synthesis begins at the coarsest level N, where the generator receives a Gaussian noise map and produces a low-resolution image:

(1)

Subsequent generators for refine the image iteratively by incorporating newly sampled noise and the upsampled output from the previous scale :

(2)

Each generator performs residual learning via a fully convolutional sub-network , resulting in:

(3)

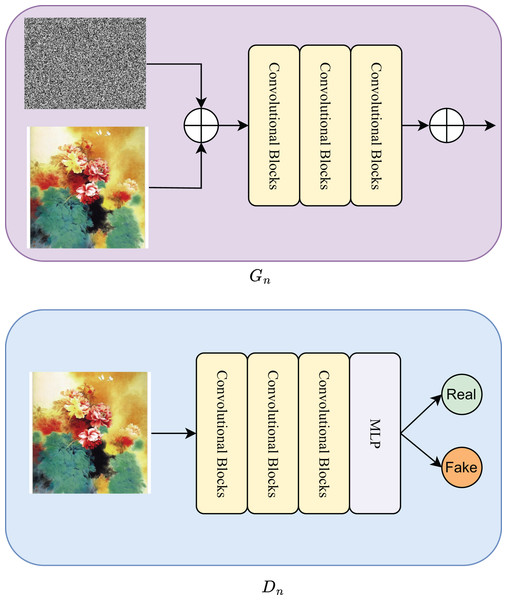

The sub-network consists of three convolutional blocks, each following the Conv(3 × 3)–BatchNorm–LeakyReLU sequence (Fig. 2). This design provides sufficient capacity to model the intricate ink diffusion patterns characteristic of Chinese watercolor.

Figure 2: Internal architecture of each generator and discriminator .

Training objective function

Training is conducted sequentially from the coarsest to the finest scale. Once a GAN at scale is trained, its weights are frozen before proceeding to scale . The objective function at each scale incorporates both an adversarial loss and a reconstruction loss:

(4)

Adversarial loss: To ensure stable convergence, we adopt the Wasserstein GAN with Gradient Penalty (WGAN-GP) (Gulrajani et al., 2017). Each discriminator is applied in a fashion over local image patches. The overall realism score is computed by averaging patch-level outputs, promoting consistent global structure and eliminating discontinuities in ink textures.

Reconstruction loss: To guarantee the generative pathway preserves content, we incorporate a scale-aware reconstruction loss. During training, a fixed noise vector is sampled at the coarsest level N, and zero noise is used for finer levels. The reconstruction loss is defined as:

(5) Moreover, the standard deviation of the input noise is dynamically adjusted based on the root mean square error (RMSE) between and . This adaptation regulates the detail level generated at each scale, balancing noise injection and structural fidelity.

Dataset

In order to train generative models specifically tailored to the aesthetic and structural characteristics of traditional Chinese watercolor paintings, particularly in the style, we use a high-quality dataset consisting exclusively of traditional Chinese watercolor paintings (Xue, 2020), sourced from reputable open-access digital museum collections. Specifically, this dataset gather works from the following institutions:

Smithsonian Freer Gallery of Art

Harvard Art Museums

Princeton University Art Museum

Metropolitan Museum of Art

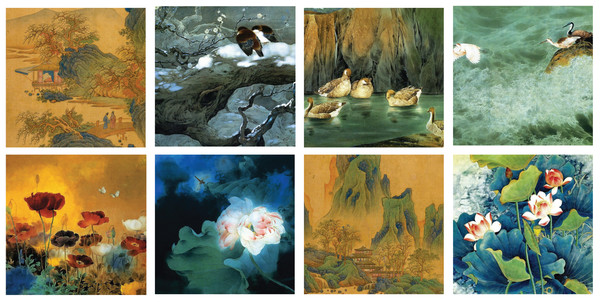

In addition, we further collected supplementary Chinese watercolor paintings from publicly available internet resources to enrich the dataset and increase the diversity of image content. A representative sample of the collected paintings is shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Representative samples from the dataset of traditional Chinese watercolor paintings.

To ensure reliable evaluation of the proposed model, the dataset comprising 2,232 images collected from four museum sources was divided into training and testing subsets using an 80/20 ratio. Specifically, 1,784 images were allocated for training, while the remaining 448 images were reserved for testing as described in Table 1. The distribution was performed proportionally for each source (Smithsonian, Harvard, Princeton, Metropolitan and Internet) to preserve the original class balance and avoid introducing sampling bias.

| Source | Total | Train (80%) | Test (20%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smithsonian | 1,301 | 1,041 | 260 |

| Harvard | 101 | 81 | 20 |

| Princeton | 362 | 290 | 72 |

| Metropolitan | 428 | 342 | 86 |

| Internet (self-collected) | 40 | 30 | 10 |

| Total | 2,232 | 1,784 | 448 |

Data cleaning and preprocessing

The dataset is curated to ensure semantic consistency and suitability for training generative models in the traditional Chinese watercolor painting domain. Non-landscape artworks, including portraits, calligraphic works, and abstract compositions, are excluded. Additionally, distracting visual components—such as silk borders, seals, or textual annotations—are removed wherever applicable. To standardize image format and resolution for model training, each painting in the dataset undergoes the following preprocessing steps:

Images are aligned to a consistent vertical orientation.

Each image is resized such that its width is fixed at 256 pixels, while preserving the original aspect ratio.

If the height-to-width ratio exceeds 1.5, the image is partitioned into non-overlapping vertical patches of size .

For images with a height-to-width ratio , a single center crop is extracted.

Patches are then rotated back to match the original orientation if necessary.

To supplement structural information beneficial for learning, each image patch is paired with a corresponding edge map generated using Holistically-Nested Edge Detection (HED) (Xie & Tu, 2015). The HED model, based on fully convolutional neural networks, captures both low-level details and high-level contours by aggregating features at multiple scales. Compared to traditional methods such as Canny edge detection, HED better preserves semantic coherence and the brushstroke continuity critical to ink-based artworks. Each image sample in the dataset is thus represented as a two-channel input tensor comprising a RGB image and its associated HED edge map, facilitating tasks that benefit from explicit structure encoding.

The final dataset contains 2,232 high-resolution traditional Chinese watercolor paintings, each standardized to resolution and augmented with an edge map. This curated collection offers a clean, semantically focused resource for training and evaluating deep generative models, with potential applications in cultural preservation, artistic synthesis, and data-efficient creative AI systems.

Experiments

Implementation and computational infrastructure

All experiments were conducted on a workstation equipped with an Intel Core i7-12900K processor, 32 GB RAM, and an NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPU. The operating system used was Ubuntu 20.04 LTS. The software environment included Python 3.8 and PyTorch 2.1.0 as the primary deep learning framework. GPU acceleration was enabled using CUDA Toolkit. All training and evaluation procedures were implemented in Visual Studio Code with integrated Jupyter Notebook support.

The proposed model was trained using a progressive, scale-wise optimization strategy. Specifically, the training process begins at the coarsest scale and advances to finer resolutions. At each scale , a separate generator–discriminator pair is trained for 300 epochs before freezing its parameters and proceeding to the next level, the detailed model configuration of our framework is provided in Table 2. The learning rate was set to for both the generator and discriminator, optimized using the Adam optimizer with and . For the adversarial objective, we employed the WGAN-GP loss formulation with a gradient penalty coefficient of . The reconstruction loss weight was empirically set to 100. Noise injection at each scale followed a Gaussian distribution, with scale-dependent standard deviation proportional to the RMSE between the upsampled reconstruction and the ground truth at that level. The proposed model requires an average training time of about 6 min for eight scales per epoch.

| Generator | |

| Block 1 | Conv2D (3 × 3, stride=1)−BatchNorm−LeakyReLU(0.2) |

| Block 2 | Conv2D (3 × 3, stride=1)−BatchNorm−LeakyReLU(0.2) |

| Block 3 | Conv2D (3 × 3, stride=1)−BatchNorm−Tanh |

| Discriminator | |

| Block 1 | Conv2D (3 × 3, stride=1)−BatchNorm−LeakyReLU(0.2) |

| Block 2 | Conv2D (3 × 3, stride=1)−BatchNorm−LeakyReLU(0.2) |

| Block 3 | Conv2D (3 × 3, stride=1)−BatchNorm−LeakyReLU(0.2)−MLP |

| MLP | |

| Block 1 | Linear ( , 256)−ReLU() |

| Block 2 | Linear (256, 1)−Sigmoid() |

All baseline and advanced models were re-implemented or fine-tuned using publicly available codebases to ensure consistent training conditions. Hyperparameters for these models were aligned as closely as possible with their original articles, while adapting them to the unconditional setting and the small-scale dataset.

Comparative evaluation and discussion

To evaluate the performance of the proposed hierarchical multi-scale generative framework, a comparative study is conducted with a range of representative generative models. All models are trained under identical conditions using the curated dataset of traditional Chinese watercolor paintings. The evaluation emphasizes both image fidelity and generative diversity, which are crucial for stylistic realism and variety in artistic synthesis.

Standard GAN (Goodfellow et al., 2014) (Baseline): The baseline is a simple generative adversarial network comprising shallow convolutional layers, trained using non-saturating binary cross-entropy loss. Despite its historical significance, this model exhibits considerable limitations in modeling complex spatial compositions. Training instability, mode collapse, and low-resolution outputs are common, making it a weak baseline in the context of high-resolution ink painting generation.

DCGAN (Radford, Metz & Chintala, 2015): DCGAN is a pioneering convolutional GAN architecture designed for image synthesis. It leverages a structured combination of convolutional and transposed convolutional layers, batch normalization, and rectified linear unit (ReLU) activations. In this study, DCGAN demonstrates moderate success in capturing general compositional layout, but fails to preserve the intricate textures and nuanced transitions typical of traditional brushwork.

WGAN-GP (Gulrajani et al., 2017): The WGAN-GP model introduces a significant advancement in GAN stability by adopting the Wasserstein distance as the objective function and enforcing a gradient penalty to maintain Lipschitz continuity. On the curated dataset, WGAN-GP produces more coherent images than earlier models, reducing mode collapse and capturing coarse structures. However, its single-scale design limits its capacity to represent fine-grained ink diffusion patterns and hierarchical visual structures.

StyleGAN2 (Karras et al., 2019): StyleGAN2 is an advanced generative model that incorporates style-based modulation and adaptive instance normalization across multiple layers. It achieves state-of-the-art results on high-resolution synthesis tasks such as facial image generation. In the context of traditional Chinese painting, however, StyleGAN2 is challenged by the limited size of the dataset. It often overfits, leading to repetitive patterns and loss of compositional diversity, although it remains competitive in generating fine textures.

SinGAN (Shaham, Dekel & Michaeli, 2019): SinGAN is a single-image generative model that learns a hierarchical pyramid of fully convolutional GANs, each operating at a different scale. Unlike dataset-driven approaches, SinGAN is trained solely on one input image, enabling it to capture its internal patch distribution and generate diverse variations. This framework is particularly effective for tasks such as texture synthesis, image editing, and harmonization.

The results in Table 3 demonstrate that the proposed model significantly outperforms both traditional and modern generative approaches. Specifically, it achieves an FID of 21.12, which is substantially lower than StyleGAN2 (36.89) and WGAN-GP (42.34), indicating the closest alignment with the real image distribution in feature space. In addition, the model reaches a Diversity Score of 0.412, surpassing StyleGAN2 (0.381), WGAN-GP (0.369) and SinGAN (0.395), highlighting its strong ability to generate diverse outputs without collapsing to a few modes. Moreover, its Inception Score of 5.38 is the highest among all baselines, confirming that the model balances both visual quality and variety in the generated images.

| Model | FID | Diversity score | IS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard GAN | 98.62 | 0.218 | 2.15 |

| DCGAN | 64.77 | 0.274 | 2.84 |

| WGAN-GP | 42.34 | 0.369 | 3.97 |

| StyleGAN2 | 36.89 | 0.381 | 4.52 |

| SinGAN | 30.25 | 0.395 | 4.89 |

| Ours | 21.12 | 0.412 | 5.38 |

Notably, while WGAN-GP and StyleGAN2 improve stability and detail reproduction compared to earlier methods such as Standard GAN and DCGAN, they remain constrained: WGAN-GP is limited by architectural scalability, and StyleGAN2 requires large-scale datasets to perform effectively. Meanwhile, DCGAN, although historically significant, shows considerably weaker performance in capturing stylistic nuances (FID = 64.77; Diversity Score = 0.274). By contrast, our hierarchical and patch-aware design overcomes these limitations, enabling multi-resolution feature learning and faithful reproduction of brushstroke textures, ink wash gradients, and compositional harmony that characterize traditional Chinese watercolor aesthetics. These results not only validate the technical superiority of our framework but also underscore its potential for cultural preservation. This model can be used to digitize and recreate ancient watercolor paintings, ensuring their longevity and accessibility in digital form. At the same time, it can serve as a creative assistant for contemporary artists, offering stylistic suggestions and expanding expressive possibilities at the intersection of tradition and modern AI-driven art.

Visual results

To qualitatively assess the generative capabilities of the proposed model, a selection of synthesized samples is presented in Fig. 4. These images were generated in an unconditional setting using randomly sampled latent vectors. As can be observed, the model successfully captures key stylistic characteristics of traditional Chinese watercolor paintings, including brushstroke granularity, layered mountain formations, ink diffusion effects, and negative space composition.

Figure 4: Examples of traditional Chinese watercolor paintings synthesized by the proposed multi-scale model.

Furthermore, the diversity observed in the outputs generated from different random seeds indicates that the model does not merely “memorize” the limited training samples but instead learns generalizable artistic formation rules. Specifically, although trained on a relatively small dataset, the synthesized results exhibit clear variations in composition, structure, and fine-grained details while consistently preserving the stylistic coherence of traditional Chinese watercolor painting. This capability is largely attributed to the hierarchical multi-scale training framework combined with patch-level adversarial supervision. Such an approach compels the model to learn features across multiple resolutions rather than simply reproducing the entire input images. As a result, the framework can flexibly recombine aesthetic elements to generate novel variations, effectively mitigating the risk of overfitting and reinforcing its reliability under data-scarce conditions. The visual outputs further validate the model’s ability to synthesize diverse compositions that remain faithful to the semantics and aesthetics of the training domain. Notably, the hierarchical structure allows for both large-scale spatial consistency and fine texture realism, which are often difficult to achieve simultaneously in single-scale architectures.

Limitation and future research

Although the proposed hierarchical multi-scale framework demonstrates strong capabilities in synthesizing Chinese watercolor paintings, several limitations remain. The reliance on a relatively small dataset restricts stylistic diversity and limits generalizability, an issue also reported in studies of calcareous sand generation and tabular generative modeling (Chen et al., 2025; Wang et al., 2024a). The unconditional generation setting further reduces flexibility, providing limited user control over motifs or symbolic elements, a problem echoed in research on style-transfer-based change detection (Zhang et al., 2025).

From a computational standpoint, the progressive scale-wise training process is resource-intensive, mirroring efficiency concerns raised in transformer-based and attention-driven architectures (Xu, Li & Chen, 2022; Song et al., 2024). While patch-level adversarial supervision captures local brushstroke details, it does not always enforce long-range compositional coherence, similar to limitations noted in cross-lingual style transfer tasks (Zhao et al., 2024). Moreover, challenges of adapting generative models to culturally rich and domain-specific data (Hussain et al., 2020).

Future work should explore conditional generative mechanisms that integrate semantic or text-based inputs to enhance control, as suggested by prior applications of transfer learning (Nguyen et al., 2022). Expanding toward hybrid GAN–transformer frameworks or diffusion models may also improve scalability and stylistic fidelity while ensuring cultural authenticity.

Conclusion

This study presents a hierarchical multi-scale generative framework capable of synthesizing high-quality traditional Chinese watercolor paintings from limited data. By combining pyramid-based residual learning with patch-level adversarial supervision, the model effectively captures both global compositional structure and fine-grained stylistic details. Experimental results demonstrate notable improvements in image fidelity and diversity compared with state-of-the-art baselines, supported by both quantitative metrics and qualitative analysis. The generated artworks faithfully reproduce hallmark features of classical ink-and-brush painting, including tonal gradation, expressive brushstroke patterns, and balanced composition. Beyond its technical contributions, this framework offers potential for cultural preservation and creative exploration, enabling the generation of new works that respect and extend the aesthetic traditions of Chinese watercolor art.