Leveraging VGG-19 for automated fruit classification in smart agriculture

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Siddhartha Bhattacharyya

- Subject Areas

- Artificial Intelligence, Computer Vision, Data Mining and Machine Learning, Neural Networks

- Keywords

- Computer vision, Deep learning, Fruit classification, Smart agriculture, VGG-19

- Copyright

- © 2025 Sajid et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2025. Leveraging VGG-19 for automated fruit classification in smart agriculture. PeerJ Computer Science 11:e3391 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3391

Abstract

Fruit classification has become increasingly important in a wide range of industrial and consumer-oriented applications. Automated fruit classification systems can significantly enhance efficiency by accurately identifying fruit varieties and supporting informed decisions. In this research, we propose a fast, accurate, and robust fruit classification approach leveraging Deep Learning (DL) techniques. The proposed approach is a fine-tuned, pretrained Visual Geometry Group-19 (VGG-19) convolutional neural network model, known for its depth and superior performance in image recognition and classification tasks. Unlike existing approaches, our proposed approach addresses the unique visual challenges of fruit images, including inter-class similarity, intra-class variability, occlusions, background clutter, and varying illumination conditions, which enhances generalization across both controlled and real-world datasets. This approach is rigorously evaluated using two distinct datasets obtained from Kaggle. Dataset 1 comprises high-resolution images captured under controlled conditions, while Dataset 2, derived from the Kaggle 360 Fruits dataset, contains diverse real-world images with varying backgrounds, lighting conditions, and occlusions. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed model achieves exceptional classification accuracy, recording 99.65% on Dataset 1 and 97.98% on Dataset 2. The above findings underline the accuracy and stability of the fine-tuned VGG-19 model in processing clean and complicated images and pose a viable and scalable real-time fruit classification approach.

Introduction

The correct identification of fruits has emerged as a key image processing problem in computer vision, with many useful applications in agriculture, food technology, and consumer service areas. In precision agriculture, automated fruit recognition is relevant to precision harvest, sorting, and quality grading, all of which contribute to business efficiency and mitigating post harvest losses (Gong & Wu, 2025). Fruit classification has become a common practice in health monitoring systems, diet recommendation tools, and mobile apps that offer nutrition solutions. Similarly, in retail environments, classification systems can facilitate automated checkout processes for fresh produce. Unlike packaged goods, which can be identified through barcodes or QR codes, fruits and vegetables must be recognized visually. This makes automated classification fundamentally dependent on the ability of computer vision models to accurately capture the subtle visual features that distinguish fruits.

Designing a reliable fruit classification system is a challenging task. This is mainly because of the complexity of real-world visual data. Numerous types of fruit show case a high degree of inter-class similarity, such as apples, pears, guavas usually have a similar shape, texture and colour and therefore cannot be differentiated with standard descriptors (Ghazal et al., 2021). At the same time intra-class variation exists enormously within a single fruit variety by factors of ripeness, size and maturity stage significantly affect appearance. The fact that color distribution is being altered through variations in the lighting condition further contributes to the perceived distribution, with occlusions occurring when leaves, packaging material, or overlapping fruits alter the distribution. Moreover, environmental factors such as background clutter, reflections, and non-uniform illumination are common in orchards, kitchens, and marketplaces that pose further difficulties for accurate recognition (Mimma et al., 2022). Collectively, these challenges, including inter-class similarity, intra-class variability, occlusion, and background noise, underscore the complexity of fruit classification and highlight the necessity for advanced Deep Learning (DL) and computer vision techniques capable of robustly addressing these variations.

Previous studies have explored fruit recognition with expertly designed feature extraction generators (i.e., shape, texture, and color), and with traditional machine learning (ML) algorithms such as Support Vector Machines (SVM), k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Naïve Bayes (NB), and Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) (Zhang & Wu, 2012; Pholpho, Pathaveerat & Sirisomboon, 2011; Cen et al., 2016). Although these methods demonstrated moderate accuracy, their weakness was their low robustness in uncontrolled settings. Inconsistency in the illumination, occlusion, and overlapping visual similarities were likely to lead to misclassification. Hybrid approaches introduced optimization algorithms such as Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and Artificial Bee Colony (ABC) to enhance shallow neural network classifiers, with some improvements reported in accuracy (Marimuthu & Roomi, 2017; Lu et al., 2016). Nevertheless, these models were typically evaluated on small datasets or were constrained to specific fruit species, which limited their scalability. Parallel efforts explored hyperspectral imaging, multispectral sensors, or morphological descriptors to improve classification accuracy (Yao et al., 2020; Lü & Tang, 2012; Leekul et al., 2016). While promising, these approaches often relied on expensive, specialized equipment that hindered deployment in everyday consumer or agricultural settings.

With the advent of DL, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), fruit classification witnessed a paradigm shift. CNNs excel at learning hierarchical feature representations directly from raw image data, thereby overcoming the limitations of handcrafted descriptors (Gill et al., 2023; Albarrak et al., 2022; Ilyas, Ahmad & Mehmood, 2023). For example, CNNs have been applied to supermarket fruit datasets containing cluttered scenes, achieving notable improvements in recognition accuracy. Nonetheless, DL methods are highly data-dependent and require large annotated datasets for effective training. In fruit classification, however, the availability of large, diverse, and representative datasets remains limited. Many studies employ small-scale datasets with only a few categories, captured under laboratory-controlled conditions. This mismatch significantly reduces the generalization ability of CNN models when applied to real-world conditions that include noise, occlusions, and non-uniform lighting.

Transfer learning has emerged as a practical solution to alleviate the data scarcity problem, where pretrained models on large-scale datasets such as ImageNet are fine-tuned for fruit classification. Transfer learning reduces training time, prevents overfitting on small datasets, and provides access to powerful pretrained feature extractors. Despite these benefits, existing transfer learning studies on fruit datasets face significant limitations. A major challenge is the domain gap between large-scale natural image datasets and fine-grained fruit datasets. ImageNet-trained models are optimized for broad object categories but may underperform in differentiating fruit varieties that exhibit subtle visual differences. For instance, visually similar categories such as red apples vs. red pears often confuse pretrained models. Furthermore, transfer learning models frequently struggle to adapt to intra-class variability caused by maturity stages, deformation, or environmental effects such as dust, lighting changes, and shadows. These limitations indicate that existing approaches are not fully optimized to handle the unique visual challenges of fruit classification.

Despite these setbacks and constraints, this article will suggest an appropriate and scalable fruit classification method using a fine-tuned Visual Geometry Group-19 (VGG-19) convolutional neural network (Simonyan & Zisserman, 2014). The VGG-19 model is chosen due to its rich network structure and the representation abilities it possesses as well as its successful track record in solving large-scale problems of image recognition. Our work smoothly modifies VGG-19 to fruit data, thereby addressing both cross-class and within-class differences, and it is stable to environmental influences, including light and obstruction. To rigorously test the performance of this method, it is applied to two different datasets: (1) a fruit images dataset with high resolution and (2) the more complex Kaggle 360 Fruits dataset, in which real-world instances of variability include cluttered backgrounds, imperfect lighting, and partial occlusions. This dual-dataset evaluation allows us to systematically examine the generalization of the proposed approach under both ideal and challenging conditions.

The key contributions of this research are as follows:

We identify and analyze the unique visual challenges of fruit classification, including inter-class similarity, intra-class variability, occlusions, background clutter, and lighting changes, which limit the performance of existing approaches.

We develop a transfer-learning-based approach using a fine-tuned VGG-19 model that is specifically optimized for fruit classification tasks, overcoming the domain gap problem observed in prior works.

We rigorously evaluate the proposed approach on two complementary datasets, demonstrating superior accuracy, achieving 99.65% on the high-resolution dataset and 97.98% on the more challenging fruits dataset.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. ‘Literature Review’ presents related work, ‘Approach’ describes the proposed approach, ‘Experimental Setup and Evaluation’ discusses the experimental results, and ‘Conclusions and Future Work’ concludes the study.

Literature review

Fruit classification has become a vital area of research in smart agriculture, driven by the need for automation in sorting, grading, and quality assessment to enhance productivity and reduce human error. Traditional approaches relying on handcrafted features and conventional ML techniques often suffer from limitations such as sensitivity to variations in lighting, orientation, and background noise. Numerous studies have been conducted to develop automated fruit classification systems, focusing on aspects such as ripeness detection of different fruits, disease identification, and citrus quality evaluation as shown in Table 1. Altaheri, Alsulaiman & Muhammad (2019) proposed a DL-based classification model for robotic harvesting, integrating three methodologies to classify date fruit in real-time. Their framework combined deep convolutional transfer learning with fine-tuning of pre-trained models, such as AlexNet, to distinguish date fruits by their maturity level and also facilitate harvesting decisions. That approach aimed to establish a robust machine vision system for agricultural applications.

| Reference | DL models | Dataset | Classes | Split protocol (%) | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sa et al. (2016) | Faster R-CNN | FIDS-30 | 6 | Train 80 and Test 20 | 90.00 |

| Fu et al. (2018) | CNN | Kiwifruit | 1 | Train 70 and Test 30. | 89.29 |

| Thi Phuong Chung & Van Tai (2019) | E-Net | Fruit-360 | 6 | Train 80 and Test 20 | 93.00 |

| Divya Shree, Brunda & Shobha Rani (2019) | DAN | Fruit-360 | 6 | Train 70 and Test 30 | 91.00 |

| Munir, Umar & Yousaf (2020) | RESNET-50 | Fruits-360 AND FIDS-30 | 30 | Train 80 and Test 20 | 89.16 |

| Xiong et al. (2020) | M-YOLOV3 | Mango Orchard | – | Train 75, Test 15 and val 10 | 92.00 |

| Liu (2020) | InterFruit | InterFruit | – | Train 70, Test 30 | 92.40 |

| Shahi et al. (2022) | MobileNetV2 | Fruits-360 | 5 | Train 80, Test 20 | 94.00 |

| Xue, Liu & Ma (2023) | DenseNet-169 | Fruits-360 | 15 | Train 80, Test 20 | 91.46 |

| Alharbi et al. (2023) | Tunicate Swarm Algorithm | Fruits-360 | 6 | Train 80, Test 20 | 93.00 |

| Sunday et al. (2023) | Inception-V3 CNN | Fruits-360 | – | Train 80, Test 10 and Val 10 | 85.8 |

| Gill et al. (2023) | CNN+RNN+RNN | Fruits-360 | 7 | Train 80, Test 20 | 86.00 |

| Mishra & Singh (2024) | CNN+VGG16 | Fruits-360 | 6 | Train 80, Test 20 | 94.92 |

Nasiri, Taheri-Garavand & Zhang (2019) developed a system for sorting date by integrating a CNN that extract features with advanced computer vision (CV) and DL techniques. Koirala et al. (2019) applied DL models for fruit type classification and yield estimation based on crop measurement standards. Their approach utilized object detection techniques, particularly Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG), to define block and cell sizes during fruit yield analysis and classification. Additionally, image preprocessing techniques, such as resizing, color adjustments, and data augmentation, were implemented. A robust Region Analysis (RA) detection system was employed to eliminate low-scoring hypotheses and refine probability thresholds. Altaheri, Alsulaiman & Muhammad (2019) employed DL models, the study lacks sufficient details on the automation aspects of fruit classification. Ahmed, Islam & Ema (2019) developed a novel hybrid algorithm termed GAACO, which integrates Tabu lists, Ant Colony Optimization (ACO), and Genetic Algorithms (GA), for diverse image segmentation tasks, including the segmentation of fruit and plant leaf images. In this study, the SVM was employed for fruit and plant leaf identification. The GA was used to determine optimal cluster centers within the solution space, while the ACO was deployed to identify the optimal solution for the segmentation process.

Elwirehardja & Prayoga (2021) utilized DL methods to classify the ripeness of oil palm fresh fruit bunches using mobile devices. Their approach involved ImageNet transfer learning with four lightweight CNN models and a nine-angle cropping augmentation strategy. Phate, Malmathanraj & Palanisamy (2021) developed an SVM-based method and combined it with weighting methods using an optimized Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS) integrated with cross-validation. Specifically, the study analyzed weighting approaches related to the hybrid ANFIS framework through two well-established optimization techniques. The first optimization technique involved evaluating the performance of GA-ANFIS models across varying population sizes. The MobileNetV1 model was employed to assess classification accuracy effectively. Ukwuoma et al. (2022) proposed DL techniques for fruit detection through computer vision methodologies. Their approach classified fruits by analyzing distinctive attributes, including color, shape, texture, and fruit type-specific features.

The task of automated fruit classification and detection using ML and CV remains complex and challenging. Classification of different fruits based on their features is tedious and prone to inconsistencies due to their different nature, which encompasses variations in size, texture, shape, and intensity (Gill et al., 2022; Ukwuoma et al., 2022). Despite advancements, challenges persist; for instance, the selection of multi-feature and classification processes in SVM presents difficulties in fruit categorization.

Shankar et al. (2022) introduced an AFC framework that employs a hyperparameter optimized deep transfer learning (AFC-HPODTL) approach. The AFC-HPODTL approach incorporates contrast enhancement techniques as a preprocessing step to improve quality of image. In their work, the DenseNet169 architecture was utilized for feature extraction, and Adam optimizer used for fine-tuning the initial parameters of the model. Furthermore, the RNN was implemented for the identification and classification of fruits. To optimize the hyperparameters of the RNN and enhance classification accuracy, the authors applied the Aquila Optimization Algorithm (AOA).

Mishra et al. (2022) proposed a MobileNetV2 variant of a CNN model integrated with a Modified Sine Cosine Algorithm–PSO (MSCA–PSO) to classify avocados as either it is healthy or diseased based on image data. The Avocado image dataset was used as input to evaluate the model performance. Diana Andrushia & Trephena Patricia (2018) developed an automated approach for detecting mango fruit skin diseases. Their method involved extracting key features such as shape, color, and texture from mango samples. The ABC algorithm was utilized for the selection of feature and optimization, ensuring the identification of the most relevant attributes for disease detection. A novel aspect of this work was the application of meta-heuristic techniques in feature selection for mango disease identification. The ML-based algorithm SVM used for training and testing the proposed model, demonstrating its effectiveness.

Wijaya, Mulyani & Anggraini (2023) proposed a classification model employing CNN for rapid and accurate identification of citrus fruit types. Meanwhile, Yang et al. (2022) introduced a cost-effective, DL-based approach for apples that performs automated grading and sorting. Their methodology incorporated several phases within an artificial intelligence (AI) framework, including grayscale processing, image enhancement, feature extraction, and binarization, to achieve grading aligned with predefined apple standards effectively.

Recent advances in fruit classification and fruit disease detection have leveraged both lightweight and transformer-based architectures to improve accuracy and computational efficiency (Mehmood, Ahmad & Ilyas, 2023). Raza et al. (2024) proposed Citrus Fruit Classification with X-ray Images Using Features Enhanced Vision Transformer Architecture but achieved 91% accuracy. Bu et al. (2025) proposed an improved ShuffleNetV2 model for detecting freshness, achieving an accuracy of 91%. This approach outperforms traditional CNN-based methods but still exhibits sensitivity to environmental noise and limited robustness under orchard conditions. Similarly, more recently, Liu et al. (2025) introduced the Channel Grouping Vision Transformer (CGViT), which achieved outstanding accuracy 89.58% on a hierarchical grocery store dataset, demonstrating strong lightweight classification performance yet revealing limitations in cluttered and variable environments due to its channel grouping and Transformer-based fusion design. However, these efficiency-oriented designs often compromise representational depth, leading to reduced generalization in complex, large-scale, or fine-grained fruit classification scenarios where texture variations are subtle and background conditions are heterogeneous.

In contrast to existing research, VGG-19 is having relatively higher parameter count, continues to serve as a reliable and efficient model in the fruit classification task due to its deep hierarchical feature extraction, strong robustness across diverse visual conditions, and adaptability in transfer learning settings. It is well established architecture consistently captures fine-grained spatial and textural cues that lightweight or transformer hybrid models may overlook, thereby offering a stable and interpretable foundation for benchmark. Consequently, the choice of VGG-19 in this study is well justified, as it not only enables meaningful comparison against emerging architectures but also ensures consistent performance under varied agricultural imaging conditions, making it a dependable baseline for advancing fruit classification research.

Approach

The proposed approach for fruit classification leverages the VGG-19 models, a widely recognized DL model for its exceptional performance in image recognition and classification tasks. This approach begins with image preprocessing, where input fruit images are resized, normalized, and augmented to enhance the diversity and quality of the training dataset. Augmentation techniques such as rotation, flipping, and cropping are employed to make the model robust to variations in fruit orientation, size, and lighting conditions. These preprocessed images serve as input to the VGG-19 architecture, which consists of 19 layers, including convolutional, pooling, and fully connected layers, followed by a SoftMax classifier for fruit label prediction.

In this proposed approach, the convolutional layers of VGG-19 extract hierarchical features, such as shapes, textures, and edges, from the input images. These features are then passed through max-pooling layers to reduce dimensionality while retaining essential information. To prevent overfitting and improve generalization, dropout layers are incorporated between the fully connected layers (Srivastava et al., 2014). The framework fine-tunes the model by retraining its top layers on the fruit dataset while preserving pre-trained weights for lower layers, ensuring the model’s ability to leverage pre-learned visual features. The framework is optimized using a categorical cross-entropy loss function and the SGD optimizer, achieving high accuracy in distinguishing between various fruit classes based on their unique visual characteristics. This approach effectively addresses challenges such as intra-class variability and inter-class similarity in fruit classification tasks.

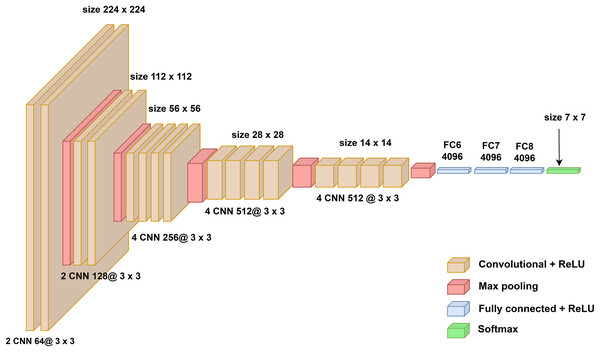

The architectures of the model, depicted in Fig. 1, is based on the VGG-19 framework, a sophisticated and deeper CNN model. This model is composed of five sequential convolutional blocks, with adjacent blocks interconnected through max pooling layers to reduce spatial dimensions progressively. Each block includes a series of convolutional layers utilizing 3 3 kernels, ensuring fine-grained feature extraction. Within a block, the number of convolutional kernels remains constant but increases progressively across blocks, starting with 64 kernels in the initial block and culminating with 512 kernels in the final one. This configuration results in a total of 19 trainable layers in VGG-19 as detailed in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: The architecture of VGG-19 model.

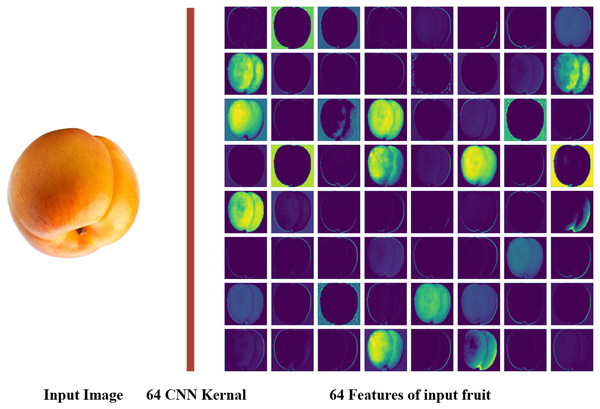

The feature extraction process of the proposed model explained in Fig. 2, which shows a sample input image of an apricot and its corresponding 64 feature maps generated by the first convolutional layer of fine-tuned VGG-19. These feature maps illustrate the early-stage feature extraction capability of the model, highlighting its ability to capture fundamental patterns such as edges and textures essential for subsequent layers to build complex representations.

Figure 2: Sixty-four features map of VGG-19 model (https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/moltean/fruits).

Experimental setup and evaluation

Materials and methods

This section explains the materials and methods of the proposed approach. The experiments were conducted on Kaggle’s cloud-based GPU platform, which provides access to high-performance computing resources essential for training DL models. The runtime environment utilized a Windows-based operating system with Python 3.10 and key libraries such as TensorFlow/Keras. The hardware acceleration was enabled via NVIDIA Tesla T4 GPUs, which significantly reduced training time for the VGG-19 model due to their CUDA cores and optimized parallel processing capabilities. The GPU was coupled with 16 GB of VRAM and supported by Kaggle’s allocated Intel Xeon processors, ensuring efficient handling of the fruit image dataset during preprocessing, augmentation, and model evaluation. To ensure reproducibility, all training images were resized to pixels and augmented using random rotation ( ), horizontal flipping ( ), and color jitter (brightness, contrast, saturation ; hue ). The validation and test sets were only resized and normalized using ImageNet statistics. The model is evaluated and compared with baseline approaches. For these experiments, we have selected two datasets. Both datasets are taken from Fruit 360. Dataset 1 is very elaborative and clear, but Dataset 2 has complex images. We have chosen the second dataset to check the generalizability of the proposed approach. For the VGG-19 model, we applied a selective layer freezing strategy to optimize feature learning for different datasets. For Dataset 1, no layers were frozen because the dataset is relatively clean, allowing the network to fine-tune all convolutional layers for optimal feature extraction. In contrast, for Dataset 2, which contains more complex and blurred images, the first ten convolutional layers were frozen. This approach preserves the low-level feature representations learned from ImageNet while enabling the higher layers to adapt to dataset-specific variations, such as occlusion, lighting, and blur. To ensure robust and statistically reliable performance evaluation of our VGG-19 model, we performed 5-fold cross-validation across all datasets. In each fold, the dataset was partitioned into 80% training and 20% testing, ensuring that all classes were represented proportionally. The model was trained independently for each fold, and the final performance metrics like accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score and per-class accuracies to provide a more comprehensive evaluation of the VGG-19 model’s performance.

Dataset 1

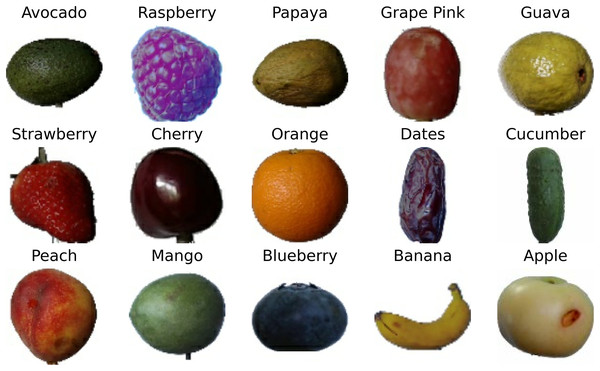

The publicly available dataset fruit dataset called fruit 360 dataset, is collected from Kaggle (https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/moltean/fruits), compiled recently, consisted of 11,570 fruits images in JPG format. Each image has a resolution of 100 × 100 pixels and is distributed across 15 different fruit classes. The detail of Dataset 1 is given in Table 2. The dataset contains RGB images. These images are collected under varying conditions, including different dates and times, to enhance diversity of the dataset Fig. 3 provides representative samples from this dataset, illustrating its coverage of various produce items.

| Fruit class | Sample count | Fruit class | Sample count |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apple | 785 | Guava | 830 |

| Avocado | 715 | Mango | 830 |

| Banana | 830 | Orange | 800 |

| Blueberry | 770 | Papaya | 820 |

| Cherry | 820 | Peach | 820 |

| Cucumber | 250 | Raspberry | 830 |

| Dates | 830 | Strawberry | 820 |

| Grape pink | 820 |

Figure 3: Sample fruit images from Dataset 1 (https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/moltean/fruits).

Dataset 2

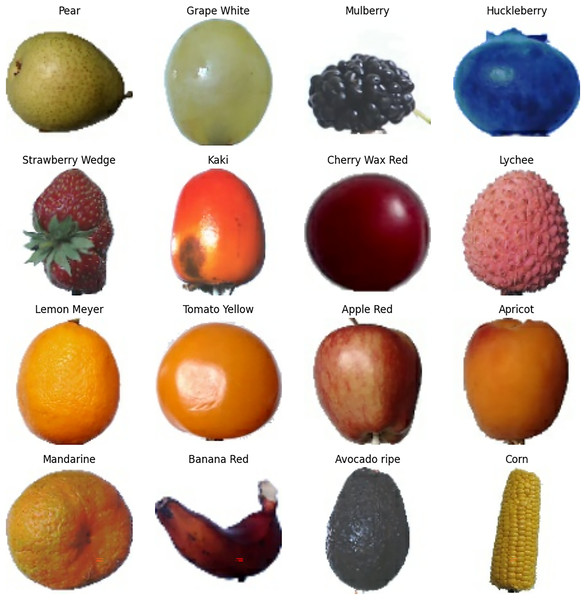

Dataset 2 was specifically collected to check the generalize-ability of our proposed approach from the same source Kaggle (https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/moltean/fruits). This dataset consisted of 13,485 images belongs to 16 distinct classes of fruits as outlined in Table 3. Figure 4 depicts example images from this dataset, highlighting its variety and relevance to the task. The images in Dataset 1, as shown in Fig. 3, are relatively straightforward to classify due to their simplicity. Each image contains fruits from a single class, and the backgrounds are uniform, making them easier to analyze. In contrast, Dataset 2 presents a greater challenge. Many images in this dataset feature multiple classes of fruits within the same frame, and the backgrounds are not homogeneous. Furthermore, this dataset includes a wide range of scenarios, such as half and sliced fruits, partially merged with other fruits, fruits inside bags, or sliced fruits on dishes. Some images even depict fruits in challenging environments, where the background and other objects make the classification task more complex.

| Fruit class | Sample count | Fruit class | Sample count |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apple red | 820 | Kaki | 830 |

| Apricot | 820 | Lemon meyer | 830 |

| Avocado | 830 | Lychee | 830 |

| Banana red | 830 | Mandarine | 830 |

| Cherry wax red | 820 | Mulberry | 820 |

| Corn | 750 | Pear | 820 |

| Grape white | 830 | Strawberry | 1,230 |

| Huckleberry | 830 | Tomato yellow | 765 |

Figure 4: Sample fruit images from Dataset 2 (https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/moltean/fruits).

For all experiments, the datasets underwent preprocessing before being divided into training, validation, and test datasets. Specifically, 80% for training, while the remaining 20% was reserved for testing because we chose 5-fold cross validation approach. We employed Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) with an adaptive learning rate to optimize the model. Although Adam-based optimizers are known for fast convergence, they often generalize sub-optimally on fine-grained classification tasks with small to medium datasets, such as fruit image datasets. Adaptive SGD, combined with momentum, enables the model to converge steadily while avoiding sharp minima, which can improve generalization to complex and blurred fruit images. The learning rate was dynamically adjusted at each epoch, with its value determined based on the epoch number, as outlined in Eq. (1).

(1) where the learning rate of the proposed model at each epoch number , denoted as , is dynamically adjusted throughout the training process. The initial learning rate, , serves as the starting value and is progressively modified depending on the current epoch number . This approach helps optimize the training process by allowing the model to make larger adjustments in the earlier stages and finer adjustments as it converges toward a minimum. The adaptive learning rate formula typically involves a decay factor or an exponentially decreasing rate with respect to the number of epochs, allowing for faster convergence early on and a more precise adjustment as the model fine-tunes its parameters in later stages.

Experimental results on first dataset

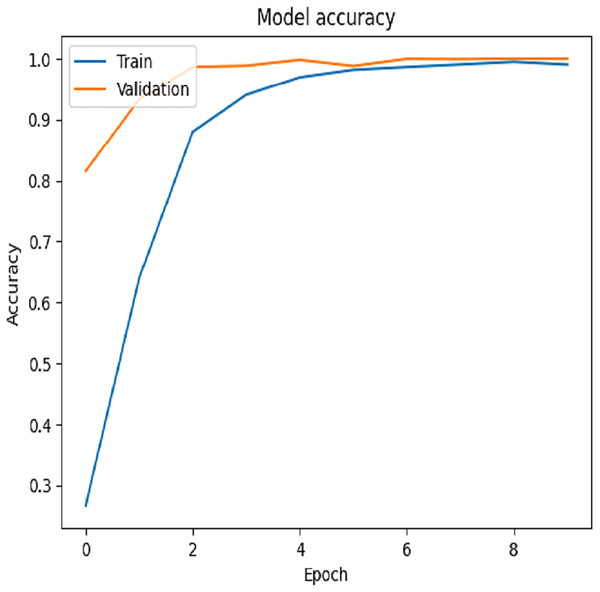

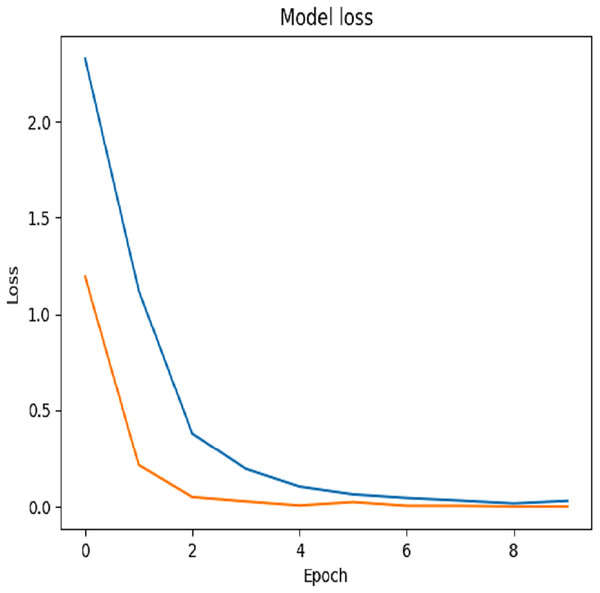

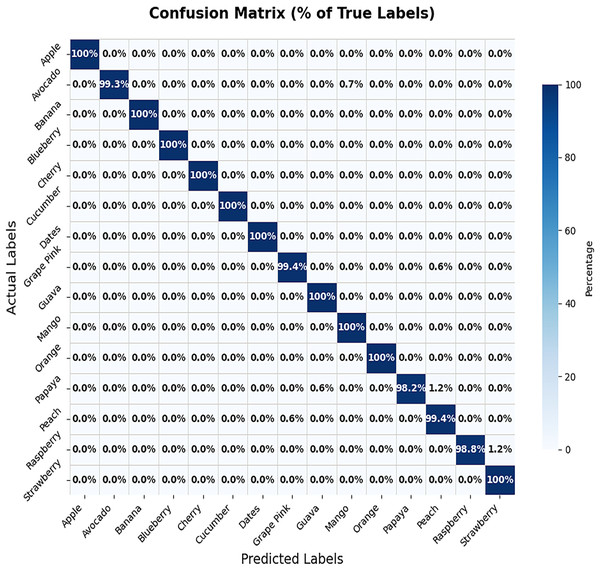

In this proposed study, we utilized a batch size of 64 and trained the model for 10 epochs on the training dataset. The performance of the fine-tuned VGG-19 model was evaluated using Dataset 1. The fine-tuning process was constrained to the final layers of the network and employed an initial learning rate of 0.001. As illustrated in Fig. 5, the model achieved a test accuracy of 99.65%, while the corresponding loss curve is depicted in Fig. 6. Row-wise percentages have been added to the confusion matrix to clearly illustrate the distribution of correct classifications and misclassifications for each true class, as shown in Fig. 7. This confusion matrix reveals that the model misclassified only eight out of 2,314 test samples. Specifically, the misclassifications included one avocado samples predicted as mango, one grape pink as peach, two papaya as peach and one papaya as guava, one peach as grape pink, and two raspberry samples as strawberry. These results underscore the robustness and reliability of the fine-tuned VGG-19 model on Dataset 1. The fruit datasets used in this study exhibit class imbalance. For example cucumber, contain only 250 images. To mitigate the effect of class imbalance during training of VGG-19, we employed class-weighted loss in the categorical cross-entropy function. Assigning higher loss weights to underrepresented classes ensures that the network pays more attention to these minority classes, improving overall classification performance without artificially inflating the dataset size.

Figure 5: Training vs. validation accuracy on first dataset.

Figure 6: Testing loss of Dataset 1.

Figure 7: Percentage-wise confusion matrix of Dataset 1.

The other DL models, like CNN, MobileNetV3-Small, and EfficientNet-Lite, are also implemented and evaluated on the same dataset to compare the effectiveness and performance of the proposed model. The dataset 1 achieved an accuracies are 0.873 on MobileNetV3-Small, and 0.889 on EfficientNet-Lite. The results of these three algorithms are not superior on Dataset 1 from VGG-19 as shown in Table 4. Despite the dataset’s simplicity, featuring distinct interclass variations and minimal intraclass variations, the accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score is relatively low. This is likely due to the limited size of the training dataset but VGG-19 outperformed on this same dataset.

| VGG-19 | MobileNetV3 | EfficientNet-lite | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model name | Precision | Recall | F1-score | Precision | Recall | F1-score | Precision | Recall | F1-score |

| Apple | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.894 | 0.852 | 0.872 | 0.912 | 0.880 | 0.896 |

| Avocado | 1.000 | 0.993 | 0.996 | 0.923 | 0.910 | 0.916 | 0.931 | 0.920 | 0.925 |

| Banana | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.881 | 0.860 | 0.870 | 0.902 | 0.890 | 0.896 |

| Blueberry | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.809 | 0.830 | 0.819 | 0.841 | 0.860 | 0.851 |

| Cherry | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.845 | 0.860 | 0.852 | 0.864 | 0.880 | 0.872 |

| Cucumber | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.913 | 0.890 | 0.901 | 0.928 | 0.910 | 0.919 |

| Dates | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.901 | 0.880 | 0.890 | 0.922 | 0.900 | 0.911 |

| Grape pink | 0.993 | 0.993 | 0.993 | 0.882 | 0.870 | 0.876 | 0.865 | 0.840 | 0.852 |

| Guava | 0.994 | 1.000 | 0.997 | 0.898 | 0.920 | 0.909 | 0.918 | 0.930 | 0.924 |

| Mango | 0.994 | 1.000 | 0.997 | 0.842 | 0.810 | 0.826 | 0.871 | 0.840 | 0.855 |

| Orange | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.865 | 0.840 | 0.852 | 0.882 | 0.870 | 0.876 |

| Papaya | 1.000 | 0.981 | 0.990 | 0.832 | 0.870 | 0.851 | 0.861 | 0.890 | 0.875 |

| Peach | 0.981 | 0.993 | 0.987 | 0.888 | 0.860 | 0.874 | 0.905 | 0.880 | 0.892 |

| Raspberry | 1.000 | 0.988 | 0.993 | 0.824 | 0.850 | 0.837 | 0.854 | 0.870 | 0.862 |

| Strawberry | 0.988 | 1.000 | 0.993 | 0.876 | 0.890 | 0.883 | 0.895 | 0.910 | 0.902 |

Experimental results on second dataset

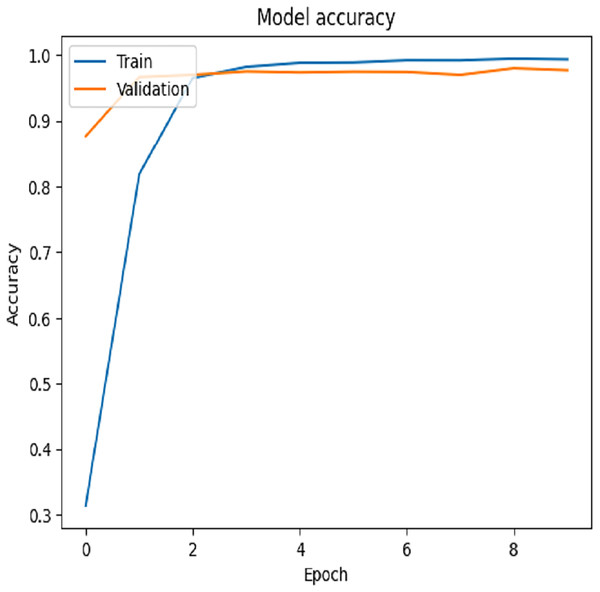

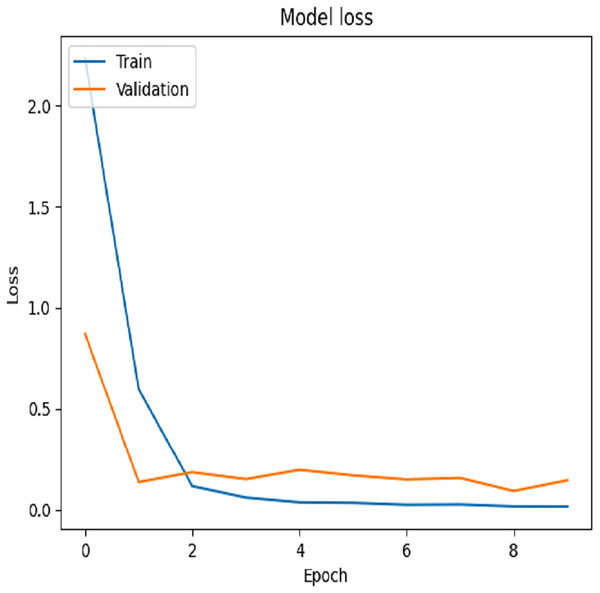

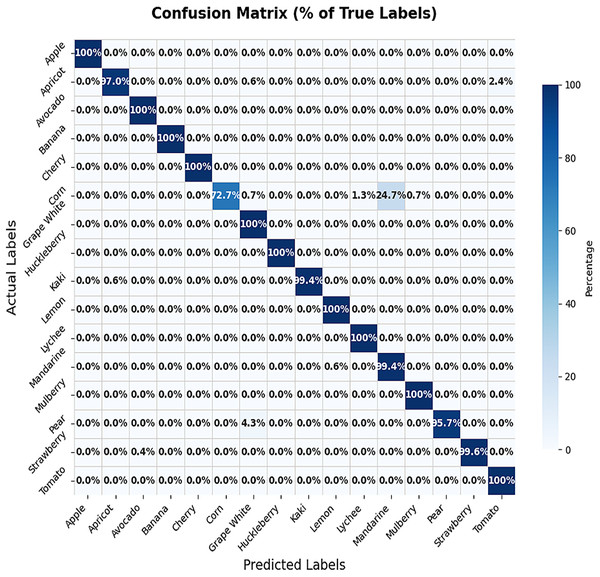

For Dataset 2, we adjusted the training configuration by using a batch size of 64 samples and 10 epochs, as the dataset size is relatively larger than Dataset 1. The final experiment focused on fine-tuning the VGG-19 model using Dataset 2. During the training process on Dataset 2, the first ten convolutional layers were frozen to retain low-level feature representations, while the remaining layers were fine-tuned to adapt to the new data distribution. The model was trained for 10 epochs with a learning rate of 0.001. This fine-tuning strategy resulted in a training accuracy of 99.97% and a test accuracy of 97.92%, as illustrated by the training and validation accuracy trends in Fig. 8. The corresponding loss progression over epochs is depicted in Fig. 9, demonstrating consistent convergence behavior. A detailed view of the model’s classification performance on the test set is provided through the percentage-wise confusion matrix in Fig. 10 and Table 5, which highlights the specific class-level prediction outcomes.

Figure 8: Testing accuracies on Dataset 2.

Figure 9: Testing loss of Dataset 2.

Figure 10: Percentage-wise confusion matrix of Dataset 2.

| VGG-19 | MobileNetV3 | EfficientNet-lite | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model name | Precision | Recall | F1-score | Precision | Recall | F1-score | Precision | Recall | F1-score |

| Apple red | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.852 | 0.830 | 0.841 | 0.865 | 0.845 | 0.855 |

| Apricot | 0.993 | 0.969 | 0.981 | 0.821 | 0.840 | 0.830 | 0.834 | 0.865 | 0.849 |

| Avocado | 0.994 | 1.000 | 0.997 | 0.863 | 0.850 | 0.856 | 0.878 | 0.865 | 0.871 |

| Banana red | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.878 | 0.860 | 0.869 | 0.892 | 0.875 | 0.883 |

| Cherry wax red | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.832 | 0.810 | 0.821 | 0.848 | 0.825 | 0.836 |

| Corn | 1.000 | 0.726 | 0.841 | 0.845 | 0.875 | 0.860 | 0.862 | 0.885 | 0.873 |

| Grape white | 0.948 | 1.000 | 0.973 | 0.854 | 0.840 | 0.847 | 0.839 | 0.825 | 0.832 |

| Huckleberry | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.801 | 0.835 | 0.818 | 0.823 | 0.850 | 0.836 |

| Kaki | 1.000 | 0.994 | 0.997 | 0.854 | 0.840 | 0.847 | 0.869 | 0.855 | 0.862 |

| Lemon meyer | 0.994 | 1.000 | 0.997 | 0.868 | 0.855 | 0.861 | 0.882 | 0.870 | 0.876 |

| Lychee | 0.988 | 1.000 | 0.994 | 0.825 | 0.845 | 0.835 | 0.842 | 0.860 | 0.851 |

| Mandarine | 0.816 | 0.994 | 0.896 | 0.871 | 0.840 | 0.855 | 0.885 | 0.855 | 0.870 |

| Mulberry | 0.993 | 1.000 | 0.997 | 0.815 | 0.830 | 0.822 | 0.832 | 0.845 | 0.838 |

| Pear | 1.000 | 0.957 | 0.978 | 0.862 | 0.845 | 0.853 | 0.877 | 0.860 | 0.868 |

| Strawberry | 1.000 | 0.995 | 0.998 | 0.834 | 0.815 | 0.824 | 0.851 | 0.830 | 0.840 |

| Tomato yellow | 0.974 | 1.000 | 0.987 | 0.849 | 0.875 | 0.862 | 0.864 | 0.890 | 0.877 |

The classification results of other DL models like CNN, MobileNetV3-Small, and EfficientNet-Lite are evaluated on Dataset 2, yielding a classification accuracy of less than 85.7%, 84.7%, and 85.9%, respectively. The poor performance is likely due to the complex and blurred images as compared to Dataset 1.

Comparison with DL models and baseline approaches

The proposed approach performance is compared with five baseline approaches and 3 DL models. We evaluated the performance of our model using the publicly available datasets. This dataset has been utilized in prior studies for fruit classification tasks, allowing for a comparative analysis with other techniques reported in the literature. The classification results of the proposed approach, DL models, and baseline approaches are summarised in Tables 6 and 7. This comparison highlights the effectiveness of the proposed approach relative to existing methods. Our appraoch significantly outperforms the strongest previous model by a margin of 3.1% in absolute accuracy, which corresponds to a substantial 17.5% reduction in the error rate. This leap in performance, alongside near-perfect scores in precision, recall, and F1-score, underscores the profound advantage of VGG-19 over traditional ML and DL models for fruit classification.

| Weighted | Micro | Macro | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Dataset | Accuracy SD | Precision | Recall | F1-score | Precision | Recall | F1-score | Precision | Recall | F1-score |

| VGG-19 | 1 | 0.996 | 0.996 | 0.996 | 0.996 | 0.996 | 0.996 | 0.996 | 0.996 | 0.996 | |

| VGG-19 | 2 | 0.982 | 0.979 | 0.978 | 0.979 | 0.978 | 0.979 | 0.981 | 0.977 | 0.977 | |

| MobileNetV3-Small | 1 | 0.866 | 0.863 | 0.864 | 0.873 | 0.873 | 0.873 | 0.866 | 0.863 | 0.864 | |

| MobileNetV3-Small | 2 | 0.844 | 0.843 | 0.843 | 0.844 | 76.24 | 0.844 | 0.844 | 0.843 | 0.843 | |

| EfficientNet-Lite | 1 | 0.888 | 0.886 | 0.887 | 0.889 | 0.889 | 0.889 | 0.888 | 0.886 | 0.886 | |

| EfficientNet-Lite | 2 | 0.858 | 0.857 | 0.857 | 0.857 | 0.857 | 0.857 | 0.858 | 0.857 | 0.857 | |

| CNN | 1 | 0.884 | 0.885 | 0.884 | 0.885 | 0.885 | 0.885 | 0.878 | 0.877 | 0.877 | |

| CNN | 2 | 0.856 | 0.857 | 0.856 | 0.857 | 0.857 | 0.857 | 0.848 | 0.847 | 0.847 | |

| Model | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1-score (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fu et al. (2018) | 89.2 | 88.1 | 90.0 | 89.0 |

| Xiong et al. (2020) | 92.0 | 91.5 | 92.8 | 92.1 |

| Shahi et al. (2022) | 94.0 | 93.8 | 94.5 | 94.1 |

| Gill et al. (2023) | 86.0 | 84.2 | 88.5 | 86.3 |

| Mishra & Singh (2024) | 96.5 | 96.0 | 97.2 | 96.6 |

| Proposed VGG-19 | 99.6 | 99.6 | 99.7 | 99.6 |

Furthermore, when we evaluated against other DL models on our datasets, VGG-19 consistently ranked as the top performer. It surpassed efficient models like MobileNetV3-Small and EfficientNet-Lite by over 10 percent in accuracy and significantly outperformed a standard CNN, validating that its increased depth and architectural design are critical for capturing the complex hierarchical features necessary for optimal performance. This confirms that the exceptional results are not merely a product of using a DL model but are specifically attributable to the effectiveness of the VGG-19 architecture. We also performed a train-from-scratch experiment on VGG-19; however, the results showed significant overfitting and yielded around 5% lower accuracy compared to transfer learning, confirming that pretrained ImageNet weights are more effective for fruit classification.

Threats to validity

We recognize potential threats to the construct validity of our proposed approach, particularly regarding the selection of evaluation metrics. While we primarily utilize accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score as metrics, additional measures such as error rate, and AUC can also be calculated. Furthermore, we have included a detailed confusion matrix, which is widely adopted within the research community. However, it is essential to acknowledge that an extensive reliance on these metrics may pose certain limitations to construct validity.

Additionally, classification algorithms are prone to validity threats associated with hyperparameter configurations. To mitigate this, we conducted a series of experiments varying hyperparameters, including batch size and learning rate, rather than relying solely on default settings. However, it should be noted that adjustments to these parameters may still influence the overall results.

The adoption of the VGG-19 model for fruit classification represents another potential construct validity concern. Although alternative models are available, VGG-19 was selected due to its superior performance relative to other options at the time of the study. Nevertheless, the lack of comprehensive object detection tools tailored for fruit classification could impact the efficacy of the proposed approach.

Internal validity challenges are also acknowledged, particularly concerning the implementation of our methodology. To address this, we performed rigorous cross-verifications to ensure methodological accuracy. Despite these efforts, the possibility of overlooked errors cannot be completely ruled out.

Regarding external validity, the generalizability of our approach warrants consideration. While the analysis was conducted on a fruit dataset, the methodology is potentially applicable to the classification of other fruits and vegetables. However, the limited sample size in this research poses an additional external validity threat. DL models typically require extensive training data and parameter fine-tuning to achieve optimal performance. As such, the constrained dataset size may limit the generalizability of our findings and the depth of exploration into diverse fruits and vegetables. The generalizability of our results is also limited by the use of a single data source and image-level labels, which restrict clinical interpretability.

Conclusions and future work

In this study, three DL based models, namely CNN, MobileNetV3-Small and EfficientNet-Lite, together with a fine-tuned VGG-19 model, are used to propose a framework to classify different fruits. The method was tested using two datasets which had different sizes and complexities, to determine its generalization ability. The findings show that the fine-tuned VGG-19 outperformed in both datasets and this shows that it adapted to the diverse categories of tracked fruits. In contrast, the CNN, MobileNetV3-Small, and EfficientNet-Lite produced good performance on the smaller and less complex dataset, but their accuracy declined when tested on the complex dataset. This suggests that while lightweight models are promising for efficiency and rapid deployment, they may require further optimization to maintain performance on more complex tasks. A comparative analysis with five existing approaches from the literature revealed that the proposed models outperformed these methods in terms of classification accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score on both datasets, underscoring the effectiveness of the proposed approach. However, the study also acknowledges certain limitations, particularly the reliance on controlled datasets, which may not fully capture the variability of real-world environments.

To address these challenges, our future research will focus on expanding the approach with more diverse datasets, encompassing different lighting conditions, backgrounds, and fruit variations. Additionally, the integration of an object detection pipeline is planned to enhance the system capability in handling complex, cluttered images. Further directions include real-world deployment and performance testing on edge devices and cloud infrastructures, as well as a systematic exploration of hyperparameters to improve both robustness and scalability of the proposed system.