Multi-modal sentiment analysis framework for Urdu language opinion videos

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Siddhartha Bhattacharyya

- Subject Areas

- Algorithms and Analysis of Algorithms, Data Mining and Machine Learning, Natural Language and Speech, Optimization Theory and Computation, Sentiment Analysis

- Keywords

- Urdu language, Multi-modal sentiment analysis, Convolutional neural network

- Copyright

- © 2025 Butt et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2025. Multi-modal sentiment analysis framework for Urdu language opinion videos. PeerJ Computer Science 11:e3369 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3369

Abstract

Multi-modal sentiment analysis lies at the intersection of natural-language processing and multimedia analysis, aiming to unravel complex emotional expressions in multimedia content. This article presents a novel approach to Urdu multi-modal sentiment analysis, focusing on the integration of textual, acoustic, and visual cues to predict sentiment. Our methodology involves a systematic approach to feature extraction from each modality, followed by individual and fused modality sentiment classification. We employ a convolutional neural network (CNN) model integrated with 300-dimensional Embedding FastText to capture meaningful text representations in the textual modality. The acoustic modality utilizes the Librosa library for audio feature extraction, encompassing Mel-frequency cepstral coefficients (MFCCs), intensity, pitch, and loudness. We utilize three-dimensional convolutional neural networks (3D-CNNs) to extract spatial and temporal features from videos for the visual modality. We explore feature- and decision-level fusion techniques to combine the strengths of individual modalities. The results highlight the effectiveness of the fused approach, achieving an accuracy of 91.18%. Our findings underscore the importance of leveraging multiple modalities for comprehensive sentiment analysis, opening avenues for applications in social media sentiment assessment, content recommendation, and market sentiment evaluation. The proposed framework not only contributes to the advancement of Urdu sentiment analysis but also serves as a stepping stone for further research in multilingual and cross-modal sentiment analysis, thereby enriching our understanding of emotions expressed in multimedia content.

Introduction

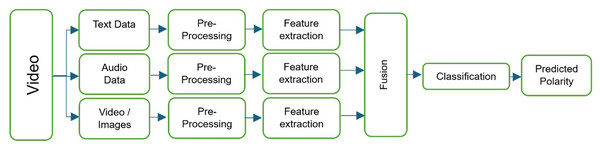

Urdu multi-modal sentiment analysis is the task of identifying the sentiment (emotional content) of Urdu-language utterances when they are accompanied by additional modalities such as audio or video (Khan et al., 2022). This can be useful in various applications, such as social media analysis, customer service, and market research. Sentiment analysis and emotion recognition are important areas of research within the field of affective computing, which aims to enable intelligent systems to perceive, understand, and respond to human emotions (Gandhi et al., 2023; Kratzwald et al., 2018). These techniques are used to analyze large amounts of data in order to extract and understand the emotions and opinions expressed in the data (Yusupova et al., 2021). However, sentiment analysis and emotion recognition are difficult tasks, requiring a deep understanding of language syntax and semantics, as well as the ability to handle informal language and expressions such as slang, irony, and emoticons (Alslaity & Orji, 2022). These techniques have a range of applications in business, healthcare, education, and other fields (Aslam, Sargano & Habib, 2023; Chen et al., 2023). Machine learning and deep learning approaches have been used to improve the accuracy and effectiveness of sentiment analysis and emotion recognition algorithms (Li & Li, 2023). Deep learning in particular has gained popularity due to its ability to handle large amounts of data and improve classification and modeling outcomes (Kratzwald et al., 2018). There has been a growing interest in developing sentiment analysis algorithms for languages other than English, including for the Urdu language (Liaqat et al., 2022; Khattak et al., 2021). Urdu is a South Asian language spoken by over 169 million people, primarily in Pakistan and India (Khan et al., 2021). It is written in a modified version of the Arabic script and has a rich literary tradition with complex grammar and vocabulary. However, there are several challenges to consider when developing sentiment analysis algorithms for Urdu, including the lack of annotated data and the presence of complex syntactic and semantic features (Mashooq, Riaz & Farooq, 2022; Khattak et al., 2021; Muhammad & Burney, 2023). To address these challenges, researchers have proposed multiple approaches for Urdu sentiment analysis, including the use of lexicons, machine learning algorithms, and deep learning techniques (Ghulam et al., 2019). A comprehensive framework for multi-modal sentiment analysis is given in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Comprehensive framework for our multi-modal sentiment analysis system, showing the processing pipelines for text, audio, and video, and the points at which fusion can occur.

The significance of this study lies in its contribution to bridging the gap between sentiment analysis and the Urdu language, particularly in multi-modal scenarios. By harnessing the synergistic power of visual, acoustic, and textual cues, the research endeavors to present a holistic understanding of emotions expressed across different modalities. This understanding can greatly influence applications such as social media analysis, customer service, and market research, facilitating better comprehension of user sentiments.

The article’s structure unfolds as follows: ‘Literature Review’ offers an in-depth exploration of existing literature in the domain of sentiment analysis, with a specific focus on Urdu sentiment analysis. ‘Dataset’ introduces the unique multi-modal dataset tailored to Urdu sentiment analysis. ‘Methodology’ outlines the proposed framework for multi-modal sentiment analysis in Urdu opinion videos. ‘Results’ presents the empirical results derived from individual modalities and their fusion. Lastly, ‘Conclusion’ concludes the article by summarizing key findings and delineating avenues for future research. Building upon the foundational concepts and motivations outlined in the introduction, we now delve into a comprehensive review of existing research, highlighting key developments and gaps in sentiment analysis, particularly for the Urdu language.

Literature review

Sentiment analysis, a fundamental aspect of understanding human emotions, has been a subject of study for decades. Early work in the 1970s by Ekman on universal facial expressions of emotion established that facial cues can reliably indicate certain emotions across cultures (Ekman, 1973). This groundwork paved the way for exploring emotions in other modalities such as speech, where acoustic characteristics like pitch and duration were found to convey affect (Datcu & Rothkrantz, 2014). In recent years, the integration of multiple modalities for emotion recognition has gained prominence. Gogate, Adeel & Hussain (2017) introduced a deep learning fusion approach combining text, audio, and video cues for deception detection, demonstrating the benefit of multi-modal input. Similarly, De Silva, Miyasato & Nakatsu (1997) suggested the untapped potential in combining audio and visual features for better emotion analysis, an idea later echoed in sentiment analysis research. Advancements extend to multilingual contexts as well. Pérez-Rosas, Mihalcea & Morency (2013) developed a multi-modal Spanish dataset, Multi-modal Opinion Utterance Dataset (MOUD), which combined audio, visual, and textual cues for sentiment analysis at the utterance level using SVM with 10-fold cross-validation. Poria et al. (2016) proposed a fusion approach amalgamating linguistic, acoustic, and visual features; their method outperformed individual modality models and surpassed a prior state-of-the-art by 20% on a benchmark dataset. The sentiment analysis landscape has also been explored for South Asian languages. Khan & Nizami (2020) developed the “Urdu Sentiment Corpus (v1.0)” comprising over 17,000 tokens and performed sentiment analysis using part-of-speech features. Sehar et al. (2021) focused on deep learning algorithms for Urdu sentiment analysis, showing improved accuracy when multiple modalities were leveraged. In Persian, Dashtipour et al. (2021) introduced a context-aware multi-modal framework that demonstrated how combining modalities yields improved accuracy. For Romanized forms of Urdu/Hindi (often used in social media), researchers have also made progress. Ghulam et al. (2019) employed recurrent neural networks to enhance sentiment analysis on Roman Urdu text. Mehmood et al. (2020) presented Transliteration-based Encoding for Roman Hindi/Urdu Text Normalization (TERUN), outperforming traditional phonetic normalization algorithms. Li et al. (2022) explored transfer learning for Roman Urdu sentiment analysis using an attention-based convolutional neural network (CNN), achieving improved classification accuracy. To facilitate research in low-resource languages like Urdu, tools and resources have started to emerge. Shafi et al. (2022) developed the “Urdu Natural Language Toolkit,” providing lexicons and processing tools that can aid sentiment analysis tasks in Urdu. Khattak et al. (2021) and Liaqat et al. (2022) provided surveys of sentiment analysis techniques for Urdu and highlighted the need for multi-modal approaches.

Despite rapid advancements in sentiment analysis for high-resource languages, Urdu sentiment analysis has remained predominantly text-focused, relying on modestly sized corpora while largely neglecting non-textual signals which are essential in contemporary user-generated video content. The absence of large, publicly available multi-modal datasets for Urdu has constrained the community’s ability to develop and benchmark comprehensive models. This scarcity has forced researchers to depend primarily on small, often proprietary, or domain-specific datasets. Existing resources mostly consist of text alone—frequently Roman Urdu scraped from social media—with minimal integration of acoustic or visual cues that capture the full spectrum of human sentiment.

Furthermore, most current Urdu sentiment classifiers are monolingual and seldom evaluated for cross-lingual transferability—a critical limitation considering that code-switching and borrowing from English and other South Asian languages are common in Urdu-speaking communities. Without explicit mechanisms for transfer learning or cross-lingual adaptation, these models may exhibit poor generalizability beyond their narrow training domains. Such limitations inhibit the deployment of Urdu sentiment tools in multilingual scenarios and weaken their robustness amidst linguistic diversity.

By addressing these gaps, our work introduces the first large-scale, open-access multi-modal corpus for Urdu sentiment analysis. We demonstrate that a fused deep learning approach not only enhances sentiment classification within Urdu but also generalizes effectively to English when retrained. Nonetheless, future research must further explore transfer learning, code-switching, and domain adaptation to build truly multilingual, robust sentiment analysis systems.

Having surveyed the current landscape and identified these limitations, we next describe our approach to addressing these challenges through the creation of a novel multi-modal Urdu dataset.

Dataset

A new Urdu multi-modal dataset was collected for this study, named MMSA-Urdu, containing opinion videos on a variety of topics including product reviews, movie reviews, political commentary, economic issues, sports discussions, and book reviews. YouTube was the main source of these videos, with some additional clips from social media platforms like X (formerly Twitter) and Facebook, where people often respond to arguments via video. We used keywords in both English and Urdu (with Urdu translations in parentheses) to search for relevant content on YouTube, such as:

My favorite product (میری پسندیدہ چیز)

My favorite book (میری پسندیدہ کتاب)

Movie reviews in Urdu (اردو میں فلمی جائزے)

The political scenario of Pakistan (پاکستان کا سیاسی منظرنامہ)

Public reaction to inflation in Pakistan (پاکستان میں مہنگائی پر عوامی ردِعمل)

Public reaction to inflation in India (بھارت میں مہنگائی پر عوامی ردِعمل)

Public reaction to petrol price hike in India/Pakistan (بھارت/پاکستان میں پیٹرول کی قیمتوں میں اضافے پر عوامی ردِعمل)

From the collected content, we selected videos where a speaker clearly expresses their thoughts. Unlike some prior datasets that use videos with a single fixed-camera speaker, we included videos even with multiple people in the frame, provided only one person was speaking at a time. In cases with multiple faces, we assumed the largest face in the frame corresponded to the speaker and focused on that individual for visual analysis. In total, we gathered 214 videos with speakers ranging in age from approximately 15 to 72 years. The videos varied in length from about 10 s up to 12 min, totaling over 6 h of footage. We segmented these videos into shorter utterances for analysis, resulting in 4,515 segments. Each segment was annotated with a sentiment label (Positive, Negative, or Neutral) and an intensity score (on a scale from −3 to 3, as described later). Detailed dataset statistics are shown in Table 1. The data, along with any relevant processing code, can be accessed at Zenodo: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14291010.

| Total number of videos | 214 |

| Total number of segments (utterances) | 4,515 |

| Segments labeled as positive | 2,208 |

| Segments labeled as negative | 2,099 |

| Segments labeled as neutral | 208 |

The MMSA-Urdu dataset is publicly available and comprises multiple data modalities. The video segments are provided in .mp4 format, ensuring compatibility and ease of use. Corresponding audio tracks are separately available in .mp3 format, allowing focused acoustic analysis. The spoken content transcriptions are stored as plain text files in .txt format, each aligned with its respective video segment. Sentiment labels and annotation data are organized in a tabular .csv file, facilitating straightforward integration with machine learning workflows. The total size of the dataset is approximately 6 GB, balancing content richness with practical download and storage considerations. This clearly defined dataset structure supports reproducibility and broad accessibility for researchers working on Urdu multi-modal sentiment analysis.

It is worth noting that while our dataset covers a range of topics, it exhibits certain biases related to linguistic and demographic diversity. Specifically, dialects or accents of Urdu spoken outside Pakistan, such as those prevalent in India or among diaspora communities, are not extensively represented. This dialectal imbalance may limit the model’s effectiveness on speakers using significantly different linguistic patterns. Additionally, female speakers are noticeably underrepresented compared to male speakers, which introduces gender imbalance that could impact the fairness and generalization of trained models across genders. These biases highlight the necessity for broader and more balanced data collection efforts in future work to improve the inclusivity, robustness, and real-world applicability of multi-modal sentiment analysis systems for Urdu. Despite these limitations, as the first multi-modal Urdu sentiment corpus of its kind, our dataset remains a valuable resource for advancing research in this area.

Ethical considerations

All videos in the dataset were sourced from publicly available online platforms and did not contain any private or sensitive content. This study exclusively utilized such publicly accessible videos and did not involve direct interaction with human subjects or the collection of any additional private data. Therefore, formal approval from an Institutional Review Board (IRB) or ethics committee was not required, in accordance with our institution’s policies.

We used official Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) (such as the YouTube Data API) and web scraping techniques in compliance with platform terms of service and privacy guidelines. No personally identifiable information beyond the speakers’ public online personas is included in our dataset. The dataset is released on Kaggle under an appropriate research-use license, ensuring that the rights of content creators are respected.

In our analysis and presentation of examples, we translate or transliterate utterances and avoid disclosing any names or specific personal details to protect the speakers’ identities, even though their faces appear in the visual modality. Since the videos are user-generated and already public, privacy concerns are considered minimal. We emphasize that the data is used solely for research on sentiment analysis and not for any form of surveillance or misuse. Overall, we have been mindful of cultural and ethical considerations throughout the data collection and sharing process.

With our dataset established, the following section details the methodological framework employed for extracting and analyzing multi-modal sentiment features from textual, acoustic, and visual data.

Methodology

Transcription

All videos were transcribed using an online tool (Transkriptor) to obtain text from the spoken content. The initial transcriptions were then proofread by three native Urdu speakers to correct errors. The Urdu language often incorporates words from other languages (especially English) in informal speech. For example, (ایکسپیکٹکررہاتھاکہیہباکسآفسپےبیٹرپرفارمکرےگی) (transliterated: “expect kar raha tha kay yeh box office pe better perform karay gi,” meaning “I was expecting that it would perform better at the box office”) mixes English and Urdu. In many text processing approaches, foreign words are removed during preprocessing. However, in our case removing the English words would alter the meaning of the sentence. Therefore, we opted to keep such words in the transcripts and, when necessary, translated them into Urdu to maintain the context.

Segmentation

Each video’s transcription was saved in a spreadsheet with the filename matching the video file. For each spoken utterance, we recorded its start time and end time in the spreadsheet. These timestamps were then used to segment the videos into individual utterance clips using the moviepy library. The audio track was also extracted for each segment using the same library. Through this process, the continuous videos were broken down into 4,515 segments aligned with the annotated utterances.

Annotation

Three native speakers with postgraduate degrees in Urdu were hired as annotators. They independently labeled each segment’s text, audio, and video with sentiment scores on a scale from −3 to 3, where −3 represents extremely negative sentiment, 3 represents extremely positive sentiment, and 0 indicates neutral sentiment. An example of annotated utterances is provided in Table 2. The inter-rater agreement, assessed using Fleiss’ Kappa (Fleiss, 1971), was 0.937, which is considered highly reliable.

| Utterance (Urdu) | English translation | Polarity | Label |

|---|---|---|---|

| کاسٹنگ سب سے زیادہ اچھی تھی | The casting was the best among all | 3 | Positive |

| صرف دیکھنے میں ہینڈسم نہیں ہے یا اس میں جو فزیکلی محنت کی ہے ایکٹنگ وائز بھی بہت اچھا ہے | He is not only handsome in appearance and dedicated to his physical fitness but also demonstrates excellent acting skills. | 2 | Positive |

| جو فلم کا میوزک ہے جو سونگز ہیں وہ ٹھیک ٹھاک سے ہیں | The film’s music, particularly its songs, is quite good. | 1 | Positive |

| اور اس کی ریٹنگ کی اگر بات کی جائے تو میں اس کو تھری آؤٹ آف فائیو دوں گا | As for the rating, I would give it three out of five. | 0 | Neutral |

| پھر سیکنڈ ہاف جو ہوتا ہے انٹرول کے بعد اکثر فلم ہاتھ سے نکلتی ہوئی محسوس ہوتی ہے | Subsequently, during the second half—especially after the intermission—the film frequently feels like it’s getting out of hand. | −1 | Negative |

| کیونکہ سکرپٹ کہانی بہت بورنگ تھی | Because the script and story were very boring. | −2 | Negative |

| سپیشلی مانا ویج کے ساتھ جو اس فلم میں کیا گیا ہے وہ بہت ہی بکواس ہے | Specifically, what was done with the character Mana Waj in this movie is utterly nonsensical. | −3 | Negative |

Although the overall agreement was very high, a small subset of utterances exhibited disagreement among annotators. These disagreements primarily occurred in segments with subtle or mixed sentiment, especially near the boundaries between neutral and mild positive or negative sentiments. Ambiguity often arose due to implicit emotional cues, sarcasm, or varying contextual interpretations. To finalize labels, majority voting was applied, recognizing that a portion of the dataset inherently contains subjective ambiguity. This analysis highlights the complex and nuanced nature of sentiment annotation in multi-modal Urdu opinion videos, and underscores the importance of multi-modal cues in resolving such ambiguities.

For consistency in analysis, the numeric scores were ultimately consolidated into three categories. Any score greater than 0 was mapped to Positive, any score less than 0 to Negative, and a score of exactly 0 to Neutral. (In cases where intensity was noted, a score of 1 vs. 3 still fell under the same Positive category, but the magnitude indicated the strength of sentiment; however, our classification task treats the labels as categorical.) The annotators also marked each segment as subjective or objective. Objective expressions conveyed factual information about entities, events, or attributes, whereas subjective expressions represented personal opinions, feelings, or attitudes (Liu, 2010). Table 3 shows examples distinguishing a factual statement from a personal opinion. We used majority voting among the three annotators to finalize the sentiment label and subjectivity tag for each segment.

| Utterance text (Translated) | Type | Sentiment label |

|---|---|---|

| “This phone has good battery life.” | Objective statement | Positive (implied) |

| “I did not like the ending of this movie.” | Subjective opinion | Negative |

Textual modality processing

For the textual modality, we employed a CNN model to perform sentiment classification on the transcribed utterances. We chose a CNN architecture inspired by Kim & Jeong’s (2019) work on sentence classification due to its effectiveness in extracting local n-gram features and sentiment-bearing phrases. In our implementation, each word in the transcript was first converted into a 300-dimensional vector using pre-trained FastText word embeddings (Joulin et al., 2016) (version 0.9.2) trained on large Urdu corpora. Using pre-trained embeddings helps in handling Urdu’s rich morphology and out-of-vocabulary words. We kept these embeddings fixed during training (fine-tuning them on our dataset did not yield significant improvement, given the dataset size).

The CNN architecture consists of 11 layers in total: four convolutional layers, four max-pooling layers (each following a convolution), and three fully connected layers. We employed multiple filter sizes (e.g., three, four, and five words in width) for the convolutional layers to capture patterns of different lengths in the text. These convolutional filters slide over the embedded word sequence to detect local patterns indicative of sentiment (for example, negations or strongly positive/negative phrases). Max-pooling layers were applied to the feature maps to retain the most salient features from each filter and reduce dimensionality. The fully connected layers at the end then learned higher-level combinations of these features and mapped them to the sentiment classes. Hyperparameters such as the number of filters, learning rate, and regularization were tuned based on validation performance. Overall, this CNN text model effectively learned representations that map input sentences to the Positive, Negative, or Neutral sentiment classes. It captured both local features (through convolution) and global sentiment tendencies (through the dense layers), enabling accurate sentiment predictions from the textual modality alone.

Acoustic modality processing

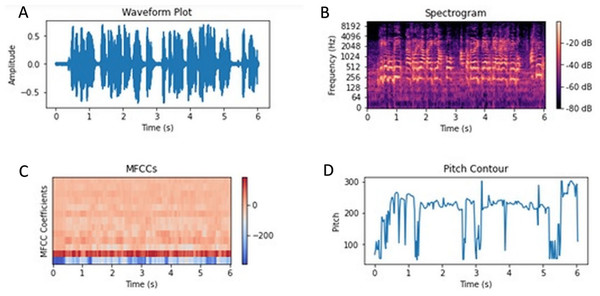

In the audio modality, we leveraged the Librosa library (version 0.8.1) (McFee et al., 2015) to extract a rich set of acoustic features that could correlate with sentiment. Librosa provides comprehensive tools for analyzing audio signals. We computed features such as Mel-frequency cepstral coefficients (MFCCs), intensity (energy), pitch (fundamental frequency), and loudness from each audio segment (Babu, Nagaraju & Vallabhuni, 2021). An illustrative example of the audio feature set is shown in Fig. 2. MFCCs are particularly valuable for audio-based sentiment analysis because they capture the spectral characteristics of speech, relating to the timbre of the speaker’s voice. By condensing the frequency content of short audio frames into a set of coefficients, MFCCs provide a compact representation that can reflect emotion-related vocal qualities (for example, a tense or excited voice may have distinct spectral patterns) (Luo, Xu & Chen, 2019).

Figure 2: Audio sentiment analysis—Illustrative example of audio features (MFCCs, pitch, intensity) extracted from an utterance.

Distinct sentiment expressions often have characteristic acoustic patterns; for instance, an excited positive utterance may exhibit higher pitch variation and intensity, whereas a negative or neutral utterance might have lower energy and a flatter tone. (A) Waveform (amplitude vs. time) highlighting energy distribution and pauses. (B) Log-scaled spectrogram (frequency vs. time) showing intensity bands and formant structure. (C) MFCC heatmap summarizing the spectral envelope across time. (D) Pitch (F0) contour capturing intonation; larger excursions typically reflect more excited/positive affect, while flatter or lower F0 is common in neutral/negative tone.In addition to MFCCs, we included features representing intensity and loudness (which indicate how energetically or loudly something is said) and pitch (which reflects the intonation). These features can signal emotional intensity and tone—e.g., a raised voice with high intensity and pitch might indicate excitement or anger, whereas a low, flat tone might indicate sadness or a neutral mood. The combination of these features gives a comprehensive representation of the audio signal, enabling our model to capture nuances such as sarcasm (often detectable through intonation), excitement, or frustration in the speaker’s voice (García-Ordás et al., 2021). Indeed, MFCCs are among the most frequently used features in speech emotion analysis, as they succinctly represent the audio spectrum.

Leveraging Librosa’s feature extraction capabilities yielded a rich set of descriptors for each audio segment. These features served as inputs to our audio sentiment classification model (a feed-forward neural network) that learns to map acoustic patterns to sentiment labels. By combining spectral features (MFCCs) with prosodic features (pitch, loudness, intensity), we provided the model with multiple cues, improving its ability to detect emotion-related characteristics in the audio. This forms a robust framework for audio-based sentiment analysis within our multi-modal system.

Visual modality processing

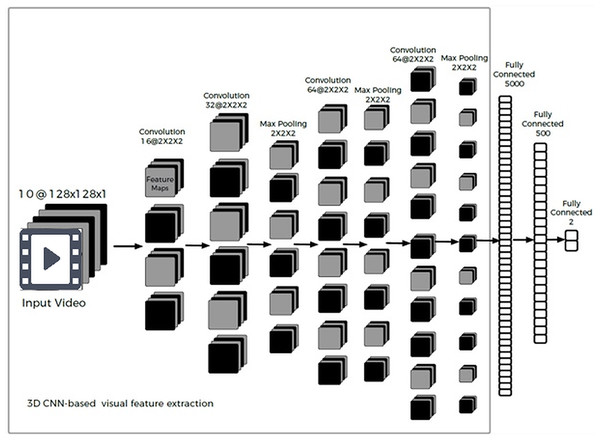

For visual feature extraction from the video segments, we employed three-dimensional convolutional neural networks (3D-CNNs). The motivation for using a 3D-CNN was its ability to extract both spatial and temporal features from a sequence of video frames. Unlike a 2D CNN that processes individual images, a 3D-CNN processes a stack of consecutive frames, thereby capturing inter-frame motion cues (e.g., facial muscle movements over time) in addition to intra-frame features (facial expressions in each frame). Our 3D-CNN model implemented a 10-layer architecture, as depicted in Fig. 3. The input to the network is a sequence of video frames rather than a single image.

Figure 3: Visual feature extraction using a 3D-CNN architecture.

The network takes a sequence of frames as input (we use 10 grayscale frames of size 128 128), and through 3D convolutions and pooling across both spatial and temporal dimensions, it learns features capturing facial expressions and their motion. The output is a feature representation of the video segment’s visual sentiment cues.In our implementation, we standardized each video segment to a sequence of ten frames (converted to grayscale, 128 128 pixels each) for analysis. These ten frames were uniformly sampled over the duration of the segment—covering the beginning, middle, and end—to ensure that we capture any sentiment-relevant expressions that occur at different times in the utterance. Uniform sampling of ten frames ensures a balanced and comprehensive view of the entire video segment, capturing sentiment cues that may occur at any point. This approach avoids the bias and potential oversight of important expressions that can occur with dynamic sampling methods. It provides a simple, consistent, and computationally efficient way to cover the temporal evolution of facial expressions. We found that uniform sampling provided a better overall representation than picking frames from only a specific part of the segment.

We did not perform face cropping or alignment (the entire frame was fed to the network); however, because we focused on videos where one person is speaking and is usually prominent in the frame, the 3D-CNN can learn to attend to the facial region (indeed, visualizing intermediate feature maps showed many filters responding strongly to the face area). Within the 3D-CNN, the first convolutional layer comprised 16 feature maps with a kernel (height, width, depth across frames). The second convolutional layer had 32 feature maps (also kernel), followed by a max-pooling layer of size . The third convolutional layer had 64 feature maps ( kernel), followed by another max-pooling. A fourth convolutional layer with 64 feature maps ( kernel) was then applied, followed by a final pooling layer. These convolution and pooling operations progressively reduced the spatial dimensions while increasing the depth of feature maps, thereby encoding facial features and movements.

Importantly, the temporal dimension (frames) is also convolved and pooled, which enables the network to capture dynamics such as the onset of a smile or frown, or quick head movements. Our frame selection strategy (10 uniformly sampled frames) means the model observes the evolution of expressions across the segment. For example, if a speaker delivers a sarcastic remark with a straight face until a slight smirk at the end, some of the ten frames will likely capture that smirk. If we had taken only a single frame or only contiguous frames in a short window, we might miss such cues. This approach does increase computational load, but it provides the model a broader temporal context. The 3D-CNN outputs were flattened and passed through a series of fully connected layers (of sizes 5,000 and 500) to distill the learned features, and finally to an output layer for classification.

The visual model produces one of the three sentiment classes (Positive, Neutral, Negative) for each segment when trained on its own. We found that the visual modality by itself achieved a classification accuracy of about 69% on our test set, outperforming the audio modality but not as high as the text modality. This indicates that facial expressions and visual cues are indeed informative for sentiment (e.g., smiles generally indicating positive sentiment, frowns or head shakes indicating negative sentiment), but they may sometimes be ambiguous without context (for instance, a polite smile while delivering negative feedback can confuse a naive classifier). The strength of the 3D-CNN is in capturing the temporal dynamics of expressions—rapid changes or subtle microexpressions that static image analysis would miss. Although 3D-CNNs are computationally heavier than 2D CNNs, our results show that the temporal information they capture is valuable for sentiment analysis.

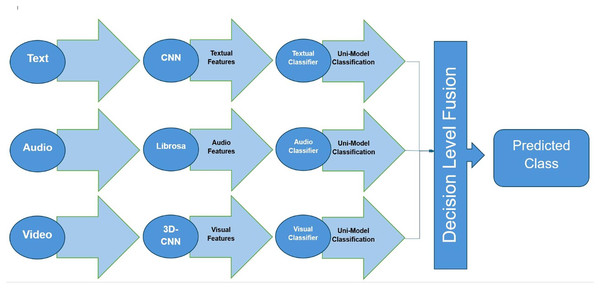

Multi-modal fusion strategies

While unimodal sentiment analysis can yield reasonable results, integrating multiple modalities provides a more robust understanding of sentiment. We explored two primary fusion techniques: feature-level (early fusion) and decision-level (late fusion). In feature-level fusion, features extracted from different modalities are concatenated into a single feature vector, which is then input to a classifier (Shan, Gong & McOwan, 2007). In decision-level fusion, each modality is first used to produce an individual sentiment prediction (for example, through separate classifiers), and then those predictions (or confidence scores) are combined—e.g., via weighted voting or a meta-classifier—to produce the final decision (Cambria, Livingstone & Hussain, 2013).

Both approaches leverage complementary information from multiple sources; the choice between them depends on the specific problem and data characteristics. In our framework, we implemented both strategies. For feature-level fusion (early fusion), after obtaining the intermediate features from the text CNN (the last hidden layer before the classification output), the audio model, and the visual 3D-CNN, we concatenated these feature vectors into one long vector representing the segment’s multi-modal characteristics. This combined vector was then fed into a feed-forward network (we used one hidden layer of 128 neurons with Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation) followed by a softmax output layer to predict the sentiment class. Essentially, the model learns to weigh and mix features across modalities—for example, it might learn that when textual cues are ambiguous, certain audio tones or facial expressions can disambiguate the sentiment. For decision-level fusion (late fusion), we allowed each modality-specific classifier to first produce its own prediction for a segment.

We then combined these predictions using a simple voting scheme: if at least two modalities agreed on the sentiment label, that label was chosen as the final output; in the rare case where all three modalities disagreed, we found that trusting the text modality (which was most accurate alone) yielded the best outcome. We also experimented with a weighted voting (assigning slightly higher weight to text predictions and lower to audio/visual), but the results were similar, and we opted for the simpler majority vote for clarity. Figure 4 illustrates the decision-level fusion process in our system. This approach allows each modality-specific model to specialize in its domain and contributes its judgment, and the fusion mechanism then aggregates these judgments. We found that decision-level fusion slightly outperformed feature-level fusion in our experiments, although both improved significantly over any single modality.

Figure 4: Multi-modal fusion at the decision level.

Each modality (text, audio, video) produces an independent sentiment prediction, which are then combined (e.g., by majority voting or a meta-classifier) to yield the final sentiment decision. In our framework, this late fusion strategy proved slightly more effective than early fusion.Computational complexity and inference times

To evaluate the practicality of deploying our multi-modal sentiment analysis framework in real-world applications, we analyzed the computational complexity and inference times of our models. The experiments were performed using an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3080 Ti GPU and an Intel Core i7 CPU.

Training Time: On the RTX 3080 Ti, training the full multi-modal model (with all three modalities) took approximately 2 h per epoch, and we trained for a total of 10 epochs to reach convergence. In contrast, training on the CPU was significantly slower, taking more than 12 h per epoch.

Inference Time: The average inference time per segment was around 90 ms on the GPU and about 400 ms on the CPU. These speeds indicate that our model can process new data in near-real-time on modern hardware, making it feasible for applications such as live sentiment monitoring (especially when a GPU is available).

Memory Usage: During training, GPU memory usage peaked at roughly 10 GB, whereas inference required around 3 GB of GPU memory. These requirements are manageable on contemporary high-end hardware. For deployment on devices with limited resources, techniques like model pruning or quantization could be considered to reduce the model’s footprint.

In summary, while our framework is computationally intensive during training (particularly due to the 3D-CNN and the need to handle three modalities), its runtime performance (especially with GPU acceleration) is suitable for practical use. The efficient inference capability means it could be integrated into systems that require on-the-fly sentiment analysis of multimedia content.

Equipped with a robust methodology, we now present the experimental results, demonstrating the effectiveness of our multi-modal sentiment analysis approach on the curated Urdu dataset.

Results

In this section, we present the experimental results of our Urdu multi-modal sentiment analysis framework, along with comparative evaluations. As an initial preprocessing step, we filtered the data to focus on utterances that carry subjective sentiment content. Any objective utterances (factual statements without sentiment) were removed, ensuring that the model was trained and evaluated primarily on expressive, opinionated segments. For training and evaluation, we partitioned the dataset into a training set, validation set, and test set, approximately in a 70%/10%/20% ratio. The splits were stratified to preserve the proportion of positive, negative, and neutral samples in each subset. We trained our models on the training set and tuned hyperparameters (e.g., learning rate, number of epochs, and regularization) using the validation set. Once the model configuration was finalized, we retrained the model on the combined training+validation data and evaluated it on the held-out test set to obtain the final results. To ensure the robustness of our findings, we also performed a 5-fold cross-validation across the dataset. The model’s accuracy was consistent across different folds (standard deviation of accuracy was about 1%), indicating that our performance is stable and not an artifact of a particular train-test split.

Additionally, we conducted experiments to assess the model’s robustness under various conditions. For instance, we introduced moderate background noise into the audio of test segments (simulating a noisy environment) and observed only a slight drop in accuracy (approximately 2% absolute decrease). This suggests that our acoustic feature set (MFCCs, pitch, loudness) and audio model are fairly resilient to noise. We also examined performance across different speaker demographics: the model’s accuracy on segments spoken by female speakers was roughly on par with that on male speakers (within 2% difference), despite the training data containing somewhat fewer female examples. This indicates that the model generalizes across genders reasonably well, though future data collection with more balanced gender representation could further ensure fairness. Overall, these tests demonstrate that our multi-modal framework maintains strong performance even when faced with moderate audio noise or shifts in speaker characteristics.

The results achieved through the proposed sentiment analysis approach are summarized in Table 4. This table presents a detailed performance evaluation for each modality alone and for various combinations of modalities using both feature-level (early) fusion and decision-level (late) fusion. We report accuracy as the primary evaluation metric since it provides an intuitive measure of the model’s overall ability to correctly predict sentiment labels. Accuracy is widely used in sentiment analysis evaluations and, given the roughly balanced distribution of positive and negative classes in our dataset, it serves as a reliable indicator of performance across classes (Wankhade, Rao & Kulkarni, 2022). (Neutral examples form a smaller portion of the data, but we include them in the evaluation and analyze class-specific performance below.) As shown in Table 4, the fusion of modalities generally improves sentiment classification accuracy compared to single-modality models. The textual modality alone was the strongest individual performer (88.06% accuracy), reflecting that much of the sentiment information is explicitly conveyed in words. The visual modality by itself reached 68.76%, and the acoustic modality 62.38%, which aligns with our expectation that tone and facial expressions carry sentiment but are often subtler than explicit verbal content. When combining modalities, we observed clear gains: for instance, fusing text with audio (T + A) improved accuracy to 88.80% (feature-level) and 89.55% (decision-level), and fusing text with video (T + V) reached about 90%. Even the combination of audio + visual (A + V)—which lacks the text channel—performed significantly better (up to 80.60% with early fusion) than audio or video alone, indicating that these non-verbal cues together can yield a decent sentiment prediction by complementing each other. The highest accuracy was achieved by fusing all three modalities, with decision-level fusion yielding 91.18%, slightly higher than feature-level fusion at 90.45%. These results underscore that each modality contributes unique information and that our fusion strategies effectively harness these complementary cues to improve overall performance. The corresponding 95% confidence intervals further demonstrate that decision-level fusion provides statistically significant gains over unimodal approaches while maintaining tighter confidence intervals, highlighting its robustness and reliability.

| Modality combination | Feature-level fusion | Decision-level fusion | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 95% CI | Accuracy | 95% CI | |

| Textual (T) only | 88.06 | 2.11 | 88.06 | 2.11 |

| Acoustic (A) only | 62.38 | 3.16 | 62.38 | 3.16 |

| Visual (V) only | 68.76 | 3.02 | 68.76 | 3.02 |

| T + A | 88.80 | 2.06 | 89.55 | 1.99 |

| T + V | 89.30 | 2.02 | 90.10 | 1.95 |

| A + V | 80.60 | 2.59 | 70.50 | 2.98 |

| T + A + V | 90.45 | 1.92 | 91.18 | 1.85 |

Note:

95% CI calculated using: , where = accuracy proportion, = 903 test segments.

In addition to accuracy, we evaluated our best model (the decision-level fusion of T + A + V) using precision, recall, and F1-score to ensure it performs well across all classes. Table 5 presents these detailed class-wise performance metrics. The numbers indicate balanced error rates and little bias toward neutral class. For the Positive class, precision and recall are approximately 91% and 90%, respectively. The Negative class shows precision and recall around 88% and 89%, while the Neutral class, as expected, is the most challenging with an F1-score near 82%, likely due to its subtler sentiment and smaller sample size. Misclassification often occurred between mild sentiment and neutral cases.

| Modality | Sentiment class | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1-score (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Textual (T) | Positive | 89 | 87 | 88.0 |

| Negative | 86 | 88 | 87.0 | |

| Neutral | 75 | 68 | 71.3 | |

| Acoustic (A) | Positive | 65 | 68 | 66.5 |

| Negative | 64 | 66 | 65.0 | |

| Neutral | 58 | 52 | 54.9 | |

| Visual (V) | Positive | 74 | 77 | 75.5 |

| Negative | 70 | 72 | 71.0 | |

| Neutral | 64 | 58 | 60.9 | |

| T + A (Fusion) | Positive | 90 | 88 | 89.0 |

| Negative | 87 | 89 | 88.0 | |

| Neutral | 78 | 72 | 74.9 | |

| T + V (Fusion) | Positive | 91 | 89 | 90.0 |

| Negative | 88 | 90 | 89.0 | |

| Neutral | 80 | 75 | 77.4 | |

| T + A + V (Fusion) | Positive | 91 | 90 | 90.5 |

| Negative | 88 | 89 | 88.5 | |

| Neutral | 85 | 80 | 82.0 |

The strong precision and recall for the positive and negative classes—which constitute the majority of the data—demonstrate the model’s effectiveness in capturing sentiment polarity. Table 6 provides a comparative analysis of our proposed framework against other available techniques for sentiment analysis in Urdu. It should be noted that most existing works on Urdu sentiment analysis are text-only and often focus on either Roman Urdu or formal Urdu text, given the lack of multi-modal datasets. For example, Nawaz et al. (2020) reported 80% accuracy using an extractive text summarization approach for sentiment, Agarwal, Yadav & Vishwakarma (2019) achieved approximately 78% accuracy in a multi-modal context (text + audio) on a code-mixed Hindi-English dataset (adapted here for rough comparison), and Mukhtar, Khan & Chiragh (2018) and Mahmood et al. (2020) reported lower accuracies using lexicon-based and deep learning methods on Urdu text, respectively. Our model’s accuracy of 91.18% surpasses these, highlighting the benefit of our fused multi-modal approach and the introduction of a tailored dataset. It also emphasizes that multi-modal analysis can substantially improve sentiment recognition performance in Urdu content over text-only methods, especially when dealing with expressive opinionated videos.

| Model (Reference) | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|

| Proposed multi-modal model (Ours) | 91.18 |

| Nawaz et al. (2020) (text-based) | 80.00 |

| Agarwal, Yadav & Vishwakarma (2019) (multi-modal Hindi/English) | 78.08 |

| Mukhtar, Khan & Chiragh (2018) (lexicon-based Urdu) | 62.07 |

| Mahmood et al. (2020) (Roman Urdu, deep learning) | 57.00 |

Evaluation on standard benchmark dataset

To further validate the effectiveness and generalizability of our multi-modal sentiment analysis framework, we applied it to the widely-used CMU-MOSI multi-modal sentiment analysis dataset. The CMU-MOSI dataset contains short video clips (monologue utterances) in English annotated with sentiment scores, and it serves as a common benchmark for evaluating multi-modal sentiment analysis models. We retrained our entire framework on the CMU-MOSI data while maintaining the same architecture and fusion strategies used in our original Urdu experiments. Since CMU-MOSI is an English-language dataset, we substituted our text model’s embedding layer with 300-dimensional English FastText embeddings (keeping the CNN architecture identical) to handle the English transcripts. Aside from this embedding change, no modifications to the model were required. We processed the MOSI videos in a similar manner to our own: each video clip (utterance) comes with a transcript, and we extracted audio features and video frames using the same procedures. The original MOSI sentiment annotations range from −3 to +3 (a continuous scale); we mapped these to our three sentiment classes by considering any rating > 0 as Positive, any rating < 0 as Negative, and a rating of 0 as Neutral, to align with our classification setup. We then trained our multi-modal model from scratch on the MOSI training set and evaluated it on the standard MOSI test set.

Results on CMU-MOSI dataset

• Accuracy: On CMU-MOSI, our model achieved an accuracy of 86.7%, which is comparable to state-of-the-art results for multi-modal sentiment classification on this benchmark.

• Precision/Recall/F1-score:

-

–

Precision: 85.7

-

–

Recall: 89.0

-

–

F1-score: 87.3

-

These results demonstrate the robustness and language-independence of our framework. Despite being developed for Urdu, the model transferred effectively to an English dataset after retraining. If our model had overfit idiosyncrasies of the Urdu data, we would expect it to perform poorly on MOSI; however, its strong performance on MOSI suggests that it learned generally useful patterns of how textual, audio, and visual cues correlate with sentiment. In other words, the model’s design and training approach can extend beyond a single language, provided that we have corresponding modality data and appropriate embeddings. This cross-dataset evaluation gives us confidence that our framework could be applied to other languages or multilingual scenarios with suitable training data. Overall, the MOSI experiment reinforces that multi-modal sentiment analysis frameworks like ours have broad applicability. It provides a sanity check that our approach is not narrowly tailored to one dataset or language, but rather captures fundamental aspects of multi-modal sentiment expression.

Error analysis

While our multi-modal model achieves high overall accuracy, examining the cases where it fails can provide insights into its limitations and potential areas for improvement. We performed a detailed error analysis on our Urdu test set, focusing on the segments that were misclassified by the fused model. Out of 903 test segments, the model misclassified approximately 35 instances (about 3.9%, which aligns with the overall error rate given the 91.18% accuracy). We categorized these errors based on the apparent primary cause and identified several common patterns:

Textual misinterpretation: In some cases, the textual content of the utterance led the model astray. A common scenario was sarcasm or ironic statements where the literal text is positive but the intended sentiment is negative (or vice versa). For example, one segment’s transcript was “Yeh kafi interesting tha, haan bhai, bohat zabardast” (translated: “Yeah, this was quite interesting, oh yeah, really amazing”) said in a clearly sarcastic tone. The ground truth label was Negative, but the model predicted Positive, likely because it took the positive words (“interesting,” “amazing”) at face value and didn’t fully catch the sarcasm through the other modalities. This indicates a limitation in understanding sarcasm or tone purely from text; improving the model’s handling of such cases might involve giving more weight to audio/visual cues (tone, smirk) or using a specialized sarcasm detector.

Audio misinterpretation: Some errors were primarily due to misleading audio cues. For instance, in one misclassified segment, there was loud upbeat background music and the speaker’s voice had a cheerful tone, but the actual content was a complaint (negative sentiment). The model predicted Positive, seemingly influenced by the “happy” acoustic atmosphere. In such cases, the presence of background music or an unusual tone can confuse the audio model. This suggests that incorporating some form of speaker voice isolation (to ignore background sounds) or training on more data with background noise could help. It also underscores the importance of cross-checking with text content—had the model weighted the negative words more, it might have overridden the misleading audio.

Visual misinterpretation: In a few instances, the visual cues led to mistakes. For example, one speaker maintained a neutral facial expression while delivering very negative verbal content; the model, seeing a lack of frown or anger on the face, predicted Neutral whereas the correct label was Negative. In another case, a speaker had a habit of smiling or chuckling while criticizing (a form of nervous laughter or social masking), and the model incorrectly leaned towards a positive/neutral prediction because it “saw” a smile. These cases highlight that facial expressions can sometimes be deceiving or person-dependent. The model might benefit from learning more person-specific baselines (e.g., that this particular speaker often smiles even when negative) or from combining modalities more intelligently (realizing “if text is strongly negative but face is smiling, perhaps it’s sarcasm or a polite smile”).

Modality conflict: There were cases where different modalities gave conflicting signals, and the model chose the wrong one to trust. For instance, consider an utterance where the text is mildly positive, but the tone is dripping with sarcasm (truly negative sentiment). If the model were to believe the text over the audio, it would err. We observed instances of this: the text contained polite or positive words, the audio/visual indicated scorn or negativity, and the model sometimes got confused. Although our fusion scheme generally worked, these edge cases suggest we might improve by using a more sophisticated fusion method—perhaps an attention mechanism that can dynamically decide which modality is more reliable for a given segment (e.g., if it detects a discrepancy, rely more on audio/visual which might carry sarcasm cues).

Ambiguous or borderline cases: A small number of errors were on segments that were genuinely hard to label even for humans—e.g., very neutral statements that could be interpreted slightly positively or negatively depending on context, or vice versa. In such borderline cases, the model’s prediction might differ from the annotator’s label, but it’s not obviously “wrong” in a practical sense. For example, a segment saying “It was okay, I guess” was labeled Neutral by annotators but predicted as slightly Positive by the model. These are minor and expected discrepancies; handling them might require more nuanced classes or context, but for our three-class setup, a small confusion around the neutral boundary is acceptable.

By analyzing these errors, we gained several insights. First, sarcasm and irony remain challenging for our model; explicitly modeling them (possibly by detecting vocal tone patterns or using textual cues like hyperbolic words) could be a future improvement. Second, background noise or irrelevant audio features can mislead the model, so integrating a noise-robust training strategy or preprocessing step could help. Third, the model could benefit from a more dynamic fusion mechanism to handle conflicting modality inputs—future work could explore trainable fusion with attention or gating that learns to trust one modality over another in certain contexts (for instance, if audio tone strongly contradicts text, it might indicate sarcasm). In light of these error patterns, we propose several refinements: incorporating a sarcasm detection component, augmenting training data with more varied background conditions (to teach the model to focus on the speaker’s voice), and exploring advanced fusion architectures. We discuss these ideas further in the Future Work section. The error analysis ultimately provides a roadmap for how the model can be improved to handle the nuanced and complex nature of human communication.

Conclusion

Our research introduces a robust Urdu multi-modal sentiment analysis framework that combines textual, acoustic, and visual cues to comprehensively determine sentiment in opinionated video content. By leveraging advanced deep learning techniques and careful preprocessing, we constructed individual sentiment classifiers for each modality and then fused their outputs. The fusion of modalities significantly enhanced prediction accuracy, reaching an impressive 91.18% when textual, acoustic, and visual cues were used together.

Our framework, designed for Urdu opinion videos, outperforms comparable unimodal approaches and sheds light on sentiment dynamics in multimedia content (see Table 4 for performance gains with fusion). The curated dataset of 214 videos (4,515 annotated segments) that we developed is a valuable contribution on its own, providing the community a resource for multi-modal analysis in the low-resource Urdu language. The success of our model in capturing sentiment from multiple channels demonstrates its potential usefulness across domains—ranging from analyzing social media video posts to interpreting user sentiments in video-based customer feedback. The strong results on our dataset, along with successful evaluation on the English CMU-MOSI benchmark, validate the efficacy and generalizability of our approach. This indicates that the model learned meaningful patterns that transcend language-specific cues, highlighting its contribution to the broader field of multi-modal sentiment analysis.

In practical terms, the ability to integrate text, audio, and visual analysis means our system can be applied to realistic scenarios where people express opinions in front of a camera, unlocking richer understanding than text analysis alone. Our multi-modal sentiment analysis framework has potential real-world applications in various domains. For example, it could be integrated into social media monitoring tools to automatically gauge public sentiment from user-generated videos on platforms like YouTube and Facebook. Companies could leverage it to analyze customer review videos for products, extracting not just what is said but also how it is said (tone of voice, facial expressions) for deeper consumer insights. In the media and entertainment industry, the system could help in content recommendation or trend analysis by understanding viewer reactions in video blogs or review channels (e.g., identifying segments of high positive or negative reaction). In education, educators might analyze student presentation videos or video feedback to assess engagement or confusion through students’ vocal tone and facial cues. Similarly, in healthcare, therapists could use such a framework to monitor patient video diaries or telemedicine sessions for signs of emotional distress or improvement over time. These examples illustrate the broad applicability of our Urdu sentiment analysis framework (and similar multi-modal systems for other languages) in turning rich multimedia data into actionable sentiment insights.

Future work

While our research has made significant strides in Urdu multi-modal sentiment analysis, there are several avenues for future exploration and enhancement:

-

Sarcasm and irony detection: One of the challenges identified is the detection of sarcasm or ironic tone, which often requires nuanced understanding across modalities. Future work could involve training a dedicated sarcasm detection module or incorporating transformers with multi-head attention that can better capture context and tone subtleties. This would help the model avoid misclassifying sarcastic positive words as genuine positivity.

-

Fine-grained emotions: Extending the classification beyond coarse sentiment to a richer set of emotion classes (happiness, anger, sadness, etc.) could make the system more informative. This would likely require more detailed annotations (perhaps using an emotion ontology) and possibly more data, but it would allow the model to capture intensity and specific emotion nuances better than a three-class sentiment label.

-

Cross-lingual and code-switching scenarios: In real-world Urdu content, speakers often mix Urdu with English or other languages (code-switching). Adapting our framework to handle code-switched text (for example, using multilingual embeddings or detecting language shifts in transcripts) would increase its applicability. Additionally, since our approach transferred well to English (MOSI), we could explore building a single model that handles multiple languages by combining training data (multilingual multi-modal sentiment analysis).

-

Adaptive fusion strategies: Our current fusion approach is fixed (early concatenation or majority voting). Future research could explore trainable fusion techniques, such as an attention-based fusion layer that learns to weight each modality’s contribution dynamically for each input. This could help in cases of modality conflict—e.g., learning when to trust the audio over the text and vice versa.

-

Data augmentation and generalization: We plan to augment our dataset further, possibly by generating synthetic variations (adding noise, varying pitch, shifting video brightness, etc.) to make the model even more robust to real-world noise and variability. We also aim to collect more data covering different dialects of Urdu and a more balanced gender distribution, as noted earlier, to address any bias and improve generalization.

-

Real-time deployment and user feedback: Implementing the model in a real-time system (e.g., a live sentiment “dashboard” for streaming video comments) and collecting user feedback on its predictions could provide practical insights. Such deployment could reveal new challenges (like processing speed constraints, or cases where users disagree with the model’s sentiment interpretation) that would guide further refinement.

-

Multi-modal explanation: Another intriguing direction is to make the model’s predictions explainable. For instance, highlighting which words, acoustic signals, or facial expressions contributed most to a particular sentiment prediction could build user trust and help debug the model. Techniques like attention visualization or gradient-based saliency in multi-modal models would be valuable here.

By pursuing these directions, we can continue to refine and expand the capabilities of multi-modal sentiment analysis in Urdu and beyond. The ultimate goal is to create systems that understand human sentiment as naturally and accurately as possible, across languages and communication channels, thereby bridging the gap between human emotional expression and machine interpretation.