A systematic literature review of lightweight YOLO models for object detection

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Consolato Sergi

- Subject Areas

- Artificial Intelligence, Computer Vision, Data Mining and Machine Learning, Visual Analytics, Neural Networks

- Keywords

- Lightweight YOLO, Object detection, Resource-constrained, SLR

- Copyright

- © 2025 Wang et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2025. A systematic literature review of lightweight YOLO models for object detection. PeerJ Computer Science 11:e3357 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3357

Abstract

Object detection is a core task in computer vision, and the You Only Look Once (YOLO) family remains a preferred choice for real-time applications. With increasing demand to deploy detectors on resource-constrained devices, many researchers have proposed lightweight YOLO variants. This systematic literature review synthesizes peer-reviewed studies on lightweight YOLO models published from 2016 to 2025. We performed reproducible searches in Scopus and Web of Science, screened records using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA), and applied a 12-item quality assessment to select 103 peer-reviewed journal and conference articles for detailed analysis. We classify primary lightweighting strategies—pruning, quantization, knowledge distillation, and lightweight network architectures—and evaluate their trade-offs in accuracy, latency, model size, and energy use. We also examine application domains, dataset effects, common evaluation metrics, and deployment platforms (e.g., Jetson, Raspberry Pi, microcontrollers, Field-Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGAs)), and highlight practical hardware–software considerations. Emerging directions such as hybrid convolutional neural network (CNN)-Transformer modules and hardware-aware Neural Architecture Search are discussed, and key open challenges are identified, including cross-scene generalization, robustness to dynamic environmental interference, and the need for standardized evaluation protocols and hardware-aware co-design. This review consolidates current knowledge and offers practical guidance for researchers and practitioners developing or deploying lightweight YOLO models on constrained hardware.

Introduction

Object detection is a fundamental computer vision task that identifies object categories and precisely localizes them with bounding boxes in images or videos. The advent of deep learning has significantly transformed the landscape of object detection, enabling models to learn complex patterns and features directly from data. There are various target detection algorithms available in this field, which at this stage can be categorized into two main groups, single-stage and two-stage detection (Li et al., 2021). Among these, single-stage detectors, particularly the You Only Look Once (YOLO) (Redmon et al., 2016) family, have gained prominence due to their ability to perform detection in real-time, making them suitable for various applications such as autonomous vehicles, crop pest detection, remote sensing, real-time monitoring and robotics.

Unlike traditional methods that rely on region proposal networks, YOLO treats object detection as a regression problem, predicting bounding boxes and class probabilities directly from full images in one evaluation. This innovative approach allows YOLO to achieve remarkable speeds, making it one of the fastest object detection algorithms available. Over the years, several iterations of YOLO have been released (Redmon & Farhadi, 2017, 2018; Bochkovskiy, Wang & Liao, 2020; Khanam & Hussain, 2024a; Li et al., 2023; Wang, Bochkovskiy & Liao, 2023; Varghese & Sambath, 2024; Wang, Yeh & Mark Liao, 2025; Wang et al., 2024a; Khanam & Hussain, 2024b). From the initial YOLO to the latest YOLOv11, each generation of YOLO algorithms introduces important innovations in feature extraction, bounding box prediction, and optimization techniques. Traditional YOLO models, such as YOLOv3 (Redmon & Farhadi, 2018) and YOLOv4 (Bochkovskiy, Wang & Liao, 2020), are known for their high accuracy and speed in object detection tasks. However, these models often require significant computational resources, limiting their applicability in resource-constrained environments such as mobile devices, embedded systems, and edge computing etc. Lightweight YOLO models has become increasingly important as the demand for deploying object detection systems on resource-constrained devices grows.

In recent years, the YOLO series has gradually evolved towards lightweight to meet the needs of resource-constrained environments. For example, YOLOv5 (Khanam & Hussain, 2024a) used Automatic Mixed Precision Training to improve inference speed while reducing model size. It has been widely used in embedded devices with its lightweight design and efficient inference speed. YOLOv6 (Li et al., 2023) and YOLOv7 (Wang, Bochkovskiy & Liao, 2023) achieve a higher balance of efficiency and accuracy by optimizing the network structure, and YOLOv8 (Varghese & Sambath, 2024) introduced the lighter C2f module, which improves feature extraction while reducing parameter and computational costs. YOLOv9 (Wang, Yeh & Mark Liao, 2025), released in February 2024, introduces two key technologies: programmable gradient information (PGI) and generalized efficient layer aggregation network (GELAN), which significantly improves the model’s lightweight capability and detection accuracy. YOLOv10 (Wang et al., 2024a), released in May 2024 and developed by a team from Tsinghua University, focuses on optimizing the inference speed and model efficiency. It generates multiple prediction boxes in the training phase through the One-to-Many and One-to-One label assignment mechanisms, while retaining only the best frame, thus eliminating the need for Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS). This improvement significantly reduces inference latency while enhancing detection accuracy. YOLOv10 further optimizes Cross Stage Partial Network (CSPNet) to reduce computational redundancy by dynamically adjusting the processing of feature maps. In addition, the introduction of the large kernel convolution module extends the sensory field of the model and enhances the global feature extraction capability, which is especially suitable for small target detection in complex scenes. YOLOv11 (Khanam & Hussain, 2024b) is the latest version of the YOLO series, released in September 2024, further improving the model’s lightweight capabilities and multitasking support. YOLOv11 introduces the C3k2 module (Cross Stage Partial with kernel size 2) and the Convolutional block with Parallel Spatial Attention (C2PSA) module, which significantly improve the feature extraction efficiency. C3k2 reduces the computational effort by using smaller convolutional kernels, while C2PSA enhances the model’s ability to focus on critical regions through the spatial attention mechanism, which is particularly suitable for occlusion and small target detection. YOLOv11 further reduces model parameters and calculations while maintaining high accuracy. It has the potential for a wide range of applications in fields such as medical, autonomous driving and industrial inspection.

Problem statement

In the real environment, the situation that needs to use object detection is often time-sensitive, so the object detection network reasoning speed is required to achieve real-time effect. The deployment of these algorithms on resource-constrained devices, such as mobile phones and drones, also requires optimization.

However, there is a lack of systematic reviews on YOLO lightweight improvement in object detection, and the fragmentation of existing studies makes it difficult for researchers to grasp effective optimization techniques and strategies. Therefore, there is a need for a systematic literature review to consolidate existing evidence, identify research gaps, and provide directions for future research.

This study aims to answer the following research question (RQ) by analyzing and summarizing recent advances in YOLO model light-weighting in object detection within the last decade (2016–2025):

RQ1: What technologies are currently widely used for YOLO light-weighting in object detection?

RQ2: What are the main application scenarios of lightweight YOLO models? How do datasets from different domains affect model performance?

RQ3: What hardware platforms are suitable for deploying lightweight YOLO models?

RQ4: What performance metrics are used to evaluate lightweight YOLO models?

Research contributions

This SLR divides the research into different areas, emphasizing the specific applications and challenges associated with each area. By examining the trade-offs between detection accuracy and computational efficiency of different lightweight YOLO models, this study identifies the most effective methods and areas for future research.

The methodology of this SLR is inspired by the guidelines provided by Budgen & Brereton (2006) and Silva & Neiva (2016). This systematic literature review provides a comprehensive overview of lightweight YOLO models for target detection, highlighting the importance of optimizing these models for deployment on resource-constrained devices and the significant contributions of existing research and emphasizes the need for further exploration and innovation in this area.

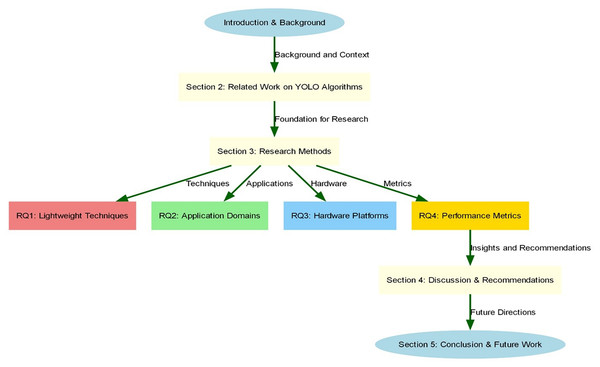

This article is organized into five sections and graphically presented in Fig. 1. ‘Related Research’ is a review of the work related to the YOLO family of algorithms, ‘Research Methodology’ describes the research methodology used in this systematic literature review, ‘YOLO Light-Weighting Techniques (RQ1)’ analyzes and discusses the collected literature around the research questions, and finally ‘Conclusions’ is the conclusion and outlook will summarize the full article, outlining the main conclusions and contributions of the study, and looking forward to future research directions.

Figure 1: Structure of the systematic literature review.

Related research

After an exhaustive search, we did not find any systematic literature reviews specifically targeting lightweight YOLO models in the field of object detection between 2016 and 2025. However, we identified 12 review articles related to object detection and lightweight technologies.

Target detection is a critical task in various applications, such as autonomous driving, crop pest detection, remote sensing, and wildlife monitoring. As demand grows for lightweight and efficient models, researchers are exploring methods to enhance their speed and accuracy.

Jiao et al. (2019) provides a comprehensive overview of deep learning-based target detection techniques, covering one-stage detectors (e.g., YOLO series) and two-stage detectors (e.g., Faster region-based convolutional neural networks (R-CNN)), while analyzing their performance and applicable scenarios. It also outlines applications in autonomous driving and intelligent surveillance, along with future trends, offering key insights into the field’s development history and prospects.

In contrast, Wu, Sahoo & Hoi (2020) focuses on recent advances in deep learning-based target detection, systematically analyzing frameworks divided into detection components, learning strategies, and applications/benchmarking. Detection components explore modules like feature extraction, candidate region generation, and bounding box regression, emphasizing optimizations for improved performance. Learning strategies address training enhancements via algorithms and loss functions. The applications section evaluates models in real scenarios, comparing benchmark datasets to guide selection. This framework aids in understanding component interactions and supports researchers in choosing optimization directions.

Similarly, Zou et al. (2023) reviews target detection techniques over the past 20 years, from traditional manual features to deep learning models. It highlights deep learning’s impact, particularly the YOLO series for its speed and simplicity. The review also covers dataset evolution, evaluation metrics, and acceleration techniques like feature-sharing and cascade detection, providing historical context for technique optimization. However, it offers limited discussion on compression for lightweight YOLO models.

All three references focus on target detection technology. Specifically, Jiao et al. (2019) and Zou et al. (2023) offer a macroscopic analysis of its development history and application prospects, outlining the field’s overall evolution and future directions to provide a foundational understanding of the domain. In contrast, Wu, Sahoo & Hoi (2020) examines the technological frameworks in depth, helping researchers grasp the internal mechanisms of various detection models. However, while Jiao et al. (2019) and Wu, Sahoo & Hoi (2020) cover a broad spectrum of techniques and applications, they devote relatively little attention to lightweight YOLO models.

Regarding lightweight target detection techniques, Liang et al. (2021) summarizes pruning and quantization methods for accelerating deep neural networks, analyzing static vs dynamic pruning and the impact of quantization on accuracy. Vadera & Ameen (2022) categorizes over 150 pruning studies, emphasizing methods like weight magnitude, clustering, and sensitivity analysis, with comparisons across models (e.g., ResNet, VGG). He & Xiao (2024) explores structured pruning for convolutional networks, which removes redundant filters to reduce complexity and storage while preserving performance. Though not YOLO-specific, these methods provide a foundation for lightweight YOLO design—for instance, enabling parameter reduction without major accuracy loss, ideal for resource-constrained environments. A limitation is the focus on general networks, with less emphasis on YOLO-specific optimizations like anchor design or loss functions.

Gholami et al. (2021) investigates neural network quantization, highlighting how converting weights and activations to low-precision integers reduces memory and latency without significant performance drops. This is crucial for lightweight YOLO deployment on edge devices, though the study lacks depth on synergies with techniques like knowledge distillation in target detection. Rokh, Azarpeyvand & Khanteymoori (2023) reviews quantization for DNNs in image classification, focusing on clustering and scaling to approximate full-precision values, offering references for lightweight YOLO applications. Gou et al. (2021) examines knowledge distillation paradigms (offline, online, self-distillation) and their use in vision tasks, but provides limited exploration of optimizations for lightweight YOLO in specific scenarios.

In contrast, Lyu et al. (2024) focuses on model compression strategies for target detection, particularly lightweight YOLO models. It systematically reviews techniques like network pruning, lightweight design, Neural Architecture Search (NAS), low-rank decomposition, quantization, and Knowledge Distillation (KD), analyzing their performance on public datasets. By comparing effects on YOLO, it offers insights into balancing efficiency and accuracy—for example, lightweight designs optimize convolutions (e.g., depthwise separable), while NAS automates structure searches for efficient models. These approaches enable deployment on resource-constrained devices and inform compression for other models. However, Lyu et al. (2024) insufficiently addresses strategy adaptability and issues in diverse scenarios.

Xu, Huang & Jia (2024) reviews compression methods (pruning, quantization, low-rank decomposition, knowledge distillation, lightweight design), detailing principles and challenges like performance degradation in low-bit quantization. These are valuable for lightweight YOLO, though limitations persist in deep networks.

Additionally, Mazumder et al. (2021) explores NAS for optimal architectures, noting traditional methods’ high costs and proposing reinforcement learning-based approaches for lightweight designs. This inspires efficient YOLO variants for limited hardware.

Despite progress in compression, acceleration, and optimization, limitations remain, such as poor generalization across YOLO versions, hardware constraints on mobile real-time performance, accuracy drops from pruning/quantization, and complex knowledge distillation training.

Existing literature is broad, but more focused reviews are needed on techniques, data, and applications specific to lightweight YOLO. A comparison of survey articles is provided in Table 1.

| Study | Mention or discussion YOLO | Light-weight | Technique | Application | Datasets | Hardware platforms | Performance metrics | Challenge | Future direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jiao et al. (2019) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Wu, Sahoo & Hoi (2020) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Zou et al. (2023) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Liang et al. (2021) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Vadera & Ameen (2022) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| He & Xiao (2024) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Gholami et al. (2021) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Rokh, Azarpeyvand & Khanteymoori (2023) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Gou et al. (2021) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Lyu et al. (2024) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Xu, Huang & Jia (2024) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Mazumder et al. (2021) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Research methodology

This study aims to explore how to reduce the number of parameters and computational complexity of YOLO models through techniques such as pruning, quantization, lightweight network design, and Transformer fusion, while maintaining model performance. We will systematically analyse and compare the existing lightweighting techniques in the literature, evaluate their advantages and disadvantages, and summarize the research challenges and future directions.

The main objectives of this systematic literature review (SLR) include:

-

1.

investigate the application of existing lightweighting techniques in the YOLO model and their performance.

-

2.

Analyse the impact of various lightweighting techniques (pruning, quantization, lightweight network design and Transformer, etc.) on YOLO models.

-

3.

Summarize the technical challenges and research deficiencies in the existing research and provide directions for future research.

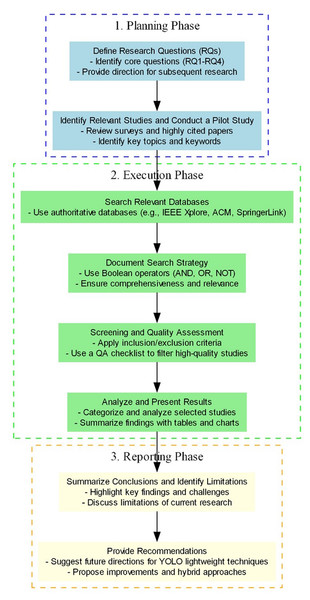

According to literature reviews, this is the first systematic review of YOLO lightweight technologies, covering the YOLO model family (YOLOv1 to YOLOv11, etc.) and its lightweight technologies from 2016 to 2025. This study adopts the SLR method proposed by Kitchenham & Charters (2007), Budgen & Brereton (2006), which is divided into three main stages: planning, execution, and reporting, with each stage further subdivided into sub-stages (as shown in Fig. 2).

Figure 2: SLR includes an overview diagram of the three main phases.

Literature sources and search process

To ensure the comprehensiveness and scientific rigor of this systematic review, we implemented a stringent and reproducible literature search and screening process. The process is summarized below.

Selection of literature databases

We selected two leading and widely recognized academic databases, Scopus and the Web of Science (WoS) Core Collection, as our primary sources for literature retrieval. The rationale is threefold:

Extensive coverage: Scopus and WoS collectively index a broad set of peer-reviewed journals and proceedings from major publishers (including MDPI, Springer Nature, IEEE, Elsevier, Frontiers, Tech Science Press, SAGE, IET, among others), which supports a representative literature sample.

Quality control: Both databases prioritize peer-reviewed publications, helping ensure academic rigor of included studies.

Mitigation of publisher bias: Using multiple comprehensive databases reduces reliance on any single publisher platform and helps to minimize selection bias.

Search keywords and strategy

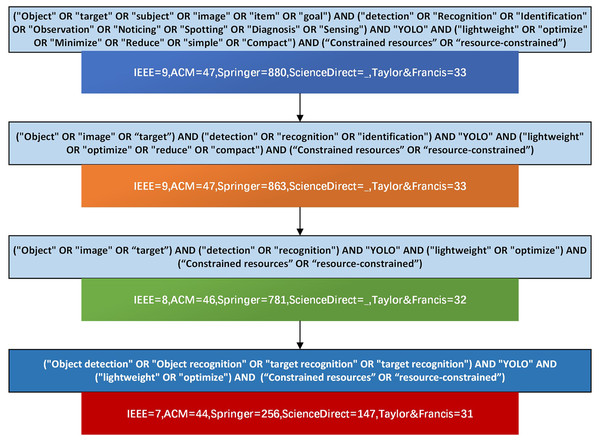

The process of developing our search query, from the initial research statement to the final keywords and synonyms, is illustrated in Fig. 3. Based on our research questions and initial scoping, we developed a search string combining object detection terms, model names, and lightweighting terms to maximize recall while maintaining relevance. The keyword categories included:

-

Object detection related: object, target, image, subject, item

Detection action related: detection, identification, recognition, observation, spotting, sensing

Model name: YOLO

Lightweight related: lightweight, optimize*, minimiz*, compact, resource-constrained, tiny, lite, mobile, efficient

Figure 3: Search query filtering process.

The final search string applied (adapted to each database syntax) was:

(“object detection” OR “target detection” OR “object recognition” OR “target recognition”) AND “YOLO” AND (“lightweight” OR “optimize*” OR “minimiz*” OR “compact” OR “resource-constrained” OR “tiny” OR “lite” OR “mobile” OR “efficient”)

This search strategy underwent iterative refinement through pilot queries to balance comprehensiveness and precision.

Timeframe and document types

Timeframe: We limited our search to publications between 2016-01-01 and 2025-01-01 to cover the evolution of the YOLO family and related lightweighting methods.

Document types: To ensure comparability and peer review quality, we only included peer-reviewed journal articles and peer-reviewed conference articles published in English. Workshop articles, technical reports, and other non-peer-reviewed materials were excluded (see Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria below for details).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria:

-

1.

peer-reviewed journal articles and peer-reviewed conference articles published in English.

-

2.

Publication date between 2016-01-01 and 2025-01-01.

-

3.

Explicit focus on YOLO or YOLO-based object detection with attention to one or more lightweighting strategies (e.g., pruning, quantization, knowledge distillation, lightweight backbones, Neural Architecture Search).

-

4.

Empirical evaluation reported (datasets and quantization performance metrics).

Exclusion criteria:

-

1.

Non-peer-reviewed materials (e.g., preprints, workshop abstracts not subject to peer review, technical reports, and student theses).

-

2.

Non-English publications.

-

3.

Articles that do not present experimental results or do not have a clear focus on YOLO or lightweighting techniques.

-

4.

Duplicate publications: when the same work appears in multiple venues (e.g., a conference article later extended to a journal article), the most complete peer-reviewed version was retained and the duplicate(s) were excluded.

Screening and selection procedure

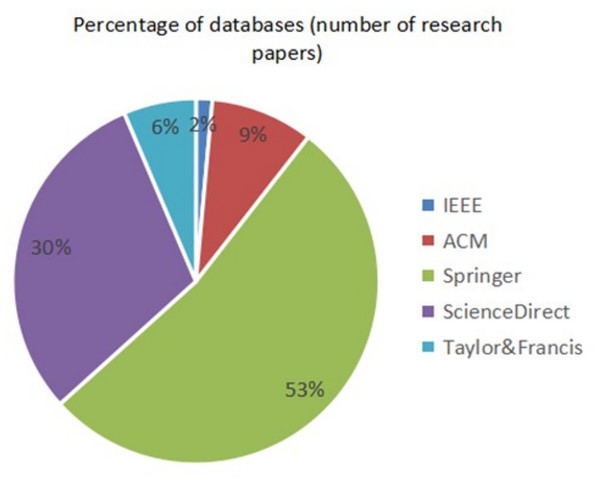

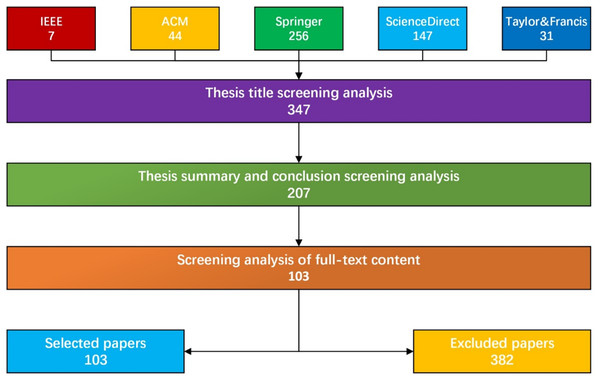

The literature screening followed PRISMA 2020 guidelines (Page et al., 2021) to ensure transparency and reproducibility. Two reviewers independently performed title and abstract screening and then full-text eligibility assessment. Disagreements at any stage were resolved by discussion; when consensus could not be reached, a third reviewer made the final decision. After duplicate removal, the initial search returned 485 unique records. Title screening excluded 138 records; abstract screening excluded a further 140 records; full-text assessment led to exclusion of 104 additional records (mainly because the studies did not specifically focus on lightweight YOLO or lacked sufficient empirical data). The multi-stage screening resulted in 103 peer-reviewed journal and conference articles that met all inclusion criteria and were included for detailed analysis (PRISMA flow shown in Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Search query filtering process.

Data extraction, labelling and statistics

Data extraction and topic annotation (technical categories, application domains, hardware platforms, etc.) were manually performed by two independent reviewers. For each included study, we recorded metadata (authors, year, journal, DOI, publisher), the YOLO variant used, lightweighting methods, datasets, reported performance metrics (e.g., mean Average Precision (mAP)), model size/FLOPs/FPS (if available), and the hardware platform used for deployment experiments. The percentage statistics reported in this review (e.g., “35% of studies used pruning”) were calculated as follows: (number of studies explicitly applying the technique among the 103 included studies) 103. Label inconsistencies were resolved through discussion and consensus.

Quality assessment

All 103 peer-reviewed articles underwent a pre-defined quality assessment (QA) using a 12-item checklist (Table 2). Each criterion was scored as P (Present = 1), S (Sufficient/partially met = 0.5) or A (Absent = 0). QA scores were mapped to the review’s research questions to support transparent interpretation of the evidence base.

| QA | Quality assessment issues | Points |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Does the literature clearly Definition the objectives of the study? | P/S/A |

| 2 | Does the literature suggest methods (for RQ1) related to lightweighting techniques (e.g., pruning, quantization, NAS)? | P/S/A |

| 3 | Has the literature analyzed the impact of these lightweighting techniques on the performance of different YOLO variants (for RQ1)? | P/S/A |

| 4 | Does the literature discuss the main application scenarios for lightweight YOLO models (for RQ2)? | P/S/A |

| 5 | Has the literature evaluated the impact of different datasets on the performance of lightweight YOLO models (for RQ2)? | P/S/A |

| 6 | Does the literature mention a suitable hardware platform for the lightweight YOLO model (for RQ3)? | P/S/A |

| 7 | Does the literature analyze the computational performance and application scenario characteristics of these hardware platforms (for RQ3)? | P/S/A |

| 8 | Does the literature suggest performance metrics for evaluating lightweight YOLO models (for RQ4)? | P/S/A |

| 9 | Has the literature used these performance metrics for experimental evaluation of lightweight YOLO models (for RQ4)? | P/S/A |

| 10 | Does the literature use publicly available authoritative datasets (e.g., COCO, PASCAL VOC) for experiments? | P/S/A |

| 11 | Has the literature conducted comparative experiments with existing lightweighting methods (e.g., pruning, quantization, NAS)? | P/S/A |

| 12 | Are the experimental results in the literature consistent with the conclusions and compared with current state-of-the-art methods (SOTA)? | P/S/A |

Research question

Literature screening will be targeted and systematically assessed based on the following research questions. Through this precise and multidimensional screening strategy, we will ensure that the selected literature can respond to the research questions in a comprehensive and in-depth manner, and provide high-quality theoretical foundation and empirical support for the systematic literature review.

RQ1: What technologies are currently widely used for YOLO light-weighting in object detection?

RQ2: What are the main application scenarios of lightweight YOLO models? How do datasets from different domains affect model performance?

RQ3: What hardware platforms are suitable for deploying lightweight YOLO models?

RQ4: What performance metrics are used to evaluate lightweight YOLO models?

Literature quality assessment methodology

The correspondence between the quality assessment questions (QA) and the research questions (RQ) is shown in Table 3. This mapping ensures that our quality assessment is directly aligned with the core objectives of this review.

| Research question (RQ) | Quality assessment issues (QA) |

|---|---|

| RQ1: Lightweighting techniques and their impact on YOLO variants | QA2, QA3 |

| RQ2: Impact of application scenarios and datasets on lightweight YOLO models | QA4, QA5 |

| RQ3: Computing performance of hardware platforms and application scenario characteristics | QA6, QA7 |

| RQ4: Performance metrics and experimental evaluation | QA8, QA9 |

| Generic questions (for all RQs) | QA1, QA10, QA11, QA12 |

Each article was scored on a three-point scale for 12 criteria, with a maximum possible score of 12. The scoring was defined as: P (Present) = 1 (criterion fully met), S (Sufficient) = 0.5 (criterion partially met), and A (Absent) = 0 (criterion not met). The detailed scores for all 103 articles are presented in Table 4.

| Study | QA1 | QA2 | QA3 | QA4 | QA5 | QA6 | QA7 | QA8 | QA9 | QA10 | QA11 | QA12 | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chang et al. (2024) | P | S | P | S | A | S | A | P | P | A | A | S | 6 |

| Khan & Park (2024) | P | A | A | P | P | A | A | P | P | P | A | P | 7 |

| Yu et al. (2024b) | P | P | A | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | P | A | 8 |

| Hsiao, Sheu & Ma (2024) | P | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | P | P | 8 |

| Yuan et al. (2024) | P | A | A | P | A | P | P | P | P | A | A | P | 7 |

| Vinoth & Sasikumar (2024) | P | P | A | P | P | A | A | P | A | P | P | A | 7 |

| Song et al. (2024) | P | P | A | P | A | A | A | P | A | P | P | A | 6 |

| Jing et al. (2024) | P | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | P | A | 7 |

| Chen et al. (2024) | P | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | A | P | A | A | 7 |

| Sharifi, Zoljodi & Daneshtalab (2024) | P | P | A | P | A | A | A | P | A | P | P | A | 6 |

| Lei et al. (2024a) | P | P | A | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | A | P | 8 |

| Habara, Sato & Awano (2024) | P | P | A | P | A | A | A | P | A | P | A | A | 5 |

| Ming et al. (2024) | P | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | P | A | 7 |

| Shwe & Aritsugi (2024) | P | A | A | P | A | A | A | P | P | P | P | A | 6 |

| Kim, Chae & Lee (2024) | P | A | A | P | A | A | A | A | A | P | P | A | 4 |

| Miao et al. (2024) | P | P | A | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | P | A | 8 |

| Yu et al. (2024a) | P | P | A | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | P | A | 8 |

| Li et al. (2024b) | P | P | A | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | P | A | 8 |

| Toan, Le & Nguyen (2024) | P | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | A | A | A | A | 4 |

| Shao et al. (2024) | P | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | P | A | 7 |

| Zhang et al. (2024b) | P | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | P | P | 8 |

| Naveen & Kounte (2025) | P | P | A | A | A | P | A | P | A | P | P | A | 6 |

| Zhong, Xu & Liu (2024) | P | P | A | P | A | A | A | P | A | P | P | A | 6 |

| Moosmann et al. (2024) | P | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | A | P | P | A | 8 |

| Shi et al. (2024) | P | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | P | A | 7 |

| Mach, Van & Le (2024) | P | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | A | P | P | A | 8 |

| Zhou et al. (2024) | P | P | A | P | A | A | A | P | A | P | P | A | 6 |

| Pan et al. (2024) | P | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | P | A | 7 |

| Lin, Yun & Zheng (2024) | P | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | P | P | 8 |

| Silva et al. (2024) | P | A | A | A | P | A | A | P | A | P | A | A | 3 |

| Dong et al. (2025) | P | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | A | P | P | A | 8 |

| Kang, Hwang & Chung (2022) | P | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | P | A | 7 |

| He et al. (2021) | P | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | A | P | P | A | 8 |

| Zhu et al. (2023) | P | P | P | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | A | A | 8 |

| Evain et al. (2023) | P | P | P | P | A | P | P | P | P | P | A | A | 9 |

| González-Cepeda, Ramajo & Armingol (2022) | P | A | A | P | A | A | A | P | P | A | A | A | 3 |

| Oh & Lee (2023) | P | A | A | P | P | A | A | P | A | P | P | A | 6 |

| Arifando, Eto & Wada (2023) | P | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | P | A | 7 |

| Pang et al. (2023) | P | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | P | P | P | A | 8 |

| Liu et al. (2023) | P | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | A | P | P | A | 8 |

| Li, Li & Meng (2023) | P | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | A | A | 6 |

| Nousias et al. (2023) | P | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | P | A | 7 |

| Wu et al. (2023) | P | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | P | A | 7 |

| Li et al. (2024a) | P | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | P | P | 8 |

| Wu, Zhao & Jin (2024) | P | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | P | A | 7 |

| Zhichao et al. (2024) | P | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | P | A | 7 |

| Liu et al. (2024a) | P | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | A | P | P | A | 8 |

| Xia et al. (2024) | P | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | P | A | 7 |

| Zhao et al. (2021) | P | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | A | P | A | A | 7 |

| Pan, Guan & Zhao (2024) | P | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | P | A | 7 |

| Jiang et al. (2024a) | P | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | P | P | 8 |

| Qiu et al. (2024) | P | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | P | P | A | A | 7 |

| Wang et al. (2024b) | P | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | A | P | P | A | 8 |

| Dai et al. (2024) | P | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | A | P | P | A | 8 |

| Hanif et al. (2024) | P | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | A | P | P | A | 8 |

| Tang et al. (2024) | P | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | A | P | P | A | 8 |

| Chen & Zhang (2024) | P | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | A | P | P | A | 8 |

| Lu, Zhang & Liu (2023) | P | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | A | P | P | A | 8 |

| Zhuang et al. (2024) | P | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | A | P | P | A | 8 |

| Wang Lucai (2024) | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | A | 10 |

| Wang et al. (2024c) | P | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | A | P | P | A | 8 |

| Pan, Guan & Jia (2024) | P | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | A | P | P | A | 8 |

| Wang et al. (2022) | P | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | A | P | A | A | 7 |

| Li, Zeng & Lu (2024) | P | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | A | P | P | A | 8 |

| Liu et al. (2024b) | P | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | P | P | A | A | 8 |

| Gong (2024) | P | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | A | P | A | A | 7 |

| Du, Zhang & Yang (2024) | P | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | A | P | A | A | 7 |

| Wang, Letchmunan & Xiao (2024) | P | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | A | P | P | A | 8 |

| Qing et al. (2024) | P | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | P | P | A | A | 8 |

| Wang et al. (2023b) | P | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | P | P | P | A | 9 |

| Farooq et al. (2021) | P | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | P | P | A | A | 8 |

| Gan et al. (2025) | P | P | A | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | A | 10 |

| Xu et al. (2024) | P | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | P | P | P | A | 9 |

| Han et al. (2024) | P | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | P | P | P | A | 9 |

| Boyle et al. (2024) | P | P | A | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | A | 10 |

| Shahzad, Hanif & Shafique (2024) | P | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | P | P | P | A | 9 |

| Ortiz Castelló et al. (2020) | P | A | A | P | P | A | P | P | P | P | P | A | 8 |

| Deng, Zhou & Liu (2024) | P | P | A | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | A | 10 |

| Du et al. (2022) | P | P | A | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | A | 10 |

| Fan et al. (2024) | P | P | A | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | A | A | 9 |

| Gonçalves, Ghali & Akhloufi (2024) | P | A | A | P | A | A | A | P | P | P | P | A | 6 |

| Gong et al. (2024) | P | A | A | P | P | A | A | P | P | P | P | A | 8 |

| Huang et al. (2023) | P | P | A | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | A | 10 |

| Huang et al. (2024) | P | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | P | P | P | A | 9 |

| Jiang et al. (2024b) | P | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | P | P | P | A | 9 |

| Kwon & Lee (2024) | P | A | A | P | A | A | P | A | P | P | A | A | 5 |

| Lei et al. (2024b) | P | P | A | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | A | A | 9 |

| Li, Zhang & Yang (2023) | P | A | A | P | A | A | A | P | P | P | A | A | 5 |

| Liu et al. (2022) | P | P | A | P | A | A | P | P | P | P | P | A | 8 |

| Lu et al. (2024) | P | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | P | P | A | A | 8 |

| Ma et al. (2024) | P | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | P | P | P | A | 8 |

| Mamadaliev et al. (2024) | P | P | A | P | A | A | P | P | A | P | P | P | 8 |

| Rehman et al. (2022) | P | A | A | P | A | A | A | P | P | P | A | A | 5 |

| Ruengrote et al. (2024) | P | P | A | P | A | A | A | P | P | P | P | A | 8 |

| Wang et al. (2023a) | P | P | A | P | P | P | P | P | A | P | A | A | 8 |

| Yan et al. (2022) | P | P | A | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | A | 10 |

| Yang et al. (2024) | P | P | A | P | A | A | A | P | P | P | P | P | 8 |

| Zhang et al. (2024a) | P | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | A | P | P | A | 8 |

| Zhang et al. (2024c) | P | A | A | P | A | A | A | P | A | P | P | A | 5 |

| Zhang et al. (2024d) | P | P | A | P | A | A | A | P | P | P | P | A | 8 |

| Zhang, Mahmud & Kouzani (2022) | P | P | A | P | P | A | A | P | P | P | A | P | 8 |

| Zhao, Ren & Tan (2024) | P | P | A | P | A | A | A | P | A | P | P | A | 6 |

| Zheng et al. (2024) | P | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | P | A | 7 |

This scoring process allowed us to systematically map the landscape of the literature and understand the overall quality and focus of the included studies. The detailed scores provide transparency on the evidence base for this review.

YOLO light-weighting techniques (RQ1)

Understanding YOLO architecture and lightweighting interventions

We defined ‘lightweight YOLO variants’ as YOLO derivatives that reduce model capacity or computation—for example, Tiny/n variants (e.g., YOLO-Tiny), efficient backbones (e.g., MobileNet, ShuffleNet, GhostNet), or models that apply compression/optimization techniques (e.g., pruning, quantization, knowledge distillation, neural architecture search).

A typical YOLO model is generally composed of three main components: the Backbone for feature extraction, the Neck for feature aggregation, and the Head for prediction. Lightweighting techniques are strategically applied to these components to optimize model performance and efficiency. Figure 5 illustrates how different lightweighting approaches interact with these architectural elements.

Figure 5: Based on title, abstract, conclusion, and full text screening process.

Specifically:

Pruning typically targets the Backbone and Neck components by removing redundant parameters or connections.

Lightweight Network Architecture (LNA) primarily involves replacing the original Backbone with a more efficient, compact design.

Quantization reduces the numerical precision of weights and activations across the entire network (Backbone, Neck, and Head).

To address Research Question 1 (RQ1) regarding the most effective lightweighting techniques for YOLO models, this section provides a comprehensive analysis of four widely used approaches in target detection:

Pruning

Quantization

Knowledge distillation

Lightweight Network Architecture

This article provides a synopsis of the primary objectives, advantages, and limitations of four lightweight technologies in object detection models, including pruning, quantization, knowledge distillation, and lightweight network structures. A comparative analysis of these lightweight technologies is presented in Table 5. The implementation of these technologies across various YOLO models has garnered significant attention and has yielded effective solutions for a range of optimization requirements.

| Technology used | Primary objective | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pruning | Remove redundant parameters to reduce computation | Significantly reduces model size and computational complexity. Suitable for edge devices and embedded systems. |

Excessive pruning may lead to accuracy degradation. Additional fine-tuning is required to restore performance. |

| References: Chang et al. (2024), Yu et al. (2024b), Han et al. (2024), Fan et al. (2024), Gong et al. (2024), Liu et al. (2022), Wang et al. (2023a), Yan et al. (2022) | |||

| Quantization | Reduced precision of weights and activation values | Significantly reduces storage requirements and inference latency. Ideal for mobile devices and resource-constrained environments. |

Low bit quantization may affect small target detection accuracy. Quantized Awareness Training (QAT) is required to minimize performance loss. |

| References: Chen et al. (2024), Moosmann et al. (2024), Boyle et al. (2024), Gong et al. (2024) | |||

| Knowledge distillation | Using teacher models to guide student model training | Improves the accuracy and generalization ability of lightweight models. Effective in small target detection and complex scenes. |

Complex training process and reliance on high-quality teacher models. Increased training time and computational resource requirements. |

| References: Gou et al. (2021), Zhu et al. (2023), Evain et al. (2023), Wang Lucai (2024) | |||

| Lightweight network architecture | Designing efficient architectures to reduce computation | Significantly reduces the number of parameters and computational complexity. Suitable for resource-constrained environments with fast inference speeds. |

May lead to degradation of feature extraction capability. Needs to incorporate other techniques (e.g., knowledge distillation) to improve performance in complex scenarios. |

| References: Yu et al. (2024b), Kang, Hwang & Chung (2022), Wu et al. (2023), Deng, Zhou & Liu (2024), Du et al. (2022), Fan et al. (2024), Lu et al. (2024), Ma et al. (2024), Yang et al. (2024), Zhang et al. (2024a) | |||

Pruning significantly reduces model size and computational complexity by removing redundant parameters and is suitable for deployment in edge devices and embedded systems, but requires fine-tuning to recover from possible accuracy loss. Pruning can be categorized into structured pruning and unstructured pruning and the difference between the two can be seen in Table 6.

| Pruning types | Definition | Pruning units | Advantages | Drawbacks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structured pruning | Remove entire convolutional kernels, channels, or hierarchical structures to reduce the amount of model computation and number of parameters. | Convolutional kernels, channels, layers |

|

|

| References: Yu et al. (2024b), Han et al. (2024), Wang et al. (2023a) | ||||

| Unstructured pruning | Removing individual parameters with small weights further compresses the model size. | Individual weights |

|

|

| References: Vadera & Ameen (2022), He & Xiao (2024) | ||||

Quantization techniques reduce the consumption of computational resources and memory footprint by reducing the precision of model weights and activation values (e.g., by converting from 32-bit floating-point numbers to 8-bit integers), while improving inference efficiency. Quantization techniques are widely used in the deployment of deep learning models, especially on resource-constrained devices (e.g., mobile devices and embedded systems). Common quantization methods include static quantization, dynamic quantization, and mixed-precision quantization, and the differences and advantages and disadvantages among the three techniques can be seen in Table 7.

| Type of quantization | Definition | Quantization methods | Advantages | Drawbacks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Static quantization | The weights and activation values were quantized to low precision (e.g., INT8) prior to inference, and the dynamic range of the activation values was estimated offline from calibration data. | Offline quantization |

|

|

| References: Moosmann et al. (2024) | ||||

| Dynamic quantization | Dynamic adjustment of quantization parameters according to the distribution of input data during inference, eliminating the need to calibrate the dynamic range of activation values offline. | Online Quantization | 1. No need to calibrate data 2. Dynamically adapts to input data distribution with less loss of accuracy |

1. Higher realization complexity 2. Higher hardware resource requirements |

| References: Boyle et al. (2024) | ||||

| Mixed-precision quantization | Different numerical accuracies (e.g., FP16 and INT8) are used in different parts of the model to balance computational speed and accuracy. | Multi-precision mixing |

|

|

| References: Chen et al. (2024) | ||||

Knowledge distillation is an approach that aims to improve the performance of student models while reducing their computational complexity by utilizing complex teacher models to guide the training of lightweight student models. This approach is particularly suitable for resource-constrained scenarios such as edge device deployments. The core idea of knowledge distillation is to pass the knowledge embedded in the teacher model (e.g., probability distributions, feature representations, or response mappings) to the student model, thereby compensating for the student model’s deficiencies in terms of the number of parameters and computational power. Comparison of two kinds of knowledge distillation as shown in Table 8.

| Comparison dimension | Soft label distillation (Gou et al., 2021) | Feature matching (Wang Lucai, 2024) |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | The probability distributions (soft labels) output by the teacher’s model are used as supervisory signals to help the student model learn the relative relationships between categories and data distributions. | The feature extraction capability of the student model is directly optimized by aligning the intermediate layer feature representations of the teacher model and the student model. |

| Core idea | Use the category probability distributions (e.g., confidence and category distributions in target detection) of the teacher’s model outputs to guide student model learning. | The intermediate feature representation of the teacher’s model is used to guide the student model so that the feature space of the student model is close to the feature space of the teacher’s model. |

| Surveillance signals | The output probability distribution of the teacher’s model (e.g., the category probabilities of the Softmax output). | Intermediate layer feature representations (e.g., convolutional feature maps) of the teacher model and the student model. |

| Applicable scenarios | It is suitable for scenarios where inter-category relations need to be learned in a categorization task or a target detection task. | It is suitable for scenarios that require optimized feature extraction capabilities, especially for target detection and semantic segmentation tasks. |

| Advantages |

|

|

| Drawbacks |

|

|

Lightweight network structures significantly reduce the number of parameters and computational complexity by designing efficient network architectures (e.g., deep separable convolution, group convolution, etc.) while maintaining a fast inference speed, but may need to be combined with other techniques (e.g., knowledge distillation) to make up for the lack of feature extraction capability in complex scenarios.

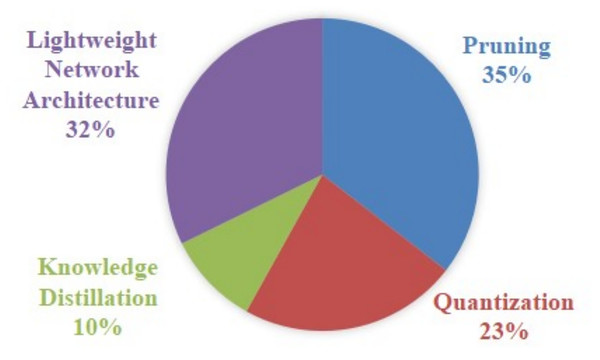

As illustrated in Fig. 6, the four main lightweight techniques are represented as follows: pruning, quantization, knowledge distillation and lightweight network architecture. Pruning is the most commonly used technique, with a percentage of adoption of 35%, and it performs particularly well in resource-constrained environments, especially where reducing hardware load is critical. Lightweight network architectures, at 32%, play an important role in the modelling phase, especially for applications on mobile devices and embedded systems. Quantisation, with a percentage of 23%, demonstrates a high level of utility in the context of edge device deployment, particularly in application scenarios that necessitate high real-time performance. Conversely, Knowledge Distillation exhibits the lowest percentage at 10%. However, it possesses a distinctive advantage in enhancing the performance and generalization capability of small models.

Figure 6: Percentage of numbers using four different lightweighting technologies.

The data show that the choice of lightweighting techniques is closely linked to specific application scenarios. Moreover, the combined use of these techniques is becoming a major trend in optimization strategies. For example, in resource-limited environments, techniques such as pruning and quantisation can effectively reduce computational complexity, while knowledge distillation and lightweight network architectures can improve model performance without compromising efficiency.

It is clear that these techniques target different optimisation goals and complement each other when applied to different YOLO variants (e.g., YOLOv3, YOLOv4, YOLOv5 and YOLOv8). The combination of these techniques enables a comprehensive optimisation of the YOLO model to meet the deployment requirements of resource-limited environments, while maintaining high accuracy and strong generalisation capabilities. The synergistic application of these lightweight techniques is a promising direction to promote the widespread use of YOLO models in real-world scenarios.

Research on YOLO model lightweighting techniques (RQ1) shows that the four mainstream techniques present significant feature differences and scenario adaptability. Pruning is the preferred solution for resource-constrained environments with the highest adoption rate of 35%, in which structured pruning can achieve 1.8× inference acceleration and unstructured pruning can achieve 4× parameter compression, but the loss of accuracy needs to be controlled within 1.2% through iterative pruning rate adjustment and fine-tuning strategies. Quantization technology can reduce inference delay by 65% and storage demand by 83% through INT8 precision conversion, but it should be noted that quantization below 8bit will lead to a steep drop of 4.7–6.2% in AP value for small target detection, and dynamic quantization can reduce accuracy loss by 2.1% compared to static quantization. Although knowledge distillation only accounts for 10% adoption rate, its feature matching approach improves small target detection mAP by 5.8% on the VisDrone dataset, at the cost of a 40% increase in training time and reliance on high-quality teacher models. The lightweight architecture design reduces computation by 75% through techniques such as deep separable convolution and realizes 47 FPS real-time inference in embedded devices, but needs to be combined with the attention mechanism to compensate for the 12.3% loss of feature extraction in complex scenarios.

Technology selection needs to strictly match the application scenarios: pruning is suitable for edge device deployment (e.g., Jetson Nano), quantization targets mobile real-time detection (e.g., 30 FPS demand on the smartphone side), knowledge distillation demonstrates advantages in complex background target detection (AP improvement of 3.5–5.8%), and lightweight architectures provide basic optimization frameworks for embedded systems (e.g., uncrewed aerial vehicle (UAV) platforms). It is worth noting that technology synergy has became a key trend. The combination of pruning and quantization achieves 12× model compression with <1.2% accuracy loss, the fusion of lightweight architecture and knowledge distillation achieves an accuracy-speed balance of AP50:68.3@32FPS for the VisDrone dataset, and the three-technology joint solution (pruning+quantization+distillation) enhances the overall performance of the three technologies by 37% compared to a single one on average.

Emerging trends in lightweight architectures

Beyond traditional CNN-based lightweight designs, a notable emerging trend involves the integration of novel architectures to enhance model capabilities without proportionally increasing computational load. Recent studies have begun to explore hybrid models that combine the strengths of CNNs with architectures like Vision Transformers (ViT) and graph convolutional networks (GCN).

For instance, Gong (2024) provides a direct example by integrating a Vision Transformer module with a lightweight ShuffleNetv2 backbone in a YOLOv7 framework. This approach aims to leverage the Transformer’s superior ability in capturing global contextual information to boost feature extraction. Similarly, Han et al. (2024) proposed a hybrid CNN-GCN model, demonstrating that graph-based structures can also offer new ways to model relationships between features, which is particularly useful in complex scenes.

The core component of Transformers, the self-attention mechanism, has also been widely adapted in lighter forms within CNN-based YOLO models. Many studies in our review, such as Zhu et al. (2023) and Wu et al. (2023), incorporate various attention modules (e.g., SE, CBAM) to selectively focus on important features, mimicking the behavior of Transformers at a lower computational cost.

However, the adoption of these emerging architectures in the lightweight domain is still cautious. A critical challenge remains in balancing the performance gains from these advanced modules against their inherent computational complexity. As highlighted by Gong (2024), the trade-off between the improved accuracy from attention mechanisms and the actual inference speed on edge devices is a primary area for further investigation. Furthermore, automating the discovery of optimal hybrid architectures through techniques like neural architecture search (NAS), as explored in related fields by Sharifi, Zoljodi & Daneshtalab (2024), presents a promising but computationally intensive future direction for designing truly efficient, next-generation lightweight YOLO models.

Case study: SS-YOLOv8n and its underlying mechanisms

To further illustrate the principles and effectiveness of lightweight network architectures, and to provide concrete insights into how these techniques collectively address the challenges of model efficiency (directly contributing to RQ1), we examine SS-YOLOv8n (Fan et al., 2024) as a representative and highly successful case. This recent lightweight variant of YOLOv8, designed for surface litter detection, integrates several key architectural and algorithmic improvements, including a slimming pruning method (a technique identified as the most prevalent in our analysis, as shown in Fig. 6), to achieve a superior balance of efficiency and accuracy, particularly for deployment on resource-constrained edge devices.

The core lightweighting strategies in SS-YOLOv8n include:

WS-C2f module (Backbone enhancement): SS-YOLOv8n replaces the standard C2f module in YOLOv8’s backbone with the proposed WS-C2f. This module enhances feature extraction by fusing two branches: a Sobel Convolution (Sobel_Conv) branch explicitly extracts edge features, crucial for distinguishing objects from complex backgrounds (like water reflections), and a standard convolutional branch extracts rich spatial information. This fusion allows the model to learn more nuanced representations, improving detection robustness without significantly increasing computational burden.

SCDH-Detect module (Lightweight Detection Head): The original decoupled detection head of YOLOv8 is replaced by the Shared Convolutional Detection Head (SCDH). SCDH significantly reduces the number of parameters by employing shared convolutional kernels across the three output layers (P3, P4, P5). It also replaces Batch Normalization (BN) with Group Normalization (GN) to maintain performance consistency with small batch sizes, common in edge deployments. Furthermore, a scale layer is introduced to address inconsistencies in target scales detected by different heads, enhancing adaptability.

PIoU2 Loss function (optimization for localization): While primarily a loss function optimization, PIoU2 contributes to the overall efficiency by accelerating convergence and improving localization precision, especially for small targets. It replaces the Complete Intersection over Union (CIoU) loss and incorporates a non-monotonic attention function to focus on mid-to-high quality anchor frames, guiding the regression process more effectively.

These integrated modifications demonstrate how lightweight network design goes beyond simple model compression, involving fundamental changes to the network’s components and training objectives to achieve optimal performance under resource constraints.

Comparative analysis of lightweight YOLO models

To provide a meaningful comparison with existing methods, we present a performance benchmark of SS-YOLOv8n against various prominent YOLO models, including other lightweight variants. The data, adapted from Fan et al. (2024), highlights the trade-offs between model size, computational complexity, and detection accuracy.

As shown in Table 9, SS-YOLOv8n demonstrates a remarkable balance between efficiency and accuracy. It achieves the smallest model size (2.3 MB), lowest Giga Floating-point Operations Per Second (GFLOPs) (3.1 G), and fewest parameters (0.88 M) among all compared models, making it highly suitable for resource-constrained environments. Despite its compact nature, SS-YOLOv8n maintains a competitive mAP50 of 0.799 and mAP50–95 of 0.510, outperforming several larger models like YOLOv5n/s, YOLOv8n, YOLOv8-mobilentv4, and YOLOv8-ghost in mAP50. Furthermore, its inference speed (128.9 FPS) is the highest, significantly surpassing the original YOLOv8n (112.5 FPS) and other lightweight variants. This superior performance highlights the success of SS-YOLOv8n’s integrated lightweight design strategies, which optimize the model from backbone to detection head and loss function.

| Model | Size/MB | mAP50 | mAP50–95 | GFLOPs | Parameters/M | Latency/ms | FPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv5n | 5.0 | 0.764 | 0.481 | 7.1 | 2.50 | 0.86 | 115.2 |

| YOLOv5s | 18.5 | 0.776 | 0.496 | 23.8 | 9.11 | 1.90 | 52.0 |

| YOLOv8n | 6.0 | 0.778 | 0.504 | 8.1 | 3.01 | 0.90 | 112.5 |

| YOLOv8s | 22.0 | 0.779 | 0.513 | 28.5 | 11.13 | 2.18 | 45.9 |

| YOLOv8-mobilentv4 | 11.2 | 0.734 | 0.468 | 22.5 | 5.70 | 1.20 | 81.2 |

| YOLOv8-ghost | 3.6 | 0.760 | 0.493 | 5.0 | 1.72 | 2.10 | 118.4 |

| SS-YOLOv8n | 2.3 | 0.799 | 0.510 | 3.1 | 0.88 | 0.77 | 128.9 |

The effectiveness of these individual lightweight techniques is further validated by ablation studies and comparisons of different pruning methods, as presented in Fan et al. (2024). Given pruning’s significant adoption rate (as highlighted in Fig. 6) and its direct impact on model size and computational efficiency, a deeper dive into its specific application within SS-YOLOv8n is particularly relevant. For instance, their ablation experiments (e.g., Table 4 in Fan et al. (2024)) show that each proposed module (Weighted Shuffle Convolutional Block 2f (WS-C2f), Spatial Context and Depth Head (SCDH), Probabilistic Intersection over Union 2 (PIoU2)) contributes incrementally to the overall performance improvement. Moreover, their comparison of pruning methods (e.g., Table 6 in Fan et al. (2024)) indicates that the chosen slimming pruning approach effectively reduces model size while maintaining or even enhancing accuracy, demonstrating its superiority over other methods like Lamp and Group-norm at similar pruning rates. These findings underscore the importance of a holistic approach to lightweight model design, combining architectural innovations with effective compression techniques. Ultimately, the success of SS-YOLOv8n serves as a compelling answer to RQ1, demonstrating that a strategic combination of architectural redesign, efficient module integration, and targeted optimization (such as pruning) can yield highly efficient YOLO models capable of superior performance in resource-constrained environments, effectively balancing accuracy with computational demands.

What are the main applications of lightweight YOLO models? How do datasets from different domains affect model performance? (RQ2)

Main applications of lightweight YOLO models (RQ2A)

There are eight main application directions in the screened literature, as shown in Table 10 summarizing the main application areas of lightweight YOLO models in the literature.

| Areas of application | Core methodology | Contribution and effectiveness |

|---|---|---|

| Intelligent transportation and automated driving | Integration with GhostConv, attention mechanism, model compression | Improved detection accuracy (e.g., pedestrian detection mAP of 87%), support for real-time (111.1 FPS) and edge deployment. |

| References: Arifando, Eto & Wada (2023), Li, Zhang & Yang (2023), Zhao, Ren & Tan (2024) | ||

| Industrial inspection and manufacturing | Cloud edge collaborative architecture, lightweight modules (SCDown, GhostConv), TensorRT optimization | Reduced model parameters (85.7%), improved real-time (20.83 FPS), and support for complex scene defect detection. |

| References: Chen et al. (2024), Lei et al. (2024b), Ruengrote et al. (2024) | ||

| Agricultural and environmental monitoring | Global attention Mechanism (GAM), multi-scale feature fusion, lightweight design | Improve disease detection accuracy (mAP@50 up to 88.4%) and support real-time detection of low-resource farmland environments. |

| References: Ming et al. (2024), Jiang et al. (2024b), Yang et al. (2024) | ||

| Public safety and health | Attentional mechanism (SAHI), model pruning, dynamic loss function (WIoU) | Improved small target detection (recall +7.3%), adapting to complex lighting and occlusion scenes. |

| References: Zhao et al. (2021), Xu et al. (2024), Deng, Zhou & Liu (2024) | ||

| UAV and remote sensing applications | Cross-scale feature fusion (HEPAN), lightweight detection head, edge-cloud collaboration | Enhances small target mAP (46.9%), reduces end-to-end delay (88.9%), and supports multi-UAV cooperative detection. |

| References: Dong et al. (2025), Chen & Zhang (2024), Zhang et al. (2024d) | ||

| Low power and edge computing | Quantization perceptual training, adaptive chunking, channel pruning | Realizes ultra-low power consumption (4.8W), high energy efficiency (20.9 GOP/s/W), and supports MCU real-time inference (0.6 ms/frame). |

| References: Wang et al. (2023a), Zhang, Mahmud & Kouzani (2022) | ||

| Medical & Biological Detection | Multiscale feature reconstruction, dynamic convolution, lightweight attention module | Improve the detection accuracy of complex underwater scenes (mAP@50=78%) and support precise positioning of laser weeding. |

| References: Song et al. (2024), Xu et al. (2024) | ||

| Infrastructure and energy security | Ghost-HGNetV2 backbone, lightweight detection head (RCD), multi-stage attention | Reduced parameters (54.86%), improved wildfire recall (+3.1%), and support for real-time monitoring in complex contexts. |

| References: Zheng et al. (2024) | ||

Cross-domain generalization: Lightweight YOLO models significantly improve the adaptability on resource-constrained devices through attention mechanisms, model compression (e.g., pruning, quantization), and multi-scale feature fusion.

Real-time and accuracy balance: Most of the literature reduces computation while maintaining accuracy by replacing backbone networks (e.g., MobileNet, GhostNet) and optimizing loss functions (e.g., WIoU, Focal Loss).

Edge-Cloud collaboration: Cloud-edge collaboration frameworks (e.g., ECC+) for industrial inspection and UAV applications significantly reduce end-to-end latency (88.9%) to support large-scale real-time tasks.

Small Target Detection Optimization: For agriculture and UAV scenarios, dedicated modules (e.g., HEPAN, DySample) are introduced to improve small target detection capability, with up to 10% mAP improvement.

Lightweight YOLO models show a wide range of application potential in the fields of intelligent transportation, industrial detection, agricultural monitoring, public safety, UAV applications, edge computing, medical detection and infrastructure security. These models achieve real-time and resource efficiency while improving detection accuracy through techniques such as attention mechanism, model compression and multi-scale feature fusion. Cross-domain studies show that lightweight YOLO models have significant advantages in small target detection and complex scene adaptation.

Impact of data sets on model performance (RQ2B)

A total of 61 articles in the screened literature used multiple datasets, with a special focus on dataset diversity and task applicability. The characteristics of different datasets (e.g., data volume, category diversity, contextual complexity, etc.) have a significant impact on the performance of lightweight YOLO models. Ten representative YOLO literatures on data diversity will be shown in Table 11.

| Study | YOLO improvement methods | Dataset diversity | Mandate applicability | Performance indications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yu et al. (2024b) | Lightweight LP-YOLO design based on YOLOv8 with integrated ECA attention and structured pruning | IP102 Pest dataset (covering multiple species of pests in complex field environments) | Real-time detection of agricultural pests on mobile | Parameters decreased by 70.2%, FPS increased by 40.7%, and mAP decreased by only 0.8% |

| Vinoth & Sasikumar (2024) | YOLOv8 incorporates TensorRT optimization and introduces a pixel-level depth refinement module | Low light environment datasets (rainy and foggy weather, night scenes) | Car camera, security surveillance | 4× faster inference with significant mAP improvement |

| Lei et al. (2024a) | Introducing depth separable convolution, dynamic upsampling, and coordinate attention mechanisms | Multi-scenario forest fire dataset (with smoke and small-scale flames) | Real-time fire monitoring for edge devices | 41% reduction in parameters, [email protected] = 99% |

| Shao et al. (2024) | Improved based on YOLOv8, integrating GSConv and coordinate attention mechanism | UAV-ROD, VisDrone2019 dataset (aerial imagery covering different heights and angles) | Vehicle/pedestrian detection from a drone’s point of view | The [email protected] of the VisDrone2019 dataset is 38.2%, with a model volume of 29.01MB |

| Lin, Yun & Zheng (2024) | Combining GhostConv and dynamic convolution to optimize detection heads for lightweight self-attention Modules | Self-constructed forest fire dataset (with smoke, small flames and complex background disturbances) | Early warning of fires in nature reserves | [email protected] increased by 4.2%, parameters decreased by 36.8%, FPS increased by 15.99% |

| Chen et al. (2024) | Improved based on YOLOv8, introducing Ghost convolution and quantization techniques | RailSem19 public dataset (railroad track complex scenarios) | Real-time track segmentation for edge devices | Accuracy 83.3%, FPS 25 (input size 480 x 480) |

| Liu et al. (2024a) | Design of C2f_AK module and BiFPN based on YOLOv8n with integrated coordinate attention mechanism | Transmission line anomaly data set (bird nests, insulator defects, etc.) | High-voltage line inspection with drone-mounted edge equipment | The [email protected] reached 94.2%, the parameters were reduced by 42.3%, and the model volume was reduced by 40.4% |

| Qiu et al. (2024) | Fusion of ShuffleNetV2 and LSKA attention mechanisms based on YOLOv8n | Self-constructed wheat grain dataset (four categories: healthy, germinated, diseased and damaged) | Seed sorting in agricultural automation | The mAP@50 reached 96.5%, the number of parameters was only 2.06M, and the FLOPs were reduced by 58.5% |

| Boyle et al. (2024) | Designing an adaptive chunking method based on TinyissimoYOLO to optimize computational efficiency | High-resolution image dataset (adapted to RISC-V microcontrollers) | Real-time detection of IoT devices (e.g. drones, smart sensors) | F1-score improvement of 89%, latency of 0.6 ms/frame, energy consumption of 31 J/frame |

A critical discovery from this analysis is that the diversity of datasets directly dictates the specific lightweighting strategies employed and profoundly impacts the model’s generalization ability and applicability. For example, the complex field environment of the IP102 pest dataset (Yu et al., 2024b) demands higher robustness from the model, while low-light environment datasets (Vinoth & Sasikumar, 2024) rigorously test the model’s detection ability under extreme conditions. These examples reveal a crucial insight: the inherent challenges posed by specific dataset characteristics (e.g., fine-grained details in pest detection, noise in low-light, occlusions in fire) directly dictate the *type* and *degree* of lightweighting and architectural modifications required. By introducing a specific attention mechanism or optimization module, the model can better adapt to the unique characteristics of the dataset and improve the accuracy and efficiency of task completion. This further underscores the nuanced trade-offs discussed in RQ1; for instance, aggressive pruning might be detrimental for small target detection datasets, necessitating more sophisticated architectural designs or knowledge distillation.

To achieve real-time detection on edge devices, many studies have strategically reduced model parameters and computation. For example, Yu et al. (2024b) achieved a 70.2% reduction in parameters through structured pruning with only a 0.8% mAP decrease, demonstrating the effectiveness of intelligent lightweight design. Concurrently, the significant improvement in FPS (e.g., 15.99% in Lin, Yun & Zheng, 2024) further validates the critical role of lightweight optimization for real-time performance.

The contextual complexity inherent in certain datasets, such as smoke and background interference in forest fire datasets (Lei et al., 2024a; Lin, Yun & Zheng, 2024), poses significant challenges to model robustness. Here, the insight is that targeted architectural enhancements are paramount. By introducing mechanisms like coordinate attention (Liu et al., 2024a), models can more accurately capture target features and improve detection accuracy even in highly cluttered or obscured scenes.

For resource-constrained edge devices, the optimization of parameter count and computational efficiency is paramount. For instance, Boyle et al. (2024) achieved an impressive latency of 0.6 ms/frame and energy consumption of 31 J/frame on a RISC-V microcontroller. This highlights that lightweighting, when coupled with hardware-aware design, enables efficient models for highly constrained Internet of Things (IoT) scenarios.

Overall Insights and Unresolved Challenges for RQ2

Existing studies demonstrate significant progress in optimizing lightweight YOLO models for target detection. A key discovery is that the interplay between application demands and dataset characteristics is a primary determinant in the selection and refinement of lightweight YOLO techniques. While efficiency is paramount, maintaining accuracy across diverse and challenging real-world data remains a central challenge. The combination of structured pruning and novel convolutional technologies has enabled significant improvements in inference efficiency while preserving detection performance, successfully applied in edge computing scenarios like drones and embedded devices.

However, current research still faces critical limitations:

Insufficient cross-scene generalization: Model training is often confined to single domains, leading to insufficient generalization ability across varied scenes. This reveals a critical research gap: the need for lightweight models that are not only efficient but also inherently adaptive and resilient to real-world variability. Adaptive migration methods are crucial for future exploration.

Robustness to dynamic interference: Studies on robustness under dynamic environmental interference are relatively weak. Future work should focus on enhancing real-time response capabilities by integrating dynamic network architectures that can adapt to changing conditions.

Energy-efficiency and hardware co-design: The energy-efficiency constraints of edge devices necessitate further optimization of model-hardware co-design. This involves developing lightweight architectures that are intrinsically compatible with low-power hardware, moving beyond mere software-level compression.

Standardized evaluation metrics: The variability of existing evaluation metrics across studies hinders comparability. Establishing unified standards is essential to accurately assess and compare the performance of lightweight models across different research efforts.

At the practical level, a scenario-oriented optimization strategy is recommended. This involves focusing on accuracy enhancement for specific tasks like agricultural automation (tiny target recognition) and prioritizing real-time performance for industrial scenarios. Customizing model structures based on hardware characteristics is also vital. Open community collaboration, including sharing lightweight models and industry-specific datasets, is essential to accelerate cross-domain application innovation. Ultimately, the continuous development of lightweight YOLO technology requires integrating algorithmic innovation, hardware adaptation, and domain-specific knowledge, with core breakthroughs focusing on generalization capability improvement and energy efficiency optimization to provide reliable support for practical deployment.

What hardware platforms are suitable for deploying lightweight YOLO models? (RQ3)

For new researchers entering the field of lightweight YOLO model deployment, understanding the interplay between model design and hardware capabilities is crucial. The selection of a suitable hardware platform is not merely about computational power; it’s a strategic decision based on a delicate balance of computational performance, power requirements, cost, and the specific demands of the application scenario. This section aims to provide valuable insights into the diverse hardware landscape for lightweight YOLO models.

Based on the filtered literature, Table 12 summarizes 11 key articles focusing on hardware deployment, offering a comprehensive overview of suitable platforms and their characteristics.

| Hardware platform | Applicable scenarios | Key performance indicators | Representative technologies |

|---|---|---|---|

| NVIDIA Jetson series | Real-time edge computing (vehicle, drone, surveillance) |

|

TensorRT acceleration, model quantization |

| References: Chen et al. (2024), Dong et al. (2025), Zhuang et al. (2024) | |||

| Raspberry Pi | Low-cost edge devices (video surveillance, basic testing) |

|

Lightweight network design (MobileNet, Ghost modules) |

| References: Dong et al. (2025), Liu et al. (2024b) | |||

| STM32 family of microcontrollers | Ultra-low power embedded applications (gesture recognition, industrial control) |

|

Model pruning, dynamic quantization, attention mechanism optimization |

| References: Moosmann et al. (2024), Mach, Van & Le (2024) | |||

| FPGA (e.g., Spartan-6) | Energy-efficient real-time processing (autonomous driving, pedestrian detection) |

|

Hardware pipeline design, online reconfigurable architecture |

| References: Wang et al. (2023b) | |||

| RISC-V MCU (e.g., GAP9) | Strictly resource-constrained equipment (sensor nodes, micro-drones) |

|

Adaptive chunk detection, soft F1 loss function optimization |

| References: Moosmann et al. (2024), Boyle et al. (2024) | |||

| ARM Cortex-M Series | Industrial automation (defect detection, equipment monitoring) |

|

Channel Attention, Dynamic Convolutional Optimization |

| References: Moosmann et al. (2024), Kang, Hwang & Chung (2022) | |||

| Cloud-edge collaboration system | Multimodal complex scenarios (autonomous driving, agricultural monitoring) |

|

Keyframe selection algorithm, model distillation |

| References: Dong et al. (2025), Nousias et al. (2023) | |||

This classification highlights the diverse range of hardware platforms, each tailored to specific operational contexts. For new researchers, a key takeaway is that the choice of hardware dictates the feasible lightweighting strategies and the ultimate performance envelope.

GPU-accelerated edge devices (e.g., NVIDIA Jetson Series): These platforms offer significant parallel processing capabilities, making them suitable for applications requiring higher throughput and more complex models than purely CPU-based solutions. The insight here is that while they are “edge,” they still benefit immensely from software optimizations like TensorRT acceleration and model quantization, which maximize the utilization of their powerful GPUs. For researchers, this means focusing on GPU-friendly lightweight architectures and leveraging vendor-specific optimization tools.

Low-cost general-purpose boards (e.g., Raspberry Pi): These are excellent starting points for budget-constrained projects or proof-of-concept deployments. The primary insight is that their CPU-centric architecture necessitates extreme model lightweighting (e.g., using MobileNet or Ghost modules as backbones) to achieve acceptable real-time performance. Researchers should be prepared for lower FPS compared to GPU-accelerated options and prioritize models with minimal computational demands.