Adaptive AI for competitive gaming: particle-swarm-optimized neural network for skill, engagement, and strategic evolution

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Siddhartha Bhattacharyya

- Subject Areas

- Adaptive and Self-Organizing Systems, Agents and Multi-Agent Systems, Artificial Intelligence, Optimization Theory and Computation, Neural Networks

- Keywords

- Real-time decision making, AI-human alignment, Strategic diversity, Neural network optimization, Opponent behavior adaptation, Particle swarm optimization (PSO)

- Copyright

- © 2025 Imtiaz and Mujtaba

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2025. Adaptive AI for competitive gaming: particle-swarm-optimized neural network for skill, engagement, and strategic evolution. PeerJ Computer Science 11:e3347 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3347

Abstract

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has transformed the development of game agents, providing new levels of interactivity and engagement. Real-time decision-making, as in fighting games, abets the need for adaptive and human-like behaviour for agents, making competition difficult. In the classics of fighting games, traditional AI is based on pre-programmed scripts, rules-based systems, or approaches that are easily predictable and provide less engaging gameplay. This paper presents an Adaptive AI based on Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) to adapt its strategies dynamically based on the opponent’s behaviour. The proposed approach enables constant real-time updates to neural network weights, thus making continuous learning, strategic adaptation, and variation in gameplay. The proposed AI is evaluated against multiple state-of-the-art AI models and human players with several performance metrics like Élő Rating, Glicko-2, opponent adaptation score, engagement score, and win consistency score. Experimental results show that the proposed Adaptive AI performs better than other AI in terms of its adaptability, strategic diversity, engagement, and the level of competitiveness it provides against human opponents, which is fair and challenging at the same time. From the findings, it is concluded that real-time optimization can be achieved by integrating PSO with neural networks, which helps improve capabilities in fighting games. The research brings value to the field by creating an adaptable AI agent that enhances user gameplay.

Introduction

Artificial intelligence has become an integral part of modern gaming, shaping both gameplay and player experiences (Filipović, 2023). AI agents have accomplished incredible achievements, from non-playable characters in open-world games to complex enemies in the strategy-based environment (Armanto et al., 2025; Younes et al., 2023). The most challenging application of AI is fighting games in which agents have to make fast, real-time decisions and show human-like behaviour, adapting to changing opponent strategies (Guo, Thawonmas & Ren, 2024). Games such as Street Fighter, Tekken, and Mortal Kombat demand strategic depth, quick reflexes, and dynamic planning (Lie & Istiono, 2022). Unlike turn-based or strategy-driven games, fighting games serve as promising candidates for developing adaptive AI agents because they require AI agents to make snap decisions that will take into account their prediction of the opponent’s behaviour (Marino et al., 2021; Sabato & De Pascale, 2022).

Traditionally, AI agents for fighting games are designed with a linear difficulty model where the only difference between agents is difficulty, that is, easy, medium or hard (Paraschos & Koulouriotis, 2023). Meanwhile, this can also quickly be done, but makes for an inaccurate experience when playing against human opponents (Martinez-Arellano, Cant & Woods, 2016; Oh, Cho & Kim, 2017). Using the same set of game mechanics, human players can run an extensive gamut of strategies to beat their opponents (Mendonça, Bernardino & Neto, 2015). For example, a player takes a defensive approach by utilizing the character’s abilities to keep a distance, a controlled pace of the match, and eventually win using their abilities. In contrast, another player continues to use abilities to pressure an opponent at a close distance. One of the key aspects of human play is that it is dynamic. Most fighting game AI agents stop evolving, and as a result, the game becomes static and ultimately less fun for players to play as they are aware of the outcome (Paraschos & Koulouriotis, 2023).

There are many challenges with developing truly adaptive AI for fighting games, as fighting games are games of pure instantaneous decision (with an agent selecting the correct action in the order of milliseconds), and the time between rounds is not desirable (Li et al., 2018). The difference between fighting game AI and most turn-based games is that AI for fighting games must analyze what an opponent is doing, determine what is best to attack or defend against, and execute a response in real-time (Ishii et al., 2018). As reinforcement learning (RL) and nature-inspired optimization techniques permit the AI agent to update strategies iteratively, they are very well suited (Mnih et al., 2015; Díaz & Iglesias, 2019). Most AI agents in fighting games have been using finite state machines (FSM), behaviour trees, or N-gram models. These techniques have a range of flexibility and learning capability, but typically with slow adaptation. While FSMs and behaviour trees yield deterministic behaviour for structured gameplay scenarios, these do not evolve with a human strategy (Armanto et al., 2025).

The most challenging part of AI agents for fighting games is stopping them from overfitting to a specific play style (Kim, Park & Yang, 2020). Most deep reinforcement learning (DRL) methods are trained against fixed opponent strategies; this leads to a scenario where the agent learned for training can only beat certain play styles but be beaten by humans playing different styles (Liang & Li, 2022). This challenge can be overcome by an effective adaptive AI that generalizes well on the variety of opponents it learns about and the different playstyles it can iterate on.

The key is balancing that challenge and fairness in an AI agent trying to fight. This is also the problem with an AI opponent: if they are too strong or exploit game mechanics unrealistically, players become frustrated and disengage (Guo, Thawonmas & Ren, 2024). As a result, the AI agent is not overshadowed by its predictability or ease of defeat. Adaptive AI aims to learn to construct a fair, balanced opponent that can deliver a dynamic challenge and is fun to play with in each match.

Conventional DRL agents are quite powerful but require a lot of training, which means they cannot be used on interactive and real-time games like a fighting game (Li et al., 2018; Hu et al., 2024). The common reinforcement learning (RL) models are generally used in an offline phase, or batch-based learning, which is then converted into action, but the resultant model cannot develop online or dynamical capabilities to adapt and to generalize. Such approaches typically make use of experience replay buffers and iterative backpropagation, which in dynamic environments exhibit latency and lack of stability (Liang & Li, 2022). Such delay-oriented processes hinder flexibility and responsiveness in fast-paced fighting games. In addition to this, DRL methods easily overfit to a specific opponent strategy and are afflicted with catastrophic forgetting when the behavior of the opponent changes (Guo, Thawonmas & Ren, 2024). In contrast, the proposed framework uses Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) as a gradient-free optimization part of the real-time optimization procedures and adjusts the weights of neural networks on-going during gameplay. In contrast with the classic RL paradigms, PSO does not require long convergence times or a calculation of a gradient, which allows fluid and efficient real-time adaptation of the systems in fighting games in a dynamic environment. Subsequently, PSO offers a more appropriate solution to online, continual learning in interactive, real-time situations.

Swarm intelligence is inspired by PSO, which is a population-based optimization algorithm, and the method of such search employs ideas from realizing a collective behaviour of a swarm (Fang & Wong, 2012). Compared to traditional reinforcement learning techniques that require intensive offline training, PSO facilitates continuous optimization and adaptation and thus arises as a good fit when the objective is to achieve real-time gameplay adaptation (Armanto et al., 2025). Natural optimization processes inspire the proposed adaptive AI. The proposed adaptive AI uses PSO-driven weight adaptation of a neural network for real-time strategic learning to reflect human-like behaviour and increase its strategic depth. This research proposes an adaptive AI fighting game agent that is adaptive to the change of human playstyles using a new hybrid learning approach.

The proposed approach combines PSO with a neural network, producing an adaptable AI agent for fighting games tested in Street Fighter. PSO allows the Adaptive AI agent to learn and adapt its strategy in the matches, whereas static rule-based AI agents follow the predefined script. This ensures more engaging and unpredictable gameplay as the AI is wiser in adapting to scenarios of evolving tactics of handling the opponent’s strategies during gameplay. Using this real-time learning ability, the proposed adaptive AI system provides players with a more immersive and complex playing experience for players, increasing the game’s appeal.

The proposed approach also finds an appropriate balance between exploration and exploitation. The proposed adaptive AI search mechanism can apply PSO-driven strategies to find a balance between searching for new methods and improving what is already reasonable. In fighting games, this balance is important because neither the AI agent relies too much on one tactic of use and can still change between many different opponents. The combination of exploration and exploitation serves as an essential element to ensure that the AI can propose a range of changeable gameplay experiences and thus reduce predictability and increase the player’s engagement. The significant contributions of this research are

An adaptive AI agent for fighting games using neural network optimization, using PSO to execute real-time strategic learning.

PSO approach that balances exploration and exploitation, strategic diversity, and decrease of predictability.

Demonstrating real-time adaptability such that the AI agent can dynamically adapt strategies according to the interactions with opponents having different play styles.

The rest of this article is structured as follows: ‘Related Works’ presents related work in fighting game AI and adaptive agents. ‘Methodology’ outlines the method by which the adaptive agent is created. The result analysis is in ‘Results and Discussion’. Lastly, ‘Conclusion’ of the article presents the study’s conclusion and suggestions for future research areas.

Related works

Real-time decision-making and highly challenging action space make AI research a problematic domain for fighting games. Early AI techniques in fighting games are mostly rule-based and FSM, making the game’s behaviours predictable and with certain limitations. Sato et al. (2015) proposed an adaptive fighting game AI, which was developed by switching between multiple rule-based controllers to make the AI more responsive to various in-game situations, but it lacked adaptability. Firdaus et al. (2024) found that the FSM effectively adds combo systems into retro games. The result of this study shows that the responsiveness of character movements can be significantly improved through the use of FSMs in a way that would improve the gameplay mechanics. These studies are mainly aimed at scaling the difficulty (i.e., making the game harder or easier), however, these are not aimed at human alignment, or human engagement. FSMs are deterministic, they are not flexible enough; therefore, hybrid approaches with adaptive AI techniques will be more appropriate (Zhang et al., 2024).

Opponent modeling and adaptive strategies

In fighting games, opponent modelling is key because it allows AI to predict and counter human players’ strategies for adaptive gameplay. Tang et al. (2023) proposed an Enhanced Rolling Horizon Evolution Algorithm (ERHEA), which uses evolutionary algorithms along with learning the opponent’s behaviour online in real-time, enabling the AI to make wise decisions if the opponent is behaving in a certain way. The ERHEA was tested in the Fighting Game AI Competition, but it outperformed the opponents and focused on winning. Künzel & Meyer-Nieberg (2020) proposed a multi-objective neuroevolutionary approach for better adaptation of AI in fighting games. The evolved AI had improved generalization to other opponents by considering multiple objectives, such as maximizing damage dealt while minimizing damage received. This is a case of generalization in dynamic environments.

Barros & Sciutti (2022) proposed a contrastive reinforcement learning model to learn individualized competitive behaviours. This model allows AI agents to create tailored strategies against certain opponents to deepen the competition, as it failed to perform well against humans with varying playstyles. The findings of Farahani & Chahardeh (2024) conclude using PSO to improve decisions in dynamic gaming environments, thereby supporting the application to fighting games.

Deep reinforcement learning in fighting games

Recently, hierarchical reinforcement learning (HRL) has reached a point where AI has become slightly more informed in fighting games. Black & Darken (2024) proposed an HRL based training framework to develop superhuman-level agents, surpassing the best human players, that unifies multi-model decision-making and di-observation abstraction. They focused on applying AI between competing players in competitive games, learning dynamically, and adapting to complex environments, but their model could not adjust to the human player. Training AI against various playstyles was mentioned, but the AI lacked player engagement. This strand of research focuses on opponent modeling and adaptation as opposed to difficulty scaling in that it aims at matching strategies to human play styles.

Halina & Guzdial (2022) proposed a diversity-based RL that is applied to fight game AI and found that agents trained with diversity have improved adaptability and engagement. AI performance in fighting games is not all won and lost, but it includes adapting, looking diverse strategically, and engaging the player in the experience (Gao et al., 2024). Relevant evaluation metrics for AI agents in fighting games beyond simple win/loss ratios must be used to measure their performance accurately. Several frameworks have been proposed to measure AI performance concerning engagement, opponent adaptation, and strategic diversity. Such a standard benchmark, including Glicko-2 ratings, opponent adaptation scores, and action diversity, is the FightLadder Benchmark (Li et al., 2024).

Zhang et al. (2024) suggests an evaluation method for AI-human alignment, in which AI agents can emulate human playstyles. According to their findings, the AI models trained in a human-like decision-making mode, and the games they developed using the models were more immersive and challenging for the players. This goal is achieved using the proposed adaptive AI that employs PSO-driven optimization to improve human-like adaptability.

Gao et al. (2024) made another notable work on human-agent collaboration in fighting games, focusing on the balance of AI difficulty to keep the player engaged. The research highlights the desire for AI agents that push and can be pushed without annoying or frustrating the players. Therefore, the proposed adaptive AI model resolves this issue by dynamically changing its difficulty according to the opponent’s performance, thus maintaining a balanced and enjoyable gameplay. Compared to the methods of difficulty scaling, the emphasis on engagement as a goal is a unique feature of this research: to keep the difficulty level high but not to become frustrated, the objective of human-AI interaction is quite associated with it. Regarding fighting games, the Shūkai system by Zhang et al. (2024) demonstrated its outstanding player retention rates due to DRL-based AI, which has significance for the AI-human alignment. From player-AI interactions, researchers can make AI play more effectively for the player while still balancing the play competitively. The given work poses the problem as human alignment designing AI, which resembles or complements human strategies, as opposed to merely adapting difficulty or win rate maximization. This research poses the problem as human alignment designing AI, which resembles or complements human strategies, as opposed to merely adapting difficulty or win rate maximization.

An overview of the existing research models and evaluation metrics is shown in Table 1. The literature underscores the importance of opponent modelling, adaptability, and human-like AI behaviour in fighting games. Although significant progress has been made in developing AI for fighting games, many research gaps exist. Most DRL based approaches focus on developing strategies that can outperform human players but do not create agent models that would imitate or adapt to humans with variations in play style. Our proposed AI adapts its strategies according to human opponents using the proposed PSO to address these gaps. Our model integrates PSO with neural networks to enhance real-time learning. Moreover, our method for benchmarking the adaptive AI is rigorous, using industry-standard performance metrics to assess its effectiveness.

| Article | Model | Evaluation metric |

|---|---|---|

| Firdaus et al. (2024) | Finite State Machine (FSM) | Action diversity and engagement score |

| Tang et al. (2023) | ERHEA | Opponent adaptation score and Élő |

| Künzel & Meyer-Nieberg (2020) | Multi-objective neuroevolution | Élő and strategic diversity |

| Barros & Sciutti (2022) | Contrastive RL | Opponent adaptation score and strategic diversity |

| Farahani & Chahardeh (2024) | PSO | Win rate and opponent adaptation score |

| Black & Darken (2024) | HRL | Élő, Strategic diversity, and Glicko-2 ratings |

| Halina & Guzdial (2022) | Diversity-based RL | Engagement score and adaption score |

| Li et al. (2024) | FightLadder benchmark | Glicko-2 ratings and action diversity |

| Zhang et al. (2024) | Shūkai system | Opponent adaptation score and engagement score |

| Gao et al. (2024) | Adaptive AI | Engagement score and opponent adaption score |

Although PSO has been explored in the past to learn strategy in simple or turn-based games (e.g., TicTacToe, board games), prior work has not been applied to real-time policy adaptation of a strategy in real-time games such as fighting games, which require quick and reactive responses. We will do that by merging neural network weight updating with an online experience replay system, along with PSO-based strategy evolution in real-time constraints.

Methodology

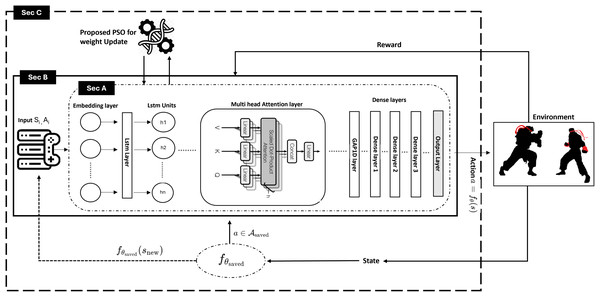

This section presents how PSO-enabled weight adjustment on hybrid neural networks is developed for an adaptive fighting game agent, as shown in Fig. 1. The short-term results are enhanced as the long-term results are better, and our approach does this. The objective is to have the agent adapt and learn its strategies dynamically in the context of the player’s actions so that the agent can optimally achieve the gaming experience. Also, this section explains the methodology with brief descriptions of the neural network structure, PSO weight tuning process, state and action encoding methods, and reward calculations.

Figure 1: Proposed PSO-optimized attention-based neural network for fighting games.

The environment of the Street Fighter II (based on the BizHawk Application Programming Interface (API)) presents structured state vectors, which are embedded and passed through a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) with attention and then dense layers generate Q-values in their output. The choice of course of action is made by an epsilon-greedy policy with decision latency that is not high (usually less than 100 milliseconds). Transitions are stored in a re-playing buffer and a multi-swarm PSO dynamically updates network weights when new states or opponent strategies are recorded. The average PSO update timing of the system was of the order of 2.3 s and action selection was occurring simultaneously.

Our adaptive AI is based on a neural network that extracts game features and sequence-based dependencies. In section A of the Fig. 1, the principal operational components of the neural network are an input embedding and an LSTM. A layer that makes use of an LSTM layer and a multi-head attention module, as well as thoroughly connected (dense) layers.

The game states combine with actions into state and action vectors, which consist of 28 real values for and 10 real values for . An embedding layer transforms the inputs into a reduced-dimensional continuous space. The embedding function works through the following definition:

(1) where:

is the embedding weight matrix,

is the embedding bias vector,

is the resulting embedded representation,

is the dimensionality of the embedding space.

An LSTM layer serves to capture the temporal dependencies that occur during gameplay. The hidden state determines the following calculation at time step as shown in Eq. (2).

(2) where:

denotes the tanh activation function,

and are the LSTM weight matrix and bias vector,

is the previous hidden state.

Implementing a multi-head attention mechanism helps the network focus on meaningful time steps. The definition of the attention operation stands as follows.

(3) where:

Q, K, and V are the query, key, and value matrices derived from the LSTM outputs,

is the dimensionality of the key vectors.

After the attention layer, a GlobalAveragePooling1D (GAP) layer aggregates the temporal information:

(4)

The predictive operation combines T sequence lengths with D features before normalization. The dense networks receive this vector input to generate the final reward prediction outputs:

(5) with:

and being the dense layer’s weight matrix and bias,

representing the Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation function.

Section B in Fig. 1 provides the current game state and the previous action as input to the neural network. The information gets to the network, which expects an action for the reward in response. The immediate reward prediction in Eq. (5) combines with other state-action predictions through temporal difference learning to create long-term return estimates for decision-making.

In decision-making tasks involving sequence-based data, the proposed adaptive AI has benefited from deep learning to a great extent. For long-term dependencies, capturing decision accuracy in such environments is essential. Advanced architectures are required for feedforward networks because they do not have memory capabilities. To address this challenge, a LSTM network is used with multi-head attention to process sequential data and efficiently select features.

As the game state and action representation is 38-dimensional, the model takes its first feeding of a 38-dimensional game state and action representation and processes it into an embedding layer. We pass it through a single LSTM layer with 50 hidden units to capture long-range dependencies in game sequences. The architecture of the neural network is shown in Table 2. However, the complexity of the model is increased by adding a multi-head attention layer on top of the model with four heads, allowing the model to concentrate on certain past states during the decision-making process selectively. The network consists of three fully connected layers with successively reduced dimensionality of units (150, 80, and 10 neurons, respectively), all using the ReLU activation function. This structured transformation ensures the final prediction is given optimal feature interaction before the final prediction. The reinforcement of learning processes uses the expectations of the expected reward as an output layer, made of a single neuron and a linear activation function, to predict the reward.

| Layer | Units | Activation function |

|---|---|---|

| Input (State + Action) | 38 (Game features) | – |

| Embedding layer | 50 | – |

| LSTM layer | 50 (Hidden units) | tanh |

| Multi-head attention | 4 Heads (Key Dim: 50) | Softmax |

| Dense layer 1 | 150 | ReLU |

| Dense layer 2 | 80 | ReLU |

| Dense layer 3 | 10 | ReLU |

| Output layer | 1 (Reward prediction) | Linear |

Although multi-head attention has many advantages, as claimed in Attention Is All You Need (Vaswani et al., 2017), a significant drawback is that such a single layer of attention cannot account for deep contextual dependencies. Stacking multiple attention layers may improve hierarchical feature learning, but at a higher computational cost, which does not allow it to be used in real time. Having thus balanced model expressiveness with the efficiency of computation, the architecture provides optimal performance in adaptive AI cases.

PSO implementation

In the dynamic gaming environment, PSO applies gradient-free optimization to optimize the complete weight set of neural networks. PSO did not run in a fixed time interval rather, it was called upon when new states or opponent actions were observed. The basic PSO procedure is summarized in Algorithm 1.

| Require: Initialize the particles of the swarm with ANN weights, velocity, and position randomly. |

| Ensure: Best Weights of NN |

| 1: |

| 2: while ending criteria not met do |

| 3: Calculate and evaluate the vitality (fitness) of particles. |

| 4: for each particle Pi do |

| 5: |

| 6: if vitality(Pi) < vitality( ) then |

| 7: |

| 8: end if |

| 9: end for |

| 10: Update each particle P’s velocity and position using Eqs. (6) and (7). |

| 11: end while |

| 12: Assign the weights of to the neural network. |

| 13: return model |

Each particle in the swarm represents a candidate set of neural network weights. The following equations update particles:

(6)

(7) where:

is the current weight vector of particle ,

is the particle’s velocity,

is the best-known weight vector of particle ,

is the best weight vector found by the swarm,

is the inertia weight,

are acceleration coefficients,

and are random vectors uniformly distributed over .

The fitness evaluation for each particle measures the scaled sums of the squared prediction errors compared to the target values.

Multi-swarm PSO

The basic PSO method receives additional enhancement through a multi-swarm approach, which speeds up exploration while preventing the occurrence of local optima. Different sub-swarms run simultaneously while their particles combine periodically to protect diversity. It starts with N sub-swarms (10 sub-swarms) that have a particle count of K each. All subsets of particles form a consolidated group . The algorithm removes particles that exhibit matchable similarities through Euclidean distance measurements below the threshold value . PSO updates occur between matches—a concurrent lightweight PSO update is used in a separate execution thread run in dynamic environmental conditions.

The multi-swarm PSO procedure is summarized in Algorithm 2.

| Require: Define Neural Network architecture, initialize N trained models, K particles per swarm. |

| Ensure: optimized weights for the Neural Network. |

| 1: Generate K particles randomly for each weight configuration. |

| 2: for each particle pi do |

| 3: Update velocity vi and position xi: using Eqs. (6) and (7). |

| 4: end for |

| 5: Evaluate fitness for each particle using the Neural Network. |

| 6: Identify local best for each sub-swarm. |

| 7: Merge all particles into . |

| 8: Compute distance for : |

| 9: Remove if . |

| 10: while termination condition not met do |

| 11: Repeat Steps 3–7. |

| 12: end while |

| 13: Select the global best particle from . |

| 14: Assign as the optimized weights for the Neural Network. |

Each particle calculates its fitness during the initialization phase. The provided notation represents explicitly the most optimal location known to each particle. PSO directly optimizes every weight in the network instead of delivering partial weight updates to the system through its operations. The values for , and came from sensitivity analysis tests.

Real-time adaptation with PSO

Unlike conventional deep learning methods, which are static (training happens before gameplay), we apply an adaptive (dynamic) set of neural network weights via PSO. The PSO algorithm provides the ability to adapt in real-time by continuously optimizing the agent’s decision-making function. The swarm is made up of each particle, which represents a set of neural network weights. The parameters used in PSO are shown in Table 3.

| Hyperparameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Number of particles | 40 |

| Number of sub-swarms | 10 |

| Velocity update coefficients | 1.5, 1.7 |

| Inertia weight | Dynamic (initially 0.8) |

| Update frequency | Dynamically during matches |

| Fitness function | Mean squared error (MSE) |

| Termination criteria | 500 iterations or convergence |

| Initial particle position range | [−0.99, 0.09] |

| Initial particle velocity range | [−0.99, 0.09] |

Only during match intervals does the PSO-based adaptation take place, so the AI agent is not limited to only after-match transitions. The proposed adaptive agent stores the information of its game in an experience replay buffer. A neural network consists of weights, each of which is a part of the swarm particle. They are assessed when the weight sets perform in the cumulative reward function. The weight adjustment process operates on the dynamic protocol of PSO. The agent’s real-time assignment is a set of weights performing at its best. It is sustained by keeping the agent in a regular update mode, which allows it to update its decision function to new plays via different gameplay methods. As PSO can provide proactive capabilities in the form of instantaneous refinements, PSO necessitates neither DRL models nor traditional training epochs.

When the initialization of the system begins, the Adaptive AI produces a population of particles, whereby at the initialization level, each of the particles represents a set of different models of neural network weights, as illustrated in Algorithm 1. Once at the start of the training of the agent, such particles are initialized through uniform sampling. Once this initialization is done, Adaptive AI is not randomizing its weights again with each match or trial. Rather, it has a constant experience replay buffer, which stores gameplay state-action-reward transitions. The AI usually uses strategies it learned during the game unless it spots a large change ( %) in the behaviour of the opponent. It is only after that that PSO is re-invoked again to re-adjust the weights of a neural network according to new issues of strategy. This enables the model to strike a balance and trade-off between the continuity in learning and capturing new tactics without involving pretraining or adaptation based on reset.

Information to allow the ability to continue learning up to the changing combat conditions is maintained in an experience replay buffer. To gain knowledge without instant feedback, the past state action reward triples from past gameplay are accumulated in the experience pool, which contains 100,000 past state action reward triples. Once the buffer was full the oldest entries would be deleted first (age-based pruning). To avoid excessive dependence on stagnant transitions, any segment of the trajectory whose cumulative reward was in the 10th percentile of the running distribution was also pruned. The remaining contents of the buffer were sampled evenly at random to give mini-batches that were used to update.

The adaptive AI does not achieve reliable learning results through experience replay since it retraces to learn how to make the right decision in the first place. The four constituent parts of every experience transition are the game state seen at the moment and the agent’s selection of action, the reward collected from this action, and the observed game state. The experienced pool allows it to learn the relationships between other opponents and develop capability in a variety of gameplay styles.

Every opposing strategy changes over time, which makes outdated experiences useless. Because the AI lacks an adequate data elimination system, it could persist with action optimization through obsolete methods. A periodic pruning system removes unnecessary, outdated experiences to solve this problem. An organized decay methodology initiates its sequence with a time-based evaluation where experiences exceeding 50,000 transits require marking for deletion. This feature stops the AI system from using old game strategies from a time when competition standards had evolved. The pruning approach identifies transitions that yield both poor rewards and unsatisfactory performance through cumulative reward tracking and then eliminates them from consideration. The system maintains only experiences with significant strategic value through this step.

The analysis of opponent playstyle depends on four behavioural elements, including how often they attack, blocking/dodging activities, and their positional movements alongside combo execution numbers. The statistical deviation analysis reveals any changes in the opponent’s strategy. When attack frequency or defensive behaviour evolves by 30% of raw values, the neural network stops using the former strategic approaches. The deviation calculation utilizes the set’s average percentage change of gameplay features. The system eliminates previously learned strategies through experience pruning whenever several predefined key metrics cross established thresholds to maintain its ability to handle new opponent tactics.

Continuous data logging during training gameplay sessions. Numerous performance measurements are collected during ongoing play, including the length of matches and the results, damage reports, and player activities. The metrics help researchers perform quantitative analysis of AI evolution, enabling them to enhance both reward functions and PSO parameters and create a network design structure. The logged information enables better model functioning while facilitating extensive evaluation of strategic modifications. The PSO-based neural network achieves updates through experience replay mechanisms, which improve decision functions. Update control systems handle the removal of obsolete information to protect AI from using invalid strategies and simultaneously prevent these methods from reinforcing unproductive methods. This integration allows the AI system to learn new opponent behaviours while maintaining high adaptive performance automatically.

Baseline implementations and fairness. All the baseline agents (Shukai, FightLadder, Brisket and Human-Agent Collaboration) were re-implemented according to the algorithm specifications in their original papers and open-source code (where available). The training budget and access to the data was compared to that of the proposed Adaptive AI in order to make it comparable. All the baselines were provided with the same number of simulated matches, both to train and evaluate, and all worked with the same representation of the state at 28 dimensions and 10 actions as in ‘Game Environment and State-Action Representation’. Integration requirements were normalized: all agents connected to the Street Fighter II API via the BizHawk emulator, and used the same state extractor data logger as well as the same timing constraints to execute an action. The data of human players were obtained directly through our 60 participants according to the protocol of ‘Environment Details’. These architecture decisions can be used to make sure that algorithmic variation is the cause of performance variation and not variation in data exposure, computational resources, or integration pipelines.

Game environment and state-action representation

We have used the Street Fighter game for the adaptive AI agent development and performance testing because the environment demands instantaneous decisions made while dynamically adjusting strategies during gameplay. The two competing players fight using their abilities to reduce the health meters of the opponent until their health runs out first. The unpredictable opponent behaviour demands an AI model that modifies itself following the observation of each game state.

The structured vector contains essential features for learning and making decisions. It represents a 28-dimensional vector of serious aspects of game state information, battle element positioning, and environmental conditions. We define each game state at time step as

(8) where:

are the health values of the agent and opponent.

and are the positional coordinates.

denotes movement states (jumping, crouching, attacking).

represents the current button press combination.

is the relative distance between the agent and the opponent.

is the remaining match time.

is a binary indicator denoting whether the round is over.

To facilitate efficient learning, the state vector undergoes an embedding transformation:

(9) where is the embedding weight matrix, and is the bias term.

The action space is a 10-dimensional discrete vector, encoding movement and attack choices available to the agent. The action vector at time is:

(10)

Each is a binary value indicating whether a specific action is executed. The agent selects actions by maximizing the predicted cumulative reward:

(11)

To ensure strategic variability, an -greedy exploration strategy is used:

(12) where ε controls the balance between exploration and exploitation. In all the reported experiments, the value of the is set to be equal to the isotropic value of a parameter, that is, all experiments used an identification of the greedy action as a probability with value = 0.9 and randomly picked a valid action with probability = 0.1. We did not use an annealing plan, to ensure that the exploration rate was the same in matches and to make replication easier.

Environment details

The experiments were all done with the API wrapper to the Street Fighter II using open-source BizHawk emulator. The API also offers an interface of discrete action execution and a data logger of structured state extraction. The state (health, position, motion flags, block status, distance, time, round information) was simply read out of the API data logger (see ‘Game Environment and State-Action Representation’). The action space had 10 discrete moves that were revealed through API. Rapid decision making (action selection) was always less than 100 ms and the asynchronous PSO weight updates were done at intervals of 2.3 s (as shown under ‘Results and Discussion’ as response time). The experiments were all implemented on a PC platform through BizHawk that guarantees emulation and reproducibility. The emulator and API wrapper could only be used in the academic research and this correlates with the open-source and end-user licence agreements.

Human player experimentation

The study involved 60 human players in evaluating the Adaptive AI’s learning capabilities against human opponents. Their experience levels were also used to select the players:

The empirical stage used an experimental paradigm of the within-subjects design. The sample included university members who were recruited voluntarily; expected were general familiarity with fighting games, but the sample was not previously introduced to the prototype agents in the current study. Each of the 60 participants played matches against all AI models; 10 games each and the skill distribution of players is shown in Table 4. This design allowed all of the participants to see a full range of AI behavior, which enables straightforward, similar evaluations of performance and interaction with models. The sequence of the match was randomly assigned to each player to avoid any bias of the ordering effect and possible bias of the participant. Thus, no AI model could be systematically presented in either the first or the last slot between trials. However, the participants were not selectively blinded against the particular AI agent that they played against. Even though there was little to tell about the internal architecture of each agent, they could have guessed identities based on observable differences in behaviour. This is a limitation that has been noted, and it is mentioned in the conclusion together with the overall transparency of the study.

| Skill category | Number of players |

|---|---|

| Beginner (Casual players) | 20 |

| Intermediate (Regular gamers) | 20 |

| Advanced (Competitive players) | 20 |

This study was in accordance with the ethical positions advocated in the Declaration of Helsinki on minimal-risk research on humans. Since the study process did not entail personal or identifiable information, psychological manipulation, and/or deception, there was no requirement to seek formal institutional review board (IRB) approval in the process of the study within our institution. Instead of the oversight of the IRB, a self-disclosed ethics compliance form was filled out and signed by the lead researcher. The research subjects were informed of the purpose of the study, and their participation in the study was under the process of informed consent, where they had the right to withdraw at any time they chose without resulting in any consequence. An aspect that should be made clear is that human players were merely used as gameplay rivals in the testing stage. They did not give subjective responses and did not have the role of annotators.

Ethical compliance and participant information. Respondents were recruited voluntarily within the university population and informed consent was received by having an explanation of the study objectives in plain language. The only basic familiarity with fighting games was needed to become included; no personal, sensitive, or health-related information was gathered. All the participants had 10 matches with each of the AI agents assigned in a random fashion and the only performance records of anonymity (win/loss, response time, engagement behavior) were obtained. No payment or physical goods were made and allowed the participants to back out without reprisal. The research was performed in line with the Declaration of Helsinki of minimal-risk human research. Since no identifiable information or interventions were used, the reproducibility package did not need formal IRB approval; however, a signed self-disclosed ethics compliance form and participant consent form was signed and are provided in the reproducibility package.

Élő and Glicko-2 settings. To update Élő we took the standard K-factor of 32, set all the agents to a rating of 1,500 and updated the rating after every match. In the case of Glicko-2, we have specific volatility constraint, which was 0.5, starting rating deviation (RD) of 350 and starting volatility of 0.06, which is in line with the literature of established defaults. These factors were constant throughout the assessments.

Reward function and agent decision-making

A reward function dictates how the agent integrates the learned rules into learning. The total reward at time is computed as:

(13) where:

.

.

rewards maintaining optimal distance and executing combos.

Our experiments were such that the set of values are: (damage dealt), (damage received) and (strategic bonus). These coefficients were chosen following sensitivity analysis, which was initially done in pilot studies, with various combinations of coefficients being tested to ensure that no single term was predominant in the reward signal. The values selected were a balance between offensive effectiveness and defensive stability and strategic diversity, and sustained throughout all the reported experiments.

Unlike policy learning methods, such as REINFORCE or Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO), this approach is chosen because Q-learning with PSO allows the model to refine its weights dynamically without relying on extensive experience replay (Jing & Weiya, 2025). The reward function delivers immediate rewards through damage metrics, but designers must maintain sustainable, long-term strategic development within the system. The performance enhancement through diversity calculation examines match victories achieved between our agent and human opponents using scalable measurement metrics. Through this system, the AI evolves beyond single-reward optimization by adapting its gameplay mechanics to achieve lasting competitiveness with human members of the game.

The individual gaming performance evaluation is an anti-overfitting mechanism that guards against successful but short-lived tactics that fall to human adaptability. Multiple match evaluations drive adaptive learning through the system, enabling the model to adjust its decisions by considering immediate benefits and long-term strategic performance outcomes. The complete methodology allows the AI to enhance its pattern of behaviour while maintaining fair play standards in game conditions.

An event-based timestamp logging guarantees that the response time evaluation of the fighting game AI is accurate. Whereas frame-based logging can only account for the game frame rate, this time-based logging offers exact measurement, so we can measure the time between an opponent making a move and the AI responding, while being close to the AI’s real-time thought process, we implemented it into our proposed adaptive AI. There are two measures of latency: (i) decision latency, the time during which the agent choosing an action is required to respond to a game state (less than 100 ms in average), and (ii) optimization interval, the time required to update asynchronously the PSO weights (reported in results Section 2.3 s on average). The two processes are executed simultaneously, and no time is lost in choosing the actions and optimization takes place in the background.

Evaluation metrics (engagement score, opponent adaptation score, and win consistency score) are mathematically defined in “Metric Definitions (Formulas and Parameters)” and all the normalization constants and aggregation parameters are fixed; the reproducibility bundle contains the corresponding code and scripts.

In order to establish transparency on the usage of resources and scaling, we report the proposed Adaptive AI computational budget. The entire set of experiments were performed in an NVIDIA RTX3080 (8 GB memory) with Intel Core i9 and 32 GB RAM, on the operating system (OS). The LSTM-attention version model took about 2.4 GB of concentrated memory, in the training phase, and also less than 1.0 GB, in the evaluation phase, on the GPU. PSO driven updates on-line incurred small overheads; every optimization period took an average of 2.3 s, and action selection reaction time was less than 100 ms (see Table 5 response time).

| Metric | Élő score | Glicko-2 score | Engagement score | Adaptation score | Win consistency | Response time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proposed adaptive AI | 1,550.32 | 1,548.56 | 0.95 | 0.91 | 0.88 | 2.3 |

| Shūkai (Zhang et al., 2024) | 1,532.45 | 1,530.12 | 0.92 | 0.89 | 0.88 | 2.4 |

| FightLadder (Li et al., 2024) | 1,508.23 | 1,505.14 | 0.80 | 0.77 | 0.76 | 2.9 |

| Brisket (Halina & Guzdial, 2022) | 1,511.67 | 1,509.23 | 0.88 | 0.85 | 0.84 | 2.7 |

| Human-agent collab (Gao et al., 2024) | 1,528.98 | 1,526.45 | 0.90 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 2.6 |

| Human players (Avg) | 1,500.00 | 1,500.00 | 0.98 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 2.1 |

The memory usage of the replay buffer of 100,000 experiences (1.2 GB) and then the checkpointing of network weights and PSO states together (200 MB) amounted to about 1.5 GB of host memory usage. To simulate 10,000 matches of the Adaptive AI, training the typical number of 36 GPU-hours was around the same time as the baseline agents, even trained on comparable budgets (‘Real-Time Adaptation with PSO’). For human validation 60 human subjects were involved, which demanded 12 more CPU-hours of collection and preprocessing of logs.

These values indicate that computing the cost of the multi-swarm PSO is moderate compared to those of traditional reinforcement-based learning baselines and that the approach can still be used to scale to real-time application in the fighting game application. Scaling longer bouts and more difficult settings is mostly limited by replay buffer size and graphics card memory, both of which can be addressed by means of distributed sampling and reconfigurations of PSOs which demand less memory.

Results and discussion

This section contrasts the proposed Adaptive AI agent with the state-of-the-art agents as well as human players. The aim is to identify whether PSO-based optimization makes gameplay more engaging, opponents more adaptable, and performance more efficient overall. In order to be able to interpret the results in a transparent manner, important evaluation metrics are stated in the beginning. Win rate and loss rate refer to the rate of matches won or lost against opponents. Action Diversity Score measures the difference between decision sequences in order to measure the level of behavioural unpredictability. Win consistency score measures the frequency with which results are achieved on 10-game trials, with higher scores meaning greater consistency in success. Opponent Adaptation Score grades the ability of the agent to modify the strategy in regard to the changing opponent behaviour based on performance variability, as an opponent’s style varies. Taken together, these indicators enable a multidimensional perspective of adaptive skill and strategic behaviour.

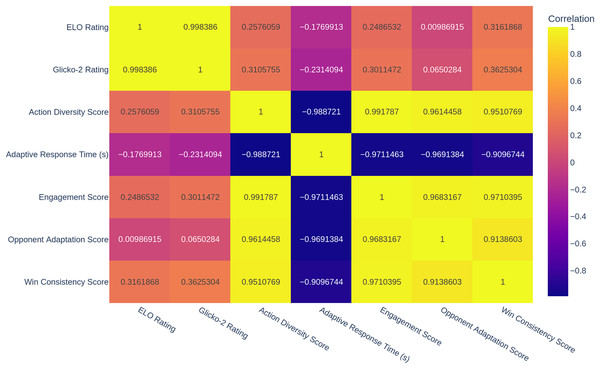

The correlation heatmap in Fig. 2 provides information about the relationships between different performance metrics. The correlation heatmap results are the mean scores of agents at the agent level by calculating means across the subjects. Élő Rating, Glicko-2 Rating, and win consistency score have a positive, strong correlation, meaning that the AI agents have a high skill rating if the nominal strategies are stable. The correlation of 0.96 between the engagement score and opponent adaptation shows a high correlation between AI models that effectively adapt to their opponent and provide more entertaining gameplay. This is congruent with prior research that fosters the idea that player engagement can grow by enhancing players’ adaptability. On the contrary, a −0.97 correlation score between response time and engagement score means that if an AI agent responds too fast, player engagement decreases. This finding is consistent with research such as Zhang et al. (2024), which showed that response time should be balanced with strategic variation. Despite the fact that Pearson correlations are illustrated in Fig. 2, they were calculated using agent-level mean values (N = 6 agents). Since the sample size is very small and inter-metric correlation exists, the magnitude of the correlation must be seen as a descriptive and not an inferential evidence.

Figure 2: Heatmap of per-agent average performance measures aggregated together and computed over 60 participants.

The Pearson correlation coefficients are depicted (see ‘Results and Discussion’ interpretation caveats).The Élő Rating is an established parameter used to measure the progress of the relative skill level of an agent by working out on game outcomes. Élő is also updated by increasing the score of each agent that achieves some unexpectedly positive result and decreasing it after some adverse result, thereby allowing the trajectories of learning to be monitored over prolonged time scales. More recently, Gao et al. (2024) confirmed that Élő-based measures are becoming widely used to measure increases in AI ability in the competitive setting.

In order to complement Élő, we used the Glicko-2 system, which is an expansion of the Élő system, where they added a rating deviation (RD) that models the uncertainty in the estimate of a skill agent. A low RD is indicative of consistent performance, and a high RD indicates unstable or poorly tested behaviour. In turn, Glicko-2 is a reliable tool for the analysis of improving or learning agents or those agents that adjust to new strategies (Li et al., 2024).

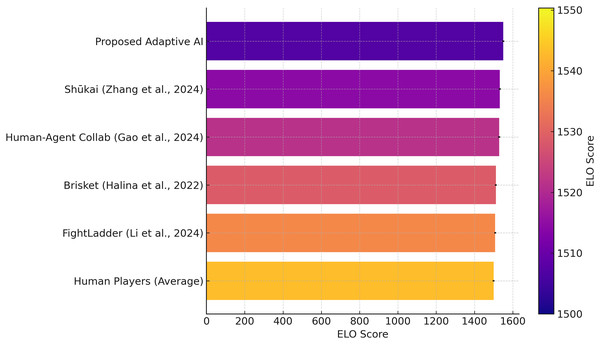

In the present work, Élő ratings and Glicko-2 ratings were updated following every game with respect to common parameters. The proposed Adaptive AI already has an Élő of 1,550.32 and a Glicko-2 of 1,548.56 combined, which presents an adequate degree of talent, stability, and trust in game-plays.

The agents from literature, including Zhang et al. (2024) had 1,532.45 and Glicko-2 1,530.12, Halina & Guzdial (2022) had Élő 1,511.67 and Glicko-2 1,509.23, and Li et al. (2024) had Élő 1,508.23 and Glicko-2 1,505.14, and all of these are outperformed by the proposed adaptive AI. Furthermore, the Human-Agent Collaboration model (Gao et al., 2024) with Élő 1,528.98 and Glicko2 1,526.45 also shows competitiveness with proposed adaptive AI and human strategies. The lower uncertainty of adaptive AI in the Glicko-2 system suggests a more stable and consistent performance, implying excellent and consistent gameplay as shown in Fig. 3. Error bars reflect 95% bootstrap confidence intervals from 1,000 resamples. The human player’s Élő and Glicko-2 ratings are 1,500.00, and the Glicko-2 rating is also 1,500.00. The challenge of outperforming human players compared to those who do, on average, perform a moderate degree of consistency. The Adaptive AI’s Élő rating of 1,550.32 and its Glicko-2 rating of 1,548.56 exceeded these human player averages, not only in its skill level but also in terms of consistency and consistency in performance. This further solidifies the competitiveness of the proposed adaptive AI because, despite its high performance and confidence level, it can still hold its own against the average human player. To statistically prove the fairness of the performance of Adaptive AI over other baseline agents, as well as human contestants, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was carried out on data summarized in ‘Results and Discussion’. the difference in per-participant Élő deltas of the Adaptive AI and the largest baseline agent was compared using a Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The unit of analysis consisted of individual participants ( pairs). The outcomes showed that there was a significant difference ( , ). The matched-pairs rank-biserial effect size was , which is a medium effect.

Figure 3: Élő values of every agents and human.

Error bars are 95% confidence intervals, which are taken through bootstrapped simulations of match outcomes of 1,000 resamples.The output (W = 15.0, = 0.031) demonstrates that the Élő score of the proposed Adaptive AI is much greater than those of other AI models and the average of humans with a 95 confidence level. This serves to substantiate the idea that the proposed Adaptive AI invariably stands out above the traditional systems with regard to skillfulness and versatility. A measure of the variability in agent skill estimates was obtained by building 95% confidence intervals (CIs) on Élő ratings through bootstrapped sampling. On each of the AI agents, 1,000 random replacement resamples of the outcome in the matches were drawn out of the overall set of matches, with recalculation of Élő scores in each resample. The outcomes of the CIs are illustrated as error bars in Fig. 3. These intervals provide a statistical measure of certainty in the rating of each agent and, in addition, support the fact that the proposed Adaptive AI is consistent in its performance.

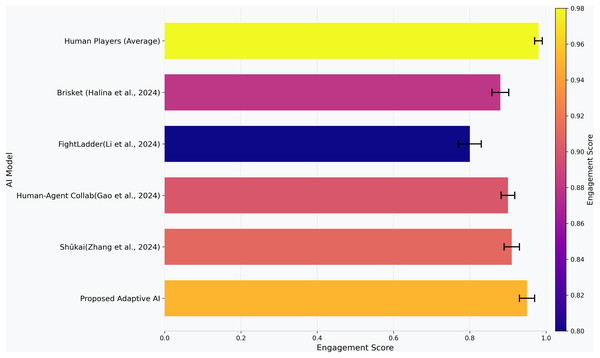

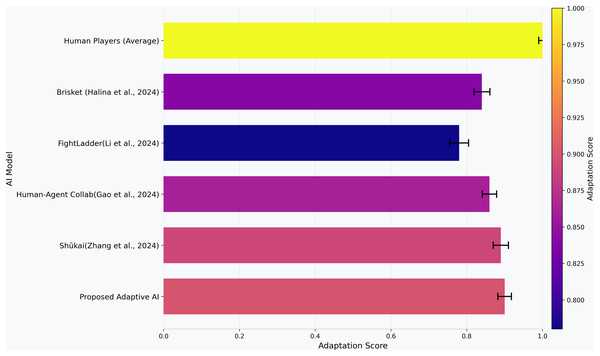

In the custom made measures of engagement and adaptation, we provide the 95% confidence intervals, acquired through bootstrap resampling with 1,000 replicates, which we represent in Figs. 4 and 5, in addition to the mean values to prevent inaccuracies of over-confidence through individual comparison. With the engagement score, we measure the deep and varied strategies based on the proposed adaptive AI’s decision-making during gameplay, shown in Fig. 4. Engagement score is a composite, 0–1 scale measure that reflects the ability of an agent to maintain the interest of a user by adjusting its behavior dynamically as the interest of a user wavers. It combines three fundamental aspects, which are variance in match duration, diversity in action, and time randomness. These dimensions are already proven to be strongly connected to the user experience of engagement, as these dimensions regulate perceived responsiveness, novelty, and level of challenge offered by an agent. The formulation can be associated with the visions of human-agent interaction as in Gao et al. (2024) with its focus on understanding outcomes over time and interactivity as critical in engagement, and Halina & Guzdial (2022) with its focus on diversity-driven learning as a process that induces immersion in players, increasing the behavioral variety among states. Normalization to the range of scores between 0 and 1 makes it possible to compare the scores directly across agents, and higher values indicate a more unpredictable, strategic, and human-like play. The proposed adaptive AI is associated with an engagement score of 0.95, which left the interactions during gameplay to closely align with the human verge of 0.98. This result highlights the ability of the system to produce game-play experiences of variation, immersion, and entertainment.

Figure 4: Engagement ratings (0–1) among agents.

Mean values are presented in bars, error bars are provided which represent 95% confidence intervals which have been estimated by bootstrap resampling 1,000 replicas (see “Metric Definitions (Formulas and Parameters)”).Figure 5: Scores of opponent adaptation (0–1) between agents.

All the bars contain the mean values; the error bars mean the 95% confidence interval estimated using bootstrap resampling 1,000 replicates (see “Metric Definitions (Formulas and Parameters)” formula).The Shūkai system (Zhang et al., 2024) scored 0.92, and the human-agent collaboration model (Gao et al., 2024) 0.90 also achieved high engagement secondary to dynamic learning, interactive gameplay, and, consequently, higher player involvement. Although FightLadder’s (Li et al., 2024) engagement score was only 0.8, it was lower than the average, primarily due to its less adaptive strategy and set of tactics, which were not as flexible. The Brisket model (Halina & Guzdial, 2022), which has an engagement score of 0.88, demonstrates moderate engagement through diversity-based reinforcement learning but is short of adapting to the chosen adaptive AI. The proposed adaptive AI’s dynamic decision-making and strategic variation contextually replicate a very engaging and unpredictable human gameplay, among the most engaging and enjoyable overall gameplay experiences among all the agents tested.

The opponent adaptation score is the coefficient that shows how fast the AI can adapt its model when new opponent play are introduced, i.e., the adaptability of the AI. The high score of 0.91 means that proposed adaptive AI learns fast from new and old opponents, as shown in Fig. 5. This demonstrates that the proposed adaptive AI has been able to generalize what it has learned from gameplay experience and evolve strategies, which is very applicable in dynamic and competitive environments. The Shūkai system (Zhang et al., 2024) scored 0.89 in adapting to the new challenges and opponents, which means that the adaptation score achieved by the Shūkai system demonstrates its ability to adapt to new challenges and opponents. The human-agent collaboration model (Gao et al., 2024) scored 0.87, showing the effectiveness of hybrid learning approaches in improving adaptability. On the other hand, in comparison to the FightLadder Benchmark (Li et al., 2024), the FightLadder Benchmark received a much lower score of adaptation of 0.77, which indicates it uses a more fixed strategy and less real-time learning and adaptation. The Brisket model (Halina & Guzdial, 2022), with a score of 0.85, is found to be moderately adapted due to diversity-based learning, which contributes to improved adaptability of the AI but is not as efficient as the reinforcement learning-based model in the adaptive AI. Overall, the results show that proposed adaptive AI can withstand and treat opponent adaptability on the side of the opponent and even perform well in competitive and changing environments.

Consistency score shows how well the AI does to win, irrespective of the match scenario, and the win consistency score measures the consistency it can deliver. This metric is crucial if we want to understand the robustness of an AI agent in real-life uses. A similar kind of evaluation has also been carried out in studies such as Li et al. (2024), emphasizing consistency’s importance in robust AI performance. The AI’s ability to learn and adapt to new opponents is also tested using the opponent adaptation score, which measures the AI’s efficiency in changing tactics to adapt and become more generalized. Such an approach is consistent with recent studies like (Halina & Guzdial, 2022) among others, and assessed that adaptability to opponent behaviour is a key factor for AI performance evaluation. The proposed adaptive AI surpasses all other AI models except the human player, with an adaptation score of 0.91. It can modify the strategies dynamically, making it more successful in competitive matches. By demonstrating that the proposed adaptive AI achieves a win consistency score of 0.88, a similar result as (Zhang et al., 2024) 0.88 and (Gao et al., 2024) 0.86, which means that it has consistently high win rates as shown in Table 5.

The response time metric measures the reaction time of AI agents in the decision-making process in environments such as fighting games, where speed matters the most for real-time performance. As stated in previous work, such as Zhang et al. (2024), games depend on the quickness of the AI to respond to in-game events; this metric is highly relevant to games.

Regarding response time, the proposed adaptive AI results in 2.3 s, although higher than other models in the literature. With this quick response time, the AI can make decisions on time in a real-time game experience, which enhances performance in different dynamic environments where the reaction speed is significant to the outcome. However, the response time of the Shūkai system (Zhang et al., 2024) is 2.4 s, which is 0.1 s slower than the proposed adaptive AI. A response time of 2.6 s for the human-agent collaboration model (Gao et al., 2024) reveals that adopting human strategies might incur minor delays in decision-making. With a response time of 2.7 s, the brisket model (Halina & Guzdial, 2022) is slower than the proposed Adaptive AI and Shūkai system, and the FightLadder benchmark (Li et al., 2024) response time is 2.9 s. These results show that proposed adaptive AI still has a slightly faster response time; it makes decisions quickly and performs best in a high-speed and real-time gaming environment. This enables it to be highly effective and competitive at a high level of strategy and execution speed.

To determine the internal validity of the proposed Adaptive AI, we used ablation experiments where key parts of the architecture were eliminated or changed. Table 6 shows the impact of such adjustments on all the evaluation metrics applied in Table 5

| Configuration | Élő score | Glicko-2 score | Engagement score | Adaptation score | Win consistency | Response time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proposed adaptive AI (Full model) | 1,550.32 | 1,548.56 | 0.95 | 0.91 | 0.88 | 2.3 |

| No PSO (Static weights only) | 1,420.10 | 1,418.35 | 0.76 | 0.68 | 0.72 | 0.9 |

| Single-swarm PSO | 1,482.25 | 1,475.60 | 0.84 | 0.79 | 0.80 | 1.8 |

| No attention (Vanilla LSTM) | 1,490.45 | 1,486.10 | 0.83 | 0.85 | 0.81 | 2.2 |

| PSO sensitivity (multi-swarm + attention, varied ) | 1,520.70 | 1,518.00 | 0.90 | 0.87 | 0.85 | 2.5 |

Table 6 shows that in all the conditions, no ablation variants had a higher performance compared to the full Adaptive AI. The removal of online PSO weight updates (“No PSO’) resulted in the sharpest decreases in rating systems and custom metrics, but the response time was reduced since no optimisation overhead was present. Maximizing optimization to one swarm also decreased Élő and Glicko-2 scores as well as adaptation and consistency, indicating the stabilizing impact of multi-swarm diversity. When attention-enhanced LSTM was substituted by vanilla LSTM, the engagement and consistency decreased significantly with adaptation decreasing as well (though not as low as the full model), which proves the importance of attention in capturing long-term dependencies. Lastly, the sensitivity analysis was performed by adjusting the PSO coefficients ( between 1.2 and 2.0) and the weight of inertia ( between 0.6 and 1.0) and keeping the multi-swarm and attention set-up. There was performance lowering at more extreme values but was always below the reported set of tuned full model ( , , initial) indicating that the reported settings were a near-optimal.

These findings substantiate the conclusion that the good performance of the adaptive AI is attributed to the synergistic effect of the PSO-based online learning system, multi-swarm optimization, and attention-enhanced sequence modeling, and that the given parameter setup gives the best trade-off between adaptability, engagement, and consistency.

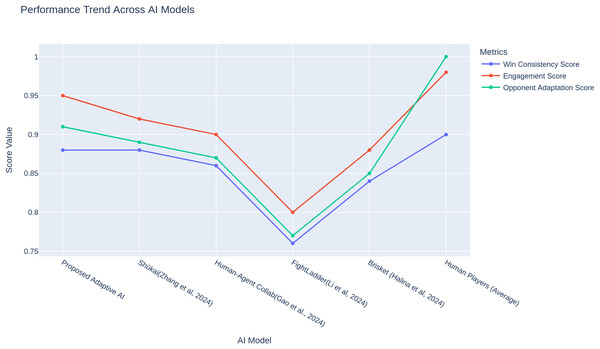

It turns out that the adaptive AI consistently performs at the top for these metrics more often. The proposed adaptive AI performance trend plot results in Fig. 6 show that adaptive AI always maintains high metrics scores, proving that its natural optimization-based approach is sufficient to sustain high performance in competitive duties. For instance, some models, including the FightLadder Benchmark (Li et al., 2024), are notable for decreasing performance due to reliance on their static strategies. On the other hand, brisket (Halina & Guzdial, 2022), human-agent collaboration (Gao et al., 2024), in contrast to those, have the performance increase in the models through their dynamic learning and opponent interaction. It is straightforward across different metrics how consistently adaptive AI performs highly, especially considering it can adapt and evolve its strategies over time, making it remain competitive against AI and human opponents. In the case of engagement, adaptation, and consistency measures, bootstrap resampling (1,000 replicates) was used to estimate the 95% confidence interval around the means to measure the uncertainty of the mean value. To prevent over-precision due to comparison of single values, these intervals are indicated in Figs. 4–6. The results show that the proposed adaptive AI model performs better than the other AI approaches in all key metrics. The proposed adaptive AI uses the dynamic strategy of adapting behaviour to play high-performance with diverse behaviour across different match scenarios. The proposed adaptive AI is a new standard for AI-driven opponents in fighting games, performing very well regarding the agility and speed taken in decisions, with a good balance between making decisions and various attack methods. In general, these findings support that adaptive learning models can bridge the gap between human and AI performance and thus would make gameplay more immersive, interactive, and diversely strategic.

Figure 6: Performance patterns of agents and human beings with regards to every measure of engagement, adaptation, and consistency.

Values were already normalized to (0–1) and averaged over 60 participants (see “Metric Definitions (Formulas and Parameters)”).The significance of this work is not related only to the particular case of Street Fighter II. By showing to the world that the online adaptation of the neural network weights can be facilitated using gradient-free, multi-swarm PSO, the research points to the overall mechanism of adaptive decision-making in dynamic settings. The proposed approach merges adaptability and interaction at the same time being computationally efficient in contrast to the earlier adaptive game AIs where the difficulty is limited only to its hardest possible mode or the visions are human-driven. This makes the approach a contender that makes applicable steps to further studies such as training bots to play various games with competitive rule setbacks, adaptive agents to simulation-based education, and scalable multi-agent coordination issues. The results introduced in the article can be generalized to other franchises and areas in further research with the help of the reproducibility package and thus support the originality and the applicability of the method.

Even though it was found that adaptive AI with the assistance of PSO is efficient in the context of a fighting game, it is necessary not to ignore certain drawbacks. First of all, the research is domain specific: all experiments were conducted within the framework of the game of a genre called Street Fighter II thus it is still unknown whether the strategy is generalized to other genres of games or more complex multimodal settings. Second, this state representation was done using engineered features which are exposed by emulator API rather than raw sensory inputs, which has contributed to reproducibility, but not efficiently reflective of the complexity of end-to-end perception pipelines. Third, the human experiment was not justified on the blinded identification, i.e. the subjects were aware of the fact that the experiment was playing against the AI or the baseline model, a possibility that might influence the reaction of the subjects. Future work versions will further scale up to provide whether more or less supplementary game franchises, accommodate additional end-to-end perceptual inputs with convolutional or vision-transformer encoders, and blinded or double-blind experiment environments as solutions to reduce any bias in human-agent evaluation.

Conclusion

We proposed an engaging, strategic, decision-making, adaptive AI for fighting games using PSO-based Neural Networks (NN). With efficient weight optimization by PSO, the proposed model enhances learning stability and convergence, attains faster adaptation to the opponent’s strategies, and keeps performance consistency. The adaptive AI is evaluated through a comprehensive analysis of skill proficiency, after the engagement, and real-time response efficiency, and its performance is superior to that of all existing AI agents and human benchmarks. The proposed model is verified experimentally, achieving an Élő rating of 1,550.32 and a Glicko-2 score of 1,548.56, which are very high skill levels and show performance stability. The engagement score (0.95) is very close to human players (0.98) and superior to human agent collaboration (0.90) and the Shūkai (0.92) alternative models. Additionally, the opponent adaptation score (0.91) also demonstrates that AI is more adaptable than Brisket (0.85) and FightLadder (0.77), which use more rigid predefined strategies. Moreover, the proposed agent can make real-time tactical decisions in a fast-paced, competitive environment with a response time of 2.3 s, which is a key factor. The results show that the NN-based adaptation mechanism combined with PSO enhancement can be a robust replacement for traditional reinforcement learning, yielding high skill retention, fast ability learning, and good response efficiency. These results suggest that such integration of AI opponents driven by PSO will yield engaging gameplay to the player and aid in long-term player retention. The aim of the future research will be to build on the current work by studying the concept of scalability over heterogeneous interactions among agents, including hybrid optimization methodologies and domain adaptation, to deepen the in-game experience of AI players. In the present research, the participants were not blinded specifically to the identities of AI, but the match order was mixed, and the consequences of the perceptual bias were considered. Further studies will involve more drastic control conditions to provide more empirical support for the process of human-AI interaction.

Appendix

Metric definitions (formulas and parameters)

Engagement score (ES)

Purpose. Measure the level of engagement in the play of an agent through variability, action diversity and time novelty. Range: .

Definition.

(14)

Terms and parameter values

-

•

(size of discrete action set used in this study).

• D: per-match duration (seconds). For each agent:

(Normalizing coefficient of variation to 1)

-

•

is Shannon entropy of empirical action distribution; it is normalized by to map to .

-

•

Temporal novelty via bigram diversity:

where is the count of adjacent action bi-grams observed which are unique.

Aggregation horizon. Calculated throughout the entire amount of evaluation of individual agent (all matches pooled by agent).

Opponent adaptation score (OAS)

Purpose. Adaptation rate of the agent between bouts. Range: (smoother directed adaptation means higher).

Segmenting and features. The matches are divided into 10-segments. For segment :

Each feature is normalized to :

: ratio between attacks and actions.

: ratio of block/ dodge to actions.

: mean inter-fighter distance normalized to .

: played average combo/per match divided by , with .

Definition.

(15)

Here T is the number of 10-match segments. The denominator is the L2 range when each of the four features lies in , normalizing each step to .

Note. The 30% behavior-change trigger explained in Methods, regulates the re-invocation of PSO in the middle of play; it is not included in the formula of the OAS.

Win consistency score (WCS)

Purpose. Reliability of results in repeated 10 match trials. Range: .

Definition.

(16) where is the number of wins in the th 10-match segment; a “consistent win segment” is defined by the fixed threshold .

Reporting linkage and computation notes

-

These definitions can be corresponded with Fig. 4 (ES), Fig. 5 (OAS), Fig. 6 (trend plot), and the summary statistics of Table 5.

Normalizations are intrinsic (no dataset min–max needed); action set size , bigram universe , combo cap , segment length matches.

The metrics are calculated on a per agent basis across the entire matches/segments and averaged on a per agent basis before being compared between agents.