Cyber security challenges for software vendors through a fuzzy-TOPSIS approach

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Michele Pasqua

- Subject Areas

- Computer Networks and Communications, Security and Privacy, Software Engineering

- Keywords

- Cyber security, SLR challenges, Software development, Fuzzy TOPSIS, Vendor organization

- Copyright

- © 2026 Alnajim et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2026. Cyber security challenges for software vendors through a fuzzy-TOPSIS approach. PeerJ Computer Science 12:e3337 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3337

Abstract

Cyber security has become a critical part of computer systems and recent technological developments have focused on making production and distribution processes more fluid and efficient. The introduction of Industry 4.0 and its significant impact on life and the economy highlights the importance of technological progress. However, modern technology faces several challenges. Cyber security is a major obstacle to software companies’ full adoption of automation and connectivity to transform production, logistics, and distribution. The proposed article is a systematic literature review to identify and document these difficulties systematically. The SLR identified 13 major cyber security threats, which are less than or equal to 25 percent. Through a questionnaire exercise, industry experts were consulted on the substance of the report. The identified cyber security challenges span a broad spectrum, encompassing issues like security issues/access of cyberattacks, lack of right knowledge, framework, lack of technical support, disaster issues, cost security issues, lack of confidentiality and trust, lack of management, unauthorized access issues, lack of resources, lack of metrics, administrative mistakes during development, and lack of quality, liability, and reliability. We prioritized and evaluated the severity of each cyber security problem using the Fuzzy-Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) technique to highlight the importance of our work further. Based on our recommended methodology, the most common issues were security issues and access to cyber-attacks, with a score of 0.768. Our work incorporates the cutting-edge Fuzzy-TOPSIS method, a powerful computational technique that has proven effective in handling fuzziness and ambiguity in many areas when applied to decision-making problems. The study should provide valuable information for software development companies facing cybersecurity threats. In addition, it provides vendors with tools to prioritize and assess risks associated with different security priorities. Considering all aspects, this work contributes significantly to the topic of cybersecurity and is a useful tool for companies trying to understand and address cybersecurity issues in developing software for fuzzy logic systems.

Introduction

Technology that once required physical access has now evolved into remotely accessible hardware systems controlled by software. Cybercrimes extend beyond software vulnerabilities, encompassing threats such as phishing, social engineering, and the exploitation of personal information through social media. Criminals employ these widely used chat strategies to steal identities by gaining insight into the individuals they are communicating with or by spreading viruses, spyware, and malware. It is essential to acknowledge that underprivileged individuals typically possess markedly reduced access to the internet compared to socially marginalised groups, who are statistically more inclined to partake in criminal activities (Jahankhani, Al-Nemrat & Hosseinian-Far, 2014). Customers appreciate exploring several virtual sales racks and executing immediate purchases online, nevertheless they need assurance that their credit card information and personal data remain safe and are neither intercepted nor obstructed from accessing the website. For numerous businesses, this is a severe issue. During an accessibility attempt, the hacker attempts to obtain unauthorized access to data. Access assaults may employ technological approaches that identify a systemic weakness and provide the attacker with electronic access to client data (Cavusoglu, Mishra & Raghunathan, 2004). Mechanisms for classification and prioritization based on threat modeling, vulnerabilities, and risk factors can be used to methodically evaluate cybersecurity issues. Vulnerabilities in software are flaws that allow attackers to endanger the authenticity, reliability, or privacy of processed data or that application (Kara, 2012). Risk-based frameworks like the common vulnerability scoring system (CVSS) help prioritize cybersecurity challenges based on their severity and exploitability. We discovered a significantly adverse market response to breaches in information security that entail illegal access to sensitive data; however, no substantial market response when the violation does not include access to sensitive data (Campbell et al., 2003).

Furthermore, companies frequently mislead with guarantees of highly effective security, sometimes going beyond the range of true security. Within certain conditions, this confidence can conceal dangers, which is to say, it is deceptive (Ruiz, 2019). This issue has evolved into one of the most significant threats to both the economy and national security (Nycz, Martin & Polkowski, 2015; Cao & Ajwa, 2016). While enterprises acknowledge the necessity for protection, evaluating its economic worth continues to pose difficulties (Cavusoglu, Mishra & Raghunathan, 2004).

APT refers to a continuous and effective cyber security challenge undertaken by cybercriminals against a specific target. APT firms and cyberattacks are being discovered at a rapid pace (Stuxnet and Black Energy) (Chinese Academy of Cyberspace Studies, 2019; Khan et al., 2022c). Discovering that an unauthorized viewer has entered your computer systems and altered sensitive data is a frightening event. A cybersecurity firm discovered that all tested cellphones and platforms used for purchases in stores, theatres, and resorts had serious security issues, including insufficient protection of Social Security numbers (Borky & Bradley, 2018). To participate in cybersecurity safety, at least two questions must be answered: What is the chance of an intrusion, and what are the possible outcomes? (Pfleeger & Rue, 2008).

According to the Norton Cybercrime Report 2011, 29.9 million Indians have fallen victim to cybercrime in India, costing the Indian economy $7.6 billion every year ($4 billion in direct losses and $3.6 billion in time spent resolving such crimes) (Kshetri & Kshetri, 2013). The five major affected economies are China’s Mainland, Turkey, China’s Taiwan, Ecuador, and Guatemala. Europe has the lowest impact rate (Chinese Academy of Cyberspace Studies, 2019). According to Cisco’s 2024 Cybersecurity Readiness Index, only three percent of global organizations are fully prepared to face today’s cyber threats. Moreover, 73 percent of respondents said that their company is likely to suffer disruption due to a cyber incident in the next 12 to 24 months. It is essential that organizations improve their cyber security measures to protect against evolving cyber threats. We have created two research questions to solve these cybersecurity issues, which are listed below:

RQ.1. What are the cyber security challenges faced by software vendors during software development?

RQ.2. How to assign values, classify, and prioritize the identified cyber security challenges?

The overview of the sections of the articles are as follows: ‘Related Work’ discusses various articles related to cybersecurity along with their challenges. ‘Research Design’ discusses the Methodology section by using SLR, in which different types of studies are selected through the year, databases, relevancy, empirical study, fuzzy set theory, etc. ‘Result Finding’ discusses the result and discussion through SLR findings and the Fuzzy-Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) application technique. ‘Discussion and Summary’ and ‘Conclusion’ are the discussion and conclusion of the article.

Related work

Previous articles analyzing cybersecurity challenges

Cybersecurity has become an essential part of computer systems, which indicates its increasing importance (Cabaj et al., 2018). In the digital world, the term cybercrime includes illegal activities involving the transmission of mathematical, symbolic or other information across local and international networks. These activities may include persons, objects, events, phenomena, or practices (Khan et al., 2022c). The new approach includes the adoption of new cyber risk insurance policies that provide compensation for damages caused by cyber-security breaches (Gordon, Loeb & Sohail, 2003). Denial of service (DoS) attacks often result in resource depletion, a continuously expanding category. To remedy this, one effective preventive strategy is to set a buffer size limit and consistently verify it whenever the buffer is used (Schneidewind, 2009). The financial impact of such cyberattacks is substantial, running into millions of pounds, euros, or dollars, posing a significant threat to individuals and enterprises alike (Mouheb, Abbas & Merabti, 2019).

Various cyber-attacks target the network layer, focusing on denial of service and malicious cloud computing (Acal et al., 2015). Spoofing is a common low-cost and high-return attack that entices consumers to disclose personal information via fraudulent websites that closely resemble legitimate websites (Chinese Academy of Cyberspace Studies, 2019). For businesses heavily dependent on information technology (IT), the cost of a cyber-attack may rival the cost of a decrease in sales to retailers (Campbell et al., 2003). In U2Su (user-to-root) attacks, the intruder first gains access to the default user account on the target system before exploiting a weakness to gain root privileges (Abraham, Grosan & Chen, 2005). According to Cerrudo (2015), Sensys Networks equipment lacked encryption, authorization and protection, which allowed the attackers to manipulate the traffic management system and to manipulate the traffic lights, meters and signals. Once the encryption key is compromised, the hackers have full access to the message.

Given the significant impact of cybercrime on the economy and on the security of companies and countries, it has become an urgent issue (Cabaj et al., 2018). Identifying and assessing the direct and indirect costs of security breaches is a complex task that is recognized by researchers and managers alike (Pfleeger & Rue, 2008). Vulnerability investigators often prioritize financial gain and reputation when disclosing their findings (Li & Liao, 2016). The cost of cyber-attacks, including hacking, ransomware, and spam, increased from USD 1 billion in 1996 to USD 56 billion in 2004 (Schneidewind, 2009). Outbreaks of malware targeting online banking services cost US banks $120 million, underlining the financial consequences of insufficient cyber security (Moore, 2010). As organizations store more and more sensitive and valuable data, the consequences of underinvestment in cybersecurity resources are becoming increasingly serious (Rue, Pfleeger & Ortiz, 2007).

The importance of cybersecurity has grown to the extent that it is now recognized as a distinct discipline (Cabaj et al., 2018). Extensive projects have been started in the systems and networking areas to develop capabilities for defending against new assaults. However, hackers think differently than application developers and are always devising novel attack strategies (Rastogi & Nygard, 2017). The old security strategy centered on devoting resources to safeguard important system components against known threats (Moller & Haas, 2019). Yet, in the cyber world, individually organized and sequential defenses are ineffective. Unless one or more safeguards serve as trip-wires to alert other defenders of an ongoing attack, which is of limited use, attackers can overcome each defense individually (Stytz & Banks, 2004). Flaws are consistently identified in email, web, chat, file transfer, and other services (Schneidewind, 2009).

As seen by prior data breaches and threats, network infiltration can occur by targeting the network’s weakest links (Lusher, 2018). Enterprises suffer large financial losses as a result of information security breaches, as it is difficult to eliminate all vulnerabilities completely. Still, organizations may organize their defense resources to reduce the financial effect of security breaches (Campbell et al., 2003). This move shifts the responsibility for dealing with insecurity on customers who lack the competence to fix the things they have purchased (Shostack, 2005). Cyberattacks make use of computers, networks, smart hardware devices, and other assets as agents, helpers, or targets (Moller & Haas, 2019). Currently, the bulk of cyberattacks focus on application vulnerabilities caused by software bugs or design flaws (Jang-Jaccard & Nepal, 2014). Many effective hackers are able to get access to victim networks using accessible public interfaces without using advanced hacking methods (Borky & Bradley, 2018).

Cybersecurity challenges for software vendors

Software vendors face distinct cyber security challenges concerning other corporate threats. Studies show that 60 percent of open-source code bases contain high-risk vulnerabilities, suggesting that increasing reliance on third-party components in software development has led to the emergence of new vulnerabilities (Ayala, Tung & Garcia, 2025). The SolarWinds incident (Mızrak, 2024) shows that vendor systems are particularly vulnerable to supply chain attacks using compromised updates or dependencies as a vector of attack. Khan et al. (2022c) noted that legacy systems in vendor organizations often lack modern encryption standards (Cerrudo, 2015), and 78 percent of vendor breaches are caused by insecure APIs or misconfigured cloud services (Wicky, Willie & Eshleman, 2020).

Prioritization techniques in cybersecurity context

Prioritization techniques like Fuzzy-TOPSIS have become popular in cyber risk assessment because they effectively manage ambiguity in expert opinions. The work of Arellano et al. (2024) demonstrated the effectiveness of the ranking of cloud security threats, obtaining 89 percent agreement among reputable experts. Comparative studies show that Fuzzy-TOPSIS outperforms Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) in terms of reliability, reducing the discrepancy by 40 percent (Wardana & Rianto, 2021). Recent applications include: priority fixing of vulnerabilities (Djambazova & Andreev, 2023), security budget allocation for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (Dietz, 2023), zero-day vulnerability scorecards (Mohideen et al., 2024), and the Cisco 2024 Cybersecurity Report which shows that 62 percent of vendors now use multi-criteria decision making (MCDM) techniques, with Fuzzy-TOPIS being the second most adopted after VIKOR (Agaba et al., 2024). For several enterprises and businesses related to wired networks, wireless networks, ad-hoc networks, the Internet of Things, etc. is a serious problem (Khan et al., 2022a, 2019, 2020; Farooqi et al., 2019; Khan et al., 2021a; Hosseinzadeh et al., 2022; Lansky et al., 2022; Adnan Khan et al., 2022; Khan et al., 2024; Khan, Abbas & Khan, 2016; Guo et al., 2023).

Research design

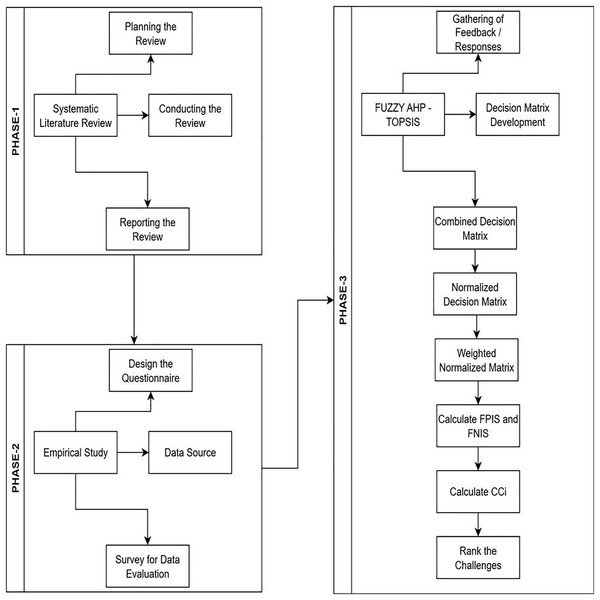

The research design is organizes into three phases, as illustrated in Fig. 1. In phase 1, using the systematic literature review (SLR) tool, we identify all cyber-security problems that negatively affect software companies during the development of software. In the second phase, we developed a questionnaire survey to empirically validate all recognized cybersecurity challenges from the perspective of business practitioners. In the third phase, we used the fuzzy-TOPSIS approach to rank the recognized cybersecurity challenges.

Figure 1: Research design.

Systematic literature review

We employed the SLR to identify significant cyber security issues, which produces more efficient, practical, and detailed outcomes than a standard literature study. In this research study, we followed the recommendations of Kitchenham & Charters (2007). The three important stages in this SLR guidelines are as follow.

Planning the review

This stage contains the following important steps which are:

Research questions

To answer the research questions stated in the Introduction, a SLR was carried out. In particular, the SLR offers evidence-based insights that directly support the study of RQ1, RQ2, and RQ3, guaranteeing that the security challenges identified are in line with the goals of this research.

Searching of data sources

The choice of data-gathering resources is not a simple issue; we used a technique from Chen, Babar & Zhang (2010) and Khan & Keung (2016) to build the proposed research study. The following databases are Google Scholar, IEEE, ScienceDirect, ACM, and Springer. We have found a total of 169 articles from these data sources through primary selection.

Development of search string

We created a search string in this stage to perform a search on every database source. We could collect information from these sources after creating the primary strings and their variants. To concentrate on the keywords and subsequent alternatives, we utilized the Boolean operators ‘AND’ and ‘OR’. ((“Software development” OR “secure software development” OR “software evolution” OR “software maturing” OR “software growth”) AND (“Cybersecurity” OR “cyber forensics” OR “Secure computing” OR “electronic information security”) AND (supplier OR trader OR seller OR contractor) AND (Challenges OR issues OR problems OR barriers) AND (practices OR solutions OR procedures OR methods)).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To obtain relevant articles for our study, we used specific guidelines for search strings based on exclusion and inclusion criteria collected from the literature. The later criteria enabled us to focus only on those research articles that fulfil the proposed study’s requirements, while the exclusion criteria allowed us to remove irrelevant articles that do not match our search terms. It is worth noting that other researchers have employed a comparable approach to obtain relevant literature.

Quality assessment of publication

The publication’s quality will be determined only by the answers to the three questions listed below.

-

•

Does the researcher highlight the cyber security issues that software vendor firms encounter that could harm software development?

-

•

Does the author identify the cyber security approaches?

-

•

How to assign values to the recognized security issues, as well as identify and rank these key security challenges?

Conducting the review

Final selection of the articles

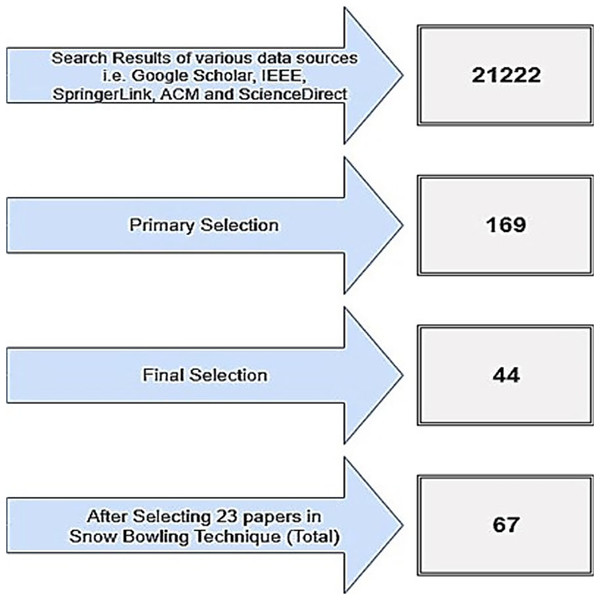

Originally, by searching through various data sources using search strings, we were able to find a total of 21,222 research articles. Using the procedures described in the previous section, we were then able to locate 169 original research publications. By applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 44 relevant research articles were finally selected, but they were of minimal size and did not meet our requirements, so we used the snowballing method to find 23 relevant research articles. Eventually, 67 research articles were selected for the data collection process, as illustrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Phases for selection of final study.

Data extraction and evaluation

The data-gathering step follows the primary study of the chosen published studies and is aligned with the research questions. The 67 research articles found and chosen for the suggested SLR were carefully evaluated with the assistance of a secondary reviewer (supervisor). Through the planned SLR study, we first determined the concept of the research study, concepts, and security challenges. Finally, 13 critical cyber security challenges have been identified.

Reporting the review

Quality evaluation

We conducted a performance analysis of the relevant literature after selecting relevant research articles. We evaluated a 50% mark as a quality target significance for our chosen related articles incorporated.

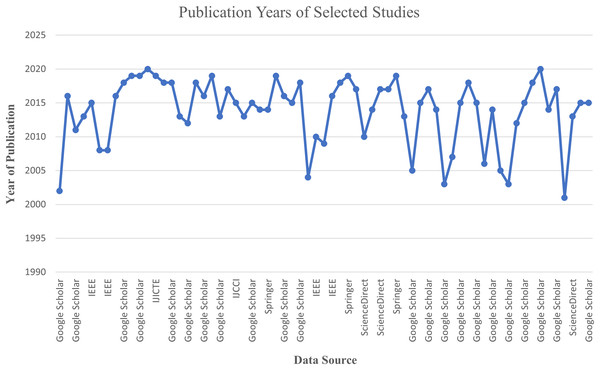

Publication year

During the collection of data phase, SLR retrieved all feasible related details from the 67 issued publications, containing the release year, as shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Year of publication.

We tried to include the newest articles in our extraction phase, our chosen research study reveals its expanding pattern of publishing, published from 2001 to 2025, and recognized relevant articles in the domain of cyber security challenges from 2001 to 2025. As a result, this analysis indicated that cyber security is a very hot and wide topic of current research.

Empirical study

The empirical research approach is particularly effective and essential for collecting globally distributed data sources. To prevent ambiguity and uncertainty, we selected a questionnaire survey technique with Google Survey Form to address RQ1 and RQ2. This approach is an effective and useful method for gathering responses from geographically separated people. The survey was conducted systematically by several researchers to ensure rigor and neutrality. This structured approach ensured that the study followed the SLR methodology of Kitchenham & Charters (2007) and maintained transparency and reliability. The roles were as follows:

Researcher 1: Designated the initial search of the database and carried out the screening based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Researcher 2 and 3: Assessed and validated the final selection of the articles.

Questionnaire development

Some critical cyber security issues with the help of SLR are recognized. We used Google Forms (docs.google.com/forms) to perform an online questionnaire survey to verify the results of SLR. Our questionnaire survey is divided into three parts. Each individual’s thorough information is discussed in the first section. The closed-ended and open-ended questions about cyber security issues encountered by supplier companies during software development as highlighted in the SLR. If participants add any additional security challenges to the ones already mentioned, they will be asked open-ended questions. The third part outlines the SLR practices that were discovered for these security issues, and this is where we may directly ask the respondents about anymore, lesser-known practices that they apply in their firm to protect software development against cyberattacks.

Assessment of questionnaire survey for pilot study

The proposed questionnaire survey was evaluated by IT specialists, who conducted a pilot study to propose improvements, if necessary, and to ensure that the produced questionnaire was easily understood. We invited 35 external IT professionals through email from the object demographic of the software engineering area for the experimental project, involving one specialist from the university, and the remaining from IT national and worldwide enterprises. They offered certain improvements after a thorough evaluation of the questionnaire survey form, such as “the profession entitlement, skill, and permanent position is compulsory” and “to reference the three Likert scales instead of the five Likert scales in the questionnaire”.

Professional personnel were selected based on their expertise in the field of software development and in the field of cyber security. One of the selection criteria was that the candidate had at least five years of experience in the field of software development or cybersecurity, and knowledge of the security threats of software vendors, representing different sectors such as cloud security, enterprise software, healthcare, and financial services, and diverse geographic locations, including specialists from Asia, Europe, and North America. This choice ensured a comprehensive understanding of cyber security issues across the different software vendor ecosystems and the regulatory environment.

Analysis of survey data

The frequency statistical method was used to assess our survey data replies, as shown in Table 1. According to Bland (Khan & Keung, 2016), “an effective technique for analyzing participants’ opinions throughout the set of variables is the frequency analysis technique.” For the study of survey data, various scholars have used this technique (Inayat et al., 2015; Noy, 2008; Bland, 2015; Hallgren, 2012).

| AHP/SAATY scale | Linguistic scale | Triangular fuzzy scale | Triangular fuzzy reciprocal scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Equal importance | (1, 1, 1) | (1, 1, 1) |

| 3 | Modest importance | (2, 3, 4) | (1/4, 1/3, 1/2) |

| 5 | Strong importance | (4, 5, 6) | (1/6, 1/5, 1/4) |

| 7 | Very strong importance | (6, 7, 8) | (1/8, 1/7, 1/6) |

| 9 | Extreme importance | (9, 9, 9) | (1/9, 1/9, 1/9) |

Fuzzy set theory

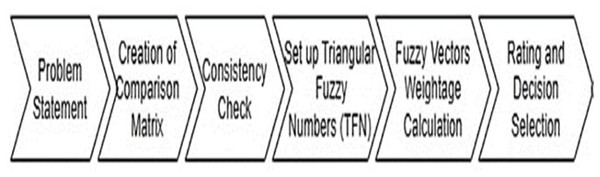

The fuzzy set theory was created to eliminate the ambiguity or fuzziness caused by human perceptions in multicriteria decision-making (MCDM). Alshahrani et al. (2022) developed this set theory, where the primary computational methods of opacity concern are fuzzy sets and fuzzy logic. The fuzzy set theory was crucial in demonstrating the fuzzy and uncertain data. Figure 4 depicts the realistic procedure of the fuzzy analytic hierarchy process (F-AHP), which includes all six steps (Dwi et al., 2018).

Figure 4: Block diagram of F-AHP steps.

Definition of triangular fuzzy numbers

In fuzzy decision-making, inaccurate or imprecise data is represented by triangular fuzzy numbers (TFN). The Fuzzy AHP and Fuzzy-TOPSIS approaches are combined with TFNs in this work to prioritize cybersecurity issues. Experts assign linguistic values such as equal importance, modest importance, strong importance, very strong importance and extreme importance after evaluating criteria pairwise using TFN-based decision-making. The notation (l, m, and u) represents a TFN, where:

• The l (Lower Bound) reflects the fuzzy number’s lowest possible value.

• m (Mean Value) represents the middle or most likely value.

• The upper bound (u) represents the maximum possible value.

The membership function F(x) is used to determine the fuzziness of each integer, which spans from 0 to 1, ensuring that uncertainty in expert assessments is accurately recorded and processed (Wu & Tan, 2006; Ecer, 2022).

The fuzzy TOPSIS

TOPSIS is a key and pioneering technique in the field of MCDM. It should be mentioned that this strategy is based on decision-makers’ choices and focusses on the solutions that are farthest from the unfavourable perfect solution and the closest to the favourable ideal solution (Hwang et al., 1981; Zhang et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020; Mokhamed et al., 2023). This strategy might have a major influence on the cost-benefit criterion, with the ability to either improve benefits while lowering costs or decrease costs while increasing benefits (Zyoud et al., 2016; Kannan, de Sousa Jabbour & Jabbour, 2014; Rostamzadeh & Sofian, 2011; Khan et al., 2022b).

The traditional Fuzzy-TOPSIS approach has several disadvantages in MCDM, particularly when it comes to managing the uncertainty of cyber risk assessment. Difficulties in decision-making are an important part of the complexity of the process (Kaya, Asyali & Ozdagoglu, 2018; Ilieva, 2019). Fuzzy-TOPSIS is therefore a useful tool to resolve these uncertainties in the prioritization of cyber threats, especially when several expert opinions are involved (Memari et al., 2019; Özdağoğlu & Güler, 2016; Eyüboglu & Çelik, 2016; Alshahrani et al., 2022).

Several technique in cybersecurity. Fuzzy-TOPSIS was used for Cyberthreats in critical (Haghshenas et al., 2017) using Systematic Literature review (Khan et al., 2021b; Mokhamed et al., 2023; Khan et al., 2022b; Turskis et al., 2019).

We have studied well the fuzzy TOPSIS procedures for prioritizing cyber security concerns faced by seller companies during software development. The following are the detailed instructions for executing fuzzy TOPSIS:

Step 1: Here the proposed method rated an established criteria, by which the proposed method presented the fuzzy triangle scale the fuzzy triangular scale presented in Table 1 (Ecer, 2022; Khan et al., 2021b).

-

List all alternatives

Identify evaluation criteria

Determine the weight of each criterion (often through expert opinion)

Identify decision makers if multiple experts are involved

Step 2: A fuzzy performance matrix is created to determine the effectiveness of every expert decision-maker. Assume we have a team of “j” decision-makers, notated by , with “n” alternatives, indicated by , and “m” criteria, symbolized by , where R(nm) implies the rank of every alternative A(n) of an expert decision-maker concerning the criteria represented by C(m).

(1) where R(nm) implies the rank of every alternative A(n) of an expert decision-maker concerning the criteria represented by C(m).

Step 3: The overall fuzzy rating for each criterion and its alternatives is computed in this step. Following that, a combination decision matrix will be created. The fuzzy rating priority of weights for “K” decision-makers is Xij = (lijk, mijk, uijk), where and , and the resulting fuzzy overall rating Xab of the findings concerning each criterion, along with the alternatives, is given as follows:

where

(2)

Wij = (wj1, wj2, wj3) is the formula for determining the cumulative fuzzy weights of each criterion, indicated by Wij.

(3)

Step 4: Here a normalized matrix is created using the combined decision matrix and weight criteria. (P) represents the resulting fuzzy normalized decision matrix, which can be expressed as follows:

(4) where upto “m” and upto “n” and

(5)

(6)

Step 5: The evaluated criteria “Wj” is multiply with weighted normalized matrix “Pij”, which is represented by “V” for every criterion.

(7) where Vij = Pij × Wj.

Step 6: In this step fuzzy negative ideal solution (FNIS) and fuzzy positive ideal solution (FPIS) are computed which are as follow:

(8)

(9)

Step 7: Using the Euclidean distance formula, we will calculate the distances between all of the possibilities from FPIS and FNIS in this stage.

The distances “di*” and “di−” between the FPIS and FNIS are determined as follows for each choice :

(10)

(11)

Step 8: The closeness coefficient index, or “CCi,” value is determined for every possibility once all the results for the FPIS and FNIS have been determined. Using the given equations, the CCi values demonstrate the FPIS and FNIS simultaneously:

(12)

Step 9: We will rank all of the possibilities in this stage. The best option will be the shortest distance from fuzzy positive ideal solution and the longest distance from fuzzy negative ideal solution.

Result finding

SLR findings

For RQ1, the suggested method used the SLR methodology to identify 13 major cybersecurity problems. The extraction method begins by evaluating 149 primary articles against preset inclusion and exclusion criteria. At this level, 44 research articles were chosen. Because the number of final articles was quite small, the snowballing approach was used, resulting in the inclusion of an extra 23 articles. As a result, a total of 67 articles were selected for analysis. Through qualitative coding of these investigations, common themes were found, aggregated, and evaluated by domain experts, resulting in the identification of 13 significant cybersecurity challenges, which are described in Table 2. These cybersecurity challenges are “Cyber Security issues”, “Lack of proper awareness”, “Lack of proper framework”, “Skillful staff absence”, “Lack of Quick response in emergency”, “High expenses”, “Lack of privacy”, “Management issues”, “Malicious activities”, “Resource absences”, “Confusion on System measurement”, “Human error during software development” and “Non reliability”.

| S.No | Challenges in CSCM | Frequency (N = 67) | Percentage of factors occurrence |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cyber security issues | 39 | 58% |

| 2 | Lack of proper awareness | 32 | 48% |

| 3 | Lack of proper framework | 32 | 48% |

| 4 | Skillful staff absence | 29 | 43% |

| 5 | Lack of quick response in emergency | 27 | 40% |

| 6 | High expenses | 26 | 39% |

| 7 | Lack of privacy | 25 | 37% |

| 8 | Management issues | 22 | 33% |

| 9 | Unauthorized access issues | 21 | 31% |

| 10 | Resource absences | 19 | 28% |

| 11 | Confusion on system measurement | 19 | 28% |

| 12 | Human error during software development | 18 | 27% |

| 13 | Non reliability | 17 | 25% |

These recognized security concerns were then mapped using the cyber security challenges model (CSCM), which will aid software suppliers’ organizations in developing software applications at four levels: awareness “A,” management “M,” security “S,” and eminence “E.” Table 3 shows the label “CCSC” for each recognized challenge.

| S.No | Level | Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | Eminence | Lack of privacy |

| Lack of quality, liability and reliability | ||

| 4 | Security | Unauthorized access issues |

| High expenses | ||

| Lack of quick response in emergency | ||

| Cyber security issues | ||

| 3 | Management | Management issues |

| Confusion on system measurement | ||

| Resource absences | ||

| 2 | Awareness | Lack of proper awareness |

| Lack of proper framework | ||

| Skillful staff absence | ||

| Human error during software development | ||

| 1 | Initial | -- |

We have supervisor support, SLR, and a questionnaire survey to help us categorize important security concerns. Following that, we performed two case studies in software supplier companies to evaluate our security model, CSCM, in a real-world setting.

We developed the CSCM to classify and rank the 13 identified cyber threats. The model is divided into four interconnected levels, which cover the major areas of cyber security risk faced by software vendors throughout the software development lifecycle: awareness (A), management (M), security (S), and reputation (E).

Awareness: Table 3 shows the 1st level of security model, that consist of significant problems “Lack of proper awareness”, “Lack of proper framework”, “Skillful staff absence”, and “Confusion on System measurement”. In our concept, awareness is computed as a benefit criterion depending on the type of criteria following a thorough conversation with computer professionals.

Management: this is the proposed designed model of second level, which contains the significant issues of “Management issues”, “Resource absences”, and “Human error during software development”. Management, according to IT professionals, is also a benefit criterion due to the above key issues.

Security: Security is the third level, which is highly significant due to the greatest crucial challenge of “Cyber Security issues”. Other important problems at this level are “Lack of Quick response in emergency,” “High expenses,” and “Malicious activities.” As all these difficulties are close to FPIS and far from FNIS, IT professionals label this level benefits criterion.

Eminence: This is the final level of the proposed established security model, that encompasses “Lack of privacy” and “Non reliability”. Considering the “Lack of privacy” and “Non reliability” aspects, the “eminence” criteria are computed as the cost criteria.

Fuzzy TOPSIS application technique

We categorized and ranked the recognized complex by security challenges by Fuzzy TOPSIS to reply RQ2 in cyber security. Many scholars employed the same process, for example, in an extended Pythagorean fuzzy environment, Chen (2021) implemented the fuzzy AHP technique for multiple evaluations with risk ranking.

As the same concern of ambiguity exists in our scenario, we used the same technique as described in ‘Empirical study’, following all of the procedures outlined above:

Step 1: We picked parameters (awareness “A,” management “M,” security “S,” and eminence "E") for the analysis of recognized security issues prioritizing and ranking.

Step 2: As considered in Eq. (1), the proposed method calculate the matrix based performance on various specialist decisions. Since each of the answers is first expressed in linguistic expressions, variables are allocated to every possibility; for instance, the scores of the language words “equal importance (EI)” and “extreme importance (EI)” are (1, 1, 1) and (9, 9, 9), respectively. Table 4 shows the concerning awareness about the performance matrix; the same performance matrix will be generated for management, security, and eminence in Tables 5, 6 and 7, respectively.

| A | Awareness | Management | Security | Eminence | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCSC1 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| CCSC2 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| CCSC3 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| CCSC4 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| CCSC5 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| CCSC6 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| CCSC7 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| CCSC8 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| CCSC9 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| CCSC10 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| CCSC11 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| CCSC12 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| CCSC13 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

Note:

CCSC, Critical cyber security challenge.

| M | Awareness | Management | Security | Eminence | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCSC1 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| CCSC2 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| CCSC3 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| CCSC4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| CCSC5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| CCSC6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| CCSC7 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| CCSC8 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| CCSC9 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| CCSC10 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| CCSC11 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| CCSC12 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| CCSC13 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| S | Awareness | Management | Security | Eminence | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCSC1 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| CCSC2 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| CCSC3 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| CCSC4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| CCSC5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| CCSC6 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| CCSC7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| CCSC8 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| CCSC9 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| CCSC10 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| CCSC11 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| CCSC12 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| CCSC13 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| E | Awareness | Management | Security | Eminence | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCSC1 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| CCSC2 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| CCSC3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| CCSC4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| CCSC5 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| CCSC6 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| CCSC7 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| CCSC8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| CCSC9 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| CCSC10 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| CCSC11 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| CCSC12 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| CCSC13 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

Step 3: Applying Eq. (3), the accumulated fuzzy weights of each criterion are determined, and the combined matrix of all the attributes/issues with those of criteria/levels is presented underneath in Table 8.

| Fuzzy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weights | AW | Normalized | |||

| Awareness | 0.485277 | 0.628999 | 0.811254 | 1.925529 | 0.626675 |

| Management | 0.166593 | 0.227599 | 0.30821 | 0.702402 | 0.228601 |

| Security | 0.077516 | 0.097743 | 0.125826 | 0.301085 | 0.09799 |

| Eminence | 0.035022 | 0.045659 | 0.062913 | 0.143594 | 0.046734 |

| Sum | 3.07261 | 1 | |||

Note:

AW, average weight.

Step 4: Applying Eqs. (5) and (6), described the combined decision matrix as shown in Table 9, and the normalized matrix from normalized fuzzy weight are shown in Table 10, as well as benefit in term of cost criterion. Because of the lack of confidentiality, trust, and quality attributes, the criterion of “eminence” is computed as the cost criterion, but the other criteria “awareness,” “management,” and “security” are chosen as benefits criteria. After applying the formula, we obtained the given outcomes.

| Awareness | Management | Security | Eminence | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weights | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.1 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.06 |

| Combined decision matrix | ||||||||||||

| Min | Mean | Max | Min | Mean | Max | Min | Mean | Max | Min | Mean | Max | |

| CCSC1 | 4 | 7.5 | 9 | 4 | 7.5 | 9 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 4 | 6 | 9 |

| CCSC2 | 6 | 7.5 | 9 | 2 | 4.5 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 2 | 5 | 8 |

| CCSC3 | 2 | 5 | 9 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 1 | 3.5 | 8 | 2 | 4.5 | 8 |

| CCSC4 | 1 | 4 | 9 | 1 | 6.5 | 9 | 1 | 5 | 9 | 2 | 5 | 8 |

| CCSC5 | 1 | 4 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 6.5 | 9 | 2 | 5 | 8 |

| CCSC6 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 8 | 4 | 6.5 | 9 | 2 | 5.5 | 8 |

| CCSC7 | 1 | 4.5 | 8 | 2 | 5 | 8 | 1 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 6 | 9 |

| CCSC8 | 1 | 4.5 | 8 | 1 | 4.5 | 8 | 4 | 7 | 9 | 1 | 4 | 6 |

| CCSC9 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 2 | 6 | 9 | 2 | 5.5 | 9 | 2 | 3.5 | 6 |

| CCSC10 | 1 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 6 | 9 | 1 | 3.5 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 9 |

| CCSC11 | 1 | 3 | 9 | 4 | 5.5 | 8 | 2 | 6 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| CCSC12 | 2 | 4.5 | 6 | 2 | 5.5 | 9 | 1 | 2.5 | 8 | 2 | 4 | 8 |

| CCSC13 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 2 | 5.5 | 9 | 1 | 5.5 | 9 | 1 | 5 | 9 |

| Awareness | Management | Security | Eminence | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weights | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.1 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.06 |

| Normalized fuzzy decision matrix | ||||||||||||

| Min | Mean | Max | Min | Mean | Max | Min | Mean | Max | Min | Mean | Max | |

| CCSC1 | 0.444 | 0.833 | 1 | 0.444 | 0.833 | 1 | 0.667 | 0.889 | 1 | 0.111 | 0.167 | 0.25 |

| CCSC2 | 0.667 | 0.833 | 1 | 0.222 | 0.5 | 0.667 | 0.444 | 0.667 | 0.889 | 0.125 | 0.2 | 0.5 |

| CCSC3 | 0.222 | 0.556 | 1 | 0.667 | 0.778 | 0.889 | 0.111 | 0.389 | 0.889 | 0.125 | 0.222 | 0.5 |

| CCSC4 | 0.111 | 0.444 | 1 | 0.111 | 0.722 | 1 | 0.111 | 0.556 | 1 | 0.125 | 0.2 | 0.5 |

| CCSC5 | 0.111 | 0.444 | 0.889 | 0.111 | 0.333 | 0.667 | 0.444 | 0.722 | 1 | 0.125 | 0.2 | 0.5 |

| CCSC6 | 0.111 | 0.333 | 0.667 | 0.111 | 0.333 | 0.889 | 0.444 | 0.722 | 1 | 0.125 | 0.182 | 0.5 |

| CCSC7 | 0.111 | 0.5 | 0.889 | 0.222 | 0.556 | 0.889 | 0.111 | 0.444 | 0.889 | 0.111 | 0.167 | 0.5 |

| CCSC8 | 0.111 | 0.5 | 0.889 | 0.111 | 0.5 | 0.889 | 0.444 | 0.778 | 1 | 0.167 | 0.25 | 1 |

| CCSC9 | 0.444 | 0.667 | 0.889 | 0.222 | 0.667 | 1 | 0.222 | 0.611 | 1 | 0.167 | 0.286 | 0.5 |

| CCSC10 | 0.111 | 0.444 | 0.889 | 0.222 | 0.667 | 1 | 0.111 | 0.389 | 0.667 | 0.111 | 0.2 | 1 |

| CCSC11 | 0.111 | 0.333 | 1 | 0.444 | 0.611 | 0.889 | 0.222 | 0.667 | 0.889 | 0.167 | 0.2 | 0.25 |

| CCSC12 | 0.222 | 0.5 | 0.667 | 0.222 | 0.611 | 1 | 0.111 | 0.278 | 0.889 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| CCSC13 | 0.444 | 0.667 | 0.889 | 0.222 | 0.611 | 1 | 0.111 | 0.611 | 1 | 0.111 | 0.2 | 1 |

Step 5: The weighted normalized fuzzy matrix is created in this step by multiplying the weight of each criterion by the weight of each alternative. Table 11 shows the resulting weighted normalized decision matrix as obtained by applying Eq. (7).

| Awareness | Management | Security | Eminence | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weights | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.1 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.06 |

| Weighted normalized fuzzy decision matrix | ||||||||||||

| Min | Mean | Max | Min | Mean | Max | Min | Mean | Max | Min | Mean | Max | |

| CCSC1 | 0.222 | 0.500 | 0.800 | 0.089 | 0.167 | 0.3 | 0.047 | 0.08 | 0.1 | 0.003 | 0.007 | 0.015 |

| CCSC2 | 0.333 | 0.500 | 0.800 | 0.044 | 0.100 | 0.2 | 0.031 | 0.06 | 0.089 | 0.004 | 0.008 | 0.03 |

| CCSC3 | 0.111 | 0.333 | 0.800 | 0.133 | 0.156 | 0.267 | 0.008 | 0.035 | 0.089 | 0.004 | 0.009 | 0.03 |

| CCSC4 | 0.056 | 0.267 | 0.800 | 0.022 | 0.144 | 0.300 | 0.008 | 0.05 | 0.100 | 0.004 | 0.008 | 0.03 |

| CCSC5 | 0.056 | 0.267 | 0.711 | 0.022 | 0.067 | 0.2 | 0.031 | 0.065 | 0.1 | 0.004 | 0.008 | 0.03 |

| CCSC6 | 0.056 | 0.200 | 0.533 | 0.022 | 0.067 | 0.267 | 0.031 | 0.065 | 0.1 | 0.004 | 0.007 | 0.03 |

| CCSC7 | 0.056 | 0.300 | 0.711 | 0.044 | 0.111 | 0.267 | 0.008 | 0.04 | 0.089 | 0.003 | 0.007 | 0.03 |

| CCSC8 | 0.056 | 0.300 | 0.711 | 0.022 | 0.100 | 0.267 | 0.031 | 0.07 | 0.100 | 0.005 | 0.01 | 0.06 |

| CCSC9 | 0.222 | 0.400 | 0.711 | 0.044 | 0.133 | 0.300 | 0.016 | 0.055 | 0.1 | 0.005 | 0.011 | 0.03 |

| CCSC10 | 0.056 | 0.267 | 0.711 | 0.044 | 0.133 | 0.3 | 0.008 | 0.035 | 0.067 | 0.003 | 0.008 | 0.06 |

| CCSC11 | 0.056 | 0.200 | 0.800 | 0.089 | 0.122 | 0.267 | 0.016 | 0.06 | 0.089 | 0.005 | 0.008 | 0.015 |

| CCSC12 | 0.111 | 0.300 | 0.533 | 0.044 | 0.122 | 0.3 | 0.008 | 0.025 | 0.089 | 0.004 | 0.010 | 0.03 |

| CCSC13 | 0.222 | 0.400 | 0.711 | 0.044 | 0.122 | 0.300 | 0.008 | 0.055 | 0.1 | 0.003 | 0.008 | 0.06 |

Step 6: To compute FPIS and FNIS (Iqbal et al., 2024; Mete et al., 2019), the chosen cost criterion is “eminence,” and the remaining benefit criteria are “awareness,” “management,” and “security.” Following a thorough deliberation with research professionals, these criteria are chosen based on their nature. The criterion with the longest distance from FNIS and the smallest distance from FPIS is the best of all. Equations (8) and (9) are used to determine the values, which are displayed in Table 12.

| A* | 0.333 | 0.500 | 0.800 | 0.133 | 0.167 | 0.3 | 0.047 | 0.08 | 0.1 | 0.005 | 0.011 | 0.06 |

| A− | 0.056 | 0.200 | 0.533 | 0.022 | 0.067 | 0.2 | 0.008 | 0.025 | 0.067 | 0.003 | 0.007 | 0.015 |

Step 7: Utilizing Eqs. (10) and (11), we measured the distance between all alternatives and FPIS and FNIS. We evaluated each alternative distance from FPIS and FNIS utilizing the same process and formulas and then derived d* and d− by summing all the alternatives concerning each criterion, as shown in Tables 13 and 14.

| Distance from FPIS | di* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCSC1 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.12 |

| CCSC2 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.12 |

| CCSC3 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.23 |

| CCSC4 | 0.21 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.32 |

| CCSC5 | 0.22 | 0.10 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.35 |

| CCSC6 | 0.28 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.40 |

| CCSC7 | 0.20 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.32 |

| CCSC8 | 0.20 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.29 |

| CCSC9 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.20 |

| CCSC10 | 0.22 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.31 |

| CCSC11 | 0.24 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.33 |

| CCSC12 | 0.23 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.35 |

| CCSC13 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.19 |

| Distance from FNIS | di− | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCSC1 | 0.25 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.38 |

| CCSC2 | 0.28 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.34 |

| CCSC3 | 0.18 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.29 |

| CCSC4 | 0.16 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.27 |

| CCSC5 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.15 |

| CCSC6 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.08 |

| CCSC7 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.19 |

| CCSC8 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.22 |

| CCSC9 | 0.18 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.29 |

| CCSC10 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.21 |

| CCSC11 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.24 |

| CCSC12 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.16 |

| CCSC13 | 0.18 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.30 |

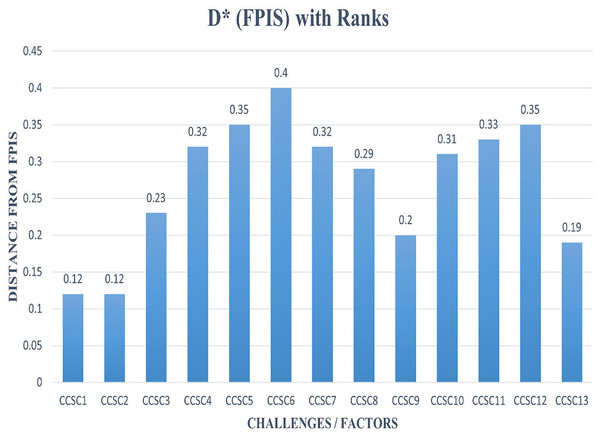

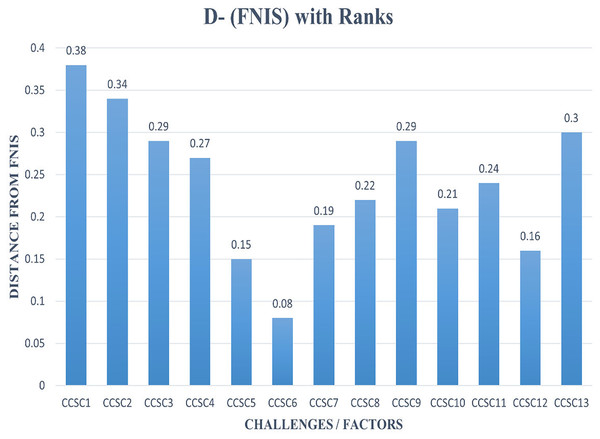

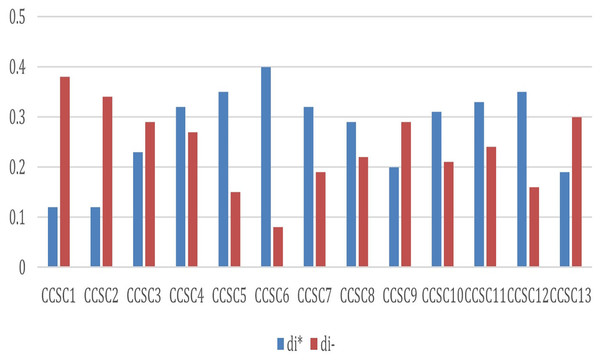

According to Figs. 5 and 6, the distance of FPIS in respect of CCSC1 is “0.12”, and has the highest distance from FNIS, which is “0.38.” As shown in Fig. 7, the values demonstrate that CCSC1 is the best alternative/challenge among all the other issues of cyber security challenges.

Figure 5: Graphical representation of the distance from FPIS with ranks.

Figure 6: Graphical representation of the distance from FNIS with ranks.

Figure 7: Graphical representation of cyber security challenges from FPIS and FNIS.

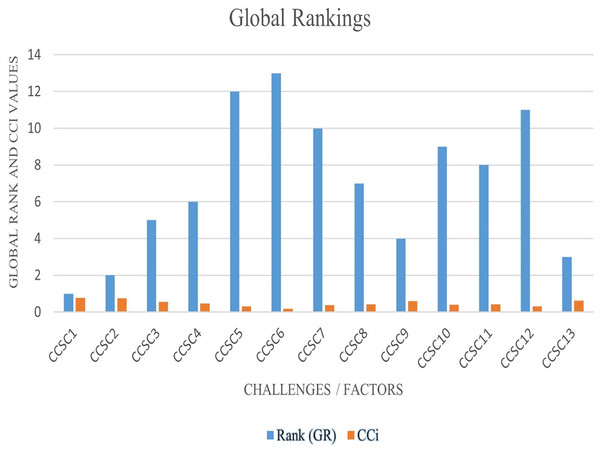

Step 8: Using Eq. (12), we calculated the closeness of coefficient index values (CCi) for each possibility. Table 15 illustrates the ultimate estimated CCi results for all 13 significant security problems.

| CCSC# | Challenges | CCi | Rank (GR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCSC1 | Cyber security issues | 0.768 | 1 |

| CCSC2 | Lack of proper awareness | 0.740 | 2 |

| CCSC3 | Lack of proper framework | 0.553 | 5 |

| CCSC4 | Skillful staff absence | 0.461 | 6 |

| CCSC5 | Lack of quick response in emergency | 0.302 | 12 |

| CCSC6 | High expenses | 0.167 | 13 |

| CCSC7 | Lack of privacy | 0.374 | 10 |

| CCSC8 | Management issues | 0.431 | 7 |

| CCSC9 | Unauthorized access issues | 0.596 | 4 |

| CCSC10 | Resource absences | 0.405 | 9 |

| CCSC11 | Confusion on system measurement | 0.427 | 8 |

| CCSC12 | Human error during software development | 0.310 | 11 |

| CCSC13 | Non reliability | 0.617 | 3 |

Note:

CCi, Closeness coefficient index; GR, global ranking.

According to Fig. 8, the security challenge “security issues/access of cyber-attacks (CCSC1)” is the best-ranked critical cyber security challenge with a consistency coefficient value of 0.768, as supplier companies have protection, privacy, and confidentiality issues for essential user information during software development. As a result, software providers’ enterprises must prioritize “Cyber Security issues” throughout software development.

Figure 8: Graphical representation of the global ranks (GR) of cyber security challenges.

Discussion and summary

In light of the recognized SLR security issues, we established the CSCM model for supplier companies in the context of cyber security challenges. The CSCM model’s primary criteria/levels are “awareness,” “management,” “security,” and “eminence”. The modeling and assessment of security challenges have been further validated by the software industry specialists using a questionnaire survey. Furthermore, a Fuzzy-TOPSIS approach is used to prioritize the identified cybersecurity challenges.

Identification of security challenges

Following a thorough examination and evaluation of the research studies, 13 significant security issues that can positively affect software vendor organizations were recognized, as indicated in Table 15. To better understand this, we examined the distribution of these problems across the different levels of the CSCM model, which allowed suppliers to focus their efforts on the relevant layers of the organization (e.g., policy vs implementation). In addition, several barriers, such as the “Lack of proper awareness” or “Malicious activities” are in line with the larger patterns highlighted in recent publications on threat intelligence, which highlight the relevance and application of our findings.

Validation of security challenges

We used the methodology of a questionnaire survey to validate the identified security challenges from software industry professionals. The findings demonstrate how the recognized cyber security issues have a favorable influence on vendor companies during software development, based on comments from 35 IT specialists.

The validation process has shown a consistent scientific consensus on the critical importance of several key issues, in particular those related to the design of secure architecture and the preparation of response to incidents. This not only reinforces the reliability of our findings but also shows how closely the experience in the field fits the literature’s concerns. This association gives confidence in the universality and relevance of the problems identified.

Prioritization of security challenges

In decision-making criteria, ambiguity and confusion play an essential role. To prioritize cyber security concerns, we observed the entire guidelines of the fuzzy TOPSIS technique. The CCi values are used to categorize the cyber security challenges that have been recognized. This technique thoroughly ranks all possibilities, which will assist IT experts in reconsidering their policies and guidelines for cyber security protection. The topmost rated cyber security issues that should affect software provider companies during software development are CCSC1 “Cyber Security issues,” CCSC2 “Lack of proper awareness”, and CCSC13 “Lack of Quality, Liability and Reliability”.

Priority findings have important implications for practice. The cybersecurity spectrum in the creation of cutting-edge technologies has also been the subject of recent studies. For instance, Khan et al. (2024) looked at how supply chain elements enabled by AI are growing more susceptible to cyberattacks, where AI-enabled SBOMs offer both potential advantages and disadvantages. The study’s findings support the CSCM model’s emphasis on multi-criteria ranking of critical issues and lay the groundwork for future research into vendor organization supply chain dependencies. They did this by using a Fuzzy-TOPSIS approach to provide a structured risk prioritization of vulnerabilities in new software bills of materials (SBOMs) (Radanliev, Santos & Brandon-Jones, 2024). Similar to this, Khan et al. (2022a) looked into AI security and cyber risk in IoT systems, pointing out new vulnerabilities that arise when AI-driven automation and networked IoT environments come together (Radanliev et al., 2024). Our top priorities of “Cyber Security issues” and “Lack of proper awareness” are in line with the threats that have been identified, such as exposure to advanced persistent threats and insufficient security frameworks. Matching our findings with these modern viewpoints implies that the CSCM model can be used in broader contexts where AI and IoT are essential components of intricate software supply chains, in addition to traditional software vendor contexts.

Our results also support a number of long-standing concerns in cybersecurity research when compared to more extensive earlier work. We identified “Lack of proper awareness” as a top-ranked issue, which is consistent with studies like Öğütçü, Testik & Chouseinoglou (2016) and Akter et al. (2022) and that highlight the importance of “cybersecurity awareness” and human factors in risk mitigation. Likewise, previous systematic reviews (e.g., Uchendu et al., 2021) echoed our findings on “Cyber Security issues” and “Lack of Quality, Liability, and Reliability” by highlighting persistent vulnerabilities resulting from inadequate security practices in vendor organizations. But by placing these insights within a structured, multi-criteria decision-making process that has been verified by professionals in the field, the CSCM model goes beyond a simple list of problems and offers a framework for setting priorities for real-world action. This comparative positioning shows that although our findings are consistent with previous research, they add to the body of knowledge by providing a practical, vendor-specific model for tackling cybersecurity issues in software development.

The highest-rated issue, “Cyber Security issues, for example, stresses the critical need for robust authentication mechanisms, threat detection systems, and regular penetration testing throughout the life of the software”. Similarly, the shortage of good knowledge highlights the critical need for continued cyber-training programs and knowledge-sharing frameworks in software development teams. Finally, the “lack of quality, liability and reliability” highlights concern about the quality of secure code and highlights the importance of incorporating the principles of the secure development lifecycle (SDLC) into vendor processes. Combined, the prioritized list provides actionable knowledge for software vendors and can be used to build cyber maturity models, conduct internal risk assessments, or guide investments in secure development resources.

Conclusion

This study developed and tested the cyber security challenge model (CSCM) for software vendor companies, which addresses crucial data privacy and security concerns across the software development lifecycle. A thorough literature analysis and expert validation identified 13 significant cybersecurity difficulties, with the top three being “Cyber Security issues,” “Lack of proper awareness,” and “Lack of quality, liability, and reliability.” These concerns were prioritized using the Fuzzy-TOPSIS approach, which provides a systematic and evidence-based framework for vendor organizations. These security challenges were further classified into four levels/categories of the CSCM model and evaluated by IT specialists using a questionnaire survey. The findings underscore that, in addition to technological weaknesses, organizational and psychological elements are equally important for cybersecurity resilience.

Our study results also present a classification of security issues based on prioritizing, which will help software provider companies evaluate cyber security challenges for secure software development. Furthermore, we want to use the fuzzy-TOPSIS approach on the CSCM practices obtained using SLR in the future.

Future studies could explore the use of dynamic ranking approaches or threat score systems based on machine learning in combination with expert advice to improve prioritization. Moreover, industry-wide benchmarking could help confirm the applicability of the CSCM model in other areas.

Supplemental Information

Code of Fuzzy.

Computational dataset and step-by-step application of the Fuzzy-TOPSIS technique used to evaluate and rank 13 critical cybersecurity challenges identified in the Cybersecurity Challenges Model (CSCM) for software vendor organizations, including normalized decision matrices, weight assignments, and final closeness coefficient values.