Optimizing lexical fitness assessment in L2 Chinese reading texts

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Sebastian Ventura

- Subject Areas

- Computational Linguistics, Computer Education, Data Mining and Machine Learning, Data Science

- Keywords

- L2 Chinese, Lexical fitness, Lexical feature engineering, Text classification, Classification model

- Copyright

- © 2025 Lin and Liu

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2025. Optimizing lexical fitness assessment in L2 Chinese reading texts. PeerJ Computer Science 11:e3336 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3336

Abstract

Background

Vocabulary serves as the foundation for text comprehension. Therefore, texts at different proficiency levels should incorporate appropriately adapted vocabulary to support second language learners in developing their reading skills.

Methods

To objectively quantify the grading process of L2 Chinese (Chinese for a Second Language) reading texts, we designed a text classification experiment grounded in lexical fitness evaluation. This study employs a comparative framework, pitting a classical machine learning classification model against a neural network-based classification model incorporating a multi-head attention mechanism. The experimental results demonstrate that the rule-based lexical feature extraction method achieves optimal performance under the random forest (RF) classification model, attaining an F1-score of 0.879. To further optimize and streamline the classification process, we identified 22 optimal feature sets based on mutual information (MI) rankings of lexical features, incorporating novel features introduced in this study.

Results

A comparative analysis with prior work underscores the superiority of our lexical feature construction framework. Crucially, the assessment of lexical form, lexical meaning, and lexical syntax, as well as their interactions across different textual levels, exhibits significant variability. Optimal evaluation can only be achieved through a holistic integration of all three dimensions.

Introduction

A fundamental objective in second language (L2) pedagogy is to provide learners with reading materials that approximate the linguistic complexity of texts designed for native speakers. This alignment is critical for both instructional and assessment purposes, enabling objective and scientifically valid evaluations of learners’ language proficiency, particularly in reading comprehension. As the primary carrier of semantic meaning (Cruse, 1986), vocabulary serves as the foundational unit of textual understanding. Decoding words constitutes the initial stage of sentence and discourse processing, making lexical acquisition the most significant hurdle in L2 reading comprehension (Laufer, 1989; Mehrpour & Rahimi, 2010; Laufer & Aviad-Levitzky, 2017; Dong et al., 2020). The construct of “lexical fitness” operationalizes the alignment between textual vocabulary characteristics and reading proficiency levels, where increased lexical fitness denotes optimal linguistic scaffolding for L2 comprehension. This metric quantifies the degree to which lexical selection in instructional texts facilitates rather than impedes second language acquisition processes.

Vocabulary constitutes a multidimensional and complex linguistic system (I. S. P. Nation, 2001). A substantial body of research has investigated the relationship between lexical characteristics and L2 reading text difficulty (Read & Read, 2000; Hu & Nation, 2000; Crossley, Salsbury & McNamara, 2010; Biber, 2016). These studies demonstrate that variations in lexical dimensions—and their multidimensional interactions—systematically predict text difficulty levels. Methodologically, prior work has primarily adopted text classification approaches, establishing mapping correlations between lexical features and text-level categories through observational studies, regression analyses, and related statistical techniques. On the one hand, they have not systematically considered and labeled lexical features, exploring one or a few types of lexical features in isolation in relation to the reading text level, such as lexical morphological features (Schmitt & Zimmerman, 2002), lexical diversity (Koizumi & In’nami, 2012), word frequency (Solomon & Howes, 1951), lexical semantic features (Brysbaert, Warriner & Kuperman, 2014), lexical articulation features (Meyer, 2003; Crossley, Greenfield & McNamara, 2008). On the other hand, most of the text classification methods in the research are subjective, and the classification results are not convincing.

Recent developments in machine learning and deep learning technologies have significantly enhanced the potential for improving both the accuracy and objectivity of text classification systems. These technological advancements present valuable opportunities for the field of L2 pedagogy to refine existing methodologies for teaching and assessing reading proficiency. Currently, the application of machine learning and deep learning-based text classification models in L2 research has been proliferating (Lim, Song & Park, 2023; Uzun, 2020). For instance, Pilán, Volodina & Johansson (2013) proposed a rule-based machine learning approach for classification tasks. Their study utilized a support vector machine (SVM) model to assess sentence suitability for B1-level language learners, facilitating the automatic filtering of L1 corpora for L2 learning applications. This method has been successfully integrated into the ICALL platform. Lee, Jang & Lee (2021) demonstrated that incorporating manual features enhances readability evaluation performance on small datasets when used with a random forest (RF) classification model. Martinc, Pollak & Robnik-Šikonja (2021) employed neural network-based approaches to improve the accuracy and robustness of readability assessment, with empirically validated performance across multilingual and cross-domain datasets. However, few studies have explored the application of machine learning and neural network methods to text classification tasks in the domain of Chinese as a second language (CSL or L2 Chinese).

In conclusion, the purpose and significance of our study are as follows:

-

(i)

Vocabulary serves as the foundation of reading comprehension. A scientifically-grounded evaluation of lexical fitness in L2 Chinese reading materials can significantly enhance learners’ reading comprehension outcomes.

-

(ii)

Adopting a hierarchical “morpheme-word-sentence-chapter framework and grounded in the tripartite lexical dimensions of form, meaning, and syntax, this study systematically develops a comprehensive feature engineering system for lexical fitness.

-

(iii)

This study establishes a L2 Chinese reading corpus and develops an optimal lexical fitness evaluation framework through two key research components: (1) comparative analysis of text classification models, and (2) systematic extraction and selection of lexical features.

-

(iv)

We apply machine learning and neural network approaches to L2 Chinese text classification, with the ultimate goal of enhancing L2 Chinese reading pedagogy and assessment.

Lexical fitness and text classification models

Lexical fitness, as defined in this framework, represents the statistically correlation between quantifiable lexical features and text difficulty levels. This metric provides a vocabulary-centered approach to assessing the alignment between reading materials and L2 learners’ proficiency levels. Guided by the syntactic hierarchy spanning morpheme-word, word-word, word-sentence, and word-chapter relationships, we systematically extracted 73 lexical fitness features across three linguistic dimensions: (1) form, (2) meaning, and (3) syntax. These features constitute our comprehensive feature engineering framework for evaluating lexical fitness in L2 Chinese texts.

The theoretical foundation for constructing the lexical fitness rests on the follow principles:

-

(i)

The language proficiency of a learner constitutes a multifaceted construct encompassing the integrated mastery of morphological, semantic, and grammatical systems (Bachman, 1990).

-

(ii)

The importance of vocabulary is realized within specific linguistic contexts (Halliday & Hasan, 2014), which emerge through the hierarchical syntactic structure of morphemes forming words, words constructing sentences, and sentences building chapters. Consequently, investigations into lexical fitness must employ a multi-dimensional framework to examine the dynamic relationships between vocabulary and morphemes, lexical items and their co-text, as well as words and their broader sentential or textual environments.

-

(iii)

In the fields of automated essay scoring and textbook compilation, advanced natural language processing (NLP) techniques and statistical methods are employed to analyze text comprehensively across lexical, semantic, and syntactic levels (Attali & Burstein, 2006; Li et al., 2014; Lim, Song & Park, 2023).

-

(iv)

Certain lexical features can help explain proficiency differences across levels of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) (Treffers-Daller, Parslow & Williams, 2018).

Common machine learning classification models include support vector machines (SVM), naïve Bayes (NB), k-nearest neighbors (KNN), and random forests (RF), etc. The SVM algorithm identifies an optimal hyperplane that maximizes inter-class separation (using a linear kernel) or addresses nonlinear classification by projecting data into higher-dimensional space via kernel functions (e.g., radial basis function (RBF)). In text classification tasks, lexical features are first converted to vector representations. The SVM then determines support vectors through optimization techniques like gradient descent, maximizing the margin between text vectors of distinct classes to achieve optimal classification performance. The RF algorithm operates as an ensemble of multiple decision trees, where each tree independently performs classification by randomly selecting a subset of lexical features for node splitting. During prediction, the model aggregates outputs from all trees through majority voting for discrete classification or averaging for continuous regression, thereby enhancing generalization through collective decision-making. The architecture flows as follows:

-

Input data

Convert lexical features into numerical vectors. In our study, lexical features were systematically extracted and quantitatively represented as numerical feature vectors.

-

Construction of single tree decision tree

The RF construction begins with bootstrap sampling, where multiple subsets are randomly drawn with replacement from the training data. For each decision tree, node splitting proceeds by first randomly selecting m candidate features from the available feature space. The optimal split point is then determined by maximizing information gain (or minimizing Gini impurity) across these candidate features. For instance, when the feature “apple” is selected for splitting, the decision rule might be formulated as: if apple count ≥1 then classify as fruit; otherwise classify as car. This splitting process recursively continues until either the predefined maximum tree depth is attained or the number of samples in a node falls below the minimum threshold for further division.

-

Forest construction and prediction

The algorithm constructs N independent decision trees through the aforementioned process. During prediction, each tree casts a vote for its predicted class, with the final classification determined by majority voting across all ensemble members.

Given the extensive application of various machine learning classification models in this study, we focus our discussion on their implementation rather than architectural details. For comprehensive theoretical treatments of these models, readers may refer to established works such as Ayodele (2010) and Singh, Thakur & Sharma (2016). Next, we will introduce the neural network architectures employing multi-head attention (MHA) mechanisms for classification tasks.

The MHA enhances the traditional self-attention mechanism by computing multiple attention heads in parallel, enabling the model to capture diverse dependencies within the input sequence (Devlin et al., 2019).

Split Q K V into h heads, each with dimension dk = d/h:

Attention is calculated independently for each head: The outputs of all heads are spliced and fused through the linear layer WO:

(1) The MHA enables the model to simultaneously capture diverse semantic features—such as syntax, denotation, and sentiment—across different positions. It efficiently computes association weights at multiple levels (word-to-word, word-to-sentence, and word-to-chapter) in parallel, eliminating the need for sequential processing. Below we present our text classification framework leveraging this MHA architecture:

Input Text Embedding Layer MHA Layer Pooling (e.g., [CLS] tags) Fully Connected Classification Layer.

-

Input Text

Following word segmentation, we prepend a [CLS] classification tag and append [SEP] separation tags to the text. The segmented tokens are then mapped to their corresponding integer IDs from the vocabulary (e.g., [101, 102, 103, 104, 105]), producing an ordered integer sequence that preserves word order information to compensate for the self-attention mechanism’s lack of inherent positional awareness.

-

Embedding Layer

After tokenization, initial word representations are generated through either word-level embeddings (e.g., Word2Vec) or subword embeddings (e.g., WordPiece in Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT)). At the input layer, we incorporate morphological features by concatenating subword vectors (e.g., from FastText) to establish word-morpheme associations. For contextual representation, BERT performs dynamic word embedding, enabling effective modeling of polysemy and syntactic roles through its positional encoding and self-attention mechanisms. Positional vectors (sinusoidal/learnable) encode word order, distinguish cross-sentence semantics, and capture sentence-level grammar. Special tokens ([CLS], [SEP]) enable sentence information aggregation. Through embedding pooling and transformer processing, we hierarchically integrate features from words to chapters. The embedding layer combines subword decomposition, dynamic encoding, positional information, and hierarchical aggregation to represent all linguistic elements in a unified vector space.

-

MHA Layer

Different attention heads (AHs) specialize in distinct linguistic patterns: some capture local syntactic relations, others model long-range semantic dependencies, while certain heads focus on discourse-level structures. Through dynamic attention weight computation (Query-Key matching), the mechanism explicitly models interactions across all linguistic levels—from morphemes to document structure—enabling adaptive fusion of multiscale features (morpheme-, word-, sentence-, and document-level) and automatic hierarchical feature aggregation. For long-text categorization, we employ a multi-layer transformer architecture where lower layers primarily model word-level interactions while higher layers capture sentence-level relationships. Each word in the input sequence computes association scores with all other words through the attention mechanism’s Query (Q), Key (K), and Value (V) operations: (2) Finally, the outputs from all AHs are concatenated and linearly transformed through the weight matrix WO (as specified in Eq. (1)) to produce the final combined representation.

-

Pooling

We utilize [CLS] token pooling to consolidate the entire input sequence’s relational information into a single [CLS] vector via the transformer’s global attention mechanism. At the morphological level, the [CLS] token aggregates subword interactions to resolve constructions and polysemy. For document-level representation, we either perform secondary pooling of segmented [CLS] vectors or employ a Hierarchical transformer, where the [CLS] token captures each word’s thematic contribution to the overall document.

-

Fully Connected Classification Layer

The fully connected classification layer (FCCL) serves as the model’s final decision layer, transforming the high-level features from preceding layers (embedding, self-attention, and pooling) into class predictions. This layer applies a linear transformation using a weight matrix and bias vector , where d represents the input dimension and k denotes the number of categories. The output is normalized into a probability distribution through a Softmax function, completing the classification process. (3)

Experimental process

We designed a lexical fitness evaluation experiment in which we first created a corpus by machine scanning reading text, then performed rule-based feature extraction and compared it to term frequency-inverse document frequency’s (TF-IDF’s) feature extraction method. Then, we perform a comprehensive comparison between conventional machine learning classifiers and neural network models incorporating MHA architecture, subsequently deploying the highest-performing model for automated lexical fitness assessment.

Corpus construction

Center for Language Education and Cooperation (CLEC) developed the HSK (Hànyǔ Shuǐpíng Kǎoshì), a standardized test designed to assess the proficiency of non-native Chinese speakers. Over time, the HSK has become a crucial gateway for foreign students to study in China, a requirement for scholarship applications, and an important instrument for assessing instruction in schools. In an increasing number of countries, government agencies and multinational corporations rely on the HSK as a key determinant in hiring decisions, salary adjustments, and employee promotions. The six levels of the HSK exam offer a comprehensive assessment of language competence, catering to learners ranging from novice to expert. Among these, the reading comprehension section spans all levels and primarily evaluates students’ reading skill.

To construct the dataset, we compiled a total of 1,332 HSK reading texts, including those from the HSK Standard Tutorial Levels 1–6, compiled with permission from CLEC/Confucius Institute Headquarters, as well as texts from the New HSK Levels 1-6, also provided by CLEC/Confucius Institute Headquarters (Table 1). The example sections of the reading texts, along with the corresponding responses, were excluded, and the word choice and sentence ordering tasks were manually processed. Sentences were ordered with commas for clauses and periods for endings. To facilitate processing by computational software, the cleaned texts were divided, saved as some txt files, and each entry was assigned a unique identifier. For the subsequent analyses, the dataset was randomly split into training and test set in a 7:3 ratio. The training set was used to train the model, while the test set served to evaluate the accuracy and performance of the classification model.

| Text level | New HSK’reading texts | HSK standard Tutorial’reading texts | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total texts | Total words | Total clauses | Total sentences | Total texts | Total words | Total clauses | Total sentences | |

| HSK1 | 44 | 1,062 | 261 | 233 | 42 | 706 | 111 | 150 |

| HSK2 | 103 | 3,882 | 933 | 649 | 60 | 1,667 | 393 | 299 |

| HSK3 | 151 | 7,963 | 1,637 | 1,377 | 80 | 4,260 | 654 | 587 |

| HSK4 | 222 | 14,514 | 2,725 | 2,315 | 50 | 4,730 | 667 | 616 |

| HSK5 | 206 | 30,120 | 4,901 | 4,116 | 35 | 12,552 | 1,808 | 1,559 |

| HSK6 | 304 | 45,083 | 7,290 | 5,955 | 35 | 17,474 | 2,586 | 2,229 |

Rule-based lexical features extraction

As previously discussed, lexical fitness is closely associated with lexical features. Therefore, in the rule-based lexical feature extraction process, we aim to extract features as exhaustively as possible. Consequently, 73 comprehensive and systematically defined lexical features were constructed, encompassing three dimensions: lexical form, lexical meaning, and lexical syntax. Table 2 presents the three primary features and twelve supplementary features that we developed, totaling 73 lexical fitness features, which encompass all vocabulary levels and provide a more comprehensive evaluation of the lexical fitness of the reading texts. Among these, a period, an exclamation point, and a question mark finish the sentence, while a comma, a stop number, and a semicolon finish the clause. Uber Type-Token Ratio (UTTR) and Type-Token Ratio (TTR) are measurement tools used to assess lexical diversity, which refers to the richness of vocabulary employed by language users. This includes the use of a variety of different words, such as synonyms, superlatives, and other related terms, while minimizing repetition of specific words (Jarvis, 2002).

| Primary features | Supplementary features | 73 Lexical fitness features |

|---|---|---|

| Lexical form | morpheme-word (5) | Average number of strokes for single-letter words; Average number of strokes in two-letter words; Average number of strokes for three-letter words; Average number of strokes in four-letter words; Average number of strokes in vocabulary (total number of strokes/total number of words) |

| word-word (4) | Proportion of single-letter words; Proportion of two-letter words; Proportion of three-letter words; Proportion of four-letter words | |

| word-sentence (2) | Average number of words in a clause; Average number of words in a sentence (additional) | |

| word-chapter (3) | UTTR((logTokens)2/(logTokens-logTypes)); TTR (Types/Tokens); Total number of words in chapter | |

| Lexical meaning | morpheme-word (1) | Semantic transparency |

| word-word (9) | Synonym rate; Homophone-homograph rate; Polysemy rate; Commonly used words rate; Written words rate; Idioms rate; New Chinese Proficiency Test Outline (the Outline): Levels 1~2 (elementary words), 3~4 (intermediate words), 5~6 (advanced words) | |

| word-sentence (1) | Lexical meaning contribution (additional) | |

| word-chapter (1) | Common use of subject words rate (additional) | |

| Lexical syntax | morpheme-word (3) | Simple word rate; Derivative word rate; Compound word rate (additional) |

| word-word (16) | Nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, pronouns, number words, and measure words rates (content words rate); Prepositions, conjunctions, and auxiliaries rates (function words rate); The Chinese Proficiency Vocabulary and Chinese Character Leveling Outline: A-words rate; B-words rate; C-words rate; D-words rate | |

| word-sentence (1) | Average number of semantic roles | |

| word-chapter (27) | Discourse articulators (containing 27 quantitative features) (additional) |

Note:

There is debate about the categorization of some features, such as A-words rate. Although A-words rate into any of the three first-level features is unsuitable, the correctness of the experimental outcomes has nothing to do with the categorization issue.

Semantic transparency in Chinese refers to the extent to which the overall meaning of synthetic words and phrases can be inferred from the meanings of their constituent morphemes (Gao, 2015). A word is considered to have high semantic transparency if its morphemic meaning facilitates the understanding of its overall meaning. Conversely, a word exhibits low semantic transparency if its meaning cannot be easily deduced from its constituent morphemes. To measure semantic transparency, we utilize a pre-trained Word2Vec model, which converts both words and their constituent morphemes into vectors. The cosine similarity between the vectors of the morphemes and the corresponding word is then calculated to assess the degree of semantic transparency. Lexical confusion within the reading texts is evaluated through the presence of synonyms, homophone-homograph, and polysemous words. The Modern Chinese Dictionary (7th edition) is consulted to identify polysemous words, which are defined as words with more than three meanings. The proportion of polysemous words is calculated based on their occurrence in the texts. The top 3,000 words from the Modern Chinese Corpus’ word frequency list are considered high-frequency words, and the percentage of such words in each reading text is computed. Ha, Nguyen & Stoeckel (2024) defined the rate of commonly used words, and this measure is applied to gauge the prominence of high-frequency vocabulary within the reading materials. The seriousness or complexity of the reading texts is assessed through the inclusion of written words and idiomatic expressions. To determine the proportion of written words, we refer to Expressions of Written Chinese by Chinese scholar Shengli (2006). Since true mastery of vocabulary—encompassing its meaning, usage, and its relationships with other words—is crucial for comprehension and application, vocabulary in the New Chinese Proficiency Test Outline (the Outline) is categorized within the lexical meaning dimension. Different words contribute to the overall meaning of a sentence to varying degrees. Certain words, such as content words (e.g., nouns and verbs), often carry a greater share of the semantic load and are essential for conveying the core meaning of the sentence. In contrast, other words, such as adverbs, adjectives, conjunctions, and function words, typically serve to modify, connect, or complement the main meaning, but their contribution to the overall semantic structure is comparatively smaller. By quantifying lexical contribution, it becomes possible to identify which words are central to the sentence’s meaning and which serve a supplementary or relational function. To compute the contribution of lexical meaning, the Word2Vec model initially transforms all words in a sentence into vector representations. These sentence vectors are then processed using the BERT deep learning model. Subsequently, the cosine similarity between the two types of vectors is calculated and averaged. Finally, to assess the commonness of subject words, the top three topic words for each reading text are determined using TF-IDF. These subject words are then compared to the top 1,000 most common words, and the ratio of commonality is calculated.

Vocabulary in Chinese can be categorized into simple, derived, and compound words based on the structure of morphemes that form the words. Simple words consist of morphemes that do not carry independent meanings. Derived words are typically classified into prefix words (e.g., lăo xiăo ā) and suffix words (e.g., zi er xìng). Chinese affixes are non-word elements that have fixed positions within words, such as the xìng a noun labeling similar to the English suffixes like “-ion” or “-ment” Compound words, on the other hand, are made up of multiple morphemes that carry meaning. These compound words are further divided into categories such as “joint-type,” “modifying-type,” and “subject-verb” combinations. They are generally considered more complex than simple words and derived words (Wang & Yuan, 2018). A higher frequency of content words (those with actual meaning) typically corresponds to a greater number of concepts, which can increase the complexity and reduce the comprehensibility of the text (Sung et al., 2015b). Although function words may lack independent meaning, they play an essential role in maintaining the coherence and structure of the reading text. Consequently, the rates of function words and content words are reported as a single attribute to assess the lexical fitness. The Chinese Proficiency Vocabulary and Chinese Character Leveling Outline, which classifies vocabulary based on frequency, with expert manual intervention as a supplement, forms the basis for determining the A-, B-, C-, and D- words rates. This classification system is grounded in a robust scientific framework and is often employed to evaluate “lexical complexity” in Chinese text assessments (Wu, 2016). Therefore, we include A-, B-, C-, and D- words rates into the category of the lexical syntax of the text’lexical fitness. In addition to the vocabulary-based measures, the study incorporates the average number of semantic roles assigned to words within a sentence. This metric helps assess the influence of grammatical meaning on syntactic complexity (Du, Wang & Wang, 2022). To achieve this, BERT is used to perform semantic role labeling (SRL) in Chinese texts. Furthermore, discourse articulators—words that link, direct, and organize discourse—play a crucial role in maintaining the logical flow between sentences and paragraphs, contributing to the cohesion and comprehensibility of the text. To avoid any misunderstanding, it is necessary to explain the terms “central_sent_num” and “central_sent_ratio”: the sum of the cohesion coefficients for all word pairs between two sentences is referred to as the sentence-level lexical cohesion coefficient, denoted as SentCo. Sentences with an average cohesion coefficient exceeding 80 when compared to other sentences are designated as central sentences. Furthermore, the number and ratio of central sentences are subsequently calculated. For more detailed information on this methodology, readers are referred to the works of Peng, Hu & Wu (2023).

Comparative analysis of classification models

Prior research has extensively explored machine learning approaches for text readability assessment (Heilman, Collins-Thompson & Eskenazi, 2008; Schwarm & Ostendorf, 2005). In comparative studies, Kate et al. (2010) evaluated multiple classification algorithms—including bagged decision trees, decision trees, linear regression, SVM regression and gaussian process regression—for text classification tasks. Their results indicated that bagged decision trees achieved optimal performance with a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.8173. However, other studies have demonstrated that SVM yield superior results in readability evaluation (Sung et al., 2013, 2015a), suggesting model performance may be task-dependent.

Given that existing studies primarily focus on general text classification tasks with varying model performance across different contexts, we conducted a systematic comparison of multiple established machine learning classifiers to identify the optimal model for our specific research needs. Through this empirical evaluation, we aim to determine the most suitable classification approach for our task. We primarily employed six traditional machine learning classification models for training: support vector machine (SVM), naïve Bayes (NB), k-nearest neighbors (KNN), logistic regression (LR), classification and regression tree (CART), and random forest (RF). We used the TF-IDF approach to lexical feature extraction in order to provide a contrast to the rule-based feature extraction approach. TF-IDF measures the importance of a word within a collection of documents (corpus) by combining term frequency (TF) and inverse document frequency (IDF). This approach highlights words that occur frequently in a specific document while diminishing the weight of words that are common across all documents, thus emphasizing more relevant and distinctive terms.

Given that the 73 fitness features are measured on different scales, we normalized them to ensure that no single feature dominates the model training process due to its broader range of values. The effectiveness of the model was assessed through a five-fold cross-validation during the training phase. The results, along with the model’s strengths and limitations, were analyzed using the F1-score, which is a balanced measure of precision and recall. Given the rising complexity of text levels, the model predicts HSK 1 text as HSK2 more correctly than HSK6. To more accurately differentiate between various text levels, we also incorporated near accuracy, which evaluates how closely the predicted levels align with the actual text level for the three primary features. This additional indicator provided a more nuanced assessment of the model’s performance in classifying texts across different HSK levels.

A higher F1-score indicates that the model achieves a good balance between precision and recall, two crucial metrics for evaluating classification performance. In comparison to the performance of the 73-feature system developed in this study (F1-score = 0.649–0.879), Table 3 shows that the F1-score for the features based on TF-IDF across the six classification models ranges from 0.41 to 0.67. This demonstrates that the features we constructed offer a better ability to distinguish the lexical adaptation of HSK reading texts and are more effective in performing the task of automatically assessing lexical fitness. Among them, the F1-score of RF reaches 0.879, with the best training results and the strongest evaluation ability.

| Classification models | 73-feature system | TF-IDF | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precision | Recall | F1-score | Precision | Recall | F1-score | |

| SVM | 0.843 | 0.843 | 0.842 | 0.694 | 0.698 | 0.673 |

| NB | 0.725 | 0.660 | 0.649 | 0.547 | 0.568 | 0.483 |

| KNN | 0.771 | 0.760 | 0.761 | 0.464 | 0.432 | 0.414 |

| LR | 0.844 | 0.843 | 0.842 | 0.677 | 0.637 | 0.599 |

| CART | 0.777 | 0.778 | 0.777 | 0.487 | 0.490 | 0.484 |

| RF | 0.883 | 0.880 | 0.879 | 0.649 | 0.588 | 0.571 |

Next, we conduct comparative experiments between the MHA neural network classifier and the RF model to identify the architecture with superior classification performance for further model refinement.

During the training process, we utilized the pre-trained Transformer model BERT for fine-tuning to reduce training time. The experimental result in Table 4 reveals that the precision, recall, and F1-score of the MHA model were lower than those of the RF classifier, further demonstrating that machine classification model based on rule-based lexical feature extraction performs more effectively. As a result, the RF classification model was ultimately selected as the automatic evaluation model for lexical fitness.

| Classification models | Precision | Recall | F1-score |

|---|---|---|---|

| RF | 0.883 | 0.880 | 0.879 |

| MHA | 0.828 | 0.815 | 0.809 |

Automatic evaluation of lexical fitness based on rf classification model

Following the above-mentioned experimental approach, we identified the ideal classification model RF and then investigated how each lexical feature as an indicator influences the assessment of lexical fitness based on RF. In addition, we evaluated the effectiveness of the three primary features on various levels of reading texts. Finally, to further optimize the assessment model, we leverage mutual information (MI) to remove redundant characteristics from the original data.

Impact of lexical features on evaluation performance

Table 5 presents the results of an additional analysis focused on the performance of the three primary features in evaluating text levels using the best-performing RF model. With an F1-score of 0.773, lexical meaning demonstrates the strongest evaluation capacity, only 0.106 lower than that of the 73-feature system. Lexical syntax ranks second, also achieving an F1-score of 0.773, but with a slightly smaller difference of 0.11 compared to lexical meaning. The lexical form feature, among the three primary features, exhibits the weakest performance, with an F1-score decrease of 0.067 compared to lexical meaning, the highest-performing feature. Additionally, it shows an F1-score decline of 0.173 when compared to the 73-feature system. Additionally, the near accuracies of the 73-feature system were 0.195, 0.122, and 0.13 higher than those of lexical form, lexical meaning, and lexical syntax, respectively. This suggests that most of the classification errors for the three primary features occurred within adjacent levels, further supporting the notion that the model’s ability to distinguish between adjacent levels of text complexity is relatively strong.

| Dimension | No. of features | Near accuracy | F1-score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lexical form | 14 | 0.705 | 0.706 |

| Lexical meaning | 12 | 0.778 | 0.773 |

| Lexical syntax | 47 | 0.770 | 0.769 |

| 73-feature system | 73 | 0.9 | 0.879 |

Next, we examine the assessment performance of the twelve supplementary features rooted in three primary features. Table 6 reveals that the strongest assessment ability is exhibited by the lexical meaning of words themselves (word-word), with an F1-score of 0.769. This is followed by the grammatical meaning of the words under the lexical level (word-word) with an F1-score of 0.689, and the lexical meaning of words in relation to the chapter (word-chapter) (F1-score = 0.194). These results suggest that the overall semantics of a Chinese chapter cannot be solely determined by the comprehension of individual subject words, highlighting the importance of context and syntactic structure in understanding the meaning of a text. A comparison of the F1-score rankings for the twelve supplementary features reveals that the word-specific (word-word) features generally exhibit superior assessment performance. This suggests that the lexical properties of Chinese, including lexical form, meaning, and syntax, are primarily determined by vocabulary itself, rather than by other linguistic elements. In contrast to other language types, such as analytic or isolating languages, in agglutinative languages, the meaning of each grammatical category is typically represented by a distinct morpheme that attaches to the root word. This distinction underscores the unique nature of Chinese vocabulary, where lexical form and meaning are largely independent of the grammatical markers that modify them.

| Three primary features | Twelve supplementary features | No. of features | F1-score | Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lexical form | morpheme-word | 5 | 0.405 | 6 |

| word-word | 4 | 0.472 | 5 | |

| word-sentence | 2 | 0.388 | 7 | |

| word-chapter | 3 | 0.510 | 4 | |

| Lexical meaning | morpheme-word | 1 | 0.351 | 10 |

| word-word | 9 | 0.769 | 1 | |

| word-sentence | 1 | 0.255 | 11 | |

| word-chapter | 1 | 0.194 | 12 | |

| Lexical syntax | morpheme-word | 3 | 0.385 | 8 |

| word-word | 16 | 0.689 | 2 | |

| word-sentence | 1 | 0.384 | 9 | |

| word-chapter | 27 | 0.621 | 3 |

Evaluation performance of three primary features at different levels of reading text

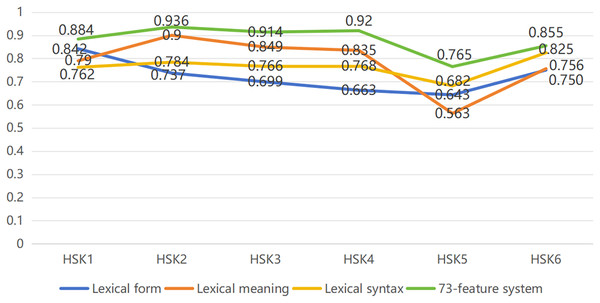

To assess the performance of each feature’s capacity for evaluating different reading text levels, we computed the corresponding F1-scores for the lexical form, lexical meaning, lexical syntax, and 73-feature system, respectively, and plotted them as line graphs to observe the assessment performance of each feature on different levels of reading text. Figure 1 demonstrates that the evaluation ability based on 73-feature system consistently outperforms the performance of the three primary features across all reading text levels. Among the various text levels, the HSK2 level shows the highest assessment performance, with an F1-score of 0.936, while the HSK5 level exhibits the weakest performance, with an F1-score of 0.765. Notably, there is little variation in the F1-scores for the lexical form, lexical meaning, lexical syntax, and 73-feature system between HSK1 and HSK2 texts. However, from HSK2 to HSK4, the performance disparities become more pronounced. At the next levels of text, they all seem to agree on a “downward-ascending” trend of performance, with a narrowing of the differences in assessment performance for the advanced reading texts.

Figure 1: Assessment performance of three primary features on different levels of reading text.

Among three primary features, lexical syntax and lexical meaning are generally stronger than lexical form assessment performance for HSK2 to HSK4 texts, but lexical syntax is dominant in HSK5 to HSK6. For HSK1 texts, lexical form exhibits the strongest evaluation capacity, with an F1-score of 0.842. However, as the reading text level increases, the ability of word form to assess the reading text from HSK1 to HSK5 decreases, with its F1-score dropping to 0.643 at HSK5. This decline is reversed at the final stage (HSK6), where lexical form show improvement. In contrast, when evaluating HSK2 texts, lexical meaning provides the best performance, with an F1-score of 0.9. However, the assessment ability of lexical meaning fluctuates more than that of the other features. Notably, during the HSK4 to HSK6, its F1-score drops significantly, from a higher position than that of lexical form and lexical syntax to the lowest point, reaching an F1-score of 0.563. It is not until the final stage of reading text at an advanced level that assessment performance in lexical meaning picks up and is nearly on par with performance in lexical form. For the lexical syntax assessment, performance remains stable from HSK1 to HSK4, with HSK6 texts (F1-score = 0.825) being the best assessment object and HSK5 texts (F1-score = 0.682) the weakest. Lexical syntax assessment performance, however, shows improvement in the final two levels (HSK5 and HSK6), surpassing the performance of lexical form and lexical meaning in these stage.

Optimal model after features screening

To enhance the accuracy and efficiency of the model for automatic vocabulary fitness assessment, we employed a feature extraction algorithm known as mutual information (MI). This algorithm helps eliminate redundant, noisy, or unnecessary features from the original data, thereby improving the performance of the model and making it more suitable for evaluating HSK reading test texts. MI measures the correlation between two variables, indicating the extent to which one variable provides information about another. In this study, MI is used to quantify the dependency of features on goal variables, such as categorical labels (text levels in this case). Initially, we calculated the MI values between the 73 features and their corresponding categorization labels. Table 7 lists the features above the mean of mutual information (MI > 0.27), and a total of 31 features were retained. The retained features were organized under the categories of lexical form, lexical meaning, and lexical syntax. Specifically, five features were retained under lexical form, six under lexical meaning, and twenty under lexical syntax, reflecting the most informative and relevant aspects for the task of automatic vocabulary fitness assessment.

| Num. | Features | MI | Num. | Features | MI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Intermediate words | 0.69 | 16 | Global_lexical_coheison | 0.36 |

| 2 | Elementary words | 0.66 | 17 | Average number of words in a clause | 0.36 |

| 3 | Advanced words | 0.66 | 18 | pron_density | 0.34 |

| 4 | Total number of words in chapter | 0.57 | 19 | Pronouns rate | 0.34 |

| 5 | A-word rates | 0.56 | 20 | C_NPS | 0.33 |

| 6 | D-word rates | 0.51 | 21 | local_noun_cohesion | 0.33 |

| 7 | Average number of semantic roles | 0.5 | 22 | Average number of strokes in vocabulary | 0.32 |

| 8 | central_sent_ratio | 0.49 | 23 | PPN_ratio | 0.32 |

| 9 | Written word rate | 0.48 | 24 | C-word rate | 0.31 |

| 10 | central_sent_num | 0.46 | 25 | Proportion of single-letter words | 0.31 |

| 11 | local_lexical_cohesion | 0.45 | 26 | Compound word rate | 0.31 |

| 12 | PN_ratio | 0.39 | 27 | subj_n_TTR | 0.3 |

| 13 | B-word rate | 0.38 | 28 | global_noun_cohesion | 0.3 |

| 14 | Semantic transparency | 0.37 | 29 | subj_p_ratio | 0.29 |

| 15 | Homophonic and homomorphic rate | 0.37 | 30 | Simple word rate | 0.29 |

| 31 | Average number of strokes in four-letter words | 0.28 |

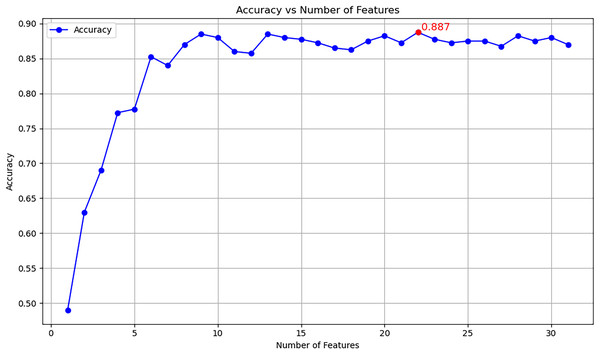

A line graph illustrating the contribution of 31 features to the classification model’s evaluation accuracy is shown in Fig. 2. In the graph, the vertical axis represents the model’s correctness, while the horizontal axis depicts the sequence of features progressively added to the model, ordered by diminishing MI values. As observed in Fig. 2, the model’s accuracy reaches a peak of 0.887 when the 22nd feature is included. After this point, the accuracy fluctuates in a wavy pattern as additional features are incorporated, but it never surpasses the initial value of 0.887. This indicates that the optimal set of features for automatic lexical fitness assessment is limited to the first 22 features, inclusive.

Figure 2: Accuracy vs. features.

The selected features are categorized as follows:

Lexical form: total number of words in chapter, average number of words in a clause, and average number of strokes in vocabulary.

Lexical meaning: elementary words, intermediate words, advanced words, written word rate, semantic transparency, and homophonic and homomorphic rate.

Lexical syntax: A-words rate, B-words rate, D-words rate, Average number of semantic roles, central_sent_ratio, central_sent_num, local_lexical_cohesion, PN_ratio, global_lexical_coheison, pron_density, pronouns ratio, C_NPS, local_noun_cohesion.

These 22 features form the most informative subset for improving the model’s accuracy in assessing the lexical fitness of reading texts in the HSK evaluation system.

Analysis and discussion

We developed an automated vocabulary fitness assessment framework tailored for L2 Chinese reading texts, aimed at enhancing the scientific rigor and validity of Chinese reading proficiency tests for second language learners. After testing and comparing various classification models and lexical feature extraction approaches, it was determined that the RF model achieved the best results. Compared to the TF-IDF lexical feature extraction method, rule-based lexical features demonstrated superior performance under the RF model, suggesting that improving vocabulary fitness requires a multi-dimensional exploration of vocabulary features. Moreover, automatically extracted lexical features do not always outperform manually extracted ones. The classification model utilized 73 features, encompassing a range of three primary and twelve supplementary features, including lexical form, lexical meaning, and lexical syntax. Assessment performance under the classification model varies for different features.

Assessment ability analysis of lexical form

Although lexical form exhibits a lower assessment capacity compared to the other three primary features, their F1-score is only 0.067 below that of the best-performing feature, lexical meaning. This suggests that lexical form can explain lexical fitness to some extent. Among the features under the lexical form, the correlation coefficient between the total number of words relative to the chapter and the level of the reading text amounts to 0.485, making it the best indicator for assessing lexical fit at the lexical form level. To further investigate, we randomly selected texts from HSK1 and HSK6 based on the superior performance of lexical form in assessing these two levels. Our analysis reveals that HSK1 texts typically consist of 2–4 short sentences, mostly composed of simple, everyday exchanges, such as “Thank you” and “You’re welcome.” In contrast, HSK6 texts have far more total words than HSK1 texts, up to hundreds or thousands of words, in a variety of genres, with full narrative or argumentative plots. This discrepancy highlights the shift in focus within the HSK from primarily assessing communicative competence in basic, everyday scenarios at lower levels to evaluating the ability to engage in logical reasoning, information retrieval, and more sophisticated discourse at higher levels. The significant difference in word count across these levels further underscores the sensitivity of text length as an indicator of proficiency, with longer texts signaling greater complexity and depth, which aligns with higher-level linguistic and cognitive abilities required at more advanced stages.

The average number of words in a clause, a new evaluation index introduced in this study, emerges as the second most significant assessment factor under the category of lexical form. This metric is notably more sensitive to text level than the average number of words in a sentence. As previously mentioned, primary reading texts predominantly consist of communicative phrases, where short sentences like “Thanks, I’ll see you tomorrow.” or “Okay, I’ll be home in a minute.” are commonly used for conveying everyday information. These brief exchanges reflect the functional, communicative nature of lower-level reading texts. However, as the reading text level increases, there is a noticeable shift toward more complex expressions. In higher-level texts, clauses are typically expanded to accommodate more logical intent, integrating additional semantic roles and discourse markers. This results in a gradual increase in the number of words within the clauses. It is important to note that sentence meaning is primarily conveyed through clauses, with the semantic richness of individual sentences being less pronounced than that of the clauses within them.

The average number of strokes in vocabulary, a key word shape variable in the best-performing classification model, is another important feature in evaluating lexical fitness. Strokes are a fundamental aspect of the Chinese language due to its logographic nature, where each character is composed of strokes that contribute to its visual complexity. Zhang (2008) posited that reading speed and accuracy are directly influenced by the number of strokes in a character; a higher stroke count typically leads to longer reading times and an increased error rate. Moreover, the average number of strokes per word reflects the cognitive load involved in visual word processing. For learners whose first language employs an alphabetic writing system, such as English or French, these visual complexities pose an additional challenge. In the context of reading proficiency, one- and two-character words dominate lower-level texts, while more complex, multi-character words, particularly idiomatic expressions, become more frequent in higher-level texts. As a result, the average number of strokes per word increases with the text level, contributing to more intricate visual processing. This greater visual complexity also correlates with longer word identification times, particularly for words with more characters, making this feature a key indicator of text difficulty (Fang, 1994; Chen & Su, 2010).

Assessment ability analysis of lexical meaning

Lexical meaning ranks first in terms of assessment ability across the three primary features, with the best assessment performance based on the features of the lexical meaning itself (word-word) (F1-score = 0.769). This dimension encompasses several key features, including synonym rate, homophone-homograph rate, polysemy rate, commonly used words rate, written words rate, idioms rate, and the classification of words by New Chinese Proficiency Test Outline (elementary, intermediate, and advanced words). Notably, five of the nine features—specifically the elementary, intermediate and advanced word rate, written words rate, homophone-homograph rate—show MI values greater than 0.27. These features are identified as the most significant contributors to the model’s optimal performance. In selecting appropriate words for the Chinese proficiency test, it is evident that the emphasis is placed on the meanings of words themselves, with particular attention paid to the leveled vocabulary outlined in the Outline. As Feng, Wang & Huang (2008) argued, the use of a rich written vocabulary effectively enhances the formality of the text, distinguishing it from spoken language. The Chinese language is particularly rich in homophones and polysemous words—terms that have multiple meanings but are pronounced the same or similarly. For example, the word huā can signify both the verb to spend and the noun flower. The prevalence of homophones and polysemous words in advanced reading texts significantly increases the complexity of meaning interpretation. This semantic ambiguity poses challenges for second language learners, who must rely on context to disambiguate the meanings of such words.

Semantic transparency is a crucial aspect of the lexical features integrated into the ideal model for assessing lexical fitness in Chinese reading texts. Laufer (1997) identified the concept of “deceptive transparency,” wherein learners mistakenly infer the meaning of an expression based on the individual meanings of the morphemes it comprises. This misinterpretation, according to Laufer, complicates the process of learning second language vocabulary. The findings of this study further underscore the role of semantic opacity, particularly at higher reading levels. As the reading text level increases, semantic opacity climbs along with it, thus exacerbating the issue of “deceptive transparency.” In Chinese, where most vocabulary is composed of two morphemes, the degree of semantic transparency can vary significantly. Semantic transparency is high when the meaning of a word is directly inferred from its constituent morphemes. In contrast, it is low when a word’s meaning is altered through derivation, metaphor, or other forms of figurative speech, making it harder for learners to deduce its meaning from the morphemes alone. For Chinese, a language in which two or more morphemes combine to form a word, it is essential to comprehend not only the semantics of individual morphemes (assuming they have inherent meaning) but also their combined, extended, and contextual meanings. This approach is crucial for accurately reflecting the learner’s vocabulary acquisition.

Assessment ability analysis of lexical syntax

The lexical syntax feature also demonstrates strong performance in assessing lexical fitness, with only a slight decrease of 0.004 in the F1-score compared to that for lexical meaning. Specifically, the F1-score for words relative to their syntactic features (word-word) reaches 0.689. The features included in the optimal model’s assessment metrics are Pronoun rate, A-words rate, B-words rate and D-word rate. Regarding pronouns, some scholars suggested that an overuse of pronouns can hinder reader comprehension and lead to confusion (Graesser, McNamara & Kulikowich, 2011). However, in the context of Chinese, the presence of additional pronouns can enhance the cohesion of a conversation, thereby improving comprehension. The increasing frequency of pronouns in texts as the reading level rises reflects a richer linguistic structure, contributing to a more coherent discourse. This suggests that the use of pronouns, in moderation, is beneficial for maintaining textual cohesion and comprehensibility, especially as the complexity of the reading material increases. Furthermore, comprehensibility is influenced by various factors beyond pronoun usage, such as pragmatic meaning and unmarked conjunction, which are particularly prevalent in Chinese. These factors work together to shape the overall clarity and accessibility of a text. The A-words, B-words, and D-words are categorized based on frequency, with commonly used words distributed across different levels of text. As the length of the text increases, the frequency of these commonly used words also increase accordingly. Infrequently used words rarely appear in elementary texts, mostly in advanced reading texts.

The grammatical features of words relative to sentences (word-sentence)—average semantic roles—are closely related to reading text level (MI = 0.5), and this difference is largely determined by text form. The primary purpose of elementary reading texts is to facilitate basic communication in diverse contexts, often adopting a conversational style. These texts are typically focused on simple exchanges and straightforward information. In contrast, advanced reading texts challenge students to comprehend more complex elements, such as the story’s initiator, the driving force behind the plot, and intricate details. The higher-level texts serve as a more comprehensive assessment of students’ reading proficiency, testing their ability to navigate nuanced meanings and more sophisticated discourse structures.

A range of syntactic features related to the chapter (word-chapter) are incorporated into the evaluation metrics of the optimal model, including lexical articulation metrics such as central_sent_ratio, central_sent_num, local_lexical_cohesion, local_noun_cohesion, and global_lexical_cohesion, as well as grammatical articulation indicators such as PN_ratio, pron_density, and C_NPS. These articulation features are vital for ensuring that the text is logically structured, allowing readers to follow the progression of ideas smoothly. A greater number and proportion of center sentences mean a tighter articulation factor between words from each center sentence. Global_lexical_cohesion accounts for the coherence between any two sentences across the entire text, while local_lexical_cohesion and local_noun_cohesion specifically focus on the relationship between adjacent clauses. In this study, grammatical articulation indicators correspond to the pronoun-noun ratio, pronoun density, and the number of conjunctions per sentence.It is well-established that pronouns and conjunctions are among the most common and effective articulators, enhancing the coherence of the text (Sanders, Spooren & Noordman, 1992; Crossley et al., 2007). Both grammatical and lexical articulation features have proven to be valuable tools for evaluating lexical fitness, emphasizing that the level of articulation between sentences should correspond to the reading text level.

Evaluating the efficacy of lexical feature extraction for text analysis

To highlight the advantages of the vocabulary-based features developed in this study, we compared them to existing research on Chinese language feature extraction. Table 8 displays the pertinent feature values of 1,332 HSK reading texts based on the vocabulary characteristics of Jiang et al. (2020) and Du, Wang & Wang (2022), using the same corpus as the experimental object. Our comparison reveals that the vocabulary features constructed in this study are the most effective in assessing the lexical fitness of the texts. Specifically, the features we developed outperform those of Jiang et al. (2020) by an F1-score margin of 0.23, and exceed those of Du, Wang & Wang (2022) by 0.068. To address this latter difference, we introduced new variables, such as articulation words and the average number of words per clause. These findings suggest that the features we propose offer a more accurate means of evaluating the lexical fitness of reading texts across different proficiency levels.

| Lexical features construction method | F1-score |

|---|---|

| Jiang et al. (2020) | 0.694 |

| Du, Wang & Wang (2022) | 0.811 |

| The features of this study | 0.879 |

Conclusion

Vocabulary is the emphasis of second language learning, and reading examinations are the greatest way to determine whether students have acquired vocabulary, so improving the lexical fitness of reading texts is especially crucial. To evaluate the lexical fitness of reading texts, we devised a lexical feature-based text categorization experiment. Beginning with the construction of a specialized HSK reading corpus, we systematically evaluated both traditional machine learning classifiers and neural network model incorporating MHA mechanism. Our comparative analysis revealed that the RF algorithm achieved superior performance among conventional approaches. Throughout this experimental process, we meticulously incorporated lexical features to ensure robust assessment and interpretation of lexical fitness.

As a result, it is not the case that the more complex and automated the classification model is the optimal choice for classification experiments; rather, the optimal classification model should be chosen based on the goal of corpus construction and the characteristics of the corpus, and the representativeness of the corpus should be put in one place, including the target population served by the corpus, the various ways of distribution of linguistic features (Biber, 1993). In the digital era, numerous self-constructed, small-scale, and domain-specific corpora are emerging. The selection of research techniques or methods should be carefully considered from the perspective of the corpus, as the design and composition of the corpus significantly influence the reliability and generalizability of the research findings (Miller & Biber, 2015).

Furthermore, we have integrated additional lexical feature indicators based on previous research, and for the first time, lexical aspects of discourse articulation are being assessed in reading test texts. The experimental results indicate that these additional metrics enhance the evaluation performance of the classification model and can serve as one of the criteria for determining lexical fitness.