The rise and fall of DAOstack: lessons for decentralized autonomous organizations

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Sedat Akleylek

- Subject Areas

- Human-Computer Interaction, Databases, Distributed and Parallel Computing, World Wide Web and Web Science, Blockchain

- Keywords

- Blockchain, Computer-supported cooperative work, Decentralized autonomous organizations, DAOs, E-democracy, Online governance, Quantitative research, Qualitative research, Voting system, Online communities

- Copyright

- © 2025 Davó et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2025. The rise and fall of DAOstack: lessons for decentralized autonomous organizations. PeerJ Computer Science 11:e3320 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3320

Abstract

Despite the hype and scandals around blockchain, there are valuable applications beyond finance, such as decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs). DAOs are self-governed online communities where users vote and manage budgets transparently. In under a decade, DAOs have evolved from theory to managing billions of dollars. Blockchain enthusiasts launched DAO platforms like our case study, “DAOstack”, promising large-scale collaboration and quickly securing millions in funding. Today, we can critically evaluate to what extent the platform followed up on its promises. In this work, we analyze DAOstack using a mixed-methods approach combining quantitative and qualitative data. In particular, we quantitatively examined its 92 organizations in terms of size, lifespan, activity, power concentration, and the effectiveness of its governance model. We also interviewed in-depth 6 DAOstack core users to delve deep into their experiences using the platform. Our analysis shows that DAOstack mainly hosted small, short-lived DAOs, with some exceptions. Its governance model was functional, but the economic incentives underpinning it were ineffective. The analysis of the interviews reveals interesting aspects such as the power imbalances due to token ownership and reputation, and that the voting system, though innovative, was affected by issues of cost and complexity. We conclude by discussing the challenges these platforms face and advocating for a multidisciplinary experimental approach for future DAO designers.

Introduction

Blockchain technology, introduced with Bitcoin in 2008, aimed to build distributed peer-to-peer systems and was seen as a solution for many complex issues. Despite media notoriety due to scandals and scams involving cryptocurrencies and non-fungible tokens (NFTs) (White, 2024), blockchain has found applications beyond finance, such as in supply chains, Internet of Things (IoT), and governance (Mohanta, Panda & Jena, 2018; Hassan et al., 2020; Dong et al., 2023). In 2016, decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs) emerged, enabling self-governance through smart contracts on public blockchains (Hassan & Filippi, 2021). Today, DAOs manage $24 billion (as of February 2024 in deepdao.io), with thousands of communities and millions of users (Peña-Calvin et al., 2024a). After nearly a decade of DAOs, today we can critically evaluate the promises and work of those blockchain enthusiasts. And yet, a decade on, the scorecard is mixed. Some high-profile DAO platforms, celebrated as governance breakthroughs, have quietly vanished, leaving millions of dollars and thousands of contributors in limbo. Why do ostensibly successful DAO ecosystems unravel, and what socio-technical factors influence that trajectory? To probe this puzzle, we trace the full life-cycle of a flagship platform, DAOstack, situating its rise and abandonment within the broader history of DAO governance. Proposed a decade ago by Ethereum’s founder (Buterin, 2014), the term DAO refers to a blockchain-based system that enables people to coordinate and govern themselves mediated by a set of self-executing rules deployed on a public blockchain, and whose governance is decentralized (Hassan & Filippi, 2021). This model eliminates the need for centralized control, aiming to create a more democratic and efficient way to manage collective resources and projects, and aligns with the broader vision of decentralized finance and governance in the blockchain ecosystem. In practice, DAOs are server-less blockchain applications focused on decision-making and transparent budget management, where voluntary community members create and vote on proposals to allocate funds (Lustenberger et al., 2024; Ellinger et al., 2024). Unlike traditional apps, they do not rely on central servers, which blockchain advocates frame as a benefit of avoiding centralized power. However, without a central provider, users must pay micro-fees to interact with the software, leading to a controversial “pay to vote” situation.

The first attempt to build a DAO, in 2016, was infamous. With the confusing name TheDAO, it was a form of hedge fund that attracted $150 M in a month. It promised high algorithmic automation, with code making decisions rather than employees. However, errors in its source led to a $50 M hack, causing a public uproar and the project cessation (Peck, 2016; DuPont, 2017). This case showcased both the perks of algorithmic automation and economic incentives, and the problems inherent to serverless blockchain programming, where code is deployed to a public blockchain without central control.

The DAO disaster, rather than discouraging DAO advocates, fueled their determination to innovate, leading to a new approach in DAO building. Instead of developers coding each DAO, platforms offering DAO-as-a-service emerged, using tested, modular code. Users no longer needed to write code to launch a DAO. The first such platforms, announced in 2016, were Aragon (Peña-Calvin et al., 2024b), Colony (Mannan, 2018), and DAOstack. These pioneering efforts contributed to the rise of DAOs (Bellavitis, Fisch & Momtaz, 2023).

Over time, Colony was never widely used, whereas Aragon and DAOstack have followed different trajectories: Aragon remains active, although it has undergone various product changes, while DAOstack experienced a brief yet intense life that merits analysis. Originally, DAOstack was touted as the “WordPress for DAOs” (DAOstack, 2017), with a governance model for “large-scale collaboration” to solve cooperation scalability (Field, 2018). The hype led to their initial coin offering (ICO) selling out in 66 s, raising $30 M. By 2023, DAOstack had ceased all activity. What happened during this period? Did the platform fulfill its ambitious promises for large-scale communities?

DAOstack gained momentum and stayed true to its founding vision until its 2023 deprecation, making it an ideal case for a postmortem analysis of the challenges DAOs confront. Accordingly, this article asks: What socio-technical factors explain the rise and eventual abandonment of the DAOstack platform, and what lessons can other DAO ecosystems draw from that trajectory? To answer, we combine quantitative on-chain evidence with qualitative testimony, illuminating the platform’s full life-cycle and extracting a series of design recommendations for future DAO governance.

This study makes four contributions. First, to our knowledge, it presents the first postmortem of a DAO platform. Moreover, it does so through mixed methods, covering 7 years of evolution. Second, it empirically examines Holographic Consensus (a prediction-market-based governance model) in production, informing debates on scalable attention-efficient governance. Third, it distills practical design recommendations that can inform the development of current and future DAO platforms. Fourth, we outline a schema of DAO fragility, informed by patterns observed in the collapse of DAOstack, one of the first-generation DAO platforms, linking start-up mortality economics, blockchain immaturity, evolving DAO norms, and peer-production churn. In fact, we conceptualize early DAO platforms as socio-technical governance laboratories akin to living labs: open, data-rich arenas where novel voting and incentive schemes can be tested in-vivo.

In order to do so, the following sections analyze (1) DAOStack history and evolution, highlighting critical milestones; (2) the communities it hosted, including their activity, size, lifespan, and power concentration; (3) whether the ambitious claims of large-scale governance were met by the DAOstack governance model; (4) the effectiveness of its techno-determinist model with economic incentives; (5) and DAOstack users’ experiences with DAOs, the platform, and its voting system, after interviewing them.

Literature review

Despite their recent appearance, DAOs have attracted the interest of researchers, since DAOs theoretically combine features from classical peer production communities (Morell, 2014) and collaborative businesses (Scholz & Schneider, 2016). A first wave of research was purely theoretical, but in recent years empirical research, both quantitative and qualitative, has emerged.

Most empirical research focuses on the comparison of DAO platforms (El Faqir, Arroyo & Hassan, 2020; Faqir-Rhazoui, Arroyo & Hassan, 2021a; Ma et al., 2024). Still, each DAO platform, as an ecosystem of multiple online communities, is an appealing subject of study. Thus, they have also been analyzed on their own, like a quantitative study of the Snapshot DAOs (Wang et al., 2022), a qualitatively study of Aragon DAOs (Peña-Calvin et al., 2024b), or a study of Aragon architecture (Dhillon et al., 2021). Concerning the DAOstack platform, its development process was qualitative studied (Skarzauskiene, Maciuliene & Bar, 2021), as well as a quantitative validation of its decision-making process (Faqir-Rhazoui, Arroyo & Hassan, 2021b). Its governance is compared with others in Ding et al. (2023), and the governance structure of dOrg, one of its most popular DAOs, has also been analyzed (Mannan, 2023). In other cases, characteristic DAOs from the DAOstack ecosystem were deeply analyzed, both quantitatively and qualitatively (Brekke, Beecroft & Pick, 2021; Sharma et al., 2024; Baninemeh, Farshidi & Jansen, 2023). Regarding DAOstack’s governance model, Holographic Consensus (HC), our work expands and complements that of Faqir-Rhazoui, Arroyo & Hassan (2021b), who provided a preliminary assessment of HC’s scalability using on-chain data from a 15-month period (Apr 2019 to June 2020). While their analysis focused solely on HC, we examine the entire DAOstack platform across its full life cycle. In doing so, we not only cover HC’s operation from 2019 to its deprecation in 2023, but also provide additional statistical analyses that offer deeper insights into its performance and limitations. Furthermore, we complement the analysis with a qualitative analysis interviewing DAOstack members about the platform.

Multiple DAO platforms have died over time, like Colony, which never attracted widespread adoption. In fact, it is well known that many blockchain projects collapse due to fraud, scams, never being fully developed, or legal troubles (White, 2024). However, that was not the case with DAOstack. The platform attracted ample funding, was often praised for its development and governance (Guida, 2022; Liebkind, 2019; Roy, 2023; Foxley, 2020), and some of its DAOs reached wide success. Today, the open nature of the blockchain enables us to deep dive into its history and perform a systematic postmortem that would not be possible in other kinds of projects. To our knowledge, no other article provides an analysis of the evolution of a DAO platform, neither quantitatively nor qualitatively–and this work combines both approaches.

Fragility of the first-generation DAO platforms

Early DAO platforms faced a unique convergence of risk factors. Like other nascent ventures, they were exposed to start-up mortality economics: 60–90% failure rate in the first few years in the United States, depending on the source (Phillips & Kirchhoff, 1989; Keogh & Johnson, 2021). Still, several start-up hurdles were initially cleared: all major DAO platforms attracted ample early funding, rode the blockchain-hype wave, and addressed a clear market need highlighted by the TheDAO disaster.

On top of ordinary start-up risk, DAO platform builders contended with additional pressures:

Conceptual immaturity of DAOs. Early definitions of a DAO were fluid and often contradictory. Practical requirements evolved in lock-step with the very platforms meant to implement them, creating moving targets for developers and users alike. Comparative analyses of the first-generation DAO frameworks show that despite offering diverse toolsets and design philosophies, these initiatives lacked a shared conceptual foundation and made little effort to ensure interoperability across ecosystems (Valiente, Pavón & Hassan, 2021). These aspects hampered the development of robust, usable, and reliable tooling.

Blockchain immaturity and fee volatility. Ethereum in 2017–2021 was still a fast-moving research platform: tools, application programming interfaces (APIs), and contract standards changed frequently, documentation lagged, and gas-price spikes disrupted normal usage (Epps, 2021; Jagati, 2020; Faqir-Rhazoui et al., 2021).

Mismatch between web-development culture and blockchain risk. Traditional web start-ups embrace a “move fast and break things” ethos, assuming bugs can be patched post-deployment. By contrast, deployed smart contracts are immutable: a single error can lock or drain millions in funds, as illustrated by the 2017 parity incidents (Suberg, 2017; Hern, 2017). The resulting high-assurance development practices, a different paradigm, slow down release cycles, and severely limit the pool of qualified developers.

Usability trade-offs for decentralization. Maximizing decentralization and security often means minimizing convenience (Swartz, 2011). First-generation wallets, key-management schemes, and on-chain voting flows imposed cognitive overhead that discouraged mainstream adoption (Saldivar et al., 2023).

Peer-production community instability. As online communities, DAOs inherit the churn patterns of open-source and wiki projects: high rates of abandonment and a long tail of tiny projects (Kaur & Chahal, 2022; Tenorio-Fornés, Arroyo & Hassan, 2022). This social volatility compounds the technical and economic fragility noted above.

In practice, these early DAO platforms faced challenges that, combined, characterized the structural fragility of the first-generation DAO platforms. We can see in this article the specific case of DAOStack, but it was generalized. Colony, which also attracted ample funding and developed its platform for years, never took off. Even Aragon, the most successful first-generation Aragon platform, had a very long list of issues, including the complete abandonment of their first architecture, even if thousands of DAOs were using it, and reimplementing its system from scratch years later. Besides, it suffered multiple major governance crises, including the resignation of its chief executive officer and leadership due to governance decisions (McNally, 2021), interventions to stop a hostile takeover due to misuse of governance tokens (Aragon, 2023a), the dissolution of the Aragon Association and the governance token ANT (Aragon, 2023b), and the DAO voting in favor of taking legal action against its founders (Reguerra, 2023).

We therefore frame first-generation DAO platforms as socio-technical governance laboratories: open, data-rich living-lab environments (Ballon & Schuurman, 2015) where novel voting rules and incentive schemes can be tested at Internet scale. The following sections trace how these fragility factors and experimental dynamics unfolded in DAOstack’s life cycle.

The history of DAOstack

Beginnings and early growth

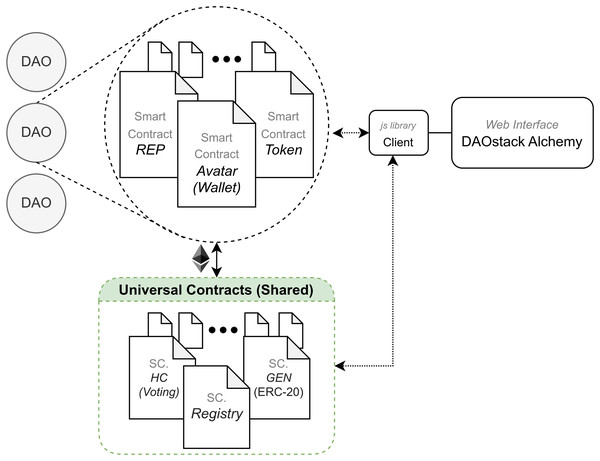

DAOstack originated in late 2016 with the creation of its GitHub organization, according to the GitHub API (https://docs.github.com/en/rest?apiVersion=2022-11-28). Shortly thereafter, it secured seed funding from two Israeli investors and the venture capital fund (https://finder.startupnationcentral.org/company_page/daostack). The first version of its whitepaper (DAOstack, 2017), detailing its technical specifications, was released in October 2017. DAOstack leveraged several blockchain affordances, including a crypto-token (GEN) for its decentralized governance model, self-executing smart contracts, and deployment on a public blockchain (see Fig. 1). It ensured transparent accounting for all DAOs, with operations recorded on the public blockchain. Each DAOstack DAO has a treasury, and users can create and vote on proposals, which may reallocate treasury funds (Levy, 2019).

Figure 1: Diagram showing the composition of a DAOstack DAO.

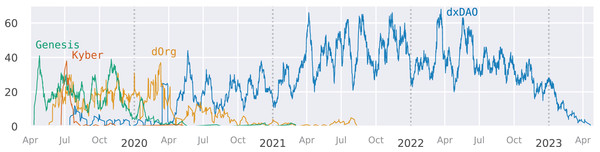

In April 2018, DAOstack conducted its ICO for GEN, raising 45,000 ETH valued at USD 30 million (Zemel, 2018), and it began operations with the launch of the Genesis Alpha DAO, a pioneering example that showcased the platform’s capabilities and enabled community engagement in governance and decision-making (Reed, 2019). As Fig. 2 shows, DAOstack activity started in April 2019. It initially experienced a steady increase in DAOs deployed until it plateaued at 22 in April 2020. During this period, approximately two-thirds of the 900 users who actively participated joined the platform.

Figure 2: Number of deployed DAOs (dotted) and DAOs with activity in the last 30 days (solid) on Ethereum mainnet (blue, above) and xDai chain (orange, below).

The graph starts in April 2019 with the creation of the first DAO and ends in May 2023, when the last DAO disbanded.In the first half of 2019, notable communities like dOrg and dxDAO joined (Arroyo et al., 2022). dOrg provides web3 development services, functioning as a traditional cooperative. dxDAO was created to govern DutchX, a decentralized trading protocol, and later expanded to support and develop new decentralized projects. A month later, in June 2019, the Kyber Network conducted a 60-day trial with DAOstack involving about 5,000 members (Kyber Network, 2019a, 2019b). They previously used the Aragon platform to search for software for community creation and governance. During the trial, proposal votes were low, and many proposals failed to gain majority support.

Another notable DAO was necDAO, a decentralized finance exchange launched in January 2020 with a treasury of 17,000 ETH ($2.8 M at the time), making it one of the largest DAOs then (https://rhino.fi/blog/deversifi-community-update-05-q2-2020/). Overall, DAOs on DAOstack often focused on blockchain projects. However, DAOstack also hosted DAOs with broader scopes, such as CuraDAO, which promoted sustainable development projects in Curaçao (https://web.archive.org/web/20201028111857/https://curadao.io/).

Maturity and stagnation

As Fig. 2 shows, despite regular creation of new DAOs since the beginning, the number of active DAOs plateaued at around 10 in July 2019 and remained stable for almost a year. During this period, DAOstack failed to consolidate its achievements, as it was unable to secure lasting user engagement, and most organizations that emerged did not endure for long.

In early 2020, DAOstack launched on the xDai sidechain (yellow in Fig. 2), a secondary blockchain linked to Ethereum, to facilitate faster and more cost-effective operations. This move anticipated the high costs, instability, and congestion that Ethereum faced in late 2020 (Jagati, 2020; Faqir-Rhazoui et al., 2021). As the figure shows, these issues led to a decline in DAO activity on Ethereum from the second half of 2020 onward but did not generate sustained activity on xDAI, despite the substantial effort DAOstack dedicated to it. To promote the xDai launch, DAOstack showcased a gamified experience with BuffiDAO at ETHDenver 2020, adding 2,700 members and enabling voting for the best presentations (ETHDenver, 2020). Post-event, over 30 DAOs were established on xDai, but most were soon abandoned. Only xDXdao and “DAOstack DAO” remained, the latter incentivizing proposals for DAO use cases in DAOstack. Despite its timely release, the xDai version of DAOstack struggled to maintain a user base.

Thus, as it happens in social network sites (Zhang et al., 2015), DAOstack stagnation was not due to a lack of user base, but due to user and community inactivity. Furthermore, in early 2020, Genesis Alpha, the DAO facilitating community governance of DAOstack, disbanded due to a mismatch of aims between participants and the DAOstack team (Kate and Livia, 2020). Tensions over accountability, community building beyond self-interest, and fund management efficiency led to its downfall. Such problems, illustrating the challenges of collectively managing a project in a decentralized and democratic manner, led to Genesis Alpha’s failure, contributing to the eventual collapse of DAOstack (Rachmany, 2020).

Decay and abandonment

Following the early 2020 issues, the number of active DAOs declined starting in May 2020, with no new DAOs joining after 2020. By mid-2021, only dxDAO and necDAO remained active; other active organizations migrated to other platforms, including off-chain voting platforms as Snapshot. This was the case of dOrg.

In early 2021, DAOstack developers ceased supporting its applications. Despite this, a small community of 20–40 weekly active users persisted. In November 2022, the web interface was disabled. dxDAO attempted to continue by re-deploying its own version of the interface, but by April 2023, its members voted to cease using DAOstack, leading to the total abandonment of the platform (https://web.archive.org/web/20230519231319/https://daotalk.org/t/restructuring-execution/5094). DAOstack declined while other DAO platforms like DAOhaus and Snapshot emerged and grew. Meanwhile, Aragon struggled with relevance, undergoing various changes and launching new blockchain solutions while deprecating the established ones. Snapshot, an off-chain voting solution with no transaction fees, gained significant traction, hosting over 68 K DAOs (Peña-Calvin et al., 2024a). Despite being a pioneering platform, DAOstack illustrates the challenges of thriving in a competitive and technologically immature environment.

Quantitative analysis of DAOstack

In this section, we analyze DAOstack DAOs’ features, comparing them to other peer production communities using the DAO-Analyzer dataset (Arroyo et al., 2022), covering the entire platform lifespan1 . The original dataset contains data from multiple DAO platforms and 6,000 DAOs and contains multiple tables for each platform. In particular, we use the daostack folder that contains the following data files from DAOstack:

daos.csv: Contains the DAO’s name and network information about each deployment.

proposals.csv: Stores the proposer, stage of the proposal (executed, in progress, etc.), and its state change timestamps (when it was created, when it closed, etc.).

votes.csv: When the vote was cast, if it was for or against, and the user and his or her reputation at the moment.

stakes.csv: Information about each stake made to each proposal. Stores the amount staked, when it was staked, by whom, and if it was for or against the proposal’s success.

reputationMints.csv and reputationBurns.csv: These tables store how much reputation was assigned or removed from a user and its date. They were used to determine the members of each DAO and the reputation distribution of a DAO at a certain time.

The data was processed using Pandas, Numpy, and the rolling Python libraries. The scripts and Jupyter Notebooks produced are available in GitHub (https://github.com/daviddavo/daostack-analysis doi: 10.5281/zenodo.16420583).

DAOstack community characteristics

We analyze DAOstack from a quantitative perspective, examining the platform’s adoption, engagement, and power concentration at the organizational level. These indicators help us understand whether DAOstack communities resemble or diverge from those of other DAO platforms or online peer production communities.

Table 1 displays a characterization of the DAOs hosted by DAOstack. The table includes metrics to describe the DAO lifespan, such as the number of months with proposals (MWP) and the month when the first proposal was put forward (First Prop). It also includes metrics to describe the size of its community and their voting activity: the number of members of the DAO (# Members), the percentage of voters among those members (% Voters) and the number of proposals put forward in the DAO (# Prop). The table also includes two metrics to evaluate the effectiveness of the DAO voting process that will be explained and analyzed in ‘Evaluation of the Holographic Consensus Voting System’, namely, the percentage of proposals that were approved in the DAO (% Appr.) and the precision of the staking (i.e., prediction) mechanism. As DAOstack used a token-weighted voting system, the table includes two popular metrics that measure voting power concentration on DAO, namely, the Nakamoto Coefficient (NC) and Gini Index that will be explained below.

| DAO Name | MWP | First prop. | Memb. | % Voters | # Prop. | Appr. | Prec. | NC (%) | Gini | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethereum mainnet | dxDAO | 46 | Jul ’19 | 489 | 27% | 918 | 86% | 99% | 16 (3%) | 0.90 |

| necDAO | 20 | Jan ’20 | 140 | 28% | 43 | 65% | 88% | 5 (3%) | 0.89 | |

| Genesis Alpha | 18 | Apr ’19 | 268 | 48% | 387 | 70% | 97% | 62 (23%) | 0.38 | |

| CuraDAO | 17 | Aug ’19 | 55 | 20% | 49 | 80% | 96% | 20 (36%) | 0.22 | |

| dOrg | 16 | Mar ’20 | 31 | 55% | 127 | 95% | 56% | 3 (9%) | 0.71 | |

| PolkaDAO | 15 | May ’19 | 74 | 32% | 82 | 77% | 98% | 12 (16%) | 0.64 | |

| dOrg (0xbe1a) | 12 | May ’19 | 25 | 76% | 317 | 85% | 22% | 3 (12%) | 0.61 | |

| PrimeDAO | 10 | Dec ’20 | 95 | 5% | 37 | 73% | 97% | 18 (19%) | 0.47 | |

| FestDAO | 10 | Oct ’19 | 39 | 39% | 86 | 78% | 100% | 4 (10%) | 0.67 | |

| Kyber DAO Exp#2 | 8 | Jun ’19 | 4,946 | 1% | 56 | 27% | 96% | 711 (14%) | 0.51 | |

| DAOfund | 8 | Jul ’19 | 8 | 88% | 49 | 88% | 47% | 3 (38%) | 0.14 | |

| General store | 7 | Jul ’19 | 10 | 60% | 30 | 67% | 43% | 5 (50%) | 0.3 | |

| efxDAO | 6 | Jun ’19 | 26 | 42% | 16 | 75% | 100% | 11 (42%) | 0.16 | |

| 1UP | 5 | Mar ’20 | 14 | 29% | 40 | 68% | 98% | 3 (21%) | 0.64 | |

| CENNZnet Grants | 5 | Apr ’20 | 12 | 67% | 21 | 91% | 100% | 5 (42%) | 0.16 | |

| DetroitDAO | 4 | Oct ’19 | 6 | 50% | 11 | 91% | 9% | 3 (50%) | 0.18 | |

| dOrg (0xd358) | 3 | Feb ’20 | 22 | 46% | 44 | 89% | 16% | 4 (18%) | 0.57 | |

| ETHGlobal | 2 | Nov ’19 | 48 | 50% | 19 | 37% | 84% | 23 (48%) | 0.04 | |

| xdai | xDXdao | 29 | Nov ’20 | 402 | 23% | 1,438 | 93% | 97% | 14 (3%) | 0.88 |

| DAOstack DAO | 6 | Feb ’20 | 6 | 67% | 13 | 15% | 85% | 3 (50%) | 0.01 | |

| 3Box | 4 | Feb ’20 | 5 | 60% | 8 | 63% | 38% | 3 (60%) | 0.02 | |

| Secret DAO | 2 | Feb ’20 | 7 | 43% | 6 | 83% | 17% | 3 (43%) | 0.28 | |

| Lendroid Taleb | 1 | Feb ’20 | 4 | 75% | 4 | 100% | 0% | 2 (50%) | 0.01 | |

| Pepo UX Awards | 1 | Feb ’20 | 4 | 75% | 2 | 50% | 50% | 2 (50%) | 0.00 | |

| QuorumDAO | 1 | Feb ’20 | 6 | 50% | 4 | 75% | 25% | 3 (50%) | 0.01 | |

| BuffiDAO | 1 | Feb ’20 | 2,830 | 0% | 22 | 73% | 27% | 16 (0.6%) | 0.96 |

Regarding adoption, DAOstack hosted a total of 92 DAO deployments—25 on the Ethereum mainnet and 67 on xDAI. The platform registered over 9,000 user addresses, with Kyber Network (5,000 users) and BuffiDAO (2,700 users) making up the majority. These two DAOs were experimental, with members added programmatically with a predefined voting power. In DAOstack, very few wallets belong to more than one DAO (1%, or 8% excluding BuffiDAO and Kyber Network addresses). Genesis Alpha had the highest number of members in other DAOs (72 of 266). Created to aid DAOstack governance, Genesis Alpha included members from DAOs like dOrg and necDAO (Reed, 2019). Similarly, while users could cease to be members of a DAO, this barely happened: they simply stopped participating. This is a well-known phenomenon in online communities (Zhang et al., 2015).

Regarding the organizations’ size, half the DAOs have three or fewer members, only 15 DAOs (16%) have more than 20 members, and just six have over 100 members. This pattern of small communities is common in other online collaborative environments, such as wikis or open-source projects, where large communities are rare, e.g., even if large projects like React or Tensorflow exist, the vast majority of GitHub projects have just one contributor (Berkholz, 2013).

For comparing DAOstack adoption with those of other platforms it coexisted with at the time, we will use DAO-Analyzer (Arroyo et al., 2022), a dashboard for DAOs publicly deployed (https://dao-analyzer.science/). As of September 2024, DAOhaus and Aragon had around 3.5 and 2.4 k DAOs, respectively, far surpassing DAOstack’s 92 organizations. Similarly, in April 2020, when DAOstack activity peaked with 12 active DAOs, DAOhaus had 20 active DAOs, and Aragon had 158. Thus, we can conclude that DAOstack’s adoption was significantly more limited compared to that of its peers. It suggests that, similarly to traditional web services and applications, it is difficult for a blockchain platform to gain adoption, maintain it, and thrive among competitors.

Regarding engagement, we focus on DAOs with some level of activity. The criteria we used were fairly lenient, as we only excluded DAOs with no proposals or fewer than three distinct voters, assuming they were casual tests. Based on this criterion, there were 26 DAOs (18 on the mainnet and eight on xDAI) with some activity on DAOstack. These DAOs are shown in Table 1. In the rest of this manuscript, we merged the three dOrg deployments into a single organization and combined the Ethereum and xDai instances of dxDAO. After this postprocessing, 23 organizations remain: 15 on mainnet, seven on xDai, and dxDAO on both networks.

If we measure the period of activity of a DAO as the time between the first and last proposal, only nine organizations ( 39%) lasted more than a year, and four lasted over 2 years. In some cases, these numbers can be distorted by an isolated proposal submitted months after cessation of real activity. To further measure the intensity of an organization’s activity over time, we will also consider the number of months with proposals (MWP in the table). According to this metric, just six DAOs ( 26%) had proposals in 12 or more months, and only dOrg and dxDAO had proposals in over 24 months. dxDAO was the most active, with proposals in 45 months and 2,356 proposals.

Using the DAO-analyzer dashboard, we observe that in DAOhaus and Aragon, there were 105 and 64 active DAO deployments, respectively, in the last 12 months as of June 2024. These numbers, less than 5% of the total DAOs, indicate a similar pattern of high DAO abandonment across platforms. Abandoning a DAO is common, akin to other peer production communities like wikis and open-source projects (Kaur & Chahal, 2022). Some DAOs are used for temporary actions, such as event organization, while others run short-lived “entrepreneurial” projects. All these factors contribute to the high abandonment. DAOstack did not survive because it failed to continuously enroll enough organizations to eventually host a sufficient number of long-term projects.

As for power concentration, DAOstack replaced the “one-person-one-vote” principle with weighted voting. While it prevents Sybil attacks (multiple wallets mimicking multiple users), it often leads to a concentration of power in the hands of a few. In DAOstack, individual voting power, or Reputation (REP), is allocated by the DAO and earned through active engagement, task completion, and voting in line with community values (DAOstack, 2017). In practice, REP is usually allocated at the DAO’s creation or through proposals and is nontransferable to prevent wealth-based power accumulation.

To assess power concentration in DAOstack DAOs, we employed common metrics found in other analyses of DAO voting power, namely the Gini Index and the NC (Fritsch, Müller & Wattenhofer, 2024; Barbereau et al., 2023). The NC measures the minimum percentage of members whose aggregated voting power exceeds 50% of the total (see Table 1), serving as an indicator of the degree to which a subset of members can enforce decisions on the rest of the DAO participants. A strong Spearman correlation of −0.95 between the Gini Index and the NC suggests these two metrics can be used interchangeably to quantify inequality. Investigating the relationship with DAO size, a correlation coefficient of −0.36 was found between the number of DAO members and the NC percentage. This finding indicates that within DAOstack, smaller DAOs typically exhibited more egalitarian power structures, whereas larger DAOs tended to be more unequal. However, it is also possible to find examples of large DAOs that contradict this general trend, e.g., Genesis Alpha or PrimeDAO, which had no marked power concentration (around 20% of NC).

Power concentration has also been observed in a broader context, such as the census of DAOs in Peña-Calvin et al. (2024a). It suggests DAOs may conform to the “iron law of oligarchy” observed in online peer production communities (Shaw & Hill, 2014). The problem is not only that oligarchies may hinder participation and commitment, as has been analyzed in projects as Wikipedia (Rijshouwer, Uitermark & De Koster, 2023), but also that they undermine the decentralized governance intended by DAOs.

Evaluation of the holographic consensus voting system

In this section, we quantitatively analyze how the DAOstack voting system performed. As described above, DAO members typically make proposals (e.g., to allocate funds to a specific task) that are voted on collectively. Thus, the decision-making system is the core of a DAO. Before assessing whether the DAOstack voting system performed as expected, we first explain how it works and the intent behind its design.

In particular, DAOstack used the HC, a voting system with the aim of addressing scalability and resilience. According to its developers, requiring too much collective attention for every decision makes decentralized governance non-scalable. However, requiring too little attention makes it vulnerable to faulty decisions and collusion (Field, 2018). HC aims for scalability by not requiring an absolute majority to pass proposals in all cases and claims resilience by preventing minority hijacking, i.e., approving proposals not interesting to the DAO.

Specifically, HC uses a prediction market to filter proposals. Individuals (both from the DAO and outside of it) place bets called stakes on proposals’ success or failure. If the success-to-failure bet ratio exceeds a threshold, the proposal is boosted and requires only a relative majority, bypassing the 50% quorum for non-boosted proposals. Bets are placed using GEN tokens2 , incentivizing informed decisions aligned with the DAO. The network of stakers supposedly acts as a “hologram” representing the DAO’s global opinion, hence the name holographic consensus. Boosted proposals require a simple majority to pass, reducing the need for DAO members to track and vote on every proposal to meet the 50% quorum, which is difficult in large or active DAOs. However, boosting may degrade the voting system’s ability to reflect all members’ opinions and could even be maliciously exploited (Patka, 2022).

To evaluate whether HC was needed, we first consider the motivation for filtering and fast-tracking proposals. This is required in two scenarios: when the DAO is large and requires many members to vote for a quorum, and when there are too many proposals to consider in a short time, making it difficult for users to consider them all.

Regarding the first case, we identified 12 DAOs with more than 20 members that potentially could benefit from an agile voting mechanism. Similarly, concerning the volume of proposals, we analyzed the number of proposals created in the last 15 days and found 10 organizations with peaks of more than 15 open proposals. Among them, four DAOs had peaks exceeding 30 proposals (shown in Fig. 3), with dxDAO and Genesis Alpha experiencing peaks of up to 60 and 40 proposals, respectively. The data confirms that the filtering and fast-tracking mechanism was needed in some DAOs, particularly in the larger or most active ones—the kinds of organizations HC aimed for.

Figure 3: Number of proposals created in the past 15 days for Genesis Alpha, Kyber DAO, dOrg, and dxDAO.

To evaluate whether HC allowed operation with limited participation, we examined participation rates and proposal approval. According to Table 1, the percentage of proposals approved across all active DAOs is usually very high (only in three of them is it below 50%), which denotes successful operation. Regarding the voting participation, analyzing our 23 organizations, around 65% of members did not vote on any proposal, and proposals averaged votes from only 8% of DAO members. This low participation, which is common in online communities (Malinen, 2015), seems to suggest that HC succeeded in its aim to enable participation with minimal collective attention. Looking at the two most active organizations, dOrg and dxDAO, their average participation per proposal was 11% and 0.8%, respectively. dOrg, a medium-sized cooperative with 34 members, and dxDAO, a large organization with 575 members, both were managed successfully with low participation, indicating HC’s effectiveness in operating DAOs with minimal engagement.

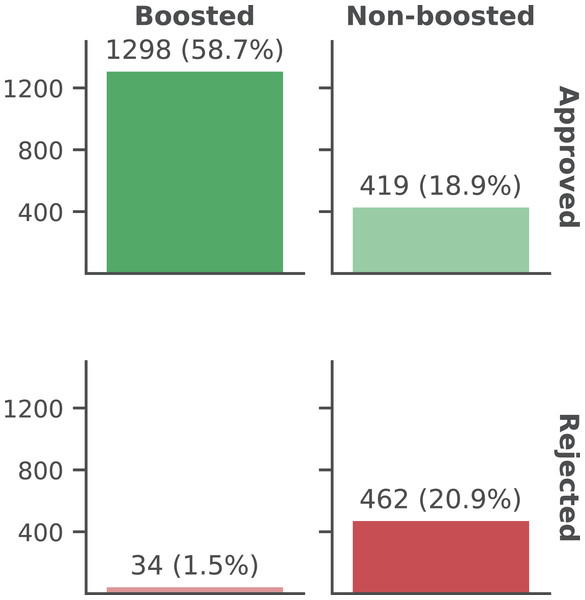

To evaluate the prediction capacity of the staking mechanism, Fig. 4 categorizes proposals by their prediction (boosted or not) and final status (accepted or rejected). According to this figure, which can be read as a confusion matrix, the boosting mechanism was precise, recognizing 97% of relevant proposals. Boosting also had a high sensitivity, as it correctly identified 76% of all approved proposals (boosted or not). However, 48% of non-boosted proposals were still approved, indicating that non-boosting didn’t always mean irrelevance. In these cases, the boosting mechanism failed to adequately identify proposals that were of interest to the DAO and required greater community participation in order to approve the proposals.

Figure 4: Number of proposals of each type closed before June 2021.

For non-boosted proposals that were rejected, 80% were rejected by a relative majority, not due to insufficient quorum, which clearly indicates that those proposals were against the community interest. However, compared to a study that used data until 2020 (Faqir-Rhazoui, Arroyo & Hassan, 2021b), overall accuracy decreased. While boosting precision improved, non-boosting no longer reliably indicated rejection. This seems to indicate that the functioning of the HC was affected by the decline experienced by DAOstack and its community from that period onward.

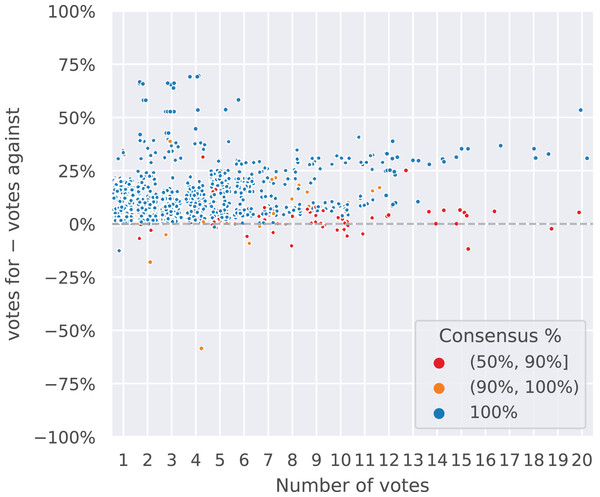

Figure 5 shows the votes cast in boosted proposals and their outcome3 . The outcome shows the result in terms of the total voting power of the DAO, ranging from 100% if the entire DAO VP had voted in favor and −100% if it had voted against. The plot shows that most proposals were approved, as they are above the 0% line, but more interestingly, that most were approved with few votes. Furthermore, the color represents the degree of consensus of the votes cast, expressed as:

Figure 5: Relationship between the number of votes and the outcome in boosted proposals.

100% means that all the votes cast were for the proposal, and −100% means that all the votes cast were against. The color of each dot varies depending on the degree of consensus.The blue color, which represents a perfect consensus, dominates the plot, which indicates that most of the decisions were unopposed. Although the color red is very rare overall, it appears more frequently in decisions that attracted a larger number of votes, indicating greater discrepancies surrounding those decisions. According to these observations, it is possible to conclude that boosting was mostly effective and behaved as expected by its creators.

Finally, we assess whether staking operated as an independent mechanism. Staking was designed as an open system where a network of predictors, driven by short-term economic motivations, would facilitate decision-making in a DAO without necessarily being members (Field, 2018). Data reveals that only 34% of proposals had no stakes from inside members, indicating they were staked by an independent network of predictors. On the contrary, self-staking was frequent, with 83% of all the stakes being made by DAO members supporting their own DAOs’ proposals. Furthermore, nearly one-third of proposals received stakes from their creators.

Thus, DAOstack failed to sustain an independent network of predictors, as staking was mostly done by DAO members interested in fast-tracking their proposals. It seems that the economic incentive was insufficient to motivate outsiders to track and bet on proposals. Although the evaluation of HC revealed that it was useful to DAOs and allowed them to operate successfully with low participation, without an independent network of stakers, HC loses its purpose, as it requires DAO members to stake their own proposals. As a result, staking becomes a mechanism that facilitates wealthier DAO members to fast-track their proposals, contrary to the creators’ intentions. This highlights the challenges of designing a socio-technical system to behave as expected.

Discussion

The results presented reveal several patterns that help situate DAOstack within the broader landscape of online peer production and decentralized governance systems.

DAOstack and peer production communities

The relatively low number of deployed organizations and active DAOs on DAOstack was particularly modest compared to contemporary platforms such as Aragon and DAOhaus. This limited adoption reflects the well-known challenges faced in implementing and scaling traditional software platforms: the difficulty of building initial momentum and achieving sustained usage over time.

DAO abandonment was common, with fewer than 40% lasting more than a year, and most exhibiting a short lifespan. These figures mirror patterns observed in online collaborative spaces such as wikis and open-source communities, where short-term and failed projects are also frequent. This phenomenon is not exclusive to DAOstack, nor even to DAOs themselves, and it points to structural issues affecting peer-production environments, regardless of whether they are blockchain-based.

DAOstack’s challenges suggest that, even within a technologically advanced decentralized platform, success still depends on adoption dynamics, effective integration, and sustained long-term engagement, similar to Web2 platforms. This reinforces the notion that collective engagement remains a critical bottleneck in scaling decentralized projects and is a challenge that cannot be addressed solely through technical innovation.

Power, participation, and the iron law of oligarchy

Power in DAOstack was formally earned through active engagement (via the REP system), and non-transferability was meant to limit wealth-based influence. However, despite this design, large DAOs tended to exhibit more concentrated power structures. This finding echoes prior work identifying similar concentrations of influence in both blockchain and non-blockchain communities.

DAOstack thus appears to conform to the “iron law of oligarchy” (Shaw & Hill, 2014), whereby systems that begin as democratic gradually evolve toward control by a few. Comparable patterns have been observed more broadly in DAOs (Peña-Calvin et al., 2024a) and in projects like Wikipedia (Rijshouwer, Uitermark & De Koster, 2023), where long-term contributors accumulate disproportionate influence while newcomers face integration challenges. In this respect, DAOs also tend to power concentration, a dynamic that characterizes many peer-production environments, but it undermines the decentralized governance intended by DAOs. DAOstack’s design constraints, such as the non-transferability of REP, were insufficient to prevent oligarchic drift. This prompts questions about the extent to which technological solutions alone can counteract sociological tendencies toward power concentration.

Problems in the holographic consensus mechanism

HC was conceived to solve the inherent tension between scalability and inclusion in decentralized governance. In particular, it aimed to sustain governance with low participation levels but preserving representativeness in decision-making. As we have seen, HC appeared to function as intended: proposals were routinely approved with low participation, and boosted proposals generally aligned with the community’s final decisions. However, we have seen that the prediction market underpinning HC failed to attract a truly independent staking network, as most stakes originated from DAO members and even from their own creators. Without the independent network of signalers, the system becomes self-referential, as proposals are boosted not because they are deemed relevant by observers, but because their authors wish to see them approved.

The decline in HC’s predictive accuracy after 2020, coinciding with the platform’s downturn, further illustrates how the health of a socio-technical system and the health of its communities are usually linked. When communities fade, governance tools weaken and break down in subtle but critical ways.

Limitations of the analysis

Our analysis presents several methodological limitations that constrain its ability to fully capture the complexity of DAOstack’s governance dynamics. First, the analysis relies exclusively on blockchain records and excludes informal coordination channels or other sources. It introduces an observational bias with respect to actual social interactions. Second, no systematic cross-platform quantitative analysis considering platforms such as DAOhaus or Aragon was performed, making it difficult to generalize the findings. Finally, the metrics used to assess participation and governance inequality serve as proxies that quantify observable manifestations. However, they do not capture alternative forms of engagement or influence, and may diverge from users’ subjective perceptions and lived experiences.

Qualitative insights from DAOstack participants

As a complement to the quantitative study of DAOstack, we performed a qualitative study by interviewing DAOstack members to better understand your vision of what a DAO is in DAOstack and your experience with the voting system. We aimed to investigate potential discrepancies between theoretical ideas or preconceived notions and actual practices.

Methodological note

The methodology for this qualitative study involved conducting semi-structured interviews with six key informants identified through snowball sampling. This qualitative method was employed to grasp political perspectives and socio-technical imaginaries (Jasanoff & Kim, 2015) of DAOStack’s participants, in line with other works (Semenzin, Rozas & Hassan, 2022). The aim was to understand in depth how technology-mediated social interactions worked in practice, in the context of DAOstack DAOs. These interviews, each lasting approximately 1 h, took place between September and November 2021 and focused on participants’ involvement with DAOStack, their internal experiences, and personal perceptions of the ecosystem.

We obtained informed consent from all participants involved in the interviews. Recruitment was conducted through the Discord platform, where the social researcher posted a message describing the study and inviting interested participants to contact the researcher who conducted the interviews. Interested participants contacted her directly and voluntarily. Once the interview time was arranged, verbal informed consent was obtained at the beginning of each session, and participants were reminded that their participation was voluntary, confidential, and could be withdrawn at any time. This verbal confirmation is documented in the interview questionnaire and the transcripts, and no personally identifying information was recorded. We provide the aforementioned recruitment message and the interview questionnaire as supporting material.

Furthermore, ethical oversight for this study was ensured by the European Research Council (ERC-EMN-759207-005), which funded the larger research project encompassing this study, through the appointment of an Independent Ethics Advisor. This advisor validated the ethical adequacy of the project’s social research protocols and data collection practices and provided written authorization for them.

The participants, shown in Table 2, are predominantly male (five men, one woman) with an average age of 40 (ranging from 25 to 55), and represented diverse national backgrounds, including Brazil, Venezuela, Australia, Israel, and Slovenia. They shared a high level of educational attainment, particularly in fields like computer science and finance, with additional backgrounds in psychology and anthropology. Notably, one participant had prior political experience in governance, while three self-identified as activists. All participants expressed a shared interest in cryptocurrencies, which informed their engagement with DAOStack. The key informants were involved in various DAOs within DAOstack, with all six having experience in Genesis Alpha DAO and at least one other DAO on DAOstack, as Table 2 shows. This distribution reflects a diverse range of experiences across multiple DAOstack-based projects, highlighting the varied applications and reach of the platform within the participant group.

| ID | Gender | Age | DAOs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Informant 1 | M | 25 | Genesis, dOrg, Fest DAO |

| Informant 2 | M | 47 | Genesis, dxDAO, xDXdao |

| Informant 3 | M | 38 | Genesis, dxDAO, Prime DAO, CENNXnet, Fest DAO |

| Informant 4 | M | 34 | Genesis, CENNXnet |

| Informant 5 | F | 42 | Genesis, PrimeDAO |

| Informant 6 | M | 55 | Genesis, PrimeDAO |

The interviews were manually transcribed and analyzed to identify recurring themes and insights. All of the participants’ names and identifiable private data have been removed to ensure their anonymity. The sample size consists of six interviewees following a qualitative, interpretive methodology that prioritizes depth over breadth. In line with established traditions in digital ethnography and qualitative inquiry (Geertz, 1973; Hine, 2020), the aim is not to generalize findings statistically but to generate rich, context-sensitive insights into the lived experiences, values, and practices shaping DAO participation. All participants were purposely selected based on their central roles in governance, coordination, and engagement within their respective DAOs. As core users and decision-makers, their perspectives offer privileged access to the socio-technical imaginaries and organizational dynamics at play. Moreover, in decentralized ecosystems where anonymity, fluid identities, and fluctuating participation are common, such an in-depth approach allows for a nuanced understanding that broader sampling might overlook. The findings aim to offer theoretical generalizability and transferable insights relevant to the study of emerging forms of digital governance and collective action.

Community and participation in DAOstack

Although all participants initially claimed that anyone could join a DAO, as illustrated in this interview excerpt–“DAOs allow people of all kinds to join. Naturally, at this stage, people are those who are curious about technology” (Informant 3)–the interviews revealed certain basic requirements for participation. These included technical skills to understand the platform and to contribute to its development, which was considered especially relevant as participation in DAOstack is often determined by the technical “merit” a member contributes. Participation in a DAO often required advanced technical knowledge, specific socioeconomic conditions, such as the possibility to invest in tokens, and an alignment with the values tied to the DAO, which, according to participants, are primarily financial: “Every DAO is financial by definition” (Informant 4). Additionally, Informant 1 described the existence of an onboarding process which involves submitting a curriculum vitae, participating in interviews, and then being granted user access–a process similar to traditional corporate hiring practices. Another essential factor for being granted access to DAOStack, mentioned by key informants, was having an interest in the crypto world (“my ideology is crypto”–Informant 3), or as one participant described it, “being a daoist” (Informant 2), an idea that subtends the existence and centrality of a specific philosophy or ‘crypto ethics’ behind participation in DAOStack, in line with literature on hacker ethics (Levy, 1984).

More importantly, three participants recognized that to gain access to some DAOStack DAOs, especially the biggest ones, such as GenesisAlpha or PrimeDAO, financial means were required to invest in tokens. As one interviewee noted, “it’s a rich men’s game” (Informant 2). Another interviewee stated:

DAOs are hierarchical: it’s about coordination technology. Some of them have democratic principles incorporated, but not every DAO will be naturally horizontal. As in companies, people get fired. It’s just natural.

However, some participants contrasted this idea, highlighting how the financial dimension of DAOs was not in line with the communitarian and peer-to-peer principles that often take place in such digital environments:

If you pay people to do stuff, that’s not a community. A community is supportive and helpful, it’s full of love. DAOs are just financial.

This presence and recognition of hierarchies within the DAOstack ecosystem led some participants to discuss the issue of power imbalances, especially in the context of reputation and voting. This is tackled in the next subsection, where we delve into their voting experience.

Voting experience

When discussing their experience with voting, all interviewees had experience with voting in DAOs and also with the HC governance mechanism, as described in ‘Evaluation of the holographic consensus voting system’. While some interviewees view DAOs as “perfect consensus machines”, most of them acknowledge that power imbalances emerge within these organizations. According to their feedback, only about 15–20% of participants typically voted in a DAO. This seemed to be partly due to token ownership, which, depending on the DAO, can be either purchased or earned through reputation:

Voting is reserved for those who hold tokens: the DAO operates on a reputation system based on participants’ activity and contributions. (Informant 1)

All informants recognized and explained that reputation and voting primarily depend on financial access to tokens. In this regard, they acknowledged that hierarchies developed within DAOs. According to four participants, that was just “natural”, and power concentrations did not necessarily represent a problem in terms of democracy or horizontality:

It’s a club where you pay a certain amount, but everyone will have fair starting conditions. (Informant 6)

On the other hand, two participants openly considered the voting process as problematic and non-democratic. Informant 5, for instance, pointed out the issue that decisions were mostly made by a small number of individuals, which led to the exclusion of certain members and limited voting due to the high cost of tokens. According to her:

There are popular users who hold more power. People who own “maker tokens” have more power. This is not a democracy. (…) Reputation is a good way to represent meritocracy, but wasn’t in DAOstack. Most of the DAOs today work as plutocracy. (Informant 5)

This idea of plutocracy, in contrast to democratic principles of DAOs, was further expanded by another interviewee, who explained the intrinsic relationship between DAOs and financial investors:

Most of the DAOs today work as plutocracies–because it depends on how money is allocated by investors. (Informant 3)

When asked about their experience with voting in DAOs, participants also recognized and narrated that most of the voting results depended on external conversations, taking place in online environments such as Discord, Telegram, WeChat, Snapshot, or online forums or blogs, such as Medium. These conversations revolved around arguing and debating pre-proposals before putting them to a vote, mostly to secure a positive result in voting. As exemplified by this interview excerpt, human interaction and persuasion were crucial to achieving a reputation based on voting:

What the software can do is really minimal. Human touch is required. If you don’t participate, your reputation goes away. So, when you make a proposal to increase your reputation, you need to ask people to vote for it. It can be sometimes a painful process. (Informant 2)

According to one interviewee, these dynamics of persuasion existed within DAOs in a similar way to those found in political environments and interactions. After asking who the users holding the most tokens are, Informant 4 shared:

People who really want to have more power and play politics. Often, they even ping users in private to have proposals voted on. (…) Too much politics and too many influential people that influence the votations. (sic) (Informant 4)

By recognizing the importance of these external interactions, Informant 1 also stated that this process would become too difficult to be reproduced at a larger scale and therefore not efficient. According to these perspectives, two participants stopped voting because “it was too expensive”, whereas two other participants stopped voting due to a lack of sufficient reputation since they had ceased participating in DAO activities.

Finally, regarding the Holographic Consensus, all interviewees reported using it and found it “cool”, “elegant”, or “innovative”, though too complex or underdeveloped to function effectively on a large scale. In this regard, HC was seen as interesting for “boosting” a proposal, filtering out poor proposals, or creating a quorum. However, the main challenges mentioned were its technical complexity, high cost, and occasional issues with the boosting function not working properly.

Key insights and limitations

Based on the interviews, we can identify several noteworthy aspects of how DAOstack was perceived by its users:

Conditional access: Although DAOstack theoretically allowed open participation, in practice it functioned as a selective community, closer to a technological and financial elite than to a truly horizontal and open space. This was due to economic and technological barriers, as well as a certain alignment of values.

Clashing visions: While some DAO members described DAOs as genuine communities, others viewed them as financial environments oriented toward efficiency, where hierarchical structures were to be expected.

Limitations of the holographic consensus: Although praised as innovative, the HC system was perceived as complex, costly, and at times dysfunctional. Its design failed to prevent dependence on dominant participants. Moreover, informal networks of influence played a central role in garnering proposal support, fostering practices comparable to those in traditional political environments.

The interviews reveal that although DAOstack provided a novel infrastructure for decentralized governance, there was a significant gap between its original ideals and actual usage, as well as between the differing visions of its users. As with any socio-technical system, actors experimented with, negotiated, and reinterpreted the platform’s mechanisms through their everyday practice.

It is important to acknowledge that the qualitative study presents several limitations due to its methodological choices. In particular, the sample does not capture the full diversity of user profiles and experiences within DAOstack, as it is biased toward active and engaged participants. In addition, interviews were conducted after DAOstack’s decline, which may have shaped the narratives through retrospective justification or critical reflection. Furthermore, the analysis was not complemented by digital ethnography, which limited our ability to explore the relationship between discourse and practice or to distinguish between normative ideals and actual behaviors. These constraints should be considered when interpreting the main findings and assessing their broader significance.

Implications for DAO platform designers

DAOstack’s collapse was not a single-point failure but the cumulative effect of high on-chain costs, opaque token economics, fragile front-end dependencies, thin social onboarding, and a prediction-market layer that failed to attract independent stakers. These factors spanned a vertical stack of weaknesses, from low-level technical immaturity to high-level group usability barriers, that ultimately undermined the entire project. Addressing those pain points suggests a blueprint for sturdier DAO tooling.

Key recommendations

Below, we gather a summary of recommendations to DAO platform designers, grouped in categories. We hope this helps current and future platform generations to learn from the mistakes of their forebears:

Governance and voting system

Future DAO governance designs must prioritize optional complexity with progressive disclosure, ensuring focus and avoiding procedural overhead for newcomers. More complex voting approaches could be used only after a community crosses critical thresholds in size or proposal volume. We observed how DAOstack needed boosting in just four DAOs that, on some occasions, had a large amount of open proposals, but more simplification could have been beneficial for the rest. Simultaneously, it is critical to mitigate the impact of large token holders, using voting paradigms such as quadratic (Benhaim, Hemenway Falk & Tsoukalas, 2024) or conviction voting (Emmett, 2019). This could not only help to mitigate plutocracy found in large DAOs and perceived by interviewees (“rich-men’s game”), but also could help to enhance participation, as these voting approaches promote more equitable governance.

Incentive and economic layer

To address the independence problem of HC, where 83% of stakes were self-stakes (from people within), future platforms relying on stakers should reward more effectively outside stakers (e.g., fee rebates, inflationary payouts) so that prediction markets could become significantly more independent. Additionally, governance systems must foster dynamic participation making reputation non-transferable but time-decaying, avoiding frozen allocations that may lock voting power in DAOs where the implication of some powerful members decreases over time. Finally, community-exit mechanisms are vital to mitigate stagnation; they enable dissenting and inactive participants to withdraw their staked assets or claim a proportionate share of the treasury, thereby mitigating the risk of capital lock-up in the event of DAO inactivity. This approach, implemented in platforms as DAOhaus under the name of “rage-quit”, could help to mitigate observed stagnation, as the remaining contributors can align more cogesively around the project’s ongoing goals.

Onboarding, identity and platform interaction

To reduce friction for new members, platforms should simplify onboarding and key interaction flows by providing guided wallet setup, accessibility, and mock voting playgrounds to reduce cognitive load for newcomers. A total of 65% of members never cast a vote in DAOStack, and challenges related to platform literacy and the use of the sophisticated voting system surely were a contributing factor. Furthermore, to increase the contributor pool, platforms must foster inclusion and participation by implementing participation ladders through visible, simple contributions, empowering users to gradually earn visibility and reputation without significant token buy-in and opening the “technical-merit gate” to include skills beyond programming or protocol-level expertise. At last, to ensure adaptable and fair governance, DAOs should leverage Identity complements that integrate verifiable identity tools such as Gitcoin Passport, BrightID, or Sismo ZK so they can switch between token-weight and “one-human-one-vote” voting schemas per proposal. This adaptability addresses representational inequities while preserving systemic legitimacy.

Monitoring community health

DAOs need robust, automated systems to detect both power concentration and dangerous innactivty. Platforms should embed on-chain analytics and health dashboards directly into DAO front-ends, featuring live statistics such as the Gini, Nakamoto Coefficient, and voter-turnout statistics. Default transparency nudges better governance and helps communities detect power concentration early. DAOStack suffered very low values without early warning tools. This proactive monitoring should be paired with dormancy triggers; DAOs showing low activity metrics, such as less than three voters or no proposals in 90 days, should be automatically flagged, triggering offboarding, “sunset”, or transformation workflows that preserve treasury integrity and platform efficiency.

Technical infrastructure

Platforms must incorporate gas-free voting and interaction mechanisms to eliminate the cost deterrent. Snapshot-style off-chain signing helps to neutralize the “pay-to-vote” deterrent (Saldivar et al., 2023), an element that surely contributed to the average turnout of only 8% of members in DAOstack DAOs. In general, platforms aiming to incentivize participation should adopt gas-free interaction mechanisms to ensure that transaction costs do not become a barrier to entry. Moreover, to secure operational longevity and true decentralization, platforms must rely on Redundant open-source front-ends. DAOstack died after its only web user interface went offline in 2022, forcing dxDAO to deploy its own front-end. This single point of failure emphasizes the necessity of decentralized hosting solutions like InterPlanetary File System and Ethereum Name System to prevent service compromise.

Several of these aspects have been incorporated by subsequent DAO platforms, particularly those that have demonstrated greater adaptability or sustainability over time. This shows that the costs of technological pioneering can be prohibitively high, as early-stage tools often bear the burden of conceptual, infrastructural, and usage-related barriers, both individual and collective, which ultimately may lead to their collapse.

Holographic consensus: an evolutionary dead-end?

Although HC is no longer a widely adopted voting system, it could still prove valuable in sufficiently large ecosystems, particularly those capable of sustaining an independent market for predictors, and for DAOs where attention allocation in key proposals is a challenge.

Nevertheless, its core mechanisms anticipated governance patterns now standard in DAO tooling. Its “boosting” process, in which economic signaling elevated proposals without requiring mass attention, foreshadowed Snapshot’s off-chain voting combined with Safe-based execution, as well as “optimistic governance” flows used in platforms like StarkNet and Arbitrum, where proposals pass by default unless stakers veto them (Donno, 2022). While HC relied on burning GEN tokens to filter signal from noise, modern systems externalize that cost to stakers or relayers through veto windows or delayed execution.

Besides, HC’s use of an internal prediction market to “boost” proposals was one of the earliest real-world applications of futarchy, i.e., governance guided by prediction market signals (Hanson, 2013). This boosting mechanism anticipated a broader interest in using economic signals to steer governance and determine proposal prioritization. This has been applied to prioritize attention and execution in systems like GnosisDAO’s conditional tokens (MetaLamp, 2024) and the external use of prediction-market platforms like Polymarket to forecast DAO proposal outcomes (Buterin, 2024). DAOstack, therefore, pioneered a scalable, attention-efficient governance logic that was a precursor to mechanisms still being explored and adopted.

Concluding remarks

This study provides the first postmortem analysis of a first-generation DAO platform, DAOstack, spanning its entire 7-year lifespan. Combining quantitative and qualitative methods, we offer empirical examination of the HC governance model. The genesis and collapse of DAOstack serves as a critical case study, yielding design recommendations for the next generations of DAO platforms.

While DAOstack’s trajectory may echo other startups that vanish due to insufficient user growth, it offers a unique perspective on the first-generation DAO ecosystem. This case allows us to explore DAOs as blockchain tools and their role in computer-supported cooperative work. DAO platforms, like other blockchain tools, face challenges such as usability issues, Ethereum’s scalability problems, and cross-network interoperability (Tan et al., 2023). Although blockchain technology excels in secure decentralized voting, open accounting, and treasury management, it struggles with user experience, social interaction, and organization management. Despite DAOstack’s awareness and efforts to address these issues, they significantly contributed to the platform’s downfall.

These blockchain challenges may partly explain the short lifespan of many DAOs. Additionally, peer production communities face difficulties in managing projects collectively, similar to wikis or open-source projects (Ortega, Gonzalez-Barahona & Robles, 2008; Gasparini et al., 2020; Tenorio-Fornés, Arroyo & Hassan, 2022). Recent studies (Goldberg & Schär, 2024; Peña-Calvin et al., 2024a) show that DAOs also exhibit low participation rates and high power concentration, highlighting the complex dynamics inherent in online peer-managed projects. In our work, we have seen that this trend also manifested in DAOstack. As DAOs are a novel type of organization, further research is needed to understand these traits and their impact on sustainability.

In terms of governance, DAOstack’s voting system was designed for large-scale collaboration, aiming to enable DAOs to endorse key proposals with low participation, crucial for large organizations or with large numbers of open proposals. Although the system apparently worked well, allowing the DAOs to function and approve proposals, most DAOstack DAOs did not experience these scenarios. The system theoretically relied on an external network driven by economic incentives to identify compelling proposals, but this network was insufficient, requiring DAO members’ involvement. This allowed wealthier members to increase their control. It may have been overly optimistic to assume external individuals would show more interest than members. This aligns with literature, which shows participation in peer production communities is typically driven by intrinsic motivations rather than external incentives (Xu & Li, 2015). In fact, despite the designers’ intention to create an efficient voting system integrating meritocracy and a financial component to enable large-scale operability, interviews revealed that some users experienced problems with the reputation system, the cost of votes, or the difficult need to mobilize votes, especially from influential members, in order to move proposals forward.

Our research reinforces the conclusions of other studies that highlight the significant challenge in designing a decentralized voting system combining, on one hand, communal benefits and shared goals, and the practical need for checks and balances to manage power and align the interests of different stakeholders (Alawadi et al., 2024). The challenge is even greater because this voting system has to adapt to organizations of varying sizes and purposes and accommodate decision-making for a diverse range of resolutions (e.g., operational, technical, strategic). The system must be user-friendly and prevent negative repercussions, with blockchain integration adding complexity. While there are significant efforts to understand DAO decision-making (Spychiger, Lustenberger & Küng, 2025), there is a need to evaluate how useful they are for the communities they serve.

From a more general perspective, the interviews conducted have shown that many DAO members consider DAOs to be hierarchical or plutocratic coordination tools, where finances play an important role. These perceptions place them far from the ideals of decentralized governance that they originally pursued. This lack of decentralization and democracy has also been observed in users of other DAOs and other voting systems (Gilson & Bouraga, 2024) and appears to be a recurrent issue in purportedly decentralized blockchain governance (Schädler, Lustenberger & Spychiger, 2023).

The DAOstack case reveals that the emergence of DAOs as a novel organizational structure brings a range of challenges. DAO users should recognize that decentralized governance, while promising, may not always outweigh the costs and risks (Halaburda & Mueller-Bloch, 2019) and does not guarantee decentralization in practice (Goldberg & Schär, 2024). Furthermore, DAO platform designers should not rely solely on Computer Science knowledge to address complex social organization challenges. Instead, a multidisciplinary and experimental approach is required, bringing together technical knowledge with UX experiments, social research, and inputs from Organizational Science (Tan et al., 2023). DAOstack exemplifies that failure often results from interacting factors across multiple layers, from low-level technical frictions to higher-order coordination challenges, underscoring the need for holistic design perspectives. In this sense, the DAO fragility schema outlined in this article, along with the recommendations, aims to contribute in that direction by addressing such diverse levels, including technological components, individual engagement, and collective dynamics. By adopting an integrated lens, DAOs can move beyond their current crypto-technological niche and more effectively support diverse communities in self-organizing around shared goals.

Supplemental Information

Interview script.

Script of the semi-structured interviews used in the qualitative part of the paper, including the informed consent. Interviews were carried out in English language.

The last mainnet block explored was 17161692, and the last xDai block was 27714033.

GEN is distinct from the aforementioned token REP, which does not act as cryptocurrency, being non-transferable