A comprehensive review of Android malware: trends, behaviors, taxonomies, and future direction

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Michele Pasqua

- Subject Areas

- Computer Architecture, Computer Education, Data Mining and Machine Learning, Mobile and Ubiquitous Computing, Security and Privacy

- Keywords

- Fileless, File-based Android malware, Attack vector, Hybridization, Obfuscation, Polymorphism

- Copyright

- © 2026 Chimeleze et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2026. A comprehensive review of Android malware: trends, behaviors, taxonomies, and future direction. PeerJ Computer Science 12:e3312 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3312

Abstract

The increasing prevalence of malicious applications targeting the Android operating system has intensified security challenges in recent years. As Android’s popularity continues to grow, it not only attracts users but also becomes a prime target for cybercriminals, underscoring the critical need for robust defenses against advanced Android malware. This survey manuscript is intended for a multidisciplinary field to evaluate and analyse the Android malware trend, behaviors, taxonomies, and future direction. This survey presents a comprehensive review of study trends, examines Android malware behaviors over time, and analyzes their patterns across platforms, families, and regions. Additionally, it evaluates existing Android malware taxonomies and identifies key gaps. To address these gaps, we propose an enhanced taxonomy tailored to advanced Android malware. The study concludes with actionable recommendations for future research, aimed at assisting users and industry professionals in mitigating the evolving risks posed by sophisticated Android malware attacks.

Introduction

The operating system (OS), developed by Google is the most widely used mobile platform globally, powering billions of smartphones, tablets, wearable devices, and smart TVs. Its open-source nature, flexibility, and extensive application ecosystem (ES) have made it the preferred choice for both consumers and developers. As of 2025, Android holds over 70% of the global mobile operating system market share, underscoring its dominant presence in the digital ecosystem.

The rapid evolution of cybersecurity (CS) threats presents a significant global challenge to individuals, organizations, and governments. With the proliferation of digital technologies and the increasing dependency on interconnected systems, Android attacks have become more sophisticated and diverse. This growth in attack complexity is fuelled by the platform’s popularity and openness, which, while beneficial for innovation, also exposes it to a wide range of security threats.

Android malware (AM); malicious software specifically targeting Android devices—has emerged as one of the most pressing threats in the mobile landscape. It encompasses a broad spectrum of attack vectors, including spyware (SW), ransomware (RW), banking trojans (BT), adware (AW), and remote access tools (RATs). These malware types are often distributed through deceptive apps, third-party marketplaces, phishing campaigns, or infected websites.

The consequences of Android malware (AM) can be severe. Real-world incidents underscore the magnitude of the threat: for example, the “Joker” malware family has infected thousands of apps on the Google Play Store, silently subscribing users to premium services without consent. Similarly, the “Anatsa” banking trojan has targeted financial apps across Europe and the U.S., stealing login credentials and performing unauthorized transactions. According to a 2024 report by Kaspersky (2025), mobile malware attacks increased by over 35% compared to the previous year, with Android being the most affected platform.

These growing risks highlight the urgent need for comprehensive threat analysis, malware classification, and effective defense mechanisms tailored to the Android ecosystem. This review aims to explore the current landscape of Android malware, analyzing existing taxonomies, detection techniques, and research trends to provide a consolidated view of the challenges and ongoing efforts in the field. This survey manuscript is intended for a multidisciplinary field to evaluate and analyse the Android malware trend, behaviors, taxonomies, and future direction. In this survey, we evaluate and analyse the following research questions (RQs):

RQ1: What is the study trend over time?

RQ2: What are the Android malware behaviors over time?

RQ3: What are the malware families based on platforms and infected regions?

RQ4: What are the limitations of the existing Android taxonomy (AT)?

RQ5: What are the key classifications to introduce to enhance the existing Android taxonomy?

To address these research gaps based on the respective research questions (RQs), this research contributes to the following:

-

(i)

Thorough examination of the study trends based on publication, distribution among the key research publishers over a specific timeline.

-

(ii)

Thorough evaluation and examination of AM behaviour over the time.

-

(iii)

The popular advanced Android mobile malware based on variant features, platform and region is evaluated and analyzed.

-

(iv)

An in-depth evaluation and investigation of the existing Android malware taxonomy.

-

(v)

A new, enhanced Android mobile malware taxonomy is introduced based on (i)–(iii).

We believe this work offers significant value to researchers and practitioners in software engineering and CS, particularly those specializing in taxonomy, malware classification, and mitigation. It also serves as a resource for policymakers, software providers, and other stakeholders aiming to enhance software security, mitigate cyberattack risks, and make informed decisions regarding software development, procurement, and risk management.

The rest of this article is structured as follows: ‘Background and Related Works’ discusses the background and related works, while ‘Review Methodology’ describes the research methodology proposed in this study. ‘Results’ addresses the research questions and presents the corresponding results. ‘Threat to Validity’ discusses potential threats to the validity of the study. Finally, ‘Conclusions’ concludes the article and proposes future research directions.

Background and related works

In this section, we discuss and examine the background study and related works. This section is further divided into two subsections: In the first subsection, we explore Android malware threats and justify the need for reviewing a robust Android malware classification system, while in the second subsection, we review related works, focusing on their respective Android malware classification systems and taxonomies.

Background study

In this subsection, we briefly discuss and examine various Android malware threats and need to embark on this study.

Advanced persistent threats (APTs) have emerged as a critical concern in the Android mobile platform (AMP), employing sophisticated techniques to evade detection and execute malicious actions (Nadler, Aminov & Shabtai, 2019; Faircloth, 2017; Li & Liao, 2022; Hostiadi & Ahmad, 2022; Rahman & Tomar, 2020; Putra, Hostiadi & Ahmad, 2022; Kasim, 2021). BT, designed to steal sensitive financial information, have been studied extensively (Kar, Panigrahi & Sundararajan, 2016; McWhirter et al., 2018; Xie, Li & Sun, 2022; Halgamuge, 2022). Techniques by Rahman & Tomar (2020) bio-statistical feature-based detection and Hostiadi & Ahmad (2022), the hybrid detection method based on similarity and correlation, improve performance in identifying coordinated attacks.

Remote Access Tools (RATs) enable unauthorized control and data exfiltration from compromised devices. Ullah et al. (2018) proposed a multi-layered detection approach, while Steadman & Scott-Hayward (2021) introduced DNSXP, a programmable data plane solution to enhance detection. Ransomware, an evolving threat, has transitioned from simple locker variants to advanced encryption-based attacks. Research by Savage, Coogan & Lau (2015), Kim et al. (2022), and Oz, De Donna & Di Pietro (2022) emphasizes cryptographic detection and mitigation techniques, as well as the importance of organizational measures.

Advertising click fraud (ACF) manipulates pay-per-click systems, generating fraudulent revenue. Techniques like network monitoring by Andress (2014) and biostatistical detection by Rahman & Tomar (2020) enhance fraud detection. Brewer (2014) evaluates and discusses detection techniques for minimizing the impact of advanced persistent threats (APTs) that leverage the performance of click fraud, emphasizing the importance of robust, timely detection. Cryptomining malware (CM) exploits devices for unauthorized cryptocurrency mining. Mani et al. (2020), and Caprolu et al. (2021) propose advanced analytics and deep learning-based approaches for robust detection and prevention. Kaspersky (2022a), reviewed the IP spoofing operation and the defense techniques to be explored against Android attacks.

Data exfiltration (DE), a huge Android mobile threat, involves the unauthorized transfer of data from Android devices (Alghamdi & Bellaiche, 2023; Dong, Liu & Wu, 2022; Xing, Sun & Deng, 2022; Anonymous, 2013; Salerno, Sanzgiri & Upadhyaya, 2011; D’Orazio et al., 2017; Qamar, Karim & Chang, 2019; Bojjagani, Brabin & Rao, 2020; Verkijika, 2019). The DNS technique over HTTPS (DoH) is leveraged to encrypt data exfiltration activities, complicating detection efforts (Yoo & Cho, 2022; Bhardwaj et al., 2021; Tharayil et al., 2020; Patel, Han & Jain, 2016; Wang et al., 2019a; Rustamov et al., 2020; Patil, Bhilare & Kanhangad, 2016; Su, Chuah & Tan, 2012; Tharayil et al., 2020; Sharma & Rattan, 2021; Guido et al., 2013; Homayoun et al., 2019). Zhan et al. (2022), and Steadman & Scott-Hayward (2021), proposed a defense technique that covers channels and the defense system. Furthermore, Ullah et al. (2018), review the external attack vectors used in data exfiltration and the defense measures to mitigate these Android threats.

SQL injection is the most prevalent Android attack vector; the malicious SQL code is used to manipulate databases (Makhdoom et al., 2019; Taneja, 2013; Junger et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2023; Thejas et al., 2021). Faircloth (2017), and Natarajan & Subramani (2012), explore various detection and defense techniques for SQL injection attacks, emphasizing the importance of web application defense. Goel & Jain (2018), and Taneja (2013), review the emergence of mobile and IoT devices and the introduction of new vulnerabilities and attack vectors.

Advanced persistent threats (APTs) and crypto-jacking are the core threats to Android mobile devices (Shang et al., 2020; Peris-Lopez & Martín, 2017; Gezer et al., 2019; Abualola et al., 2016; Malwarebytes, n.d; Help Net Security, 2022; Lian & Jhe, 2022; Zimba et al., 2018; Caprolu et al., 2021; Al-Turjman & Salama, 2021; Crussell, Stevens & Chen, 2014; Sadeghpour & Vlajic, 2021; Thejas et al., 2021; Richet, 2022; Chertov & Pavlov, 2013; Sisodia & Sisodia, 2022; Seals & Seals, 2019; McAfee, 2022; Cisco, 2022; Kaspersky, 2022b; Malwarebytes, 2022). The Android APT attacks explore ways to steal data or cause disruption (Huete Trujillo & Ruiz-Martínez, 2021; Corll et al., 2023; Niu et al., 2021; Singleton, Kiefer & Villadsen, 2025). Nadler, Aminov & Shabtai (2019), Cryptojacking hijacks Android device resources to mine cryptocurrencies. This new threat impacts Android mobile device performance and incurs a huge loss to Android mobile users.

Li & Liao (2022), proposed a new encryption technique to mitigate the rate of data theft and examine the dynamic interplay between attackers and defense techniques (Cohen & Herzog, 2020; Kaspersky, 2022d; Kaspersky, 2022e; Komornik, 2022; Belding, 2021; Cloudflare, 2022; Kaspersky, 2021; Meng et al., 2023; Hull, John & Arief, 2019; Kao, Hsiao & Tso, 2019; Symantec, 2015; Stubbs, 2019; Salehi et al., 2018; Wójcik, 2022; El Fiky, 2020; Abawajy, Darem & Alhashmi, 2021; Akram, Majid & Habib, 2021; Shafiq et al., 2020; Mahindru & Sangal, 2020; Hajisalem & Babaie, 2018; Taha & Malebary, 2021; Altaher, 2016; Liu, 2022; Yu et al., 2021; Gu et al., 2017; CrowdStrike, 2023). Hostiadi & Ahmad (2022), proposed a hybrid detection technique to mitigate bot group activities by analyzing network traffic flows using similarity and correlation approaches. Goel & Jain (2018), and Vishwanath (2016) examine the SQL injection APT for web applications, with various detection methods proposed, ranging from token graphs and SVM to ensemble classification approaches.

Zhao et al. (2020), examine the existing Android detection techniques and the threats with no robust detection system. Diba et al. (2018), review the core challenges for implementing comprehensive Android malware detection techniques given the resource constraints of Internet of Things (IoT) devices. Seals & Seals (2019), Kaspersky (2022c), and Mundo (2020), examine the prevalent mobile detection techniques based on their fragmentation defense limitations. Abdel-Basset et al. (2023) review the importance of robust detection technique implementation for the resource constraints of IoT devices.

Rashed & Suarez-Tangil (2021), and Alswaina & Elleithy (2020), review the existing detection technique’s reliance on static analysis or signature-based methods, bypassed by APT employing variant features. Qamar, Karim & Chang (2019), and Manzil & Naik (2023), examine the existing malware detection technique and propose the development of a detection framework that integrates machine learning with dynamic and behavioral analysis to provide real-time detection and adapt to the evolving Android threats. This review highlights the evolving nature of APT threats and underscores the necessity for innovative defense mechanisms.

Related works

In this subsection, we review the related works, focusing on their respective Android malware classification systems and taxonomies.

Thanh (2013), examine the existing Android malware families and their detection features known to the users and propose a detection technique. Grégio et al. (2015) review and evaluate the existing malware behavior taxonomy based on defense techniques. Sufatrio et al. (2015) review and evaluate the existing secured Android mechanisms and detection techniques, Jamil & Shah (2016), discuss and examine the advanced integration of machine learning (ML) with malware detection to analyze existing ML malware detection techniques.

Chouhan & Shah (2017) examine and classify malware types and malware detection techniques. Abdul Kadir, Stakhanova & Ghorbani (2018) review the existing financial malware, features, and limitations. Bakour, Ünver & Ghanem (2019), examine and analyze the gap between the detection systems and their real-world performance. In addition, Wang et al. (2019b), discuss and examine the feature construction for malware detection techniques. Qamar, Karim & Chang (2019), review and examine the existing mobile malware attack taxonomy and future research directions. Vishnoi et al. (2021), examine traditional and cloud-based malware detection techniques based on key differences, strengths, and limitations. Garg & Baliyan (2021), review and evaluate the Android malware detection techniques and the research gaps. Rashed & Suarez-Tangil (2021), analyze and evaluate the Android malware classification, strengths, and weaknesses. Berger, Hajaj & Dvir (2022), examine Android OS evasion attacks and evolving detection techniques.

Liu et al. (2024), and Manzil & Naik (2023), examine the existing ML-based malware detection and robust APT defense adaptations. Alswaina & Elleithy (2020), discuss and examine the existing Android malware family classification and future directions. Chattopadhyay, Sengupta & Pal (2024), examine the application for enhancing detection defense based on secret sharing. Chandola, Banerjee & Kumar (2009), discuss and review the detection techniques for anomalies based on the unusual patterns indicative of malware identification.

Tam et al. (2017) survey the evolution of Android malware and analysis techniques, categorizing them into static, dynamic, and hybrid approaches. They highlight how malware has become more complex and evasive, outpacing traditional detection methods. The study underscores the need for adaptive analysis tools to counter increasingly sophisticated threats. Afianian et al. (2019) focus on dynamic analysis evasion techniques used by malware, such as environment detection, behavior stalling, and trigger-based activation. These methods allow malware to avoid detection during analysis. The authors emphasize the need for stealthy and realistic analysis environments to counter these evasions. Sharma & Rattan (2025) provided a comprehensive characterization of Android malware and their families, focusing on behavioral patterns, propagation techniques, and classification methods to aid in more effective detection and analysis.

Review methodology

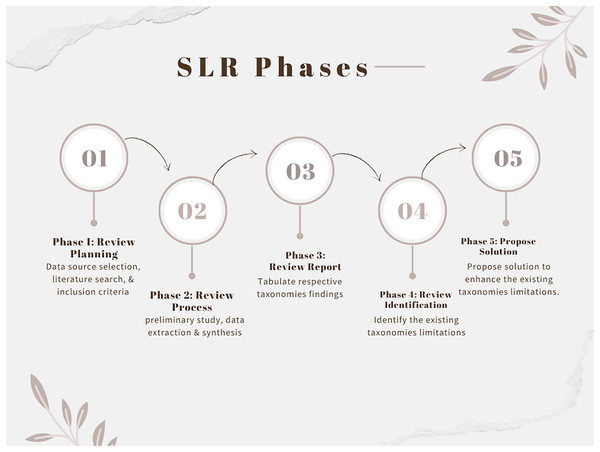

In this section, in order for we to review and evaluate the related study trends, Android malware behaviour over the time, popular advanced Android mobile malware based on variant features, platform and region is evaluated and analysed, existing Android malware taxonomy, and proposed enhanced Android malware taxonomy, we explore a systematic literature review (SLR). In this study, we used the PRISMA technique to review the relevant literature. Oz, De Donna & Di Pietro (2022), is used to find the most relevant literature as a taxonomy-based procedure. Sexton, Storlie & Neil (2015), PRISMA is explored as a review process due to the core characteristics of openness, precision, accessibility, and scope. In this article, we explore the methodology outlined in the literature to deliver an in-depth review of the available research.

Figure 1 depicts the three major phases of systematic literature review (SLR) processes: planning, conducting, and reporting the review. This process consists of determining the purpose of the study, defining the search technique and selection criteria, designing a quality assessment checklist determining the mechanism of data extraction, reporting, research gap identification, and propose solution. We strictly followed the guidelines and suggestions of Oz, De Donna & Di Pietro (2022), and Kadir, Stakhanova & Ghorbani (2018), to ensure the quality and completeness of this review. Table 1 depicts the various search strings we explored in this study, and this ensures a thorough search of the related relevant literature based on the study scope.

Figure 1: Systematic literature review phases.

| Search string |

|---|

| TITLE—ABS-KEY ((“Advanced Android malware* mitigation*’’ OR “Advanced Android malware * attack*’’ OR “Advanced Android malware * technique* OR “attack*” OR “Mobile ATT&CK” OR “Advanced Android malware * Taxonomy *” OR “Advanced Android malware * multi* detection*” OR “Advanced Android malware * machine learning*” OR “Advanced Android malware * anomaly detect*” OR “Advanced Android malware * taxonomy*” Advanced Android malware “APT* hidden Markov model*” OR “APT* anomalous behavior*”)) |

| TS = ((“Advanced Android malware T* mitigation*’’ OR “Advanced Android malware * attack*’’ OR “Advanced Android malware * technique* OR “attack*” OR “Advanced Android malware ATT&CK” OR “Advanced Android malware * Taxonomy *” OR “Advanced Android malware * multi* detection*” OR “Advanced Android malware * machine learning*” OR “ Android malware * anomaly detect*” OR “Advanced Android malware * taxonomy *” OR “Advanced Android malware * hidden Markov model*” OR “Advanced Android malware * anomalous behavior*”)) |

| ((“Advanced Android malware * mitigation*’’ OR “Advanced Android malware * attack*’’ OR “Advanced Android malware * technique* OR “ attack*” OR “Advanced Android malware ATT&CK” OR “Advanced Android malware * taxonomy*” OR “Advanced Android malware * multi* detection*” OR “Advanced Android malware * machine learning*” OR “Advanced Android malware * anomaly detect*” OR “Advanced Android malware * taxonomy *” OR “Advanced Android malware * hidden Markov model*” OR “Advanced Android malware * anomalous behavior*” OR “ hybrid and explainable AI in advanced mobile malware detection*”)) |

Table 2 depicts the review selection criteria, quality assessment, and data extraction framework.

| Criterion | Eligibility | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Literature type | Journals, conferences, certified websites, book chapters, and studies with relevant keywords | Full-text versions discussing advanced Android malware detection and Android security | Reports, magazines, uncertified websites, and publications other than journals, conferences, or book chapters |

| Language | English | All articles must be written in English | Any articles not written in English |

| Timeline | January 2018–2024 | Articles must have been published within this range (not earlier than January 2018 and not later than 2024) | Articles published before January 2018 or beyond 2024 |

| Solution-oriented | Offers one or more mitigations addressing research gaps | Articles must identify and propose solutions to at least one of the following: specific problems, gaps, or vulnerabilities | Articles that do not propose or evaluate any solution |

| Quality assessment procedures (Using: JBI critical appraisal tool) | Systematic evaluation of each study’s methodological quality, bias risk, and evidence strength, suitable for varied study types | Articles must meet a minimum quality threshold based on JBI checklist scores (e.g., “Yes” for ≥70% of the applicable items) | Articles with methodological flaws, unclear design, or poor validity based on JBI tool |

| Data extraction protocols (Using: PRISMA data extraction form) | Structured approach for extracting bibliographic, methodological, and outcome data using PRISMA-compliant templates | Key elements (e.g., title, authors, year, objectives, methods, findings, solutions, limitations) must be extractable into a standardized PRISMA form | Articles lacking sufficient detail or standardization for inclusion in data synthesis |

Results

In this section, we outline our analyses and findings to answer the research questions (RQs).

RQ1: What is the study trend over time?

To understand the publication drift, we examined the study trends based on publication and distribution among the key research publishers over a specific timeline.

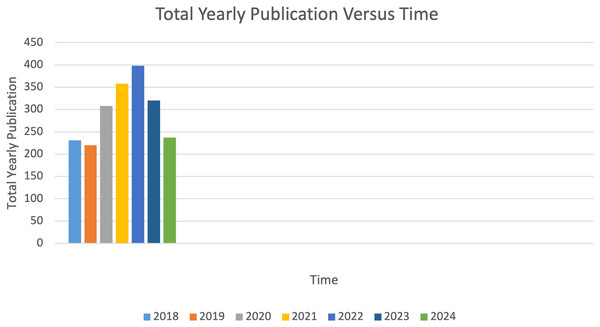

Figure 2 illustrates the publication trend of Android classification (AC) studies over a span of seven years (January 2018 to October 2024). The data reveals a gradual increase in the number of publications over this period. Additionally, the cumulative number of publications, as depicted in Fig. 2, highlights a noticeable rise in the curve’s slope between 2020 and 2024. This trend indicates that the adoption of ML techniques for Android malware classification (AMC) has gained significant momentum since 2020. The data indicate that 2022 recorded the highest number of publications, while 2019 had the lowest. The decline in 2019 is attributed to the onset of COVID-19, which significantly disrupted scientific research activities.

Figure 2: Total yearly annual research scope publication of the popular scientific research publishers.

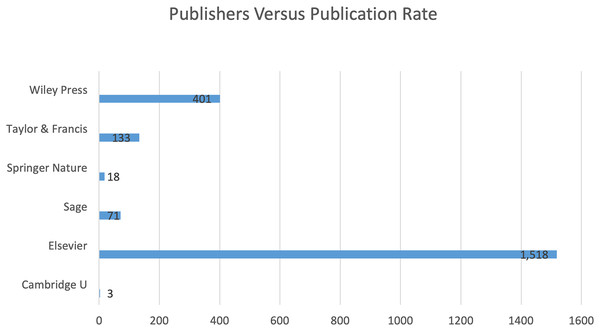

Table 3 and Fig. 2 illustrate the distribution of publications across various publishers over the years. Within the 2018–2024 timeframe, Elsevier led with 1,517 research articles, followed by Wiley with 401 articles, Taylor & Francis Group with 127 articles, Sage Publication with 71 articles, Springer Nature with 18 articles, and Cambridge University Press with three articles. The total number of articles published during this period is 94. Furthermore, the cumulative publication trend shown in Fig. 3 reveals a significant increase in publications from Elsevier. This upward trend reflects the impact of factors such as high-quality journals, rigorous peer review processes, competitive publication fees, open access availability, enhanced discoverability, and robust researcher support.

| YR | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | TP | APT (A) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cambridge University press | 2 | x | x | x | 1 | x | x | 3 | √ |

| Elsevier | 168 | 161 | 219 | 257 | 258 | 246 | 209 | 1,518 | √ |

| Sage publication | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | 94 | √ |

| Springer nature | x | 1 | x | 1 | 5 | 7 | 4 | 18 | √ |

| Taylor & Francis group | 11 | 17 | 26 | 20 | 26 | 20 | 13 | 133 | √ |

| Wiley press | 50 | 41 | 63 | 80 | 109 | 47 | 11 | 401 | √ |

| Total per year (Article) | 231 | 220 | 308 | 358 | 398 | 320 | 237 | 4,262 | √ |

Note:

YR, Year; TP, total publishing time; APT (A), advanced persistent threat (Android); U, undefined; X, absence; Ö, presence.

Figure 3: Research scope publication of the key scientific research publishers.

Table 3, YR = Year TP = Total publishing Time, APT (A) = Advanced Persistent Threat (Android), U = Undefined, X = Absence, and √ = Presence.

What are the Android malware behaviors over time?

To analyze trends in Android malware behavior, we reviewed key Android malware types based on their distinct behavioral patterns over the years. Additionally, the research question was divided into two parts as follows:

Android malware behaviors (1900–1999)

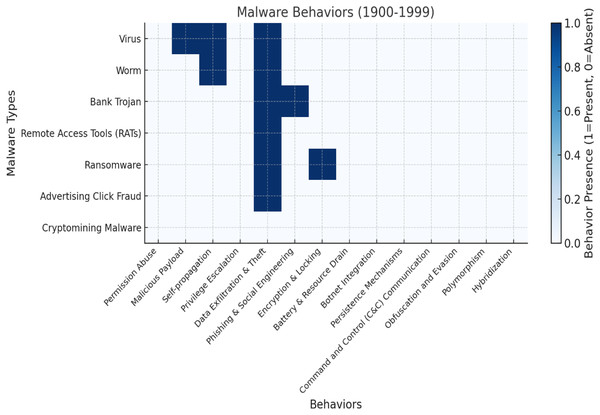

Table 4 showcases the early Android malware evolution rate in the years 1900–1999 based on key variant features. Android malware in this era is less sophisticated and advanced due to its leverage on less advanced techniques that enable it to evade detection subtly on devices and exploit vulnerabilities for financial gain.

| YR | 1900 | To | 1999 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AM | PM | MP | SP | PE | DET | PSE | EL | BRD | BI | PMs | C&C | OE | P | H |

| V | × | √ | √ | × | √ | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × |

| W | × | × | √ | × | √ | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × |

| BT | × | × | × | × | √ | √ | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × |

| RATs | × | × | × | × | √ | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × |

| R | × | × | × | × | √ | × | √ LSO | × | × | × | × | × | × | × |

| ACF | × | × | × | × | √ | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × |

| CM | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × |

Note:

YR, Year range; AM, Android malware; PA, permission abuse; MP, malicious payload; SP, self-propagation; PE, privilege escalation; DET, data exfiltration and theft; PSE, phishing and social engineering; EL, encryption and locking; BRD, battery and resource drain; BI, botnet integration; PMs, persistence mechanisms; C&C, command and control communication; OE, obfuscation and evasion; P, polymorphism; H, hybridization; V, virus; W, worm; BT, bank Trojan; RATs, remote access tools; R, ransomware; ACF, advertising click fraud; CM, cryptomining malware; LSO, lock screen only.

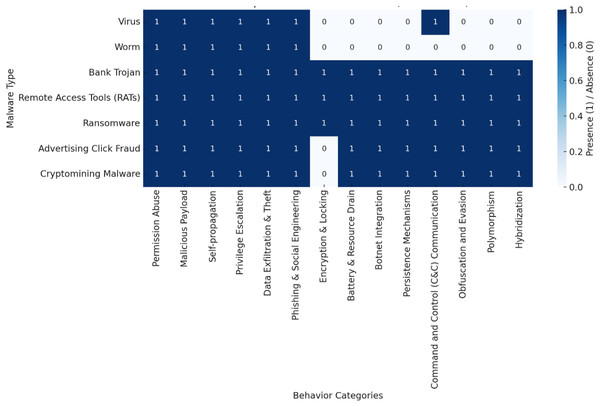

Figures 4 and 5 illustrate the trends, where the following abbreviations are used: YR=Year Range, AM=Android Malware, PA=Permission Abuse, MP=Malicious Payload, SP=Self-propagation, PE=Privilege Escalation, DET=Data Exfiltration and Theft, PSE=Phishing and Social Engineering, EL=Encryption and Locking, BRD=Battery and Resource Drain, BI=Botnet Integration, PMs=Persistence Mechanisms, C&C=Command and Control Communication, OE=Obfuscation and Evasion, P=Polymorphism, and H=Hybridization, V=Virus, W=Worm, BT=Bank Trojan, RATs=Remote Access Tools, R=Ransomware, ACF=Advertising Click Fraud, CM=Cryptomining Malware, LSO=Lock Screen Only (Pahlevan Sharif, Mura & Wijesinghe, 2019; Lecci & Cisewski, 2014; Lv et al., 2016; Okoli, 2015; Vaismoradi, Turunen & Bondas, 2013; Braun & Clarke, 2006).

Figure 4: Malware evolution and behaviour (1900–1999).

Figure 5: Malware evolution and behaviour (2000–2024).

0 denotes absence while 1 depicts presence.Figure 4 depicts the malware’s evolution and behaviors (1900–1999). The dark blue shades represent the presence of a specific malware behavior, while the lighter shades denote the absence of a specific malware behavior. Based on the above chart, we discuss and categorize this era into subsections as follows:

Dominance of core malware behaviors: The malicious payloads and data exfiltration, are evident across various malware types, including viruses, worms, bank Trojans, and ransomware (Afianian et al., 2019). Self-propagation remains a significant feature of viruses and worms, facilitating their spread without requiring user intervention (Boukerche & Zhang, 2019). The prevalence of key malware behaviors, including malicious payload delivery and data theft, is driven by their capacity to steal sensitive data, corrupt systems, self-propagate, and exploit vulnerabilities across diverse malware families (Kuraku & Kalla, 2020).

Emergence of specialized threats: The bank Trojans and ransomware, highlights their targeted behavior, focusing on data theft, phishing, and encryption (Aslan et al., 2023). Privilege escalation appeared across diverse malware types but was not universally implemented (Rangwala et al., 2014). The surge in these threats can be attributed to their ability to focus on specific, high-value targets, emphasizing data theft, phishing, and privilege escalation (Ryan, 2021).

Limited advanced techniques: The botnet integration, command and control (C&C) communication, and obfuscation and evasion, were largely absent, indicating less sophisticated malware during this era (Catalano et al., 2022). Polymorphism and hybridization, which are critical for avoiding detection, were not utilized (Rendell, 2019). The limited advanced techniques observed in malware between 1900 and 1999 can be attributed to the lack of botnet integration, the absence of C&C communication, and the minimal use of obfuscation and evasion methods (Davanian, Faloutsos & Lindorfer, 2024).

Niche behaviors: Ransomware stood out with its unique screen-locking mechanism (Catalano et al., 2022). Advertising click fraud and cryptomining malware exhibited no significant behaviors from this list, showing minimal impact during this period. From 1900 to 1999, ransomware introduced its distinctive screen-locking mechanism, differentiating it from other malware types (Davanian, Faloutsos & Lindorfer, 2024). Unlike traditional malware, which typically aimed to destroy or steal data, ransomware prevented users from accessing their systems, demanding a ransom for restoration. This approach proved particularly effective by directly targeting user control over systems and data. However, other forms of malware, such as advertising click fraud and cryptomining, had minimal impact during this period. These behaviors, which gained prominence in later years, did not play a significant role in the 1900s (Rendell, 2019). Advertising click fraud, which involves inflating ad clicks, and cryptomining, which uses system resources for cryptocurrency mining, were not yet major concerns in the cybersecurity landscape of the 20th century (Alauthman et al., 2024).

Implications: This analysis captures the initial phases of malware development, characterized by limited sophistication and a primary focus on exploiting specific vulnerabilities (Catalano et al., 2022). In the period following 1999, malware trends likely evolved with greater complexity and the integration of advanced features as attackers responded to enhanced defensive strategies (Javed, El-Sappagh & Abuhmed, 2025).

Android malware behaviors (2000–2024)

Table 5 showcases the early Android malware evolution rate in the years 2000–2024 based on key variant features. Android malware in this era is super sophisticated and advanced due to its leverage on advanced techniques that enable it to evade detection, persist on devices, and exploit vulnerabilities for financial gain. Figure 2 depicts the distribution rate based on key features.

| YR | 2000 | To | 2024 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AM | PA | MP | SP | PE | DET | PSE | EL | BRD | BI | PMs | C&C | OE | P | H |

| V | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | × | × | × | × | × | √ | × | × |

| W | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × |

| BT | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | × | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| RATs | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| R | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| ACF | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | × | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| CM | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | × | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

Note:

YR, Year range; AM, Android malware; PA, permission abuse; MP, malicious payload; SP, self-propagation; PE, privilege escalation; DET, data exfiltration and theft; PSE, phishing and social engineering; EL, encryption and locking; BRD, battery and resource drain; BI, botnet integration; PMs, persistence mechanisms; C&C, command and control communication; OE, obfuscation and evasion; P, polymorphism; H, hybridization; V, virus; W, worm; BT, bank Trojan; RATs, remote access tools; R, ransomware; ACF, advertising click fraud; CM, cryptomining malware; LSO, lock screen only.

Figure 5 depicts the malware’s evolution and behaviors (2000–2024). The dark blue shades (1 shown in dark blue shades) represent the presence of a specific malware behavior, while the lighter shades (0 shown in light shades) denote the absence of a specific malware behavior. Based on the above chart, we discuss and categorize this era into subsections as follows:

Common behaviors across malware: Permission abuse and malicious payloads are observed among all the malware types and showed system infiltration as their respective modes of attack (Afianian et al., 2019). Also, privilege escalation and data filtration are utilized across various malware types consistently in their respective malicious activities. From 2000 to 2024, a common behavior across various malware types is the abuse of permissions and the use of malicious payloads, which demonstrate system infiltration as the primary attack method. Malware often exploits vulnerabilities to gain unauthorized access to systems or data. Once inside, malicious payloads—harmful components hidden within applications or files—execute damaging actions, such as data corruption, theft, or encryption (Ryan, 2021). Privilege escalation is another consistent behavior observed across malware types. This technique allows malware to elevate its access rights within the system, enabling it to perform unauthorized actions, such as installing additional malware or gaining control over administrative functions (Thakkar & Lohiya, 2022). Additionally, data filtration, where sensitive information is extracted and sent out of the system, is commonly used for malicious purposes such as theft or espionage (Tari et al., 2023).

Advanced techniques by sophisticated malware: Ransomware demonstrates the broadest range of behaviors, including encryption, locking, botnet integration, and hybridization, showcasing its adaptability and destructive potential (Bojarajulu, Tanwar & Singh, 2023). l. Bank Trojans and RATs exhibit comprehensive behaviors, particularly in persistence mechanisms and command and control (C&C) communication, emphasizing their use in targeted attacks. Sophisticated malware, especially ransomware, is notable for its diverse and destructive behaviors. Ransomware is particularly known for its ability to encrypt and lock files, integrate with botnets, and, in some cases, hybridize with other malware types, which enhances its impact and adaptability across various attack scenarios. This flexibility makes ransomware especially hazardous from 2000 to 2024, as it rapidly adjusts to different targets and environments (Bojarajulu, Tanwar & Singh, 2023). Bank Trojans and RATs display distinct but complementary behaviors. Both malware types employ advanced persistence techniques to remain active on infected devices. They also rely extensively on C&C communication to maintain control over compromised systems and execute specific attacks, such as stealing banking credentials and gaining remote access for further malicious actions (Bécue, Praça & Gama, 2021).

Emerging trends: Newer malware types (cryptomining malware and advertising click fraud) share traits such as resource drain and polymorphism and show their respective evolution in monetization strategies via resource exploitation. Emerging malware types, particularly cryptomining malware and advertising click fraud, share key characteristics such as resource drainage and polymorphism, making them adaptable and harder to detect (Ørmen & Gregersen, 2023). Cryptomining malware, also known as cryptojacking, exploits a victim’s computing resources to mine cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin, draining power and CPU resources without consent (Almurshid et al., 2024). This malware has evolved in its approach, making it harder to distinguish from legitimate activity and offering attackers a consistent monetization model based on resource exploitation (Almurshid et al., 2024). Similarly, advertising click fraud involves manipulating online advertising systems by generating false clicks, leading to resource consumption on both the victim’s system and advertising platforms (Bojarajulu, Tanwar & Singh, 2023). This type of malware also exhibits polymorphic behaviors to evade detection while contributing to fraudulent gains (Bojarajulu, Tanwar & Singh, 2023). These newer forms of malware have continuously evolved since 2000, capitalizing on resource exploitation as a central monetization strategy (Ørmen & Gregersen, 2023).

Legacy malware: Viruses and Worms display limited adaptability with fewer behaviors related to advanced evasion techniques. Their relevance appears to have diminished as more sophisticated threats have emerged. Legacy malware, such as viruses and worms, shows limited adaptability and exhibits fewer behaviors related to advanced evasion techniques compared to more sophisticated, modern threats (Bécue, Praça & Gama, 2021). These older malware types primarily rely on basic propagation methods like exploiting system vulnerabilities or human error, but they lack the polymorphic and advanced behaviors seen in contemporary threats. The development of more evasive techniques, such as anti-detection measures and advanced persistence mechanisms, has shifted the focus toward more advanced malware like ransomware, bank Trojans, and remote access tools (RATs), which are far more adaptable and capable of evading modern defenses. As a result, the relevance of traditional viruses and worms has diminished, giving way to more complex and targeted cyberattacks that take advantage of advanced technologies and strategies to compromise systems (Almurshid et al., 2024). Despite their reduced prominence, legacy malware still poses risks due to their ability to evade outdated defenses and exploit unpatched vulnerabilities.

Polymorphism and hybridization: These are increasingly prominent in advanced malware (ransomware), reflecting an emphasis on adaptability to evade detection. Polymorphism and hybridization have become essential techniques in advanced malware, particularly ransomware, as cybercriminals enhance their ability to evade detection (Bojarajulu, Tanwar & Singh, 2023). Polymorphism involves modifying the code or appearance of malware each time it runs, making it harder for signature-based detection systems to recognize it. Hybridization combines multiple evasion methods, such as static and dynamic analysis, to further complicate detection efforts by blending different techniques to bypass security measures. These strategies are especially prevalent in ransomware attacks, which often use advanced machine learning and deep learning methods to avoid detection. Ransomware variants continuously evolve by altering their code or adopting new behaviors to outpace traditional detection systems (Almurshid et al., 2024). Furthermore, deep learning models and hybrid detection approaches, which merge static and dynamic analysis, are used to detect these threats more effectively, though they still face difficulties in dealing with highly adaptive malware.

Implication: This analysis highlights the advanced stages of malware development, characterized by high sophistication. It examines various techniques, including polymorphism, hybridization, vulnerability exploitation, encryption, and locking, employed to evade detection and facilitate malicious activities. This period is marked by increasing complexity and the integration of enhanced features as attackers continuously adapt to evolving defensive measures.

What are the malware families based on platforms and infected regions?

To understand malware families’ distribution on various platforms and regions, we reviewed and investigated the malware families’ distributions on various platforms (PCs, Android, IoT devices) and global regions of the world. In this section, we discuss, answer and analyse the research question with regards to the various malware families’ distribution based on their respective platform, impacted region, severity rate, and key behavioral features. In this section, we further subdivide and discuss the research question into two subsections:

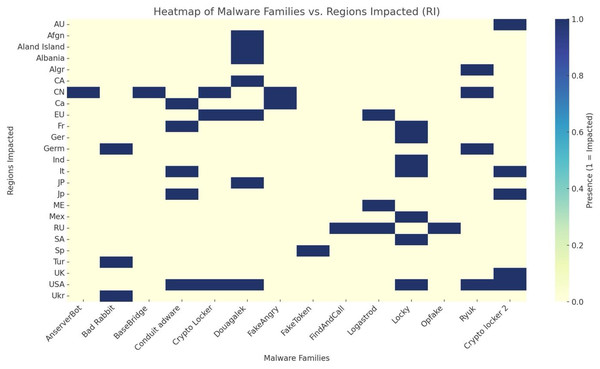

Android malware families distribution on various geographical regions

In this subsection, we analyse and discuss the various Android malware families’ distributions across numerous geographical regions. Table 6 depicts the various advanced Android mobile malware families based on key behaviors, platform, and impacted regions. Figure 6 showcases the malware families’ distributions in various regions of the world, and in this map chart, the X-axis represents the infected regions, while the Y-axis denotes the malware families. The color intensity reflects the severity rate and infestation frequency in the respective regions. In Table 6, AMT=Advanced Malware Type, CF=Corresponding Families, RI=Region Infected, HA=Hash Algorithm, O=Obfuscation, DM=Defence Mechanism, H(B)=Hybridization (Bundleware), P=Polymorphism, S=Severity, E=Evolution, PI=Platform Infected, PM=Propagation Mode.

| AMT | CF | RI | PI | HA | O | DM | H(B) | P | S | P | E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Andress, 2014; Zhan et al., 2022; Steadman & Scott-Hayward, 2021; Ullah et al., 2018; Nadler, Aminov & Shabtai, 2019; Kim et al., 2022; Nadler, Aminov & Shabtai, 2019; Faircloth, 2017; Li & Liao, 2022; Hostiadi & Ahmad, 2022; Rahman & Tomar, 2020; Putra, Hostiadi & Ahmad, 2022; Kasim, 2021; Natarajan & Subramani, 2012; Kar, Panigrahi & Sundararajan, 2016; McWhirter et al., 2018; Xie, Li & Sun, 2022; Halgamuge, 2022; Alghamdi & Bellaiche, 2023; Dong, Liu & Wu, 2022; Xing, Sun & Deng, 2022; Anonymous, 2013; Salerno, Sanzgiri & Upadhyaya, 2011; D’Orazio et al., 2017; Qamar, Karim & Chang, 2019; Bojjagani, Brabin & Rao, 2020; Verkijika, 2019; Goel & Jain, 2018; Vishwanath, 2016; Yoo & Cho, 2022; Bhardwaj et al., 2021; Tharayil et al., 2020; Patel, Han & Jain, 2016; Wang et al., 2019a; Rustamov et al., 2020; Patil, Bhilare & Kanhangad, 2016; Su, Chuah & Tan, 2012; Tharayil et al., 2020; Sharma & Rattan, 2021; Guido et al., 2013; Homayoun et al., 2019; Brewer, 2014; Diba et al., 2018; Makhdoom et al., 2019; Taneja, 2013; Junger et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2023; Thejas et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2020; Shang et al., 2020; Peris-Lopez & Martín, 2017; Gezer et al., 2019; Abualola et al., 2016; Malwarebytes, n.d; Help Net Security, 2022; Mani et al., 2020; Lian & Jhe, 2022; Zimba et al., 2018; Caprolu et al., 2021; Al-Turjman & Salama, 2021; Crussell, Stevens & Chen, 2014; Sadeghpour & Vlajic, 2021; Thejas et al., 2021; Richet, 2022; Chertov & Pavlov, 2013; Sisodia & Sisodia, 2022; Seals & Seals, 2019; McAfee, 2022; Cisco, 2022; Kaspersky, 2022b; Malwarebytes, 2022; Oz, De Donna & Di Pietro, 2022; Kaspersky, 2022c; Huete Trujillo & Ruiz-Martínez, 2021; Corll et al., 2023; Niu et al., 2021; Singleton, Kiefer & Villadsen, 2025; Mundo, 2020; Cohen & Herzog, 2020; Kaspersky, 2022d; Kaspersky, 2022e; Komornik, 2022; Belding, 2021; Cloudflare, 2022; Abdel-Basset et al., 2023; Kaspersky, 2021; Meng et al., 2023; Hull, John & Arief, 2019; Kao, Hsiao & Tso, 2019; Symantec, 2015; Stubbs, 2019) | |||||||||||

| Bank Trojan, Remote Access Tools (RATs) | AnserverBot | CN | Android. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | H |

| RW, RATs | Bad Rabbit | Ukr, Tur, Germ | Android, P.C.s, IoT devices | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| BT, RATs | BaseBridge (AdSMS) | C.N | Android. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| √ | BeanBot | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| √ | Pjapps | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| √ | BGSERV | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| ACF, CM | Conduit adware | USA, Fr, Ca, Jp, It | Android, P.C.s, and IoT devices | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| ACF, RATs | CruseWin (CruseWind) | C.N | Android. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| RW, RATs | Crypto Locker | USA, C.N., E.U. | Android, P.C.s, IoT devices | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| RATs | DroidCoupon | CN | Android. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| RATs, BT | DroidDeluxe | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| ACF, RATs, and BT | DroidDream (DORDRAE) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| √ | DreamLight. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| BT, ACF, CM and RATs | DroidKungFu (LeNa) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| √ | Smssend (fake player) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| √ | Gamblersms | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| √ | Geinimi | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| √ | GGTracker | USA, CN, RU | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| √ | GingerMaster (GingerBreaker) & Gone 60 (gonein 60) GoldDream | CN | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| √ | GPSSMSSpy (mobinauten, SmsHowU, SMS spy) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| √ | HippoSMS & Jifake & jSMSHider (smshider, Xsider) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| √ | KMin (ozotshielder & LoveTrap) (cosha, Luvrtrap) & Nickyspy (Nickispy) & Plankton & | CN | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| RogueLemon, & RogueSPPush, & SMSReplicator, SndApps, & Spitmo, & Tapsnake, & Walkinwat, & YZHC, & Zsone, & Battery Doctor, & C14, & Counterclank, | |||||||||||

| RATs, BT, ACF | Douagalek, DropDialer, & Zeus Trojan (Zbot, Zeus Gameover, Trojan-Spy.Win32.Zbot) | USA, CA, Afgn, Aland Island, Albania, J.P., E.U. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| BT, ACF, RATs | FakeAngry (AnZhu) & Faketimer (oneclick fraud) | CN & Ca | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| √ | FakeToken | Sp | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| √ | FindAndCall & Gamex (multidrop) | RU | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| √ | Logastrod & Luckycat & Moghava | RU & EU | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| √ | Logastrod & Luckycat & Moghava | ME & EU | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| RW, RATs, CM | Locky | Fr, Ger, Ind, USA, SA, It, Mex | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| BT, ACF, CM, RATs | Opfake | RU | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| BT, ACF, and CM | Rootsmart (Bmaster) & Steek Steek (fake lottery) & VDloader | CN | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| RW, RATs | Ryuk | Germ, CN, Algr, USA | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| RW, CMM | Crypto locker | USA, Jp, U.K., Is A.U. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

Note:

AMT, Advanced malware type; CF, corresponding families; RI, region infected; HA, Hash algorithm; O, obfuscation; DM, defence mechanism; H(B), hybridization (Bundleware); P, polymorphism; S, severity, E, evolution, PI, platform infected; PM, propagation mode.

Figure 6: Infected regions rate based malware families.

Figures 6, 7 and Table 6 highlight the global distribution of malware threats, emphasizing the regions of China, the USA, and Russia as critical hotspots. In this analysis, we highlight and discuss the key factors contributing to the severity, diversity, and geographical concentration of malware threats, providing deeper insights into the evolving cybersecurity landscape:

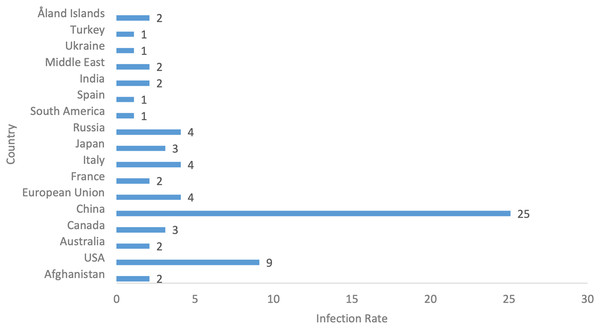

Figure 7: Infected regions rate.

High severity and frequent infestations: Regions such as the USA, China, and Russia serve as breeding grounds for malware due to their heavy reliance on digital infrastructures and vast online user bases. Advanced banking systems in these regions make them ideal targets for malware like the Zeus Trojan, which exploits vulnerabilities in financial institutions to steal sensitive data. The interconnectedness of their systems amplifies the impact, turning local infections into widespread threats through network propagation.

Diversity of malware families: The varied functionalities of malware families, including CryptoLocker (file-encrypting ransomware) and Ryuk (used in targeted attacks), demonstrate how attackers exploit multiple vectors, from phishing campaigns to vulnerabilities in unpatched systems. Despite their functional differences, these malware types share a reliance on social engineering tactics, making them versatile and difficult to predict. This diversity underscores the need for comprehensive defense mechanisms that address both individual and enterprise-level threats.

Cybersecurity gaps and infrastructure vulnerabilities: The presence of outdated software and insufficient security measures in regions like Russia, Ukraine, and India creates an environment where adware (e.g., Conduit) and dialer-based malware (e.g., DropDialer) thrive. These gaps indicate the prevalence of poor cybersecurity hygiene and limited awareness, reinforcing the urgent need for widespread adoption of advanced security tools and practices.

Economic and geopolitical factors: Regions with significant geopolitical influence, such as China, the USA, and Russia, are prime targets for ransomware like Bad Rabbit and Ryuk. These attacks focus on critical infrastructure, including energy grids, healthcare, and government systems, which are integral to both the economy and national security. The high stakes of these sectors make them lucrative targets for ransomware campaigns aimed at extortion or disruption.

The interplay between technological dependence, malware diversity, cybersecurity gaps, and geopolitical importance creates a multifaceted threat landscape. Addressing these challenges requires a combination of robust technological defenses, user education, and international collaboration to mitigate risks and reduce the prevalence of high-severity malware.

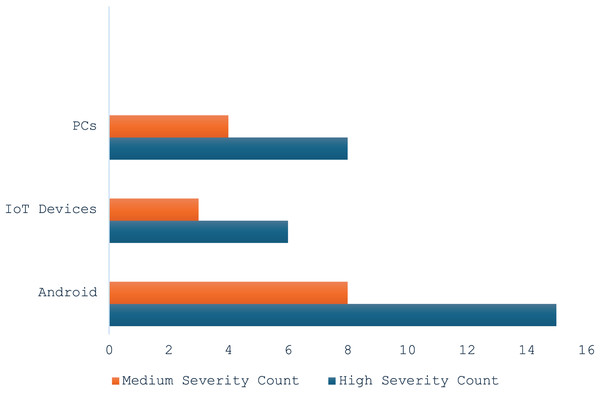

Android malware families’ severity distribution on various platforms and behaviour count

In this subsection, we analyse and discuss Android malware families’ severity distribution across various platform and behaviour count. Figure 8 showcases the malware families’ distributions on key platforms, and in this map chart, the X-axis represents the key platforms, while the Y-axis denotes the malware severity distribution counts. Figure 9 showcases the Android malware propagation count based on various variant behaviors.

Figure 8: Various platforms malware severity rate.

Figure 9: Advanced Android mobile propagation rate.

To highlight significant trends in malware targeting and propagation techniques, shedding light on evolving threats in cybersecurity, we discuss and analysis these significances based on the following:

Platform targeting: Figure 8 demonstrates the steady surge in the Android severity counts, PCs, and IoT devices, suggesting that Android has emerged as the most targeted platform, primarily due to its open-source nature and vast user base, offering attackers numerous vectors to exploit. IoT devices rank second, reflecting their increasing adoption and weak security implementations, which often lack robust update mechanisms. PCs, while still a focus, are targeted less than Android and IoT, likely due to improved security measures on modern desktop systems.

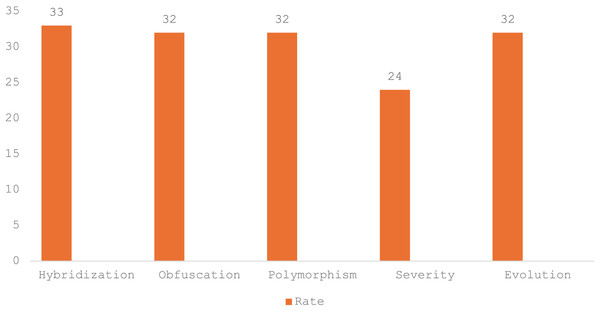

Advanced propagation techniques: Figure 9 demonstrates a steady rise in the polymorphism, hybridization, severity rate, and obfuscation, suggesting that most modern malware demonstrates hybridization, where different malicious techniques are combined to maximize impact and evade detection. Polymorphism allows malware to change its code structure frequently, while obfuscation disguises malicious payloads from security tools. These behaviors are particularly effective against signature-based detection systems, highlighting the sophistication of recent threats.

Surge in evolutionary malware: Figure 9 demonstrates a steady curve rise in the polymorphism, hybridization, severity rate, and obfuscation. The observed surge in polymorphism, severity rate, hybridization, and obfuscation reflects malware’s adaptability. Attackers now prioritize stealth and persistence, enabling prolonged infiltration to maximize data theft or system damage.

These findings underscore the urgent need for enhanced AI-driven threat detection systems and better user awareness programs to mitigate malware risks across all platforms.

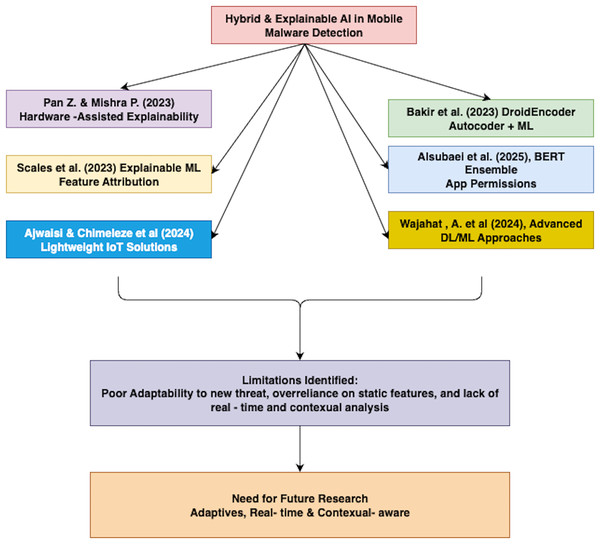

Limits of hybrid and explainable AI in advanced mobile malware detection

Pan & Mishra (2023) developed a hardware-assisted, explainable AI framework for malware detection that uses hardware performance counters and trace buffers to localize malicious behavior. Their approach balances detection accuracy with interpretability by comparing decision trees and recurrent neural networks (RNNs). Bakır & Bakır (2023) discovered that combining auto-encoder-based feature extraction with machine learning algorithms significantly improves Android malware detection. Their model, DroidEncoder, demonstrated strong performance using artificial neural networks (ANNs), convolutional neural network (CNN), and VGG19-based auto-encoders to extract features, which enhanced the accuracy of traditional classifiers. Scalas, Rieck & Giacinto (2023) show that explainable machine learning improves malware detection by making model decisions transparent. They use feature attribution methods to identify key behaviors, enhancing both accuracy and interpretability.

Alsubaei et al. (2025) propose a BERT-ensemble framework for Android malware detection that achieves high accuracy (98%) and strong precision and recall by analyzing app permissions. The model is effective and privacy-aware for IoT applications. Alwaisi et al. (2024) present a lightweight TinyML-based anomaly detection method for IoT systems, achieving over 96.9% accuracy with low resource usage using on-device Decision Trees. Chimeleze et al. (2024) propose a lightweight Android malware detector that uses a hybrid fuzzy C-means with simulated annealing (FCMSA) for clustering app permissions, followed by LightGBM for classification. Wajahat et al. (2024b) introduced advanced feature engineering combined with machine learning techniques to improve Android malware detection, achieving higher accuracy and resilience against evolving threats. Wajahat et al. (2023) proposed an adaptive semi-supervised deep learning framework for Android malware detection. Their model leverages both labeled and unlabeled data, improving detection accuracy while reducing dependency on large labeled datasets. Wajahat et al. (2024a) developed a deep learning-based scheme for Android malware detection that optimizes performance metrics and computational resource usage, enhancing both efficiency and accuracy. Qureshi et al. (2021) analyzed key challenges in modern network forensic frameworks, highlighting issues such as data volume, encryption, real-time analysis, and the need for scalable, efficient forensic solutions. Azeem et al. (2020) examined the impact of code cloning in mobile applications, revealing that it can lead to increased maintenance costs, security vulnerabilities, and reduced code quality.

Figure 10 depicts the hybrid and explainable AI in advanced mobile malware detection frameworks and associated limitations.

Figure 10: Hybrid and explainable AI in advanced mobile malware detection framework.

Despite notable progress in detection accuracy and interpretability, current Android malware detection approaches remain limited by poor adaptability to evolving threats, overreliance on static features, and insufficient real-time and contextual analysis; highlighting the need for more resilient, adaptive, and context-aware solutions.

What are the limitations of the existing Android taxonomy?

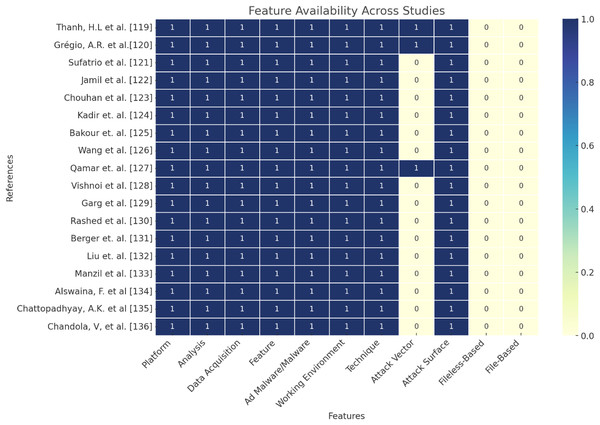

To understand the limitation of the existing Android taxonomy, in this section, we discuss and analyse the prevalent Android malware taxonomies based on their limitations and classifications, we examine and evaluate these taxonomies based on these key features: analysis methods, feature distinctions, types of Android malware (traditional or advanced), platforms, operational settings, data retrieval techniques, attack vectors, and file-based or file-less characteristics.

Table 7 depicts the prevalent and popular Android mobile malware taxonomies. Figure 11 showcases the research gap in prevalent Android malware taxonomies. Where: × denotes unavailable, Ad malware denotes Advanced Malware, √ represents available, P(A)=Platform (Android), A=Analysis, DA=Data Acquisition, F=Feature, AM=Advanced Malware, WE=Working Environment, T=Techniques, AV=Attack Vector, AS=Attack Surface, FLB=Fileless-Based, FB=File-Based.

Note:

Where: × denotes unavailable, Ad malware denotes Advanced Malware, √ represents available. P(A), Platform (Android); A, analysis; DA, data acquisation; F, feature; AM, advanced malware; WE, working environment; T, techniques; AV, attack vector; AS, attack surface; FLB, fileless-based; FB, file-based.

Figure 11: Existing Android malware taxonomy research gaps.

The dark blue intensity reflects the presence (1), while the lighter intensity denotes the absence (0) of each feature, helping to easily identify patterns and gaps in the data (Thanh, 2013; Grégio et al., 2015; Sufatrio et al., 2015; Jamil & Shah, 2016; Chouhan & Shah, 2017; Abdul Kadir, Stakhanova & Ghorbani, 2018; Bakour, Ünver & Ghanem, 2019; Wang et al., 2019b; Qamar, Karim & Chang, 2019; Vishnoi et al., 2021; Garg & Baliyan, 2021; Rashed & Suarez-Tangil, 2021; Berger, Hajaj & Dvir, 2022; Liu et al., 2024; Manzil & Naik, 2023; Alswaina & Elleithy, 2020; Chattopadhyay, Sengupta & Pal, 2024; Chandola, Banerjee & Kumar, 2009).In Fig. 11, the dark blue intensity reflects the presence (1), while the lighter intensity denotes the absence (0) of each feature, helping to easily identify patterns and gaps in the data. The heatmap provides a clear overview of the feature distribution across various studies, shedding light on trends, focus areas, and potential gaps in malware research. In this section, we discuss, draw, analysis and highlight these key insights from the related works and the heatmap visualization chart. We analyse and discuss as follows:

Uniform focus on core features: The consistent inclusion of features like platform, analysis, data acquisition, and working environment underscores their foundational role in malware research. These aspects are universally critical for understanding malware behavior and designing effective mitigation strategies. The emphasis on such features suggests a mature baseline understanding within the research community.

Underrepresentation of file-based and fileless attacks: The sparse representation of file-based and fileless malware attacks indicates a significant research gap, despite these being prevalent vectors in modern threat landscapes. This oversight implies that the research community might not be prioritizing these attack types, leaving a blind spot in addressing advanced persistent threats (APTs). Future studies should explore these vectors to provide a more comprehensive understanding of emerging attack mechanisms.

Comprehensive techniques and attack surface coverage: The frequent analysis of techniques, attack vectors, and attack surfaces reflects a robust effort to categorize and understand malware behavior. These areas are pivotal for mapping how malware spreads and identifying potential vulnerabilities. Such coverage shows the research community’s focus on the operational dynamics of malware.

Neglect of hybrid attack models: Hybrid attack models, which combine file-based and fileless techniques, are largely overlooked. This is concerning given their growing prominence in sophisticated attacks. Addressing this gap would not only broaden the scope of malware research but also provide deeper insights into complex, multi-faceted threats.

Consistent exploration of ad malware and malware variants: The persistent focus on adware and malware variants highlights their pervasive impact on diverse platforms. This consistent inclusion suggests a proactive approach to tackling both traditional and emerging malware forms, ensuring that foundational threats remain a priority.

Insights on cross-platform threat analysis: The universal inclusion of the Platforms feature underscores the importance of cross-platform threat analysis. This consistency reflects the real-world challenges posed by malware targeting diverse ecosystems like Android, Windows, and IoT devices. The emphasis on this feature ensures that research remains relevant to a wide range of systems and technologies.

Recommendations for future research: Strengthen Analysis of File-Based and Fileless Malware: Addressing the gaps in research on file-based and fileless attack vectors is critical. These areas demand immediate attention to combat the rising sophistication of APTs.

What are the key classifications to introduce to enhance the existing Android taxonomy?

In this section, we discuss and analyse the key classification components needed to enhance the existing Android malware taxonomy and propose a new, improved taxonomy along with its significance. In this section, we discuss and subdivide them into two subsections: the first subsection discusses and examines the various components of the proposed enhanced Android malware taxonomy, while the second subsection focuses on discussing and emphasizing its significance.

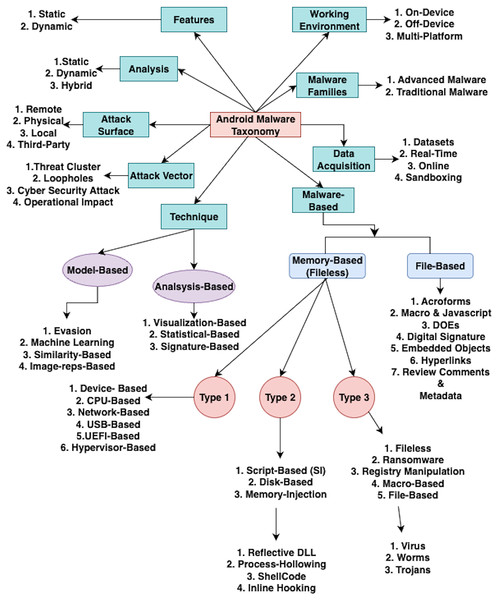

Proposed enhanced Android malware taxonomy

In this first subsection, to enhance the existing Android taxonomy, we explore ways to enhance the existing Android malware taxonomies based on the findings in categories 1–2. The improved taxonomy aims to aid APT analysts, researchers, and users in understanding the subcategorization of advanced Android malware based on key features. In this enhanced Android malware taxonomy, we examine, evaluate, and introduce the two key features: memory-based (fileless) and file-based elements. Figure 12 depicts the enhanced Android malware taxonomy.

Figure 12: The enhanced advanced Android malware taxonomy.

In this enhanced advanced Android malware taxonomy, we subcategorize them into two primary types: memory-based (file-less) and file-based.

Subcategory One: Memory-Based Malware: Memory-based Android malware exploits vulnerabilities or manipulates processes within the device’s memory (RAM) to compromise the Android operating system. This malware evades traditional detection methods by residing in the device’s volatile memory, making it challenging to detect APT threats. Memory-based advanced malwares are categorized into three types, discussed as follows:

Type 1: This type is associated with these key features:

Device-based: exploits hardware or firmware vulnerabilities, hinders device performance, and potentially compromises sensitive data.

CPU-based: Targets the device’s CPU to manipulate and disrupt operating system performance and unauthorized activities.

USB-based: Injects malicious code into device memory via USB connections from infected external devices, leading to unauthorized access or data theft.

UEFI-based: The Unified Extensible Firmware Interface (UEFI) is exploited during device boot to compromise firmware, aiding the APT threats.

Network-based: The network protocol vulnerabilities are exploited, facilitating unauthorized access or data exfiltration through smartphone network connections.

Hypervisor-based: Targets the hypervisor layer, compromising the virtualized platform and potentially breaching Android OS defense.

Type 2: This type is associated with these key features:

Script-based Infection (SI): This infection exploits vulnerabilities in Android applications and the operating system to infiltrate device memory by executing malicious scripts, compromising device security through unauthorized actions.

Disk-based: This malware stores harmful code directly on the device’s storage, aiming to execute it and impact memory and data theft.

Memory-injection: This technique injects malicious code into the device’s volatile memory (RAM), hindering detection techniques performance. Dynamic Link Library (DLL) and process injection are employed in these injection attacks. Memory injection is subdivided into:

(a) ShellCode Injection: This injects malicious shellcode into a process’s memory to execute unauthorized commands and improve malware detection performance.

(b) Reflective DLL Injection: Malware injects DLLs into memory without traditional loading mechanisms, evading malware detection.

(c) Process hollowing: This malicious code replaces a legitimate process’s memory to evade defense detection.

(d) Inline hooking: This modifies program execution flow to redirect control to malicious code, allowing unauthorized activities in the Android OS.

Type 3: This type is associated with these key features:

Fileless Ransomware: This type operates in the Android device’s memory with no traces on the disk. It embeds malicious code in documents and scripts using native languages; macros execute ransomware attacks without traditional file storage; this makes it hard to detect.

Macro-Based: The macros exploit documents, such as Microsoft Word or Excel; this malware embeds malicious macros. When users open the document, the macros execute, infecting the Android device. This method relies on user interaction to initiate the malware’s actions.

File-Based: Involving executable files containing malicious code on the Android device, this malware is downloaded, installed, or executed, leading to various malicious activities. It was subdivided into:

(a) Worms: These exploit vulnerabilities in the Android system’s memory, self-replicating in the device’s memory, to spread to connected smartphone devices. Worm consumes system resources and network bandwidth and hinders device performance.

(b) Viruses: The device’s memory file is infected by a virus, modifying files and attaching to executable programs or documents. When executed or shared, viruses spread and hinder device performance.

(c) Trojans: Disguised as legitimate applications or files, Trojans operate in the device’s memory once installed, performing malicious activities such as data theft and unauthorized access.

Subcategory Two: File-Based Malware: File-based Android malware operates via traditional file techniques—applications and scripts—to exploit vulnerabilities and perform unauthorized actions on Android devices. It spreads via app downloads, email attachments, or file sharing. Memory-based malware relies on unique files for malicious activities. Improved Android malware in this subcategory is:

Acroforms-based: exploits PDF Acroforms to execute malicious actions.

Macro- and Javascript-based: Uses malicious macros and JavaScript to execute harmful commands.

Dynamic Data Exchange (DDE)-based: Allows data exchange between apps, posing defense risks in Word.

Digital Signature-Based: Manipulates digital signatures to appear legitimate.

Embedded Object-Based: The embedded objects are used to attack upon file opening.

Hyperlink-based: The hyperlinks are explored to direct users to malicious sites.

Review Comments and Metadata: Hidden malicious code in comments manipulates metadata to evade detection.

Significance of the enhanced Android malware taxonomy

In this second subsection, we discuss and emphasize the significance of the proposed enhanced Android malware taxonomy in addressing emerging malware threats.

Firstly, fileless malware, which operates by executing malicious code directly in memory rather than on the device’s file system, evades traditional file-based scanning methods. This type of malware exploits system tools to bypass detection mechanisms. The proposed taxonomy incorporates features of fileless malware, ensuring that future Android defense systems are better equipped to address these sophisticated, memory-resident threats (Kara, 2023). Secondly, file-based malware, though generally easier to detect, continues to evolve with advanced evasion techniques such as polymorphism, hybridization, encryption, and concealment within the file system (Sheen & Ramalingam, 2015). These adaptations complicate detection efforts. Current malware taxonomies often overlook these critical attributes, posing significant security challenges and limiting the effectiveness of Android malware defenses. The proposed taxonomy addresses this gap by categorizing and analyzing file-based malware features, offering detailed insights into their threat patterns, mechanisms, and evasion strategies.

By integrating features of both fileless and file-based malware, the enhanced taxonomy provides a comprehensive understanding of the diverse techniques malware uses to infiltrate and persist on Android devices. This framework is crucial for improving existing detection methods and advancing the development of robust, future-proof Android malware defense systems.

Threat to validity

In this section, we analyse and discuss the validity threats associated with the research questions (RQs) addressed in this study.

RQ1: What is the study trend over time?

The selection of studies may be subject to bias if certain types are more likely to be indexed or retrieved by the AI-based retrievers. To mitigate this, diverse key terms were defined to extract the most relevant research articles focusing on ML-based Android malware classification techniques. The study selection process involved three refinement steps, conducted collaboratively by multiple authors, to ensure accuracy and relevance. The choice of digital libraries could also affect construct validity if they do not adequately represent all relevant studies. To address this, widely used digital libraries such as ACM Digital Library, Science Direct, IEEE Xplore, and Google Scholar were utilized, as they provide a comprehensive representation of the field. A key external validity threat is that trends observed from January 2018 to October 2024 may not apply to future developments. However, the findings are believed to reflect the current state-of-the-art techniques for software vulnerability detection.

RQ2: What are the Android malware behaviors over time?

The study may face bias due to the timeframe and the dynamic nature of the malware classification landscape. To address this, widely used digital libraries such as ACM Digital Library, ScienceDirect, IEEE Xplore, and Google Scholar were utilized, as they provide a comprehensive representation of the field., and the timeframe was expanded (1900–2024) to capture the evolving landscape of Android malware behaviors comprehensively.

RQ3: What are the malware families based on platforms and infected regions?

Geographical bias may arise as all world regions are not included in this review. To mitigate this, relevant regions representing the global distribution of infections were selected. Additionally, not all malware families were reviewed due to the continuously evolving malware landscape. To address this, popular and dominant malware families were examined to provide a holistic understanding of their behaviors over a prolonged period.

RQ4: What are the limitations of the existing Android taxonomy?

A potential bias exists due to the study’s focus on the Android malware classification landscape. To address this, quality assessments of existing taxonomies from major digital libraries were conducted to ensure global representation, including non-Android smart devices. External validity is also a concern, as trends observed from 2018 to 2024 may not apply to future developments. Nevertheless, the findings are considered representative of current technology for software vulnerability detection.

RQ5: What are the key classifications to enhance the existing Android taxonomy?

Bias might result from focusing solely on Android malware taxonomy. To address this, key classification components were introduced in the enhanced taxonomy to reflect a broader scope of all smart devices. Additionally, the timeline was expanded (2018–2024) to accommodate the evolving Android malware landscape, ensuring a more comprehensive and relevant taxonomy.

Additionally, we also recognize the potential influence of publication bias; where studies reporting significant or positive results are more likely to be published than those with null or negative outcomes. We acknowledge that such biases may be present in the literature reviewed. However, to minimize their impact, we employed an inclusive and balanced selection strategy. Specifically, we incorporated a broad range of literature types, including peer-reviewed journal articles, conference proceedings, book chapters, and certified websites. Additionally, we intentionally avoided restricting our selection to only high-impact or frequently cited studies. This approach was designed to enhance the representativeness of the review and to increase the likelihood of capturing a full spectrum of research outcomes, including both positive and non-significant findings. Database selection bias might exist, but in this review article, we minimize it by using multiple, well-established digital libraries; ACM Digital Library, IEEE Xplore, ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar; which collectively ensure broad and comprehensive coverage of the Android malware research domain. Time-bound search constraints might exist, but in this review article, we minimize them by extending the search timeframe from January 2015 to 2025, and in some cases beyond, to include both historical and the most recent developments in Android malware behaviors and classification.

Conclusions

In this survey, we conducted a systematic review to examine the key characteristics of machine learning (ML)-based Android malware classification studies by addressing five research questions (RQs). We identified and curated relevant studies from four prominent online digital libraries; ACM Digital Library, IEEE Xplore, ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar; filtering out unrelated works. The resulting studies were analyzed in depth to answer the proposed research questions.

For the first research question, we evaluated the publication trends over a seven-year period (2018 to October 2025). The results showed a steady rise in the number of publications, with a significant surge between 2020 and 2025, underscoring the growing importance of ML techniques in Android malware detection. Publication distribution, as illustrated in Figs. 2 and 3, identified Elsevier as the leading contributor.

The second research question focused on the behavioral evolution of malware. We observed a historical shift from simple self-propagating malware (1900–1999) to more advanced techniques like polymorphism, hybridization, and privilege escalation from 2000 onward. Emerging threats such as cryptojacking and click fraud highlighted the increasing sophistication and monetization strategies of modern malware.

For the third research question, global distribution data revealed China, the USA, and Russia as major malware-producing regions, with Android and IoT devices being primary targets due to their security weaknesses. These platforms experienced a surge in attacks characterized by evasive behaviors and complex infection chains.

The fourth research question uncovered limitations in existing Android malware taxonomies. Current models often overlook fileless malware and hybrid attack vectors, both of which are rising in prevalence. Additionally, there is a clear need to better classify cross-platform threats that exploit the interoperability between Android, IoT, and other ecosystems.

To address these gaps, the fifth research question introduced a new Android malware taxonomy designed to capture the full spectrum of evasion techniques, including polymorphic behavior in file-based malware and stealth tactics used by fileless malware. This enhanced taxonomy aims to support the development of adaptive, context-aware defense strategies.

Future research must go beyond Android-specific threats to encompass the broader landscape of interconnected platforms and technologies. This includes integrating advanced ML models; such as federated learning, reinforcement learning, and graph-based learning; to detect malware across devices without compromising user privacy. Furthermore, research should focus on developing multi-layered, context-driven defense architectures capable of real-time threat mitigation. These systems should combine behavioral analysis, dynamic threat intelligence, and anomaly detection at both the device and network levels. Finally, fostering collaboration between academia, industry, and policy makers will be essential to ensure that proposed defense mechanisms remain scalable, explainable, and resilient against emerging, adaptive Android malware threats.