Disease diagnosis in banana leaves: a review on AI powered techniques

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Hazrat Ali

- Subject Areas

- Algorithms and Analysis of Algorithms, Artificial Intelligence, Computer Vision, Data Mining and Machine Learning, Neural Networks

- Keywords

- Disease classification, Machine learning, Deep learning, Image processing, Transfer learning, Banana leaf disease

- Copyright

- © 2025 R and A

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2025. Disease diagnosis in banana leaves: a review on AI powered techniques. PeerJ Computer Science 11:e3310 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3310

Abstract

Banana leaf diseases pose a significant global threat to agricultural productivity and economic stability, substantially reducing the quality and quantity of yield. Given the critical role of banana leaves in the overall growth and development of banana plants, their susceptibility to a wide range of diseases represents a pressing concern. This review systematically explores recent advancements in diagnosing and classifying banana leaf diseases through Artificial Intelligence (AI)-based techniques. Key methodologies reviewed include image preprocessing, machine learning, deep learning, and transfer learning. Particular emphasis is placed on lightweight deep learning architectures, which offer the advantages of high diagnostic accuracy, rapid processing, and minimal computational requirements, making them suitable for deployment in resource-constrained environments. The presence of numerous banana cultivars, each exhibiting subtle variations in leaf morphology and pigmentation, further complicates the detection process, underscoring the need for adaptable and robust AI models. The review also highlights data acquisition, preprocessing strategies, and dataset weaknesses, along with evaluation metrics used to assess model performance. Finally, it identifies existing challenges and research gaps in current approaches with the brief case study by synthesizing these insights. The review provides a comprehensive understanding of AI-powered solutions for the effective detection and classification of banana leaf diseases and their potential practical applications in precision agriculture.

Introduction

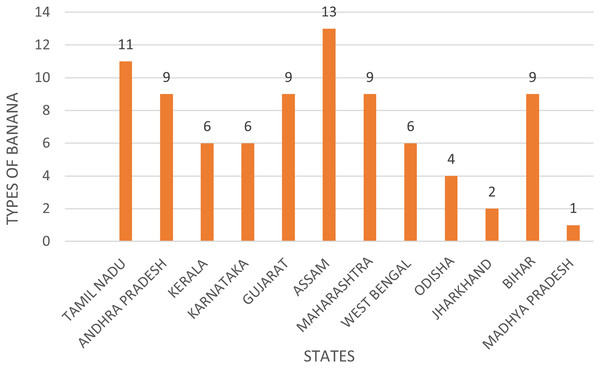

Banana, also called Musa paradisiaca (family Musaceae) (Satyagopal et al., 2014), is the second most cultivated crop in India. It has high export value and is in enormous demand due to its availability throughout the year, affordability, variety, flavor, nutritional value, and health benefits (National Horticulture Board 2015). Banana leaves have various applications, as they are large in size, flexible in nature, waterproof, and decorative. These materials are utilized for various purposes (Nace, 2019) including cooking, wrapping, and serving delicious dishes across diverse cuisines found in tropical and subtropical regions. Not only do they enhance the presentation of food, but they also boast remarkable antibacterial properties, ensuring both safety and freshness in every meal (Prevention Web, 2019). The leaves of bananas vary in size, from 70 cm wide to more than 91 cm in width and from 170 to 261 cm in length. Banana plants can produce approximately 40 leaves in their growing cycle (Docken, 2013). The surface of the leaf may vary, giving different amounts of wax, and being glossy or matte in texture. Both symmetrical and asymmetrical leaf bases and their attachments to the petiole are present. Some banana varieties have a midrib that may be visible red-purple or pink-purple, while others have a green or yellow midrib. The banana leaves have a severely wrinkled, mildly striped, or unridged surface. The world’s top exporters are Ecuador, Colombia, Costa Rica, and the Philippines, while the top importers are the United States, Belgium, Germany, and the United Kingdom (National Horticulture Board 2015). India is estimated to have the largest area under banana cultivation in the world, according to estimates from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). India is the leading exporter, with around 29,558 tons being exported in 2022, worth $12.6 million (Mazumder et al., 2024). Vietnam and Thailand are also the other major exporters. The United Arab Emirates, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia are the major importers of banana leaves. The Harmonized System (HS) Code that is generally used for banana leaves is 07099990. Figure 1 illustrates the varieties of banana plants cultivated throughout India. India accounts for 11 percent of the total global area under bananas. India is at the top in the world production of bananas, with a contribution of around 23% to the world pool of banana production. The majority of banana leaf illnesses are detected manually, usually by farmers who use their wealth of knowledge to assess the condition (Rajalakshmi et al., 2025). Although this is effective, it comes with several shortcomings, especially when it comes to large banana plantations.

Figure 1: Banana varieties grown in India.

Tracking and monitoring a disease over large banana forests is extremely time-consuming to the point of being impractical. Consequently, the disease goes artificially unnoticed during the critical part of its development, resulting in rampant, unchecked infections. Instead, a substantial area of banana leaves is being afflicted, and by that time, there is very little that can be done to save the yield. This exhibits the requirement for additional effective and reliable measures in the automated classification and detection of overt diseases. Table 1 provides information on various banana diseases, including their symptoms and the regions they affect. Managing the disease increases production costs, reduces global market competition, leads to economic losses from lower crop prices, and requires labour-intensive management practices.

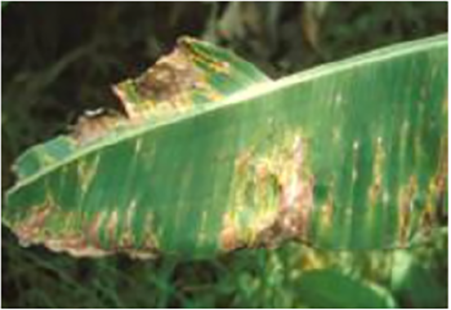

| S. No | Disease name | Image | Symptoms | Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Panama wilt (Indonesia Trade Data, 2025) |  |

Yellowing of lower leaves, including petioles and leaf blades, is one of the first signs | Southeast Asia, Australia, Middle East and South Asia, China, Taiwan |

| 2 | Yellow sigatoka (Satyagopal et al., 2014) |  |

Pale yellow streaks that merge into dark spots with yellow halos, leading to defoliation | Latin America & the Caribbean, Africa, Asia, Australia |

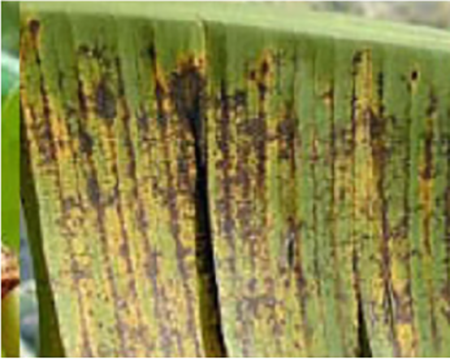

| 3 | Black sigatoka (Marín et al., 2003) |  |

Black spots and streaks on banana leaves | Asia, Africa, the Pacific, and the Americas |

| 4 | Anthracnose (TNAU, 2015) |  |

Large brown areas covered in a red fungal growth | Asia, Africa, South America, Central America, Oceania |

| 5 | Moko disease/bacterial wilt (Boudazin et al., 2004) |  |

Yellowish discoloration of the inner leaf. The suckers’ delicate leaves become necrotic and yellow | Americas Southeast Asia |

| 6 | Bunchy top virus (National Horticulture Board, 2015) |  |

Produce thin, chlorotic leaves with mosaic-like characteristics | Asia, Africa, America, Oceania |

| 7 | Banana streak disease (BSV) (Wikipedia, 2021) |  |

Yellow streaking on the leaves | Africa, South America, Asia |

| 8 | Cordana leaf spot (ProMusa, 2020) |  |

Diamond shape with a yellow border | Oceania, America, Africa, America, Asia |

| 9 | Eumusea leaf (NSW, 2018) |  |

Small, linear, light brown streaks and expand into oval spots with dark brown borders and grey-white centers | Asia, Africa |

| 10 | Xanthonomas (Docken, 2013) |  |

Exhibiting yellowing and collapse of leaves | Africa |

| 11 | Freckle leaf spot (Nace, 2019) |  |

Small brown spots on the leaves | Southeast Asia, Australia, Pacific Islands, South Asia, Africa, Latin America. |

| 12 | Infection chlorosis mosaic disease (National Horticulture Board, 2015) |  |

Mosaic streaking, chlorotic bands, narrow twisted leaves, and rigid, erect new growth | Tropical and Subtropical Regions |

For smallholder farmers, these diseases threaten food security and livelihoods, especially in regions where bananas are a primary food source and income. Control measures are expensive and often ineffective without proper resources. There is a growing demand for banana leaf products, both domestically and internationally (Indonesia Trade Data, 2025). AI-powered tools are rapidly becoming more accessible, offering smallholder farmers the opportunity to leverage these advanced technologies for improved agricultural practices. Many nations have already adopted AI-based solutions and integrated them into farm-level operations for a wide range of applications (Piddubna, 2024). These include agricultural health monitoring, smart irrigation systems, disease detection and analysis, precision positioning of farm equipment, animal health monitoring, automated weed control, drone-assisted aerial surveillance, supply chain optimization, predictive analytics for crop yield estimation (Prevention Web, 2019), market demand forecasting, and the precise distribution of fertilizers and chemicals.

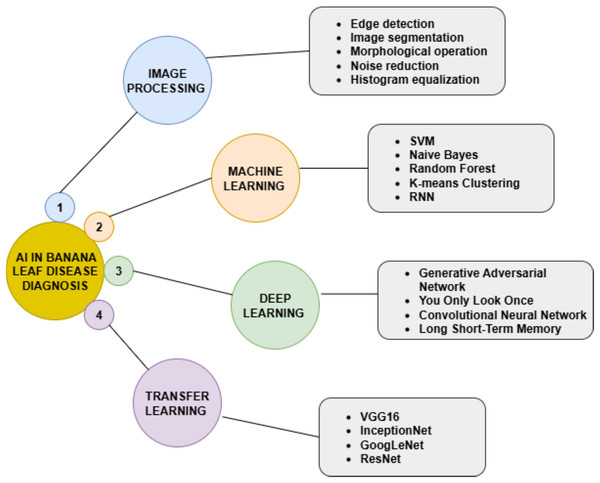

Early detection and classification of banana leaves can reduce the number of dangerous pesticides used for plant protection and growth (National Horticulture Board 2015). For instance, early illness detection and classification may benefit from applying AI techniques, including Deep Learning (DL), Machine Learning (ML), Image Processing (IP), and Transfer Learning (TL).

The following section in the systematic review is presented in the manner outlined below: ‘Review Management’ describes the review management process, including the search approach, the identification and extraction of relevant articles, and the formulation of research questions. ‘Review Reporting’ is the review reporting, which presents the answers to the research questions. ‘Challenges’ describes the primary research challenges and gaps in the existing literature. ‘Case Study: Real World Deployment of Banana Leaf Disease Diagnosis System’ presents the case study on the real-world deployment of the banana leaf disease diagnosis system with a brief discussion. ‘Conclusion and Future Work’ summarizes the conclusions and suggests areas for further research.

Survey methodology

Review management

The study discusses various methodologies used with the aid of an Artificial Intelligence (AI) system to detect and classify diseases in banana plant leaves. Additionally, the study elaborates on the systematic review that was carried out.

The objective of this study is to provide an overview of the detection and classification processes for banana leaf disease. The following are the main key contributions of this review:

This survey focuses on detecting and classifying diseases in banana leaves using IP, ML, DL, and TL techniques, including the model limitations and failure studies

Data gathering processes, data preprocessing methods, and dataset weaknesses are examined.

The performance metrics used for the detection and classification of banana leaf diseases are detailed. The challenges and research gaps in detecting and classifying the banana leaf disease are outlined.

The case study on the real-world deployment of banana leaf disease diagnosis systems is explained.

Searching approach

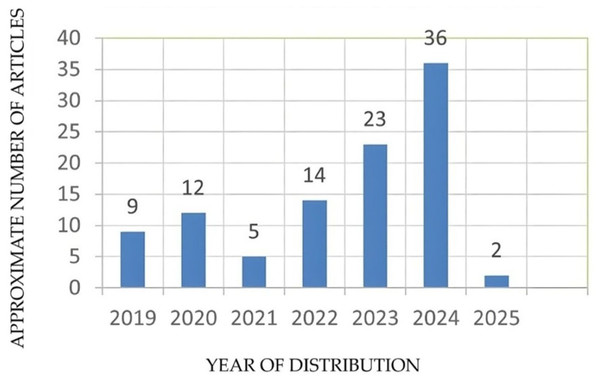

The research articles collected for this work were done under various search queries, such as “Detection of disease from banana leaves based on image processing”, “Early detection of banana leaf diseases using transfer learning”, “Banana leaf disease detection using deep learning”, “Banana crop health monitoring”, “Banana leaf disease classification using AI-based techniques”, “Banana leaf disease diagnosis”, “Disease severity in banana leaf.” “ML-based banana leaf disease diagnosis”, “AI in disease diagnosis”. Additionally, the articles were also sourced from the references cited in the study. Figure 2 illustrates the approximate number of articles collected year-wise.

Figure 2: Year-wise distribution of research articles.

Extraction of articles

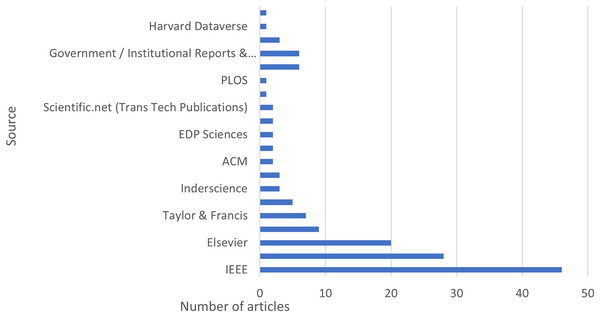

Articles from the scientific repository, including Scopus, Google Scholar, Web of Science, Science Direct, and IEEE from 2019 to 2025, are explored. Figure 3 illustrates the distribution of articles and datasets across different sources.

Figure 3: Distribution of articles and datasets across different sources.

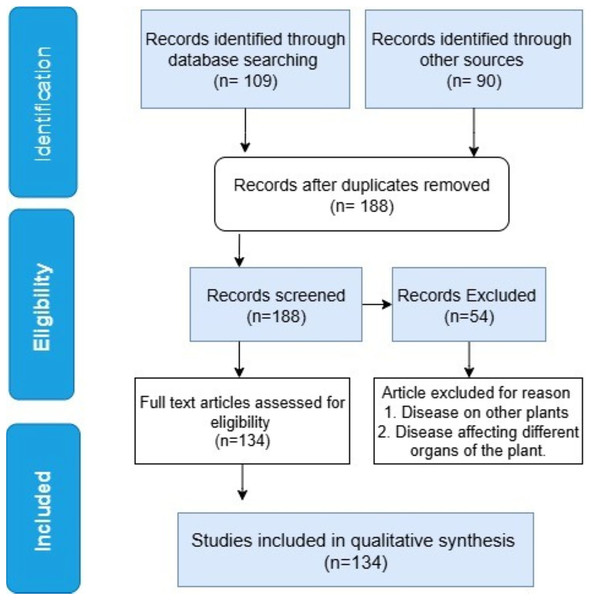

The study selection procedure is depicted in the PRISMA flow diagram in Fig. 4. A total of 90 records were found from other sources, and 109 were found through database searches. Duplicate articles were removed utilizing reference management software (Mendeley/Zotero), along with a manual check. After duplicates removal, 188 records were left for screening. Among those, 54 irrelevant articles were disqualified due to the following reasons: unavailability of a full-text, focus on illnesses that affect different banana plant organs, and other plants. Those articles were removed through a two-stage screening procedure using pre-specified inclusion and exclusion criteria. This process involved title and abstract screening to eliminate irrelevant research, along with a full article review. The qualitative synthesis comprised the remaining 134 full-text articles that met the eligibility requirements.

Figure 4: A PRISMA flow chart of study selection.

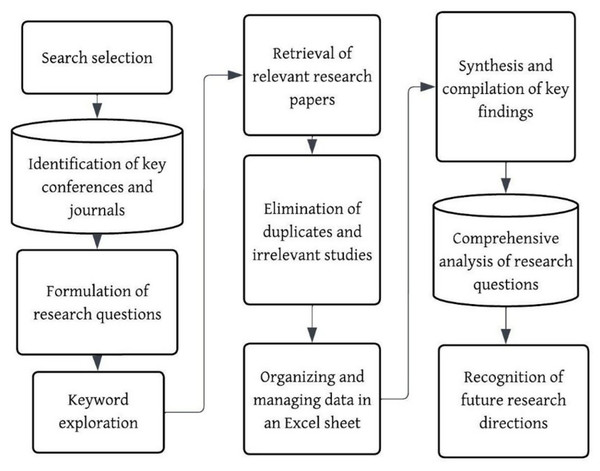

During the selection process, relevant search terms were utilized, and results were filtered based on their peer-reviewed status, relevance, and publication year. The retrieved articles provide various perspectives that contribute to a comprehensive understanding of the topic. Figure 5 illustrates the outline presented in this systematic literature review using a simple flowchart.

Figure 5: Systematic literature review flowchart.

Research questions

In this review, each section was structured to address key research questions related to banana leaf disease detection and classification.

RQ: 1. How can AI-driven techniques empower farmers with actionable insights to mitigate the spread of banana leaf disease before it escalates?

A. How effective is IP in detecting and classifying diseases in banana leaves?

B. How does the practice of using ML models enhance the process of banana leaf disease diagnosis?

C. In what ways does DL add to the complexity of identifying and classifying banana leaf diseases?

D. What kind of impact does TL have on the process of detecting and classifying banana leaf diseases?

E. Discuss the model limitations and failure cases.

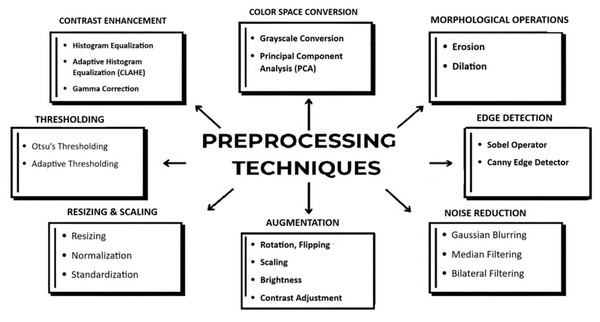

RQ: 2. What type of data preprocessing techniques are applied in detecting and classifying banana leaf disease?

RQ: 3. What are the private and public datasets available? Highlight the public dataset’s weakness?

RQ: 4. What are the devices used for collecting datasets?

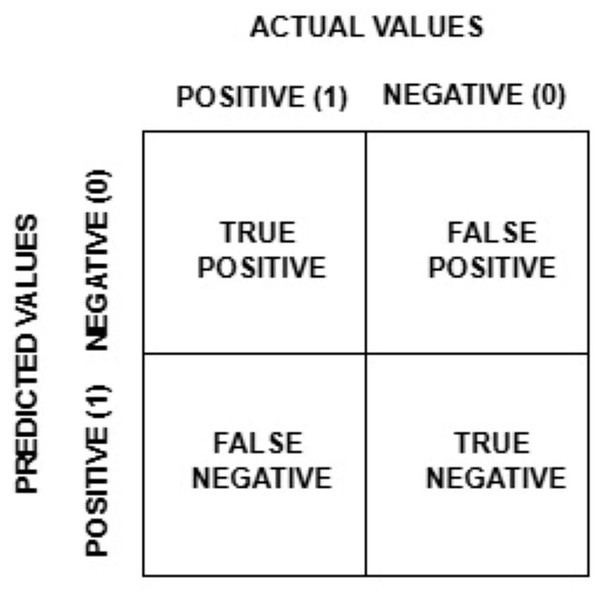

RQ: 5. What are the performance evaluation metrics used for evaluating the models?

Review reporting

Here, there is an answer to all the research questions above by making data-based evaluations and summaries of the contributions made by each of the authors of the studies.

RQ: 1 How can AI-driven techniques empower farmers with actionable insights to mitigate the spread of banana leaf disease before it escalates?

The use of AI in agriculture facilitates early diagnosis, classification, predictive analytics, and targeted management of banana leaf disease. Computer vision and DL algorithms can be used to identify diseases with high accuracy from images of leaves taken with a drone or mobile device (Sanga et al., 2020). By combining satellite imagery and ML models, Decision Support System (DSS) tools produce accurate maps of disease risks, which assist farmers in the correct timing of applying pesticides and practicing optimal farming (Selvaraj et al., 2019). Through improving the containment of diseases while enhancing crop yield, these AI-centered platforms minimize the overuse of chemicals.

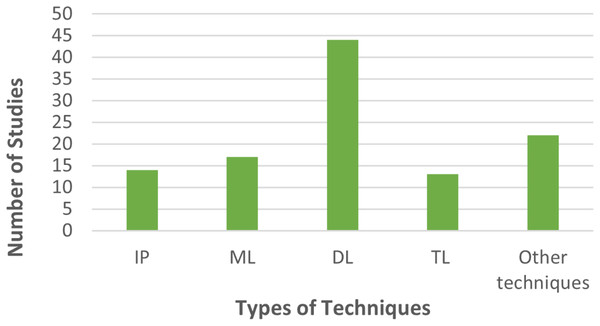

AI promotes sustainable practices by providing suggestions or optimization solutions. Systematically tested designs (Sanga et al., 2020) like ResNet50, InceptionV2, and MobileNet1 for disease detection training have also been suggested. Other studies (Rajagopal & Murugan, 2023) highlighted the success of AI models that comprise ML that automate the detection of four disease categories from a dataset of 1,290 images with an impressive detection accuracy of 80 percent for banana leaf diseases. All this novel research allows farmers to limit losses and improve productivity while adopting environmentally friendly methods. Figure 6 illustrates the breakdown of articles in terms of techniques employed. A robust variant of the modified generative adversarial network (MGAN)-modified faster region convolutional neural network with fuzzy (MGAN-MFRCNN) is proposed (Raja & Rajendran, 2023) for the detection of banana leaf diseases.

Figure 6: Analytical breakdown of studies by approach.

The dataset was collected from southern nations, consisting of 1288 images over three classes: healthy, xanthomonas, and sigatoka. The model attains accuracy, precision, F1-score, specificity, and sensitivity of 98%, 97%, 96%, 98%, and 98%.

The study by Aasha Nandhini et al. (2023) focused on banana leaf disease diagnosis, like bunchy top virus and sigatoka, by taking real-time images, captured from the southern regions of Tamil Nadu along with the ICAR NRCB in Tiruchirappalli, for a dataset of 5,500 images. Foreground-Based Segmentation (FBS) with the combination of oriented FAST and rotated BRIEF feature detection method is proposed for accurate classification of diseases. The proposed device is validated with the help of a temperature sensor, a humidity sensor, a soil moisture sensor, a pH sensor, a camera, and a Raspberry Pi. A mobile application has also been developed to identify the disease category. The accuracy attained for the detection and classification of the banana leaf disease is 96.75% and 97.33%. The author (Ashoka et al., 2024) introduced a novel Explainable AI (XAI) framework designed for disease diagnosis in banana leaves: pestalotiopsis, sigatoka, and fusarium wilt. A convolutional neural network (CNN) is applied to detect diseases utilizing its true color images. The Banana Dataset Tanzania (BDT) consists of images of banana leaves and stems infected with sigatoka and fusarium wilt, as well as healthy samples, also the BLSD dataset comprises images of banana leaves. To obtain high-level features, the EfficientNetB0 model is used. The pre-trained EfficientNetB0 technique was estimated on both datasets. In the BLSD dataset, the performance attained 99.22% accuracy. Furthermore, the model demonstrated improved performance on the BDT dataset, reaching 99.63% accuracy. Using a hybrid method to automatically diagnose diseases in the banana leaves, Thomas & David (2023) combines Ant Colony Optimization to determine feature selection along with CNN to classify the diseased leaf images. The total number of images is 2,825; the data used is already pre-processed through the use of Ant Colony Optimization algorithm. This approach achieves 98.64% accuracy, 98.53% precision, 98.24% recall, and an F1-score of 98.15%. Morphological analysis was applied (Liao et al., 2019) to describe conditions in banana leaf diseases using close-range hyperspectral remote sensing images. Hyperspectral imaging captures detailed spectral information across multiple wavelengths, enabling the detection of nanosecond differences in plant physiology caused by various conditions. This employs morphological IP to examine features such as texture, shape, and spectral characteristics associated with both healthy and diseased banana leaf. Additionally, this research investigates the severity of black sigatoka banana leaf disease. It utilizes climate data and disease incidence records to determine the relationship between changing climate conditions and the spread of the disease. The findings indicate that changes brought about by global warming, particularly elevated temperatures and moisture levels, create an ideal environment for the pathogen involved, thereby increasing the severity of the disease. This in turn, suggests enhanced losses for banana growers. This highlights urgent, time-sensitive issues regarding climate-resilient agricultural practices aimed at mitigating some impacts of climate change on banana farming. In another study (Cárdenas-Rodríguez et al., 2023) computer vision-based systems were designed for automatic detection of black sigatoka disease in banana leaves by combining ML with computer vision techniques for the design of a web and mobile application. The image of banana leaves is captured and recognized, also the treatments are advised. However, for the web application, regular monitoring is maintained. The method was tested in Milagro, Ecuador, with 87% effectiveness in black sigatoka detection at different stages of the disease. Figure 7 represents the AI techniques used in this study. The development of a stochastic model (Varghese et al., 2020) that simulates the spread of banana bunchy top virus in banana plantations is proposed. This model incorporates the randomness of the transmission process of the disease. This study estimates the model parameters without exact likelihood functions, providing a better representation of banana bunchy top virus dynamics. Data collection combines field observations, surveys for monitoring the spread of the disease, and environmental data using temperature and humidity. Here, the author (Ye et al., 2020) developed a method for diagnosing fusarium wilt-infested regions of banana using drone-based multispectral imaging. Two trials were conducted, surveying a total of 120 samples from China, for model fitting and validation. A DJI Phantom 4 quadcopter drone and a multispectral camera like MicaSense, RedEdge MTM were utilized. After analyzing eight vegetation indices (VI), red-edge indices like Chlorophyll Index Red Edge (CIRE) and Normalized Difference Red Edge (NDRE). It demonstrated a high degree of disease diagnosis accuracy. With imaging resolutions greater than 2 m, the highest accuracy was attained, proving the usefulness of drone-based remote sensing for timely plant management and disease monitoring. The study (Zhang et al., 2022) focus on multispectral image-based detection of banana fusarium wilt from an infected banana plantation in July and August 2020. The data was captured by a drone mounted with a camera. Infected canopies had distinctive spectral features: higher reflectance and lower reflectance in the Near Infrared (NIR) range and the visible range. Four supervised methods were used, and two unsupervised methods were used. Random Forest (RF) using five data points from multispectral bands has shown its highest effectiveness for early-stage detection with an accuracy of 97.28%, whereas Hotspot Analysis (HA), based on VIs, showed its effectiveness for late-stage detection. Utilizing VIs from uncrewed aerial vehicle (UAV) imagery, including bands such as Near-Infrared, RGB, and Red-Edge (Choosumrong et al., 2023), the growth of banana plants at 67 sampling points in China. Key indices, specifically TVI, NDRE, and NDVI, demonstrated high accuracy, with a Kappa coefficient of 0.85 for TVI. This analysis offers reliable and timely insights into crop health and management. Hyperspectral imaging is employed in combination with a (PLS–PLR) model for the early detection of black Sigatoka on banana leaves (Ugarte Fajardo et al., 2020). A total of 100 plants, grown for 3–4 months in the greenhouse, were taken to Ecuador for inoculation with the black sigatoka fungus, after which hyperspectral data covering the wavelengths ranging from 386 to 1,019 nanometers were measured. The Partial Least Squares–Partial Logistic Regression (PLS-PLR) model achieved an accuracy of 98%. The primary wavelengths for classification fell within the ranges of 577 to 651 nm and 700 to 1,019 nm defines a federated learning framework using CNN to detect five diseases, namely black sigatoka, yellow sigatoka, fusarium wilt, banana bunchy top virus, and moko disease of banana leaf. It ensures privacy in the federated averaging-based approach to building an effective global model. Its accuracy is remarkable at 96–97%. Tight results are obtained on precision, recall, and F1-score.

Figure 7: AI techniques for banana leaf disease diagnosis.

Federated Learning with CNN for disease detection in banana leaves belonging to different agro-climatic regions is explored by Sharma et al. (2023). The system classified diseases into four types based on severity, using the CNN model. The model provides high performance with accuracy ranging from 84.59% to 94.87%, recall ranging from 84.87% to94.84%, and F1-scores ranging between 84.66% and 94.86%. It indicates that the scalability support values are robust, hence an overall accuracy ranging between 92% and 97%. The federated averaging method gives macro-average, weighted average, and micro-average performance metrics, all of which range between 84.71% and 94.86%. Federated Learning allowed all clients to achieve high levels of precision, recall, and accuracy in disease classification (Suryavanshi et al., 2024). The model’s performance showed strong consistency across various averaging methods, with a macro average reaching 92.04%. By employing federated averaging to transform local data into a global model, this study illustrates the potential of federated learning in agriculture. Shukla et al. (2024) describes a three-class leaf disease classification technique using the architecture of CNN within federated learning to classify into four severity classes. Four data centers as stakeholders participated in collaborative learning, and results showed efficacy in several agricultural domains. The model has excellent accuracy for disease classification, with accuracy ranging from 92.74% to 96.22%. The author (Fajardo et al., 2022) examines the application of distributed edge intelligence for the early detection of black sigatoka disease using hyperspectral imaging. ML models, including support vector machine (SVM), Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), neural networks, N-way partial least square–discriminant analysis (NPLS-DA), and PLS-PLR, were trained on hyperspectral images of infected banana leaves. The images were captured from the ImSpector V10E hyperspectral scanner. Evaluation metrics showed that PLS-PLR, SVM, and MLP achieved high accuracy. The research (Bebber, 2019) examines how fast climate change affects the infection risk of black sigatoka, a major banana disease, in Latin America and the Caribbean. Using a mechanistic modeling approach, the authors developed infection risk models based on experimental data, hourly climate records from the Japanese 55-year Reanalysis (JRA55), and banana distribution data from the Spatial Production Allocation Model (SPAM), and simulations involving temperature and leaf wetness from 1958 to 2017. Increases in temperature raised the infection risk by 44.2% in areas like Ecuador and Brazil. The study aims to differentiate climate impacts from trade and host spread. Limitations include sparse observational data and biases in climate data. Infection risk varied spatially and temporally, decreasing in regions like Guatemala and Honduras due to drying trends, and also examining the black sigatoka disease, caused by Mycosphaerella fijiensis, which can reduce banana yields by up to 50%. It highlights the rapid fungicide resistance, particularly to propiconazole, and the absence of resistant cultivars like Cavendish. Control efforts account for 27% of production costs, with current methods proving largely ineffective.

The study (Escudero, Calvo & Bejarano, 2022) presents a LeNet-based CNN with a Decision Tree (DT) for detecting black sigatoka disease in banana leaves. Using a custom dataset with 96 × 96 image segments, the model achieved 90.03% accuracy, outperforming SVM and Inception-v3 despite challenges like limited data and class overlap. A mobile application that assists in the classification of images was developed by Escudero et al. (2021). The authors created a system using Ensemble Boosted Trees to classify black sigatoka disease in Plantain crops, achieving 82.02% accuracy in field tests. An easy-to-use Android app was developed for farmers in Colombia. Mora et al. (2025) examined ML techniques for early detection of black sigatoka disease in banana plants using hyperspectral imaging. A dataset of 16 plants was analyzed using various models, achieving high accuracy with SVM and MLP. Challenges included data dimensionality and class imbalance, but the results showed effective non-invasive detection.

The review (Soares et al., 2021) on banana genetic improvement for black igatoka resistance highlighted 24 studies (2010–2020) focusing on resistant genotypes like Calcutta 4 and cultivars such as Brazilian cultivar developed by Embrapa (BRS Maravilha) and Hybrid cultivar developed by FHIA in Honduras (FHIA-02). Key research areas included gene expression, enzyme activity, and transgenic development. Resistance was linked to jasmonic acid and antioxidant pathways. Challenges include incomplete gene validation and the complexity of breeding. The study emphasizes the importance of Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)/ CRISPR-associated protein 9, an endonuclease enzyme that cuts DNA at a targeted location (Cas9) and integrated breeding for effective management. In other study (Elinisa et al., 2025) develops a U-Net DL framework for detecting fusarium wilt and black sigatoka in banana plants. Utilizing 18,240 annotated images from Tanzania, the model was trained using data augmentation and achieved a dice score of 96.45% and an IoU of 93.23%. The findings indicate effective segmentation of diseased areas, supporting early disease management in banana farming.

How effective is IP in detecting and classifying diseases in banana leaves?

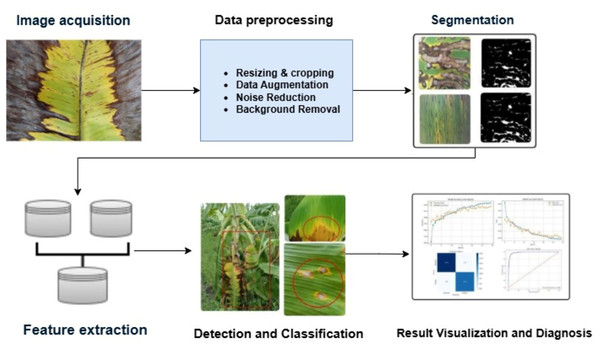

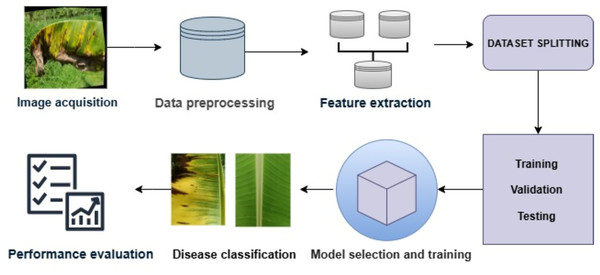

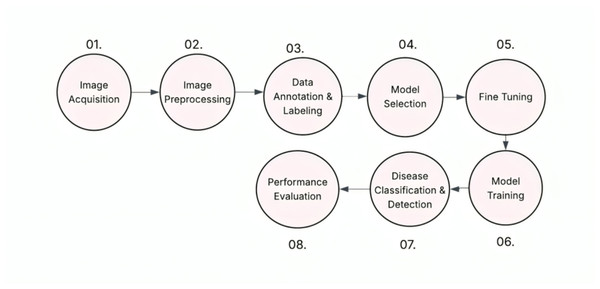

In Jianqing et al. (2022a) an image processing technique was demonstrated to identify sigatoka and banana gray leaf spot. The technique retrieved color features using color segmentation, YUV conversion (Y-Luminance, U-Blue chrominance, V-Red chrominance), and Otsu thresholding. Using a Euclidean distance classifier, it obtained 90% accuracy for sigatoka and 91.7% accuracy for gray leaf spot. Jianqing et al. (2022a) proposed a method for segmenting images that combines an area threshold approach, Otsu segmentation, and color segmentation. This approach processes the RGB images that comprise the U component using an “AND” operation. With a private image dataset of banana leaf disease, the method achieved a 2.3% error rate and 97% segmentation accuracy. Correa et al. (2021) utilized an IP method for diagnosing the diseases in banana leaves. The images of both infected and non-infected leaves with conditions like bacterial wilt and black sigatoka were taken from a public source. The research covers the areas of segmentation, the Otsu method, histogram equalization, masking, and classification. The model achieved a recognition rate of 96.26% using the techniques. Deenan, Janakiraman & Nagachandrabose (2020) used various image segmentation algorithms, including grayscale conversion, image smoothing, local gradient operator, and edge localization. The outcomes of these algorithms were also computed based on Mean squared Error (MSE), Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR), and Structural Similarity Index (SSIM). The diseases found are the pseudostem borer, panama disease, yellow sigatoka, rhizome rot, banana bract mosaic virus, and banana bunchy top virus. Figure 8 determines the workflow of IP techniques.

Figure 8: Workflow of banana leaf disease detection and classification using IP.

The study (Prabhakar & Sudha, 2024) proposes a filtering algorithm for disease detection in banana plant leaves. This involves many pre-processing methods, various segmentation techniques, and different feature extraction methods. The filtering algorithms used on the images are the Canny filtering algorithm, the Prewitt filtering algorithm, and the Roberts filtering algorithm. Other IP tools applied to the study are MATLAB and Python. The diseases focused are cordana, sigatoka, and pestalotiopsis.

Bhamare & Kulkarni (2013) concentrated on identifying the black sigatoka disease in banana trees through IP methods. The captured images underwent processing using Laplacian, median filtering, Gaussian, and linear. Image pre-processing involves operations like resizing, filtering, segmentation, and morphological transformations. Furthermore, for object extraction, techniques such as background subtraction, filtering, and segmentation were utilized. The study compared (Abisha & Bharathi, 2023) several models for image segmentation, including morphological transformation, contour detection, sobel filtering, k-means clustering, edge detection, canny edge detection, and thresholding, to determine the best technique. A collection of 1,600 images, such as those from the Plant Village dataset, was used for this analysis. Additionally, Gaussian blur was employed as a technique in IP. The results achieved were an RMSE value of 0.0013, a PSNR value of 57.41, and an SSIM value of 0.9982. Research by Patil et al. (2024) introduced an image-processing method for identifying the leaves of banana plants. Diseased leaves like xanthomonas, fusarium, and sigatoka were gathered. Features were extracted using multiple layers of CNN. Additionally, an Android app was also developed to help the farmers. The study referenced in Ibarra, Rivera & Manlises (2023a) examines the proportion of leaf degeneration in banana leaves affected by Panama disease. It utilizes color space transformations and OpenCV tools to segment and analyze images of the leaves. Through image processing, this method quantifies the extent of degradation by calculating the percentage of diseased areas. The researcher (Lin et al., 2021) introduces EM-ERNet, a new neural network specifically designed for banana disease recognition. The network is built on the ResNet backbone and uses dilated and multi-scale convolutions to enhance feature extraction. Innovations include batch normalization and a fusion mechanism powered by an optimized Extreme Learning Machine (ELM) algorithm. The method achieved high accuracy rates of up to 96.39% for the different banana diseases, and with faster processing times than in traditional models such as ResNet50. Non-Subsampled Dual-Tree Quaternion Wavelet Transform (NDQWT) in tandem with an Neighborhood Threshold Pattern (NTP) to classify banana leaf diseases is applied (Mathew, Kumar & Cherian, 2023a). In NDQWT, features were extracted while retaining direction and spatial form after local textures were recorded via NTP. The suggestion is that this technique will improve the accuracy of diagnosing different neglects of banana leaves. The study by Elinisa et al. (2025) address diseases like fusarium wilt and black sigatoka by utilizing 18,240 photographs of banana leaves and stalks taken by mobile phone cameras (Elinisa et al., 2025). The model uses the CNN architecture for the U-Net to segment images of banana plants to mark infected regions for early diagnosis. The U-Net model achieved a dice coefficient of 96.45% and IoU of 93.23%. The study by Mahendran & Seetharaman (2022) used Gray-Level Co-occurrence Matrix (GLCM) for texture feature extraction and classification utilizing Deep CNN. The dataset consists of 10 samples collected from a prehistoric cultivation field. Table 2 provides an overview of IP.

| Ref | Methodology | Dataset | Diseases | Performance matrix | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jianqing et al. (2022b) | Otsu segmentation, | 100 images, Hainan University’s Danzhou campus, China. | Gray leaf spot. sigatoka leaf spot. | Accuracy Sigatoka: 90.0% Grey leaf spot: 91.7% |

||

| Jianqing et al. (2022a) | Otsu segmentation, threshold method, | 100 images, Hainan University’s Danzhou campus, China. | Gray leaf spot disease and sigatoka leaf spot disease | Accuracy: 97% error rates: 2.3%, |

||

| Deenan, Janakiraman & Nagachandrabose (2020) | Edge localization, local gradient operator, image smoothing, and grayscale conversion. | 150 images from Sirumugai village, Coimbatore District | Pseudostem borer, Panama disease, yellow sigatoka, rhizome rot, banana brack mosaic virus, and bunchy top virus. | MSE: 6,610, PSNR: 6,608 |

||

| Patil et al. (2024) | LeNet architecture | 3 image classes of diseased leaves were gathered in different lighting conditions. | Xanthomonas, Fusarium, and Sigatoka | Precision score: 93% Recall score: 93% F1 value: 93% |

||

| Abisha & Bharathi (2023) | Thresholding, Morphological Transformation, Canny edge detection, Contour detection, Sobel | 1,600 banana leaf images from kaggle combined with banana leaf disease dataset (Medhi & Deb, 2022) | The diseases are only segmented not classified. | RMSE value 0.0013, PSNR value 57.41, SSIM value 0.9982 |

||

| Correa et al. (2021) | Otsu method, histogram equalization, masking, and classification. | GitHub repository, with 623 images. | Bacterial wilt, black sigatoka, | Accuracy: 96.26% | ||

| Elinisa et al. (2025) | U-Net semantic segmentation | 18,240 banana leaves using Samsung SMA715F/DS phone cameras | Fusarium Wilt and Black Sigatoka | Dice Coefficient of 96.45% and an Intersection over Union of 93.23%. | ||

| Prabhakar & Sudha (2024) | Canny filtering, Prewitt filtering, and Roberts filtering algorithms. | Prehistoric data were collected from which 10 samples were utilized. | Cordana, Sigatoka, and Pestalotiopsis | Sigatoka | ||

| Canny | 82.8 | 28.9 | ||||

| Robert | 97.5 | 28.2 | ||||

| Prewitt | 98.3 | 28.2 | ||||

| Pestalotiopsis | ||||||

| Canny | 81.3 | 29.05 | ||||

| Robert | 98.5 | 29.05 | ||||

| Prewitt | 98.2 | 28.2 | ||||

| Cordana | ||||||

| Canny | 86.3 | 28.8 | ||||

| Robert | 98.8 | 28.2 | ||||

| Prewitt | 96.8 | 28.3 | ||||

| Lin et al. (2021) | ELM algorithm, multi-scale convolutions, ResNet | Both private and public datasets. | Black Sigatoka, Yellow Sigatoka, and Pestalotiopsis | Accuracy: 96.39% | ||

| Liao et al. (2019) | Morphological image processing (MIP). | Hyperspectral remote sensing images. | Disease is not classified. | Accuracy: >80% | ||

How does the practice of using ML models enhance the process of banana leaf disease diagnosis?

In 2020 Selvaraj et al. (2020), used UAV and multispectral satellite imagery for banana classification based on pixels. Using the MicaSense RedEdge multi-spectral camera and the Pix4Dcapture app, UAV-RGB (Red Green, Blue) photos were obtained for the localization of bananas and disease diagnosis. DL models such as RetinaNet and ResNet are used to locate and identify banana plants. The accuracy of the performance metric was 97%, while the recall results were 0.99, 0.95, 0.92, and 0.90. Three distinct models for diagnosing illnesses in banana leaves are shown by Vidhya & Priya (2022) utilizing both DL techniques, Alexnet, and ML techniques, K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) and SVM. In particular, sigatoka and leafspot is manily focused on this study. A total of 12,544 images using basic photography equipment, photographs of banana leaves were taken from different banana fields in Kerala, India. These include augmentation methods, including clipping, zooming, and rotation. It yields an accuracy level of 96.73% with AlexNet, 84.86% with SVM, and 76.49% with KNN. Figure 9 explains the workflow of banana leaf diagnosis using ML.

Figure 9: Workflow of banana leaf disease diagnosis using ML.

The study by Chaudhari & Patil (2020) exhibited the design of a SVM classifier to identify banana leaf diseases by visualizing the symptoms, especially focusing on sigatoka, cucumber mosaic virus, bacterial wilt, and panama diseases. A digital camera has been utilized for capturing images. Preprocessing techniques for denoise removal was utilized. K-means clustering is used during the segmentation process in identifying the diseased regions while feature extraction, colors, shapes, texture features are extracted to classify the type of disease and those texture features are evaluated by the GLCM. It is shown the classification of the four classes of diseases is correct in 85% of cases. The author (Freire et al., 2023) targeted detection of sigatoka disease on the banana foliage and proposed a method integrating CNNs with Shapley values for developing an explainable diagnostic system for banana leaf sigatoka disease. The dataset contains 155 images of healthy plants, 320 images infected with sigatoka, and 814 images infected with xanthomonas. The SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) SHAP VGG 16 model was found to be working better than other models. The study by Saranya et al. (2020) presented a system that utilizes image processing techniques to detect illnesses early, along with an artificial neural network (ANN) algorithm for classification. The process begins with pre-processing techniques, such as scaling and filtering, including both high-pass and low-pass filters. Ten fruit and leaf samples are used for disease detection. Segmentation methods, such as fuzzy c-means clustering and thresholding, are employed. The diseases targeted in this study include black Sigatoka, freckle-affected leaves, and anthracnose-affected fruits. Yathurshan et al. (2023) introduces “Leaf Guard” a Smartphone application designed especially for the agricultural environment in Sri Lanka, aimed at detecting diseases in the banana crop and treating the same. In this, field visits, agricultural journal records, and expert talks were used to collect 6,000 pictures of leaves of banana plant. Pictures were resized before processing the images using Histogram-based feature extraction methods. In this application, Xanthomonas and Sigatoka- related issues are dealt. It provides a cure percentage analysis along with a chemical suggestion system. More than 95% accuracy was achieved in total. The article reviews (Raja & Rajendran, 2022) banana leaf disease detection methods, highlighting that traditional ML models like SVM, KNN, and ANN achieve around 89–98% accuracy but rely on manual feature extraction and struggle with complex images. In contrast, DL models (CNN, DCNN, MobileNet, LeNet) automatically learn features and perform better, reaching up to 99% accuracy even under variations in lighting, scale, and background. The study emphasizes that DL is the most reliable approach for early, automated, and real-time detection, though challenges remain in terms of limited datasets, detection of tiny symptoms, and lack of severity estimation.

Thiagarajan et al. (2024) analyzed banana plant health using image capturing and preprocessing. It employed k-means clustering for segmentation and used SVM and CNN for classification, focusing on diseases like panama wilt and black sigatoka. A filtering method is proposed by Prabhakar & Sudha (2024) for the detection of illnesses in the leaves of banana plants. Numerous preprocessing approaches, multiple segmentation strategies, and numerous feature extraction strategies are all used. Three different filtering algorithms were applied to the images: the Roberts, Prewitt, and Canny filters. MATLAB and Python are two other image-processing tools used in the study. This article discusses three diseases: pestalotiopsis, sigatoka, and cordana. However Pai, Naik & BR (2020) introduced a method of detecting banana leaf diseases with a combination of a CNN algorithm with an ML model. There are four disease types with 1,200 images used here. The web interface allows users to upload an image, and the application will identify the type of disease present. In this study, a method for detecting sigatoka disease in banana leaves was proposed (Tuazon, Duran & Villaverde, 2021). A total of fifty banana leaves affected by the disease were collected, and each leaf was photographed twice and subsequently stitched together. To eliminate the background, Otsu’s thresholding technique was applied. A confusion matrix was then utilized to analyze the gathered data, resulting in an accuracy of 96.15%. Aruraj et al. (2019) introduces a method to identify and classify diseases on banana plants using texture patterns. The uses two steps approach such as texture feature extraction with Local Binary Patterns (LBP) and disease classification with SVM and KNN. The technique was tested on the public dataset, which included two cases: healthy and black sigatoka and healthy and cordana leaf spot. In total, 123 images were collected. The SVM classifier had an accuracy of 89.1% and 90.9%.

A method of disease recognition for banana leaves by using LBP along with GLCM was presented for extracting features (Chaudhari, Dawoodi & Patil, 2022). These methods contrast with color-based feature extraction techniques and use SVM and K-NN classifiers. They diagnose diseases such as banana yellow sigatoka, bunchy top, and cucumber mosaic virus. Digital cameras, as well as smartphones, were used for capturing images in a natural agricultural environment. Here Mary, Singh & Athisayamani (2021) automatically classifying banana leaf diseases through Gabor feature descriptors technique is proposed. It uses Gabor filters to extract texture features from images of diseased banana leaves, which will then be analyzed and classified by ML algorithms.

The Compared ShuffleNet V2 CNN model was compared with SVM and KNN for image classification of the black Sigatoka infection in banana leaves is proposed (Yumang et al., 2023). Gathering samples from 30 healthy leaves and 30 black sigatoka-infected leaves. This CNN model gave 95% accuracy in classifying raw and augmented images obtaining 96.67% sensitivity rate and 93.33% specificity rate. The model was deployed on a Raspberry Pi prototype for testing, and its performance was tested against SVM and KNN; it proved to be effective in anomaly detection in agriculture.

In Syihad et al. (2023) CNNs and ML are used to classify banana plant illnesses based on images of the leaves. The VGG-19 and ResNet50 models are utilized, with the former achieving 91% accuracy, 88% precision, 91% recall, and 89% F1-score. The dataset comprises 936 photos. Banana leaves are classified into four groups: pestalotiopsis, sigatoka, cordana, and healthy. This dataset was sourced from the Kaggle website.

The proposed system (Chaudhari & Patil, 2023) uses ML to detect diseases in banana leaves, which involves image acquisition, preprocessing (contrast stretching and filtering), and picture segmentation using a genetic algorithm. Features are extracted using LBP. The technique utilizes the strength of several classifiers by combining their outputs using an ensemble method and applying a genetic algorithm for segmentation in a new way. The images were taken with 48 MP cameras on mobile phones. The image is 640 × 480 pixels in size. The ensemble model outperformed single classifiers like SVM, Naïve Bayes, and others with an accuracy of over 92%.

In Nayak et al. (2024) the RF-XG-ResNet50 ensemble DL classifier is introduced to automate banana leaf disease classification with a hybrid architecture, where an ensemble multi-architecture is combined to enhance the accuracy. Data augmentation has been used for better training and generalization. It has been tested with an accuracy of 95% against DT and SVM. The Kaggle public dataset is used for training. Table 3 explains the overview of ML-based techniques.

| Ref | Methodology | Dataset | Diseases | Performance matrix |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selvaraj et al. (2020) | RetinaNet, ResNet, CNN model |

UAV-MS images, captured using a MicaSense RedEdge multispectral camera with, Pix4Dcapture app. |

Xanthomonas Wilt and Bunchy Top Disease | Accuracy: 97% Recall: 92% Precision: 99 % |

| Saranya et al. (2020) | ANN algorithm, fuzzy c means clustering, thresholding method. | Private dataset of 60 images captured using digital camaras. | Black sigatoka, freckle and anthracnose | Accuracy: 96–97% |

| Tuazon, Duran & Villaverde (2021) | k-means clustering thresholding, HOG, SIFT |

Gathered diseased images by field survey. | Panama wilt, Bract Mosaic, Black Sigatoka, Bunchy virus, Banana bunchy top virus, Banana Streak, and Infectious Chlorosis. | Accuracy: 95% |

| Yathurshan et al. (2023) | Histogram based feature extraction techniques | 6,000 images, filed surveys. | Sigatoka and xanthomonas | Accuracy: 95% |

| Vidhya & Priya (2022) | KNN, SVM, Alexnet, K-KNN, SVM | 12,544 images using camera, Krishibhavan, Kazhakuttam, Trivandrum, Kerala, India. | Leafspot and Sigatoka | Accuracy: 76.49% |

| Chaudhari & Patil (2020) | SVM, K-means clustering, GLCM. | Field dataset using digital camera. | Bacterial wilt, Panama, sigatoka, cucumber mosaic virus | Accuracy: 85% |

| Yumang et al. (2023) | ShuffleNet V2 CNN, SVM, KNN |

Thirty samples of healthy and infected with Black Sigatoka. | Black Sigatoka | Accuracy: 95%, sensitivity: 96.67%, specificity: 93.33% |

| Raja & Rajendran (2022) | KNN, SVM, ANFI, and ANN | Private dataset, Images were captured using digital cameras. | Panama wilt, black sigatoka, bunchy top virus,streak disease, and Bacterial Wilt | Precision: 90% |

| Syihad et al. (2023) | ML with CNNs, ResNet50 and VGG-19 | Public dataset Kaggle website | Cordana, Sigatoka, and Pestalotiopsis | ResNet50 Accuracy: 94% recall: 91%precision: 88% VGG-19 accuracy: 91% F1-score: 89%, |

| Nayak et al. (2024) | RF-XG-ResNet50 ensemble DL, (DT) and SVM | Kaggle public dataset | Disease not classified | Accuracy: 95%. |

| Chaudhari & Patil (2023) | ML technique, genetic algorithm, local binary pattern, SVM, Naïve Bayes | Mobile phone camera with 48 MP resolution using 640 × 480 image size. | Streak virus, black and yellow sigatoks, cucumber mosaic virus, bunchy top virus, pitting | Accuracy: 92% |

In what ways does DL add to the complexity of identifying and classifying banana leaf diseases?

This method employs image segmentation to automatically detect diseases in banana plant leaves. It utilizes a collection of 9,000 images from the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT) banana image library to identify Black Sigatoka, Yellow Sigatoka, banana bacterial wilt, and healthy plants through the integration of hybrid fuzzy C-means clustering. For the preprocessing stage, median filtering and image resizing were applied. The Total Generalized Variation Fuzzy C-means clustering (TGVFCM) technique merges fuzzy C-means with Total Generalized Variation for effective segmentation. The TGVFCM, combined with a CNN, achieved an accuracy of 93.45%, specificity of 96.38%, and sensitivity of 89.04% is addressed (Gokula Krishnan et al., 2022). The study by Narayanan et al. (2022) used a hybrid CNN to identify illnesses in banana plant leaves. The dataset, collected from Tamil Nadu and the Tamil Nadu-Kerala border, comprised 3,500 images of healthy and damaged banana plants. Pre-processing techniques included median, low-pass, and high-pass filtering. SVM served as the classifier, while CNN was used for feature extraction.

The study (Ridhovan, Suharso & Rozikin, 2022) used 936 images of healthy and disease-infected banana leaves from the Kaggle website, collected by the remote sensing lab using a smartphone camera. Data preprocessing involved under-sampling, over-sampling, and data augmentation. DenseNet and Inception techniques were applied, achieving an F1-score of 84.62%, a recall of 84.73%, an accuracy of 84.73%, and a precision of 84.80%. Seetharaman & Mahendran (2022) developed an image-processing method for diagnosing diseases in banana leaves using 1,875 images from online and Indian farms. Pre-processed images were segmented, and features were extracted using Gabor-based patterns and a convolutional recurrent neural network (CRNN). The CRNN-RCNN model achieved a 98% accuracy, outperforming DCNN (88.9%), SVM (92.63%), KNN (79.56%), and CNN (87.6%).

Unveiled a novel agro-DL model (Sangeetha et al., 2023) aimed at recognizing the panama wilt disease. Utilized a set of 1,000 JPEG images. Pre-processing included rescaling and transforming the image. For segmentation, max pooling was implemented, for augmentation process cropping, flipping, rotating, and zooming the images was used. The proposed method attained a recall of 88.56%, an accuracy of 91.56%, a precision of 91.61%, and an F1-score of 81.56%. CNN architecture was presented (Bhuiyan et al., 2023) that has been improved using Bayesian optimization called BananaSqueezeNet. This architecture can identify three types of diseases in banana leaves. Moreover, the model can diagnose diseases affecting banana plants. A smartphone application was also developed for the identification of diseases. Data was collected from the experimental field as well as from various banana fields in Bangladesh. The 937 pictures have four categories: cordana, sigatoka, pestalotiopsis leaf blight disease, and healthy leaves. Augmentation techniques, including the Gaussian blur, horizontal flipping, image cropping, linear contrast modification, shearing, translation, and rotation, were used to address the problem of unbalanced data. CNN was used in the classification process. There were two different types of layers in the CNN: feature extraction layers and classification layers. The neural networks that use Bayesian optimization like SqueezeNet, MobileNets, EfficientNets, and ResNet, are used for image classification and object detection tasks. With a recall of 96.25%, precision of 96.53%, F1-score of 96.17%, specificity of 98.75%, and MCC of 95.13%, the model attains an overall accuracy of 96.25%.

The Ghost ResNeSt-Attention RReLU-Swish Net, based on ResNet50, Deng et al. (2024) uses a dataset of 13,021 banana leaf images to detect diseases. It achieved high detection rates: 96.42% for Sigatoka, 97.54% for cordana, and 95.58% for pestalotiopsis, with an overall accuracy of 98.38%. An application for smartphones for the identification of diseases in banana leaves, like fusarium wilt and black sigatoka, is outlined by Elinisa & Mduma (2024a). The 27,360 pictures were divided into three groups: black sigatoka, fusarium wilt, and healthy banana leaves. Mobile cameras were used to gather this image dataset from Tanzania. The programs VisiPics and Duplicate Photo Finder were utilized to identify and eliminate duplicate photos. In a matter of seconds, the suggested program could accurately detect duplicate images with 90% accuracy.

The study by Mathew, Kumar & Cherian (2023b) developed an automated approach by DL for classifying three major banana leaf spots: sigatoka, cordana, and deightonella. A Canon EOS 750D camera captures photography at the farms at Kerala Agricultural University (KAU). The third author, being a plant pathologist, supervised the data collection and labeling processes. The accuracy attained for DenseNet 121 was 91.7%.

This study (Banerjee et al., 2023) combined a mixture of CNN and SVM to help in disease diagnosis on banana fruit leaves. Using the photographs from both primary and secondary sources, the authors created a dataset of 1,100 images, which fall into four groups. The preprocessing steps come denoising and feature extraction using CNN, followed by disease classification of the leaves in SVM. This hybrid approach of CNN and SVM achieves performance accuracy of 94%. Authors in Tanwar, Sharma & Aanand (2023) used CNN and SVM techniques in network technology for the purpose of banana fruit leaf disease detection. It has utilized a big real-world data set of 1,100 images gathered from farms and online repositories. It targeted three types of banana disease: black sigatoka, cordana, and speckle disease. These types of disease classification were achieved by using SVM. The implemented methodology reached an accuracy across four different experimental scenarios of 90%, 95%, 89%, and 88%

An eight convolutional layered DCNN was proposed (Devi et al., 2022) to predict banana leaf disease. The public dataset Kaggle ML repository was utilized, consisting of 937 photos from the cordana, healthy, pestalotiopsis, and sigatoka disease categories. The training dataset was used by eight convolutional layered DCNNs. The same dataset was tested on models including MobileNetV2, DenseNet201, VGG19Net, InceptionV3Net, ResNet152, and NASNet. Large to determine performance metrics. 98.75% accuracy, 98.75% recall, 96.42% precision, and a 97.57% F1-score were attained.

In Singh, Guleria & Sharma (2024) was developed and deployed a CNN model that will identify and locate the banana leaves in images accurately. The images of bananas were collected from the online Kaggle repository. Preprocessing techniques like scaling, normalization, and augmentation were utillzed, and the model has convolutional layers to extract the features accurately and classify them. This method accurately determines diseases in banana leaves correctly for a success rate of 98.24% for 20 epochs.

The study by Bharathi Raja & Rajendran (2023) discusses a TL approach that incorporates a Faster R-CNN to support detection. The method uses all three different architectures: ResNet 50, InceptionV2, and MobileNet1. Haq et al. (2024) proposed a hybrid DL architecture named DenseMobilenetV2 that integrates the strong and reliable architecture of DenseNet121 with the efficient and accurate MobilenetV2. Data were gathered from Bangladesh, which consist of JPG images of 937 bananas, including samples of those infected by sigatoka, cordana, pestalotiopsis, and healthy samples. Color inversion, along with the data augmentation technique, has been used in pre-processing. The method adopted for using an outlier has been the IQR. And, the precision accuracy score generated was 100% on the model. F1-scores, along with recall accuracy, scored 0.9987 and 0.9974, respectively; those have been considered the optimum scores.

Faster RCNN, accompanied by Mohanraj et al. (2023) region proposal network in the detection of diseases for banana leaves. CNN has been used to extract feature extraction. The dataset for the research was sourced online through the website Kaggle.com. It contained both publicly available images and real-life photos. The diseases present are bacterial wilt, sigatoka, and pestalotiopsis. In addition, techniques involving image scaling and augmentation, like flipping, rotation, cropping, as well as scaling, are used. The accuracy reached was 0.9463.

The study by Sanga et al. (2020) developed a mobile application that uses five DL architecture models: Resnet18, Resnet152, Vgg16, Resnet50, and InceptionV3 are intended to detect illnesses in banana leaves. To implement the mobile version of this study, InceptionV3 was used in the mobile deployment. FUSI (Fusarium Sigatoka) Scanner is the name of the developed application. The models’ performances are as follows: InceptionV3 performed at 95.4%, Resnet18 attained 98.8%, Resnet50 likewise attained 98.8%, Resnet152 recorded 99.2%, and VGG16 attained 98.4% (Mora et al., 2024). A RedEdge MS camera, drone, and UAV imagery were used to photograph landscapes in Eastern Congo, facing challenges like low altitude and tall trees. Techniques for image augmentation addressed data imbalance, and DL algorithms like Yolo-V8 and Faster R-CNN detected banana stems infected with banana xanthonomas wilt. Sujithra & Ukrit (2022) published comparing the performance of banana and sugarcane leaf disease. Images were taken from the farm Acharapakkam of Chengalpattu District, Tamil Nadu. The camera used here is a Canon EOS 3000D, with a resolution of (512 * 512). This article used CNN, Feed Forward Neural Network (FFNN), and Radial Basis Neural Network (RBNN) for analysis. In addition, preprocessing techniques and classification models, which include CNN, were employed. The obtained performance metrics for banana and sugarcane were 97% accuracy, 89%, and 90% in sensitivity and specificity at 98%, 87%, 91%, 96%, 86%, and 92%, respectively. For the same data, accuracy was obtained at 95%, 88%, and 91% in sensitivity and specificity at 94%, 86%, 92% and 96%, 87%, and 94%, respectively. A lightweight CNN for fruit crop leaf disease detection was proposed (Hari & Singh, 2023) in, focusing on banana, guava, and mango leaves. With a dataset of 8,010 images, it achieved accuracies of 98.82%, 99.71%, and 97.41%. Also, the other study (Aliff et al., 2024) focused on the utilization of DL methods and aerial photography to detect banana plant diseases. Preprocessing, segmentation, feature extraction, classification, and picture acquisition are also included in this. 80.36% and 79.24% accuracy were achieved by the CNN. Figure 10 estimates the workflow of DL.

Figure 10: Workflow of banana leaf disease detection using DL technique.

DL technique Heap Auto Encoders (HAEs) (Mary, Robert Singh & Athisayamani, 2020) proposed, K-means algorithm used for segmenting the banana leaf, the Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm is also used. The two HAE functions utilized the dropout method and the ReLU activation function, utilizing the publicly available dataset. The diseases focused on are bunchy top, bacterial bright spot, and banana bacterial wilt. The accuracy achieved is 99.35% for real data. The study (Criollo et al., 2020) proposed a CNN to detect the diseases concerning banana leaves. The data had 623 images, which were stored in three classes which were black sigatoka, bacterial wilt, and healthy, in an online repository. The architecture started with AlexNet, which includes convolutional, max pooling, and dense layers.

The dataset is around 8,000 to 9,000 images, gathered from the repositories Mendeley and Kaggle (Vinta et al., 2025). There were three classes of images included Kaggle dataset sigatoka, xanthomonas, and green leaf. Panama diseases, including black and yellow Panama, are also mentioned in the Mendeley.

A multitude of modifications—crop rotation, reflection, scale, crop, color saturation, and noise—were performed. In this work, the You only look once (YOLO) algorithm is used to diagnose illnesses. With 900 gathered image samples, Jain et al. (2024) classified banana plant diseases into five severity levels using a technique based on ML. In this work, the CNN and DT were combined for training and evaluation purposes. Levels 0 through 5 also represented the non-symptomatic to highly affected stages of the disease’s severity. The overall performance reached an accuracy of 96.04%.

Here, a collection of 18,000 field images was gathered (Selvaraj et al., 2019) through a network of banana experts from Tamil Nadu Agricultural University (TNAU) in Southern India and Africa. The proposed system experimented with architectures such as ResNet50, InceptionV2, and MobileNetV1. These models were trained to identify various types of diseases and pests affecting banana plants. The research achieved an impressive classification accuracy ranging from 70% to 99%.

A DL method (Neupane, Horanont & Hung, 2019) identified and counted banana plants from UAV RGB images, achieving 99% recall despite challenges like lighting and overlapping leaves. Techniques used included the Triangular Greenness Index. Saleem, Potgieter & Arif (2019) analyzes the use of DL models, specifically CNN, for disease diagnosis. The model utilizes a dataset from Plant Village for training. The workflow comprises data collection, data cleansing, and CNN architecture model training, followed by the evaluation phase that gauges the model’s performance. The findings show that DL approaches perform better than conventional approaches.

The study (Baguisi, Buenaventura & Yumang, 2024) works with the CNN algorithm to detect black sigatoka infections in the banana leaf using IP. This analysis was done using the raw dataset for augmentation. The performance attained accuracy of 95%, specificity of 93.33%, and a sensitivity of 96.67% (Elinisa & Mduma, 2024b). Implemented the Mask R-CNN DL technique to handle disease detection and segmentation on banana plants. This method utilizes the model’s capability of instance segmentation, whereby the pixel level of the area that is afflicted with disease is accurately pinpointed. This is a way to mitigate the accurate and efficient automated methods of disease detection, which tend to be labor-intensive. The proposed technique attained a mean precision of 0.04529 while utilizing an image dataset of 6,000 stalks and banana leaves obtained from the field, and was able to achieve segmentation on the afflicted regions proficiently.

On the other hand, Altabaji et al. (2023) proposed a disease diagnosis method for banana leaf diseases—cordana, pestalotiopsis, and sigatoka using CNN through a set of images of 2,000 banana leaves. The best CNN architectures for feature excitation and disease identification are chosen based on the performance of three models namely MobileNet, Xception, and InceptionV3. The proposed method produced results that should be further explored, as it showed a validation accuracy rate of 96.24%, making it very plausible for exact and effective disease classification and detection of banana leaves. Sigatoka and xanthomonas are the banana leaf diseases that are classified using DL models, namely the ResNet-18 and ResNet-34 architectures (Anushya & Shiwani, 2024). Images of healthy and sick banana leaves with xanthomonas and sigatoka infections. The images were gathered from various fields of agriculture. ResNet-34 achieved 98.32% accuracy. This work (Nieto et al., 2024) compares two methods: combination of the Green Leaf Index, K-means clustering, and YOLOv5m DL model. The YOLOv5m model performed precision of 86% and recall of 90%. In the task of coverage estimation, U-Net architecture was used, which had an IoU of 52.3%.

The study (Jadhaw & Bhandari, 2024) employed DL models to detect banana leaf diseases early, using 1,000 images from Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra. It focused on diseases like banana bacterial wilt and sigatoka disease. The YOLOv4 algorithm (Ibarra, Rivera & Manlises, 2023b) has been applied for detecting panama disease in banana leaves. Besides, the annotated dataset of 500 images of banana was collected from the Real-world plantations. It identifies the disease and locates with high accuracy and precision using the YOLOv4 DL model. The focused disease is panama disease. The primary algorithm (Rajalakshmi et al., 2025) using CNN, trained to recognize images of banana crops with or without disease was applied. Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation functions are applied in all CNN layers. Cross-entropy loss and optimization algorithms by applied during the training process. The best performance of the model delivers 88.32% accuracy. The GLCM for feature extraction from texture and classification by using DCNN (Mahendran & Seetharaman, 2022) was applied.

The ResNext50 DL model to create an automated framework for the classification of the severity of sigatoka disease in banana leaves with 10,000 annotated images in the dataset Singh et al. (2024) was used. This has been done at 95.53 accuracy with rigorous preprocessing and fine-tuning. It has been validated using recall and F1-score metrics. The confusion matrix and graphical comparisons explain the model’s effective performance, forming a foundation for precision agriculture and sustainable crop management through automated disease evaluation.

A hybrid model Kumar & Kumar (2024) that predicts the severity of banana leaf wilt using CNN and SVMs: Using DL techniques, which are effective in providing an accurate diagnosis of the condition, the model is created using 10,000 image-labeled sets of banana leaves; data augmentation improves the feature with CNN that has already been trained. It was able to provide a thorough assessment of the disease’s severity with an accuracy of 94.77% using precision, recall, and F1-score metrics. When compared to other top models and current techniques, it fared better. The lightweight DL algorithms to identify banana leaf diseases from images collected in Arusha, Northern Tanzania, with a smartphone, producing 16,092 images (Nassor, Mushthofa & Priandana, 2024) was used. Out of the models experimented: MobileNetv2, MobileNetv3-small, ShuffleNetv2, and SqueezeNet, SqueezeNet gave the better performance by recording 97.12% accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. MobileNetv3-small has a faster training time; MobileNetv2 was the lightest of the algorithms.

Senthilraj & Parameswari (2022) using CNN and VGG16 models, create a DL model to recognize and categorize the stages of black sigatoka disease in banana leaves. The CNN model showed better results than VGG16. Table 4 give the DL method used. CNN and M-SVM are used by Yan, Shisher & Sun (2023) to diagnose banana diseases in one category, specifically xanthonomas, fusarium wilt, bunchy top virus, black sigatoka. A total of 3,500 leaf photos taken with cell phones equipped with VGA cameras from various locations in South India, particularly Tamil Nadu and the Kerala border, made up the dataset. During preprocessing, median filtering was used, and the system achieved 99% accuracy, outperforming comparable techniques in disease prognosis.

| Ref | Methodology | Dataset | Diseases | Performance matrix |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seetharaman & Mahendran (2022) | Histogram pixel localization, Gabor-based binary patterns, convolutional recurrent neural network, KNN, SVM | 1,875 photographs from farms and online repositories. | Disease not classified. | Accuracy: 98%, |

| Mathew, Kumar & Cherian (2023b) | Xception, MobileNet V2, Inception V3, and DenseNet 121, | Using the Canon EOS 750D camera, the dataset was collected from Kerala Agricultural university. | Sigatoka, Cordana, and Deightonella. | Accuracy: 91.7%. |

| Bhuiyan et al. (2023) | Bayesian Optimization-SqueezeNet, MobileNets, EfficientNets, and ResNet, CNN | 937 field images Bangladesh. | Pestalotiopsis leaf blight, Sigatoka, and Cordana | Accuracy: 96.25% Precision: 96.53% Recall: 96.25% Specificity: 98.75% F1-score: 96.17% MCC: 95.13%. |

| Banerjee et al. (2023) | CNN, SVM | 1,100 images from primary and secondary sources | Disease not classified | Accuracy: 94% |

| Mary, Robert Singh & Athisayamani (2020) | HAEs, K-means algorithm, the Expectation- Maximization (EM) algorithm |

Public datasets-Scotnelson, Godliver, Plant village project, and real datasets. | Bunchy Top, Bacterial Bright Spot, BBW | Accuracy: 99.35% |

| Mohanraj et al. (2023) | CNN FFNN RBNN |

Images from Acharapakkam farms in Tamil Nadu, captured by Canon EOS 3000D | Banana: Black Sigatoka, and Yellow Sigatoka. | Accuracy: 97% |

| Altabaji et al. (2023) | CNN architectures, including MobileNet, Xception, and InceptionV3, | 2,000 images from various fields. | Cordana, Pestalotiopsis, and Sigatoka | Accuracy: 96.24%, |

| Criollo et al. (2020) | CNN | online repository, 623 photos | black sigatoka, bacterial wilt, and healthy | Accuracy: 80–90% |

| Tanwar, Sharma & Aanand (2023) | CNN. SVM | 1,100 images from primary and secondary sources. | Black sigatoka, cordana, and speckle disease | Accuracy: 90% |

| Hari & Singh (2023) | VGG16, VGG19, InceptionResNetV2, Xception, DenseNet121, MobileNetV2, ConvNeXtBase ConvNeXtLarge, DenseNet169, DenseNet201, ResNet50, ResNet50V2, ResNet152, ResNet152V2, InceptionV3, |

Kaggle and Mendeley- public dataset | banana Cordana, healthy, Pestalotiopsis, Sigatoka, guava diseased, healthy, mango diseased, and healthy | Accuracy: Banana—98.82% Guava—99.71% Mango—97.41%. |

| Aliff et al. (2024) | CNN | 6,700 images from Malaysia and public dataset like github. using basic cameras and a DJI Tello drone. | Black/yellow Sigatoka, bacterial soft rot, Panama disease, aphid, stem weevil, | Accuracy of 80.36% and 79.24%. |

| Jain et al. (2024) | CNN and Decision Trees, K-fold cross-validation process | 900 image samples | Diseases not classified. | Accuracy: 96.04% |

| Selvaraj et al. (2019) | ResNet50, InceptionV2 and MobileNetV1 | 18,000 images from Bioversity International in Africa and Tamil Nadu Agricultural University. | Diseases not classified. | Accuracy: 70% and 99% |

| Baguisi, Buenaventura & Yumang (2024) | Image processing paired with Shufflenet V2 CNN Algorithm | Raw dataset collected from the agricultural fields. | Black Sigatoka | Accuracy of 95%, specificity of 93.33% and sensitivity of 96.67%. |

| Nassor, Mushthofa & Priandana (2024) | DL algorithms, MobileNetv2, MobileNetv3-small, ShuffleNetv2, and SqueezeNet. | Arusha, Northern Tanzania, with a Galaxy 01 smartphone, producing 16,092 images | Disease not classified | Accuracy: 97.12% |

| Neupane, Horanont & Hung (2019) | Triangular Greenness Index, Synthetic Color Transform, and Linear Contrast Stretch, DL model. | RGB photos taken by UAVs | Diseases not classified. | Accuracy: 99% |

| Elinisa & Mduma (2024b) | R-CNN DL model | 6,000 banana leaves and stalks collected from the field | Black Sigatoka, Panama Disease, Banana Bunchy Top Virus, and Anthracnose | Average precision (mAP) of 0.04529 |

| Elinisa & Mduma (2024a) | CNN model | Mobile cameras from farms located in Tanzania. Duplicate Photo Finder and VisiPics applications | Black sigatoka, fusarium wilt diseases | Accuracy: 90% |

| Anushya & Shiwani (2024) | DL models, ResNet-18, ResNet-34 | Capturing both healthy and diseased leaves sourced from various agricultural fields. | Sigatoka and Xanthomonas | ResNet-34 accuracy of 98.32% |

| Mora et al. (2024) | Yolo-V8 and Faster R-CNN | RedEdge MS camera, DJI Phantom 4 Pro UAV, a DJI-FC6310 RGB camera, and UAV (Unmanned Aerial Vehicle) imagery to capture landscapes in Eastern Congo. | Banana Xanthomonas wilt | Accuracy: 98%, |

| Kumar & Kumar (2024) | CNN, SVM | 10,000 labeled banana leaf, | Disease not classified. | Accuracy: 94.77% |

| Singh et al. (2024) | ResNext50 DL model, | 10,000 annotated images | Sigatoka disease | Accuracy: 95.53% |

| Ridhovan, Suharso & Rozikin (2022) | DenseNet, Inception methods |

GIS & Remote Sensing Lab Agricultural University in Bangladesh, by smartphone camera | Cordana, Sigatoka, and Pestalotiopsis | Accuracy: 84.73%, precision: 84.80%, recall: 84.73%, F1score: 84.62%. |

| Jadhaw & Bhandari (2024) | CNN and DL models AlexNet, ResNet-50, and VGG-16, region-based segmentation, optimal thresholding | 1,000 images were captured using mobile and VGA cameras and digital cameras in Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra. | Banana Bacterial Wilt, Sigatoka Disease, Panama Disease, Leaf Spot Diseases, Nutrient Deficiencies | Accuracy: 99% |

| Gokula Krishnan et al. (2022) | CNN integrated hybrid fuzzy C-means clustering. | 9,000 images from International Centre for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT) banana image library. | Black Sigatoka, Yellow Sigatoka, BBW | Accuracy: 93.45%. Specificity: 96.38%, Sensitivity: 89.04% |

| Narayanan et al. (2022) | Hybrid CNN, SVM, median filtering |

3,500 field images across Tamil Nadu, VGA cameras in mobile devices, digital cameras, and DSLRs | Disease not classified. | Accuracy: 99% |

| Deng et al. (2024) | Ghost ResNeSt-Attention RReLU-Swish Net (GR-ARNet) | 13,021 leaf images on Kaggle website, including 983 images of banana leaves from Jieyang City, Guangdong Province, China, taken with a Sony ILCE-5100L camera. | Sigatoka, Cordana, and Pestalotiopsis diseases | Accuracy: 98.38%. |

| Bharathi Raja & Rajendran (2023) | CNN and VGG16 models | 16,092 banana leaf and stem images from farms across Tanzania, Arusha, Dar es Salaam, Kagera, Kilimanjaro, and Mbeya, collected | Black Sigatoka disease | Accuracy: 80.36% and 79.24%. |

| Yan, Shisher & Sun (2023) | CNN and Multivariate Support Vector Machine | 3,500 plant leaf images captured with VGA camera-equipped mobile phones, was collected from Tamil Nadu and Kerala border | Xanthomonas Wilt, Fusarium Wilt, Bunchy Top Virus, Bacterial Wilt | Accuracy: 98%, |

What kind of impact does TL have on the process of detecting and classifying banana leaf diseases?

Deep CNN combined with TL to detect the fusarium wilt of banana plants (Derafi, Razak & Sayeed, 2024) was proposed. In this regard, ResNet-50 was used, and a TL is applied in it to enhance its precision as well as efficiency. A total of 500 test images consisting of healthy and diseased parts were used. The accuracy is recorded at 0.98 and the F1-score is at 0.98.

Salehin, Islam & Alam (2024) applied TL for the disease identification of the banana leaf. Besides that, pre-trained models, EfficientNet, AlexNet, VGG, and ResNet, were also tested with the diseases. The dataset is obtained from the Plant Village, Nelson Mandela dataset, with 17,068 images of banana plants, and the PSDF- Musa. A total of 54,303 images of 14 types of crops were used. Among them, the data preprocessing techniques involve methods such as torchvision. transforms.resize for resizing and e-transforms. ToTensor() for normalization of pixel values, with transforms. Normalize normalizing data. The accuracy and the F1-score are also more than 90% and 0.90%.

TL-based (Genet et al., 2024) is proposed to automatically identify banana diseases. A dataset of 17,068 labeled images was compiled using the AdSurv mobile application on Samsung phones for taking pictures of banana leaves and stems. Researchers from the African Institution collaborated with the Tanzania Agricultural Research Institute. This comparison study on the performances of such models as VGG19, NasNetLarge, Inception ResNet V2, and Xception found that the model Xception is the best since it achieved a classification accuracy of 98.062%. A robust disease detection model is developed (Priya et al., 2024) using CNN algorithms to classify and identify diseases in banana plants. The dataset comprises 1,982 photos, all of which have been affected by banana diseases. The images are categorized into three groups: healthy, xanthomonas wilt infected, and sigatoka leaf spot infected. Using data augmentation and TL techniques that are high-end, the architecture of models was fine-tuned using MobileNet, EfficientNet, VGG16, VGG19, and InceptionV3. Amongst them, the VGG16 model performed excellently well and successfully withstood independent test datasets with 81.53% accuracy. A DenseNet201Plus model was created (Mazumder et al., 2024) to identify banana leaf diseases, achieving 0.9012 accuracy and precision, 0.9012 recall, and 0.9716 AUC. It was trained on healthy, sigatoka, and xanthomonas leaf classes, using data from Mendeley Data and enhanced through rotation, flipping, and scaling.