Systematic evaluation of ChatGPT performance in providing renewable energy information

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Rajeev Agrawal

- Subject Areas

- Artificial Intelligence, Computational Linguistics, Data Mining and Machine Learning, Natural Language and Speech, Text Mining

- Keywords

- Large language models (LLMs), Systematic LLMs evaluation, ChatGPT, Natural language processing, Renewable energy

- Copyright

- © 2025 Ibrahim et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2025. Systematic evaluation of ChatGPT performance in providing renewable energy information. PeerJ Computer Science 11:e3295 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3295

Abstract

With the advent of attention mechanisms and the development of transformer-based architectures, a new era of large language models (LLMs) has emerged. These models have given rise to a wide range of fine-tuned applications capable of providing high-quality and informative responses. ChatGPT, a chatbot developed by OpenAI using a popular LLM called GPT 3.5, has demonstrated its capability to provide valuable information in a range of fields. The renewable energy field is a prominent field, which aims to explore alternative sources of energy that are more affordable and effective. In this study, we examine how accurate ChatGPT is when it comes to providing general, non-technical information on renewable energy compared to human experts in this field. A set of prompts was presented to ChatGPT as well as to a human expert. Responses have been collected and evaluated using a set of similarity measures. Further to this, a pre-trained Google vector has been applied to emphasize semantic similarity, and then a more sophisticated LLM competitor evaluation, Gemini, has been employed to evaluate the degree of similarity between ChatGPT responses and those of human experts. It surprisingly comes to a point where ChatGPT responses were more accurate and relevant than those of human experts’ responses on renewable energy prompts. This study concludes that ChatGPT is a promising and supportive resource for renewable-energy information, offering responses remarkably close to those of a human expert.

Introduction

The evolution of natural language processing (NLP) tools led to a new era of information discovery. Traditional methods of defining words in contexts have advanced from basic statistics to machine learning methods. A word in text is now defined by a dense vector that represents not only the word and its accompanying words, but also its position, its semantics, its syntax, and many more. The new era of machine learning and NLP word embedding models is called large language models (LLMs). These models adopt all the concepts of NLP in addition to vectorization, with more information about the words and their accompanying ones. Further to this, they define word positions and add masks to the vector to find the best word representation. GPT3, which is short for Generative Pre-trained Transformer, and its advancement, such as GPT3.5 and recently GPT4, made a big change in this field. These models were scaled up to process very large texts, leveraging the concepts of transformers. The transformers are trained on a parameter count of 175 billion (Brown et al., 2020). The Word embeddings generated by the transformers are fine-tuned for the task of building ChatGPT.

ChatGPT is a chatbot built by OpenAI using one of the large language models, namely GPT-3.5. It has proven its ability to deliver interesting information in a wide range of fields. Since the time ChatGPT was presented, many applications have revolutionized, such as customer support, question answering, language translation, and many more (Ray, 2023; King & ChatGPT, 2023; Wu et al., 2023; Biswas, 2023; Marr, 2023; Bukar et al., 2024b; Bouteraa et al., 2024).

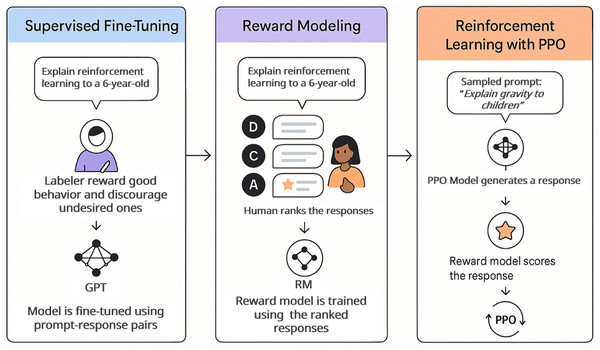

Figure 1 shows the major steps of ChatGPT’s main concept of learning, which is known as Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) (Trivedi et al., 2023). In the first step of Fig. 1, the human is tuning the prompt learning progress by proposing the prompt and their ideal response. Then, in step 2, the Reward Model (RM) is used by a human labeler to rank different responses from the best to the worst. The model accordingly learns the quality of the responses depending on human preferences. The Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) technique is applied in step 3 to optimize the model based on RM ratings, which in turn enables the model to produce higher-quality and more appropriate responses according to the prior preferences. Since its launch, ChatGPT has attracted nearly 100 million registered users (Milmo, 2023).

Figure 1: The RLHF of ChatGPT training mechanism that OpenAI has applied.

ChatGPT has attracted nearly 100 million registered users since its launch in 2021. SimilarWeb analytics has also shown that the ChatGPT website received more than 1.5 billion visits with a bounce rate of 39% (SimilarWeb, 2023). Further to this, several studies have highlighted that ChatGPT’s ability to provide proper information was satisfying to human requirements in different fields (George & George, 2023; Dwivedi et al., 2023; Johnson et al., 2023; Bommineni et al., 2023; Lund & Wang, 2023). Nevertheless, concerns have arisen about the ethical considerations and regulatory frameworks needed to govern ChatGPT as an information tool (Bukar et al., 2024a). In fact, ChatGPT is more than just a conventional chatbot; rather, it is able to act in different contexts like a real person. For example, ChatGPT can be asked about how to solve mathematical problems or programming exercises. Furthermore, it can chat interactively, exchanging responses back and forth. It is also able to chat in a human-like manner, retrieving information and answering questions.

The future of linguistic communication may change after this tool. In the near future, we may speak to people thinking of them as humans, but they are human-like robots (Hubots). Having someone to talk to and ask questions is the essence of any communication. However, this is still a chatbot that is trained on human-generated data. Hence, a multitude of questions arise regarding the functionality and reliability of the ChatGPT chatbot. These questions include assessments of its accuracy (e.g., How accurate is the information provided by ChatGPT compared to human expert knowledge?), considerations regarding the adequacy of information provision, and reflections on its potential (e.g., Can ChatGPT substitute experts?). Additionally, concerns are raised regarding the sourcing and validation of data utilized in training such chatbots, particularly within specialized domains that directly impact human lifestyles (e.g., Can ChatGPT aid in the advancement of renewable energy technologies?). This research is represented as the base framework for investigating of ChatGPT’s capability in providing related and represented information in specialized domain like renewable energy.

Renewable energy has been selected as the focal point of our case study to explore LLMs such as ChatGPT, primarily because of its significant contribution to the reduction of CO2 emissions (Caglar, 2020), which is a critical global concern in the present era of climate change. Renewable energy is a source of energy that generates power naturally with little or no emissions (Owusu & Asumadu-Sarkodie, 2016). It is characterized by utilizing its natural way of energy generation with minimal or no emissions. Reduction of emissions plays an important role in mitigating environmental concerns, particularly reduction of CO2 emissions, which are central to reducing climate change (Raihan et al., 2024; Raihan & Bari, 2024). Applying LLMs and artificial intelligence (AI) technologies in renewable energy holds the ability to improve the efficiency of renewable energy projects using streamlined processes, providing recommendations for resource allocation, and helping innovative solutions (Lukianykhin et al., 2024). In predictive modeling and optimization methods for intelligent control and monitoring systems, these methods give a range of tools and approaches to improve the performance and reliability of renewable energy systems while utilizing AI and LLM. In addition to that, renewable energy can benefit from LLMs through training them on its data and getting insights that can help in achieving accurate decisions (Rane, 2023; Atwa, Almazroi & Ayub, 2024).

ChatGPT’s task in this study is to understand the formulation of questions and information regarding renewable energy sources and provide responses. The questions that follow and answers have been collected from a variety of reliable renewable energy sources. Then, we systematically compared responses from ChatGPT and domain experts, applying text analysis as well as hypothesis testing using a paired sample t-test to evaluate the degree of similarity. We aim to systematically evaluate the accuracy, depth, and reliability of ChatGPT-generated information in the renewable energy domain, with the goal of clarifying its potential benefits and risks as a supportive tool. Specifically, we investigate the extent to which GPT responses align with human expert answers in both lexical and semantic dimensions, and further evaluate the responses using an independent LLM-based assessor, namely, Gemini. It is imperative to mention that this study focuses on general, non-technical renewable energy information that is intended for public understanding and does not assess expert-level or engineering-specific content. The contributions of this research can be summarized as follows:

-

1.

Contributes to understanding the capabilities and limitations of ChatGPT in the domain of renewable energy. By systematically comparing ChatGPT responses with those of domain experts, insights into the accuracy and comprehensiveness of ChatGPT responses are garnered, shedding light on its potential utility as an information tool within this specialized field.

-

2.

The research methodology employed, particularly the systematic comparison using text analysis techniques, provides a replicable framework for evaluating the performance of ChatGPT as an LLM in a specialized field. This methodological approach can enhance the rigor and standardization of evaluating LLM performance.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows: background and related work are presented in the next section. After that, the research methodology and the proposed systematic comparison framework using text analysis techniques are explained in detail. Then, the results and their discussions are presented, and finally, the conclusions of the research and future prospective work are provided.

Related works

Large language models have revolutionized NLP and AI, offering unprecedented capabilities in understanding and generating human-like text. Their potential applications are vast and span multiple domains (De Angelis et al., 2023). LLMs build on a new advancement in the field of artificial neural networks called transformers. Transformers were first introduced by Vaswani et al. (2017) in their research article entitled “Attention is All You Need”. They have stated that transformers could achieve state-of-the-art results on a variety of natural language processing tasks, including machine translation, text summarizing, and question answering. Traditional word embedding models, like Word2Vec (Mikolov et al., 2013), GloVe (Pennington, Socher & Manning, 2014), Fasttext (Bojanowski et al., 2017), and their variants have been applied in various fields such as translation (Wolf et al., 2014; Sitender, Sushma & Sharma, 2023; Gogineni, Suryanarayana & Surendran, 2020), named entity recognition (Arguello-Casteleiro et al., 2021; Sienčnik, 2015; Kim, Hong & Kim, 2019; Hou, Saad & Omar, 2024), healthcare (Ibrahim et al., 2021; Craven, Bodenreider & Tse, 2005; Hasan & Farri, 2019; Amunategui, Markwell & Rozenfeld, 2015; Zhu et al., 2016; Hajim et al., 2024), and many others. Despite many improvements to these models and their applications, they have not reached the level of the new NLP and LLM advancements. LLMs and their variants have revolutionized communication, decision making, critical thinking, and data analysis. ChatGPT is a notable example of the innovations stemming from the advancements in LLMs.

Significant research has been undertaken since the launch of ChatGPT. While Rathore has employed ChatGPT to improve textile production by studying the customer’s preferences to provide relevant recommendations. Rathore, however, has yet to justify how ChatGPT works as a recommender system (Mollman, 2023). Bommineni et al. (2023) have examined ChatGPT with the Medical College Admission Test (MCAT), and the results were promising. ChatGPT was able to answer over the median of approximately students. Besides that, ChatGPT was able to provide insightful responses that were nearly identical to the standard responses. Such an ability opens the door for creating additional questions and/or insights to help medical students when it comes to MCAT (Bommineni et al., 2023). A similar study by Kung et al. (2023) examined ChatGPT, but this time on the United States Medical Licensing Exam (USMLE). Their study has reported that ChatGPT showed a surprising performance and overcame the USMLE.

Jiao et al. (2023) have evaluated ChatGPT on translation tasks using different language datasets ranging from well-known languages to distant languages. While ChatGPT was a competitor to popular translators, such as Google Translate, for popular languages, it was less effective for distant languages. Further to this, ChatGPT has been tested on 20 mainstream NLP datasets representing seven evocative tasks by Qin et al. (2023). Their experimental study concluded that ChatGPT was able to achieve several reasoning tasks, such as arithmetic operations, although it has performed some tasks imperfectly. On the other hand, Li, Jiang & Mostafavi (2023) have conducted an empirical assessment of ChatGPT responses concerning protective action information. The responses were collected from ChatGPT, and then a survey was developed using these responses. A total of 38 specialized experts in the field of emergency response have assessed the survey and confirmed that the ChatGPT responses were accurate and relevant to the subject area.

Another study has evaluated ChatGPT on different questions related to the medical license exam in the United States using four different datasets. The results demonstrated that ChatGPT outperforms InstructGPT by 8.15% on average. The study also recommended that ChatGPT can be used as a medical tutor (Gilson et al., 2023). A more relevant study was done by Johnson et al. (2023), focusing mainly on the medical field, in which around 280 questions were collected from 33 medical doctors from the same academic center. This may be an indication of bias in the data; therefore, we have gathered our data sample from various online sources, where several experts answered questions.

In the same direction, a study has investigated the reliability of –4 in providing medical information to patients and healthcare professionals. The Ensuring Quality Information for Patients (EQIP) tool has been applied to measure the quality of information for five different diseases. Human in the loop approach has been applied for question/answer in an independent setting. For all 36 items of the EQIP, the median score was 16 –18). There was 60% agreement between the guidelines and ChatGPT responses (15/25). Significant agreement was noted using Fleiss’ Kappa measure, which estimated the inter-rater agreement at 0.78 with . Overall, the responses that ChatGPT delivered were 100% consistent compared to online medical information (Walker et al., 2023).

The evaluation of ChatGPT responses in the field of renewable energy remains an underexplored area. Although a handful of articles and blogs touch on related themes, they generally lack solid experimental design and fail to incorporate either quantitative or qualitative analysis that would allow for a reliable assessment of ChatGPT’s informational accuracy and consistency. ChatGPT has been investigated in published research for its potential in intelligent energy management applications, like forecasting energy usage and giving consumers energy-saving guidance (Shah, 2023). However, these studies do not evaluate the trustworthiness or depth of the information provided, nor do they compare ChatGPT’s responses against expert-level standards, which is critical when addressing complex scientific domains such as renewable energy. Another study has introduced an Energy service chatbot that combines the power of LLMs and a multi-source Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) framework (Arslan, Mahdjoubi & Munawar, 2024). This Energy service chatbot has been evaluated against LLMs like Llama2, Llama3, and Llama3.1 models, demonstrating improvements in precision, recall, accuracy, and F1-scores with RAG integration. While it benchmarked against models like LLaMA2 and LLaMA3.1, there was limited discussion on how the chatbot’s responses align with real-world expert understanding of renewable energy systems.

RE-LLaMA has been presented as a domain-specific LLM model for renewable energy and built based on LLaMA 3.1 8B (Gabber & Hemied, 2024). RE-LLaMA has been fine-tuned using nearly 1,500 academic articles, covering a wide range of topics, including optimization, hydrogen technologies, and the design of renewable systems, along with decarbonization strategies. A significant amount of work has been dedicated to data processing and cleaning. RE-LLaMA abilities have been evaluated with zero-shot and few-shot learning. While RE-LLaMA narrows the domain gap, the evaluation remains centered on technical model performance rather than end-user informational reliability or expert alignment. Additionally, no human-in-the-loop assessment was conducted to benchmark responses against subject matter expertise.

In contrast to prior investigations, our research uses a structured comparison analysis with subject matter experts to directly address the significant gap in assessing ChatGPT’s responses on renewable energy subjects. Rather than depending exclusively on task-specific performance measures or standards, we use a methodical evaluation that compares ChatGPT’s responses to experts’ responses in order to determine how accurate, thorough, and pertinent they are. This human-grounded comparison approach provides unique insights into the model’s capabilities and limitations when applied in high-stakes, knowledge-intensive domains.

Materials and Methods

In this section, we discuss the process of data collection and data analysis approaches. The proposed methodology discusses response similarity approaches between human and ChatGPT-generated responses. This includes details of both lexical and semantic measurements. Our research provides a framework for evaluating ChatGPT’s accuracy in providing renewable energy information.

Data collections

This section discusses the reliability and availability of the data that was used to assess ChatGPT’s responses about renewable energy. Regretfully, there isn’t a dataset created especially to evaluate how well AI-powered chatbots function when delivering information about renewable energy.

This study is unique in collecting, testing, and validating a hand-crafted ground-truth dataset of human expert responses on renewable energy-related questions/prompts, through a rigorous validation process. The dataset is manually curated using a collection of 63 prompts to encapsulate different dimensions of renewable energy information and to demonstrate ChatGPT’s capabilities within a tightly defined context. To address potential bias in prompt selection, we have collected corresponding responses from multiple authoritative renewable-energy specialized websites. In addition, we only considered responses that met consensus among renewable-energy experts in terms of clarity and relevance. It is imperative to mention that the human responses were obtained exclusively from reputable, public-facing renewable energy websites and blogs, including NSCI, Arcadia, Amigo Energy, and MyEnergi, where content is authored or reviewed by domain experts with valid credentials and editorial oversight. This will ensure fact-based, accessible renewable energy information is consistent with the non-technical focus of our study.

This collection of prompts has been captured from human-generated content on renewable energy and has been found on specialized websites. We selected these websites by matching relevant keywords and ensuring their content focused on renewable energy. Keywords such as renewable energy, clean energy, sustainable energy, solar and wind energy, biomass energy, and hydropower energy have been listed in our search strategy. Moreover, we ensured that all the content preceded the widespread emergence of AI-generated content and was online before the launch of ChatGPT. Also, we have ensured that the prompts span a spectrum of topics, including the classification of renewable sources, the delineation of their advantages and disadvantages, the exploration of associated technologies, the examination of policy frameworks, and trends within the renewable energy landscape. By encompassing such a broad spectrum of general and specialized prompts, the generated dataset facilitates a robust evaluation of the ChatGPT responses and the depth of knowledge in renewable energy. This study offers a handcrafted dataset on renewable energy online on Kaggle to be publicly available and used by the research community, serving as ground truth for LLM case studies.

Table 1 provides a glimpse into examples from the dataset, showcasing a selection of questions and prompts gathered from domain experts and individuals with a vested interest in renewable energy and climate change mitigation efforts. Each question is precisely paired with its corresponding human expert response, ensuring the availability of ground truth data against which ChatGPT responses can be benchmarked. It is important to note that these data were sourced from a multitude of reputable renewable energy platforms and repositories. By leveraging diverse data sources, we aim to mitigate the risk of bias and ensure the robustness of the evaluation process.

| No. | Prompts | Human-expert responses | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | What is renewable energy? | Renewable energy, often referred to as clean energy, comes from natural sources or processes that are constantly replenished. For example, sunlight or wind keep shining and blowing, even if their availability depends on time and weather… | |

| 2. | Does renewable energy cause pollution? | Though all energy sources impact the environment to an extent, renewable energy produces close to no pollution and far less than fossil fuel energy. Let’s focus on wind power. Wind turbines produce no greenhouse gas emissions… | |

| 3. | Why is some energy renewable? | Renewable energy is a replenishable energy source that won’t run out for many millions of years. Solar energy and wind energy are examples of renewable energy sources. The sun will exist for billions of years. While the wind may not always blow, The Earth’s orbit path, temperature, and rotation mean there will always be wind blowing on the planet… | |

| 4. | Why is renewable energy expensive? | Renewable energy does have a reputation as being expensive in the eyes of some. This is because building the initial renewable energy generators, such as wind turbines and solar panels does requires investment. However, this investment will save you a lot of money in the long run… | |

| 5. | How many different types of renewable energy are there? | The two main sources of renewable energy are solar and wind power. We use solar energy every day, from growing crops on farms to staying warm. light is converted into electricity that flows through the circuit. We can also produce electricity through wind power. A wind turbine turns energy in the wind into electricity using the aerodynamic force created… | |

| 6. | How does renewable energy save money? | There are a number of ways that renewable energy will save you money. For one, your electricity bill could be lower. Businesses that install solar panels, wind turbines, and other forms of renewable energy on their properties and use them to power their operations can meet a significant portion or all of their energy needs… | |

| 7. | Who can use solar energy? | Not everyone has the proper roof or resources to accommodate solar panels. However, community solar is an option that is becoming increasingly available nationwide and doesn’t demand the same long-term commitment, upfront cost, or construction as rooftop solar… | |

| 8. | How does wind energy work? | Wind turbines send the wind’s energy to power a generator, which creates electricity. Although the electrical output of a wind turbine depends on its size and the wind’s speed, it is estimated that nearly 25 million US households can be powered by the USA’ current wind capacity… |

Similarity measurements

In this section, we comprehensively evaluate response similarity between human and ChatGPT responses, employing both lexical and semantic measurements. Initially, for lexical measurements, we used text similarity metrics, such as Jaccard, Cosine, Levenshtein, and Sorensen-Dice to quantify similarity. These metrics have the ability to measure the extent of term overlap between two texts; thus, they can capture the surface-level similarity between the ChatGPT responses and human expert responses. This process is then followed by a semantic analysis using Google’s Word2Vec embeddings to capture contextual similarity. This textual similarity and semantic metrics were driven by the need to evaluate ChatGPT responses in a consistent manner with how humans process and understand language. Moreover, an evaluation using an LLM competitor, Gemini, was conducted to measure the degree of similarity between ChatGPT and a human expert. This section provides a comprehensive evaluation of ChatGPT responses related to the renewable energy domain.

The first approach, lexical measurement, involved response/prompts matching to assess whether ChatGPT responses share greater similarity with the reference than a human expert’s . In this context, we have computed for each prompt a paired difference, which involves finding the common words that and have shared as . The similarity scores of and were respectively measured by conventional text similarity metrics such as Jaccard, Cosine, Levenshtein, or Srensen˘Dice. We then performed a one-sample, one tailed paired t˘test with vs . With 95% confidence interval for the mean difference , which is given by , where denotes the standard deviation and is our sample size. To keep it simple and straightforward, we are using A as a reference to human expert responses and B for ChatGPT responses for the rest of this article.

The detailed steps of this approach are presented in Algorithm 1. The processes begin by defining the input and required parameters, followed by pre-processing to remove unnecessary contents (e.g., stopwords and punctuation) to start response tokenization and find common words as per Algorithm 1, Lines 1–5. The process of finding common words between two sets of responses representing a human expert response A and a ChatGPT response B involves several steps: ( ) removing stopwords and punctuation, ensuring that only meaningful words are considered, ( ) the text is tokenized, breaking it down into individual words or tokens by splitting the text based on whitespace characters (spaces, tabs, etc.), ( ) These tokens are then converted into sets, data structures that contain unique elements, to eliminate duplicate words, ( ) Finally, the intersection or operation is then applied between the two sets, resulting in a new set containing only the words that are common to both the human expert response and the ChatGPT response. In this final step, the Jaccard (J), Cosine (C), Levenshtein (L), and Sorensen-Dice ( ) were used as similarity metrics in Algorithm 1, lines 6–10. The mathematical formulas and corresponding functions for the adopted similarity metrics are presented in Algorithm 1, Lines 24–39.

| Input: Expert ( = ); ChatGPT ( = ); |

| 1 Jaccard (J); Cosine (C); Levenshtein (L); SorensenDice (SD) |

| Result: ; |

| procedure MatchResponses , |

| Let be the set of words in Response A for Question 1 (human expert response) |

| Let be the set of words in Response B for Question 1 (ChatGPT Response) |

| Remove stopwords and punctuation from A and B |

| ▹ Find common words |

| Jaccard(A, B) |

| Cosine(A, B) |

| Levenshtein(A, B) |

| SorensenDice(A, B) |

| return |

| end procedure |

| procedure MatchAfterStemming( , ) |

| Apply SnowballStemming function to both HumanResponse and ChatGPTResponse; |

| Compute word similarity between stemmed responses; |

| Apply Procedure 1; |

| return |

| end function |

| function SnowballStemming(text) |

| Load Snowball stemmer |

| Tokenize text into words: |

| for each word wi in the text) do |

| Apply stemming to word wi: |

| Return: Stemmed text |

| end function |

| function Jaccard(A, B) |

| return J(A, B) |

| end function |

| function Cosine(A, B) |

| return C(A, B) |

| end function |

| function Levenshtein(A, B) |

| Compute L distance between A and B |

| return L distance |

| end function |

| function DorenseDice(A, B) |

| return |

| end function |

Moreover, as part of the first approach, we employed the Snowball stemming tool (Porter, 2001) to convert the words from both responses into their basic forms, thereby enhancing the degree of similarity marginally. The procedure named ‘MatchresponsesAfterSnowballStemming’ in Algorithm 1 involves several steps to compare responses from both humans and ChatGPT after applying Snowball stemming. Initially, the ‘SnowballStemming’ function is applied to both the HumanResponse and ChatGPTResponse, converting them into their stemmed forms (aka, converting text into basic forms) to improve similarity measurement. The ‘SnowballStemming’ function process involves loading the Snowball stemmer and tokenizing the input text into words. Then, it iterates over each word in the text and applies Snowball stemming to convert it into its basic form.

Subsequently, the word similarity between the stemmed responses is computed. These stemmed responses passed to the ‘MatchResponses’ procedure in Algorithm 1 to apply the similarity metrics measures in Algorithm 1, lines 6–10. Finally, the procedure returns the common words and similarity scores, including J, C, L, and , providing insight into the degree of similarity between human and ChatGPT responses after applying Snowball stemming. It is important to note that while an increase in similarity of words has occurred, it does not indicate or prove that ChatGPT has produced a similar/accurate response. Hence, we adopted the semantic measures in the second approach.

In the second approach, which was semantic measurement, we realized that evaluating ChatGPT’s effectiveness based solely on word similarity is deemed insufficient. Therefore, to address this limitation, we incorporated another measurement focusing on semantic similarity in the second approach. For this purpose, we utilized Google’s pretrained embeddings, consisting of three billion embeddings derived from the Google News Corpus and trained using the Word2vec Model. These embeddings enabled the comparison of semantic similarities between human responses and those generated by ChatGPT. Algorithm 2 provides a comprehensive approach to evaluate response similarity, incorporating semantic-level measurement similarity. The algorithm begins with the ‘SemanticSimilarity’ procedure, which takes two inputs: ExpertResponse and ChatGPTResponse, representing the human and ChatGPT responses, respectively. Following this, the procedure computes the semantic similarity score between the human and ChatGPT responses (Algorithm 2, lines 1, 8). Finally, the algorithm evaluates the ‘SemanticSimilarity’ function and calculates the semantic similarity between two responses, A and B, using cosine similarity. It starts by loading Google’s pretrained Word2Vec embeddings. Then, it represents the responses as word vectors and computes the cosine similarity score between them. This score reflects the semantic similarity between the responses, capturing their contextual similarity beyond the simple word matching adopted in the previous approach. Finally, the function returns the semantic similarity score .

| Input: Expert ( = ); ChatGPT ( = ); |

| Result: SemanticSimilarityScore (SSc); |

| 1: procedure SemanticSimilarity ( , ) |

| 2: Input: ExpertResponse A, ChatGPTResponse B |

| 3: Output: Semantic similarity score S |

| 4: Load Google’s pretrained Word2vec embeddings |

| 5: Represent A and B as word vectors: , |

| 6: Compute semantic similarity score SSc between A and B using cosine similarity: |

| 7: |

| 8: Return: Semantic similarity score SSc |

| 9: end procedure |

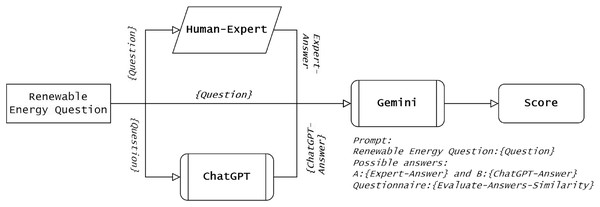

The third approach is to further examine the semantic similarity of ChatGPT responses. An additional assessment was conducted through a comparative analysis with responses generated by Gemini, which is another prominent chatbot. Gemini was not used as a comparative benchmark in this study; rather, it served merely as an additional layer for the similarity measure between the ChatGPT and human expert responses. Gemini, formerly known as Bard, is a widely prominent chatbot powered by the Pathways Language Model (PaLM) (McIntosh et al., 2023), developed by Google in February 2023. Leveraging the capabilities of Gemini, it provides a benchmark for evaluating ChatGPT responses’ accuracy in comparison to human expert knowledge. Gemini has been selected as an evaluation tool because it has been configured, trained, and tested differently from ChatGPT. Also, Gemini is a key competitor and has big potential to reshape the AI landscape. In this context, Gemini was given a set of prompts, and similarity scores were collected for subsequent analysis/observation. As shown in Fig. 2, the ground truth dataset of prompts, along with human expert responses and ChatGPT responses, was presented to Gemini for similarity measure and scoring.

Figure 2: A head-to-head Gemini-based comparison between human-expert responses and ChatGPT responses, which represents our third similarity measurement approach.

Results and discussion

In our comprehensive evaluation, a mixture of qualitative measurements has been applied to evaluate the performance. In the quantitative part, traditional measures of similarity have been employed. Initially, a direct similarity was considered, and then a semantic similarity. Further to this, both the human expert and ChatGPT responses have been presented to another popular chatbot to confirm the ability of ChatGPT to generate accurate responses and increase the power of the qualitative evaluation. This allowed us to assess the similarity of the two responses. The multifaceted approach allowed us to evaluate the accuracy and relevance of the information provided by ChatGPT.

In order to assess the ChatGPT responses regarding renewable energy prompts, a set of similarity matrices was applied. This evaluation compares a group of words generated by human experts to those produced by ChatGPT using Jaccard similarity, Sorensen dice, Levenshtein, and Cosine Similarity metrics. Initially, a word-to-word comparison has been conducted, then all punctuation and stop-words have been dropped, and words have been stemmed to their basic form. Using a paired sample t-test, there was insufficient evidence to reject the null hypothesis , which is clearly due to the poor word-to-word comparison approach being applied in the first phase of this experiment. The small effect size further supports the lack of practical significance between the two sets of answers in this approach. Table 2 presents the pre- and post-processing mean score of these similarity matrices.

| Similarity method | Scores pre-processing | Scores post-processing |

|---|---|---|

| Jaccard | 0.39 | 0.39 |

| Sørensen-Dice | 0.53 | 0.54 |

| Levenshtein | 0.22 | 0.23 |

| Cosine | 0.60 | 0.61 |

It can be observed from Table 2, that the similarity scores were underwhelming, with cosine similarity peaking at only about 60 and 61 for pre- and post-processing, respectively, which was the highest score recorded among all metrics. In fact, pre- and post-processing similarity scores show only slight changes due to shortened responses of ChatGPT and human experts, which are characterized by limited stop-words and punctuations. It is imperative to mention that this similarity alone does not definitively determine whether ChatGPT responses are closely aligned with those produced by human experts. One effective technique is to use semantic similarity, which captures the overall meaning of each response. In order to explore the semantics similarity in greater detail, we conducted a thorough assessment using Google News vectors. This was followed by the cosine similarity measure because it produced the most promising results during the syntactic similarity evaluation.

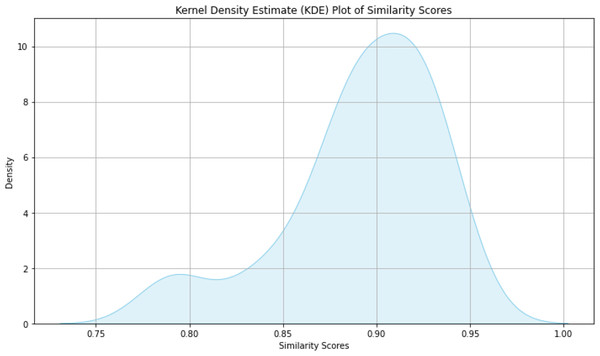

Figure 3 demonstrates the mean semantic similarity score measured by Google News vectors along with cosine similarity and presented using Kernel Density Estimation. The mean semantic similarity was about 87% across all 52 prompts. It is obvious that the most semantic similarity values were clustered around 91%. Such clustering indicates not only a high central tendency but also low variance, confirming that ChatGPT’s responses closely mimic those of a human expert. Further to this, a second round of paired sample t-test has been applied, and this time we have successfully rejected in favor of with a , emphasizing the importance of the semantic similarity measure and that ChatGPT responses were statistically significantly more relevant than those of the human experts when it comes to renewable energy prompts.

Figure 3: Density of semantic similarity scores between ChatGPT and human expert responses as reported by KDE majorly observed between 85% and 95%.

Further to this, an additional assessment has been conducted to evaluate the accuracy of ChatGPT responses. This has been done by comparing ChatGPT responses with expert ones using Gemini (named before as Bard). Gemini is a popular chatbot driven by the Pathways Language Model (PaLM) (McIntosh et al., 2023) and developed by Google in February 2023. For this purpose, a 10-prompt questionnaire was designed and presented to Gemini, and then the responses were collected for analysis. Table 3 demonstrates prompts and their scales of responses that were presented to Gemini. These prompts include commonly asked renewable energy questions that were selected from our dataset, along with the responses provided by an expert human (response A) and those generated by ChatGPT (response B). Then, Gemini was asked to assess the similarity between responses A and B using a 1–10 scale, to determine if the responses share the same viewpoints and to decide which option is the most relevant. The average similarity score by Gemini, for each question, is presented in Table 4.

| No. | Prompts | Responses on predefined scale |

|---|---|---|

| P1 | How similar do you perceive Response A and Response B to be? | (Not similar at all, Slightly similar, Moderately similar, Very similar, Extremely similar) |

| P2 | How would you describe the level of agreement between Response A and Response B? | (Strongly disagree, Disagree, Neutral, Agree, Strongly agree) |

| P3 | In your opinion, how closely do Response A and Response B align in terms of their main message or content? | (Completely misaligned, Somewhat misaligned, Neutral, Somewhat aligned, Completely aligned) |

| P4 | Do you think Response A and Response B share similar viewpoints? | (No, they have completely different viewpoints. No, they have slightly different viewpoints. Neutral. Yes, they have slightly similar viewpoints. Yes, they have completely similar viewpoints.) |

| P5 | How similar are the underlying arguments or evidence provided in Response A and Response B? | (Not similar at all, Somewhat dissimilar, Neutral, Somewhat similar, Extremely similar) |

| P6 | To what extent do Response A and Response B use similar language or terminology? | (No similarities in language or terminology. Few similarities in language or terminology. Neutral. Some similarities in language or terminology. Many similarities in language or terminology) |

| P7 | How consistent are the conclusions or recommendations presented in Response A and Response B? | (Completely inconsistent, Somewhat inconsistent, Neutral, Somewhat consistent, Completely consistent) |

| P8 | Overall, how would you rate the similarity between Response A and Response B? | (Not similar at all, Somewhat dissimilar, Neutral, Somewhat similar, Extremely similar) |

| P9 | Which response is more related to the question than the other? | A or B |

| P10 | Which response represents the question? | A or B |

| Prompts | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P6 | P7 | P8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gemini scores | 4.1 | 3.9 | 4.2 | 3.9 | 4.2 | 4.5 | 4.4 | 4.3 |

The mean response scores presented in Table 4 for prompts 1–8 indicate a high degree of similarity in responses between human experts and ChatGPT. In the ground-truth dataset, prompts P2 and P4 led to very short responses from human experts, while ChatGPT has provided much more extensive replies. Further to this, these prompts assess the extent to which responses align in perspective, and since human perspectives often diverge, leading to varying levels of agreement (Surdek, 2016; Johnson, 2019). Therefore, Gemini scores refer to the fact that ChatGPT’s inferences on P2 and P4 were much clearer than those of the human experts. Gemini has indicated that the mean response score of the eight prompts is approximately 4.2 out of 5, reflecting how close response A was to response B. The evaluations of the message content (P3) and the topic argument (P5) were all above 4, as were the terminology (P6) and recommendations (P7). Prompt (P6), which measured the degree of terminological similarity, was 4.5 out of 5, reflecting a considerable alignment of responses. Overall, the outcomes of our semantic similarity analysis are robust and highly consistent, confirming the reliability of our methodology.

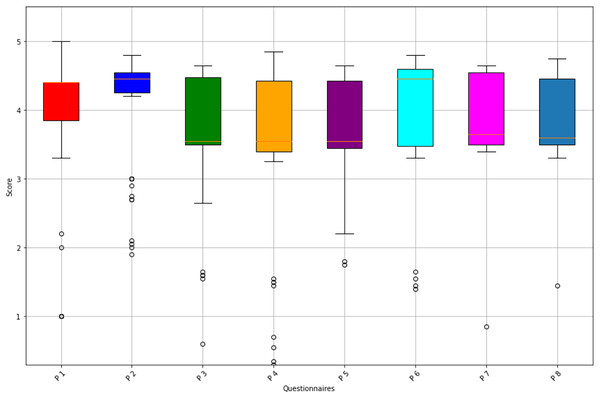

Figure 4 shows the distribution of the scores for these 8-Prompts questionnaires for the 52 questions. As we can observe from this figure, most of the scores fall within the range of 4 to 5 scales, indicating high correlations and text representations of the ChatGPT responses to the human responses. Furthermore, P9 and P10 were included for further verification of the accuracy of the ChatGPT responses.

Figure 4: Distribution of Gemini scores for the 8-Prompts Questionnaires.

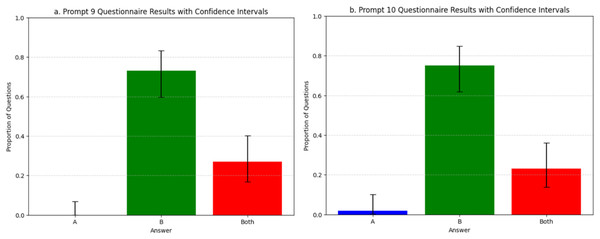

Figure 5 represents each response in three categories, i.e., “A”, “B”, and “Both”, with 95% confidence intervals that were calculated using the Wilson score interval. For P9, Fig. 5A, Gemini reported that response B, which is the ChatGPT response, was more related for 73% of the prompts. The rest of the responses were shared between both A and B. For P10, Fig. 5B, Gemini reported that ChatGPT responses represented the prompts more than human responses. This was observed by 76% of replays, which reported that B was the best, only 1% referring to A as the best, and 23% showed that both A and B represented the prompts. Since ChatGPT has contributed an additional 23% similarity across the “Both” category, this would get ChatGPT’s total representation of the responses to 99%, representing the prompts. This clearly indicates that most of ChatGPT’s responses match or outperform those of the human experts. This experiment demonstrates that the renewable energy information provided by ChatGPT was relevant and at the point, making ChatGPT a promising tool that can help improve the user experience when it comes to the renewable energy space, presenting information and supporting user inferences.

Figure 5: (A) The proportion of questions for Prompt 9. (B) The proportion of questions for Prompt 10.

Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals using the Wilson method.Although this article acknowledges ethical issues such as the potential misinformation or ChatGPT’s general training bias, we ensured any bias or misinformation was avoided by benchmarking against a manually crafted, domain-specific “ground truth” dataset sourced from authoritative renewable-energy materials. In other words, rather than comparing ChatGPT responses to an arbitrary reference, we matched them against a curated set of expert responses known to be as free as possible from common online noise or superficial framing.

Overall, OpenAI continues evolving and has released almost six versions of its GPT algorithm, starting with its first version in 2018 up to the most recent one, GPT-4 Turbo. Recognizing the critical importance of renewable energy early on, which was further emphasized through this study, ChatGPT now provides an informative guide on renewable-energy management, directly supporting one of the United Nations’ key sustainable development goals on the following link: https://chatgpt.com/g/g-WvMVuNHoF-renewable-energy. It is impressive to mention that with the evolution of ChatGPT, periodic evaluations appear feasible. This study provides quantitative measures and can serve as a baseline for potential longitudinal studies tracking ChatGPT’s progress over time.

Providing end users with reliable, carefully selected information on renewable energy using ChatGPT can fundamentally transform how individuals engage with sustainable technologies. When individuals are provided with clear, reliable responses to their prompts, they are more likely to adopt evidence-based best practices, such as optimizing solar panel orientation, adjusting load schedules to accommodate off-peak generation, or practical tips for demand-side management. This not only improves overall energy efficiency but also builds trust in renewable solutions, enabling end users to see themselves as active participants rather than passive observers. While ChatGPT has the potential to enhance public engagement with renewable energy, it is important to recognize its limitations, particularly its tendency to hallucinate, or generate information that appears accurate but is factually incorrect or misleading. Such inaccuracies may undermine user confidence and hinder the adoption of sustainable practices if not identified and corrected. Therefore, ChatGPT should be viewed as a supportive, not authoritative, tool, most effective when its outputs are verified through up-to-date, expert, and location-specific sources.

Conclusions

A new era of information generating has emerged with the disclosing of LLMs and their recent technology of conversational chatbots such as ChatGPT. This study aimed to compare the information generated through ChatGPT to human experts with a focus on renewable energy, an important domain for future sustainable development. Our research compiled 63 prompts generated by humans and the corresponding responses from various renewable energy platforms. A head to head comparison was conducted to evaluate the relevance and validity of ChatGPT responses against those of human experts using lexical and semantic measurements. Further to this, Gemini has been asked to measure the similarity between ChatGPT responses and those of human experts, proving that ChatGPT is an impressive source of information, particularly when it comes to renewable energy, with almost 99% of information representation accuracy. ChatGPT has provided insights into renewable energy across diverse aspects that complement and, in some areas, extend the human expert’s knowledge. While we recognize that larger-scale benchmarks are important for broad statistical generalization in this context, expanding to a more extensive set of prompts is therefore planned as a second phase, allowing future work to validate and extend these initial findings across a more diverse and robust dataset. Lastly, we emphasize that AI tools depend on humans and are not a substitute for them. Rather, humans can even leverage AI to assist with tasks that require intensive human effort or high computational skills.

Limitation

There may be some possible limitations that can be addressed in future work. While Word2Vec embeddings are a popular method for semantic similarity analysis, they may inherit biases from their original training sample. Moreover, incorporating more recent transformer-based models like BERT could lead to richer contextual representations. On the other hand, our handcrafted dataset appears relatively small to examine LLM-based chatbots like ChatGPT’s performance on renewable energy. Although this has been acknowledged, this study primarily serves as a proof-of-concept, and thus, larger, more diverse, and technical prompts will be required to confirm and extend our findings at expert-level or engineering-specific content.

Supplemental Information

Gemini evaluation Scores for the 52 questions and their repsonses from Human and ChatGPT according the 10-Prompts.

Each score in this file is a value that Gemini provided measuring the 10-prompts asked to it to evealuation the general similarity between the Human expert response to reneable energy question anf ChatGPT response.

Dataset.

This dataset contains a curated collection of questions related to renewable energy sourced from diverse online platforms, along with corresponding expert (human) answers and AI-generated responses produced by ChatGPT. The primary aim of the dataset is to enable researchers to explore, analyze, and evaluate the quality, accuracy, and relevance of AI-generated responses in comparison to those provided by domain experts. The dataset supports research in natural language processing (NLP), AI alignment, renewable energy communication, and question-answering systems.

This file is a link to kaggle code and all datasets used in this research.

the file includes a link to Kaggle repository.