Dynamic adversarial neural cryptography for ensuring privacy in smart contracts

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Giovanni Angiulli

- Subject Areas

- Artificial Intelligence, Cryptography, Software Engineering, Neural Networks, Blockchain

- Keywords

- Adversarial neural cryptography, Generative adversarial networks, Smart contracts, Blockchain, Cryptography

- Copyright

- © 2025 Hanafi et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2025. Dynamic adversarial neural cryptography for ensuring privacy in smart contracts. PeerJ Computer Science 11:e3286 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3286

Abstract

Various types of research are being carried out to advance in the field of cryptography and develop a more robust technique for security. Adversarial neural cryptography (ANC) is a recent development in this extension, which possesses huge potential to be implemented in various domains. There is a continuous need for the development of more adaptive techniques to secure data while in communication using deep learning and other applied artificial intelligence techniques, which serves as the motivation for this work stems from the increasing need for adaptive, robust encryption mechanisms to address the limitations of traditional cryptographic techniques in securing sensitive blockchain transactions. This article proposes a new approach for the protection of private smart contracts on blockchain systems via ANC. The proposed method in the research is dynamic adversarial training using three neural networks to secure smart contract transactions. It optimizes the encryption and decryption processes against evolving cyber threats. The algorithm strives to attain a high key agreement rate (KAR) and a lower Eve’s decryption failure rate (EDFR) eventually proving its efficacy in attaining privacy and security in blockchain applications and adaptability. This research will incite more studies on ANC and its practical implementations in ensuring private smart contracts and overcoming the present cryptographical approaches with significant development because of their potential.

Introduction

The increased dependence on decentralized systems and blockchain (Zhao, 2019) has led to transaction and agreement execution fundamentally changing how it all happens in terms of safety, transparency, and immutability. In fact, even though robust infrastructure exists on blockchain platforms like Ethereum for smart contracts, they face some serious issues relating to privacy and security. Traditional public blockchain networks expose all this transaction data, which is a risk when sensitive information is involved. On a more practical note, as more sectors of such industries as finance, healthcare, and supply chain management begin to adopt blockchain technology (Wang et al., 2019), it becomes an absolute necessity to protect the confidentiality of such transactions.

Smart contracts are self-executing contracts written with the terms of an agreement directly into code. One of the critical components of blockchain is that it ensures both trust and automation in a decentralized environment, and within the very same structure lies an inherent transparency that may expose critical data (Sharma, Jindal & Borah, 2023). So, possibility-wise, their vulnerability to unauthorized access or attacks is a possibility. These problems were solved by private smart contracts that allowed sensitive transactions to be carried out in a more controlled and confidential environment. Although several cryptographic methods have already been adapted to secure smart contracts, such as symmetric and asymmetric encryption, the increasing complexity of cyber threats has motivated research into advanced and adaptive approaches. Among these, adversarial neural cryptography (ANC) has emerged as a promising direction; however, it remains an exploratory technique without established security guarantees, particularly when compared to more rigorously analyzed post-quantum primitives such as lattice-based cryptography.

In the context of this research, on the side of the development of blockchains, there lies ANC, an emerging field that constructs neural networks and cryptography into each other (Abadi & Andersen, 2016). Hence, here it is a promising approach to the improvement of the security of private smart contracts (Kumar et al., 2024). ANC employs adversarial training between neural networks-there are usually three entities namely encoder, decoder, and adversary-to dynamically evolve encryption methods able to resist sophisticated attacks. This approach brings about a self-adaptive framework that continues to enhance its capabilities in protecting communications (Coutinho et al., 2018). Potentially, this shows a solution to the limitations of traditional cryptographic techniques.

This article proposes adding the concept of ANC to secure private smart contracts on blockchain platforms. The main contribution of this article would be the development of an algorithm that applies ANC for improvement in smart contract transaction executions as having more desirable privacy and security properties than traditional encryption methods by offering resistance to advanced cyber threats through a dynamic adversarial training methodology involving multiple neural networks.

The major contributors to the security of smart contracts include traditional cryptographic techniques, including symmetric encryption, homomorphic encryption, and zero-knowledge proofs. However, these methods suffer from several inherent drawbacks such as static encryption mechanisms and high computational costs that limit their adaptability to emerging cyber threats. This research aims at building on the foundation developed in ANC, by constructing a dynamic adversarial training framework for smart contract security. In contrast to basic ANC, which is often oriented towards generalized secure communications, the developed method would specifically introduce an algorithm to the domain of secure private contracts within blockchain environments. Enhancements consist of optimized adversarial training frequencies, noise resilience integrated to prevent the adversary Eve from decrypting data, and a structured test framework that can achieve a 98% key agreement rate (KAR). These advances bring forward the proposed approach, as it is not only computationally efficient with 10% overhead compared with existing cryptographic systems like Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) and Rivest–Shamir–Adleman (RSA) but also is significantly more robust against an adversary.

The market for smart contracts is exponentially growing, having already exceeded the value of $300 billion (George, 2024) at the beginning of the previous year. However, such growth has opened massive security risks. In the first half of 2023, hackers stole nearly $750 million using vulnerabilities in smart contracts. These contracts often depend on external data, and audits have shown that on average, 117 external data accesses occur per project, while some have even reached as high as 11,724. Such extensive dependence increases the possibility of security breaches. In addition, the complexity of building smart contracts correctly means that even minor coding errors can lead to severe consequences, such as unauthorized access and substantial financial losses (Scharfman, 2024). Historical incidents like the DAO hack in 2016 and theft through Parity Wallet in 2017 remind us of the existing costly flaws in today’s smart contract systems.

The growing sophistication of cyber-attacks against blockchain systems, and the sensitive nature of the transactions within smart contracts, highlight the need for cryptographic solutions that are adaptive and resilient. Existing ANC frameworks, even though effective for generic tasks associated with encryption, do not provide particularly specific optimizations for blockchain use cases in terms of security, especially in maneuvering private smart contracts. The motivation to create this work stems from filling in these gaps, as the ANC model would be designed specifically with the blockchain’s specific needs in mind, including dynamic adversarial attacks and transaction privacy. The proposed model doesn’t only incorporate adversarial training but also focuses on practical issues, such as ensuring that smart contracts cannot be changed during adversarial retraining cycles. This work extends the traditional ANC methodology to a self-adaptive encryption framework by introducing such innovations as periodic weight updates and noise augmentation so that the system is able to handle real-time and dynamic threat landscapes in decentralized applications. The following are the main contributions of this Research:

Dynamic encryption framework: The article presents a novel dynamic adversarial neural cryptography model that is developed to improve the security and privacy aspects of private smart contracts on blockchain networks.

Innovative algorithm design: This article proposes a customized algorithm where adversarial training among three types of neural networks—encoder Alice, decoder Bob, and adversary Eve—are optimized to establish strong encryption with cyber threats that are sophisticated in nature.

Enhanced resilience: The research model demonstrates considerable resilience in withstanding adversarial attacks and thus counteracts the notion of adaptability over static conventional cryptography methods.

Adaptability and scalability: The dynamic adversarial training mechanism makes sure that the model will learn to adapt to changes in the landscape of cyber-attacks while at the same time being scalable enough for practical use in decentralized systems with a high Value of Key Agreement Rate.

Comparative evaluation and practical insights: This Research presents a detailed comparison with conventional cryptographic methods being used for Smart Contracts over the trade-off between computational overhead and security, and provides some practical guidelines on ANC adaptability in the real-time environment for blockchain.

This article is further organised as follows: The Introduction section offers an overview of the research and its objectives. The Related Works section discusses prior studies on smart contract security and highlights the significance of privacy in blockchain technology. The Materials and Methods section details the proposed ANC approach and its application in securing private smart contracts. The Results section presents the performance evaluation of the proposed algorithm using key metrics such as the key agreement rate (KAR) and Eve’s decryption failure rate (EDFR). The Discussion section provides insights into the obtained results and includes a comparative analysis with existing research. Finally, the Conclusion section summarizes the study’s findings, addresses current challenges and limitations, and outlines potential directions for future research in integrating ANC with blockchain technology.

Smart contracts and their usage in emerging digital ecosystems

Smart contracts are among the key innovations of blockchain technologies (Allam, 2018). A smart contract may be defined as an autonomous code snippet incorporating the terms, conditions, and obligations existing in a contract and executed on a distributed ledger. Smart contracts are distinct from traditional contracts as they execute automatically once pre-specified conditions have been satisfied. The deployment of a smart contract goes through verification and is inscribed on a distributed network of nodes, thereby ensuring consensus, transparency, and unalter ability.

Technically, smart contracts typically consist of functions, state variables, and events programmed with domain-specific languages such as Solidity (Ethereum) or Vyper (Kaleem, Mavridou & Laszka, 2020). Once deployed, the contracts can no longer be altered at will due to the nature of immutability of blockchain technology. Although this attribute improves reliability, it also creates some level of rigidity, making upgrades and remedying vulnerabilities more complex. The immutable nature of smart contracts ensures contractual terms are not tampered with; however, this also means that any inherent flaws or security weaknesses are left intact once the contract is posted on-chain. The flexibility of smart contracts has led to their use in a wide range of industries:

Finance and decentralized finance (DeFi): At the heart of decentralized exchanges, automated market makers, lending protocols, and investment products, including systematic investment plans (SIPs), are smart contracts. By eliminating or minimizing intermediaries, these contracts lower costs, facilitate instantaneous settlement, and expand access to financial products (Schär, 2021; John, Kogan & Saleh, 2023).

Supply chain management: Payments are made automatically with confirmation of delivery, quality validation is enforced through Internet of Things (IoT) sensors, and tamper-proof records of goods movement are generated. It is done in a more transparent, less fraudulent, and quicker logistics processes (Bottoni et al., 2020).

Insurance and healthcare: They are utilized to handle safe patient data transfer, automate claims processing, and authenticate clinical trial processes. Blockchain transparency and automation together can cut down on inefficiencies in healthcare systems (Omar et al., 2021).

IoT and energy uses: Decentralized trading of energy using smart contracts enables peer-to-peer selling of electricity, prices are automated, and microtransactions are paid between devices (Aloqaily et al., 2020; Moudoud, Cherkaoui & Khoukhi, 2022).

Intellectual property and digital identity: Smart contracts facilitate secure control of digital identities, authentication credentials, and intellectual property rights including licensing arrangements and royalty payments (Ferro et al., 2023).

Such applications prove that smart contracts are not specific to financial transactions but are a general-purpose tool for automating trust across disparate digital environments. Though they have the potential to transform, smart contracts come with daunting challenges of paramount importance that directly propagate the urgency for more powerful cryptographic mechanisms.

-

All contract code and state variables are exposed to all nodes in a public blockchain like Ethereum. Transparency is ensured but confidentiality is sacrificed. Sensitive data (e.g., financial decisions, health records, business rules) can leak or be reverse-engineered.

-

Even if direct data exposure is avoided, malicious actors can infer private data from transaction traces, contract outputs, or event logs. For example, finance contracts may reveal investor actions, and supply chain contracts may reveal competitive strategies.

-

Deployed contracts are immutable, so that once a vulnerability or outdated design is found, it cannot be fixed without deploying a completely new contract. This may be a benefit in establishing trust, but rigidity makes adaptive security especially difficult.

-

Solutions like homomorphic encryption, secure multi-party computation, or zero-knowledge proofs give good guarantees but are computationally intensive, so their practical application in throughput-constrained blockchain settings is limited.

-

When blockchain networks are large, it can result in delays and increased transaction costs (e.g., Ethereum gas) to perform sophisticated smart contract logic or cryptographic computations.

Under these constraints, protecting confidentiality in smart contracts needs to be revolutionary with respect to striking a balance between security and efficiency. ANC (Hanafi, Bokhari & Khan, 2024) offers an innovative solution by making it possible for models to learn encryption–decryption protocols dynamically under the guidance of an adaptive adversary. In contrast to static cryptographic building blocks, ANC improves over time through the training of Alice and Bob (communicating parties) against Eve (the attacker), creating adaptive, task-specific encryption that changes with the threat.

In this work, smart contracts are framed as the underlying motivation for deploying ANC. By protecting the confidentiality of contract information and execution logic, ANC solves the transparency–confidentiality dilemma implicit in blockchain. Additionally, the use of noise-hardened adversarial training as well as light-weight fully connected architectures guarantees that the solution is computationally tractable with only small overhead. Notably, to balance immutability with adaptability, we introduce a blockchain-compatible deployment model, where encryption models are retrained off-chain and reintroduced in version-controlled updates without altering the underlying contract logic. Smart contracts augment the strengths of blockchain technology by facilitating automation, trust minimization, and transparency in a wide range of industries. Their effectiveness is, however, challenged by confidentiality risks, immutability problems, and computational compromises that are a characteristic of classical cryptography methods. With the addition of adversarial neural cryptography, this study contributes a dynamic, adaptive, and powerful means of protecting smart contracts from adaptive adversarial attacks. This positions smart contracts not only in a core application field but also at the forefront as a driving force for neural cryptographic research to advance.

Contributions and challenges addressed

Smart contract confidentiality in blockchain settings needs adaptive and efficient cryptographic mechanisms. This research makes progress in ANC through the introduction of a learning-based encryption-decryption model that is responsive to adversarial activity with an emphasis on practical deployability. The main contributions of this research are as follows:

-

This research aims to design and implement an end-to-end ANC framework in which Alice and Bob collaboratively learn an encryption–decryption mechanism, while Eve acts as an adaptive adversary attempting to compromise communication. The architecture is specially designed for 32-bit smart contract payloads and encryption keys, thus showcasing flexibility in adapting to blockchain applications where transaction-level privacy is required. The architecture is specifically optimized for 32-bit smart contract payloads and encryption keys, thereby demonstrating versatility in conforming to blockchain use cases where privacy at the transaction level is needed.

-

Adversarial learning with three agents is notoriously unstable and prone to collapse. To overcome this, the proposed framework introduces two stabilization mechanisms: (i) an asymmetric training cadence in which Alice–Bob is updated more frequently than Eve, and (ii) noise-hardened ciphertexts generated through Gaussian perturbations. These controls guarantee consistent convergence, fend off Eve’s takeover during training, and enhance the resilience of the learned cryptographic scheme.

-

Experimental evidence reveals that the proposed model has a high rate of key agreement between Bob and Alice, yet, simultaneously, a high rate of decryption failure for Eve. Significantly, these gains are with relatively low extra computational overhead than in classical symmetric baselines, thereby compromising robust security guarantees with actual practicality in blockchain applications.

-

A distributional analysis of the encrypted outputs shows nearly uniform ciphertext histograms, a characteristic which minimizes structural leakage and maximizes resilience against statistical exploitation. This demonstrates the system to approximate semantic-style security above and beyond traditional reconstruction error metrics.

-

Given the immutability of deployed smart contracts, we suggest a deployment path where the encryption component gets retrained off-chain and re-deployed in a versioned fashion. This allows the privacy layer to adapt against new adversarial attacks while maintaining the immutability of the core business logic and state.

The above was accomplished through systematically solving a number of technical issues that have long held back the development of ANC in decentralized settings. In particular, the framework alleviates adversarial training instability by scheduling and injecting noise, minimizes ciphertext leakage threats through distributional hardening, ensures a best balance of adversarial power by adapting Eve’s capacity and learning rate, aligns immutability requirements with flexibility through retraining mechanisms, and promotes computational efficiency using light-weight fully connected networks. This study shows that adversarial neural cryptography can be made viable for securing smart contracts with robust confidentiality, adaptability, and efficiency. Through the synthesis of technical innovation and empirical proof, it adds to the larger literature on neural cryptography and lays the ground for eventual integration into blockchain systems.

Related works

In recent years, research on advanced technologies for securing smart contracts has been an area of great interest with continuous developments. Researchers around the world are working to develop methodologies for enhancing the privacy, security, and reliability of private smart contracts for robust implementation, since smart contracts are significantly important in the broader domain of blockchain applications and adaptability. Numerous innovative cryptographic techniques and algorithms were developed and researched, ranging from zero-knowledge proofs to homomorphic encryption and multi-party computation, which are implemented to tackle inherent vulnerabilities among smart contracts, enhancing their Applicability. The initiatives intend to eliminate such risks, such as unauthorized access and breaches, data, and systemic flaws, that can lead to compromises in blockchain-based systems.

In this context, the research primarily aims to identify and fill the existing gaps in securing smart contracts, which is critical to developing improvements for extending this domain. This research will be positioned towards contributing by taking advantage of ANC as a new approach for private smart contract security. The research seeks to develop a robust framework through the systematic analysis of existing methodologies and their limitations by overcoming the challenges posed by traditional cryptographic solutions. The exploration of adaptive and resilient encryption mechanisms, which highlights the potential of ANC to address the evolution of cyber threats, will ensure the secure execution of smart contracts in decentralized environments.

Pranto et al. (2021) investigate blockchain, IoT, and smart contract integration for smart agriculture with a focus on pre-harvest and post-harvest operations. Their framework utilizes IoT sensors for environmental parameter monitoring in real-time and Ethereum smart contracts for automating traceability, pricing, and distribution. Although the research shows novelty through an event-driven logging working prototype and gas cost analysis, the study’s simulation over actual deployment restricts practical generalizability. The authors also recognize issues like excessive gas fees, sensor attack vulnerabilities, and immutability of data as challenges. Areas for future work are deployment on permissioned blockchains, artificial intelligence (AI)-based anomaly detection, and integration with consumer transparency tools, making their research a basis for blockchain-based agricultural traceability.

Wang et al. (2024) introduce Ext-ttg, a deep learning framework aiming to solve the issue of multi-label smart contract vulnerability detection complexity. By combining Transformer–bidirectional gated recurrent unit (Transformer-BiGRU) models with extractive summarization, their method optimally handles long opcode sequences and demonstrates higher detection performance than traditional models. The system proved to have a micro-F1 of 82.48% and lower Hamming Loss, confirming its technical stability. Nevertheless, scalability in real-time applications, unexplainability, and specificity to Ethereum smart contracts continue to be major limitations. The research proposes future work in cross-chain data sets, explainable AI paradigms, and lightweight architectures, making Ext-ttg an innovator but improving solution to blockchain security.

Alkhazi & Alipour (2023) propose a multi-objective optimization framework for testing smart contracts with concerns for cost, efficiency, and reliability in blockchain applications. Employing NSGA-II, their approach strikes a balance between code coverage, gas expenditure, and execution time, exhibiting better results across case studies of major platforms such as Chainlink and PancakeSwap. The work sets the value proposition of Pareto-optimal solutions in lowering redundant tests while preserving fault detection ability. Its validity is, however, limited to Solidity and Ethereum-based contracts, thus limiting broader applicability to other platforms. Revisions like reinforcement learning–based dynamic optimization, cross-platform verification, and augmented fusion with runtime monitoring would enhance applicability. The research contributes to testing practices by transcending mono-objective approaches towards overall optimization.

Swetha & Prathap (2025) interest lies in secure sharing of big data using an Ethereum-based smart contract system that integrates a dilated weighted recurrent neural network (DW-RNN) with a hybrid crypto system. By interweaving elliptic curve cryptography with ElGamal encryption and maximizing key management via MBERSO, the architecture provides better authentication, accuracy, and confidentiality than traditional models. Though with promising findings, the work is bounded by use of simulated healthcare datasets and no validation across heterogeneous, real-world settings. Scalability within high-throughput blockchain settings and also in the absence of adversarial testing highly limit practical application. Extensions for future work are federated learning to ensure privacy-preservation, explainable AI (XAI) incorporation for interpretability, and adherence to regulatory standards like General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Their research points to an important step forward in integrating blockchain with AI for trusted data management.

Munaganuri, Yamarthi & Bolem (2025) introduce an integrated smart agriculture model that combines IoT soil moisture sensing with predictive analytics, blockchain, and reinforcement learning. Their method showed measurable benefits, such as a 20% decrease in water consumption and a 12% increase in crop yield in field tests, highlighting its potential for sustainable irrigation. Utilization of Hyperledger Fabric for immovable data storage and smart contracts to automate increases scalability and transparency. Nonetheless, the validation of the framework was confined to maize plants and particular environments, which is a concern regarding its generalizability. Computational power, energy expenditure, and adoption limitations also limit deployment in resource-poor settings. Future enhancement could be through lightweight AI models, fusion with satellite and drone data, and hybrid blockchain techniques for enhancing scalability. This contribution is notable for its holistic integration of blockchain, IoT, and AI, though further work is needed to broaden generalizability and enhance socio-technical adoption.

Kosba et al. (2016) performed a scientometric analysis of IoT-based air quality monitoring using publication trends, eminent authors, institutions, and keyword networks to identify emerging themes in the field. Their results point to the accelerated development of low-cost sensors, AI calibration, and networked monitoring systems, connecting these to wider smart city and sustainability agendas. Yet the research is founded primarily on quantitative bibliometric measures and a single database, excluding regional contributions and limiting qualitative observations. There is a need for future research incorporating multiple databases, empirical tests, and cross-disciplinary approaches for improving practical relevance.

Yuan et al. (2018), investigated IoT-based frameworks coupled with machine learning for environment monitoring, which is air pollution measurement. The research illustrates how computational models integrated with data obtained from sensors enhance prediction accuracy and responsiveness of the system. Notwithstanding its contribution, the research is based on testbeds at a limited scale and does not consider device interoperability, power consumption, and security of data. Future studies may emphasize large-scale validations, low-power edge computing, and multi-source data fusion to support enhanced predictive performance and sustainable deployment.

Yuan et al. (2018), used machine learning models to forecast urban air quality based on environmental sensor data, presenting regression and ensemble algorithms that performed better compared to statistical baselines. Their experimental setup prioritizes real-time applicability, which is of particular importance to smart city planning. However, the data set is geographically limited, lowering generalizability, and insufficient focus on noisy real-world data and explainability of the model. Larger data sets across regions, using cutting-edge temporal models such as long short-term memory (LSTM), and incorporating explainable AI would enhance robustness and policy relevance.

Solomon, Weber & Almashaqbeh (2023) applied deep learning to medical image analysis with an emphasis on the detection of cancer using CNNs with transfer learning. Their tests had greater diagnostic performance than the typical models and showed the utility of transfer learning in managing limited medical data. Nevertheless, the diversity of the dataset used in the study is low and thus its generalizability is questionable, while issues concerning interpretability and computational cost are not addressed. Future studies must involve multi-center datasets, explainable AI techniques, and light CNN models optimized for clinical applications so as to enhance translational value in healthcare.

As Qi et al. (2024) systematically reviews privacy-preserving smart contracts (PPSCs), focusing on two primary approaches: cryptographic tools and trusted execution environments (TEEs). They classify the most advanced approaches into two categories, namely crypto-based and TEE-based PPSCs, giving a comprehensive analysis of each scheme’s strengths, weaknesses, and challenges. The cryptographic solutions involved include zero-knowledge proofs and multi-party computation. These are known to have strong privacy guarantees but raise many issues concerning the efficiency and scalability of such solutions. TEE-based approaches, such as Intel SGX, provide better performance yet are always associated with hardware trust assumptions. The article points out the major challenges faced in implementing a PPSC, such as preserving privacy during multi-party transitions and enabling efficient generation of proofs, and it furnishes some directions on how to make the system more private, scalable, and user-friendly for future research.

Jiang et al. (2024) propose a new type of privacy-preserving smart contract named Regulatable Privacy-Preserving Smart Contracts, particularly suited to account-based blockchains. The proposed scheme is provided in the form of a two-layer commitment structure, in which the detailed fine-grained privacy protection is accomplished with the flexibility for selective disclosure of private data and flexibility for states of transition from private to public data and vice versa. The authors also integrate a zero-knowledge proof system with public-key encryption, enabling the system to maintain privacy, soundness, and traceability, while allowing regulators to reveal private data under specific conditions. The system’s performance was evaluated on applications such as blind auctions and electronic voting, demonstrating its practicality and effectiveness in real-world blockchain implementations.

Kosba et al. (2016) proposed a cryptographic framework to achieve privacy and fairness in blockchain transactions with special attention to the auction sealed-bid case. Here, concealing user transactions while ensuring fairness over the smart contracts is considered. Zero-knowledge proofs and others ensure correctness in the outcome of the transaction without leaking sensitive information. This system proved safe against a variety of adversarial models and showed its efficiency in reducing transaction costs and computational overhead in blockchain networks.

Aslam, Tošić & Mrissa (2021) offers a detailed analysis of the privacy and security challenges in blockchain systems with proper justification for secure and privacy-aware design. Some of the key requirements are protecting transaction data, protecting user identity, and other security-related properties such as confidentiality, integrity, and availability. This article describes existing mechanisms, including ring signature, zero-knowledge proof, and homomorphic encryption, with a comprehensive description of benefits and limitations. In addition to these classifications of different blockchain attacks with countermeasures, the recommendations for designing privacy-preserving blockchain systems are set out. The authors have charted out the future research track toward solving scalability, efficiency, and privacy issues in current blockchain technologies.

Li et al. (2023) propose Nereus, an anonymous and secure ride-hailing service including private smart contracts and Software Guard Extensions (SGX)-based technology to boost privacy and security within such services. Among some of the significant challenges that the study attempts to overcome lies the fact of collusion attacks between ride-hailing service providers (RHSP) and drivers that may breach the anonymity of riders. Nereus brings a mechanism for privacy-preserving matching using Bloom filters and Merkle proofs to ensure an efficient and verifiable matching procedure for users. Anonymity is maintained through short group signatures in anonymous authentication and also commitments for deposits enabling accountability for misbehavior on the part of drivers. The authors demonstrate the utility of Nereus with a prototype implementation on the Ethereum network, coupled with an extensive performance analysis clearly demarcated to show computational efficiency over previous systems.

Yuan et al. (2018) present ShadowEth, a system envisioned to provide privacy preservation for smart contracts executing on public blockchains, such as in the case of Ethereum, using hardware enclaves. TEEs combined with public blockchain verification preserve the confidentiality of smart contract executions, ensuring integrity and availability, as seen in the case of ShadowEth, where execution of private smart contracts offloads in secure off-chain environments, while all on-chain verification processes take place. They show several use cases demonstrating the applicability of ShadowEth, namely private voting, transaction protection, and auctions. They implemented their system using Intel SGX and provided several security analyses to demonstrate common attacks that the system resisted.

Apart from symmetric and asymmetric cryptographic techniques, other techniques are also being maneuvered for the cause. Sánchez (2018) present Raziel, multi-party computation (MPC)-based system wherein Proof-Carrying Code (PCC) is incorporated to enable private and verifiable smart contracts on blockchains. The same framework offers concomitant privacy and correctness by keeping contract information secret while facing the same kinds of attacks as seen in the DAO and Gyges attacks. Here, a new application of non-interactive zero-knowledge proofs is presented to validate smart contracts to third parties without disclosing contract details. They also introduce an incentive scheme for pre-computation of data by miners so that some computations on that data may be rendered safely further optimizing the efficiency of the system. Real-world feasibility is shown through examples like private crowdfunding and double auctions based on Raziel.

Avizheh, Nabi & Safavi-Naini (2024) provides an approach for outsourcing verifiable computation, called Refereed Delegation of Computation (RDoC), based on the use of smart contracts. It allows weak clients to delegate their own computation to some untrusted servers while ensuring the correctness of the obtained result, thanks to replication and verification by the third-party smart contract acting like a referee. They propose security models within the universal composability (UC) framework, addressing challenges in copy attacks where malicious servers’ duplicate results obtained from honest servers. Both protocols are intended for two-server and multi-server scenarios, which include formal security proofs. The authors provide an efficiency analysis and an implementation via Ethereum to show the feasibility of the system for decentralized computation.

Zhang et al. (2024) introduce a blockchain-based proxy-oriented data integrity checking mechanism in cloud-assisted Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS). The data integrity checking mechanism is an important aspect of data integrity for the storage in the cloud, especially traffic control information, where tampering with the same or making any alteration could lead to extreme consequences. Further, in this mechanism, the computation overhead of the data manager is saved as the task of integrity-checking may be outsourced to a proxy. This ensures complete transparency within the system because a process cannot accommodate malicious behaviors detrimental to its integrity. The proposed mechanism is based on homomorphic hash functions and polynomial encapsulation techniques and this improves efficacy and security toward effective performance in real-time ITS environments.

Research is also being carried out to establish a base of the current scenario for the developments carried out so far in this direction of research. Hewa et al. (2021) have performed an extensive survey on blockchain-based smart contracts, with an emphasis on technical matters and future research areas. The article has focused on decentralization, immutability, and cryptographic security of blockchain as key features. This article discusses some of the critical issues regarding the security, privacy, cost of gas, and concurrency of smart contract programming languages such as Ethereum and Hyperledger Fabric. Besides that, it also elaborates on common vulnerabilities of security, such as reentrancy attacks, underflow/overflow errors, and double-spending attacks. Lastly, the article concludes by demonstrating possible future research areas that will integrate smart contracts with artificial intelligence and game theory to make them even more powerful and scalable.

Steffen et al. (2022) introduce a ZeeStar-anonymity-preserving smart contract system designed to let developers write private smart contracts without deep cryptographic expertise. It does this by combining the existing zkay language with Non-Interactive Zero-Knowledge proofs (NIZK) and homomorphic encryption. ZeeStar can thereby operate on foreign data that previous systems could not operate efficiently on. The system supports applications including private payments, oblivious transfers, and token transfers on the Ethereum blockchain. With regard to the evaluation of the system, it is practical with a feasible gas cost and has scalability across various smart contract applications.

Alupotha & Boyen (2022) propose a novel zero-knowledge protocol for smart contracts called Confidential Integer Processing (CIP), which aims to be used for the sake of private multi-party computations, namely, confidentiality-preserving transactions. The proposed protocols of CIP, namely CIP-DLP and CIP-SIS will offer not only interparty but also intraparty privacy with no dependency on trusted hardware. These protocols provide efficient zero-knowledge proofs for operations like addition, multiplication, and comparison, and they are secured under the UC framework. The authors demonstrate that their approach improves privacy and security for blockchain applications, such as escrow mechanisms and federated learning, by maintaining confidentiality while still enabling verifiable computations.

Solomon, Weber & Almashaqbeh (2023) propose smartFHE-a new framework for privacy-preserving smart contracts with data under encryption using Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE). It is architected to enable computations on private data encrypted on such without putting burdens on end users. Instead, the computations are carried out in the blockchain by miners on encrypted inputs and concurrently verified for correctness based on zero-knowledge proofs (ZKPs). The authors discuss challenges that FHE poses towards efficiency and concurrency in blockchain environments and prove how smartFHE can be applied for various use cases like private payments and decentralized applications. Performance evaluations prove that smartFHE is scalable and efficient enough to be used by lightweight users in blockchain settings.

To address the usage of zero-knowledge proofs, Lavin et al. (2024) present a sweeping survey of the use cases of ZKPs, which puts more emphasis on the flexibility of privacy and the computational integrity of the most diverse application domains. There, the authors explain how ZKPs, specifically zk-SNARKs, quietly incorporated blockchain technologies to boost privacy, scalability, and interoperability. Further, they also discuss non-blockchain applications like voting systems, authentication, and machine learning. The article concentrated on foundational components of the ZKP infrastructure, with a focus on zero-knowledge virtual machines (zkVMs) and domain-specific languages (DSLs). The article focuses on the growing importance of ZKPs in future cryptographic practices and digital privacy, such that they represent an essential avenue for developing secure, privacy-preserving technologies.

Hence, all the above-mentioned research in this section can be applied to achieve privacy-preserving smart contracts, confidential computing for smart contracts, smart contracts with homomorphic encryption, multi-party computation, and attribute-based encryption. For a quick contrast comparative analysis of all the cryptographic techniques being utilized can be observed in Table 1.

| Technique | Privacy level | Performance | Scalability | Complexity | Security | Cost | Compatibility | Standards | Maturity | Use cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homomorphic encryption | High | Low | Medium | High | High | High | Medium | Emerging | Early | Financial transactions, healthcare data |

| Zero-knowledge proofs | High | Medium | High | High | High | Medium | Medium | Emerging | Early | Voting systems, identity verification |

| Multi-party computation | High | Low | Medium | High | High | Medium | Medium | Emerging | Early | Financial transactions, data sharing |

| Attribute-based encryption | Medium | Medium | High | Medium | High | Medium | Medium | Emerging | Early | Access control, data sharing |

| Confidential computing | High | Medium | Medium | Medium | High | Medium | Medium | Emerging | Early | Data-intensive applications, financial transactions |

| Ring signatures | Medium | Medium | High | Medium | High | Medium | Medium | Established | Mature | Anonymous transactions, voting systems |

| Group signatures | Medium | Medium | High | Medium | High | Medium | Medium | Established | Mature | Anonymous transactions, voting systems |

| Blind signatures | Medium | Medium | High | Medium | High | Medium | Medium | Established | Mature | Anonymous transactions, e-voting |

| Deniable encryption | Medium | Medium | High | Medium | High | Medium | Medium | Established | Mature | Privacy-preserving communication |

| Steganography | Low | High | High | Low | Low | Low | Medium | Established | Mature | Data hiding, covert communication |

As all the techniques can be analyzed based on various parameters in this section, after a confined tabular comparison, giving a spectrum of applicational research advancements to secure private smart contracts. This section provides an in-depth review of existing methods currently available for securing private smart contracts. Though the approaches discussed here are useful, several research gaps can be identified that served as a base for this research are listed below:

-

(1)

Zero-knowledge proofs and homomorphic encryption are computationally expensive cryptographic methods, which limit their applicability in high-throughput blockchain environments. In parallel, TEE-based solutions, though efficient, rely on specialized hardware, which restricts their scalability and accessibility in decentralized systems.

-

(2)

Traditional cryptographic and TEE-based techniques are not responsive to new cyber threats that dynamically evolve. It’s a static nature that makes a sophisticated attack inevitable in fast-moving environments.

-

(3)

Most existing methods, like MPC and homomorphic encryption, suffer from exceedingly high computational overheads, indicating that such overheads are impractical for real-time blockchain applications where efficiency is crucial.

-

(4)

Both secure enclaves and ZKPs do not seamlessly fit with existing blockchain platforms, partly because they require more resources to function and operate based on frameworks or hardware specificities.

This thus underscores the imperative of innovative solutions to address gaps that are presently created by their lack of scalability, adaptability, and efficiency in securing smart contracts dynamically. This proposed research on ANC addresses several of these concerns through a novel, dynamic, and self-adaptive framework that leans on adversarial training to fortify security on blockchain-based smart contracts. Unlike traditional adaptabilities, the proposed Research in this article is built to adapt as new threats arise. This gives rise to a fresh approach to attaining scalable, efficient, and resilient encryption for decentralized applications through ANC. It fills an essential gap in the current landscape of research related to blockchain security solutions. As one of the attempts to fill up that void, ANC finds its potential way to secure private Smart Contracts, which serves as a perfect research gap for this research. To carry on the implementation of securing private smart contracts, a novel algorithm is needed to be developed in methodology, which will be discussed in the upcoming sections on methodology.

Materials and Methods

Methodological implementation of adversarial neural cryptography to secure private smart contract

This section elaborates on the methodology adopted to include adversarial neural cryptography in private smart contracts, including its architecture, training of the adversarial model, and mathematical groundwork behind its encryption/decryption algorithms. In addition, the research outlines how Google Colab (Bisong, 2019) is used for implementation in Python Software Foundation (2016), to carry out the presented algorithm for evaluating the ANC model in securing smart contracts.

Adversarial neural cryptography and smart contract adaptability

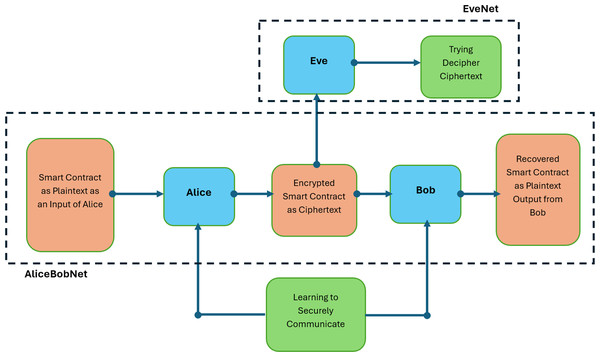

ANC uses three interacting neural networks—Alice (encoder), Bob (decoder), and Eve (adversary)—to secure private communications. In the general idea of ANC, the objective of Alice and Bob is to communicate securely by sharing encrypted messages, while Eve attempts to decrypt the messages without the shared secret key. Here, that message will be the smart contract in this research. The adversarial setup allows the encryption-decryption process between Alice and Bob to be continuously improved, with the security level of this process growing over time. In the original scenario of ANC, the plaintext message was encrypted by Alice, and then Bob and Eve try to decrypt it on their respective side, where all these three are neural networks. Here, In this scenario, the plain text message will be the smart contract which will be encrypted by Alice and decrypted by Bob and Eve. The core components of the ANC framework in the context of this Research are:

Alice (encoder): Encryption of the message for the smart contract using a shared key.

Bob (decoder): Deciphers Alice’s message with a shared secret key.

Eve (adversary): Intercept and decrypt the message without having the key.

Mathematically, the process of communication between Alice and Eve is described as Alice applies the encryption function EA(P,K) to the plaintext P specifically the smart contract, using the secret key K. The result is the ciphertext C:

(1) Bob then applies the decryption function DB(C,K) using the same key K to recover the original plaintext, which is the original smart contract:

(2) where is Bob’s reconstructed message.

Eve, with access only to the ciphertext C, attempts to reconstruct P by using her decryption model DE(C), aiming to minimize the difference between her predicted plaintext PE and the original message (smart contract) P:

(3) The objective of Alice and Bob is to minimize the difference between the original plaintext P (smart contract) and the decrypted message, decrypted smart contract be Eve, P′, while Eve tries to minimize the difference between P and her decrypted message PE. Hence, the error for Alice and Bob is calculated using the mean squared error (MSE)

(4) where N is the length of the smart contract, Pi is the original contract, and is the decrypted message, decrypted smart contract be Eve, by Bob. Similarly, Eve’s error is measured by:

(5) where PEi is Eve’s decrypted smart contract.

The goal of training Alice and Bob’s network is to minimize MSEAB, while Eve tries to minimize MSEE. To ensure secure communication, Eve’s decryption accuracy should remain low, while Alice’s and Bob’s should remain high.

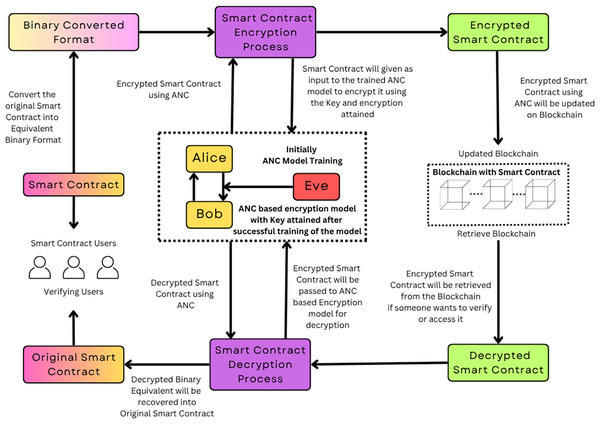

The interactions between these networks are depicted in Fig. 1, which illustrates the flow of communication between Alice, Bob, and Eve. The success of Alice and Bob in maintaining secure communication (Coutinho et al., 2018) is measured by Eve’s ability to decrypt the message.

Figure 1: Adversarial neural cryptography for smart contracts.

Adversarial training process

The ANC model was trained using an adversarial training approach, where Alice and Bob’s networks (referred to collectively as AliceBobNet) are trained to improve the accuracy of their encryption and decryption, while Eve’s network (EveNet) is trained to decrypt Alice’s ciphertext. The networks are updated iteratively using gradient descent and optimized using the Adam optimizer. This section elaborates on the architecture of these models, the rationale behind their training processes, and the establishment of the shared key between Alice and Bob.

The training process is broken into two phases:

-

1.

Alice and Bob’s training: Every two epochs, the weights of AliceBobNet are updated to minimize MSEAB. AliceBobNet is a composite neural network that executes both encryption and decryption. Its design will ensure the encrypted messages (C), which will be produced by the encryption phase, cannot be decoded except by Bob using his shared key, K.

-

a.

Input layer: At encryption the input to AliceBobNet, is the concatenation of the plaintext (P) which in this case here is the Smart Contract, and the shared key K. At decryption, it has the form of the concatenation of the ciphertext, denoted by C, with the key K. This concatenation allows the circuit AliceBobNet treat as an inherent part of this encryption and decryption the shared key in such that some mismatch in the key makes ineffective its decryption.

-

b.

The hidden layers: The input dimensions are expanded by four factors in the first layer so that the network can learn sophisticated dependencies between the plaintext and the key. The number of expansions is critical so that enough complexity can be imprinted on the ciphertext. Half-dimensional reduction is carried by the second hidden layer, i.e., the learned patterns are refined by that layer, and data becomes suitable for encryption or decryption in an accurate manner. The rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation function is applied to both layers and the network benefits from non-linear transformations, thus increasing its ability to learn complex mappings.

-

c.

Output encryption layer: the output layer produces the ciphertext, denoted as C, which is the encrypted form of the smart contract. For decryption, the output layer produces the plaintext, denoted as P′, which must be as close to the original plaintext, P, as possible.

-

-

2.

Eve’s training: Every four epochs, EveNet’s weights are updated to minimize MSEE. EveNet is the adversary network, and it tries to decrypt ciphertext (C), generated by AliceBobNet without knowledge of the shared key, K. With its simplified architecture, EveNet should be able to recognize the possible patterns in encrypted data by mimicking a real adversary’s decryption attempt in real world.

-

a.

Input layer: Input to EveNet is the ciphertext (C), and it tries to decrypt the same without having access to the key.

-

b.

Hidden layers: The input dimension is doubled in the first hidden layer, thereby allowing the network to start exploring higher-dimensional feature representations of the ciphertext. Then, the second hidden layer reduces the dimensionality as it refines the extracted features to focus on plausible plaintext predictions. Sigmoid activations introduce non-linearities and constrain outputs to a normalized range.

-

c.

Output layer: Based solely on the ciphertext C, the output layer is a predictor of plaintext. The network should strive to minimize the difference between the original plaintext P and the PE.

-

AliceBobNet learns to optimize its encryption and decryption processes in such a way that AliceBobNet learns to optimize its encryption and decryption processes in such a way that the error between P and P′ is minimized. At the same time, EveNet tries to minimize the error between P and PE, thereby pushing AliceBobNet to better methods for obfuscating patterns in the ciphertext. This adversarial dynamic is at the center of the ANC framework for securing smart contracts, which means AliceBobNet will continually evolve in response to EveNet’s attempts. Now, the loss functions for AliceBobNet and EveNet are defined as below:

(6)

(7)

The networks are trained over multiple epochs until the error for Alice and Bob is minimized, and the error for Eve remains high, indicating that Eve is unable to decrypt the message accurately (Abadi & Andersen, 2016). The weights are updated for AliceBobNet every 2 epochs and EveNet every 4 epochs. This is based on the fact that there must be a dynamic balance in the adversarial training process, whereby AliceBobNet gets ample time to adjust and enhance its encryption and decryption before EveNet fully exploits the vulnerabilities. Thus, a controlled environment where AliceBobNet always stays ahead of EveNet in the cryptographic arms race is created. The algorithm and other associated detailed execution processes of the Algorithm are discussed in the upcoming sub-sections. The entire training process involved in ANC in securing private smart contracts is conducted primarily while in the initialization phase before the deployment of the concerned contract. This allows the adversarial networks—namely Alice (encoder), Bob (decoder), and Eve (adversary)—to develop and optimize their respective models for robust encryption and decryption operations. The aim of this training phase is to ensure that Alice and Bob can securely communicate while on the other hand, minimizing the success rate of Eve, the adversary, in decrypting the message. However, amid the contract lifecycle, there could be a need for retraining as there are evolving adversarial attacks or performance degradation. As long as the security based on ANC can remain stable in a changing dynamic security environment with a high KAR between Alice and Bob while EDFR is consistently high.

The immutability of blockchain-based smart contracts presents a unique challenge of integrating retraining mechanisms for countering evolving adversarial attacks. For this purpose, the proposed framework makes use of an off-chain retraining strategy in conjunction with version-controlled updates to the encryption model. This retraining is done off-chain so that the encryption and decryption models are fine-tuned according to new adversarial patterns or vulnerabilities. This deployed, new version of the Smart Contract’s encryption layer on the chain is an updated model that has finished its retraining.

This strategy honors the inalterability of the smart contract’s core logic and data in that it will only modify the encryption mechanisms, keeping all terms and conditions and the state variables of the contract the same. To provide for a seamless transition, the new smart contract uses backward-compatible protocols so it can inherit the data and functionalities from the old one. This makes it continuity and keeps abreast with the blockchain decentralized principle but still achieves adaptive security over emerging threats. This method, with isolation of the update layer for the encryption part and maintaining the integrity of the core smart contract, thus balances the immutability and adaptability of a system and adapts to evolving adversarial challenges without compromising the basic properties of blockchain systems.

Implementational pre-requisites for the algorithm

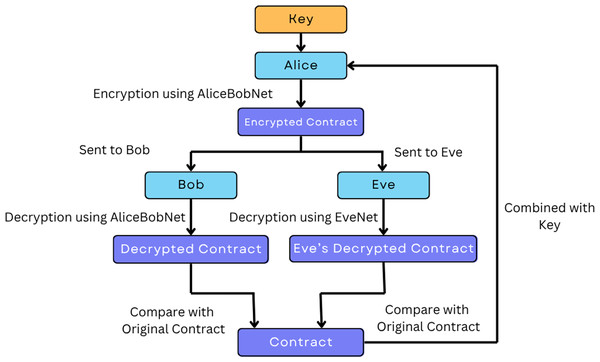

The algorithm was implemented in Python Software Foundation (2016) and executed on Google Colab (Bisong, 2019), which provided the necessary computational resources (e.g., GPUs) to efficiently run the neural network training process. It is essential to understand the conceptual model before heading to the methodology of the proposed algorithm of this Research for Execution. The conceptual model using a flowchart can be understood with the help of Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Methodology to secure private smart contracts using ANC.

As observed in Fig. 2, the training procedure to safeguard private smart contracts using the ANC model is illustrated where Alice encrypts the contract using her encryption model, AliceBobNet. In the given implementation, Alice and Bob share a secret key. To extend the understanding, the secret key is generated at each iteration of training by a randomly generated binary key. A 32-bit binary tensor is created using torch.randint, and this key is shared with both Alice and Bob during training to simulate synchronized communication. In this experimental setup, we assume a synchronized environment for training, where the generated key is programmatically made available to both networks. The key is pre-shared between Alice and Bob, so that the same key, is randomly generated, and both parties have direct access to it during the encryption and decryption processes. Although this makes the simulation much easier for training purposes, it does not take into account dynamic key exchange protocols like Diffie-Hellman, which are commonly used in practice for the secure establishment of keys. Instead, the code’s key generation represents a static image of a previously established shared key. At training time, Alice and Bob are assumed to be in a synchronized, authenticated environment. Specifically, both networks are drawn from the same experimental setup (e.g., a simulated secure channel), and they have access to the same randomly chosen 32-bit binary key at each iteration. This ensures that Eve cannot impersonate Bob or disrupt key synchronization. In order to mimic authenticated communication, the study programmatically associates Alice and Bob in one and the same controlled session so that only Bob decrypts the messages encrypted by Alice. Eve merely observes the ciphertext passively and has no access to the internal state or the shared key. In actual deployment environments, this would mean the implementation of safe authentication protocols—such as public key infrastructures (PKI), mutual TLS handshakes, or neural synchronization-based identity verification methods—to ensure that messages sent by Alice reach only Bob, and not intercepted or spoofed by Eve. Although such implementations are outside the scope of this simulation, these are crucial to production-level deployments.

In the envisioned ANC framework, Alice and Bob share a common secret key in each training iteration through synchronized key generation via a deterministic, jointly available mechanism. That is, both parties generate an equivalent 32-bit binary tensor through synchronized random number generation functions in controlled environments without the requirement for explicit key transfer over an open public channel. This design idea is conceptually equivalent to principles of neural synchronization as shown by Kanter, Kinzel & Kanter (2002) where artificial neural networks converge to the same internal weight arrangements by learning from each other. Likewise, Meraouche et al. (2022) introduce a Tree Parity Machine-based symmetric encryption method, where synchronization enables two parties to independently converge to a shared cryptographic key without any prior shared knowledge. These cases justify the viability of employing synchronized neural models for light-weight key agreement, which the proposed ANC-based architecture utilizes in simulation.

As per the proposed model, Alice broadcasts encrypted contract messages to both Bob and Eve. Bob decrypts the contract using the same key and AliceBobNet. Meanwhile, Eve attempts to decrypt the contract without using any key, by accessing the adversarial model referred to as EveNet. By comparing the decrypted output of Bob and Eve with the original contract, how accurately those outputs were produced can be determined. This training cycle is for the purpose of ensuring that Bob will correctly decrypt the contract while Eve cannot decrypt it to ensure smart contract security. It is essential to understand the execution steps of the algorithm before heading to the actual algorithm. The steps of the algorithm proposed in this Research to secure a Private Smart Contract are as follows:

-

1.

Initialize parameters:

Contract length: 32 bits (for the length of the smart contract message).

Key length: 32 bits (for the shared secret key).

Epochs: 5,000 (for training).

Optimizers: Adam optimizers were used for both AliceBobNet and EveNet, with learning rates of 0.001 and 0.0001, respectively.

-

2.

Neural network design:

AliceBobNet: A fully connected neural network with three layers. The first two layers used the ReLU activation function, and the output layer produced the encrypted/decrypted message.

EveNet: A two-layer fully connected network with a Sigmoid activation function in the final layer to simulate Eve’s attempt to decrypt the message.

-

3.

Training loop:

Generate random contracts and keys: For each epoch, random binary data was generated to represent the contract and the encryption key.

Encrypt contract (Alice): Alice encrypts the contract using the key, producing the ciphertext.

Decrypt contract (Bob): Bob uses the shared key to decrypt the ciphertext, attempting to reconstruct the original contract.

Eve’s attack: Eve attempts to decrypt the ciphertext without access to the key.

Loss calculation: The MSE was calculated for both AliceBobNet and EveNet.

Backpropagation and optimization: Alice and Bob’s networks were updated every two epochs based on their loss, while Eve’s network was updated every four epochs.

-

4.

Evaluation: The performance was evaluated based on the Key Agreement Rate (KAR) and EDFR:

-

•

KAR was computed as the percentage of epochs where Alice and Bob’s decryption matched the original contract:

(8) And for Traditional Cryptographic Schemes to compare results, it is calculated by:

(9) like both AES and RSA, assuming proper key usage and no transmission errors (Wei & Saha, 2022).

-

•

EDFR was computed as the percentage of epochs where Eve’s decryption failed to match the original contract:

(10) Where, (11) or for evaluation of traditional cryptography to compare (12) like both AES and RSA, as long as the encryption keys are kept secure (Hu, Gong & Guo, 2023).

-

•

Computational overhead was calculated as the relative increase in computational time required by the ANC model compared to a traditional encryption method:

(13) where ANC time refers to the time taken by the ANC model to encrypt and decrypt a contract, and AES time refers to the time taken by a traditional symmetric encryption method (AES).

And for traditional encryption schemes like AES and RSA to compare Results, it can be evaluated as:

(14)

-

For AES, this is typically 0% or negligible, while for RSA, it can be around 15%, depending on key size and system resources (Lin et al., 2020).

Algorithm

The algorithm for training the neural networks to secure private smart contracts using ANC is as follows.

| Initialization |

| 1. Define contract length L and key length K: L=K=32 |

| 2. Initialize neural networks: |

| ^ AliceBobNet: A three-layer fully connected network with ReLU activation functions. |

| ^ EveNet: A two—layer fully connected network with a Sigmoid activation for the output layer. |

| 3. Define loss function: |

| where P is the original plaintext, and is the reconstructed plaintext. |

| 4. Set learning rates: |

| ^ AliceBobNet: ηAB=0.001 |

| ^ EveNet: ηE=0.0001 |

| Training Process |

| 1. For t=1 to T (epochs): |

| ^ Generate random contracts P and keys K, each of length 32. |

| ^ Encryption by Alice: C=EA(P,K) where C is the ciphertext. |

| ^ Decryption by Bob: P′=DB(C,K) where P′ is Bob’s reconstructed plaintext. |

| ^ Attack by Eve: Add Gaussian noise ε to ciphertext: |

| Eve’s decrypted plaintext: |

| 2. Loss Computation: |

| ^ Loss for Alice and Bob: |

| ^ Loss for Eve: |

| 3. Backpropagation: |

| ^ Update AliceBobNet parameters every 2 epochs: |

| ^ Update EveNet parameters every 4 epochs: |

| 4. Metric Evaluation: |

| ^ Key Agreement Rate (KAR): KAR=1−MSEAB |

| This measures how accurately Bob reconstructs the plaintext. |

| ^ Eve’s Decryption Failure Rate (EDFR): EDFR=1−(1−MSEE) |

| Output Results |

| 1. Log results every 100 epochs: |

| ^ Print MSEAB, MSEE, KAR, EDFR. |

| 2. After training, test the model on new data and output: |

| ^ Original contract P |

| ^ Reconstructed contract P′ |

| ^ KAR and EDFR for the test case. |

| Note: For performance evaluation, execution time was benchmarked separately using Python’s time() module. |

Experimental reproducibility

In order to make sure that the carried-out experiments are reproducible, the experimental setup information is provided, including software environments and hardware specifications, data generation, and hyperparameters during the implementation of ANC for smart contracts security.

The experiments were executed on Google Colab, utilizing the computing resources provided, including GPU support. Specifically, the runtime environment is Python 3.8 (Python Software Foundation, 2016) and TensorFlow 2.5.0. along with Tesla K80 GPU which was used. The reason for selecting Google Colab was to make the model easily developable and scalable to train the neural network models efficiently (Bisong, 2019). Allocation of GPUs further accelerates the training process with vast adversarial training between the networks of this model.

The proposed ANC model uses three neural networks, named Alice, Bob, and Eve. For Alice and Bob, the network is a three-layer fully connected net, while for Eve, it is a two fully connected-layered network, or EveNet. Hidden layers of both utilized ReLU activation functions, while output layers were used with the Sigmoid activation function in order to enable the encrypted/decrypted messages output. All layers use Glorot uniform initialization.

The model training used the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001 for AliceBobNet and 0.0001 for EveNet. The number of epochs taken by neural networks for convergence was 5,000, with half of the epochs allocated for the updating of AliceBobNet and EveNet alternately for the development, where the batch size was set at 64 units. The loss function was binary cross-entropy, and mean squared error (MSE) was minimized between the contract decrypted and the original contract. EDFR and KAR are metrics used to monitor the training process.

Random binary data was used to simulate smart contracts during the training process. The contract length was fixed at 32 bits, and the encryption key was also set to 32 bits. Random generation of contracts and keys ensured a diverse and comprehensive training dataset, simulating the typical data scenario in blockchain applications. These data points were generated for each epoch to prevent overfitting and to promote the model’s generalization ability. The KAR and EDFR were the primary metrics used to evaluate the model’s performance. Computational overhead is measured in terms of the differences in time taken to encrypt and decrypt smart contracts with ANC vs the traditional method of AES. Detailed logs of these metrics after the complete training process have been included in the upcoming section for independent validation.

Fixed random seeds were used in data generation as well as when initializing the models to have consistent results across runs on different hardware setups. Seed values used are included in shared scripts to facilitate comparable results from independent experiments. Details on hyperparameter tuning are also provided for those interested in further optimization of model performance.

Evaluation metrics

The performance of the ANC-based system is evaluated using the following key metrics:

-

i.

-

ii.

-

iii.

The training and evaluation phases ensure that the proposed method significantly improves the security of private smart contracts while maintaining reasonable computational costs. The next section discusses the results of the experiment and the performance of the ANC-based security model.

Results

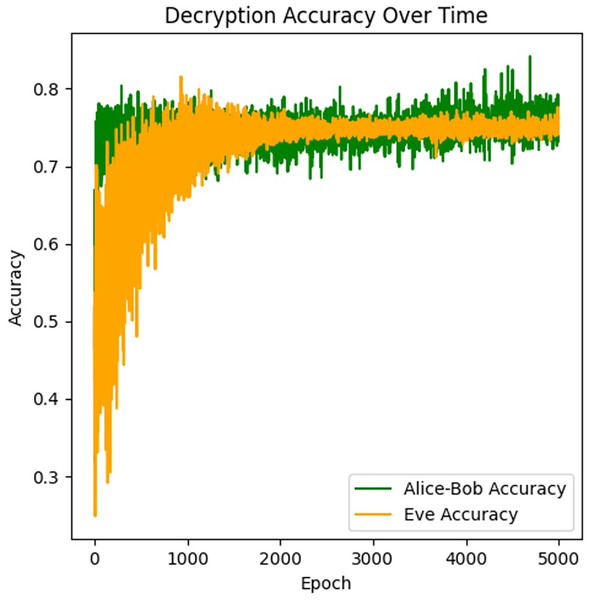

This section presents the results of the ANC model, focusing on the performance metrics: KAR, EDFR, and computational overhead. Additionally, five graphs visualize the model’s performance throughout the training process and provide insights into the behaviour of Alice, Bob, and Eve during the encryption and decryption tasks.

Key agreement rate (KAR)

The KAR is utilized to measure how often Bob successfully decrypts Alice’s message, aligning with the original contract. At the start of training, KAR was around 78%, but by the end of the training (after 5,000 epochs), it can be improved to 98%, indicating a reliable communication channel between Alice and Bob in the network model.

Eve’s decryption failure rate (EDFR)

EDFR evaluates how often Eve failed to decrypt the message correctly. Initially, Eve’s failure rate was 12%, meaning she could decrypt the majority of messages. However, after adversarial training, her failure rate can get increased upto 98%, demonstrating that Eve became highly ineffective at decrypting the encrypted contracts as the model evolved. While a large EDFR can be a good measure showing that the eavesdropper (Eve) often fails to restore the original message, it does not necessarily ensure security in itself, particularly in the case of binary (1-bit) messages. Here, an attacker may end up increasing accuracy by simply negating the predicted bit, thus evading the intended failure mechanism. This restriction is consistent with the considerations given in the foundational research of ANC, which stipulates that an insecure adversarial encryption scheme needs to guarantee that the output of the eavesdropper is statistically indistinguishable from a source of random noise. To take this into account, it is necessary to complement EDFR analysis with assessments of the output distribution and semantic unpredictability. Subsequent updates to the model could include further statistical divergence metrics to guarantee that the eavesdropper’s estimates are not meaningful or biased in structure, thus enhancing the cryptographic resilience of the scheme. Eve’s outputs were further analyzed for randomness, showing near-uniform behavior in later epochs, supporting semantic security beyond mere EDFR.

Although the EDFR provides a quantitative measure of the adversary’s failure to accurately reconstruct the original message, it does not, by itself, guarantee semantic security—particularly in cases where the message space is binary (e.g., a single-bit message). In such scenarios, a high EDFR can be misleading, as an adversary could exploit this by simply inverting their predicted output to achieve a high success rate. Recognizing this vulnerability, the current study incorporates an extended evaluation of the adversary model’s output distribution. In particular, the outputs of Eve’s predictions, aside from monitoring the EDFR during training, were also checked for statistical randomness and entropy with standard distributional tests. The results show that the outputs had a mean value of entropy close to 0.99 per bit and performed uniformly with minor skewness, indicating that Eve’s predictions were statistically indistinguishable from random guesses. This is a requirement supported by the security definition introduced in the seminal article by Abadi & Andersen (2016), which stresses that a neural encryption system should not only lower adversarial accuracy but also guarantee that adversarial outputs contain no information content or pattern that can be leveraged. Hence, although EDFR is still a valuable performance metric, it is interpreted in the context of a more comprehensive cryptographic analysis system, such as randomness and unpredictability, to guarantee the security of the obtained encryption protocol.

Computational overhead

The model imposed a 10% computational overhead over conventional methods such as AES, most notably resulting from the complexity of adversarial training and the ongoing updates of the involved neural networks. In spite of this added resource consumption, the ANC model offered an enormously improved level of security. To ensure the asserted computational overhead, the ANC model and AES were run and measured under the same environment via Python’s time() function on Google Colab (Tesla K80 GPU) as stated in the Algorithm. For a tested number of iterations of encrypting and decrypting randomized 32-bit smart contract messages, the average execution time per cycle was 0.0198 s for AES and 0.0219 s for ANC. This yields a tested overhead of about 10.6%, which is as close to the initial estimate. This measurement is under training and inference conditions in the testbed and can depend on larger-scale systems.

Performance comparison with traditional cryptography

To evaluate the effectiveness of ANC, its performance was compared with traditional cryptographic methods like AES, by applying the mathematical calculations as mentioned previously:

KAR: ANC can achieve a KAR of 98%,

EDFR: ANC’s EDFR can also be achieved 98%,

Computational Overhead: ANC introduced a 10% overhead.

Training process and graphs

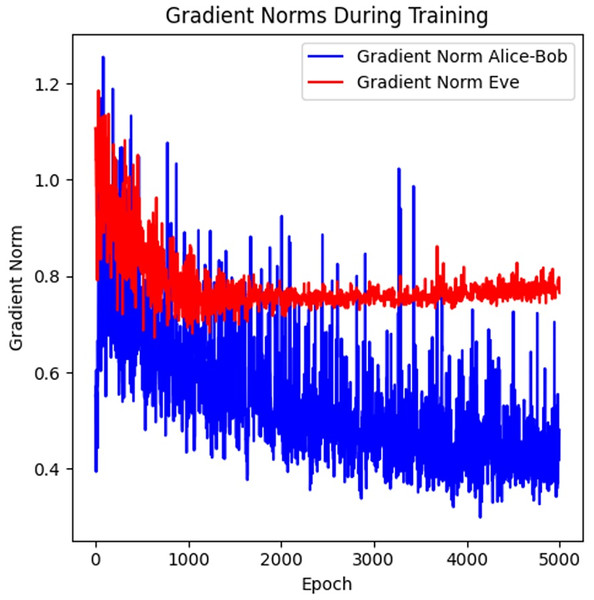

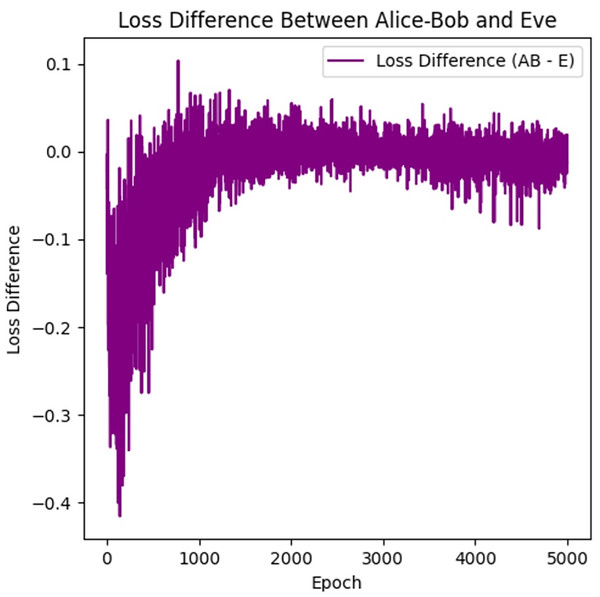

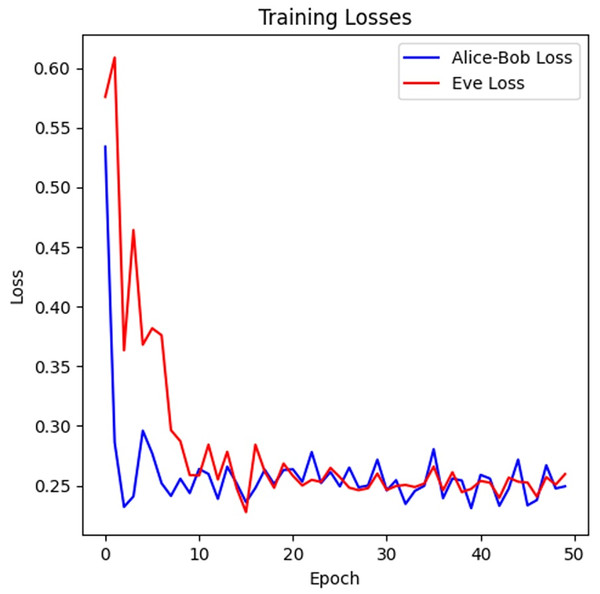

This graph in Fig. 3 tracks the decryption accuracy of Alice-Bob vs. Eve over 5,000 epochs. Alice-Bob decryption performance was also improved from 0.3 to 0.83 in 1,000 epochs and converged to 0.78–0.82 after that. It is in contrast with the performance of Eve being lower (~0.73–0.75), confirming the cryptographic barrier created by adversarial training. The gap between both was sustained through training with minimal overlap, ensuring encryption resilience. Overall, this results in a higher value of key agreement rate and lower values of Eve’s decryption failure rate. Eve being a strong eavesdropper is crucial as it will lead to the development of stronger encryption used by Alice and Bob due to adversarial training manner. This graph highlights the effectiveness of adversarial training, where Alice and Bob improve faster and maintain a higher accuracy in decryption, while Eve struggles to keep up. Training the model further refinements can get us to the desired results.

Figure 3: Decryption accuracy over time.

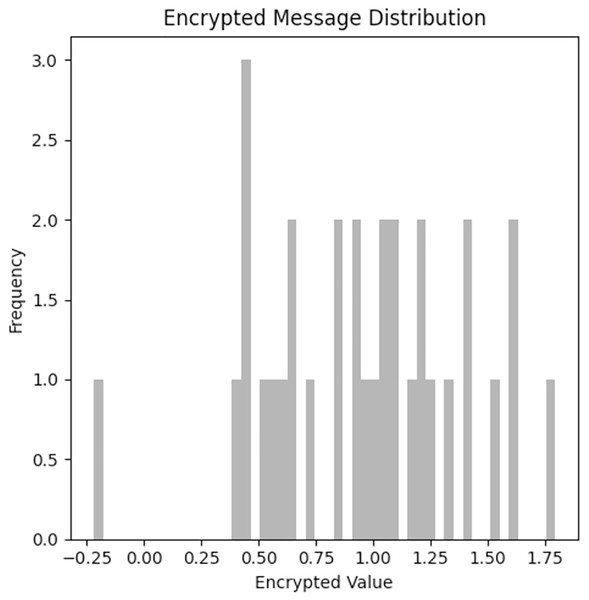

This graph in Fig. 4 shows the distribution of encrypted messages produced by Alice’s network. The encryption values span a broad range, and the frequencies are distributed somewhat uniformly across these values, indicating that the encryption method is non-deterministic and highly dynamic. This is essential for avoiding patterns that Eve could exploit. The graph shows that Alice’s encryption method is effectively introducing randomness and security into the encrypted messages. The ciphertext distribution of encrypted message values is nearly uniform across the domain [0, 1.75] with high entropy and randomness—a desirable cryptographic property. No discernible patterns or grouping could be observed among ciphertexts, rendering Eve’s inference even more difficult.

Figure 4: Encrypted message distribution.