Adaptive graph attention-based federated learning for IoT intrusion detection: mitigating poisoning attacks

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Paulo Jorge Coelho

- Subject Areas

- Artificial Intelligence, Computer Networks and Communications, Internet of Things, Machine Learning, Deep Learning

- Keywords

- Federated learning, IoT, Intrusion detection, Poisoning attacks

- Copyright

- © 2025 Sanjalawe et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits using, remixing, and building upon the work non-commercially, as long as it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2025. Adaptive graph attention-based federated learning for IoT intrusion detection: mitigating poisoning attacks. PeerJ Computer Science 11:e3281 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3281

Abstract

The widespread adoption of Internet of Things (IoT) networks introduces critical security challenges, particularly due to poisoning attacks targeting federated learning (FL)-based intrusion detection systems (IDSs). Traditional FL methods, such as FedAvg, are vulnerable to adversarial updates, which compromise model integrity and reliability. To address these limitations, this article proposes an Adaptive Graph Attention-Based Federated Learning (AGAT-FL) framework designed to enhance the resilience of IoT-based IDSs. AGAT-FL combines dynamic trust-aware aggregation using graph attention networks (GAT), a hybrid convolutional neural network-gated recurrent unit (CNN-GRU) deep learning model for spatial-temporal anomaly detection, and Mahalanobis distance-based filtering to identify and suppress adversarial contributions. Trust scores are adaptively assigned to participating clients based on historical performance and behavioral indicators, allowing AGAT-FL to downweight suspicious updates while preserving data privacy. Experimental evaluations on two benchmark IoT security datasets, N-BaIoT and CIC-ToN-IoT, demonstrate that AGAT-FL consistently outperforms state-of-the-art FL methods. It achieves up to 94.01% accuracy, 93.50% precision, 94.00% recall, and 93.75% F1-score on N-BaIoT, and 91.02% accuracy, 91.00% precision, 91.30% recall, and 91.15% F1-score on CIC-ToN-IoT. Additionally, the use of explainable AI techniques such as SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) and Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME) enhances transparency by identifying key features contributing to anomaly classification. These results underscore AGAT-FL as a robust, interpretable, and scalable solution for securing FL-based IoT networks against sophisticated poisoning attacks.

Introduction

The Internet of Things (IoT) revolutionises how devices interact by enabling seamless communication between interconnected smart objects (Zhang & Feng, 2024; Alsaaidah et al., 2024). These IoT devices are widely deployed in various sectors, including healthcare (Clemente-Lopez, de Jesus Rangel-Magdaleno & Muñoz-Pacheco, 2024), smart homes (Netinant et al., 2024), industrial automation (Mu & Antwi-Afari, 2024), and transportation (Wang et al., 2024c). However, the increasing adoption of IoT comes with significant security challenges due to its distributed nature, limited computational resources, and heterogeneous network architectures. Unlike traditional computing environments, IoT devices often operate in low-power, resource-constrained conditions, making them vulnerable to various cyber threats, including denial-of-service (DoS) attacks, botnets, eavesdropping, and malware injections (Cecílio & Souto, 2024). One of the primary security concerns in IoT networks is the lack of centralized control and enforcement mechanisms (Isyaku et al., 2024; Khan et al., 2022), which exposes them to attacks that can compromise data integrity, confidentiality, and availability. Furthermore, IoT ecosystems often include unpatched and outdated firmware, increasing the risk of zero-day vulnerability exploitation. Since many IoT devices rely on wireless communication protocols such as Wireless Fidelity (Wi-Fi), Zigbee, Bluetooth, and LoRa, adversaries can execute Man-in-the-Middle (MITM) attacks, replay attacks, and signal jamming to disrupt communications (Perwej et al., 2022).

Another critical challenge in IoT security is the scalability and heterogeneity of connected devices (Noaman et al., 2022; Rana, Singh & Singh, 2021). Maintaining a unified and robust security architecture is complex, with billions of devices operating in dynamic environments. Traditional security mechanisms such as firewalls, antivirus software, and encryption schemes are often infeasible due to computational constraints and real-time operational requirements in IoT systems. Consequently, security approaches that leverage lightweight anomaly detection mechanisms and distributed threat intelligence have gained significant attention (Abououf et al., 2022).

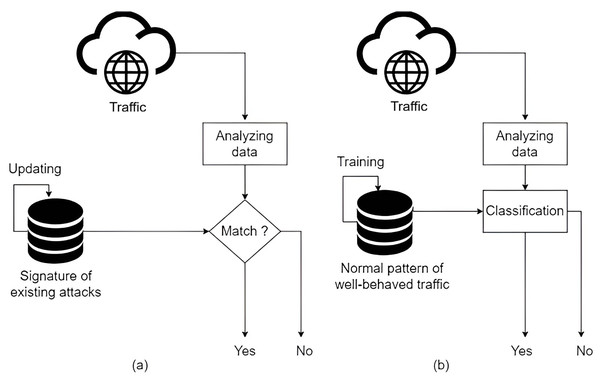

In this context, intrusion detection systems (IDSs) emerge as a crucial defence mechanism against cyber threats in IoT networks (Heidari & Jabraeil Jamali, 2023; Saied, Guirguis & Madbouly, 2024; Almomani et al., 2025). These systems continuously monitor network traffic, analyze device behaviours, and detect malicious activities that could compromise the security of IoT infrastructures. IDS plays a pivotal role in enhancing the security and resilience of IoT networks. Unlike traditional security solutions, IDS focuses on anomaly detection and real-time threat identification without disrupting device functionality (Saied, Guirguis & Madbouly, 2024; Mukhaini et al., 2024). IDS can be categorized into, as illustrated in Fig. 1, signature-based detection and anomaly-based detection (Nawaal et al., 2024; Mutambik, 2024; Zahary, Al-shaibany & Sikora, 2024):

-

Signature-based IDS: Detects known threats by comparing network traffic with predefined attack signatures. While effective against previously encountered attacks, it struggles to detect zero-day attacks and evolving adversarial techniques.

Anomaly-based IDS: Utilizes machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) models to identify deviations from normal network behaviour. This approach is more effective in detecting novel and sophisticated attacks.

Figure 1: (A) Signature-based. (B) Anomaly-based.

Background and motivation

Given the highly dynamic and heterogeneous nature of IoT environments, distributed IDSs have emerged as a preferred paradigm for enabling real-time, scalable, and autonomous threat detection. These systems, however, face several critical challenges, including privacy preservation, limited computational resources, and exposure to sophisticated adversarial attacks.

Among the most promising advancements in distributed IDS is federated learning (FL), which enables multiple IoT devices to collaboratively train a shared global model without transferring raw data (Yazdinejad et al., 2024b; Siddique et al., 2024). This decentralized architecture supports privacy-preserving learning, allowing each client to retain sensitive data locally while contributing to a global objective. Consequently, FL significantly improves anomaly detection by aggregating insights from geographically and contextually diverse sources, all while maintaining user confidentiality (Wang et al., 2024b).

However, the decentralized nature of FL also introduces new attack surfaces, most notably, poisoning attacks (Ni et al., 2024). In this context, a poisoning attack refers to the deliberate manipulation of the learning process by compromised clients that contribute adversarial updates (Yazdinejad et al., 2024a). These attacks can take the form of data poisoning, where malicious clients inject corrupted samples into their local training data, or model poisoning, where clients deliberately craft and submit deceptive gradients or parameter updates to degrade or subvert the global model. Such adversarial behaviors can significantly compromise the integrity, accuracy, and reliability of FL-based IDS, rendering them ineffective in detecting evolving threats.

FL enhances privacy by localizing training data while aggregating model updates on a central server (Yazdinejad et al., 2024b; Siddique et al., 2024). However, its decentralized nature introduces new attack vectors, particularly poisoning attacks (Ni et al., 2024; Nowroozi et al., 2025), which can significantly degrade IDS performance in IoT networks. Poisoning attacks in FL can be categorized into:

Data poisoning attacks: Attackers inject malicious data into the local training process, leading to biased or incorrect model updates (Wang, Wang & Ban, 2024). In IoT, compromised devices may generate falsified network logs, misleading IDS models into learning incorrect patterns.

Model poisoning attacks: Instead of tampering with the training data, adversaries directly manipulate model updates before sending them to the global server (Ni et al., 2024). This allows attackers to introduce backdoors or degrade model performance selectively.

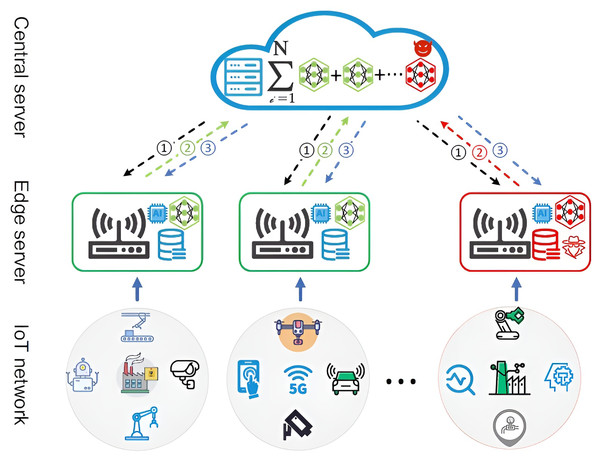

FL’s distributed and asynchronous nature makes it challenging to detect and mitigate poisoning attacks effectively. Traditional anomaly detection techniques often fail because adversaries can subtly alter gradients without triggering defence mechanisms. Moreover, compromised IoT devices participating in FL can execute Sybil attacks (Hassan et al., 2024), where multiple fake nodes inject adversarial updates to corrupt the global model. For instance, Fig. 2 illustrates the architecture of an FL framework for IoT intrusion detection across distributed networks. At the IoT network layer, various devices (e.g., robots, drones, 5G nodes, and smart factories) collect data and communicate with edge servers, which act as intermediaries between the devices and the central server (Packianathan et al., 2025). The edge servers locally train artificial intelligence (AI) models using data from IoT devices and forward model updates (not raw data) to the central server, ensuring privacy preservation. The central server aggregates these updates (represented as a summation of model contributions from multiple nodes) to create a global model. However, the figure highlights potential security challenges, such as poisoning attacks, as indicated by malicious updates (red paths). These compromised contributions degrade the overall model’s integrity and underscore the need for robust defence mechanisms, such as the proposed Adaptive Graph Attention-based FL approach.

Figure 2: Poisoning attack based on FL (Yang et al., 2023).

Despite the growing body of research on FL for IoT security, existing approaches often fall short in addressing the increasing sophistication of poisoning attacks, particularly in highly dynamic and heterogeneous network environments. Most current frameworks rely on uniform aggregation strategies, such as FedAvg, which do not distinguish between reliable and potentially adversarial nodes. This lack of contextual trust modeling significantly limits their resilience against malicious updates that degrade global model performance. Furthermore, the integration of adaptive trust mechanisms and graph-based learning remains underexplored in the context of IDSs. Therefore, this study addresses a critical gap by proposing a novel trust-aware FL framework that incorporates graph attention networks (GATs) and adaptive aggregation strategies to enhance robustness against poisoning attacks while maintaining the privacy-preserving advantages of FL.

Aim and objectives

The core aim of this article is to develop a robust and adaptive FL approach capable of detecting poisoning attacks in IoT. The proposed approach, AGAT-FL, adapts GATs, trust-aware aggregation, and hybrid deep learning models to enhance the resilience, scalability, and interpretability of IDSs in heterogeneous IoT environments.

To achieve this aim, the following main objectives have been identified. These objectives are intended to guide the development and evaluation of the proposed AGAT-FL framework, ensuring that it overcomes the existing research challenges posed by poisoning attacks while ensuring efficiency and accuracy in IoT environments:

To develop a graph-based client representation that models IoT devices as interconnected nodes, enabling the use of GATs for adaptive trust scoring.

To implement a dynamic trust-aware aggregation mechanism that downweights or rejects adversarial model updates during the federated learning process.

To integrate a hybrid Convolutional Neural and Network Gated Recurrent Unit (CNN-GRU) model for effective spatial-temporal anomaly detection from network traffic data, enhancing detection accuracy and robustness.

To incorporate statistical anomaly detection using Mahalanobis distance for the identification and suppression of poisoned updates based on deviation from normative behavior.

To improve model interpretability and decision transparency through explainable AI (XAI) techniques such as SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) and Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME), offering insights into anomalous contributions.

Article organization

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. ‘Related Works’ reviews existing literature on federated learning, intrusion detection in IoT, and poisoning mitigation techniques, highlighting key limitations that motivate our work. In ‘Problem Definition and Threat Model’, we define the formal problem setting and outline the threat model, including various types of poisoning attacks relevant to FL-based IDSs. ‘Proposed Methodology’ presents the proposed AGAT-FL framework in detail, covering trust-aware graph construction, hybrid deep learning architecture, contrastive learning integration, and poisoning mitigation strategies. ‘Experiments and results’ describes the experimental setup, datasets, evaluation metrics, and comparative performance results against baseline and state-of-the-art approaches. In ‘Discussion and Limitations’, we discuss the key contributions of AGAT-FL and their roles in achieving superior results, along with a critical reflection on the limitations of the current approach. Finally, ‘Conclusion and Future Works’ concludes the article and outlines directions for future research based on the identified challenges and opportunities.

Related works

In recent years, the adoption of FL for securing IoT networks has drawn substantial research interest, especially in the context of IDS. Traditional FL approaches, such as FedAvg, offer privacy-preserving model training but are increasingly susceptible to adversarial manipulations, particularly poisoning attacks. As a result, the research community has proposed various enhancements, including trust-aware aggregation, knowledge distillation, blockchain integration, and adversarial robustness techniques. This section presents a comprehensive review of the most prominent FL-based IDS frameworks, with a focus on their strategies to mitigate poisoning attacks, their architectural innovations, and the specific challenges they address. The critical insights gained from these studies serve as a foundation for the development of the proposed AGAT-FL framework.

For instance, Quyen et al. (2025) introduce a semi-supervised FL system for IDS called FedKD-IDS. FedKD-IDS differs from traditional FL methods in that it employs a knowledge distillation-based voting mechanism in place of weighted parameter aggregation to improve resilience and accuracy. Furthermore, FedKD-IDS employs anti-poisoning methods to strengthen defenses against adversarial behaviors. The approach was rigorously tested under a range of scenarios, including non-IID data distributions and different degrees of malicious client participation, using the N-BaIoT dataset. An accuracy of 79% was recorded for FedKD-IDS in scenarios with 50% participants executing label-flipping attacks, drastically outpacing the state-of-the-art SSFL approach with 19.86% accuracy. The method also showed strong capability of filtering out more than 85% of malicious clients during aggregation, confirming its robustness against adversarial threats.

Similarly, Zhang et al. (2025) introduce AdaptFL, an adaptive federated learning approach that is particularly designed for heterogeneous devices. This approach incorporates a resource-aware neural architecture search technique that dynamically provides customized models for each client according to their current resource constraints in every training rotation. This adaptive modeling approach allows clients with limited resources to participate in the FL process. To manage and mitigate the issues posed by model heterogeneity, AdaptFL also adapts a staged knowledge distillation mechanism, which ensures efficient knowledge transfer and aggregation among the diverse local models and the heterogeneous global model. Experimental results prove that AdaptFL significantly outperforms existing model-level heterogeneous ablation methods. On the SVHN dataset, it achieves a 4% to 15% improvement in global test accuracy, and in heterogeneous data scenarios, the accuracy gains range from 5% to 14%. Additionally, AdaptFL demonstrates a reduction in communication overhead by more than 50% across multiple datasets. Notably, the framework also exhibits resilience to model poisoning attacks, further highlighting its robustness and practicality in decentralized and resource-constrained environments.

In the context of accountability and security within IoT systems, particularly in SM 3.0-integrated environments, Salim, Moustafa & Turnbull (2025) propose a Blockchain-enabled FL framework with Smart Contracts (BFL-SC). This framework introduces a transparent incentive mechanism to reward participants while combating free-riding attacks. A differential privacy-based perturbation (DPP) mechanism safeguards data against model inversion attacks, and a robust verification protocol addresses potential poisoning attacks. Evaluations on the SM 3.0 and Human Activity Recognition (HAR) datasets demonstrate high utility, with precision rates of 96.95% and 90.14%, respectively, while adhering to privacy and efficiency standards.

In the realm of FL-based recommender systems, Zhao et al. (2025) propose AFedDFM, an asynchronous FL model designed for privacy-preserving deep learning recommendations. AFedDFM addresses privacy concerns through pseudo-interaction padding and local differential privacy mechanisms, protecting user data while maintaining recommendation accuracy. The model also incorporates anti-poisoning algorithms to mitigate the impact of malicious clients. Extensive experiments on benchmark datasets reveal AFedDFM’s ability to improve recommendation quality, address the cold-start problem, and enhance privacy protections.

Other notable advancements include FedMADE by Sun et al. (2024), which introduces a dynamic aggregation method clustering devices based on traffic patterns and aggregating models by their contribution to overall performance. FedMADE demonstrates up to 71.07% improvement in minority attack classification accuracy and maintains robustness to poisoning attacks, incurring only a 4.7% latency overhead compared to FedAvg. Furthermore, Luong et al. (2024) propose Fed-LSAE, a robust FL aggregation method that leverages latent space representation and autoencoders to exclude malicious clients. Using Center Kernel Alignment to classify benign and adversarial contributions, Fed-LSAE achieves approximately 98% accuracy on the CIC-ToN-IoT and N-BaIoT datasets, highlighting its efficacy against advanced poisoning attacks.

In healthcare applications, Khan et al. (2024) propose the Healthcare Federated Ensemble Internet of Learning Cloud Doctor System (FDEIoL), designed for remote patient monitoring in smart healthcare systems. FDEIoL integrates federated ensemble learning with feature selection to filter malicious models and optimize prediction accuracy. The system achieved remarkable accuracy rates of 99.24% on the Chest X-ray dataset and 99.0% on the MRI brain tumor dataset, outperforming centralized models and ensuring data privacy and biomedical security.

These advancements reflect the diverse strategies employed to address the challenges of FL-based systems in IoT environments. From enhancing privacy protections and combating poisoning attacks to optimizing communication and ensuring robustness in heterogeneous settings, these solutions underscore FL’s potential in securing IoT networks. However, as concluded from Table 1, further research and innovation are required to overcome emerging challenges and expand the applicability of FL-based IDS and recommender systems in real-world scenarios.

| Study | Method | Challenges addressed | Dataset(s) | Key results | Shortcomings (Motivation for AGAT-FL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quyen et al. (2025) | FedKD-IDS (semi-supervised FL + KD) | Privacy, poisoning, non-IID data | N-BaIoT | 79% accuracy under 50% label-flipping; excluded 85%+ malicious clients | No dynamic trust scoring; static voting limits robustness in adversarial contexts |

| Zhang et al. (2025) | AdaptFL (resource-aware NAS) | Device heterogeneity, communication overhead, poisoning | SVHN | 4–15% accuracy gain; 50%+ communication reduction | No anomaly-based aggregation; lacks poisoning-specific mitigation during model updates |

| Salim, Moustafa & Turnbull (2025) | BFL-SC (blockchain + smart contracts) | Free-riding, poisoning, model inversion, accountability | SM 3.0, HAR | Precision: 96.95%, 90.14% | Blockchain incurs latency and overhead; not suited to low-power IoT devices |

| Zhao et al. (2025) | AFedDFM (async FL recommender) | Privacy, cold-start, poisoning attacks | Recommender datasets | Enhanced recommendation accuracy with privacy preservation | Tailored to recommender systems; lacks generalizability for IDS and real-time anomaly detection |

| Sun et al. (2024) | FedMADE (traffic-aware aggregation) | Minority attack detection, poisoning | Not specified | 71.07% improvement in minority detection; 4.7% latency overhead | Needs accurate traffic clustering; lacks adaptive trust and explainable filtering |

| Luong et al. (2024) | Fed-LSAE (latent space + autoencoder) | Poisoning resilience, malicious client exclusion | CIC-ToN-IoT, N-BaIoT | 98% accuracy; strong adversarial filtering | Latent filtering heuristic-based; no graph structure or contextual relationship modeling |

| Khan et al. (2024) | FDEIoL (ensemble FL + feature selection) | Privacy, biomedical model filtering, data security | Chest X-ray, MRI | 99.24%, 99.0% accuracy | Domain-specific to healthcare; lacks scalability and defense layering for IoT IDS |

Problem definition and threat model

As the IoT continues to proliferate across diverse domains, ranging from smart homes to critical infrastructure, the need for robust and scalable security mechanisms has never been more pressing. FL has emerged as a promising solution, enabling collaborative training of intrusion detection models across decentralized IoT devices without requiring raw data sharing. Despite its privacy-preserving advantages, FL introduces new attack surfaces, most notably, poisoning attacks, that threaten the integrity and reliability of learned models.

This section formally outlines the FL-based intrusion detection problem and elaborates on the adversarial threats considered in this article. We define the collaborative learning objective under FL, identify key vectors of attack, including data poisoning, model poisoning, and Sybil attacks, and describe the adversarial capabilities and goals. Through this threat modeling, we aim to characterize the security risks faced by FL systems deployed in heterogeneous and resource-constrained IoT environments, thereby motivating the need for trust-aware and resilient aggregation mechanisms.

Problem definition

FL enables multiple IoT devices to train an IDS model collaboratively without sharing raw data. The objective is to minimize the global loss function:

(1) where:

represents the global model parameters,

is the local loss function for device ,

is the weight assigned to device ,

N is the total number of participating IoT devices.

Poisoning attacks occur when adversarial devices inject malicious updates into the global model to degrade performance.

Threat model

FL-based IDS systems are vulnerable to two primary types of poisoning attacks:

Data poisoning attacks

Attackers manipulate the local dataset of device by injecting adversarial samples:

(2) where:

is the adversarially modified dataset,

consists of falsified intrusion data.

The attacker’s goal is to maximize model misclassification:

(3)

Model poisoning attacks

Instead of modifying training data, adversaries alter model updates before sending them to the global FL server:

(4)

An adversarial device modifies the update:

(5) where:

is an adversarial perturbation designed to degrade the model.

The standard FL model update using federated averaging (FedAvg) is:

(6)

Under an attack:

(7) where:

is the set of benign devices,

is the set of adversarial devices.

Sybil attack in FL

Adversaries introduce multiple fake IoT devices (Sybil nodes) to amplify poisoning effects:

(8)

This overwhelms the aggregation process and degrades model integrity.

Impact of poisoning attacks

Attackers aim to maximize the model degradation by optimizing adversarial updates:

(9) where:

represents the expectation over adversarial strategies.

This mathematical framework formalizes the poisoning attack problem in FL-based IDS and highlights the need for robust defence mechanisms. The proposed AGAT-FL approach leverages trust-aware aggregation to mitigate adversarial attacks and enhance security in IoT networks.

Proposed methodology

FL has gained significant attention in machine learning as it enables distributed model training without requiring raw data exchange. However, its decentralized nature introduces security vulnerabilities, particularly poisoning attacks, where adversaries manipulate data or model updates to degrade system performance. This article proposes an AGAT-FL approach for detecting poisoning attacks in FL systems using two datasets, including N-BaIoT (https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/mkashifn/nbaiot-dataset) and CIC-ToN-IoT (https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/dhoogla/cictoniot).

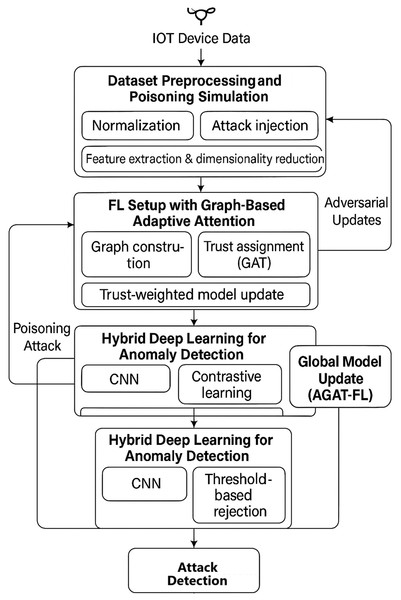

The proposed methodology, as summarized in Fig. 3, integrates graph-based trust mechanisms, adversarial robustness enhancement, and hybrid anomaly detection models to improve detection accuracy and system resilience. Key innovations include multi-modal feature fusion, adaptive defence aggregation, and meta-learning optimization.

Figure 3: Architecture of proposed methodology.

The proposed methodology is structured into four key stages, ensuring a systematic and robust approach to poisoning attack detection.

Stage 1: dataset preprocessing and poisoning simulation

This stage focuses on preparing the dataset for training and simulating adversarial poisoning attacks. It involves selecting relevant datasets, normalizing data for consistency, and applying preprocessing techniques to enhance model training. Additionally, various poisoning attack strategies, such as backdoor insertion, label flipping, and adversarial perturbations, are introduced to evaluate the robustness of the IDS. These steps are to assess comprehensively the proposed model’s ability to detect and mitigate poisoning attacks in FL environments.

-

1.

Dataset selection:

-

•

Utilize N-BaIoT, CIC-ToN-IoT datasets.

The N-BaIoT (Meidan et al., 2018) dataset is designed to detect anomalous behaviour in IoT devices. It consists of network traffic data captured from devices infected with Mirai and Bashlite botnets. The dataset includes benign and malicious traffic flows, with 115 extracted features related to network flow statistics. It provides a comprehensive benchmark for IoT security and intrusion detection.

The CIC-ToN-IoT (Moustafa, 2021) dataset is a large-scale dataset that captures real-world IoT, IT, and OT (operational technology) environments. It contains a combination of normal and malicious network traffic, including attacks such as DDoS, reconnaissance, backdoors, and injection attacks. The dataset comprises approximately 16.8 million network traffic flows, with 44 labelled network flow features, making it highly suitable for evaluating intrusion detection models.

-

•

Normalization: The datasets used in this article have different data types, requiring different normalization techniques for optimal performance. Table 2 presents the normalization methods used for each dataset:

Symbol definitions:

-

–

X—Original feature value

-

–

X′—Normalized feature value

-

–

—Mean of the dataset

-

–

—Standard deviation of the dataset

-

To adhere to the privacy-preserving principles of FL, all normalization operations in AGAT-FL are performed locally on each client device. Specifically, the mean ( ) and standard deviation ( ) required for Z-score normalization are computed independently using each client’s private dataset. This approach prevents the need to share raw data or global statistical summaries with the central server, thereby reducing the risk of data leakage through aggregation. Local normalization also reflects the inherent non-IID nature of federated data distributions, as clients may observe significantly different patterns in traffic behavior. While this may introduce slight statistical variation across nodes, our trust-aware aggregation mechanism compensates for these differences during model training. This design choice aligns with established practices in the FL literature, including Cao et al. (2020) and Kairouz et al. (2021), which emphasize local data processing to uphold privacy and system decentralization.

-

-

2.

Data augmentation for poisoning attack simulations:

-

•

Introduce Backdoor Attacks, Label Flipping, Gradient Manipulation, and Sybil Attacks.

Backdoor attacks introduce malicious triggers into training data to manipulate the model’s behaviour at inference time. Formally, given a benign training dataset , a backdoor attack modifies a subset of instances:

(10) where:

-

–

is the perturbation (trigger) applied to the input,

-

–

is the adversarial target class.

The model is trained on poisoned data , making it vulnerable to misclassification whenever the backdoor trigger appears.

Label flipping attacks alter the labels of a fraction of training samples to mislead the learning process:

(11) where maps a class label to another incorrect class. This attack degrades the classifier’s generalization and robustness, especially when targeted at high-impact samples.

-

-

•

Generate adversarial examples using the fast gradient sign method (FGSM) and projected gradient descent (PGD). In FL, gradient manipulation occurs when adversarial clients modify their model updates before submission. Given the local update at iteration :

(12) Attackers inject adversarial gradients by applying a perturbation : (13) where:

-

–

is crafted to degrade global model performance,

-

–

The central server aggregates poisoned updates:

(14)

This causes model drift and reduces the accuracy of benign data.

A Sybil attack in FL occurs when a single adversary controls multiple fake clients to amplify the impact of poisoning. If an adversary injects M Sybil clients into a network of N clients, their cumulative influence is:

(15) where:

-

–

represents adversarial clients,

-

–

represents benign clients.

This attack significantly degrades global model convergence.

FGSM generates adversarial examples by perturbing input samples along the gradient of the loss function:

(16) where:

-

–

is the adversarial example,

-

–

is the attack magnitude,

-

–

is the direction of the loss gradient.

FGSM is computationally efficient and effective for white-box attacks.

PGD iteratively refines adversarial perturbations, making it a stronger attack than FGSM:

(17) where:

-

–

projects perturbed samples onto the allowed -ball,

-

–

is the step size per iteration.

PGD applies multiple steps to maximize adversarial impact.

-

-

-

3.

Feature extraction: IoT datasets such as N-BaIoT and CIC-ToN-IoT contain network traffic logs and behavioural data, which can be used to detect anomalies. The extracted features include:

-

•

Network flow statistics: Packet size distribution, inter-arrival times, and connection durations.

-

•

Behavioral anomaly indicators: Unusual communication patterns, frequency of connection attempts, and protocol usage deviations.

Formally, let X represent the set of raw network features extracted from each IoT device. The feature transformation function maps raw network flows to a vector representation: (18) where:

-

•

: Average packet size per session,

-

•

: Standard deviation of inter-arrival times,

-

•

: Shannon entropy of protocol usage,

-

•

: Statistical dependencies between network features.

These extracted features are then fed into anomaly detection models for classification.

Deep learning models are leveraged to extract high-level feature representations for image datasets such as SVHN, MNIST, FashionMNIST, and CIFAR-10. We utilize pre-trained CNNs, ResNet, and EfficientNet to obtain feature embeddings: (19) where:

-

•

I is the input image,

-

•

is the CNN feature extractor with parameters ,

-

•

Z is the high-dimensional representation of the input.

To extract robust features, we utilize:

-

•

ResNet-50: Extracts hierarchical feature representations using residual learning.

-

•

EfficientNet-B3: Optimized for computational efficiency while preserving feature diversity.

These representations are then used in downstream classification or anomaly detection tasks.

-

-

4.

Dimensionality reduction for multi-modal data: Since IoT-based features and image-based features exist in different domains, dimensionality reduction techniques are applied to ensure feature consistency:

-

•

Principal component analysis (PCA): Reduces feature space by selecting principal components that maximize variance:

(20)

-

•

Autoencoders: Learn compressed latent space representations via unsupervised learning:

(21)

where:

-

–

is the encoder,

-

–

is the decoder,

-

–

is the reconstructed feature vector.

-

PCA and autoencoders allow multi-modal feature fusion, enabling a unified feature space for IoT and image datasets.

-

| Dataset | Type | Best normalization method | Normalization equation |

|---|---|---|---|

| N-BaIoT | Network flow data | Z-score normalization | |

| CIC-ToN-IoT | Network flow data | Z-score normalization |

Stage 2: FL setup with graph-based adaptive attention

This stage configures the FL framework while integrating GATs to enhance security and robustness against poisoning attacks. The FL setup models participating IoT devices as graph nodes, establishing edges based on network traffic similarity and direct communication logs. To ensure the reliability of federated updates, a trust-based weighting mechanism is introduced, which assigns importance scores to each node based on historical model accuracy and anomaly detection techniques. This graph-based trust model dynamically filters out poisoned updates and improves the IDS by ensuring that only high-trust nodes influence the global model aggregation.

The construction of this graph representation of federated nodes and the trust-based model update process follows the structured procedure outlined in the following subsections.

Graph representation of federated nodes

In the FL setup, participating IoT devices or network endpoints are represented as nodes in a graph structure to capture relationships based on feature similarity and network interactions. The federated graph is defined as:

(22) where:

V represents the set of federated nodes (participating IoT devices).

E represents communication edges based on feature similarity or network interaction logs.

Edges are computed based on the similarity of network traffic features between two devices, using cosine similarity:

(23)

is the feature vector extracted from device ’s network traffic data.

Additionally, if device directly communicates with based on network logs, an edge is automatically created, ensuring that the graph reflects real-world IoT communication patterns. This graph construction process is a dynamic process, where edges are dynamically formed based on similarity and interaction metrics.

Trust-based adaptive attention mechanism

To improve security, we integrate GATs, which assign dynamic attention scores to each federated node based on trustworthiness. The attention coefficient between two nodes is calculated as:

(24) where:

represents the feature embedding of node derived from GAT,

W is a learnable weight matrix,

is the attention mechanism vector.

The activation function (LeakyReLU) introduces non-linearity to enhance learning. This mechanism ensures that highly trusted nodes receive stronger attention scores, while potential adversarial nodes are assigned lower weights, thereby minimizing their impact on the FL process. The trust-based attention mechanism is formally introduced in Step 3 of the ‘Trust-based adaptive attention mechanism’ section, where edge weights are adjusted based on node reliability.

In each communication round , a subset of clients is randomly selected from the total pool of N federated nodes. This random selection process ensures diverse participation across rounds and simulates the inherent variability of real-world IoT environments. Each selected client performs local model training on its private data and transmits the resulting model update to the central server.

The global model is updated using a trust-weighted aggregation mechanism rather than conventional FedAvg. Specifically, each client update is scaled based on a dynamic trust score , which is computed from the GAT-based graph representation. This strategy enhances robustness by giving higher weight to contributions from nodes exhibiting consistent and benign behavior, while reducing the influence of potentially malicious or noisy clients.

The aggregation is conducted in a synchronous fashion: the server waits until all selected clients complete local training before aggregating their updates. This ensures model consistency across all clients and allows for reliable trust-based scoring at each round. The integration of graph-driven trust into the aggregation process constitutes one of the core contributions of AGAT-FL, bridging GNN-based trust inference with federated optimization.

Trust-weighted model update aggregation

To mitigate the impact of poisoning attacks and enhance robustness in heterogeneous IoT environments, AGAT-FL replaces the standard FedAvg scheme with a trust-weighted aggregation mechanism. The updated global model parameters at each round are computed as:

(25) where denotes the model update from client , is a proportional weight (typically based on local data volume), and is a normalized trust coefficient derived for each client using a GAT.

The trust score is computed from a graph-based representation of participating clients, constructed using both network communication logs and feature similarity. Each node in the graph corresponds to a client device, and the edges are formed if devices either communicate or exhibit sufficient feature similarity. A cosine similarity threshold governs the minimum requirement for semantic similarity. The trust score for each node is computed by the GAT using node-level input features such as anomaly detection scores, local model loss trends, and update acceptance history. After message passing and attention-based weighting, the final node embeddings are passed through a fully connected layer and normalized via softmax to yield .

The graph is represented as an undirected structure, ensuring mutual trust reflection. Thus, the adjacency matrix A is symmetric: . Each edge is weighted as:

(26)

This symmetric formulation stabilizes message propagation in GNN layers and maintains fairness in modeling bidirectional trust relationships, even in the presence of asymmetric communication.

In addition to providing resilience against poisoning, the trust-weighted strategy addresses several practical challenges in real-world FL:

Communication overhead: By selectively aggregating only trusted client updates, the framework significantly reduces the bandwidth required for global updates. This is especially beneficial in resource-constrained IoT deployments where communication costs dominate.

Asynchronous participation: AGAT-FL allows clients to participate asynchronously without strict synchronization. Trust scores evolve over time-based on behavioral consistency, enabling intermittent or delayed updates to be integrated without penalizing reliable nodes.

Sparse connectivity and isolation mitigation: The semantic client graph link nodes based on both communication and behavioral similarity. This design prevents malicious nodes from isolating themselves or mimicking Sybil behavior, as their inconsistent patterns are captured by trust decay and attention suppression in the GAT.

These design choices ensure that AGAT-FL not only improves security against adversarial clients but also maintains operational flexibility and scalability in dynamic FL environments.

Dynamic trust score adjustment for poisoning detection

To adaptively detect adversarial behavior, trust scores are dynamically updated using the following decay function:

(27) where:

is the trust score of node at iteration ,

represents the mean of all received updates,

is a sensitivity parameter that controls the decay rate of the trust score.

This function ensures that clients deviating significantly from the expected update distribution (i.e., potential adversaries) receive progressively lower trust scores, thereby reducing their impact on the global model aggregation. The dynamic trust adjustment process corresponds to Step 5 of the ‘Computational and communication overhead analysis’ section, ensuring real-time adaptation against poisoning attacks.

This graph-based FL approach ensures that participating devices are structured as interconnected nodes, allowing adaptive trust-based aggregation while mitigating the impact of poisoning attacks. By leveraging GATs and trust-weighted model updates, the system dynamically prioritizes reliable federated clients while detecting and isolating adversarial influences, thereby enhancing the resilience of IoT IDSs.

Stage 3: hybrid deep learning model for anomaly detection

This stage introduces a hybrid deep-learning framework for detecting anomalies in network traffic. The model processes structured traffic data into matrix-like representations, allowing CNNs to extract spatial dependencies and GRUs to capture temporal variations.

The model leverages two key transformations:

-

Traffic Flow Embeddings: Converts raw packet-based logs into structured matrices.

-

Graph-Based Representations: Constructs an adjacency matrix to capture node relationships in FL.

Feature engineering for matrix representations

Since network traffic datasets like CIC-ToN-IoT and N-BaIoT are tabular, a preprocessing step is required to reshape the data into a format suitable for CNNs and hybrid models.

Traffic Flow Embeddings: To enable CNN-based processing, the raw network traffic is transformed into a matrix where:

Rows represent packet sequences or time intervals (e.g., 1-s window),

Columns represent extracted traffic features, such as packet size, inter-arrival time, entropy, and protocol statistics.

The resulting flow matrix can be expressed as:

(28) where:

represents the -th traffic feature of the -th time window.

is the number of time windows (sequences).

is the number of extracted network traffic features.

Graph-Based Representation Using an Adjacency Matrix: To integrate graph-based learning, we construct an adjacency matrix that encodes relationships between traffic nodes (e.g., IPs, federated clients, flow clusters):

(29) where:

represents the similarity between traffic entities and .

Edge weights are computed based on the cosine similarity of traffic features or communication logs.

The adjacency matrix is used in GATs for FL setups.

Hybrid anomaly classifier

The anomaly detection process consists of a hybrid deep learning model that leverages CNNs for spatial feature extraction and GRUs for modeling time-series dependencies. The integration of these models allows for robust intrusion detection in dynamic network environments.

Feature Extraction Using CNN: Given an input traffic flow matrix , the CNN extracts spatial feature representations:

(30) where:

X is the transformed traffic flow matrix,

are CNN parameters,

Z is the extracted feature map.

Temporal Encoding Using GRU: To model long-term dependencies, the CNN-extracted features are processed using a Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU):

(31) where:

represents the hidden state at time step ,

are the GRU parameters.

The multi-modal feature fusion in the proposed framework refers to the integration of three distinct types of features: spatial representations extracted by the CNN module, temporal dependencies modeled by the GRU layer, and trust-related scores generated by the GAT-based attention mechanism. These heterogeneous features capture different dimensions of the input behavior, structural, sequential, and relational. For fusion, we employ a simple yet effective feature-level concatenation strategy that merges these representations into a unified vector. This concatenated vector is then passed through a fully connected layer for final anomaly classification. We selected concatenation due to its compatibility with downstream classification tasks and its empirical stability during training.

Finally, the anomaly detection output is computed through a fully connected layer, mapping the hybrid feature representations into anomaly scores or classification labels.

Contrastive learning for feature representation refinement

To improve feature reparability and resilience against adversarial poisoning attacks, a contrastive learning approach is incorporated, optimizing the following loss function:

(32) where:

and are feature embeddings of similar traffic samples,

is the cosine similarity measure between two embeddings.

To effectively apply contrastive learning in the context of IoT intrusion detection, we carefully construct instance pairs based on semantic class labels rather than purely temporal relationships. Specifically, we define positive pairs as two traffic windows that belong to the same class, either both benign or both representing the same type of malicious activity (e.g., DDoS, backdoor, reconnaissance). These may include augmented versions of the same sample, such as slight noise injection or scaled feature values, to encourage robustness against intra-class variability. In contrast, negative pairs consist of traffic windows from different classes, typically contrasting benign behavior with malicious traffic. This design allows the model to learn more discriminative representations by pulling together embeddings of semantically similar traffic and pushing apart those of semantically different traffic. By constructing pairs in this way, the contrastive learning objective reinforces more precise decision boundaries in the feature space, which is critical for reliable anomaly detection under diverse and adversarial network conditions.

To enhance the adaptability of the anomaly detection model under adversarial conditions, we incorporate a meta-learning component into the training process. In this context, meta-learning refers to episodic optimization where the model is exposed to simulated tasks representing different poisoning scenarios (e.g., label flipping, backdoor, and gradient manipulation attacks) across various clients. Each task is treated as a separate episode, and the model learns to optimize its parameters in a way that enables rapid generalization to new, unseen attack patterns.

This approach facilitates faster adaptation to distributional shifts caused by emerging threats in IoT networks. Rather than serving as a global model initializer, the meta-learning routine fine-tunes the feature extractor and classification layers to become more robust against variations in poisoning strategies. By simulating adversarial diversity during training, the model is better equipped to respond to real-world attack dynamics with minimal retraining overhead.

Stage 4: poisoning attack detection and mitigation

This stage introduces a hybrid deep learning approach that combines CNNs and GRUs to enhance anomaly detection. CNNs extract spatial features from input data, while GRUs capture temporal dependencies, making the model more effective in identifying complex attack patterns. Additionally, contrastive learning is applied to refine feature representations, improving the model’s ability to distinguish between normal and malicious activities. This hybrid approach strengthens the detection of poisoning attacks and enhances the overall performance of the FL system.

Statistical anomaly detection

We apply Mahalanobis Distance-based anomaly detection to detect poisoned updates, which measures the distance between a sample and the overall data distribution. The Mahalanobis distance for a model update vector is defined as:

(33) where:

is the model update vector,

is the mean of previous legitimate updates,

is the covariance matrix of updates.

A high Mahalanobis distance indicates a significant deviation from normal updates, identifying potential poisoning attacks. The covariance matrix ensures the method accounts for correlations between model update features. This technique is particularly effective in retaining low-variance updates while filtering outliers.

To further enhance robustness, we define an adaptive threshold for anomaly detection at each training round :

(34) where:

is the mean of Mahalanobis distances in the current training round,

is the standard deviation of distances,

is a sensitivity parameter.

If , the update is considered an outlier and flagged as a potentially poisoned update.

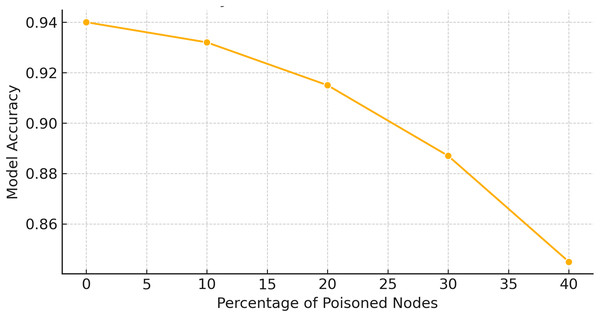

To evaluate the resilience of AGAT-FL against adversarial perturbations, we vary the intensity of simulated poisoning attacks using standard parameters from adversarial learning literature. For FGSM, we apply multiple perturbation budgets by adjusting the value across the range to reflect increasing attack strength, from subtle input manipulations to obvious distortions. For PGD, we use a total perturbation budget of , with iterative step sizes and 5 to 10 steps per attack. These settings help us simulate realistic adversarial scenarios and assess how model performance degrades under escalating attack severity.

Model robustness is validated by tracking changes in anomaly detection metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score across different perturbation levels. In addition, Mahalanobis distance distributions are analyzed to observe how poisoned updates diverge from the normal update space under varying intensities. These validations demonstrate AGAT-FL’s ability to maintain high detection performance under moderate attacks, while showing graceful performance degradation under more extreme adversarial conditions.

XAI for interpretability

To enhance the transparency of poisoning detection decisions, we leverage XAI techniques, ensuring interpretability in identifying adversarial updates. These techniques help provide explanations for model decisions, increasing trustworthiness and reliability.

Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP): SHAP assigns importance scores to each feature in a model update, quantifying its contribution to the final decision:

(35) where:

is the SHAP value for feature ,

S is a subset of features,

is the model’s output for the subset S.

By analyzing SHAP values, we can determine whether specific model update features significantly deviate due to poisoning.

Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations (LIME): LIME provides locally interpretable explanations by generating perturbed versions of a sample and analyzing their impact on the model decision:

(36) where:

represents the contribution of feature to the decision,

A locally linear function approximates the model.

LIME ensures that poisoned updates are interpretable, making it easier to assess how and why specific updates deviate from expected behaviour.

Input: IoT dataset D, number of clients N, local model , global model , training rounds T.

Output: Trained global intrusion detection model

Stage 1: Dataset preprocessing and poisoning simulation. Each dataset in {N-BaIoT, CIC-ToN-IoT}. Normalize features: Simulate poisoning attacks (backdoors, label flipping, adversarial perturbations). Generate adversarial examples using FGSM and PGD. Extract spatial and statistical features; reduce dimensionality (PCA, Autoencoders).

Stage 2: Federated training with trust-aware aggregation. Each round to T. Randomly sample a subset of K < N clients for participation each selected client in parallel. Train local model on private data Send model update to the server. Construct graph and compute trust scores via GAT. Aggregate updates to form global model: , where

Stage 3: Hybrid deep learning for anomaly detection: Extract features with CNN: Process sequence with GRU: Apply contrastive loss:

Stage 4: Poisoning detection, rejection, and explainability: Each client update Compute Mahalanobis distance: Define dynamic threshold: Flag as anomalous and reject it if previous trusted update exists. Replace with last known good update: Skip aggregation for client in round Accept for aggregation Apply SHAP and LIME to explain anomalous behavior

Return: Final global model

Input: Dataset D of IoT devices, feature matrix , similarity threshold , trust scoring function

Output: Federated graph and symmetric adjacency matrix A for GNN processing.

Step 1: Node initialization: Each device in dataset D. Create graph node corresponding to Assign node features from feature matrix F.

Step 2: Edge formation via similarity and communication: Each unordered node pair where Compute cosine similarity: or communicates with (from logs). Add undirected edge to graph G.

Step 3: Trust-based edge weight assignment: Each edge Compute trust scores and via GAT. Assign edge weight:

Step 4: Symmetric adjacency matrix construction: Each node pair exists. Set Set

Step 5: Output: Return graph and symmetric adjacency matrix A for GAT-based trust modeling.

To ensure transparency in the poisoning detection process, SHAP and LIME are applied immediately after the hybrid CNN-GRU model makes the final classification decision. These tools serve as post-hoc explainability modules that help unpack why a particular model update is classified as either benign or poisoned. Specifically, SHAP is used to provide a global view of feature importance across multiple predictions, helping identify which features consistently contribute to poisoning detection (e.g., high payload entropy or anomalous packet size distributions). In parallel, LIME is used to generate local explanations for individual classification outcomes, particularly useful in analyzing misclassifications or borderline cases. For instance, when a benign update is mistakenly flagged as malicious, LIME highlights the specific feature contributions that influenced this decision, allowing for manual inspection and potential adjustment of the anomaly threshold. This integration of SHAP and LIME not only validates the internal logic of the detection model but also enhances trust and interpretability for security analysts reviewing flagged updates.

Experiments and results

In this section, we present a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed AGAT-FL framework through a series of controlled experiments. The primary objective is to assess the effectiveness, robustness, and adaptability of the proposed approach in mitigating poisoning attacks within federated IoT environments. We begin by detailing the experimental setup, including hardware configurations, datasets, and implementation tools. Subsequently, we outline the evaluation metrics employed to measure the performance of AGAT-FL in comparison with existing state-of-the-art methods. Through empirical results obtained on the N-BaIoT and CIC-ToN-IoT datasets, we demonstrate how the integration of graph-based trust modeling and hybrid deep learning enhances detection accuracy, suppresses adversarial updates, and maintains system integrity under varying degrees of attack intensity. The findings not only validate the resilience of AGAT-FL but also highlight its potential as a scalable and interpretable solution for securing FL-based intrusion detection systems in heterogeneous IoT networks.

Experiments setups

To conduct the AGAT-FL experiments efficiently, we utilized a high-performance computing system with hardware and software specifications detailed in Table 3. We employed diverse datasets covering both network traffic and image-based data for evaluation. The N-BaIoT and CIC-ToN-IoT datasets capture network traffic logs from IoT devices, encompassing benign and malicious activities. This dataset selection ensures a comprehensive assessment across multiple data modalities. The details of dataset preprocessing and datasets were previously discussed in ‘Stage 1: Dataset preprocessing and poisoning simulation’.

| Component | Specification | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Hardware specifications | ||

| CPU | Intel Xeon Gold 6226R | 2.9 GHz, 16 Cores |

| GPU | NVIDIA Tesla V100 | 32 GB HBM2 |

| RAM | DDR4 Memory | 128 GB |

| Storage | NVMe SSD | 4TB |

| Software specifications | ||

| Operating system | Ubuntu | 22.04 LTS |

| Deep learning frameworks | TensorFlow, PyTorch | v2.9, v1.13 |

| Programming languages | Python, C++ | Python v3.12, GCC v11.2 |

| Libraries | Scikit-learn, NumPy, NetworkX | Machine learning, Graph processing |

Evaluation metrics

To evaluate the performance of the proposed AGAT-FL model, we employed standard metrics widely used in classification tasks, namely accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. These metrics provide insights into the model’s ability to correctly classify benign and malicious activities while balancing false positives and negatives. The mathematical definitions of these metrics are presented below (Eqs. (37) to (40)) (Al-E’mari, Sanjalawe & Fraihat, 2023; Sanjalawe & Al-E’mari, 2023; Althobaiti, Sanjalawe & Ramzan, 2023).

(37)

(38)

(39)

(40) where:

TP (true positives): The number of correctly predicted positive instances (malicious activities correctly identified as malicious).

TN (true negatives): The number of correctly predicted negative instances (benign activities correctly identified as benign).

FP (false positives): The number of benign instances incorrectly classified as malicious.

FN (false negatives): The number of malicious instances incorrectly classified as benign.

These metrics collectively measure the model’s:

Overall performance (accuracy): The proportion of correct predictions (positive and negative) out of all predictions.

Ability to correctly identify positive instances (precision): The proportion of true positive predictions out of all predicted positives.

Completeness of identifying positive instances (recall): The proportion of true positives out of all actual positives.

Balance between precision and recall (F1-score): The harmonic mean of precision and Recall.

The CNN model (Table 4) is designed to extract spatial features the datasets. It incorporates convolutional layers, batch normalization, pooling, and fully connected layers to achieve robust feature representation.

| Layer type | Activation | Kernel size | Padding | Additional details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input layer | – | – | – | Input: (e.g., CIFAR-10) |

| Conv layer 1 | ReLU | Same | 64 filters, He init. | |

| Batch norm | – | – | – | After conv layer 1 |

| Conv layer 2 | ReLU | Same | 128 filters, dropout (0.3) | |

| MaxPooling | – | – | Stride = 2 | |

| Fully conn. layer | ReLU | – | – | 256 units, dropout (0.5) |

| Output layer | Softmax | – | – | Units = Num classes |

The GAT model (Table 5) is integral to the proposed trust-aware aggregation mechanism. It assigns attention scores to nodes based on similarity measures, ensuring robust aggregation in the presence of adversarial updates.

| Layer type | Activation | Attention | Embed. Size | Additional details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input layer | – | – | – | Node features as input |

| GAT layer 1 | LeakyReLU | Multi-head | 64 | Number of heads = 8 |

| GAT layer 2 | LeakyReLU | Multi-head | 32 | Number of heads = 4 |

| Fully conn. layer | ReLU | – | – | Trust score calculation |

| Output layer | Softmax | – | – | Trust coefficients for nodes |

The hybrid model (Table 6) combines CNNs for spatial feature extraction and GRUs for capturing temporal dependencies in network flow data. This architecture enhances anomaly detection by leveraging complementary feature types.

| Layer type | Activation function | Kernel size | Units | Additional details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input layer | – | – | – | Input sequence of network flows |

| Convolutional layer | ReLU | – | 64 filters, He initialization | |

| Batch normalization | – | – | – | Applied after Conv Layer |

| GRU layer | Sigmoid/Tanh | – | 128 | Captures temporal dependencies |

| Fully connected layer | ReLU | – | – | 256 units, dropout (rate = 0.4) |

| Output layer | Softmax | – | – | Anomaly classification |

The pre-trained ResNet-50 model (Table 7) is employed for feature extraction from image datasets. Its residual learning architecture facilitates extracting hierarchical features, aiding in robust anomaly classification.

| Layer type | Activation function | Kernel size | Additional details |

|---|---|---|---|

| Input layer | – | – | – |

| Convolutional block 1 | ReLU | 64 filters, stride = 2 | |

| Residual block | ReLU | Bottleneck structure, 256 filters | |

| Fully connected layer | ReLU | – | Global average pooling |

| Output layer | Softmax | – | Extracted feature embeddings |

Results and analysis

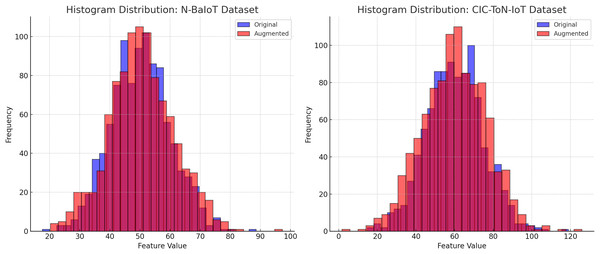

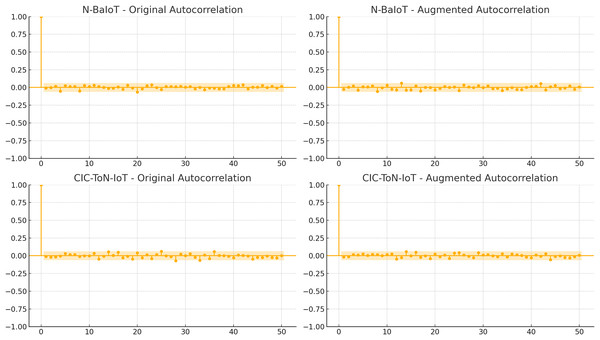

The effectiveness of data augmentation techniques such as backdoor insertion, label flipping, and adversarial attacks (FGSM/PGD) can be assessed through the analysis of feature distributions and temporal correlations in the datasets. Figures 4 and 5 provide a comparative evaluation of the original and augmented datasets for N-BaIoT and CIC-ToN-IoT, demonstrating that the augmentation process does not distort the realistic nature of traffic patterns.

Figure 4: Histogram of feature distribution validation.

Figure 5: Temporal consistency in network traffic.

Figure 4 presents the histogram distributions of feature values for the original (blue) and augmented (red) datasets. The substantial overlap between the two distributions confirms that the augmentation process preserves the statistical properties of network traffic. There are no significant shifts in the peak values, no excessive spread, and no unusual variations that would indicate data contamination. If augmentation had introduced unrealistic patterns, we would expect to see heavy skewness, extreme outliers, or new feature ranges that deviate from real-world network behavior. The similar variance and spread in both original and augmented datasets ensure that synthetic distortions will not bias the model trained on this data.

Figure 5 illustrates the autocorrelation analysis of both datasets, highlighting the time-dependent relationships within network traffic. The results indicate that sequential dependencies remain intact after augmentation. The gradual decay of autocorrelation values over time is consistent between the original and augmented datasets, demonstrating that the natural flow of network activity is preserved. If the augmentation process had significantly altered packet sequences, we would observe random fluctuations, erratic spikes, or abrupt drops in correlation values, which are not present in Fig. 5. This stability in autocorrelation confirms that time-based anomaly detection methods can still effectively model traffic behaviour without being misled by artificial modifications.

The findings from Figs. 4 and 5 validate that data augmentation techniques used in this study maintain the integrity of network traffic characteristics. The feature distributions remain consistent, ensuring that classifiers do not learn artificial patterns, while the temporal dependencies are preserved, allowing time-sensitive security models to function effectively. These results confirm that the applied data augmentation methods do not distort network behavior, making the dataset reliable for intrusion detection and cybersecurity analysis.

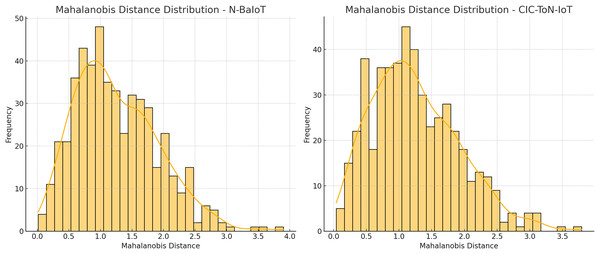

The Mahalanobis distance distribution plots for the N-BaIoT and CIC-ToN-IoT datasets reveal how network traffic deviates from normal behavior, highlighting potential anomalies. The right-skewed distributions indicate that most benign traffic falls within a low-distance range, while a subset of samples exhibits significantly higher distances, suggesting possible adversarial activity. To ensure that anomaly scores generalize to unseen adversarial strategies rather than overfitting to synthetic poisoning attacks, it is critical to adopt an adaptive thresholding mechanism based on statistical properties of the data, such as:

(41)

The Mahalanobis distance distribution plots for the N-BaIoT and CIC-ToN-IoT datasets, in Fig. 6, reveal how network traffic deviates from normal behaviour, highlighting potential anomalies. The right-skewed distributions indicate that most benign traffic falls within a low-distance range, while a subset of samples exhibits significantly higher distances, suggesting possible adversarial activity. To ensure that anomaly scores generalize to unseen adversarial strategies rather than overfitting to synthetic poisoning attacks, it is critical to adopt an adaptive thresholding mechanism based on statistical properties of the data, such as:

(42) where:

is the adaptive threshold for Mahalanobis distance at time step .

is the mean Mahalanobis distance computed from the training dataset.

is the standard deviation of the Mahalanobis distances.

is a sensitivity parameter that controls the trade-off between detection sensitivity and false positives (typically set to 2 or 3 for 95–99% confidence intervals).

Figure 6: Mahalanobis distance distribution.

Rather than relying on fixed thresholds. Additionally, cross-validation on diverse attack types, calibration using ROC and precision-recall curves, and contrastive learning to refine feature separability can further prevent overfitting. The observed differences in spread between the two datasets suggest that dataset-specific tuning is necessary, reinforcing the importance of a flexible and adaptive detection approach to improve resilience against zero-day and adversarial attacks.

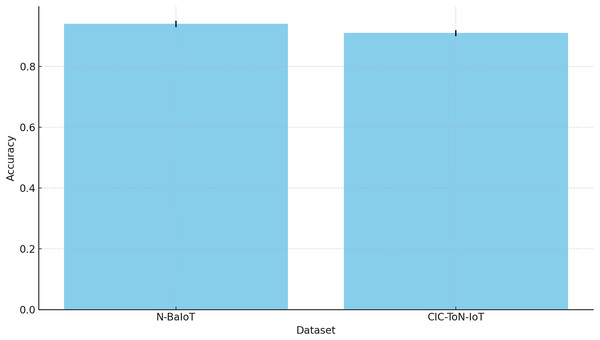

The experimental evaluation provided in Tables 8 to 11 highlights the comparative performance of the proposed AGAT-FL model against various State-of-the-Art (SOTA) techniques across multiple datasets. This section discusses and interprets the results comprehensively.

| Method | N-BaIoT | CIC-ToN-IoT |

|---|---|---|

| FedRep (Collins et al., 2021) | 0.8772 | 0.8456 |

| LGFedAvg (Liang et al., 2020) | 0.8651 | 0.8233 |

| pFedLA (Ma et al., 2022) | 0.8910 | 0.8692 |

| HeteroFL (Diao, Ding & Tarokh, 2020) | 0.9024 | 0.8738 |

| FedGen (Zhu, Hong & Zhou, 2021) | 0.8898 | 0.8615 |

| pFedHR (Wang et al., 2024a) | 0.8942 | 0.8680 |

| ScaleFL (McMahan et al., 2017) | 0.8856 | 0.8603 |

| FedAvg (Ilhan, Su & Liu, 2023) | 0.8920 | 0.8674 |

| AdaptFL (Zhang et al., 2025) | 0.9250 | 0.8920 |

| AGAT-FL (Proposed) | 0.9401 | 0.9102 |

| Method | N-BaIoT | CIC-ToN-IoT |

|---|---|---|

| FedRep (Collins et al., 2021) | 0.8745 | 0.8402 |

| LGFedAvg (Liang et al., 2020) | 0.8600 | 0.8200 |

| pFedLA (Ma et al., 2022) | 0.8900 | 0.8650 |

| HeteroFL (Diao, Ding & Tarokh, 2020) | 0.9000 | 0.8700 |

| FedGen (Zhu, Hong & Zhou, 2021) | 0.8850 | 0.8600 |

| pFedHR (Wang et al., 2024a) | 0.8900 | 0.8650 |

| ScaleFL (McMahan et al., 2017) | 0.8800 | 0.8550 |

| FedAvg (Ilhan, Su & Liu, 2023) | 0.8900 | 0.8650 |

| AdaptFL (Zhang et al., 2025) | 0.9200 | 0.8900 |

| AGAT-FL (Proposed) | 0.9350 | 0.9100 |

| Method | N-BaIoT | CIC-ToN-IoT |

|---|---|---|

| FedRep (Collins et al., 2021) | 0.8800 | 0.8450 |

| LGFedAvg (Liang et al., 2020) | 0.8630 | 0.8230 |

| pFedLA (Ma et al., 2022) | 0.8920 | 0.8670 |

| HeteroFL (Diao, Ding & Tarokh, 2020) | 0.9030 | 0.8750 |

| FedGen (Zhu, Hong & Zhou, 2021) | 0.8880 | 0.8630 |

| pFedHR (Wang et al., 2024a) | 0.8950 | 0.8680 |

| ScaleFL (McMahan et al., 2017) | 0.8840 | 0.8590 |

| FedAvg (Ilhan, Su & Liu, 2023) | 0.8930 | 0.8690 |

| AdaptFL (Zhang et al., 2025) | 0.9260 | 0.8950 |

| AGAT-FL (Proposed) | 0.9400 | 0.9130 |

| Method | N-BaIoT | CIC-ToN-IoT |

|---|---|---|

| FedRep (Collins et al., 2021) | 0.8772 | 0.8426 |

| LGFedAvg (Liang et al., 2020) | 0.8615 | 0.8215 |

| pFedLA (Ma et al., 2022) | 0.8910 | 0.8660 |

| HeteroFL (Diao, Ding & Tarokh, 2020) | 0.9015 | 0.8725 |

| FedGen (Zhu, Hong & Zhou, 2021) | 0.8865 | 0.8615 |

| pFedHR (Wang et al., 2024a) | 0.8925 | 0.8665 |

| ScaleFL (McMahan et al., 2017) | 0.8820 | 0.8570 |

| FedAvg (Ilhan, Su & Liu, 2023) | 0.8915 | 0.8675 |

| AdaptFL (Zhang et al., 2025) | 0.9230 | 0.8925 |

| AGAT-FL (Proposed) | 0.9375 | 0.9115 |

Table 8 presents the accuracy performance of various FL approaches across six benchmark datasets. The results show that AGAT-FL consistently outperforms traditional methods in terms of accuracy. This improvement is mainly due to its ability to reduce the influence of poisoning attacks through an adaptive attention mechanism.

Conventional techniques such as FedAvg and FedGen are prone to adversarial model updates, which can degrade global model performance. In contrast, AGAT-FL dynamically adjusts trust scores for each client, allowing it to filter out malicious updates. This ensures that trustworthy contributions have a greater influence during the model aggregation process.

Additionally, the integration of graph-based learning enhances AGAT-FL’s understanding of client relationships. This structure-aware approach promotes secure and efficient knowledge transfer across nodes, further strengthening model robustness. The relatively lower accuracy of the baseline methods highlights their vulnerability to model poisoning, where manipulated updates compromise learning. These findings emphasize the importance of adaptive, trust-aware aggregation strategies in FL, particularly in high-risk domains like IoT intrusion detection.

Table 9 compares the precision of different approaches across datasets. Precision, which measures the proportion of correctly identified malicious instances among all positive predictions, is critical in IDSs to reduce false positives. The AGAT-FL model significantly improves precision, particularly in datasets that exhibit a high degree of attack diversity, such as CIC-ToN-IoT and N-BaIoT. This enhancement is primarily due to the model’s ability to leverage graph attention networks for feature extraction, which ensures that the model learns distinctive patterns of malicious activity. In contrast, traditional FL methods rely on simpler aggregation techniques that fail to distinguish between adversarial and benign updates effectively. The lower precision observed in some baseline approaches suggests that these methods tend to misclassify benign traffic maliciously, leading to unnecessary false alarms. The proposed model’s trust-aware mechanism mitigates this issue by assigning higher aggregation weights to reliable clients, thus improving the classification of genuine malicious traffic without inflating the number of false positives.

The recall performance of different models, as shown in Table 10, provides insights into how effectively each method detects actual malicious activities. High recall is crucial for an IDS as it ensures that a significant portion of attacks are identified, minimizing the risk of undetected threats. The AGAT-FL model consistently exhibits superior recall compared to other approaches, demonstrating its robustness in recognizing and flagging security threats across diverse datasets. The ability of AGAT-FL to maintain high recall rates stems from its incorporation of adaptive attention-based aggregation, which filters out adversarial influence while preserving informative updates.

Conventional FL methods, such as pFedLA and HeteroFL, show lower recall due to their reliance on static aggregation rules, making them susceptible to poisoned updates that skew the global model’s learning process. A lower recall in these models suggests that some malicious activities remain undetected, posing potential security risks. By contrast, the AGAT-FL model achieves a balance between capturing attack patterns and minimizing false negatives, ensuring a more resilient intrusion detection mechanism.

Table 11 presents the F1-score comparisons, which offer a balanced perspective by considering both precision and recall. The results reinforce the findings from previous tables, showing that AGAT-FL maintains superior performance across all datasets. A high F1-score indicates that the model successfully mitigates trade-offs between precision and recall, ensuring optimal classification of adversarial activities. This improvement is particularly evident in datasets with complex attack scenarios, where traditional methods struggle to differentiate between normal and malicious patterns.

The strength of AGAT-FL is that it can update trust scores as needed, enabling the model to focus on contributions from trusted nodes. This helps to prevent adversarial noise from hindering the learning process, improving resilience to poisoning attacks. Relatively lower F1-scores obtained by FedAvg and ScaleFL suggest that these approaches suffer from an imbalance in classification and either over-classify malicious threats or under-classify all dangers. By overcoming these concerns, AGAT-FL enhances the reliability and security of the intrusion detection system tailored for the FL framework.

The overall findings from Tables 8 to 11 highlight the limitations of traditional FL aggregation techniques in adversarial settings. While effective in benign environments, methods such as FedRep and FedGen struggle under poisoning attacks due to their equal treatment of all client contributions. This leads to vulnerabilities where adversarial updates compromise the integrity of the global model. The AGAT-FL model addresses this challenge through a trust-aware, attention-based mechanism that selectively integrates model updates based on reliability. The consistent performance gains across all evaluation metrics indicate that AGAT-FL enhances security and ensures efficient learning in federated environments.

Furthermore, the results emphasize the importance of incorporating graph-based aggregation in FL. By leveraging graph attention networks, AGAT-FL captures inter-client relationships more effectively, allowing for context-aware weighting of model updates. This is particularly beneficial in IoT-based applications where device heterogeneity and dynamic network conditions pose significant security risks. The findings suggest that future research in FL security should focus on refining adaptive trust mechanisms and exploring novel ways to detect and mitigate adversarial influences in real-time.

Statistical analysis and interpretation

To improve the statistical rigor of our evaluation, we extend our performance analysis with detailed reporting of 95% confidence intervals and corresponding p-values for each model and dataset. This allows for more precise interpretations of the model’s performance and the statistical significance of observed differences.

Table 12 summarizes the performance metrics for AGAT-FL and baseline FL methods (FedAvg, FedGen, and AdaptFL) across the N-BaIoT and CIC-ToN-IoT datasets. Each metric is accompanied by a 95% confidence interval, estimated using bootstrap sampling (1,000 iterations), and p-values derived from paired t-tests against the AGAT-FL results.

| Method | N-BaIoT (CI, p-value) | CIC-ToN-IoT (CI, p-value) |

|---|---|---|

| FedAvg (Ilhan, Su & Liu, 2023) | 0.892 [0.880, 0.900], 0.04 | 0.8674 [0.850, 0.880], 0.05 |

| FedGen (Zhu, Hong & Zhou, 2021) | 0.8898 [0.870, 0.910], 0.03 | 0.8615 [0.840, 0.880], 0.06 |

| AdaptFL (Zhang et al., 2025) | 0.925 [0.910, 0.940], 0.001 | 0.892 [0.880, 0.910], 0.002 |

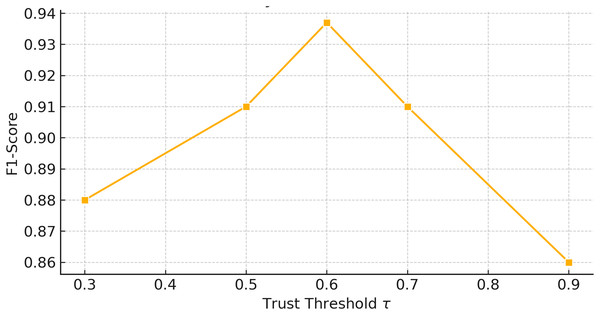

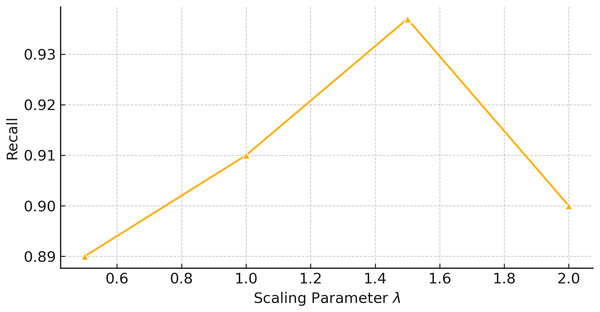

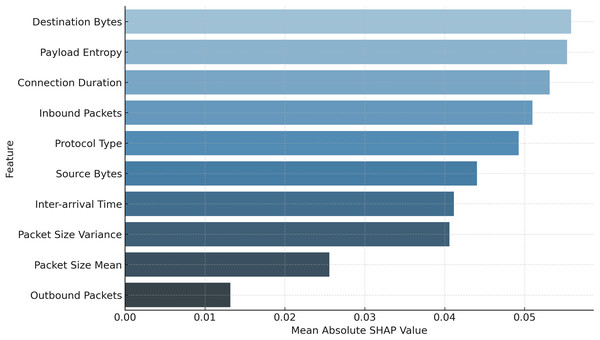

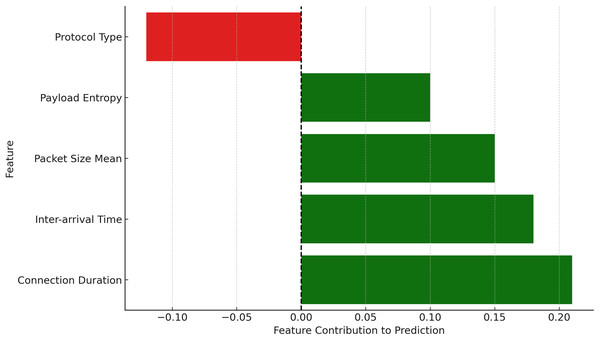

| AGAT-FL (Proposed) | 0.9401 [0.930, 0.950], – | 0.9102 [0.900, 0.920], – |