Exploring generative artificial intelligence: a comprehensive guide

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Consolato Sergi

- Subject Areas

- Artificial Intelligence, Computer Vision

- Keywords

- Generative AI, Generative models, Midjourney, Transformers, Diffusion models

- Copyright

- © 2026 Shoitan et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2026. Exploring generative artificial intelligence: a comprehensive guide. PeerJ Computer Science 12:e3276 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3276

Abstract

Generative artificial intelligence (GAI), a specialized branch of artificial intelligence, has developed as a dynamic discipline that drives innovation and creativity across several domains. It is concerned with creating models that can autonomously produce novel text, images, videos, music, 3D, code, and more. GAI is distinguished by its capacity to acquire knowledge from extensive datasets, identify recurring patterns, capture distributions, and produce novel content demonstrating similar features. This review presents a comprehensive historical overview of the development and progression of GAI techniques over the years. Various essential methodologies employed in developing GAI are also discussed, including Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), Variational AutoEncoders (VAEs), transformers, and diffusion models. Moreover, a detailed overview of the technologies used in GAI is provided for generating images, videos, music, code, and text, such as ChatGPT, DALL-E, Midjourney, Claude, Bard, GitHub Copilot, and others. The research subsequently introduces the different datasets used to train the GAI models and the evaluation metrics for evaluating their performances. Ultimately, the research investigates the diverse applications of GAI across various domains, challenges, and ethical implications.

Introduction

The way many activities are tackled in the current world has been transformed by artificial intelligence (AI). AI refers to the systems that can acquire knowledge from input data and utilize it to formulate decisions or predictions (Mukhamediev et al., 2022; Saghiri et al., 2022). AI has permeated every aspect of our lives across different sectors, such as healthcare, education, human resources, etc. Imagine you are in a football match against a computer that knows all the rules, anticipates your moves, and follows pre-established strategies instead of developing new tactics during the game. Additional instances of conventional AI include voice assistants (Sáiz-Manzanares, Marticorena-Sánchez & Ochoa-Orihuel, 2020; Bălan, 2023) such as Siri (Apple, 2023), Cortana (Microsoft, 2014), Google Assistant (Google Assistant, 2016) or Alexa (Alexa, 2025) and recommendation systems employed by social media, Spotify, Netflix, Linkedin or Amazon (Zhang, Lu & Jin, 2021). These AI systems have been trained to adhere to specific guidelines and perform tasks proficiently but do not generate novel content or ideas.

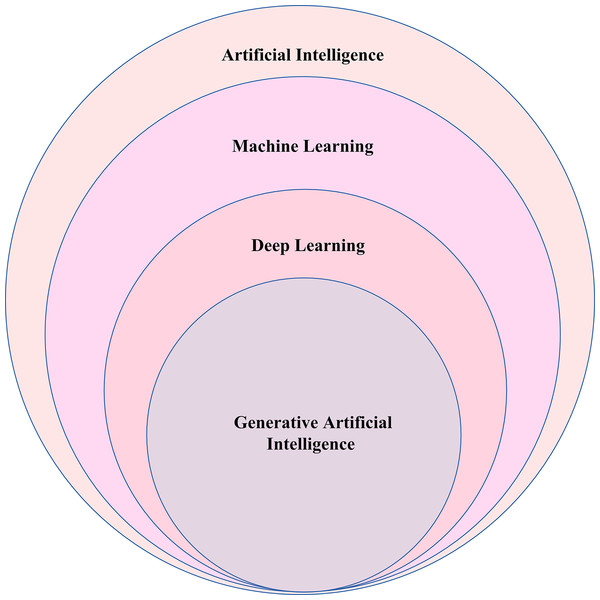

Recently, there has been a rise in the development and application of generative artificial intelligence (GAI) (Zant, Kouw & Schomaker, 2013; Castelli & Manzoni, 2022; Bandi, Adapa & Kuchi, 2023; Dasgupta, Venugopal & Gupta, 2023; Feuerriegel et al., 2023; Shokrollahi et al., 2023; Taulli, 2023). GAI involves training computers in unsupervised and semi-supervised ways to produce new text, images, videos, or programming code related to the trained data in response to instructions or prompts provided by the user. However, people frequently confuse “GAI” and “AI.” AI is a broad domain within computer science that focuses on developing systems and machines capable of performing tasks that imitate human intelligence. AI entails training computers to identify features in data and generate predictions based on those features. Within the field of AI, there are various subsets and specialized areas, including machine learning, deep learning, GAI, Large Language Models (LLMs), and more. Figure 1 below helps to visualize the relationship between AI and GAI.

Figure 1: Relationship between AI and generative artificial intelligence (GAI).

Scope of this survey

Lately, various research reviews have been introduced to deepen our understanding of GAI concepts. These reviews typically fall into two main categories. The first type focuses on a single aspect, such as models, ethical concerns, challenges, limitations or applications (Gozalo-Brizuela & Garrido-Merchán, 2023; Iglesias, Talavera & Díaz-Álvarez, 2023; Wang et al., 2024; Fuest et al., 2024). While these studies offer deep insights into their specific topics, they often lack a broad perspective, making it harder for newcomers to see the full landscape of GAI. The second type covers multiple aspects, including models, datasets, applications, and ethical issues (Bandi, Adapa & Kuchi, 2023; Bengesi et al., 2024; Sengar et al., 2024; Raut & Singh, 2024). However, even these broader surveys often leave out key details, creating gaps in the overall understanding of GAI’s development and impact. This article addresses a crucial gap in GAI research by providing a comprehensive and up-to-date survey that connects multiple aspects of the field. This research work takes a broader approach, covering the evolution of GAI, its foundational models, real-world tools, datasets, evaluation metrics, and ethical implications. It presents a detailed comparison of key models like Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), Diffusion Models, and Transformers, highlighting their strengths, limitations, and trade-offs. Additionally, the article explores practical applications across industries, evaluates the datasets used to train these models, and discusses benchmarking techniques to assess their performance. It also emphasizes ethical challenges like bias, misinformation, and privacy concerns while suggesting future research directions. By bridging these gaps, this article serves as a valuable resource for researchers, graduate students, industry professionals, and policymakers seeking a well-rounded understanding of GAI’s impact and future potential.

Survey methodology

This review is conducted to explore the evolving landscape of GAI and to provide a clearer understanding of its foundations, growth, and current capabilities. As a starting point, we define key research questions to guide our investigation, including:

What exactly is GAI, and how does it differ from traditional AI methods?

What historical milestones and advancements have fueled the rapid growth of GAI?

What are the core models and technologies powering today’s GAI systems?

How can we ensure that GAI is developed in a reliable, ethical, and socially responsible way?

Search terms and keywords

This review draws on a wide range of sources, using carefully chosen keywords to search peer-reviewed journals such as MDPI, Springer, IEEE, and Elsevier, as well as Google Scholar and arXiv for recent preprints. In addition, we used Google searches to reach official websites of developers and companies, helping us include up-to-date information and firsthand insights directly from those driving innovations in GAI.

Comprehensive search queries are formulated using a combination of relevant keywords to ensure broad coverage of methods, models, applications, challenges, and ethical considerations in GAI. These keywords include terms such as “Generative Artificial Intelligence,” “Generative AI,” “GAN” OR “Generative Adversarial Networks,” “VAE” OR “Variational Autoencoder,” “Diffusion Models,” “Transformer Models,” “Large Language Models” OR “LLM,” “Ethical implications of Generative AI,” “Applications of Generative AI,” “Datasets for Generative AI,” “Evaluation metrics for Generative AI,” “Generative AI challenges,” “GAI limitations,” and “GAI ethical implications.” We also adapt and refine these keywords during the search process as we identify emerging trends, adding terms like “Stable Diffusion,” “foundation models,” as well as tool-specific keywords such as “ChatGPT” and “DALL·E,” to capture the latest developments and practical implementations within the field.

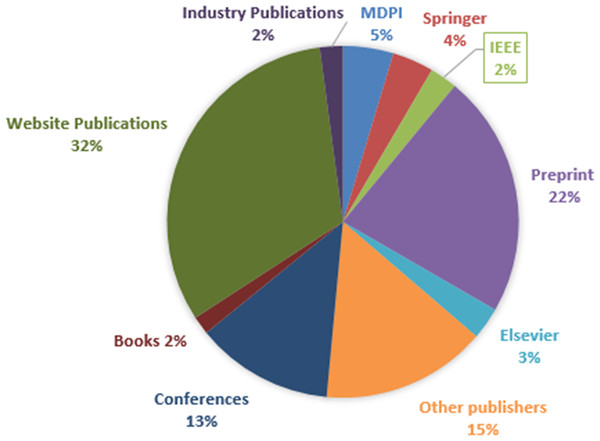

Search engines and databases

The literature search is conducted iteratively from November 2023 to December 2024, rather than in a single batch, to keep up with the rapid pace of new publications in GAI. During this period, a significant number of research articles are collected, primarily published between 2020 and 2024, reflecting the field’s recent surge in activity. In Fig. 2, the sources cited in this review span a broad range of publications, including websites, preprints, and conference papers, highlighting the fast-paced and open nature of GAI research. The websites listed are mainly owned by the developers or companies behind GAI, offering firsthand updates and insights into their latest innovations. On the other hand, peer-reviewed journals like MDPI, Springer, IEEE, and Elsevier contribute academic depth and reliability, delivering thorough analyses along with valuable perspectives from books and industry reports. This blend of sources ensures a comprehensive view of the field.

Figure 2: Distribution of references by source type in the surveyed literature.

Criteria for Inclusion and exclusion

An initial search retrieves 320 articles from selected databases and online sources. Duplicates are removed based on manual checks in Mendeley, resulting in a refined set of unique articles. Titles and abstracts are screened for relevance, with a focus on studies discussing GAI methods, models, applications, datasets, evaluation metrics, and ethical or societal implications. Articles that are off-topic or non-English are excluded during this stage. As GAI is a fast-moving field, recent and reliable sources such as preprints, company websites, peer-reviewed journals, and top conferences from 2020 to 2024 are prioritized. Through this careful process, approximately 237 articles are selected for full-text review, forming the basis of this review and ensuring a comprehensive and up-to-date perspective on the field.

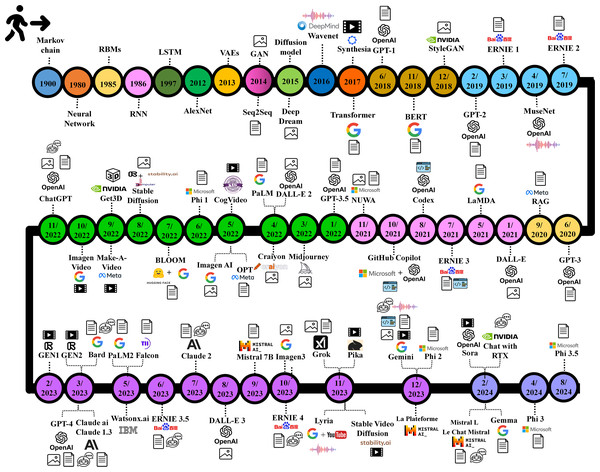

GAI history

The history of GAI has deep roots, beginning in the early stages of AI. In this research article, this evolution is outlined, starting from the 1900s and progressing to its development in the present day.

1900 to 2019

Among the early instances of GAI is the “Markov Chain,” a statistical technique devised by Andrey Markov in the early 1900s (Link, 2006). Markov chains, a relatively simple and widely applied method, serve as a statistical model for random processes. Their utility spans diverse domains, including text generation. After the 1980s, there is notable advancement in GAI, particularly with the emergence and development of neural networks (Gad & Jarmouni, 1995). In 1985, Ackley, Hinton & Sejnowski (1985) invented restricted Boltzmann machines (RBMs). RBMs, a form of neural network, can grasp intricate data distributions and generate novel data informed by those distributions. In December 1997, Hochreiter & Schmidhuber (1997) proposed a Long Short-Term Memory model (LSTM) to mitigate the issue of vanishing gradients in conventional Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN) (DiPietro & Hager, 2019). This enhancement enables more effective management of long-range dependencies within sequential data, which have shown to be very efficient in fields such as language modeling and text production.

Over the years, AI has experienced significant transformation, introducing new algorithms, methodologies, and various applications. In 2012, Krizhevsky, Sutskever & Hinton (2012) developed a convolutional neural network (CNN) named Alexnet that win the ImageNet large scale visual recognition challenge with 75% accuracy. It demonstrates the ability of neural networks to comprehend complex patterns in images, resulting in significant advancements in image classification and object recognition. Additionally, it marks the first utilization of Nvidia’s GPU for machine learning purposes. This signals the start of a groundbreaking period in neural networks and deep learning that is facilitating the advancement of more complex and effective neural networks, particularly in the context of GAI problems. By the end of 2013, Kingma & Welling (2014, 2019) and Goodfellow et al. (2014) introduced VAEs that are engineered to comprehend the inherent probability distribution within a provided dataset and produce new samples. In 2014, Goodfellow et al. (2014) proposed a deep learning model called GANs, which consist of a pair of adversarial neural network models: a generator and a discriminator. These two models use a competitive process to produce novel synthetic data that yield remarkable outcomes, particularly in image generation and other areas.

Sequence-to-sequence model (Seq2Seq) is introduced by Sutskever, Vinyals & Le (2014) in 2014 to process an input sequence of items, such as words, letters, time series data, or similar. Then, it generates an output sequence of items in response. The model has proven highly effective in various applications such as summarizing text, image captioning, and machine translation (Sutskever et al., 2014). The model uses an encoder to convert the input sequence into a context vector, which the decoder then processes to generate the output, often leveraging RNNs, LSTMs (Salem, 2017), or Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs) (Salem, 2022). In addition, Sohl-Dickstein et al. (2015) proposed diffusion models in 2015, motivated by non-equilibrium thermodynamics. Diffusion models are indeed generative models, serving the purpose of generating data that resembles the training data. The core principle of diffusion models involves generating data by learning to reverse a process that gradually adds noise to training data. Once trained, they can turn random noise into new data that mimics the original dataset. Afterward, Alexander Mordvintsev, a Google engineer, developed a computer vision program called DeepDream. It utilizes a CNN to identify and amplify image patterns through algorithmic pareidolia. This process results in images with a dream-like appearance, resembling a psychedelic experience, due to intentional over-processing.

In September 2015, Gatys, Ecker & Bethge (2015), Mordvintsev, Olah & Tyka (2015) introduced a system employing a deep neural network capable of generating high-quality artistic images. This system leverages neural representations to independently extract and recombine the content and style components from various images. One year later, DeepMind unveiled a raw audio generative model, “Wavenet,” a fully probabilistic autoregressive model (van den Oord et al., 2016). This model creates lifelike artificial voices, often indistinguishable from real speech, and is used in audio processing, music production, and speech synthesis. Google researchers (Vaswani et al., 2017) released a study in 2017 presenting a revolutionary neural network design known as the “"transformer.” This architecture is created in response to RNN constraints when dealing with long texts. Unlike standard RNNs, the transformer does not depend on recurrence but relies only on an attention mechanism to generate global connections between input and output. During the same year, a group comprising AI experts and entrepreneurs from UCL, Stanford, TUM, and Cambridge introduce a platform called Synthesia that specializes in utilizing AI and deep learning technology to create synthetic media content (Synthesia). Its primary focus is delivering realistic and customized movies utilizing computer-generated avatars that can lip-sync to any audio file.

Based on the transformer design, OpenAI, an AI vendor, released the first edition of its language model, Generative Pre-trained Transformer 1 (GPT-1), in June 2018 (Radford et al., 2018). With 117 million parameters, GPT-1 can generate coherent text and answer questions due to its training on diverse internet content. However, its smaller size and limited training data make it struggle with maintaining context in long conversations, sometimes leading to responses that sound convincing but lack logical depth. Shortly after GPT-1, Google introduced Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) in November 2018, a model designed to improve language understanding using a bidirectional transformer architecture (Devlin et al., 2019). It learns from both preceding and following words in a sentence, enhancing contextual understanding and improving Google Search. However, BERT struggles with processing long texts due to its fixed input size and has difficulty capturing long-term word relationships.

Late in 2018, Nvidia researchers introduced StyleGAN, a type of GAN for producing realistic and diverse high-resolution synthetic images of human faces (Karras, Laine & Aila, 2021). A few months later, in early 2019, GPT-2 emerged as a more powerful successor to GPT-1, with 1.5 billion parameters, improving coherence, context retention, and creative writing (Radford et al., 2019). Although effective with short texts, it struggles with longer passages due to its limited context window, which restricts how much text it can process at once. In March 2019, Baidu introduced Enhanced Representation through kNowledge IntEgration (ERNIE 1.0), an Natural Language Processing (NLP) model designed to enhance language understanding through knowledge integration (Sun et al., 2019). Using advanced techniques like entity and phrase-level masking, it learns more complex language patterns, achieving exceptional results in Chinese NLP tasks like sentiment analysis, question answering, and language inference. While it primarily focuses on Chinese NLP, its effectiveness is limited for other languages. One month later, OpenAI introduces MuseNet, a powerful AI that creates music by blending styles from country to Mozart to the Beatles (OpenAI, 2019). Using a large transformer model, it predicts the next note in a sequence, allowing it to compose multi-instrument pieces with remarkable versatility. Nonetheless, it lacks real-time interaction, fine-grained control, and sometimes produces inconsistent results when mixing styles, due to its reliance on statistical pattern prediction rather than true musical understanding. A few months later, in July 2019, Baidu introduced ERNIE 2.0, an upgraded NLP model with continuous pre-training and multi-task learning (Sun et al., 2020). Unlike its predecessor, it learns gradually across multiple tasks, allowing it to better understand vocabulary, syntax, and semantics. This advanced approach helps ERNIE 2.0 outperform BERT, particularly in Chinese language processing. While ERNIE 2.0 excels in language understanding, especially in Chinese NLP, it still struggles with long texts due to its fixed context window, limiting its ability to process extended passages effectively.

2020 to 2022

Introduced in June 2020, GPT-3 marks a major leap in GAI with 175 billion parameters, enabling impressive generalization through few-shot and zero-shot learning (Brown et al., 2020). It excels at tasks like translation, summarization, and coding but can sometimes produce biased, incorrect, or irrelevant outputs due to limitations in its training data and context recognition. In September 2020, researchers from Meta AI introduced Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) technique, which enhances the capabilities of LLMs by integrating external data retrieval processes (Lewis et al., 2020). This approach allows LLMs to access up-to-date information from various sources, improving the accuracy and reliability of generated responses by grounding them in real-world data. At the start of 2021, OpenAI developed and initially released DALL-E to generate images from textual descriptions by adapting the text-generation abilities of GPT-3 to handle both text and image combinations (OpenAI, 2021c). Despite its impressive ability to generate creative and diverse images, DALL·E often struggles with fine details and high-resolution output. Although it demonstrates an understanding of spatial relationships, it occasionally produces distorted or unrealistic compositions. Furthermore, its outputs may inadvertently reflect biases present in the training data. In mid-2021, Google introduced Language Model for Dialogue Applications (LaMDA) (Thoppilan et al., 2022), a language model designed for more natural and coherent conversations. Unlike traditional models, it focuses on improving context and logical flow, making it ideal for chatbots, virtual assistants, and customer support. LaMDA excels in conversational AI but has limitations, including difficulty retaining long-term context, potential biases in responses, and occasional inaccuracies due to outdated or incomplete training data. Released in July 2021, ERNIE 3.0 advances NLP with a 10-billion-parameter architecture that merges auto-regressive and auto-encoding networks. This design enhances both language understanding and generation, setting new benchmarks in Chinese NLP tasks (Wang et al., 2021).

For code generation, OpenAI developed Codex, an AI model based on GPT-3, to generate code from text descriptions (Chen et al., 2021). It learns from public datasets, including GitHub, and powers GitHub Copilot in October 2021, which helps developers with code suggestions and automation (GitHub Copilot, 2021). OpenAI restricts access in March 2023 due to misuse concerns but later allows researchers to use it under a controlled program. Shortly after, in November 2021, Microsoft proposed a comprehensive multimodal pre-trained model, known as Neural visUal World creAtion (NUWA) (Wu et al., 2022). This model can produce novel or modify existing visual data for various visual synthesis applications, including images and videos. Although NUWA is capable of generating both images and videos, it faces notable limitations. It often struggles to produce highly detailed or contextually rich visuals, particularly in scenarios that require deep semantic understanding. Building on the progress of earlier models of GPT, OpenAI introduce GPT-3.5 in January 2022 as an evolution of GPT-3. This version includes three variants, each with different parameter sizes: 1.3 billion, 6 billion, and 175 billion. Commonly referred to as InstructGPT, it shares similar training data with GPT-3 but incorporates an important advancement through fine-tuning using Reinforcement Learning with Human Feedback (RLHF) (Christiano et al., 2017) This method enhances the model’s ability to follow user instructions, reduces harmful biases, and improves the overall quality of responses. Nonetheless, GPT-3.5 still faces certain limitations, including occasional factual inaccuracies, inconsistencies, and difficulty maintaining coherence in extended conversations.

MidJourney, developed by an independent research lab in San Francisco, is an AI tool that generates images from text prompts. The model performs well in artistic image generation but has limitations in detail control, object placement, and text rendering, with full access restricted to paid Discord users. In April 2022, Google announced PaLM (Pathways Language Model), a powerful transformer-based language model with 540 billion parameters (Chowdhery et al., 2022). It remains confidential until March 2023, when Google releases its API. Unlike LaMDA, which specializes in conversations, and BERT, which focuses on understanding text, PaLM combines reasoning, coding, and language skills, making it more versatile. However, its massive size makes it expensive to run, and it still struggles with accuracy and maintaining context in long conversations (Narang & Chowdhery, 2022). Later in April, Boris Dayma created Craiyon, a free AI tool for text-to-image generation. It evolves with community contributions and internal improvements (Craiyon, 2022). Originally called DALL-E mini, it was renamed after OpenAI raised concerns about its similarity to their DALL-E model. While Craiyon stands out for its ease of access and open availability, it typically produces lower-quality images compared to other state-of-the-art generators. Around the same time, in April 2022, OpenAI releases DALL-E 2, a text-to-image model built on Contrastive Language-Image Pretraining (CLIP) and a diffusion model (OpenAI, 2021a; Radford et al., 2021). It generates highly realistic images and improves resolution compared to its predecessor, DALL-E (OpenAI, 2022).

In May 2022, Meta AI Research introduced Open Pre-trained Transformer (OPT-175B), a 175-billion-parameter language model trained on 180 billion tokens (Zhang et al., 2022). It matches GPT-3 in performance but is more energy-efficient, using only one-seventh of GPT-3’s training carbon footprint. Despite its technical strengths, the model, like many LLMs, continues to face limitations, particularly concerning biases and factual inaccuracies. In a commitment to advancing transparent and responsible AI research, Meta releases the model’s code, pre-trained weights, and comprehensive training logs. However, its distribution is restricted by a non-commercial license, making it available primarily to researchers in academic institutions, government agencies, and civil society organizations. During the same month, the Knowledge Engineering Group (KEG) and data mining THUDM at Tsinghua University presented a large-scale pre-trained text-to-video generation model, named CogVideo. CogVideo is built upon the transformer architecture to create videos based on text descriptions in the Chinese language and offers compatibility with various video formats (Hong et al., 2022). Also, in May, Google introduces Imagen, a text-to-image diffusion model built on Text-To-Text Transfer Transformer (T5) for text encoding and a cascaded diffusion process for image synthesis. It joins AI-driven generators like DALL-E 2, focusing on photorealism and producing sharper, more lifelike images (Saharia et al., 2022). While Imagen delivers high realism and precise text alignment, DALL·E 2 offers greater creative flexibility and advanced editing features like inpainting.

In June 2022, Microsoft released Phi 1 as its first LLM. It is a Transformer-based architecture with 1.3 billion parameters, specifically designed for basic Python coding tasks (Microsoft Azure, 2024). Despite being efficient for basic Python coding, Phi-1’s small size limits its ability to handle complex tasks and broader language understanding. One month later, Hugging Face and BigScience introduced Bigscience Large Open-science Open-access multilingual language Model (BLOOM) as an open-source alternative to GPT-3 (Scao et al., 2022). BLOOM has 176 billion parameters and is trained on the ROOTS corpus, supporting 46 natural and 13 programming languages with a strong emphasis on linguistic diversity. Compared to GPT-3, it offers full transparency under the Responsible AI License (RAIL), ensuring ethical use. Despite its open nature, BLOOM demands significant computational resources, struggles with biases and maintaining long-term coherence, and, due to its accessibility, carries the risk of misuse.

In August 2022, Stable Diffusion emerges as a powerful text-to-image AI model based on diffusion techniques (Stability AI, 2022; Scao et al., 2022). Developed by researchers from the CompVis Group at Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich and Runway, with funding from Stability AI, it specializes in generating highly detailed images from text prompts. Beyond text-to-image generation, it also supports image-to-image translation and inpainting, allowing users to modify or enhance images based on descriptions. While Stable Diffusion is highly effective at generating detailed and customizable images, it still requires significant computing power, struggles with generating text within images, and sometimes produces biased or inconsistent results. Following this, in September 2022, Nvidia introduced GET3D, a generative model built on GAN-based architectures to create high-quality 3D textured models from images (Gao et al., 2022). It specializes in producing detailed 3D representations of characters, buildings, vehicles, and other objects with impressive textures and intricate geometric details. Although GET3D generates high-quality 3D models, it requires large datasets, struggles with complex objects, and demands high computing power. In the same month, Meta AI introduced Make-A-Video, a GAI model based on diffusion techniques and transformer architectures (Singer et al., 2022). It creates short videos from text prompts, making it useful for animation, music videos, and short films. While it enables creative content generation, it struggles with fine details, consistency between frames, and realistic motion, often requiring post-processing to improve quality. Expanding the wave of innovation, Google AI launched Imagen Video the following month, a text-to-video model that leverages a cascade of diffusion models to generate high-quality video content from textual descriptions. It supports various artistic styles and 3D object understanding but struggles with artifacts in complex scenes and motion consistency (Google, 2022; Ho et al., 2022). By November 2022, the focus turned toward conversational AI with OpenAI’s release of ChatGPT, built on the GPT-3.5 architecture. The model attracted widespread interest for its ability to generate coherent, context-aware, and human-like dialogue (OpenAI, 2023c).

2023

In early 2023, Runway Company released its video generation model, Gen-1, to produce novel videos based on pre-existing ones (runway, 2023a). The Gen-1 can modify videos using visual or textual descriptions, enabling users to generate novel films without physically filming or editing them. However, it comes with challenges like heavy computing requirements, and occasional inconsistencies in quality. Around the same time, Meta AI introduced LLaMA 1, a more efficient Transformer-based language model available in 7B to 65B parameters. LLaMA delivers strong performance with fewer resources, making it more accessible for researchers compared to OPT. Nevertheless, it remains restricted for commercial use and still faces bias and accuracy challenges (Meta AI, 2023; Touvron et al., 2023). By March, Runway released Gen-2, an enhanced version of Gen-1 that allows users to generate short videos from text prompts or animate images (runway, 2023b). This upgrade improves realism and creative flexibility, making it easier to bring ideas to life. Gen-2 also offers real-time feedback and versatile input options, whether through language instructions or uploaded visuals. Despite its strengths, it still demands high computational power and struggles to maintain consistency in longer video clips. In March, Google introduces Bard (Bard, 2023), an AI chatbot that assists users by answering questions and generating ideas in a conversational way. Initially built on LaMDA, Bard later transitions to more advanced AI models, eventually being rebranded as Gemini. While it provides helpful insights and creative support, it sometimes struggles with accuracy, biases, and complex reasoning (Google, 2023). During the same month, OpenAI launched GPT-4, the latest in its GPT series, offering improved reasoning, creativity, and contextual understanding over GPT-3.5 (OpenAI, 2023b; OpenAI, 2023d). A key upgrade is its multimodal capability, allowing it to process both text and images. GPT-4, available via ChatGPT Plus and OpenAI’s API, delivers more accurate and coherent responses than earlier versions. While it still encounters issues like bias, occasional errors, and high computational demands, it remains one of the most advanced AI models, excelling in complex tasks and nuanced dialogue. Around the same time, Anthropic, an AI startup company, introduces Claude AI, a chatbot built on the Claude 1.3 language model using a Transformer-based architecture. Claude performs well in text generation, translation, summarization, and question answering, while emphasizing ethical alignment and user safety. It also prioritizes transparency and reducing harmful outputs. Still, it has limitations, including occasional inaccuracies and difficulty with complex reasoning (Anthropic, 2023b; Card, 2023).

In May, the Technology Innovation Institute (TII) in Abu Dhabi created its first LLM called Falcon under the Apache 2.0 license (Falcon LLM & Technology Innovation Institute (TII), 2023). Falcon is an open source with 40 billion parameters, updated later to 180 billion and is considered a strong alternative for developers looking for an open-source and customizable LLM. However, compared to other LLMs released around the same time, it cannot process images, struggles with complex reasoning, and may need more fine-tuning for specific tasks. It also has challenges with long conversations and inherited biases. During this period, IBM unveiled Watsonx.ai to help businesses develop and scale GAI (IBM Newsroom, 2023). The platform supports multiple LLMs, including Hugging Face models, Meta’s LLaMA 2, and IBM’s Granite models (IBM Research, 2023), introduced later in September 2023. It offers flexible AI tools for various applications. Meanwhile, in the same month, Google DeepMind built PaLM 2, a sophisticated LLM (Google AI, 2023). PaLM 2 is built on a Transformer-based architecture, leveraging Google’s Pathways system for efficient training and scaling. It improves multilingual understanding, reasoning, and code production over PaLM. Google Bard uses it to improve conversational skills and language understanding, making it a key AI service in 2023 (Anil et al., 2023). In the following month, Baidu launched ERNIE 3.5, an upgraded version of ERNIE 3, powering the ERNIE Bot chatbot (Baidu Research, 2023). ERNIE 3.5 responds much faster, at 17 times the efficiency of its predecessor, and supports plugins like Baidu Search and ChatFile, making it a more versatile and practical AI assistant.

In July, Anthropic launched Claude 2, an upgraded version of its AI model with enhanced reasoning, problem-solving, and contextual understanding (Anthropic, 2023a). Compared to its predecessor, Claude 2 features a larger context window, improved memory retention, and better handling of complex queries. It also refines its alignment techniques to reduce biases and enhance safety, making responses more reliable. Around the same time, Meta, in collaboration with Microsoft, released LLaMA-2, an improved version of its language model with 7, 13, and 70 billion parameters. While its architecture remains similar to LLaMA-1, it benefits from a larger training dataset, enhancing its overall performance. In the next month, OpenAI introduces DALL-E 3, an upgraded version of DALL-E 2. It offers a better understanding of detailed prompts, allowing users to create more accurate and visually precise images with ease (OpenAI, 2023a). On September 27, Mistral AI, a French startup, released its first model, Mistral 7B—a compact 7-billion-parameter LLM optimized for speed and efficiency. Despite its smaller size, it offers strong performance and cost-effectiveness, though it may fall short on complex reasoning and long-context tasks compared to larger models (Jiang et al., 2023). In the next month, Google DeepMind introduced Imagen 3, the most advanced version of its text-to-image model. This model provides exceptional image quality, with substantially fewer distracting artifacts, richer lighting, and enhanced detail than previous models (Google DeepMind, 2024a). Later, on October 15, 2024, the model becomes available to users in the United States. On October 17, Baidu introduced ERNIE 4.0, a more advanced model offering improved language understanding, reasoning, and memory, with performance reportedly 30% stronger than ERNIE 3.5. It supports text, image, and video generation, and delivers more direct, context-aware responses. While well-integrated into Baidu’s ecosystem, access remains limited to invited users in China, leaving its global impact yet to be seen (Originality.ai, 2025). On November 4, Elon Musk’s company, xAI, launched Grok, an AI chatbot. Initially tested with a small group of users, Grok is designed to process real-time global information from Twitter’s X platform (X AI, 2023). It can generate poetry, code, screenplays, music, emails, and more. While innovative, Grok has faced criticism for occasional unpredictability, sometimes providing rude or inappropriate responses as it continues to develop.

Later, on November 16, Google DeepMind, in partnership with YouTube, introduces Lyria, an advanced AI music model designed to generate creative and original compositions XAI Grok (X AI, 2023). It offers better control over musical structure and style compared to OpenAI’s MuseNet, making it more suited for professional music creation. However, it still faces challenges in capturing emotional depth and maintaining coherence in longer compositions (Google DeepMind, 2023). Five days later, Stability AI’s Stable Video Diffusion allowed developers to generate short video clips, typically between 2 to 5 s, with frame rates up to 30 FPS (Stability AI, 2023). While it efficiently generates frames, it struggles with longer sequences, photorealism, and maintaining smooth motion. However, its easy accessibility through Stability AI’s platform makes it a useful tool for AI-driven video experimentation. On November 28, Pika launched its AI video generation platform, founded by Stanford researchers Demi Guo and Chenlin Meng. The platform allows users to create videos from text prompts, supporting various styles like 3D animation and cinematic effects. It offers real-time editing and clip extension features. While Pika is easy to use and popular, it struggles with producing high-quality, professional (Pika, 2023). In early December, Google DeepMind introduced Gemini, a powerful multimodal AI model capable of processing text, images, audio, and video. With enhanced reasoning, coding, and contextual understanding, it marks a significant step beyond previous Google models. It comes in three versions: Ultra, Pro, and Nano, each suited to different use cases. Despite its strengths, Gemini still requires substantial computational resources and can struggle with complex reasoning. On 11 December, Mistral AI launches La Plateforme, its beta platform for developers. It offers powerful open generative models with easy deployment and customization options (Mistral AI, 2023). The platform includes three conversation endpoints, two for text generation and one for embedding, each balancing cost and performance differently. This gives users flexibility based on their needs. Later in December, Microsoft introduces Phi-2, a 2.7 billion-parameter model trained on synthetic data. Designed for research, it excels in reasoning and language tasks while reducing bias and toxicity. Despite its smaller size, it outperforms larger models in some benchmarks but struggles with complex tasks. Fine-tuning may be needed for specialized applications (Microsoft Research, 2023).

2024

In early 2024, NVIDIA launched Chat with RTX, a local AI chatbot for Windows PCs. It offers better privacy and control than cloud-based models but depends on hardware capabilities and lacks scalability (NVIDIA, 2025). On 21 February, Google DeepMind On February 21, Google launched Gemma, a lightweight open-source AI model for developers and researchers. Supporting over 140 languages, it balances efficiency and accessibility. While PaLM and Gemini are more powerful, they require more resources. Gemma’s customizability makes it a valuable tool for flexible AI applications (Google AI for Developers, 2023). Three days later, OpenAI introduced Sora, a powerful text-to-video model that blends diffusion and transformer-based architecture, similar to GPT. It creates high-quality, up to 20-second-long videos with impressive motion and scene complexity. Sora refines user prompts using GPT-based recaptioning, ensuring greater accuracy in video generation. While it surpasses models like Runway’s Gen-2 and Stable Video Diffusion in realism, it still faces challenges with physics accuracy and object interactions. Sora is accessible only to select professionals for safety testing, with plans for broader availability in the future (OpenAI, 2024b).

On February 26, Mistral AI launched Mistral Large, its most advanced language model, designed for complex reasoning tasks like code generation, text transformation, and analysis. Alongside it, Mistral AI introduced Le Chat, a conversational assistant that allows users to choose between Mistral Large, Mistral Small, or Mistral Next for more concise responses. Le Chat features customizable moderation, providing non-intrusive alerts for sensitive or controversial content. While Mistral Large excels in precision and adaptability, it may require fine-tuning for highly specialized tasks and faces competition from larger proprietary models (Mistral AI, 2024). On April 23, Microsoft launched Phi-3, a 3.8 billion-parameter model with a dense decoder-only Transformer design. It supports a 128,000-token context window, enabling it to handle complex language tasks while competing with larger models like GPT-3.5 (Abdin et al., 2024). Later in August, Microsoft released Phi-3.5, introducing three variants: mini-instruct for fast reasoning, MoE with a 42-billion-parameter Mixture-of-Experts architecture that activates only 6.6 billion parameters per use, and vision-instruct for multimodal text and image tasks. The Phi-3 series advances AI efficiency, maintaining high performance, safety, and scalability in resource-constrained environments Phi-3.5 SLMs (Trufinescu, 2024).

Figure 3 presents a timeline showcasing the development stages of GAI, and the following sections introduce further details regarding GAI models, tools, applications, challenges, and ethical implications.

Figure 3: GAI timeline.

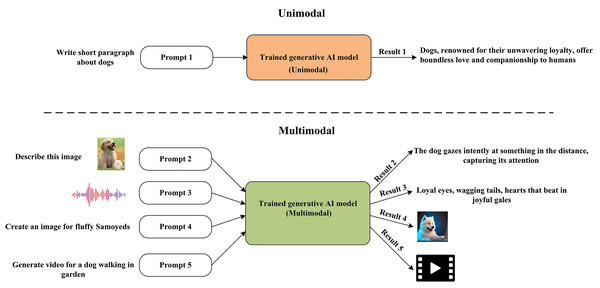

Generative AI models

The field of GAI comprises a range of models designed to produce novel data or content that closely mimics human-generated data. Multimodal and unimodal models are two distinct categories of GAI models that process input data in various formats. Unimodal GAI models have been developed to process information in one data format, usually text. These models are designed to process a text prompt and provide text-based replies. Unimodal GAI models have proven effective in various domains, including text generation as GPT3 and language translation. Unimodal GAI models may not be the best choice for activities requiring processing other sorts of data, such as photos or audio. Multimodal GAI models are more suited for these kinds of tasks. Multimodal models can simultaneously process diverse input data, including text, image, audio, or a fusion of these modalities. OpenAI’s CLIP, DALL-E, and GPT-4 are examples of Multimodal models. Figure 4 presents and summarizes the difference between the GAI model types.

Figure 4: GAI model types.

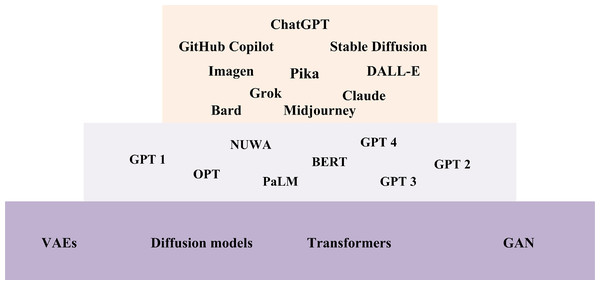

Furthermore, Fig. 5 presents the landscape of LLMs and their foundational technologies which showcases the rapid advancements in AI and natural language processing. This landscape illustrates the diverse range of models and techniques that have emerged, reflecting the innovative approaches driving the field forward. At the top of this landscape, ChatGPT ranks among the prominent models, joined by other noteworthy examples such as GitHub Copilot, Stable Diffusion, Imagen, Pika, and DALL-E, etc. These models are built on state-of-the-art techniques, including VAEs, diffusion models, transformers, and GANs, etc. The middle layer highlights various LLMs, including GPT-1, 2, 3, and 4, along with OPT, PaLM, NUWA, BERT, and Claude. These models, developed over time, have significantly contributed to the evolution of AI and natural language processing. The following subsections provide an overview of the cutting-edge techniques that serve as the foundation for developing these advanced tools.

Figure 5: LLMs and their foundational technologies landscape.

Generative adversarial networks

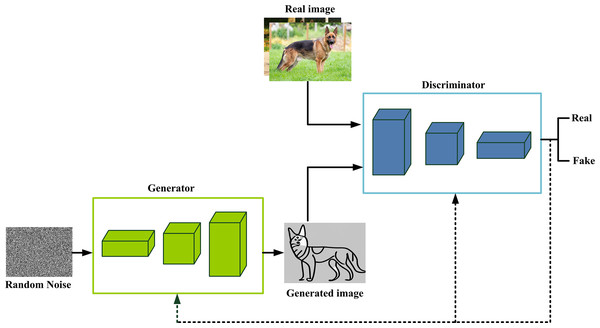

GANs are first introduced in 2014 by Ian Goodfellow and his colleagues (Zhong et al., 2023). GANs are a prominent category of generative techniques that have gained significant traction in AI, especially in image, video, and data generation (Isola et al., 2017). GANs consist of two deep neural network models: a discriminator and a generator, as shown in Fig. 6. The generator is a CNN, and its function is to generate fake data that looks like real data. Contrarily, the discriminator is a CNN, and its function is a binary classifier. It attempts to differentiate between real data and created data from the generator. The adversarial aspect of GANs is rooted in a game theoretic framework, whereby the generator network engages in a competitive interaction with the opponent. The generator network is responsible for generating fake data. The discriminator network, which opposes it, differentiates data originating from the generator and those originating from the training data. This process fosters an ongoing competitive dynamic, wherein the update of one network upon failure occurs while the other network remains unaffected, embodying an iterative refinement characteristic of GAN architectures.

Figure 6: GANs architecture.

GAN training occurs in alternating phases. First, the discriminator is trained for a set number of epochs. Subsequently, the generator is trained for a defined number of epochs. This sequence iterates, cycling between training the discriminator and the generator networks, enabling continual refinement of both networks. During the training phase of the discriminator, the generator remains frozen. Conversely, when the generator is trained, the discriminator remains constant and unaltered. The generator is provided with a loss signal through feedback from the discriminator. This loss signal indicates the discriminator’s proficiency in discerning genuine data from artificially created data. By minimizing this loss, the generator can produce data that exhibits a progressively higher similarity to the actual data. Numerous GAI tools and frameworks have been developed utilizing the principles of GANs, such as DALL-E, DeepAI, and Pix2Pix (Arora, Risteski & Zhang, 2017). Despite GANs strengths, it often struggles with mode collapse, where the generator repeatedly produces similar outputs instead of diverse ones. Training can also be unstable, especially if the discriminator learns too fast, making it harder for the generator to improve. Additionally, GANs are highly sensitive to hyperparameters, meaning small changes in learning rate or batch size can greatly affect performance (Arora, Risteski & Zhang, 2017; Saxena & Cao, 2020; Bengesi et al., 2024).

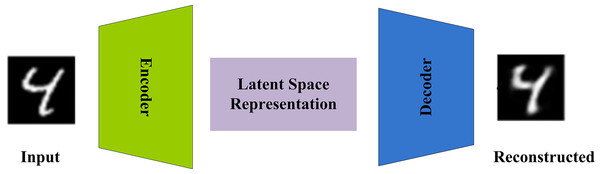

Variational autoencoders

VAEs, or variational autoencoders, are a subclass of generative models that can identify latent data representations (Yacoby, Pan & Doshi-Velez, 2020). VAEs comprise two distinct neural networks, an encoder, and a decoder, as shown in Fig. 7. The data sample is fed to the encoder for encoding. After that, it produces a latent representation for this data, which refers to a numerical vector that effectively encodes the fundamental characteristics of the data. The decoder rebuilds the original input data using this latent representation. VAEs are used to grasp the inherent probability distribution within a dataset, enabling the generation of new data samples that adhere to that distribution. An encoder-decoder architecture is employed, wherein the encoder transforms input data into a latent representation, and the decoder endeavors to reconstruct the initial data from this encoded representation. During training, the VAE’s objective is to become skilled at modeling the data’s underlying distribution and generating new samples that conform to it. This is achieved by minimizing the dissimilarity between the original and reconstructed data. Through this training process, the VAE can understand the inherent data distribution. When training VAEs, a variational objective function is employed, consisting of two key loss components: the reconstruction loss and the Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence. The reconstruction loss assesses the decoder’s ability to faithfully recreate the original input data, serving as a performance measure for the decoder.

Figure 7: VAEs architecture.

On the other hand, the KL divergence quantifies how far the latent representation deviates from a standard normal distribution. The primary goal during VAE training is to minimize the variational objective function using techniques like gradient descent. This minimization process empowers the encoder to generate informative yet concise latent representations. Simultaneously, the decoder learns the knowledge needed to reconstruct the initial input data from these latent representations accurately. The overarching aim is to make the VAE adept at representation and reconstruction tasks, resulting in a more effective generative model. VAEs find applications across a broad spectrum. They are frequently harnessed for generating images, as they enable the generation of new and unique images through latent space sampling. In addition, VAEs serve various purposes, including data compression, anomaly detection, and data imputation. Numerous GAI tools leverage VAEs as a fundamental element. Here are some prominent tools that incorporate VAEs for diverse generative purposes: DeepArt.io (DeepArt.io, 2015), DCGAN (Radford, Metz & Chintala, 2015), DreamStudio (DreamStudio, 2022) and Pix2Pix (Tahmid et al., 2016). Although VAEs offer stable training and can generate new data, their outputs often appear blurry due to difficulties in capturing fine details. They struggle with high-resolution images and complex data patterns, making them less effective for photorealistic generation. Their latent space is hard to interpret, limiting control over outputs. These challenges make VAEs less suitable for tasks requiring high-detail or sharp images (Yacoby, Pan & Doshi-Velez, 2020; Daunhawer et al., 2021).

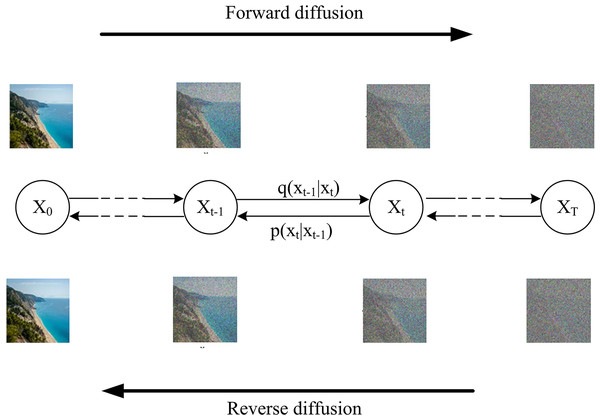

Diffusion model

Diffusion models, as generative models, have seen a considerable increase in popularity in recent years over GAN and VAEs. GANs demonstrate excellent performance across various applications. Nevertheless, their training process poses challenges, leading to limited diversity in generated outputs due to issues like mode collapse and vanishing gradients (Saxena & Cao, 2020). On the other hand, constructing an effective loss function for VAEs remains a hurdle, resulting in suboptimal outputs. Diffusion models are predicated on the thermodynamics of gas molecules, which states that molecules diffuse from regions of high density to those of low density (Sohl-Dickstein et al., 2015; Chang, Koulieris & Shum, 2023). In the theory of information, this corresponds to information loss caused by the incremental introduction of noise. Fundamentally, Diffusion Models function by perturbing training data iteratively by adding Gaussian noise, subsequently learning to reconstruct the original data by reversing this noise-induced transformation. Post-training, the Diffusion Model becomes capable of generating data by passing randomly sampled noise through the acquired knowledge of the denoising procedure. The Diffusion Model, in its essence, operates as a latent variable model employing a fixed Markov chain to traverse the latent space. This stationary chain systematically introduces incremental noise to the data to approximate the posterior distribution, as shown in Fig. 8. Ultimately, the image undergoes an asymptotic transformation into pure Gaussian noise. The primary goal of training a diffusion model is to learn the inverse process, which enables the generation of new data by moving backward through the chain. As a result, diffusion models excel in GAI by creating and manipulating high-quality images. Many tools, such as DALL-E 2, Imagen, DreamStudio (DreamStudio, 2022), Artbreeder (Artbreeder, 2025), and GauGAN2 (NVIDIA, 2021), leverage diffusion models to offer a wide range of applications, including text-to-image and image editing. Unlike GANs, diffusion models provide stable training, avoiding instability and the blurry outputs of VAEs. However, while diffusion models produce realistic and detailed images, they tend to be slower than GANs. Nevertheless, advancements continue to improve their efficiency. Despite these improvements, they still require high computational power, making them resource-intensive for both training and inference (Chen et al., 2024).

Figure 8: Diffusion model process.

Transformer-based models

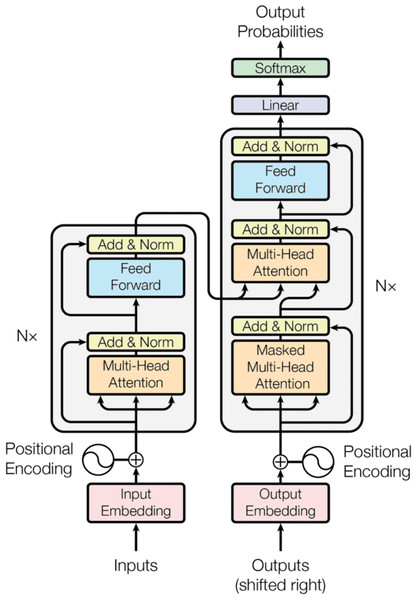

A transformer is a novel neural network introduced in 2017 that utilizes the parallel multi-head attention mechanism (Vaswani et al., 2017). The transformer is used to convert one sequence into another. However, it distinguishes itself from conventional Seq2Seq models by not relying on Recurrent Networks such as GRU or LSTM. Because RNNs have a smaller reference window, they cannot access words generated earlier in the sequence as stories get longer. Even though GRU and LSTM have a greater capacity to achieve longer-term memory and, consequently, a longer window to reference from, they still face the issue of accessing words generated before. The strength of the attention mechanism of the transformer lies in its lack of short-term memory problems. The attention mechanism can reference an unlimited information window with sufficient computational resources. This allows it to utilize the entire context of the story when generating text.

The transformer structure consists of an encoder and Decoder, as presented in Fig. 9. Encoder and Decoder are modules that may be layered on each other several times, as shown in the figure by Nx. The encoder’s role, situated on the left side of the Transformer architecture, is to convert an input sequence into a series of continuous representations. These representations are subsequently sent to the Decoder. The Decoder, located on the right side of the architecture, takes in the output of the encoder and the preceding time step’s decoder output to produce an output sequence. Initially, the input is sent through a word embedding layer. A word embedding layer may be conceptualized as a retrieval table that retrieves a learned vector representation for each word. Due to the absence of recurrence in the transformer encoder, positional information must be incorporated into the input embeddings. Thus, Positional encoding is utilized by employing sine and cosine functions. Now, the input embeddings with their positions are fed to the encoder, which has two sub-modules: multi-headed attention and a fully connected network. In addition, residual connections surround each of the two sublayers, which are then followed by a normalization layer. The Multi-headed attention is a component within the transformer network that calculates the attention weights for the input and generates an output vector containing encoded information on how each word should prioritize its attention toward all other words in the sequence. Consequently, the feedforward layer transforms the attention outputs, potentially enhancing their representation. The Decoder is autoregressive, commencing with a start token and accepting a sequence of prior outputs as inputs, in addition to the encoder outputs that encompass the attention information derived from the input. The decoding process terminates when a token is produced as an output. Transformers pave the way for powerful models like BERT, GPT series, T5 (Raffel et al., 2020) and PaLM, revolutionizing NLP. Though initially limited in high-fidelity image and video generation, newer models integrate Transformer elements to enhance performance. However, they demand high computational power, particularly for long sequences, though later optimizations help improve efficiency (Fan et al., 2020).

Figure 9: Transformer architecture.

Comparing GANs, VAEs, diffusion models, and transformers

Different AI models perform better in specific tasks based on their strengths and limitations. GANs create realistic images and are great for style transfer, but they often face training instability and mode collapse, limiting diversity in their outputs (Bengesi et al., 2024). VAEs offer stable training and are useful for anomaly detection and data compression, though their images can be blurry. Diffusion Models generate highly detailed content, especially in text-to-image tasks, but they are slower and computationally demanding. Transformers, known for natural language processing, are now advancing in computer vision, but they require large datasets and high computing power. Table 1 provides a good overview of the key characteristics and limitations of GANs, VAEs, Diffusion Models, and Transformers.

| Model | Architecture | Performance | Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GANs | Generator + Discriminator | High-quality but unstable | Image generation, style transfer | Mode collapse, unstable training, high computational costs, ethical issues (e.g., deepfakes) |

| VAEs | Encoder + Decoder (Latent Space) | Stable training, but blurry outputs | Anomaly detection, image compression | Less sharp images, not fully generative, struggles with fine details, suboptimal for complex datasets |

| Diffusion models | Noising + Denoising process | High-quality and stable outputs | Image generation, video synthesis | Slow generation, high computational cost, limited understanding of conditional diffusion models |

| Transformers | Encoder–Decoder (NLP), Vision transformers | Excellent long-range understanding | NLP, computer vision, bioinformatics | Resource-heavy, struggles with long-range dependencies, overfitting on small datasets, lacks recursive computation for hierarchical structures |

GAI tools

Recently, numerous companies and startups have developed software frameworks and platforms that leverage foundational GAI models to generate text, speech, images, video, music, code, and scientific content. Since the rise of ChatGPT, the development of GAI tools has surged, expanding beyond research into everyday use and commercial applications. Businesses and individuals are increasingly adopting these tools to boost productivity and streamline workflows. Table 2 offers a comprehensive overview of a wide range of GAI tools, as identified by the author at the time of writing. This includes well-known language models like ChatGPT (OpenAI, 2023c), ChatGPT-4o (OpenAI, 2024a), Claude (Anthropic, 2023a), Gemini (Bard, 2023; Google, 2023), Grok 3 (X AI, 2023), DeepSeek (DeepSeek, 2023), and Google NotebookLM (Google, 2023), along with research- and productivity-focused platforms such as Perplexity (Perplexity.ai, 2022), Microsoft Copilot (Microsoft Copilot, 2023), Copilot (Microsoft Copilot, 2023), Cohere (Cohere, 2022), and Bardeen.ai (Bardeen AI, 2025). Tools designed for code generation, such as GitHub Copilot (GitHub Copilot, 2021) and AlphaCode (DeepMind, 2022), are also included.

| Tools | Comp. | In. | Out. | Models | Cost | Datasets | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChatGPT (2021) | OpenAI | T,S,C | T,C | GPT-3.5 | Free | Web text | Limited reasoning, no multimodal |

| ChatGPT-4o (2022) | OpenAI | T,I,S,C,D | T,I,F,C | GPT-4, DALL-E 3 | subscr. | Large web corpus | Weak long-context coherence |

| Gemini (2024), Bard (2023) | Google DeepMind | T,I,A,V,C,D | T,I | Gemini 1.5 + Imagen 3 | Free | Multimodal & multilingual | Not as creative as GPT-4o, limited multimodal |

| Grok 3 (2025) | xAI | T,I,D | T,I,C | Proprietary transformer, DeepSearch + Think Mode | subscr. | Real-time, legal, diverse data X | Costly, X data bias risk. |

| DeepSeek (2025) | DeepSeek | T,I,D | T,C | MoE w/DeepThink | Free | Hybrid datasets | Security/reliability issues, poor integration |

| Google NotebookLM (2025) | T,D | T | Proprietary | Free | Google Drive & external datasets | Limited to docs, lacks reasoning | |

| Claude (2023) | Anthropic | T | T | Claude | Free tier | Public text sources | Unimodal, strict safety limits use |

| Cohere (2022) | Cohere | T | T | Command Model, Embed | Free tier | Web, books & articles | Smaller, less powerful than GPT |

| Bardeen.ai (2021) | Bardeen | T | T | GPT-3, GPT-4 Turbo | Free tier | APIs, web & user data | Limited deployment, no full autonomy |

| Perplexity (2022) | Perplexity AI | T,I,C,D | T,I,C | GPT-4 Turbo, Claude 3, DALL-E 3, SDXL | Free tier | Internet data | Refining multimodal, research-ready |

| Microsoft Copilot (2025) | Microsoft | T,D | T | GPT-4 + ML | subscr. | Curated M365/D365/Power data | MS-dependent, limited cross-platform |

| Copilot (2021) | GitHub + Microsoft | C | C | Microsoft Bing + GPT-3 | Free tier | Public GitHub repos | Less flexible, limited explanations |

| AlphaCode (2022) | DeepMind | T,C | C | Transformer | subscr. | GitHub, coding platforms | Low efficiency, has scalability issues. |

| GitHub Copilot (2021) | GitHub (Microsoft) | T | C | OpenAI Codex | subscr. | Public code repos | Struggles with multi-step code |

| DALL-E (2021) | OpenAI | T | I | GPT-3 Architecture | Free | Image-text pairs dataset | Limited resolution and accuracy. |

| DALL-E 2 (2022) | OpenAI | T | I | CLIP + Diffusion | subscr. | Millions of image-text pairs | Less detailed/realistic than DALL·E 3 |

| DALL-E 3 (2023) | OpenAI | T | I | ChatGPT + Diffusion | subscr. | Web image-text data | Weak with complex visuals |

| Midjourney (2022) | Midjourney, Inc. | T | I | Proprietary | subscr. | curated datasets | Inconsistent with complex prompts |

| Crayion (2021) | Boris Dayma | T | I | VQGAN + CLIP | Free | Vast internet images | Lower quality, complex prompt issues |

| Stable Diffusion V1 (2021), Stable Diffusion V3 (2024) | Stability AI, CompVis & LAION | T | I | LDM + U-Net + CLIP | Free tier | LAION-5B | Ethical risks, prompt issues, resource-heavy |

| Descript (2017) | Descript | T,V,A | T,V,A | Lyrebird AI + others | Free tier | Text, audio, video files | Accuracy issues, speech overlap challenges |

| Type Studio (2021) | Streamlabs | T,V,A | T,V,A | Speech-to-text, NLP models | Free tier | Audio & transcript data | Less capable than descript |

| Designs AI (2020) | Mediaclip | T,V,I | T,V,I | Proprietary | Free tier | Templates & images data | Less flexible vs. design AIs |

| Soundraw (2021) | Soundraw | Control | M | Proprietary | Free tier | Musical datasets | Less versatile vs. Jukebox |

| Lyria (2023) | Google DeepMind + YouTube | T, M | M | Proprietary | Free | YouTube + other sources | Limited access, Google-only |

| Duet AI (2023) | T,M | T,M,C | Gemini | subscr. | Text, code & Google data | Less reach vs. ChatGPT | |

| Murf AI (2020) | Murf | T,A | A | Proprietary | Free tier | Large speech datasets | Limited Emotional Range |

| Pika (2024) | Pika Labs | T,I | V | Pika 1.5 | Free for 10 vids | Uncited | Video length & motion limits, poor accessibility |

| Imagen Video (2023) | Google DeepMind | T | V | Proprietary | subscr. | curated video data | Resource-heavy, misuse concerns |

| Runway GEN (2024) | Runway | T,I | V | Proprietary | Free tier | diverse video data | Resource-heavy, limited free length |

| Synthesia (2017) | Synthesia AI Research | T,I,V | V | EXPRESS-1 Model | subscr. | Public video/audio/text data | Style/motion only, no multilingual |

In addition to text and code, the table highlights AI tools that work with images and video, including DALL.E Mini (Bayma & Cuenca, 2021), DALL-E (OpenAI, 2021c), DALL-E 2 (OpenAI, 2022), DALL-E 3 (OpenAI, 2023a), Midjourney (Midjourney), Crayion (Craiyon, 2022), Stable Diffusion (Stability AI, 2022), Type Studio (DreamStudio, 2022), Designs.ai (Designs AI, 2019), Runway GEN (Runway Research, 2024), Pika (Pika, 2023), Descript (Descript, 2017), Synthesia (Synthesia, 2023), and Imagen Video (Google, 2022). For audio and music generation, tools like Soundraw (SOUNDRAW, 2021), Lyria (Google DeepMind, 2024b), and Murf.ai (Murf AI, 2020) are featured. Each tool is summarized in terms of its release date, underlying model, affiliated company, estimated usage cost, and key limitations. These tools differ in how they take input and generate output, with applications that span from chat-based assistants and code-writing companions to fully multimodal systems capable of handling text, image, video, and audio. Together, they reflect the diversity and rapid evolution of GAI technologies.

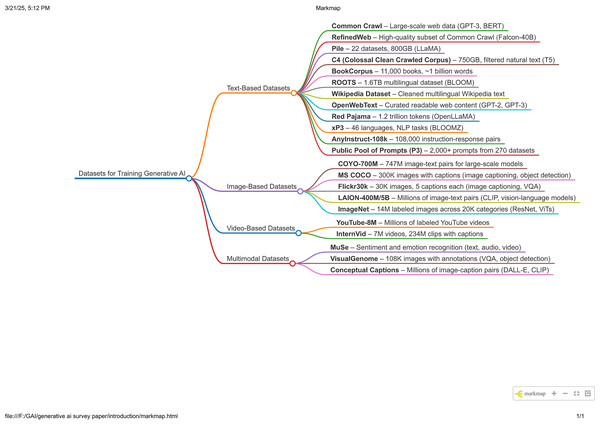

Datasets

The datasets used for training GAI are typically vast and diverse, encompassing a wide range of text, image, and video sources to capture linguistic patterns, visual details, and knowledge across various domains. The datasets used to train unimodal LLM often include text from books, websites, research articles, social media, and other publicly available content, ensuring a rich and varied input. For multimodal LLMs, additional datasets consisting of labeled images, captions, video content, and other visual data are incorporated to train the model, enabling it to generate and understand both text, images, and video. This combination helps the model interpret and produce information across multiple modalities. The details of some of these datasets are introduced as follows. A graph summarizing these datasets is provided in Fig. 10.

Figure 10: Datasets for training GAI models.

Text-based datasets

Common Crawl dataset provides significant volumes of web data gathered from multiple pages, with frequent monthly updates. It has played a crucial role in training other notable language models, including GPT-3 and BERT. However, it comes with challenges like noise, bias, and ethical concerns around privacy and copyright. Careful filtering and responsible use are essential, but despite these hurdles, it has greatly advanced AI research (Wenzek et al., 2020; Luccioni & Viviano, 2021; Baack, 2024).

RefinedWeb is a high-quality dataset built from Common Crawl, used to train models like Falcon-40B. It combines scale, diversity, and cost-efficiency, making it ideal for pre-training LLM (Penedo et al., 2023). While it faces challenges like noise, bias, and ethical concerns, it has pushed GAI forward, powering everything from chatbots to recommendation systems and domain-specific applications.

Pile is a collection of 22 datasets, including a total of 800 GB of data. It is designed to enhance the performance of models such as LLaMA by enhancing their understanding of various settings (Gao et al., 2020). Its high-quality, human-generated content helps improve AI reliability, but it also comes with challenges like bias, copyright concerns, and data redundancy. Since it’s mostly in English, its multilingual potential is limited, and ethical concerns arise from sensitive forum content and the environmental cost of training (Biderman, Bicheno & Eleutherai, 2022).

Colossal Clean Crawled Corpus (C4) is a 750 GB dataset from Common Crawl, designed to filter meaningful text for training AI models like Google’s T5. It supports tasks like translation, summarization, and Q&A by providing diverse web content (Dodge et al., 2021). While it enhances AI generalization, challenges like bias, quality inconsistencies, and ethical concerns from web scraping remain.

BookCorpus dataset is a dataset of about 11,000 unpublished books with nearly a billion words, widely used in AI to train models like BERT and GPT. Its rich linguistic diversity helps with language modeling and creative text generation, but it has drawbacks like genre imbalance, inconsistent quality, and lack of metadata. Ethical concerns include the use of books without author consent, and its English-only content limits multilingual applications (Bandy & Vincent, 2021; Liu et al., 2024a).

Responsible Open-science Open-collaboration Text Sources (ROOTS) is a 16 TB multilingual dataset, created under the BigScience initiative to train models like BLOOM. Sourced from Common Crawl, GitHub, and more, it supports AI tasks like language modeling, translation, and bias research (Ostendorff et al., 2024). ROOTS promote ethical AI through open collaboration, but challenges like data quality, bias, and legal constraints remain (Piktus et al., 2023).

Wikipedia dataset is a multilingual collection of cleaned Wikipedia text, used to train AI models like GPT, BERT, and T5 (Ostendorff et al., 2024). Its structured, factual content makes it great for language models, knowledge graphs, and Q&A systems. However, it has biases, quality inconsistencies, and gaps in less-represented topics and languages (Shen, Qi & Baldwin, 2017).

OpenWebText: OpenWebText is an open-source version of OpenAI’s WebText, featuring 38 GB of curated web content used to train models like GPT-2 and GPT-3 (Perełkiewicz & Poświata, 2025). It enhances AI by providing diverse, readable text but has challenges like quality inconsistencies, biases, and ethical concerns.

The Red Pajama dataset is a 1.2 trillion-token open-source collection from Common Crawl, GitHub, books, and more, designed to replicate LLaMA’s training data. It powers models like OpenLLaMA, promoting transparency and open AI research. However, it faces challenges like bias and legal concerns (Penedo et al., 2023).

Cross-lingual Public Pool of Prompts (xP3) is a comprehensive repository containing datasets and prompts across 46 languages and encompassing 16 tasks related to NLP. It is an essential resource for training advanced multilingual language models such as BLOOMZ (Muennighoff et al., 2022). It supports instruction tuning, bias mitigation, and cross-lingual learning. While offering rich linguistic diversity, it faces challenges like data inconsistencies and bias (Üstün et al., 2024).

AnyInstruct-108k The AnyInstruct-108k dataset contains 108,000 instruction-response pairs used to train AnyGPT, a multimodal LLM capable of processing text, images, speech, and music. By leveraging discrete representations, AnyGPT integrates these modalities without modifying its core architecture. The dataset enables zero-shot and few-shot learning, but challenges like bias, limited real-world complexity, and ethical concerns around data privacy remain (Zhan et al., 2024).

Public Pool of Prompts (P3) is a collection of over 2,000 English prompts from more than 270 datasets, designed for NLP tasks like zero-shot learning. It has trained models like Flan-T5, enhancing multitask learning across reasoning and instructional tasks. However, P3 faces challenges like bias, quality inconsistencies, and a static nature, limiting long-term adaptability (Bach et al., 2022; Sanh et al., 2021).

Image-based datasets

The COYO-700M dataset contains 747 million image-text pairs with meta-attributes, designed for training multimodal AI models. Sourced from HTML documents, it supports text-to-image generation and has powered models like Vision Transformer (ViT). While promoting accessibility and collaboration, it faces challenges like data noise, bias, and ethical concerns, highlighting the need for careful filtering and curation (Lu et al., 2023).

Microsoft Common Objects in Context (MS COCO) contains over 300,000 images with captions. It has been used to train GAI models like Bootstrapped Language-Image Pretraining 2 (BLIP-2) (Li et al., 2023), enabling advancements in vision-language tasks such as image captioning and visual question answering. However, it faces challenges like dataset limitations, biases, and environmental concerns (Lin et al., 2014).

Flickr30k contains 30,000 images, each with five captions, making it a key resource for image captioning, visual question answering, and multimodal AI. It has helped train models like BLIP-2, advancing cross-modal AI applications (Liu et al., 2024b). However, it faces limitations such as its small scale, potential biases, and ethical concerns around privacy and demographic representation (Plummer et al., 2015).

Large AI Open Network-400M/5B (LAION-400M/5B) is a massive collection of image-text pairs (400M and 5.85B, respectively) used to train GAI models like CLIP, BLIP, and DALL-E. It powers tasks like text-to-image generation and visual question answering. However, it faces challenges such as noisy data, biases, insufficient curation, privacy concerns, and high computational costs (Schuhmann et al., 2022).

ImageNet: contains over 14 million labeled images across 20,000 categories, making it a cornerstone for computer vision and GAI. It has powered models like ResNet, AlexNet, VGG, and Vision Transformers (ViTs) for tasks like image classification and object detection. However, it faces challenges such as biases, labeling errors, static imagery, privacy concerns, and environmental impact (Krizhevsky, Sutskever & Hinton, 2012).

Video-based datasets

YouTube-8M is a massive video collection with 8 million labeled videos across 4,800 classes, supporting tasks like video classification and content recommendation. It has helped train models like Deep Bag-of-Frames (DBoF), LSTM, and MoE. However, its reliance on pre-computed features limits detailed analysis, and ethical concerns around privacy and copyright remain challenges (Abu-El-Haija et al., 2016).

InternVid includes over seven million videos and 234 million clips with detailed captions, making it a key resource for video-text understanding. It supports tasks like video captioning, retrieval, and generative video synthesis, training models like ViCLIP for zero-shot action recognition. However, challenges include biases, noisy data, high computational demands, privacy concerns, and costly storage and annotation (Wang et al., 2023).

Multimodal datasets

Multimodal Sentiment Understanding and Emotion Recognition (MuSe) combines text, audio, and visual data with 20,000 labeled video segments for sentiment and emotion analysis. It supports tasks like emotion recognition and human-computer interaction but faces challenges like demographic biases, data inconsistencies, and privacy concerns. Models like GRU-RNN and GRUs have leveraged MuSe for tasks such as mimicked emotions and cross-cultural humor detection in events like MuSe 2023 (Brooks et al., 2023).

VisualGenome features over 108,000 images with rich textual annotations, enabling tasks like visual question answering, image captioning, and scene graph generation. While it’s a key resource for multimodal learning, it has challenges like annotation errors, scalability issues, and biases (Kim et al., 2024).

Conceptual Captions: s a massive dataset of image-caption pairs, widely used to train text-to-image models like CLIP and DALL-E. It provides linguistic diversity and real-world relevance but comes with challenges like caption inaccuracies, lack of context, and biases. Ethical concerns, including copyright and privacy issues, also pose challenges (Ivezić & Babac, 2023).

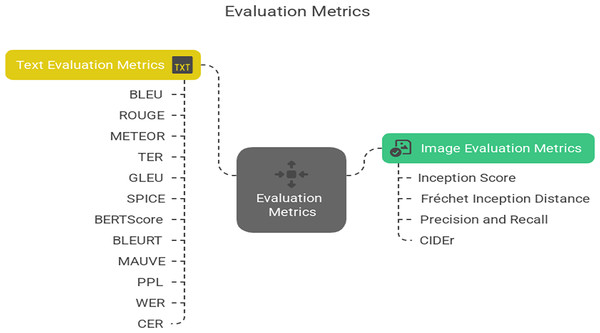

Evaluation metrics

Evaluating LLMs that generate both text and images requires a diverse set of metrics to assess the quality, diversity, and realism of their outputs across different modalities. This article highlights various evaluation metrics introduced in GAI to measure the performance of LLMs. Figure 11 provides a concise summary of these evaluation metrics, categorizing them for both text and image generation tasks. These metrics are essential for assessing the quality, diversity, and realism of outputs produced by generative models. However, these existing metrics are insufficient for accurately capturing the full scope of LLM capabilities. There remains a need for new and more effective evaluation metrics that can provide a comprehensive assessment of LLMs’ quality across both text and image generation.

Figure 11: Evaluation metrics for generative models’ performance.

Image evaluation metrics

The inception score (IS)

IS is a metric used to evaluate the quality of images produced by GANs (Barratt & Sharma, 2018). The score quantifies two aspects of the generated samples: the entropy of each individual sample with respect to the class labels, and the entropy of the class distribution across a large number of samples to assess their diversity. In order for a model to be considered well-trained, the entropy of a class for a single sample should be minimized, while the entropy of the class distribution across all generated samples should be maximized (Raut & Singh, 2024).

where DKL is the KL divergence between the conditional and marginal distributions, p(y|x) indicates the conditional probability distribution, p(y) is the marginal probability distribution, and Ex~pg is the sum and average of all results.

The Fréchet inception distance (FID)

FID is a statistic used to measure the level of realism and diversity in images produced by GANs (Yu, Zhang & Deng 2021). FID is employed for the analysis of images and is not typically utilized for text, sounds, or other modalities. It measures the influence of modifications in neural network models on realism and compares the advantages of various GAN models in generating images. It effectively evaluates both the visual quality and diversity using a single metric. A lower score indicates a higher resemblance between generated images and genuine images.

Precision and recall

Precision and recall are two metrics used to assess the diversity and quality of the generated samples, specifically addressing the problem of mode dropping. The system generates a two-dimensional score that evaluates the quality of the created images based on precision, which measures the accuracy, and recall, which reflects the extent of coverage by the generative model (Assefa et al., 2018; Kynkäänniemi et al., 2019).

where True Positives (TP) indicate the number of correct positive predictions, False Positives (FP) signify the number of incorrect positive predictions, and False Negatives (FN) represent the number of actual positives that were incorrectly predicted as negatives.

Consensus-based Image Description Evaluation (CIDEr)

The CIDEr metric measures the similarity between a sentence generated by a machine and a collection of sentences authored by humans. This statistic exhibits a high degree of agreement with human judgment on consensus. Through the utilization of sentence similarity, CIDEr automatically encompasses multiple linguistic and evaluative elements, such as grammaticality, saliency, importance, and accuracy (both precision and recall) (Vedantam, Zitnick & Parikh, 2014).

where |C| represents the number of reference captions, wn are weights assigned to diverse n-grams, N is the total number of documents and count indicates the count of n-grams in the created caption that match those in the reference caption.

Text evaluation metrics