FRVC: frame relevance based video compression for surveillance videos using deep learning methods

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Antonio Jesus Diaz-Honrubia

- Subject Areas

- Artificial Intelligence, Computer Vision, Multimedia

- Keywords

- Urban monitoring, Resource utilization, Sustainable resource consumption, Mask R-CNN, ATM CCTV video, Bank CCTV video, Video compression

- Copyright

- © 2025 Agrawal et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ Computer Science) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2025. FRVC: frame relevance based video compression for surveillance videos using deep learning methods. PeerJ Computer Science 11:e3155 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.3155

Abstract

The prevalence of closed-circuit television cameras (CCTV) has witnessed a rapid escalation over recent decades. CCTV serves the purposes of safety, security, and monitoring across various sectors, that contribute to smart infrastructure and sustainable urban development. Though the requirement for CCTV increases, it faces major challenges in surveillance video storage, particularly in high-resolution systems. This results in substantial storage demands, leading to economic and environmental concerns regarding resource utilization and management, aligning with the goals of resource efficiency and sustainable consumption. To address these issues, we propose a frame relevance-based video compression (FRVC) algorithm comprising three phases: (i) dataset preparation, (ii) relevance frame classification, and (iii) video compression. This approach ensures the resilient and efficient management of video data, which enhances its usefulness in urban monitoring. The FRVC framework was tested using a customized surveillance video dataset under three scenarios. In the relevance frame classification module, Mask region-based convolutional neural network (Mask R-CNN) and You Only Look Once version 9 (YOLOv9) object detection approaches are used to detect relevant frames of surveillance video where YOLOv9 surpasses Mask R-CNN in terms of evaluation metrics (accuracy, precision and F1-score) for 80–20 dataset ratio. The proposed FRVC achieves a compression rate up to 96.3%, 99.9% and 63.3% for three different scenarios respectively. Compressed videos maintain the same resolution and frame rate as compared to the original video. This innovative framework supports sustainable technology adoption in the development of surveillance systems, contributing to long-term data storage solutions and cost-effective urban monitoring.

Introduction

Currently, surveillance cameras have become a necessary part of everyone’s life as they provide an optimum level of safety and security (Dhiravidachelvi et al., 2023). The proliferation of surveillance cameras to more than one billion units indicates its prevalent need (Lin & Purnell, 2019). As the need for surveillance increases, service providers consistently improve the quality of surveillance video by augmenting spatial and temporal resolutions and frame rates (Adil et al., 2020). This enhancement inevitably results in an expansion of the storage capacity required for surveillance video. It is naive to think that simply increasing the capacity of storage requirements will solve the problem. Typically, closed-circuit television cameras (CCTV) surveillance videos are selectively stored on either cloud platforms or local storage devices, such as microSD cards and local hard drives. The continuous recording of 24 7 surveillance video results in the rapid exhaustion of storage capacity on local hard drives. As a result, the surveillance video was deleted after a specific time interval. This may lead to a loss of relevant information from the user’s perspective, hence the need to develop a relevance-based domain-specific compression technique arises. This technique minimizes the storage requirement and makes it feasible to store surveillance data for a longer duration without facing exorbitant storage costs.

Highly efficient video coding (HEVC/H.265) is the most advanced video compression technology developed by a joint collaborative team on video coding in 2013 (Sullivan et al., 2012). H.265 gains a 50% reduction rate and maintains the same visual quality when compared to its ancestor H.264 (Wiegand et al., 2003). The predictional and directional mode in H.265 increases to 35 modes (including DC and Planar mode) as compared to H.264 (10 modes including DC and Planar). Both coding schemes used traditional handcrafted predictive coding and transform coding approaches such as block-based motion estimation and discrete cosine transform (Li et al., 2021). Though these approaches are fine-tuned and well-developed, they can’t cope with growing technology. It is difficult to make further enhancements to the existing technology (Jayaratne, Gunawardhana & Samarathunga, 2022). Moreover, deep learning approaches have achieved remarkable success in many computer vision applications. A neural network is used to optimize many tools of video compression algorithms. The convolutional neural network (CNN), fully connected network (FC), generative adversarial network (GAN) and recurrent neural network (RNN) are used to perform compression using different tools of H.265 like intra-prediction (between block), inter-prediction (between frames), up-down sampling, in-out loop filtering, and encoding optimizer named as deep tool (Liu et al., 2020). Using a neural network, the researcher enhances the performance of a single tool of H.265 framework. In recent years, various deep learning-based video compression techniques have been explored to overcome the limitations of traditional codecs. These methods often leverage CNN and RNN to perform frame interpolation, motion estimation, and residual compression (Lu et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2020; Agustsson et al., 2020). While these approaches have shown promising improvements in compression performance, they primarily focus on general-purpose video content and do not consider domain-specific constraints, such as the relevance of video frames in surveillance footage. Furthermore, most existing methods treat all frames equally, irrespective of their informational content. This is particularly inefficient in fixed-camera surveillance setups such as automated teller machines (ATM) or offices where a significant portion of the footage contains static scenes with no human activity. Existing works like Rippel, Nair & Lew (2019) emphasize end-to-end learning for compression but lack frame-level filtering based on semantic relevance. Hence, there is a pressing need for an intelligent, relevance-aware compression framework tailored for surveillance systems, especially under constrained storage environments.

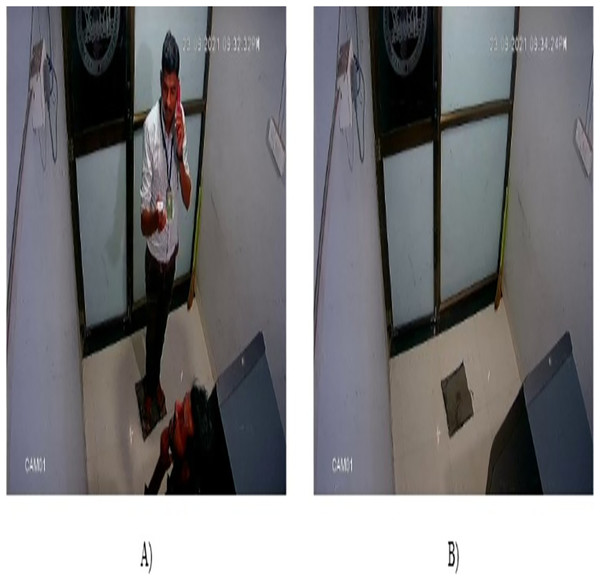

CCTV cameras are strategically positioned in various locations such as educational institutions, commercial establishments, city roads, highways, financial institutions, ATM, corporate offices, and more, to bolster security and facilitate monitoring (Yeganegi, Moradi & Obaid, 2020). This deployment of CCTV cameras helps in monitoring events and activities in the vicinity but this system faces the major issue of limited storage capacity (Akash & Anderson, 2024). As a result, this surveillance video was deleted after some time interval, for example, school and college footage was erased after 1 month, bank, office, and ATM recordings after 6 months, and city road and highway videos after 3 months. Due to this, relevant information was also lost in the video. To preserve relevant information for an extended period, this article proposed the frame relevance-based video compression (FRVC) framework where we used ATM surveillance video. The surveillance camera present in the ATM room captured 24 7 video. In reality, only a few hours of the log activity was performed while the remaining time slot contained only a fixed ATM, and hence maximum space is utilized to store a steady machine. To address this issue, we developed the FRVC framework for the compression of ATM surveillance video. The FRVC framework is divided into three phases: In the first phase, the FRVC dataset is prepared and annotated. In the second phase, a neural network approach is used to discern objects within the ATM room. This process leads to the classification of frames as either relevant or irrelevant frames. Specifically, frames containing the presence of humans or animals in the ATM room are categorized as relevant frames, whereas frames solely depicting the ATM without such presence are designated as irrelevant frames. Figure 1 represents a visual representation of relevant and irrelevant frames of surveillance video. We employ customized one-phase object detectors You Only Look Once version 9 (YOLOv9) and two-phase object detector mask region-based convolutional neural network (Mask R-CNN) to predict relevant and irrelevant frames of surveillance video. Following the frame categorization process, we turn our attention to the relevant frames only and in the third phase, the similarity index among them is identified at different threshold levels. These relevant frames are subsequently divided into primary and similar frames. Finally, the compressed video is obtained by combining the relevant primary frames. The major contributions of our research work are listed as follows:

-

1.

Collected 15 ATM surveillance videos of 1 h duration, and then the videos were split into smaller segments consisting of 18,000 to 35,000 frames to minimize the time and computational complexity for further processing.

-

2.

Developed an ATM surveillance video dataset to train object detection modules.

-

3.

Used Mask R-CNN and YOLOv9 object detection modules to identify relevant frames (person or animal detected in frame) and irrelevant frames (fixed ATM present in frame) of surveillance video from user perspective.

-

4.

For further processing relevant frames are considered and similarity indices among consecutive frames at different threshold values are determined. These identified relevant frames are subsequently segregated into primary and similar frames. Ultimately, the compressed video is derived by amalgamating the relevant primary frames.

-

5.

The proposed FRVC module applies to all types of surveillance video where relevant frames are needed to store from a user perspective.

-

6.

Present decompression module to retrieve 100% of relevant primary frames.

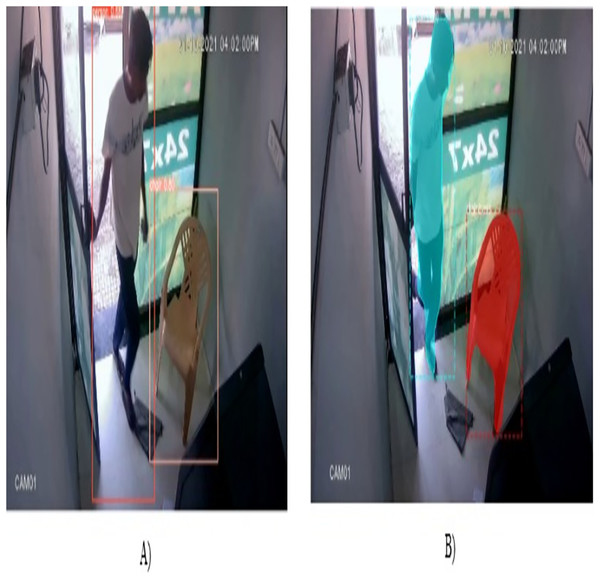

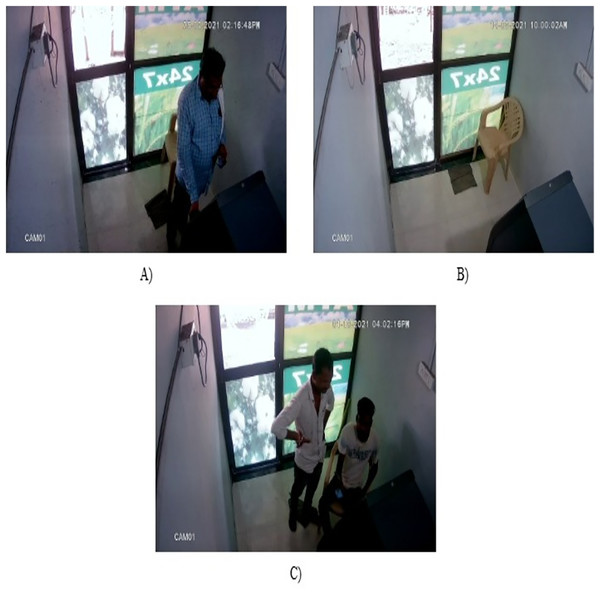

Figure 1: Sample frames of ATM surveillance video (A) Relevant frame (B) Irrelevant frame.

The rest of the article is structured as follows: ‘State-of-Arts Survey’ highlights the related works which are further splits into three categories:- object detection, video compression, and surveillance video compression articles. ‘Materials and Methods’ gives details of the FRVC framework and explains the architecture of OD modules with the FRVC algorithm while the decompression process is explained in ‘Decompression’. The evaluation of the proposed research work using various performance metrics is presented in ‘Results and Analysis’. A comparison with state-of-the-art algorithms is analyzed in ‘State-of-the-Art Works Comparison’ and ‘Conclusions’ concludes our research work.

State-of-arts survey

The proposed FRVC framework utilizes deep learning (DL) based object detection (OD) techniques for efficient surveillance video compression. This section provides a comprehensive review of foundational and recent advancements in object detection and video compression methods, along with developments in surveillance compression strategies. This background facilitates a comprehensive understanding of the integration of object detection and compression methods within the FRVC framework to optimize video storage.

Object detection

Object detection (OD) is a technique in which the class of an object and its location is detected through bounding boxes in an image. After OD, researchers focus their attention on semantic segmentation, which aims to classify each pixel into a fixed set of categories without differentiating object instances. Semantic segmentation and object detection together form instance segmentation, which differentiates objects using pixel-level masking. These DL-based OD is divided into two categories which are summarized as follows:-

Two-phase detector

DL-based two-phase object detector algorithm divides the OD process into two parts:- in the first part it generates the proposed region and in the second part it performs classification followed by the bounding box regression. Girshick et al. (2014) developed R-CNN that generates a 2K region proposal using the selective search method. For feature extraction, these proposed regions are cropped and wrapped into a 227 227 size and provided as input to the CNN. Lastly, support vector machine (SVM) is used to classify the object present in the proposed region. This approach improves the mean Average Precision (mAP) by 30% but suffers from two major drawbacks: (i) generation of 2K region proposal per image is a time-consuming process and (ii) cropping and wrapping of the proposed region causes the loss of valuable information. To avoid the resizing of an image, He et al. (2015) developed a spatial pyramid pooling network (SPPNet). In SPP-net, feature maps are computed from the entire image only once and pooling operations are applied within arbitrary regions (sub-images) to generate fixed-length representations for training detectors. In real, the FC layer requires fixed-size input, hence author adds SPP layer in front of a fully connected layer to aggregate the outcomes of various pooling layers and then sends them to the FC layer for classification. Later, Girshick (2015) developed Fast-R-CNN to minimize the time required for training and testing of R-CNN. Fast R-CNN introduced a region of interest (RoI) pooling layer followed by two FC layers, a soft-max classifier and bounding box regression. Though Fast R-CNN achieved only 0.9% gain in accuracy but it is 146 times faster than R-CNN (Xu, 2021). Ren et al. (2015) proposed Faster R-CNN, where the selective search approach is replaced by the anchor box method to generate a region proposal network (RPN) and achieved significant gain in training speed and accuracy. Faster-R-CNN generates RPN more quickly and uses dense sampling, it extracts more semantic features rather than spatial features during feature extraction. To make OD feasible at various scales and to extract prominent features, Lin et al. (2017) proposes a feature pyramid network (FPN) that aggregates low-resolution features with high-resolution features using a bottom-up and top-down approach.

Instance segmentation is an approach to differentiate various instances of the same category. Dai, He & Sun (2016) proposed a multi-step approach known as multi-task network cascades (MNC), it split the entire detection architecture into various stages and performed semantic segmentation from the learned bounding box. However, multi-step training predicts the false edge of an object at the time of overlapping instance. To address this issue, He et al. (2017) proposed Mask R-CNN which adheres to the spirit of Faster R-CNN. Mask R-CNN performs OD, classification, and instance segmentation simultaneously. Because of RoI pooling, Faster R-CNN faces the issue of misalignment between RoI and features, which is solved by Mask R-CNN using RoI-alignment with bilinear transformation. The popular OD frameworks for one-phase and two-phase detectors, with dataset and various evaluation metrics, are summarized in an article (Agrawal, Mohod & Madaan, 2023).

One-phase detector

One-phase object detector algorithm performs detection and classification in one stage, rather than generating the proposed region. These algorithms outperform two-phase detectors in detection speed but lack detection accuracy (Xiao et al., 2020). Sermanet et al. (2013) developed the first one-phase detector named OVERFEAT which surpassed all existing frameworks of that time. With a sliding window and multiscale technique, OVERFEAT performs OD, classification, and localization using a CNN. Later, Redmon et al. (2016) presents the You Only Look Once (YOLO) algorithm to perform OD in real-time. YOLO splits the input image into S S grid cell and if the center of an object is present in the grid cell then that cell is responsible for determining the object. Each cell predicts several bounding boxes, confidence score, and class probability for those boxes. Using the non-max suppression model, the best bounding box among all predicted ones is selected. Although YOLO achieves remarkable success, it is unable to detect more than two objects in an image and to perform detection at multiple scales. To address the YOLO issues, Liu et al. (2016) developed the single shot multi-box detector (SSD) which also divides the input image into S S grid cell and used the anchor box method to predict the object with multiple aspect ratios and scale. SSD also uses multiple feature maps to predict the object and achieves an accuracy comparable to that of faster R-CNN in real time. To make YOLO better and accurate, Redmon & Farhadi (2017) introduced YOLO9000 (YOLOv2) which is trained over 9,000 different object categories. Inspired by SSD, YOLOv2 removes the fully connected layer and uses the anchor box method which is integrated with batch normalization (BN). YOLOv2 also performs multi-scale training to detect the object more precisely and outperforms other state-of-the-art results at that time.

Depending on the principles of YOLOv1 and YOLOv2, Redmon & Faradi (2018) developed YOLOv3, which addresses limitations in terms of speed and accuracy. YOLOv3 uses DarkNet-53 architecture with a residue block and skip connection to perform feature extraction. For detection, 53 convolutional layers followed by BN and leaky ReLU activation function were added in the architecture of YOLOv3. It detects the object at three different layers (82, 94, 106 layers) and three different scales (13 13, 26 26, 52 52), generates 10,647 bounding boxes and predicts the best box using a non-max suppression approach. The inventor of YOLO versions, Joseph Redmon, quits to perform further enhancement in YOLO and Alexei Bochkovsky took the responsibility and developed YOLOv4 in April 2020. Bochkovskiy, Wang & Liao (2020) used Bag-of-Freebies (BoF) and Bag-of-specials (Bos) techniques to improve the accuracy of YOLOv4 in all versions of YOLO. For the first time, the concept of the neck is added to the object detection framework. Cross-stage-partial connection (CSP) Darknet-53 is used for feature extraction, SPP or path aggregation network (PANNet) is used in neck to aggregate spatial and semantic features and at last YOLO layers (which are used in YOLOv3) detect the objects. Later, ultralytics developed YOLOv5 on the Pytorch framework using the swish activation function (Jocher et al., 2022). Like YOLOv4, YOLOv5 uses CSP-Darknet-53 as a backbone for feature extraction, in head PaNet is used to merge high-resolution and low-resolution features and YOLO layers to detect objects. YOLOv5 outperforms YOLOv4 in terms of speed and accuracy on surveillance data set (Mohod, Agrawal & Madaan, 2022). Wang, Bochkovskiy & Liao (2023) present YOLOv7 in July 2022 where CSPdarkNet-53 is replaced by an Extended Efficient Aggregation Network (E-ELAN). The head and neck structure of YOLOv7 is similar to YOLOv5. In 2023, Ultralytics revealed YOLOv8, an innovative region-free OD framework that surpasses all existing YOLO versions from V1 to V7 in terms of speed accuracy and speed (Jocher, Chaurasia & Qiu, 2023).

Video compression

Video compression is a process of reducing the bit count required to encode a video while maintaining its visual quality (Sayood, 2017). This is accomplished by identifying and exploiting the similarities between successive video frames. Standard videos typically run at 30 frames per second (FPS), where most of the content is identical across frames. The compression techniques search for residue information between the frames. Lossless video compression and lossy video compression are the two main types of video compression. lossless video compression attempts to shrink the size of video files without losing its video quality (Beach & Owen, 2018). While lossy video compression reduces video file sizes by removing some amount of data, typically the data that is less sensitive to the human visual system (Bull & Zhang, 2021). H.264 (Wiegand et al., 2003) and H.265 (Sullivan et al., 2012) are widely used lossy video compression algorithms that adapt the concept of a hybrid video coding framework. Here, input video data is split into frames, frames are divided into blocks and blocks into units, the largest unit is termed as control tree unit (CTU). CTU is also divided into the control unit (CU), CU into the prediction unit (PU), and at last PU into the transform unit (TU). These frames/blocks/units are compressed in a predefined manner termed as intra-frame prediction and in inter-frame prediction approaches. Earlier, compressed frames are used to compress or predict the next frame, respectively. Then predicted data are transformed, quantized, and entropy-coded to gain final coded bits. As predicted data is quantized, there might be a chance of losing some amount of data which may cause noise. To recover from this loss, two filtering strategies were suggested: (i) in-loop filtering (before predicting the next frame) and (ii) out-loop filtering (before output). In addition, to minimize the size of video data, the frames/blocks/units are down-sampled before compression and up-sampled afterward. H.265 and H.264 adopted this traditional procedure to perform compression while researchers tried to apply the concept of neural networks to the tools of this framework for e.g., intra-prediction, inter-prediction, filtering, sampling, and entropy coding is performed using DL approaches and achieved remarkable success in compression (Liu et al., 2020).

Recently, researchers focused on improving video compression by designing end-to-end trainable architectures that jointly optimize key components such as motion estimation, residual encoding, and entropy coding (Rippel, Nair & Lew, 2019). Lu et al. (2019) performs video compression in an end-to-end manner, learning-based optical flow estimation is used to acquire motion information and to reconstruct the current frames. Following this, two neural networks designed auto-encoders are used to compress both the associated motion and residual data. All of these components are collectively trained using a unified loss function. Agustsson et al. (2020) introduces a simplified approach using scale-space flow, a generalized motion model with a scale parameter to better handle disocclusions and fast motion. The proposed low-latency model, which avoids B-frames and pre-trained optical flow networks, achieves competitive or superior rate-distortion performance compared to state-of-the-art learned video compression methods, while significantly reduces architectural and training complexity. Though DL algorithms represent a promising avenue for advancing video compression techniques, there is potential for advancement in the field of surveillance video compression.

Surveillance video compression

This sub-section gives a review of video compression approaches applied to surveillance video. Lu & Xu (2019) presents a deep compression algorithm for apron surveillance. Researchers used the Fast-R-CNN (Girshick, 2015) OD technique to predict the object in apron surveillance and then the object is cropped according to its coordinates and saved on disk in linked list format. In this way, the foreground and background parts of images are differentiated with illumination and brightness information. While performing decompression, using coordinate information cropped objects placed at their position in background images and this approach efficiently solves the space issue. Ghamsarian et al. (2020) perform compression on a cataract surgery video using semantic segmentation approaches and perform categorization of a frame into active and idle frames. Later, active frames of videos are compressed with different quantization parameters under five different scenarios from an ophthalmologist’s point of view. Wu et al. (2020) perform compression on the foreground and background images in parallel using an end-to-end neural network approach. For foreground compression, motion estimation with residual encoding is used, and to share the background with neighboring frames the interpolation method is applied. In the article (Mohod, Agrawal & Madaan, 2024), object detection-based surveillance compression (ODSC) technique identifies objects within surveillance videos. This method utilizes various YOLO modules to distinguish between significant and non-significant frames. ODSC model used four surveillance videos for testing purposes and achieved 96% compression rate that outperforms other methods. To address error accumulation in inter-frame prediction for surveillance video compression, Zhao et al. (2024) proposes a Temporal Adaptive enhancement method for surveillance video compression (TALC) with Forward and Backward modules. These modules use adaptive selection and feature enhancement blocks to reduce distortion. TALC improves compression performance across various learned frameworks without altering their core architecture. UVCNet is an end-to-end unsupervised neural video compression framework that separates foreground and background online using temporal correlation. It applies residual coding for dynamic foreground and specialized compression for static background. UVCNet optimizes bitrate by leveraging scene dynamics and achieves a 2.11 dB PSNR improvement over H.265 on surveillance video datasets (Zhao et al., 2023).

Materials and Methods

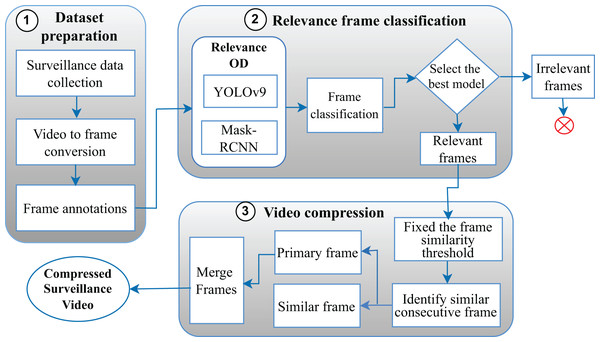

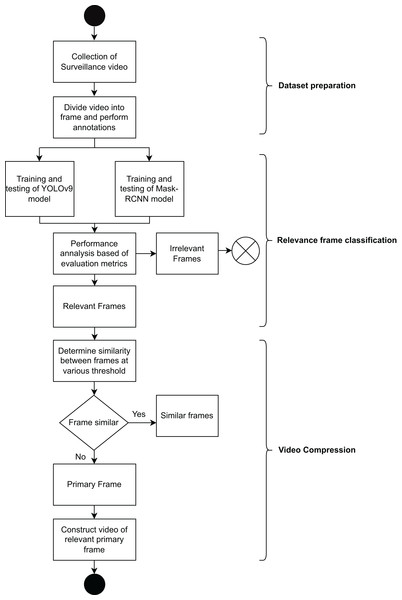

This section gives a detailed idea of the FRVC model which is divided into three steps shown in Fig. 2.

-

(i)

Dataset preparation;

-

(ii)

Relevance frame classification;

-

(iii)

Video compression.

Figure 2: Frame relevance based video compression model.

Dataset preparation

Surveillance data collection

The use case for our research work is the ATM surveillance video. We collected 15 ATM surveillance videos of 1 h from ADCC bank, Morshi, Maharashtra. The videos belongs from three ATM surveillance scenarios: Scenario-I features single-person transactions, Scenario-II includes clips with no human presence, and Scenario-III involves two individuals entering together. These conditions ensure varied scene complexity for evaluating detection and compression performance. The details about the scenarios is mentioned in ‘Evaluation and Analysis of Compression Module’. Later, to facilitate efficient processing and analysis of the videos, FFmpeg (https://ffmpeg.org/), a powerful multimedia framework, is used to divide each video into smaller, more manageable segments.

Video to frame conversion

Following the segmentation of the video into smaller segments, a total of 35 videos were obtained. Subsequently, 28 of these videos were used for the training phase, while the remaining seven videos were assigned for testing purposes. Initially, these videos were divided into frames using the OpenCV library.

Data annotation

Afterward, a random selection process was used and 6,600 frames are annotated to train the neural network. This particular subset of frames was carefully chosen to streamline the subsequent annotation process. Among these 6.6K frames, 4.5K frames were annotated as relevant frames and 2,100 frames as irrelevant frames for the relevance frame classification network.

Relevance frame classification

In the relevance frame classification module, we applied YOLOv9 from a one-phase detector and Mask R-CNN from a two-phase detector to identify relevant and irrelevant frames of surveillance videos. Unlike conventional OD approaches that detect all objects indiscriminately, relevance-based detection aims to optimize video processing tasks such as compression. Recent methods such as semantic-assisted object cluster (SOC) leverage temporal and textual cues to group relevant objects across frames, improving temporal coherence and detection performance (Li et al., 2023). Another notable approach, TransVOD, employs a spatial-temporal transformer architecture that integrates information across frames for more accurate object localization and classification (He et al., 2023). The proposed FRVC framework incorporates this concept of relevance by identifying objects that are not only present but also contextually important in terms of human activity and motion. Compared to earlier methods, our relevance approach focuses on retaining semantically meaningful content, which leads to enhanced compression efficiency without losing critical surveillance information using OD. The details architecture of YOLOv9 and Mask R-CNN detectors are explained as follows.

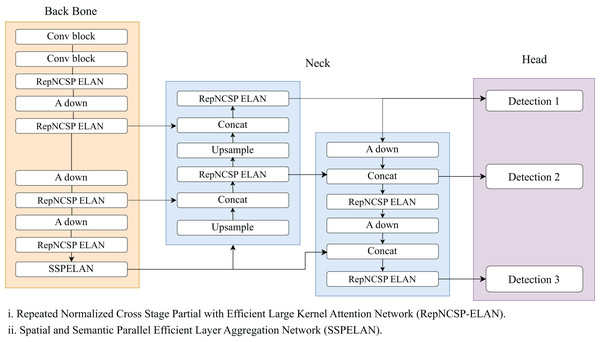

YOLOv9

Wang, Yeh & Liao (2024) presents you only look once version 9 i.e., YOLOv9 to tackle the issue of losing information in the deeper network. Unlike other YOLO, its architecture is divided into three parts: the backbone, neck, and head. The backbone of YOLOv9 incorporates advanced techniques such as programmable gradient information (PGI) and generalized efficient layer aggregation networks (GELAN). PGI optimizes gradient flow and improves training stability, efficiency, and feature learning in deep networks. While GELAN combines two neural network architectures, CSPNet (Wang et al., 2020) and ELAN (Wang, Liao & Yeh, 2022) to optimize feature extraction using a lightweight architecture. Figure 3 denotes the architecture diagram of YOLOv9. It also incorporates gradient path planning for better performance. The neck of YOLOv9 utilizes a PanNet to integrate multi-scale features and improve spatial context and localization accuracy. As we go deeper into the network, good quality semantic features are extracted but lacking in spatial features which are present at the early layers of the network. In order to merge both features, FPN uses top-down and bottom-up paths. While PanNet used the lateral connection to shorten the information path and focused on enhancing the high-resolution feature maps with detailed information. It consists of 1 × 1 convolutions that transform feature maps from the backbone into a common channel dimension. These transformed feature maps are then added element-wise with the higher-resolution feature maps from the bottom-up path. This step is crucial for aligning features across scales. At last, YOLO layers perform detection at multiple scales. This network places anchor boxes on the feature map generated by the preceding layer and produces a vector containing the target object’s category probability, object score, and the bounding box’s position. YOLOv9 also employs an asymmetric downsampling (A DOWN) block instead of max pooling, to preserve essential spatial information and to reduce the size of the feature map.

Figure 3: YOLOv9 architecture.

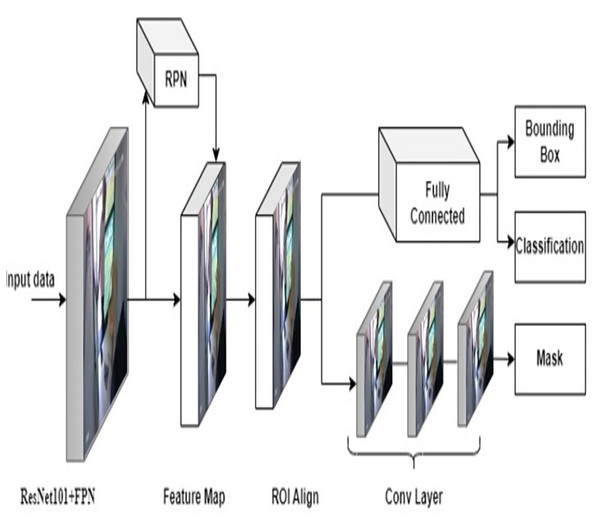

Mask R-CNN

He et al. (2017) introduced a novel, intuitive, flexible, and simple network to perform instance segmentation named as Mask R-CNN. The Mask R-CNN architecture embodies the essence of faster R-CNN while extending its capabilities to do instance-level segmentation. Hence, Mask R-CNN performs object categorization, bounding box regression, and pixel-level segmentation simultaneously. Figure 4 gives architecture details of Mask R-CNN network. Mask R-CNN used ResNet-50/ResNet-101 architecture as a backbone to extract high-quality features from images (He et al., 2016). The input image is passed through the backbone network, and a series of convolutional layers extract low-level and high-level features, which represent various aspects of the image, from edges to abstract object features. To address the issue of vanishing gradients, ResNet uses residual block connection which includes a “skip connection” to bypass one or more layers. This residual block consists of CNN, BN, skip connection and rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation function. Similar to YOLOv9, Mask R-CNN uses FPN with the ResNet model to extract fined and coarse features at various scales. After feature extraction, Mask R-CNN generates RPN that examines the features generated from the backbone and proposes the potential regions of images that might contain objects. For these regions, the RPN produces objectness scores and precise bounding box coordinates using anchor-box and non-max suppression approaches. After obtaining region proposals from the RPN, the next step is RoI Align. RoI Align is crucial for ensuring that the features within each region proposal are consistently aligned and resized to a fixed spatial dimension. In faster R-CNN, RoI pooling is used to extract fixed-size features from the proposals. However, in Mask R-CNN, the RoI-align operation is used to extract accurate and aligned features from the proposals, which addresses the issue of spatial misalignment between the feature map and the original image. RoI-align uses bilinear interpolation to retrieve feature values from the original feature map at non-integer locations rather than quantizing the RoI boundaries to the grid cells. Hence, using RoI alignment the loss of spatial information that occurs in RoI pooling is recoverable in Mask R-CNN and generates a binary mask for each object in an image. At last, the head component is responsible for making predictions and is divided into two parallel branches: object classification and mask prediction. The final output for each detected object includes the predicted bounding box coordinates, the assigned class label, and an instance segmentation mask, enabling both object detection and detailed instance segmentation. Figures 5 and 6 denote the relevant frames and irrelevant frames of surveillance video using Mask R-CNN and YOLOv9 module, respectively.

Figure 4: Mask R-CNN architecture.

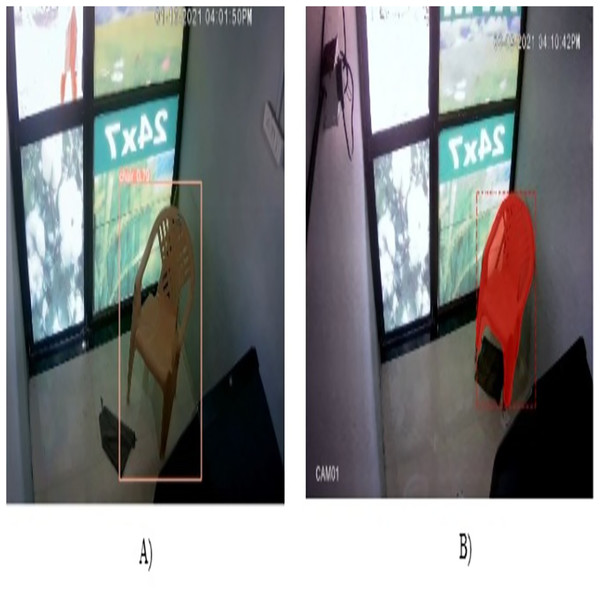

Figure 5: Identified relevant frame using (A) YOLOv9 module and (B) Mask R-CNN module.

Figure 6: Identified irrerlevant frame using (A) YOLOv9 module and (B) Mask R-CNN module.

Compression module

In the compression module of the FRVC framework, processing is performed on the relevant frames of ATM surveillance video which is identified using the relevance frame classification module. While the irrelevant frames are discarded from the network. On relevant frames, we determine the similarity index between frames across various threshold values and further categorize these frames into primary frames and similar frames. Primary frames are defined as frames that exhibit difference when compared with their consecutive frames. If consecutive frames are identical, they are categorized as similar frames and the first dissimilar frame is marked as the next primary frame. For instance, the 1st frame is considered as the primary frame and it is compared with its consecutive frames. If the initial frame is similar to the 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 5th frames but dissimilar to the 6th frame, then 1st and 6th frame are considered as primary frames, while 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 5th frames are designated as similar frames. As the 6th frame is dissimilar to the first frame, it is subsequently identified as the next primary frame and the process continues until all relevant frames exhaust. We determine the similarity between frames at various threshold values ranging from 100% to 90% and save the count of the similar frames corresponding to the primary frame in a data structure. Lastly, the video is constructed using relevant primary frames, at the original FPS. Equation (1) gives the formula to predict the similarity between frames (Wang et al., 2004). The Structural Similarity Index (SSIM) is a composite measure that evaluates the similarity between two images based on three components: luminance, contrast, and structure. The luminance component quantifies the similarity in average brightness, computed using the means of pixel intensities. The contrast component measures variability in the images, expressed through standard deviations. The structure component evaluates the correlation between the two images using covariance. These components are combined multiplicatively to yield the overall SSIM index.

(1)

In the above equation, the variables represent various components used to quantify the SSIM between two images, x and y. Here’s an explanation of these variables:

-

(i)

x and y (Images): x and y represent the pixel values of the two images. The formula assesses the similarity between these two images.

-

(ii)

L(x, y) (Luminance Comparison): The L(x, y) term represents the luminance comparison between the images. It measures the similarity in terms of brightness and contrast between x and y.

-

(iii)

L’(x, y) (Contrast Comparison): The L’(x, y) term is the contrast comparison component. It quantifies the structure and variations in the contrast between the two images.

-

(iv)

c1, c2, and c3 (Constants): These are constants introduced in the SSIM formula to stabilize the division and prevent division by zero errors. They are typically small positive values that are added to the denominator to ensure numerical stability.

FRVC algorithm

To implement the FRVC model, we used Sypder version-5 (Python 3.9) on intel 11th Generation, i7 Processor. The required configuration of the system is 16 GB RAM and 512 GB SSD on the Windows platform with NVIDIA GeForce GPU. Algorithm 1 demonstrates the step-by-step execution of the proposed FRVC model:-

-

(1)

The algorithm begins by determining the FPS of the input video. Later, FRVC extracts the frames from the video.

-

(2)

Then various variable lists are initialized to store the data. For e.g., relevantFrames is an empty list created to store frames that are considered relevant. PrimaryFrames is an empty list to save primary frames, and similarFrames is an empty list to store similar frames. NextPrimary is initialized with a value of 1 and will be used to track the next primary frame. similarityThreshold is an initial value used as a reference for measuring the similarity of frames at various threshold values (100%, 98%, 96%, 94%, 92%, 90%).

-

(3)

The algorithm goes through all the frames of the video. and apply two object detection algorithms: Mask R-CNN and YOLOv9, to identify objects within the frame. It checks if the frame is relevant based on the detected objects. If a frame contains relevant objects (e.g., person), it adds the frame to the relevant frames list. If not, it discards the frame as it is not considered relevant.

-

(4)

For each relevant frame in the relevant frames list, the algorithm compares the frame’s similarity with the next frame in the list. If the frame’s similarity with the next frame is above the similarity threshold, it is classified as a similar frame and added to the similar frames list. If the similarity is below the threshold, the frame is classified as a primary frame and added to the primary frames list. Additionally, the next primary variable is updated to keep track of the current primary frame. The count of the similar frame corresponding to the primary frame is maintained in an Excel file.

-

(5)

Finally, the algorithm constructs the compressed surveillance video using the relevant primary frames at the original FPS. This step creates a new video that retains important frames while removing less significant ones, effectively compressing the video. After the construction of the compressed video, the data structure is stored on the disk.

| Input: ATM surveillance video |

| Output: Compressed surveillance video |

| 1. Determine the FPS of the video and Extract frames from the input video |

| 2. Initialize an empty list for relevant frames: |

| 3. Initialize an empty list for primary and similar frames : and |

| 4. Initialize a variable nextPrimary to 1 |

| 5. Initialize a variable similarityThreshold to any value between 90–100 |

| 6. Initialize an empty dictionary |

| 7. for each frame in the video do |

| Apply Mask R-CNN and YOLOv9 object detection to identify objects |

| if frame is relevant then |

| Add the frame to the relevant frames list: |

| else |

| Discard the frame |

| end if |

| 8. end for |

| 9. for each relevant frame in the relevant frames list do |

| if frame similarity with the next frame is above similarityThreshold then |

| Add the frame to the similar frames list: |

| else |

| Add the frame to the primary frames list: |

| current frame |

| end if |

| Save in an Excel file |

| 10. end for |

| 11. Construct the compressed video using relevant primary frames at the original FPS |

The sequence flow diagram of the FRVC model is shown in Fig. 7. Here, the framework is divided into the following steps:-

-

(i)

In the initial phase, namely “dataset preparation”, the process begins with the collection of surveillance videos, and this video is further split into frames. Subsequently, annotations are applied to these frames.

-

(ii)

In the second phase i.e., “relevance frame classification” We trained the one-phase YOLOv9 and the two-phase Mask R-CNN on the FRVC dataset. Subsequently, we employed these trained models to analyze the remaining ATM surveillance video as part of our testing process and predict the relevant and irrelevant frames of surveillance video. Depending upon the evaluation metrics and time required to identify the relevant and irrelevant frames, the best model for OD is determined.

-

(iii)

In the final stage, known as “Video compression”, relevant frames are taken as input, and depending upon similarity at various threshold values primary and similar frames are categorized. In the end, the compressed video is constructed using relevant primary frames at the original video’s FPS value.

Figure 7: Sequence flow diagram of FRVC model.

Decompression

To perform decompression of the video, the list (data structure) stored on the disk is retrieved. During compression, the count of similar frames corresponding to primary frames are stored in the list. This list guides us to reconstruct original video using Algorithm 2 that demonstrates the flow of the decompression module. Firstly, the algorithm initializes essential variables and sets up the decompressed video. Subsequently, it designates the first primary frame as the starting point for decompression and appends it to the decompressed video. The algorithm then enters a loop that iterates through the frames stored in the data structure. Within this loop, each primary frame encountered determines the count of similar frames related to that primary frame. Through a nested loop, the algorithm appends each of these similar frames to the decompressed video. After processing the similar frames, the algorithm progresses to the next primary frame and includes it in the decompressed video. This iterative process continues until all frames in the data structure have been processed. Ultimately, the algorithm concludes by returning the fully reconstructed decompressed video, effectively restoring the original content based on the categorization of frames established during compression in the FRVC framework.

| 1 Input: Compressed surveillance video and data structure list |

| 2 Output: Decompressed surveillance video |

| 1. Initialize variables and decompressed video |

| 2. currentFrame ← first primary frame |

| 3. Append currentFrame to decompressed video at given FPS |

| 4. While there are more frames in Data Structure |

| (a) similarFrames ← count of similar frames for currentFrame |

| (b) For each similarFrame in similarFrames |

| i. Append similarFrame to decompressed video |

| (c) currentFrame ← next primary frame |

| (d) Append currentFrame to decompressed video |

| 5. Return Decompressed Video |

Despite attaining the highest compression of 96.3%, our decompression algorithm ensures the retrieval of 100% of relevant data. The pre-processing operation is not applied to the frames of surveillance video, an inherent characteristic emerges where the frames exhibit a 100% similarity to each other when the threshold value is set to 1. However, as the threshold values decrease from 98% to 90%, the observed similarity between frames progressively diminishes. This decline in similarity can be attributed to the comparison process, wherein the first frame is systematically evaluated against the second or third frame. As a consequence, the stringent threshold values lead to a reduction in the permissible dissimilarity between consecutive frames, resulting in the recorded similarity indices decreasing from 100% to 96% over this threshold range.

Evaluation metrics used in object detection approach

To identify relevant and irrelevant frames of surveillance video, a DL-based OD approach is used, and to evaluate these techniques following parameters are applied:-

Confusion matrix

To evaluate the performance of a classification model confusion matrix is used to summarize the outcomes of predictions for different classes. It presents information about the true positive (TP), true negative (TN), false positive (FP), and false negative (FN) predictions made by the model. Table 1 gives an idea about the confusion matrix in detail.

| Predicted positive | Predicted negative | |

|---|---|---|

| Actual positive | True positive | True negative |

| Actual negative | False positive | False negative |

Precision

Precision measures the ratio of correctly detected objects to the total number of objects detected. It focuses on the accuracy of positive predictions.

(2)

Recall

The ratio of correctly detected objects to the total number of ground truth objects.

(3)

F1-score

The F1-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall. It provides a balance between precision and recall, which can be particularly useful when class imbalances exist.

(4)

Accuracy

Accuracy measures correctly predicted objects and balances true positives, false positives, and false negatives as noted in Eq. (5). In other terms, it is a ratio of correct predictions (TP and TN) to the total number of predictions.

(5)

Results and analysis

Evaluation and analysis of OD Module

This subsection gives a detailed analysis of the implemented relevance frame classification module. The FRVC algorithm is applied to seven ATM surveillance videos where Table 2 provides a comprehensive overview of the key characteristics of surveillance video files. It systematically lists pertinent details for each video, including the video number (No.), period of capture (day or night), FPS, resolution, duration, and size. The initial five videos comprise day-time surveillance video, whereas the last two videos feature night-time surveillance. To train YOLOv9 and Mask R-CNN architecture, we consider four different possible combinations of surveillance dataset in a ratio 90–10%, 85–15%, 80–20%, and 75–25% for training-testing and observed their performance in terms of accuracy, speed, recall, and precision. Table 3 gives an idea about the parameter specification required to train YOLOv9 and the Mask R-CNN framework. As the detection accuracy of the two-phase detector is higher than the one-phase detector, we used 40 epochs with batch size 16 to train YOLOv9 while only 30 epochs with batch size 2 to train the Mask R-CNN network. During training, Mask R-CNN uses various loss functions with adam optimizer and a learning rate of 0.01. The loss function consists of RPN loss, classification loss, regression loss, and mask loss. While the loss function in YOLOv9 is also a combination of objectness loss, regression loss, classification loss, balanced loss, and weighted loss. The gradients of this loss are used to update the network’s parameters during backpropagation.

| Video no. | Period | FPS | Resolution | Duration | Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Video-1.avi | Day | 15 | 1,920 1,080 | 1,799 s | 527 MB |

| Video-2.avi | Day | 15 | 1,920 1,080 | 2,399 s | 700 MB |

| Video-3.avi | Day | 15 | 1,920 1,080 | 899 s | 260 MB |

| Video-4.avi | Day | 15 | 1,920 1,080 | 486 s | 142 MB |

| Video-5.avi | Day | 15 | 1,920 1,080 | 851 s | 250 MB |

| Video-6.avi | Night | 15 | 1,920 1,080 | 899 s | 264 MB |

| Video-7.avi | Night | 15 | 1,920 1,080 | 899 s | 265 MB |

| Parameters | YOLOv9 | Mask R-CNN |

|---|---|---|

| Backbone | PGI+GELAN | ResNet-101 |

| Feature aggregation (Neck) | PaNet/SPP | RoI-Align |

| Batch size | 16 | 2 |

| Epoch | 40 | 30 |

| Activation function | Sigmoid linear unit(SiLU) | ReLU |

| Learning rate | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Momentum | 0.9 | 0.9 |

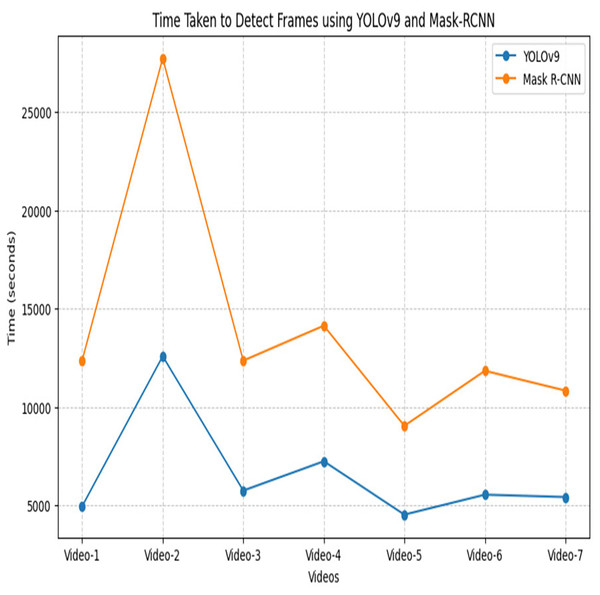

| Weight decay | 0.00005 | 0.00001 |

After an extensive experiment, it is observed that 80–20% ratio gives promising performance and achieves the highest accuracy. Table 4 offers a nuanced understanding of the performance characteristics of the YOLOv9 and Mask R-CNN network, considering key metrics and different data distribution scenarios The YOLOv9 module, achieved the highest accuracy of 99.6% using a split ratio of 80–20% while for Mask R-CNN it is 99.2%. The highest precision of 95.6% is achieved using YOLov9 and 93.8% for Mask R-CNN using 80–20% ratio. Moving to recall, a measure of a module capability to identify all relevant instances, YOLOv5s exhibits consistent improvements, reaching 99.3% and Mask R-CNN showcases varying recall values, with the highest 99.5% achieved at 80–20 ratio. Figure 8 shows the performance of YOLOv9 in terms of evaluation metrics. Derived from these results, an examination reveals that customized YOLOv9 exhibits promising results for the surveillance dataset as compared to Mask R-CNN. Notably, the detection accuracy of the one-phase YOLOv9 model surpasses the two-phase Mask R-CNN. Furthermore, it is observed that Mask R-CNN requires a maximum amount of time (probably twice or thrice) for the detection of relevant and irrelevant frames within the video as compared to YOLOv9. Figure 9 shows the graphical comparison of OD modules on seven different videos. Hence, the output generated through the YOLOv9 module is employed for subsequent compression tasks.

| Dataset split ratio (%) | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv9 model | ||||

| 90–10 | 97.2 | 93.9 | 98.5 | 96.1 |

| 85–15 | 98.3 | 94.9 | 98.6 | 96.7 |

| 80–20 | 99.6 | 95.6 | 99.3 | 97.4 |

| 75–25 | 98.6 | 94.7 | 97.9 | 96.2 |

| Mask R-CNN model | ||||

| 90–10 | 97.5 | 93.5 | 98.2 | 95.9 |

| 85–15 | 98.6 | 92.2 | 98.3 | 95.1 |

| 80–20 | 99.2 | 93.8 | 99.5 | 96.4 |

| 75–25 | 98.8 | 93.1 | 99.2 | 96.0 |

Figure 8: Performance graph of YOLOv9.

Figure 9: Time taken to detect relevant and irrelevant frames of surveillance video using YOLOv9 and Mask R-CNN.

Table 5 represents the count of relevant and irrelevant frames using the YOLOv9 network on seven different tested videos and the time taken by each video to predict the frames. The video2 has the highest number of total frames i.e., 35,990, of which only 5,725 are relevant, while 30,265 are irrelevant and require 12,579 s for detection. Video3 has a notable 13,477 frames, with the highest 9,577 as relevant frames and 3,900 are detected as irrelevant which indicates the maximum transaction activity video. Conversely, Video5 has 12,769 total frames, but only 60 are relevant, which suggests minimal activity. The analysis reveals that longer processing times are required for videos with high frame counts. Hence, Table 5 underscores the importance of YOLOv9 in automated video frame classification and its relevance for applications like surveillance and storage compression.

| Video No. | Total frames | Relevant frames | Irrelevant frames | Time taken to detect frames |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Video-1.avi | 26,996 | 2,736 | 24,260 | 4,947 s |

| Video-2.avi | 35,990 | 5,725 | 30,265 | 12,579 s |

| Video-3.avi | 13,477 | 9,577 | 3,900 | 5,742 s |

| Video-4.avi | 7,290 | 4,772 | 2,518 | 5,234 s |

| Video-5.avi | 12,769 | 60 | 12,709 | 4,519 s |

| Video-6.avi | 13,275 | 2,810 | 10,465 | 5,535 s |

| Video-7.avi | 13,492 | 2,721 | 10,771 | 5,415 s |

Evaluation and analysis of compression module

In the compression module, the output of the YOLOv9 module is used to conduct further compression processes. In the compression process, the similarity index between the relevant frames of surveillance video is determined at various threshold values starting from 100% to 90% and the frames are splits into primary frames and similar frames. It is observed that, at 100% threshold value all relevant frames are primary frames, hence there is no further division of frames, while this splitting starts from 98% threshold value.

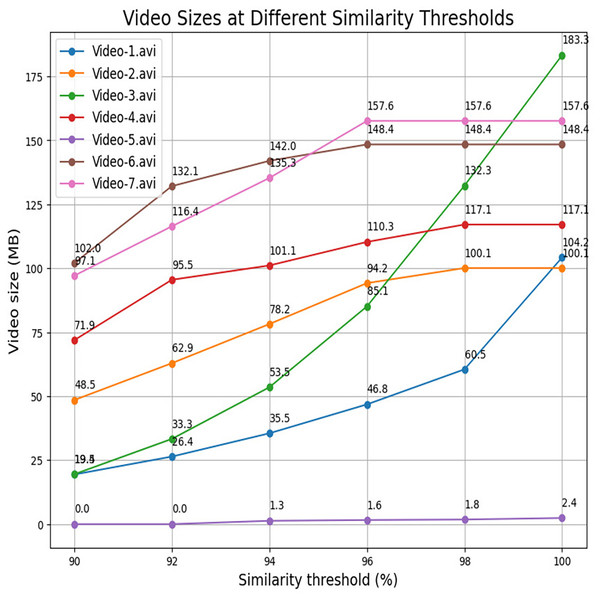

Table 6 systematically displays the maximum compression achieved at a 90% threshold value and provides insights into the efficiency of the compression process in specific scenarios. In this article, compression efficiency is determined in terms of compression ratio and percentage of compression achieved. Compression ratio is a quantitative metric used to evaluate the efficiency of a video compression technique. It is defined as the ratio of the uncompressed (original) video size to the compressed video size. A higher compression ratio signifies a more efficient compression algorithm, as it reflects a greater reduction in data volume required to represent the original content. While the percentage of compression achieved represents the percentage of size reduction after compression. Each video captures transactional activities, which focuses on the presence and actions of individuals within the surveillance video. We analyze videos across three distinct scenarios. Figure 10 represents sample frames of the three scenarios of videos. Scenario-I refers to a situation when single individuals enter an ATM room and engage in transactional activities. Specifically, Video-1, Video-2, and Video-3 belong to Scenario-I and these demonstrate the highest compressions within the dataset, reaching 96.3%, 93.0%, and 92.5%, respectively, when individuals are detected. In Scenario-II, the video depicts a timeframe where no human presence is detected. Specifically, Video-5 corresponds to Scenario-II. For Video-5, out of the 12,769 frames, only 60 frames are identified as relevant, achieving an impressive compression rate of 99.9% at a threshold value of 90%. This implies that the entire video is effectively recognized based on a small subset of frames. In fact, at a 100% threshold value, the compression rate is still substantial, reaching 98.9%. While scenario-III entails videos-4, video-6 and video-7, where two individuals jointly enter the surveillance room and engage in transactional activities. In this scenario, the frames exhibit lower similarity, resulting in a larger proportion being considered as primary frames. Consequently, these videos achieve lower compressions of 49.3%, 61.3%, and 63.3%, respectively, compared to other scenarios. The percentage of video compression is determined using Eq. (6). Table 6 provides compression ratios achieved by the FRVC framework across different surveillance scenarios, indicating how many times the original videos were compressed. Scenario-II (no human presence) achieved the highest compression ratio of 1,369.52, reflecting minimal scene changes. Scenario-I (single-person activity) achieved ratios between 13.34 and 27.16, while Scenario-III (multi-person activity) showed lower ratios around 2 to 3 due to increased scene complexity. These results highlight the influence of video content on compression efficiency. It is essential to note that, while conducting video compression across various threshold values, a deliberate effort is made to uphold the video’s quality. This entails maintaining the values of FPS and frame resolution consistently, aligning them with the original specifications. This strategic approach is designed to prioritize the preservation of essential visual characteristics throughout the compression process and ensure that the perceptual quality of the video remains uncompromised. Figure 11 provides a visual representation of frame count between different threshold values for each video. For example, video-1.avi contains a total of 26,996 frames out of which 2,736 frames are recognized as relevant frames using the YOLOv9 network which is further divided into 2,491 primary frames and 245 similar frames at a 98% threshold, resulting in a video size of 104.2 MB. Similarly, at a 96% threshold, there are 1,709 primary frames, 1,025 similar frames, and a reduced video size of 60.5 MB. The count of primary frames further decreases to 1,157, with 1,579 similar frames, yielding a compressed video size of 35.5 MB at a 94% threshold. At a 92% threshold, 780 primary frames, 1,956 similar frames, and a video size of 26.4 MB are observed. Finally, at a 90% threshold, there are 539 primary frames, 2,197 similar frames, and a video size of 19.4 MB. Table 7 details the compressed video size at various threshold values, while Fig. 12 graphically represents the size of the video. It is evident that as the similarity value between frames decreases, the compression size increases. The highest compression is achieved at a 90% threshold, while the minimum compression is observed at a 100% threshold.

(6)

| Video no. | Scenario | Original video size | Original video duration | Compressed video size | Compression ratio | % of compression acheive |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Video-1.avi | Scenario-I | 527 MB | 1,799 s | 19.4 MB | 27.16 | 96.3% |

| Video-2.avi | Scenario-I | 700 MB | 2,399 s | 48.5 MB | 14.43 | 93.0% |

| Video-3.avi | Scenario-I | 260 MB | 899 s | 19.5 MB | 13.34 | 92.5% |

| Video-4.avi | Scenario-III | 142 MB | 486 s | 71.9 MB | 1.97 | 49.3% |

| Video-5.avi | Scenario-II | 250 MB | 851 s | 187 KB | 1,369.52 | 99.9% |

| Video-6.avi | Scenario-III | 264 MB | 899 s | 102.1 MB | 2.58 | 61.3% |

| Video-7.avi | Scenario-III | 265 MB | 899 s | 97.1 MB | 2.73 | 63.3% |

Figure 10: Represent the three scenarios of the videos (A) Scenario-I, (B) Scenario-II and (C) Scenario-III.

Figure 11: Count of primary and similar frames vs. similarity threshold for the tested seven ATM surveillance videos.

| Video no. | Original size | TH = 100 | TH = 98 | TH = 96 | TH = 94 | TH = 92 | TH = 90 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Video-1.avi | 527 MB | 104.2 MB | 60.5 MB | 46.8 MB | 35.5 MB | 26.4 MB | 19.4 MB |

| Video-2.avi | 700 MB | 100.1 MB | 100.1 MB | 94.2 MB | 78.2 MB | 62.9 MB | 48.5 MB |

| Video-3.avi | 260 MB | 183.3 MB | 132.3 MB | 85.1 MB | 53.5 MB | 33.3 MB | 19.5 MB |

| Video-4.avi | 142 MB | 117.1 MB | 117.1 MB | 110.3 MB | 101.1 MB | 95.5 MB | 71.9 MB |

| Video-5.avi | 250 MB | 2.4 MB | 1.8 MB | 1.6 MB | 1.3 MB | 187 KB | 187 KB |

| Video-6.avi | 264 MB | 148.4 MB | 148.4 MB | 148.4 MB | 142 MB | 132.1 MB | 102.0 MB |

| Video-7.avi | 265 MB | 157.6 MB | 157.6 MB | 157.6 MB | 135.3 MB | 116.4 MB | 97.1 MB |

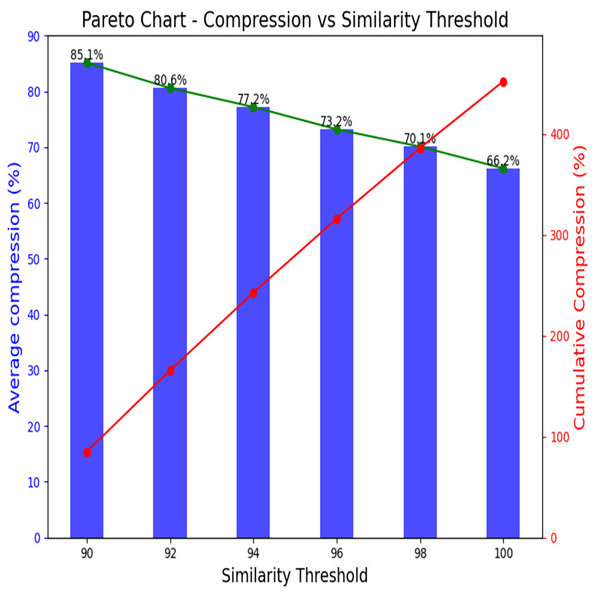

| Average % of compression | — | 66.2% | 70.1% | 73.2% | 77.2% | 80.6% | 85.13% |

Figure 12: Size of compressed video at different threshold values.

Table 7 also serves as a quantitative representation of the impact of similarity threshold values on video compression. It allows for a detailed examination of how variations in these thresholds influence the compression ratios for different videos. At a 100% threshold, a minimum 66.2% average compression reached is achieved. For the 98% threshold, the average compression is 70.1%, while at 96%, it is recorded as 73.2%. The average compression for a 92% threshold is 80.6%, and the highest compression of 85.1% is achieved at a 90% threshold. Notably, the average compression increases as the similarity threshold decreases, the observed trends in compression sizes provide valuable insights into the relationship between similarity threshold values and the efficiency of the compression algorithm, which can be crucial for optimizing video storage and transmission in surveillance systems. Based on the above analysis, it is observed that the most significant compression is observed in Scenario I, where a lone individual engages in transactional activities. Conversely, Scenario II, characterized by the absence of relevant parts, is instrumental in optimizing storage space. Notably, the highest compression achieved is 96.3%, with an average compression of 85.1% at a 90% threshold value. The observed trend underscores that compression increases as the similarity between frames diminishes. Figure 13 visually encapsulates this relationship through a Pareto chart, providing a comprehensive overview of the outcomes across the seven tested videos. The Pareto chart discernibly demonstrates the inherent trade-off between prioritizing similarity and compression. It demonstrates that while increasing similarity thresholds reduces individual compression rates, the cumulative compression remains significant. Decision-makers should carefully select similarity thresholds based on the desired trade-off between data accuracy and compression efficiency. For applications where data accuracy is critical, higher thresholds should be preferred despite lower compression. However, for storage-intensive applications where efficiency is prioritized, lower thresholds may be more suitable. Comprehensively, these findings contribute to the optimization of video storage and transmission within surveillance systems, that underscore the delicate balance between similarity thresholds, compression efficiency, and visual fidelity. The scientific approach employed ensures that key video attributes, such as FPS and resolution, are preserved throughout the compression process, which prioritizes the retention of essential visual information.

Figure 13: Pareto chart for average compression % of seven tested videos.

State-of-the-art works comparison

Table 8 presents a comparative analysis of the proposed FRVC framework with three state-of-the-art video compression approaches tailored for surveillance and medical video scenarios. Each method employs different strategies for video frame compression and relevance detection, and the table highlights key parameters such as the compression approach, object detection (OD) techniques used, frame resolution, FPS, compression ratio, and type of compression.

| Parameter | Panneerselvam et al. (2023) | Ghamsarian et al. (2020) | Lu & Xu (2019) | FRVC framework |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Approach | Used CNN+GAN to perform pixel level compression | From ophthalmologist, view determine the types of frame using neural network | Object separation based deep compression technique for apron surveillance | Adopts relevance frame classification |

| OD approach | No | Yes (Mask R-CNN) | Yes (Faster-R-CNN) | Yes (YOLOv9) |

| Resolution of frame | Not mention | Not mention | 1,920 1,080 | 1,920 1,080 |

| FPS | 25 | 20 | 25 | 15 |

| Compression ratio | Up to 50.71% | up to 63% | Up to 88% | Up to 96.3% (for scenario-I) and 99.9% (for scenarios-II) |

| Type of compression | Lossy compression | Lossy compression | Lossy compression | Lossy compression |

The first approach, by Panneerselvam et al. (2023), leverages a combination of CNN and GAN to perform pixel-level compression. Their approach focuses on eliminating duplicate frames and captures minor changes between frames using GAN and long short-term memory (LSTM) networks for recording the altered frames. This method achieves a compression ratio of up to 50.71% and processes video frames at 25 FPS. However, it does not incorporate any explicit object detection module, and frame resolution details are not specified. The second approach, by Ghamsarian et al. (2020), is designed for cataract surgery videos and uses Mask-RCNN for semantic segmentation and classification of video frames based on their relevance. This approach focuses on reducing bitrate by assigning less importance to non-critical frames, thereby achieving a compression ratio of up to 63%. The video frames are processed at 20 FPS, but, similar to the previous method, the exact frame resolution is not mentioned. Lu & Xu (2019) present a deep compression technique applied to apron surveillance videos. Their method employs Faster-RCNN to distinguish between moving and stationary objects and selectively compress frames based on this object separation. It achieves a higher compression ratio of up to 88% with a frame resolution of 1,920 1,080 and a frame rate of 25 FPS. This method stores extracted objects and background separately to facilitate compression.

The proposed FRVC framework outperforms all the aforementioned methods in terms of compression efficiency. It uses the latest YOLOv9 object detection approach, enabling more precise identification of relevant frames in ATM surveillance videos. The framework achieves an impressive compression ratio of up to 96.3% in Scenario-I and 99.9% in Scenario-II, both at a high resolution of 1,920 1,080 pixels. Although the frame rate after compression is slightly lower at 15 FPS, this is a reasonable trade-off given the significant improvement in compression ratio. Like the other approaches, the FRVC framework employs lossy compression. Overall, the table illustrates that the FRVC framework provides a superior balance of compression ratio, frame quality, and object detection accuracy by incorporating advanced detection methods and relevance classification, thus demonstrating a clear advantage over existing state-of-the-art solutions.

Conclusions

In this study, we proposed a novel frame relevance-based video compression (FRVC) model designed to efficiently compress surveillance videos by distinguishing relevant and irrelevant frames from the user’s perspective. In this pursuit, we selected ATM surveillance as our use case and developed our own customized dataset. We trained Mask R-CNN from a two-phase detector and YOLOv9 from a one-phase detector on various possible combinations of datasets to recognize relevant frames and irrelevant frames. After conducting an extensive experiment, the findings reveal that YOLOv9 outperformed Mask R-CNN in terms of accuracy and detection time. The FRVC compression module leverages the detection results to remove irrelevant frames and applies similarity-based analysis across three defined scenarios, that achieve a maximum compression ratio of 96.3% and an average compression of 85.1% while maintaining the original frame resolution and content integrity. The subsequent decompression algorithm effectively reconstructs the video, ensuring 100% retrieval of relevant frames, thereby preserving critical surveillance information for storage optimization and transmission efficiency. Though our proposed method surpasses existing methodology but it limits the effectiveness of algorithms. As it depends on the accuracy of the YOLOv9 model in detecting relevant frames. Misclassifications, such as missing important frames, will affect the integrity of the surveillance footage.

Our research aims to extend the investigations to the upcoming models of object detection frameworks as a future research. In addition, we plan to improve the model capabilities to identify violent or suspicious activities in surveillance videos. This enhancement would not only trigger alarms, but would also initiate automated messages to law enforcement teams, contributing to the proactive and effective use of surveillance technologies for public safety and security.